SUMMARY

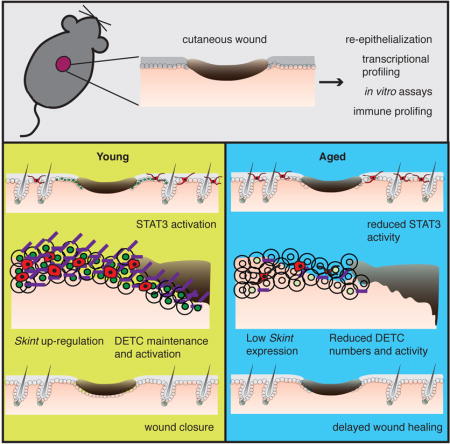

Aged skin heals wounds poorly, increasing susceptibility to infections. Restoring homeostasis after wounding requires the coordinated actions of epidermal and immune cells. Here we find that both intrinsic defects and communication with immune cells are impaired in aged keratinocytes, diminishing their efficiency in restoring the skin barrier after wounding. At the wound-edge, aged keratinocytes display reduced proliferation and migration. They also exhibit a dampened ability to transcriptionally activate epithelial-immune crosstalk regulators, including a failure to properly activate/maintain dendritic epithelial T-cells (DETCs), which promote re-epithelialization following injury. Probing mechanism, we find that aged keratinocytes near the wound edge don’t efficiently up-regulate Skints or activate STAT3. Notably, when epidermal Stat3, Skints or DETCs are silenced in young skin, re-epithelialization following wounding is perturbed. These findings underscore epithelial-immune crosstalk perturbations in general, and Skints in particular, as critical mediators in the age-related decline in wound-repair.

Keywords: Aging, wound healing, re-epithelialization, Skint, DETC, epidermal-immune cell cross-talk, STAT3

eTOC

Progressive loss of communication between epithelial and immune cells in the skin underlies the slow down in wound healing associated with aging.

INTRODUCTION

Although paper-thin, the epidermis acts as the key physical barrier to the external environment. It prevents dehydration, blocks damaging ultraviolet radiation, and guards against pathogens and infection. To maintain proper tissue homeostasis and barrier function, epidermis must be constantly renewed and repaired by proliferative progenitor keratinocytes which periodically exit the innermost basal layer, and execute a terminal differentiation program, eventually being sloughed as dead squames from the body surface (Fuchs, 2007).

Following injury, a wound healing response is triggered to rapidly repair epidermis and restore the skin barrier. While repair is ongoing, the damaged skin is exposed to pathogens, and delays in the re-epithelialization process can lead to higher incidence of infection and chronic wound formation. Wound healing is a complex biological process that involves four independent, yet interconnected processes beginning with: 1) coagulation of platelets to form an eschar (scab) to generate a temporary barrier; 2) activation of resident T-cells and infiltration of macrophages, monocytes and neutrophils in immune surveillance; 3) local proliferation of epidermal keratinocytes at the wound edge, followed by their migration into the wound bed to repair the damaged barrier and restore homeostasis; 4) resolution of the wound through repair of underlying damaged dermis and remodeling of its extracellular matrix (Gurtner et al., 2008).

In many tissue types and organs, the ability to repair wounds declines with age (Kennedy et al., 2014; Kenyon, 2010; López-Otín et al., 2013; Oh et al., 2014). Skin is particularly vulnerable to age-related decline, exhibiting increased dryness, roughness, hair loss, impaired wound healing and increased susceptibility to infection and chronic wounds (Ashcroft et al., 2002; Keyes et al., 2013; Nishimura et al., 2005; Velarde et al., 2015). Poor wound healing in aged adults has been documented for well over a century, and age-related declines in cutaneous wound-healing contribute to a variety of health complications, and to decreased lifespan. Despite its importance, however, the molecular underpinnings for the age-related decline in wound-repair are not well understood, impeding the prospects for therapeutic advances.

Formation of a proper epithelial barrier after acute injury requires the coordinated action and cross-talk of keratinocytes and immune cells at the wound site. So-named due to their morphology and epidermal location, dendritic epithelial T-cells (DETCs) inhabit the epidermis and account for a majority of T-cells in the skin epidermis. Born in the developing fetal thymus and then migrating to the epidermis, ~90% of DETCs express an invariant Vγ5Vδ1 (also known as Vγ3Vδ1) T-cell antigen receptor (TCR) (Lewis et al., 2006). Vγ5Vδ1 DETCs reside in the innermost basal layer of the epidermis, but can extend their dendrites into the suprabasal layers, a feature thought to be used for surveillance in guarding against pathogenic infection (Chodaczek et al., 2012; Hayday, 2009).

DETCs have been implicated in maintaining skin function, including epidermal homeostasis, tumor surveillance and wound repair (Heath and Carbone, 2013). Upon injury, DETCs bordering the wound edge retract their dendrites, become rounded and begin to produce epidermal mitogens such as FGF7/10 and IGF1, facilitating wound re-epithelialization (Jameson et al., 2002). Mice lacking the T-cell receptor δ subunit (TCRδ) show pronounced delays in cutaneous wound healing (Itohara et al., 1993; Jameson et al., 2002). However, these mice lack all γδ T-cells, including both epidermal DETCs and dermal Vγ4Vδ1 T-cells; each secretes a different repertoire of factors and cytokines that could impact wound-repair (Gray et al., 2011; Sumaria et al., 2011).

Mice that selectively lack Vγ5Vδ1 DETCs have been described (Boyden et al., 2008; Turchinovich and Hayday, 2011), but have not been tested for possible defects in wound repair. They harbor a null mutation in selection and upkeep of intraepithelial T-cells 1 (Skint1), lack canonical Vγ5Vδ1 expressing DETCs. Skint1, is the founding member of a family (Skint1-11) of butyrophilin-like proteins with containing transmembrane spanning domains and extracellular IgV, and IgC domains (Mohamed et al., 2015). During development, Skint1 is expressed by thymic epithelial cells, promoting functional differentiation of DETC progenitors (Boyden et al., 2008). A number of Skint family members are also expressed in the skin epidermis and intestinal epithelium (Boyden et al., 2008). However, their functions in these adult tissues remain unexplored.

In the present study, we were drawn to DETCs and Skints through an unbiased approach in defining the age-related defects that underlie impaired re-epithelialization after skin wounding. Using mouse as a model system, we first showed that re-epithelialization to restore the skin barrier is delayed in aged mice. We found that aged skin epidermal keratinocytes are less transcriptionally dynamic after wounding, and fail to regulate key processes necessary for wound-repair. Many genes facilitating interactions with immune cells weren’t activated properly in basal keratinocytes at the wound-edge of aged skin. Most notable were Skint genes. When we investigated the DETCs, we found that our unwounded aged mice harbored Vγ5Vδ1 DETCs, and hence differed from Skint1 null mice. However, the DETCs displayed an age-related, wound-specific defect in their behavior.

Our findings brought to the forefront prior speculation, never tested, that SKINTs or some other interacting ligand(s) on wound-proximal keratinocytes might function in the DETC response to injury (Havran et al., 1991; Jameson et al., 2004; Komori et al., 2012). We therefore turned to addressing whether Skints might function in adult tissue homeostasis and wound-repair, and whether perturbations in SKINTs might affect DETCs and/or their communication with epidermal cells to account for some of the age-related defects in wound healing.

Specifically, we discovered that young mice conditionally knocked down for Skint3 and Skint9 in epidermal keratinocytes display defects in wound-repair and in wound-related DETC behavior. Similarly, we found that young mice which a) lack Vγ5Vδ1-DETCs altogether, or b) display DETCs, but either lack the Skint3-4-9 gene cluster or are epidermally knocked down for individual Skints, also exhibit delays in skin re-epithelialization during wound-repair. Finally, we identified conserved STAT3 binding motifs in Skint promoters and showed that STAT3-signaling and one of its upstream activators, Interleukin-6, are diminished in aged, wounded skin. Moreover, Stat3-null mice display DETC and wound repair defects which are strikingly similar to those in aged mice, and that elevating this signaling pathway can stimulate Skint expression as well as improve epidermal migration in aged skin. These findings not only demonstrate proof of principle, but in addition, offer new promise for therapeutic intervention in elderly individuals who need a boost in restoring skin barrier acquisition after injury.

RESULTS

Aged Animals Maintain a Functional Epidermis in Homeostasis

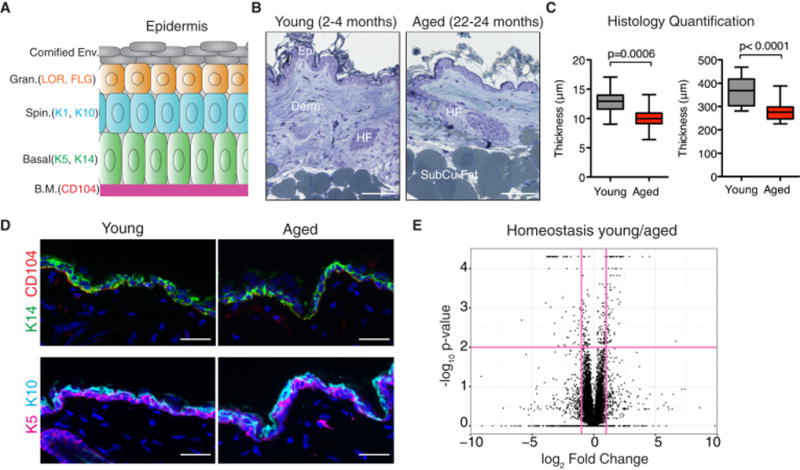

The dorsal (backskin) epidermis of young (2–4 month) mice is a stratified epithelial tissue composed of dead outer stratum corneum cells, differentiating granular and spinous layers, and an inner proliferative basal layer attached to an underlying basement membrane (Figure 1A). The corresponding epidermis of aged (22–24 month) female C57BL6/J animals also displayed these morphological features, although an ~20% reduction in epidermal thickness was accompanied by an equivalent dermal thinning (Figures 1B and 1C). Immunofluorescence microscopy confirmed the presence of a seemingly normal differentiation program in aged mouse skin (Figure 1D and data not shown). In all, we carried out immunostaining for basement membrane protein β4 integrin (CD104), basal keratins 5 and 14 (K5 and K14), spinous layer keratins (K10 and K1), wound-response keratins (K6 and K17) and granular layer proteins filaggrin and loricrin, and observed no obvious structural differences between aged and young skin.

Figure 1. Young and aged epidermis. A).

Schematic illustrating the differentiated layers of the epidermis. B) Images of semi-thin sections of young (2–4 months old) and aged (22–24 months old) skin stained with toluidine blue. Abbreviations: Epi, epidermis; Derm, dermis; HF, hair follicle; SubCu Fat, subcutaneous fat. Scale bars=100μm. C) Quantification of the thickness of epidermis and dermis of young and aged skin. N=8. Students t-test was used to measure statistical significance. D) Immunofluorescence images of young and aged skin labeled with antibodies (Abs) against keratin 14 (K14), β4-integrin (CD104), keratin 5 (K5) and keratin 10 (K10) [secondary Abs are color-coded as shown]. Sections were co-stained with DAPI (blue) to visualize nuclei. Scale bars=25μm. E) Volcano plot of in vivo RNA-seq data comparing young:aged basal keratinocyte transcripts. Vertical red colored lines denote fold changes greater ±2 fold. Horizontal red line denotes p-value > 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Table S1.

To probe more deeply for differences between young and aged epidermal keratinocytes in vivo, we used fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) to purify basal layer keratinocytes (α6-integrinhighCD34negativeSca1high) from young and aged mouse skin, followed by deep sequencing (RNA-seq) of their mRNAs. Comparative expression analysis of duplicates of RNA-seq data revealed 74 genes that were ±2-fold differentially expressed (q<0.05) between young and aged keratinocytes (Figure 1E and Table S1). Overall, however, their transcripts (56 up-regulated, 18 down-regulated) were relatively modestly changed (1.9-fold average), indicating that under homeostatic conditions, aged animals maintain an epidermis that is architecturally and transcriptionally similar to that of young mice.

Aged Skin is Slow to Re-epithelialize Wounds Following Injury

We next challenged the epidermis to wounding, to see if the epidermis of aged mice was able to mount an injury response comparable to younger mice. Six millimeter punch biopsies created full-thickness (epidermis + dermis) wounds on the animals’ backs, which typically healed by 7 days (d7). As shown in the images from representative experiments, young mice consistently closed their wounds faster than their aged counterparts, with little difference on the macroscopic level in wound contraction (Figure S1). When quantified over five independent wound studies, the biggest differences in wound area were consistently between d3 and d5 post wounding, where the rate of wound closure was always faster in young animals (Figure S1B and C).

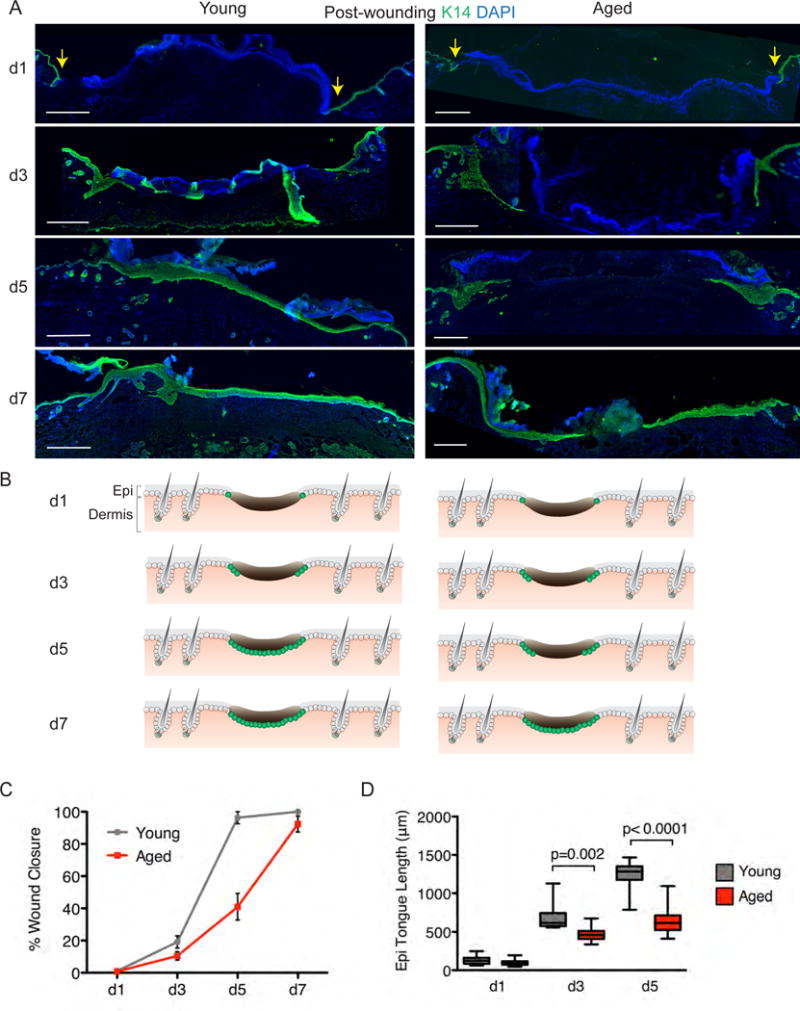

To visualize the re-epithelialization process, wounded skins from mice were collected at intervals and subjected to K14 immunostaining (Figure 2A). Wounds at d1 post-wounding exhibited little or no signs of re-epithelialization, but thereafter, an epithelial tongue of migrating keratinocytes was visible underneath the eschar (Figure 2C). Beginning at d3 and culminating at d5, a marked delay in re-epithelialization was evident in the wound beds of aged mice. At d5 when re-epithelialization had closed the wound (96±4%) in young animals, the epithelial tongues from opposing sides of the wounds of aged animals had migrated less than half way (41±8%) into the wound site (Figure 2C). By d7, aged wounds were still not completely closed (92±5%).

Figure 2. Re-epithelialization of young and aged cutaneous wounds. A).

Immunofluorescence images of the temporal re-epithelization process that occurs following skin wounding (t=0) in young and aged mice. Sections are immunolabeled for basal epidermal keratinocytes (K14) and co-stained with DAPI. Scale bar=500μm. “S” denotes scab and yellow arrows denote wound edge. B) Schematics depicting progress of the re-epithelialization process at time-points indicated in young and aged animals. While wounds heal, the process is delayed in aged skin. C–D) Quantification of re-epithelialization in young and aged wounds (C) and of the length of the tongue of epidermal keratinocytes that migrate in from the wound edges during the wound-repair process (D). Students t-test was used to measure statistical significance, N=5. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figures S1 and S2.

The delay in wound closure in aged animals corresponded well to the decreased migration of the epithelial tongue under the eschar, as quantified in Figure 2D. Moreover, signs of epidermal responsiveness, as judged by enhanced epidermal thickening and associated wound-induced keratin K17, extended further from the wound site in young than in aged mice (Figure S2).

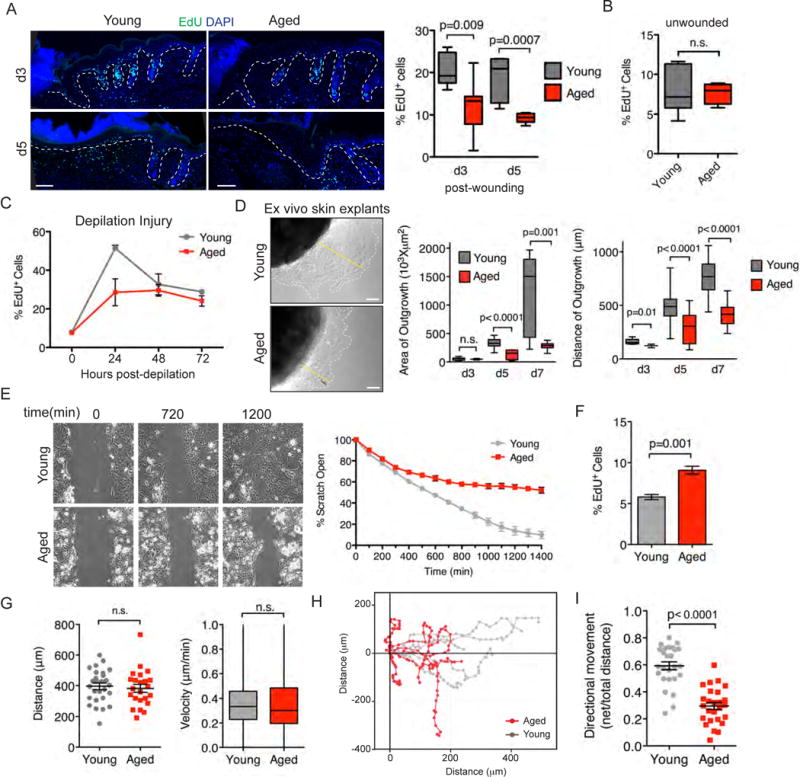

Declines in Proliferative Capacity of Aged Keratinocytes

To understand the basis of the delayed re-epithelialization of wounds in aged animals, we assayed the functional abilities of young and aged keratinocytes to proliferate and migrate in response to injury. To this end, at intervals after wounding, mice were pulsed with 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) for 3 hours before harvesting and analyzing their skins. As quantified both in tissue sections of wounded skin and basal keratinocytes analyzed by flow cytometry, significantly fewer EdU labeled cells were seen in aged versus young epidermis at d3 and d5 post-wound time-points (Figure 3A). This difference was not seen under homeostatic conditions, where basal levels of proliferation were similar (Figure 3B). Together, these findings suggest that the defect is rooted specifically in the wound-response. Consistent with our punch wound studies, we also observed a notable decrease in proliferation in aged versus young epidermal keratinocytes from skins that were analyzed 24hrs after waxing to depilate the skin, a procedure that stimulates basal layer proliferation analogous to punch wounds (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Functional capabilities of young and aged keratinocytes. A).

Immunofluorescence images of young and aged wounds at d3 and d5 time-points with proliferating cells labeled with EdU (green). Dashed lines denote epidermal/dermal boundaries. Scale bars=100μm. Quantifications are of EdU incorporation from independent samples. N=7. B) Proliferation of young and aged basal layer keratinocytes under homeostatic conditions. Animals were pulsed with EdU and collected after 24 hours. EdU incorporation was measured by flow cytometry. Young (7.9±1.2%) and aged (7.6±0.5%), p=0.82, N=6. C) Proliferation of young and aged basal layer keratinocytes after depilation. EdU was 24 hours prior to collection. Graph shows percentage of basal layer keratinocytes with EdU incorporation post-depilation at indicated time-points. At 24hours post-depilation young (51.5±1.5%) and aged (28.6±7.0%), p=0.018, N=4. D) DIC images of explant cultures from young and aged tissue biopsies. Dashed lines denote the borders of keratinocyte outgrowth; yellow lines denote radial distances migrated. E=explant. Scale bars=10μm. N=12. Quantifications are of the area and distance of outgrowth of keratinocytes in explants during a 7 day time-course. E–I) Scratch wound assays. E) Migration into 600μm scratch wounds of aged and young skin keratinocytes was measured by time-lapse video-microscopy. Shown are DIC images of time-points indicated. Quantifications of wound closure are shown in the graph at right. F) EdU incorporation during the interval of the time-lapse imaging. G) Comparative measurements of distance migrated and velocity. H) Migration plots of individual cells during the wound closure. I) EdU incorporation during the interval of the time-lapse imaging. Students t-test was used to measure statistical significance. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S3 and Supplemental Movies S1 and S2.

Aged Keratinocytes Exhibit Intrinsic Defects in Wound Induced Migration

The age-related reduction in wound-induced proliferation did not appear to be attributable to an increased incidence of apoptosis, as no differences in activated caspase 3 staining were noted (data not shown). However, over d7 ex vivo, both the area and distance of keratinocyte outgrowth were reduced in aged compared to young skin explants (Figure 3D). Finally, when assayed by time-lapse imaging for their abilities to migrate into the ~600μm space created by a scratch wound, cultured keratinocytes from aged skin showed a significant delay in migration and scratch closure, without a corresponding reduction in proliferation (Figures 3E and 3F; Movies S1 and S2). Additionally, when we tracked individual cells, both young and aged keratinocytes migrated at the same speed and distances (Figure 3G). Strikingly however, young keratinocytes exhibited more robust directional migration (higher horizontal movement into the open area of the scratch) than their aged counterparts (Figures 3H and 3I).

Similar intrinsic age-related migration delays were observed using Boyden chamber assays, in which serum-starved keratinocytes in the top chamber migrated to the bottom chamber containing feeder cell conditioned media (Figure S3A). In vitro adhesion assays also revealed defects in the ability of aged keratinocytes to attach to fibronectin, collagen and laminin coated plates and reduced cell spreading on these substrates (Figures S3B–S3D). Finally, when basal keratinocytes were FACS isolated from aged and young mice and compared over longer time periods in vitro, aged keratinocytes clearly displayed reduced colony forming efficiency and formed smaller colonies (Figures S3E and S3F). These results provided compelling evidence that the delayed wound re-epithelialization in aged mice was rooted at least in part in intrinsic defects in the proliferative and migratory behavior of aged epidermal keratinocytes.

Aged Skin Keratinocytes In Vivo Display a Less Dynamic Transcriptional Response to Wounding Than Their Youthful Counterparts

In light of the prominent age-related differences in wound re-epithelialization in vivo and intrinsic differences measured in vitro, we next focused on differences in gene expression that occur in epidermal keratinocytes at the wound edge. To capture responses at peak age-related wound-repair differences, we profiled at d3 after wounding, when both young and aged keratinocytes were actively re-epithelializing their wounds. We micro-dissected an ~1mm skin region surrounding the wound-site and then FACS-purified and transcriptionally profiled the basal epidermal keratinocytes by RNA-seq (Figures S4A and S4B). By comparing wounded and unwounded keratinocyte profiles, we could distinguish transcriptional differences specifically associated with age and wound-healing from those associated merely with age.

Differential transcription analysis of young and aged keratinocytes at the wound edge revealed 393 genes that were differentially regulated in replicates with a q-value <0.05 (Table S2). Hierarchical clustering analysis showed that unwounded young and aged epidermal samples clustered together, consistent with their similar behaviors during normal homeostasis. Interestingly, however, aged keratinocytes at the wound edge grouped more closely with young and aged homeostatic (unwounded) states than did young keratinocytes at the wound edge (Figure 4A). Notably, this was even true when gene expression across the entire transcriptome was compared (Figure S4C).

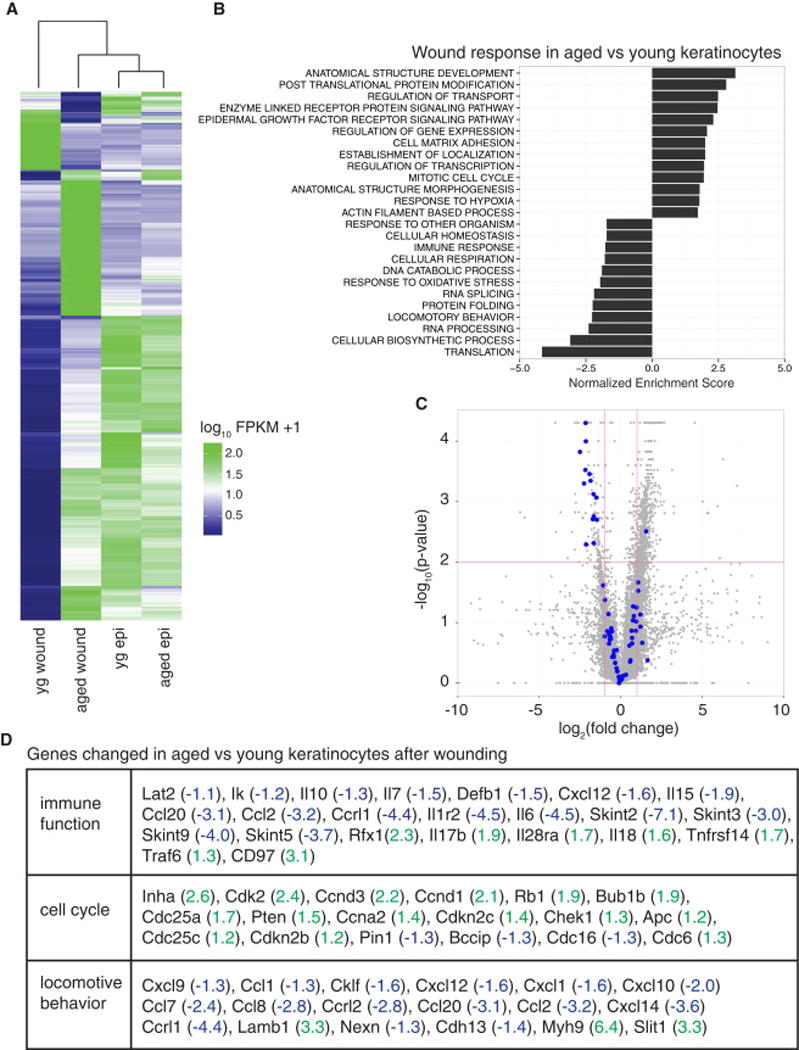

Figure 4. Transcriptional profiling of wound response. A).

Heat map of differentially regulated transcripts between aged and young epidermal keratinocytes isolated from unwounded skin or the wound edge of skin and subjected directly to RNA-seq analyses. Yg wound, young keratinocytes isolated from the wound edge; aged wound, aged keratinocytes isolated from the wound edge; yg epi, young keratinocytes under homeostatic conditions; aged epi, aged keratinocytes under homeostatic conditions. Blue color denotes low FPKM expression, green high FPKM expression. B) Negatively and positively enriched GO terms in genes that were differentially regulated between aged wound and young wound samples. C) Volcano plot of differentially regulated genes between young wound and aged wound samples. Vertical rose-colored lines denote fold changes greater ± 2-fold. Horizontal rose line denotes p-value > 0.05. Blue dots indicate genes with a GO annotation relating to immune function (note marked failure of many of these genes to be up-regulated in aged wounds). D) Table of selected genes for indicated GO term from RNA-seq analysis (blue, down-regulated by log2 of value; green, up-regulated by log2 of value). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S4 and Tables S2–S6.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) found 114 core GO terms (p-value<0.05) enriched in our age-regulated wound gene set relative to young wounded keratinocytes (Figure 4B and Table S3). Leading edge analysis identified 8 enriched core processes (cell cycle, cell death, immune system, metabolism, migration, signaling, transcription and transport) each with multiple GO terms enriched within them (Figure S4D).

When we compared young basal keratinocytes under homeostatic conditions (young epi) to young wound-edge keratinocytes (young wound) to define a molecular signature for the wound response. In response to injury, 1679 genes were down-regulated by young keratinocytes, while 500 transcripts were elevated (Table S4). Not surprisingly, these transcripts differentially changed by ±2-fold were enriched for GO terms including transcription, cell cycle regulation, migration, metabolism and epidermal development (Table S5).

In contrast, keratinocytes at the wound edge of older mice were much more similar to homeostatic conditions, revealing a much less dynamic transcriptional response to injury. Only 564 genes changed ±2-fold in wound-activated aged keratinocytes compared to their unwounded aged counterparts (Table S6). Of these changes, ~90% of the 236 up-regulated genes in aged, wound-induced epidermis were also up-regulated in their younger counterparts; and a 34% overlap was seen among genes that were down-regulated in response to wounding in young and old animals (Figure S4E). Taken together, these data suggest that not only are aged keratinocytes more refractory transcriptionally in their response to injury, but there are genes mis-regulated in aged keratinocytes that are not part of the normal wound response at this time-point.

Wounding Reveals Age-Related Defects in Cross-Talk Between Epidermal Cells and DETCs

Further inspection revealed that many genes associated with immune function failed to be regulated by aged keratinocytes at the wound edge (Figures 4C and 4D). This was particularly evident in the volcano plot, where immune function genes (blue dots in 4C) were often markedly under-expressed in aged versus young wounded skin keratinocytes. This was interesting, as the epidermis is known to undergo various forms of cross-talk with different immune system components, which can impact their proliferative capacity (Castellana et al., 2014; Depianto et al., 2010; Glitzner et al., 2014).

We used flow cytometry to analyze the overall immune response prior to and following wounding. We observed a clear influx of neutrophils, monocytes and macrophages into the wound bed d3 after wounding. However, no differences were noted which could specifically explain the age-related, wound-related downshift in epidermal expression of immune signaling genes that we unearthed at this same time-point (Figure 5A). Similarly, we did not observe age-specific differences in the wound response of either αβ T-cells or dermal γδ T-cells at this time (Figure 5B). In contrast, a striking wound site-specific reduction in epidermal γδ T-cells emerged that was selective to aged skin (Figure 5B). We confirmed their identity of these epidermal γδ T-cells as Vγ5Vδ1-DETCs based on their localization, dendritic morphology and high surface expression of Vγ5Vδ1 (Figure S5A).

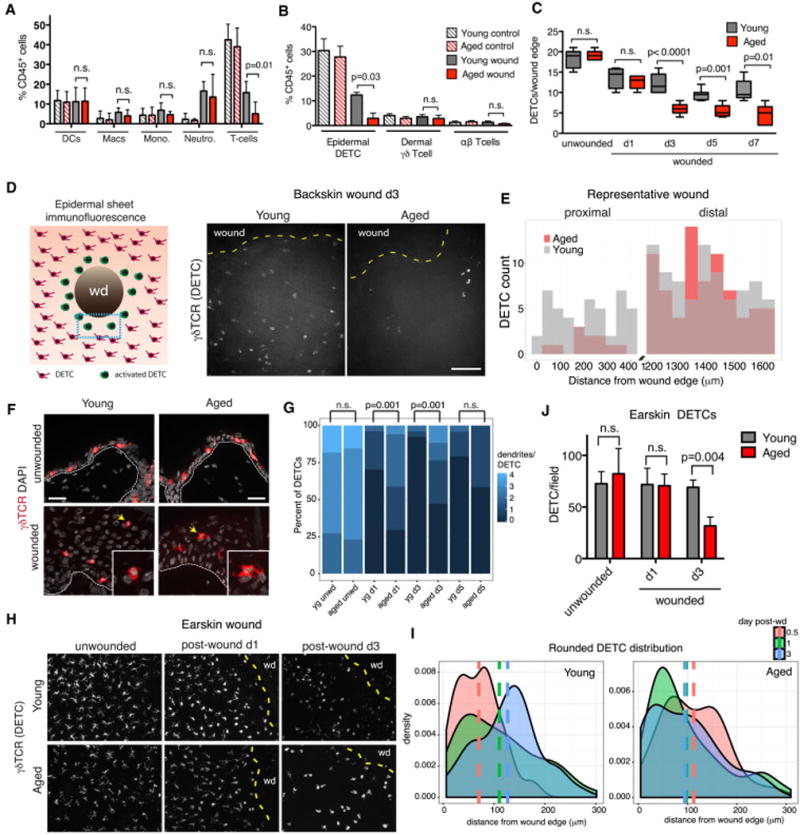

Figure 5. Immune cells and wound healing in aged skin. A).

Skins from young and aged mice either unwounded or within 1mm of a wound-edge were subjected to flow cytometry analysis using the scheme in Figure S4A. Percentages of specific immune subclasses relative to total immune cells (CD45+) are shown. DC, dendritic cells (MHCII+CD11c+); Macs, macrophages (CD64+CD11b+); Mono, monocytes (Ly6chiLy6gneg); Neutro, neutrophils (Ly6cnegLy6ghi); T-cells (γδTCR+TCRβ). N=6. B) Quantification of skin resident T-cells by flow cytometry. Data are presented as percentages of specific T-cell subclasses relative to total immune cells (CD45+). N=6. C) Quantifications of DETCs numbers from 0–700μm of the wound edge at indicated times after wounding. N=5. D) Schematic of epidermal sheet preparation (whole mount) of wound from birds-eye-view and maximum projections of z-series images of epidermal sheets are from skin adjacent to wound edge (yellow dotted lines), with immunostaining for γδ TCR to detect DETCs. Shown are images from d3 after wounding. E) At right are quantifications of DETC distribution, plotted in histograms as the distance proximal (0–400 μm) and distal (1200–1600 μm) from the wound edge. N=10. F) Sagittal imunofluorescence images of skin (wounded and unwounded), immunostained for DETCs. Dashed lines denote epidermal/dermal boundaries. Scale bars=25 μm. Insets show DETCs highlighted with arrows. G) Quantification of the numbers of dendrites per DETC. N=5. Students t-test was used to measure statistical significance. H) Whole mount DETC immunofluorescence of ear-skin. Shown are images prior to and at d1 and d3 after wounding. Scale bars = 100 μm. N=3. Yellow dotted lines denote wound edge (wd). I) Density plots of the distribution of rounded (no dendrites) of DETCs in ear-skin whole mount preparations at times post-wounding indicated. Vertical lines represent mean distance of rounded DETCs from wound edge (0 μm). J) Quantifications of DETCs at the wound site at times after injury. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S5.

In the homeostatic (unwounded) state, DETCs were present in equivalent numbers in young and aged skin (Figure 5C). Following wounding, DETC numbers declined significantly more in aged than in young skin; differences peaked by d3 but by d7, when re-epithelialization neared completion, DETC numbers were still low in the repaired skins of aged mice. This d3–d7 time period corresponded to the time when the greatest differences were seen in aged versus young skin wound healing.

To characterize this age- and wound-related difference, we immunostained DETCs in sagittal sections and in whole mount epidermal sheets of backskins. Corroborating the flow cytometry data, DETC numbers were equivalent in young and aged skin, but declined markedly in the aged skin after wounding and remained low even at d7 (Figures 5D; S5B–E). By whole-mount microscopy, we could analyze the temporal behavior of DETCs relative to the wound edge. Quantifications revealed a >5X reduction in DETCs seen in a ~400 μm radius of skin surrounding the d3 wound, while DETC levels remained similar at sites distal to the wound (Figure 5E).

In wounded skin, DETCs are known to change from a dendritic to a rounded morphology as they enter an activated state around a wound edge (Chodaczek et al., 2012; Jameson et al., 2002). We therefore examined DETC morphology changes in wounded backskin of young and aged mice. Interestingly, the DETCs at the wound site were less rounded and displayed more dendrites than their younger counterparts at day 1 and day 3 after wounding (Figures 5F and 5G).

We also examined epidermal sheet preparations of earskin, where the characteristic dendritic morphology of DETCs is better visualized and quantified (Figures 5H–5J). By d0.5 post-wounding, the DETCs of young skin displayed a narrow distribution of rounded cells within ~100 μm of the wound edge. This band was maintained at d1 post-wounding, and extended from the wound edge by d3. In contrast, rather than the tight transition from dendritic to rounded morphology in young skin, rounded DETCs were scattered from the start throughout a broader range from the wound site of aged skin. By d3, many were lost from the wound edge. Irrespective of body site, DETCs in the vicinity of the wound sites of aged mice showed perturbations in morphology and numbers, often sustaining more dendrites than their younger counterparts (Figures 5G and S5E). Together, these studies exposed age-related, wound-specific defects in DETC morphology and maintenance.

Epidermally-Expressed Skints Function in Wound Repair and in Signaling to DETCs

Since young wound-activated DETCs are known to signal to keratinocytes to produce epidermal growth promoting factors (Jameson et al., 2002), it seemed plausible that intrinsic age-related defects in DETCs might account for delays in wound re-epithelialization. That said, the marked intrinsic differences in aged epidermal keratinocytes to mount a transcriptional cascade of immune modulatory factors following injury raised the possibility that wound-specific, epidermally-derived signals to DETCs might be altered in aged animals.

Returning to our RNA-seq data, we were struck by the preponderance of Skint genes, which were up-regulated in young wounded skin epidermis relative to its aged counterpart. Notably, during normal homeostasis, Skint2, Skint3, Skint5, Skint7 and Skint9 were low in basal epidermal keratinocytes regardless of age, but at the wound edge, their expression was elevated in young but not aged keratinocytes (Figure 6A). RT-qPCR on independent samples of wound-induced epidermis validated the age-related differential expression of these Skint transcripts (Figure 6B).

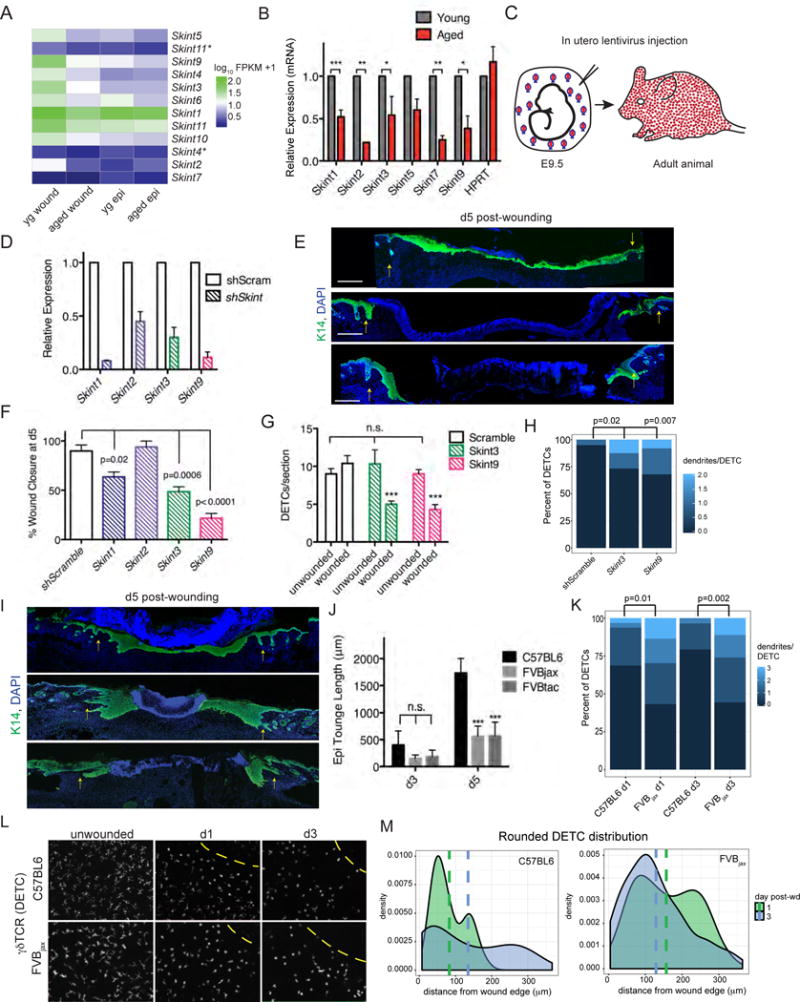

Figure 6. Failure of keratinocytes to up-regulate Skints results in impaired wound healing in young mice. A).

Heatmap of Skint gene family expression from RNA-seq data. Asterisks denotes splice variant. Yg wound=young keratinocytes isolated from the wound edge, aged wound= aged keratinocytes isolated from the wound edge, young epi=young keratinocytes under homeostatic conditions, aged epi=aged keratinocytes under homeostatic conditions. B) qRT-PCR of Skint mRNAs from keratinocytes isolated from wound edges. C) Illustration in utero lentiviral infections into amniotic sacs of E9.5 embryos and selective transduction of mouse skin epidermis. D) Knockdown efficiency of Skint shRNAs as measured by qRT-PCR of adult epidermis prior to wounding. E) Immunofluorescence images of d3 backskins of wounded young mice whose epidermises were transduced in utero for the Skint shRNAs indicated. Scr, scrambled. Tissue sections are immunolabeled for K14 (green) and DAPI (blue). S, scab; arrows denote wound-edge. Scale bar= 500 μm. F) Wound closure at d5 of young mice transduced for the indicated shRNAs. N=4. G) Quantification of DETC number and number of dendrites per DETC (H) in sections of unwounded and wounded skins transduced as indicated. N=4. I) Immunofluorescence images of back-skins of re-epithelialization process following 5d or 3d after wounding of young mice of the strains indicated. Note that FVBJax lacks Skints 3-4-9; FVBTac lacks Vγ5Vδ1 DETCs. Tissue sections are immunostained for K14 (green) and DAPI (blue). S, scab; arrows denote wound-edge. Scale bar = 100 μm. N=2. J) Quantification of wound closure by re-epithelialization. K) Quantificaton of dendrities per DETC from tissue sections of wounds in C57BL6 and FVBJax at time-points indicated. L) Whole mount immunofluorescence and quantifications of DETCs in ear-skin of young FVBJax versus C57BI/6 mice. Scale bars= 100 μm. N=2. M) Density plots of the distribution of rounded (no dendrites) of DETCs in ear-skin whole mount preparations at times post-wounding indicated. Vertical lines represent mean distance of rounded DETCs from wound edge (0 μm). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S6.

The functions of Skints in adult tissue homeostasis and wound-repair are unknown. However, the established role of Skint1 in the selective development of Vγ5Vδ1-TCR expressing DETCs in fetal thymus (Boyden et al., 2008) led us to posit that diminished epidermal Skint activation might account at least in part for the diminished ability of aged, wounded skin to sustain and/or activate DETCs. To test the functional relevance of Skints expressed by young epidermal keratinocytes in response to wounding, we engineered lentiviruses harboring shRNAs that target Skints 1, 2, 3 and 9 and a Scrambled control (Figures S6A). To identify transduced regions, we added a transgene encoding fluorescently tagged histone H2B-mRFP to each lentiviral vector (Figure S6B). Lentiviruses were injected in utero into the amniotic sacs of living E9.5 embryos, a method that specifically and efficiently infects the single layer of unspecified surface epithelial cells (Beronja et al., 2010). Within a few days, lentiviral DNA integrates and is thereafter stably propagated throughout the epidermis (Figure 6C).

Mice transduced in utero with Skint shRNAs lived to adulthood. qPCR confirmed the efficient knock-down of Skints in vivo (Figures 6D and S6D). Therefore at P55, we administered punch wounds and monitored the activation of Skints and the re-epithelialization process. Notably, wound-induced re-epithelialization was significantly impaired in these young mice whose epidermis was transduced with Skint3 and Skint9 but not Scrambled shRNAs (Figures 6E and 6F). At d5 post-wounding, the epithelial tongues of control wounds were largely sealed (90±6%) while wounds from Skint9 and Skint3 knock-down skins showed as little as 22±5% and 49±5% closure, respectively. For Skint3 and Skint9, two distinct shRNAs were transduced independently and knockdowns gave analogous results (Figure S6D). These data reinforced the efficacy of the wound-impaired phenotypes in young mice lacking SKINTs.

We also assessed the numbers and morphologies of DETCs in our individual keratinocyte-specific Skint knockdown mice. Importantly, Skint3 and Skint9 knockdown did not appreciably affect steady state DETC numbers in unwounded skin; however, Skint shRNA-transduced young mice showed a modest decrease in DETCs adjacent to the wound bed relative to those in Scrambled control mice (Figure 6G). More noticeable was that DETCs displayed more dendrites than their control counterparts (Figure 6H). These alterations in dendrite morphology were consistent with, albeit not as marked, as we saw in aged wounded skin.

To further document the role of Skints in wound repair, we took advantage of the natural deletion of the Skint3, Skint4 and Skint9 gene locus in FVBjax mice (Boyden et al., 2008) (Figure S6F). Interestingly, young FVBjax mice displayed re-epithelialization delays when compared to several strains of mice that maintain the Skint3, Skint4 and Skint9 gene locus, including closely related NON/ShiLtJ, as well as C57BL6 and CD-1 (Figures 6I, 6J and S6G). The kinetics of the re-epithelialization delay in young Skint3-4-9 null mice paralleled those in aged C57BL6.

Similar to aged and control mice, Vγ5Vδ1-DETCs in young FVBjax animals were still in equivalent number during normal homeostasis (Barbee et al., 2011) (Figure S6H–I). This was also the case for wounded skin. However, even though FVBjax DETCs had somewhat fewer dendrites in the unwounded state, DETCs remaining at d1 and d3 time-points after wounding displayed more dendrites than normal (Figures 6K and S6J–S6K). Additionally, rounded DETCs were atypically intermingled with dendritic ones at the FVBjax wound edge (Figures 6L–6M). Overall, the perturbations in DETC morphologies at the wound edge of young FVBjax mice were similar to those of aged C57BL6 mice.

Finally, we also examined wound-repair in FVBTac mice, which lack Vγ5Vδ1-DETCs but which differ from the TCR δ-null mice previously studied in a wound context (Jameson et al., 2002) in that they have other γδ T-cells in their epidermis (Boyden et al., 2008) (Figure S6L). Indeed, FVBTac mice too displayed a pronounced wound-repair defect (Figure 6I–6J). This result underscored a specific role for Vγ5Vδ1-DETCs in wound-repair, extending prior data reporting defective wound healing in mice lacking all γδ T-cells (Jameson et al., 2002).

Skints Act Downstream of STAT3 Signaling, Which is Reduced at the Aged Wound Front

To gain mechanistic insight into why Skint genes are up-regulated in epidermal keratinocytes of young wounded skin and yet failed to be induced in keratinocytes at the wound edge of aged mice, we analyzed the promoter sequences (4000 bp up-stream of the start codon) for conserved motifs that maybe regulating their expression. MEME software analysis of up-stream sequences identified 3 highly conserved motifs, distributed across Skint gene promoters (Figures S7A and S7B). Within the conserved motifs were 39 transcription factor consensus-binding sites, which when cross-referenced with our RNA-seq data, yielded 9 putative transcription factors that were expressed in basal epidermal keratinocytes at the wound edge (Figure S7C).

Among these 9 factors was the transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) (Figure S7D). STAT3 took on particular relevance given a prior report that Stat3−/− mice have delays in wound-healing, with reduced keratinocyte migration in in vitro assays (Sano et al., 1999). Intriguingly, interleukin 6 (IL-6), a canonical up-stream ligand of STAT3 signaling, showed a 4.5X reduction in aged vs young keratinocytes after wounding (Figure 4D). However, after treatment of either young or aged keratinocytes with recombinant IL-6 in vitro, phosphorylated (activated) STAT3 and nuclear translocation occurred within 30 minutes of treatment (Figure S7E). Importantly, as judged by RT-qPCR, a number of Skint transcripts were appreciably elevated by IL-6 (Figure 7A).

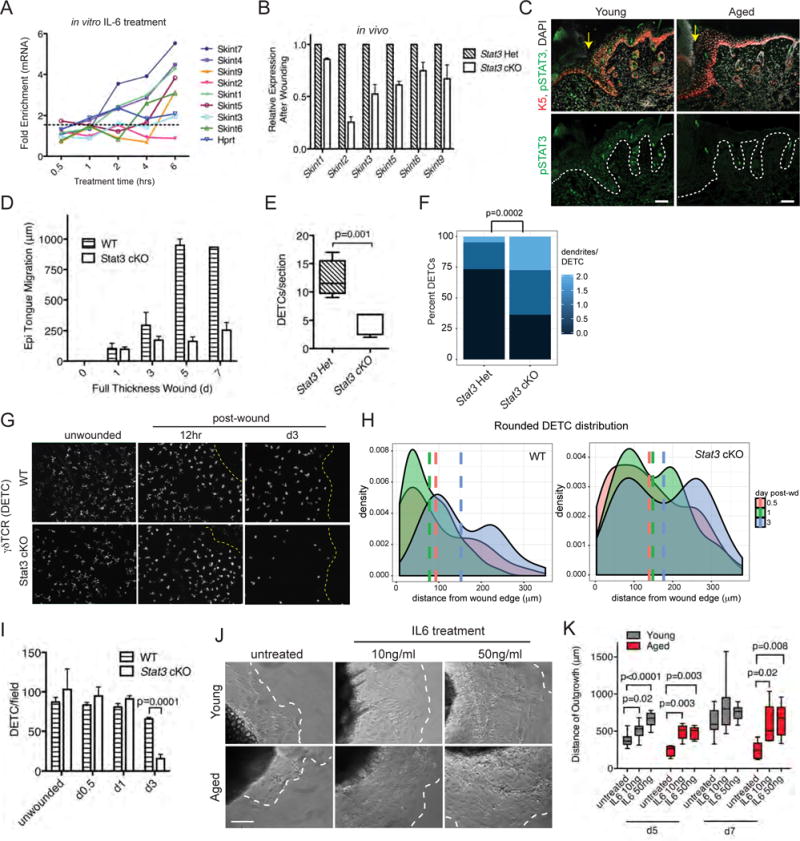

Figure 7. STAT3 signaling regulates Skint expression. A).

Skint mRNA levels after IL-6 treatment of primary WT keratinocytes in vitro. B) Relative in vivo expression of Skint genes in keratinocytes isolated from d3 wound edges. C) Immunofluorescence images of sagittal wounded skin sections from young and aged WT mice. Labeling is for Abs against pSTAT3 (green), K5 (red), and DAPI (grey). Dashed line denotes epidermal/dermal boundaries, yellow arrows denote wound edges, and “S” denotes scab. Scale bars = 100 μm. D) Quantification of the epithelial tongue length at backskin wounds at times post-wound indicated. N=4. E) Quantifications of DETC numbers and (F) morphologies from d3 wound edges. N=4. G) Whole mount immunofluorescence of ear skins imaged at times indicated after wounding. Yellow dotted line denotes wound edge. Scale bar = 100 μm. N=2. H) Density plots of the distribution of rounded (no dendrites) DETCs in ear-skin whole mount preparations at times post-wounding indicated. Vertical lines represent mean distance of rounded DETCs from wound edge (0 μm). I) Quantifications of DETC numbers in ear skin whole mounts after wounding at time-points indicated. J) DIC images (from d5 time-point) of explant cultures from young and aged tissue biopsies treated with IL-6 at concentrations indicated. Dashed lines denote the borders of keratinocyte outgrowth; E, explant. Scale bars=10μm. N=8. K) Quantifications are of the distance of outgrowth of keratinocytes in explants during a 7 day time-course. N=8. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S7.

If the enhanced induction of Skints following pSTAT3-signaling is physiologically relevant, then the ability of keratinocytes to induce Skint expression after wounding should be reduced in K14-Cre;Stat3fl/fl mice. Indeed, Stat3-null epidermis from young mice showed significantly reduced activation of Skints following wounding (Figure 7B).

If the link between STAT3 and Skint gene expression is relevant to the age-related decline in the ability to activate DETCs, there should be a corresponding age-related decline in STAT3 signaling upon wounding. Immunostaining for activated, phospho-STAT3-Tyr705 (pSTAT3) in d3 post-wound tissue sections revealed many fewer and much more weakly labeled keratinocytes in aged skin relative to their young counterparts (Figure 7C). In contrast, only rare pSTAT3-positive cells were seen in unwounded skin tissue regardless of age (Figure S7F). We corroborated a wound-closure delay in K14-Cre;Stat3fl/fl mice, and further showed that analogous to aged mice, it is the re-epithelialization feature of wound-repair that is defective and with similar slowed kinetics of healing (Figures 7D and S7G).

Given our observations that first, Skints are reduced in Stat3 cKO mice and second, that DETC behavior is perturbed in mice deficient in epidermal Skints, we focused on the DETCs in Stat3 cKO animals. In the unwounded state, DETC numbers were unaffected by Stat3 loss. However, following wounding, DETC numbers declined dramatically in the Stat3 cKO skin (Figures 7E). Moreover, those DETCs that remained at the wound site displayed more dendrites than in Stat3 Het animals (Figure 7F). Whole mount immunofluorescence microscopy of wounded Stat3 cKO ear-skin revealed that at early times, wound edges lacked the tight distribution of rounded DETCs seen in the control mice (Figures 7G and 7H). By 3d, there was a marked paucity of DETCs (Figure 7I). Taken together, the loss of STAT3 recapitulated the defects in DETCs and wound healing seen in aged mice and in mice deficient for Skint3/9.

IL6 Treatment Improves Wound Repair in Aged Skin

Our collective findings pointed to the existence and functional importance of a key IL6-STAT3-Skint connection in wound-repair. If as our results suggest, a decline in the ability to activate this pathway is at the crux of the age-related wound-repair defects, it should be possible to enhance keratinocyte migration in skin explants from aged mice through administration of IL-6. To test this hypothesis, we treated explants from young and aged skin with 10 and 50ng/ml IL-6 in vitro and monitored keratinocyte outgrowth at 5d and 7d time-points. Exposure to IL-6 markedly improved keratinocyte outgrowth in aged and young explants (Figures 7J and 7K). However, the effects were more pronounced in aged explants, which showed a 2.2-fold increase in IL-6 mediated outgrowth relative to a 1.4-fold increase in young explants.

DISCUSSION

Wound healing is a complex biological process. It requires the interaction of diverse cell types and distinct signaling pathways, which must be orchestrated in a spatiotemporal manner to achieve proper re-epithelialization. Beginning with DuNouy’s observations of delayed wound healing in older soldiers in World War I, to more rigorous experimental evidence in rats and other animals, studies have shown that wound healing is delayed in aged tissues (Goodson and Hunt, 1979; Raja et al., 2007; Reed et al., 2003). Alterations have been described in almost every phase of the healing process, with delays ranging from 20 to 60% (Ashcroft et al., 2002; Gosain and Dipietro, 2004; Sgonc and Gruber, 2013). The molecular underpinnings of why such delays are observed, how age-related physiological changes negatively affect wound healing, and how chronic wounds develop in elderly individuals is poorly understood.

In our study, both intrinsic and extrinsic factors contributed to impaired healing in aged skin. We detected reduced proliferation and re-epithelialization at the wound sites of aged versus young animals, and when placed into equivalent environments in vitro, aged keratinocytes still displayed reductions in colony forming efficiency, explant outgrowth, and migration when compared with their youthful counterparts. Moreover, aged basal epidermal keratinocytes isolated from the wound edge appeared to be more recalcitrant to activation, as judged by their markedly reduced transcriptional activity of genes involved in important processes of wound-repair.

While these features pointed to the age-related intrinsic alterations in epidermal keratinocytes, marked changes in the extrinsic environment of the wound also surfaced in aged skin, as exemplified by the significant decline in epidermally expressed immune response genes. These age- and wound-specific transcriptional differences in the epidermal keratinocytes were accompanied by age-related perturbations in DETC behavior during wound-repair.

Recent lines of evidence have implicated the adaptive immune system in a number of facets of wound-repair in multiple tissue types (Burzyn et al., 2013; Carvalho et al., 2014; Jameson and Havran, 2007; McGee et al., 2013; Rani et al., 2015). Mice that lack all γδ T-cells display an ~2d delay in wound healing (Jameson et al., 2002). We observed similar wound-induced delays in re-epithelialization in FVBTac mice, which specifically lack Vγ5Vδ1-DETCs but display other γδ-T-cells in the epidermis that are normally confined to the dermis (Barbee et al., 2011; Lewis et al., 2006). Our finding demonstrates that Vγ5Vδ1-DETC loss alone is sufficient to instigate wound-related problems in re-epithelialization, lending strong support for prior studies showing that upon wounding, DETCs produce signaling factors which act in paracrine to promote epidermal proliferation and healing (Jameson and Havran, 2007).

In light of these data, it was particularly intriguing to unearth aberrations in DETC behavior in aging mice, because they are wild type for γδ T-cells. Moreover, age-related DETC perturbations only surfaced following wounding, where DETCs which normally participate in re-epithelialization, were not maintained at the wound edge, resulting in delays in restoration of the skin barrier. This particular defect took on all the more interest given a previous report that a soluble form of Vγ5Vδ1-TCR binds to keratinocytes adjacent to a wound, but not to keratinocytes in unwounded skin (Komori et al., 2012). Such findings provide strong support for the notion that epidermal keratinocytes at the wound edge undergo a specific change that impacts their recognition by DETCs (Havran and Jameson, 2010).

We traced the elusive epidermally expressed ligand(s) that can affect wound-induced DETC behavior to SKINTS, whose functions in adult tissues are unknown. We first discovered that epidermally expressed Skints are selectively up-regulated in the basal epidermal keratinocytes at the wound edge of young but not aged mice. We next determined that Skint expression is directly influenced by STAT3 signaling, which like its up-stream activator IL-6 and its downstream Skint targets, is also diminished at the wound edge of aged mice. Finally, we unearthed wound-induced re-epithelialization delays in mice that are a) knocked down for epidermal Skint3 and Skint9, b) deleted for Skints 3, 4 and 9, or c) conditionally targeted for epidermal Stat3. Importantly, like aged mice, these various mutant mice were still replete with Vγ5Vδ1-DETCs but exhibited perturbations in DETC behavior.

Our findings provide compelling evidence that epidermal keratinocytes are powerful not only in responding to, but also in communicating with, their resident DETCs to achieve restoration of the skin barrier following injury. Moreover, they provide insights into the physiological significance of SKINTs, which previously until now has been limited to SKINT1. Our findings here expose a role for other SKINT family members in mediating keratinocyte-DETC crosstalk during wound-repair. Since individual Skint knockdowns showed a wound-delay phenotype and SKINTs are known to homo-/hetero-dimerize (Barbee et al., 2011), it will be interesting in the future to probe deeper into their interactions and functions at the wound-edge.

Finally, our data also underscore a mechanistic role for IL-6 mediated pSTAT3 signaling in driving Skint transcription during a youthful wound-response, and reveal an overall reduction in this circuitry in aged mice. Although pSTAT3’s functions in wound-induced immune responses no doubt extend beyond the pathway that we discovered here, the effects of epidermal Stat3 loss of function on the ability to retain DETCs at a wound site were strikingly similar to that which we observed in aged mice.

When coupled with the wound-induced re-epithelialization impairment for both aged and epidermal Stat3-null skin, our data demonstrate that this circuitry is critical in skin barrier restoration. Indeed our findings show that IL-6 can both enhance pSTAT3 and Skint expression in epidermal keratinocytes and also abate the wound healing impairment in aged mice. Given that elevated IL-6 has been associated with inflammation in aged tissue and observed in senescent cells (Franceschi and Campisi, 2014; Kojima et al., 2013), whether these chronic processes negatively impact the acute wound healing response in aged wounded skin was particularly intriguing, and suggests avenues for future therapeutics in accelerating healing in the elderly population.

STAR METHODS

Detailed methods are provided in the online version of this paper and include the following:

Contact for Reagent and Resource Sharing

Further information and requests for reagents may be directed to, and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact: Elaine Fuchs (fuchslb@rockefeller.edu)

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Mice and Wounding Experiments

Aged (22–24) months female C57BL6 mice were obtained from the National Institutes of Aging (NIA). We specified to receive mice with “good hair coats” to avoid animals with clear signs dermatitis, fighting, scratching and inflammation. Animals with visible neoplasia were discarded. Young (2–4 months of aged) C57BL6 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. Stat3 cKO mice were obtained by crossing Stat3floxed animals from Jackson Laboratories (Stock No:016923) to K14-Cre/Rosa26-YFP (Fuchs Lab) animals. FVBjax (FVB/NJ Stock No:001800) and NON/ShiLtJ (Stock No: 002423) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories and FVBtac (FVB/NTac) from Taconic Laboratories. All mice were maintained in an AAALAC-approved facility at The Rockefeller University. Procedures were performed using IACUC-approved protocols that adhere to NIH standards.

Method Details

Wounding Study

Punch biopsies were performed on anaesthetized mice in the telogen phase of the hair cycle. For backskin wounds, dorsal hairs were cut with clippers and skin was swabbed with EtOH prior to wounding. 6mm biopsy punches (Miltex) were used to make full-thickness wounds. For ear punch biopsies, animals were anesthetized and a 2mm biopsy was used to punch a through-and-through wound (hole) in the center of each ear. After wounding, tissue was collected at 0.5d, 1d and 3d after wounding for immunostaining (details below). Depilation was performed as described (Keyes et al., 2013). For EdU pulse experiments mice were injected intraperitoneally (50 μg/g) (Sigma-Aldrich) at specified intervals before collection.

Histology and Immunofluorescence

Backskin tissue was embedded in OCT compound (Tissue Tek) and frozen on dry ice, and cryo-sectioned (10–12 μm section thickness). Sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, rinsed with PBS, permeabilized 10 minutes with 0.1% Triton X100 (Sigma) in PBS, and then blocked for 1 hr in blocking buffer (2.5% normal donkey serum, 2.5% normal goat serum, 1% BSA, 1% Gelatin, 0.3% Triton X-100). Primary antibodies (and their dilutions) used were as follows: K5 (guinea pig, 1:500, Fuchs lab); K14 (rabbit, 1:1000, Fuchs lab), K17 (rabbit, 1:1000, Fuchs lab), K10 (rabbit, 1:1000, Covance), K6 (guinea pig, 1:2000, Fuchs lab), Cleaved Caspase-3 (Rabbit, R&D Systems, 1:1000), γδTCR (Armenian Hamster, BioLegend, 1:100), pSTAT3 (Rabbit, Cell Signaling, 1:100), CD104 (Rat, BioLegend, 1:500), APC TCR Vγ3 (Syrian Hamster, Biolegend, 1:200), AlexaFluor-488 CD3 (rat, Biolegend, 1:200). Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer and incubated at 4°C overnight. After washing with PBS, secondary antibodies, conjugated with Alexa488, Alexa546, or Alexa647 (Jackson ImmunoResearch), were added for 1–3 hours at room temperature (RT). Slides were washed with PBS, counterstained with 4′6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and mounted in Prolong Gold (Invitrogen). EdU staining was performed using Click-iT EdU Alexa-Fluor Imaging Kit (Life Technologies) per manufacturer’s instructions. Wound images were acquired with an AxioOberver.Z1 epifluorescence microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER camera and an ApoTome.2 (Carl Zeiss) slider. Tiled and stitched images of wounds were collected using a 20X objective, controlled by Zen software (Carl Zeiss).

For whole mount epidermal sheet preparations of wounded skin, skin was excised around the wound, fat was scraped away with a scalpel and treated with 3.8% ammonium thiocyanate (Sigma) for 30 minutes at 37°C. The epidermis was separated with forceps from dermal tissue manually. The epidermis was then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and stained as above with γδTCR (BioLegend, Armenian Hamster, 1:100) antibody. Tissue was mounted onto slides and counterstained with 4′6′-diamidino-2′-phenylindole (DAPI) and mounted in Prolong Gold (Invitrogen). Imaging was performed on a Zeiss Axioplan2 using a Plan-Apochromat 20X/0.8 air objective. Images presented are maximum projections of a z-series of images. For analysis of DETC dendrites, maximum projection images were used to count dendrites on DETCs in wounded and unwounded control skin. For whole-mount ear-epidermal preparations, ears were split laterally, then incubated in 3.8% ammonium thiocyanate for 30 minutes at 37°C before ear epidermis were separated from dermis. Epidermal sheets were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 hour at room temperature, before proceed for γδTCR immunostaining. Imaging was performed on a Zeiss Axioplan2 using a Plan-Apochromat 20X/0.8 air objective. Images presented are maximum projections of a z-series of images.

For semi-thin sectioning and staining, samples from backskins were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde, 4% paraformaldehyde and 2 mM CaCl2 in 0.05 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2, at room temperature for > 1 hr. Samples were postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, and processed for Epon embedding. Semi-thin sections (800 nm) were cut and stained with toluidine and examined under bright-field Zeiss Axioplan2 microscope. Figures were prepared using ImageJ, Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator CS5.

Cell Culture

Young and aged basal cell keratinocytes were FACS isolated from animals and plated on mitomycin-C treated J2 fibroblast feeder cells to establish primary cell lines. Independent clones were cultured and passaged in E-media supplemented with 15% serum and a final concentration of 0.3 mM Ca2+ for 3 passages and then moved to feeder-free cell culture (Rheinwald and Green, 1975). For colony forming efficiency assays, viability of epithelial keratinocytes was determined using trypan blue (Sigma) staining on a hemocytometer after FACS-isolation. Equal numbers of live cells were plated, in triplicate, onto mitomycin-C treated dermal fibroblasts in E-media supplemented with 15% serum and 0.3 mM Ca2+. After 14 days in culture, cells were fixed and stained with 1% Rhodamine B (Sigma). Colony diameter was measured from scanned images of plates using Image J and colony numbers were counted. For IL-6 treatment experiments, keratinocytes were serum starved for 24 hours then treated with recombinant mIL-6 (R&D Systems) at 10ng/ml for indicated time-points. Cells were collected directly in Trizol (Invitrogen) and RNA was extracted for qRT-PCR (see below). Cell adhesion and cell spreading assays were performed as described previously (Humphries, 2009). Wells were coated using 10 μg/ml human plasma fibronectin (Milipore), 40 μg/ml rat tail collagen-I (Corning), 0.1% (w/v) poly-L-lysine (Sigma), and 1 μg/ml BSA (Sigma) for 1 hour at room temperature, washed with PBS 3-times and used in cell adhesion assays.

For scratch migration assays, keratinocytes were plated on 6-well tissue culture dishes and allowed to reached confluency. Scratches were then created by manual scraping of the cell monolayer with a pipette tip. The dishes were then washed with PBS, replenished with E media supplemented with 1mM HEPES, and photographed for periods of 25–36 hr in 5% CO2 on a PerkinElmer Volocity spinning disk system equipped with a heated enclosure and gas mixer (Solent) and 20X/0.75 CFI Plan-Apo objective. Individual keratinocytes migration was manually tracked using ImageJ software. Transwell migration assays were performed in 6-well plates (Corning). The bottom of each well was coated with 10 μg/ml fibronectin and fibroblast-conditioned E-media containing 0.3 mM Ca2+ was added. Young and aged keratinocytes were serum starved for 24 hours, and a total of 20,000 cells/well were plated in serum-free medium containing 0.3 mM Ca2+. At time-points indicated cells were washed off the top membrane and then cells were fixed to the bottom membrane. Cells were stained using hemotoxylin and eosin and counted under the microscope.

For explants assays, backskin tissue was harvested and hair was removed with Nair and washed with PBS. Subcutaneous fat was gently removed with a scalpel. Explants were cut out using a 1.5mm dermal biopsy punch (Miltex), then placed on fibronectin coated 24 well tissue culture dishes and secured to bottom of dish with 1–2 μl Matrigel (Corning), and submerged in E-media containing 0.3 mM Ca2+. Outgrowths from explants were imaged at indicated time-points and analyzed with ImageJ. For explants treated IL-6, 2mm biopsy punches were used to cut out explants and treated with 10ng/ml and 50 ng/ml of IL-6 in E-media containing 0.3 mM Ca2+. Images were taken at indicated time-points and outgrowths measured using ImageJ.

RNA-seq and Analysis

FACS isolated keratinocytes were sorted directly into TRI Reagent (Sigma). Three animals were pooled per condition and all experiments were performed in duplicate. RNA was purified using Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep kit (Zymo Research) per manufacturer’s instructions. Quality of the RNA for sequencing was determined using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, all samples used had RNA integrity numbers (RIN) > 8. Library preparation using Illumina TrueSeq mRNA sample preparation kit was performed at the Weill Cornell Medical College Genomic Core facility, and RNAs were sequenced on Illumina HiSeq 2000 machines. Alignment of reads was done using Tophat with the mm9 build of the mouse genome. Transcript assembly and differential expression was determined using Cufflinks with Refseq mRNAs to guide assembly (Trapnell et al., 2010). Analysis of RNA-seq data was done using the cummeRbund package in R (Trapnell et al., 2012). Differentially regulated transcripts were used in Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) to find enriched functional GO annotations (Subramanian et al., 2005). MEME software suite (including TomTom) was used to identify enriched motifs in Skint promoters, the JASPAR vertebrate database was as a source for consensus transcription binding site sequences (Bailey et al., 2009).

Lentvirus Production and Injections

Production and concentration of lentivirus, as well as ultrasound-guided in utero injections, were performed as described elsewhere (Beronja et al., 2010). shRNAs were obtained from the Broad Institute’s Mission TRC-1/2 mouse library.

Flow Cytometry

Preparation of adult mice backskins for isolation of keratinocytes and staining protocols were done as previously described (Nowak and Fuchs, 2009). Briefly, subcutaneous fat was removed from skins with a scalpel, and skins were placed dermis side down on trypsin (Gibco) at 37 °C for 45 minutes. Single-cell suspensions were obtained by scraping the skin to remove the epidermis and hair follicles from the dermis. Cells were then filtered through 70mm, followed by 40mm strainers. Cell suspensions were incubated with the appropriate antibodies for 30 minutes on ice. The following antibodies were used for FACS: α6-integrin (BD Pharmingen), CD34 (eBiosciences) and Sca-1 (eBiosciences). DAPI was used to exclude dead cells. Cell isolations were performed on FACS Aria sorters running FACS Diva software (BD Biosciences). For EdU incorporation experiments, staining was performed using Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 488 Flow Cytometry Kit (Life Technologies) per manufacturer’s instructions. FACS analyses were performed using LSRII FACS Analyzers and results were analyzed with FlowJo software.

For analysis of immune cells at the wound site, wound tissue was isolated from the backskin, keeping margins as close to wound as possible. Tissue was minced in media (RPMI with L-glutamine, Sodium pyruvate, acid free HEPES, Penicillin and streptomycin) then Liberase TL (Roche) was added (25μg/ml) and tissue was digested for 90 minutes at 37°C while shaking gently. The digest reaction was stopped by addition of 20ml of 0.5M EDTA and 1ml of 10% DNase solution. Cells were passed through a 70mm strainer and stained with the following antibodies from eBiosciences: Ly6c-FITC 1:100, Ly6g-PE 1:200, CD11c-PECy7 1:150, CD11b-PacBlue 1:300, MHCII-AF700 1:300, CD45-A780 1:100, CD64-PerCP-Cy5 1:200, TCRβ-PCRP 1:200, γδTCR-APC 1:400. Dead cells were excluded using a LIVE/DEAD Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain Kit (Molecular Probes), for UV excitation. FACS analyses were performed using LSRII FACS Analyzers and results were analyzed with FlowJo software.

RT-qPCR

RNA was purified from FACS sorted cells by directly sorting into TrizolLS (Invitrogen) and purified using Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep kit (Zymo Research). Equivalent amounts of RNA were reverse-transcribed by SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). cDNAs were normalized to equal amounts using primers against β-actin. cDNAs were mixed with indicated primers and Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), and quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed on a Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system. Primer sequences for RT-PCR were obtained from Roche Universal ProbeLibrary.

For Vγ5 qPCR, unwounded and wounded skin was incubated in 50mM EDTA for 1hour, to separate epidermis was separated from dermis. Epidermal cells were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen tissues were homogenized using Bessman Tissue Pulverizer (SpectrumTM) and collected in Trizol (Invitrogen). RNA was extracted using Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep kit (Zymo Research) per manufacturer’s instructions. Equivalent amounts of RNA were reverse-transcribed by SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). cDNAs were mixed with indicated primers and Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (AppliedBiosystems), and quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed on a Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system.

Quantification and Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test was used to determine the significance between two groups with Prism5 software. Box-and-whisker plots are used to describe the entire population without assumptions about the statistical distribution. Error bars plotted on graphs denote SEM. For all statistical tests, the 0.05 level of confidence was accepted as a significant difference.

Data Availability

RNA-seq data have been submitted to the NCBI-GEO under the accession number GSE74283.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Intrinsic and extrinsic defects impair wound re-epithelialization in aged skin

Loss of DETCs at the wound edge delays wound repair in aged skin

Epidermally expressed Skint3/9 mediates keratinocyte-DETC cross

IL6/STAT3 signaling regulates Skint expression and facilitates proper wound healing

Acknowledgments

We thank Fuchs’ lab colleagues Irina Matos and E Heller for help with microscopy; Shijing Liu and N Oshimori for intellectual input and suggestions; M Sribour and S Hacker for technical assistance in the mouse facility; JDLCruz-Racelis for assistance in tissue sectioning and culture; E Wong for genotyping; S Larson for assistance in tissue explants. Rockefeller University’s Comparative Bioscience Center (AAALAC accredited) provided care of mice in accordance with National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines and Flow Cytometry facility for FACS sorting. Weill Cornell Medical School Genomics Center conducted sequencing. E.F. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and a Senior Investigator of the Ellison Foundation for Aging Research. B.K. was funded by the NIH/NCI (1001328-01-CCL3350413-112580) and a Postdoctoral Fellowship from AFAR. S. Liu is a Jane Coffin Childs Postdoctoral Fellow and a Women & Science Fellow. A.A. is the recipient of a Merck graduate fellowship and a Medical Scientist Training Program traineeship. S. N. is a Damon Runyon Postdoctoral Fellow. This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-AR050452) and the Ellison Foundation (E.F.).

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, seven Supplemental figures, six Supplemental tables, and two Supplemental movies.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.K. and E.F. conceptualized the study. B.K. and E.F. wrote the manuscript. B.K., E.F., S.L. and S.N. designed experiments. B.K. characterized young and aged skin, performed wounding studies and analyzed re-epithelialization of young and aged backskin wounds; performed in vitro experiments and collected and analyzed in vivo RNA-seq data.; analyzed performed immune cell analysis and Skint knockdown studies and analysis of Skint expression. B.K. and S.Liu performed Stat3 cKO wounding experiments. S. Liu performed NON/ShiLtJ, FVBjax and FVBtac young mice wounding studies; aged ear skin wounding studies. Vγ5 qPCR was performed by S. Liu and C.P.L. S. Liu and S.N. performed the IL-6 explant experiments and provided immunology expertise in characterizing immune cell populations. L.P. assisted with wounding procedures. J.L. performed in utero lentiviral injections. M.N. and B.K. performed cell adhesion assays. H.A.P performed ultrathin sectioning and staining of young and aged skin; A.A. and B.K. provided bioinformatics and quantitation/statistics expertise.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

|

| ||

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|

| ||

| Antibodies | ||

|

| ||

| Guinea pig Anti-Mouse K5 | Fuchs Lab | N/A |

|

| ||

| Rabbit Anti-Mouse K14 | Fuchs Lab | N/A |

|

| ||

| Rabbit Anti-Mouse K17 | Fuchs Lab | N/A |

|

| ||

| Guinea pig Anti-Mouse K6 | Fuchs Lab | N/A |

|

| ||

| Rabbit Anti- K10 Clone: Poly19054 | Biolegend (Covance) | Cat# 905401 |

|

| ||

| Rabbit Anti Cleaved Caspase-3 Clone: 269518 | R&D | Cat# MAB 835 |

|

| ||

| Armenian Hamster Anti-gd TCR Clone: GL3 AF647 | Biolgend | Cat# 118133 |

|

| ||

| Armenian Hamster Anti-gd TCR Clone: GL3 | Biolgend | Cat# 118101 |

|

| ||

| Rabbit Anti-pStat3 (Tyr705) Clone:D3A7 | Cell Signaling | Cat# 9145 |

|

| ||

| Rat Anti-CD104 Clone: 346-11A | Biolegend | Cat#123602 |

|

| ||

| Syrian Hamster Anti-Mouse TCR Vg3 Clone: 536 | Biolegend | Cat# 137505 |

|

| ||

| Rat Anti-Mouse CD3e Clone: 17A2 | Biolegend | Cat# 100212 |

|

| ||

| Armenian Hamster Anti-MouseTCRb Clone: H57–597 | Biolegend | Cat# 109201 |

|

| ||

| Armenian Hamster Anti-MouseTCRb Clone: H57–597 PerCp/Cy5.5 | Biolegend | Cat# 109227 |

|

| ||

| Donkey Anti-Rabbit, AF488 conjugated secondary | Jackson ImmunoReseach | Cat# 711-545-152 |

|

| ||

| Donkey Anti-Rabbit AF546, conjugated secondary | Jackson ImmunoReseach | Cat# 711-165-152 |

|

| ||

| Donkey Anti-Rabbit AF647, conjugated secondary | Jackson ImmunoReseach | Cat# 711-605-152 |

|

| ||

| Donkey Anti-Guinea pig AF488, conjugated secondary | Jackson ImmunoReseach | Cat# 706-545-148 |

|

| ||

| Donkey Anti-Guinea pig RRX conjugated secondary | Jackson ImmunoReseach | Cat# 706-295-148 |

|

| ||

| Donkey Anti-Guinea pig AF647, conjugated secondary | Jackson ImmunoReseach | Cat# 706-605-148 |

|

| ||

| Donkey Anti-Rat AF488, conjugated secondary | Jackson ImmunoReseach | Cat# 712-545-150 |

|

| ||

| Donkey Anti-Rat RRX, conjugated secondary | Jackson ImmunoReseach | Cat# 712-295-150 |

|

| ||

| Donkey Anti-Rat AF647, conjugated secondary | Jackson ImmunoReseach | Cat# 712-605-150 |

|

| ||

| Anti-Mouse Ly6c-FITC Clone: HK1.4 | Biolegend | Cat# 128005 |

|

| ||

| Anti-Mouse Ly6g-PE Clone:1A8 | Biolegend | Cat# 127607 |

|

| ||

| Anti-Mouse CD11c-PECy7 Clone: N418 | Biolegend | Cat# 117317 |

|

| ||

| Anti-Mouse CD11b-PacBlue Clone: M1/70 | Biolegend | Cat# 101223 |

|

| ||

| Anti-Mouse 1-A/1-E-AF700 Clone:M5/114.15.2 | Biolegend | Cat# 107621 |

|

| ||

| Anti-Mouse CD45-AF750 Clone: 30-F11 | Biolegend | Cat# 103153 |

|

| ||

| Anti-Mouse CD64-PerCP-Cy5 Clone:X54-5/7.1 | Biolegend | Cat# 139307 |

|

| ||

| Anti-Mouse CD34 eFluor 660 Clone: RAM34 | eBiosciences | Cat# 50-0341-82 |

|

| ||

| Anti-mouse Ly-6A/E (Sca-1) PerCP-Cy5.5 | eBiosciences | Cat# 45-5981-82 |

|

| ||

| Anti-Human CD49f (α6-integrin) PE | BD Pharmingen | Cat# 555736 |

|

| ||

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

|

| ||

| OCT Compount Tissue Tek | VWR | Cat# 25608-930 |

|

| ||

| 4′6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 28718-90-3 |

|

| ||

| Prolong Gold | Invitrogen | Cat# P36930 |

|

| ||

| Ammonium Thiocyanate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 221988 |

|

| ||

| Glutaraldehyde Solution | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# G5882 |

|

| ||

| 16% Paraformaldehyde Solution | Electron Microscopy Sciences | Cat#15700 |

|

| ||

| Osmium Tetroxide | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 20816-12-0 |

|

| ||

| Mitomycin-C | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# M7949 |

|

| ||

| Trypan Blue | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# T8154 |

|

| ||

| Rhodamine B | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # R6626 |

|

| ||

| Recombinant Murine Interlukin-6 | R&D | Cat# 406-ML-CF |

|

| ||

| TRI Reagent | Sigma | Cat# T3934 |

|

| ||

| Poly-L-lysine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# P4707 |

|

| ||

| Bovine Serum Albumin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A7906 |

|

| ||

| Fibronectin Human Protein, Plasma | Millipore | Cat# FC010 |

|

| ||

| Corning Collagen I, Rat Taile | Corning | Cat# 354236 |

|

| ||

| Matrigel Matrix (Phenol Free) | Corning | Cat# 356237 |

|

| ||

| E-Media | Fuchs Lab | N/A |

|

| ||

| Trypsin-EDTA(25%) | Gibco | Cat# 25200056 |

|

| ||

| RPMI with L-glutamine | ThermoFisher | Cat# 11875-093 |

|

| ||

| Sodium Pyruvate (100mM) | ThermoFisher | Cat# 11360070 |

|

| ||

| Acid free HEPES (1M) | ThermoFisher | Cat# 15630080 |

|

| ||

| Liberase™ TL Research Grade | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 5401020001 |

|

| ||

| DNAse 1 from bovine pancreas | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# D4263 |

|

| ||

| LIVE/DEAD Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain Kit | ThermoFisher | Cat# L23105 |

|

| ||

| SYBR Green PCR Master Mix | Appliedbiosystems | Cat# 4367659 |

|

| ||

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

|

| ||

| Click-IT EdU Alexa-Flour Imaging Kit | Life Technologies | Cat# C10337 |

|

| ||

| Directzol™ RNA MiniPrep | Zymo | Cat# R2050 |

|

| ||

| TrueSeq RNA Library PrepKit | lllumina | Cat# RS-122-2001 |

|

| ||

| SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit and Master Mix | ThermoFisher | Cat# 11752050 |

|

| ||

| Deposited Data | ||

|

| ||

| Raw RNA-seq data files NCBI Gene Expression | This paper | GSE74283 |

|

| ||

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

|

| ||

| J2 fibroblast feeder cells | Fuchs Lab | N/A |

|

| ||

| Primary Mouse Keratinocyte Cell Lines | Fuchs Lab | N/A |

|

| ||

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

|

| ||

| C57BL6 Mice | Jackson Laboratories | JAX: 000664 |

|

| ||

| Aged C57BL6 Mice | NIA | |

|

| ||

| K14Cre | Fuchs Lab | N/A |

|

| ||

| Stat3fl/fl | Jackson Laboratories | JAX:016923 |

|

| ||

| FVB/NJ | Jackson Laboratories | JAX:001800 |

|

| ||

| FVB/NTac | Taconic Biosciences | N/A |

|

| ||

| Non/ShiLtj | Jackson Laboratories | JAX:002423 |

|

| ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

|

| ||

| pLKO.1 TRC Cloning Vector | Moffat et al 2006 | Addgene# 10878 |

|

| ||

| TRC Mouse Genome shRNA Library | Dharmacon | Cat# RMM4013 |

|

| ||

| Sequence-Based Reagents: See Supplemental Table 7 | ||

|

| ||

| Software and Algorithms | ||

|

| ||

| Fiji (ImageJ) | https://fiji.sc/ | N/A |

|

| ||

| Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator CS5 | Adobe.com | N/A |

|

| ||

| R | https://www.r-project.org/ | N/A |

|

| ||

| Bowtie2 | Trapnell et. al 2012, Trapnel et. al., 2010 | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml |

|

| ||

| CummeRbund package in R | http://compbio.mit.edu/cummeRbund/ | N/A |

|

| ||

| Cufflinks | Trapnell et. al 2012, Trapnell et. al., 2010 | http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/cufflinks/ |

|

| ||

| Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) | Tamayo, et al. 2005, Mootha, Lindgren, et al. 2003 | http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp |

|

| ||

| MEME software suite (including TomTom) | Bailey TL et al. 2009 | http://meme-suite.org/doc/cite.html?man_type=web |

|

| ||

| FACS Diva software | BD Biosciences | N/A |

|

| ||

| FlowJo Software | FlowJo | N/A |

|

| ||

| Prism | Graphpad | N/A |

|

| ||

| Other | ||

|

| ||

| Sterile 1.5mm, 2mm, 4mm and 6mm Biopsy punch (Miltex) | Integra | Cat# 33-31A, 33-31, 33-34, 33-36 |

|

| ||

| Spectrum Tissue Pulverizer | Fisher Scientific | Cat# 189476 |

|

| ||

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ashcroft GS, Mills SJ, Ashworth JJ. Ageing and wound healing. Biogerontology. 2002;3:337–345. doi: 10.1023/a:1021399228395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, Ren J, Li WW, Noble WS. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbee SD, Woodward MJ, Turchinovich G, Mention JJ, Lewis JM, Boyden LM, Lifton RP, Tigelaar R, Hayday AC. Skint-1 is a highly specific, unique selecting component for epidermal T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:3330–3335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010890108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beronja S, Livshits G, Williams S, Fuchs E. Rapid functional dissection of genetic networks via tissue-specific transduction and RNAi in mouse embryos. Nat Med. 2010;16:821–827. doi: 10.1038/nm.2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden LM, Lewis JM, Barbee SD, Bas A, Girardi M, Hayday AC, Tigelaar RE, Lifton RP. Skint1, the prototype of a newly identified immunoglobulin superfamily gene cluster, positively selects epidermal gammadelta T cells. Nat Genet. 2008;40:656–662. doi: 10.1038/ng.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burzyn D, Kuswanto W, Kolodin D, Shadrach JL, Cerletti M, Jang Y, Sefik E, Tan TG, Wagers AJ, Benoist C, et al. A special population of regulatory T cells potentiates muscle repair. Cell. 2013;155:1282–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho L, Jacinto A, Matova N. The Toll/NF-κB signaling pathway is required for epidermal wound repair in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E5373–E5382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408224111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellana D, Paus R, Perez-Moreno M. Macrophages contribute to the cyclic activation of adult hair follicle stem cells. Plos Biol. 2014;12:e1002002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodaczek G, Papanna V, Zal MA, Zal T. Body-barrier surveillance by epidermal γδ TCRs. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:272–282. doi: 10.1038/ni.2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depianto D, Kerns ML, Dlugosz AA, Coulombe PA. Keratin 17 promotes epithelial proliferation and tumor growth by polarizing the immune response in skin. Nat Genet. 2010;42:910–914. doi: 10.1038/ng.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]