Abstract

Introduction:

One of the important tasks in managing labor is the protection of perineum. An important variable affecting this outcome is maternal pushing during the second stage of labor. This study was done to investigate the effect of breathing technique on perineal damage extention in laboring Iranian women.

Materials and Methods:

This randomized clinical trial was performed on 166 nulliparous pregnant women who had reached full-term pregnancy, had low risk pregnancy, and were candidates for vaginal delivery in two following groups: using breathing techniques (case group) and valsalva maneuver (control group). In the control group, pushing was done with holding the breath. In the case group, the women were asked to take 2 deep abdominal breaths at the onset of pain, then take another deep breath, and push 4–5 seconds with the open mouth while controlling exhalation. From the crowning stage onward, the women were directed to control their pushing, and do the blowing technique.

Results:

According to the results, intact perineum was more observed in the case group (P = 0.002). Posterior tears (Grade 1, 2, and 3) was considerably higher in the control group (P = 0.003). Anterior tears (labias) and episiotomy were not significantly different in the two groups.

Conclusions:

It was concluded that breathing technique of blowing can be a good alternative to Valsalva maneuver in order to reduce perineal damage in laboring women.

Keywords: Breathing technique of blowing, delivery, laboring women, perineal lacerations, pelvic floor muscle

Introduction

Pelvic floor muscle dysfunction may cause severe problems in women such as fecal and urinary incontinence and anorgasm, which decreases the quality of life.[1] One of the factors affecting perineal injuries during childbirth is the way the mother pushes in the second stage of labor.[2] There are two methods for handling the second stage of labor. In the first method which was first introduced in 1950 as the Valsalva maneuver, women are trained simultaneously with the onset of contractions to take a deep breath, hold it, and start pushing forcefully as they can. Frequent and prolonged pushing with Valsava maneuver causes nerve and structural damage on the pelvic floor,[3] which has been attributed to the increase of abdominal pressure[4] and rapid expansion of vagina and perineum.[5] The second method is the open-glottis spontaneous pushing. In this method, upon full dilatation and feeling the urge to push, the woman starts pushing with open glottis while breathing out.[6] The adverse consequences of this method for the mother are much less than the previous method. Experts suggest that one of the effective methods in reducing tissue damage is to stretch muscles slowly and steadily.[7] Accordingly, it can be said that one of the possible ways to reduce damage to the perineum is to lower the abdominal pressure added to uterine contractions at the moment of delivery and help the baby's head out slowly and simultaneously with contractions.[8] Because at the moment the head is coming out, the mother is pushing severely trying everything to make the baby come out, and on the other hand, the perineal tissues resist this pressure because of connective tissues, therefore, the risk of trauma to the perineum can increase. Thus, a technique should be used to reduce the pressure on the perineum. Breathing technique of blowing is one of the methods that can create such conditions for the perineal and pelvic floor.[9] Several studies have shown that breathing technique of blowing in women, who are at the end of the first stage of an early urge to push, is an effective method to reduce pressure exerted on the perineum as well as for reducing the urge to push in the mother. With regard to the abovementioned issues, slow expansion of the perineum tissues can reduce its damage during childbirth. In contrast, there is no time for gradual stretching and thinning of the perineum in pushing with close glottis while holding the breath.[5,6,7,8,9,10] In Iran Valsava maneuver is accepted as a standard and routine obstetric method in laboring women.[11] However, as one of the main tasks in managing vaginal birth is to protect the perineum and improve the child labor outcomes,[10,12] we decided to conduct this study to examine the effects of the two different methods of pushing on the health of the perineum as well as to investigate the effect of breathing techniques on perineal damage extention in laboring Iranian women.

Materials and Methods

This randomized clinical trial was conducted among 166 primiparous women admitted to Kamali hospital, Karaj, Iran for termination of pregnancy from October 2013 to January 2014 in two groups (n = 83/each). The inclusion criteria were as follows: Iranian woman, 18 ≤ age ≤ 35 years, primiparous, singleton pregnancy with cephalic presentations at term, candidate for vaginal delivery, low-risk pregnancy, having 3–5 cm dilatation, normal body mass index (BMI) (19.8–20), not attending regular counseling to prepare for childbirth, not having regular exercise and massage of perineum during pregnancy, and having perineal length larger than 3 cm. In addition, the exclusion criteria included unwillingness to continue the research, failure to cooperate with the researcher, premature rupture of membranes, emergency cesarean delivery, occiput posterior position, having vulvovaginitis at the time of hospitalization, smoking in pregnancy, underlying chronic disease such as chronic constipation, asthma, chronic cough, or urinary incontinence, shoulder dystocia, birth weight of <2500 g and >3999 g, head circumference of <32 cm and >38 cm, use of pharmacological pain reduction methods, and carrying out heavy exercises such as body building and horse riding.

After obtaining written informed consent, the researcher examined the selected participants to check the status of their pelvis and muscles on the basis of the Brink scale. This scale was first introduced in 1994 by Brink et al.[12] In this method, the woman is placed in a dorsal lithotomy position and the examiner enters his/her two fingers (forefinger and middle finger) 6–8 cm deep into the vagina, in a way the nails are upward. The woman is asked to contract the muscles around the fingers—like when she wants to stop urine flow—as hard as she can. The tonicity of the pelvic muscles is examined and scored using three factors including strength of contraction, length of contraction, and the examiner's finger displacement in vertical plane on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 to 4.[12] Then, a total score of between 3 and 12 is given to every individual. A score of 6 or more is indicative of good muscle tone.

The validity of Brink scale was approved by Brink in 1994, using concurrent validity by comparing its results with vaginal electromyography.[12] Its reliability was also confirmed using test–retest reliability and concurrent observation. To ensure the reliability of this method, the researcher once again conducted the reliability test using simultaneous observation, and it was reconfirmed based on Spearman correlation 0.98 (P < 0.001).

After examination, the participants were randomly assigned to two groups according to the table of random numbers: (1) Using breathing techniques (case group) and (2) valsalva maneuver (control group). Following this, the breathing techniques were taught to the participants. Deep abdominal breathing technique used by the case group in the second stage was explained and practiced by both the groups. In addition to this technique, pushing technique with open glottis in the second stage of labor as well as blowing technique—at the time the baby's head is emerging—were once again taught to the intervention group. When the second stage of labor with full dilatation was started in both the groups, the women were asked to start pushing, as trained after full dilatation and feeling the baby's head in position 1+. In the control group, pushing was carried out according to delivery room routine by holding the breath, and in the case group, the women were asked to take two deep abdominal breaths during the onset of pain, then take another deep breath, and push for 4–5 seconds with the open mouth, while controlling exhalation and then resume the process for the next push as trained. Deliveries were conducted by two research assistants who were equal in terms of education and experience. Further, their delivery techniques were controlled and matched by the researcher. Delivery in both the groups in the lithotomy and episiotomy position was performed according to the indications. In the intervention group, the pushing continued until the baby was delivered. And from the crowning stage onward, the women were directed to control their pushing and perform the blowing technique as previously trained, such that the head emerges only due to uterine contractions and not due to increase in abdominal pressure caused by excessive pushing. As soon as the baby was completely delivered, the second research assistant who was blinded to the sample grouping checked the perineum status and recorded the findings. In order to examine the reliability of observations and correlation between the results (obtained from the two research assistants) concerning the type of perineal trauma (intact, episiotomy, tear, and rupture of the anterior and posterior), Kappa statistics were used, and a Kappa coefficient of 0.93 and P < 0.001 was obtained, which represents a good agreement between the views of the two research assistants concerning the diagnosis of perineal damage.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) statistical software. In order to compare the qualitative variables in this study, χ2 test and Fisher's exact test were used. Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney test was used to compare the quantitative variables. P value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Ethical considerations

This research was approved by the ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Results

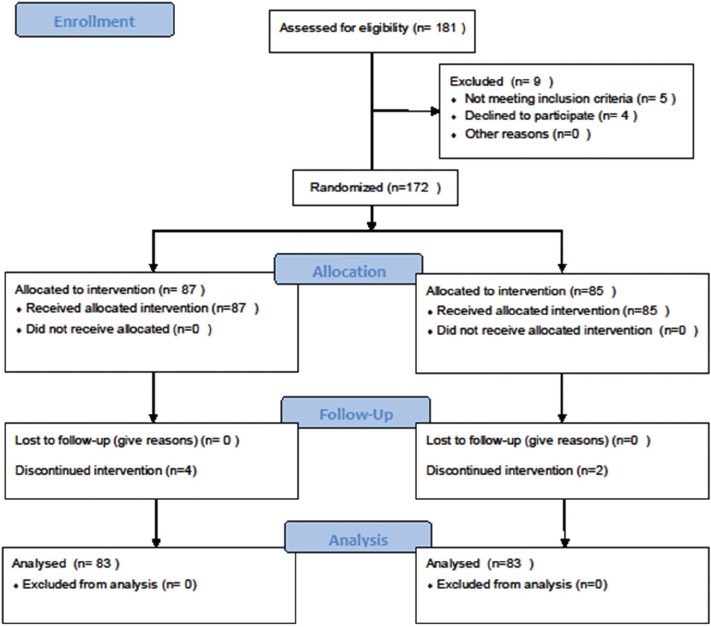

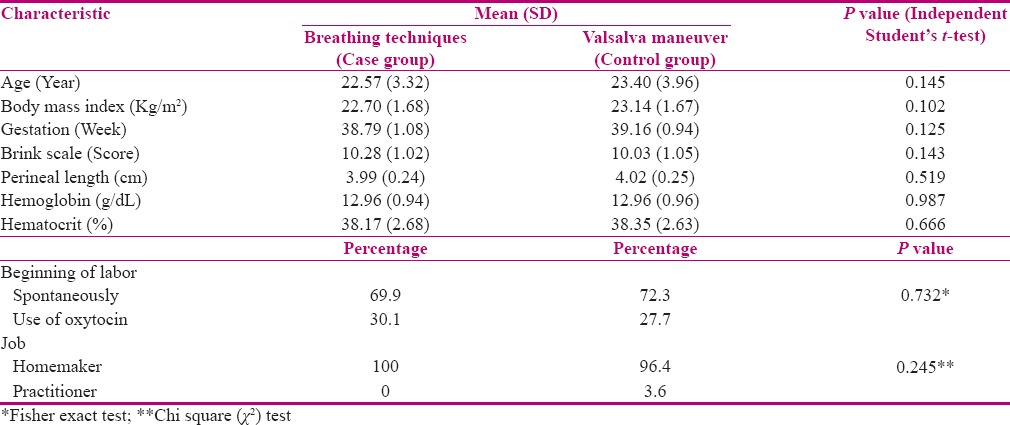

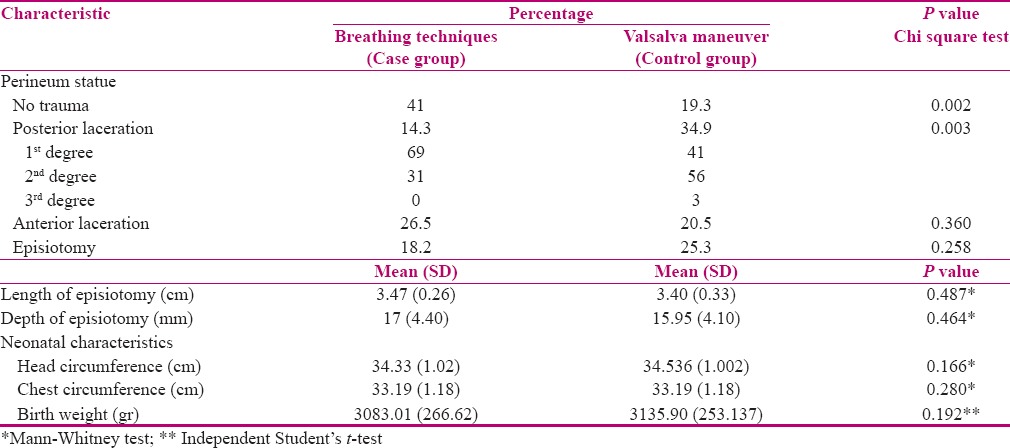

In this study, out of 181 individuals, who received an initial examination, were included into the study; finally, 166 primiparous women who met our inclusion criteria completed the study [Figure 1]. Participants were matched on demographic and obstetric characteristics in two groups [Table 1]. With regard to perineum status, the results indicated that the frequency of intact perineum in the case and control group was 41% and 19.3%, respectively. The difference was statistically significant and higher in the case group (P = 0.002). In the control group, the frequency of different posterior laceration (Grade 1, 2, 3) was significantly higher compared with case group (P = 0.003). With regards to different types of anterior lacerations between the two groups, rupture only occurred in the labia. The frequency of this type of rupture was 26.5% and 20.5% in the case and control groups, respectively. Although It was higher in the case group, the difference was not significant (P = 0.360). The frequency of episiotomy was 18.2% in the case group and 25.3% in the control group. Moreover, the difference between the two groups was not significant in this regard [Table 2]. There was no significant difference between the two groups concerning the baby's weight, chest size, and head circumference [Table 2].

Figure 1.

CONSORT 2010 flow diagram

Table 1.

Demographic and obstetric characteristics of women in two groups (breathing techniques and Valsalva maneuver)

Table 2.

Comparison of perineum status and neonatal characteristics after delivery in two groups (Breathing techniques and Valsalva maneuver)

Discussion

The present study showed that the overall frequency of intact perineum in the case group was more than the control group. The frequency of different types of posterior rupture (Grade 1, 2, 3) in the control group was significantly higher than the blowing technique group. These results are consistent with the Sampselle et al.[4] results, whereas they are in contradiction with the studies by Asali et al. and Yildirim et al.[10,13]

In the study by Sampselle et al.,[4] the participants were divided into two groups, i.e. one with spontaneous pushing with open glottis and the other with Valsalva maneuver pushing. The results indicated that women with spontaneous pushing enjoyed more intact perineum, less tearing (Grade 1, 2, 3), and less episiotomy (P = 0.043). However, in the study by Asali et al.,[10] there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of perineal laceration.

In the present study, there was no significant difference between the two groups in the frequency of anterior rupture and episiotomy. It can be attributed to the fact that the participants had been matched in both groups with regard to the factors affecting incidence of episiotomy or its indications. There was no significant difference between the two groups considering the length and depth of episiotomy, which were measured by a ruler and a sterile swab. These findings is inconsistent with the results of Asali et al.[10] who reported that the incidence of episiotomy in the group who had spontaneous strain was lesser than those who performed the Valsalva maneuver in the second phase of delivery. Further, in the study by Yildirim et al., there was no difference between the two groups in terms of episiotomy rates and perineal laceration.[13]

The difference between the results of the present study with these studies could be due to the use of the blowing technique. In the studies by Asali et al. and Yildirim et al., regardless of the pushing type, both groups continued pushing until the last minute when the baby's head emerged.[10,13] However, in the present study, women started blowing strongly only at the very moment the head started emerging, and made the baby's head come out smoothly by uterine contractions. This can have a significant impact on reducing tear. Frequent and prolonged pushing in Valsalva maneuver causes nerve and structure damage to pelvic floor muscles. Moreover, the damage is due to increased abdominal pressure and rapid dilatation of the vagina. In the breathing technique, the increased pressure resulting from uterine contractions as well as the abdominal pressure during pushing is removed by exhalation and blowing. The muscles are slowly expanded/dilated only due to the pushing induced by the baby's head. This pressure by the baby's head is the result of contractions. This might be the reason for reducing perineal trauma during this procedure (blowing technique). Furthermore, Simpson et al. in their pilot study suggested that involuntary bearing-down efforts are accompanied by adequate labor progress and result in less perineal trauma.[14]

Conclusion

According to our results, it is purposed that breathing technique of blowing can be a good alternative to Valsalva maneuver in order to reduce perineal damage in laboring women. Although more randomized controlled trials are necessary for conclusive evidence in this matter, our results add to the evidence that breathing technique of blowing is a strategy that protects the maternal perineal tissue.

Financial support and sponsorship

Research Council of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors greatly appreciate the Research Council of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran for their financial support. Also, we would like to thank the Kamali Hospital staff, Karaj, Iran for their cooperation in conducting this research. The authors declare that there were no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Barbosa AMP, Marini G, Piculo F, Rudge CV, Calderon IMP, Rudge MV. Prevalence of urinary incontinence and pelvic floor muscle dysfunction in primiparae two years after cesarean section: Cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med J. 2013;131:95–9. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802013000100019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosomworth A, Bettany-Saltikov JA. Just take a deep breath. A review to compare the effects of spontaneous versus directed Valsalva pushing in the second stage of labour on maternal and fetal wellbeing. Midwifery Digest. 2006;16:157–66. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemos A, Amorim MM, Dornelas de Andrade A, de Souza AI, Cabral Filho JE, Correia JB. Pushing/bearing down methods for the second stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015:CD009124. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009124.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sampselle CM, Hines S. Spontaneous pushing during birth: Relationship to perineal outcomes. J Nurse Midwifery. 1999;44:36–9. doi: 10.1016/s0091-2182(98)00070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuuli MG, Frey HA, Odibo AO, Macones GA, Cahill AG. Immediate compared with delayed pushing in the second stage of labor: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:660–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182639fae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prins M, Boxem J, Lucas C, Hutton E. Effect of spontaneous pushing versus Valsalva pushing in the second stage of labour on mother and fetus: A systematic review of randomised trials. BJOG. 2011;118:662–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.02910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simkin P, Ancheta R. The labor progress handbook: Rarly interventions to prevent and treat dystocia: John Wiley and Sons. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talasz H, Kofler M, Kalchschmid E, Pretterklieber M, Lechleitner M. Breathing with the pelvic floor? Correlation of pelvic floor muscle function and expiratory flows in healthy young nulliparous women. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:475–81. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-1060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albers LL, Sedler KD, Bedrick EJ, Teaf D, Peralta P. Factors related to genital tract trauma in normal spontaneous vaginal births. Birth. 2006;33:94–100. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2006.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asali R TM, Abedian Z, Esmaeili H. Spontaneous and active pushing in second stage labor and fetal outcome in primiparous women. JBUMS. 2006;8:51–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salehian T, Safdari-Dehchshmeh F, Rahimi-Madiseh M, Beigi M, Delaram M. Comparing the effects of spontaneous pushing versus Valsalva pushing technique on outcome of delivery in primiparous women. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2012;14:31–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brink CA, Wells TJ, Sampselle CM, TAILLIE ER, Mayer R. A digital test for pelvic muscle strength in women with urinary incontinence. Nurs Res. 1994;43:352–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yildirim G, Beji NK. Effects of pushing techniques in birth on mother and fetus: A randomized study. Birth. 2008;35:25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2007.00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simpson KR, James DC. Effects of immediate versus delayed pushing during second-stage labor on fetal well-being: A randomized clinical trial. Nurs Res. 2005;54:149–57. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200505000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]