Abstract

Introduction

Knowledge about macro- and micro-structural characteristics may improve in vivo estimation of the quality and quantity of regenerated bone tissue. For this reason, micro-CT imaging has been applied to evaluate alveolar bone remodelling, alterations of periodontal ligament thickness and cortical and trabecular bone changes in rodent jaw bones. In this paper, we provide a systematic review on the available micro-CT literature on jaw bone micro-architecture.

Methodology

A detailed search through the PubMed database was performed. Articles published up to December 2013 and related to maxilla, mandible and condyle with quantitatively analysed bone micro-architectural parameters were considered eligible for inclusion. Two reviewers assessed the search results according to inclusion criteria designed to identify animal studies quantifying the bone micro-architecture of the jaw rodent bones in physiological or drug-induced disease status, or in response to interventions such as mechanical loading, hormonal treatment and other metabolic alterations. Finally, the reporting quality of the included publications was evaluated using the tailored ARRIVE guidelines outlined by Vignoletti and Abrahamsson (2012).

Results

Database search, additional manual searching and assessment of the inclusion and exclusion criteria retrieved 127 potentially relevant articles. Eventually, 14 maxilla, 20 mandible and 12 condyle articles with focus on bone healing were retained, and were analysed together with 3 methodological papers. Each study was described systematically in terms of subject, experimental intervention, follow-up period, selected region of interest used in the micro-CT analysis, parameters quantified, micro-CT scanner device and software. The evidence level evaluated by the ARRIVE guidelines showed high mean scores (between 18 and 25; range: 0–25), indicating that most of the selected studies are well-reported. The major obstacles identified were related to sample size calculation, absence of adverse event descriptions, randomization or blinding procedures.

Conclusions

The evaluated studies are highly heterogeneous in terms of research topic and the different regions of interest. These results illustrate the need for a standardized methodology in micro-CT analysis. While the analysed studies do well according to the ARRIVE guidelines, the micro-CT procedure is often insufficiently described. Therefore we recommend to extend the ARRIVE guidelines for micro-CT studies.

Keywords: Bone micro-architecture, Rodent jaws, Maxilla, Mandible, Condyle, Micro-CT

Highlights

-

•

This review investigates discrepancies between reports using micro-CT imaging of rodent jaw bone, the applied methodology and reported results.

-

•

Knowledge about the bone micro-architecture of the rodent jaw is scarce.

-

•

Jaw bone micro-architecture varies according to ROI selections and the methodology applied to define a specific region are insufficient.

1. Introduction

Knowledge about macro- and micro-structural characteristics of (regenerated) bone tissue may improve the ability to estimate in vivo its quality and quantity. For this purpose, micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) imaging techniques are appropriate and enable assessing the micro-architecture of bone with 2D and 3D quantitative evaluation [1], [2]. The micro-CT technique permits to quantify simultaneously different bone parameters, such as geometry, mass, mineral density, trabecular parameters (thickness, number, separation and connectivity of the trabeculae, degree of anisotropy), cortical parameters (bone area, thickness, porosity, periosteal and endocortical perimeter) and marrow volume.

The quantitative assessment of the skeletal tissues in animal experiments often varies between studies, depending on the experimental rationale and applied protocol. With regard to the maxillofacial bone and teeth, micro-CT analysis has been mainly used to evaluate alveolar bone remodelling [3], [4], [5], the dynamic changes in periodontal ligament thickness [6] as well as specific osseous sites in the cortical and trabecular bone compartment [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]. However, many of such studies have used micro-CT imaging analyses without detailed description of the applied methodological parameters such as region of interest, the histograms of grey level, the scripts used in the analysis software and the outcome variables. Therefore, it becomes difficult to compare the quantitative results from different studies.

Despite some available protocols for rodent jaw bone analysis, including those for maxilla, mandible and condyle [2], [5], [12], these remain scarce in literature and are often not informative and detailed enough. Therefore, a systematic review dealing with the available literature data on the rodent's jaw bone microstructure could provide guidelines and future directions for the conduction of small animal studies using the micro-CT methodology. To the author's knowledge, only 2 reports have tried to describe in a detailed way the protocols for investigating the rodent jaw bone anatomy and micro-structure. Kallai et al. (2011) have detailed the successive steps of micro-CT analysis of bone regeneration in mice, including the acquisition of the images. The authors focused on 3 specific experimental models: the ectopic bone formation model, the long bone segmental defect model and the critical-sized mandibular bone defect model. Bagi et al. (2011) have described the physiological aspects of the jaw bone anatomy by means of micro-CT imaging, but with description of the cancellous and cortical bone parameters solely for the mandible. Besides the aforementioned papers, other original animal studies made use of the micro-CT technique for assessing the rodent jaw bone architecture in diverse conditions, including the evaluation of changes in bone volume, mass and micro-architecture in response to mechanical loading [9], [14] or to the animal's systematic status such as osteoporosis [8], [15] and diabetes [16]. When analysing the methodological approaches used in these studies, only Abtahi et al. (2013) and Kuroshima et al. (2013) have followed the ARRIVE guidelines. The ARRIVE guidelines have been introduced by Kilkenny et al. [17], bringing to light the importance of high quality research in pre-clinical small animal experiments. A large heterogeneity is observed with respect to the study design, animal species, type of intervention, follow-up period and sites and their dimensions under investigation by micro-CT.

Therefore, the aim of the present review was to assess, through a systematic screening of the scientific literature, how micro-CT imaging has being applied in rodent animal models for investigation of the micro-architecture of the jaw bone. In addition to this general objective, 2 specific questions were formulated: (i) In micro-CT imaging analysis investigating the micro-architecture of rodent jaw bones, what are the appropriate regions of interest for specific analyses and which morphometric characteristics can be quantified?; and (ii) what is the quality of the reports dealing with the rodent jaw bone micro-architecture which use micro-CT imaging, according to the ARRIVE guidelines?

2. Methods

2.1. Focused question

The authors aimed to identify all studies in which the rodent jaw bone micro-architecture was imaged by micro-CT and quantitatively evaluated. In particular, the appropriateness of the selected regions of interest and of the applied morphometrical parameters was questioned. In addition, the quality of reporting of the animal experimental research in this context was analysed using the tailored ARRIVE guidelines purposed by Vignoletti and Abrahansson (2012).

2.2. Database search protocol

Two authors (FF) and (MC) performed the literature search for the present systematic review. The National Library of Medicine's PubMed electronic database was used to identify appropriate papers, written in English between January 2003 and December 2013. Boolean “AND” MeSH terms served to include micro-CT studies in maxillar, mandibular or condyle bone in rodent animal models. The following MeSH terms were applied: ((“x-ray microtomography” OR “microtomography” OR “microct”) AND (“maxilla” OR “maxillary bone”) AND (“mandible” OR “mandibular bone”) AND (“tmj” OR “condyle”) AND (“rodent animals”)).

From the retrieved list, papers were screened by title and those non-pertinent to the present review's aim were excluded. Of the remaining references, abstract reading was performed and those considered of potential interest were retrieved in full text and read for evaluation of inclusion/exclusion criteria. In addition, the bibliography list of the papers was hand searched for possible missing articles. In case of disagreement between the reviewers, a consensus was reached during a joint session with author KV.

2.3. Study selection

2.3.1. Inclusion criteria

Animal studies quantifying the bone micro-architecture of the maxilla, the mandible and/or the condyle, in physiological (considering also extraction sites) or drug-induced disease status, or in response to interventions such as mechanical loading, hormonal treatment and other metabolic alterations, were selected.

2.3.2. Exclusion criteria

Manuscripts dealing with micro-CT evaluation of mineralized jaw tissues (bone; teeth) (i) in 3D, but without quantification of the investigated parameters, (ii) based only on linear or descriptive volumetric measurements, (iii) of craniofacial skeletogenesis or orthodontic teeth movement, (iv) at periodontal defect sites, (v) as anatomical description of tooth structures, and (vi) at critical-sized bone defects (including grafted sites) were excluded.

2.3.3. Assessment of quality and validity

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed according to the checklist “Methodological evaluation of Animals in Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments (modified version of the ARRIVE guidelines)” [18], which contains 20 items to appraise the communication of information and to allow repeatability of experiments. Following these tailored ARRIVE guidelines, qualitative assessment of the information provided in the selected papers was performed and ranked as follows: 0–1 (absent–present) or 0–1–2 (poor–adequate–good). The total sum of the scores was calculated for each paper. The total score could range between 0 and 28.

3. Results

3.1. Screening

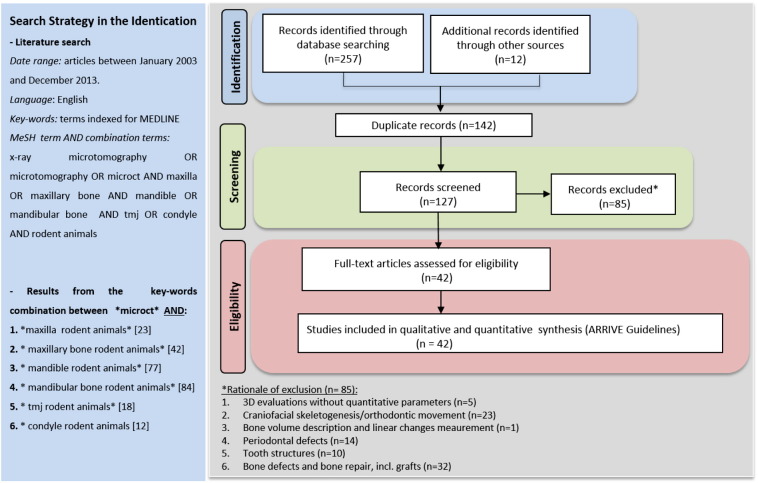

The literature screening procedure of this systematic review is described in Fig. 1. The electronic search performed in the PubMed database of the US National Library of Medicine resulted in 257 retrieved papers. From a total of 127 potentially relevant papers, 85 were excluded after review of title and abstract, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The remaining 42 articles were considered relevant to the topic and the full text was reviewed in detail. Fourteen studies were classified as experimental studies on the rodent maxilla, 20 studies were performed on the rodent mandible and 12 on the rodent condyle.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of articles screened during literature search.

3.2. Quantitative analysis

All papers were grouped relative to the jaw bone region. For each paper, the following items were listed: subject of the study, experimental intervention, follow-up period, selected region of interest used in the micro-CT analysis, parameters quantified, micro-CT scanner device and software. Two articles described bone alterations in both maxilla and mandible [3], [7], and two in mandible and condyle [11], [19]. Six studies applied in vivo micro-CT, performed in the maxilla [6], [15], [20], [21] and in the condyle [10], [22]. The scanning device which was most often used was the μCT 40 (Scanco Medical, Brüttisellen, Switzerland) [9], [11], [13], [14], [19], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], followed by the Skyscan apparatus (Skyscan, Aartselaar, Belgium) [3], [4], [8], [20], [21], [32], [33], [34], [35]. The results of the quantitative analysis are presented in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4.

Table 2.

Studies using micro-CT for the analysis of the micro-architecture of rodent mandibular bone (20).

| Authors & year | Species, age and number | Experimental intervention | Follow-up | Region of interest | Variables | Scanning device | Software |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pramojanee et al., 2013 | Male Wistar rats (180–200 g) (n = 50) * Age not described |

High-fat diet in insulin-resistant obese rats | 12 weeks | M2 region in hemi-mandibles ROI: c.f. Abassy et al. (2010) described below |

TV, BV, BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, Tb.Sp, porosity | Skyscan 1072 (Aartselaar, Belgium) | CTAn (Skyscan) |

| Kuroshima et al., 2013 | Female 6 weeks old Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 48) | Injection of PTH | 28 days | Extraction sockets of M1 ROI: Dimensional change of the alveolar ridge by assessment of the ridge height relative to the cement-enamel junction and thickness of buccal and lingual bony plates |

BMD, Tb.Th, Tb. N, Tb.Sp, bone fill | - eXplore Locus SP Micro-CT (GE Healthcare, London, UK) - Micro-CT-100 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) |

Skyscan built-in software |

| Shimizu Y et al., 2013 | Male 13 weeks old Wistar rats (n = 12) | Indirect loading via diet modification | 9 weeks | Interradicular alveolar bone of M1 ROI: area in between the apex of the mesial and distal roots that is limited by the borders of the septum. |

BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, MIL, Vm, Tb.W, Vt | SMX-100CT (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) | TRI/3-D-BON (Ratoc System Engineering, Tokyo, Japan) |

| Bouvard et al., 2013 | Male 5 months old Swiss–Webster mice (n = 20) | Administration of glucocorticoids (prednisolone) pellets (releasing 5 mg/kg/day) | 28 days | Right hemi-mandible a) ROI: 10 sagittal sections of centre of pulp chamber of M1 b) ROI: alveolar process surrounding the pulp chambers of 3 molars |

BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, Tb.Sp, Tb.Pf, SMI | Skyscan 1172 (Aartselaar, Belgium) | CTAn (Skyscan) |

| Donneys et al., 2012 | Male Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 8) * Age not described |

None | Information not provided | Left hemi-mandible ROI: Connective tissue surrounding roots of M1 and M2 (cortical bone shell not included in the analyses) |

BMD, mineralization total number of voxels, mineral heterogeneity | No information provided | MicroView 2.2 Software (Parallax Innovations Inc., Ilderton, Canada) |

| Mijares et al., 2012 | Female 2 months old Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 30) | Ingestion of synthetic bone mineral preparation in animals with mineral deficiency | 3 months | Left or right mandible: alveolar crestal bone, alveolar middle bone and mandible body ROI: cross sections provided by 25 slices mesial to M1 |

BV, TV, BV/TV, BMD, porosity | μCT40 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | μCT Software version 6.0 (Scanco Medical) |

| Zhang et al., 2011 | Female and male 70.5 days old mice (n = 28) | High-calcium diet | 40.5 days | Mesial of M1, M2 and M3 at different levels: a) ROI Buccal alveolar bone: the pear-shape alveolar bone bordered from the most concave point in the buccal surface b) ROI Cementum-dentine complex: whole area in apical 1/3 of the root |

Thickness, area, radiopacity, | No information provided | NIH shared software (Bethesda, Maryland, USA) |

| Shimizu et al., 2011 | Male 5 weeks old Wistar rats (n = 24) | Selective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist in animals with occlusal hypofunction simulation | 1 week | Interradicular alveolar bone of M1 ROI: bone by defining the borders of the septum between the roots |

BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N | SMX-90CT (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) | TRI/3-D-BON (Ratoc System Engineering, Tokyo, Japan) |

| Bagi et al., 2011 | Female and male 5 months old (n = 24) - Mice (n = 12) - Rats (n = 12) |

No intervention (animals that received vehicles in previous studies) | Information not provided | Right mandible ROI: square area of trabecular bone below M1 and M2 (dimensions not described) |

TV, BV, BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.Sp, Tb.Co, BMD, C.Th, Ma.V | Viva CT 40mCT system (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | Viva CT 40mCT software (Scanco Medical) |

| Enomoto et al., 2010 | Male 3 weeks old mice (n = 25) | Indirect loading by means of mastication force relative to diet patterns | 4 weeks | Mandibular body | Bone volume | SMX-100CT (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) | TRI/3-D-BON (Ratoc System Engineering) |

| Mavropoulos et al., 2010 | Male 21 days old Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 44) | Indirect loading by means of mastication during growth via diet modification | 27 weeks | Left hemi-mandible ROI: M1 trabecular bone, drawn on a slice-based method starting from the 1st slice displaying the crown of M1 and moving dorsally 100 slices. The trabecular bone was manually delineated on the first and the last slice. |

TV, BV, BS, Tb.Th, Tb.N | μCT40 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | μCT Software version 6.0 (Scanco Medical) |

| Abbassy et al., 2010 | Male 3 weeks old Wistar rats (n = 10) | Induction of type 1 diabetes mellitus by streptozotocin injection | 28 days | Left mandible ROI: M2 trabecular bone — drawn on a slice-based method starting from the 1st slice displaying the crown of M1 and moving dorsally 100 slices. Delineation of the bone in the area of the alveolar crest (between the buccal and lingual roots of M2 at the cervical region) and the buccal surface of the jaw bone. |

TV, BV, BS, BS/BV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, Tb.Sp, Tb.S | SMX-90CT (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) | MultiBP (Imagescript, Tokyo, Japan); TRI/3-D-BON (RATOC System Engineering, Tokyo, Japan) |

| Ames et al., 2010 | Female 6 months old Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 20) | Ovariectomized rats | 2 months | Tooth bearing 5 mm mandibular bone sections ROI: alveolar bone within 200 μm from the tooth |

Bone tissue mineral density based on histograms grey levels equivalent | Inveon (Siemens, München, Germany) | Software Image J (NIH shared software, USA) |

| Kingsmill et al., 2010 | Female 2 months old rats (n = 14) | Indirect Loading via diet modification: soft diet during growth | 8 or 20 weeks | Left Mandible ROI: molar region, from furcation of M1 to the furcation of M3 |

BV | No information provided | Imaris software (Bitplane AG, Zurich, Switzerland) |

| Kozai et al., 2010 | Male 10 weeks old Fisher rats (n = 24) | Prednisolone treatment (40 mg/kg) | 8 weeks | Mandible ROI: 100 slices from the medial root apex region of M1 |

BM, B.St, trabecular structure | MCT-100MF (Hitachi Medical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) | TRI/3-D-BON (RATOC System Engineering, Tokyo, Japan) |

| Sheng et al., 2009 | Female 6 weeks old mice C57BL/6J (n = 28) - OPG−/− mice (n = 21) - Wild-type mice (n = 7) |

Zalendronate treatment (50 or 150 μg/kg) | 4 weeks | Trabecular and cortical bone a) ROI in trabecular region: mesial region of M1 to distal limit of M3, excluding the molar and incisor roots b) ROI in cortical area: square area of 1.5 × 1.5 mm2 in the buccal region of mandibular body |

BMD, BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, Conn.D, Tb.Sp, SMI | eXplore Locus SP (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, USA) | Modified Feldkamp cone beam algorithm |

| Tanaka et al., 2007 | Male 3 weeks old Wistar rats (n = 15) | Standard diet versus soft diet | 9 weeks | Anterior and posterior region in the mandibular body of right mandible ROI: 4 selected regions cortical bone on the buccal side of the approx. 1 mm3 (15 × 15 × 15 μm3 voxels) |

BV; TV; BV/TV | μCT40 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | μCT Software version 6.0 (Scanco Medical) |

| Ravosa et al., 2007 | Male 6 months old mice (n = 21) - Myostatin-deficient (n = 11) - Wild-type (n = 10) |

Elevated masticatory loads | 6 months | Mandible — coronal sections a) ROI in the symphysis: along the symphyseal articular surface, outer surface of cortical bone and among incisor tissues b) ROI in the corpus: along the outer surface of the cortical bone, among incisor issues and molar tissues |

Bone density (Biomineralization) | μCT40 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | No information provided |

| Mavropoulos et al., 2007 | Female 6 months old Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 44) | Sham and OVX rats fed with pair-fed isocaloric diets containing 15% or 2.5% casein | 16 weeks | Mandible ROI: Slice-based method starting from 1st slice displaying the crown of M1 and moving dorsally 100 slices |

BMD, BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N | μCT40 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | No information provided |

| Mavropoulos et al., 2004 | Male 3 weeks old albino Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 36) | Hard diet versus soft diet with upper posterior bite block in situ | 6 weeks | Left mandible ROI: Crown of M1, 100 slices dorsally |

TV, BV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, Tb.Sp | μCT40 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | No information provided |

M1, first molar; M2, second molar; M3, third molar; BV/TV or BVF, bone volume fraction; Tb.Th, trabecular thickness; Tb.N, trabecular number; Tb.Sp, trabecular separation; Tb.S, trabecular space; Tb.Pf, trabecular pattern factor; SMI, structure model index; DA, degree of anisotropy; BMD, bone mineral density; MIL, mean intercept length; Tb.Co, trabecular connectivity; TB.W, trabecular width; Vm, marrow space star volume; Vt, trabecular star volume; C.Th, cortical thickness; Ma.V, marrow volume; BS, bone surface; BS/BV, bone surface/bone volume; BM, bone mass.

Table 3.

Studies using micro-CT for the analysis of the micro-architecture of rodent condyle bone (12).

| Authors & year | Species, age and number | Experimental intervention | Follow-up | Region of interest | Variables | Scanning device | Software |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kosugi et al., 2013 | Male 5 weeks old Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 8) | Osteoporosis induced by FK506 (immunosuppressant drug) at o dose of 1 mg/kg/day | 5 weeks | Bilateral condyle head ROI: 2000 μm from the region of the maximal width of each condylar head in the direction of the centre of the diaphysis |

BV/TV; Tb.Th; Tb.N; Tb.Sp and SMI | R_mCT, Rigaku (Tokyo, Japan) | TRI/3-D-BON (Ratoc System Engineering, Tokyo, Japan) |

| Zhang et al., 2013 | Female 8 weeks old Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 36) | Temporomandibular joint-Osteoarthritis model | 12 and 32 weeks | Condylar subchondral bone ROI: 2 cubic regions of 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 mm in the centre of the middle and posterior regions of the condyle. |

BMD; BV/TV; BS/BV; Tb.Th; Tb.N; Tb.Sp; BMD | In vivo Micro-CT, Inveon (Siemens, München, Germany) | Software provided by Inveon (Siemens) |

| Li et al. 2012 | Female 7 weeks old Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 30) | Genistein administration (10 and 50 mg/kg) | 6 weeks | Condylar subchondral bone. ROI: 2 cubic regions of 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 mm in the centre of the middle and posterior regions of the condyle. |

BMD; BMC; BV/TV; BS/BV; Tb.Th; Tb.N; Tb.Sp; BV | GE eXplore Locus SP (GE Healthcare, London, UK) | General Electrical Health Care MicroView ABA2.1.2 (GE Health care) |

| Mijares et al., 2012 | Female 2 months old Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 30) | Synthetic bone mineral preparation (SBMP) administration in animals with mineral deficiency | 3 months | Condyle head in hemi-mandibles ROI: 100 slices from the condyle tip |

3D constructions of micro-CT images BV/TV, Porosity |

μCT40 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | μCT Software version 6.0 (Scanco Medical) |

| Kuroda et al., 2011 | Male 5 weeks old Wistar rats (n = 16) | Induction of intermittent posterior condylar displacement during the growth period | 14 days | Condyle cancellous bone ROI: 1.0 × 1.0 × 0.2 mm at the centre of the anterior and posterior halves of the condylar head. |

BV/TV; TbN; TbTh; TbSp; Degree of anisotropy (DA) | SMX-100CT (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) | No information provided |

| Chen et al., 2011 | Female and male 21 days old (n = 118) - CD-1 mice (n = 70) - C57BL/6 (n = 48) |

Decreased occlusal loading TMJ remodelling model | 4 weeks | Volumetric regions including condyle head ROI: Approximately 0.25 mm3 as a total volume of bone of the mandibular condyle |

BV/TV; TbTh; TbSp | μCT40 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | No information provided (Standard convolution back-projection algorithms with Shepp and Logan filtering) |

| Sobue et al., 2011 | Female 6 weeks old C57BL/6 wild-type (n = 48) | Increased loading by forced mouth opening | 5 days | Volumetric regions including mandibular condyle. ROI: Framed area showed in a figure of the mid-sagittal cross sections of the mandibular condyle head |

BV/TV; TbTh; TbSp | μCT40 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | No information provided (Standard convolution back-projection algorithms with Shepp and Logan filtering) |

| Jiao et al., 2010 | Female and male Sprague–Dawley rats 2,3,4,5,6 and 7 months old (n = 84) | Age and sex differences | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 months | Subchondral trabecular bone ROI: 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 mm at the centre of the posterior condyle |

BV/TV; BS/BV; TbN; TbTh; TbSp; BMD | GE eXplore Locus SP (GE Healthcare, London, UK) | General Electrical Health care MicroView ABA2.1.2 (GE Health care) |

| Chen et al., 2009 | Female and male mice 3 and 9 months old (n = 96) - B6/129 WT (n = 48) - Double-deficient Bgn/Fmod (n = 48) |

Osteoarthritis model | 3 or 9 months | Subchondral bone of condylar head ROI: Not specified, the scale bars were set at 200 μm for the measurements in midsagittal cross-sections |

BV; TV; Tb.Th; Tb.N; Tb.Sp | μCT20 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | No information provided |

| Sriram et al., 2009 | Female 12 weeks old C3H mice (n = 40) | Mechanical vibration of 30 Hz, for 20 min/day, 5 days/week | 28 days | Condylar cartilage and endochondral bone. ROI: 0.0452 mm3, in the condylar bone beneath the midpoint of the condylar cartilage and lying within the superior third of the condylar process. |

Volume of condylar cartilage and bone histomorphometric parameters | SkyScan 1172 (Aartselaar, Belgium) | VGStudio Max (Volume graphics GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) |

| Tanaka et al., 2007 | Male 3 weeks old Wistar rats (n = 15) | Standard diet versus soft diet | 9 weeks | Centre of the condyle ROI: approx. 1 mm3 (15 × 15 × 15 μm3 voxels) in the trabecular bone |

BV; TV; BV/TV | μCT40 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | μCT Software version 6.0 (Scanco Medical) |

| Nicholson et al., 2006 | Male 6 months old - Myostatin-deficient mice (n = 23) - Wild type (n = 11) - Homozygous for disrupted GDF-8 sequence (n = 12) |

Indirect loading by mastication | 6 months | Anterior, middle and posterior sections of the condyle ROI: Approximately 1 mm3 determined in outer, inner and neck regions |

Mineral levels — values based on attenuation coefficients | μCT40 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | Software Image J (NIH shared software, USA) |

M1, first molar; M2, second molar; M3, third molar; BV/TV or BVF, bone volume fraction; Tb.Th, trabecular thickness; Tb.N, trabecular number; Tb.Sp, trabecular separation; Tb.S, trabecular space; Tb.Pf, trabecular pattern factor; SMI, structure model index; DA, degree of anisotropy; BMD, bone mineral density; MIL, mean intercept length; Tb.Co, trabecular connectivity; TB.W, trabecular width; Vm, marrow space star volume; Vt, trabecular star volume; C.Th, cortical thickness; Ma.V, marrow volume; BS, bone surface; BS/BV, bone surface/bone volume; BM, bone mass.

Table 4.

The scores (assessed by authors MC and FF) for the ARRIVE guidelines (18). Items 1–3 and 16 can be scored as 0, 1, or 2 (poor/adequate/good respectively); all other items by 0 or 1 (yes/no).

| Reference & year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6a | 6b | 7a | 7b | 7c | 8 | 9 | 10a | 10b | 11 | 12a | 12b | 12c | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maxilla | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kuroshima et al. (2013) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 22 |

| Dai et al. (2013) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 22 |

| Shimizu et al. (2013) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 19 |

| Xu et al. (2013) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 21 |

| Abtahi et al. (2013) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 22 |

| Tanaka et al. (2012) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 23 |

| Armin et al. (2012) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 19 |

| Alikhani et al. (2012) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 22 |

| Zhao et al. (2012) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 19 |

| Zhao et al. (2012) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 20 |

| Chang et al. (2012) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 19 |

| Baloul et al. (2011) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 20 |

| Zhuang et al. (2011) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 25 |

| Teixeira et al. (2010) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 20 |

| Mandible | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pramojanee et al. (2013) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 21 |

| Kuroshima et al. (2013) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 22 |

| Shimizu et al. (2013) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 19 |

| Bouvard et al. (2013) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 21 |

| Donneys et al. (2012) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 13 |

| Mijares et al. (2012) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 21 |

| Zhang et al. (2011) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 16 |

| Shimizu et al. (2011) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 19 |

| Bagi et al. (2011) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 18 |

| Enomoto et al. (2010) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 20 |

| Mavropoulos et al. (2010) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 20 |

| Abbassy et al. (2010) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 17 |

| Ames et al. (2010) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 20 |

| Kingsmill et al. (2010) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 20 |

| Kozai et al. (2010) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 18 |

| Sheng et al. (2009) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 21 |

| Tanaka et al. (2007) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 23 |

| Ravosa et al. (2007) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 21 |

| Mavropoulos et al. (2007) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 22 |

| Mavropoulos et al. (2004) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 21 |

| Condyle | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kosugi et al. (2013) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 19 |

| Zhang et al. (2013) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 21 |

| Li et al. (2012) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 24 |

| Mijares et al. (2012) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 21 |

| Kuroda et al. (2011) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 20 |

| Chen et al. (2011) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 22 |

| Sobue et al. (2011) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 20 |

| Jiao et al. (2010) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 22 |

| Chen et al. (2009) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 21 |

| Sriram et al. (2009) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 21 |

| Tanaka et al. (2007) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 23 |

| Nicholson et al. (2006) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 21 |

3.2.1. Maxilla

The studies conducted in the rodent maxilla were published only recently, with the first report released in 2010. The majority of the selected studies were published in 2012. Most articles (n = 8) were within the orthodontic field [6], [9], [14], [15], [20], [21], [24], [36]. Furthermore, the most frequently analysed regions of interest were the alveolar bone surrounding the first molar tooth and the interradicular septal bone. The effect of drug interventions on the maxillar bone was investigated in 4 studies [3], [8], [16], [23], with extraction sockets as region of interest for assessing the drug-induced bone response. Only 1 study [9] focused on the effect of mechanical loading on the alveolar bone. Finally, concerning the type of animals used, Sprague–Dawley rats were used in the majority of the studies (n = 10) [3], [4], [6], [8], [9], [14], [16], [23], [24], [35], with an age varying from 12 days to 13 weeks old. Two reports failed to describe the rodent age [14], [16] and one to inform on gender and age [24].

3.2.2. Mandible

A total of 10 papers investigated the effect of mechanical loading, through diet texture modification and mastication [7], [11], [13], [19], [27], [29], [31], [36], [37], [38] on the bone micro-architecture, while 8 addressed the effect of drug intervention [3], [12], [32], [34], [39], [40], [41], [42]. One paper investigated the mandibular bone architecture in the ovariectomy-induced osteoporotic animal [43]. For the study referred to as Donneys et al. (2012), there was no experimental intervention involved and the rodent age was not mentioned as well. With regard to the time point of publication, all articles were published after 2004 (2013 (n = 4); 2012 (n = 2); 2011 (n = 3); 2010 (n = 6); 2009 (n = 1); 2007 (n = 3) and 2004 (n = 1)).

3.2.3. Condyle

A total of 3 papers investigated the effect of forced mouth opening on mandibular condyle structure, in both male and female rats [26], [28], [45]. Two longitudinal studies [10], [22] on condylar micro-architectural changes in response to experimental interventions such as osteoporosis and occlusal loading were retrieved. With regard to the effect of loading, one study focused on the therapeutic effect of a synthetic bone mineral preparation (as a diet supplement) to reduce the alveolar bone loss in female rats subjected to a mineral deficient diet [11], while another one investigated the effect of direct loading via mechanical vibration on the condylar bone [33]. Two papers assessed the effect of indirect loading via diet modification and mastication on the condyle bone changes [19], [30]. Furthermore, one paper studied the impact of drug intervention (genistein, a phytoestrogen) on bone homeostasis analysing the morphology and micro-architectural properties of mandibular condylar subchondral bone [46]. The paper of Jiao et al. (2010) assessed the impact of age and sex on the condylar bone micro-architecture [47]. Finally, the osteoarthritis model was applied in one study [28]. With regard to the timing of publication, again the articles were published quite recently, with the earliest one in 2006 (2013 (n = 2); 2012 (n = 1); 2011 (n = 3); 2010 (n = 2); 2009 (n = 2); 2007 (n = 1) and 2006 (n = 1)).

3.3. Qualitative assessment

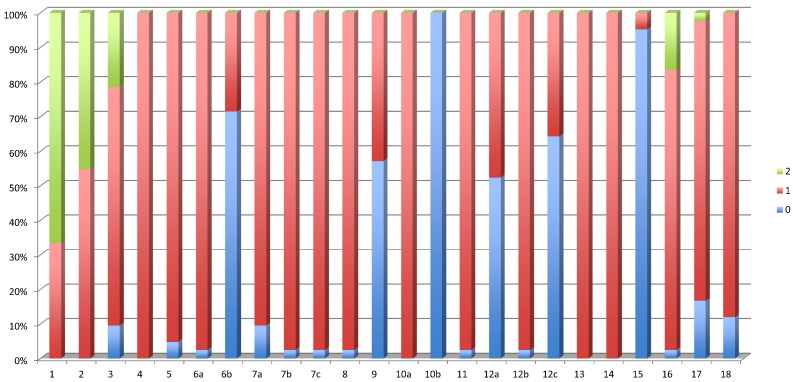

The results of the qualitative assessment of the 42 selected reports are presented in Table 4. The mean score (range: 0–28) was 20.38. The mean scores for maxilla, mandible and condyle were 20.90, 19.30 and 21.16 respectively. The maximum score of 25 was registered for a report on the maxillar bone [35], while a minimum sore of 13 was found in a mandibular study [44]. The median score was 21 and was reached by 11 studies: 1 in the maxilla [6], 6 in the mandible [11], [13], [31], [32], [34], [42] and 4 in the condyle [22], [25], [30], [33].

The frequency distribution of the different scores for the modified ARRIVE guidelines is presented in Fig. 2. Although 2 studies mentioned that the ARRIVE guidelines had been followed [3], [8], these studies did not, to the author's appraisal, reach the maximum score. For the ARRIVE items 6b, 9, 10b, 12a, 12c and 15, more than 55% of the studies scored 0. Not one study detailed the sample size calculation. Adverse effects were only sporadically mentioned. Furthermore, no description of randomization or blinding procedures was noted in 71.42% of the studies. Considerations about the ethical information were not provided in 5% of the studies. Less than half of the studies (42.85%) mentioned animal housing and husbandry conditions. Details of the statistical methods used were not specified in 52.38% of the studies, and 64.28% of the reports did not provide details or discuss the validation of the used statistical method.

Fig. 2.

Histograms presenting the frequency distribution (%) of the scores assessed for the modified ARRIVE guidelines for the included studies (n = 42). Items 1 to 3 and item 16 could score 0, 1 or 2 (poor, adequate or good). All other items could score 0 or 1 (yes/no).

4. Discussion

The micro-CT technique is a technology which enables 3D reconstruction of the internal structure of small X-ray opaque objects and non-invasive qualitative and quantitative assessment of e.g. spatial and temporal evolutions of the bone tissue micro-architecture. In the present review, the main objective was to assess, through a systematic screening of the literature, how micro-CT imaging has been applied in rodent animal models for quantitative investigation of the bone micro-architecture of the jaws. It was observed that, when rodent models are used to quantify the jaw skeleton, the protocol and findings are rather rarely presented in a standardized manner. Furthermore, a considerable amount of retrieved reports needed exclusion (n = 84) as, in most of these studies, micro-CT was used with the sole objective to illustrate the results through 3D images, or for measuring linear alterations which could also be performed by simple radiographic techniques.

This systematic review also investigated potential discrepancies between the applied bone micro-structural parameters over the different studies. Despite the huge variability between the eligible studies, the authors were able to summarize the relevant bone micro-architectural characteristics in a standardized manner, based on 3 main variables related to bone morphology (cf. Table 1, Table 2, Table 3): (i) analysed bone type (maxilla, mandible and condyle), (ii) region of interest (ROI), based on the research question addressed in a specific study (e.g. 1 quantity of alveolar bone in the molar region; e.g. 2 thickness of the cortical shell) and (iii) use of established bone morphometrical parameters. Concerning the latter variable, the trabecular thickness, the trabecular separation and the trabecular number are the most commonly reported parameters.

Table 1.

Studies using micro-CT for the analysis of the micro-architecture of rodent maxillar bone (n = 14).

| Authors & year | Species, age and number | Experimental intervention | Follow-up | Region of interest | Variables | Scanning device | Software |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kuroshima et al., 2013 | Female 6 weeks old Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 30) | Parathyroid-hormone administration | 7, 14 and 28 days | - Interradicular bone of M1 between mesial and distal roots - Trabecular compartment in extraction sockets of M2 ROI: Semi-manual contouring method |

BVF, BMD, Tb.N, Tb.Th, Tb.Sp, bone fill | μCT-100 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | Scanco software (Scanco Medical) |

| Dai et al., 2013 | Female 6 weeks old Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 32) | Bilateral ovariectomy | 12 weeks | Interradicular region of the right maxillary M1 ROI: pentagon whose vertices formed the centres of the five roots on the two separate horizontal surfaces |

BMD, BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, Tb.Sp | GE eXplore Locus SP Micro-CT (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) | MicroView ABA 2.2 (GE Healthcare) |

| Shimizu et al., 2013 | Male 13 weeks old Wistar rats (n = 12) | Indirect loading through diet modification | 9 weeks | - Interradicular septal bone of M1 ROI: a coronal plane was defined by symmetry of all dental roots, a coronal section through the roots, 2/3 of their length from the apex. |

BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, MIL, Vm, Tb.W, Vt | SMX-100CT (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) | TRI/3-D-BON (Ratoc System Engineering, Tokyo, Japan) |

| Xu et al., 2013 | Female 8 weeks old Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 30) | Orthodontic movement with forces of 30/100 g | 14 days | Alveolar bone surrounding M1 ROI: a 700 × 700 × 700 μm cube of trabecular bone, mesial to the middle third of the distobuccal root. Distance between ROI and root set at 200 μm |

BV/TV; SMI; TbTh, Tb.N, Tb.Sp | Siemens (München, Germany) | Recon: Inveon Research Work Place (Siemens) Analysis: not provided |

| Abtahi et al., 2013 | Male 10 weeks old Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 40) | Dexamethasone, and systemic (alendronate) and local (zalendronate coated implants) bisphosphonate application | 2 weeks | Extraction site in the sagittal view ROI: 1.86 × 3.2 mm ellipse placed in the extraction site guided by 2 horizontal lines to cover 2/3 of the length from the apex |

BV/TV | SkyScan 1174 (Aartselaar, Belgium) | NRecon and CTAn (SkyScan) |

| Tanaka et al., 2012 | Male 8 weeks old wild-type and OPG−/− mice (n = 16) | Administration of Reveromycin A sodium salt during continuous tooth movement | 14 days | Alveolar crest of the left M1 interradicular septum ROI: roots of M1 and the surrounding alveolar bone |

BV/TV | R_mCT, Rigaku (Tokyo, Japan) | TTRI/3-D-BON (Ratoc, Tokyo, Japan) |

| Armin et al., 2012 | Male 7 weeks old Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 10) | Brachytherapy (20 Gy) versus sham therapy | 28 days | Left M2 region after atraumatic extraction; or bone in the extracted single tooth sockets in M2 region ROI: 0.0746 cm2 circular area |

Bone healing BV/TV |

μCT40 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | μCT Software v.6.0 (Scanco Medical) |

| Alikhani et al., 2012 | Male 12 days old Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 85) | Mechanical loading by vibration versus static load | 28 days | Bone surrounding right M1, M2 and M3 ROI: alveolar bone area extending from the coronal to the apical root third, divided into 3 zones |

BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.Sp | μCT40 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | μCT Software v.6.0 (Scanco Medical) |

| Zhao et al., 2012 | Male 6 weeks old Wistar rats (n = 18) | Local osteoprotegerin (OPG) gene transfection | 4 weeks | Alveolar furcation bone of M1 ROI: Most mesial and distal roots as landmark borders to guide the ROIs drawing at 144 μm intervals |

BMD, BVF | SkyScan 1076 (Aartselaar, Belgium) | MIMICS 13.1 Software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) In-house software |

| Zhao et al., 2012 | Male 6 weeks old Wistar rats (n = 18) | Local OPG gene transfer by mock vector transfer | 2 weeks | Alveolar furcation bone of M1 ROI: 100 slices in the furcation area |

BMD, BVF | SkyScan 1076 (Aartselaar, Belgium) | In-house software |

| Chang et al., 2012 | Male Sprague–Dawley streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats (n = 36) animals * Age not described |

Tooth-associated osseous defect (2.0 × 2.0 × 1.0 mm), surgically created in the M1 edentulous ridge | 7, 14 and 21 days | Right M1 ROI: a box-shaped region, with boundaries the mesial side of the mesial roots of M2 (distal limit), 2.6 mm mesial to the distal limit (mesial limit), the buccal aspect of the mesio-buccal root of M2 (buccal limit), and the palatal aspect of mesio-palatal root of M2 (palatal limit). |

BVF, BV, Tb.N, Tb.Th, Tb.Sp | Inveon (Siemens, München, Germany) | CTAn (SkyScan, Aartselaar, Belgium) |

| Baloul et al., 2011 | Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 67) *Age and sex not described. |

Tooth movements by: i) selective alveolar decortication (SADc) ii) “combined therapy” = (SADc + Tooth movement alone) |

0, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, 42 days | Mineralized tissue surrounding M1 ROI: Bone area between 5 roots of M1 with the exclusion of tooth-mineral structure using the contouring option |

TV, BV, BV/TV, BMD, BMC | μCT40 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | μCT Software v.6.0 (Scanco Medical) |

| Zhuang et al., 2011 |

Male 11 weeks old Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 22) | Orthodontic movement with forces of 30 g/100 g | 2 weeks | Mesial root of right M1 ROI: a 300 μm × 300 μm × 300 μm cube of trabecular bone distal to the apical third of the root |

BV/TV, Tb.Sp, BCV | SkyScan 1172 (Aartselaar, Belgium) | NRecon and CTAn (SkyScan) |

| Teixeira et al., 2010 |

Male adult Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 48) *Age not described |

Cortical bone osteoperforations | 28 days | Bone surrounding right M1, M2 and M3 ROI: Alveolar bone area extending from the coronal to the apical root third, divided into 3 zones |

BV/TV | μCT40 (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) | μCT Software v.6.0 (Scanco Medical) |

M1, first molar; M2, second molar; M3, third molar; BV/TV or BVF, bone volume (fraction); Tb.Th, trabecular thickness; Tb.N, trabecular number; Tb.Sp, trabecular separation; Tb.S, trabecular space; SMI, structure model index; DA, degree of anisotropy; BMD, bone mineral density; MIL, mean intercept length; Tb.Co, trabecular connectivity; Tb.W, trabecular width; Vm, marrow space star volume; Vt, trabecular star volume; C.Th, cortical thickness; Ma.V, marrow.

From previous studies it is known that the cortical bone is considered as an important target for bone quality assessment and pharmacological treatment, in contrast to the trabecular compartment, with dimensions that are strongly site-dependent and constantly subjected to remodelling [1]. The study by Bagi et al. (2011) was the sole study where micro-CT methodology was used to explore the physiological bone micro-architecture, by evaluating the quantity of trabecular and cortical bone in the rodent mandible. It was seen that, due to the anatomic differences in root morphology, retrieving accurate measurements of the trabecular bone, in particular at the site of the second molar, is difficult. Also the trabecular network assembly and cortico-cancellous morphology was qualitatively and quantitatively different between rats and mice due to the presence of long incisors underneath the molars, as well as to the varying depth, number and position of the molar roots. Despite these limitations, the authors suggested that micro-CT imaging of the jaw bone can indeed offer a reliable methodology for the assessment of the bone morphology, micro-architecture and mineral density.

The literature search also identified 16 reports dealing with interventions which potentially impact the bone micro-architecture and the bone healing or regeneration, with 6 studies applying to the maxilla [3], [4], [8], [15], [16], [23], 6 to the mandible [3], [11], [32], [40], [41], [43] and 4 to the condyle region [10], [22], [28], [46]. It is evident that the control groups included in these studies offer the possibility to extract bone micro-architectural parameters that characterize the physiological bone micro-architectural state. However, these data were again not always described in a quantitative manner (only few studies provided supplementary data), and graphs and 3D visualization was only used for illustrating the main findings. In the retrieved maxillar studies, the inter-radicular bone of the 1st molar was the most popular ROI analysed [3], [4], [7], [15], [20], [21], [24], [35]. Furthermore, when the alveolar bone surrounding the teeth was analysed (in the studies of Alikhani et al. (2012) and Teixeira et al. (2010)), the entire molar region was considered as ROI. ROIs at extraction sites in the trabecular bone localized near or far from the molar teeth were also applied. In the latter analyses, one molar tooth was considered as a point of reference to guide the measurements. For these ROIs, the bone morphometrical parameters were analysed by defining volume of interests via the geometric tools available in the software such as cubes, rectangular box, ellipse and circles. However, the essential information of image processing prior to running the micro-CT images analysis, such as the threshold level definitions and the sequential steps for image processing (morphological operations, histogram, bitmaps, arithmetical and geometric transformations, among others) were poorly described.

The ROI considered for analysis in the mandible showed great heterogeneity: inter-radicular region involving the 3 molars, whole mandibular body, the alveolar ridge, extraction sockets or the alveolar processus surrounding the pulp chamber. In contrast, the defined ROI for condyle analysis was found to be homogeneous for the different studies: most studies focused on evaluating the bone changes in the condylar head, some including the subchondral bone as well as the cartilage interface. The minor differences between the studies concerned the method applied for selecting the volume of interest. A majority of the authors adopted the volumetric area analysis method by drawing accurate cubic regions in the anterior and posterior parts of the condyle. Only 3 of the studies did not provide any information with regard to the analysed area. As seen in the guidelines put forward by Bouxsein et al. (2010), standardized terminology and units are available for reporting results for the bone micro-structure. These guidelines, with a minimum set of variables that should be reported when describing trabecular (16 3D outcomes) and cortical (18 3D outcomes) bone morphology, have been extensively used since the publication of that paper of Bouxsein et al. (2010). In the present systematic review, a total of 19 3D outcomes were described, with 9 of these used in the majority of the studies, namely (i) for the trabecular region: Tb.S, trabecular space; Tb.Co, trabecular connectivity; Tb.Pf, trabecular pattern factor; Tb.W, trabecular width; Vm, marrow space star volume; Vt, trabecular star volume; Ma.V, marrow volume; and (ii) for the cortical region: BM, bone mass and BCV, bone crater volume. For the mandible studies, mineralization parameters such as total number of voxels and mineral heterogeneity, and porosity were measured in addition to the above mentioned variables [13], [44], while in the selected condyle studies, other complimentary morphological parameters were evaluated such as volume of condylar cartilage [33] and values based on attenuation of linear coefficients [30]. All of the 19 parameters are essential for 3D qualitative and quantitative appraisal of the bone micro-architecture.

As a second objective of the present review, the tailored ARRIVE guidelines were used as a tool to provide information about the quality of the conducted studies. High mean ARRIVE scores were reported (between 18 and 25) as described in Table 4, mainly attributable to the fact that the selected studies are published just recently (from 2004 onwards). However, considering each score separately, as observed in the histograms presenting the frequency distribution of the scores (Fig. 2), revealed that the primary problems when reporting experimental research on rodent bone micro-architecture were related to 3 aspects of the methodology: sample size calculation, absence of adverse event description and randomization or blinding procedures. It is quite common in animal studies that the statistical method description is less informative [18]. Indeed, the present systematic review revealed that sample size calculation was not always mentioned. Furthermore, it was noted that often small numbers of animals were used, in particular when applying the less invasive in vivo micro-CT analysis. Besides lack or incomplete description of the statistical part of the study, the second most frequently occurring methodological problem encountered was the absence of adverse event description (superior to 90%). This missing information is not only related to the failures observed during the experimental protocols, but also to the description of the planned actions mitigating the adverse events. Finally, it was observed that up to 70% of the studies did not provide information regarding randomization or blinding procedures. Based on previous systematic reviews on animals experiments [18], [48], it seems that the cited 3 methodological issues are generally neglected, even in the studies reporting that ARRIVE guidelines had been followed. Considering additional methodological information, only the study by Xu et al. (2013) addressed the reproducibility of the evaluations performed by the examiner (in triplicate) and the time interval between each assessment (in casu 2 weeks). Further on, Ames et al. (2010) were one of the few groups who described in detail the image processing, including information about image treatment (3D dilations, binarization and thresholding) and demonstrating the reliability of the applied procedure.

5. Concluding remarks

The studies analysed in this systematic review were heterogeneous with respect to the ROI selected for investigation of the micro-architecture of rodent jaw bones. While micro-CT imaging related morphometrical parameters are available and well-described, the methodological steps to standardize the ROI position used in the micro-CT analysis are usually omitted or insufficiently described. The molar region of maxilla, mandible and condyle are identified as the most interesting and straightforward ROI. However, the micro-architecture of these regions is prone to alterations during experimental interventions. Defining the ROI in the molar region is generally guided and easily reproducible by the tooth morphology, without inclusion of the incisors for the mandibular bone analysis. Hence, quantification of the cortical and trabecular bone surrounding the molars or the mandibular body can potentially reveal hormonal or mechanical interventions on the bone micro-architecture. When the condyle is selected as ROI, the head of the condyle, including the subchondral region is generally the subject of analysis, as the porosity of this bone region can be altered in response to experimental interventions.

At present, a total of 17 different software programs are used for quantification of the jaw bone micro-architecture. Given the large variety of software available, more emphasis should be put on the use of uniform terminologies in micro-CT bone evaluation. While the analysed studies do well according to the ARRIVE guidelines, the micro-CT procedure is often insufficiently described. Therefore we recommend to extend the ARRIVE guidelines for micro-CT studies. Also, in vivo micro-CT studies should be considered, as temporal changes can be identified non-invasively, thereby offering a better understanding of the jaw bone changes in real time. Currently, the resolution limit of the in vivo micro-CT is not always sufficient for bone micro-architecture and vascular network quantification. There is a clear need for advancing the in vivo scanning technologies to address this problem.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the CNPq agency. This work is part of the internship supported by the Brazilian Science Without Borders Program (245450/2012-2 process, Postdoctoral researcher F. Faot; 246131/2012-8 process, doctoral student G. Camargos).

Edited by: Peter Ebeling

References

- 1.Muller R. Hierarchical microimaging of bone structure and function. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2009;5(7):373–381. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouxsein M.L. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010;25(7):1468–1486. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuroshima S. Intra-oral PTH administration promotes tooth extraction socket healing. J. Dent. Res. 2013;92(6):553–559. doi: 10.1177/0022034513487558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dai Q.G., Zhang P. Ovariectomy induces osteoporosis in the maxillary alveolar bone: an in vivo micro-CT and histomorphometric analysis in rats. Oral Dis. 2014;20(5):514–520. doi: 10.1111/odi.12166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kallai I. Microcomputed tomography-based structural analysis of various bone tissue regeneration models. Nat. Protoc. 2011;6(1):105–110. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu Y. Periodontal microstructure change and tooth movement pattern under different force magnitudes in ovariectomized rats: an in-vivo microcomputed tomography study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2013;143(6):828–836. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimizu Y. Soft diet causes greater alveolar osteopenia in the mandible than in the maxilla. Arch. Oral Biol. 2013;58(8):907–911. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abtahi J. Effect of local vs. systemic bisphosphonate delivery on dental implant fixation in a model of osteonecrosis of the jaw. J. Dent. Res. 2013;92(3):279–283. doi: 10.1177/0022034512472335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alikhani M. Osteogenic effect of high-frequency acceleration on alveolar bone. J. Dent. Res. 2012;91(4):413–419. doi: 10.1177/0022034512438590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosugi K. A longitudinal study of the effect of experimental osteoporosis on bone trabecular structure in the rat mandibular condyle. Cranio. 2013;31(2):140–150. doi: 10.1179/crn.2013.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mijares D. Oral bone loss induced by mineral deficiency in a rat model: effect of a synthetic bone mineral (SBM) preparation. Arch. Oral Biol. 2012;57(9):1264–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagi C.M., Berryman E., Moalli M.R. Comparative bone anatomy of commonly used laboratory animals: implications for drug discovery. Comp. Med. 2011;61(1):76–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravosa M.J. Plasticity of mandibular biomineralization in myostatin-deficient mice. J. Morphol. 2007;268(3):275–282. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teixeira C.C. Cytokine expression and accelerated tooth movement. J. Dent. Res. 2010;89(10):1135–1141. doi: 10.1177/0022034510373764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka M. Effect of Reveromycin A on experimental tooth movement in OPG−/− mice. J. Dent. Res. 2012;91(8):771–776. doi: 10.1177/0022034512451026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang P.C. Patterns of diabetic periodontal wound repair: a study using micro-computed tomography and immunohistochemistry. J. Periodontol. 2012;83(5):644–652. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.110325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilkenny C. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2010;1(2):94–99. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.72351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vignoletti F., Abrahamsson I. Quality of reporting of experimental research in implant dentistry. Critical aspects in design, outcome assessment and model validation. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012;39(Suppl. 12):6–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka E. Effect of food consistency on the degree of mineralization in the rat mandible. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2007;35(9):1617–1621. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9330-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao N. Local osteoprotegerin gene transfer inhibits relapse of orthodontic tooth movement. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2012;141(1):30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao N. Effects of local osteoprotegerin gene transfection on orthodontic root resorption during retention: an in vivo micro-CT analysis. Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2012;15(1):10–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2011.01532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J. Occlusal effects on longitudinal bone alterations of the temporomandibular joint. J. Dent. Res. 2013;92(3):253–259. doi: 10.1177/0022034512473482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armin B.B. Brachytherapy-mediated bone damage in a rat model investigating maxillary osteoradionecrosis. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2012;138(2):167–171. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2011.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baloul S.S. Mechanism of action and morphologic changes in the alveolar bone in response to selective alveolar decortication-facilitated tooth movement. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2011;139(4 Suppl.):S83–S101. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J. Sex differences in chondrocyte maturation in the mandibular condyle from a decreased occlusal loading model. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2011;89(2):123–129. doi: 10.1007/s00223-011-9498-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sobue T. Murine TMJ loading causes increased proliferation and chondrocyte maturation. J. Dent. Res. 2011;90(4):512–516. doi: 10.1177/0022034510390810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mavropoulos A. Rehabilitation of masticatory function improves the alveolar bone architecture of the mandible in adult rats. Bone. 2010;47(3):687–692. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen J. Analysis of microarchitectural changes in a mouse temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis model. Arch. Oral Biol. 2009;54(12):1091–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mavropoulos A., Rizzoli R., Ammann P. Different responsiveness of alveolar and tibial bone to bone loss stimuli. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2007;22(3):403–410. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicholson E.K. Biomineralization and adaptive plasticity of the temporomandibular joint in myostatin knockout mice. Arch. Oral Biol. 2006;51(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mavropoulos A. Effect of different masticatory functional and mechanical demands on the structural adaptation of the mandibular alveolar bone in young growing rats. Bone. 2004;35(1):191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bouvard B. Glucocorticoids reduce alveolar and trabecular bone in mice. Jt. Bone Spine. 2013;80(1):77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sriram D. Effects of mechanical stimuli on adaptive remodeling of condylar cartilage. J. Dent. Res. 2009;88(5):466–470. doi: 10.1177/0022034509336616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pramojanee S.N. Decreased jaw bone density and osteoblastic insulin signaling in a model of obesity. J. Dent. Res. 2013;92(6):560–565. doi: 10.1177/0022034513485600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhuang L., Bai Y., Meng X. Three-dimensional morphology of root and alveolar trabecular bone during tooth movement using micro-computed tomography. Angle Orthod. 2011;81(3):420–425. doi: 10.2319/071910-418.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X. VDR deficiency affects alveolar bone and cementum apposition in mice. Arch. Oral Biol. 2011;56(7):672–677. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kingsmill V.J. Changes in bone mineral and matrix in response to a soft diet. J. Dent. Res. 2010;89(5):510–514. doi: 10.1177/0022034510362970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Enomoto A. Effects of mastication on mandibular growth evaluated by microcomputed tomography. Eur. J. Orthod. 2010;32(1):66–70. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjp060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimizu Y. Effect of sympathetic nervous activity on alveolar bone loss induced by occlusal hypofunction in rats. Arch. Oral Biol. 2011;56(11):1404–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abbassy M.A., Watari I., Soma K. The effect of diabetes mellitus on rat mandibular bone formation and microarchitecture. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2010;118(4):364–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2010.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kozai Y. Influence of prednisolone-induced osteoporosis on bone mass and bone quality of the mandible in rats. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2009;38(1):34–41. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/28859075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheng Z.F. Zoledronate reverses mandibular bone loss in osteoprotegerin-deficient mice. Osteoporos. Int. 2009;20(1):151–159. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0640-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ames M.S. Estrogen deficiency increases variability of tissue mineral density of alveolar bone surrounding teeth. Arch. Oral Biol. 2010;55(8):599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donneys A. Quantifying mineralization using bone mineral density distribution in the mandible. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2012;23(5):1502–1506. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182519a76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuroda Y. Intermittent posterior displacement of the rat mandible in the growth period affects the condylar cancellous bone. Angle Orthod. 2011;81(6):975–982. doi: 10.2319/122810-749.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Y.Q. Dose-dependent effects of genistein on bone homeostasis in rats' mandibular subchondral bone. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2012;33(1):66–74. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiao K. Age- and sex-related changes of mandibular condylar cartilage and subchondral bone: a histomorphometric and micro-CT study in rats. Arch. Oral Biol. 2010;55(2):155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thoma D.S. Systematic review of pre-clinical models assessing implant integration in locally compromised sites and/or systemically compromised animals. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012;39(Suppl. 12):37–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]