Abstract

Objective

Vitamin D is essential for the maintenance of calcium homeostasis and bone mineralization; and low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (s-25-(OH)D) concentrations are associated with increased bone turnover. However, there is a lack of randomized controlled trials that have investigated the effect of vitamin D treatment on bone turnover in immigrant populations. We aimed to investigate the effect of 16-week daily vitamin D3 supplementation on bone formation marker serum procollagen type 1 amino-terminal propeptide (P1NP) and bone resorption marker C-terminal crosslinked telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX).

Design

Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting

Immigrant community centers in Oslo, Norway.

Participants

251 healthy adults aged 18–50 years with a non-Western immigrant background were recruited.

Intervention

16 weeks of daily oral supplementation with either 10 μg vitamin D3, 25 μg vitamin D3, or placebo.

Main outcome measures

Difference in change during the 16-week intervention between the intervention groups combined (10 or 25 μg of vitamin D3/day) and placebo, in serum P1NP and serum CTX.

Results

A total of 214 (85%) participants completed the study. S-25-(OH)D increased from 29 nmol/L at baseline to 49 nmol/L in the intervention group with no significant change in the placebo group. However, there was no difference in change of serum P1NP (mean difference: − 1.2 μg/L (95% CI: − 5.4, 2.9, P = 0.6)) and serum CTX (mean difference: − 0.005 μg/L (95% CI: − 0.03, 0.02, P = 0.7)) between those receiving vitamin D3 supplementation compared with placebo. The plasma PTH had decreased by a mean of − 1.97 pmol/L (95% CI: − 2.7, − 1.3, P < 0.0001) in the vitamin D3 group compared to placebo.

Conclusions

Supplementation with 10 or 25 μg oral vitamin D3 during winter and spring for 16 weeks did not significantly affect serum P1NP and serum CTX, despite increasing s-25(OH)D and decreasing PTH in a healthy immigrant population with low baseline vitamin D status.

Trial registration number: NCT01263288.

Keywords: Bone markers, RCT, Vitamin D supplementation, Immigrants, 25(OH)D, CTX, P1NP

1. Introduction

Vitamin D is essential for the maintenance of calcium homeostasis and bone mineralization, and low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (serum 25(OH)D) concentrations might lead to secondary hyperparathyroidism with increased bone resorption and fracture risk (Brot et al., 2001, Holick and Chen, 2008, Lips, 2001). Bone is metabolically active and is constantly being repaired and remodeled throughout an individual's lifetime (Wheater et al., 2013). A reduced rate of bone turnover may lower risk of fracture by maximizing development of peak bone mass in young adults (Slemenda et al., 1997) and slowing the rate of bone loss in later life (Riggs et al., 1998). Bone turnover markers have a potential in the prediction of osteoporosis and fracture risk (Vasikaran et al., 2011). Vitamin D deficiency is prevalent worldwide and high prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency and secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHPT) among non-Western immigrant populations living in Western countries has been reported (Islam et al., 2012, Meyer et al., 2004, Lowe et al., 2010). Recent studies in Norway have shown that in immigrants with background from Sub-Sahara Africa, Middle East and South Asia, nearly 80% had 25(OH)D < 50 nmol/L and approximately one-third had 25(OH)D < 25 nmol/L regardless of season (Eggemoen et al., 2013, Madar et al., 2009, Holvik et al., 2005). These studies suggest that the impact of vitamin D deficiency on the skeletal homeostasis of immigrants is of concern (Roy et al., 2007). High bone turnover in vitamin D deficient persons was seen in observational studies (Erkal et al., 2006, Islam et al., 2008, Macdonald et al., 2008). However, the few intervention studies examining the effect of vitamin D supplementation on bone turnover in population such as Caucasian postmenopausal women, young adults and immigrants with low vitamin status have produced mixed results (Grimnes et al., 2012, Macdonald et al., 2013, Andersen et al., 2008). A one year randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled intervention with vitamin D3 (10 and 20 μg/d) in young women and men of Pakistani origin living in Denmark showed that supplementation increased serum 25(OH)D concentrations and decreased serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) concentrations but there was no significant effect of the intervention on bone turnover markers (Andersen et al., 2008). In another randomized trial, four weeks of daily supplementation with 10 μg vitamin D3 decreased mean PTH but surprisingly increased tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (s-TRACP, which is a bone resorption marker) concentration in healthy adults 19–48 years of ethnic Norwegian and Tamil background (Holvik et al., 2012). Apart from these two RCT's, where one included only persons with Pakistani background in Denmark and in the other one the time of supplementation was only 4 weeks, we were unable to identify any other RCT's that have investigated the effect of vitamin D treatment on bone turnover in immigrant populations living in developed countries.

Various bone formation and bone resorption markers have been suggested for clinical use in the diagnosis and management of a range of metabolic bone diseases (Wheater et al., 2013). Among bone formation marker is procollagen type 1 amino-terminal propeptide (P1NP) which is released into the circulation during bone formation. While among bone resorption markers include carboxy-terminal cross-linked telopeptide of type 1 collagen (CTX). CTX is a degradation product of type 1 collagen and is released into the circulation during bone resorption (Vasikaran et al., 2011). The Bone Marker Standards Working Group recommends P1NP and CTX as reference standard markers of bone formation and resorption (Vasikaran et al., 2011, Stokes et al., 2011).

We therefore wanted to test the effect of vitamin D supplementation on bone markers in winter time, because bone turnover markers have a potential in the prediction of osteoporosis and fracture risk. We hypothesized that the improvement of low vitamin D status in immigrant population will affect their bone markers. The aim of the present study was, whether 16 weeks of daily vitamin D3 supplementation (10 or 25 μg/d vs placebo) would affect biochemical markers of bone formation (serum P1NP) and resorption (serum CTX) in a multi-ethnic immigrant population in late wintertime.

2. Research design and methods

2.1. Study design and participants

The present work describes predefined additional endpoints of a 16-week intervention trial with vitamin D supplementation versus placebo and was performed as previously described in detail (Knutsen et al., 2014). In brief, healthy men and women, aged 18–50 years, who were born or had parents born in Middle East, Africa and South Asia, were recruited through 11 different community centers in Oslo and surrounding areas (at latitude 60°N). The exclusion criteria were; regular use of vitamin D-containing supplements, on-going treatment for vitamin D deficiency, pregnancy, breastfeeding, mal-absorption, use of medication that interfered with vitamin D metabolism (thiazides, anti-epileptics, prednisolone or hormone replacement therapy), kidney diseases, cancer, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, osteoporosis or recent fracture. All the female participants were younger than 50 years old (when menopause normally starts), but they were not asked about menopausal status or current use of oral contraceptions. The same data collection team visited all the centers and performed the baseline and follow-up data collection. Interpreters were used when necessary, but the majority of the study participants were able to communicate in Norwegian language.

2.2. Randomization and intervention

Those who fulfilled the eligibility criteria were randomly assigned to one of three equally sized intervention groups receiving one tablet per day containing 25 μg vitamin D3, 10 μg vitamin D3 or placebo. The tablets were similar in color, size and packing. Each participant was given a box containing 120 tablets (16 week use corresponds to 112 tablets) at baseline. The tablets were manufactured by Bio Plus Life sciences PVT LTD, DMA (Bangalore, India), certified for Good Manufacturing Practice and the ingredients met the requirements of British Pharmacopé. If the study subjects had forgotten to take one tablet one day, they were asked to take two tablets the following day. Participants were followed up with a short text message twice a week to remind them to take the tablets. Subjects were advised to maintain their usual dietary pattern during the 16 week trial period and advised to contact the study staff by telephone if they had any queries.

2.3. Main outcome variables

The study outcomes were difference in absolute change during the 16 week intervention between the pooled intervention groups (10 or 25 μg of vitamin D3/d) and placebo for bone markers: serum P1NP (s-P1NP) and serum CTX (s-CTX).

2.4. Random allocation

We chose a computer-generated block randomization to ensure a good balance of the number in each group during the trial and randomly varying the block size between 3 and 6.

2.5. Blinding

Group allocation was unknown to participants, research staff, investigators, and data collectors. The tablet boxes were numbered according to the randomization list by an external pharmacy (the Hospital Pharmacy at Oslo University Hospital). The group allocation list was stored at this pharmacy with a copy in a sealed envelope. Each participant was consecutively numbered and received a pre-packaged tablet box with the corresponding number.

2.6. Registration

The study was authorized as a clinical trial by the Norwegian Medicine Agency and approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (study code: 2010/1982). All participants gave written informed consent.

The study has been registered at EudraCT (2010-021114-36). The clinical trial was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with national laws. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01263288.

2.7. Blood sampling and laboratory assays

Non-fasted venous blood samples were collected after 9 am (and before 16.00 for the majority of the samples) and at roughly the same time of day for each participant's visit at baseline and at follow-up. Blood for serum was collected in serum-separator gel tubes and centrifuged after 30 min to 2 h, and blood for plasma was collected in EDTA-tubes and centrifuged within 30 min at room temperature at the study site. Serum and plasma were separated and frozen in several aliquots (separate tubes for bone markers) at − 20 °C for some days and transported on dry ice less than 1 h and stored at − 80 °C at Fürst Medical Laboratory in Oslo (www.furst.no) until they were analyzed. After the completion of the study all samples from baseline and follow-up were analyzed in one batch at Fürst Medical Laboratory (www.furst.no), which is accredited by the International Organization for Standardization and is part of vitamin D quality assessment scheme, DEQAS.

Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) was measured using high-pressure liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC–MS–MS), with Waters Acquity UPLC and Waters trippelquadrupole MS instruments. In house standards at four levels ranging from 25 to 200 nmol/L were calibrated against external MS-standards from Recipe (Germany), product no. MS7013, traceable to NIST. Deuterized internal standard 26,27 hexadeuterium labeled 25(OH)D3, purchased from Synthetica (Norway), was used in the calculation of both 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3. The CV (reproducibility within the laboratory, 4 instruments) for serum 25(OH)D3 was 8% at concentrations of 55.2 nmol/L and 6% at concentrations of 195.1 nmol/L. The CV for serum 25(OH)D2 was 11% at concentrations of 43.8 nmol/L and 9% at concentrations of 158.5 nmol/L. In the analysis the term 25(OH)D) is used for the sum of 25(OH)D2 and -D3, but note that the contribution of 25(OH)D2 was negligible.

Plasma PTH was analyzed with Advia Centaur XP (Siemens HMSD) with analytical coefficient of variation of 8.2% and reference range of 1.2–8.4 pmol/L. Serum concentrations of calcium (mmol/L), albumin (g/L), and phosphate were measured using Advia 2400 (Siemens) and corrected calcium (mmol/L) was calculated as s-calcium − 0.02 × (s-albumin − 41.3).

The serum planned for the analyses of bone markers which were stored in a separate sample series (tubes 1 mL) was transferred on dry ice (not defrosted allowed to thaw) and stored at − 80 °C at Hormone Laboratory, Oslo University Hospital. CTX and P1NP were analyzed in a single batch. The bone resorption marker CTX and the bone formation marker P1NP in serum were measured by electro-chemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) (Roche MODULAR Analytics E170 from Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The reference range for women in childbearing age and men is < 0.57 μg/L and total analytical CV was ≤ 3% for CTX. The reference range for women in childbearing age is (11–94 μg/L) and for men is (20–91 μg/L) for P1NP and total CV was ≤ 4%. The Hormone Laboratory participates in Labquality and UK NEQAS. CTX has a diurnal variation with a maximum peak early in the morning (05:00–08:00); and declining late in the afternoon.

2.8. Statistical analysis

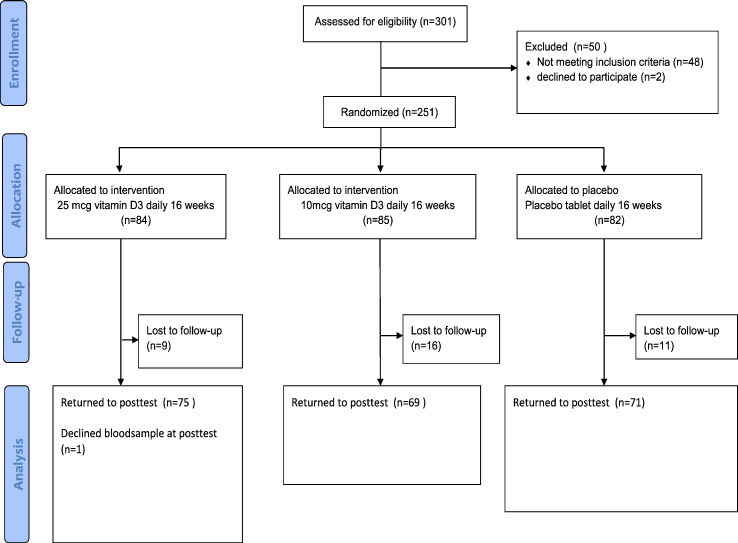

Sample size calculations based on the expected effect on the primary end point of the study, muscle strength (Knutsen et al., 2014), indicated that 210 subjects were required (70 in each group), with recruitment of 250 subjects to account for expected withdrawals (Fig. 1). Statistical analysis of the data was performed using the IBM SPSS statistical software (version 19.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For each of the outcome variables, we calculated the difference in change from baseline to follow-up between intervention groups and the placebo group using linear regression analysis. Also the effect on each outcome variable was adjusted for the respective baseline concentration. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Subgroup analyses by baseline values of endpoint measures, geographic background, and gender and intervention dose were also performed.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of recruitment, randomization and follow-up.

3. Results

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the 214 study participants who completed the study. There was no major difference in subject characteristics between the three groups. The kidney and liver function tests were normal in the study participants. Also, there was no significant difference in the characteristics of the 37 participants who did not complete the study compared to those who completed the study (data not shown). The mean age of the study participants was 37.6 ± 7.8, and 79% were female. Mean serum 25(OH)D was 28.9 nmol/L (SD 17.6) for the whole group and over 30% had PTH levels above the upper limit of the reference value (1.2–8.4 pmol/L). There were 21 (9.8%) persons with serum 25(OH)D below 12.5 nmol and these had a mean PTH of 9.9 pmol/L (SD 6.5) and a mean calcium of 2.35 mmol/L (SD 0.1). At baseline around 90% and 53% of the participants had s-25(OH)D levels below 50 nmol/L and 25 nmol/L respectively. There was no correlation between serum 25(OH)D values and serum CTX or serum P1NP at baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for the 214 study subjects who completed the study.a

| Characteristics | Placebo |

Vitamin D (10 μg) |

Vitamin D (25 μg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 71 | N = 69 | N = 74 | |

| Age (years) | 39 (7.4) | 37 (7.4) | 37 (8.2) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 15 (21%) | 18 (26%) | 23 (31%) |

| Female | 56 (79%) | 51 (74%) | 51 (69%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.1 (5.2) | 27.2 (4.9) | 26.6 (5.1) |

| Ethnic origin (n, %) | |||

| South Asia | 27 (38%) | 25 (36%) | 29 (39%) |

| Middle East & North Africa | 12 (17%) | 7 (10%) | 12 (16%) |

| Sub-Sahara Africa | 32 (45%) | 37 (54%) | 33 (45%) |

| Time lived in Norway (years) | 13.6 (2–33) | 13.2 (1–35) | 13.3 (1–29) |

| Level of education (n, %) | |||

| ≤ 10 years | 30 (42%) | 29 (42%) | 29 (39%) |

| 11–13 years | 26 (37%) | 26 (38%) | 26 (35%) |

| ≥ 14 years | 15 (21%) | 14 (20%) | 19 (26%) |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L)b | 56.1 (11.6) | 56.4 (14.6) | 56.6 (12.5) |

| Serum alanine transaminase (u/L) c | 22.3 (12.3) | 22.9 (11.9) | 21.7 (12.1) |

| Serum aspartate aminotransferase (u/L)d | 20.1 (6.6) | 21.0 (6.6) | 19.9 (6.7) |

| Total S-25(OH)D (nmol/L) | 29.2 (15.6) | 30.7 (20.1) | 26.8 (17.1) |

| Serum 25(OH)D3 (nmol/L) | 26.9 (15.1) | 27.2 (15.1) | 26.8 (17.1) |

| Serum 25(OH)D2 (nmol/L) | 2.3 (8.6) | 3.5 (13.5) | 0 |

| Serum calcium (mmol/L)e | 2.36 (0.10) | 2.37 (0.08) | 2.37 (0.09) |

| Serum corrected calcium (mmol/L) | 2.30 (0.08) | 2.31 (0.06) | 2.32 (0.08) |

| Serum phosphate (mmol/L)e | 1.15 (0.15) | 1.16 (0.16) | 1.13 (0.13) |

| Plasma PTH (pmol/L)f | 8.1 (4.0) | 7.1 (3.5) | 7.6 (3.8) |

| Serum P1NP (μg/L) | 44.8 (16.0) | 47.1 (17.4) | 49.0 (26.0) |

| Serum CTX-1(μg/L) | 0.19 (0.10) | 0.20 (0.10) | 0.19 (0.13) |

The mean of s-25(OH)D was 31.3 and 44 nmol/L for males and females respectively.

Data are mean (standard deviation) unless specified otherwise.

None were above the reference range (males 60–105, females 45–90 μmol/L).

3 males and 2 females have above the reference limit (men < 70, women < 45 U/L).

1 male and 1 female have above the reference limit (men < 45, women < 35 U/L).

Reference range for s-calcium (2.15–2.51 mmol/L) and for s-phosphate (women > 18 years: 0.85–1.50 mmol/L and men 18–49 years: 0.75–1.65 mmol/L).

N = 69 for placebo, 66 for 10 and 74 for 25 μg group due to 5 missing data.

3.1. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on serum 25(OH)D, calcium, albumin-corrected-calcium and plasma phosphate

As previously reported (Knutsen et al., 2014), following the intervention mean serum 25(OH)D had increased by a mean of 17 and 26 nmol/L, respectively for the 10 μg and 25 μg vitamin D3 groups, compared to placebo (Table 2). There was no change in calcium, albumin-corrected calcium or phosphate as a result of vitamin D supplementation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of intervention with vitamin D supplementationa s-P1NP and s-CTX, s-25(OH)D3, p-PTH, s-calcium and s-phosphate.

| Baselineb | After 16 weeksb | Difference in change (95% CI)b compared to placebo | P values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum 25(OHD) (nmol/L) | ||||

| Intervention (n = 143) | 28.7 (18.6) | 48.8 (19.6) | 21.3 (16.7, 26.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Placebo (n = 71) | 29.2 (15.6) | 27.5 (13.7) | ||

| Serum calcium (mmol/L) | ||||

| Intervention (n = 143) | 2.4 (0.10) | 2.37 (0.1) | − 0.005 (− 0.03, 0.02) | 0.7 |

| Placebo (n = 71) | 2.4 (0.09) | 2.36 (0.1) | ||

| Serum corrected calcium (mmol/L)c | ||||

| Intervention (n = 143) | 2.36 (0.08) | 2.34 (0.1) | − 0.007 (− 0.03, 0.02) | 0.5 |

| Placebo (n = 71) | 2.35 (0.1) | 2.34 (0.09) | ||

| Serum phosphate (mmol/L) | ||||

| Intervention (n = 143) | 1.14 (0.15) | 1.15 (0.16) | 0.01 (− 0.03, 0.05) | 0.5 |

| Placebo (n = 71) | 1.15 (0.14) | 1.14 (0.16) | ||

| Plasma PTH (pmol/L) | ||||

| Intervention (n = 140) | 7.4 (3.7) | 6.1 (2.3) | − 1.97 (− 2.7, − 1.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Placebo (n = 69) | 8.1 (4.0) | 8.2 (3.9) | ||

| Bone turnover markers | ||||

| Serum P1NP (μg/L) | ||||

| Intervention (n = 143) | 47.9 (22) | 46.9 (23) | − 1.2 (− 5.4, 2.9) | 0.6 |

| Placebo (n = 71) | 44.8 (16) | 45.3 (25) | ||

| Serum CTX-1 (μg/L) | ||||

| Intervention (n = 143) | 0.19 (0.11) | 0.20 (0.1) | − 0.005 (− 0.03, 0.02) | 0.7 |

| Placebo (n = 71) | 0.19 (0.1) | 0.20 (0.1) | ||

Combined 10 and 25 μg doses.

Adjusted for baseline values.

Corrected for serum albumin.

3.2. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on bone turnover markers and plasma PTH

A 16-week supplementation with vitamin D3 (10 or 25 μg combined) compared to placebo had no significant effect on serum CTX and serum P1NP (Table 2), and the difference in percentage change was − 0.7% (95% CI: − 7.8 to 6.5, P = 0.8) for P1NP and − 6.1% (95% CI: − 25.8 to 13.4, P = 0.5) for s-CTX. As reported earlier (Knutsen et al., 2014), plasma PTH decreased by a mean of −1.97 pmol/L (95% CI: − 2.7, − 1.3, P < 0.0001) with vitamin D3 (10 or 25 μg combined) compared to placebo.

We also analyzed the effect of the two interventions (10 and 25 μg) separately, and none of them had a significant effect on serum CTX or serum P1NP (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of intervention with vitamin D supplementationa on serum P1NP, serum CTX, serum 25(OH)D3, plasma PTH, serum calcium and serum phosphate.

| Baseline |

Final (after 16 weeks) |

Difference in change (95% CI)d |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | 10 μg | 25 μg | Placebo | 10 μg | 25 μg | 10 μg | 25 μg | |

| Serum 25(OHD) (nmol/L) | 29.2 (15.6) | 30.7 (20.1) | 26.8 (17.1) | 27.5 (13.7) | 45.9 (18.7) | 51.1 (20.1) | 16.7 (11.2, 22.3)‡ | 26.1 (20.4, 31.9)‡ |

| Serum calcium (mmol/L) | 2.36 (0.1) | 2.37 (0.08) | 2.37 (0.09) | 2.36 (0.11) | 2.35 (0.13) | 2.38 (0.10) | − 0.02 (− 0.06, 0.01) | 0.003 (− 0.02, 0.03) |

| Serum corrected calcium (mmol/L)b | 2.30 (0.08) | 2.31 (0.06) | 2.32 (0.08) | 2.34 (0.10) | 2.32 (0.11) | 2.33 (0.10) | − 0.02 (− 0.05, 0.01) | − 0.003 (− 0.02, 0.02) |

| Serum phosphate (mmol/L) | 1.15 (0.15) | 1.16 (0.16) | 1.13 (0.13) | 1.14 (0.18) | 1.15 (0.16) | 1.15 (0.16) | − 0.002 (− 0.05, 0.05) | 0.04 (− 0.01, 0.08) |

| Plasma PTH (pmol/L)c | 8.1 (4.0) | 7.1 (3.5) | 7.6 (3.8) | 8.2 (3.9) | 6.1 (2.1) | 6.1 (2.5) | − 1.6 (− 2.6, − 0.6)‡ | − 1.97 (− 3.0, − 0.9)‡ |

| Bone turnover markers | ||||||||

| Serum P1NP (μg/L) | 44.8 (16.0) | 47.1 (17.4) | 49.0 (26.0) | 46.3 (25.0) | 46.6 (17.9) | 47.6 (26.5) | − 1.0 (− 6.0, 4.0) | − 1.5 (− 3.0, 2.7) |

| Serum CTX-1 (μg/L) | 0.19 (0.10) | 0.20 (0.10) | 0.19 (0.13) | 0.20 (0.11) | 0.20 (0.10) | 0.21 (0.11) | − 0.01 (− 0.05, 0.02) | − 0.004 (− 0.04, 0.03) |

10 and 25 μg doses separately.

Corrected for serum albumin.

n = 69 for placebo, 68 for 10 and 74 for 25 μg group.

Difference in change comparing to placebo.

P < 0.001, PTH difference between placebo in 10 μg group, P = 0.002.

3.3. Additional analyses

There was no difference in the effect of vitamin D supplementation on serum CTX or serum P1NP when adjusted for geographical background. Furthermore, there were no significant differences between the combined intervention groups and placebo in any of the end points after stratification by baseline concentration of serum 25(OH)D higher or lower than 25 nmol/L, or after stratification by gender, BMI and age (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of vitamin D supplementation on serum P1NP and serum CTX in subgroups.a

| Sub-groups | Serum P1NP |

Serum CTX |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect estimate (95% CI) | P | Effect estimate (95% CI) | P | |

| 25(OH)D (nmol/L) | ||||

| < 25 (n = 113) | − 3.9 (− 11.0, 3.3) | 0.3 | 0.002 (− 0.04, 0.04) | 0.9 |

| ≥ 25 (n = 101) | 1.8 (− 2.3, 5.8) | 0.4 | − 0.007 (− 0.04, 0.03) | 0.7 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female (n = 158) | − 0.16 (− 3.6, 3.3) | 0.9 | 0.00 (− 0.30, 0.29) | 0.9 |

| Male (n = 56) | − 4.9 (− 16.7, 6.8) | 0.4 | − 0.04 (− 0.1, 0.24) | 0.2 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| < 40 (n = 102) | − 5.5 (− 13.0, 2.0) | 0.1 | − 0.01 (− 0.05, 0.03) | 0.7 |

| ≥ 40 (n = 112) | 2.9 (− 0.7, 6.7) | 0.1 | − 0.003 (− 0.04, 0.03) | 0.8 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| < 27 (n = 114) | − 3.7 (− 11.6, 4.2) | 0.4 | 0.002 (− 0.04, 0.05) | 0.9 |

| ≥ 27 (n = 100) | − 0.2 (− 3.9, 3.5) | 0.9 | − 0.02 (− 0.05, 0.02) | 0.3 |

| Regional backgroundb | ||||

| South Asia (n = 81) | 3.8 (− 0.2, 7.7) | 0.06 | 0.006 (− 0.03, 0.05) | 0.7 |

| Middle East, North Africa (n = 31) | − 1.1 (− 6.6, 4.5) | 0.7 | − 0.01 (− 0.08, 0.06) | 0.8 |

| Africa south for Sahara (n = 102) | − 5.8 (− 13.8, 2.3) | 0.2 | − 0.01 (− 0.05, 0.03) | 0.5 |

Effect estimates for each outcome variable are difference in change from baseline to 16 weeks between the combined intervention groups (10 or 25 μg) and the placebo group.

South Asia (Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka), Middle East, North Africa (Iraq, Syria, Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia), and Africa south for Sahara (Somalia, Ethiopia, Eretria, Ghana, Gambia).

3.4. Compliance

Compliance with supplementation was confirmed by counting the number of tablets in the returned tablet boxes, where 80% had consumed more than 80% of the tablets and 69% had consumed more than 90% of the tablets.

4. Discussion

In this double blinded randomized controlled trial in a healthy immigrant population, daily supplementation with either 10 μg or 25 μg vitamin D3 over 16 weeks had no effect on the bone turnover markers P1NP and CTX, despite increased serum 25(OH)D and PTH suppression.

Few studies have studied the effect of vitamin D supplementation on bone markers in immigrant background. Our findings are in agreement with the results from a randomized controlled study of Pakistani immigrants in Denmark (n = 199, 13–53 years) who were supplemented with 10 μg and 20 μg vitamin D3 per day (Andersen et al., 2008). Despite the observed increased serum 25(OH)D and decreased PTH concentrations, the treatment had no effect on any of the bone turnover markers (serum osteocalcin, urinary pyridinoline and urinary deoxypyridinoline). In another study in which Tamils and native Norwegian subjects (n = 55, 18–48 years) were given daily supplementation with 10 μg vitamin D3 in four weeks, there was a decrease in mean PTH, and an increase in the bone resorption s-TRACP in both groups. It was suggested that the increase in bone resorption activity, in spite of the improvement in vitamin D status and corresponding PTH suppression, was explained partly by the young age of the participants and by the fact that bone resorption and formation are coupled processes, so that increased bone formation would be likely to follow the increase in resorption (Holvik et al., 2012). The age range of our participants (18–50 years) and the baseline vitamin D status were similar to those in the above study but our study had a longer intervention period.

In studies involving young Caucasian adults with marginal vitamin D deficiency, no beneficial effects of vitamin D on bone markers have been observed (Barnes et al., 2006, Seamans et al., 2010, Aloia et al., 2010, Trautvetter et al., 2014).

Observational studies investigating the relationship between vitamin D status and bone turnover in South Asian populations residing in Norway are consistent with our findings. For example, a comparative study of Pakistani and Norwegian women living in Oslo (n = 720) reported that hyperparathyroidism coupled with low vitamin D status in the Pakistani women was not associated with increased bone turnover and that they had similar bone mineral density (BMD) to the ethnic Norwegians (Holvik et al., 2006). Skeletal resistance to PTH-stimulated bone resorption has been described in non-white populations (Cosman et al., 1997) and may provide a mechanism by which non-white populations with suboptimal serum 25(OH)D levels retain BMD. It has been suggested that PTH has a limited role in defining vitamin D status in individual patients and in guiding vitamin D therapy in clinical practice (Shibli-Rahhal and Paturi, 2014). However, the clinical importance of persistent vitamin D deprivation and PTH elevation in immigrant men and women should be further explored.

The strengths of this study were that it was a strictly performed double blinded randomized placebo controlled trial, it had good compliance and relatively high retention. Assessments were performed during winter and spring, a time when sun exposure has little impact on vitamin D synthesis, and all blood samples were assayed in a single batch. The ethnic minorities targeted in our study are known to have generally poor vitamin D status. The doses used were sufficient to increase the serum 25(OH)D levels, however 50 nmol/L was not reached in 43% (25 μg supplementation group) and 62% (10 μg supplementation group). The study also had some limitations. For instance, although the analyses of bone markers were pre-planned the study was designed primarily for muscular strength outcomes. Assuming an SD 17.4 μg/L for P1NP and 0.10 μg/L for CTX, 70 participants per group would have been sufficient to detect differences of 8.3 μg/L in P1NP (equivalent to 17% change); and 0.048 μg/L in CTX (equivalent to 24% change), respectively. Although larger sample sizes might have provided more power to detect smaller differences, the non-significant changes we observed in this study were very small (− 0.7% for P1NP and − 6% for CTX) and of doubtful clinical relevance.

We did not calculate the dietary intake of calcium of the study subjects and it is possible that this was sufficient to suppress bone turnover. In addition, the duration of the study might not have been long enough for participants to achieve sufficiently high serum 25(OH)D levels for long enough to allow detection of significant changes in the endpoints. A longer intervention period would have been desirable, but continuing the trial into summer could have influenced the results through cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D with sun exposure, and might have resulted in loss to follow-up. Another limitation is that the levels of bone markers especially serum CTX exhibit a circadian rhythm and are influenced by time of blood collection and fasting status (Herrmann and Seibel, 2008) and may be attenuated by other factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, menopausal status and food intake (Wheater et al., 2013, Clowes et al., 2002, Jenkins et al., 2013). Therefore, these values need to be interpreted with caution, keeping in mind that they were obtained from non-fasting study participants.

However, in order to address these problems, participants were seen at roughly the same time of the day and analysis was done in one batch.

There is a lack of age and gender specific serum reference intervals for P1NP and CTX in non-white populations, both in their native countries and for immigrant populations. Collection of data from healthy non-white populations would be helpful in order to establish appropriate reference ranges which can be used to aid interpretation when making comparisons between different ethnic groups.

5. Conclusions

Supplementation with daily 10 or 25 μg oral vitamin D3 per day during winter for 16 weeks did not affect bone turnover markers in a healthy immigrant population living in Norway, with low baseline vitamin D status, despite significantly decreased PTH levels in both intervention groups.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Eva Kristensen and Morten Ariansen for their help with data collection, Anne Karen Jenum for the bio bank support, Marie Buchmann and Anne-Lise Sund at Fürst Medical Laboratory for facilitating the laboratory analyses, and Svein Gjelstad for his assistance in data management. Finally, we extend our gratitude to the study participants who participated in this 16-week trial and those organizations who allowed us to use their venues for recruitment and data collection.

Funding

The study was funded by Norwegian Women's Public Health Association and the University of Oslo. It was also supported by the Fürst Medical Laboratory and by Nycomed Pharma AS. None of the supporting bodies had any influence on the performance of the trial, analyses of data, writing, or the publication of the results.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier:

References

- Aloia J., Bojadzievski T., Yusupov E., Shahzad G., Pollack S., Mikhail M. The relative influence of calcium intake and vitamin D status on serum parathyroid hormone and bone turnover biomarkers in a double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel group, longitudinal factorial design. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;95(7):3216–3224. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen R., Molgaard C., Skovgaard L.T., Brot C., Cashman K.D., Jakobsen J. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on bone and vitamin D status among Pakistani immigrants in Denmark: a randomised double-blinded placebo-controlled intervention study. Br. J. Nutr. 2008;100(1):197–207. doi: 10.1017/S000711450789430X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes M.S., Robson P.J., Bonham M.P., Strain J.J., Wallace J.M. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on vitamin D status and bone turnover markers in young adults. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006;60(6):727–733. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brot C., Vestergaard P., Kolthoff N., Gram J., Hermann A.P., Sorensen O.H. Vitamin D status and its adequacy in healthy Danish perimenopausal women: relationships to dietary intake, sun exposure and serum parathyroid hormone. Br. J. Nutr. 2001;86(Suppl. 1):S97–S103. doi: 10.1079/bjn2001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowes J.A., Hannon R.A., Yap T.S., Hoyle N.R., Blumsohn A., Eastell R. Effect of feeding on bone turnover markers and its impact on biological variability of measurements. Bone. 2002;30(6):886–890. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00728-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosman F., Morgan D.C., Nieves J.W., Shen V., Luckey M.M., Dempster D.W. Resistance to bone resorbing effects of PTH in black women. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 1997;12(6):958–966. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.6.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggemoen A.R., Knutsen K.V., Dalen I., Jenum A.K. Vitamin D status in recently arrived immigrants from Africa and Asia: a cross-sectional study from Norway of children, adolescents and adults. BMJ Open. 2013;3(10):e003293. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkal M.Z., Wilde J., Bilgin Y., Akinci A., Demir E., Bodeker R.H. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, secondary hyperparathyroidism and generalized bone pain in Turkish immigrants in Germany: identification of risk factors. Osteoporos. Int. 2006;17(8):1133–1140. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimnes G., Joakimsen R., Figenschau Y., Torjesen P.A., Almas B., Jorde R. The effect of high-dose vitamin D on bone mineral density and bone turnover markers in postmenopausal women with low bone mass—a randomized controlled 1-year trial. Osteoporos. Int. 2012;23(1):201–211. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1752-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann M., Seibel M.J. The amino- and carboxyterminal cross-linked telopeptides of collagen type I, NTX-I and CTX-I: a comparative review. Clin. Chim. Acta Int. J. Clin. Chem. 2008;393(2):57–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick M.F., Chen T.C. Vitamin D deficiency: a worldwide problem with health consequences. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008;87(4):1080S–1086S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.4.1080S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holvik K., Meyer H.E., Haug E., Brunvand L. Prevalence and predictors of vitamin D deficiency in five immigrant groups living in Oslo, Norway: the Oslo Immigrant Health Study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005;59(1):57–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holvik K., Meyer H.E., Sogaard A.J., Selmer R., Haug E., Falch J.A. Biochemical markers of bone turnover and their relation to forearm bone mineral density in persons of Pakistani and Norwegian background living in Oslo, Norway: The Oslo Health Study. Eur. J. Endocrinol./Eur. Fed. Endocr. Soc. 2006;155(5):693–699. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holvik K., Madar A.A., Meyer H.E., Lofthus C.M., Stene L.C. Changes in the vitamin D endocrine system and bone turnover after oral vitamin D3 supplementation in healthy adults: results of a randomised trial. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2012;12:7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-12-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M.Z., Shamim A.A., Kemi V., Nevanlinna A., Akhtaruzzaman M., Laaksonen M. Vitamin D deficiency and low bone status in adult female garment factory workers in Bangladesh. Br. J. Nutr. 2008;99(6):1322–1329. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508894445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M.Z., Viljakainen H.T., Karkkainen M.U., Saarnio E., Laitinen K., Lamberg-Allardt C. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and secondary hyperparathyroidism during winter in pre-menopausal Bangladeshi and Somali immigrant and ethnic Finnish women: associations with forearm bone mineral density. Br. J. Nutr. 2012;107(2):277–283. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511002893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins N., Black M., Paul E., Pasco J.A., Kotowicz M.A., Schneider H.G. Age-related reference intervals for bone turnover markers from an Australian reference population. Bone. 2013;55(2):271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutsen K.V., Madar A.A., Lagerlov P., Brekke M., Raastad T., Stene L.C. Does vitamin D improve muscle strength in adults? A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial among ethnic minorities in Norway. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;99(1):194–202. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lips P. Vitamin D, deficiency and secondary hyperparathyroidism in the elderly: consequences for bone loss and fractures and therapeutic implications. Endocr. Rev. 2001;22(4):477–501. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.4.0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe N.M., Mitra S.R., Foster P.C., Bhojani I., McCann J.F. Vitamin D status and markers of bone turnover in Caucasian and South Asian postmenopausal women living in the UK. Br. J. Nutr. 2010;103(12):1706–1710. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509993850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald H.M., Mavroeidi A., Barr R.J., Black A.J., Fraser W.D., Reid D.M. Vitamin D status in postmenopausal women living at higher latitudes in the UK in relation to bone health, overweight, sunlight exposure and dietary vitamin D. Bone. 2008;42(5):996–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald H.M., Wood A.D., Aucott L.S., Black A.J., Fraser W.D., Mavroeidi A. Hip bone loss is attenuated with 1000 IU but not 400 IU daily vitamin D3: a 1-year double-blind RCT in postmenopausal women. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 2013;28(10):2202–2213. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madar A.A., Stene L.C., Meyer H.E. Vitamin D status among immigrant mothers from Pakistan, Turkey and Somalia and their infants attending child health clinics in Norway. Br. J. Nutr. 2009;101(7):1052–1058. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508055712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer H.E., Falch J.A., Sogaard A.J., Haug E. Vitamin D deficiency and secondary hyperparathyroidism and the association with bone mineral density in persons with Pakistani and Norwegian background living in Oslo, Norway, The Oslo Health Study. Bone. 2004;35(2):412–417. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs B.L., O'Fallon W.M., Muhs J., O'Connor M.K., Kumar R., Melton L.J., 3rd. Long-term effects of calcium supplementation on serum parathyroid hormone level, bone turnover, and bone loss in elderly women. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 1998;13(2):168–174. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy D.K., Berry J.L., Pye S.R., Adams J.E., Swarbrick C.M., King Y. Vitamin D status and bone mass in UK South Asian women. Bone. 2007;40(1):200–204. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seamans K.M., Hill T.R., Wallace J.M., Horigan G., Lucey A.J., Barnes M.S. Cholecalciferol supplementation throughout winter does not affect markers of bone turnover in healthy young and elderly adults. J. Nutr. 2010;140(3):454–460. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.113480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibli-Rahhal A., Paturi B. Variations in parathyroid hormone concentration in patients with low 25 hydroxyvitamin D. Osteoporos. Int. 2014;25(7):1931–1936. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2687-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slemenda C.W., Peacock M., Hui S., Zhou L., Johnston C.C. Reduced rates of skeletal remodeling are associated with increased bone mineral density during the development of peak skeletal mass. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 1997;12(4):676–682. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes F.J., Ivanov P., Bailey L.M., Fraser W.D. The effects of sampling procedures and storage conditions on short-term stability of blood-based biochemical markers of bone metabolism. Clin. Chem. 2011;57(1):138–140. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.157289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trautvetter U., Neef N., Leiterer M., Kiehntopf M., Kratzsch J., Jahreis G. Effect of calcium phosphate and vitamin D(3) supplementation on bone remodelling and metabolism of calcium, phosphorus, magnesium and iron. Nutr. J. 2014;13:6. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-13-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasikaran S., Eastell R., Bruyere O., Foldes A.J., Garnero P., Griesmacher A. Markers of bone turnover for the prediction of fracture risk and monitoring of osteoporosis treatment: a need for international reference standards. Osteoporos. Int. 2011;22(2):391–420. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1501-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheater G., Elshahaly M., Tuck S.P., Datta H.K., van Laar J.M. The clinical utility of bone marker measurements in osteoporosis. J. Transl. Med. 2013;11:201. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]