Abstract

The underrepresentation of Blacks, Hispanics or Latinos, and American Indians or Alaska Natives among dentists raises concerns about the diversity of the dental workforce, disparities in access to dental care and in oral health status, and social justice. We quantified the shortage of underrepresented minority dentists and examined these dentists’ practice patterns in relation to the characteristics of the communities they serve. The underrepresented minority dentist workforce is disproportionately smaller than, and unevenly distributed in relation to, minority populations in the United States. Members of minority groups represent larger shares of these dentists’ patient panels than of the populations in the communities where the dentists are located. Compared to counties with no underrepresented minority dentists, counties with one or more such dentists are more racially diverse and affluent but also have greater economic and social inequality. Current policy approaches to improve the diversity of the dental workforce are a critical first step, but more must be done to improve equity in dental health.

Keywords: Oral Health Workforce, Dentists’ Practice Patterns, Underrepresented Minorities, Diversity

US populations of Blacks, Hispanics or Latinos, and American Indians or Alaska Natives experience large disparities in both access to dental care and oral health status.[1] In addition, Black, Hispanic or Latino, and American Indian or Alaska Native dentists are underrepresented within the overall dental workforce.[2–4] Evidence suggests that improving workforce diversity promotes social justice and also increases access, health equity and health care quality, particularly for minority populations.[5]

Achieving workforce diversity in the health professions is a persistent policy problem. Multiple and multilevel programmatic approaches to improving workforce diversity and access to care for underserved populations have been implemented over the years, with limited success. For instance, mentoring and workforce development efforts aim to increase the pool of qualified minority applicants to health profession schools by supporting K–12 and college education for disadvantaged children.[6] Bridge, pipeline, and post-baccalaureate programs seek to increase the diversity of dental school applicants and to give students practice experience in underserved areas.[7] In addition, reforms have been implemented that seek to reduce unconscious bias in dental schools’ admission processes.[8]

Federal and state programs also work to increase diversity in the workforce and improve minority patients’ access to dental care. For instance, eligibility for scholarships and loan repayment programs for dentists often requires a commitment to practice in a dental Health Professional Shortage Area for a defined period.[9] Title VII of the Public Health Service Act of 1944 provides grants to health professions education programs that are intended to increase the diversity of the health care workforce. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) provides scholarships for disadvantaged students and funding for accredited health education programs to improve recruitment, training, and retention of underrepresented minority students and nontraditional students from disadvantaged backgrounds.[10–12] And when workforce shortages remain in high need areas, the United States has historically relied on foreign-trained health care professionals to fill the gaps.[13]

Research on the impact of these efforts is generally focused at the programmatic level, asking whether specific goals were achieved (for instance, if a certain number of slots were filled by minority students or a certain number of outreach sessions were held).[14] Estimates of the broader impacts of these programs and policies on either increasing workforce diversity or improving health outcomes for minority communities are difficult to make and hard to find.[15] Particularly in dentistry, data on the cumulative impact of these policy efforts on workforce diversity remain scarce.

Underlying many efforts to improve diversity are assumptions about the impact of diversity on public health, and minority health in particular.[15] We use the term underrepresented minority dentists to refer to Blacks, Hispanics or Latinos, and American Indians or Alaska Natives, whose proportion of the dentist workforce is disproportionately smaller than their proportion of the US population. In comparison, Asians are overrepresented in the dentist workforce, compared to their proportion of the US population. Underrepresented minority providers are more likely than non-minority providers to work in or near minority communities and to treat minority patients.[16,17] Greater access to and use of care is thought to stem, in part, from better relationships and communication between providers and patients who share the same racial/ethnic background (that is, who have what is known as racial concordance), which in turn leads to better acceptance of health care.[15] Yet evidence that racial concordance improves health outcomes remains inconclusive, which is unsurprising given the myriad factors involved in producing health.[18]

Elsewhere we quantified the shortage of underrepresented minority dentists in the United States and found that to bring the share of these dentists into parity with their share of the US population would require an additional 19,714 black dentists, 31,214 Hispanic or Latino dentists, and 2,825 American Indian or Alaska Native dentists.[19–21] In this study we examined the practice patterns of underrepresented minority dentists in relation to the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the communities in which they practice. We used a 2012 survey of a national sample of underrepresented minority dentists in conjunction with several available sources of national data. Our goal was to assess the status of workforce diversity in the dental field.

Study Data And Methods

With approval from the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, San Francisco, a national sample survey of underrepresented minority dentists was conducted in 2012 to assess their personal characteristics, practice patterns, educational history, and opinions about key professional issues. The survey had an adjusted response rate of 34 percent (N = 1,489) and was weighted for selection likelihood and non-response bias to be nationally representative of the population of underrepresented minority dentists. Comprehensive details on the survey methodology, response rate, and response quality have been reported previously.[22]

Descriptive and multivariate statistics from the underrepresented minority dentist survey were computed, and several variables from nationally representative, publicly available data sets (described below) were linked to the primary data. These linked variables allowed us to explore the relationship between underrepresented minority dentists’ practice patterns and the population characteristics of the counties where the dentists were located. We examined the distribution of underrepresented minority dentists by census division, and compared this to national counts of all dentists. We examined practice type and the factors that influenced dentists’ initial practice choice and current job satisfaction, and we compared our results to nationally published data on all dentists.[23–25] Finally, we investigated whether practice patterns among underrepresented minority dentists are changing over time by comparing the responses of those ages forty-nine (the average age of respondents in the 2012 dentist survey) and older with the responses of those younger than forty-nine.

We linked the 2012 dentist survey data to all external sources at the county level using Federal Information Processing Standards codes which identify individual counties and county equivalents. We used five county-level variables from the American Community Survey three-year estimates (for the period 2010–12): estimated populations of American Indians or Alaska Natives, blacks, and Hispanics or Latinos (alone or in combination with one or both of the other populations), total population, and median income. For all counties with one or more practicing underrepresented minority dentists, observations were available for each variable except the total population—which was missing in thirty-two (1 percent) of the counties. Descriptive statistics on population means were calculated for counties where at least one underrepresented minority dentist was known to be located and for counties where no such a dentist was known to be located. Two-tailed tests of significance were performed (alpha: 0.05).

To compare the distribution of underrepresented minority dentists to that of all dentists, we linked to the dentist survey data three county-level variables from the 2012 Area Health Resources Files, a collection of data sources produced annually by HRSA. Those variables were the number of active dentists from the 2010 American Dental Association master file, the population from the 2010 census, and the 2012 dental Health Professional Shortage Area codes. From these data, we computed the number of dentists per 10,000 population for all counties. Descriptive statistics were calculated for counties where at least one underrepresented minority dentist was known to be located and for counties where no such a dentist was known to be located. Two-tailed tests of significance were performed (alpha: 0.05).

To examine underrepresented minority dentists’ location in relation to high-need communities, we used measures of counties’ socioeconomic status from the 2016 County Health Rankings and Roadmaps, which provides county-level measures that are comparable across the United States. We linked the dentist survey data to a measure of the percentage of the county population not proficient in English and county-level measures of income inequality (the ratio of households in the eightieth income percentile to those in the twentieth income percentile) and of residential segregation (the mean percentage of white or nonwhite households that would need to move to a different geographic area to produce an even distribution of white and non-white households across a county)—since areas with greater dissimilarity in income and greater residential segregation have been shown to provide poorer access to care.[26] Descriptive statistics were calculated to compare counties with and those without at least one known underrepresented minority dentist present. As above, we performed two-tailed tests of significance (alpha: 0.05).

Limitations

Estimating patient mix from the demographic characteristics of the surrounding community[17] or from provider survey data[16] are common workforce analysis methods, but both are prone to misestimation.[27] This study combines these methods for a more robust analysis of provider location, but still has limitations. First, we used the survey respondents’ mailing addresses as a proxy for the locations of underrepresented minority dentists. The 34 percent response rate may have resulted in some counties with an underrepresented minority dentist not being identified. Second, the study was limited to observational correlation between factors at the macro level. Finally, limitations in the nationally available data used in this study, such as information from the American Community Survey or the County Health Rankings and Roadmaps, apply to our analysis (for an additional discussion of the nationally available data linked to our survey and of our analytic approach, see the online Appendix).[28]

Study Results

Workforce Supply

Across census divisions, the average percentage of the population that was American Indian or Alaska Native, Black, or Hispanic or Latino was 8.1 times (range: 2.9–26.7) greater than the corresponding percentage of dentists who are located there and were members of the same underrepresented minority groups. Within counties where one or more underrepresented minority dentists were located, the percentage of the population that was in the same underrepresented minority group as the dentists (that is, the racially concordant share of the population) was on average 1.7 times (range: 0.8–8.0) greater than was the case within the surrounding census division as a whole. Race and ethnicity specific percentages by census division are provided in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1.

Geographic distribution of US underrepresented minority (URM) dentists and minority populations in the surrounding communities and the dentists’ practices

| Census division | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of dentists who are: | Percent of population that is: | Average percent of URM populations In counties with racially concordant dentists | Average percent of racially concordant URM dentists’ patient population | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | ||||

| East North Central | 0.1 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 3.6 |

| East South Central | 0.1 | 0.8 | —a | 6.5 |

| Middle Atlantic | —b | 0.8 | —b | —b |

| Mountain | 0.3 | 4.6 | 8.3 | 28.1 |

| New England | 0.03 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 5.0 |

| Pacific | 0.3 | 1.9 | 3.6 | 17.0 |

| South Atlantic | 0.3 | 0.9 | 7.2 | 11.0 |

| West North Central | 0.2 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 4.4 |

| West South Central | 0.7 | 2.0 | 14.4 | 32.7 |

| All | 0.2 | 1.4 | 8.0 | 20.4 |

| Black | ||||

| East North Central | 2.7 | 20.2 | 21.4 | 50.3 |

| East South Central | 7.6 | 33.5 | 31.3 | 47.0 |

| Middle Atlantic | 2.2 | 18.2 | 19.4 | 48.5 |

| Mountain | 1.2 | 5.3 | 6.8 | 24.9 |

| New England | 1.3 | 10.1 | 11.2 | 29.3 |

| Pacific | 1.0 | 7.2 | 9.3 | 27.1 |

| South Atlantic | 7.0 | 29.0 | 34.2 | 48.6 |

| West North Central | 1.2 | 14.7 | 20.2 | 44.6 |

| West South Central | 3.2 | 15.9 | 21.1 | 38.4 |

| All | 3.0 | 19.0 | 25.7 | 44.9 |

| Hispanic or Latino | ||||

| East North Central | 1.5 | 11.6 | 13.6 | 35.2 |

| East South Central | 0.9 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 16.2 |

| Middle Atlantic | 2.1 | 18.3 | 18.7 | 47.1 |

| Mountain | 2.8 | 30.1 | 32.5 | 38.3 |

| New England | 1.5 | 11.5 | 10.1 | 25.6 |

| Pacific | 3.4 | 35.0 | 33.7 | 43.0 |

| South Atlantic | 4.6 | 20.4 | 30.2 | 39.0 |

| West North Central | 1.2 | 6.4 | 5.9 | 17.3 |

| West South Central | 3.9 | 38.0 | 53.5 | 56.0 |

| All | 2.8 | 22.2 | 30.3 | 41.8 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the 2012 underrepresented minority dentist survey, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. National and State-Level Projections of Dentists and Dental Hygienists in the U.S., 2012–2025. Rockville, MD; 2015, the 2010–2012 American Community Survey

Not reportable due to small sample size.

No data.

Care Of Minority Patients

On average, the share of underrepresented minority dentists’ patients who were racially concordant with the dentist was 2.6 times (range: 1.0–7.8) greater than the same underrepresented minority group’s share of the population in the county where the dentists were located. For example, American Indian or Alaska Native dentists represented just 0.2 percent of all dentists across census divisions, though American Indians and Alaska Natives make up 1.4 percent of the population (Exhibit 1). These dentists are located in counties where American Indians and Alaska Natives average 8 percent of the population, and American Indians and Alaska Natives make up 20.4 percent of their patient panels on average. This share of patient panels is 2.6 times greater than the share of American Indians and Alaska Natives in the counties where these dentists are located, and 14.6 times greater than the share across all census divisions. Additional details on Exhibit 1 including range data for county population and patient panel estimate are available in the online supplement (Note 28).

On average, the percentage of Black patients on Black dentists’ patient panels was 1.7 times greater than the Black population’s share in counties where Black dentists were located, and 2.4 times greater than the percentage of the Black population across all census divisions. The percentage of Hispanic or Latino patients on Hispanic or Latino dentists’ panels was 1.4 times greater than the Hispanic or Latino population’s share in the counties where Hispanic or Latino dentists were located, and 1.9 times greater than the Hispanic or Latino population across all census divisions.

Racially concordant patients did not always account for the largest share of underrepresented minority dentists’ patient panels. However, these dentists did treat more patients of their own race or ethnic group, compared to dentists belonging to different underrepresented minority groups (Exhibit 2). Additionally, racially concordant patients from the three underrepresented minority groups accounted for 54.1 percent of underrepresented minority dentists’ patient population on average. These data show that the lack of alignment between the number of underrepresented minority dentists and the size of the minority communities that seek care from them is consistently large, although it varies greatly across geographic regions and population groups.

Exhibit 2.

Average percent of patient populations treated by underrepresented minority (URM) dentists, by race/ethnicity

| Clinically Active Dentists (N = 11,408) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient population | Black | American Indian or Alaska Native | Hispanic or Latino | All |

| Black | 44.9 | 12.8 | 13.0 | 29.2 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3.7 | 20.4 | 3.9 | 4.7 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 19.8 | 13.7 | 41.8 | 30.1 |

| All URM | 58.8 | 37.7 | 50.5 | 54.1 |

| White | 30.9 | 54.6 | 39.5 | 35.8 |

| Asian | 5.9 | 8.2 | 6.4 | 6.2 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the 2012 underrepresented minority dentist survey.

Practice Location Choice And Motivations

To further understand underrepresented minority dentists’ choice of practice location, we compared the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of counties with and counties without such dentists (Exhibit 3). In counties with one or more underrepresented minority dentists, the average underrepresented minority population (31.1 percent) was 41 percent greater than in the counties without such a dentist (18.5 percent), a significant difference. Similarly, we found significantly higher percentages of racially concordant populations and populations of the three minority groups in counties where underrepresented minority dentists were located, compared to counties without such a dentist. (Data shown in online appendix) (note 28)

Exhibit 3.

Characteristics of counties with and without underrepresented minority (URM) dentists

| Counties | No URM dentist | One or more URM dentists | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristicsa | N | Mean | County average | |

| Population | ||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1,846 | 2.0% | 1.8% | 2.7%**** |

| Black | 1,846 | 10.9% | 9.5% | 14.8%**** |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1,846 | 8.8% | 7.1% | 13.6%**** |

| URM | 1,846 | 21.8% | 18.5% | 31.1%**** |

| Total | 1,846 | 162,035 | 71,613 | 411,572**** |

| Median household income | 3,143 | $45,644 | $44,226 | $52,750**** |

| Dentist populationb | N | Mean | County average | |

| Dentists, 2010 | 3,148 | 58.2 | 18 | 261**** |

| Dentists per 10,000 population, 2010 | 2,884 | 3.9 | 3.5 | 5.5**** |

| Other County Indicatorsc | N | Mean | County population average | |

| Income inequality indexd | 3,140 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.7**** |

| Residential segregatione | 2,780 | 31.3 | 30.3 | 35.6**** |

| Not proficient in English | 3,140 | 1.8% | 1.5% | 3.3%**** |

| DHPSA statusf | N | Percent | Percent of counties | |

| No DHPSA | 808 | 25.7 | 27.5 | 17.2 |

| Partial county DHPSA | 1,724 | 54.9 | 52.6 | 66.5 |

| Full county DHPSA | 606 | 19.3 | 19.9 | 16.3 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the 2012 underrepresented minority dentist survey and the sources listed in the table footnotes.

Information from the 2010–12 American Community Survey.

Information from the 2012 Area Health Resources Files.

Information from the 2016 County Health Rankings and Roadmaps.

Ratio of households in the eightieth income percentile to those in the twentieth income percentile.

Mean percentage of white or nonwhite households that would need to move to different geographic areas to produce an even distribution across a county.

Information from the 2012 dental Health Professional Shortage Area (DHPSA) database.

p < 0.001

We also observed significantly higher rates of income inequality and residential segregation and higher percentages of the population not proficient in English in counties where underrepresented minority dentists were located. However, these counties also had significantly larger average population sizes, higher median incomes, higher numbers of dentists, and more favorable dentist-to-population ratios, compared to counties without any underrepresented minority dentists. Underrepresented minority dentists were more frequently located in counties with a partial dental Health Professional Shortage Area, compared to counties that have no designation or a full county designation, but we could not determine whether these dentists were serving the populations in the shortage areas.

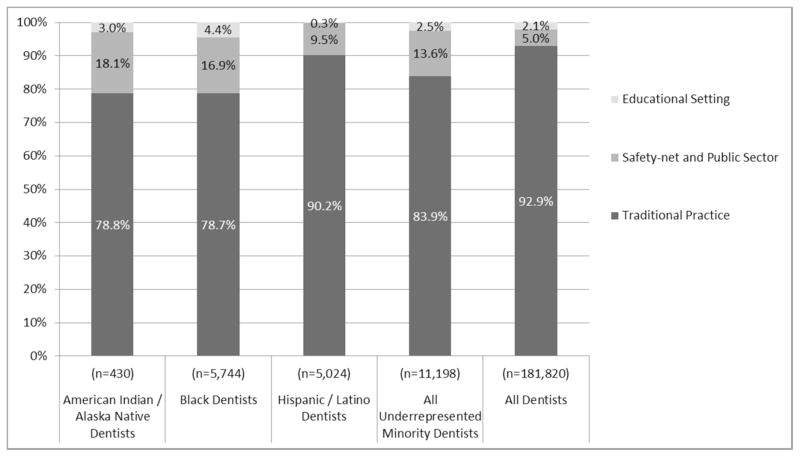

Finally, we compared practice type from the survey data to nationally published data on practice type, another indicator of service to underserved populations. We found that compared to all dentists, underrepresented minority dentists were less likely to be in traditional practice (84 percent versus 93 percent) and were nearly three times more likely to work in safety-net or public-sector settings (13.6 percent versus 5.0 percent) (Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4.

Current primary practice settings of active underrepresented minority dentists (weighted) by race/ethnicity and all dentists.

Source: 2012 Underrepresented Minority Dentist Survey and American Dental Association, Distribution of Dentists in the United States by Region and State, 2009: Table 12: Primary Occupation of All Dentists by Region and State, 2009. 2011, ADA Survey Center: Chicago, IL.

Notes: Traditional: solo, associate, contractor, group practice, and corporate (survey), or private practice (ADA).

Safety-net and Public Sector: local or federal government, public health corps, IHS, civil hire on Indian land, health center, hospital, armed forces, and prison (survey), or armed forces, other federal services, state or local government, hospital staff, and other health/dental organization staff (ADA).

Education: educational institution (survey) or dental school faculty/staff (ADA).

The most significant drivers of underrepresented minority dentists’ initial choice of practice on a five-point scale (with 1 being very important and 5 being unimportant) were income potential (1.4), geographic location (2.0), and family considerations (2.1). Across the underrepresented minority groups there was minor variation in these drivers. For example, American Indian or Alaska Native and Hispanic or Latino dentists rated family considerations the most important, while Black dentists rated income potential the most important. One-third of underrepresented minority dentists rated “working with underserved populations” and the “desire to work in my own cultural communities” as an important influence on their initial choice. Additionally, 53.7 percent reported “service to my own racial/ethnic group” and 58.2 percent reported “opportunity to serve vulnerable and low-income populations” as a factor that influenced their current job satisfaction (Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5.

Factors influencing practice choice and job satisfaction among underrepresented minority dentists.

Source: 2012 underrepresented minority dentist survey.

Compared to underrepresented minority dentists who were younger than forty-nine, those who were forty-nine or older more frequently said that a desire to work in their own cultural community was an important influence on their choice of first practice location (41.9 percent versus 32.0 percent) and an important component of their job satisfaction (55.8 percent versus 52.7 percent) (data not shown). We observed no difference between the age groups in the desire to serve underserved populations at the time of initial choice of practice or in any characteristics of the county where they were located in 2012.

Discussion

Workforce Supply

The underrepresentation of American Indian or Alaska Native, Black, and Hispanic or Latino dentists is large and growing. Applications to dental school by underrepresented minority students have risen from 12.1 percent in 2000 to 15.3 percent in 2015, while enrollment of these students in dental school has risen from 10.5 percent to 14.5 percent—which indicates that proportionally more underrepresented minority applicants are being accepted over time.[24] Yet the enrollment numbers still fall far short of population parity, and Black dental student enrollment is declining. The 863 underrepresented minority students enrolled in dental school in 2015 represent 1.6 percent of the estimated 53,753 underrepresented minority dentists needed for parity in the current system.[19–21,24]

Efforts to reduce this gap in dental school enrollment must reach deeper and cast a wider net than is currently the case if there is to be any improvement. US dental schools’ admission practices present a critical gateway to increased diversity, but the current pipeline of qualified minority applicants is insufficient. Systematic discrimination against members of minority groups limits the pool of potential minority health professionals.[5] Consequently, those members of minority groups who qualify for graduate study in health care are in high demand across these professional fields.[29]

While it is no substitute for having a domestic workforce of qualified minority providers, the use of foreign-trained dentists can increase workforce diversity, particularly in the case of Hispanics or Latinos.[20] Approximately 17 percent of dentists who earned their license to practice in the United States in the period 2002–05 graduated from a dental school outside of the United States, which contributed to workforce diversity.[30] While qualified graduates of foreign medical schools may complete an accredited US medical residency program and become eligible for US licensure, in dentistry residency training is not mandatory and there are fewer slots than demand. State dental boards are increasingly requiring graduation from a CODA accredited dental program to qualify for licensure which is driving foreign-trained dentists to complete an international dentist program or other advanced-standing program. This means that instead of sitting for a state board exam foreign graduates are essentially repeating dental school. Tuition for these programs is significantly higher than tuition for traditional training, which may impact graduates’ ultimate choice of practice type or location..[31]

Expanding the dental care team through the use of new types of providers such as dental therapists and expanding the roles for current providers such as community health workers are other potential strategies for diversifying the workforce.[32] These occupations may be attractive to individuals from historically disadvantaged populations who might otherwise not have considered dentistry, creating a new pipeline into clinical dental practice, expanding career tracks within the dental field, and increasing the dental team’s economic, cultural, racial, and ethnic diversity.[33] Policy changes to expand the workforce through these new pathways to practice would augment the important traditional efforts to diversify the dental workforce through pipeline programs, admission policies, scholarships, and loan repayment programs.

Care For Minority Patients

Not only are underrepresented minority dentists typically located in counties where underrepresented minority populations make up a large share of the overall population, but dentists within those counties on average have a disproportionately large share of underrepresented minority patients in their patient panels, compared to the racial and ethnic makeup of the counties. Our findings confirm previously reported patterns of minority dentists’ serving minority patient populations and show for the first time the geographic variability in these patterns across regions and minority groups, thereby providing information to help inform local solutions to address these disparities.[16]

In addition to creating important access points for patients, the presence of underrepresented minority dentists in minority and underserved communities provides role models for local people that may help diversity the workforce pipeline. However, the dentists’ presence alone is not sufficient. Supportive mechanisms to expand the pipeline of minority dentists, such as investments in health professional education practice partnerships[29] that can be instituted in federally qualified health centers and teaching health centers,[34] can enhance and formalize mentoring and role modeling for disadvantaged youth who are considering entering a health profession.

Practice Location Choice And Motivations

Underrepresented minority dentists reported being motivated to serve minority communities, but translating these motivations into actual practice requires opportunities and support that may not always be present. In their senior year, minority dental students were more likely than white dental students and all dental students to report that serving their own racial or ethnic group was a very important or important reason for pursuing dentistry.[23] We found that underrepresented minority dentists do not practice in counties with high rates of poverty which indicates that other barriers exist to working in these chronically underserved areas.

For example, research has shown that minority dentists graduate with more debt than their nonminority peers.[19–21,23] Most underrepresented minority dentists work in traditional, private, fee-for-service practices where required out-of-pocket spending and lack of meaningful insurance coverage present significant barriers to people’s receiving care even where there is an adequate workforce.[35] Therefore, it is not surprising that economic and geographic factors had the most influence on underrepresented minority dentists’ initial choices of practice despite the dentists’ expressed intent to work in high-need areas. These findings extend the evidence about the relationship between intentions and actual choices of underrepresented minority dentists and raise the question of whether racial concordance is a sufficient incentive for dentists to practice in the highest-need areas, unless sustainable reimbursement opportunities, adequate public health infrastructure, and practice support are available those communities.[2]

Increasing diversity among dentists is seen as the default approach to improving access to care for minority populations, but this view relies on a faulty set of assumptions and expectations—including the belief that minority dentists, themselves already disadvantaged by systemic discrimination that results in a lack of workforce parity, will through their existence alone solve large structural inequalities in access to dental care and oral health outcomes. It is likely that the model of dental care delivery must evolve, with diversity becoming a core value, if these structural disparities are to be successfully addressed.

Policy makers and stakeholders have an opportunity to create a dental practice environment that relies on workforce diversity by design, infusing the value of diversity into improvements in dental education, financing, and delivery systems and leveraging diversity as a way to increase innovation and improve performance.[36] Workforce diversity by design is rooted in social justice and provides adequate support and incentives to increase the delivery system’s capacity to care for all patients, especially those in the greatest need.

Policy Implications

Decision makers in the dental field are acutely aware of the current pipeline, enrollment, and workforce problems, but existing policy approaches are only slowing the growth rate of disparities. Clear, evidence-based solutions have been detailed in high-level reports that identified deficiencies and recommended strategies, [2,4,5,14,15,29] which indicates that the underlying issue is not a lack of vision or options, but a lack of political will and resources to implement change.

Improving health status and access to oral health care for minority populations is a complex, multifactorial issue whose solution requires systemic change across a number of domains—not just in the workforce. The dental field is ripe for such change, as external market forces are rapidly pushing the traditional dental practice to evolve away from isolation and toward participating in larger and more integrated organizational models that are better able to adapt as states shift their Medicaid dollars to managed care.[37]

An additional catalyst of change has been the mandated pediatric dental benefit in the Affordable Care Act, which is driving the integration of medical and dental plans with new financing structures, such as capitated and value-based payment models. As payers increasingly demand accountability and implement performance-based incentives, an opportunity is emerging to create a reimbursement structure and dental care delivery model that would enable underrepresented minority and nonminority dentists to sustain practices in high-need communities. Ultimately, without oral health parity there will be limited ability to address systemic disparities in overall health. (cite my intro article in the issue, the dental divide)

Conclusion

Workforce diversity is an essential component of any strategy to improve the dental care delivery system and to address oral health care disparities. We found a daunting shortage of underrepresented minority dentists, which indicates that the cumulative impact of current policy efforts to increase workforce diversity is woefully inadequate—despite initiatives at the local, state, and federal levels. Dentists who want to serve high-need communities may be unable to do so, given the current economics of the dental practice environment, and a lack of oral health parity. A purposeful approach to improving the diversity of the dental workforce would involve investing in a longer, deeper, and sustained pipeline; robust systems of care; and a genuine culture of inclusion.

Acknowledgments

Preliminary results that quantified the disproportionate share of dental care provided by underrepresented minority dentists was presented at the Health Disparities Research Symposium at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), in October 2015. This project was supported by the Oral Health Workforce Research Center (OHWRC) at the Center for Health Workforce Studies at the University at Albany’s School of Public Health. The OHWRC is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the Department of Health and Human Services (Grant No. U81HP27843, a Cooperative Agreement for a Regional Center for Health Workforce Studies, between HRSA and the Center for Health Workforce Studies). Funding for the survey data collection was generously provided by the Dental Department at the Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center, the DentaQuest Foundation, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (Award No. P30DE020752), the UCSF Department of Preventive and Restorative Dental Sciences, Henry Schein, and HealthPlex. The authors thank the incredible advisory committee for the research and their partners in it, including the National Dental Association, Hispanic Dental Association, and Society of American Indian Dentists.

Methodological Appendix

Data Sources

American Community Survey (ACS)

The American Community Survey (ACS) is a national sample survey conducted by the Census Bureau that continuously collects data throughout each year. Each year’s data collection provides estimates on more than three million people and is designed for use at the state- or local-level. We used three-year estimates, which are based on 36 months of data collection. Three-year estimates (2010–2012) were selected to balance reliability of estimates of smaller populations against the currency of estimates since our primary data was current in 2012. All data were download from American FactFinder by county, and all counties with at least one underrepresented minority (URM) dentist were represented in the three-year estimates of the American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN), Black, and Hispanic or Latino (H/L) populations. For the total U.S. population variable, 1.0% of all counties in the U.S. (N=32) did not have a three-year estimate of the total U.S. population. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/

County Health Rankings & Roadmaps (CHR)

The County Health Rankings & Roadmaps (CHR) program is a collaboration between the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. The CHR utilizes secondary data sources to compile vital health factors used to produce county-level rankings of community well-being. Underlying data and rankings are available on the CHR web site for use by researchers and community stakeholders. A measure of income inequality and a measure of residential segregation were linked to the 2012 URM dentist survey from the 2016 CHR, which uses ACS five-year estimates (2010–2014) as its data source. Both are measures of dissimilarity, which measure the evenness with which two groups are distributed across component geographic areas comprising a larger area. In the case of the CHR, the smaller areas are census tracts, and the larger areas are counties and county-equivalents. Additionally, the percent of the population in each county who is not proficient in English was added from the 2016 CHR. All of the observations in the national sample survey were matched in the 3,141 county-level observations contained in the 2016 CHR. http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/.

Area Health Resources Files (AHRF)

The Area Health Resources Files (AHRF) are a collection of more than 50 data sources covering a wide variety of topics in health care, including health professions supply and training, health facilities’ availability and utilization, county-level population and economic data, environmental health, and health-related expenditures. The AHRF is produced annually by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). The variables linked to the 2012 URM dentist survey from 2012 AHRF were the total active professional dentists in 2010 from the American Dental Association Masterfile, the total population from the 2010 Census, and the dental Health Professional Shortage Area (DHPSA) codes for dentists in 2012. The variables retained from 2012 AHRF included 3,148 counties matching to all observations in the national sample survey. http://ahrf.hrsa.gov/.

Data Set Compilation

Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) codes consist of a two-digit unique code for each state and a three-digit unique code for each county or county-equivalent. When concatenated, the resulting five-digit code uniquely identifies each county or county-equivalent in the U.S. The 2012 URM dentist survey was conducted primarily by U.S. mail, and FIPS codes were added to the data set during the data collection period. These were updated during our survey outreach and when respondents sent in change of address information with the survey response. The ACS, CHR, and AHRF all include FIPS codes, which were linked to our primary data to uniquely identify the county in which the provider was located.

There are nine U.S. Census Divisions, each of which is comprised of a group of whole U.S. states. Because all of our surveys were mailed to providers, we already had access to the state in which the provider was located. With this information, we created a variable identifying the Census Division in which the provider was located. With county-level data already linked, we were able to treat the county-level ACS data as Census Division data for Division-level analyses using data for all counties, those with and without a URM dentist respondent.

Since more than one URM dentist respondent was often located in a given county, we created a binary variable (dummy) to identify counties with at least one URM dentist (1) and those without (0). We also created binary variables to identify counties with a URM dentist from each of the URM dentists’ racial/ethnic groups (1). In this way, a county with at least one URM dentist from each URM dentists group would be coded “1” in each of four variables: any URM dentist, AI/AN dentist, Black dentist, and H/L dentist. These binary variables allowed us to perform tests of statistical significance on the presence of a URM dentist at the county-level using ACS, CHR, and AHRF data.

Methodological Approach

Linking external data sets to our primary data allowed us to examine the proportion of the population represented by each URM group in the U.S. at the levels of the Census Division and the county for each URM dentist racial/ethnic group (Appendix Exhibit 1). We also calculated the proportion of patients by race/ethnicity within URM dentists’ practices, based on the data they reported in our survey. The racial/ethnic composition of URM dentists’ patient panels was then compared to the racial/ethnic composition of the county in which URM were located and to the racial/ethnic composition of the Census Division. We additionally examined the percent of all dentists in each Census Division who are underrepresented minority dentists by comparing our survey counts to published data in U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. National and State-Level Projections of Dentists and Dental Hygienists in the U.S., 2012–2025. Rockville, MD; 2015.

Appendix Exhibit 1.

Methodological approach

Appendix Exhibit 2.

Geographic distribution of US underrepresented minority (URM) dentists and minority populations in the surrounding communities and the dentists’ practices

| Percent of Census Division dentists who are: a | Percent of Census Division population who are b | Average percent of URM populations in counties with racially concordant dentists (range)c | Average percent of racially concordant URM dentists’ patient population (range)d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Indian or Alaska Native | ||||

| East North Central | 0.1% | 0.9% | 1.2% (0.5–2.9) | 3.6% (0–10) |

| East South Central | 0.1% | 0.8% | NA | 6.5% (5–10) |

| Middle Atlantic | ND | 0.8% | ND | ND |

| Mountain | 0.3% | 4.6% | 8.3% (0.7–73.8) | 28.1% (1–100) |

| New England | 0.03% | 0.8% | 0.6% (0.5–0.8) | 5.0% (5–5) |

| Pacific | 0.3% | 1.9% | 3.6% (1.0–19.2) | 17.0% (0–100) |

| South Atlantic | 0.3% | 0.9% | 7.2% (0.7–39.4) | 11.0% (0–40) |

| West North Central | 0.2% | 1.5% | 2.1% (1.5–2.7) | 4.4% (1–6) |

| West South Central | 0.7% | 2.0% | 14.4% (0.9–42.7) | 32.7% (0–100) |

| Total | 0.2% | 1.4% | 8.0% (0.5–73.8) | 20.4% (0–100) |

| Black | ||||

| East North Central | 2.7% | 20.2% | 21.4% (1.5–41.5) | 50.3% (1–100) |

| East South Central | 7.6% | 33.5% | 31.3% (5.0–83.3) | 47.0% (3–100) |

| Middle Atlantic | 2.2% | 18.2% | 19.4% (1.1–44.9) | 48.5% (0.5–100) |

| Mountain | 1.2% | 5.3% | 6.8% (1.0–12.0) | 24.9% (0–83) |

| New England | 1.3% | 10.1% | 11.2% (0.7–27.2) | 29.3% (1–100) |

| Pacific | 1.0% | 7.2% | 9.3% (1.2–16.6) | 27.1% (0–80) |

| South Atlantic | 7.0% | 29.0% | 34.2% (4.6–68.1) | 48.6% (1–100) |

| West North Central | 1.2% | 14.7% | 20.2% (1.3–50.2) | 44.6% (3–98) |

| West South Central | 3.2% | 15.9% | 21.1% (0.7–60.9) | 38.4% (2–94) |

| Total | 3.0% | 19.0% | 25.7% (0.7–83.3) | 44.90% (0–100) |

| Hispanic or Latino | ||||

| East North Central | 1.5% | 11.6% | 13.6% (1.1–31.0) | 35.2% (1–95) |

| East South Central | 0.9% | 5.2% | 4.8% (2.2–9.8) | 16.2% (2–60) |

| Middle Atlantic | 2.1% | 18.3% | 18.7% (1.1–53.9) | 47.1% (1–100) |

| Mountain | 2.8% | 30.1% | 32.5% (2.3–76.9) | 38.3% (0–90) |

| New England | 1.5% | 11.5% | 10.1% (0.9–20.4) | 25.6% (0–80) |

| Pacific | 3.4% | 35.0% | 33.7% (4.7–80.9) | 43.0% (1–100) |

| South Atlantic | 4.6% | 20.4% | 30.2% (0.9–64.7) | 39.0% (0.1–96) |

| West North Central | 1.2% | 6.4% | 5.9% (1.6–26.7) | 17.3% (0–80) |

| West South Central | 3.9% | 38.0% | 53.5% (2.9–95.7) | 56.0% (5–100) |

| Total | 2.8% | 22.2% | 30.3% (0.9–95.7) | 41.80% (0–100) |

Source: 2012 URM dentist survey counts by Census Division in relation to HRSA 2012 dentist estimates from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. National and State-Level Projections of Dentists and Dental Hygienists in the U.S., 2012–2025. Rockville, MD; 2015.

Source: 2012 ACS Census 3-year estimates of the percent of the population in the Census Division by race/ethnicity, alone or in combination with one or more other races.

Source: 2012 ACS Census 3-year estimates of the average percent of county population by race/ethnicity for counties where URM dentists are located within the Census Division.

Source: 2012 URM dentist survey average percent of URM dentists’ reported concordant patient population by race/ethnicity within the Census Division. ND: No data. NA: Not reportable due to small sample size.

Appendix Exhibit 3.

Characteristics of counties with and without underrepresented minority (URM) dentists

| U.S. County Calculations | URM Dentist Not Present | URM Dentist Present | P-Value | AI/AN Dentists Not Present | AI/AN Dentists Present | Black Dentists Not Present | Black Dentists Present | H/L Dentists Not Present | H/L Dentists Present | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristicsa | N | Mean | County population average | County population average | |||||||

| AI/AN population | 1,846 | 2.0% | 1.8% | 2.7%* | < 0.001 | 1.8% | 6.9%* | ||||

| Black population | 1,846 | 10.9% | 9.5% | 14.8%* | < 0.001 | 9.1% | 20.8%* | ||||

| H/L population | 1,846 | 8.8% | 7.1% | 13.6%* | < 0.001 | 7.2% | 18.1%* | ||||

| URM population | 1,846 | 21.8% | 18.5% | 31.1%* | < 0.001 | 21.3% | 32.2%* | 19.4% | 34.9%* | 20.2% | 30.7%* |

| Total population | 1,846 | 162,035 | 71,613 | 411,572* | < 0.001 | 136,585 | 664,462* | 92,535 | 538,010* | 89,950 | 572,083* |

| Median household income | 3,143 | $45,644 | $44,226 | $52,750* | < 0.001 | $45,411 | $52,986* | $44,837 | $53,410* | $44,662 | $55,237* |

| Dentist populationb | N | Mean | County average | County average | |||||||

| Total Dentists (2010) | 3,148 | 58.2 | 18 | 261* | < 0.001 | 47 | 406* | 27 | 358* | 25 | 381* |

| Dentists per 10,000 population (2010) | 2,884 | 3.9 | 3.5 | 5.5* | < 0.001 | 3.8 | 5.4* | 3.7 | 5.8* | 3.6 | 6.1* |

| Other county indicatorsc | N | Mean | County population average | County population average | |||||||

| Income Inequality indexd | 3,140 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.7* | < 0.001 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 4.5 | 4.7* | 4.5 | 4.7* |

| Residential segregatione | 2,780 | 31.3 | 30.3 | 35.6* | < 0.001 | 32.3 | 32.1 | 30.4 | 39.3* | 30.9 | 35.1* |

| Not proficient in English | 3,140 | 1.8% | 1.5% | 3.3%* | < 0.001 | 1.7% | 3.3%* | 1.6% | 3.3%* | 1.5% | 4.3%* |

| DHPSA statusf | N | Percent | Percent of counties | Percent of counties | |||||||

| No DHPSA | 808 | 25.7% | 27.5% | 17.2% | 26.2% | 12.4% | 26.7% | 16.9% | 26.8% | 15.8% | |

| Partial county DHPSA | 1,724 | 54.9% | 52.6% | 66.5% | 54.4% | 71.1% | 53.6% | 68.2% | 53.7% | 66.8% | |

| Full county DHPSA | 606 | 19.3% | 19.9% | 16.3% | 19.4% | 16.5% | 19.8% | 14.9% | 19.5% | 17.5% | |

Source: Authors’ analysis of data form the 2012 URM dentist survey and the sources listed in the table footnotes.

Information from the 2010–2012 ACS.

Information from the 2012 AHRF.

Information from the 2016 CHR.

Ratio of households in the 80th income percentile to those in the 20th income percentile.

Mean percentage of white or non-white households that would need to move to different geographic area to produce an even distribution across a county.

Information from the 2012 dental Health Professional Shortage Area (DHPSA) database.

p < 0.001

Contributor Information

Elizabeth A. Mertz, Associate professor in the Department of Preventive and Restorative Dental Services, School of Dentistry, and the Healthforce Center, at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF)

Cynthia Wides, Research analyst in the Department of Preventive and Restorative Dental Services, School of Dentistry, and the Healthforce Center, UCSF.

Aubri Kottek, Research analyst at the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy, Studies and the Healthforce Center, both at UCSF.

Jean Marie Calvo, Student in the School of Dentistry at UCSF.

Paul E. Gates, Chairman of the Department of Dentistry at the Bronx-Lebanon, Hospital Center and Dr. Martin L. King Jr. Health Center and clinical associate professor in the Department of Dentistry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York

Notes

- 1.Flores G, Lin H. Trends in racial/ethnic disparities in medical and oral health, access to care, and use of services in US children: has anything changed over the years? Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:10. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Improving access to oral health care for vulnerable and underserved populations. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Advancing oral health In America. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health and Human Services. Oral health in America: a report of the surgeon general [Internet] Washington (DC): HHS; 2000. [cited 2016 Oct 14]. Available from: http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/DataStatistics/SurgeonGeneral/Documents/hck1ocv.@www.surgeon.fullrpt.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine. In the nation’s compelling interest: ensuring diversity in the health-care workforce. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slater M, Iler E. A program to prepare minority students for careers in medicine, science, and other high-level professions. Acad Med. 1991;66(4):220–5. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199104000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wides CD, Brody HA, Alexander CJ, Gansky SA, Mertz EA. Long-term outcomes of a dental postbaccalaureate program: increasing dental student diversity and oral health care access. J Dent Educ. 2013;77(5):537–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells A, Brunson D, Sinkford JC, Valachovic RW. Working with dental school admissions committees to enroll a more diverse student body. J Dent Educ. 2011;75(5):685–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Dental Education Association. Summary of state loan forgiveness programs [Internet] Washington (DC): ADEA; 2015. Sep 11, [cited 2016 Oct 26]. Available from: http://www.adea.org/uploadedFiles/ADEA/Content_Conversion_Final/policy_advocacy/financing_dental_education/ADEA-Summary-of-Loan-Forgiveness-Programs.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camacho A, Zangaro G, White KM. Diversifying the health-care workforce begins at the pipeline: a 5-year synthesis of processes and outputs of the Scholarships for Disadvantaged Students program. Eval Health Prof. 2015 Dec 9; doi: 10.1177/0163278715617809. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health Resources and Services Administration. Health Careers Opportunity Program (HCOP) [Internet] Rockville (MD): HRSA; [cited 2016 Oct 26]. Available from: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/grants/diversity/hcop.html. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Health Resources and Services Administration. Centers of Excellence (COE) [Internet. Rockville (MD): HRSA; [cited 2016 Oct 26]. Available from: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/grants/diversity/coe.html. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bazargan N, Chi DL, Milgrom P. Exploring the potential for foreign-trained dentists to address workforce shortages and improve access to dental care for vulnerable populations in the United States: a case study from Washington State. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:336. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Health Resources and Services Administration. Pipeline programs to improve racial and ethnic diversity in the health professions: an inventory of federal programs, asssessment of evaluation approaches, and critical review of the research literature [Internet] Rockville (MD): HRSA; 2009. Apr, [cited 2016 Oct 26]. Available from: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/pipelineprogdiversity.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Health Resources and Services Administration. The rationale for diversity in the health professions: a review of the evidence [Internet] Rockville (MD): HRSA; 2006. Oct, [cited 2016 Oct 26]. Available from: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/diversityreviewevidence.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown LJ, Wagner KS, Johns B. Racial/ethnic variations of practicing dentists. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131(12):1750–4. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mertz EA, Grumbach K. Identifying communities with low dentist supply in California. J Public Health Dent. 2001;61(3):172–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2001.tb03386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meghani SH, Brooks JM, Gipson-Jones T, Waite R, Whitfield-Harris L, Deatrick JA. Patient-provider race-concordance: does it matter in improving minority patients’ health outcomes? Ethn Health. 2009;14(1):10730. doi: 10.1080/13557850802227031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mertz E, Calvo J, Wides C, Gates P. The black dentist workforce in the United States. J Public Health Dent. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12187. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mertz E, Wides C, Calvo J, Gates P. The Hispanic/Latino dentist workforce in the United States. J Public Health Dent. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12194. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mertz E, Wides C, Gates P. The American Indian/Alaska Native dentist workforce in the United States. J Public Health Dent. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12186. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mertz E, Wides C, Cooke A, Gates P. Tracking workforce diversity in dentistry: importance, methods and challenges. J Public Health Dent. 2016;76(1):38–46. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Dental Education Association. ADEA survey of dental school seniors, 2014 graduating class tables report. Washington (DC): ADEA; 2015. Feb, [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Dental Education Association. Enrollees by race and ethnicity in US dental schools, 2000 to 2015. Washington (DC): ADEA; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Dental Association. Distribution of dentists in the United States by region and state, 2009. Chicago (IL): ADA Survey Center; 2011. Table 12: primary occupation of all dentists by region and state, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ko M, Ponce NA. Community residential segregation and the local supply of federally qualified health centers. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(1):253–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01444.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shortt M, Hogg W, Devlin RA, Russell G, Muldoon L. Estimating patient demographic profiles from practice location. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(4):414–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 29.Sullivan Commission. Missing persons: minorities in the health professions: a report of the Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce [Internet] The Commission; Please provide. [cited 2016 Oct 27]. Available from: http://www.aacn.nche.edu/media-relations/SullivanReport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sweis LE, Guay AH. Foreign-trained dentists licensed in the United States: exploring their origins. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138(2):219–24. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allareddy V, Elangovan S, Nalliah RP, Chickmagalur N, Allareddy V. Pathways for foreign-trained dentists to pursue careers in the United States. J Dent Educ. 2014;78(11):1489–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mertz EA, Finocchio L. Improving oral healthcare delivery systems through workforce innovations: an introduction. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70(Suppl 1):S1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2010.00179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wetterhall S, Burrus B, Shugars D, Bader J. Cultural context in the effort to improve oral health among Alaska Native people: the dental health aide therapist model. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):1836–40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Health Resources and Services Administration. Teaching health center graduate medical education (THCGME) [Internet] Rockville (MD): HRSA; [cited 2016 Oct 27]. Available from: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/grants/teachinghealthcenters/ [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wall T, Nasseh K, Vujicic M. Most important barriers to dental care are financial, not supply related [Internet] Chicago (IL): American Dental Association; Health Policy Institute Research Brief; 2014. Oct, [cited 2016 Oct 17] Available from: http://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/HPIBrief_1014_2.pdf?la=en. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nivet MA. Commentary: diversity 3.0: a necessary systems upgrade. Acad Med. 2011;86(12):1487–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182351f79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vujicic M, Israelson H, Antoon J, Kiesling R, Paumier T, Zust M. A profession in transition. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(2):118–21. doi: 10.14219/jada.2013.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]