Abstract

We examine the relationships among the division of housework and childcare labor, perceptions of its fairness for two types of family labor (housework and childcare), and parents’ relationship conflict across the transition to parenthood. Perceived fairness is examined as a mediator of the relationships between change in the division of housework and childcare and relationship conflict. Working-class, dual-earner couples (n = 108) in the U.S Northeast were interviewed at five time points from the third trimester of pregnancy and across the first year of parenthood. Research questions addressed whether change in the division of housework and childcare across the transition to parenthood predicted mothers’ and fathers’ relationship conflict, with attention to the mediating role of perceived fairness of these chores. Findings for housework indicated that perceived fairness was related to relationship conflict for mothers and fathers, such that when spouses perceived the change in the division of household tasks to be unfair to either partner, they reported more conflict, However, fairness did not significantly mediate relations between changes in division of household tasks and later relationship conflict. For childcare, fairness mediated relations between mothers’ violated expectations concerning the division of childcare and later conflict such that mothers reported less conflict when they perceived the division of childcare as less unfair to themselves; there was no relationship for fathers. Findings highlight the importance of considering both childcare and household tasks independently in our models and suggest that the division of housework and childcare holds different implications for mothers’ and fathers’ assessments of relationship conflict.

Keywords: transition to parenthood, housework/division of labor, childcare, multilevel models, working-class families, relationship conflict

Families headed by dual-earner couples have become the norm in the United States, with 55.3% of heterosexual married couples with children under 6 both employed in 2014 and with a high of 56.9% in 2000 when data for the current study were collected (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2001, 2015). Even when both spouses are employed full-time, wives still do the majority of household work (Bianchi, Sayer, Milkie, & Robinson, 2012; Erickson, 2005; Mannino & Deutsch, 2007) and childcare (Bianchi, Milkie, Sayer, & Robinson, 2000; Biehle & Mickelson, 2012). Davis and Greenstein (2013, p. 63) propose that the division of labor in families continues to be a popular focus of study for social scientists because it “provides insight into the power and equity in intimate relationships.” We know surprisingly little, however, about how conditions of social class (i.e., income, education, occupation) in combination with gender, which are known to shape experiences of power and equity across many contexts including families, influence how labor is divided in families, as well as the meaning given to that labor and its implications for close relationships (Ferree, 1984; Perry-Jenkins, Newkirk, & Ghunney, 2013). For example, among low-income couples, both parents more often return to paid work soon after the birth of their child as compared to middle-class couples—a pattern likely to shape the division of labor. Thus, an aim of the current study is to consider how social class provides a context that shapes the relationship between the division of housework and childcare labor and relationship quality. We accomplish this goal by looking within a sample of working-class new parents as they juggle the demands of new parenthood and their concurrent return to paid employment.

An often overlooked aspect of family labor, highlighted by Chong and Mickelson (2015), is the lack of attention to the differential effects of housework versus childcare on relationship dynamics, despite evidence indicating that childcare tasks and household tasks have differing values in relationships (Ishii-Kuntz & Coltrane, 1992; Poortman & van der Lippe, 2009). The transition to parenthood marks an important time to examine how housework and a new set of childcare responsibilities are divided, as well as if these divisions differentially predict new mothers’ and fathers’ relationship quality. In addition, a consistent finding in the division of household labor literature is that perceptions of fairness about family work are often more powerful predictors of relationship quality than the actual division of labor (Claffey & Mickelson, 2008; Grotte, Naylor, & Clark, 2002). Thus, the current study addresses the aforementioned issues by examining if and how (a) the divisions of housework and childcare tasks and (b) perceptions of their fairness are differentially related to relationship conflict for a sample of working-class, dual-earner parents across the transition to parenthood. To address these questions we use longitudinal, interview data collected from 108 couples to test models derived from social exchange and equity theories that explain how the division of labor is related to relationship conflict.

Social Class, Social Exchange, and Equity

At a broad level, an ecological perspective informs our work (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), as well as two theories, social exchange and equity, that have often been used to explain the division of labor and relationship quality. An ecological perspective challenges us to consider how social contexts (e.g., social class, ethnicity) shape the nature of relationships within families. For example, in terms of social class, much of what we know about the division of labor is in regard to middle-class families who are likely to have more resources, such as paid leave and higher incomes, making it possible for one parent to leave the work force and/or to buy services for family labor. These supports are rarely available for working-class couples, raising important questions about how they manage employment and family responsibilities with fewer resources. Moreover, competing forces are often at work in lower-income families: mothers are often employed because of financial necessity, yet at the same time, many working-class parents believe that mothers should be more responsible for family work (Deutsch, 1999; Shows & Gerstel, 2009). In the current study, these issues become magnified as working-class parents have their first child and return to paid employment soon after the birth; thus, parents must negotiate both housework and a new set of tasks around childcare while holding down full-time jobs.

Among couples who both work full-time, wives do approximately twice as much household labor as their husbands do, and the types of tasks spouses perform typically differ as well, with women doing more of the routine and daily chores (Bianchi et al., 2000, 2012). Social exchange theory and equity theory offer competing explanations for how the division of labor may be related to relationship quality (Chong & Mickelson, 2015; Sprecher, 2001; Yogev & Brett, 1985). Social exchange theory posits that individuals will attempt to maximize their rewards relative to their costs in a relationship, and they will be most satisfied when they are over-benefitted (perform a relatively smaller share of work) in comparison to their partner. The under-benefitted partner (partner performing the greater share of work) will experience more psychological distress which, if attributed to the over-benefitted partner, will result in poorer relationship quality.

In contrast, equity theory proposes that being in an inequitable relationship is distressing for both parties; both under-benefitted and over-benefitted partners would be more dissatisfied than partners whose division of labor is equitable (Kalmijn & Monden, 2011). Similar to exchange theory, equity theorists would posit that under-benefitted partners experience psychological distress if inequity is attributed to the over-benefitted partner, resulting in more relationship conflict. Moreover, an over-benefitted partner is expected to experience distress, albeit to a lesser extent, due to feelings of guilt over violations of the social value of fairness, resulting in greater relationship distress. Both exchange and equity theories would predict that partners who are under-benefitted would perceive the exchange as unfair and experience poorer relationship quality. For the over-benefitted partner, exchange theory would predict greater relationship quality, whereas equity theory would predict poorer relationship quality in comparison to partners in equal relationships, but better perceived relationship quality than that of the under-benefitted partner.

In a direct test of exchange versus equity theories, Yogev and Brett (1985) examined the division of housework and childcare in relation to marital satisfaction in a sample of middle-class couples. They found that an exchange perspective explained marital satisfaction for dual-earner husbands, such that the less they did the more satisfied they were. In contrast, dual-earner wives reported the highest satisfaction when the division of labor was fair to both, that is, when no partner was over- or under-benefitted. More recently, Klumb, Hoppman and Staats (2006), in a study of professional dual-earner couples in Germany, found support for an equity model such that both husbands and wives reported greater well-being when the division of labor was fair to both. The question of how these relationships may differ among a non-professional sample of working-class, dual-earner, heterosexual couples is addressed in the current study.

Household Tasks and Relationship Quality

According to both equity and exchange theories, perceptions of fairness of the division of labor should have a greater influence on relationship quality than the actual division because other types of inputs and outcomes (e.g., contribution to household income, useful skills) may be factored into assessments of fairness (Claffey & Mickelson, 2008; Dew & Wilcox, 2011; Frisco & Williams, 2003; Lavee & Katz, 2002). Although it is well established that heterosexual women do a disproportionate amount of household tasks (Bianchi et al., 2012), many women do not perceive an unequal division as unfair and are satisfied with doing more housework than their husbands do (Stevens, Kiger, & Mannon, 2005), making women's perceptions of fairness more likely to be related to relationship conflict than the division of labor itself.

Research on heterosexual men's sense of fairness is more limited, with one study finding no relationship between the division of household labor and husbands’ perceived fairness (Lavee & Katz, 2002) and others finding that husbands are more likely to perceive the division of housework as unfair to their wives when their wives do more (Kluwer, Heesink, & van de Vliert, 2002; Perry-Jenkins & Folk, 1994). Frisco and Williams (2003) found men's perceived unfairness of the division of household labor to be associated with lower levels of relationship happiness. In contrast, others have found no relation between husbands’ division of labor and marital outcomes (Kluwer, Heesink, & van de Vliert, 1996; Stevens, Kiger, & Riley, 2001). Recently, in one of the few studies to examine perceptions of fairness around childcare and housework, both types of labor were equally important for new mothers’ relationship satisfaction, but for fathers, only mothers’ perceived fairness of household labor (not childcare) at 1-month postpartum was positively, but marginally, related to fathers’ relationship satisfaction at 9 months. (Chong & Mickelson, 2015).

Childcare Tasks and Relationship Quality

Both men and women enjoy childcare more than housework (Poortman & van der Lippe, 2009); however, mothers still do twice as much childcare as fathers (Bianchi et al., 2000). Mothers are also more likely to have the role of primary parent, delegating tasks to fathers rather than sharing responsibilities (Craig, 2006; Meteyer & Perry-Jenkins, 2010). Few studies have examined the relation between the division of childcare and perceived fairness of that division. Claffey and Mickelson (2008) found that wives who performed more childcare perceived the overall division of family labor as less fair, and Kluwer and colleagues (2002) found a similar relation for mothers’ perceptions of fairness, but not fathers’. Stevens and colleagues (2001) examined a related construct to fairness, satisfaction with the division of childcare, and found that both men and women were more satisfied with a more even division of childcare.

The findings on the relationship between the division of childcare and marital outcomes are inconsistent. Stevens and colleagues (2005) found that, in families with children under 18 years-old, wives’ marital satisfaction was lower when they performed a greater share of childcare, except in cases in which mothers were satisfied with an inequitable division of childcare. In contrast, husbands who performed more childcare and were more satisfied with the division of childcare were less satisfied with married life. Pedersen, Minnotte, Mannon, and Kiger (2011) found that husbands who performed more childcare reported higher levels of marital burnout in families with children under 18 years-old. In a study of families with at least one child under age 6, Meier, McNaughton-Cassill, and Lynch (2006) found that husbands had higher marital satisfaction when they did more childcare but felt that their wives were “responsible” for childcare. Schober (2012) found different relations based on the age of children. Fathers’ greater share of childcare predicted mothers’ higher marital quality from ages 9 months to 5 years; whereas fathers’ higher frequency, but not share, of childcare predicted fathers’ higher marital quality from ages 3 years to 7 years. Other studies have found no relationship between the division of childcare and marital outcomes for either spouse (Deutsch, Lussier, & Servis, 1993; Ehrenberg, Gearing-Small, Hunter, & Small, 2001). In the only known study examining both the division of childcare and housework separately, as well as perceptions of their fairness, across the transition to parenthood, Chong and Mickelson (2015) found that fairness of both types of work predicted great satisfaction for mothers. In contrast, fathers’ perceived fairness with childcare at 1 month was unrelated to fathers’, but negatively related to mothers’, relationship satisfaction at 9 months. The authors interpret their finding as supporting exchange theory, such that fathers’ perception of inequity in childcare (i.e., mother does more) as “fair” suggests that mothers are under-benefitted and, consequently, dissatisfied with the relationship.

It is important to note that violated expectations (i.e., meaning doing more or less than you expected to do) concerning the division of childcare (Biehle & Mickelson, 2012; Ruble, Fleming, Hackel, & Stangor, 1988) and housework (Ruble et al., 1988) across the transition to parenthood have been linked to mothers’ lower postpartum marital satisfaction and a decline in positive feelings toward husbands. Dew and Wilcox (2011) found that perceived unfairness mediated relations between increasingly traditional roles (i.e., wives’ increasing their own share of housework) and marital dissatisfaction among new mothers. Prior research supports the idea that couples do worse when husbands decrease their share of housework during the transition to parenthood, or performed a smaller share of childcare tasks than their wives reported expecting during their pregnancy.

The Social Context of Family Work

The division of household labor and childcare are especially salient during the transition to parenthood when the addition of an infant adds to the domestic workload. Gjerdingen and Center (2005) found that wives’ workload, including paid work, housework, and childcare, increased 64% during the transition to parenthood, whereas husbands’ increased 37%. Couples at this stage often experience increased marital conflict (Doss, Rhoades, Stanley, & Markman, 2009) and a decline in marital satisfaction (Lawrence, Rothman, Cobb, Rothman, & Bradbury, 2008), with declines in marital satisfaction linked to a more traditional division of labor following the birth of a baby (Barnes, 2015). The increased family labor coupled with the demands of paid work make the transition to parenthood a critical time to examine how the division of labor is related to relationship quality.

Social class is also related to the division of labor in families. Specifically, working-class couples are more reliant on wives' earnings than middle-class couples, and husbands in these families are more likely to view wives' work as a contribution to the family, rather than as something they do for their own fulfillment (Deutsch, 1999; Shows & Gerstel, 2009). Working-class wives are often ambivalent about their provider roles: seeing benefits to their jobs apart from a paycheck, such as increased respect and pride, but feeling guilty for not staying home with their children (Goldberg & Perry-Jenkins, 2004). This ambivalence may explain why working-class wives do a greater proportion of housework than their middle-class counterparts do (Perry-Jenkins & Folk, 1994). Research has shown that wives with college degrees decrease housework as their proportion of household income increases, whereas wives without a college degree do less housework as their proportion of household income increases up to about 50%, but increase housework when their proportion of household income surpasses 50% (Usdansky & Parker, 2011). Thus, the factors influencing the division of family labor and its consequences for close relationships are likely to be shaped by socioeconomic context.

The Current Study

The current study contributes methodologically to the literature on the division of labor and relationship quality in two ways: (a) by utilizing dyadic, longitudinal models to examine change over time in childcare and housework from the prenatal period to one-year postpartum and (b) by operationalizing the division of labor to include both housework and childcare. Moreover, much research that has examined social economic status (SES) in relation to the division of labor has either done so comparatively, or controls for SES factors such as education and income in the models. We posit that much can be learned by examining processes linking the division of labor and relationship quality within a sample of working-class families. The focus on working-class, employed new parents broadens our understanding of how social class shapes family processes.

Equity theory and exchange theory generate competing hypotheses for how perceived fairness of the division of labor is related to relationship conflict. Some previous research with middle-class samples has found that equity theory fits for women and exchange theory fits for men (Yogev & Brett, 1985); whereas other research supports an equity model for both men and women (Klumb et al., 2006). Given this background, we propose three major hypotheses. First, for household work, we hypothesize (Hypothesis 1a) that there will be positive associations between mothers’ reports of an increase in the division of housework (defined as mothers’ performing a greater share of housework after they return to their job than during pregnancy), and both mothers’ levels of relationship conflict at 1-year postpartum and change in relationship conflict (estimated rate of change) from pregnancy to 1-year postpartum. For fathers, we expect to find support for an exchange perspective, with fathers reporting less conflict when mothers share of housework increases from pregnancy to 1-year postpartum (Chong & Mickelson, 2015; Yogev & Brett, 1985).

Along with the direct associations between change in housework and conflict, we hypothesize that perceived fairness of the division of housework will mediate these associations differently for mothers and fathers. For mothers, in line with equity theory, fairness will mediate the relations between change in housework and relationship conflict in a curvilinear manner, (Hypothesis 1b) such that conflict will be lowest when mothers perceive the division as fair to both, and higher when mothers perceive the division as unfair to either spouse (Yogev & Brett, 1985). For fathers, in line with exchange theory, fairness will mediate relations between change in housework and relationship conflict in a linear way (Hypothesis 1c); fathers will report less conflict when they perceive the division as less fair to their partner (i.e. over-benefitted).

Turning to the division of childcare, there will be positive associations between violated expectations for childcare (mothers performing a greater share of childcare after returning to work than they anticipated) and mothers’ relationship conflict at 1-year postpartum, and change in relationship conflict from pregnancy to 1-year postpartum (Hypothesis 2a). We further hypothesize that fathers will report greater conflict when mothers perform a higher proportion of childcare than they expected.

As with housework, fairness is expected to mediate the associations proposed in Hypothesis 2a. For mothers, in line with equity theory, fairness will mediate the relations between violated expectations for childcare and relationship conflict in a curvilinear manner (Hypothesis 2b), such that conflict will be lowest when mothers perceive the division as fair to both, and higher when mothers perceive the division as unfair to either spouse. For fathers, in line with exchange theory, fairness will mediate the relation between mothers’ violated expectations for childcare and relationship conflict in a linear fashion (Hypothesis 2c), such that fathers report less conflict when they feel the division is fairer to them and less fair to their partner (i.e., over-benefitted).

Due to the added demands of childcare during the transition to parenthood, we pose the following hypothesis regarding the relative effects of housework and childcare: When the housework and childcare models are combined, the childcare violated expectations and fairness will account for more of the variance in spouses’ conflict than change in housework and fairness (Hypothesis 3). There is little prior literature comparing the relative effects of these two types of family labor. One study found a stronger associations for housework (Kluwer, Heesink, & van de Vliert, 2000), another found a stronger association for childcare (Pedersen et al., 2011), and still another found fairness of both related to new mothers’, but not fathers’, relationship satisfaction (Chong & Mickelson, 2015). Because childcare represents a set of new tasks being added to the family workload at this life stage, we expect it will be more salient to participants.

In addition, we controlled for fathers’ and mothers’ work hours, education, relationship status, and sex of the child, because these factors are expected to be related to expectations for the division of household labor, and thus how the division of labor is related to conflict based on prior research (Lachance-Grzela & Bouchard, 2010; Schober, 2012). We also controlled for family income because it was expected to be related to relationship conflict (Papp, Cummings, & Goeke-Morey, 2009).

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants for the present study are 108 couples who were part of a larger longitudinal investigation examining the transition to parenthood among 153 dual-earner, working-class, heterosexual couples between 1999 and 2003. Couples in their third trimester of pregnancy were recruited from prenatal classes at hospitals in the New England area. Trained graduates students described the study to expectant parents during the first 5 minutes of prenatal classes. All interested parents completed a short form with basic information on age, relationship status, household income, type of job, work hours, and intent to return to work after the baby's birth. Interested parents who fit the study criteria based on education levels were contacted and scheduled for an interview. Families received a total of $150 for their participation in all five interviews. Criteria for inclusion were: (a) both parents were employed 35 hours per week or more, (b) both partners planned to resume full-time work within 6 months of the baby's birth, (c) both partners were “working-class” as defined by educational attainment of a two-year associates degree or less, (d) both partners were expecting their first child, and (e) the couple was married or cohabiting for at least one year prior to pregnancy. Education was the primary selection factor to define working-class SES due to its ramifications for career mobility or potential for achievement (Kohn & Schooler, 1969). However, additional criteria for selection included both parents being employed in unskilled or semiskilled jobs.

Data for the present investigation were collected at five time points: third-trimester of pregnancy (Time 1), one-month postpartum (Time 2), shortly after both spouses returned to work after the birth (on average 4-months postpartum) (Time 3), six months postpartum (Time 4), and one-year postpartum (Time 5). All interviews, except at Time 4, were conducted face-to-face; Time 4 data were collected through a mailed survey. Because our aim was to examine the division of labor in dual-earner households, we limited our analyses to the 108 couples in which both partners were employed outside the home at Times 3, 4 and 5, and for whom we were not missing predictor variables. The majority (82%, n = 99) of couples were married, and the 19 (17%) who were cohabiting had been living together for at least one year prior to the pregnancy. Overall, couples had been together an average of 2.6 years (SD = 2.5, range = 0–10 years).

Participants were primarily White (96% of mothers and 92% of fathers), with a small percentage identifying as Latino (2% of mothers and 3% of fathers), Black (1% of mothers and 1% of fathers), “Other” (1% of mothers and 2% of fathers), and multiracial (3% of fathers). No participants held a college degree, but the majority had a least a high school degree (82% of mothers and 71% of fathers). As seen in Table 1, fathers were older, worked more hours per week, and had higher annual income than mothers on average. The average annual take home income for families was $57,375 (SD = $18,229, range $19,120–$106,000). It is important to note that the average income for these families places them well above the poverty line. If one member pulled out of the work force, however, the majority of these families would be living at or close to the poverty line for a family of three, which is why the majority of mothers in the sample returned to work soon after the birth. Over half of the couples (56%) had daughters.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Predictor and Outcome Variables

| Mothers (n = 98) |

Fathers (n = 90) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Min | Max | M | SD | Min | Max | |

| Age | 27.25a | 4.42 | 17.65 | 39.10 | 29.66a | 4.84 | 19.34 | 41.27 |

| Yearly Income($) | 24,666a | 11,092 | 5,200 | 58,900 | 33,347b | 10,066 | 8,920 | 70,000 |

| Work Hours at Time 3 | 36.58a | 9.35 | 10.00 | 56.00 | 47.73b | 9.25 | 15.00 | 70.00 |

| Education | 2.14a | 0.69 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 1.88a | 0.67 | 1.00 | 3.00 |

| Household Tasks | ||||||||

| Time 1 | 3.22a | 0.49 | 2.07 | 4.77 | 3.10b | 0.39 | 2.00 | 4.14 |

| Time 3 | 3.32a | 0.46 | 2.36 | 4.50 | 3.04b | 0.37 | 1.86 | 4.29 |

| Childcare tasks | ||||||||

| Time 1 | 3.45a | 0.30 | 2.93 | 4.80 | 2.69b | 0.23 | 2.00 | 3.13 |

| Time 3 | 3.62a | 0.46 | 2.93 | 5.00 | 2.56b | 0.36 | 1.53 | 4.20 |

| Fair Household | ||||||||

| Time 3 | 2.63a | 0.77 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 2.72a | 0.67 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Fair Childcare | ||||||||

| Time 3 | 2.62a | 0.60 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 2.59a | 0.53 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| HHT Δ T1 – T3 | 0.10a | 0.36 | −0.66 | 0.93 | −0.05b | 0.28 | −0.86 | 0.62 |

| CCT Δ T1 – T3 | 0.17a | 0.42 | −0.73 | 1.53 | −0.1 b | 0.35 | −1.07 | 1.20 |

| Relationship Conflict | ||||||||

| Time 1 | 3.53a | 1.12 | 1.20 | 6.80 | 3.23a | 0.99 | 1.20 | 5.40 |

| Time 2 | 3.61a | 1.33 | 1.00 | 8.20 | 2.97b | 1.04 | 1.00 | 5.20 |

| Time 3 | 3.61a | 1.37 | 1.00 | 8.60 | 3.22b | 1.18 | 1.20 | 6.40 |

| Time 4 | 3.87a | 1.29 | 1.00 | 7.40 | 3.40b | 1.34 | 1.00 | 7.80 |

| Time 5 | 3.87a | 1.32 | 1.00 | 7.40 | 3.34b | 1.22 | 1.00 | 6.20 |

Note. Sample size for MANOVA analyses reported in this table are smaller due to the inclusion of variables not used in hypothesis testing that were missing data for some participants. Means with different subscripts across a row are significantly different (p < .05). Values for household tasks and childcare tasks represent mothers’ and fathers’ reports of their own proportional contribution.

Measures

Change in division of household tasks

Contributions to household tasks were assessed at Times 1 (third trimester of pregnancy) and 3 (one month following mothers’ return to work) using mothers’ reports on the “Who does what?” scale (Atkinson & Huston, 1984). This scale includes repetitive and time-consuming “feminine” tasks such as making beds, cleaning, cooking, and laundry, as well as more gender-neutral or “masculine” tasks, such as maintaining household finances or performing outdoor work. Mothers reported their contributions to each task on a scale from 1 [usually or always my spouse (0%-20% personal contribution)] to 5 [usually or always myself (80%-100% personal contribution)]. Cronbach's alphas for mothers’ reports were at .61 and .69 at Times 1 and 3 respectively. Scale scores were created by calculating the mean score for all items, excluding items that participants indicated were not applicable. Mothers’ mean scores at Time 3 were subtracted from their mean scores at Time 1, resulting in a difference score that was positive if they completed a larger proportion of housework at Time 3 than Time 1 and negative if they performed a smaller proportion. We focused on differences in the division of labor from pregnancy to Time 3 because mothers were back at work, and there was an expectation that fathers would contribute more because mothers were now employed full-time. We refer to the change in housework variable as change in Household Tasks (ΔHHT).

Violated expectations for the division of childcare tasks

Mothers’ expected contribution to childcare tasks were assessed at Time 1, and mothers’ reports of their actual contribution to childcare tasks were assessed at Time 3 using a scale developed by Barnett and Baruch (1987). Fifteen childcare tasks, including feeding, diaper-changing, and playing with the baby, were assessed using a 5-point scale from 1 [usually or always my spouse (0%-20% personal contribution)] to 5 [usually or always myself (80%-100% personal contribution)]. Cronbach's alpha for mothers’ reports on the childcare responsibility scale were .76 (Time 1) and .84 (Time 3). Scale scores were created by calculating the mean score for all items, excluding items that participants indicated were not applicable. Mothers’ mean scores from Time 3 were subtracted from their mean scores at Time 1, resulting in a difference score that was positive if mothers completed a larger proportion of childcare at Time 3 than expected and negative if the proportion was smaller. We refer to the difference in childcare tasks variable as Change in Childcare Tasks (ΔCCT).

Perceived fairness

Fathers’ and mothers’ sense of fairness about the division of housework and child-care tasks were assessed at Time 3 using single items similar to those used to assess fairness in the National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH-I). Respondents were asked, “How do you feel about the fairness of your relationship when it comes to the division of household tasks?” and then asked about childcare tasks. They responded using a 5-point scale: 1 (very unfair to you), 2 (slightly unfair to you), 3 (fair to both you and your spouse/partner), 4 (slightly unfair to your partner), and 5 (very unfair to your partner). The scale was reverse-coded for fathers, so that a low score would always mean “very unfair to the mother” and a high score would always mean “overly fair to the mother.” High values indicate that the mother is over-benefitted and low values indicate the mother is under-benefitted. An exchange theory perspective would treat this variable in a linear fashion, such that less unfair to self should always be better. In contrast, equity theory would treat this variable in a curvilinear fashion, using a squared transformation, such that fair to both would always be better than unfair to either self or partner. Thus we calculated a squared term for fairness so that possible curvilinear relations between fairness and conflict, in support of equity theory, could be tested; we called this variable “Fairness-sq.” Fairness was left in its original linear form in order to test an exchange theory hypothesis; we called this variable “Fairness-ln.” The distribution of fairness of household and childcare tasks for fathers and mothers is presented in Table 1.

Relationship conflict

Relationship conflict was measured using the Conflict-Negativity subscale of Braiker and Kelley's (1979) Personal Relationship Scale (PRS). The Conflict-Negativity subscale used five items to assess negativity in the relationship with items such as, “How often did you and your partner argue with one another?” Responses ranged from 1 (not at all or very infrequently) to 9 (very much or very frequently). Fathers and mothers completed the PRS at all five time points. To address our research hypotheses, we were interested in change in the division of housework and childcare from pregnancy to Time 3 as predictors of the trajectory of conflict across Times 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, and levels of conflict at Time 5. We chose to examine the level of conflict at Time 5 because this procedure allows for a stronger causal argument for our mediation model, with a predictor (housework and childcare from Time 1 to Time 3) preceding the mediator (Fairness at Time 3) preceding the dependent variable. Cronbach's alpha for the Conflict subscale for all spouses ranged from .68 to .80 across all time points.

Control variables

Work hours were assessed at Time 3. Although all participants reported intentions to return to work full-time when interviewed in the third trimester, postpartum work hours varied, with some mothers returning part-time and most returning full-time. Household income at Time 3, after mothers returned to work, was measured using mothers’ and fathers’ reports of their annual personal earnings. Spouses reported their highest level of education at Time 1 using an ordinal scale of 0 (less than high school), 1 (high school graduate/GED), 2 (some college/vocational school), and 3 (Associates degree). A dummy coded variable was used to represent relationship status with values of 0 (cohabiting) and 1 (married). Sex of the baby was coded 0 (boy) or 1 (girl).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Means and standard deviations for predictors and outcomes, as well as gender differences in these variables, are presented in Table 1. MANOVA analyses revealed that fathers compared to mothers were significantly older, had less education, earned more money, and worked more hours outside the home. Both spouses reported that mothers performed a higher proportion of housework and childcare tasks than did fathers at both time points. Fathers and mothers did not differ in how fair they perceived the division of housework and childcare to be, with both reporting a mean score in between “fair to both” and “slightly unfair to mother.” Fathers reported a mean decrease in their share of housework from pregnancy to return to work, whereas mothers reported an increase (a pattern which also held for childcare), with mothers performing more childcare than expected and with fathers reporting a smaller share than expected. Mothers also reported significantly higher levels of conflict than did fathers at Times 2–5, whereas the difference at Time 1 was not significant (p = .056).

Multilevel linear modeling (MLM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) was used to fit the models and test hypotheses. Dyadic longitudinal MLM provides a robust method for modeling individual change in relationship conflict across the transition to parenthood. MLM also allows partners’ outcomes to be linked, thus accommodating two sources of dependency in longitudinal couple data: similarity within the couple and dependency from repeated measures within the individual. Mediation hypotheses were tested following Baron and Kenny (1986). To produce a parsimonious final model, non-significant predictors were trimmed from one equation at a time, beginning with the quadratic, then linear, and finally the intercept model.

Control variables were first tested by adding them to each equation. Non-significant variables were then trimmed from one equation at a time, beginning with the quadratic, then linear, and finally intercept Level-2 equations. Significant control variables (household income, marital status, and fathers’ education) were included in all models. We chose this approach to include control variables rather than keep the non-significant ones in all equations for the sake of parsimony and to preserve power. Child's sex, mothers’ education, mothers’ work hours, and fathers’ work hours were not significant predictors and were omitted from the analyses.

We fit a baseline growth model to the conflict data for both spouses, which estimates the average level of conflict at 1-year postpartum (due to coding of time where 1-year postpartum was set to zero) and the average change in conflict for both partners. The baseline model that best fit the data included linear and quadratic change for mothers, and linear change only for fathers. On average, mothers showed an increase in conflict across the five time points, which increased at a slower rate over time. Fathers showed a linear increase in conflict across all time points. For mothers, there was significant variability around the average level (level variance = 1.18, χ 2 = 385.44, p < .001). Variability around the average rates of linear and quadratic change did not reach significance (linear change variance = 0.008, χ 2 = 125.91, p = .062; quadratic change variance = 0.00006, χ 2 = 126.81, p = .056). Although there was no significant variability in mothers’ linear and quadratic change trajectory, tests of variance are less powerful than those for fixed effects in dyadic MLM, and we were interested in even small changes in parents’ marital conflict (Maas & Hox, 2005). For fathers, there was significant variability around the average level and average change (level variance = 1.16 χ2 = 426.00, p < .001; linear change variance = 0.001, χ 2 = 127.64, p = .050).

Hypothesis Testing

Household tasks and relationship conflict

To test Hypotheses 1a, MLM growth models were fit to assess the strength of ΔHHT in predicting levels of relationship conflict at 1-year postpartum, as well as change in conflict across Times 1–5 for both spouses (Table 2). Equations for these analyses can be found in Table 2. As shown in Model 1 of Table 2, there was no direct effect of ΔHHT on mothers’ levels or change in conflict. Mothers’ increase in household tasks did predict higher levels of conflict for fathers at Time 5, but was unrelated to change in fathers’ conflict, lending partial support to Hypothesis 1a that as mothers’ housework increased fathers would report more conflict.

Table 2.

Multilevel Growth Models Predicting Relationship Conflict from Time 1 to Time 5 from Household Tasks

| Model 1: HHT Main Effect |

Model 2: HHT Fairness Mediation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | |

| Mothers’ Level of Conflict T5 | ||||

| Intercept | 3.923** | 0.116 | 3.733** | 0.136 |

| Household Income | −0.022** | 0.006 | −0.019** | 0.006 |

| Fathers’ Education | 0.414** | 0.118 | 0.368** | 0.120 |

| Δ HHT T1-T3 | 0.428 | 0.314 | 0.375 | 0.303 |

| HHT Fairness T32 | 0.334* | 0.137 | ||

| Mothers’ Δ Conflict | ||||

| Intercept | 0.005 | 0.021 | −0.005 | 0.021 |

| Household Income | 0.003** | 0.001 | 0.003** | 0.001 |

| Δ HHT T1-T3 | −0.009 | 0.023 | −0.011 | 0.022 |

| HHT Fairness T32 | 0.020 | 0.011 | ||

| Mothers’ Δ2 Conflict | ||||

| Intercept | −0.002 | 0.002 | −0.002 | 0.002 |

| Household Income | <0.001** | <0.001 | <0.001** | <0.001 |

| Fathers’ Level of Conflict T5 | ||||

| Intercept | 3.841** | 0.270 | 3.697** | 0.278 |

| Household Income | −0.008 | 0.005 | −0.008 | 0.005 |

| Married | −0.553 | 0.289 | −0.514* | 0.287 |

| Δ HHT T1-T3 | 0.650* | 0.317 | 0.627** | 0.311 |

| HHT Fairness T32 | 0.259 | 0.140 | ||

| Fathers’ Δ Conflict | ||||

| Intercept | 0.056** | 0.019 | 0.052* | 0.019 |

| Married | −0.038 | 0.020 | −0.037 | 0.020 |

| Δ HHT T1-T3 | −0.027 | 0.021 | −0.030 | 0.021 |

| HHT Fairness T32 | 0.028** | 0.010 | ||

| Deviance (# parameters) | 2791.96 (32) | 2778.45 (36) | ||

Note. N = 108 couples. HHT = household tasks. Relationship status was coded as cohabiting = 0, married = 1. Household income measured in thousands. Income, father education, and fairness were centered at the mean. Equations for Model 2 are as follows:

Level-1 Model: CONFLICTij = β1j*(WIFEij) + β2j*(HUSBANDij) + β3j*(W12TIMEij) + β4j*(H12TIMEij) + β5j*(W12TSQij) + rij

Level-2 Model: β1j = γ10 + γ11*(INCOMEj) + γ12*(HEDUCj) + γ13*(HHDIF31j) + γ14*(W3FRHHSQj) + u1j

β2j = γ20 + γ21*(INCOMEj) + γ22*(MARRIEDj) + γ23*(HHDIF31j) + γ24*(H3FRHHSQj) + u2j

β3j = γ30 + γ31*(INCOMEj) + γ32*(HHDIF31j) + γ33*(W3FRHHSQj) + u3j

β4j = γ40 + γ41*(MARRIEDj) + γ42*(HHDIF31j) + γ43*(H3FRHHSQj) + u4j

β5j = γ50 + γ51*(INCOMEj) + u5j

p < .05.

p < .01.

Hypotheses 1b tested equity versus exchange theory by examining whether fairness—measured as the squared term (fairness-sq), in order to capture the curvilinear relationship, versus the linear term (fairness-ln)—mediated the relationship between ΔHHT and levels of conflict one year out (Model 2, Table 2). Support emerged for the equity model for mothers, with partial support for fathers. Fairness-sq was positively related to mothers’ levels of conflict, but was not significantly related to mothers’ change in conflict. Results revealed that adding the fairness-sq mediator was a significant improvement in model fit, χ2(4) = 13.51, p = .009, and although ΔHHT was significantly negatively related to fairness-sq (p = .031), a test of the indirect effect did not reach significance (Goodman's z = −1.71, se = 0.42, p = .087). Fairness, measured either linearly (fairness-ln) or as a squared term (fairness-sq), did not significantly mediate the relationship between ΔHHT and change in mothers’ conflict. These results lend partial support to Hypothesis 1b showing that, for mothers, increases in housework were related to more conflict one-year out when they perceived that the division of housework was unfair to either spouse—an equity view.

For fathers, (Hypothesis 1c), exchange theory was not supported for either levels of or changes in conflict, as fairness-ln was unrelated. An equity model received partial support. Fairness-sq (equity) was significantly related to change in conflict; however, the mediated path was not significant, and ΔHHT was not significantly related to husbands’ fairness-sq. In addition, ΔHHT retained an independent, positive effect on levels of conflict in the model including fairness.

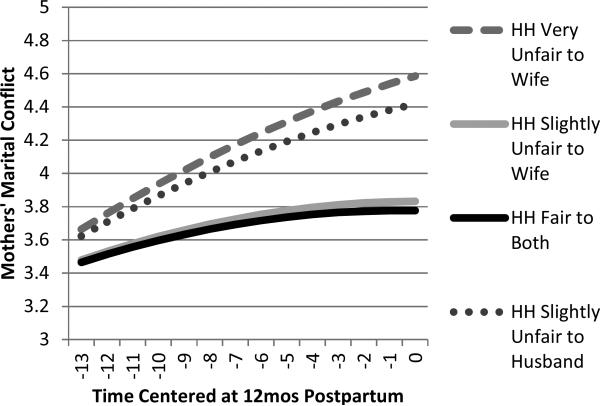

Overall, equity theory was supported by these results for both mothers and fathers, but the connections between the division of labor and perceptions of equity differed for mothers and fathers. Specifically, for mothers, a greater increase in household tasks was related to perceptions of unfairness following the return to work, which was, in turn, related to greater conflict at one year postpartum. Mothers’ perception of the division of housework as fair to each partner (meaning no one was over- or under- benefitted) was related to lower levels of conflict at one-year postpartum. As seen in Figure 1, mothers reported the lowest levels of conflict when they perceived the division of housework as fair to both (solid black line in Figure 1), whereas conflict was higher if housework was perceived as unfair to either spouse (dotted and dashed lines in Figure 2). Though ΔHHT was related to mothers’ fairness-sq, and fairness-sq was significantly related to mothers’ levels of conflict, the indirect path was not significant.

Figure 1.

Fairness of housework and mothers’ conflict

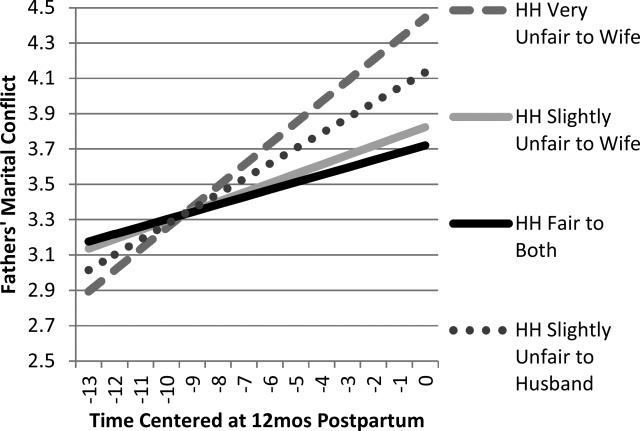

Figure 2.

Fairness of housework and fathers’ conflict

For fathers, equity theory was supported in that fathers reported a smaller increase in conflict when the division of housework was perceived as fair (meaning no spouse was over- or under-benefitted). As seen in Figure 2, fathers reported the slowest increase in conflict when they perceived the division of housework as fair to both (solid black line in Figure 2), whereas conflict increased faster if housework was perceived as unfair to either spouse (dotted and dashed lines in Figure 2). Perceptions of fairness did not mediate relations between ΔHHT and relationship conflict. For fathers, ΔHHT was unrelated to perceived fairness of housework, suggesting that they consider other factors in assessing the fairness of the division of housework.

Childcare tasks and relationship conflict

The hypotheses for childcare, Hypotheses 2a–c, were tested using the same steps as the housework models (see Table 3). As shown in Model 1 of Table 3, ΔCCT was not related to mothers’ level of conflict, and the positive association between ΔCCT and mothers’ linear change in conflict was not significant (p = .064). Although associations were in the hypothesized direction, they did not reach significance, thus Hypothesis 2a was not supported for mothers. No childcare predictors were significantly related to fathers’ conflict, so they were omitted from the final models. Given that mediation can be present without a direct association between the independent and dependent variables, we proceeded to test Hypothesis 2b for mothers due to our hypothesis that CCT variables would be a stronger predictor than HHT for wives and that fairness would matter more than the division itself.

Table 3.

Multilevel Growth Models Predicting Relationship Conflict from Time 1 to Time 5 from Childcare

| Model 1: CCT Main Effect |

Model 2: CCT Fairness Mediation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | |

| Mothers’ Level of Conflict T5 | ||||

| Intercept | 3.896** | 0.121 | 3.952** | 0.118 |

| Household Income | −0.022** | 0.006 | −0.019** | 0.006 |

| Fathers’ Education | 0.414** | 0.119 | 0.455** | 0.117 |

| Δ CCT T1-T3 | 0.360 | 0.248 | 0.071 | 0.256 |

| CCT Fairness T3 | −0.565** | 0.177 | ||

| Mothers’ Δ Conflict | ||||

| Intercept | −0.002 | 0.021 | 0.001 | 0.021 |

| Household Income | 0.003** | 0.001 | 0.003** | 0.001 |

| Δ CCT T1-T3 | 0.036 | 0.019 | 0.024 | 0.020 |

| CCT Fairness T3 | −0.024 | 0.014 | ||

| Mothers’ Δ2 Conflict | ||||

| Intercept | −0.002 | 0.002 | −0.002 | 0.002 |

| Household Income | <0.001** | <0.001 | <0.001** | <0.001 |

| Fathers’ Level of Conflict T5 | ||||

| Intercept | 3.899** | 0.269 | 3.858** | 0.270 |

| Household Income | −0.011* | 0.005 | −0.011* | 0.005 |

| Married | −0.545 | 0.291 | −0.496 | 0.293 |

| Fathers’ Δ Conflict | ||||

| Intercept | 0.052** | 0.019 | 0.051** | 0.019 |

| Married | −0.037 | 0.020 | −0.035 | 0.020 |

| Deviance (# parameters) | 2807.35 (30) | 2798.01 (32) | ||

Note. N = 108 couples. CCT = childcare tasks. Relationship status was coded as cohabiting = 0, married = 1. Household income measured in thousands. Income, father education, and fairness were centered at the mean. Equations for Model 2 are as follows:

Level-1 Model

CONFLICTij = β1j*(WIFEij) + β2j*(HUSBANDij) + β3j*(W12TIMEij) + β4j*(H12TIMEij) + β5j*(W12TSQlj) + rij

Level-2 Model

β1j = γ10 + γ11*(INCOMEj) + γ12*(HEDUCj) + γ13*(CCDIF31j) + γ14*(W3FRCCj) + u1j

β2j = γ20 + γ21*(INCOMEj) + γ22*(MARRIEDj) + u2j

β3j = γ30 + γ31*(INCOMEj) + γ32*(CCDIF31j) + γ33*(W3FRCCj) + u3j

β4j = γ40 + γ41*(MARRIEDj) + u4j

β5j = γ50 + γ51*(INCOMEj) + u5j

p < .05.

p < .01.

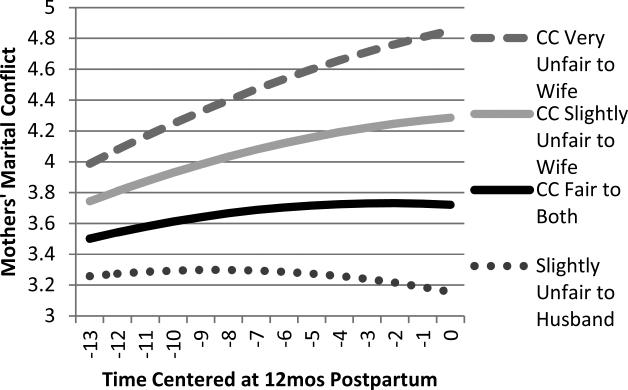

Hypothesis 2b tests equity theory by examining whether fairness-sq mediated the relationship between ΔCCT and levels and change in relationship conflict. Fairness-sq was not a significant predictor for either levels or change in conflict for either spouse, thus results did not support Hypothesis 2b and equity theory. The exchange model, however, was supported for mothers and childcare. Contrary to our hypothesis, for mothers, fairness-ln was significantly negatively related to mothers’ levels of conflict. Associations with mothers’ change in conflict did not reach significance (p = .084). As fairness in the division of childcare increased (i.e. women became less under-benefitted) levels of mothers’ conflict 1 year postnatal were lower, as seen in Figure 3. In support of mediation, adding the fairness-ln term to mothers’ equations resulted in a significant improvement in model fit, χ2(2) = 9.34, p = .009, and the indirect effect of change in childcare on levels of conflict as mediated by fairness-ln was significant (Goodman's z = 2.67, se = 0.131, p = .008). Turning to the same analyses for fathers (Hypothesis 2c), neither exchange nor equity theory were supported for fathers, as neither fairness-ln nor fairness-sq was related to levels or change in fathers’ conflict. Thus, childcare predictors were omitted from fathers’ final models.

Figure 3.

Fairness of childcare and mothers’ conflict

Overall, for childcare, exchange theory, not equity theory, was supported for mothers’ levels and change in conflict. When mothers’ perceived the division of childcare as unfair to them (i.e., mothers were under benefited) because they performed a greater share of childcare than they expected, their perceived unfairness was related to higher levels of relationship conflict at 1-year postpartum. As seen in Figure 3, mothers reported the highest conflict when they perceived the division of childcare as very unfair to them (dashed line), and the lowest levels of conflict when they perceived the division as slightly unfair to fathers (dotted line). For fathers, no childcare predictors were related to levels or change in conflict.

Relative effects of housework and childcare

To test Hypothesis 3, which focuses on the relative effects of housework and childcare on conflict, the final predictors from the housework and fairness model and those from the childcare and fairness model were combined in one model. The difference in the housework only model (see Model 2, Table 2) and the combined model was tested to determine how much additional variance was explained by adding childcare predictors from the final childcare model. We used the same process to compare the additional variance explained by housework predictors, but we compared the combined model to the final childcare model (see Model 2, Table 3). For mothers’ levels of conflict, adding childcare accounted for 11.3% of the variance in conflict not accounted for by the housework model, whereas adding housework only accounted for 8.5% of the variance not accounted for by childcare. These findings suggest that childcare is the more important predictor for mothers’ levels of conflict. For mothers’ linear change in conflict, however, adding housework explained more remaining variance (12.7%) than adding childcare (8.0%), suggesting that housework predictors mattered more for mothers’ change in conflict. For fathers, no childcare predictors were significant, but housework predictors explained 7.5% of remaining variance in levels of conflict, and 13.8% of remaining variance in change in conflict, above and beyond control variables. In the final model the only fixed effect that remained significant for mothers was the negative association of fairness-ln of childcare and levels of conflict. For fathers, an increase in mothers’ share of housework remained positively related to levels of conflict, and fairness-sq of housework remained positively related to the rate of change in conflict. Housework was clearly more important for fathers’ conflict than was childcare.

Discussion

In the present study, we tested hypotheses derived from equity and exchange theories as possible explanations for how changes in the division of housework and childcare across the transition to parenthood, along with perceptions of fairness regarding these tasks, were related to relationship conflict for new parents. We examined these processes in an understudied sample of working-class families in which both parents were employed full-time and experienced the birth of their first child along with an early return to paid employment.

In support of equity theory, we found that when mothers reported the division of housework to be fair to both spouses, relationship conflict one year after birth was lower. Our findings support previous research (Yogev & Brett, 1985) showing a curvilinear relationship between fairness and relationship conflict, such that mothers fared best when neither spouse was over- or under-benefitted in terms of housework and their contributions were perceived as fair. Chong and Mickelson (2015) found that, for mothers, greater fairness to self in housework (exchange perspective) predicted greater relationship satisfaction; however, they did not test an equity perspective (i.e., fairness assessed in curvilinear fashion) in their models.

Fathers reported a slower increase in conflict when mothers reported less of an increase in housework from pregnancy to the postpartum return to work. In addition, when fathers perceived the division of housework as fair to both spouses, they reported the slowest increase in conflict. In support of equity theory, fathers reported less of an increase in conflict when they felt neither under-benefitted nor very over-benefitted—a finding contrary to our original exchange hypothesis. We also found that, contrary to our hypothesis, fairness did not mediate the link between change in the division of housework and change in conflict. In short, change in the division of housework was unrelated to fathers’ assessments of fairness regarding the division of housework. This finding is in line with those of Lavee and Katz (2002), and it suggests that fathers and mothers may consider different factors when evaluating the fairness of the division of labor. Although we would expect spouses’ work hours or relative earnings to explain some amount of the fairness of family labor, these variables were not significant in our models.

Our findings regarding the division of childcare also ran counter to our hypotheses. Exchange theory, not equity, better explained the relationship between mothers’ perceptions of fairness of childcare and relationship conflict. Mothers who performed a greater share of childcare than expected upon their return to work perceived the division as unfair to themselves. Perceptions of unfairness resulted in higher levels of relationship conflict at 1-year postpartum. For fathers, neither the division of childcare nor perceived fairness of that division were related to fathers’ relationship conflict. Although this finding for the division of childcare and fathers’ conflict contrasts with some prior research (Schober, 2012,) it does fit with other previous research that has found childcare and perceptions of its fairness to be unrelated to fathers’ relationship satisfaction (Chong & Mickelson, 2015).

When comparing the relative effects of housework and childcare on conflict, childcare was a stronger predictor of mothers’ conflict than was housework, whereas housework explained more variance in fathers’ conflict. These findings are in line with Pederson and colleagues’ (2011) findings, but in contrast with those of Chong and Mickelson (2015) who did not find differential effects of housework versus childcare. Overall, our results suggest that couples do best when mothers’ share of family labor does not increase from pregnancy to her return to work, as well as when fathers and mothers perceive the division of housework as fair to both partners. This conclusion is in line with research on violated expectations (Bodi, Mikula, & Riederer, 2010) and with links between role-traditionalization and declines in relationship satisfaction (Dew & Wilcox, 2011), and it supports the idea that couples do worse when fathers perform less family labor than mothers expect, or less than they did prior to becoming parents. It is also important to note that levels and trajectories of conflict for fathers and mothers looked very similar when they reported the division of housework as “Fair to Both” and “Slightly Unfair to Mothers,” which were the most common responses. This suggests that couples may expect and accept that mothers will be under-benefitted to some extent, and it is only when that unfairness falls outside this “normal” range that its effects are more dramatic.

Practice Implications

Researchers investigating the division of labor, as well as practitioners and therapists working with clients during the transition to parenthood, may wish to consider how social class may change how the division of labor influences marital relationships. Of note, in our study, mothers who felt housework was fair to both parents and those who felt it was slightly unfair to them reported less conflict, suggesting that working-class mothers may hold some expectations that housework is their responsibility, and thus see a modest inequity as acceptable, but not a large inequity.

For working-class fathers, researchers and professionals working with new parents may find that fathers desire more equitable arrangements than might be expected. Our findings supporting equity theory for fathers and housework suggest fathers may have perceived mothers’ employment as a necessary contribution to the fathers’ domain of providing, and therefore felt it only fair that they also contribute to the mothers’ domain of family labor. The fact that Chong and Mickelson's (2015) study, with a more middle class sample, found no effects of fairness on fathers’ relationship satisfaction lends support to the idea that social class factors may be playing a role in shaping the significant results found in our data. Professionals working with this population may wish to explore what meaning is made of the division of paid and unpaid labor in these families before making assumptions.

In terms of the gender differences found in our study, therapists and prenatal educators working with expectant or new mothers and fathers may want to help couples explore what meaning they make of housework and childcare. For example, a possible explanation for our results showing fathers’ reports of conflict were related to housework, but not childcare, may be that fathers are less likely to view requests for help with childcare as nagging than requests for help with housework, making fathers more likely to argue over housework than childcare. On the other hand, fathers’ involvement in childcare seems to mean more for mothers’ relationship conflict than does housework, so couples may not be considering the same types of work when trying to address relationship conflict. Practitioners would do well to explore with what types of labor parents are concerned when conflict over family labor occurs.

Our finding that childcare mattered more for mothers’ conflict than housework has implications for research, clinical practice, and policy. Although past research suggests that housework is more aversive than childcare (Poortman & van der Lippe, 2009), it may be that childcare is more salient to mothers than housework during the childcare intensive first year of parenthood. Housework may become more important relative to childcare after mothers have adapted to parenthood or when children are older and childcare demands diminish. Researchers exploring the division of labor among parents of children with a broader age range may miss important differences in these associations depending on the age of children. Therapists working with parents should attend to gender differences in how housework and childcare affect parents’ evaluations of their relationships as well as how these differences may vary across the life course.

Another explanation for the salience of childcare over housework may be that housework is more flexible in the timing, quality, or required time (e.g., in a time crunch parents can get fast-food) than childcare (e.g., a diapers must be changed right away). Fathers’ involvement with infant care may be more crucial and affect mothers more directly such as in terms of sleep, a primary concern after returning to work. Working-class mothers, who cannot afford outside help, may find fathers’ involvement in childcare even more crucial than mothers with more resources, which therapists and prenatal educators should consider when working with this population. Moreover, public policymakers may consider the social and economic cost of the harm done to marriages when weighing the costs and benefits of providing supports for new parents, such as subsidized childcare and parental leave.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The current study has several limitations. The select sample of working-class, dual-earner, primarily White, first-time parents limits the generalizability of these findings. In addition, our data were collected at the turn of the 21st century and are about 15 years old. Changes in the instability of low-wage work and the dramatic gap in economic inequality that has emerged over the past decade have increased stress to the lives of low-wage families, often requiring parents to work more hours to make ends meet. These changes suggest that low-wage, new parents likely face greater challenges in balancing work and family tasks, increasing stress on their relationships. New research is needed to provide insight into how working-class families in the current economic climate are managing family labor and employment and how this shared workload relates to marital relationships.

The measure of fairness posed another limitation. Fairness was assessed using one question for each type of labor, with a scale that placed “fair to the father” and “fair to the mother” at opposite ends. This measure assumes a perfect inverse relation between spouses’ levels of fairness, which may not be the case. It is impossible to know what factors participants used to assess the level of fairness, or whether there were participants who felt the division of labor was unfair to both spouses. Participants only used a limited range of the scale, with very few participants indicating that the division of either type of labor was unfair to the father. Because very few mothers reported that they were “over-benefitted” when it came to the division of childcare, our data could not adequately test an equity model becasue there was not enough variability in the fairness of childcare to detect a curvilinear relation between fairness and conflict for mothers.

Although we have put forth hypotheses as to why these differences between housework and childcare were found, these hypotheses cannot be tested with our data. Future research should explore the meaning that fathers and mothers make of each others’ involvement in childcare and housework. Qualitative research is needed in this area because quantitative studies cannot adequately capture why childcare and housework might have these differing associations with marital conflict.

Conclusion

Results from our study highlight the value of looking at both housework and childcare because they appear to have different meanings for spouses. The question of how gendered behaviors around household work and childcare are linked to relationship conflict for men and women highlights the complexity of the intersections of both gender and class as they shape family experiences. That these differences were found within the context of working-class, dual-earner families at the same life-stage points to the insights that can emerge from within group analyses that highlight the unique and varied experiences of families in different social contexts. Differences in the effects of childcare and housework on relationship conflict are not only due to the presence of children, but also to these children's age and unique needs. The fact that predictors of conflict differed for mothers and fathers is important and points to important topics for interventions with low-income, first-time parents. Working-class employed parents of infants have a large workload to share, and both researchers and professionals working with this population could better serve these families by trying to understand the meaning mothers and fathers make of different types of labor and how parents can successfully share this workload and have positive outcomes for their relationships.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health and was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the authors’ institution. All participants were over age 18, and informed consent practices were followed and approved by IRB.

Our research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to Maureen Perry-Jenkins (R01-MH56777). We gratefully acknowledge Aya Ghunney, Hillary Paul Halpern, Holly Laws, Elizabeth Harvey, and Naomi Gerstel for their assistance on this project.

Footnotes

None of the authors have a financial or other conflict of interest related to this project.

References

- Atkinson J, Huston TL. Sex role orientation and division of labor early in marriage. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46:330–345. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.46.2.330. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett RC, Baruch GK. Determinants of fathers’ participation in family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1987;49(1):29–40. doi:10.2307/352667. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes MW. Gender differentiation in paid and unpaid work during the transition to parenthood. Sociology Compass. 2015;10:348–364. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Milkie MA, Sayer LC, Robinson JP. Is anyone doing the housework?: Trends in the gender division of household labor. Social Forces. 2000;79:191–228. doi:10.2307/2675569. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Sayer LC, Milkie MA, Robinson JP. Housework: Who did, does or will do it, and how much does it matter? Social Forces. 2012;91(1):55–63. doi: 10.1093/sf/sos120. doi:10.1093/sf/sos120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biehle SN, Mickelson KD. First-time parents’ expectations about the division of childcare and play. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26(1):36–45. doi: 10.1037/a0026608. doi:10.1037/a0026608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodi O, Mikula G, Riederer B. Long-term effects between perceived justice in the division of domestic work and women's relationship satisfaction. Social Psychology. 2010;41(2):57–65. doi:10.1027/1864-9335/a000009. [Google Scholar]

- Braiker HB, Kelley HH. Conflict in the development of close relationships. In: Burgess RL, Huston TL, editors. Social exchange in developing relationships. Academic; New York, NY: 1979. pp. 135–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The bioecological model of human development. In: Lerner RM, Damon W, editors. Theoretical models of human development. Vol. 1. Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics Employment characteristics of families - 2014. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/famee.nr0.htm.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics Employment characteristics of families in 2000. 2001 Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/history/famee_04192001.txt.

- Chong A, Mickelson KD. Perceived fairness and relationship satisfaction during the transition to parenthood: The mediating role of spousal support. Journal of Family Issues. 2015;37(1):3–28. doi:10.1177.0192513X13516764. [Google Scholar]

- Claffey ST, Mickelson KD. Division of household labor and distress: The role of perceived fairness for employed mothers. Sex Roles. 2008;60(11-12):819–831. [Google Scholar]

- Craig L. Does father care man fathers share? A comparison of how mothers and fathers in intact families spend time with children. Gender and Society. 2006;20(2):259–281. doi: 10.1177/0891243285212. [Google Scholar]

- Davis SN, Greenstein TN. Why study housework: Cleaning as window into power in couples. Journal of Family Theory and Review. 2013;5:63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch F. Halving it all: How equally shared parenting works. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch FM, Lussier JB, Servis LJ. Husbands at home: Predictors of paternal participation in childcare and housework. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65(6):1154–1166. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.6.1154. [Google Scholar]

- Dew J, Wilcox WB. If Momma ain't happy: Explaining declines in marital satisfaction among new mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73:1–12. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00782.x. [Google Scholar]

- Doss BD, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. The effect of the transition to parenthood on relationship quality: An eight-year prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:601–619. doi: 10.1037/a0013969. doi:10.1037/a0013969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberg MF, Gearing-Small M, Hunter MA, Small BJ. Childcare task division and shared parenting attitudes in dual-earner families with young children. Family Relations. 2001;50(2):143–153. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2001.00143.x. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson RJ. Why emotion work matters: Sex, gender, and the division of household labor. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:337–351. doi: 10.1111/j.00222445.2005.00120. [Google Scholar]

- Ferree MM. The view from below: Women's employment and gender equality in working-class families. In: Hess BB, Sussman MB, editors. Women and the family: Two decades of change. Haworth Press; New York, NY: 1984. pp. 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Frisco ML, Williams K. Perceived housework equity, marital happiness, and divorce in dual-earner households. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24(1):51–73. doi: 10.1177/0192513X02238520. [Google Scholar]

- Gjerdingen DK, Center BA. First-time parents’ postpartum changes in employment, childcare, and housework responsibilities. Social Science Research. 2005;34(1):103–116. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2003.11.005. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg AE, Perry-Jenkins M. Division of labor and working-class women's well-being across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:225–236. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.225. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.18.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote NK, Naylor KE, Clark MS. Perceiving the division of family work to be unfair: Do social comparisons, enjoyment and competence matter? Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16(4):510–522. doi:10.1037.0893-3200.16.4.510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii-Kuntz M, Coltrane S. Predicting the sharing of household labor: Are parenting and housework distinct? Sociological Perspectives. 1992;35:629–647. doi: 10.1177/019251392013002006. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M, Monden CWS. The division of labor and depressive symptoms at the couple level: Effects of equity or specialization. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2011;29(3):358–374. doi:10.1177/0265407511431182. [Google Scholar]

- Klumb P, Hoppmann C, Staats M. Division of labor in German dual-earner families: Testing equity theoretical hypotheses. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:870–882. doi:10.1111/j.1741- 3737.2006.00301.x. [Google Scholar]

- Kluwer ES, Heesink JAM, van de Vliert E. Marital conflict about the division of household labor and paid work. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1996;58:958–969. doi:10.2307/353983. [Google Scholar]

- Kluwer ES, Heesink JAM, van de Vliert E. The division of labor in close relationships: An asymmetrical conflict issue. Personal Relationships. 2000;7:263–282. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2000.tb00016.x. [Google Scholar]

- Kluwer ES, Heesink JAM, van de Vliert E. The division of labor across the transition to parenthood: A justice perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:930–943. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00930.x. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn ML, Schooler C. Class, occupation and orientation. American Sociological Review. 1969;34(5):659–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachance-Grzela M, Bouchard G. Why do women do the lion's share of housework? A decade of research. Sex Roles. 2010;63(11-12):767–780. doi:10.1007/s11199-010-9797-z. [Google Scholar]

- Lavee Y, Katz R. Division of labor, perceived fairness, and marital quality: The effect of gender ideology. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64(1):27–39. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00027.x. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Rothman AD, Cobb RJ, Rothman MT, Bradbury TN. Marital satisfaction across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(1):41–50. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.41. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas C, Hox J. Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling. Methodology. 2005;1(3):86–92. doi:10.1027/1614-1881.1.3.86. [Google Scholar]

- Mannino CA, Deutsch FM. Changing the division of household labor: A negotiated process between partners. Sex Roles. 2007;56:309–324. doi:10.1007/s11199-006-9181-1. [Google Scholar]

- Meier JA, McNaughton-Cassill M, Lynch M. The management of household and childcare tasks and relationship satisfaction in dual-earner families. Marriage & Family Review. 2006;40(2 & 3):61–88. doi:10.1300/J002v40n02_04. [Google Scholar]

- Meteyer K, Perry-Jenkins M. Father involvement among working-class dual-earner couples. Fathering. 2010;8(3):379–403. doi:10.3149/fth.0803.379. [Google Scholar]

- Papp LM, Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC. For richer, for poorer: Money as a topic of marital conflict in the home. Family Relations. 2009;58(1):91–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00537.x. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen D, Minnotte KL, Mannon S, Kiger G. Exploring the relationship between types of family work and marital well-being. Sociological Spectrum. 2011;31(3):288–315. doi:10.1080/02732173.2011.557038. [Google Scholar]

- Perry-Jenkins M, Folk K. Class, couples, and conflict: Effects of the division of labor on assessments of marriage in dual-earner families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1994;56(1):165–180. doi:10.2307/352711. [Google Scholar]

- Perry-Jenkins M, Newkirk K, Ghunney AK. Family work through time and space: An ecological perspective. Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2013;5:105–123. doi:10.1111/jftr.12011. [Google Scholar]

- Poortman A-R, van der Lippe T. Attitudes toward housework and childcare and the gendered division of labor. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:526–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00617.x. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Multilevel growth models. 2nd ed. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Fleming AS, Hackel LS, Stangor C. Changes in the marital relationship during the transition to first time motherhood: Effects of violated expectations concerning division of household labor. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;55(1):78–87. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.55.1.78. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.55.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schober PS. Paternal childcare and relationship quality: A longitudinal analysis of reciprocal associations. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74(2):281–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00955.x. [Google Scholar]

- Shows C, Gerstel N. Fathering, class, and gender: A comparison of physicians and emergency medical technicians. Gender & Society. 2009;23(2):161–87. doi: 10.1177/0891243209333872. [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S. Equity and social exchange in dating couples: Associations with satisfaction, commitment, and stability. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:599–613. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens D, Kiger G, Mannon S. Domestic labor and marital satisfaction: How much or how satisfied? Marriage & Family Review. 2005;37(4):49–67. doi: 10.1300/J002v37n04_04. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens D, Kiger G, Riley PJ. Working hard and hardly working: Domestic labor and marital satisfaction among dual earner couples. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:514–526. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00514.x. [Google Scholar]

- Usdansky ML, Parker WM. How money matters: College, motherhood, earnings, and wives’ housework. Journal of Family Issues. 2011;32(11):1449–1473. doi: 10.1177/0192513X114029. [Google Scholar]

- Yogev S, Brett J. Perceptions of the division of housework and childcare and marital satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1985;47(3):609–618. [Google Scholar]