Abstract

Background

Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker’s yeast) has great potential as a whole-cell biocatalyst for multistep synthesis of various organic molecules. To date, however, few examples exist in the literature of the successful biosynthetic production of chemical compounds, in yeast, that do not exist in nature. Considering that more than 30% of all drugs on the market are purely chemical compounds, often produced by harsh synthetic chemistry or with very low yields, novel and environmentally sound production routes are highly desirable. Here, we explore the biosynthetic production of enantiomeric precursors of the anti-tuberculosis and anti-epilepsy drugs ethambutol, brivaracetam, and levetiracetam. To this end, we have generated heterologous biosynthetic pathways leading to the production of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid (ABA) and (S)-2-aminobutanol in baker’s yeast.

Results

We first designed a two-step heterologous pathway, starting with the endogenous amino acid l-threonine and leading to the production of enantiopure (S)-2-aminobutyric acid. The combination of Bacillus subtilis threonine deaminase and a mutated Escherichia coli glutamate dehydrogenase resulted in the intracellular accumulation of 0.40 mg/L of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid. The combination of a threonine deaminase from Solanum lycopersicum (tomato) with two copies of mutated glutamate dehydrogenase from E. coli resulted in the accumulation of comparable amounts of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid. Additional l-threonine feeding elevated (S)-2-aminobutyric acid production to more than 1.70 mg/L. Removing feedback inhibition of aspartate kinase HOM3, an enzyme involved in threonine biosynthesis in yeast, elevated (S)-2-aminobutyric acid biosynthesis to above 0.49 mg/L in cultures not receiving additional l-threonine. We ultimately extended the pathway from (S)-2-aminobutyric acid to (S)-2-aminobutanol by introducing two reductases and a phosphopantetheinyl transferase. The engineered strains produced up to 1.10 mg/L (S)-2-aminobutanol.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate the biosynthesis of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid and (S)-2-aminobutanol in yeast. To our knowledge this is the first time that the purely synthetic compound (S)-2-aminobutanol has been produced in vivo. This work paves the way to greener and more sustainable production of chemical entities hitherto inaccessible to synthetic biology.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12934-017-0667-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: (S)-2-Aminobutyric acid, l-Homoalanine, (S)-2-Aminobutanol, Carboxylic acid reductase, l-Threonine, 2-Ketobutyric acid, Metabolic engineering, Ethambutol

Background

(S)-2-Aminobutyric acid (ABA), also known as l-homoalanine, is a non-proteinogenic α-amino acid, which is a chiral precursor for the enantiomeric pharmaceuticals levetiracetam, brivaracetam, and ethambutol [1, 2]. Enzymatic synthesis of chiral (R)- or (S)-2-aminobutyric acid has been reached by resolution of racemic mixtures with acylase [3, 4] or amidases [5], and asymmetric synthesis starting from 2-ketobutyric acid has been achieved using ω-transaminases [6, 7] or amino acid dehydrogenases [8]. Both (R)- and (S)-2-aminobutyric acid were also synthesized using an (R)- or (S)-selective ω-transaminase and isopropylamine as co-substrate [9]. Biosynthesis of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid (starting from the amino acid l-methionine) has been shown by co-immobilization of l-methionase and glutamate dehydrogenase on polyacrylamide or chitosan [1].

In contrast to in vitro synthesis with purified enzymes, whole-cell biocatalysts offer the advantage of simple and economical upstream processing as overheads for cell lysis, purification, and addition of co-factors are redundant. Low cost media and straightforward downstream processes further contribute to a more cost-effective production process. In vivo synthesis of (S)-2-ABA has been achieved via two different methods: (1) kinetic resolution of racemic 2-aminobutyric acid mixture with d-amino acid oxidase and ω-transaminase [10], and (2) asymmetric synthesis from l-threonine [11]. The latter setup used five E. coli strains containing five different genes.

(S)-2-aminobutanol is an important chiral building block for the chemical synthesis of the bacteriostatic anti-tuberculosis agent (S, S)-ethambutol [12]. Activity assays using Mycobacterium smegmatis have shown that the (S, S)-configured diastereomer of ethambutol [(S, S)-2,20-(ethylenediimino)-di-butanol] has the highest activity compared to all other measured derivatives, and is about 500 times more potent than the (R, R)-diastereomer [13]. As ethambutol shows ocular toxicity as a side effect [14], it is desirable to keep the therapeutic dose as low as possible. Therefore, it is crucial to apply the potent (S, S)-configured diastereomer exclusively. Several approaches have been developed to achieve chemical synthesis of enantiopure (S, S) ethambutol; e.g. resolution of racemic (S)-2-aminobutanol [15, 16]; use of palladium to accomplish regio-and stereo-selective epoxide opening [17]; use of l-methionine as chiral starting material [18, 19]; and introduction of protection groups during synthesis [20, 21].

The application of engineered microorganisms for production of chemical building blocks with very high enantiomeric purity may help to improve the supply with cost-efficient active pharmaceutical compounds and, in contrast to chemical synthesis, no additional steps or protection groups are necessary. Increasingly, metabolic engineering and biotechnology are providing sustainable and cost-efficient production of precursors for a variety of pharmaceuticals [22–25].

To our knowledge, (S)-2-aminobutyric acid has not been produced in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and (S)-2-aminobutanol has not yet been produced in any engineered microorganism. Here, we have explored the possibilities of using the well-known GRAS microorganism S. cerevisiae for biosynthesis of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid and subsequent production of (S)-2-aminobutanol. We demonstrate the in vivo production, in S. cerevisiae, of enantiopure (S)-2-aminobutyric acid and (S)-2-aminobutanol.

Results

Production of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid

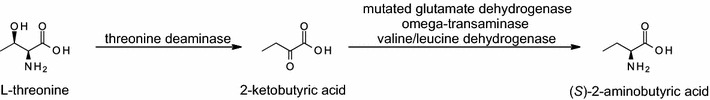

We have expanded the metabolic capacity of S. cerevisiae to generate (S)-2-aminobutyric acid ((S)-2-ABA) by introducing two heterologous enzymatic steps. Biosynthesis of this non-natural amino acid starts via deamination of l-threonine into the achiral intermediate 2-ketobutyric acid. This keto acid becomes then aminated in a second enzymatic step to yield (S)-2-ABA (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pathway from l-threonine to (S)-2-aminobutyric acid

Yeast-endogenous enzymes CHA1 and/or ILV1 in principal can execute this first enzymatic step. Regulation of the corresponding encoding genes occurs in part at the promoter level: to overcome this regulation the coding sequences have been functionally linked to constitutive promoters. An alternative strategy using heterologous enzymes for this first step was also employed. We selected three heterologous threonine deaminases derived from Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Solanum lycopersicum.

Based on the results from Zhang and co-workers we selected three mutated glutamate dehydrogenases (two from S. cerevisiae and one from E. coli) for the second enzymatic step [26]. In addition, we assessed two different leucine dehydrogenases (from B. cereus and B. flexus), and a valine dehydrogenase (from S. fradiae) as putative enzymes for the amination step from 2-ketobutyric acid to (S)-2-aminobutyric acid [8, 27].

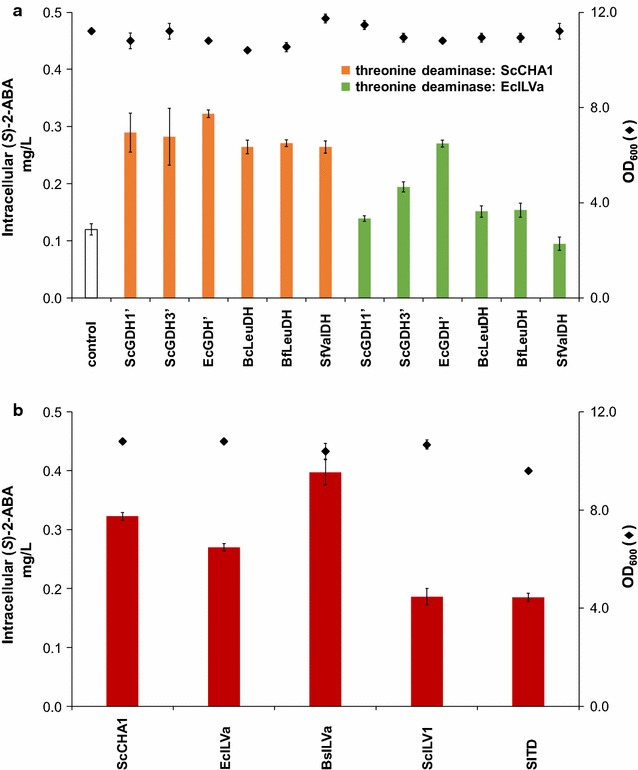

In total 15 S. cerevisiae strains were constructed, containing different combinations of threonine deaminases and dehydrogenases. Expressing yeast CHA1 under the control of the constitutively active GPD1 promoter, together with one of three heterologous enzymes for the second step of the pathway, or together with any of the three mutated glutamate dehydrogenases, yielded an accumulation of 0.32 ± 0.01 mg/L (S)-2-ABA upon 24 h of culture (Fig. 2a, orange bars). Significant shorter production times led to titers close to the limit of quantification. A longer production time enhanced the amount of (S)-2-ABA. For practical reasons a time of 24 h was chosen. Chiral HPLC analysis revealed the resultant (S)-2-ABA to be of high enantiopurity (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

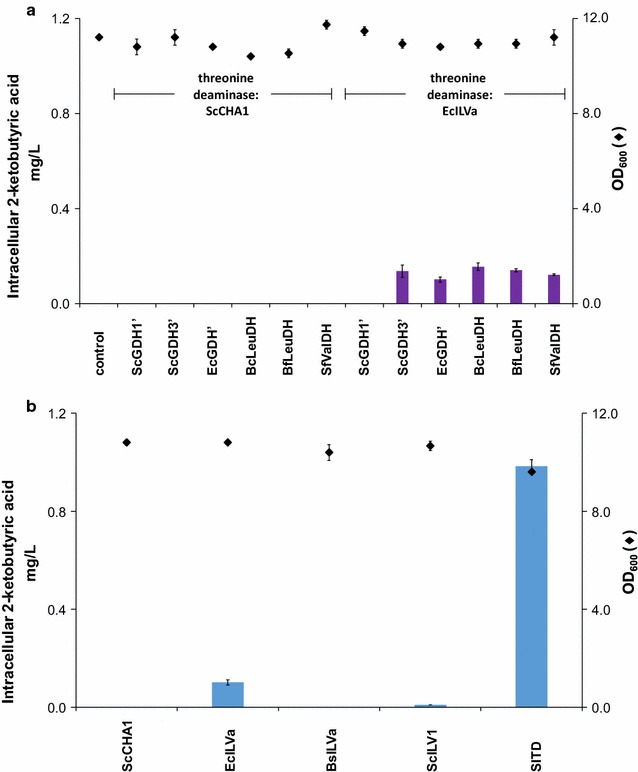

Fig. 2.

Intracellular accumulation of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid in S. cerevisiae expressing different enzyme combinations. a Either two different threonine deaminases (orange bars ScCHA1, green bars EcILVa) for the first step of the (S)-2-aminobutyric acid pathway were expressed in combination with either one of six heterologous enzymes for the second step of the pathway. Yeasts that did not express the pathway enzymes were included as control. b EcGDH’ for the second step of the pathway was expressed in combination with either one of five different threonine deaminases. Diamonds indicate OD600 after 24 h of growth (all data: mean ± SD, n = 3)

A less pronounced increase in (S)-2-ABA production was observed when using E. coli threonine deaminase (EcILVa) for the first enzymatic step (Fig. 2a, green bars). As the mutated E. coli GDH (EcGDH’) yielded the highest concentrations of (S)-2-ABA in combination with both ScCHA1 and EcILVa, we chose EcGDH’ to analyze the effect of the threonine deaminases derived from E. coli, B. subtilis, and S. lycopersicum on (S)-2-ABA production. Combining ILVa from B. subtilis with EcGDH’ led to the highest amount of (S)-2-ABA (0.40 ± 0.02 mg/L (S)-2-ABA, Fig. 2b). Expression of the heterologous enzymes had negligible effect on strain growth, as reflected by the relatively constant OD600 values after 24 h of culture.

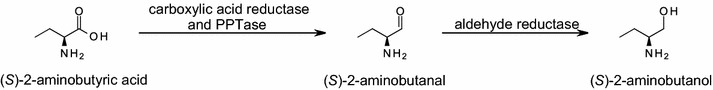

Extension of the heterologous pathway for production of (S)-2-aminobutanol

Enantiopure (S)-2-aminobutanol is a building block for the synthesis of the tuberculosis drug ethambutol. The chirality of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid is defined by the amine group, which makes it a well-suited intermediate for the biosynthesis of (S)-2-aminobutanol. Carboxylic acid reductases (CARs) and aldehyde reductases are enzymes that can perform the final enzymatic steps from (S)-2-aminobutyric acid to (S)-2-aminobutanol (Fig. 3) by reduction of the terminal carboxylic acid group of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid to an alcohol, leaving the stereo center of the molecule intact.

Fig. 3.

Pathway from (S)-2-aminobutyric acid to (S)-2-aminobutanol

We expressed one of four different carboxylic acid reductases (CARs) in combination with either a phosphopantetheinyl-transferase (PPTase) from M. smegmatis (for M. smegmatis CAR), or the one from B. subtilis (SFP) for all other CARs. CARs, when expressed in yeast, require a PPTase for activity [28]. Expression of a heterologous aldehyde reductase derived from E. coli in our strains facilitated reduction of the (S)-2-aminobutanal to the corresponding alcohol (Fig. 3). Initial supplementation with additional (S)-2-ABA (0.5 g/L) was tested, as we observed rather low production of (S)-2-ABA.

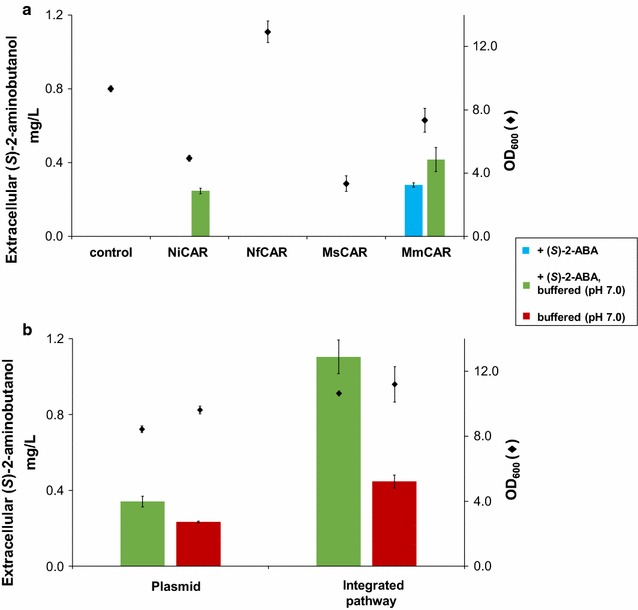

LC–MS analysis of pellets and supernatants from cells grown for 72 h in non-buffered conditions in shake flasks revealed quantifiable amounts of the target compound (S)-2-aminobutanol exclusively in the supernatant, and only in strains expressing the carboxylic acid reductase from Mycobacterium marinum (Fig. 4a, blue bar). Shorter production times led to titers of (S)-2-aminobutanol below the limit of quantification.

Fig. 4.

Extracellular accumulation of (S)-2-aminobutanol in S. cerevisiae. a Yeasts were transformed with plasmids harboring the sequences encoding a threonine deaminase and EcGDH’, in combination with different carboxylic acid reductases. PPTases were either from Mycobacterium smegmatis (for MsCAR) or from Bacillus subtilis (SFP) for all other CARs. The aldehyde reductase for the last step of the pathway was derived from E. coli. Engineered yeasts were incubated for 72 h in selective SC medium containing 0.5 g/L (S)-2-aminobutyric acid (+(S)-2-ABA). The medium was either buffered to pH 7 (green bars), or supplied unbuffered (blue bar). Supernatants were analyzed for (S)-2-aminobutanol production. b All five pathway genes (CAR from Mycobacterium marinum) were integrated into chromosome XI-2. Yeasts were incubated for 72 h in selective SC medium buffered to pH 7, and were either supplied with 0.5 g/L (S)-2-aminobutyric acid (green bars), or were grown without additional (S)-2-aminobutyric acid supply (red bars). Diamonds indicate OD600 after 72 h of growth (all data: mean ± SD, n = 3)

Adjusting the culture medium to pH 7 boosted production levels. The neutral pH resulted in a significant increase of (S)-2-aminobutanol production in strains expressing M. marinum CAR (MmCAR). In those strains, we determined approximately 1.5-fold more (S)-2-aminobutanol under pH-adjusted growth conditions. Moreover, the strain expressing CAR from Nocardia iowensis (NiCAR) produced (S)-2-aminobutanol in quantifiable amounts when buffered to pH 7 (Fig. 4a, green bars). Integration of all pathway genes, including the CAR from M. marinum and its accessory protein SFP, resulted in an approximate threefold higher level of (S)-2-aminobutanol production compared with episomal expression of the pathway genes (Fig. 4b, green bars). Even without (S)-2-ABA supplementation, production levels of (S)-2-aminobutanol reached 0.45 ± 0.03 mg/L (Fig. 4b, red bars).

Increasing titers of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid

As (S)-2-aminobutyric acid is critical for production of (S)-2-aminobutanol, we focused on boosting the biosynthesis of this compound. To investigate the kinetic coupling of the two heterologous enzymatic steps of the (S)-2-ABA pathway, we first determined the amount of 2-ketobutyric acid in strains previously analyzed for (S)-2-ABA production (Fig. 2). Combining ScCHA1 with any of the six enzymes for the second step of the pathway does not lead to detectable amounts of 2-ketobutyric acid. In contrast, combining EcILVa with any of the six enzymes for the second enzymatic step resulted in 2-ketobutyric acid accumulation in the range of 0.1 mg/L, except for the combination EcILVa and ScGDH1′ where no 2-ketobutyric acid could be detected (Fig. 5a). The highest accumulation of 2-ketobutyric acid (0.98 ± 0.03 mg/L) was observed with threonine deaminase (SlTD) from S. lycopersicum combined with EcGDH’ (Fig. 5b). We concluded that in the case of the S. lycopersicum threonine deaminase, a more efficient enzymatic coupling between threonine deaminase and glutamate dehydrogenase may improve conversion of l-threonine to (S)-2-ABA.

Fig. 5.

Intracellular accumulation of 2-ketobutyric acid upon 24 h of growth in selective SC medium. a Two different enzymes for the first step of the (S)-2-aminobutyric acid pathway were expressed (ScCHA1 and EcILVa) in combination with either one of six heterologous enzymes for the second step of the pathway. In case ScCHA1 was expressed or yeasts were not engineered (control), accumulation of 2-ketobutyric acid was below the limit of quantification. b EcGDH’ for the second step of the pathway is expressed in combination with either one of five different threonine deaminating enzymes. Diamonds indicate OD600 after 24 h of growth (all data: mean ± SD, n = 3)

Optimizing enzymatic coupling

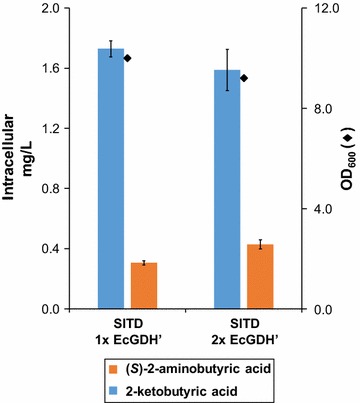

Next, we sought to optimize biosynthetic titers through improved enzymatic coupling. First, we introduced an additional copy of a mutated glutamate dehydrogenase from E. coli and combined it with the deaminase derived from S. lycopersicum. This genetic modification lead to 1.4-fold more (S)-2-ABA (Fig. 6, orange bars). The concentration of 2-ketobutyric acid (Fig. 6, blue bars) is slightly diminished in the strain expressing two copies of EcGDH’, indicating that: (1) increasing the enzymatic capacity of the second enzyme indeed improves coupling of the two heterologous enzymes, and (2) additional optimization of coupling may further enhance (S)-2-ABA production.

Fig. 6.

Intracellular accumulation of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid and 2-ketobutyric acid in S. cerevisiae, expressing threonine deaminase SlTD, and one or two copies of mutated glutamate dehydrogenase EcGDH’. Yeasts expressing SlTD were co-transformed with either one or two copies of the mutated glutamate dehydrogenase derived from E. coli. Concentrations of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid (orange) and 2-ketobutyric acid (blue) were analyzed in the yeast pellets upon 24 h of growth in batch culture. Diamonds indicate OD600 after 24 h of growth (all data: mean ± SD, n = 3)

Increasing (S)-2-aminobutyric acid production by feeding l-threonine

l-Threonine is the starting molecule for enzymatic synthesis of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid. The concentration of l-threonine in our synthetic complete (SC) medium is 76 mg/L. When measured intracellularly upon 24 h of shake flask growth, the intracellular concentration of l-threonine is about 1.5–3 mg/L l-threonine (not shown). We hypothesized that elevating the l-threonine concentration may well influence (S)-2-ABA production.

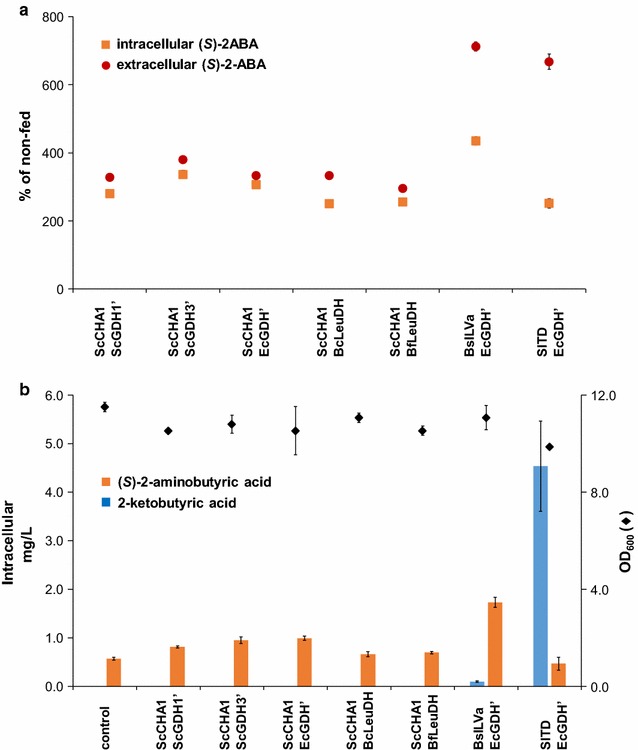

The addition of 1.0 g/L of l-threonine resulted in intracellular concentrations of l-threonine of 13–15 mg/L (8 mg/L for the combination SlTD and EcGDH’) which led to 250 to 435% intracellular (S)-2-ABA production in all evaluated strains (Fig. 7a). The effect is even more pronounced for extracellular concentrations of (S)-2-ABA (up 300–710%) in threonine–fed strains (for absolute values see Additional file 1: Figure S2). Obviously l-threonine feeding impacts not only on endogenous accumulation of (S)-2-ABA but also on secretion of the compound. Additional l-threonine feeding leads to a significant elevation of intracellular 2-ketobutyric acid in the strain expressing S. lycopersicum threonine deaminase (4.6-fold, in comparison to the non-fed conditions). The higher amounts of 2-ketobutyric acid did not translate into higher amounts of (S)-2-ABA, again suggesting a bottleneck at the second enzymatic step. The absolute concentration of (S)-2-ABA in the best producer strain (BsILVa + EcGDH’) reached 1.73 ± 0.10 mg/L (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7.

Impact of l-threonine feeding on accumulation of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid and 2-ketobutyric acid. Yeasts were transformed with the gene combinations indicated on the x-axis’. Clones were grown for 24 h in selective medium fed with 1.0 g/L l-threonine. a (S)-2-Aminobutyric acid amounts accumulating in l-threonine-fed yeasts, shown as a percentage of non-fed yeasts; orange squares: intracellular (S)-2-aminobutyric acid, red circle: extracellular (S)-2-aminobutyric acid. b Absolute intracellular concentrations of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid (orange bars) and 2-ketobutyric acid (blue bars) in l-threonine fed yeasts. Diamonds in b indicate OD600 after 24 h of growth (all data: mean ± SD, n = 3)

Upregulation of l-threonine metabolism in S. cerevisiae by mutating HOM3 or deletion of GLY1

Mutation of aspartate kinase HOM3

Saccharomyces cerevisiae can synthesize l-threonine via a pathway that starts with the amino acid l-aspartate, and involves five enzymes (HOM3, HOM2, HOM6, THR1, and THR4) that assemble the amino acid via the four intermediates l-4-aspartyl-phosphate, l-aspartate-4-semialdehyde, l-homoserine, and O-phospho-l-homoserine [29]. It is known that l-threonine inhibits aspartate kinase activity in S. cerevisiae [30] and several mutant strains that overproduce l-threonine have been isolated which all contained a mutation in the aspartate kinase gene HOM3 that led to insensitivity towards feedback inhibition [31, 32].

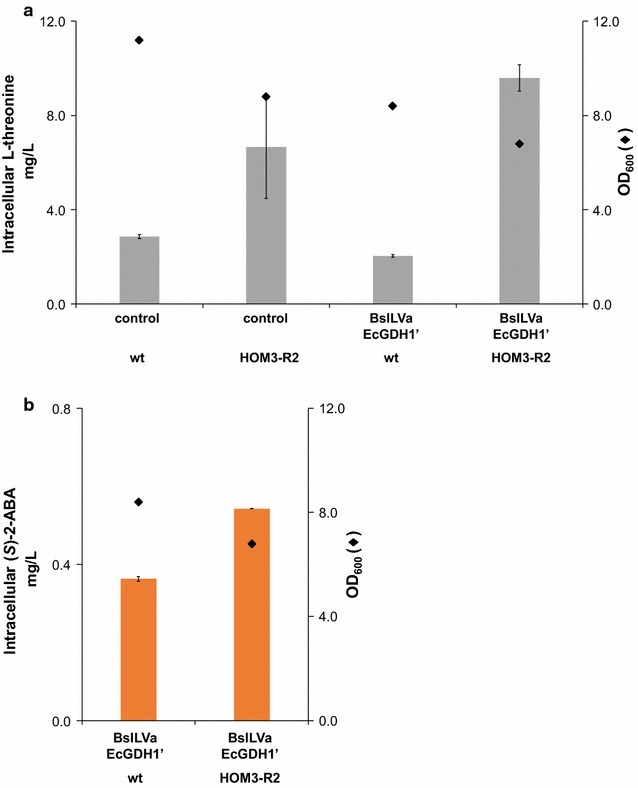

We introduced such a mutated HOM3 gene via a 2μ plasmid into our yeast strains. This led to 2.3-fold higher l-threonine concentrations in strains not expressing the (S)-2-ABA pathway genes, and to a 4.7-fold increase in strains expressing the pathway genes (Fig. 8a). The higher amount of intracellular l-threonine also boosted the concentration of intracellular (S)-2-ABA 1.5-fold (Fig. 8b). As the boost in (S)-2-ABA production upon expression of the mutated HOM3 variant is accompanied by an impaired growth, the relative accumulation of (S)-2-ABA compared to the number of yeast cells is even higher.

Fig. 8.

a Intracellular l-threonine concentrations in yeasts expressing HOM3-R2. Yeasts, either engineered for (S)-2-aminobutyric acid production (BsILVa + EcGDH’), or non-engineered yeasts, were transformed with a 2µ plasmid harboring the sequence encoding for mutated HOM3 (HOM3-R2) or they were transformed with an empty plasmid (wt). Intracellular l-threonine concentrations were analyzed as described in “Methods”. Diamonds indicate OD600 after 24 h of growth (all data: mean ± SD, n = 3). b Intracellular (S)-2-aminobutyric acid concentrations in yeasts expressing HOM3-R2. Yeasts engineered for (S)-2-aminobutyric acid production (BsILVa + EcGDH’) were transformed with a 2µ plasmid harboring the sequence encoding for mutated HOM3 (HOM3-R2) or they were transformed with an empty plasmid (wt). Intracellular (S)-2-aminobutyric acid concentrations were analyzed as described in “Methods”. Diamonds indicate OD600 after 24 h of growth (all data: mean ± SD, n = 3)

Deletion of threonine aldolase (GLY1)

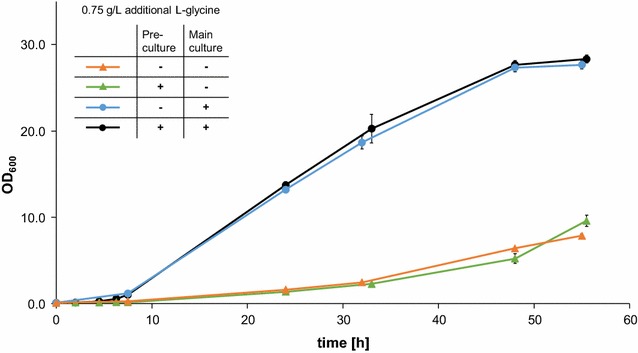

We tried another strategy to enhance the concentration of l-threonine, the deletion of the gene encoding for l-threonine aldolase GLY1. This enzyme irreversibly converts l-threonine into l-glycine [33]. We deleted the entire open reading frame of the unique GLY1 locus on chromosome V. Our Δgly1 deletion strain was viable, albeit with impaired growth characteristics as also described previously [34, 35]. Routinely we grew the Δgly1 deletion strain in medium that was supplied with 0.75 g/L l-glycine in the medium. It was not critical whether the pre-culture was prepared in glycine-containing medium or not. In both cases, the OD600 after 55 h of growth in shake flasks reached values above 27. However, omitting l-glycine in the main culture led to a massive growth retardation (OD600 below 7), as shown in Fig. 9. Therefore, transformation of plasmids into the Δgly1 deletion strain and growth of the strains was routinely done in l-glycine supplemented medium. GLY1 wildtype and Δgly1 deleted strains were transformed with two enzyme combinations, BsILVa + EcGDH’ and SlTD + EcGDH’.

Fig. 9.

Growth of Δgly1 deletion strain. Δgly1 deletion strains were grown in selective medium either containing additional glycine (0.75 g/L l-glycine), or devoid of any additional glycine. Black pre-culture and main culture contain l-glycine, blue pre-culture contains no l-glycine, main culture contains l-glycine, green pre-culture contains l-glycine, main culture contains no l-glycine, orange no l-glycine in pre-culture nor in main culture

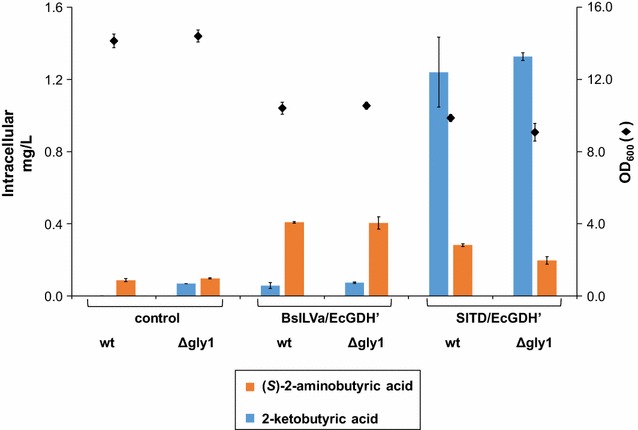

The deletion of GLY1 does not seem to have an effect on the amount of both extra- and intracellular l-threonine (Additional file 1: Figure S3), except for the SlTD + EcGDH’ strain, which produces roughly two times more l-threonine than the other strains. The elevated concentration of l-threonine in the SlTD + EcGDH’ Δgly1 deletion strain does not translate into an elevated concentration of 2-ketobutyric acid or (S)-2-aminobutyric acid (Fig. 10). In strains expressing SlTD + EcGDH’ (both GLY1 wildtype and Δgly1 deletion strain) the amount of 2-ketobutyric acid exceeds 1.2 mg/L. The concentration of (S)-2-ABA does not exceed 0.3 mg/L in those strains. The concentration of 2-ketobutyric acid is significantly lower in the BsILVa + EcGDH’ strains, suggesting tight coupling of 2-ketobutyric acid generation and subsequent conversion to (S)-2-aminobutyric acid, as observed previously.

Fig. 10.

Intracellular accumulation of 2-ketobutyric acid and (S)-2-aminobutyric acid in S. cerevisiae not expressing GLY1. Wildtype and Δgly1 deletion yeast strains were either engineered for (S)-2-aminobutyric acid production (BsILVa + EcGDH’ or SlTD + EcGDH’), or they contained the empty plasmids (control). Concentrations of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid (orange bars) and 2-ketobutyric acid (blue bars) were analyzed in the yeast pellets upon 24 h of growth in batch culture. Diamonds indicate OD600 after 24 h of growth (all data: mean ± SD, n = 3)

Discussion

In this study, we describe: (1) the production of enantiopure (S)-2-aminobutyric acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by expressing two heterologous genes that convert l-threonine to (S)-2-aminobutyric acid; (2) the prolongation of the pathway from (S)-2-aminobutyric acid to (S)-2-aminobutanol by expressing three additional heterologous genes. Both compounds are of considerable interest due to their potential use for the production of the chiral anti-epileptic drugs levetiracetam and brivaracetam, as well as for the production of the chiral anti-tuberculosis drug ethambutol. The latter one figures on the WHO list of essential medicines.

Pathway to (S)-2-aminobutyric acid

We show that expression of B. subtilis threonine deaminase, combined with expression of a mutated form of E. coli glutamate dehydrogenase leads to the production of 0.40 ± 0.02 mg/L of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid in shake flask-grown S. cerevisiae cells. The higher production in E. coli achieved by Zhang and co-workers [26] is perhaps due to the special properties of the E. coli strain employed, which can produce 8 g/L l-threonine from 30 g/L glucose. Nevertheless, we rationalize that yeast is indeed a superior production host for (S)-2-aminobutanol production, as it displays higher robustness and considerable tolerance against harsh fermentation conditions. Yeast is also more resistant towards exposure to (S)-2-aminobutanol (Additional file 1: Figure S4). Moreover, the fermentation of yeasts is easily implemented into existing ethanol productions plants, and there are no issues with phage contamination. S. cerevisiae is classified as GRAS (“generally regarded as safe”) organism; thereby further facilitating industrial scale up.

We have explored a variety of strategies to increase the yield of (S)-2-ABA production in our yeast strains; first by evaluating the effect of adding a second copy of mutated glutamate dehydrogenase. When analyzing intracellular 2-ketobutyric acid concentrations we realized that in yeasts containing the enzyme combinations threonine deaminase from S. lycopersicum and mutated glutamate dehydrogenase from E. coli, a considerable amount of 2-ketobutyric acid (0.98 ± 0.03 mg/L) was not converted to (S)-2-aminobutyric acid. This may be due to the relatively low Km value of this heterologous l-threonine deaminase (SlTD: 0.25 mM, [36]). In contrast, the deaminase from E. coli has a Km of 11 mM (if AMP is present, otherwise it is 91 mM) [37], and the one from B. subtilis is 9.6 mM [38]. The amount of l-threonine generated in the strains after 24 h of growth in shake flasks reaches approximately 2 mg/L (~0.017 mM intracellular l-threonine). This low intracellular l-threonine concentration can be more efficiently converted to 2-ketobutyric acid by SlTD as this deaminase has a lower Km than the other threonine deaminases.

It is expected that the obvious massive increase in production of 2-ketobutyric acid by SlTD would lead to a substantial elevation of (S)-2-ABA accumulation, especially taking into account the relatively high Km (8.4 mM) of EcGDH’ [26]. As this was not the case, the enzymatic capacity of E. coli glutamate dehydrogenase was enhanced by expressing a second copy of this enzyme in the yeast. The modification elevated the amount of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid, but a considerable amount of 2-ketobutyric acid remained. This indicates that production of (S)-2-ABA may not be massively tunable, probably due to substrate inhibition of the E. coli dehydrogenase [39]. This hypothesis is further substantiated by the fact that in threonine fed strains expressing SlTD and EcGDH’, 2-ketobutyric acid production was elevated to above 4.54 ± 0.93 mg/L, without increasing intracellular (S)-2-aminobutyric acid accumulation.

Feeding with l-threonine elevated intracellular (S)-2-ABA accumulation in strains expressing the enzyme combination BsILVa and EcGDH’ more than fourfold compared to non-fed strains.

The conversion yield of l-threonine to (S)-2-ABA (no additional l-threonine) was 36% compared to 22% with additional l-threonine in the medium, indicating that l-threonine is consumed by enzymatic and/or efflux reactions triggered by the elevated intracellular l-threonine concentration.

Interestingly, in contrast to the non-fed strains, most of the de novo (S)-2-ABA was found in the supernatant, indicating that (S)-2-ABA was either actively secreted, or passively diffused. l-Threonine strongly induces the broad-specificity amino acid permease AGP1 [40, 41], suggesting that this permease may not only mediate uptake of l-threonine, but also increase (S)-2-ABA efflux. Another putative mediator of (S)-2-ABA efflux could be the internal-membrane transporter AQR1. This transporter is involved in excretion of excess amino acids by exocytosis [42], suggesting that it may also secrete (S)-2-ABA.

As feeding with l-threonine significantly boosted (S)-2-ABA production, we hypothesized that upregulation of threonine anabolism may enhance generation of (S)-2-ABA in our engineered strains.

The G425D mutation of aspartate kinase HOM3, previously described to abrogate feedback-inhibition, led to a significant boost of both intracellular l-threonine and (S)-2-aminobutyric acid. Recently, Mülleder et al. analyzed the amino acid metabolome of S. cerevisiae upon systematic gene deletions [43]. They found that deletion of FPR1 (a peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerase) enhanced intracellular l-threonine by around 2.5-fold. This increase is in good accordance with our HOM3 mutant, indicating that FPR1 may indeed regulate feedback inhibition of HOM3 as previously suggested [31, 44]. l-Threonine and (S)-2-aminobutyric acid were also detected at higher extracellular levels upon expression of the mutated form of HOM3. Those data indicate that the endogenous l-threonine supply is indeed critical for (S)-2-ABA production.

The l-threonine aldolase GLY1 of S. cerevisiae catalyzes the cleavage of l-threonine into l-glycine and acetaldehyde. In contrast to expectations, no elevated l-threonine levels were detected in Δgly1 deletion strains. The comparable concentrations of l-threonine accumulated in wild type and Δgly1 deletion strains led us to conclude that feedback inhibitory mechanisms are active e.g. aspartate kinase HOM3. Our Δgly1 deletion strains showed strongly impaired growth characteristics compared to the wildtype strains (four to fivefold lower). These growth characteristics are similar to the ones previously reported [34], suggesting that GLY1 is important for l-glycine synthesis.

Pathway to (S)-2-aminobutanol

Here, we report production of the non-natural compound (S)-2-aminobutanol in S. cerevisiae. The highest production levels were observed in strains expressing (apart from the enzymes forming the (S)-2-aminobutyric acid pathway) M. marinum carboxylic acid reductase and an aldehyde reductase from E. coli. The level of 0.42 ± 0.07 mg/L (S)-2-aminobutanol could be reached by buffering the growth medium to pH 7. Valli and co-workers [45] demonstrated previously that yeast cells grown at pH 7 are viable and adjust their endogenous pH accordingly. Furthermore, CARs work predominantly at basic pH conditions [46]. We hypothesized therefore that adjusting the culture medium to pH 7 would increase intracellular pH and lead to elevated activity of heterologous CARs. Our results support this hypothesis. Without pH adjustment of the surrounding medium, the extracellular pH drops to pH 2.5 in stationary phase [45] that would correspond to an intracellular pH around 5, which is not suitable for CAR activity [46].

Interestingly, integration of the entire pathway into a single position of chromosome XI significantly enhanced production of (S)-2-aminobutanol, even though promoters and terminators of the heterologous genes were identical to those used for episomal expression. Growth of strains expressing the plasmid-encoded pathway was however significantly lower than yeast strains expressing the genome-integrated pathway. These results indicate that plasmid maintenance is perhaps at the expense of heterologous pathway expression and product generation. However, strains expressing the pathway also displayed retarded growth. One explanation for impaired cellular growth and proliferation are the reductive modifications of intracellular fatty acids or reduction of fatty acids that form parts of membrane lipids by CARs [46, 47]. Ultimately, compartmentalization of the heterologous pathway might be a valuable approach for efficient orthologous production of this non-natural chiral compound.

Previous studies have demonstrated that substrates with an amine group at the α-position are scarcely accepted by carboxylic acid reductases [48], suggesting that production of (S)-2-aminobutanol may be further boosted by optimizing the substrate binding site of the carboxylic acid reductase.

Co-factor supply in the pathway

Threonine deaminases are pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP) dependent, with the PLP co-factor remaining in the active site and being regenerated during the reaction cycle [49]. In S. cerevisiae PLP levels are elevated when the yeasts are grown under thiamine deficient conditions as the synthesis of PLP is inhibited by the presence of thiamine [50]. Enhanced conversion in whole-cell biocatalysis experiments employing PLP-dependent ω-transaminases and addition of PLP or preceding growth in thiamine-deficient medium have been shown [50, 51].

Most of the enzymes in the pathway to (S)-2-aminobutanol require NADPH. Elevated NADPH supply should boost production of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid and (S)-2-aminobutanol, as shown previously for several other cofactor-dependent enzymatic reactions [52–55]. NADPH is generated predominantly by the pentose phosphate pathway. A recent study has shown that overexpression of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase ZWF1, the enzyme that catalyzes the first step of the pentose phosphate pathway, or overexpression of NADH kinase POS5 leads to a higher of NADPH-dependent heterologous production of β-carotene in S. cerevisiae [56]. In future studies, we will use the described approaches to enhance the efficiency of the heterologous pathway.

Conclusions

We have successfully assembled a heterologous metabolic pathway in S. cerevisiae to produce the non-proteinogenic amino acid (S)-2-aminobutyric acid and the purely synthetic compound (S)-2-aminobutanol. To our knowledge (S)-2-aminobutanol has never previously been produced biosynthetically. Our studies expand the spectrum of synthetic biology towards the biosynthesis of e.g. pharmaceutical compounds by entirely novel and sustainable means.

Methods

Chemicals and media

l-threonine, 2-ketobutyric acid, (R)- and (S)-aminobutyric acid, (R) and (S)-2-aminobutanol were bought from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie AG (Steinheim, Germany). Yeast Extract Peptone (YPD) medium with 20 g/L glucose was used for growth of the wildtype strain prior to transformation and both bought from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie AG. Synthetic complete (SC) drop out medium (Formedium LTD, Hustanton, England) with 6.7 g/L yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and ammonium sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie AG), and 20 g/L glucose (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie AG) was used for pre- and main cultures. LB medium for growth of E. coli was supplied from Carl Roth GmbH + Co. KG (Karlsruhe, Germany).

Primers, genes, and strains

Primers used in this study were supplied by Microsynth AG (Balgach, Switzerland) and are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1. Genes used in this study are listed in Table 1. Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains generated throughout this study are listed in Table 2. All yeast strains were stored in 25% glycerol at −80 °C.

Table 1.

Expression cassettes and plasmids

| Feature | Plasmid type | ORF origin | Description | Uniprot number | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pGPD1-ScCHA1-tCYC1 | Entry vector | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Threonine deaminase | P25379 | This study |

| pGPD1-EcILVa-tCYC1 | Entry vector | Escherichia coli | Threonine deaminase | P04968 | [26] |

| pGPD1-SlTD-tCYC1 | Entry vector | Solanum lycopersicum | Threonine deaminase | P25306 | [61] |

| pGPD1-ScILV1-tCYC1 | Entry vector | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Threonine deaminase | P00927 | This study |

| pGPD1-BsILVa-tCYC1 | Entry vector | Bacillus subtilis | Threonine deaminase | P37946 | [26] |

| pPGK1-ScGDH1′-tADH2 | Entry vector | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Glutamate dehydrogenase (K74V/T177S) | P07262 | This study |

| pPGK1-ScGDH3′-tADH2 | Entry vector | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Glutamate dehydrogenase (K75V/T178S) | P39708 | This study |

| pPGK1-EcGDH’-tADH2 | Entry vector | Escherichia coli | Glutamate dehydrogenase (K92V/T195S) | P00370 | [26] |

| pPGK1-BcLeuDH-tADH2 | Entry vector | Bacillus cereus | Leucine dehydrogenase | C2RD20 | [8] |

| pPGK1-BfLeuDH-tADH2 | Entry vector | Bacillus flexus | Leucine dehydrogenase | A0A0L1MCT3 | This study |

| pPGK1-SfValDH-tADH2 | Entry vector | Streptomyces fradiae | Valine dehydrogenase | P40176 | [27] |

| pTEF1-NiCAR-tENO2 | Entry vector | Nocardia iowensis | Carboxylic acid reductase | Q6RKB1 | [28] |

| pTEF1-NfCAR-tENO2 | Entry vector | Nocardia farcinica | Carboxylic acid reductase | Q5YY80 | This study |

| pTEF1-MmCAR-tENO2 | Entry vector | Mycobacterium marinum | Carboxylic acid reductase | B2HN69 | [46] |

| pTEF1-MsCAR-tENO2 | Entry vector | Mycobacterium smegmatis | Carboxylic acid reductase | L0IYJ8 | [48] |

| pTEF2-BsSFP-tPGI1 | Entry vector | Bacillus subtilis | Phosphopantetheinyl transferase | P39135 | [46] |

| pTEF2-MsPPTase-tPGI1 | Entry vector | Mycobacterium smegmatis | Phosphopantetheinyl transferase | L0ITG8 | [48] |

| pPDC1-EcALR-tFBA1 | Entry vector | Escherichia coli | Aldehyde reductase | A0A094VUC2 | This study |

| pURA3-ScURA3-tURA3 | Entry vector | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Uracil marker | – | – |

| ARS/CEN | Entry vector | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Origin of replication | – | – |

| pPYK1-tTEF1 | 2 micron | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Vector only | – | – |

| pTEF2-tPGI1 | ARS/CEN | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Vector only | – | – |

| pPYK1-ScHOM3-R2-tTEF1 | 2 micron | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Aspartate kinase (G425D) | P10869 | [31, 32] |

| pTEF2-EcGDH’-tPGI1 | ARS/CEN | Escherichia coli | Glutamate dehydrogenase (K92 V/T195S) | P00370 | [26] |

Table 2.

Strains

| Strains | Description | Selection marker | Replication origin/integration site |

|---|---|---|---|

| EVST20590 | Contains expression cassettes of ScCHA1 and ScGDH1′ | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST20591 | Contains expression cassettes of ScCHA1 and ScGDH3′ | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST20592 | Contains expression cassettes of ScCHA1 and EcGDH’ | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST20879 | Contains expression cassettes of ScCHA1 and BcLeuDH | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST20880 | Contains expression cassettes of ScCHA1 and BfLeuDH | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST20881 | Contains expression cassettes of ScGDH1′ and EcILVa | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST20882 | Contains expression cassettes of ScGDH3′ and EcILVa | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST20883 | Contains expression cassettes of EcGDH’ and EcILVa | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST20884 | Contains expression cassettes of EcILVa and BcLeuDH | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST20885 | Contains expression cassettes of EcILVa and BfLeuDH | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST21351 | Contains expression cassettes of ScCHA1 and SfValDH | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST21352 | Contains expression cassettes of EcILVa and SfValDH | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST21478 | Contains expression cassettes of ScCHA1, EcGDH’, NiCAR, EcALR, and BsSFP | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST21479 | Contains expression cassettes of ScCHA1, EcGDH’, NfCAR, EcALR, and BsSFP | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST21542 | Control strain with empty entry vectors | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST22605 | Contains expression cassettes of BsILVa and EcGDH’ | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST22606 | Contains expression cassettes of ScILV1 and EcGDH’ | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST22608 | Contains expression cassettes of SlTD and EcGDH’ | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST22609 | Contains expression cassette of ScHOM3-R2 | LEU2 | 2 micron |

| EVST22610 | Contains expression cassettes of BsILVa, EcGDH’, and ScHOM3-R2 | URA3 (BsILVa, EcGDH’), LEU2 (ScHOM3-R2) | ARS/CEN (BsILVa, EcGDH’) 2 micron (ScHOM3-R2) |

| EVST22615 | Contains expression cassettes of EcILVa, EcGDH’, MsCAR, MsPPTase, and EcALR | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST22837 | Contains expression cassette of SlTD and two EcGDH’ expression cassettes | URA3, HIS3 | ARS/CEN both |

| EVST22857 | Deletion of GLY1 ORF | – | – |

| EVST23406 | Deletion of GLY1 ORF Contains expression cassettes of BsILVa and EcGDH’ |

URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST23407 | Deletion of GLY1 ORF Contains expression cassettes of SlTD and EcGDH’ |

URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST24185 | Contains expression cassettes of BsILVa, EcGDH’, MmCAR, EcALR, and BsSFP | URA3 | ARS/CEN |

| EVST25556 | Control strain with empty plasmid | LEU2 | 2 micron |

| EVST25557 | Contains expression cassettes of BsILVa, EcGDH’, and empty plasmid | URA3 (BsILVa, EcGDH’), LEU2 | ARS/CEN (BsILVa, EcGDH’) 2 micron (empty plasmid) |

| EVST25635 | Contains expression cassettes of SlTD, EcGDH’, and empty plasmid | URA3 (BsILVa, EcGDH’), HIS3 | ARS/CEN both |

| EVST27022 | Contains expression cassettes of BsILVa, EcGDH’, MmCAR, EcALR, and BsSFP | URA3 | integrated into Chromosome XI-2 |

Molecular biology

Plasmid DNA was prepared using the ZR Plasmid Miniprep-Classic Kit (Zymo Research Corp, Irvine, CA, USA). Competent E. coli NEB 10-β cells (New England Biolabs, Herts, United Kingdom) were used for all cloning steps. Restriction enzymes were supplied from New England Biolabs (Herts, United Kingdom). T4 ligase was from Agilent (Santa Clara, CA, USA), and thermostable DNA polymerase iProof™ High-Fidelity was purchased from BioRad (Hercules, CA, USA). dNTPs were from Roche Diagnostics GmbH (Mannheim, Germany). PCR reactions were performed in a FlexCycler2 (Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany) using the appropriate cycling conditions. PCR products were purified using the DNA Clean & Concentrator-5 Kit from Zymo Research Corp (Irvine, CA, USA). Accuracy of genetic constructs was verified by sequencing (Microsynth AG, Balgach, Switzerland).

Plasmid construction, gene deletion, and integration

Most of the genes used in this study were supplied in plasmids as yeast-codon optimized versions of the original genes (GeneArt, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Genes were released from the plasmids, supplied by the manufacturer, by HindIII/SacII digestions prior to ligation into our pre-cut entry vectors. Our entry vectors contain different combinations of promoters and terminators, which are flanked by 60 bp homologous regions (“linkers”) that enable the assembly of multiple expression cassettes in vivo by homologous recombination [57, 58]. Accessory entry vectors dispose of autonomously replicating sequences, centromere regions, and auxotrophic markers as described in Eichenberger et al. [59]. One-pot digestion of entry vectors by AscI releases the expression cassettes composed of (1) promoter-gene-terminator flanked by 60 bp linkers at the 5′ and 3′ end; (2) selection marker URA3 flanked by 60 bp linkers at the 5′ and 3′ end; and (3) replication origin ARS/CEN flanked by 60 bp linkers at the 5′ and 3′ end); or, for integration, two 560 bp homologous regions flanked by 60 bp linkers at the 5′ and 3′ sites. Released fragments were then transformed into the strains as described in the next paragraph.

Amplification of the plasmids containing the carboxylic acid reductase from Nocardia farcinica has been reported to be not feasible in E. coli (personal communication Esben H. Hansen). Therefore, the gene was ordered in two fragments, containing a 60 bp homologous region. The entire open reading frame was fused in vivo in yeast. Correct assembly was confirmed by PCR amplification and subsequent sequencing.

HOM3 was amplified from yeast genomic DNA in three parts. The three sequence stretches were fused by overlap extension PCR thereby removing the HindIII site and mutating glycine 425 to aspartic acid. The resulting entire PCR product was cut with HindIII and SacII, and inserted into a 2μ yeast expression plasmid.

The ORF encoding GLY1 was deleted by transformation of a PCR product encoding the marker LEU2 flanked by homologous regions upstream and downstream of the genomic GLY1 ORF. Successful deletion was confirmed by colony PCR.

The five pathway genes (BsILVa, EcGDH’, MmCAR, BsSFP, EcALR) were integrated by homologous recombination of the same cassettes as used for the episomal expression plasmid (described before), except that the centromere region was exchanged with the homologous region on chromosome XI-2 (noncoding region between FAT3 and MTR2).

Transformation and cell growth

Yeast transformation was performed using the lithium acetate method described in [60]. Transformed clones were grown on agar plates prepared with selective SC drop out medium. Single colonies from the plates were inoculated into 3 mL of selective liquid SC medium and grown overnight at 30 °C in a shaker (160 rpm). Main cultures (25 mL in 250 mL shake flasks) for production of (S)-2-ABA were inoculated at a starting OD600 of 0.1, and kept on the shaker at 30 °C for 24–72 h. The main cultures for (S)-2-aminobutanol were carried out in 24 deepwell plates (OD 0.1, 2.5 mL, 72 h, 30 °C, 300 rpm; Porvair, Norfolk, UK).

Extraction

Cell suspensions in 10 mL of growth medium were harvested by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 5 min. One millilitre of the supernatant was removed for analysis. The remaining cell pellet was resuspended in 1 mL water and added to a 2 mL screw cap tube containing 500 µL glass beads (0.5 mm, Huberlab, Aesch, Switzerland). Cell lysis was performed by a precellys 24 bead beater (Bertin technologies, Aix-en-Provence Cedex, France) for 3 cycles for 45 s with 60 s break. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (14,000 rpm, 5 min), and the supernatant was subjected to analyses.

Analyses

Stock solutions of (R)- and (S)-2-aminobutyric acid, l-threonine, 2-ketobutyric acid, and 2-aminobutanol (1 g/L) were prepared in water. Calibration standards of those compounds were prepared in the range of 31 μg/L–8 mg/L in water/acetonitrile 85:15.

Pellet extracts (150 μL) or supernatants (150 μL) were diluted into 850 μL of acetonitrile (in order to precipitate protein remainings), and centrifuged prior to injection.

Threonine, 2-ketobutyric acid, 2-aminobutyric acid, and 2-aminobutanol analysis

Samples were injected into an Acquity UPLC-TQD (Waters), equipped with an Aquity UPLC BEH Amide 1.7 μm 2.1 × 100 mm (Waters) column with two mobile phases. A: water with 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.15% formic acid, and B: acetonitrile with 2 mM ammonium formate and 0.05% formic acid. Separation was performed with a gradient ranging from 85 to 82% of mobile phase B for 3 min then to 60% B in 1 min at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. Then a washing step at 60% B for 1 min, followed by a reconditioning step of 1 min at 85% B, was carried out. 2-Ketobutyric acid was detected with SIR mode following the mass 101.1 in ESI- with a cone voltage of 20 V. 2-Aminobutanol, 2-aminobutyric acid, and l-threonine were detected with MRM mode with the transitions 90.1 > 55, 104.1 > 58, 120 > 74 in ESI+ , cone voltages of 18, 16 and 16 V and collision voltages of 12 V for all compounds.

2-Aminobutyric acid chiral analysis

Samples were injected on an Aquity UPLC-TQD (Waters) equipped with an Astec Chirobiotic T 250 × 4.6 mm column (Sigma) with water/methanol/formic acid 30:70:0.02 isocratic mobile phase and 1 mL/min flow during 16 min. (R)- and (S)-aminobutyric acid were detected with MRM mode with the transition 104.1 > 58.0 in ESI+ , a cone voltage of 16 V and collision voltage of 12 V (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Authors’ contributions

NW carried out all strain constructions, experiments, extractions, and drafted the manuscript. AH established the analysis methods and analyzed all samples. LL performed initial studies for the synthesis of (S)-2-ABA. NW and HH designed and coordinated the study. HH reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. Nick Turner for helpful discussions on carboxylic acid reductases, and for suggestions on heterologous pathway prolongation, Dr. Bettina Nestl, Dr. Philipp Scheller, and Maike Lenz for supplying genes encoding imine reductases. We are grateful to Dr. Martina Geier and Prof. Anton Glieder for continuous support of the project. Finally, we thank Dr. Luke Simmons for proofreading the manuscript. This study was financed by the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) Joint Undertaking project CHEM21 under Grant Agreement No 115360.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- (S)-2-ABA

(S)-2-aminobutyric acid (synonyms: α-aminobutyric acid, l-homoalanine)

- ScCHA1

Saccharomyces cerevisiae threonine deaminase CHA1

- EcILVa

Escherichia coli threonine deaminase ILVa

- BsILVa

Bacillus subtilis threonine deaminase ILVa

- ScILVa

Saccharomyces cerevisiae threonine deaminase ILVa

- SlTD

Solanum lycopersicum threonine deaminase

- ScGDH1′

Saccharomyces cerevisiae glutamate dehydrogenase 1 (K74V/T177S)

- ScGDH3′

Saccharomyces cerevisiae glutamate dehydrogenase 3 (K75V/T178S)

- EcGDH’

Escherichia coli glutamate dehydrogenase (K92V/T195S)

- BcLeuDH

Bacillus cereus leucine dehydrogenase

- BfLeuDH

Bacillus flexus leucine dehydrogenase

- SfValDH

Streptomyces fradiae valine dehydrogenase

- NiCAR

Nocardia iowensis carboxylic acid reductase

- NfCAR

Nocardia farcinica carboxylic acid reductase

- MsCAR

Mycobacterium smegmatis carboxylic acid reductase

- MmCAR

Mycobacterium marinum carboxylic acid reductase

- HOM3-R2

Saccharomyces cerevisiae aspartate kinase (G425D)

- EcALR

Escherichia coli aldehyde reductase

- ScGLY1

Saccharomyces cerevisiae threonine aldolase

- BsSFP

Bacillus subtilis phosphopantetheinyl transferase

- ORF

open reading frame

Additional file

Additional file 1. Additional figures and table.

Contributor Information

Nora Weber, Phone: +41 61 485 20 93, Email: noraw@evolva.com.

Anaëlle Hatsch, Email: anaelleh@evolva.com.

Ludivine Labagnere, Email: ludivinel@evolva.com.

Harald Heider, Email: haraldh@evolva.com.

References

- 1.El-Sayed ASA, Yassin MA, Ibrahim H. Coimmobilization of l-methioninase and glutamate dehydrogenase: novel approach for l-homoalanine synthesis. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2015;62:514–522. doi: 10.1002/bab.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liao J, Zhang K, Cho K. Composition and methods for the production of l-homoalanine. Oakland, US; US patent 2016/0053236 A1.

- 3.Leuchtenberger W, Huthmacher K, Drauz K. Biotechnological production of amino acids and derivatives: current status and prospects. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;69:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0155-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lloyd M, Bycroft M, Gade S. Preparation of (S)-2-aminobutyric acid. WO patent 2010/019469 A2.

- 5.Yamaguchi S, Komeda H, Asano Y. New enzymatic method of chiral amino acid synthesis by dynamic kinetic resolution of amino acid amides: use of stereoselective amino acid amidases in the presence of α-amino-ε-caprolactam racemase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:5370–5373. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00807-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park E, Kim M, Shin J-S. One-pot conversion of l-threonine into l-homoalanine: biocatalytic production of an unnatural amino acid from a natural one. Adv Synth Catal. 2010;352:3391–3398. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201000601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malik MS, Park E-S, Shin J-S. ω-Transaminase-catalyzed kinetic resolution of chiral amines using l-threonine as an amino acceptor precursor. Green Chem. 2012;14:2137–2140. doi: 10.1039/c2gc35615e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tao R, Jiang Y, Zhu F, Yang S. A one-pot system for production of L-2-aminobutyric acid from l-threonine by l-threonine deaminase and a NADH-regeneration system based on l-leucine dehydrogenase and formate dehydrogenase. Biotechnol Lett. 2014;36:835–841. doi: 10.1007/s10529-013-1424-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han SW, Shin JS. Preparation of d-threonine by biocatalytic kinetic resolution. J Mol Catal B Enzym. 2015;122:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2015.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seo Y-M, Mathew S, Bea H-S, Khang Y-H, Lee S-H, Kim B-G, et al. Deracemization of unnatural amino acid: homoalanine using d-amino acid oxidase and ω-transaminase. Org Biomol Chem. 2012;10:2482–2485. doi: 10.1039/c2ob07161d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu L, Tao R, Wang Y, Jiang Y, Lin X, Yang Y, et al. Removal of l-alanine from the production of l-2-aminobutyric acid by introduction of alanine racemase and d-amino acid oxidase. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;90:903–910. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobrikov GM, Valcheva V, Stoilova-Disheva M, Momekov G, Tzvetkova P, Chimov A, et al. Synthesis and in vitro antimycobacterial activity of compounds derived from (R)- and (S)-2-amino-1-butanol—the crucial role of the configuration. Eur J Med Chem. 2012;48:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Häusler H, Kawakami RP, Mlaker E, Severn WB, Stütz AE. Ethambutol analogues as potential antimycobacterial agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2001;11:1679–1681. doi: 10.1016/S0960-894X(01)00258-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Citron K, Thomas G. Ocular toxicity from ethambutol. Thorax. 1986;41:737–739. doi: 10.1136/thx.41.10.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Periasamy M, Sivakumar S, Reddy M. New, convenient methods of synthesis and resolution of 1,2-amino alcohols. Synthesis. 2003;13:1965–1967. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh B. Synthesis of ethambutol. US patent; 1976, US 3944618 A.

- 17.Trost BM, Bunt RC, Lemoine RC, Calkins TL. Dynamic kinetic asymmetric transformation of diene monoepoxides: a practical asymmetric synthesis of vinylglycinol, vigabatrin, and ethambutol. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:5968–5976. doi: 10.1021/ja000547d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stauffer CS, Datta A. Efficient synthesis of (S, S)-ethambutol from l-methionine. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:9765–9767. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(02)01308-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonçalves RSB, Silva ET, De Souza MVN. An environmentally friendly, scalable and highly efficient synthesis of (S, S)-ethambutol, a first line drug against tuberculosis. Lett Org Chem. 2015;1:478–481. doi: 10.2174/1570178612666150521235908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotkar SP, Sudalai A. Enantioselective synthesis of (S, S)-ethambutol using proline-catalyzed asymmetric α-aminooxylation and α-amination. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 2006;17:1738–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2006.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar JK, Narsaiah AV. Stereoselective synthesis of tuberculostatic agent (S, S)-ethambutol. Org Commun. 2014;1:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paddon CJ, Keasling JD. Semi-synthetic artemisinin: a model for the use of synthetic biology in pharmaceutical development. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:355–367. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel RN. Synthesis of chiral pharmaceutical intermediates by biocatalysis. Coord Chem Rev. 2008;252:659–701. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.10.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pollard DJ, Woodley JM. Biocatalysis for pharmaceutical intermediates: the future is now. Trends Biotechnol. 2007;25:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szczebara FM, Chandelier C, Villeret C, Masurel A, Bourot S, Duport C, et al. Total biosynthesis of hydrocortisone from a simple carbon source in yeast. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:143–149. doi: 10.1038/nbt775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang K, Li H, Cho KM, Liao JC. Expanding metabolism for total biosynthesis of the nonnatural amino acid l-homoalanine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:6234–6239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912903107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen LT, Nguyen KT, Spfek J. The tylosin producer, Streptomyces fradiae, contains a second valine dehydrogenase. Microbiology. 1995;141:1139–1145. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-5-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansen EH, Møller BL, Kock GR, Bünner CM, Kristensen C, Jensen OR, et al. De novo biosynthesis of vanillin in fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) and baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:2765–2774. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02681-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D457–D462. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramos C, Delgado MA, Calderon IL. Inhibition by different amino acids of the aspartate kinase and the homoserine kinase of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1991;278:123–126. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80098-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramos C, Calderon IL. Overproduction of threonine by Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants resistant to hydroxynorvaline. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1677–1682. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.5.1677-1682.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin-Rendon E, Farfan M, Ramos C, Calderon I. Isolation of a mutant allele that deregulates the threonine biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 1993;24:465–471. doi: 10.1007/BF00351707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Otero JM, Cimini D, Patil KR, Poulsen SG, Olsson L, Nielsen J. Industrial systems biology of Saccharomyces cerevisiae enables novel succinic acid cell factory. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e54144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McNeil JB, McIntosh EM, Taylor BV, Zhang FR, Tang S, Bognar A. Cloning and molecular characterization of three genes, including two genes encoding serine hydroxymethyltransferases, whose inactivation is required to render yeast auxotrophic for glycine. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:9155–9165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monschau N, Stahmann KP, Sahm H, McNeil JB, Bognar AL. Identification of Saccharomyces cerevisiae GLY1 as a threonine aldolase: a key enzyme in glycine biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;150:55–60. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(97)00096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szamosi I, Shaner DL, Singh BK. Identification and characterization of a biodegradative form of threonine dehydratase in senescing tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) leaf. Plant Physiol. 1993;101:999–1004. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.3.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shizuta Y, Hayaishi O. Regulation of biodegradative threonine deaminase. Curr Top Cell Regul. 1976;11:99–146. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-152811-9.50010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shulman A, Zalyapin E, Vyazmensky M, Yifrach O, Barak Z, Chipman DM. Allosteric regulation of Bacillus subtilis threonine deaminase, a biosynthetic threonine deaminase with a single regulatory domain. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11783–11792. doi: 10.1021/bi800901n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reed MC, Lieb A, Nijhout HF. The biological significance of substrate inhibition: a mechanism with diverse functions. BioEssays. 2010;32:422–429. doi: 10.1002/bies.200900167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iraqui I, Vissers S, Bernard F, De Craene JO, Boles E, Urrestarazu A, et al. Amino acid signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a permease-like sensor of external amino acids and F-box protein Grr1p are required for transcriptional induction of the AGP1 gene, which encodes a broad-specificity amino acid permease. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:989–1001. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.2.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Regenberg B, Düring-Olsen L, Kielland-Brandt MC, Holmberg S. Substrate specificity and gene expression of the amino-acid permeases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 1999;36:317–328. doi: 10.1007/s002940050506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Velasco I, Tenreiro S, Calderon IL, Andre B. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Aqr1 is an internal-membrane transporter involved in excretion of amino acids. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:1492–1503. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.6.1492-1503.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mülleder M, Calvani E, Alam MT, Wang RK, Eckerstorfer F, Zelezniak A, Ralser M. Functional metabolomics describes the yeast biosynthetic regulome. Cell. 2016;167:553–565. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alarcon CM, Heitman J. FKBP12 physically and functionally interacts with aspartokinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5968–5975. doi: 10.1128/MCB.17.10.5968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valli M, Sauer M, Branduardi P, Borth ND. Intracellular pH distribution in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell populations, analyzed by flow cytometry. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:1515–1521. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1515-1521.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akhtar MK, Turner NJ, Jones PR. Carboxylic acid reductase is a versatile enzyme for the conversion of fatty acids into fuels and chemical commodities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:87–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216516110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou YJ, Buijs NA, Zhu Z, Qin J, Siewers V, Nielsen J. Production of fatty acid-derived oleochemicals and biofuels by synthetic yeast cell factories. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11709. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moura M, Pertusi D, Lenzini S, Bhan N, Broadbelt LJ, Tyo KEJJ. Characterizing and predicting carboxylic acid reductase activity for diversifying bioaldehyde production. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2016;113:944–952. doi: 10.1002/bit.25860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kara S, Schrittwieser JH, Hollmann F, Ansorge-Schumacher MB. Recent trends and novel concepts in cofactor-dependent biotransformations. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:1517–1529. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5441-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weber N, Gorwa-Grauslund M, Carlquist M. Improvement of whole-cell transamination with Saccharomyces cerevisiae using metabolic engineering and cell pre-adaptation. Microb Cell Fact. 2017;16:3. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0615-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weber N, Gorwa-Grauslund M, Carlquist M. Exploiting cell metabolism for biocatalytic whole-cell transamination by recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:4615–4624. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5576-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verho R, Londesborough J, Penttilä M, Richard P. Engineering redox cofactor regeneration for improved pentose fermentation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:5892–5897. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.10.5892-5897.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perez-Zabaleta M, Sjöberg G, Guevara-Martínez M, Jarmander J, Gustavsson M, Quillaguamán J, et al. Increasing the production of (R)-3-hydroxybutyrate in recombinant Escherichia coli by improved cofactor supply. Microb Cell Fact. 2016;15:91. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0490-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dos Santos MM, Raghevendran V, Kötter P, Olsson L, Nielsen J. Manipulation of malic enzyme in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for increasing NADPH production capacity aerobically in different cellular compartments. Metab Eng. 2004;6:352–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nevoigt E. Progress in metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72:379–412. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00025-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao X, Shi F, Zhan W. Overexpression of ZWF1 and POS5 improves carotenoid biosynthesis in recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2015;61:354–360. doi: 10.1111/lam.12463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Joska T, Mashruwala A, Boyd J, Belden W. A universal cloning method based on yeast homologous recombination that is simple, efficient, and versatile. J Microbiol Methods. 2014;100:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Leeuwen J, Andrews B, Boone C, Tan G. Rapid and efficient plasmid construction by homologous recombination in yeast. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2015 (9). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Eichenberger M, Lehka B, Folly C, Fischer D, Martens E, Naesby M. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for de novo production of dihydrochalcones with known antioxidant, antidiabetic, and sweet tasting properties. Metab Eng. 2017;39:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gietz RD, Schiestl RH. High-efficiency yeast transformation using the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Nat Protoc. 2008;2:31–35. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Samach A, Hareven D, Gutfinger T, Lifschitz E. Biosynthetic threonine deaminase gene of tomato: isolation, structure, and upregulation in floral organs. Dev Biol. 1991;88:2678–2682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.