Summary

Neural circuit wiring relies on selective synapse formation whereby a presynaptic release apparatus is matched with its cognate postsynaptic machinery. At metabotropic synapses, the molecular mechanisms underlying this process are poorly understood. In the mammalian retina, rod photoreceptors form selective contacts with rod ON-bipolar cells by aligning the presynaptic voltage-gated Ca2+ channel directing glutamate release (CaV1.4) with postsynaptic mGluR6 receptors. We show this coordination requires an extracellular protein, α2δ4, which complexes with CaV1.4 and the rod synaptogenic mediator, ELFN1, for trans-synaptic alignment with mGluR6. Eliminating α2δ4 in mice abolishes rod synaptogenesis, synaptic transmission to rod ON-bipolar cells, and disrupts postsynaptic mGluR6 clustering. We further find that in rods α2δ4 is crucial for organizing synaptic ribbons and setting CaV1.4 voltage sensitivity. In cones, α2δ4 is essential for CaV1.4 function, but is not required for ribbon organization, synaptogenesis, or synaptic transmission. These findings offer insights into retinal pathologies associated with α2δ4 dysfunction.

eTOC

The authors identify a critical molecule that plays an essential role for wiring rod photoreceptors into the retinal circuitry. They show that the development of rod presynaptic compartments requires the α2δ4 protein, which recruits the synaptogenic mediator ELFN1 to enable synapse formation.

Introduction

The assembly of neural circuits is fundamental for information processing by the nervous system and relies on the establishment of selective synaptic contacts between individual neurons (Bargmann and Marder, 2013; Zipursky and Sanes, 2010). At the molecular level, the formation of synapses involves the action of cell surface molecules that engage in trans-synaptic interactions linking pre- and post-synaptic specializations through homophilic or heterophilic interactions with one another and/or with neurotransmitter receptors (de Wit et al., 2011; Margeta and Shen, 2010). This process has been well studied for excitatory ionotropic synapses (Sudhof, 2008; Williams et al., 2010). However, the mechanistic basis for the assembly of the metabotropic synapses, where signaling is mediated by the GPCRs, remains virtually unexplored.

The vertebrate retina is an excellent model for unraveling mechanisms involved in the formation of metabotropic synapses, and for understanding their relevance for information processing and behavior (Dunn and Wong, 2014; Sanes and Zipursky, 2010). Vision is initiated by photoreceptor cells, rods and cones, which make selective contacts with distinct classes of bipolar neurons (Sanes and Zipursky, 2010). Cone photoreceptors, which detect a wide range of light intensities, make contacts with two broad types of the downstream interneurons, ON and OFF cone bipolar cells (ON-CBCs and OFF-CBCs, respectively). In contrast, rod photoreceptors, which are exquisitely tuned for the detection of single photons, wire predominantly with a dedicated synaptic partner, ON rod bipolar cells (ON-RBCs). While OFF-CBCs use ionotropic glutamate receptors to sense light-dependent reductions in glutamate release from the photoreceptors, ON-BCs in the mammalian retina instead use the metabotropic glutamate receptor, mGluR6 (Vardi and Dhingra, 2014). Disruptions in synaptic communication between rods and ON-RBCs cause inherited forms of night blindness in humans (Zeitz et al., 2015), a condition recapitulated in several mouse models of the disease (Pardue and Peachey, 2014).

Several molecules with essential roles in rod to ON-RBC synapse formation have been identified. On the postsynaptic side, mGluR6 is required not only for generating the depolarizing response in ON-RBCs, but also for establishing physical contacts with rods (Cao et al., 2009; Tsukamoto and Omi, 2014). Recently we have reported that mGluR6 is engaged in a direct trans-synaptic contact with the rod-specific cell adhesion molecule ELFN1, and that this interaction is required for rod-to-ON-RBC synapse formation (Cao et al., 2015). On the presynaptic side, rod synaptogenesis also requires the voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channel, CaV1.4 (Mansergh et al., 2005), which couples light-induced changes in membrane potential to changes in glutamate release by the rod axonal terminal, or spherule (Barnes and Kelly, 2002; Heidelberger et al., 2005). Interestingly, either the blockade of glutamate release or knockout of CaV1.4 abolishes the synaptic targeting of ELFN1 (Cao et al., 2015), suggesting that the CaV1.4 complex may link the transmitter release apparatus to machinery that mediates rod synaptogenesis.

Voltage-gated calcium channels form macromolecular complexes with several proteins (Catterall, 2010; Muller et al., 2010). Among their prominent binding partners are α2δ proteins: extracellular multimodal molecules that are often described as auxiliary CaV subunits (Dolphin, 2013). These proteins are thought to act mainly by promoting CaV surface expression (Cassidy et al., 2014; D’Arco et al., 2015; Hoppa et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2015). However, their effects on the biophysical properties of the CaV channels are controversial and were reported mostly in heterologous overexpression systems (Bangalore et al., 1996; Felix et al., 1997; Fell et al., 2016; Singer et al., 1991). In addition, α2δ proteins have been implicated in synapse formation, acting independently from but possibly in cooperation with CaV channels (Eroglu et al., 2009; Kurshan et al., 2009). The molecular mechanisms by which α2δ family members exert synaptogenic effects remain largely unknown.

Rod and cone photoreceptors have been shown to express selectively the α2δ4 type, which forms complexes with CaV1.4 channels at synaptic ribbons (De Sevilla Muller et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2015). Several observations suggest that α2δ4 may play an important role in the function of photoreceptors. First, human mutations in α2δ4 have been associated with a cone dystrophy accompanied by night blindness, typically associated with deficits in rod synaptic transmission (Ba-Abbad et al., 2016; Wycisk et al., 2006b). In accordance with these studies, α2δ4 mutations in mice also result in diminished light-evoked responses accompanied by morphological changes in the synaptic layer where photoreceptors make contacts with ON-BCs (Caputo et al., 2015; Ruether et al., 2000; Wycisk et al., 2006a). However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of α2δ4 on CaV1.4 function, as well as its role in rod synaptogenesis and synaptic transmission remain unclear.

Here we show that α2δ4 is essential for rod synaptogenesis and selective wiring of these photoreceptors into the retinal circuitry. Elimination of α2δ4 in mice abolishes the recruitment of the key synaptogenic molecule, ELFN1, to synaptic terminals preventing rods from establishing physical contacts with and transmitting their light-evoked signals to ON-RBCs. We have further found that α2δ4 regulates the number of functional CaV1.4 channels and their biophysical properties in intact rod spherules and we document the role of α2δ4 in the organization of active zone and morphology of axonal terminals. Remarkably, we demonstrate that although α2δ4 also affects cone signaling, it is not required for synaptic transmission to ON- or OFF-CBCs.

Results

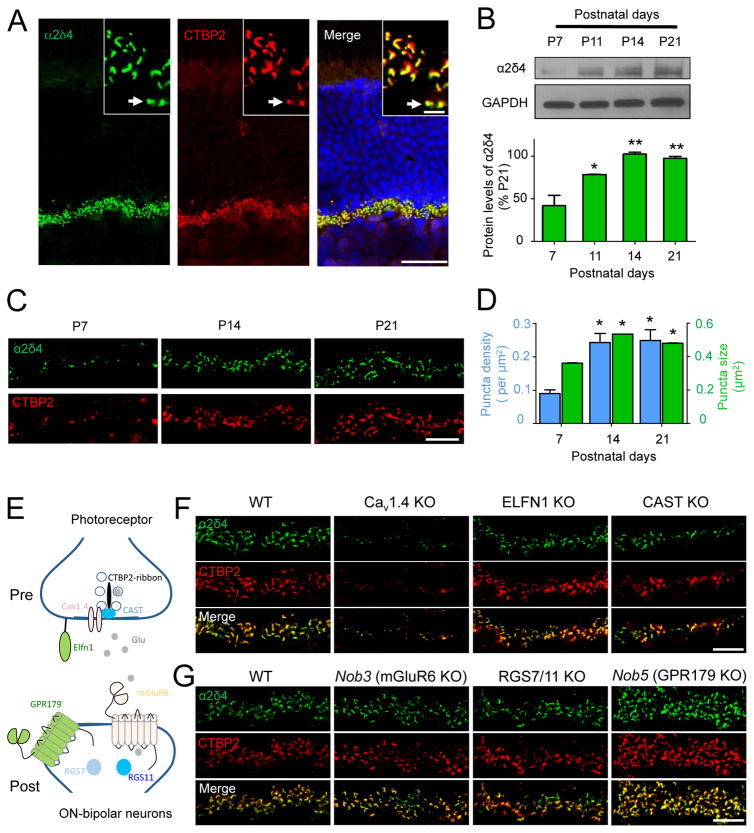

α2δ4 protein is induced at the peak of the photoreceptor synaptogenesis and targeted to synapses independently from synapse formation

To probe the role of α2δ4 in photoreceptor synaptogenesis, we studied its expression during retinal development. We found that in mature retinas α2δ4 is localized to the synaptic ribbons of rod and cone synaptic terminals (Fig. 1A), consistent with a recent study (Lee et al., 2015). Analysis of α2δ4 protein expression in whole retinas by immunoblotting revealed that it became detectable at P7 and rapidly doubled in level by P14 (Fig. 1B), coinciding with the main period of photoreceptor synaptogenesis. This level of expression was maintained in mature P21 retinas. We further examined morphological changes in α2δ4 content in the outer plexiform layer (OPL), where photoreceptors form synapses with ON-BCs (Fig. 1C). The α2δ4 signal was present as early as synaptic ribbons are discernible (~P7). Again, we observed a substantial increase in recruitment of α2δ4 to the ribbons as evidenced by growth in both number and size of the synaptic puncta at P14 (Fig. 1C,D). The developmental dynamics of α2δ4 is thus consistent with its involvement in synapse formation.

Figure 1. Relationship of α2δ4 to synapse development and key molecules at photoreceptor ribbon synapses.

A, Localization of α2δ4 at photoreceptor synapses. (scale bar, 25 μm). Insert shows the outer plexiform layer (OPL) at higher magnification (scale bar, 5μm). Arrow points to cone synapses. B, Quantification of changes in α2δ4 protein levels during synaptogenesis by Western blotting. Protein samples from different WT and KO retinas were loaded on the same gel alternately. Error bars are SEM values, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, n=3 mice, One-way ANOVA. C, Analysis of α2δ4 accumulation at ribbon synapses of photoreceptors in the OPL during development. D, Quantification of changes α2δ4 accumulation at synapses. The total number of puncta selected was 69, 195, and 202 for P7, P14, and P21, respectively. Images of two different sections of each retina and two retinas from different mice at each stage were used for analysis. Error bars are SEM values, *p<0.05, One-way ANOVA. E, Scheme illustrating identity and localization of key molecules at photoreceptor synapses. F, Effect of eliminating key pre-synaptic molecules on expression and localization of α2δ4 at the ribbon synapses. G, Effect of eliminating key post-synaptic molecules on expression and localization of α2δ4 at the ribbon synapses. In C, F, G, scale bar is 10μm; retinas used are from 1–4 month old mice.

In functional photoreceptor synapses, several molecules critical for synaptic transmission and synapse assembly are accumulated at pre- and post-synaptic sites (Fig. 1E). We examined the effect of ablating these key players on the expression and synaptic targeting of α2δ4. Presynaptically, we found that elimination of the active zone component CAST (tom Dieck et al., 2012), or the synaptogenic molecule ELFN1 (Cao et al., 2015), had no effect on either the abundance or localization of α2δ4 to synaptic ribbons (Fig. 1F). In contrast, knockout of CaV1.4 channels dramatically reduced levels of α2δ4 at synapses, indicating that the majority of α2δ4 is associated with the CaV1.4 complex and that CaV1.4 plays an important role in setting the abundance of α2δ4 (Fig. 1F). We further examined the impact of abolishing glutamate release by expressing tetanus toxin (TENT) in photoreceptors, a manipulation that prevents assembly of functional photoreceptor synapse (Cao et al., 2015). In addition to the previously noted deterioration of ribbon size and shape (Cao et al., 2015), we observed that TENT expression caused corresponding changes in the pattern of CaV1.4 immunoreactivity, yet its localization at the ribbons was not compromised (Suppl. Fig. S1). Interestingly, besides similar changes in shape, immunoreactivity of α2δ4 was substantially reduced, yet it was still clearly present at the ribbons, suggesting that its synaptic targeting occurs independently of neurotransmitter release. Postsynaptically, ablation of either the orphan receptor GPR179 or the key signaling regulators RGS7 and RGS11, which both disrupt synaptic transmission, failed to affect significantly the expression and localization of α2δ4 (Fig. 1G). Furthermore, the knockout of mGluR6, which abolishes the postsynaptic response of ON-BCs and formation of synapses with photoreceptors, also did not alter α2δ4 content at synapses (Fig. 1G). Together, these results indicate that association of α2δ4 with synaptic ribbons occurs autonomously from the physical synapse formation, or the association with key components mediating synaptic transmission, suggesting that it could be a higher order candidate in the hierarchy of synaptic assembly.

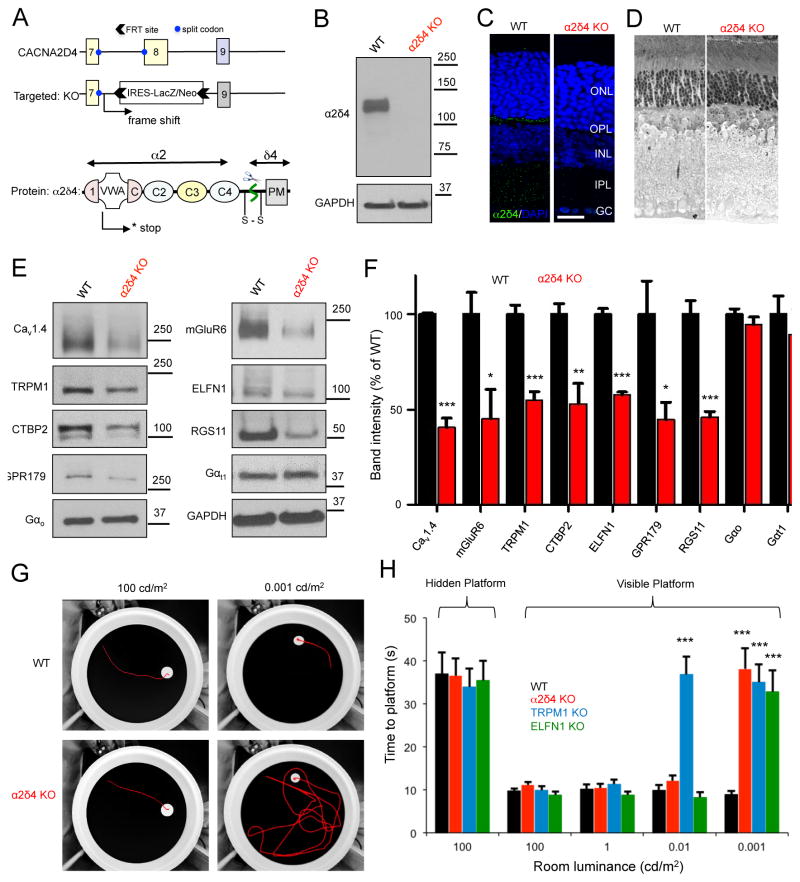

Elimination of α2δ4 in mice diminishes dim light vision and compromises expression of key mediators of synaptic transmission

To understand the role of α2δ4 in synapse assembly and photoreceptor function, we have obtained a mouse model with a complete elimination of α2δ4 protein. In this model, the CACNA2D4 gene is disrupted by homologous recombination, eliminating exon 8 by replacing it with the LacZ/Neo cassette (Fig. 2A). This modification is predicted to introduce an early frameshift mutation that terminates the translation of the message in the middle of the first integrated Cache 1-VWA module, essentially eliminating all structural elements of the α2δ4 protein (Fig. 2A). α2δ4 knockout (KO) mice were bred to homozygosity and were found to be viable and fertile. Consistent with these expectations, their retinas completely lacked α2δ4 protein when analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 2B). This was paralleled by loss of α2δ4 immunostaining at the ribbon synapses (Fig. 2C). We found the overall morphology of the α2δ4 KO retinas to be intact with no retinal degeneration at least until 2 months of age (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. Generation and characterization of knockout mice with complete elimination of α2δ4 protein.

A, Scheme of the targeting strategy and predicted consequences on disrupting the protein expression. Domain organization of α2δ4 is based on high-resolution structure of α2δ1 (Wu et al., 2016). B, Loss of α2δ4 protein expression as revealed by Western blot analysis of total retina lysates. C, Absence of α2δ4 immunostaining in the OPL layer of α2δ4 knockout retinas (scale bar, 25μm). D, Analysis of the retina morphology by toluidine blue staining of ultra-thin retina cross-sections (retinas used were from 6–10 week old mice). E, Western blot analysis of protein levels in α2δ4 KO retinas in comparison to WT littermates. F, Quantification of changes in protein levels by densitometry. Band intensities were normalized to WT. Error bars are SEM values, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, n=3–5 mice, t-test. G, Analysis of mouse vision in a visually guided behavioral task at photopic (100cd/m2) and scotopic conditions (0.001 cd/m2). Representative tracks of mice swimming to visible escape platform are shown. H, Quantification of mouse escape time in water maze task (panel G) at various luminance levels. Error bars are SEM, ***p<0.001, 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test, n=4–5 mice per genotype.

We first characterized the α2δ4 KO model by determining the expression of several molecules with key roles in photoreceptor and ON-BC signaling, and synaptic transmission. We found that the knockout of α2δ4 did not affect the expression of the key G proteins Gαt1 and Gαo, which mediate light-evoked responses in rods and ON-BCs, respectively (Fig. 2E,F). However, we detected substantial decreases in the expression of several ON-BC postsynaptic signaling proteins including mGluR6, TRPM1, and RGS complex components (Fig. 2E,F). Because these changes were reminiscent of observations in retinas lacking ELFN1, which trans-synaptically organizes the mGluR6 complex, we quantified changes in ELFN1 expression and found it to be also significantly diminished (Fig. 2E,F). In addition, α2δ4 ablation also reduced the expression of ribbon constituents: CaV1.4 and CTBP2 (Ribeye). These observations collectively suggest that α2δ4 has a critical role in the organization of the trans-synaptic complex.

To determine how these molecular alterations impact visual processing, we measured the performance of α2δ4 KO mice in a visually-guided water maze task under varying luminance using an object recognition paradigm (Cao et al., 2015). In this task, mice were trained to locate an escape platform based on visual cues (Fig. 2G,H). In addition to comparing α2δ4 KO mice to their wild-type littermates (WT), their performance was referenced to two other strains: Elfn1 KO mice with a selective loss of the primary rod pathway but a preserved secondary pathway where rod signals are transmitted to OFF- and ON-CBCs via rod-to-cone gap junctions (Cao et al., 2015), and Trpm1 KO mice in which synaptic transmission between the photoreceptors and all ON-BCs is ablated (Koike et al., 2010; Morgans et al., 2009). All animal groups were able to locate a hidden escape platform within similar times, indicating similar levels of locomotor activity and navigational strategies (Fig. 2H). When tested at photopic levels that activate cones for light detection, mice of all genotypes again performed similarly in finding the visible platform, indicating no learning and motor deficits and preservation of photopic vision (Fig. 2G,H). However, when the light intensity was decreased to scotopic levels near visual threshold (0.001 cd/m2), at which vision requires the primary rod pathway, α2δ4 KO mice could no longer detect an escape platform revealing their night blindness phenotype (Fig. 2G,H). Surprisingly, their performance at higher scotopic light intensities (0.01 cd/m2) that engage both the rod primary and secondary pathways for vision was indistinguishable from WT littermates, but clearly different from that of Trpm1 KO (Fig. 2G,H). The behavior of α2δ4 KO mice thus phenocopied the Elfn1 KO (Cao et al., 2015), suggesting the preservation of signaling through the secondary rod pathway.

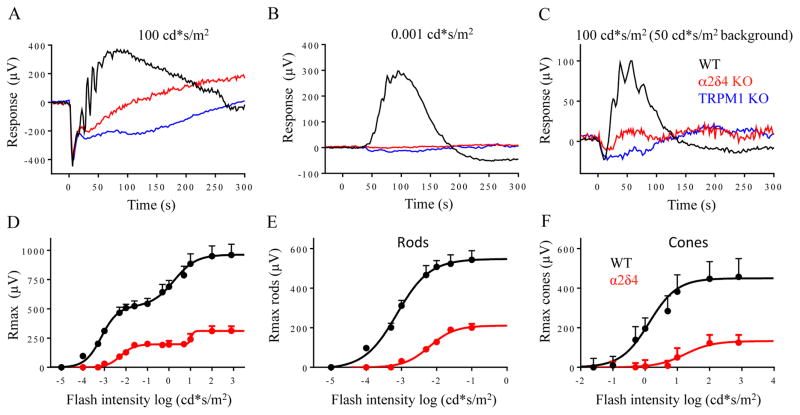

Elimination of α2δ4 abolishes rod, but not cone, synaptic transmission and reconfigures the retinal circuitry for the processing of photoreceptor inputs

To begin understanding the role of α2δ4 in the propagation of light-evoked responses across the retinal circuitry, we evaluated the α2δ4 KO mice by electroretinography (ERG). When activated by light, both rod and cone photoreceptors hyperpolarize and generate an electrically negative a-wave. As this signal is transmitted across the synapse, ON-RBCs and ON-CBCs depolarize to produce the positive b-wave. In dark-adapted retinas, bright flashes activating both rod and cone photoreceptors produced robust a-waves that were indistinguishable in amplitude and kinetics between the genotypes (Fig. 3A; Suppl. Fig. S2A), suggesting normal phototransduction in α2δ4 KO retinas. Indeed, patch clamp recordings directly from rods and cones in retinal slices confirmed this observation revealing robust photocurrents and normal light sensitivity in α2δ4 KO photoreceptors (Suppl. Fig. S2B, C).

Figure 3. Processing of light-evoked signals by the retina circuitry in α2δ4 knockout retinas as revealed by ERG recordings.

A, Representative trace of dark-adapted ERG response to a bright flash activating both rods and cones. B, Representative ERG traces elicited by a scotopic flash of 0.001 cd*s/m2 to activate the primary rod pathway only. C, Representative ERG traces to a photopic flash of 100 cd*s/m2 under a 50 cd*s/m2 light background to activate cone pathway only. D, Dose response plot of maximal b-wave amplitudes from WT and α2δ4 KO mice plotted against their eliciting flash-intensities. E, Rod-only ON-BC dose-response component. F, Cone-only ON-BC dose-response component. The data are averaged from 3 mice of each genotype.

In contrast, the scotopic b-wave in α2δ4 KO was undetectable (Fig. 3B). This response was identical to TRPM1 KO mice, in which synaptic transmission to ON-BCs is abolished completely, indicating a lack of ON-RBC depolarization in α2δ4 KO mice (Fig. 3B). When background light was applied to suppress the activity of rods in α2δ4 KO mice, bright photopic flashes elicited responses with reduced but clearly detectable b-waves, suggesting that deletion of α2δ4 did not abolish signals generated by synaptic transmission from cones (Fig. 3C).

To obtain further insight into the propagation of photoreceptor driven signals to ON-bipolar neurons we analyzed the dose-response effect of light on b-wave amplitudes (Fig. 3D; Suppl. Table 1). Analysis of the rod-driven component of the biphasic amplitude vs light intensity relationship revealed the presence of partial b-wave responses, consistent with transduction of rod-driven signals via the less sensitive secondary rod pathway (Fig. 3E). In fact, the parameters of this response were nearly identical to those reported previously in ELFN1 KO retinas (Suppl. Table 1; (Cao et al., 2015)), which completely lack synaptic transmission to ON-RBCs, reinforcing the idea that residual response is likely mediated by ON-CBCs. We also observed a substantial reduction in the cone driven component of the b-wave (Fig. 3F; Suppl. Table 1).

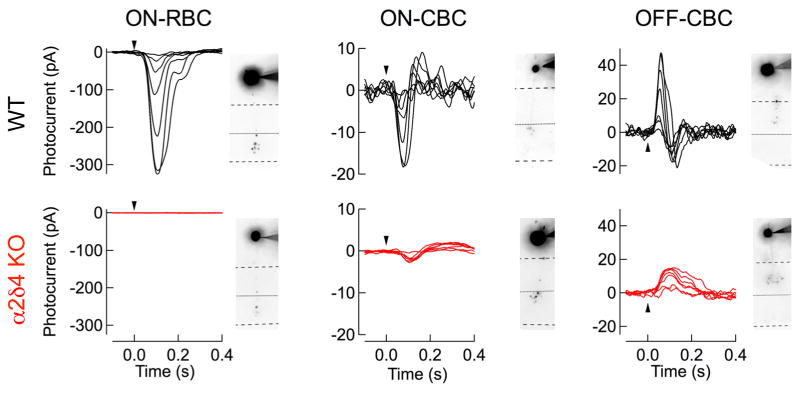

To understand the mechanistic basis for rod-mediated signal flow in the outer retinas of mice lacking α2δ4, we made patch clamp recordings from different populations of bipolar neurons in dark-adapted retinal slices. We found that light-evoked responses from ON-RBCs (Fig. 4) were totally absent in α2δ4 KO retinas, confirming the loss of synaptic transmission from rods-to-ON RBCs in the α2δ4 KO mice. However, both ON-CBCs and OFF-CBCs displayed responses at scotopic flash strengths (Fig. 4), reflecting the preservation of the rod secondary pathway. While these responses were clearly discernible and originate with rod photoreceptors, they were smaller in maximum amplitude compared to their WT counterparts (Fig. 4; Suppl. Table 2; across all CBCs). This reduction in amplitude was not accompanied by a shift in half-maximal flash strength (Suppl. Table 2). These smaller responses were consistent with the observed reduction but not elimination of the photopic ERG b-waves and suggest preservation of synaptic transmission between cones and CBCs, albeit at a reduced efficiency.

Figure 4. Synaptic transmission of rod and cone signals to individual types of bipolar neurons assessed by single cell patch clam recordings.

Light-evoked responses of ON-RBCs, ON-CBCs, and OFF-CBCs in dark-adapted slices from WT and α2δ4 KO mice. Flash strengths range from 0.37 to 24 R*/rod for RBCs and CBCs, covering both primary and secondary rod pathways. Cells were filled during recordings with the Alexa-750 and imaged to confirm the bipolar cell identity, and shown for each cell. Averaged response characteristics and number of cells recorded from for ON-RBCs, ON-CBCs, and OFF-CBCs are provided in Supplemental Table 2.

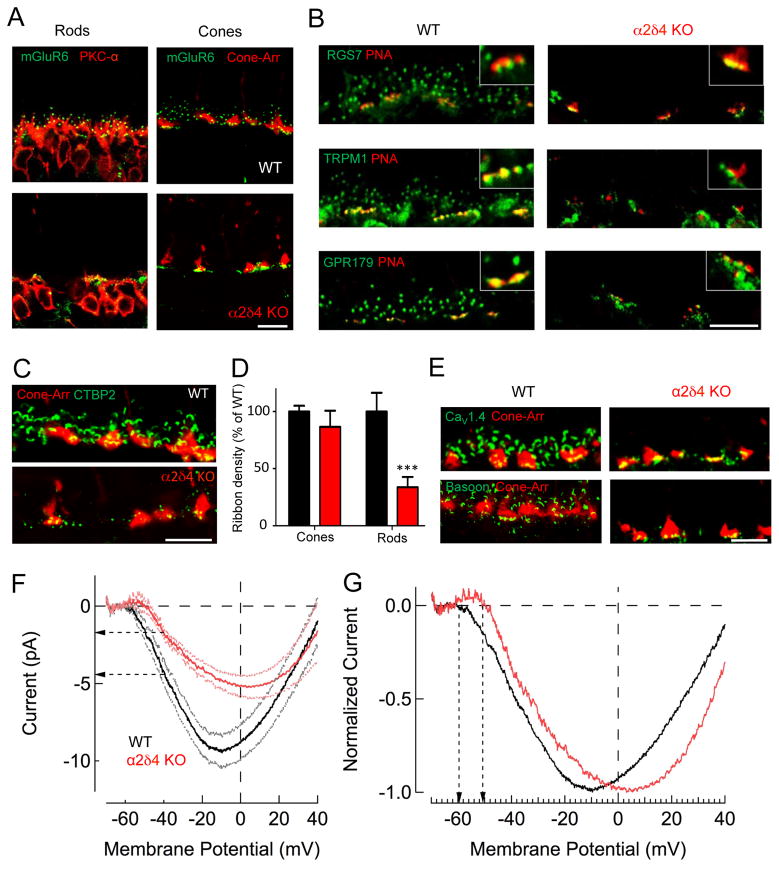

Loss of α2δ4 results in selective disorganization of rod synaptic ribbons and abolishes targeting of postsynaptic proteins to ON-RBC dendritic tips

To explore the mechanisms underlying the selective loss of synaptic transmission to ON-RBCs in the α2δ4 KO mouse, we examined the architecture of rod and cone synapses. First, we characterized changes in targeting and postsynaptic accumulation of ON-BC cascade elements maintaining a distinction between rod and cone synapses (Fig. 5A,B). Strikingly, we found mGluR6 to be completely absent from the dendritic tips of ON–RBCs but present in ON-CBCs (Fig. 5A). Consistent with this observation, other cascade elements that play an essential role in generating depolarizing responses in ON-bipolar neurons (RGS, TRPM1, and GPR179) were also absent from the dendritic tips of ON-RBCs, but present at the tips of ON-CBCs (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Deficits in structural and functional architecture of rod photoreceptor ribbon synapses associated with α2δ4 loss.

A, Loss of mGluR6 postsynaptic targeting to the dendritic tips in ON-RBCs, but not for ON-CBCs in α2δ4 knockout retinas. B, Effect of α2δ4 deletion on postsynaptic targeting of signaling molecules in ON-CBC and ON-RBC. Active zones of cone terminals labeled by PNA. C, Immunohistochemical analysis of photoreceptor ribbons. D, Quantification of ribbon densities in rods and cones. Area occupied by CTBP2 inside (cone) and outside (rod) of cone-arrestin mask was determined and normalized to WT. The total number of cone terminals selected was 100 for WT and 86 for α2δ4 KO from 3 mice for each genotype. The total number of areas outside of cone terminal selected was 82 for WT and 69 for α2δ4 KO from 3 mice for each genotype. Error bars are SEM values, ***p<0.001, two-way ANOVA. E, Changes in the active zone components associated with synaptic terminals of photoreceptors. All scale bars in A–E are 10μm. F, Representative CaV1.4 mediated currents measured from individual rods in retinal slices. Ca2+ currents were measured under voltage-clamp by ramping the membrane potential from −80mV to +40mV in 1 sec. Data are shown along with the SEM values. Horizontal arrows indicate difference in Ca2+ current at the rod’s normal resting potential of Vm = −40mV. G, Ca2+ currents normalized to the peak current density reveal a shift in the voltage sensitivity of the current. Vertical arrows reveal ~8mV shift in the membrane potential at which Ca2+ channels begin to open.

Given that α2δ4 is associated with synaptic ribbons, we analyzed the effect of its ablation on the ribbon structure. We found marked deficits in ribbon organization that disproportionately affected rods (Fig. 5C). Quantification showed a 66±12% reduction in the density of ribbons in rods with no significant change in ribbon numbers in cone terminals (Fig. 5D). The remaining rod ribbons were smaller in size and more rounded in shape, hallmarks of immature ribbon structures (Fig. 5C; Suppl. Fig. S3A,B). These changes were paralleled by a significant reduction in the CaV1.4 content associated with ribbons in both rods and cones (Fig. 5E; Suppl. Fig. S3C,D).

Because α2δ4 interacts directly with CaV1.4 channels, we further tested the impact of α2δ4 deletion on CaV1.4 function by patch clamp recordings from photoreceptors (Fig. 5F). We estimated the Ca2+ current density in WT and α2δ4 KO rods during whole cell recordings using an internal solution that allowed the isolation of the synaptic Ca2+ current (Majumder et al., 2013). Voltage clamp recordings held the rod’s membrane potential near its normal resting value (Vm = −40 mV), and we ramped the membrane potential between −80 mV and +40 mV over a period of 1s. The current was plotted against the membrane potential (Fig. 5F). Recordings revealed that the maximum Ca2+ current density is reduced substantially in α2δ4 KO rods compared to WT rods. At the dark, resting potential of rod photoreceptors (~−40mV), this reduction corresponds to a ~60% decrease in synaptic Ca2+ influx (Fig. 5F). The reduced Ca2+ current is consistent with the reduced CaV1.4 expression in α2δ4 KO retinas (Fig. 2). In addition, the voltage sensitivity of the Ca2+ current was shifted by ~8 mV towards more depolarized membrane potentials (Fig. 5G). We also observed substantial reduction in CaV1.4 function in cones to an extent that residual currents were not reliable enough to allow measuring changes in the voltage-dependence (Suppl. Fig. S3E). Together, these results indicate a critical role for α2δ4 in organizing synaptic signaling complexes in rod and cone photoreceptors and setting their functional characteristics.

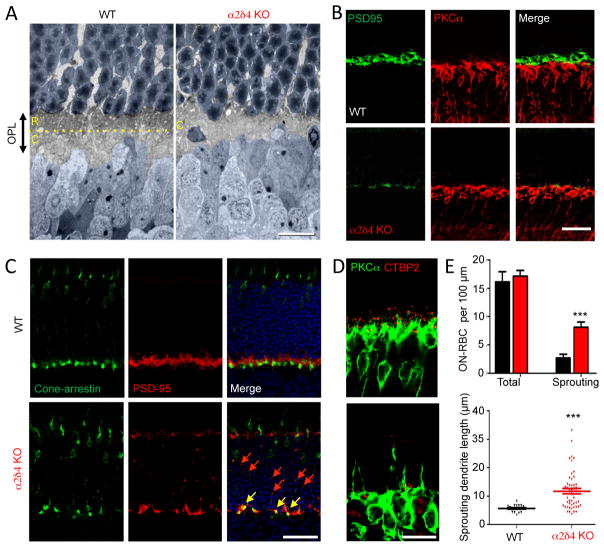

Rods fail to elaborate axonal terminals and form physical contacts with rod ON-BCs in the absence of α2δ4

Given the substantial changes in the synaptic organization of α2δ4 KO retinas, we sought to determine how photoreceptor wiring was affected. We assessed the organization of the synaptic layer by electron microscopy at low magnification (Fig. 6A). In WT retinas, the OPL is divided into two sublaminas, the outer region with more electron density is populated mainly by rod spherules while the inner aspect contains larger cone pedicles. In α2δ4 knockout retinas we found that the OPL was substantially thinner (Fig. 6A; Suppl. Fig. S4). Strikingly, this reduction in thickness appeared to be caused entirely by the elimination of the outer sublamina (Fig. 6A), suggesting disorganization of the rod terminals. To investigate further, we stained retinal cross-sections for PSD95, which decorates the axonal terminals of rods and cones. We observed a large decrease in the number of the terminals in direct apposition to PKCα-positive ON-RBC dendrites (Fig. 6B). The OPL of α2δ4 KO retinas contained only few terminals, which by shape and position resembled cone pedicles. This observation was confirmed by labeling cones directly, which revealed that the majority of PSD95-positive staining in the OPL was in fact associated with cone pedicles (Fig. 6C). Interestingly, we also observed a substantial number of smaller PSD95-positive puncta spread all over the photoreceptor nuclear layer, indicating that many rod axons fail to reach their target lamina or they retract post-developmentally (Fig. 6C). In agreement with premature rod axon termination, we observed remodeling of ON-RBC dendrites, which exhibited substantial sprouting and sent projections into the outer nuclear layer to match mislocalized presynaptic specializations (Fig. 6D,E), a phenomenon observed in several mouse models with ectopic synapses (Haeseleer et al., 2004; Mansergh et al., 2005).

Figure 6. α2δ4 ablation causes deficits in elaboration of rod axonal terminals.

A, Ultrastructural analysis of the outer plexiform layer (OPL) organization. Rod photoreceptor axons terminate in the outer aspect of the OPL (R), whereas cones form pedicles in the inner sublamina (C), separated by the yellow dotted line. Nuclei of photoreceptors and ON-BC are painted in blue. B, Loss of rod synaptic terminals identified by PSD95 staining in the OPL region of α2δ4 knockout retinas. C, Preservation of cone axonal terminals in the OPL region of α2δ4 knockout retinas and axonal retraction of rod terminals to the outer nuclear layer (ONL). Cone pedicles were identified by overlap between cone arrestin and PSD95 staining (yellow arrows). Remaining rod terminals are seen as small PSD95 positive (cone arrestin negative) puncta scattered in the OPL and ONL (red arrows). D, Sprouting ON-RBC dendrites in α2δ4 KO retinas. E, Quantification of dendritic overextension (sprouting) of ON-RBCs in α2δ4 KO comparison relative to WT. Six to eight regions of retina with different eccentricities from 3 independent mice for each genotype were used. Error bars are SEM values, ***p<0.001, t-test. All scale bars in A–E are 25 μm.

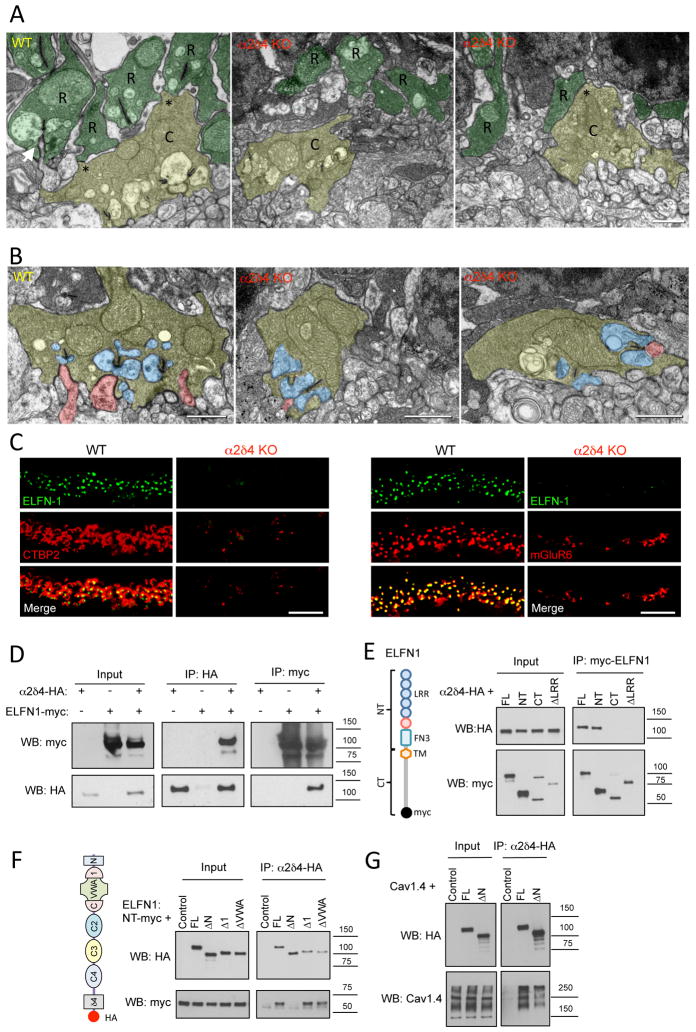

We examined rod synaptic architecture at the ultrastructural level by electron microscopy. In contrast to the orderly organization of the WT rod synapses with clearly identifiable ribbons and invaginating ON-RBC dendrites, we failed to detect any normally elaborated rod spherules and ribbons in the α2δ4 KO (Fig. 7A). Instead, we observed thin projections that occasionally contained mitochondria, which appeared to be rod axons. However, these axonal projections did not display electron densities that resembled ribbons and contained no invaginating ON-RBC dendrites or horizontal cell processes. In contrast, cone pedicles in α2δ4 KOs were easily identifiable in the OPL and contained normally sized ribbons. Upon closer examination, these cone pedicles appeared to have less regular, somewhat shrunken shape relative to their WT counterparts (Fig. 7B). The reduction in cone pedicle size, with no changes in the cone density, was confirmed quantitatively by light microscopy (Suppl. Fig. S5A,B). Despite these changes, we were able to identify ON-CBC processes as well as horizontal cells making contacts with the cone pedicles in α2δ4 KO retinas (Fig. 7B). Thus, α2δ4 elimination selectively abolished rod synaptogenesis while slightly influencing the morphology of cone pedicles without preventing their ability to form synapses.

Figure 7. Inactivation of α2δ4 specifically disrupts rod synaptogenesis.

A, Ultrastructural analysis of rod and cone terminals in the OPL of WT and α2δ4 KO retinas. Rod axons and terminals (R) are marked in dark green. Cone pedicles (C) are marked in yellow. Gap junction-like contacts between rod and cone terminals are identified by asterisks. Arrow indicates ON-RBC dendrite invaginating into rod spherule. Scale bar, 500 nm. B, Morphology of cone photoreceptor terminals revealed by electron microscopy. Retinas from two different mice for each genotype were used. Cone terminals (pedicles) are colored in yellow, processes of horizontal cells in blue and ON-BC dendrites in pink. Scale bar, 500nm. C, Complete loss of cell adhesion protein ELFN1 in rod synapses of α2δ4 KO. Scale bar, 10μm. Retinas from three different mice for each genotype were used. D, α2δ4 and ELFN1 co-immunoprecipitate upon co-expression in HEK293 cells. Three independent experiments were performed. E, Site-directed mutagenesis to delineate determinants in ELFN1 responsible for binding to α2δ4. Various structural features present in ELFN1 (diagram) were deleted, and truncated constructs were probed for binding to α2δ4 upon co-expression in HEK293 cells. Three independent experiments were performed. F, Site-directed mutagenesis to delineate determinants in α2δ4 responsible for binding to ELFN1. Various structural features present in α2δ4 (diagram) were deleted and the truncated constructs were probed for binding to ELFN1 upon co-expression in HEK293 cells. Three independent experiments were performed. G, Disrupting N-terminal region of α2δ4 does not prevent its interaction with CaV1.4 as evidenced by co-immunoprecipitation assay performed as in panel F, except that ELFN1 was substituted with CaV1.4. Three independent experiments were performed.

α2δ4 affects rod synaptogenesis via interaction with ELFN1 dependent on CaV1.4 expression

Because we observed deficits in synapse formation that were selective for rods, concomitant with a loss in post-synaptic targeting of mGluR6 to ON-RBC dendrites, we tested the hypothesis that defects in synaptogenesis observed in α2δ4 knockouts may be caused by the loss of ELFN1. Indeed, while ELFN1 was concentrated at the ribbons of WT retinas in direct apposition with mGluR6, it was completely absent at the synapses of α2δ4 KO retinas (Fig. 7C). This suggests that the inability to recruit ELFN1 to ribbons may underlie synapse formation deficits in the absence of α2δ4.

Interestingly, we have noted that in addition to ELFN1, we detected several α2δ4 peptides by mass-spectrometry (Cao et al., 2015) following affinity purification of mGluR6 complexes from mouse retinas, suggesting that α2δ4 and ELFN1 are present in the same macromolecular complex. In support of this model, we found that α2δ4 co-immunoprecipitates with ELFN1 when reconstituted in transfected HEK293 cells, suggesting their physical association (Fig. 7D). Using deletion mutagenesis, we mapped binding determinants of the ELFN1-α2δ4 interaction. First, we determined that the binding to α2δ4 is mediated by the distal part of the ELFN1 ectodomain, containing the leucine-rich repeats (Fig. 7E). Conversely, the binding to ELFN1 required the presence of the N-terminal sequence in α2δ4 (aa 26–147) that structurally completes several Cache domains (Wu et al., 2016). In contrast, the VWA domain was found to be dispensable for the interaction (Fig. 7F). Interestingly, deleting the same N-terminal helices of α2δ4 did not prevent its association with CaV1.4 (Fig. 7G), indicating that the binding determinants for ELFN1 and CaV1.4 on α2δ4 are distinct. We further probed the ELFN1-α2δ4 interaction in the pull-down assays using purified recombinant extracellular domain of ELFN1 and failed to observe appreciable binding (Suppl. Fig. S5C), suggesting that the complexes may need to be co-assembled during biosynthesis or that the interaction may require additional, yet to be identified cellular components.

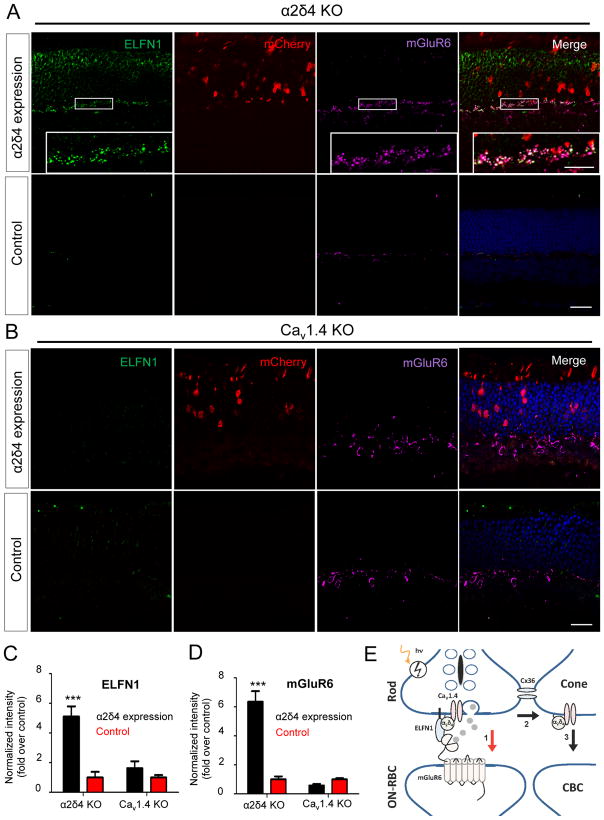

To probe for the role of α2δ4 association with CaV1.4 in rod synaptogenesis we performed rescue experiments expressing full-length α2δ4 in rod photoreceptors following in vivo electroporation into retinas of neonatal mice (Fig. 8). First, we delivered the α2δ4 construct into retinas of α2δ4 KO mice. Unlike endogenous α2δ4, ectopically expressed α2δ4 was distributed across the entire photoreceptor, possibly due to its overexpression when driven by a strong rhodopsin promoter (Suppl. Fig. S6A). Nevertheless, we were readily able to detect α2δ4 accumulation at the axonal terminals (Suppl. Fig. S6A). Importantly, ectopic expression of α2δ4 led to the re-appearance of punctate ELFN1 and mGluR6 immunoreactivity specifically at axonal terminals of transfected cells (Fig. 8A,C,D), indicating that re-expression of α2δ4 rescued synaptic targeting of ELFN1 as well as synapse formation through trans-synaptic recruitment of mGluR6. We next performed the same ectopic expression of α2δ4 in rods of CaV1.4 KO mice, where again we observed its substantial accumulation at the axonal terminals (Suppl. Fig. S6A). However, in contrast to experiments with the α2δ4 KO, expression of α2δ4 in CaV1.4 KO rods did not result in any detectable restoration of ELFN1 or mGluR6 synaptic targeting (Fig. 8B,C,D), indicating that synaptogenic effects of α2δ4 in rods require the CaV1.4 channel and that both proteins are required for the synaptic accumulation of ELFN1. We also performed rescue experiments with an α2δ4 deletional mutant (α2δ4-ΔN) that only abolished interaction with ELFN1 but not with CaV1.4, however this construct was undetectable when expressed in rods of α2δ4 KO mice, suggesting that the role of the α2δ4 N-terminus is to maintain α2δ4 stability in vivo (Suppl. Fig. S6A). In summary, these data indicate that selective effects of α2δ4 on rod synapse formation involve its coordination with both the neurotransmitter release machinery and synaptic molecules that establish trans-synaptic contacts with ON-RBCs.

Figure 8. Overexpression of α2δ4 in rods lacking CaV1.4 does not rescue synapse formation deficits.

A, Validation of genetic rescue approach by electroporation of construct containing α2δ4 gene under the control of mouse rhodopsin promoter into neonatal mice. α2δ4 construct was co-injected with mCherry-containing plasmid to identify transfected rods. Areas within white frames, enlarged in the insert, show recovery of mGluR6 and ELFN1 punctate fluorescence co-localizing in the OPL, which indicates restoration of synapse formation. Scale bar, 10 μm. Control are from regions with no detectable mCherry signal in the same injected retinas. Retinas were analyzed at 4–6 weeks of age. Scale bar, 20μm. B, In vivo electroporation of α2δ4 construct into CaV1.4 KO retinas. The experiment was performed exactly as in panel A, except that CaV1.4 KO were used instead of α2δ4 KO. Scale bar, 20μm. C and D, Quantification of synaptic clustering of ELFN1 and mGluR6 in OPL regions of rescue experiments, respectively. Five different regions of retina from three different mice of each genotype were used, mean values with SEM were plotted, ***, P<0.001, two-way ANOVA. E, Model for the action of α2δ4 at photoreceptor synapses. α2δ4 forms complexes with both CaV1.4 and ELFN1, and this property is essential for the ability of rods to establish trans-synaptic contacts with ON-RBCs to transmit rod signals via the primary pathway (1). In the absence of α2δ4, rods transmit signals via gap junctions to cone terminals (2), and then to ON-CBCs via the secondary pathway (3).

Discussion

Role of α2δ4 in selective rod photoreceptor synaptogenesis: model and mechanisms

The molecular mechanisms underlying the development of a presynaptic neurotransmitter release apparatus in coordination with functional postsynaptic contacts requires the relevant synaptic machinery to be in physical alignment. While the mechanistic basis for the formation of ionotropic synapses has been studied extensively, much less is known about the molecular mechanisms underlying the development of metabotropic synapses. Here we demonstrate that the extracellular protein α2δ4 plays an essential role in establishing physical contacts within the rod presynaptic terminals, which are critical for aligning presynaptic glutamate release machinery with postsynaptic mGluR6 receptors.

Our findings in rod photoreceptors reveal that α2δ4 is required for the expression and synaptic targeting of the critical synaptogenic molecule, ELFN1, which in turn forms trans-synaptic complexes with the postsynaptic glutamate receptor on ON-RBCs, mGluR6. We further find that ELFN1, by a virtue of its leucine-rich repeat domain, forms physical complexes with α2δ4, via the N-terminal region of α2δ4. Since the trans-synaptic ELFN1-mGluR6 interaction is essential for the formation of rod synapses (Cao et al., 2015), these observations indicate a model where α2δ4 enables rod photoreceptor synaptogenesis by recruiting ELFN1 to CaV1.4-containing synaptic ribbons. ELFN1 can then engage directly with the postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptor, mGluR6 (Fig. 8E), which is responsible for clustering a majority of the postsynaptic elements. Thus, we propose that α2δ4 plays a central role in the proper alignment of the presynaptic release with postsynaptic metabotropic receptors. These observations may suggest a general mechanism by which α2δ proteins exert synaptogenenic effects. For instance, loss of α2δ3 function has been shown to result in deficits in synapse formation and a decrease of synaptic transmission (Hoppa et al., 2012; Pirone et al., 2014), whereas overexpression of α2δ1 was reported to increase assembly of functional synapses working in concert with extracellular matrix protein thrombospondin 1 (Eroglu et al., 2009) and α2δ3 in hair cells was shown to control trans-synaptically AMPA receptor recruitment (Fell et al., 2016). Despite these advances, the molecular mechanisms that mediate the effects of α2δ proteins on synapse formation were not elucidated.

In contrast to previously reported effects, the phenotype that we observed with α2δ4 KO in photoreceptors was strikingly dramatic – i.e. a complete ablation of synapse formation and synaptic transmission. The severity of the effect facilitated a dissection of the molecular mechanisms of α2δ4 function in synapses and determining that it involves association with the key synaptogenic molecule in rods, ELFN1. It is tempting to speculate that this mechanism could be extended to explain the action of other α2δ proteins through the interaction with the ELFN1-like family of leucine-rich repeat containing proteins (de Wit et al., 2011). Such interactions may be key for integrating a presynaptic release apparatus with relevant postsynaptic receptors in a cell-type selective manner. Our rescue experiments also argue that the synaptogenic role of α2δ4 in forming metabotropic synapses in photoreceptors require the CaV1.4 complex, in contrast to the CaV-independent effects described for ionotropic synapses in central nervous system (Eroglu et al., 2009; Kurshan et al., 2009). Thus it appears that α2δ4 at photoreceptor synapses is integrated into a larger macromolecular complex where multiple components contribute to establishing the appropriate wiring. The possibility of additional factors required for the formation of these synapses seems likely based on: (i) the requirement for ELFN1 and α2δ4 to be co-expressed to be assembled into the complex and (ii) the observation that blocking neurotransmitter release differentially affects synaptic targeting of CaV1.4 (none), α2δ4 (partial), and ELFN1 (complete). These observations suggest that such additional synaptogenic factors should be integrated with both the glutamate release machinery and the ELFN1-α2δ4 complex; their identification will be an intriguing goal for future studies.

Although α2δ4 is expressed by both rod and cone photoreceptors and found associated with the synaptic ribbons in both cell types, it appears to have little effect on synapse formation at the cone pedicle. Cone pedicles maintain a relatively normal physical structure and are capable of synaptic transmission to ON-CBCs, albeit with substantially reduced efficiency due to dysregulation of the CaV1.4 channel. It is possible that the function of α2δ4 in cones is redundant with another, cone-specific α2δ member, which compensates partially for its loss. Indeed, the presence of other α2δ isoforms in the photoreceptor synaptic layer has been documented (Farrell et al., 2014; Perez de Sevilla Muller et al., 2015). Alternatively, cones may use different molecular mechanisms for synaptogenesis. Although their wiring with ON-CBCs is also dependent on the presence of mGluR6, cones do not express ELFN1 (Cao et al., 2015). Furthermore, cones can establish synaptic contacts with OFF-bipolar cells, which do not normally contact rods, suggesting that the molecular mechanisms underlying synaptogenesis in cones may deviate substantially from those in rods. Identification of the cone specific synaptogenic molecules that mediate cones wiring into the circuit remains an important future direction.

Critical role of α2δ4 in modulating Ca2+ channel trafficking, their biophysical properties, and active zone organization in vivo

In photoreceptors α2δ4 is targeted to the macromolecular complex containing the glutamate release apparatus at synaptic ribbons located in their axonal terminals (Lee et al., 2015). One of the critical components of synaptic ribbons is CaV1.4 calcium channels, which trigger vesicular fusion and play a central role in organizing synaptic ribbons (Mercer and Thoreson, 2011). We show that CaV1.4 sets the abundance of α2δ4 at the terminals. Conversely, we found α2δ4 to be essential for increasing the number of functional CaV1.4 channels at ribbons. The role of α2δ4 in setting the number of functional CaV1.4 in the presynaptic active zones of photoreceptors is consistent with the described roles of α2δ1-3 in trafficking other members of CaV family in neurons (Cassidy et al., 2014; D’Arco et al., 2015; Fell et al., 2016; Hoppa et al., 2012) and their reported chaperone-like function in promoting surface localization of CaV channels in reconstituted systems (Dolphin, 2013).

Strikingly, our studies also reveal that α2δ4 appears to tune the voltage sensitivity of the CaV1.4 Ca2+ current. In the physiological range of the rod’s membrane potential, shifts in the voltage sensitivity of Ca2+ channels induced by α2δ4 are likely to play a crucial role in setting the dark release rate of glutamate in the physiological range. For instance the observed shift in the voltage sensitivity of the Ca2+ channel is similar to that observed in the Ca2+ Binding Protein 4 (CABP4) knockout mouse (Haeseleer et al., 2004), suggesting that multiple protein interactions, both intracellular and extracellular, are required to fine tune this relationship. The glutamate release under normal conditions is sufficient to saturate the mGluR6 cascade (Sampath and Rieke, 2004), a prerequisite for the robust separation of the rod’s single-photon response from the continuous noise (Field and Rieke, 2002). Thus, the shift of the voltage sensitivity in α2δ4 KO rods indicates that setting the dark glutamate release rate is also controlled by the interactions of the CaV1.4 channel with the extracellular synaptic proteins.

The role of α2δ4 in organizing ribbon-type active zones may be also related to regulation of CaV1.4 abundance, because elimination of CaV1.4 or α2δ4 results in nearly identical effects on the organization of rod synaptic ribbons (Liu et al., 2013; Mansergh et al., 2005; Specht et al., 2009). However, the morphogenic role of α2δ4 in the elaboration of synaptic terminals of photoreceptors may be distinct from its effects on the CaV1.4, at least in cones, as the shrinkage of cone pedicles we observed in α2δ4 KO occurs with no significant effects on the cone ribbon architecture. These results are consistent with the described morphogenic effects of α2δ3 on the formation of synaptic boutons in the fly neuromuscular junction (Kurshan et al., 2009), and axonal terminals of ANF neurons in the auditory circuit (Pirone et al., 2014), both of which also appear to be independent of CaV channels.

Implications for understanding functional retina wiring and retinal dystrophy mechanisms

Mutations in α2δ4 were established as a cause of night blindness and generalized cone dysfunction in humans (Ba-Abbad et al., 2016; Wycisk et al., 2006b). Subsequently, a spontaneous mutation (c.C2451insC) was identified in mice that gave rise to a frameshift that diminishes α2δ4 mRNA levels by half and potentially disrupts the distal part of the α2δ4 protein (Caputo et al., 2015; Ruether et al., 2000; Wycisk et al., 2006a). When analyzed by ERG, this mouse model exhibited deficits reminiscent of observations in patients with mutations in α2δ4. At a morphological level, unspecified synaptic deficits in the organization of OPL were noted. However, the progress in understanding α2δ4 function in photoreceptors has been limited by an unknown effect of mutations on its expression/function, and a general lack of mechanistic insight regarding their function. The complete deletion of α2δ4 in our murine model, as well as the cell and synaptic level of dissection presented here, offers insights into the role of α2δ4 into the organization of the retinal circuitry revealing how its disruption leads to disease.

One of the key observations of this study is that while α2δ4 is not necessary for the synaptic wiring of the cone pedicle, it plays an important role in controlling synaptic transmission to both ON-CBCs and OFF-CBCs through the effects on setting abundance and function of CaV1.4 channels. Thus our mouse model provides evidence for the origin of the cone deficits observed in patients with mutations in α2δ4. Interestingly, despite a substantial reduction in the CaV1.4 function in cones, these neurons are capable of propagating signals to the downstream postsynaptic partners. Since rods couple to cones by electrical synapses, the rod signals in α2δ4 KO retina are also not lost but are rather transmitted to cones and then to ON-CBCs and OFF-CBCs via the less sensitive rod secondary pathway. These rod contributions in turn are somewhat diminished given smaller response of CBCs. Thus, α2δ4 plays an essential role in circuit organization, directing the propagation of light-evoked signals through the retina (Fig. 8E). This circuit-level deficiency may be the underlying mechanism behind visual deficits in patients with mutations in the gene encoding the α2δ4 protein.

STAR METHODS

Contact for Reagent and Resource Sharing

Further information and requests for reagents may be directed to, and will be fulfilled by, the corresponding author Kirill Martemyanov (kirill@scripps.edu)

Experimental Models and Subject Details

Procedures involving mice strictly followed NIH guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Scripps Florida and the University of California, Los Angeles. Mice were maintained in a pathogen free facility under standard housing conditions with continuous access to food and water. Mice used in the study were 1–4 months old, and were maintained on a diurnal 12 h light/dark cycle. In vivo electroporation was performed on neonatal mice (P0–P3). Male and female mice were used interchangeably across experiments. No mice displayed health or immune status abnormalities, and were not subject to prior procedures. The genotype of mice are described where appropriate.

α2δ4 knockout mice (obtained from Deltagen, Inc) were generated by homologous recombination replacing the entire exon 8 of Cacna2d4 gene with LacZ/Neo cassette disrupting exon splicing site and introducing early stop codon. Mice were bred as heterozygous pairs to obtain α2δ4−/− knockout mice and their α2δ4+/+ wild-type littermates. The generation of mGluR6nob3 (Maddox et al., 2008), RGS7/11 double KO (Cao et al., 2012), GPR179nob5 (Peachey et al., 2012), CAST KO (tom Dieck et al., 2012), ELFN1 KO (Cao et al., 2015), TRPM1 (Trpm1tm1Lex; (Shen et al., 2009), Cav1.4 KO (Specht et al., 2009) and TeNT mice (Cao et al., 2015) were described previously.

Methods Details

Antibodies and DNA constructs

Generation of sheep anti-RGS11, rabbit anti-RGS11, sheep anti-TRPM1, and sheep anti-mGluR6 antibodies were described previously (Cao et al., 2009; Cao et al., 2011). Rabbit anti-ELFN1 (NTR) and rabbit anti-ELFN1 (CTR) antibodies were generated against synthetic peptides of mouse ELFN1 (aa 305–320 and aa 530–547, respectively). Rat anti-α2δ4 antibody (Lee et al., 2015) was generous gift from Dr. Francoise Haeseleer (University of Washington, WA). Rabbit anti-Cav1.4 (Liu et al., 2013) was generous gift from Dr. Amy Lee (University of Iowa, IA). Sheep anti-RGS9-2 antibodies were used to detect GPR179 in the retinas as described (Orlandi et al., 2013). Commercial antibodies used included: mouse anti-GAPDH (AB2302, Millipore), rabbit anti-c-myc (A00172, Genscript), mouse anti-CtBP2 (612044, BD Biosciences), mouse anti-PKCα (ab11723; Abcam), mouse anti-GPR179 (Primm Biotech; Ab887), rabbit anti-Gαo (K-20, Santa Cruz), goat anti-Arrestin-C (I-17, Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-cone arrestin (AB15282, Millipore), rabbit anti-Gαt1 (K-20, Santa Cruz), Peanut Agglutinin (PNA) Alexa Fluor 647 conjugate (Life Technologies), rabbit anti-PSD95 (D27E11, Cat# 3450S, Cell Signaling Technology), and chicken anti-RFP (Rockland).

The C-terminal c-myc tagged mouse full length ELFN1, NT-ELFN1 (aa 1-418), and TM/CT-ELFN1 (aa 419-828) were described previously (Cao et al., 2015). The mCherry construct under the control of 4.2 kb mouse opsin promoter was a gift from Dr. Vadim Arshavsky (Pearring et al., 2014). To create the c-myc tagged ΔLRR-ELFN1, the LRR domain (aa 28-242) was deleted by PCR using the forward primer (5′-GGGCTGGCCCAAGGTATCCTTAGCAAGCTTCAGTC-3′) and the reverse primer (5′-ACCTTGGGCCAGCCCACCCG-3′) followed by homologous recombination with the In-Fusion® HD Cloning kit. To create the HA-tagged α2δ4 construct, the full length human α2δ4 was amplified from the human α2δ4 cDNA clone (Clone ID: 100067179, Open Biosystems) with the HA sequence simultaneously added to the C-terminus using the forward primer (5′-ATG GTC TGT GGC TGC TCT GC-3′) and the reverse primer (5′-TCA AGC GTA GTC TGG GAC GTC GTA TGG GTA CCG CAG GAG TTG GGG CAG TA-3′) followed by subcloning the PCR product into pcDNA3.1 using TA Cloning® kits (ThermoFisher Scientific). The α2δ4 mutant lacking the N-terminal helices (AA26-147, α2δ4 ΔN) was amplified from the WT α2δ4 construct using the forward primer (5′-ACT CCC AAC TTC CTC GCC GAG GAG GCC GAC-3′) and the reverse primer (5′-GAG GAA GTT GGG AGT TGC AG-3′). The α2δ4 mutant lacking the Cache1 domain (AA148-264, α2δ4 Δ1) was amplified from the WT α2δ4 construct using the forward primer (5′-AAT CTG GTG GAA GCT ACA CCT GAT GAG AAT GGA GT-3′) and the reverse primer (5′-AGC TTC CAC CAG ATT CTG GA-3′). The α2δ4 mutant lacking the VWA domain (AA277-280, α2δ4 ΔVWA) was amplified from the WT α2δ4 construct using the forward primer (5′-ATT ACT TTT GAC TGC CAC GAC CAC GAC ATC ATC TG-3′) and the reverse primer (5′-GCA GTC AAA AGT AAT GAC TCC ATT C-3′). The amplified PCR products were then used for homologous recombination using In-Fusion® HD Cloning kits to generate the final α2δ4 mutant constructs. For constructs with the rhodopsin promoter, WT α2δ4 and α2δ4 ΔN were first amplified from the corresponding pcDNA3.1 constructs using the forward primers (5′-CCC CTC GAG GTC GAC ATG CCC AGG AGT TCC TGT GGC-3′) for WT and (5′-CCC CTC GAG GTC GAC ACA CCT GAT GAG AAT GGA GT-3′) for ΔN; and the reverse primers (5′-TAG AAC TAG TGG ATC CTC ACC ACA GAA GCT GGG GTG GA-3′) for WT and (5′-TAG AAC TAG TGG ATC CAG CTT CCA CCA GAT TCT GGA-3′) for ΔN. The amplified PCR products were then used for homologous recombination using In-Fusion® HD Cloning kits to generate the final rhodopsin promoter α2δ4 constructs (Rho-α2δ4 and Rho-ΔN α2δ4). Additionally all primers are listed in Supplemental Table S3.

Cell culture, transfection, Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

HEK293T cells were obtained from Clontech and cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with antibiotics, and 10% FBS. HEK293T cells were transfected at •70% confluency using Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. To test whether ELFN1 interacts with α2δ4, HEK293T cells were co-transfected with HA-tagged α2δ4 plus either control empty pcDNA3.1 plasmid or different c-myc-tagged ELFN1 constructs. To map the α2δ4-ELFN1 interaction binding site within α2δ4, HEK293T cells were co-transfected with the c-myc-tagged ecto domain of ELFN1 plasmid plus either control empty pcDNA3.1 or different HA-tagged α2δ4 constructs. The cells were harvested and processed for co-immunoprecipitation 24–48 hr post transfection.

Cellular lysates were prepared in ice-cold PBS IP buffer by sonication. After a 30-minute incubation at 4 °C, lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes. The supernatant was incubated with 20 μl of 50% protein G slurry (GE Healthcare) and 1.5 μg antibodies on a rocker at 4°C for 1 hour. After four washes with IP buffer, proteins were eluted from beads with 50 μl of SDS sample buffer. Proteins retained by the beads were analyzed with SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting using HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and an ECL West Pico or ECL West Femto (Thermo Scientific) detection system. Signals were captured on film and scanned by a densitometer. For quantification, band intensities from 3–5 separately prepared samples were determined by using the NIH ImageJ software. The integrated intensity of GAPDH was used for data normalization. For Co-IP, three independent experiments were performed to confirm reproducibility of the results. Experimenters were not blinded to sample identity but this information was not considered until the data analysis.

Fc pull down assay

The Fc tagged recombinant ectodomain of ELFN1 was produced in HEK293F cells and affinity purified using a protein A column as described (Cao et al., 2015). Transfected cells were lysed in ice-cold PBS IP buffer containing 1% Triton X and 150mM NaCl by sonication. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 20,800 g for 15 minutes, then incubated with 1.5 μg purified recombinant protein (or cell lysate containing Fc tagged proteins) and rotated end-over-end for 1 hour at 4 °C. Protein G beads (20 μl 50% Slurry) then were added and incubated for 30 minutes at 4 °C. After four washes with IP buffer, proteins were eluted from beads with 50 μl of 2X SDS sample buffer. Two completely independent experiments were performed to ensure reproducibility.

In vivo electroporation

In vivo electroporation was performed based on the protocol described previously (Matsuda and Cepko, 2004). Briefly, newborn mouse pups of different genotypes were first anesthetized by chilling on ice. A small incision was made in the eyelid and sclera near the lens with a 30-gauge needle. Then ~0.5μl of DNA solutions (Rho-α2δ4 and Rho-ΔN α2δ4, ~5μg/μl) containing 0.1% fast green were injected sub-retinally using a Hamilton syringe with 32 gauge blunt-ended needle. After injection, tweezer-style electrodes (7mm Platinum Tweezertrodes, BTX/Harvard Apparatus) applied with electrode gel (Spectra 360, Parker Laboratories, INC.) were placed to clamp softly the heads of the pups and five square pulses (50ms duration, 85V, 950ms intervals) were applied by using a pulse generator (Electro Square Porator, ECM 830, BTX/Harvard Apparatus). Following in vivo electroporation, retinas were harvested 4–5 weeks after electroporation, dissected and checked for mCherry positive retinas using fluorescence microscopy (Leica DMI 6000B).

Immunohistochemistry and light microscopy

Eyecups were dissected and fixed for 15 minutes with 4% paraformaldehyde followed by cryoprotection with 30% sucrose in PBS at 4°C overnight. Eyecups were transferred to 50% O.C.T (Tissue TeK) in 30% sucrose and equilibrated at room temperature for 30 minutes before they were embedded in 100% O.C.T.. Twelve to fourteen-micrometer frozen sections were obtained and blocked in PT1 (PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 10% donkey serum) for 1 hour, then incubated with the primary antibody in PT2 (PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 2% donkey serum) for 1 hour. After four-washes with PBS containing 0.1% Triton, sections were incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies in PT2 for 1 hour. After four washes, sections were mounted in Fluoromount (Sigma). For ELFN1 and α2δ4 staining, the slices were pretreated with Basic (pH=10.0) Antigen Retrieval Reagents (CTS016, R&D Systems) at 80°C for 5 minutes before the blocking step. The following dilutions of the antibodies were used: rat anti-α2δ4, 1:25; goat anti-Arrestin-C, 1:200; sheep anti-TRPM1, 1:100; sheep anti-mGluR6, 1:200; rabbit anti-ELFN1 (NTR), 1:200; rabbit anti-Cav1.4, 1:1K; rabbit anti-cone arrestin, 1:400; mouse anti-CtBP2, 1:1000; mouse anti-PKCα, 1:100, PNA conjugate, 1:100, rabbit anti-RGS7, 1:100; rabbit anti-RGS11, 1:100; rabbit anti-GPR197, 1:100; and chicken anti-RFP 1:200. Images were collected on a Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope. For double and triple staining, primary antibodies raised in the different species were used

Quantitative analysis of immunostaining puncta was performed using two to three regions of retina with different eccentricities from 2–3 mice for each genotype. Imaging parameters were the same for all sections within and across retinas. For the analysis of α2δ4 puncta morphology and density, all α2δ4 positive puncta within a constant field of 250 μm2 were manually outlined and their size and number were calculated by NIH ImageJ software. For ribbon density analysis, the distinction between rods and cones was kept by identifying cone terminals using cone-arrestin antibody staining. Ribbons were selected manually either within the cone terminal mask (cone) or within a comparable area outside of the cone terminal (rod) using NIS Element analysis software. To obtain ribbon density values, the number of elements was expressed as a fraction of the area within which they were counted. For CaV1.4 quantification in cones, regions of interest (ROIs) were first generated by outlining cone terminals indicated by cone-arrestin staining, CaV1.4 fluorescence intensity within each ROI was integrated and then normalized to the area of that ROI. The OPL width was measured by drawing a straight line vertical to ONL and INL layer which starts from the bottom of the nuclei in ONL and ends at the top of the nuclei in INL using Zen2.1 software. For quantification of ELFN1 and mGluR6 puncta, images of three different fields from both transfected (RFP positive) and non-transfected (RFP negative) regions within the same retina were first processed with background subtraction so that fluorescent intensity from non-specific staining (e.g fluorescence in INL and ONL) in each image is near 0. For each image, five 30×30 pixel squares placed in the OPL were set as ROIs and fluorescence intensity in each ROI was quantified by Image J software. Fluorescence intensities of all ROIs (5 ROIs for each image, 3 images for each retina, 3 retinas for each genotype) from transfected and non-transfected retina were averaged and compared. Analysis of dendritic sprouting was done using Zen2.1 microscope analysis software. The dendrites were traced determining their length and position. Sprouting was defined by dendritic tips reaching past at least one nucleus in the ONL region. Cone density and terminal sizes were determined using NIH ImageJ similarly as described for the morphometric analysis of synaptic puncta. Experimenters were not blinded to sample identity but the genotype information was not considered until the data analysis.

Electron Microscopy

Eyes from two different mice for each genotype were enucleated, cleaned of extra-ocular tissue, and pre-fixed for 15 min in cacodylate-buffered half-Karnovsky’s fixative containing 2mM calcium chloride. Then eyecups were hemisected along the vertical meridian and fixed overnight in the same fixative. The specimens were rinsed with cacodylate buffer and postfixed in 2% osmium tetroxide in water for 1 hour, en-block stained with 1% uranyl acetate for 25 minutes, then gradually dehydrated in an increasing ethanol and acetone series (30–100%), and embedded in Durcupan ACM resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences, PA). Blocks were cut with 60-nm-thickness, and were stained with 3% uranyl acetate and 0.5% lead citrate. Sections were examined on a Tecnai G2 spirit BioTwin (FEI) transmission electron microscope at 80 or 100 kV accelerating voltage. Images of regions with different eccentricities were captured with a Veleta CCD camera (Olympus) operated by TIA software (FEI). Experimenters were not blinded to the genotype.

Electroretinography (ERG)

Electroretinograms were recorded by using the UTA system and a Big-Shot Ganzfeld (LKC Technologies). Three mice (~5 weeks old) of each genotype were dark-adapted (≥6 h) and prepared for recordings using a red dim light. Mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine mixture containing 100 and 10 mg/kg, respectively. Recordings were obtained from the right eye only, and the pupil was dilated with 2.5% phenylephrine hydrochloride (Bausch & Lomb), followed by the application of 0.5% methylcellulose. Recordings were performed with a gold loop electrode supplemented with contact lenses to keep the eyes immersed in solution. The reference electrode was a stainless steel needle electrode placed subcutaneously in the neck area. The mouse body temperature was maintained at 37 °C by using a heating pad controlled by ATC 1000 temperature controller (World Precision Instruments). ERG signals were sampled at 1 kHz and recorded with 0.3-Hz low-frequency and 300-Hz high-frequency cut-offs.

Full field white flashes were produced by a set of LEDs (duration < 5 ms) for flash strengths ≤ 2.5 cd·s/m2 or by a Xenon light source for flashes > 2.5 cd·s/m2 (flash duration < 5 ms). ERG responses were elicited by a series of flashes ranging from 1× 10−5 to 800 cd*s/m2 in 10-fold increments. Ten trials were averaged for responses evoked by flashes up to 0.1 cd*s/m2, and three trials were averaged for responses evoked by 0.5 and 1 cd*s/m2 flashes. Single flash responses were recorded for brighter stimuli. To allow for recovery, interval times between single flashes were as follows: 5 s for 1× 10−5 to 0.1 cd*s/m2, 30 s for 0.5 and 1 cd*s/m2, 60 s for 5 and 10 cd*s/m2, and 180 s for 100 and 800 cd*s/m2 flashes. Rod-saturating light background of 50 cd/m2 was administered for 5 minutes for recording cone-only ERGs. Ten trials elicited from 100 cd*s/m2 flashes were averaged at an interval recovery time of 1 second between flashes.

ERG traces were analyzed using the EM LKC Technologies software and Microsoft Excel. The b-wave amplitude was calculated from the bottom of the a-wave response to the peak of the b-wave. The data points from the b-wave stimulus–response curves were fitted by Equation 1 using the least-square fitting method in GraphPad Prism6.

| (1) |

The first term of this equation describes rod-mediated responses (r), and the second term accounts primarily for responses that were cone mediated (usually at flash intensities ≥1 cd*s/m2 for dark-adapted mice; index c). Rmax,r and Rmax,c are maximal response amplitudes, and I0.5,r and I0.5,c are the half-maximal flash intensities. Stimulus responses of retina cells increase in proportion to stimulus strength and then saturate, this is appropriately described by the hyperbolic curves of this function. Experimenters were not blinded to the identity of the subjects but the genotype information was not considered until the data analysis.

Single cell patch-clamp recordings

Light-evoked responses of photoreceptors and bipolar cells were made from dark-adapted retinal slices using methods described previously (Arman and Sampath, 2012). Briefly, mice were dark-adapted overnight and euthanized according to protocols approved by the University of California, Los Angeles Animal Research Committee (Protocol 14-005). Eyes were enucleated under infrared light, retinas were isolated, and 200-μm thick slices were cut with a vibrating microtome. Slices were superfused with bicarbonate-buffered Ames’ media (equilibrated with 5% CO2/95% O2) heated to 35–37°C, were visualized in the infrared, and were stimulated with a blue light-emitting diode (λmax ~ 470 nm for rod and λmax ~ 405 for cone stimulation). Light-evoked responses were measured using patch electrodes in voltage clamp mode (Vm = −40 mV for photoreceptor cells and Vm = −60 mV for bipolar cells), using an electrode internal solution consisting of (in mM): 125 K-aspartate, 10 KCl, 10 HEPES, 5 N-methyl-glucamine/HEDTA, 0.5 CaCl2, 1 ATP-Mg, and 0.2 GTP-Mg; pH was adjusted to ~7.3 with N-methyl-glucamine hydroxide, and osmolarity was adjusted to ~280 mOsm. Patch recordings from cones additionally included 1 mM NADPH in the internal solution. The electrode internal solution for measurements of the synaptic Ca2+ current from photoreceptors consisted of (in mM): 12 Tetramethylammonium-Cl, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, 2 QX-314, 11 ATP-Mg, 0.5 GTP·Tris, and 0.5 MgCl2; pH was adjusted to ~7.3 with N-methyl-glucamine hydroxide, and osmolarity was adjusted to ~280 mOsm.

Light stimulation consisted of 10ms flashes of light that varied in strength from those yielding a just discernable response to those that generate a maximal response. Light-evoked responses were sampled at 1 or 10 kHz and filtered at 300 Hz. Flash strengths are reported as a photon flux at the respective wavelengths for rod or cone photoreceptor stimulation. To distinguish between ON-RBCs, ON-CBCs, and OFF-CBCs the polarity and time course of the response were considered, along with the cell’s morphology. Cell visualization was accomplished by adding a fluorophore to the electrode internal solution. This fluorophore was either Lucifer Yellow or Alexa-750, when visualization in the far red without significant visual pigment bleaching was required. Responses of ON-RBCs and ON-and OFF-CBCs were from the same slices, typically within 100 μm of one another. Experimenters were not blinded to the identity of the subjects but the genotype information was not considered until the data analysis.

Evaluation of vision by behavioral water maze task

Mouse visual behavior was assessed using a water maze task with a visible escape platform (Cao et al., 2015). Mice are natural swimmers, and this task exploits their innate inclination to escape from water to a solid substrate. This task uses an ability of a mouse to see a visible platform with a timed escape from water, as an index of its visual ability. Before testing, mice (~5 weeks old) readily learned to swim to the visible escape-platform and performance usually plateaued at around 10 seconds within 15 trials for all treated groups. Mice that did not learn the task, e.g. performance did not improve or plateau for at least the last 3 or more consecutive trials or had any visible motor deficits were discarded from the experiment. Visually-guided behavior was tested at 100, 0.01, and 0.001 cd/m2 and timed-performances from 20 trials (4 sessions of 5 trials each) for each mouse (4–5 mice for each genotype) at each light-intensity were averaged. Uniform room luminance settings were stably achieved by an engineered adjustable light-source and constantly monitored with a luminance meter LS-100 (Konica Minolta). To be certain that we were measuring the mice’s visual ability only and not memory, the platform was placed pseudo-randomly in the water tank and all external visual cues were eliminated. Experimenters were not blinded to the identity of the subjects but the genotype information was not considered until the data analysis.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

ANOVA and Student’s t-test was used for performing all pairwise comparisons. A minimum of 3 biological replicates was used for each statistical analysis. Sample sizes ranging from 3 to 11 for biochemical assays (e.g. western blot and IHC), electrophysiological assays (e.g. ERG and single cell recording) and visually guided water maze behavioral assays were estimated based on minimum number sufficient to invoke Central Limit Theorem and expected effect sizes observed in previous studies examining the same endpoints. Data from all subjects and samples examined were included with no exclusions. SEM values are provided for each of the plotted mean. Details on particular quantification procedures and analyses are provided in corresponding section of STAR Methods section.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

α2δ4 is essential for organizing the presynaptic compartment of rod photoreceptors

Elimination of α2δ4 in mice abolishes synaptic contacts of rods, but not cones

α2δ4 forms a macromolecular complex with the rod synaptogenic mediator, ELFN1

α2δ4 sets the abundance and biophysical properties of CaV1.4 channels.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Ms. Natalia Martemyanova for producing and maintaining mice examined in this study. We thank Drs. Amy Lee (University of Iowa) and Francoise Haeseleer (University of Washington) for their generous donation of published rabbit anti-CaV1.4 and rat anti-α2δ4 antibodies, Dr. Vadim Arshavsky (Duke University) for the gift of Rho4.2-mCherry construct and Ronald G. Gregg (University of Louisville) for donating the Nob5GPR179 and CaV1.4 KO mouse strains. This work was supported by NIH grants: EY018139 (KAM), EY017606, EY000331 (APS) and an Unrestricted Grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc to the Stein Eye Institute, UCLA.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.W. performed all cell biological experiments described in the paper, including immunostaining of retina cross-sections, in vivo electroporation and biochemical experiments mapping protein-protein interaction sites; K.E.F. and N.T.I. performed single cell patch clamp recordings and analysis of electrophysiological data; I.S. performed ERG and behavioral analysis of mouse strains; Y.C. performed biochemical experiments analyzing protein-protein interactions and participated in characterization of α2δ4 knockout mice. D.G-G. and N.K. conducted EM experiments; B.T. and K.B. generated and characterized R26floxstop-TeNT/Pcdh21-Cre mouse model and supplied tissues for analysis, T.O. generated a critical reagent (CAST knockout mice), A.P.S. designed patch clamp experiments, analyzed electrophysiological data, and wrote the paper; K.A.M. designed the study, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arman AC, Sampath AP. Dark-adapted response threshold of OFF ganglion cells is not set by OFF bipolar cells in the mouse retina. J Neurophysiol. 2012;107:2649–2659. doi: 10.1152/jn.01202.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ba-Abbad R, Arno G, Carss K, Stirrups K, Penkett CJ, Moore AT, Michaelides M, Raymond FL, Webster AR, Holder GE. Mutations in CACNA2D4 Cause Distinctive Retinal Dysfunction in Humans. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:668–671. e662. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangalore R, Mehrke G, Gingrich K, Hofmann F, Kass RS. Influence of L-type Ca channel alpha 2/delta-subunit on ionic and gating current in transiently transfected HEK 293 cells. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H1521–1528. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.5.H1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann CI, Marder E. From the connectome to brain function. Nat Methods. 2013;10:483–490. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S, Kelly ME. Calcium channels at the photoreceptor synapse. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2002;514:465–476. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0121-3_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Masuho I, Okawa H, Xie K, Asami J, Kammermeier PJ, Maddox DM, Furukawa T, Inoue T, Sampath AP, et al. Retina-specific GTPase accelerator RGS11/G beta 5S/R9AP is a constitutive heterotrimer selectively targeted to mGluR6 in ON-bipolar neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9301–9313. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1367-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Pahlberg J, Sarria I, Kamasawa N, Sampath AP, Martemyanov KA. Regulators of G protein signaling RGS7 and RGS11 determine the onset of the light response in ON bipolar neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:7905–7910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202332109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Posokhova E, Martemyanov KA. TRPM1 forms complexes with nyctalopin in vivo and accumulates in postsynaptic compartment of ON-bipolar neurons in mGluR6-dependent manner. J Neurosci. 2011;31:11521–11526. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1682-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Sarria I, Fehlhaber KE, Kamasawa N, Orlandi C, James KN, Hazen JL, Gardner MR, Farzan M, Lee A, et al. Mechanism for Selective Synaptic Wiring of Rod Photoreceptors into the Retinal Circuitry and Its Role in Vision. Neuron. 2015;87:1248–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo A, Piano I, Demontis GC, Bacchi N, Casarosa S, Della Santina L, Gargini C. TMEM16A is associated with voltage-gated calcium channels in mouse retina and its function is disrupted upon mutation of the auxiliary alpha2delta4 subunit. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:422. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy JS, Ferron L, Kadurin I, Pratt WS, Dolphin AC. Functional exofacially tagged N-type calcium channels elucidate the interaction with auxiliary alpha2delta-1 subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:8979–8984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403731111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA. Signaling complexes of voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels. Neurosci Lett. 2010;486:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Arco M, Margas W, Cassidy JS, Dolphin AC. The upregulation of alpha2delta-1 subunit modulates activity-dependent Ca2+ signals in sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2015;35:5891–5903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3997-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sevilla Muller LP, Liu J, Solomon A, Rodriguez A, Brecha NC. Expression of voltage-gated calcium channel alpha(2)delta(4) subunits in the mouse and rat retina. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521:2486–2501. doi: 10.1002/cne.23294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit J, Hong W, Luo L, Ghosh A. Role of leucine-rich repeat proteins in the development and function of neural circuits. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2011;27:697–729. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin AC. The alpha2delta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1828:1541–1549. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]