Abstract

Pathological stage is the most important prognostic factor in patients with lung cancer, and is defined according to the tumor node metastasis classification system. The present study aimed to investigate the clinicopathological significance of lymphatic invasion in 103 patients who underwent surgical resection of lung squamous cell carcinoma (SqCC). The patients were divided into two groups, according to the degree of lymphatic invasion: Those with no or mild lymphatic invasion (ly0-1) and those with moderate or severe lymphatic invasion (ly2-3). Ly2-3 was associated with tumor size (P=0.028), lymph node metastasis (P<0.001), venous invasion (P=0.001) and histological differentiation (P=0.047). Statistical analysis using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test indicated that overall survival was significantly reduced in patients with ly2-3 compared with those with ly0-1 (P<0.001). Multivariate analysis identified ly2-3 as an independent predictor of mortality (hazard ratio, 2.580; 95% confidence interval, 1.376–4.839). In conclusion, moderate or severe lymphatic invasion (ly2-3) indicated a high malignant potential and may be considered an independent predictor of poor prognosis in patients with SqCC of the lung.

Keywords: lung cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, lymph node metastasis, prognosis

Introduction

Cancer stage is defined according to the International Union against Cancer tumor node metastasis (TNM) classification system (1). Other characteristics, including histological differentiation, tumor infiltration (INF) pattern, stromal type, blood vessel invasion and lymphatic invasion are also used to assess tumors (2–4). These other characteristics are not used to determine pathological stage; however, some studies have reported that they may help to predict outcomes (2–10). Some patients with lung cancer only undergo limited resection due to poor lung function (11,12). Patients with lung squamous cell carcinoma (SqCC) occasionally exhibit chronic obstructive pulmonary disease due to smoking (13,14), and often require limited lung resection without systematic lymph node dissection. In these cases, the lymph nodes, which are the N factor in the TNM classification system, cannot be pathologically evaluated, and thus the pathological stage cannot be determined. Therefore, it is difficult to evaluate the need for adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and to predict prognosis.

In our previous study, we examined the INF pattern in lung SqCC specimens; the samples were divided into two groups: The INFc(−) group, which exhibited clear borders between the tumor and surrounding normal tissues, and the INFc(+) group, which did not exhibit clear borders between the tumor and surrounding normal tissues (6,15–17). The results demonstrated that INFc(+) was significantly associated with venous invasion, scirrhous stromal type and poorer postoperative survival, thus suggesting that INFc(+) may be considered a useful marker of local invasiveness. Determination of various histological characteristics of primary lesions are important for patients with recurrent lung SqCC, since there are few therapeutic options available for these patients compared with patients with adenocarcinoma (18–24). Histological vascular invasion has been reported to predict prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer (8–10). Several studies regarding non-small cell lung cancer have predominantly focused on patients with adenocarcinoma, whereas no previous studies have focused specifically on patients with SqCC, to the best of our knowledge (8–10). The present study investigated the association between the degree of lymphatic invasion and prognosis in patients with SqCC of the lung. The aim of the present study was to investigate whether the pattern of lymphatic invasion and other clinicopathological characteristics may be used to predict prognosis in patients with SqCC of the lung.

Materials and methods

Lung cancer specimens

Resected specimens were collected from patients treated for SqCC of the lung. The samples were examined after receiving informed consent from the patients. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tokai University Hospital (Isehara, Japan). The present study included 103 patients with SqCC of the lung (97 males and 6 females; age range, 43–85 years; mean age, 67.2±9.1 years) who underwent radical surgery (lobectomy and mediastinal lymphadenectomy) at Tokai University Hospital. For each patient, tumor stage was defined according to the TNM classification system (25) and the histological type was defined according to the World Health Organization classification (26). The median postoperative follow-up period was 1,528 days (range, 41-3,837 days).

Histological examination

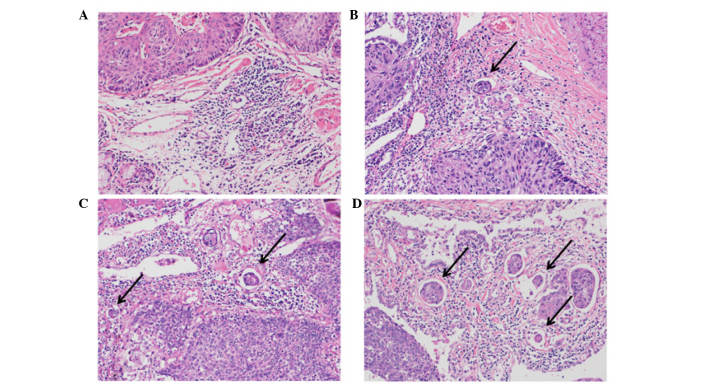

The lung tissue specimens were fixed with 10% buffered formalin for 24–48 h, embedded in paraffin according to routine techniques, and 4-µm sections were sliced at 5–10 mm intervals. Sections were examined using an optical microscope. INF pattern and lymphatic invasion were examined on sections, which were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Vascular and pleural invasion were examined using Verhoeff-van Gieson staining as follows: Incubation with Verhoeff solution [5% alcohol hematoxylin, 10% ferric chloride and Weigert iodine solution (Muto Pure Chemicals Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan)] for 60 min at room temperature; and then van Gieson solution [1% aqueous acid fuchsin: (Muto Pure Chemicals Co., Ltd.)] for 10 min at room temperature. The degree of lymphatic invasion was classified as follows: Ly0, no lymphatic invasion; ly1, mild lymphatic invasion; ly2, moderate lymphatic invasion; or ly3, severe lymphatic invasion (Fig. 1). The degree of venous invasion was classified as follows: V0, no venous invasion; v1, minimal venous invasion (1 or 2 foci of venous invasion per histological section); v2, moderate venous invasion (3 or 4 foci); or v3, severe venous invasion (≥5 foci).

Figure 1.

Microscopic images of lung squamous cell carcinoma samples (hematoxylin and eosin staining). (A) No lymphatic invasion, (B) mild lymphatic invasion, (C) moderate lymphatic invasion and (D) severe lymphatic invasion. Arrows indicate foci of lymphatic invasion. Original magnification, ×200.

The INF pattern was described as previously reported in gastric cancer studies (15–17): INFa, cancer nests exhibited expanding growth and a distinct border with the surrounding tissues; INFb, characteristics between those of INFa and INFc; and INFc, cancer nests exhibited infiltrative growth and an indistinct border with the surrounding tissues. Since some specimens included two INF patterns, the patients were divided into seven INF categories: INFa, INFa>b, INFa<b, INFb, INFb>c, INFb<c, and INFc. These seven categories were divided into an INFc(−) group, which consisted of INFa, INFa>b, INFa<b and INFb; and an INFc(+) group, which consisted of INFb>c, INFb<c and INFc (4,6).

The degree of lymph node metastasis was classified according to the TNM system as follows: N0, no lymph node metastasis; N1, ipsilateral peribronchial and/or hilar lymph node metastasis; or N2, ipsilateral mediastinal and/or subcarinal lymph node metastasis (26). The stromal type (i.e., the cancer-stroma relationship pattern) was classified as follows: Medullary, with scanty stroma; intermediate, with a quantity of stroma intermediate between the scirrhous and medullary types; and scirrhous, with abundant stroma (15).

Statistical analysis

Univariate analyses were performed to identify significant differences between the groups (χ2 test, P<0.05). Cox univariate and multivariate proportional hazard regression analyses were performed to determine the independent effects of individual factors while controlling for the effects of the other factors. Univariate and multivariate analyses were also performed to investigate the association between the degree of lymphatic invasion and patient prognosis. Multivariate analysis was performed for all factors; five representative factors are presented in the present study. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to assess the impact of individual factors on prognosis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Patient survival was measured from the date of surgery until mortality from any cause. Survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method and were compared using the log-rank test. All analyses were performed using the SPSS II statistical software package (version 19.0; IBM SPSS, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Association between lymphatic invasion and patient survival

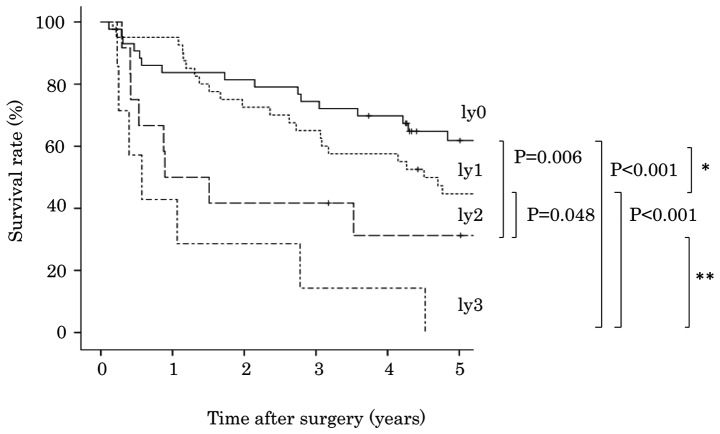

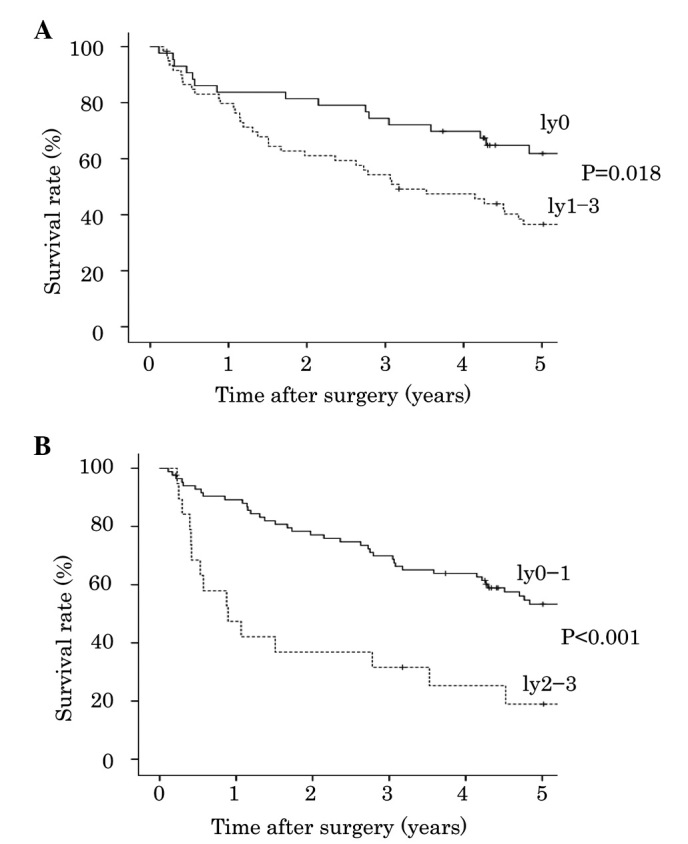

The degree of lymphatic invasion was classified into four groups: Ly0 in 43 cases (41.7%), ly1 in 41 cases (39.8%), ly2 in 12 cases (11.7%) and ly3 in 7 cases (6.8%). The association between degree of lymphatic invasion and patient survival is presented in Table I. Analysis using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test indicated that patients with ly2 exhibited poorer survival compared with patients with ly1 (P=0.048; Fig. 2). However, overall survival was not significantly different between patients with ly0 and ly1 (P=0.237), or between patients with ly2 and ly3 (P=0.138). A more statistically significant difference was detected between patients with ly0-1 and ly2-3 (P<0.001), compared with between patients with ly0 and ly1-3 (P=0.018, Fig. 3).

Table I.

Lymphatic invasion and survival in patients with lung squamous cell carcinoma.

| Variable | No. of patients (%) | P-value | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphatic invasion | <0.001 | |||

| ly0 | 43 (41.7) | 1.854 | 1.390–2.474 | |

| ly1-3 | 60 (58.3) | |||

| Lymphatic invasion | <0.001 | |||

| ly0-1 | 84 (91.6) | 3.298 | 1.827–5.952 | |

| ly2-3 | 19 (18.4) | |||

| Lymphatic invasion | <0.001 | |||

| ly0-2 | 96 (93.2) | 4.752 | 2.115–10.677 | |

| ly3 | 7 (6.8) |

Figure 2.

Degree of lymphatic invasion and cumulative survival of patients with lung squamous cell carcinoma. *P=0.237, **P=0.138; Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test.

Figure 3.

Degree of lymphatic invasion and cumulative survival of patients with lung squamous cell carcinoma. (A) Ly0 vs. ly1-3; (B) ly0-1 vs. ly2-3; Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test.

Association between lymphatic invasion and clinicopathological features

The stromal type of SqCC was medullary in 39 cases (37.9%), intermediate in 31 cases (30.1%), and scirrhous in 33 cases (32.0%). The INF patterns were classified as follows: INFa in 11 patients (10.7%), INFa>b in 10 patients (9.7%), INFb in 43 patients (41.7%), INFb>c in 31 patients (30.1%), INFb<c in 4 patients (3.9%), and INFc in 4 patients (3.9%); therefore, 64 patients (62.1%) were classified as INFc(+) and 39 patients (37.9%) were classified as INFc(−). The associations between degree of lymphatic invasion and clinicopathological features are presented in Table II. Ly2-3 was significantly associated with larger tumor size (P=0.028), lymph node metastasis (P<0.001), venous invasion (P=0.001) and poor differentiation (P=0.047), as compared with ly0-1. Univariate analyses identified five factors that were significantly associated with increased mortality (Table III): Increased tumor size (HR, 1.897; 95% CI, 1.059–3.396); lymph node metastasis (HR, 3.028; 95% CI, 1.785–5.136); lymphatic invasion (HR, 3.298; 95% CI, 1.827–5.952); poor differentiation (HR, 2.092; 95% CI, 1.050–4.168) and INFc(−) (HR, 2.209; 95% CI, 1.301–3.749). Scirrhous stromal type was not significantly associated with survival (HR, 1.229; 95% CI, 0.706–2.139). In addition, multivariate analysis identified ly2-3 as an independent predictor of mortality (HR, 2.580; 95% CI, 1.376–4.839; Table IV).

Table II.

Lymphatic invasion and clinicopathological features of lung squamous cell carcinoma.

| Variable | No. of patients (%) | ly0-1 (%) | ly2-3 (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at surgery (years) | 0.910 | |||

| <68 | 53 (51.5) | 43 (81.1) | 10 (18.9) | |

| ≥68 | 50 (48.5) | 41 (82.0) | 9 (18.0) | |

| Gender | 0.230 | |||

| Male | 97 (94.2) | 78 (80.4) | 19 (19.6) | |

| Female | 6 (5.8) | 6 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Tumor size (mm) | 0.028 | |||

| ≤30 | 39 (37.9) | 36 (92.3) | 3 (7.7) | |

| >30 | 64 (62.1) | 48 (75.0) | 16 (25.0) | |

| Lymph node metastasis | <0.001 | |||

| n(−) | 70 (68.0) | 66 (94.3) | 4 (5.7) | |

| n(+) | 33 (32.0) | 18 (54.5) | 15 (45.5) | |

| Venous invasion | 0.001 | |||

| v(−) | 53 (51.5) | 50 (94.3) | 3 (5.7) | |

| v(+) | 50 (48.5) | 34 (68.0) | 16 (32.0) | |

| Histological differentiation | 0.047 | |||

| Well, moderate | 90 (87.4) | 76 (84.4) | 14 (15.6) | |

| Poorly | 13 (12.6) | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | |

| Stromal type | 0.298 | |||

| Medullary, intermediate | 70 (68.0) | 59 (84.3) | 11 (15.7) | |

| Scirrhous | 33 (32.0) | 25 (75.8) | 8 (24.2) | |

| Infiltrating pattern | 0.142 | |||

| INFc(−) | 64 (62.1) | 55 (85.9) | 9 (14.1) | |

| INFc(+) | 39 (37.9) | 29 (74.4) | 10 (25.6) |

n(−)/n(+), lymph node metastasis negative/positive; v(−)/v(+), venous invasion negative/positive; INFc(−)/INFc(+), infiltrating component negative/positive.

Table III.

Clinicopathological features and survival in patients with lung squamous cell carcinoma.

| Variable | No. of patients (%) | P-value | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at surgery (years) | 0.131 | |||

| <68 | 53 (51.5) | 1.502 | 0.885–2.548 | |

| ≥68 | 50 (48.5) | |||

| Gender | 0.904 | |||

| Male | 97 (94.2) | 0.939 | 0.339–2.602 | |

| Female | 6 (5.8) | |||

| Tumor size (mm) | 0.031 | |||

| ≤30 | 39 (37.9) | 1.897 | 1.059–3.396 | |

| >30 | 64 (62.1) | |||

| Lymph node metastasis | <0.001 | |||

| n(−) | 70 (68.0) | 3.028 | 1.785–5.136 | |

| n(+) | 33 (32.0) | |||

| Lymphatic invasion | <0.001 | |||

| ly0 | 43 (41.7) | 1.854 | 1.390–2.474 | |

| ly1-3 | 60 (58.3) | |||

| Lymphatic invasion | <0.001 | |||

| ly0-1 | 84 (91.6) | 3.298 | 1.827–5.952 | |

| ly2-3 | 19 (18.4) | |||

| Venous invasion | 0.145 | |||

| v(−) | 53 (51.5) | 1.486 | 0.873–2.530 | |

| v(+) | 50 (48.5) | |||

| Histological differentiation | 0.036 | |||

| Well, mod | 90 (87.4) | 2.092 | 1.050–4.168 | |

| Poorly | 13 (12.6) | |||

| Stromal type | 0.465 | |||

| Medullary, intermediate | 70 (68.0) | 1.229 | 0.706–2.139 | |

| Scirrhous | 33 (32.0) | |||

| Infiltrating pattern | 0.003 | |||

| INFc(−) | 64 (62.1) | 2.209 | 1.301–3.749 | |

| INFc(+) | 39 (37.9) |

n(−)/n(+), lymph node metastasis negative/positive; v(−)/v(+), venous invasion negative/positive; INFc(−)/INFc(+), infiltrating component negative/positive.

Table IV.

Multivariate analysis of clinicopathological features and survival in patients with lung squamous cell carcinoma.

| Variable | No. of patients (%) | P-value | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at surgery (years) | 0.179 | |||

| <68 | 53 (51.5) | 1.461 | 0.840–2.540 | |

| ≥68 | 50 (48.5) | |||

| Gender | 0.784 | |||

| Male | 97 (94.2) | 1.157 | 0.408–3.281 | |

| Female | 6 (5.8) | |||

| Tumor size (mm) | 0.083 | |||

| ≤30 | 39 (37.9) | 1.700 | 0.933–3.098 | |

| >30 | 64 (62.1) | |||

| Infiltrating pattern | 0.058 | |||

| INFc(−) | 64 (62.1) | 1.723 | 0.981–3.027 | |

| INFc(+) | 39 (37.9) | |||

| Lymphatic invasion | 0.003 | |||

| ly0-1 | 84 (81.6) | 2.580 | 1.376–4.839 | |

| ly2-3 | 19 (18.4) |

INFc(−)/INFc(+), infiltrating component negative/positive.

Discussion

The present study investigated the degree of lymphatic invasion and other clinicopathological features of lung SqCC, and demonstrated that ly2-3 was associated with higher malignant potential compared with ly0-1. A total of 18% of patients with lung SqCC had ly2-3, and exhibited higher rates of lymph node metastasis and poorer overall survival compared with those with ly0-1. A previous study reported that vessel invasion was a predictor of poor prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (8–10). However, the majority of patients in that previous study had adenocarcinoma, and lymphatic invasion has not previously been reported as a potential prognostic factor in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report an association between the degree of lymphatic invasion and prognosis in patients with lung SqCC.

Several patients with lung SqCC have undergone surgical resection due to advances in imaging, other diagnostic techniques, and operative procedures (27,28). In these patients, the most important prognostic factor is thought to be pathological stage according to the TNM classification system. Although lobectomy and lymph node dissection are standard surgical procedures, some patients with poor pulmonary function only undergo limited resection without lymph node dissection. In these patients, lymph node metastasis (N factor) is histologically unclear, and the pathological stage cannot be determined. The main histological information is obtained from the primary tumor (T factor, which predominantly accounts for tumor size), which is insufficient to determine prognosis. Lung cancer is evaluated according to morphological features, including histological type, histological differentiation, pleural invasion, blood vessel invasion and lymphatic invasion (8–10). Evaluations of cancer in other organs include histological factors, such as the INF pattern and stromal type (4–7,29,30). Therefore, the present study considered it important to evaluate these factors in lung cancer, in combination with the conventional factors. Various treatments are currently available for patients who develop postoperative recurrence of lung adenocarcinoma; however, there are not any effective treatments available for patients who develop postoperative recurrence of lung SqCC (20–24). Therefore, the identification of factors that predict patient prognosis is important for SqCC, in order to enable early detection and treatment of recurrence, and to determine the need for postoperative adjuvant therapy. In addition, adenocarcinoma, SqCC and large cell carcinoma are all categorized as non-small cell carcinoma. However, ~35% of non-small cell carcinoma cases are SqCC, and SqCC must be studied separately from adenocarcinoma.

Our previous study reported an association between INF pattern and survival in patients undergoing treatment for SqCC of the lung (6). The present study evaluated the local aggressiveness of SqCC by the degree of lymphatic invasion. When patients were classified into two groups, namely, those with positive (ly1-3) or negative (ly0) lymphatic invasion, a significant difference in survival was observed between them. However, there was a more statistically significant difference in survival between patients with ly0-1 and ly2-3. Univariate analysis indicated a significant difference in survival between patients with ly1-3 and ly0; however, the HR was 1.854, which was lower than the HR of 3.298 for the comparison of survival between patients with ly0-1 and ly2-3. Lymph node metastasis was excluded from the multivariate analysis since there was a moderate linear relationship between lymphatic invasion and lymph node metastasis. This finding may help to predict the prognosis in patients undergoing limited resection. In the present study, patients with ly2-3 exhibited a significantly higher rate of lymph node metastasis compared with those with ly0-1 (P<0.001). Since the prediction of lymph node metastasis is important in patients with lung cancer who may undergo limited resection, the authors of the present study aim to conduct further studies to clarify the relationship between lymph node metastasis and the morphological features of SqCC using immunohistochemical/molecular analyses. The present study also analyzed the relationship between venous invasion and prognosis, but found no significant differences in prognosis among the categories of blood vessel invasion (data not shown).

In conclusion, the degree of lymphatic invasion in lung SqCC is associated with local tumor aggressiveness, and may be a useful indicator of prognosis.

References

- 1.Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, Giroux DJ, Groome PA, Rami-Porta R, Postmus PE, Rusch V, Sobin L. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer International Staging Committee; Participating Institutions: The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:706–714. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung CK, Zaino R, Stryker JA, O'Neill M, Jr, DeMuth WE., Jr Carcinoma of the lung: Evaluation of histological grade and factors influencing prognosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1982;33:599–604. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(10)60819-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gajra A, Newman N, Gamble GP, Abraham NZ, Kohman LJ, Graziano SL. Impact of tumor size on survival in stage IA non-small cell lung cancer: A case for subdividing stage IA disease. Lung Cancer. 2003;42:51–57. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5002(03)00285-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ito E, Ozawa S, Kijima H, Kazuno A, Nishi T, Chino O, Shimada H, Tanaka M, Inoue S, Inokuchi S, Makuuchi H. New invasive patterns as a prognostic factor for superficial esophageal cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1279–1289. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0587-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okada K, Kijima H, Imaizumi T, Hirabayashi K, Matsuyama M, Yazawa N, Dowaki S, Tobita K, Ohtani Y, Tanaka M, et al. Clinical significance of wall invasion pattern of subserosa-invasive gallbladder carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:1531–1536. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masuda R, Kijima H, Imamura N, Aruga N, Nakamura Y, Masuda D, Takeichi H, Kato N, Nakagawa T, Tanaka M, et al. Tumor budding is a significant indicator of a poor prognosis in lung squamous cell carcinoma patients. Mol Med Rep. 2012;6:937–943. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yokota T, Kunii Y, Teshima S, Yamada Y, Saito T, Takahashi M, Kikuchi S, Yamauchi H. Significant prognostic factors in patients with early gastric cancer. Int Surg. 2000;85:286–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harpole DH, Jr, JE II Herndon, Young WG, Jr, Wolfe WG, Sabiston DC., Jr Stage I nonsmall cell lung cancer. A multivariate analysis of treatment methods and patterns of recurrence. Cancer. 1995;76:787–796. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950901)76:5<787::AID-CNCR2820760512>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ichinose Y, Yano T, Asoh H, Yokoyama H, Yoshino I, Katsuda Y. Prognostic factors obtained by a pathologic examination in completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer. An analysis in each pathologic stage. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110:601–605. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(95)70090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duarte IG, Bufkin BL, Pennington MF, Gal AA, Cohen C, Kosinski AS, Mansour KA, Miller JI. Angiogenesis as a predictor of survival after surgical resection for stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;115:652–659. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70331-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crabbe MM, Patrissi GA, Fontenelle LJ. Minimal resection for bronchogenic carcinoma. An update. Chest. 1991;99:1421–1424. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.6.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martini N, Rusch VW, Bains MS, Kris MG, Downey RJ, Flehinger BJ, Ginsberg RJ. Factors influencing ten-year survival in resected stages I to IIIa non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:32–38. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(99)70467-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hylkema MN, Sterk PJ, deBoer WI, Postma DS. Tobacco use in relation to COPD and asthma. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:438–445. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00124506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gratziou Ch, Florou A, Ischaki E, Eleftheriou K, Sachlas A, Bersimis S, Zakynthinos S. Smoking cessation effectiveness in smokers with COPD and asthma under real life conditions. Respir Med. 2014;108:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association, corp-author. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101–112. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maehara Y, Oshiro T, Adachi Y, Ohno S, Akazawa K, Sugimachi K. Growth pattern and prognosis of gastric cancer invading the subserosa. J Surg Oncol. 1994;55:203–208. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930550402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haraguchi M, Yamamoto M, Saito A, Kakeji Y, Orita H, Korenaga D, Sugimachi K. Prognostic value of depth and pattern of stomach wall invasion in patients with an advanced gastric carcinoma. Semin Surg Oncol. 1994;10:125–129. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980100213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dembitzer FR, Flores RM, Parides MK, Beasley MB. Impact of histological subtyping on outcome in lobar vs sublobar resections for lung cancer: A pilot study. Chest. 2014;146:175–181. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koike T, Koike T, Yoshiya K, Tsuchida M, Toyabe S. Risk factor analysis of locoregional recurrence after sublobar resection in patients with clinical stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146:372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossi A, Ricciardi S, Maione P, de Marinis F, Gridelli C. Pemetrexed in the treatment of advanced non-squamous lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2009;66:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, Brahmer J, Schiller JH, Dowlati A, Lilenbaum R, Johnson DH. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reck M, von Pawel J, Zatloukal P, Ramlau R, Gorbounova V, Hirsh V, Leighl N, Mezger J, Archer V, Moore N, Manegold C. Phase III trial of cisplatin plus gemcitabine with either placebo or bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAil. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1227–1234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosell R, Perez-Roca L, Sanchez JJ, Cobo M, Moran T, Chaib I, Provencio M, Domine M, Sala MA, Jimenez U, et al. Customized treatment in non-small-cell lung cancer based on EGFR mutations and BRCA1 mRNA expression. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong J, Kyung SY, Lee SP, Park JW, Jung SH, Lee JI, Park SH, Sym SJ, Park J, Cho EK, et al. Pemetrexed versus gefitinib versus erlotinib in previously treated patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Korean J Intern Med. 2010;25:294–300. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2010.25.3.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors. 7th edition. Wiley; Oxford: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Müller-Hermelin HK, Harris CC. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. IARC Press; Lyon: 2004. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beattie G, Bannon F, McGuigan J. Lung cancer resection rates have increased significantly in females during a 15-year period. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;38:484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin-Ucar AE, Waller DA, Atkins JL, Swinson D, O'Byrne KJ, Peake MD. The beneficial effects of specialist thoracic surgery on the resection rate for non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2004;46:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masuda R, Kijima H, Imamura N, Aruga N, Nakazato K, Oiwa K, Nakano T, Watanabe H, Ikoma Y, Tanaka M, et al. Laminin-5γ2 chain expression is associated with tumor cell invasiveness and prognosis of lung squamous cell carcinoma. Biomed Res. 2012;33:309–317. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.33.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okada K, Kijima H, Imaizumi T, Hirabayashi K, Matsuyama M, Yazawa N, Oida Y, Dowaki S, Tobita K, Ohtani Y, et al. Stromal laminin-5gamma2 chain expression is associated with the wall-invasion pattern of gallbladder adenocarcinoma. Biomed Res. 2009;30:53–62. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.30.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]