Abstract

Objective

To determine the accuracy of inertial measurement unit data from a mobile device using the mobile device relative to posturography to quantify postural stability in individuals with Parkinson’s disease (PD).

Design

Criterion standard.

Setting

Motor control laboratory at Cleveland Clinic.

Participants

Fourteen mild to moderate individuals with PD and 14 healthy age-matched community dwelling controls completed the project.

Interventions

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measures

Center of mass (COM) acceleration measures were compared between the mobile device and NeuroCom force platform to determine accuracy of mobile device measurements during performance of the Sensory Organization Test (SOT). Analyses examined test-retest reliability for both systems and sensitivity of: 1) the Equilibrium Score from the SOT and 2) COM acceleration measures from the force platform and mobile device to quantify postural stability across populations.

Results

Metrics of COM acceleration from inertial measurement unit data and NeuroCom force platform were significantly correlated across balance conditions and groups (Pearson’s r ranged from 0.35 to 0.97). The SOT Equilibrium Scores failed to discriminate individuals with PD and controls. However, the multi-planar measures of COM acceleration from the mobile device exhibited good to excellent reliability across SOT conditions and were able to discriminate individuals with PD and controls in conditions with the greatest balance demands.

Conclusions

Metrics employing medial-lateral movement produce a more sensitive outcome than the Equilibrium Score in identifying postural instability associated with PD. Overall, the output from the mobile device provides an accurate and reliable method of rapidly quantifying balance in individuals with PD. The portable and affordable nature of a mobile device with the application make it ideally suited to utilize biomechanical data to aid in clinical decision-making.

Keywords: Parkinson Disease; Postural Balance; Feedback, Sensory; Accelerometry; Mobile Applications

Postural instability is a disabling consequence of Parkinson’s disease (PD) with approximately 70% of individuals falling at least once each year1. Disease-related declines in balance result in hospitalization and decreased quality of life2,3. Objective evaluations of postural stability in individuals with PD are critical to advance medical management and facilitate the development of interventions that may mitigate the negative effects of PD on balance.

It has been proposed that PD-related postural instability is linked to striatal dopamine loss in the basal ganglia4,5. While the basal ganglia likely receive suitable afferent information from visual, vestibular, and somatosensory inputs to maintain balance, dopamine depletion limits the ability of the central nervous system to integrate and re-weight relevant postural sensory information leading to increased fall rates compared to healthy peers6–11. Historically, force plate posturography measures have been used to characterize changes in balance under varying sensory conditions12–16.

The Sensory Organization Test (SOT) estimates the relative contribution of visual, vestibular, and somatosensory inputs used to maintain postural stability17,18. The SOT has been utilized to evaluate changes in postural stability in individuals with PD as a result of rehabilitation, medication, or disease severity11,13,19–22. However, discrepancies exist across studies comparing SOT performance in individuals with mild to moderate PD and healthy controls, which questions use of the SOT and corresponding Equilibrium Score outcome measure in this patient group13,21,22.

The Equilibrium Score quantifies the peak amplitude of the anterior-posterior (AP) projection of the center of mass (COM) onto the force platform (i.e. angular displacement) within a given sensory condition. The composite Equilibrium Score consists of the weighted average of the Equilibrium Scores across all six conditions18. Movement in the medial-lateral (ML) direction is not considered in the computation of the Equilibrium Score, though postural stability is achieved by regulating movement in AP and ML directions23,24. The exclusion of movement in the ML direction may explain discrepancies in SOT outcomes across study findings25,26.

The most prevalent model used to characterize postural stability during quiet standing is the inverted pendulum model24,27, in which center of pressure (COP) and COM are utilized to evaluate balance. Briefly, the COP represents the weighted average of all forces applied perpendicular to the ground and COM is the weighted average of each body segment in space. The inverted pendulum model contends that the movement of COP varies with the movement of COM to preserve the COM over the base of support; thus, the linkage between controlling COP about the COM allows for the maintenance of a steady posture24,27.

The inverted pendulum model is reliant on activation of sensory systems and central nervous system integration to maintain postural stability24. Despite impaired basal ganglia function, individuals with PD often exhibit similar levels of COM displacement compared to healthy controls28. However, the frequency of adjustments necessary to maintain this COM area of displacement requires more frequent corrections of postural sway, as reflected by abnormally higher derivatives of displacement, such as acceleration28,29.

The difference between the COP and COM (COP-COM) displacement measures is proportional to the acceleration of the COM, which is considered an error signal that the postural control system is sensing24. Therefore, acceleration of the COM provides a more thorough quantification of balance than COP and COM displacement individually24,30. Acceleration of the COM has been used to identify significant differences in postural stability between individuals with neurological disorders, older adults, and young adults, which reflect abnormal balance responses induced by aging and disease31–33. In order to capture the movement of COM, which is not measured directly by a force platform, biomechanical models utilizing Newton-Euler equations of motion and proprietary software have been developed that utilize the inverted pendulum model to estimate COM during quiet standing34–37.

To obtain a precise measure of postural stability that incorporates COM acceleration with ease, an application was developed to gather data from the accelerometer within the Apple iPad (Cupertino, CA)38–41. Correlation between inertial sensors within the iPad and 3D motion analysis was established in a cohort of individuals with Parkinson’s disease, healthy older adults, and healthy young adults38,40,41. The aims of the current project were: 1) validate use of inertial sensors within the mobile device relative to ground reaction forces from the NeuroCom force platform with individuals with PD and controls, 2) estimate test-retest reliability of the mobile device and NeuroCom systems, and 3) evaluate the capability of mobile device and NeuroCom measures to detect postural instability during the SOT. The development of a validated biomechanical method, packaged within a mobile platform, to characterize postural instability in PD would provide an attractive approach to facilitate understanding and treatment of PD related postural instability.

METHODS

Participants

Fourteen individuals with mild to moderate PD (7 females; mean age 63±8) and fourteen healthy age-matched controls (8 females; mean age 65±9) completed the project; those with PD were on anti-parkinsonian medication (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of characteristics for individuals with PD

| Subject | Gender | Age (years) |

BMI (kg/m2) |

Duration of disease (years) |

MDS- UPDRS-III |

Hoehn and Yahr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 57 | 21.6 | 7 | 48 | 2 |

| 2 | F | 70 | 32.3 | 5 | 47 | 3 |

| 3 | M | 59 | 33.5 | 3 | 41 | 2 |

| 4 | F | 66 | 32.0 | 2 | 27 | 2 |

| 5 | M | 53 | 37.0 | 4 | 43 | 2 |

| 6 | M | 80 | 24.9 | 8 | 48 | 3 |

| 7 | F | 69 | 25.0 | 4 | 34 | 2 |

| 8 | F | 55 | 31.0 | 3 | 48 | 3 |

| 9 | M | 60 | 27.3 | 12 | 60 | 3 |

| 10 | F | 58 | 38.6 | 6 | 25 | 2 |

| 11 | M | 71 | 29.7 | 1 | 28 | 2 |

| 12 | F | 55 | 21.1 | 7 | 30 | 2 |

| 13 | M | 72 | 28.0 | 11 | 40 | 3 |

| 14 | F | 56 | 27.9 | 5 | 29 | 2 |

| Mean | 62.9 | 29.3 | 5.6 | 39.1 | 2.4 | |

| SD | 8.3 | 5.2 | 3.2 | 10.5 | 0.5 | |

Severity of Parkinson’s disease was evaluated by the same trained rater using the Motor Section (III) of the Movement Disorder Society (MDS)-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) and the Hoehn and Yahr Scale. Healthy, age-matched (within three years) controls were recruited. All participants provided consent to procedures approved by the institutional review board.

Data Collection

Participants completed the NeuroCom SOT using the Smart Balance Master (NeuroCom International, Clackamas, OR) while the mobile device was affixed to their waist (level with the sacrum) to approximate whole body COM during data collection. For data synchronization purposes, the mobile device received an output signal from the NeuroCom via audio jacks at the onset of each SOT trial. The SOT consisted of three 20-second trials under six different conditions: SOT1: Fixed surface, eyes open (fixed-fixed); SOT2: Fixed surface, eyes closed (fixed-absent); SOT3: Fixed surface, sway referenced vision (fixed-sway); SOT4: Sway referenced surface, eyes open (sway-fixed); SOT5: Sway referenced surface, eyes closed (sway-absent); and SOT6: Sway referenced surface, sway referenced vision (sway-sway). The conditions used in the SOT included sway referencing, which entails AP tilt of the support platform and/or of the visual surround in direct response to the individual’s COP. All participants wore a harness for safety while completing the SOT.

Data Analysis

COM Acceleration

The COM acceleration was derived from the NeuroCom force platform utilizing the inverted pendulum model of postural stability and compared with mobile device COM acceleration. The NeuroCom system quantifies COP in the frontal plane (ML direction) and in the sagittal plane (AP direction). A single-link inverted pendulum model relates COP with COM, which can be shown using the Newton-Euler equations:

| (1) |

where COMx is the COM position with respect to the ankle joint in the ML direction, COPx is the COP position with respect to the ankle joint in the ML direction, If is the total body moment of inertia about the ankle joint in the frontal plane, m is the subject’s body mass, g is acceleration due to gravity, h is the height of the COM above the ankle joint, and CÖMx is the COM linear acceleration in the ML direction and

| (2) |

where y refers to displacements in the AP direction and Isa is the total body moment of inertia about the ankle joint in the sagittal plane.

Using equations 1 and 2, a mathematical model was developed to compute COM position using the force plate COP positional data34,42. Once the COM position was computed, ML and AP COM accelerations were calculated by determining the second order derivative of the positional data with respect to time across populations for all balance conditions and trials.

The COM acceleration was calculated from the mobile device and NeuroCom systems recorded at a 100-Hz sampling frequency and after applying a 3.5-Hz cut-off, 4th order, low-pass Butterworth filter. Four metrics that have previously been shown to be significantly correlated with 3-D motion analysis to characterize ML and AP COM acceleration were computed for each balance trial38,40,41: 1) peak-to-peak (P2P), a measure of amplitude of displacement; 2) normalized path length (NPL) which normalizes the data using sampling rate and total time of each balance trial; 3) the natural log of the root mean square distance (logRMS) which quantifies the magnitude of COM displacements; and 4) ellipsoid area (95% Ellipse Area) that, with 95% of probability, contained the center of the points of sway in the ML and AP planes. The logarithmic transformation was computed for the RMS in order to ensure normality required for statistical analyses.

NeuroCom Equilibrium Scores

NeuroCom Equilibrium Scores, ranging from 0–100% (i.e. a score of 100% represents no postural sway) were quantified by the NeuroCom software for each trial. The software computes Equilibrium Score by comparing angular difference between the subject’s calculated maximum AP COM displacement and the subject’s theoretical maximum sway of 12.5°18. Equilibrium Scores were averaged within each condition (three trials per condition)18.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 21.0, Chicago, IL. Differences were assumed significant when P < 0.05.

NeuroCom Equilibrium Scores

Differences between populations for Equilibrium Score data during each SOT condition were determined using two sample t-tests. Welch correction was applied to account for possible unequal variances.

COM Acceleration

Each metric that characterized COM acceleration (P2P, NPL, logRMS, and 95% Ellipse Area) quantified by the NeuroCom and mobile device were evaluated for goodness of fit via Bland-Altman plots. All subjects (individuals with PD and controls) were combined for the correlation analysis and each trial was treated as a separate occurrence. In this approach, the differences between each measure quantified by the NeuroCom and mobile device were subtracted from each other to quantify the measurement error (i.e. P2PiPad − P2PNeuroCom, NPLiPad − NPLNeuroCom, etc.) and were plotted against the average of each measure on a trial-by-trial basis from the two systems, which represented the best approximation of the true value for each outcome measure. The mean of the difference and the respective limits of agreement (defined as mean ± 1.96 SD) are reported for each outcome measure across SOT conditions, where a smaller gap between the limits of agreement indicates less variability and more consistency between the two systems.

Test-retest reliability was estimated for P2P, NPL, logRMS, and 95% Ellipse Area values between the three trials of each SOT condition for the NeuroCom and mobile device. Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and 95% confidence intervals were used to determine the ratio of between-subject to the total variance in the NeuroCom and mobile device measures for the six SOT conditions. Each ICC was computed using two-way mixed effects analysis of variance with a model comprised of all subjects (individuals with PD and controls) across each trial number. The test–retest reliability was categorized into four groups: poor (0–0.39), fair (0.40–0.59), good (0.60–0.74), and excellent (0.75–1.0).

Differences between populations for COM acceleration measures during each SOT condition were determined using two sample t-tests. Welch correction was applied to account for possible unequal variances.

RESULTS

NeuroCom Equilibrium Scores

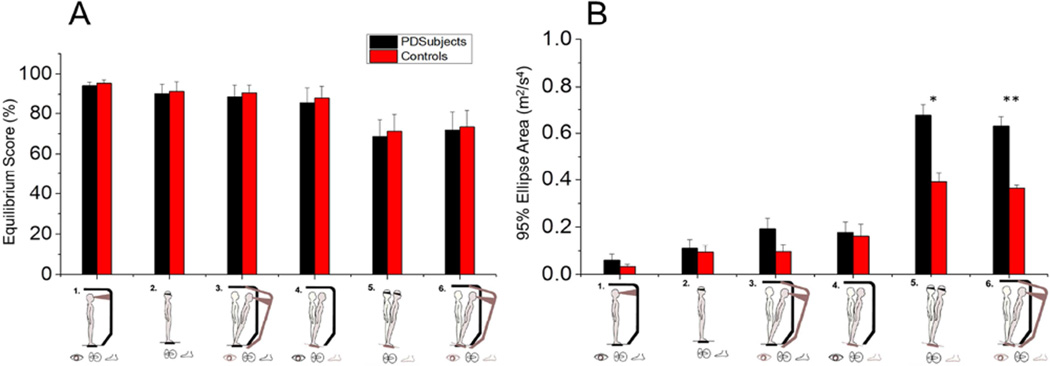

No significant differences in Equilibrium Scores were found between populations during the various SOT conditions (Table 2; Fig. 1A).

Table 2.

Mean ± SD of Equilibrium Scores with corresponding P-values for the SOT conditions using the NeuroCom measures

| Condition | Individuals with PD | Control Subjects | P-values |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOT1: Fixed-fixed | 94.2 ± 1.7 | 95.5 ± 1.7 | 0.315 |

| SOT2: Fixed-absent | 90.3 ± 4.7 | 91.4 ± 4.8 | 0.329 |

| SOT3: Fixed-sway | 88.4 ± 6.2 | 90.7 ± 3.9 | 0.157 |

| SOT4: Sway-fixed | 85.3 ± 7.8 | 87.6 ± 6.3 | 0.329 |

| SOT5: Sway-absent | 68.7 ± 12.3 | 71.2 ± 10.4 | 0.345 |

| SOT6: Sway-sway | 71.9 ± 10.8 | 73.4 ± 13.1 | 0.451 |

Figure 1.

(A) Equilibrium Scores and (B) 95% Ellipse Areas quantifying differences in postural stability between populations during each SOT condition. * Asterisk denotes p-values < 0.05; ** Asterisk denotes p-values < 0.005.

COM Acceleration

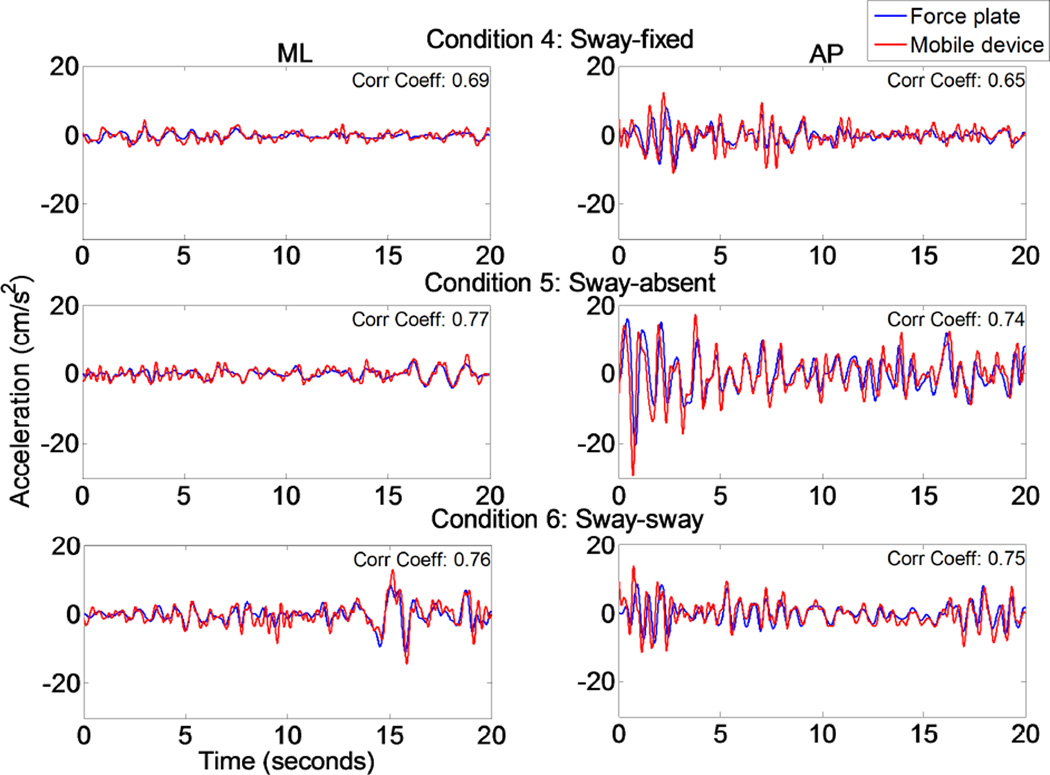

The COP and COM trajectories in the AP direction recorded from the NeuroCom system for six 20-second trials of quiet standing of one representative subject are presented (Fig. 2). The figure demonstrates how closely COP and COM are in phase and how COP oscillates around COM. The COM acceleration was computed from force plate data and directly compared to COM acceleration recorded by the mobile device across balance conditions. Through visual inspection and the correlation coefficients provided, Figure 3 indicates that the COM acceleration converted from force platform COP measures correlated with the mobile device ML and AP COM acceleration measurements.

Figure 2.

Trajectories of AP COP and COM position under the six SOT conditions. Using the NeuroCom, the COP was recorded and COM position was computed using the inverted pendulum model.

Figure 3.

Typical 20-second balance trials showing how closely the mobile device’s accelerometer can track the NeuroCom’s force platform COM acceleration measures.

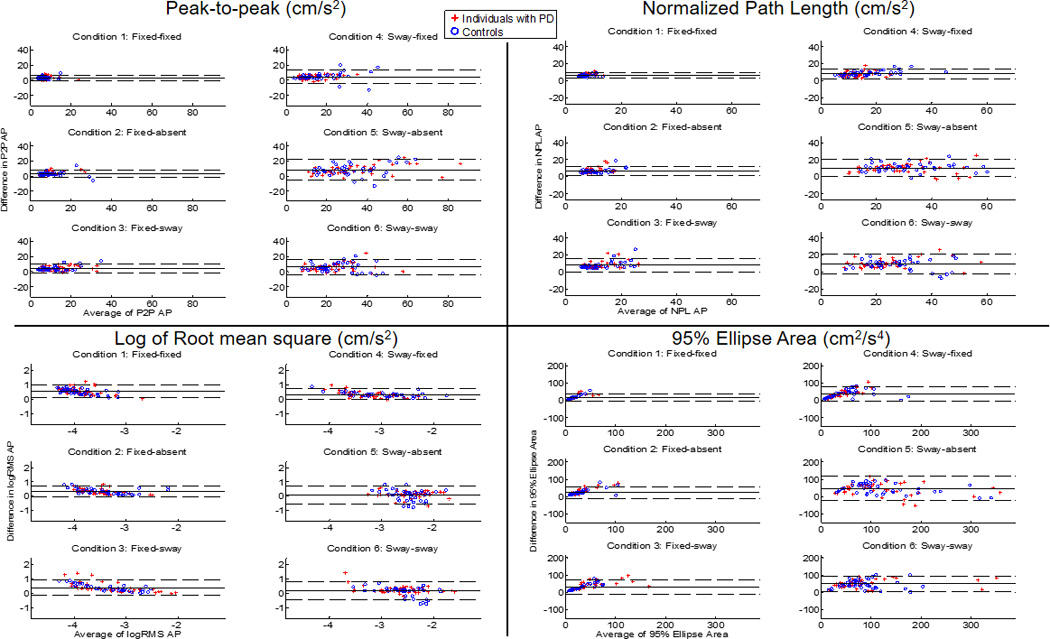

Bland-Altman plots revealed that the mean difference (bias) across all outcome metrics for each condition was close to 0 (units are in cm/s2 and cm2/s4), with SOT1 (fixed-fixed) showing the smallest and SOT5 (sway-absent) and SOT6 (sway-sway) showing the largest mean difference (Table 3; Fig. 4). Inspection of the limits of agreement in the Bland-Altman plots revealed that 95% of the measurement error between the two systems was from −0.3 to 7.3 cm/s2 for AP P2P, 3.5 to 9.4 cm/s2 for AP NPL, 0.1 to 1.0 cm/s2 for AP logRMS and −3.5 to 37.5 cm2/s4 for 95% Ellipse Area in the condition of best agreement (SOT1) and from −5.4 to 21.9 cm/s2 for AP P2P, −0.3 to 20.8 cm/s2 for AP NPL, −0.4 to 0.8 cm/s2 for AP logRMS, and −25.1 to 116.2 cm2/s4 for 95% Ellipse Area in the condition with the poorest agreement (SOT5 or SOT6).

Table 3.

Mean Bias (Lower-Upper Bound limits) from Bland-Altman Analysis across outcome measures, sway directions, and SOT conditions

| Peak-to-peak (cm/s2) | Normalized path length (cm/s2) | Log of Root mean square (cm/s2) | 95% Ellipse Area (cm2/s4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOT Condition |

ML | AP | ML | AP | ML | AP | ML/AP |

| 1 | 3.5 (0.9–6.2) | 3.5 (−0.3–7.3) | 6.2 (3.3–9.1) | 6.5 (3.5–9.4) | 1.0 (0.4–1.5) | 0.5 (0.1–1.0) | 17.0 (−3.5–37.5) |

| 2 | 3.6 (1.2–6.0) | 3.3 (−1.6–8.2) | 6.7 (3.3–10.1) | 6.6 (1.2–12.0) | 0.8 (0.3–1.3) | 0.3 (−0.1–0.7) | 23.7 (−8.8–56.3) |

| 3 | 4.6 (0.6–8.6) | 4.3 (−1.3–9.9) | 7.9 (3.0–12.7) | 8.1 (0.1–16.0) | 0.9 (0.3–1.4) | 0.4 (−0.2–0.9) | 31.8 (−8.6–72.2) |

| 4 | 4.8 (0.8–8.7) | 4.6 (−4.7–14.0) | 8.1 (3.9–12.3) | 8.4 (2.5–14.3) | 0.9 (0.3–1.4) | 0.3 (−0.1–0.7) | 36.6 (−6.0–79.1) |

| 5 | 5.8 (−0.7–12.3) | 8.2 (−5.4–21.9) | 10.2 (1.4–18.9) | 10.2 (−0.3–20.8) | 0.5 (−0.3–1.4) | 0.1 (−0.5–0.7) | 45.6 (−25.1–116.2) |

| 6 | 6.5 (−0.4–13.4) | 6.1 (−4.4–16.6) | 10.4 (3.4–17.5) | 9.4 (−1.7–20.6) | 0.7 (−0.1–1.5) | 0.2 (−0.4–0.8) | 48.3 (1.6–94.9) |

Abbreviations: ML, Medial-lateral; AP, Anterior-posterior.

Figure 4.

Bland-Altman plots for each outcome measure (quantifying AP sway) across SOT conditions, where the difference in each outcome measure (P2PiPad − P2PNeuroCom, NPLiPad − NPLNeuroCom, etc.) between systems is plotted against the average of two values on a trial-by-trial basis. The solid lines represent the mean difference in values; dashed lines represent the upper and lower limits of agreement (mean difference ± 1.96 SD). Groups were combined for the analysis (Red plus symbols indicate PD subjects; Blue circles indicate Controls).

Reliability of the mobile device on a test-retest basis exceeded the reliability of the NeuroCom for all four metrics characterizing COM acceleration (Table 4). Test–retest reliability estimates for P2P of mobile device measurements taken across the three reiterations ranged from good to excellent (ML: 0.64–0.74; AP: 0.61–0.85) for SOT1-SOT4 and excellent (ML: 0.78–0.85; AP: 0.85–0.86) for SOT5-SOT6. The NPL, logRMS, and 95% Ellipse Area measures exhibited slightly higher ICC values, with mobile device ICC values ranging from good to excellent (0.74–0.90) for SOT1-SOT4 and excellent (0.88–0.92) for SOT5-SOT6.

Table 4.

Test-retest reliability of three trials for the six SOT conditions: Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (95% confidence intervals) were calculated across outcome measures for both mobile device and Neurocom systems

| Peak-to-peak (cm/s2) | Normalized path length (cm/s2) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML | AP | ML | AP | |||||

| SOT Condition |

Mobile device | NeuroCom | Mobile device | NeuroCom | Mobile device | NeuroCom | Mobile device | NeuroCom |

| 1 | 0.64 (0.32–0.82) | 0.61 (0.26–0.80) | 0.62 (0.28–0.81) | 0.67 (0.38–0.84) | 0.83 (0.68–0.91) | 0.53 (0.19–0.88) | 0.75 (0.54–0.88) | 0.74 (0.51–0.87) |

| 2 | 0.69 (0.41–0.84) | 0.60 (0.25–0.80) | 0.61 (0.27–0.81) | 0.56 (0.21–0.86) | 0.82 (0.67–0.91) | 0.78 (0.58–0.89) | 0.78 (0.58–0.89) | 0.82 (0.66–0.91) |

| 3 | 0.70 (0.44–0.85) | 0.60 (0.25–0.80) | 0.67 (0.38–0.84) | 0.62 (0.29–0.81) | 0.88 (0.78–0.94) | 0.79 (0.60–0.90) | 0.83 (0.69–0.92) | 0.79 (0.62–0.90) |

| 4 | 0.74 (0.51–0.87) | 0.66 (0.35–0.83) | 0.85 (0.72–0.93) | 0.86 (0.74–0.93) | 0.88 (0.77–0.94) | 0.83 (0.68–0.91) | 0.90 (0.81–0.95) | 0.79 (0.61–0.90) |

| 5 | 0.78 (0.59–0.89) | 0.73 (0.50–0.87) | 0.86 (0.73–0.93) | 0.78 (0.58–0.89) | 0.88 (0.78–0.94) | 0.77 (0.56–0.88) | 0.91 (0.83–0.96) | 0.89 (0.79–0.94) |

| 6 | 0.85 (0.72–0.93) | 0.81 (0.65–0.91) | 0.85 (0.72–0.93) | 0.78 (0.60–0.89) | 0.92 (0.86–0.96) | 0.88 (0.77–0.94) | 0.91 (0.83–0.96) | 0.88 (0.78–0.94) |

| Log of Root mean square (cm/s2) | 95% Ellipse Area (cm2/s4) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML | AP | ML/AP | ||||

| SOT Condition |

Mobile device | NeuroCom | Mobile device | NeuroCom | Mobile device | NeuroCom |

| 1 | 0.76 (0.55–0.88) | 0.62 (0.29–0.81) | 0.74 (0.52–0.87) | 0.69 (0.42–0.85) | 0.76 (0.55–0.88) | 0.61 (0.26–0.80) |

| 2 | 0.78 (0.60–0.89) | 0.54 (0.20–0.90) | 0.74 (0.51–0.87) | 0.71 (0.45–0.85) | 0.82 (0.66–0.91) | 0.79 (0.61–0.90) |

| 3 | 0.76 (0.56–0.88) | 0.77 (0.57–0.89) | 0.75 (0.54–0.88) | 0.70 (0.44–0.85) | 0.88 (0.78–0.94) | 0.84 (0.70–0.92) |

| 4 | 0.81 (0.64–0.91) | 0.72 (0.48–0.86) | 0.82 (0.67–0.91) | 0.82 (0.66–0.91) | 0.86 (0.74–0.93) | 0.78 (0.59–0.89) |

| 5 | 0.90 (0.81–0.95) | 0.86 (0.73–0.93) | 0.90 (0.82–0.95) | 0.87 (0.75–0.93) | 0.90 (0.81–0.95) | 0.89 (0.80–0.95) |

| 6 | 0.88 (0.78–0.94) | 0.76 (0.55–0.88) | 0.92 (0.85–0.96) | 0.89 (0.79–0.94) | 0.91 (0.84–0.96) | 0.91 (0.83–0.95) |

Abbreviations: ML, Medial-lateral; AP, Anterior-posterior.

Mobile device and NeuroCom systems were equally capable of differentiating postural stability across populations. Postural instability for the PD group quantified by P2P, NPL, logRMS, and 95% Ellipse Area in ML and AP directions was significantly greater compared to controls during SOT5 (sway-absent) and SOT6 (sway-sway) with both the mobile device (SOT5 and SOT6: P<0.02) and NeuroCom systems (SOT5 and SOT6: P<0.05). Figure 1B depicts differences in 95% Ellipse Area across populations during the six SOT conditions.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to determine concurrent validity of measures of accelerometry using the embedded inertial sensors within a mobile device with the NeuroCom force platform to accurately measure postural stability in individuals with PD compared to age-matched controls. The primary results indicate: 1) measures of COM acceleration (i.e. P2P, NPL, logRMS, and 95% Ellipse Area) computed from the mobile device and NeuroCom force platform were significantly correlated across sway directions, balance conditions, and populations, 2) the test-retest reliability of the mobile device measures was equal or superior to the NeuroCom across SOT conditions, and 3) COM acceleration was superior to the Equilibrium Score in detecting differences in postural stability between individuals with PD and their healthy, age-matched counterparts (Fig. 1).

The Equilibrium Scores failed to detect differences in postural instability between individuals with PD and healthy, age-matched controls, in any of the six balance conditions of the SOT. However, COM acceleration was sensitive in detecting differences between populations under the most difficult conditions, SOT5 (sway-absent) and SOT6 (sway-sway). Specifically, in SOT5, somatosensory information was inaccurate and vision was unavailable; whereas in SOT6, both somatosensory and visual information were inaccurate. Although a number of studies have detected postural instability in individuals with PD using Equilibrium Scores during SOT5 and/or SOT611,13,22,43,44, in our cohort of individuals with PD, measures incorporating COM acceleration were the only ones sensitive in detecting postural stability deficits. The majority of individuals in our study had mild PD, with median disease duration of 4.5 years and an average Hoehn and Yahr Stage of 2.4. Individuals who present at Hoehn and Yahr Stage 2 are characterized as having bilateral symptoms with no balance impairment, as defined by the pull test45. Therefore, it is not surprising that the Equilibrium Score, which uses only the two most extreme AP positional data points of postural stability, did not discriminate across populations.

The inverted pendulum model incorporating COP and COM displacements, which are proportional to COM acceleration, provides increased sensitivity into the assessment of postural stability than COP and COM used in isolation46,47. Since COM acceleration is not directly measureable from the force platform, a critical finding in the current study was demonstrating validity of the mobile device metrics to quantify postural stability during the SOT. The Bland-Altman analysis assessed the ability of the mobile device to accurately quantify the trajectories of COM acceleration within a trial as quantified by P2P, NPL, logRMS, and 95% Ellipse Area. The SOT1 had the smallest spread of differences between the 95% confidence intervals across outcome measures, whereas SOT5 and SOT6 had the largest spread between the 95% confidence intervals (Table 3). Overall, the mobile device consistently provided a measure similar to the NeuroCom system across a range of balance task difficulties.

Additionally, test-retest reliability of mobile device measures was shown to be equal or superior to the NeuroCom system across SOT conditions, indicating reproducibility and precision of mobile device outcome measures for each trial within the SOT conditions. The test-retest results are consistent with previous findings from Whitney and colleagues48, showing good to excellent test-retest reliability of accelerometry measures comparable to those using the NeuroCom system. However, while Whitney and colleagues compared COM measures using a custom accelerometer system to COP measures using the NeuroCom force platform, the current study incorporated the inverted pendulum model, allowing for the direct comparison of COM measures across systems, thereby building upon the work of Whitney and colleagues. All outcome measures in the current study exhibited ICC values ranging from good to excellent across all subjects and SOT conditions, and specifically, the mobile device exhibited excellent reliability 79% of the time compared to the NeuroCom, which demonstrated excellent reliability 60% of the time. Our findings support use of a biomechanical balance assessment that provides a valid and reliable measure of postural instability to monitor and manage disease progression. Results from the study justify use of ML and AP COM acceleration in individuals with PD and in a healthy population to better characterize postural stability under demanding sensory conditions.

When analyzing measures of COM acceleration, individuals with PD maintained postural stability similar to controls when somatosensory and vestibular information were available with or without access to vision (SOT1-SOT3). Further, when somatosensory information was incongruent, but vision and vestibular information were available, individuals with PD maintained postural stability (SOT4) comparable to healthy controls. However, when vision was unavailable or incongruent and somatosensory information was incongruent (SOT5 and SOT6), individuals with PD had decreased postural stability compared to controls. These results do not necessarily indicate that their vestibular system is impaired49, but rather, suggest that individuals with PD may be over-reliant on visual feedback to maintain postural stability. This visual dependence is consistent with neuroanatomical evidence of somatosensory impairment and points to largely intact visual inputs in PD. Projections from the dorsal visual stream to the basal ganglia are minor compared to the visual afferents to the cerebellum and posterior parietal circuits50; thus, visuomotor integration may be largely spared by the disease, and could explain the increased reliance on vision by PD6,51. Increased reliance on vision may be an adaptive strategy to compensate for impaired somatosensory feedback51; thus, postural instability can often be improved by utilizing external visual cues52–55. Additionally, individuals with PD may have difficulty re-weighting sensory information when one or more sensory modalities become unreliable or unavailable56. When examining postural responses of individuals with PD after visual stimuli generated by discrete lateral displacements of a moveable room in which subjects stand in the upright position, investigators reported normal sway with eyes open or closed but abnormally large motor responses to room movement, which did not attenuate with stimulus repetition10. Therefore, it is plausible that individuals with PD may have experienced difficulty re-weighting sensory input from visual and somatosensory components, thus becoming unstable.

The established mobile device metrics quantifying COM acceleration provide insight into the error signal that the postural control system is experiencing during balance conditions involving deprivation or inaccuracy of visual, vestibular, and somatosensory information. The error signal may vary based on each individual’s capability of prioritizing sensory inputs to maintain equilibrium, which may aid clinicians in determining the severity of deficits in central processing capacity. Balance deficits in individuals with PD during SOT5 and SOT6 provide insight into the integration of sensory systems associated with postural stability, and were only detected using metrics quantifying the mobile device’s trajectory but were lost using less sensitive measures of maximum AP displacement quantified by the NeuroCom system. Use of the proposed mobile device and application installed on a handheld mobile device may provide an accurate, easy to use, and cost-effective platform to generate quantitative scores by which clinicians and researchers may identify individuals with postural instability over time and across providers.

LIMITATIONS

Modeling postural stability as an inverted pendulum model assumes a rigid structure above the ankle joints; however, the human body is a multi-segmented structure capable of moving at all joints. Yet, because individuals with PD display significantly larger hip feedback gains with significantly smaller hip joint torques57, we felt confident that overall postural stability resembled the inverted pendulum in response to perturbations. In applying the inverted pendulum model in healthy older adults, movement at joints other than the ankles, such as the hips, has been shown to be present during unperturbed58,59 and perturbed60,61 balance conditions; however, Gage and colleagues provided a detailed kinematic analysis of postural stability using a laboratory 3D motion capture system supporting the inverted pendulum model due to each body segment’s COM synchronized to the movement of whole body COM62.

CONCLUSIONS

Utilizing acceleration measures from ML and AP planes increased sensitivity to discriminate between healthy and PD populations and provides a method capable of reliably detecting changes in postural stability across a range of conditions. Enhanced sensitivity of measurement provides utility in monitoring disease progression, response to treatment, potential for falling and methods of facilitating clinical hand-offs between providers.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Mike Buss, who led the development of the Cleveland Clinic Balance App, Mark Gustetic and David Schindler for assistance in data processing, and Anson Rosenfeldt for assistance in clinical testing.

Funding: This study was supported by R01NS073717-01 and the Farmer Foundation.

Abbreviations

- AP

anterior-posterior

- COP

center of pressure

- COM

center of mass

- ML

medial-lateral

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- SOT

Sensory Organization Test

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have authored intellectual property related to the methods described in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Bloem BR, Hausdorff JM, Visser JE, Giladi N. Falls and freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease: a review of two interconnected, episodic phenomena. Mov Disord. 2004 Aug;19(8):871–884. doi: 10.1002/mds.20115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balash Y, Peretz C, Leibovich G, Herman T, Hausdorff JM, Giladi N. Falls in outpatients with Parkinson's disease: frequency, impact and identifying factors. Journal of neurology. 2005 Nov;252(11):1310–1315. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0855-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giladi N, Horak FB, Hausdorff JM. Classification of gait disturbances: distinguishing between continuous and episodic changes. Mov Disord. 2013 Sep 15;28(11):1469–1473. doi: 10.1002/mds.25672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson JM, Watson S, Halliday GM, Heinemann T, Gerlach M. Relationships between various behavioural abnormalities and nigrostriatal dopamine depletion in the unilateral 6-OHDA-lesioned rat. Behav Brain Res. 2003 Feb 17;139(1–2):105–113. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romero DH, Stelmach GE. Changes in postural control with aging and Parkinson's disease. IEEE engineering in medicine and biology magazine : the quarterly magazine of the Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society. 2003 Mar-Apr;22(2):27–31. doi: 10.1109/memb.2003.1195692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konczak J, Corcos DM, Horak F, et al. Proprioception and motor control in Parkinson's disease. Journal of motor behavior. 2009 Nov;41(6):543–552. doi: 10.3200/35-09-002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Visser JE, Bloem BR. Role of the basal ganglia in balance control. Neural plasticity. 2005;12(2–3):161–174. doi: 10.1155/NP.2005.161. discussion 263-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown LA, Cooper SA, Doan JB, et al. Parkinsonian deficits in sensory integration for postural control: temporal response to changes in visual input. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2006 Sep;12(6):376–381. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Nunzio AM, Nardone A, Schieppati M. The control of equilibrium in Parkinson's disease patients: delayed adaptation of balancing strategy to shifts in sensory set during a dynamic task. Brain research bulletin. 2007 Sep 28;74(4):258–270. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bronstein AM, Hood JD, Gresty MA, Panagi C. Visual control of balance in cerebellar and parkinsonian syndromes. Brain. 1990 Jun;113(Pt 3):767–779. doi: 10.1093/brain/113.3.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bronte-Stewart HM, Minn AY, Rodrigues K, Buckley EL, Nashner LM. Postural instability in idiopathic Parkinson's disease: the role of medication and unilateral pallidotomy. Brain. 2002 Sep;125(Pt 9):2100–2114. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bloem BR, Beckley DJ, van Dijk JG, Zwinderman AH, Remler MP, Roos RA. Influence of dopaminergic medication on automatic postural responses and balance impairment in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 1996 Sep;11(5):509–521. doi: 10.1002/mds.870110506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nallegowda M, Singh U, Handa G, et al. Role of sensory input and muscle strength in maintenance of balance, gait, and posture in Parkinson's disease: a pilot study. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation / Association of Academic Physiatrists. 2004 Dec;83(12):898–908. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000146505.18244.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blaszczyk JW, Orawiec R, Duda-Klodowska D, Opala G. Assessment of postural instability in patients with Parkinson's disease. Experimental brain research. Experimentelle Hirnforschung. Experimentation cerebrale. 2007 Oct;183(1):107–114. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1024-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bloem B, Visser J, Allum J. Posturography. In: Hallet M, editor. Movement disorders - handbook of clinical neurophysiology. Elsevier; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Błaszczyk JW. The use of force-plate posturography in the assessment of postural instability. Gait and Posture. 2016;44:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monsell EM, Furman JM, Herdman SJ, Konrad HR, Shepard NT. Computerized dynamic platform posturography. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 1997 Oct;117(4):394–398. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(97)70132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nashner LM, Peters JF. Dynamic posturography in the diagnosis and management of dizziness and balance disorders. Neurol Clin. 1990 May;8(2):331–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toole T, Hirsch MA, Forkink A, Lehman DA, Maitland CG. The effects of a balance and strength training program on equilibrium in Parkinsonism: A preliminary study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2000;14(3):165–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirsch MA, Toole T, Maitland CG, Rider RA. The effects of balance training and high-intensity resistance training on persons with idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2003 Aug;84(8):1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nocera J, Horvat M, Ray CT. Effects of home-based exercise on postural control and sensory organization in individuals with Parkinson disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009 Dec;15(10):742–745. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vervoort G, Nackaerts E, Mohammadi F, et al. Which Aspects of Postural Control Differentiate between Patients with Parkinson's Disease with and without Freezing of Gait? Parkinson's disease. 2013;2013:971480. doi: 10.1155/2013/971480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winter DA, Prince F, Frank JS, Powell C, Zabjek KF. Unified theory regarding A/P and M/L balance in quiet stance. J Neurophysiol. 1996 Jun;75(6):2334–2343. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.6.2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winter DA. Human balance and posture control during standing and walking. Gait and Posture. 1995;3:193–214. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaudhry H, Findley T, Quigley KS, et al. Measures of postural stability. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2004 Sep;41(5):713–720. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2003.09.0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaudhry H, Findley T, Quigley KS, et al. Postural stability index is a more valid measure of stability than equilibrium score. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005 Jul-Aug;42(4):547–556. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2004.08.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winter DA, Patla AE, Prince F, Ishac M, Gielo-Perczak K. Stiffness control of balance in quiet standing. J Neurophysiol. 1998 Sep;80(3):1211–1221. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.3.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mancini M, Horak FB, Zampieri C, Carlson-Kuhta P, Nutt JG, Chiari L. Trunk accelerometry reveals postural instability in untreated Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011 Aug;17(7):557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hufschmidt A, Dichgans J, Mauritz KH, Hufschmidt M. Some methods and parameters of body sway quantification and their neurological applications. Archiv fur Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten. 1980;228(2):135–150. doi: 10.1007/BF00365601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murray MP, Seireg A, Scholz RC. Center of gravity, center of pressure, and supportive forces during human activities. Journal of applied physiology. 1967 Dec;23(6):831–838. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1967.23.6.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masani K, Vette AH, Kouzaki M, Kanehisa H, Fukunaga T, Popovic MR. Larger center of pressure minus center of gravity in the elderly induces larger body acceleration during quiet standing. Neuroscience letters. 2007 Jul 18;422(3):202–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berger L, Chuzel M, Buisson G, Rougier P. Undisturbed upright stance control in the elderly: Part 1. Age-related changes in undisturbed upright stance control. Journal of motor behavior. 2005 Sep;37(5):348–358. doi: 10.3200/JMBR.37.5.348-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corriveau H, Hebert R, Raiche M, Dubois MF, Prince F. Postural stability in the elderly: empirical confirmation of a theoretical model. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics. 2004 Sep-Oct;39(2):163–177. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caron O, Faure B, Breniere Y. Estimating the centre of gravity of the body on the basis of the centre of pressure in standing posture. Journal of biomechanics. 1997 Nov-Dec;30(11–12):1169–1171. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)00094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimba T. An estimation of center of gravity from force platform data. Journal of biomechanics. 1984;17(1):53–60. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(84)90080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levine O, Mizrahi J. An iterative model for the estimation of the trajectory of the center of gravity from bilateral reactive force measurements in standing sway. Gait & posture. 1996;4:89–99. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benda B, Riley P, Krebs D. Biomechanical relationship between center of gravity and center of pressure during standing. IEEE Trans Rehab. Eng. 1994;2:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ozinga SJ, Alberts JL. Quantification of postural stability in older adults using mobile technology. Exp Brain Res. 2014 Dec;232(12):3861–3872. doi: 10.1007/s00221-014-4069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alberts JL, Hirsch JR, Koop MM, et al. Using Accelerometer and Gyroscopic Measures to Quantify Postural Stability. Journal of athletic training. 2015 Apr 6; doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.2.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozinga SJ, Machado AG, Miller Koop M, Rosenfeldt AB, Alberts JL. Objective assessment of postural stability in Parkinson's disease using mobile technology. Mov Disord. 2015 Aug;30(9):1214–1221. doi: 10.1002/mds.26214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alberts JL, Thota A, Hirsch J, et al. Quantification of the Balance Error Scoring System with Mobile Technology. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2015 Oct;47(10):2233–2240. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rougier P, Farenc I, Berger L. Modifying the gain of the visual feedback affects undisturbed upright stance control. Clinical biomechanics. 2004 Oct;19(8):858–867. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waterston JA, Hawken MB, Tanyeri S, Jantti P, Kennard C. Influence of sensory manipulation on postural control in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993 Dec;56(12):1276–1281. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.12.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colnat-Coulbois S, Gauchard GC, Maillard L, et al. Management of postural sensory conflict and dynamic balance control in late-stage Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience. 2011 Oct 13;193:363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967 May;17(5):427–442. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Geursen JB, Altena D, Massen CH, Verduin M. A model of the standing man for the description of his dynamic behaviour. Agressologie: revue internationale de physiobiologie et de pharmacologie appliquees aux effets de l'agression. 1976;17(SPECNO):63–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hebert R, Spiegelhalter DJ, Brayne C. Setting the minimal metrically detectable change on disability rating scales. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1997 Dec;78(12):1305–1308. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whitney SL, Roche JL, Marchetti GF, et al. A comparison of accelerometry and center of pressure measures during computerized dynamic posturography: a measure of balance. Gait & posture. 2011 Apr;33(4):594–599. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pastor MA, Day BL, Marsden CD. Vestibular induced postural responses in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 1993 Oct;116(Pt 5):1177–1190. doi: 10.1093/brain/116.5.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glickstein M. How are visual areas of the brain connected to motor areas for the sensory guidance of movement? Trends Neurosci. 2000 Dec;23(12):613–617. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01681-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Demirci M, Grill S, McShane L, Hallett M. A mismatch between kinesthetic and visual perception in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 1997 Jun;41(6):781–788. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jackson SR, Jackson GM, Harrison J, Henderson L, Kennard C. The internal control of action and Parkinson's disease: a kinematic analysis of visually-guided and memory-guided prehension movements. Experimental brain research. Experimentelle Hirnforschung. Experimentation cerebrale. 1995;105(1):147–162. doi: 10.1007/BF00242190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Azulay JP, Mesure S, Amblard B, Blin O, Sangla I, Pouget J. Visual control of locomotion in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 1999 Jan;122(Pt 1):111–120. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Su KJ, Hwang WJ, Wu CY, Fang JJ, Leong IF, Ma HI. Increasing speed to improve arm movement and standing postural control in Parkinson's disease patients when catching virtual moving balls. Gait & posture. 2014 Jan;39(1):65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McAuley JH, Daly PM, Curtis CR. A preliminary investigation of a novel design of visual cue glasses that aid gait in Parkinson's disease. Clinical rehabilitation. 2009 Aug;23(8):687–695. doi: 10.1177/0269215509104170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schoneburg B, Mancini M, Horak F, Nutt JG. Framework for understanding balance dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2013 Sep 15;28(11):1474–1482. doi: 10.1002/mds.25613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim S, Horak FB, Carlson-Kuhta P, Park S. Postural feedback scaling deficits in Parkinson's disease. J Neurophysiol. 2009 Nov;102(5):2910–2920. doi: 10.1152/jn.00206.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Day BL, Steiger MJ, Thompson PD, Marsden CD. Effect of vision and stance width on human body motion when standing: implications for afferent control of lateral sway. J Physiol. 1993 Sep;469:479–499. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Accornero N, Capozza M, Rinalduzzi S, Manfredi GW. Clinical multisegmental posturography: age-related changes in stance control. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1997 Jun;105(3):213–219. doi: 10.1016/s0924-980x(97)96567-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Horak FB, Nashner LM. Central programming of postural movements: adaptation to altered support-surface configurations. J Neurophysiol. 1986 Jun;55(6):1369–1381. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.55.6.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bloem BR, Allum JH, Carpenter MG, Honegger F. Is lower leg proprioception essential for triggering human automatic postural responses? Experimental brain research. Experimentelle Hirnforschung. Experimentation cerebrale. 2000 Feb;130(3):375–391. doi: 10.1007/s002219900259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gage WH, Winter DA, Frank JS, Adkin AL. Kinematic and kinetic validity of the inverted pendulum model in quiet standing. Gait & posture. 2004 Apr;19(2):124–132. doi: 10.1016/S0966-6362(03)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]