ABSTRACT

Bacteria have developed capacities to deal with different stresses and adapt to different environmental niches. The human pathogen Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of the severe diarrheal disease cholera, utilizes the transcriptional regulator OxyR to activate genes related to oxidative stress resistance, including peroxiredoxin PrxA, in response to hydrogen peroxide. In this study, we identified another OxyR homolog in V. cholerae, which we named OxyR2, and we renamed the previous OxyR OxyR1. We found that OxyR2 is required to activate its divergently transcribed gene ahpC, encoding an alkylhydroperoxide reductase, independently of H2O2. A conserved cysteine residue in OxyR2 is critical for this function. Mutation of either oxyR2 or ahpC rendered V. cholerae more resistant to H2O2. RNA sequencing analyses indicated that OxyR1-activated oxidative stress-resistant genes were highly expressed in oxyR2 mutants even in the absence of H2O2. Further genetic analyses suggest that OxyR2-activated AhpC modulates OxyR1 activity by maintaining low intracellular concentrations of H2O2. Furthermore, we showed that ΔoxyR2 and ΔahpC mutants were less fit when anaerobically grown bacteria were exposed to low levels of H2O2 or incubated in seawater. These results suggest that OxyR2 and AhpC play important roles in the V. cholerae oxidative stress response.

KEYWORDS: V. cholerae, ROS resistance, AhpC, OxyR, reactive oxygen species

INTRODUCTION

Vibrio cholerae is an aquatic bacterium that causes severe diarrheal disease in humans and affects thousands of people every year in regions of endemicity. Cholera infection is generally acquired through the ingestion of contaminated food or water. Once ingested, V. cholerae is able to survive the stomach acid shock and subsequently colonizes the mucosal layer of the small intestine, where it produces a cascade of virulence factors, including cholera toxin (CT), the agent primarily responsible for producing the severe symptoms of cholera infection (1, 2). The diarrhea facilitates V. cholerae's escape from the human host back into its natural aquatic habitat (3, 4). As V. cholerae transitions from the aquatic environment to the human host and back into the aquatic environment, it must sense a variety of different signals and respond accordingly by modulating gene expression to effectively adapt to its new niche. Oxidative stress is one such environmental signal that V. cholerae can face. Oxidative stress can cause mutations and damage proteins, DNA, cell membranes, etc. (5). Organisms must therefore have mechanisms to remove reactive oxygen species (ROS) and repair any damage caused. Any environment where oxygen is present has the potential to produce ROS such as the superoxide anion, hydroxyl radical, and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (5). For example, an aerobically grown bacterial culture can contain ROS; there are diverse reactive species, including ROS, in marine environments (6); and V. cholerae can experience ROS during infection. Stool samples collected from patients infected with V. cholerae contained higher levels of ROS and decreased levels of host antioxidant enzymes compared with uninfected persons (7, 8), and a recent proteomics study of duodenal biopsy specimens of cholera patients indicated activation of oxidative stress-related enzymes (9), suggesting an increase in ROS levels during infection. Thus, oxidative stress is a challenge that V. cholerae must respond to both in aquatic environments and inside the human host.

Most bacteria have multiple scavengers that maintain levels of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) at nanomolar concentrations (10). A widely conserved LysR-family transcriptional regulator, OxyR, has been shown to be involved in hydrogen peroxide resistance in many bacteria (11). The Escherichia coli OxyR is activated by hydrogen peroxide by either the modification of a key cysteine residue, C199, or formation of a disulfide bond between C199 and C206 (12–14). Activated OxyR then binds to the promoter of its target genes and activates their expression. Members of the E. coli OxyR regulon include genes encoding catalases KatG and KatE and alkylhydroperoxide reductase AhpC. AhpC belongs to a family of thiol peroxidases (peroxiredoxins), and together with its reducing partner AhpF, it scavenges H2O2 at low micromolar concentrations. Catalases are activated only when AhpC is saturated, at millimolar H2O2 concentrations (10). Several bacteria have AhpC, although not all have the reducing partner AhpF (e.g., Helicobacter pylori and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium) (10). In V. cholerae, OxyR positively activates genes for peroxiredoxin PrxA and DPS (DNA-binding protein from starved cells), and these genes are critical for V. cholerae oxidative stress resistance (15, 16). In this study, we sought to find additional peroxiredoxins that may be involved in V. cholerae oxidative stress resistance. By analyzing the V. cholerae genome, we identified an ahpC homolog on the large chromosome. Divergently transcribed from the putative ahpC gene is a gene encoding another LysR-family regulator. We show that this gene is required for ahpC activation and that AhpC is involved in fine-tuning V. cholerae responses to ROS through OxyR. We here name the ahpC regulator OxyR2 and rename the previous OxyR OxyR1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

OxyR2 activates ahpC expression, and a conserved cysteine residue is critical for OxyR2 function.

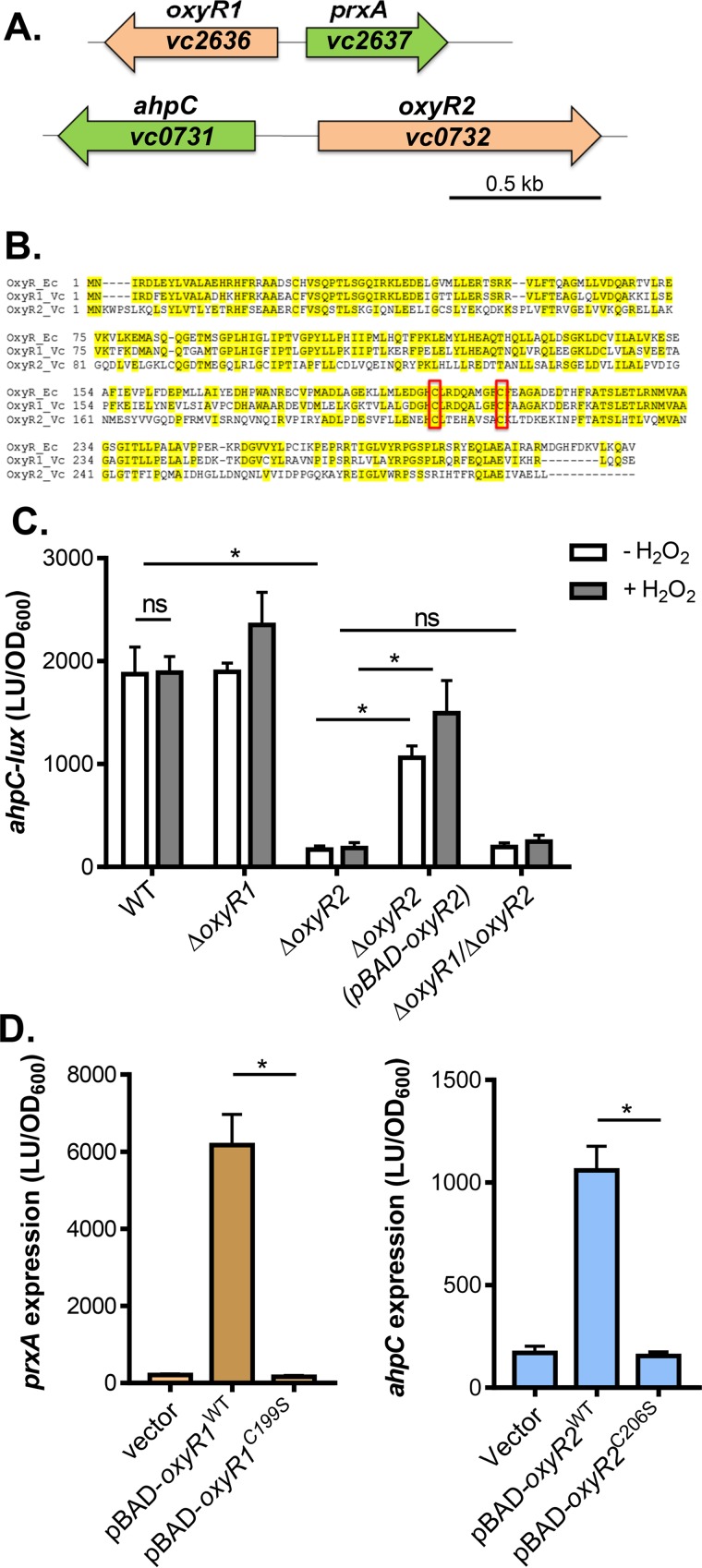

We have shown previously that in V. cholerae, OxyR (VC2636) upregulates the expression of its neighboring gene prxA (vc2637), encoding a peroxiredoxin (17). Both OxyR and PrxA are important for H2O2 resistance (15). To better understand how V. cholerae protects itself from oxidative stress, we searched for other peroxiredoxins in the V. cholerae genome and identified a putative ahpC homolog, vc0731. Similar to the oxyR-prxA genetic structure, a gene (vc0732) that is divergently transcribed from ahpC encodes another LysR-family transcriptional factor (Fig. 1A). VC0732 bears significant sequence homology to OxyR (47% to E. coli OxyR and 49% to V. cholerae OxyR), including the conserved two-cysteine motif (Fig. 1B, boxed). As such, we have annotated VC0732 as OxyR2 and henceforth refer to VC2636 (OxyR) as OxyR1.

FIG 1.

OxyR2 regulation of ahpC. (A) Schematic representation of the genetic structure of oxyR1-prxA and oxyR2-ahpC regulons. (B) Sequence alignment of E. coli OxyR (OxyR_Ec), V. cholerae VC2636 (OxyR1_Vc), and V. cholerae VC0732 (OxyR2_Vc). Conserved cysteine residues are boxed. (C) ahpC expression. Wild type, ΔoxyR1 ΔoxyR2 mutants, or ΔoxyR1ΔoxyR2 mutants containing the PahpC-luxCDABE transcriptional fusion plasmids were grown standing in AKI medium at 37°C for 4 h followed by shaking for 1 h until mid-log phase was reached. H2O2 (50 μM final concentration) was added to indicated cultures, and cultures were shaken at 37°C for 2 h. Luminescence was then measured and reported normalized to OD600. LU, luminescence unit. For complementation assays, 0.1% arabinose was included in the medium to activate pBAD-oxyR2. (D) The importance of cysteine residues in OxyR1 (left) and OxyR2 (right). pBAD-oxyR1WT or pBAD-oxyR1C199S was introduced into ΔoxyR1 (pPprxA-luxCDABE), and pBAD-oxyR2WT or pBAD-oxyR2C206S was introduced into ΔoxyR2 (pPahpC-luxCDABE). Arabinose (0.1%) was used to induce the PBAD promoter, and 50 μM H2O2 (final concentration) was added to activate OxyR1. Data shown represent the mean and standard deviation from three biological replicates. ns, not significant; *, Student t test P value of <0.05.

To explore the role of OxyR2 and AhpC in V. cholerae ROS resistance, we first examined ahpC transcriptional regulation. Using a PahpC-luxCDABE transcriptional fusion reporter, we found that ahpC was highly expressed in the wild type (WT) and that addition of hydrogen peroxide did not affect its expression (Fig. 1C), suggesting that ahpC expression is H2O2 independent. Deletion of oxyR1 did not affect ahpC expression, whereas deletion of oxyR2 abolished ahpC transcription (Fig. 1C). Expression of oxyR2 in trans restored ahpC expression in the ΔoxyR2 background (Fig. 1C). Finally, ahpC expression in ΔoxyR1 ΔoxyR2 double mutants was at a similarly low level as in ΔoxyR2 mutants. These results suggest that OxyR2 activates ahpC in an H2O2-independent manner.

To further analyze OxyR2 function, we mutated the first of the two conserved cysteine residues, Cys206, to serine and tested whether the OxyR2 mutant was still functional. In the E. coli OxyR, the first of the two cysteines (C199) has been shown to be involved in OxyR activation (12–14). The involvement of the second cysteine is debatable. As shown in Fig. 1D (left), OxyR1 C199 was critical; mutation of this residue significantly reduced OxyR1 activity. Similarly, OxyR2C206S could not activate ahpC expression (Fig. 1D, right), suggesting that this cysteine residue is critical for OxyR2 function. However, unlike OxyR1, OxyR2 activity is not dependent on H2O2, implying that the mechanisms of thiol modification through C206 may be different in the two OxyRs.

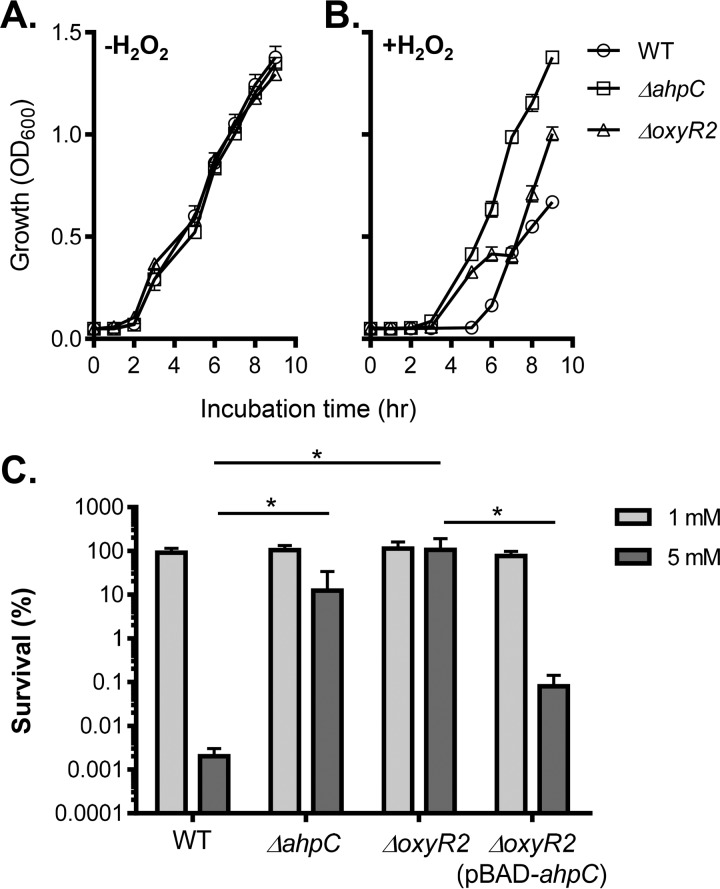

ΔoxyR2 and ΔahpC mutants are more resistant to hydrogen peroxide.

Next, we tested whether AhpC and OxyR2 are involved in ROS resistance in V. cholerae. We grew the wild type and ΔahpC and ΔoxyR2 mutants under virulence-inducing conditions (in AKI medium) (18) in the absence or in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. The virulence-inducing condition was used to mimic the in vivo condition that V. cholerae may encounter during the infection. Neither the ΔahpC nor the ΔoxyR2 mutant had any growth defect without addition of exogenous H2O2 (Fig. 2A). However, in the presence of H2O2, both ΔahpC and ΔoxyR2 mutants grew significantly better than the wild type (Fig. 2B). Of note, it is not clear why, in the presence of H2O2, ΔoxyR2 mutants appeared to have a plateau during the mid-log growth (Fig. 2B, triangles). It is possible that OxyR2 may regulate genes other than ahpC. To further confirm that ΔahpC and ΔoxyR2 mutants are more resistant to ROS, we exposed the mid-log-phase cultures of these strains to brief H2O2 treatment and examined their viability. We found that when bacteria were treated with 5 mM H2O2 for 2 h, over 99.9% of wild-type cells were readily killed, whereas both ΔahpC and ΔoxyR2 mutants were highly resistant (Fig. 2C). Expression of ahpC in ΔoxyR2 mutants partially restored H2O2 susceptibility (Fig. 2C). These results indicate that V. cholerae strains that lack AhpC or its cognate activator OxyR2 are hyperresistant to ROS.

FIG 2.

AhpC and OxyR2 effects on ROS resistance. (A and B) Growth of V. cholerae wild type and mutants at 37°C in the absence (A) and presence (B) of 150 μM H2O2. Cultures were grown standing in virulence-inducing AKI medium at 37°C, and OD600 was measured at the time points indicated. (C) Killing assay of V. cholerae wild type and mutants in the presence of 1 mM and 5 mM H2O2. Cultures were grown standing for 4 h followed by shaking for 2 h at 37°C. Arabinose (0.1%) was used to induce the PBAD promoter. H2O2 was then added at the indicated concentrations (1 mM and 5 mM), and the cultures were incubated at 37°C with shaking for 2 h. Percent survival was calculated for each strain by comparing CFU of treated samples to that of untreated samples. Data shown represent the mean and standard deviation from three biological replicates. *, P value < 0.05.

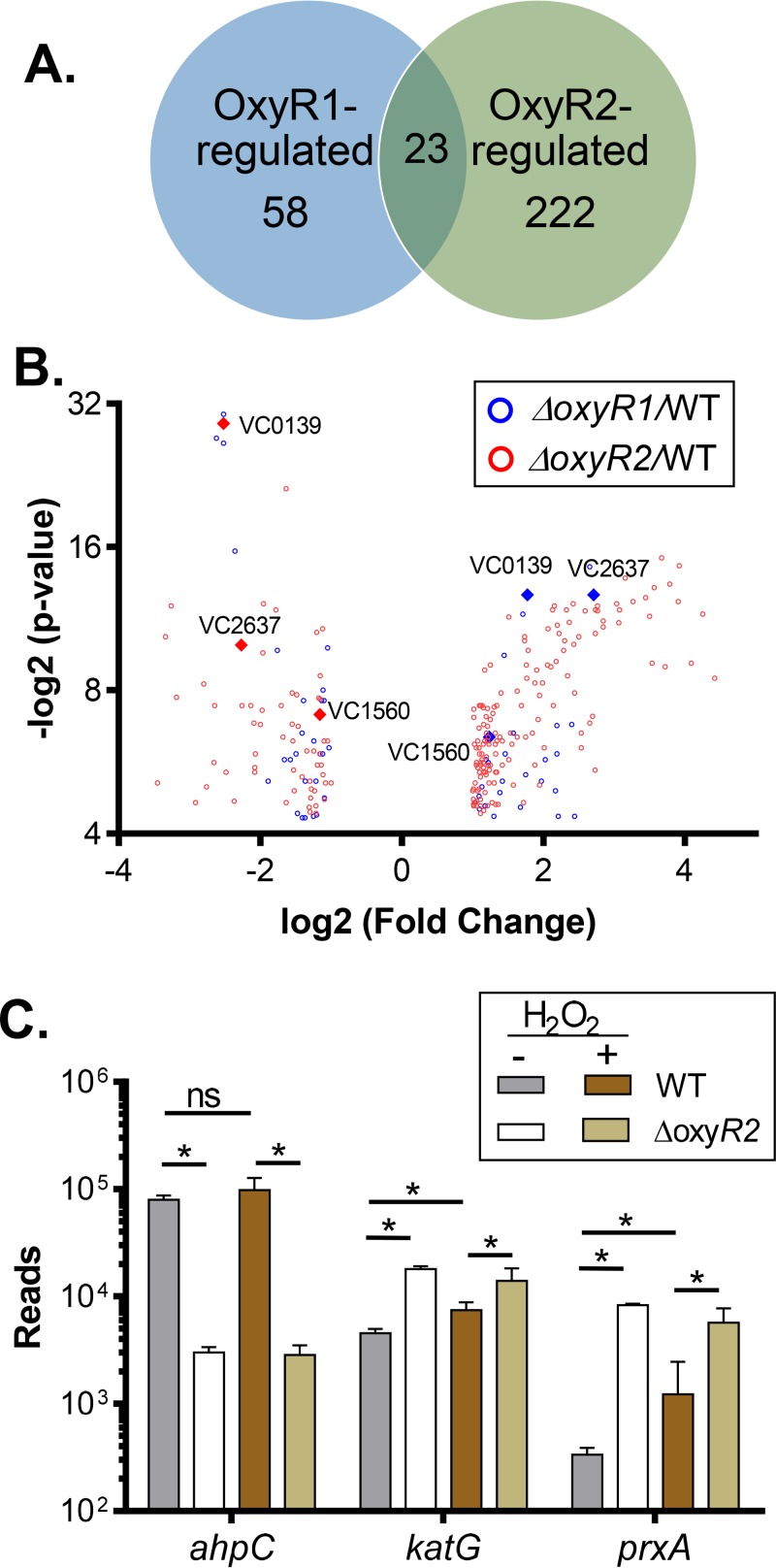

RNA sequencing reveals opposing roles for OxyR1 and OxyR2 in regulation of ROS-resistant genes.

To investigate whether the increased ROS resistance of ΔahpC and ΔoxyR2 is linked to OxyR1 regulation, we performed transcriptome analysis using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). We grew wild-type, ΔoxyR1, and ΔoxyR2 strains in AKI medium until mid-log phase (determined by a growth curve analysis) and exposed cultures to 0 and 50 μM H2O2 for 60 min. RNA was extracted and subjected to RNA-seq analysis. The analysis identified expression of over 3,600 coding DNA sequence (CDS) tags in each sample. Biological replicates were tightly clustered (data not shown), indicating consistency between replicates. We analyzed differential expression of genes in the WT versus the mutant in the presence of H2O2. We identified a total of 58 genes that were at least 2-fold differentially expressed in the ΔoxyR1 mutant and 222 genes that were differentially expressed in the ΔoxyR2 mutant (see Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). In addition to regulation of ROS resistance-related genes (see below), OxyR1 also affects transcription of a two-component regulatory system, VC1084-VC1086. Deletion of VC1086 has been shown to have slightly enhanced colonization (19). Moreover, OxyR1 negatively regulates genes needed for CTX phage production, such as the VC1453-VC1454 and VC1462-VC1463 genes (20). Interestingly, in ΔoxyR2 mutants, the expression of several virulence genes, such as tcpA (vc0828) and toxT (vc0838), was downregulated. Further studies to fully understand OxyR1- and OxyR2-regulated genes are ongoing. Next, we compared OxyR1-regulated genes with OxyR2-regulated genes using a Venn diagram and a volcano plot (Fig. 3A and B). We found that a number of ROS resistance-related genes (Fig. 3B, diamonds), such as vc0139 (dps), vc1560 (katG), and vc2637 (prxA), were highly induced in the ΔoxyR2 mutant background but had reduced expression in the ΔoxyR1 mutants, suggesting that these genes are activated by OxyR1 but that their expression is negatively affected by OxyR2. Figure 3C shows the reads of selected genes under different conditions. The RNA-seq data corroborated our finding that ahpC expression is dependent on OxyR2 but independent of H2O2 (Fig. 3C). The expression of both prxA and katG was also significantly higher in the presence of H2O2 in an OxyR1-dependent manner (Fig. 3C), confirming previous findings (15, 17). Both prxA and katG transcriptome levels were significantly higher in the ΔoxyR2 mutants, either in the absence or in the presence of H2O2, again implying that OxyR2 may negatively affect OxyR1-activated gene expression.

FIG 3.

Determination of OxyR1- and OxyR2-regulated genes by RNA sequencing. (A and B) Venn diagram (A) and volcano plot (B) of differentially expressed genes (fold change of >2, P value of <0.05) in ΔoxyR1 (blue) and ΔoxyR2 (red) strains in the presence of 50 μM H2O2. Diamonds represent oxidative stress-related genes common to the two data sets. (C) Normalized RNA-seq reads of selected genes in the wild-type and ΔoxyR2 strains in the presence and absence of 50 μM H2O2. Data shown represent the mean and standard deviation from two biological replicates. *, P value < 0.05; ns, not significant.

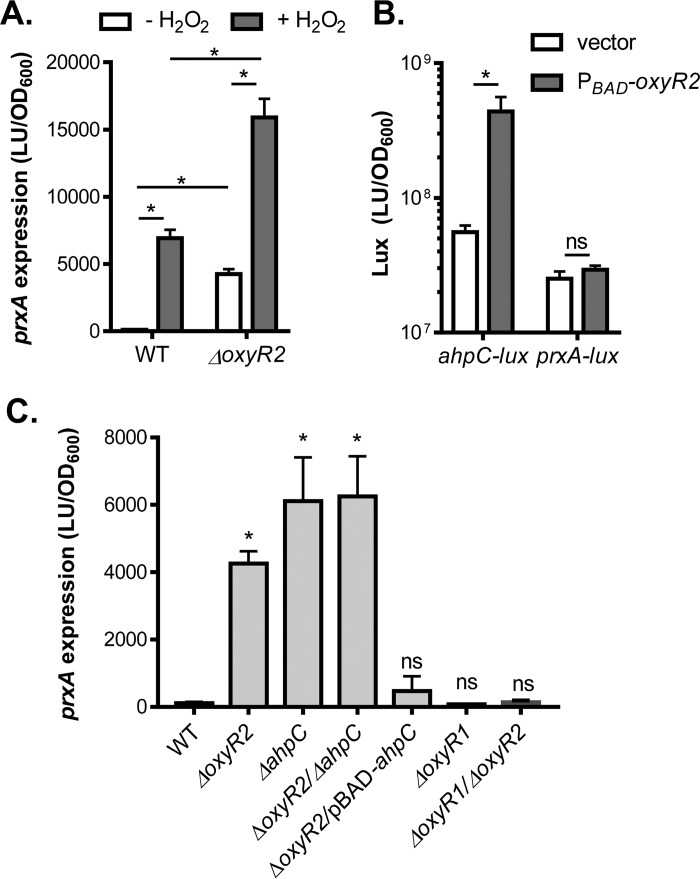

OxyR2-activated AhpC modulates OxyR1 activity.

To further validate the RNA-seq data, we used a PprxA-luxCDABE transcriptional reporter to measure prxA expression in the wild type. We have shown previously that OxyR1-activated prxA expression is H2O2 dependent (15, 17). Deletion of oxyR2 strongly induced prxA expression even in the absence of H2O2 (Fig. 4A), consistent with the RNA-seq data. To investigate how OxyR2 negatively affects prxA expression, we first examined whether OxyR2 regulates prxA expression directly. We found that in E. coli, V. cholerae OxyR2 could activate ahpC expression independently of H2O2 (Fig. 4B), indicating that OxyR2 functions in E. coli and OxyR2 activation of ahpC may be direct. However, in E. coli, prxA expression was not affected by OxyR2 (Fig. 4B), suggesting that OxyR2 may not transcriptionally regulate prxA directly. To examine whether OxyR2 effects on prxA expression occur through OxyR2-activated AhpC, we examined prxA expression in the absence of H2O2 in different V. cholerae mutants. We found that, similarly to that in the ΔoxyR2 mutant, prxA expression was strongly induced in both ΔahpC mutants and ΔahpC ΔoxyR2 double mutants, whereas expression of ahpC in ΔoxyR2 mutants reduced prxA induction (Fig. 4C), suggesting that the OxyR2 effect on prxA expression may occur through AhpC. Furthermore, deletion of oxyR1 abolished prxA expression (Fig. 4C), even in the oxyR2 mutation background, suggesting that OxyR1 is required and OxyR2-AhpC may modulate OxyR1 activity and thereby the expression profiles of the OxyR1 regulon.

FIG 4.

OxyR2-AhpC effects on prxA expression. (A) Confirming RNA-seq data using PprxA-luxCDABE reporters. The wild type and the ΔoxyR2 mutant containing the PprxA-luxCDABE transcriptional fusion plasmids were grown standing in AKI medium at 37°C for 4 h followed by shaking for 1 h. H2O2 (50 μM final concentration) was added to indicated cultures, and cultures were shaken at 37°C for 2 h. Luminescence was then measured and reported normalized to OD600. (B) OxyR2 effects on ahpC and prxA expression in E. coli. DH5α containing pBAD24 (vector control) or pBAD-oxyR2 and PahpC-luxCDABE or PprxA-luxCDABE reporter plasmids was grown in LB containing 0.3% arabinose until reaching an OD600 of 0.4. Luminescence was then measured and normalized to OD600. (C) prxA expression in different V. cholerae mutants. The wild type and different mutants indicated containing the PprxA-luxCDABE plasmids were grown under the conditions described for panel A (without H2O2). Luminescence was then measured and reported normalized to OD600. Data shown represent the mean and standard deviation from three biological replicates. *, P value < 0.05; ns, no significance; LU, luminescence unit.

In E. coli, it has been shown that AhpC is the primary scavenger of endogenous H2O2 as it can efficiently scavenge trace H2O2 (21). Thus, ahpC mutants accumulate sufficient hydrogen peroxide to induce the OxyR regulon, including genes encoding catalase, which is the predominant scavenger when H2O2 concentrations are high. Based on the studies in E. coli and the above results, we speculate that OxyR2-activated AhpC modulates OxyR1 activity by maintaining low intracellular concentrations of H2O2. Below a certain threshold of H2O2 concentration, OxyR1 and its regulon remain inactive and AhpC serves as the primary scavenger for H2O2. However, if that threshold is surpassed, due to either an exogenous increase in H2O2 levels or the absence of OxyR2 and/or AhpC, then the OxyR1 regulon is activated. This may explain why ΔahpC/oxyR2 mutants are more resistant to H2O2 than the wild type (Fig. 2) as accumulation of endogenous H2O2 results from the absence of AhpC “preinduction” of OxyR1-activated genes, such as catalases and PrxA.

OxyR2-regulated AhpC contributes to V. cholerae environmental survival but not in vivo colonization.

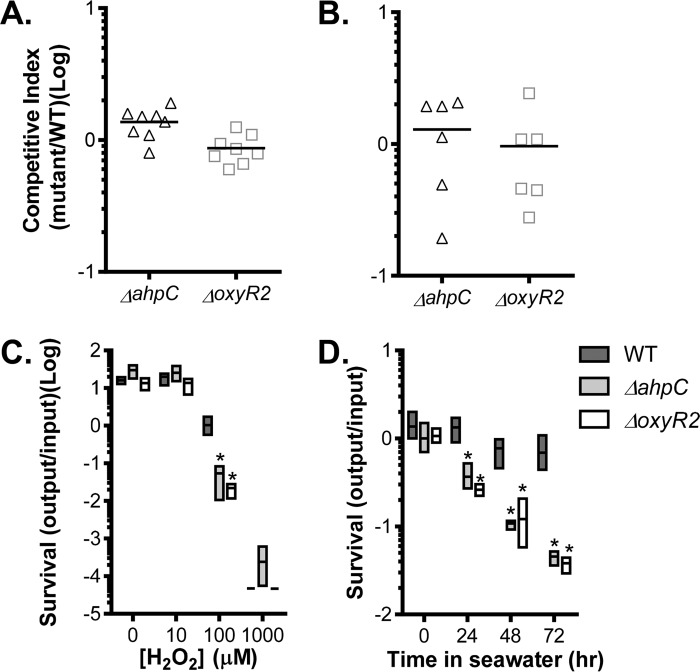

To investigate the physiological role of OxyR2-activated AhpC in V. cholerae, we first examined whether deletion of oxyR2 or ahpC affects V. cholerae colonization. In an infant mouse competition model (22), we found that both ΔahpC and ΔoxyR2 mutants colonized as well as the wild type (Fig. 5A). Similar results were obtained when we performed ΔahpC/ΔoxyR2 mutant competition assays using a streptomycin-treated adult mouse model (23) (Fig. 5B), suggesting that OxyR2-AhpC is not required for V. cholerae colonization, at least under the conditions tested. Since V. cholerae encounters oxygen-limiting conditions and host-derived oxidative stress during colonization of the host small intestines (9, 24), we grew the wild type and ΔahpC and ΔoxyR2 mutants anaerobically and exposed them to different levels of H2O2. At very low (≤10 μM) or very high (≥1 mM) H2O2 concentrations, the mutants grew similarly to the wild type (Fig. 5C). However, at an intermediate level of H2O2 (100 μM), both ΔahpC and ΔoxyR2 mutants displayed growth defects, suggesting that under oxygen-limiting conditions, AhpC may be required to remove harmful levels of ROS. Finally, we tested whether OxyR2-AhpC is important for V. cholerae survival in seawater. To mimic the environment that V. cholerae encounters during the transition from oxygen-poor guts to oxygen-rich aquatic reservoirs, we grew the wild type and ΔahpC and ΔoxyR2 mutants at 37°C under oxygen-limiting conditions and then incubated the bacterial cells in seawater at 22°C. We found that the number of viable cells of ΔahpC and ΔoxyR2 mutants was significantly reduced compared to the wild type (Fig. 5D). The viable cells of the mutants were similar to the wild type when we incubated aerobically grown cells in seawater (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that OxyR2-AhpC plays an important role in detoxifying low levels of environmental oxidative stresses.

FIG 5.

Physiological roles of OxyR2-AhpC. (A) Infant mouse colonization. Approximately 106 cells of the wild type (lacZ) and ΔoxyR2 or ΔahpC mutants (lacZ+) were intragastrically inoculated into 6-day-old CD-1 mice in a 1:1 ratio. After a 12-h incubation, CFU from small intestines was determined by serial dilution and plating on LB agar. The data shown are from three independent experiments, and each symbol represents CFU recovered from one mouse intestine. The horizontal line represents the average number of cells recovered. (B) Streptomycin-treated adult mouse model. Five-week-old CD-1 mice were treated with streptomycin, and a saturated culture of wild type (lacZ) and mutants (lacZ+) was mixed in a 1:1 ratio and intragastrically administered to each mouse. Fecal pellets were collected from each mouse after 3 days, resuspended in LB, serially diluted, and then plated on plates containing X-Gal. The competitive index (CI) was calculated as the ratio of mutant to wild-type colonies normalized to the input ratio. The horizontal line represents the average CI. (C) Anaerobic survival. AKI medium with indicated concentrations of H2O2 was inoculated with anaerobically grown cultures and grown in the anaerobic chamber at 37°C for 24 h. Samples were serially diluted and plated to enumerate cell counts. Growth was measured and represented as a ratio of output/input. (D) Seawater survival. The wild type, ΔahpC, or ΔoxyR2 strain was grown in AKI medium anaerobically at 37°C for 4 h. Bacterial cells were then collected, washed, and then resuspended in artificial seawater and incubated at 22°C. At the indicated intervals, viable cells were determined by serial dilutions and plating on LB plates. Data shown represent the mean and standard deviation from at least three biological replicates. *, P value < 0.05.

In this study, we identified a second OxyR homolog, OxyR2, in V. cholerae that is required to activate the alkylhydroperoxide reductase gene ahpC. We hypothesize that OxyR2-AhpC removes low levels of ROS and modulates OxyR1 activity in V. cholerae. OxyR2-regulated AhpC may be particularly important for V. cholerae to better adapt to environmental niches that pose low levels of oxidative stress such as in inflammatory intestines and exiting from the gut to aquatic environments (Fig. 5C and D). In Vibrio vulnificus, there are two OxyR homologs, which control different peroxiredoxin genes (25). V. vulnificus OxyR2 senses H2O2 with high sensitivity (26). Coexistence of OxyR1 and OxyR2 homologs is widespread in many other bacteria (25), implying the importance of fine-tuning ROS resistance for optimal environmental adaptation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

All V. cholerae strains used in this study were derived from O1 El Tor C6706 (27) and are listed in Table 1. All strains were propagated at 37°C in LB medium containing appropriate antibiotics and 1.5% agar where necessary. In-frame deletions of oxyR2 (vc0732) and ahpC (vc0731) were constructed by cloning the flanking regions of these genes into the suicide vector pWM91 containing a sacB-counterselectable marker (28). The resulting constructs were introduced into V. cholerae by conjugation, and deletion mutants were selected for double homologous recombination events. The ahpC transcriptional fusion luminescence reporters were constructed by cloning the ahpC promoter sequences into the pBBR-lux plasmid, which contains a promoterless luxCDABE reporter (29). Constructions of the oxyR1 (vc2636) in-frame deletion and the prxA (vc2637) lux reporter have been previously described (15, 17). OxyR1 and OxyR2 cysteine→serine mutations were constructed by overlap extension PCR (24). For expression of oxyR1, oxyR2, and their cysteine mutant derivatives, PCR-amplified fragments of oxyR1 or oxyR2 were cloned into pBAD24 (30), which contains an arabinose-inducible PBAD promoter. A similar strategy was also used for construction of pBAD-ahpC. The plasmids and primers used in this study are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Characteristic or sequence (5′ to 3′) | Reference, source, or purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| C6706 | V. cholerae O1 El Tor wild-type strain | 27 |

| ΔoxyR1 mutant | VC2636 in-frame deletion mutant | 15 |

| ΔoxyR2 mutant | VC0732 in-frame deletion mutant | This work |

| ΔahpC mutant | VC0731 in-frame deletion mutant | This work |

| ΔoxyR2/ΔahpC mutant | VC0732 and VC0731 double deletion mutant | This work |

| ΔoxyR1/ΔoxyR2 mutant | VC2636 and VC0732 double deletion mutant | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pWM91 | Suicide vector | 28 |

| pBBR-lux | Plasmid containing a promoterless luxCDABE reporter | 29 |

| pBAD24 | Plasmid containing an arabinose-inducible PBAD promoter | 30 |

| pBAD-oxyR1 | PBAD-oxyR1 WT in pBAD24 | 15 |

| pBAD-oxyR2 | PBAD-oxyR2 WT in pBAD24 | This work |

| pBAD-oxyR1C199S | PBAD-oxyR1 cysteine 199→serine mutation in pBAD24 | This work |

| pBAD-oxyR2C206S | PBAD-oxyR2 cysteine 206→serine mutation in pBAD24 | This work |

| pBAD-ahpC | PBAD-ahpC WT in pBAD24 | This work |

| pPrxA-lux | PprxA-luxCDABE in pBBR-lux | 15 |

| pAhpC-lux | PahpC-luxCDABE in pBBR-lux | This work |

| Primers | ||

| oxyR2-1 | TCACTCGAGCAGGAATGAACCACGGAAAG | ΔoxyR2 |

| oxyR2-2 | GTTCAGCCACGAGGCTTGGCCATTTATTCA | |

| oxyR2-3 | GCCAAGCCTCGTGGCTGAACTGTTATAGCG | |

| oxyR2-4 | TAAGCGGCCGCTGTTGGGTTAATTCAGCAGT | |

| ahpC-1 | CCGCTCGAGCTTGATGCGCCGTACGAATG | ΔahpC |

| ahpC-2 | TTAGGAGCAAAAATAAGACTCTTAACCCCG | |

| ahpC-3 | AGTCTTATTTTTGCTCCTAAGCAATTTTGT | |

| ahpC-4 | AAGCGGCCGCCTTCGCGCAACAATAAGTGC | |

| PahpC-1 | ATCGAGCTCACCCGAGTAAATACCAGAGG | ahpC-lux |

| PahpC-2 | GGATCCATTTTTTTGCTCCTAAGCAA | |

| pBAD-oxyR2-1 | GGGGTACCATGAATAAATGGCCAAGCCT | pBAD-oxyR2 |

| pBAD-oxyR2-2 | GCTCTAGACTATAACAGTTCAGCCACTA | |

| pBAD-oxyR2-3 | ATGTTCAGTTAAAGAGTGCTCGTTTTCGAGTAAA | pBAD-oxyR2C206S |

| pBAD-oxyR2-4 | AAACGAGCACTCTTTAACTGAACATGCCGTATC | |

| pBAD-oxyR1*-1 | CCCAAGCTTTTACTCGCTTTGCTGTAAGC | pBAD-oxyR1C199S |

| pBAD-oxyR1*-2 | GGAGATGGGCATTCCCTGCGCGATCAAGCGTTA | |

| pBAD-oxyR1*-3 | TTGATCGCGCAGGCAATGCGCATCTCCTAAAGC | |

| pBAD-oxyR1*-4 | CGGAATTCATGAACATTCGTGATTTTGAATAC | |

| pBAD-ahpC-1 | TGCTCTAGATTATTTTAGGTCAGCAGAGT | pBAD-ahpC |

| pBAD-ahpC-2 | CCGGAATTCTTGCTTAGGAGCAAAAAAAT |

V. cholerae ROS resistance assays.

V. cholerae strains were grown overnight at 37°C on LB plates with appropriate antibiotics and normalized to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0 in liquid medium. A 1:1,000 dilution of normalized culture was used to inoculate fresh AKI medium (18). H2O2 (150 μM final concentration) was added to each culture, and the cultures were incubated at 37°C standing in a 96-well plate. OD600 was measured using a microplate reader at the indicated time points.

For hydrogen peroxide killing assays, V. cholerae strains were grown overnight at 37°C on LB plates with appropriate antibiotics and normalized to an OD600 of 1.0 in liquid medium. A 1:1,000 dilution of normalized culture was used to inoculate fresh AKI medium. Cultures were grown standing for 4 h followed by shaking for 2 h at 37°C. H2O2 was then added to appropriate concentrations (1 mM and 5 mM), and the cultures were incubated at 37°C with shaking for 2 h. Viable cells were determined by serial dilutions and plating on LB plates. Percent survival was calculated for each strain by comparing CFU of H2O2-treated samples to that of untreated samples.

For testing ROS resistance under anaerobic growth conditions, V. cholerae strains were grown overnight at 37°C in LB with appropriate antibiotics in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratories) and normalized to an OD600 of 1.0 in fresh liquid medium. A 1:1,000 dilution of normalized culture was used to inoculate fresh AKI medium containing indicated concentrations of H2O2. Cultures were incubated in the anaerobic chamber at 37°C for 24 h. Viable cells were determined by serial dilutions and plating on LB plates.

RNA sequencing.

Overnight cultures of wild-type, ΔoxyR1, and ΔoxyR2 strains were inoculated 1:1,000 into fresh AKI medium. Cultures were grown without shaking for 4 h and subsequently treated with or without 50 μM H2O2 for 1 h at 37°C. RNA was extracted from cultures using TRIzol and an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions and was subjected to RNA sequencing. RNA sequencing was conducted at PrimBio Research Institute LLC (Exton, PA, USA). Briefly, the rRNA-depleted RNA was used to construct a cDNA library by using the Ion Total RNA-seq kit (Life Technologies). Amplified PCR products from cDNA libraries were then loaded on Ion P1 chips for Ion Torrent RNA-seq. Following the proton run, the raw sequences were aligned to the V. cholerae N16961 genome. Aligned BAM files were used for further analysis. BAM files, separated by the specific barcodes, were uploaded to the Strand NGS software (San Francisco, CA). After filtering, the aligned reads were normalized and quantified using the DESeq algorithm by Strand NGS. The standard t test was used to determine significantly differentially expressed genes based on two replicates for each condition.

Measuring transcriptional expression using Lux reporters.

Wild-type, ΔoxyR1, and ΔoxyR2 strains and their cysteine mutant derivatives containing either PahpC-luxCDABE or PprxA-luxCDABE transcriptional fusion plasmids were grown overnight at 37°C on LB plates with appropriate antibiotics and normalized to an OD600 of 1.0 in liquid medium. Strains were inoculated at 1:100 into fresh AKI medium containing appropriate antibiotics and grown standing at 37°C for 4 h followed by shaking for 1 h. H2O2 (50 μM final concentration) was then added, and cultures were incubated for an additional 2 h with shaking. Samples were then collected from growing cultures, and luminescence was read using a microplate reader and normalized for growth against optical density at 600 nm. Lux expression is reported as light units per OD600.

In vivo colonization assays.

All animal experiments were carried out in strict accordance with the animal protocol number 805287 that was approved by the IACUC of the University of Pennsylvania. The infant mouse colonization assay was performed as previously described (31) by inoculating approximately 105 V. cholerae cells per mouse into 6-day-old suckling CD-1 mice in a 1:1 ratio of mutant (lacZ+) to wild type (lacZ). At 12 h postinfection, mice were sacrificed and their intestinal homogenates were collected. Samples were serially diluted and plated on LB agar plates containing appropriate antibiotics and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) to differentiate between wild-type and mutant strains.

The streptomycin-treated adult mouse model was used as previously described (23, 32). Briefly, 5-week-old CD-1 mice were provided with drinking water containing 0.5% (wt/vol) streptomycin and 0.5% sucrose. One day after streptomycin treatment, approximately 108 cells each of two strains (wild type and mutant) were mixed at a 1:1 ratio and intragastrically administered to each mouse. Three days after they were inoculated, fecal pellets were collected from each mouse, resuspended in LB, serially diluted, and then plated on plates containing X-Gal. The competitive index was calculated as the ratio of mutant to wild-type colonies normalized to the input ratio.

Environmental survival assays.

The wild-type, ΔahpC, or ΔoxyR2 strain was grown overnight at 37°C in LB with appropriate antibiotics and normalized to an OD600 of 1.0 in fresh liquid medium. A 1:1,000 dilution of normalized culture was used to inoculate fresh AKI medium and grown anaerobically at 37°C for 4 h. Bacterial cells were then collected, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer, and then resuspended in artificial seawater (ASW) (33) and incubated at 22°C. At the indicated intervals, viable cells were determined by serial dilutions and plating on LB plates.

Accession number(s).

Sequencing data for RNA-seq experiments are accessible at SRP095131 in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Diana Ye for helpful discussion.

This study was supported by NIH/NIAID R01AI120489 and R21AI109316 (to J.Z.), an NSFC grant (81371763), and a 973 project (2015CB554203) (to H.W.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00929-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sack DA, Sack RB, Nair GB, Siddique AK. 2004. Cholera. Lancet 363:223–233. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matson JS, Withey JH, DiRita VJ. 2007. Regulatory networks controlling Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression. Infect Immun 75:5542–5549. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01094-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faruque SM, Nair GB. 2002. Molecular ecology of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae. Microbiol Immunol 46:59–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2002.tb02659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson EJ, Harris JB, Morris JG Jr, Calderwood SB, Camilli A. 2009. Cholera transmission: the host, pathogen and bacteriophage dynamic. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:693–702. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imlay JA. 2008. Cellular defenses against superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Annu Rev Biochem 77:755–776. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061606.161055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lesser MP. 2006. Oxidative stress in marine environments: biochemistry and physiological ecology. Annu Rev Physiol 68:253–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040104.110001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhattacharyya S, Ghosh S, Shant J, Ganguly NK, Majumdar S. 2004. Role of the W07-toxin on Vibrio cholerae-induced diarrhoea. Biochim Biophys Acta 1670:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qadri F, Raqib R, Ahmed F, Rahman T, Wenneras C, Das SK, Alam NH, Mathan MM, Svennerholm AM. 2002. Increased levels of inflammatory mediators in children and adults infected with Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 9:221–229. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.2.221-229.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis CN, LaRocque RC, Uddin T, Krastins B, Mayo-Smith LM, Sarracino D, Karlsson EK, Rahman A, Shirin T, Bhuiyan TR, Chowdhury F, Khan AI, Ryan ET, Calderwood SB, Qadri F, Harris JB. 2015. Comparative proteomic analysis reveals activation of mucosal innate immune signaling pathways during cholera. Infect Immun 83:1089–1103. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02765-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishra S, Imlay J. 2012. Why do bacteria use so many enzymes to scavenge hydrogen peroxide? Arch Biochem Biophys 525:145–160. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maddocks SE, Oyston PC. 2008. Structure and function of the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family proteins. Microbiology 154:3609–3623. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/022772-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee C, Lee SM, Mukhopadhyay P, Kim SJ, Lee SC, Ahn WS, Yu MH, Storz G, Ryu SE. 2004. Redox regulation of OxyR requires specific disulfide bond formation involving a rapid kinetic reaction path. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11:1179–1185. doi: 10.1038/nsmb856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SO, Merchant K, Nudelman R, Beyer WF Jr, Keng T, DeAngelo J, Hausladen A, Stamler JS. 2002. OxyR: a molecular code for redox-related signaling. Cell 109:383–396. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00723-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helmann JD. 2002. OxyR: a molecular code for redox sensing? Sci STKE 2002:pe46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H, Chen S, Zhang J, Rothenbacher FP, Jiang T, Kan B, Zhong Z, Zhu J. 2012. Catalases promote resistance of oxidative stress in Vibrio cholerae. PLoS One 7:e53383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia X, Larios-Valencia J, Liu Z, Xiang F, Kan B, Wang H, Zhu J. OxyR-activated expression of Dps is important for Vibrio cholerae oxidative stress resistance and pathogenesis. PLoS One, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stern AM, Hay AJ, Liu Z, Desland FA, Zhang J, Zhong Z, Zhu J. 2012. The NorR regulon is critical for Vibrio cholerae resistance to nitric oxide and sustained colonization of the intestines. mBio 3:e00013-12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00013-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwanaga M, Yamamoto K, Higa N, Ichinose Y, Nakasone N, Tanabe M. 1986. Culture conditions for stimulating cholera toxin production by Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. Microbiol Immunol 30:1075–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1986.tb03037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng AT, Ottemann KM, Yildiz FH. 2015. Vibrio cholerae response regulator VxrB controls colonization and regulates the type VI secretion system. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004933. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waldor MK, Friedman DI. 2005. Phage regulatory circuits and virulence gene expression. Curr Opin Microbiol 8:459–465. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seaver LC, Imlay JA. 2001. Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase is the primary scavenger of endogenous hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 183:7173–7181. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.24.7173-7181.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Z, Wang Y, Liu S, Sheng Y, Rueggeberg KG, Wang H, Li J, Gu FX, Zhong Z, Kan B, Zhu J. 2015. Vibrio cholerae represses polysaccharide synthesis to promote motility in mucosa. Infect Immun 83:1114–1121. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02841-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Z, Wang H, Zhou Z, Sheng Y, Naseer N, Kan B, Zhu J. 2016. Thiol-based switch mechanism of virulence regulator AphB modulates oxidative stress response in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol 102:939–949. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Z, Yang M, Peterfreund GL, Tsou AM, Selamoglu N, Daldal F, Zhong Z, Kan B, Zhu J. 2011. Vibrio cholerae anaerobic induction of virulence gene expression is controlled by thiol-based switches of virulence regulator AphB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:810–815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014640108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim S, Bang YJ, Kim D, Lim JG, Oh MH, Choi SH. 2014. Distinct characteristics of OxyR2, a new OxyR-type regulator, ensuring expression of peroxiredoxin 2 detoxifying low levels of hydrogen peroxide in Vibrio vulnificus. Mol Microbiol 93:992–1009. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bang YJ, Lee ZW, Kim D, Jo I, Ha NC, Choi SH. 2016. OxyR2 functions as a three-state redox switch to tightly regulate production of Prx2, a peroxiredoxin of Vibrio vulnificus. J Biol Chem 291:16038–16047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.710343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joelsson A, Liu Z, Zhu J. 2006. Genetic and phenotypic diversity of quorum-sensing systems in clinical and environmental isolates of Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun 74:1141–1147. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1141-1147.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metcalf WW, Jiang W, Daniels LL, Kim SK, Haldimann A, Wanner BL. 1996. Conditionally replicative and conjugative plasmids carrying lacZ alpha for cloning, mutagenesis, and allele replacement in bacteria. Plasmid 35:1–13. doi: 10.1006/plas.1996.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammer BK, Bassler BL. 2007. Regulatory small RNAs circumvent the conventional quorum sensing pathway in pandemic Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:11145–11149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703860104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J Bacteriol 177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu J, Miller MB, Vance RE, Dziejman M, Bassler BL, Mekalanos JJ. 2002. Quorum-sensing regulators control virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:3129–3134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052694299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheng Y, Fan F, Jensen O, Zhong Z, Kan B, Wang H, Zhu J. 2015. Dual zinc transporter systems in Vibrio cholerae promote competitive advantages over gut microbiome. Infect Immun 83:3902–3908. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00447-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kierek K, Watnick PI. 2003. Environmental determinants of Vibrio cholerae biofilm development. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:5079–5088. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.9.5079-5088.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.