Abstract

Background

Migraine is a debilitating neurological disorder where trigeminovascular activation plays a key role. We have previously reported that local application of Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) onto the dura mater caused activation in rat trigeminal ganglion (TG) which was abolished by a systemic administration of kynurenic acid (KYNA) derivate (SZR72). Here, we hypothesize that this activation may extend to the trigeminal complex in the brainstem and is attenuated by treatment with SZR72.

Methods

Activation in the trigeminal nucleus caudalis (TNC) and the trigeminal tract (Sp5) was achieved by application of CFA onto the dural parietal surface. SZR72 was given intraperitoneally (i.p.), one dose prior CFA deposition and repeatedly daily for 7 days. Immunohistochemical studies were performed for mapping glutamate, c-fos, PACAP, substance P, IL-6, IL-1β and TNFα in the TNC/Sp5 and other regions of the brainstem and at the C1-C2 regions of the spinal cord.

Results

We found that CFA increased c-fos and glutamate immunoreactivity in TNC and C1-C2 neurons. This effect was mitigated by SZR72. PACAP positive fibers were detected in the fasciculus cuneatus and gracilis. Substance P, TNFα, IL-6 and IL-1β immunopositivity were detected in fibers of Sp5 and neither of these molecules showed any change in immunoreactivity following CFA administration.

Conclusion

This is the first study demonstrating that dural application of CFA increases the expression of c-fos and glutamate in TNC neurons. Treatment with the KYNA analogue prevented this expression.

Keywords: TNC, CFA, c-fos, Glutamate, KYNA analogue

Background

Migraine is among the leading causes of disability, having a huge impact on public health [1, 2]. Studies show that each year 2.5% of episodic migraine disease converts into chronic migraine [3] which appears as a distinct entity in the classification of the International Headache Society. Although numerous studies have been performed aiming to understand the pathophysiology of migraine and the chronification process, however this is still enigmatic. The trigeminal system plays a pivotal role in the genesis of migraine headache [4, 5]. The pseudo-unipolar nerve cells of the trigeminal ganglion (TG), provide sensory innervation of cranial structures and meningeal vessels while central projections terminate in trigeminal nucleus caudalis (TNC) and C1-C2 region of the spinal cord [6]. This trigeminovascular complex transmits pain signals from meningeal and cerebral vessels to the brainstem and second-order neurons terminate in the thalamus and cortical regions, where further transmission and modulation of pain sensation occur [6–8]. Following continous and repeated stimulation peripheral and central sensitisation of the primary-neurons might occur, leading to reduced activation treshold, represented clinically by allodynia [4, 9, 10].

Previous studies have shown that application of inflammatory substances on the dura mater causes central sensitisation of the neurons in TNC and at C1-C2 levels of the spinal cord [6, 10, 11]. Recent studies have demonstrated lower levels of kynurenic acid (KYNA) in serum of patients suffering from chronic migraine compared to controls [12, 13]. KYNA could be a new therapeutic line in migraine chronification, but KYNA can poorly cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB), while newer KYNA analogues have better BBB penetration characteristics [14, 15]. We have recently developed an animal model for long-term trigeminovascular activation following application of Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) onto the surface of the dura mater [16]. We found activation of satellite glial cells and neurons of the trigeminal ganglion (IL-1, pERK1/2) that were abolished by the KYNA-analogue, SZR72 [17] possibly acting on peripheral and central gluatamate receptors (30). The present study was designed to examine whether dural application of CFA can cause activation of the central part of the trigeminalvascular system,: the TNC and C1-C2 regions of the spinal cord. We asked the question whether the CFA-induced activation might be mitigated by use of SZR72 intraperitoneally.

Methods

Synthesis of novel KYNA derivative

The KYNA amide reported here was designed in the Pharmaceutical Chemistry and Research Group for Stereochemistry, University of Szeged Hungary. The synthesis procedure has previously been presented [15, 17]. The KYNA analogue (SZR72, N-(2-N,N-dimethylaminoethyl)-4-oxo-1H-quinoline-2-carboxamide hydrochloride) has the following structural properties: the presence of a water-soluble side-chain, the inclusion of a new cationic centre, and side-chain substitution in order to enhance brain penetration [17].

Animals

Adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (220–300 g) (n = 30) were used. The animals were raised and maintained under standard laboratory conditions with free access to food and tap water. The study followed the guidelines of the European Communities Council (86/609/ECC) and was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Faculty of Medicine, University of Szeged, Hungary (I-74-12/2012).

Treatments

The animals were divided into 7 groups: (i) CFA + saline application to the dura, (ii) saline application to the dura, (iii) pre-treatment KYNA (KYNA analog, 300 mg/kg body weight dissolved in 1 ml saline, 1 h before CFA administration), (iv) pre-treatment saline (saline, 1, ml 1 h before CFA), (v) repeated treatment (KYNA analog, 300 mg/kg body weight dissolved in 1 ml saline every 12 h, for 7 days), (vi) repeated saline (saline 1 ml every 12 h, for 7 days) and (vii) fresh (intact, control rats) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Groups of animals

| Group | Dura application | Pre-treatment | Repeated treatment | No. of animals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFA | CFA | - | - | 6 |

| Saline | saline | - | - | 3 |

| CFA + KYNA pre-treatment | CFA | KYNA | - | 6 |

| CFA + saline pre-treatment |

CFA | saline | - | 3 |

| CFA + KYNA repeated | CFA | KYNA | KYNA | 6 |

| CFA + saline repeated | CFA | saline | saline | 3 |

| Fresh, control rats | - | - | - | 3 |

Operation

The operation has been described in details earlier [16, 17]. Briefly, animals were deeply anesthetized and a handheld drill was used to remove a 3x3 mm large portion of the parietal bone, cooled by saline irrigation to avoid local healing. The hole was made postero-laterally to the bregma (5 mm), on the left side, care being taken not to penetrate the dura mater. Ten μl of CFA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) or saline was applied on the dural surface, and washed with saline after 20 min.

Both treated and control animals were transcardially fixation-perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in buffer after 7 days. As fresh control, intact rats were used.

Tissue analysis

After the perfusion-fixation the TNC brainstem region and C1-C2 region of the spinal cord were removed (−1, +5 mm from the obex). Specimens were frozen on dry ice, stored at −80 °C and prepeared for immunohistochemistry. To encompass TNC, sections were collected from 6 different levels from the central canal was visualized to the C1 segment of the spinal cord. (100–120 sections in total per animal).

Immunohistochemistry and microscopic analysis

Immunohistochemical staining was performed to demonstrate the localization of glutamate, c-fos, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, substance P and PACAP. Details of the primary and secondary antibodies are given in Table 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Details of primary antibodies used for immunohistochemistry

| Name | Product code | Host | Dilution | Company |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti c-fos | PC38 | Rabbit | 1:100 | Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany |

| Anti PACAP-38 | B57–1 | Rabbit | 1:100 | Europroxima, Arnhem, Netherlands |

| Anti Glutamate | G9282 | Mouse | 1:100 | Sigma-Aldrich, St-Luis, MO, USA |

| Anti Glutamate | AB5018 | Rabbit | 1:100 | Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany |

| Anti Substance P | B 45–1 | Rabbit | 1:200 | Europroxima, Arnhem, Netherlands |

| Anti IL-1β | ab 9787 | Rabbit | 1:100 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK |

| Anti IL-6 | ab6672 | Rabbit | 1:200 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK |

| Anti-TNF α | ab66579 | Rabbit | 1:400 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK |

Table 3.

Details of secondary antibodies used for immunohistochemistry

| Conjugate and host | Against | Diluation | Company |

|---|---|---|---|

| FITC (goat) | anti-rabbit | 1:100 | Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA |

| Alexa 488 (goat) | anti-mouse | 1:100 | Invitrogen, CA, USA |

| Alexa 594 (donkey) | anti-rabbit | 1:100 | Jackson Immuno Research, West Baltimor, PA, USA |

The immunohistochemical method and the microscopic analysis have been described earlier [16]. The areas of the brainstem were identified using rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, second edition, 1986). Each procedure was repeated a minimum of three times to validate the results and minimize any experimental errors using the same antibody stock. Negative controls were performed for each set by omitting the primary antibody. One examinator was blinded. Any resulting immunofluorescence would suggest unspecific binding of the secondary antibodies.

Results

Immunohistochemistry

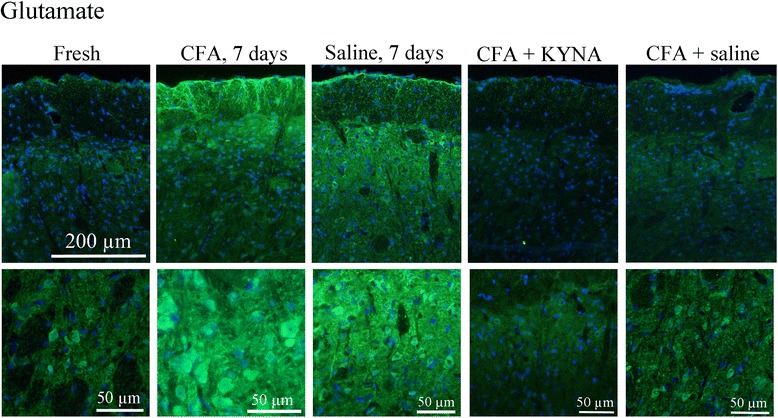

Glutamate

In intact (fresh) animals, glutamate immunoreactivity (GI) was detected in fibers of the trigeminal tract on every level of the TNC (Fig. 1a and b). A few homogeneously stained glial cells could also be found. The staining also displayed some homogenously labelled neurons, especially in TNC in the caudal part of the brainstem.

Fig. 1.

Glutamate immunoreactivity in the TNC. In case of fresh, intact animals a few homogenously stained neurons were detected in the TNC. Following CFA application on the dura a clear increase in staining intensity and amount of glutamate positive cells can be seen. After saline application on the dura a moderate increase was seen compared to fresh, intact animals. I.p. treatment with KYNA derivate abolished the amount of glutamate positive cells following CFA induced activation, whereas i.p saline treatment had no effect on glutamate reactivity in the TNC. “+” represent a light, “++” moderate, “+++” strong increase in immunoreactivity

Application of CFA on the dura (group CFA 7days), similar staining pattern was observed, with an obvious increase in the intensity and amount of glutamate positive neurons in the TNC (Fig. 1). In the gelatinous layer a clearly increased intensity could be seen. With higher magnification, cells with intensely stained cytoplasm were identified in this region (Fig. 1). The aspect is specific to the medial part of the spinal trigeminal nucleus: triangular or multipolar shaped, medium-sized cells with an irregular arrangement. No difference in the fiber staining was noted. In the application of saline group, the same GI pattern was observed (Fig. 1).

In group pretreated with SZR72, the increased expression was abolished. The intensity and number of glutamate immunoreactive cells remained at the level observed in healthy, intact animals. No clear difference could be visualized between pre-treatment and repeated-treatment of KYNA, and no difference was noted in the fibers and glial cells. In the application of saline group, the same GI pattern was observed as in fresh control (Fig. 1).

On the level of the C1-C2 region of the spinal cord GI was found in the anterior and dorsal horns (lamina I, lamina II) and the areas surrounding the central canal. In these areas no difference was found between the different groups (no cells, only fibers). A summary of these results is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of glutamate immunostaining in TNC for different treatment groups

| Group | Neuronal staining | Fiber staining | Glial cell staining |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | -\+ | ++ | -\+ |

| CFA 7d | +++ | ++ | -\+ |

| Saline 7d | + | ++ | -\+ |

| CFA+ SZR72 one dose | -\+ | ++ | -\+ |

| CFA+ SZR72 repeated | -\+ | ++ | -\+ |

| CFA+ saline one dose | +++ | ++ | -\+ |

| CFA + saline repeated | +++ | ++ | -\+ |

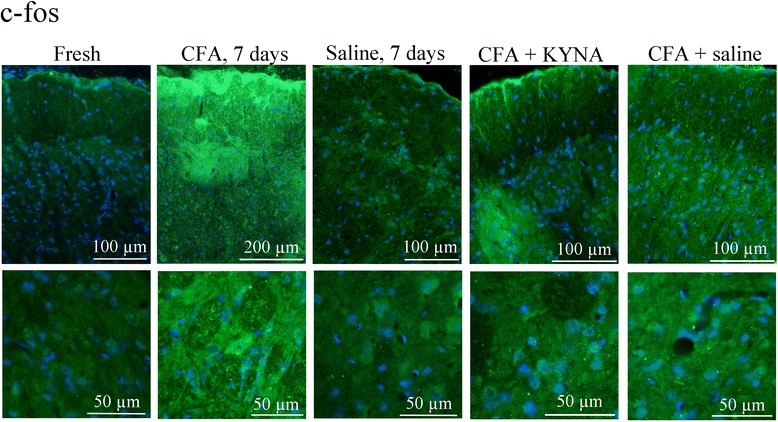

C-fos

In intact (fresh) rats, few c-fos positive neuronal nuclei, but no nucleolei, were observed in the caudal part of the spinal trigeminal nucleus (Sp5C, TNC); these were mainly seen in the gelatinous layer (Fig. 2). No difference could be observed between cranial and caudal levels of the TNC.

Fig. 2.

C-fos immunoreactivity in the TNC. In case of fresh, intact rats few c-fos positive neuronal nuclei but no nucleolei could be observed. After appilcation of CFA on t he dura mater large amount of c-fos positive nuclei was detected. Saline application on the dura mater caused no increase in immunoreactivity compared to fresh, intact control. I.p. treatment with KYNA derivate was able to abolish the activation caused by application of CFA on the dura. I.p. saline had no such effect. “+” represents a light, “++” moderate, “+++” strong increase in immunoreactivity

After application of CFA onto the dura mater, an increase in the number of c-fos positve nuclei could be detected, especially in the caudal areas of the TNC, close to the spinal cord (Fig. 2). No increased immunoreactivity was visualised using saline application on the dura (Fig. 2).

Administration of SZR72 reduced the CFA-induced activation in neuronal nuclei at every level of the TNC, similar to the low expression seen in fresh rats. No significant difference could be shown between the pre-treatment and repeated-treatment of SZR72. After treatment with saline, we noted no increase in the c-fos expression, showing that treatment with saline did not have effect on the CFA-induced TNC activation (Fig. 2i).

The results of the c-fos immunostaining are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of c-fos immunostaining in TNC for different treatment groups

| Group | Neuronal staining |

|---|---|

| Fresh | -\+ |

| CFA 7d | +++ |

| Saline 7d | + |

| CFA + SZR72 one dose | + |

| CFA+ SZR72 repeated | + |

| CFA + saline | +++ |

| CFA + saline repeated | +++ |

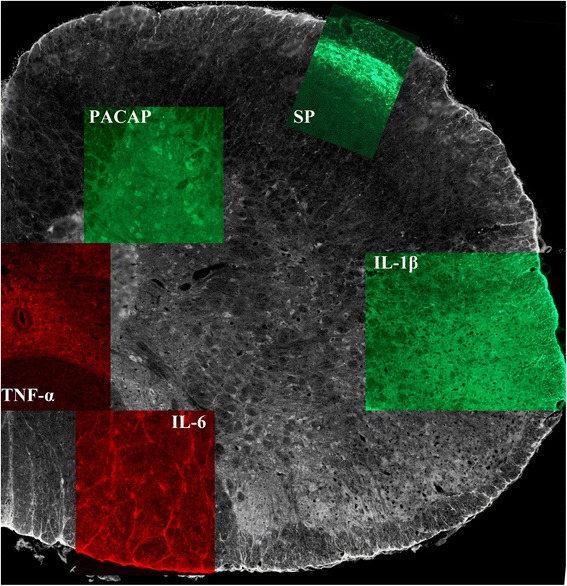

PACAP

PACAP immunoreactivity was found in fibers of the trigeminal tract, both in healthy and CFA inflammation-induced animals. PACAP immunoreactivity was found in the brainstem, in the spinal cord, especially in the large neurons of the anterior horn, in the dorsal horn, around the central canal and the ependymal cells of the central canal. PACAP immunoreactive fibers were observed in almost every tract in the spinal cord (dorsal corticocerebellar tract, spinocerebellar tracts, medial longitudinal tract, pyramidal tract). In these territories no difference was detected between different groups (SZR 72 had no effect).

Substance P

Substance P immunoreactivity was limited to nerve fibers of the spinal trigeminal tract and to the gelatinous layer (Fig. 3). Some positive fibers, surrounding the SP5C were also visualized. No difference was noted between different levels of TNC and a slight increased intensity of the fiber staining could be detected after CFA application, but not in the gelatinous layer.

Fig. 3.

Summary of PACAP, Substance P, TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β immunoreactivity in the C1-C2 region of the spinal cord. PACAP immunoreactivity was detected in the dorsal horn and in almost every tract of the spinal cord. Substance P immunoreactvity was limited to the fibers of the spinal trigeminal tract. TNF-α immunopositivity was mainy seen in the small cells surrounding the central canal. IL-6 immunopositivity was shown in the large neurons of the anterior horn and in nerve endings of these cells. IL-1 β immunopositvity was mainy seen in different tracts of the spinal cord, few positive cells, with granular intracytoplasmatic staining were also detected

TNF-α

TNF-immunoreactivity was found in the trigeminal tract, with dense fiber staining in the spinal trigeminal tract, but no glial or neuronal staining was detected at either level of the TNC. In the spinal cord few, small sized neurons were detected, especially around the central canal (Fig. 3). Some TNF- α positive fibers were identified in other tracts of the spinal cord (dorsal cortico-cerebellar tract, spino-cerebellar tracts, medial longitudinal tract, pyramidal tract). No difference was noted between the groups.

IL-6

IL-6 positivity was detected in the fibers and in the cytoplasm of some glial cells, showing a homogenous staining in the spinal trigeminal tract. Some homogeniously stained neurons were detected in the TNC. In the spinal cord, some positive neurons could be seen in the caudal part of the spinal trigeminal nucleus, in the large neurons of the anterior horn, in the dorsal horn and the ependymal cells of the central canal (Fig. 3). Intensely positive fibers were visualised in the cuneate and gracile fasciculus. After application of CFA, similar staining patterns as for the non-CFA groups were found.

IL-1β

IL-1β immunohistochemistry showed the same staining pattern as for IL6 and TNFα, with no change after CFA induced activation (Fig. 3). IL-1β immunoreactivity showed a granular cytoplasmatic stainig, previously described in the TG (14).

Discussion

In this study we present the immunostaining pattern of several neuronal messengers and cytokines in the TNC/C1-C2 spinal region (11) that are indicated in migraine pathophysiology. CFA is a potent immun- potentiator, used in various peripheral pain model. (Spinal distribution of c-Fos activated neurons expressing enkephalin in acute and chronic pain models, 1st manu) We asked the question whether application of CFA on a defined area of the dura mater could cause activation of second-order neurons in the TNC and whether this activation can be mitigated by systemic adminstration of a KYNA analogue.

Gluatamate, the major excitatory neurotransmitter in CNS plays a key role in the trigeminovascular activation, especially in central sensitisation via activation of NMDA receptors [18, 19]. Glutamate appears to be involved in nociception since glutamate is expressed in the trigeminal ganglion and other sensory ganglia [20, 21]. Glutamate can be released from neurons following nociceptive stimuli putatively acting on satellite glial cells (SGC) [22] but is also expressed in the sensory Aδ – fibers (19).

The kynurenine pathway, the major route of tryptophan metabolism to nicotinamide, has an important role in several diseases of the CNS [23–25]. Kynurenic acid (KYNA) is one of the neuroactive metabolits of the kynurenine pathway in human astrocytes [26] protecting against neuronal cell-death [27]. KYNA in low concentration enhances AMPA receptor activity [28, 29], while in high concentrations blocks the NR1 subunit of the NMDA receptors [19, 30]. NMDA receptor consists of NR1, NR2 and NR3 subunits, where NR1 subunit has a glycine- binding domain. Glycine is essential for the functioning of the NMDA receptor and KYNA acts as an antagonist on the gylcine-binding site (NR1) (18). High level of KYNA might have a neuroprotective effect and could act on glutamate receptors, exerting an inhibitory effect on glutamate release [23].

Here we asked the question whether the KYNA analogue might act on the fibers and cells in the TNC/C1-C2. Previous work has shown a positive effect in TG following CFA injection into the temporomandibular joint [31] while SZR 72 decreased c-fos activation in the TNC in nitroglycerin induced trigeminal activation [32]. We have reported that one dose of SZR 72 is able to reduce dura mater applied CFA induced activation in the TG [16]. C-fos immunoreactivity is a widely used marker of neuronal activity in the TNC [33, 34]. In the present study we report increased c-fos immunoreactivity following dura mater application of CFA as a sign of neuronal activity of TNC neurons. This effect is attenuated by SZR72. Glutamate activation as a sign of central sensitization can be observed in the second-order neurons after use of CFA, this effect that is also mitigated by the KYNA analogue. Surprisingly repeated-treatment of SZR 72 was not seen to be more effective than pre-treatment with one dose prior CFA application neither in the TG [16] nor in the TNC. Therefore we postulate that early KYNA derivate intervention can block the development of central sensitization, whereas late, repeated treatment might not be able to further moderate mechanisms of central sensitization. Consequently, we assume that the action of the KYNA analogue seems to be exerted on the periphery that is conveyed to neurons of TNC, but an effect on central mechanisms cannot be surely excluded. Further studies are needed to elucidate the possible site of actions of the KYNA derivate.

In this study we examine a fair number of molecules suggested to play a role in migraine. Among these CGRP and PACAP 38 (PACAP) is currently of particular interest. CGRP plays an important role in migraine pathophysiology and localization of CGRP and its receptors (CLR and RAMP1) has already been described in TNC and C1 region of the spinal cord [35, 36]. PACAP is a neuromodulator that has some common actions with CGRP, sharing the same receptors RAMP1 subunit [37]. PACAP might play a role in migraine having various neurobiological functions such as inhibitory effect on neurogenic inflammation [38]. PACAP has shown to be involved in trigeminovascular activation as PACAP-38 infusion caused headache in healthy volunteers [39] and PACAP-38-like immunoreactivity has proved to be altered in ictal compared to interictal phase of migraine and in cluster headache [40, 41]. It is suggested that the effect of PACAP is biphasic: lower concentration increasing, higher concentration inhibiting the NMDA receptor activation [42]. We have found PACAP positive but no change in TNC and C1-C2.

In addition, we examined several other molecules putatively involved in migraine pathophysiology: SP, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α which have all been shown to be associated with activation of the trigeminovascular system [43–46]. While we could document their presesnce in the TNC and C1-C2 of the spinal cord, we did not observe a difference in expression between saline vehicle or CFA administration.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we report activation in neurons and fibers of TNC and C1-C2 following application of CFA on the dura mater that was mitigated by SZR 72. To our knowledge this is the first study that presents the cellular distribution of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL- 1β and TNF-α) in the TNC and in the C1-C2 region of the spinal cord. This might represent a further step in understanding the functional neuroanatomy of the trigeminal pathway. We found increased c-fos and glutamate immunoreactivity in the TNC following application of CFA on the dura mater that was abolished by the KYNA derivate. Further studies are needed to explore the possible mechanisms involved, which could result in a new therapeutic line in treatment of migraine.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Swedish Medical Research Council (5889), and the Hungarian Brain Research Programme (NAP, Grant No. KTIA_13_NAP-A-III/9.); by EUROHEADPAIN (FP7-Health 2013-Innovation; Grant No.602633), by the GINOP-2.3.2–15–2016–00034 grant and by the MTA-SZTE Neuroscience Research Group of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and the University of Szeged.

Authors’ contribution

ML, KW, JTajti, JToldi LV, LE designed the study. FF synthesized the kynurenic acid derivate. ML and KW performed all the experiments. ML, KW, J Tajti and LE analyzed the data. KW, J Tajti, LV and LE supervised al aspects of the project and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

M. Lukács, Phone: +36 62 54 5351, Email: lukacs_melici@yahoo.com, Email: lukacs.melinda@med.u-szeged.hu

K. Warfvinge, Email: karin.warfvinge@med.lu.se

J. Tajti, Email: tajti.janos@med.u-szeged.hu

F. Fülöp, Email: fulop@pharm.u-szeged.hu

J. Toldi, Email: toldi@bio.u-szeged.hu

L. Vécsei, Email: vecsei.laszlo@med.u-szeged.hu

L. Edvinsson, Email: lars.edvinsson@med.lu.se

References

- 1.Steiner TJ, Birbeck GL, Jensen RH, Katsarava Z, Stovner LJ, Martelletti P. Headache disorders are third cause of disability worldwide. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:58. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0544-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global (2015) regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 386(9995):743–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Manack AN, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Chronic migraine: epidemiology and disease burden. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15(1):70–78. doi: 10.1007/s11916-010-0157-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moskowitz MA. Defining a pathway to discovery from bench to bedside: the trigeminovascular system and sensitization. Headache. 2008;48(5):688–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oshinsky ML, Luo J. Neurochemistry of trigeminal activation in an animal model of migraine. Headache. 2006;46(Suppl 1):S39–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edvinsson L. Tracing neural connections to pain pathways with relevance to primary headaches. Cephalalgia. 2011;31(6):737–747. doi: 10.1177/0333102411398152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Broman J, Zhang M, Edvinsson L. Brainstem and thalamic projections from a craniovascular sensory nervous centre in the rostral cervical spinal dorsal horn of rats. Cephalalgia. 2009;29(9):935–948. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noseda R, Burstein R, (2013) Migraine pathophysiology: anatomy of the trigeminovascular pathway and associated neurological symptoms, CSD, sensitization and modulation of pain. Pain 154(Suppl1):1–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Goadsby PJ. Migraine, allodynia, sensitisation and all of that. Eur Neurol. 2005;53(Suppl 1):10–16. doi: 10.1159/000085060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burstein R, Jakubowski M. Analgesic triptan action in an animal model of intracranial pain: a race against the development of central sensitization. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(1):27–36. doi: 10.1002/ana.10785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartsch T, Goadsby PJ. Increased responses in trigeminocervical nociceptive neurons to cervical input after stimulation of the dura mater. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 8):1801–1813. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curto M, Lionetto L, Negro A, Capi M, Fazio F, Giamberardino MA, Simmaco M, Nicoletti F, Martelletti P. Altered kynurenine pathway metabolites in serum of chronic migraine patients. J Headache Pain. 2015;17(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0638-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curto M, Lionetto L, Negro A, Capi M, Perugino F, Fazio F, Giamberardino MA, Simmaco M, Nicoletti F, Martelletti P. Altered serum levels of kynurenine metabolites in patients affected by cluster headache. J Headache Pain. 2015;17:27. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0620-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukui S, Schwarcz R, Rapoport SI, Takada Y, Smith QR. Blood–brain barrier transport of kynurenines: implications for brain synthesis and metabolism. J Neurochem. 1991;56(6):2007–2017. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb03460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fulop F, Szatmari I, Toldi J, Vecsei L. Modifications on the carboxylic function of kynurenic acid. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2012;119(2):109–114. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0721-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lukacs M, Haanes KA, Majlath Z, Tajti J, Vecsei L, Warfvinge K, Edvinsson L. Dural administration of inflammatory soup or Complete Freund’s Adjuvant induces activation and inflammatory response in the rat trigeminal ganglion. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:564. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0564-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lukacs M, Warfvinge K, Kruse LS, Tajti J, Fulop F, Toldi J, Vecsei L, Edvinsson L. KYNA analogue SZR72 modifies CFA-induced dural inflammation- regarding expression of pERK1/2 and IL-1beta in the rat trigeminal ganglion. J Headache Pain. 2016;17(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0654-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vieira DS, Naffah-Mazzacoratti Mda G, Zukerman E, Senne Soares CA, Cavalheiro EA, Peres MF. Glutamate levels in cerebrospinal fluid and triptans overuse in chronic migraine. Headache. 2007;47(6):842–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaszaki J, Erces D, Varga G, Szabo A, Vecsei L, Boros M. Kynurenines and intestinal neurotransmission: the role of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2012;119(2):211–223. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0658-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eftekhari S, Salvatore CA, Johansson S, Chen TB, Zeng Z, Edvinsson L. Localization of CGRP, CGRP receptor PACAP and glutamate in trigeminal ganglion Relation to the blood–brain barrier. Brain Res. 1600;2015:93–109. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoyanova I, Dandov A, Lazarov N, Chouchkov C. GABA- and glutamate-immunoreactivity in sensory ganglia of cat: a quantitative analysis. Arch Physiol Biochem. 1998;106(5):362–369. doi: 10.1076/apab.106.5.362.4360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kung LH, Gong K, Adedoyin M, Ng J, Bhargava A, Ohara PT, Jasmin L. Evidence for glutamate as a neuroglial transmitter within sensory ganglia. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vecsei L, Szalardy L, Fulop F, Toldi J. Kynurenines in the CNS: recent advances and new questions. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(1):64–82. doi: 10.1038/nrd3793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vamos E, Pardutz A, Klivenyi P, Toldi J, Vecsei L. The role of kynurenines in disorders of the central nervous system: possibilities for neuroprotection. J Neurol Sci. 2009;283(1–2):21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.02.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curto M, Lionetto L, Fazio F, Mitsikostas DD, Martelletti P. Fathoming the kynurenine pathway in migraine: why understanding the enzymatic cascades is still critically important. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10(4):413–421. doi: 10.1007/s11739-015-1208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guillemin GJ, Kerr SJ, Smythe GA, Smith DG, Kapoor V, Armati PJ, Croitoru J, Brew BJ. Kynurenine pathway metabolism in human astrocytes: a paradox for neuronal protection. J Neurochem. 2001;78(4):842–853. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee DY, Lee KS, Lee HJ, Noh YH, Kim do H, Lee JY, Cho SH, Yoon OJ, Lee WB, Kim KY, Chung YH, Kim SS. Kynurenic acid attenuates MPP(+)-induced dopaminergic neuronal cell death via a Bax-mediated mitochondrial pathway. Eur J Cell Biol. 2008;87(6):389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prescott C, Weeks AM, Staley KJ, Partin KM. Kynurenic acid has a dual action on AMPA receptor responses. Neurosci Lett. 2006;402(1–2):108–112. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rozsa E, Robotka H, Vecsei L, Toldi J. The Janus-face kynurenic acid. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2008;115(8):1087–1091. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kessler M, Terramani T, Lynch G, Baudry M. A glycine site associated with N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptors: characterization and identification of a new class of antagonists. J Neurochem. 1989;52(4):1319–1328. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb01881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Csati A, Edvinsson L, Vecsei L, Toldi J, Fulop F, Tajti J, Warfvinge K. Kynurenic acid modulates experimentally induced inflammation in the trigeminal ganglion. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:99. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0581-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fejes-Szabo A, Bohar Z, Vamos E, Nagy-Grocz G, Tar L, Veres G, Zadori D, Szentirmai M, Tajti J, Szatmari I, Fulop F, Toldi J, Pardutz A, Vecsei L. Pre-treatment with new kynurenic acid amide dose-dependently prevents the nitroglycerine-induced neuronal activation and sensitization in cervical part of trigemino-cervical complex. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2014;121(7):725–738. doi: 10.1007/s00702-013-1146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knyihar-Csillik E, Toldi J, Mihaly A, Krisztin-Peva B, Chadaide Z, Nemeth H, Fenyo R, Vecsei L. Kynurenine in combination with probenecid mitigates the stimulation-induced increase of c-fos immunoreactivity of the rat caudal trigeminal nucleus in an experimental migraine model. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2007;114(4):417–421. doi: 10.1007/s00702-006-0545-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knyihar-Csillik E, Toldi J, Krisztin-Peva B, Chadaide Z, Nemeth H, Fenyo R, Vecsei L. Prevention of electrical stimulation-induced increase of c-fos immunoreaction in the caudal trigeminal nucleus by kynurenine combined with probenecid. Neurosci Lett. 2007;418(2):122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eftekhari S, Salvatore CA, Calamari A, Kane SA, Tajti J, Edvinsson L. Differential distribution of calcitonin gene-related peptide and its receptor components in the human trigeminal ganglion. Neuroscience. 2010;169(2):683–696. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aminian O, Eftekhari S, Mazaheri M, Sharifian SA, Sadeghniiat-Haghighi K. Urinary beta2 microglobulin in workers exposed to arc welding fumes. Acta Med Iran. 2011;49(11):748–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaiser EA, Russo AF. CGRP and migraine: could PACAP play a role too? Neuropeptides. 2013;47(6):451–461. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helyes Z, Pozsgai G, Borzsei R, Nemeth J, Bagoly T, Mark L, Pinter E, Toth G, Elekes K, Szolcsanyi J, Reglodi D. Inhibitory effect of PACAP-38 on acute neurogenic and non-neurogenic inflammatory processes in the rat. Peptides. 2007;28(9):1847–1855. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amin FM, Asghar MS, Guo S, Hougaard A, Hansen AE, Schytz HW, van der Geest RJ, de Koning PJ, Larsson HB, Olesen J, Ashina M. Headache and prolonged dilatation of the middle meningeal artery by PACAP38 in healthy volunteers. Cephalalgia. 2012;32(2):140–149. doi: 10.1177/0333102411431333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tuka B, Helyes Z, Markovics A, Bagoly T, Szolcsanyi J, Szabo N, Toth E, Kincses ZT, Vecsei L, Tajti J. Alterations in PACAP-38-like immunoreactivity in the plasma during ictal and interictal periods of migraine patients. Cephalalgia. 2013;33(13):1085–1095. doi: 10.1177/0333102413483931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tuka B, Szabo N, Toth E, Kincses ZT, Pardutz A, Szok D, Kortesi T, Bagoly T, Helyes Z, Edvinsson L, Vecsei L, Tajti J. Release of PACAP-38 in episodic cluster headache patients - an exploratory study. J Headache Pain. 2016;17(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0660-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mabuchi T, Shintani N, Matsumura S, Okuda-Ashitaka E, Hashimoto H, Muratani T, Minami T, Baba A, Ito S. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide is required for the development of spinal sensitization and induction of neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2004;24(33):7283–7291. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0983-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samsam M, Covenas R, Ahangari R, Yajeya J, Narvaez JA, Tramu G. Simultaneous depletion of neurokinin A, substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide from the caudal trigeminal nucleus of the rat during electrical stimulation of the trigeminal ganglion. Pain. 2000;84(2–3):389–395. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00240-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goadsby PJ, Edvinsson L, Ekman R. Vasoactive peptide release in the extracerebral circulation of humans during migraine headache. Ann Neurol. 1990;28(2):183–187. doi: 10.1002/ana.410280213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarchielli P, Alberti A, Baldi A, Coppola F, Rossi C, Pierguidi L, Floridi A, Calabresi P. Proinflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules, and lymphocyte integrin expression in the internal jugular blood of migraine patients without aura assessed ictally. Headache. 2006;46(2):200–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perini F, D’Andrea G, Galloni E, Pignatelli F, Billo G, Alba S, Bussone G, Toso V. Plasma cytokine levels in migraineurs and controls. Headache. 2005;45(7):926–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]