Abstract

Rationale

A small but growing body of research documents associations between structural forms of stigma (e.g., same-sex marriage bans) and sexual minority health. These studies, however, have focused on a limited number of outcomes and have not examined whether sociodemographic characteristics, such as race/ethnicity and education, influence the relationship between policy change and health among sexual minorities.

Objective

To determine the effect of civil union legalization on sexual minority women’s perceived discrimination, stigma consciousness, depressive symptoms, and four indicators of hazardous drinking (heavy episodic drinking, intoxication, alcohol dependence symptoms, adverse drinking consequences) and to evaluate whether such effects are moderated by race/ethnicity or education.

Methods

During the third wave of data collection in the Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women study (N=517), Illinois passed the Religious Freedom Protection and Civil Union Act, legalizing civil unions in Illinois and resulting in a quasi-natural experiment wherein some participants were interviewed before and some after the new legislation. Generalized linear models and interactions were used to test the effects of the new legislation on stigma consciousness, perceived discrimination, depression, and hazardous drinking indicators. Interactions were used to assess whether the effects of policy change were moderated by race/ethnicity or education.

Results

Civil union legislation was associated with lower levels of stigma consciousness, perceived discrimination, depressive symptoms, and one indicator of hazardous drinking (adverse drinking consequences) for all sexual minority women. For several other outcomes, the benefits of this supportive social policy were largely concentrated among racial/ethnic minority women and women with lower levels of education.

Conclusions

Results suggest that policies supportive of the civil rights of sexual minorities improve the health of all sexual minority women, and may be most beneficial for women with multiply marginalized statuses.

1. Introduction

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB; sexual minority) populations are at heightened risk for a variety of adverse health outcomes and have higher rates of negative coping behaviors, such as hazardous drinking, compared to heterosexuals (Hughes et al., 2010; Institute of Medicine, 2011). Sexual-orientation-related disparities in depression and hazardous drinking are particularly robust among women (Hughes, Wilsnack & Kantor, 2015; Hughes, McCabe, Wilsnack, Boyd, & West, 2010; Marshal et al., 2008, 2011). For example, a meta-review of 18 studies documented that sexual minority women (SMW) have 400% higher odds of substance abuse, including alcohol use and misuse, compared to heterosexual women (Marshal et al., 2008). Understanding the mechanisms that lead to such acute disparities between SMW and heterosexual women is critical.

Research on predictors of sexual-orientation-related disparities has largely focused on interpersonal discrimination and victimization and the negative psychological sequelae of such events (e.g., Feinstein, Goldfried, & Davila 2012; Mays & Cochran, 2001). A growing body of research, however, documents the influence of structural forms of stigma and discrimination—which include laws and policies, as well as cultural norms—on physical and mental health among sexual minorities (SM) in the United States (e.g., for reviews, see Hatzenbuehler, 2010; 2014). Although these studies provide important insights into social determinants of LGB health, important questions remain. First, theories of intersectionality (Bowleg, 2012) suggest that structural factors interact with individual characteristics in ways that could position some women within SM populations to benefit more or less from macro-level policy changes, such as those that legally recognize same-sex relationships. As such, some scholars have argued that SMW of color may benefit less than White SMW from such policy changes (Kandaswamy, 2008). Given small sample sizes of LGB respondents in existing studies on social policies and health, researchers typically combine subgroups of LGB respondents, such as Whites and people of color (e.g., Hatzenbuehler, Keyes, & Hasin, 2009; Rostosky, Riggle, Horne, & Miller, 2009), or include only one demographic group (e.g., men; Hatzenbuehler, O’Cleirigh, Grasso, Mayer, Safren, & Bradford, 2012). Consequently, research has yet to examine whether sociodemographic characteristics moderate the relationship between policy change and SMW health.

Second, previous research on the impact of social policy change on SMW health has focused on mental health variables, such as psychological distress (Rostosky et al., 2009) or psychiatric disorders (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009). It is likely that social policies affect a broader range of health behaviors and outcomes, such as hazardous drinking, among SMW, but this has not been empirically tested.

Third, although the economic benefits of supportive policy changes, such as those that legally recognize same-sex relationships, are not likely to be immediate, such changes may have immediate psychological benefits. Indeed, polices that prohibit the legal recognition of same-sex relationships serve as a constant reminder of the devalued status of same-sex relationships (Herek, 2006). Importantly, prior studies have demonstrated a relationship between same-sex marriage policy and mental health within relatively short time-frames, both positive in the case of legalization (e.g., less than one year [Hatzenbuehler et al., 2012]) and negative in the case of marriage bans (e.g., one month [Rostosky, Riggle, Horne, & Miller, 2009] and less than one year [Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, Keyes, & Hasin, 2010]). However, factors responsible for these more immediate psychological impacts of same-sex marriage, such as reductions in perceived discrimination and stigma consciousness, have rarely been addressed. We address these gaps in the literature by examining data from a quasi-natural experiment involving passage of the 2011 civil union act in Illinois.

1.1 Structural Discrimination, Minority Stress, and Health

Minority stress—the excess stress that minorities face due to their stigmatized status—has been identified as a key mechanism underlying sexual-orientation-related health disparities (Meyer, 2003). Perceived discrimination, the feeling of being treated unfairly or poorly due to an individual characteristic, and stigma consciousness, the expectation of being discriminated against by others (Pinel, 1999), are two forms of minority stress that are robust predictors of poorer mental health among SMs (Feinstein et al., 2012; Mays & Cochran, 2001). Both perceived discrimination and stigma consciousness have been previously linked to mental health and substance use among LGB populations (Mays & Cochran, 2001; McCabe, Bostwick, Hughes, West, & Boyd, 2010).

Recently U.S. researchers have expanded the minority stress framework to include structural-level sources of discrimination, such as state-level policies that differentially target sexual minorities for social exclusion (Hatzenbuehler, 2014). For instance, using a quasi-experimental design, Hatzenbuehler and colleagues (2010) found that LGB adults who lived in states that passed constitutional amendments banning same-sex marriage experienced a significant increase in psychiatric morbidity; these increases were not observed among LGB respondents in states that did not ban same-sex marriage. Further, the amendments did not negatively affect the mental health of heterosexuals, indicating that the results were specific to LGB respondents. An online survey similarly showed that SMW and men in U.S. states that passed same-sex marriage bans reported more minority stressors and greater levels of psychological distress than those in states without marriage bans (Rostosky et al., 2009).

Conversely, state-level policies can also represent positive change and inclusion, thereby improving the health of stigmatized individuals. Indeed, passage of legislation that legally recognizes same-sex relationships has been associated with decreased use of healthcare services and healthcare costs, as well as decreases in stress-related conditions such as depression and hypertension, among SM men (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2012). This research also showed that the health benefits of same-sex marriage are comparable for partnered and non-partnered SM men, suggesting that these benefits are, in part, accrued through mechanisms unrelated to marital status (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2012).

The passage of major supportive social policies in the U.S., such as civil union legislation, result in symbolic and concrete reductions in discrimination and stigma and consequently in better mental health (Hatzenbuehler, 2010) and fewer negative coping behaviors such as hazardous drinking among SMs (e.g., Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2011). Textual analyses of open-ended responses to survey questions related to the legalization of same-sex civil unions in Vermont indicated that this policy change was associated with increased psychological benefits and family acceptance, in addition to financial benefits (Rothblum, Balsam, & Solomon, 2011). Other research, conducted in the U.S. and in the Netherlands, has found that same-sex marriage legalization is associated with feelings of greater social inclusion (Badgett, 2011).

Taken together, these findings suggest that legal recognition of same-sex relationships increase feelings of belonging—a fundamental human need and an essential component of mental health (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Thus, in addition to financial benefits, state policies that legally recognize same-sex relationships may also confer immediate psychological benefits due to the lessening of perceived and actual discrimination and stigmatization at the macro-level (Hatzenbuehler, 2010). We test this hypothesis by examining legislative changes on both perceived discrimination and stigma, in addition to mental and behavioral health outcomes.

1.2 Civil Union Legislation and Intersectionality

Theories of intersectionality highlight the importance of considering multiple minority identities in studies of health disparities (Bowleg, 2008; Warner & Shields, 2013). Broader social systems, such as those that impose differential treatment based on race, class, or sexual orientation, can undermine or exacerbate the health effects of specific events. That is, although SMW share their sexual minority status, they may differ on other sociodemographic characteristics associated with privilege and disadvantage. In fact, race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES) may be more relevant to SMW’s experience of minority stress and health than their shared experience of SM status (Breines, 2002).

Whether the benefits of policies that recognize and support same-sex relationships extend to all SMs regardless of gender, race/ethnicity, or SES—or whether they differentially benefit certain groups more than others—is largely unknown. Legislation supporting civil unions may bring much-needed relief to SMs who are multiply disadvantaged by granting them access to an important social institution that comes with a variety of economic and social advantages (Herek, 2006). For instance, racial/ethnic minority women, regardless of their sexual orientation, face substantial discrimination that limits access to employment (Browne & Misra, 2003). Legal recognition of same-sex relationships gives SMW of color access to benefits that may disproportionately increase their socioeconomic stability relative to White SMW, via associated financial and healthcare benefits. Similarly, civil unions may disproportionately improve the financial stability of women with lower SES, regardless of their race, which may result in improvements in their health (Liu, Reczek, & Brown, 2013).

Given that SMW of color often face discrimination within their SM communities (Balsam, Molina, Beadness, Simoni, & Walters, 2011), as well as their racial/ethnic communities (Choi, Han, Paul, & Ayala, 2011; O’Donnell, Meyer, & Schwarts, 2011), greater social acceptance at the institutional level may disproportionately improve the well-being of SMW of color. Similarly, supportive social policies such as legal recognition of same-sex relationships may disproportionately benefit women with low levels of education. Education, in addition to being a being a strong predictor of income and occupational status, is independently associated with a variety of important psychological resources, especially among women (Ross & Mirowsky, 2006). Compared with SMW with higher levels of educational attainment, SMW with lower levels of education report higher levels of psychological distress (Szymanski & Kashubeck-West, 2008). Further, other research has shown that SES moderates the relationship between discrimination and distress among racial/ethnic minorities, such that the harmful effects of discrimination are greater among those with low SES (measured via employment status) compared to those with high SES (e.g., Forman, 2003). As such, they may also be more responsive to positive changes in discriminatory policies.

Alternatively, for SMW with multiple minority statuses, the passage of a bill that increases civil rights related to their sexual orientation may be less likely to reduce stress than for White or high-SES SMW due to “cumulative risk” disadvantage, namely, the continued marginalization that SMW from racial/ethnic minority or low-SES groups face related to their multiply marginalized statuses. Support for this hypothesis comes from the fundamental causes theory (Link & Phelan, 2005) and from research demonstrating that population-level interventions may improve health outcomes at a population level, while at the same time exacerbating existing inequalities in health (Frohlich & Potvin, 2008). For example, following the dissemination of Highly Active Antiretroviral Treatments (HAART) for individuals living with HIV/AIDS, racial disparities in HIV-related mortality increased (Rubin, Colen, & Link, 2010). Such results suggest that policies supporting same-sex relationships may be more beneficial for those who have greater access to social and economic resources unrelated to such policies—that is, White, well-educated SMW. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to empirically evaluate these two competing hypotheses with respect to the impact of civil union legislation on the health of SMW.

1.3 Current Study

This study capitalized on an opportunity to conduct a quasi-natural experiment to test the impact of Illinois’ Religious Freedom Protection and Civil Union Act on two indicators of minority stress (perceived discrimination and stigma consciousness), as well as on depressive symptoms and hazardous drinking. During periods surrounding same-sex civil union and marriage decisions, SMs report higher rates of perceived and actual discrimination, anxiety, and depression immediately before (Fingerhut, Riggle, & Rostosky, 2011; Levitt et al., 2009; Maisel & Fingerhut, 2011) and reductions after (Rostosky et al., 2009) the decisions. Thus, during the months leading up to the Governor’s official signing of the civil union bill, we expected potentially elevated levels of minority stress, depression and hazardous drinking compared to the two other groups. During the time after the bill was signed, but before it was enacted, we expected some reductions in our psychosocial and health behavior outcomes. Given that legislation to legally recognize same-sex relationships in Illinois had previously been proposed in 2007 and 2009, but was not passed on either occasion, we expected that the largest benefits of the legislation would be accrued post-enactment when the bill officially became law.

In sum, we address previous gaps in the literature by directly testing (1) the effects of civil union legislation on psychosocial and health behavior outcomes, including stigma consciousness, perceived discrimination, depressive symptoms, and multiple indicators of hazardous drinking behaviors, among SMW; and (2) whether the health and psychosocial effects of civil union legislation for SMW vary by race/ethnicity and education. This study reflects a rare opportunity to build upon existing knowledge by explicitly testing moderating factors that may potentiate or attenuate relationships between social policies and the health of SMW.

2. Methods

2.1 Data

Data are from the Chicago Health and Life Experience of Women (CHLEW) study, a 17-year, three-wave longitudinal study of adult SMW. The CHLEW study is unique in that it was designed to understand the health and life experiences of SMW. Therefore, the study contains measures that are seldom included in nationally representative studies—such as stigma consciousness, sexual orientation- and gender-related discrimination, and in-depth measures of depression and hazardous drinking. Women in the CHLEW study were recruited from the greater Chicago metropolitan area in 2000–2001 using a broad range of sources and strategies to produce a diverse sample of 447 English-speaking women age 18 and older who self-identified as lesbian. Concerted efforts were made to maximize sample representativeness by targeting recruitment toward subgroups of women underrepresented in most studies of lesbian health (i.e., under age 25 and over age 50, high school education or less, racial/ethnic minority). The study was advertised in local newspapers, on Internet listservs, and on flyers posted in churches and bookstores. Information about the study was also distributed to individuals and organizations via formal and informal social events and social networks. Other recruitment sources included clusters of social networks (e.g., formal community-based organizations and informal community social groups) and individual social networks, including those of women who participated in the study. Interested women were invited to call the project office to complete a short telephone-screening interview. Participants who reported being heterosexual, mostly heterosexual, bisexual, or transgender at Wave I were not invited to participate (however, as described below, bisexual women were later added as part of a supplemental sample). The baseline sample included women 18–82 years old, and less than one-half of the sample was White. In Wave II (2003–2004) we retained 84% of the original sample, and in Wave III (2010–2012) we retained 79%.

In Wave III an additional sample of 373 women was added to increase diversity related to age, race/ethnicity and sexual orientation. Recruitment of the new study panel, using an adaptation of respondent-driven sampling, was designed to oversample Black, Latina, and younger lesbians (ages 18–25), as well as women who identified as bisexual.

Our analyses are restricted to the third wave of CHLEW data, which includes women in both the baseline and supplemental samples who were living in Illinois (N = 586). We excluded participants who no longer identified as lesbian or bisexual (N = 14), and those whose self-reported racial/ethnic identity was something other than Black, Latina or White (N = 15). An additional 22 women were excluded who were missing data for stigma consciousness and depressive symptoms, and 18 women were excluded who were missing data on hazardous drinking, resulting in a total final sample size of 517 participants. Supplemental analysis showed that women missing on hazardous drinking were more likely to be interviewed after civil union legislation was enacted than those without missing data on this variable. No other differences were found based on time of interview.

2.2 Variables

2.2.1 Civil Union Legislation

The main independent variable was whether participants were interviewed before Illinois’ civil union bill was passed, between the time of passage and enactment, or after the bill was enacted. Three dichotomous variables were created using the date of respondent interview, the date Illinois’ civil union bill was signed into law, and date the bill was enacted. Participants interviewed before January 31, 2011 were coded as being interviewed before the bill’s passage (referent); participants interviewed between January 31, 2011 and May 31, 2011 were coded as interviewed after the bill was signed into law but before enactment; and participants interviewed after June 1, 2011 were coded as interviewed after the bill was enacted.

2.2.2 Stigma Consciousness

Stigma consciousness was measured using a series of questions related to participants’ sensitivity to and awareness of stigma. Because lesbian and bisexual women report some differences in their experiences of stigma (Bostwick, 2012), the questions were tailored specifically to capture the unique dimensions of stigma consciousness for lesbian and bisexual participants. The lesbian stigma-consciousness scale follows Pinel (1999) and asked participants ten questions, such as, “Stereotypes about lesbians have not affected me personally,” and “I never worry that my behaviors will be viewed as stereotypical of lesbians.” Response options range from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). Some items were reverse-coded so that higher scores indicate higher levels of stigma consciousness. The scale had an alpha of 0.69.

Bisexual women were asked how much they agreed or disagreed with nine statements such as: “Stereotypes about bisexuality have affected me personally,” and “I worry that certain behaviors will be viewed as stereotypically bisexual.” The alpha for this scale was 0.831.

Because the scales for lesbian and bisexual women have a different number of items, both were standardized and each respondent was assigned the standardized score for the scale that corresponded with her reported identity. The final scale scores ranged from −1.4 to 2.0, with a mean of 0.

2.2.3 Gender- and Sexual-Orientation-Related Discrimination

The perceived discrimination scale was adapted from Krieger and colleagues’ (2005) measure and included six questions about experiences of discrimination in the past 12 months, such as, “About how often did you experience discrimination in your ability to obtain healthcare or health insurance coverage?” and “How often have you experienced discrimination in public, like on the street, in stores or in restaurants?” For each item, a follow-up question asked participants to identify the main reason(s) for the experience (e.g., gender, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity). Because of high rates of gender nonconformity among sexual minorities, sexual minorities are frequently targeted for their gender presentation as an indicator of their sexual minority status (Rieger & Savin-Williams, 2011). Thus, we include both incidences of gender- or sexual orientation-based discrimination. Participants who identified gender or sexual orientation as a reason for the discriminatory experience were given a score of “1” for each experience reported.2 The total number of gender- or sexual orientation-related experiences of discrimination were then summed and scaled (range: 0 to 6).

2.2.4 Depressive Symptoms

A depressive-symptoms scale was constructed using 10 questions from the CESD-10 (Radloff, 1977). For example, “Over the past week have you: felt depressed; felt everything you did was an effort; had sleep that was restless; felt happy; felt lonely; felt people were unfriendly; felt you could not ‘get going?’” Response options ranged from 0, “rarely or none of the time (less than one day)” to 3 “most or all of the time (5 to 6 days).” Responses were reverse-coded where appropriate so that higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms. The scale had an alpha of .83 and ranged from 0 to 29.

2.2.5 Hazardous Drinking Indicators

We used four measures of hazardous drinking from a 20-year longitudinal study of drinking among women in the U.S. general population (Wilsnack, Wilsnack, Krisjanson, Vogeltanz-Hom, & Windle, 2004). (1) Heavy episodic drinking was coded as a binary variable using a question that asked whether in the past 12 months the participant had ever consumed six or more drinks in a day (yes=1; no=0). (2) A similar question asked about the frequency of subjective intoxication (“drinking enough to feel drunk—where drinking noticeably affected your thinking, talking, and behavior”). This variable was coded as continuous and ranged from 0 (“never”) to 7 (“5 or more times a week”). (3) Participants were asked about their past 12-months’ experience of eight adverse drinking consequences (e.g., driving a car while high from alcohol; drinking-related accidents in the home; harmful effects of drinking on housework or chores or on job or career opportunities; drinking-related problems with partner; and starting fights with partner or with people outside the family when drinking). The measure was coded as a continuous count variable that ranged from 0 to 8. (4) Symptoms of potential alcohol dependence included blackouts, rapid drinking, morning drinking, inability to stop drinking before becoming intoxicated, and inability to stop or cut down on drinking over time, and were coded as a continuous count measure ranging from 0 to 5.

2.2.6 Moderators

Race/ethnicity was coded as a dummy variable to indicate non-Hispanic White or Black/Latina (referent).3 Education was coded as series of dichotomous variables that measured whether participants reported having a high school education or less, some college, or a college (bachelor’s or higher) degree (referent).

2.2.7 Other Sociodemographic Characteristics

Sexual identity was measured using an item that asked, “Recognizing that sexual orientation is only one part of your identity, how do you define your sexual identity? Would you say that you are only lesbian/gay, mostly lesbian/gay, bisexual, mostly heterosexual, only heterosexual/straight, or other?” A dummy variable was created to capture whether participants identified as only lesbian (referent), mostly lesbian, or bisexual. Respondents who chose other identity options were excluded from these analyses.

Age was coded as a continuous variable ranging from 18 to 79. Relationship status was coded as a series of dummy variables that measured whether, at the time of interview, participants were single, in a relationship (referent), or widowed, divorced or separated from their partner. We used a binary code for whether there was a child under age 18 living in the household (1=yes; no=0).

2.3 Analytic Approach

We first present descriptive statistics for the total sample stratified by time of interview. Bivariate tests were used to identify statistically significant differences in mean responses of participants interviewed before the civil union bill was passed and those interviewed after its passage and after its enactment. We then present results from generalized linear models testing for differences in stigma consciousness, perceived discrimination, and depressive symptoms by civil union bill status. In order to assess whether the impact of civil union legislation on these measures was moderated by sociodemographic characteristics, we conducted a series of tests for interactions between race/ethnicity, education, and bill status. Ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression was used for the stigma consciousness and depressive symptoms analyses, and negative binomial regressions were used in the perceived discrimination analyses.

We also assessed the relationship between civil union bill status and the four indicators of hazardous drinking. We used logistic regression for heavy episodic drinking and Poisson regression for the other three indicators. We examined whether the relationship between civil union legislation and hazardous drinking was moderated by race/ethnicity and education using a series of multiplicative interaction terms. For each dependent variable, Model 1 adjusts for all covariates, Model 2 includes an interaction between legislation and race/ethnicity, and Model 3 includes an interaction between legislation and education4. We report effect sizes for all OLS regression models where coefficients were significant. All analyses adjust for sexual identity, age, race/ethnicity, education, relationship status, and whether there was a child under the age of 18 living in the home. All models were conducted using Stata 12, and figures were produced using the “margins” commands.

3. Results

3.1 Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics summarized in Table 1 highlight the diversity of the CHLEW sample: 40% of participants were non-Hispanic White and 60% were Black or Latina. The mean age of the sample was 40 years, and 45% had college degrees. The majority (59%) of the sample identified as exclusively lesbian, 16% identified as mostly lesbian, and 24% identified as bisexual. Thirty-seven percent of the sample was interviewed prior to the Civil Union bill being signed (83 White and 109 Black/Latina women), 22.9% (31 White and 88 Black/Latina) after the bill was signed but before it was enacted, and 40% (82 White and 124 Black/Latina) were interviewed after the bill was enacted.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for total population and stratified by interview date

| Total Population | Pre-Signed | Bill Signed | Bill Enacted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37.30% | 22.90% | 39.80% | ||||||

|

|

||||||||

| M/% | (SE) | M/% | (SE) | M/% | (SE) | M/% | (SE) | |

|

|

||||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 37.20 | 43.01 | 26.83 | 37.90 | ||||

| Black/Latina | 62.80 | 56.99 | 73.17 | * | 62.10 | |||

| Age | 40.21 | 0.62 | 41.46 | 1.07 | 40.42 | 1.34 | 39.99 | 0.91 |

| Education | ||||||||

| High school or less | 22.06 | 13.99 | 30.08 | * | 24.66 | |||

| Some college | 33.27 | 31.61 | 34.96 | 33.79 | ||||

| College graduate | 44.67 | 54.40 | 34.96 | ** | 41.55 | |||

| Sexual orientation | ||||||||

| Exclusively lesbian | 59.18 | 64.77 | 65.04 | 50.91 | * | |||

| Mostly lesbian | 16.10 | 19.69 | 11.38 | 15.60 | ||||

| Bisexual | 24.72 | 15.54 | 23.58 | 33.49 | ** | |||

| Relationship status | ||||||||

| In a relationship | 62.10 | 60.42 | 56.91 | 66.51 | ||||

| Widowed/separated | 4.32 | 5.73 | 3.25 | 3.67 | ||||

| Single | 33.58 | 33.85 | 39.84 | 29.82 | * | |||

| Child in the house | 18.73 | 20.21 | 18.70 | 17.43 | ||||

| Stigma consciousness | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.04* |

| Discrimination | 0.81 | 0.04 | 0.90 | 0.09 | 0.80 | 0.11 | 0.71 | 0.07 |

| Depressive symptoms | 6.80 | 0.25 | 6.74 | 0.39 | 6.24 | 0.50 | 7.17 | 0.42 |

| Heavy episodic drinking | 39.30 | 34.72 | 34.96 | 45.87 | * | |||

| Intoxication | 1.35 | 0.08 | 1.32 | 0.12 | 1.32 | 0.17 | 1.39 | 0.12 |

| Alcohol dependency | 0.51 | 0.05 | 0.42 | 0.07 | 0.51 | 0.10 | 0.59 | 0.08 |

| Adverse drinking consequences | 0.50 | 0.05 | 0.58 | 0.08 | 0.38 | 0.07 | 0.51 | 0.08 |

Source: Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women Survey

Notes:

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001;

SE =Standard Error; Regression type in parentheses; N =517

We also conducted a series of tests to determine whether there were differences in characteristics of the sample across time of interview. We detected some minor differences in sociodemographic characteristics—6 of the total 26 tests (23%) conducted suggested significant differences across groups—but these differences did not appear to be systematic. Participants interviewed after the bill passed but before it was enacted were more likely to be Black and to have lower levels of education than participants interviewed before the bill passed. Participants interviewed after the bill was enacted were more likely to be Hispanic and to identify as bisexual, and less likely to identify as exclusively lesbian than participants interviewed before the bill signed or passed.

3.2 Stigma Consciousness, Perceived Discrimination, and Depressive Symptoms

Table 2 presents results related to stigma consciousness, perceived discrimination, and depressive symptoms. We first discuss the direct effects of Civil Union legislation followed by results of the tests for interaction effects. Participants interviewed after bill enactment had lower levels of stigma consciousness (B = −0.18, p < 0.01; Eta2=0.02 [Total Model Eta2=0.07) and lower levels of perceived discrimination (B = −0.26, p < 0.10) than those interviewed before enactment. Women interviewed after the bill’s passage reported fewer past-week depressive symptoms compared to those interviewed before the bill was passed (B = −1.12, p< 0.10; Eta2=0.01 [Total Model Eta2=0.10), but bill enactment had no effect on past-week depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Betas from regressions for the effects of civil union passage on stigma consciousness, perceived discrimination, and depressive symptoms

| Panel A: Stigma consciousness | Panel B: Discrimination | Panel C: Depressive symptoms | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Civil union legislation | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-legislation (ref.) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Bill signed | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.14 | 0.08† | −0.20 | 0.14 | −0.09 | 0.17 | −0.20 | 0.32 | −0.25 | 0.33 | −1.12 | 0.65† | −2.12 | 0.79** | −0.48 | 1.41 |

| Bill enacted | −0.18 | 0.05*** | −0.24 | 0.07*** | −0.43 | 0.13*** | −0.26 | 0.15† | −0.31 | 0.20 | −0.37 | 0.32 | −0.18 | 0.56 | −0.26 | 0.72 | 2.17 | 1.36† |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||||

| Black/Latina (ref.) | ||||||||||||||||||

| White | 0.06 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.08† | −0.06 | 0.06 | 0.50 | 0.14** | 0.40 | 0.22† | −0.52 | 0.15** | 1.10 | 0.55* | 0.34 | 0.82 | −1.16 | 0.55* |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.00** | −0.01 | 0.00** | −0.01 | 0.00** | −0.03 | 0.01*** | −0.02 | 0.00*** | −0.03 | 0.01*** | −0.03 | 0.02† | −0.03 | 0.02* | −0.04 | 0.02 |

| Education | ||||||||||||||||||

| High school or less (ref.) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Some college | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.07 | −0.16 | 0.13 | −0.22 | 0.17 | −0.12 | 0.18 | −0.23 | 0.29** | −1.45 | 0.69* | −1.60 | 0.68* | 0.08 | 1.25 |

| College graduate | 0.17 | 0.07* | 0.15 | 0.07* | −0.02 | 0.12 | −0.59 | 0.19** | −0.51 | 0.19** | −0.82 | 0.31** | −2.99 | 0.72*** | −3.13 | 0.72*** | −1.77 | 1.26 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||||||||||||||||||

| Exclusively lesbian (ref.) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mostly lesbian | 0.13 | 0.06† | 0.12 | 0.07† | 0.13 | 0.06* | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.17 | −0.47 | 0.68 | −0.52 | 0.67 | −0.58 | 0.68 |

| Bisexual | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.06† | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.16 | −0.01 | 0.16 | 1.29 | 0.62* | 1.17 | 0.62* | 1.01 | 0.62† |

| Relationship status | ||||||||||||||||||

| In a relationship (ref.) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Widowed/separated | −0.02 | 0.23 | −0.01 | 0.12 | −0.02 | 0.12 | 0.47 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.30 | 3.22 | 1.21** | 3.06 | 1.21** | 3.19 | 1.21** |

| Single | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.14 | −0.04 | 0.41 | −0.07 | 0.14 | 1.29 | 0.62* | 1.34 | 0.52** | 1.32 | 0.52* |

| Kid in house | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.16† | 0.26 | 0.16† | 0.29 | 0.16† | 0.76 | 0.61 | 0.83 | 0.61 | −0.73 | 0.61 |

| Bill signed × White | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.36 | 3.26 | 1.39* | ||||||||||||

| Bill enacted × White | 0.17 | 0.11† | 0.14 | 0.29 | 0.41 | 1.11 | ||||||||||||

| Bill signed × some college | 0.13 | 0.18 | −0.35 | 0.44 | −1.81 | (1.77) | ||||||||||||

| Bill enacted × some college | 0.33 | 0.17* | 0.15 | 0.41 | −2.52 | (1.66) | ||||||||||||

| Bill signed × college graduate | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.68 | 0.42 | 0.57 | (1.72) | ||||||||||||

| Bill enacted × college graduate | 0.31 | 0.16* | 0.14 | 0.40 | −2.95 | (1.57)† | ||||||||||||

Source: Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women Survey; N =517

Notes:

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001;

SE =Standard Error; Regression type in parentheses; N =517

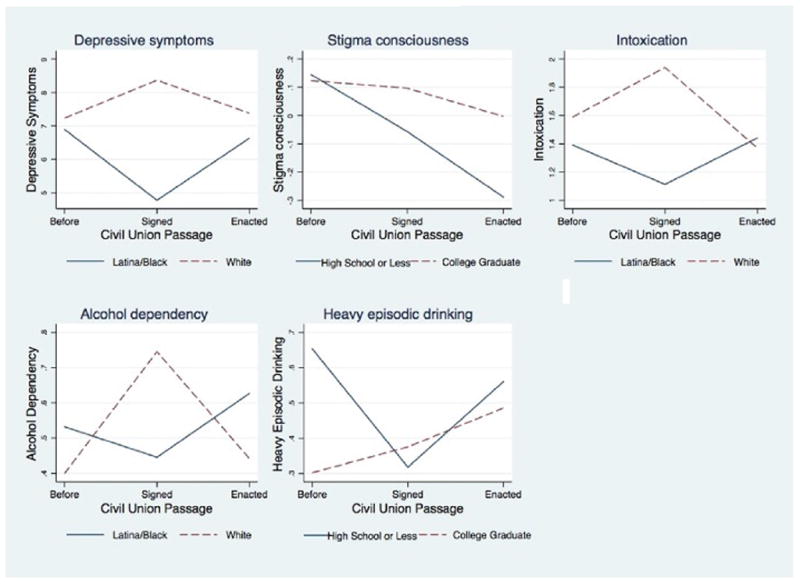

The interactions presented in Models 2 and 3 for our outcomes of interest are sometimes contingent upon sociodemographic characteristics. Panel B, Model 2 demonstrates Black and Latina women interviewed after civil union legislation passed reported significantly fewer depressive symptoms than those who were interviewed before the bill was passed (B = −2.12, p < 0.01) and fewer than White participants interviewed after the bill was passed (B = −2.12 + 3.67, p < 0.01, Eta2=0.02 [Total Model Eta2=0.11]) 5 (see Figure 1). The effect of legislation on stigma consciousness and perceived discrimination did not vary by race/ethnicity.

Fig. 1.

Predicted scores for selected outcomes by civil union legislation status.

Results from education and civil union bill status interactions are presented in Model 3 of Panels A, B, and C. Civil union bill enactment was associated with lower levels of stigma consciousness for women with high school education or less (B = −0.43, p < 0.001; Eta2=0.03 [Total Model Eta2=0.08]), but not for participants with some college (B = −0.43 + 0.33, p<.05; Eta2=0.01) or those with advanced degrees (B =−0.43 + 0.31, p<.05; Eta2=0.01) (see Figure 1). Interactions between education and legislation were not significant for discrimination or depressive symptoms.

3.3 Hazardous Drinking

Table 3 summarizes results from logistic and Poisson regressions that tested the relationship between civil union bill status and four indicators of hazardous drinking. Results suggest an increase in heavy episodic drinking (Panel A) among participants interviewed after the bill was enacted (B = 0.45, p < 0.05), but participants interviewed after the bill was signed (B = −0.57, p < 0.001) and after it was enacted (B = −0.33, p < 0.05) reported fewer negative consequences of alcohol use (Panel D) compared to those interviewed before legislation was signed.

Table 3.

Betas from regressions for the effects of civil union passage on hazardous drinking indicators

| Panel A: Heavy episodic drinking (Logistic) | Panel B: Intoxication (Poisson) | Panel C: Alcohol dependency (Poisson) | Panel D: Adverse drinking consequences (Poisson) | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||||||||

| β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Civil union legislation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-legislation (ref.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bill signed | −0.07 | 0.27 | −0.27 | 0.48 | −1.23 | 0.65* | −0.10 | 0.10 | −0.22 | 0.13† | −0.32 | 0.18† | 0.05 | 0.17 | −0.17 | 0.21 | −0.35 | 0.31 | −0.57 | 0.18*** | −0.73 | 0.22*** | −0.67 | 0.29* |

| Bill enacted | 0.45 | 0.23* | 0.68 | 0.30* | −0.08 | 0.62 | −0.04 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.11 | −0.07 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.17 | −0.12 | 0.30 | −0.33 | 0.14* | −0.36 | 0.17* | −0.37 | 0.26 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Black/Latina (ref.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| White | 0.10 | 0.23 | −0.17 | 0.35 | −0.06 | 0.24 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.09 | −0.15 | 0.15 | −0.29 | 0.26 | −0.16 | 0.16 | −0.01 | 0.15 | −0.13 | 0.22 | −0.01 | 0.15 |

| Age | −0.06 | 0.08*** | −0.06 | 0.00*** | −0.06 | 0.01*** | −0.04 | 0.00*** | −0.04 | 0.00*** | −0.04 | 0.00*** | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.01*** | −0.03 | 0.01*** | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.01 |

| Education | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| High school or less (ref.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Some college | −0.63 | 0.28* | −0.69 | 0.28* | −1.27 | 0.59* | −0.39 | 0.10*** | −0.42 | 0.10*** | −0.45 | 0.17** | −0.40 | 0.15** | −0.45 | 0.15** | −0.69 | 0.27* | −0.48 | 0.16** | −0.50 | 0.16*** | −0.46 | 0.25† |

| College graduate | −0.55 | 0.29† | −0.57 | 0.29† | −1.58 | 0.58** | −0.44 | 0.11*** | −0.46 | 0.11*** | −0.59 | 0.17* | −0.71 | 0.18*** | −0.74 | 0.18*** | −1.09 | 0.31*** | −0.54 | 0.18** | −0.56 | 0.18** | −0.66 | 0.27* |

| Sexual Orientation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Exclusively lesbian (ref.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mostly lesbian | 0.69 | 0.28* | 0.67 | 0.28* | 0.80 | 0.29** | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.43 | 0.18* | 0.42 | 0.18* | 0.45 | 0.18* | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.19 |

| Bisexual | −0.04 | 0.25 | −0.08 | 0.25 | −0.02 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.90** | 0.23 | 0.13+ | 0.23 | 0.09** | 0.81 | 0.14*** | 0.76 | 0.14*** | 0.82 | 0.15*** | 0.70 | 0.14*** | 0.68 | 0.14*** | 0.69 | 0.15*** |

| Relationship status | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In a relationship (ref.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Widowed/separated | 0.61 | 0.49 | 0.63 | 0.49 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.17** | 0.54 | 0.17** | 0.52 | 0.17** | 0.73 | 0.26** | 0.73 | 0.26** | 0.71 | 0.26** | 0.91 | 0.24*** | 0.90 | 0.24*** | 0.89 | 0.24*** |

| Single | 0.44 | 0.22* | 0.49 | 0.22* | 0.50 | 0.23* | 0.15 | 0.08* | 0.18 | 0.08* | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| Kid in house | −0.52 | 0.26* | −0.52 | 0.26* | −0.65 | 0.28* | −0.02 | 0.10 | −0.02 | 0.10 | −0.03 | 0.10 | −0.43 | 0.18 | −0.43 | 0.18* | −0.44 | 0.18 | −0.37 | 0.18* | −0.36 | 0.18† | −0.37 | 0.18† |

| Bill signed × White | 0.75 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.21* | 0.81 | 0.37* | 0.57 | 0.38 | ||||||||||||||||

| Bill enacted × White | −0.45 | 0.47 | 0.18 | 0.18 | −0.06 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.29 | ||||||||||||||||

| Bill signed × some college | 2.01 | 0.76* | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.53 | 0.40 | 0.01 | (0.43) | ||||||||||||||||

| Bill enacted × some college | 0.79 | 0.70 | −0.02 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.34 | −0.06 | (0.33) | ||||||||||||||||

| Bill signed × college graduate | 2.04 | 0.75** | 0.44 | 0.25† | 0.74 | 0.43† | 0.33 | (0.43) | ||||||||||||||||

| Bill enacted × college graduate | 1.38 | 0.66* | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.17 | (0.35) | ||||||||||||||||

Source: Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women Survey

Notes:

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001;

SE =Standard Error; Regression type in parentheses; N =517

Interactions with race/ethnicity show that Black and Latina women interviewed after the bill was signed reported significantly fewer experiences of intoxication (Panel B, Model 3: B = −0.21, p < 0.10) compared to White women interviewed after the bill was signed (B = −0.21 + 0.42, p<.05). Results from Panel C, Model 2 showed no effect of legislation on alcohol dependence symptoms for Black or Latina participants, but White participants interviewed after civil union legislation was passed reported a significant increase in alcohol dependence symptoms compared to Whites interviewed before the bill was signed (B = 0.81, p < 0.05) (see Figure 1).

Education interactions reveal that participants with a high school education or less reported a significant decrease in heavy episodic drinking after the bill was signed (B = −1.23, p < 0.05), a result not found among participants who had some college (B = −1.23 + 2.01, p < 0.05) or college degrees (B = −1.23 + 2.04, p < 0.05) (see Figure 1). No other significant education interactions were found for the drinking outcomes.

4. Discussion

We capitalized on a quasi-natural experiment to examine the impact of state legislation legalizing same-sex civil unions on minority stressors (stigma consciousness and perceived discrimination), depressive symptoms, and four indicators of hazardous drinking in a diverse sample of SMW. In addition, we expanded the range of measures of health behaviors and psychosocial factors that could be plausibly affected by these policy-level changes, including individual-level measures of minority stress and hazardous drinking, which are disproportionately elevated among SMW relative to heterosexual women (Hughes et al., 2010a,b). Further, although theories of intersectionality posit that the lived experiences of multiply disadvantaged individuals are different from their peers who share a single minority status (Bowleg, 2008; Warner & Shields 2013), previous research has not examined whether the effect of civil union legislation varies by race/ethnicity or educational level.

For four of our seven outcomes—stigma consciousness, perceived discrimination, depressive symptoms, and adverse drinking consequences—civil union legislation in Illinois was associated with better outcomes in the full sample of SMW. However, some of these benefits appeared to be contingent upon education and race/ethnicity. In particular, women of color and women with a high school education or less reported greater reductions in stigma consciousness associated with civil union legislation compared to White women and to women with college degrees. Similarly, the positive effects of civil union legislation on depressive symptoms were concentrated among women of color, and the beneficial effects of civil union legislation on hazardous drinking were concentrated among women of color and those with lower levels of education (with the exception of adverse drinking consequences, which were reduced for all SMW in the sample).

Two findings did not follow this trend. First, civil union legislation was associated with increases in reporting heavy episodic drinking among the full sample. Relatedly, we did not find a significant relationship between civil union legislation and intoxication or symptoms of potential alcohol dependence for the total sample. It may be that determinants of alcohol use-related behaviors are further ‘downstream’ from the immediate benefits of reduced stigma related to civil union legislation, and therefore less responsive in the short-term. Additionally, our indicators of hazardous drinking are based on a 12-month timeframe making it possible that some reports related to hazardous drinking were based on experiences that occurred prior to legislative changes. Finally, the effects of civil union legislation on perceived discrimination and adverse drinking consequences did not vary by either race/ethnicity or education, suggesting that civil union legislation benefitted all women in the sample. These results notwithstanding, our findings provide evidence that for many outcomes, Black and Latina SMW and SMW who have lower levels of education may benefit more from anti-discriminatory policies than White SMW or SMW with higher educational attainment.

Our results also suggest a time-sensitive effect of civil union legislation on minority stress and health. For example, civil union legislation reduced stigma consciousness and perceived discrimination after enactment, but not after the bill was signed. In contrast, the positive effects of civil union legislation on depression and hazardous drinking occurred after the bill was signed and before it was enacted, suggesting it had an immediate beneficial impact on the mental health of SMW. In the case of the bill’s signing and its enactment, benefits were observed before respondents would have been able to access the material benefits associated with legally recognized relationships. Thus, it is not simply the economic barriers put in place by discriminatory social policies that impact the health of stigmatized groups, but also the messages that such policies communicate to the stigmatized citizens they target, which in turn influence individual-level stigma processes. Our study findings add to the small but growing body of research documenting the ways in which macro-level factors, such as discriminatory social policies, influence individual-level health (Hatzenbuehler, 2014).

Studies with longer follow-up periods are needed to examine the longer-term health consequences of these policy changes. Protective policies such as legal same-sex civil unions do not guarantee that SMW will not experience other forms of discrimination (e.g., housing or employment discrimination). However, such policies may signal that the state is less complicit in or tolerant of sexual orientation-related discrimination (Hatzenbuehler, 2010) and may therefore result in a reduction of overall discrimination that benefits all SMW, not just those who enter into civil unions with same-sex partners (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2012). In support of this hypothesis, we tested interactions between civil union legislation and current relationship status (results not shown but available upon request), which, with one exception (single women reported fewer depressive symptoms after legislation was signed than single women prior to legislations), did not yield significant results, indicating that the legislation had comparable effects for both partnered and non-partnered SMW. Such a finding suggests that the short-term effects of these policies may be tied to psychosocial factors related to stigma processes, rather than to the concrete financial or material benefits afforded by a legally-recognized relationship.

4.1 Limitations

The study has several limitations. Because data collection coincided with Illinois’ civil union legislation but was not originally intended to capture effects of the legislation, we were unable to assess whether the study outcomes were the direct result of the civil union legislation or whether other coterminous factors with the policy change may account for the results. For example, it is possible that some of the improvements in health were related to an overall general increase in LGBT visibility and acceptance. These general changes, however, should impact the entire sample in a similar way, yet we found significant differences between groups of SMW interviewed over a short time-frame. In particular, significant differences between women interviewed before the bill was passed and those interviewed in the four-month window following the bill’s passage strongly suggests that observed changes are linked to Illinois’ civil union legislation. Further, our results may also be influenced by the fact that SMW interviewed after the bill was signed and enacted were more likely to be racial/ethnic minorities and less likely to be college educated; thus, we were unable to ensure equal representation among all sub-groups over the three time periods analyzed. Nevertheless, we have no evidence that our outcomes would be biased by this distribution. It is also possible that the unequal distribution may have reduced statistical power. The subpopulations most impacted by this variation, however, would be those with lower levels of education, yet we found statistically significant interactions for those without college degrees.

We also lacked a heterosexual comparison group, which would have allowed us to determine whether the health-related benefits of civil union legislation were specific to sexual minorities, though we note that prior work has shown this to be the case (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2010). Further, two of our measures, stigma consciousness and sexual orientation-based perceived discrimination, are not relevant for heterosexual populations. We also lacked baseline measures prior to legislative change for our dependent variables, which prevented us from controlling for prior levels of the outcomes. We also combine Black and Latina respondents in our analysis and exclude other race/ethnic groups. While in our analysis, no differences were detected between Black and Latina respondents, future studies may benefit from examining these groups uniquely and including more diverse samples. Additionally, we use education as an indicator of SES, however, future research should investigate whether our findings hold using other indicators such as income or occupation.

The study is also limited in its generalizability, given that the sample was obtained using nonprobability methods in a geographically restricted area (the greater Chicago metropolitan area). At the same time, there are very few probability-based studies that assess sexual orientation; further, it is often quite difficult to obtain baseline data before policies change. Consequently, our sample offers one of the few available opportunities to examine the impact of supportive policies on SMW’s mental health. Finally, our analyses focus on identity as the measure of sexual orientation and therefore may not be generalizable to SMs defined using other indicators of sexual orientation, such as attraction or behavior.

4.2 Conclusion

Despite these limitations, the results suggest that discriminatory policies affect the health of sexual minorities, and this may be particularly true for those with other marginalized statuses.

Although there have been unprecedented advancements in civil rights for SM people over the past decade, including the recent the repeal of the Defense of Marriage Act, in many states it is still legal to fire individuals based upon their sexual orientation or gender identity. The results presented here suggest that the impact of anti-discriminatory policies is twofold: not only do supportive policies improve the health of SMW, but changes in legislation that address the civil rights of SMs may disproportionately benefit SMW who are members of multiply disadvantaged groups. By documenting the health benefits of inclusive and protective policies, this research provides additional evidence using a quasi-natural experiment that social policies can be effective in improving individual-level health of SMW.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS.

We examine effects of civil union legislation on sexual minority women’s health.

Policy change was linked to lower levels of stigma, discrimination, and depression.

Policy change was also associated with lower levels of hazardous drinking.

Health benefits were concentrated among women of color and with lower education.

Anti-discriminatory policies can improve the health of stigmatized populations.

Footnotes

Results from supplementary factor analysis using both Kaiser and Scree tests show that items load onto a single factor for both the bisexual and lesbian stigma consciousness scale.

Questions allow respondents to report discrimination for a single reason or multiple reasons, including sexual orientation, gender, and/or race/ethnicity. Supplementary analyses that considered reports of discrimination for any reason, including only racial/ethnic discrimination, yielded similar results. To focus our measure on sexual- or gender-specific minority stressors, we excluded discriminatory experiences that were reported as being only the result of minority race/ethnicity.

Analyses examining potential differences between Black and Latina participants showed no statistically significant differences in the two groups on any of the study outcome measures.

Models are robust to the inclusion of income as a covariate.

Results presented in parenthesis include the direct effect of legislation plus the interaction effect between legislation and educational status.

Contributor Information

Bethany G. Everett, University of Utah, USA

Mark L. Hatzenbuehler, Columbia University, USA

Tonda L. Hughes, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA

References

- Badgett MVL. Social inclusion and the value of marriage equality in Massachusetts and the Netherlands. Journal of Social Issues. 2011;67(2):316–334. [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Molina Y, Beadnell B, Simoni J, Walters K. Measuring multiple-minority stress: The LGBT people of color microaggressions scale. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17(2):163–174. doi: 10.1037/a0023244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(3):497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick W. Assessing bisexual stigma and mental health status: A Brief Report. Journal of Bisexuality. 2012;12(2):214–222. doi: 10.1080/15299716.2012.674860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. When Black + lesbian + woman ≠ Black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles. 2008;59(5–6):312–325. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—An important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(7):1267–1273. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breines W. What’s love got to do with it? White women, Black women, and feminism in the movement years. Signs. 2002;27(4):1095–1133. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL. The effect of union type on psychological well-being: Depression among cohabitors versus marrieds. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(3):241–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne I, Misra J. The intersection of gender and race in the labor market. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003;29(1):487–513. [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Han C, Paul J, Ayala G. Strategies of managing racism and homophobia among U.S. ethnic and racial minority men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2011;23(2):145–158. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermody SS, Marshal MP, Cheong J, Burton C, Hughes T, Aranda F, Friedman MS. Longitudinal disparities of hazardous drinking between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 43(1):30–39. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9905-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Goldfried MR, Davila J. The relationship between experiences of discrimination and mental health among lesbians and gay men: An examination of internalized homonegativity and rejection sensitivity as potential mechanisms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(5):912–927. doi: 10.1037/a0029425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerhut AW, Riggle EDB, Rostosky SS. Same-sex marriage: The social and psychological implications of policy and debates. Journal of Social Issues. 2011;67(2):225–41. [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(2):216–221. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman TA. The social psychological costs of racial segmentation in the workplace: A study of African Americans’ well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44(3):332–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass VQ, Few-Demo AF. Complexities of informal social support arrangements for Black lesbian couples. Family Relations. 2013;62(5):714–726. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. Social factors as determinants of mental health disparities in LGB populations: Implications for public policy. Social Issues and Policy Review. 2010;4(1):31–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. Structural stigma and the health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2014;23(2):127–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, O’Cleirigh C, Grasso C, Mayer K, Safren S, Bradford J. Effect of same-sex marriage laws on health care use and expenditures in sexual minority men: A quasi-natural experiment. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(2):285–291. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(3):452–459. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Corbin WR, Fromme K. Discrimination and alcohol-related problems among college students: A prospective examination of mediating effects. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;115(3):213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Legal recognition of same-sex relationships in the United States: A social science perspective. American Psychologist. 2006;61(6):607–621. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.6.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, McCabe SE, Wilsnack SC, Boyd C, West BT. Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. Addiction. 2010;105:2130–2140. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, Szalacha L, Johnson TP, Kinnison K, Wilsnack SC, Cho YI. Sexual victimization and hazardous drinking among heterosexual and sexual minority women. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(12):1152–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, Wilsnack SC, Kantor LW. The influence of gender and sexual orientation on alcohol use and alcohol-related problems. Alcohol Research Current Reviews. 2016;38(1):121–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandaswamy P. State Austerity and the Racial Politics of Same-Sex Marriage in the US. Sexualities. 2008;11(6):706–725. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(7):1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt HM, Ovrebo E, Anderson-Cleveland MB, et al. Balancing Dangers: GLBT Experience in a Time of Anti-GLBT Legislation. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56(1):67–81. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995:80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Reczek C, Brown D. Same-sex cohabitors and health: The role of race-ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2013;54(1):25–45. doi: 10.1177/0022146512468280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisel NC, Fingerhut AW. California’s ban on same-sex marriage: The campaign and its effects on gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Social Issues. 2011;67(2):242–63. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith HA, McGinley J, … Brent DA. Suicidality and Depression Disparities Between Sexual Minority and Heterosexual Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49(2):115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, King KM, Miles J, Gold MA, … Morse JQ. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: a meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction. 2008;103(4):546–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, West BT, Boyd CJ. The relationship between discrimination and substance use disorders among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(10):1946. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(11):1869. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell S, Meyer IH, Schwartz S. Increased risk of suicide attempts among Black and latino lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(6):1055–1059. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinel EC. Stigma consciousness: The psychological legacy of social stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76(1):114. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rieger G, Savin-Williams RC. Gender nonconformity, sexual orientation, and psychological well-being. Archives of sexual behavior. 2011:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9738-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggle EDB, Rostosky SS, Horne SG. Psychological distress, well-being, and legal recognition in same-sex couple relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24(1):82. doi: 10.1037/a0017942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Sex differences in the effect of education on depression: Resource multiplication or resource substitution? Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63(5):1400–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky SS, Riggle EDB, Horne SG, Miller AD. Marriage amendments and psychological distress in lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56(1):56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Rothblum ED, Balsam KF, Solomon SE. Narratives of same-sex couples who had civil unions in Vermont: The impact of legalizing relationships on couples and on social policy. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2011;8(3):183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin MS, Colen CG, Link BG. Examination of inequalities in HIV/AIDS mortality in the United States from a fundamental cause perspective. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(6):1053–1059. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R. Revisiting the relationships among gender, marital status, and mental health. American Journal of Sociology. 2002;107(4):1065–1096. doi: 10.1086/339225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Kashubeck-West S. Mediators of the relationship between internalized oppressions and lesbian and bisexual women’s psychological distress. The Counseling Psychologist. 2008;36(4):525–574. [Google Scholar]

- Warner LR, Shields SA. The intersections of sexuality, gender, and race: Identity research at the crossroads. Sex Roles. 2013;68(11–12):803–810. [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack SC, Wilsnack RW, Kristjanson AF, Vogeltanz Holm ND, Windle M. Alcohol use and suicidal behavior in women: Longitudinal patterns in a US national sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28(S1):38S–47S. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200405001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]