Abstract

Objectives

To contribute towards the current policy directive and recommendations outlined in the Francis Report (1) to strengthen relational aspects of hospital care and increase the use of a near real-time feedback (RTF) approach. This article offers insight into the challenges and enablers faced when collecting near real-time feedback of patient experiences with trained volunteers; and using the data to facilitate improvements.

Methods

Feedback was collected from staff and volunteers before, during and after a patient experience data collection. This took the form of both formal mixed methods data collections via interviews, surveys and a diary; and informal anecdotal evidence, collected from meetings, workshops, support calls and a networking event.

Results

Various challenges and enablers associated with the RTF approach were identified. These related to technology, the setting, volunteer engagement and staff engagement. This article presents the key barriers experienced followed by methods suggested and utilised by staff and volunteers in order to counteract the difficulties faced.

Conclusions

The results from this evaluation suggest that a near real-time feedback approach, when used in a hospital setting with trained volunteers, benefits from various support structures or systems to minimise the complications or burden placed on both staff and volunteers.

Keywords: Barriers and facilitators, Relational aspects of care, Real-time feedback, Volunteer-led data collection, Use of patient experience data

Highlights

-

•

A near real-time feedback approach to collect patient experience data in hospitals using trained volunteers.

-

•

Empirical and anecdotal evidence collected from hospitals to understand the success of the near real-time feedback approach.

-

•

Feedback from volunteers and staff explores barriers and facilitators of the approach and subsequent use of the results.

-

•

Various support systems and structures can mitigate challenges associated with a near real-time feedback approach.

Introduction

This article presents an overview of the challenges and promotors associated with near real-time data collections of patient experience and the use of the resulting data for improvement purposes. We present barriers and facilitators specifically associated with an approach using tablets and trained volunteers. Ongoing feedback was collected from volunteers and hospital staff to identify contextual factors that affect the success of the approach. Specifically, we sought to determine the most salient barriers and enablers or facilitators that affected the success of the near real-time feedback approach. This included, whether volunteers provided an effective way to collect data and whether staff engaged with weekly reports of patient experiences.

This article may serve as a starting point for hospitals considering to implement near-real time data collections of patient experience using trained volunteers to facilitate improvements.

Policy context

Patient experiences are considered to be a key component of high quality health care and provide one important avenue for measuring and improving the quality of patient-centred care [1], [2], [3]. Whilst patient experiences are important in and of themselves, they have also been shown to be correlated with other aspects of care quality. Specifically, they are related to safety and effectiveness [3], [4], [5] and are associated with better treatment outcomes, fewer complications and overall lower service use [6] as well as better staff experiences [7].

The need to systematically measure and improve patient experiences of care is consistently identified by policy makers [8], [9]. Near real-time feedback has been identified as a method, which may facilitate ongoing data collection and continuous review of results [10]. However, a near real-time feedback approach to measuring and improving patient experiences has not yet been systematically evaluated to understand the challenges associated with the approach.

Near real-time feedback and technology

Near real-time feedback in a hospital setting involves data collected from patients closer to the point of care. This involves asking patients about their experiences while they are still in hospital or shortly thereafter [11]. To ease the administrative burden and make data available for use more quickly, electronic equipment, such as bedside televisions, tablets or handheld devices are often used for near real-time feedback data collections [12].

Across England, various forms of near real-time feedback have been implemented in hospitals as of 2006 [13]. The Friends and Family Test (FFT), implemented as of 2012, provides an example of a near real-time feedback methodology. The implementation mode of the FFT varies across hospitals and includes comment cards, stationary kiosks featuring tablet computers and text messages patients receive shortly following discharge. The mode of administration has been shown to affect ratings provided by patients [14]. In addition, some modes place greater burden on staff, with regards to data collection and data entry [15].

While the mode-effects on response ratings have been explored, the use of a near real-time feedback approach has not been comprehensively evaluated to fully understand its potential to generate improvements to care. This research set out to address the gaps in the literature and simultaneously contribute towards the recommendations for improving hospital care for older patients, specifically those aged 75 and above, and those visiting the A&E departments as outlined in the recent healthcare policy recommendations [16], [17]. This focus within policy recommendations was derived from recent and independent inquires in to the quality of care, which highlighted these patient groups as in great need for improvements to care, especially around relational aspects of care [1]. Similarly, the focus on improving hospital care has been outlined in policy directives [1], [2], [3]. Therefore, our research sought to address the recommendations, with a focus on contributing towards improvements in hospital care for these patient groups.

Collecting feedback from older patients and those visiting the A&E department

Collecting patient experience data from older patients presents unique challenges as many patients present with long-term conditions and multi-morbidities that often affect hearing, speech, vision and cognitive processing [18]. While these challenges may not apply to patients visiting A&E departments, the transient environment, combined with recent or ongoing acute pain, shock and trauma experienced by patients make data collections equally challenging in A&E departments [19].

Therefore, no single mode of administration can be considered the best methodology of collecting data from these patient groups. In fact, as the needs and experiences differ greatly across these groups, a flexible or responsive data collection mode is needed, which can offer assistance to patients during the data collection process [20]. Well trained volunteers can provide a responsive approach to data collection from lesser heard groups. By rapidly determining any needs for assistance and providing help, data collections can be facilitated [21]. An additional benefit of the use of trained volunteers is that the data collection burden, which may otherwise fall on clinical staff, is reduced [20], [21].

We describe the barriers and facilitators encountered during a near real-time patient experience data collection approach using trained volunteers. The feedback collected from patients focused specifically on the relational aspects of care, which is also referred to as compassionate care, and was reported back to staff on a weekly basis to inform decision making for improvement purposes.

In addition to the factors affecting the data collection activities with volunteers, we address the barriers and facilitators identified by staff that affect planning for and implementing improvements based on a near real-time feedback data collection approach. All factors were derived as part of a comprehensive evaluation to assess the effectiveness of the above-described approach. While value judgements of the effectiveness and usefulness of the near real-time feedback approach are beyond the scope of this paper, we hope, this article may serve as a starting point for hospitals considering the implementation of a near real-time feedback approach using trained volunteers to inform ongoing improvements.

Methods

Patient data collection

As part of the larger research project, a survey was developed specifically for elderly hospital patients and those visiting the A&E department to address the current policy recommendations of improving care for these populations [1], [8], [9]. The survey was cognitively tested using tablets with current inpatients and A&E attendees at three hospitals in England. The final survey was then implemented by trained volunteers and weekly reports were provided to staff. Anyone was eligible to participate as a volunteer in the project, provided criminal record background checks were available and they had an interest in working with tablets and approaching patients. Two case study sites elected to use kiosks in the A&E department instead of trained volunteers. Please note, the survey development process is beyond the scope of this article but will later on be made available in accordance with the funding agency׳s timeline.

Prior to collecting data from patients, volunteers at each hospital were trained over a four hour session to collect feedback from patients. Training included a practical component and addressed seven competencies related to patient data collections such as following infection control procedures, assisting patients to complete the survey and escalating concerns. The full list of competencies can be found in Appendix 1.

Data collections were carried out at six hospitals in England, which served as case study sites. At each hospital, the A&E department, and up to four wards treating predominately elderly patients, such as dementia and stroke wards, participated in the data collections. Patients were only eligible to complete the survey once during their stay or visit. Reports were sent to each trust on a weekly basis, containing all patient feedback to date aggregated by month and week.

Staff and volunteer data collections

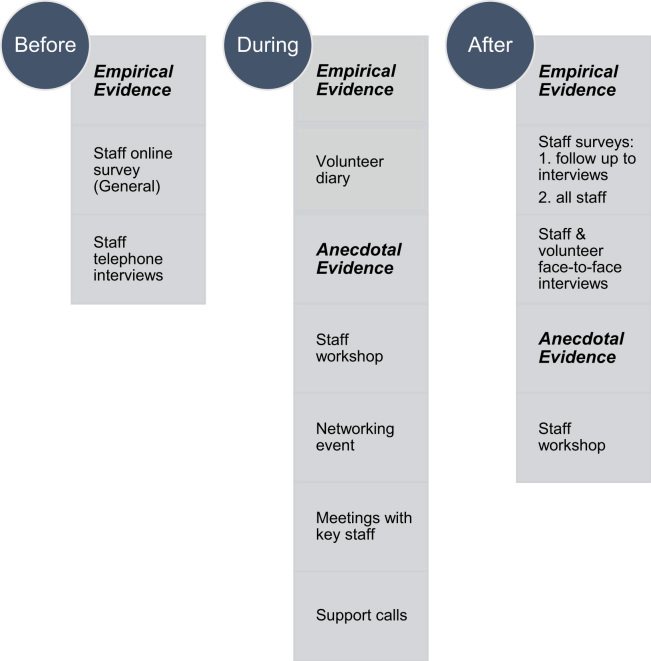

Alongside the patient data collections, data were also collected from staff and volunteers. These were implemented before, during and after the patient experience fieldwork period of ten months and provided us with the evidence to determine the most salient barriers and enablers or facilitators that affected the success of the near real-time feedback approach.

In addition to the formal mixed methods data collections, such as online surveys and interviews, we also met with staff at each case study site periodically. During these meetings, staff shared a variety of anecdotal evidence with us, which outlined the contextual factors that influenced the success of our approach. As this anecdotal evidence highlighted the lived experiences of staff implementing the near real-time feedback approach with the help of trained volunteers, we captured this feedback and present it, clearly labelled as such, alongside our empirical evidence. Figure 1 below presents an overview of all data sources and time points of their collection.

Figure 1.

Staff and Volunteer Data Sources Before, During and After Patient Data Collection.

Data collected from staff

Surveys and interviews

An online staff survey was made available to all staff working on wards and the A&E departments pre-and post the patient data collection. At each case study site, an additional two wards that were not involved with the project were selected as comparison groups. The pre-patient data collection survey, sent to 52 members of staff, was designed to understand the types and methods of patient experience data that were collected at the hospitals, as well as perceived barriers and enablers for using patient feedback. The post-patient data collection survey, sent to 45 members of staff, looked at staff׳s experiences with the project including any improvements that had been made as a result of the patient feedback and whether views of near real-time feedback and working with volunteers had changed. Figure 2 below gives an example of the questions and format of the staff survey, as viewed by staff members on the tablets.

Figure 2.

Staff Survey, Example Question.

Telephone interviews with staff were conducted to further explore the findings from the two online surveys. Fifty-two interviews were conducted pre-patient data collection and 24 post-patient data collection.

Workshops

Workshops were held at each case study site, three months into and again three months following the patient data collection. Frontline staff from each participating ward and the A&E department, along with senior staff, including the directors of nursing and matrons were especially encouraged to attend. The purpose of the workshops was to provide a dedicated space where staff could discuss and interpret the patient experience data. Action plans were derived for areas identified from the evidence as having a need for improvement. The workshop also gave the research team opportunity to gauge the levels of staff engagement with the near real-time data, and discuss any hindrances and enablers experienced alongside the data collections.

Networking event and meetings

A networking event was held for key staff from each hospital to meet other staff and discuss their experiences regarding the project and lessons learnt. The research team also held individual meetings with the key staff who had attended the networking event. This was to provide each hospital with support specific to their site and to provide a space for staff to share any experiences or concerns with the research team.

Data collected from volunteers

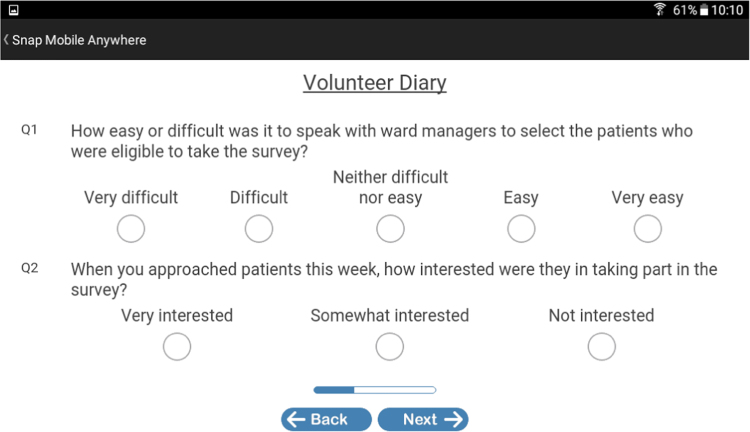

Diary

A volunteer diary was continuously available in an online survey format on the tablets accessed by the volunteers. The diary was designed to understand the implementation and context of near real-time feedback from the volunteer׳s perspective. Volunteers were encouraged to complete the diary once per week. Figure 3 below provides an example of how the volunteers viewed the volunteer diary on the tablets.

Figure 3.

Volunteer Diary, Example Questions.

Interviews

In-person interviews were conducted with two volunteers at each hospital. The interviews focused on understanding volunteers’ experiences with the near real-time feedback data collections, including conditions for success and barriers, as well as any observed changes throughout the data collection period.

Support calls

Feedback was also gathered through scheduled support calls with volunteers at each hospital. These were offered three times throughout the 10 month patient data collection period. Volunteers were also encouraged to contact the research team with any questions or concerns at any time.

Results

The following key barriers and facilitators associated with the near real-time feedback data collection approach were identified. We present the barriers and facilitators as related to technology, the data collection setting, staff and volunteer engagement. To illustrate the meaning of barriers and facilitators for staff and volunteers, we present evidence in the form of participants’ own words or averages from survey data collections, where available.

Technology

The main barriers experienced with the technology during data collections were related to familiarity, connectivity and positioning. Specifically, the familiarity with the equipment, including tablets provided an initial challenge both for patients and staff. Not all elderly patients were comfortable using the tablets independently. Volunteers provided various levels of assistance, including holding tablets, reading questions and answer options aloud and entering responses. Staff initially reported tablets shutting down during use, when the survey software was scheduled to be updated. During the initial month of data collection, some tablets did not transmit their saved survey responses to the research team due to a loss of 3G or wireless connectivity. Some staff also encountered problems maintaining and charging the equipment. Finally, the two case study sites using kiosks in the A&E department struggled with their positioning as only few surveys were completed on the stationary devices.

The facilitators related to technology, which also addressed the barriers detailed above included ongoing technical support, ensuring sufficient resource capacity, and a certain level of flexibility within the data collection approach. An important facilitator was the provision of ongoing technical support provided both locally and remotely. The hospitals’ technical support team was especially helpful in setting up the initial network connections for tablets. The research team then provided remote technical support and examined the equipment during site visits, as necessary. It was also beneficial to have additional tablets on hand to ensure that data collections were not affected negatively by faulty technology.

Flexibility of the approach to data collection was also considered to be a success for the near real-time feedback approach. For example, when the two hospitals that had initially selected to use stationary kiosks in their A&E departments discovered that the approach only generated a low number of responses, they switched to using tablets administered by trained volunteers. This switch increased the number of responses obtained for both case study sites. One site increased from an average of four to 45 responses collected per month and another site increased their responses from zero to an average of 18 per month using the tablet and volunteers instead of a stationary kiosk.

Setting

Barriers experienced by staff also related to the unique characteristics of the A&E department and the elderly care ward environments. Both were perceived to provide challenging environments for data collections. Specifically, in the A&E departments, volunteers often reported not speaking to as many patients as they would have liked due to patients being in severe pain or distress. Others had not yet been seen by a doctor or nurse, which meant they had yet to experience relational aspects of care that they could report on. Elderly care wards were often smaller wards with less patient turnover. While patients were less likely to be in acute pain, not all had the capacity to consent or sufficient energy to participate in the survey. Volunteers reported a “sense of frustration” when no or few patients were available to be surveyed.

The key facilitator, which contributed towards the resolution of challenges associated with the data collection settings, was the collection of continuous feedback from volunteers to identify challenges or frustrations as they arose. If necessary, this information could be shared with the site lead or volunteer co-ordinator who quickly resolved the barriers at the local level.

Volunteer engagement

A variety of barriers were encountered that affected the engagement of volunteers in the near real-time data collections. Continued volunteer availability constituted a great challenge through the ten month data collection. While some volunteers elected to discontinue their work with the data collections due to other interests or feeling uncomfortable approaching and surveying patients, others were being moved to other tasks by volunteer co-ordinators, as prioritised by the hospitals. Other barriers experienced by volunteers were perceived pressures to complete a certain number of interviews per shift. While the research team explained that interview length would likely vary during the volunteer training, volunteers held clear expectations regarding the number of surveys that could be completed per shift. When these expectations were not met due to patient availability or some patients wanting to talk more, volunteers experienced a sense of pressure. For example, one volunteer explained, “Still a problem getting on to some wards before 10.00 am due to patient care time and have to get out for meal times which causes a bit of a panic.”

Throughout the ten month data collection phase, volunteers were also unavailable due to a variety of other commitments. For example, student volunteers were not available during the summer months and older volunteers were more likely to be unavailable at short notice due to appointments or illness during the winter months.

The key facilitators to continued volunteer engagement were related to support from staff, ongoing recruitment activities and finding volunteers who were comfortable approaching patients or helping them become comfortable doing so. It is especially important for volunteers to feel comfortable approaching patients and surveying them. In some instances staff formed informal mentoring relationships with younger volunteers which helped them to develop their confidence. For example, one staff member said to a volunteer, “I have taken you under my wing.”

To further reduce the pressures that may be experienced by volunteers, some staff strived to set realistic expectations about the number of surveys that can be completed during a shift. One volunteer co-ordinator explained, “Some patients want to talk to someone and then it can take up to an hour to finish a survey.” Other facilitators for volunteer retention were the provision of certificates of research participation provided by the research team and staff recognising the volunteers’ contributions at hospital events.

Finally, due to volunteer turnover, staff found it essential to continue the volunteer recruitment process throughout the study. Some case study sites reported success after compiling a “person specification, similar to a job specification” that helped them outline the desired volunteer characteristics.

Staff engagement

The barriers experienced by staff related primarily to the use of the near real-time feedback. Specifically, staff described having very limited time available to engage with the weekly results. Often, the feedback was reviewed by staff during their break times. Frontline staff generally did not have access to a computer as part of their regular duties. Therefore, access to weekly reports proved to be difficult for staff. Due to the limited time available, staff also found an interactive reporting option to be “cumbersome and not user friendly”.

To assist staff in utilising near-real time feedback of patient experiences, the reporting format held the key to success. By making the reports printable and by offering a static dashboard, summarizing progress and areas for improvement at-a-glance, staff were provided with the data they needed to consider improvements on an ongoing basis. These types of reports were also more manageable for staff who used their free time to review the results.

A key driver for the successful action planning and implementation of improvements was having senior clinical staff, such as the director of nursing, working alongside frontline staff in identifying and prioritising actions for improvements. In the action planning process, staff found free-text comments written by patients very helpful. These were more easily accessible to staff than frequency counts and percentages summarising results from closed-ended survey questions. Seeing patients’ own comments brought the experiences to life for frontline staff and added a “sense of urgency” to address them in improvement efforts.

Discussion

While the six case study sites differed greatly in their geographical location and their performance on national patient experience surveys, similar barriers and facilitators were experienced across the six hospitals. Barriers related to technology, the setting, as well as volunteer and staff engagement.

Ongoing and in-person support played a key role in resolving challenges related to technology, the setting, as well as volunteer and staff engagement. To provide tailored support to volunteers, the establishment of mentoring programmes should be considered. This would provide another dedicated point of contact for volunteers and allow for even earlier detection of challenges experienced. In addition, volunteers might gain additional personal benefits from their mentors, such as a better understanding of related careers, as well as increases in confidence and self-efficacy.

To support staff in using the ongoing reports of patient experiences, researchers may consider facilitating focus groups with staff prior to beginning a near real-time feedback approach. Through discussions, both familiar and preferred reporting formats can be explored. Moreover, by providing staff with concrete examples of what a report may look like, researchers can enhance the content and layout of the report to match staff׳s preferences. This would also give researchers a chance to understand when and how staff currently use reports of patient feedback and how much time is dedicated to the review and use of feedback.

Volunteers present a great resource for hospitals and can be drawn upon to facilitate patient experience data collections. However, volunteers and staff may also experience various barriers associated with a near real-time feedback approach. When barriers are addressed in a timely manner, a near real-time feedback approach using trained volunteers can be successful. Both ongoing support and relationships play a key role in the success of the approach.

Conclusions

Similar to other European healthcare systems, the English NHS operates under resource constraints, with 2016 marking the second year for which a financial deficit was reported [22], [23]. In addition, further demands on the NHS are anticipated, as the population it serves continues to age and experience complex conditions and multi-morbidities [24].

As resource constraints on healthcare systems increase, maintaining and improving the quality of services provided will be a key focus [25]. Therefore, this research is especially timely as it investigates the factors that affect the success of a near real-time feedback approach using trained volunteers. These factors should also be of interest to policy makers in light of the current policy directive for a more widespread use of near real-time feedback [1], [2], [3], [4]. The near real-time feedback approach offers a relatively low-cost way of capturing patient experiences while also providing frequent and ongoing reports to staff, which can be used to make evidence-based improvements to practice.

Using volunteers is a relatively resource efficient approach for data collection. However, a certain amount of direct support and engagement from staff is required [11]. To provide staff with time to support volunteers and make the most of patient feedback, they need to have buy-in from their ward or departmental leaders, as well as senior leadership at their organisation.

While our work offers initial guidance for both hospitals and policy makers, it also contains a number of limitations, which can be addressed by future research. Specifically, our research was only conducted at a small number of case study sites in England. While the findings were consistent across these sites, they may not be representative of other hospitals in England and internationally. Future research should also examine the implementation of a near real-time feedback approach in other care settings such as community services. In addition, further research should seek to understand the impact of volunteer interactions on patient experiences of care.

Author statements

Funding

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research Programme (project number 13/07/39). The views and opinions therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HS&DR Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethical approval

The East of Scotland Research Ethics Service reviewed this research and provided a favourable opinion in August of 2014 (14/ES/1065).

Acknowledgements

We thank all volunteers, staff, the research team, and advisory group members who worked with us. We also thank the collaborators at the six case study sites. There are no conflicts of interest for this research.

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research Programme (Project number 13/07/39). The views and opinions therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HS&DR Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health. This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Appendix 1

Data Collection Competencies Covered in Volunteer Trainings

-

(1)

Using and maintaining the tablet, including upload of survey responses.

-

(2)

Understanding the types of assistance that may need to be provided to patients and administering the survey.

-

(3)

Following standard hand hygiene and infection control procedures.

-

(4)

Obtaining informed consent and understanding what constitutes capacity to consent and that this may change for elderly patients throughout the day.

-

(5)

Checking in with staff before data collections to obtain a list of patients who are considered to have capacity to consent.

-

(6)

Explaining the study׳s purpose, providing patient information sheets and reading them aloud, if asked by a patient.

-

(7)

Escalating concerns, in accordance with the hospital policy, if explicitly requested by a patient.

Appendix 2

Ongoing Support Provided to Volunteers

-

(1)

After volunteers completed a shift of data collections, the volunteer co-ordinators based at the hospitals checked in with them about their experiences.

-

(2)

Volunteers were also asked to complete a brief and anonymous online diary of their data collection experiences every week. The research team then communicated any identified challenges to the hospital staff and/or the volunteer co-ordinator on a weekly basis.

-

(3)

Volunteers were also aware of a peer researcher at each hospital. The peer researcher was also a volunteer collecting data for this project, who was available to answer questions and liaise with the research team.

-

(4)

Volunteers were encouraged to directly contact the research team any time with any questions. This included the chance to participate in monthly support calls with the research team where they could share their experiences.

References

- 1.Francis R. The Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust public inquiry. Natl Arch. 2013 〈http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20150407084003〉 [http:/www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com/report] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Silva D. Help Meas Person-centred care Health Found. 2014 〈http://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/HelpingMeasurePersonCentredCare.pdf〉 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darzi A. Quality and the NHS next stage review. Lancet. 2008;10(371):1563–1564. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60672-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincent C., Amalberti R. Springer; London: 2016. Safer Healthcare: strategies for the real world. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black N., Varaganum M., Hutchings A. Relationship between patient reported experience (PREMs) and patient reported outcomes (PROMs) in elective surgery. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(7):534–542. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doyle C., Lennox L., Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):e001570. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Price R.A., Elliott M.N., Zaslavsky A.M. Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality. Med Care Res Rev. 2014;71(5):522–554. doi: 10.1177/1077558714541480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raleigh V.S., Hussey D., Seccombe I., Qi R. Do associations between staff and inpatient feedback have the potential for improving patient experience? An analysis of surveys in NHS acute trusts in England. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(5):347–354. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.028910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bridges J., Fuller A. Creating learning environments for compassionate care: a programme to promote compassionate care by health and social care teams. Int J Older People Nurs. 2015;1(1):48–58. doi: 10.1111/opn.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reeves R., West E., Barron D. Facilitated patient experience feedback can improve nursing care: a pilot study for a phase III cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garrisson M., Wolf J.A. The role of the volunteer in improving patient experience. The Beryl Institute; Dallas, TX: 2016. 〈http://www.theberylinstitute.org/news/284517/The-Role-of-the-Volunteer-in-Improving-Patient-Experience-Explored-by-The-Beryl-Institute-.htm〉 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicholls J. From data to action: the challenges of driving service improvement. Patient Exp Portal. 2012 〈http://patientexperienceportal.org/article/from-data-to-action-thechallenges-of-driving-service-improvement〉 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naylor C., Mundle C., Weaks L., Buck C. Volunteering in health and care: securing a sustainable future. Kings Fund. 2013 〈http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/volunteering-in-health-and-social-care-kingsfund-mar13.pdf〉 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sizmur S., Graham C., Walsh J. Influence of patients׳ age and sex and the mode of administration on results from the NHS Friends and Family Test of patient experience. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1355819614536887. [Jun 27:1355819614536887] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali K.J., Farley D.O., Speck K., Catanzaro M., Wicker K.G., Berenholtz S.M. Measurement of implementation components and contextual factors in a two-state healthcare quality initiative to reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(S3):S116–S123. doi: 10.1086/677832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Truths H. The Journey to putting patients first: volume one of the government response to the Mid Staffordshire NHS foundation trust public inquiry 2. Department of Health; 2014. 〈https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/mid-staffordshire-nhs-ft-public-inquiry-government-response〉 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robert G., Cornwell J. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement; Coventry, UK.: 2011. What Matters To Patients? Developing the Evidence Base for Measuring and Improving Patient Experience.〈https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/administration-and-support-services/library/public/vancouver.pdf〉 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murrells T., Robert G., Adams M., Morrow E., Maben J. Measuring relational aspects of hospital care in England with the ‘Patient Evaluation of Emotional Care during Hospitalisation’ (PEECH) survey questionnaire. BMJ Open. 2013;1(1):e002211. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brostow D.P., Hirsch A.T., Kurzer M.S. Recruiting older patients with peripheral arterial disease: evaluating challenges and strategies. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:1121. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S83306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson R., Kuczawski M., Mason S. Why is it so difficult to recruit patients to research in emergency care? Lessons from the AHEAD study. Emerg Med J. 2016;1(1):52–56. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2014-204401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright C., Davey A., Elmore N. Patients׳ use and views of real‐time feedback technology in general practice. Health Expect. 2016 doi: 10.1111/hex.12469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Dowd A. Deficit in NHS provider sector triples in a year to£ 2.45 bn. BMJ. 2016;353:i2904. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunn P., McKenna H., Murray R. O’Dowd A. Deficit in NHS provider sector triples in a year to£ 2.45 bn. BMJ. 2016;353:i2904. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashby S., Beech R. Addressing the healthcare needs of an ageing population: the need for an integrated solution. Int J Collab Res Intern Med Public Health. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 25.England NHS. Five Year Forward View. Available from 〈https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf〉; 2014.