Abstract

Objective:

Intra-abdominal fat is a risk factor for pancreatic cancer (PC), but little is known about its contribution to PC precursors known as intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs). Our goal was to evaluate quantitative radiologic measures of abdominal/visceral obesity as possible diagnostic markers of IPMN severity/pathology.

Methods:

In a cohort of 34 surgically-resected, pathologically-confirmed IPMNs (17 benign; 17 malignant) with preoperative abdominal computed tomography (CT) images, we calculated body mass index (BMI) and four radiologic measures of obesity: total abdominal fat (TAF) area, visceral fat area (VFA), subcutaneous fat area (SFA), and visceral to subcutaneous fat ratio (V/S). Measures were compared between groups using Wilcoxon two-sample exact tests and other metrics.

Results:

Mean BMI for individuals with malignant IPMNs (28.9 kg/m2) was higher than mean BMI for those with benign IPMNs (25.8 kg/m2) (P=0.045). Mean VFA was higher for patients with malignant IPMNs (199.3 cm2) compared to benign IPMNs (120.4 cm2),P=0.092. V/S was significantly higher (P=0.013) for patients with malignant versus benign IPMNs (1.25vs. 0.69 cm2), especially among females. The accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive value of V/S in predicting malignant IPMN pathology were 74%, 71%, 76%, 75%, and 72%, respectively.

Conclusions:

Preliminary findings suggest measures of visceral fat from routine medical images may help predict IPMN pathology, acting as potential noninvasive diagnostic adjuncts for management and targets for intervention that may be more biologically-relevant than BMI. Further investigation of gender-specific associations in larger, prospective IPMN cohorts is warranted to validate and expand upon these observations.

Keywords: Abdominal obesity, pre-malignant lesions, pancreatic cancer, computed tomography

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), commonly known as pancreatic cancer (PC), is the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths world-wide, with high age-standardized incidence rates occurring in North America and Asia1. PC is diagnosed in more than 337,000 individuals each year, accounts for 4% of all cancer deaths, and has the lowest five-year relative survival rate of all leading cancers, at 9%1. Prognosis is poor because diagnosis typically occurs at a late, incurable stage, and prevention and early detection methods are lacking1. Risk factors including age, tobacco, diabetes, pancreatitis, heavy alcohol use, family history, and hereditary conditions explain only a proportion of PCs1. Being overweight [body mass index (BMI)≥25 kg/m2] or obese (BMI≥30 kg/m2) increases PC risk by 30%2, has a population attributable fraction up to 16%3, and influences PC survival4-6. Given the rise in the prevalence of obesity in North America and Asia7,8 and the fact that obesity is a modifiable PC risk factor, an understanding of obesity’s role in early pancreatic carcinogenesis is crucial for PC prevention and early detection. We contend that commonly-detected PC precursors may be attributed to obesity, and that proper diagnosis and treatment of precursors and underlying obesity offer potential to reduce PC burden.

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) are macrocystic PC precursors (‘precancers’) that comprise half of the ~150,000 pancreatic cysts detected incidentally in 3% of computed tomography (CT) scans and 20% of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies each year9,10, making them more amenable to study than the microscopic PC precursor, pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN). Once detected, the only way to accurately determine IPMN severity/ pathology [which spans from low-grade (LG) and moderate-grade (MG) to high-grade (HG) dysplasia & invasive carcinoma] is surgical resection, which is associated with an operative mortality of 2%–4% and morbidity of 40%–50%11. Consensus guidelines for IPMN management depend on standard radiologic and clinical features12. The guidelines recommend that those with 'high risk stigmata' undergo resection as most harbor HG or invasive disease. High risk stigmata include: main pancreatic duct (MD) involvement/ dilatation ≥10 mm, jaundice, or an enhanced solid component/nodule). IPMNs with ‘worrisome features’ (MD dilation 5–9 mm, size ≥3 cm, thickened cyst walls, non-enhanced mural nodules, or pancreatitis) are recommended for surveillance with an invasive endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspirate procedure despite poor sensitivity and complications10,13. However, consensus guidelines12 incorrectly predict pathology in 30%–70% of cases12,14-18, causing under- and over-treatment. Thus, rationale exists for identifying noninvasive markers to improve diagnostic accuracy for IPMNs, especially those without high risk stigmata19,20.

Increased glucose uptake and energy metabolism is prominent in PDACs21,22 and correlates with IPMN grade23. Therefore, metabolic dysregulation characterized by obesity may also associate with IPMN severity. Only one study of IPMNs24 has specifically examined if obesity is associated with malignancy. Very high BMI (≥35 kg/m2) was associated with a high prevalence of malignancy in side branch duct (BD) IPMNs. BD-IPMNs without high risk stigmata are challenging to manage15-18,25-27, and if obesity is a marker of malignant BD-IPMNs, this could aid in management. One major limitation of prior studies2-6,24 is that BMI was used to measure obesity. BMI is imprecise and cannot differentiate between subcutaneous fat accumulation (which represents the normal physiological buffer for excess energy intake) and abdominal/visceral adiposity28, a facilitator of carcinogenesis through metabolic disturbances, inflammation, and fat infiltration in the pancreas29-36. Abdominal/visceral fat area (VFA) is a risk factor for pancreatic fat infiltration in patients with PC37 and PanINs38, and is associated with poor PC outcomes31,37,39. Routine abdominal CT scans are the gold-standard for investigating quantitative radiologic features of abdominal adiposity (such as VFA)40, yet no published studies of these features exist for IPMN patients. We sought to determine if quantitative radiologic features of obesity extracted from abdominal CT scans can help to distinguish risk of malignant versus benign IPMNs.

Materials and methods

Study population and data

The study population included a fixed cohort of 37 patients with IPMNs whose pre-operative CT images had recently been evaluated as part of a different study20. The cases had initially been identified using a prospectively maintained clinical database of individuals who underwent a pancreatic resection for an IPMN between 2006 and 2011 at Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute (Moffitt) and provided written consent for medical images and clinical data to be donated for research through protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of South Florida, including Total Cancer Care41. For all cases, demographic and clinical data (presenting systems, age at diagnosis, past medical and surgical history, and information on known and suspected cancer risk factors such as smoking, family history, and body mass index calculated from pre-surgical height and weight) was obtained from the electronic medical record and patient questionnaire. Detailed imaging studies, surgical details, pathology results, lab values (serum CA 19-9), and treatment information was collected from the medical record and Moffitt’s Cancer Registry.

Histopathologic analysis

Board-certified pathologists with expertise in PDAC and IPMN pathology (KJ, DC, BAC) previously histologically confirmed the diagnosis and degree of dysplasia using World Health Organization guidelines42. The final diagnosis represented the most severe grade of dysplasia observed in the neoplastic epithelium. None of the cases received pre-operative chemotherapy or radiation. ‘Malignant’ cases were classified as having high-grade dysplasia or invasive carcinoma and ‘benign’ cases were defined by low- or moderate-grade dysplasia.

CT imaging, acquisition, and abdominal obesity assessment

Most of the CT scans from this series of patients were obtained on the Siemens Sensation (16, 40, or 64) using an abdominal or pancreatic CT angio (CTA) protocol according to standard operating procedures described previously20. Archived non-enhanced CT images performed within the three months prior to surgery, were acquired from Moffitt’s GE Centricity Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS). The imaging team, led by our board-certified abdominal radiologists (DJ and JC), were blinded to the final pathology. Contrast enhanced axial venous phase images were used and reviewed for high risk stigmata and worrisome features of the pancreatic lesions12. Non enhanced axial CT images were utilized and have previously shown to be adequate for visceral and subcutaneous fat measurements43,44. Measures of total abdominal fat (TAF) area, VFA, and subcutaneous fat area (SFA) were obtained using the volume segmentation and thresholding tools in AW server version 2.0 software (General Electric, Waukesha, WI, USA). The axial L2-L3 intervertebral disc level was used for analysis because adipose tissue at this level corresponds to whole body quantities45 and is well distinguished from skeletal muscle and other structures40,46,47. CT attenuation thresholds to define adipose tissue were set between –249 and –49 Hounsfield Units44. TAF area on an L2–L3 axial slice nearest the superior endplate of L3 was calculated by counting the volume of voxels that meet fat attenuation thresholds divided by slice thickness, which allowed standardization of measurements despite potentially different CT scan protocols. VFA was manually segmented along the fascial plane tracing the abdominal wall48. SFA was calculated by subtracting VFA from TAF. The VFA to SFA ratio (V/S) was calculated with V/S>0.4 cm2 defined as viscerally obese46,49,50. Manual tracing of the visceral fascial plane allowed the radiologist to exclude any fat density regions within bowel or fatty lesions within organs.

Statistical analysis

For select variables, descriptive statistics were calculated using frequencies and percents for categorical variables and means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables. The distributions of covariates were compared across groups using the Wilcoxon two sample two-sided exact test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Stratified analyses of BMI and radiologic obesity measures were conducted by gender. Spearman correlations were calculated to evaluate the relationship between BMI and quantitative radiologic obesity measures. Estimates of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated for key variables. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Study population characteristics

Radiologic measures of obesity were successfully calculated for 34 of the 37 cases; three cases did not have available scans in our PACS including the axial L2–L3 intervertebral disc level views for adiposity measurement. Clinical, epidemiologic, and imaging characteristics of the 34 cases (17 benign; 17 malignant) investigated in this analysis are in Table 1 and are in line with published data on other IPMN cohorts51. Seventy-six percent with malignant pathology had MD involvement on CT versus 24% with benign pathology (P=0.005). Mean lesion size was higher in the malignant compared to the benign group (3.4 versus 1.9 cm),P=0.003. Malignant IPMNs, particularly those deemed to be invasive, were predominately located in the pancreatic head. The majority of cases (82%) with malignant pathology had one or more high risk stigmata (MD involvement/dilatation>10 mm, obstructive jaundice with a cystic lesion in the pancreatic head, or an enhanced solid component within the cyst), versus 18% of those with benign pathology (P<0.001). Presence of one or more worrisome features (ie. MD dilation 5–9 mm, cyst size>3 cm, thickened enhanced cyst walls, non-enhanced mural nodules, or acute pancreatitis) was not associated with malignancy (P=0.708) in this cohort. BMI was higher in malignant (28.9 kg/m2, 95% CI: 26.3–31.4 kg/m2) versus benign cases (25.8 kg/m2, 95% CI: 23.3–28.3 kg/m2), withP=0.045. Mean BMI was similar in males and females, at 27.8 and 27.0 kg/m2, respectively.

1.

Characteristics of IPMN cases in the study cohort (n=34)

| Variable | Benign IPMNs (n=17)a | Malignant IPMNs (n=17)b | P |

| Data represent counts (percentages) unless otherwise indicated. Counts may not add up to the total due to missing values, and percentages may not equal 100 due to rounding.P value estimated using the Wilcoxon two sample two-sided exact test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables.a Benign IPMNs are represented by 2 low-grade and 15 moderate-grade IPMNs.b Malignant IPMNs are represented by 11 high-grade and 6 invasive IPMNs. | |||

| Age at diagnosis, mean (SD), years | 67.5 (10.9) | 71.8 (11.3) | 0.143 |

| Gender | 0.032 | ||

| Male | 3 (18) | 10 (59) | |

| Female | 14 (82) | 7 (41) | |

| Race | 0.485 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 17 (100) | 15 (88) | |

| Black | 0 (0) | 2 (12) | |

| Jaundice as presenting symptom | 0.103 | ||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 4 (24) | |

| No | 17 (100) | 13 (76) | |

| Pre-operative serum CA 19-9 levels, mean (SD) (ng/mL) | 18.2 (19.1) | 185.5 (350.1) | 0.216 |

| Predominant tumor location | 0.084 | ||

| Pancreatic head | 6 (35) | 12 (71) | |

| Pancreatic body or tail | 11 (65) | 5 (29) | |

| Type of ductal communication | 0.005 | ||

| Main duct or mixed | 4 (24) | 13 (76) | |

| Branch duct | 13 (76) | 4 (24) | |

| Size of largest cyst, mean (SD) (cm) | 1.9 (1.1) | 3.4 (1.3) | 0.008 |

| Solid component or mural nodule | 0.141 | ||

| Yes | 3 (18) | 8 (47) | |

| No | 14 (82) | 9 (53) | |

| High risk stigmata | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 3 (18) | 14 (82) | |

| No | 14 (82) | 3 (18) | |

| Worrisome features | 0.708 | ||

| Yes | 11 (65) | 13 (76) | |

| No | 6 (35) | 4 (24) | |

| BMI, mean (95% CI) (kg/m2) | 25.8 (4.9) | 28.9 (4.9) | 0.045 |

Analysis of quantitative radiologic measures of obesity

Mean VFA was higher in patients with malignant (199 cm2) versus benign (120 cm2) IPMNs, but did not reach statistical significance with the Wilcoxon two-sample exact test (P=0.092) ( Table 2 ). Mean V/S was substantially higher in malignant versus benign IPMNs, with values of 1.25 cm2 and 0.69 cm2, respectively (P=0.013). We found no statistically significant differences between TAF and SFA in the malignant and benign groups.

2.

Quantitative radiologic measures of obesity, by IPMN pathology

| Parameter | Benign IPMNs (n=17) | Malignant IPMNs (n=17) | P |

| Data represent mean values and standard deviation.P value was estimated using Wilcoxon two sample exact tests. | |||

| TAF area (cm2) | 321.8 (169.5) | 391.0 (201.3) | 0.259 |

| VFA (cm2) | 120.4 (68.4) | 199.3 (125.4) | 0.092 |

| SFA (cm2) | 201.3 (132.1) | 191.6 (191.6) | 0.734 |

| V/S (cm2) | 0.69 (0.5) | 1.25 (1.1) | 0.013 |

Males had a higher mean VFA value (202.4 cm2) than females (133.6 cm2) and a higher mean V/S value (1.25 cm2) than females (0.80 cm2). Stratified analyses revealed that among both males and females, mean BMI, TAF, and VFA values were higher for patients with malignant compared to benign IPMNs, though results were not statistically significant (P>0.05) for either gender ( Table 3 ). Among females, V/S was significantly higher for those having malignant IPMNs (P=0.038). While no correlation existed between BMI and V/S (r=0.16,P=0.35), significant positive correlations were found between BMI and VFA (r=0.68,P<0.0001) and between BMI and SFA (r=0.71,P<0.0001).

3.

Gender-specific differences in BMI and quantitative radiologic measures of obesity, by IPMN pathology

| Parameter | Males (3 benign; 10 malignant) | P | Females (14 benign; 7 malignant) | P |

| Data represent mean values and standard deviation.P values estimated using the Wilcoxon two sample two-sided exact test. | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.0 (2.2); 29.0 (5.2) | 0.112 | 26.2 (5.3); 28.8 (4.8) | 0.224 |

| TAF area (cm2) | 209.9 (78.9); 408.9 (227.4) | 0.371 | 328.4 (184.7); 365.3 (171) | 0.689 |

| VFA (cm2) | 174.7 (80.7); 210.7 (131.5) | 1.000 | 108.8 (62.7); 183.2 (124.3) | 0.197 |

| SFA (cm2) | 116.3 (9.8); 198.3 (113.4) | 0.077 | 219.6 (139.5); 182.2 (95.7) | 0.743 |

| V/S (cm2) | 1.5 (0.8); 1.2 (0.5) | 0.287 | 0.5 (0.2); 1.4 (1.7) | 0.038 |

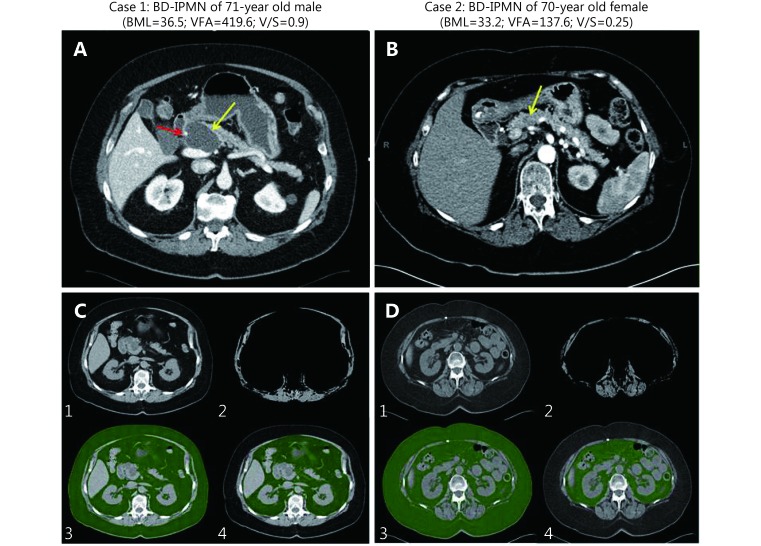

Of clinical importance, Figure 1 displays CT scans from two IPMN patients who did not present with high risk stigmata on imaging. Both have similar BMIs but vastly different VFA and V/S values, with case 1 having higher VFA and V/S and a worrisome feature (cyst size>3 cm) and high-grade pathology and case 2 having lower VFA and V/S and low-grade pathology at resection. These data suggest that visceral fat may be added as another risk factor to potentially aid in directing management towards a necessary surgery to remove what turned out to be a high-grade lesion (case 1) and avoided an unnecessary surgery for a low-grade lesion (case 2). The accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of V/S in predicting malignant IPMN pathology were 74%, 71%, 76%, 75% and 72%, respectively.

1.

Axial post contrast CTs (A and B) and quantitative segmentation (C and D) for two representative side BD IPMN cases with main pancreatic ducts normal in caliber. Case 1 has a well-demarcated homogenous hypodense 4.8 cm cystic lesion in the pancreatic neck (yellow arrow). The cystic lesion abuts the gastroduodenal artery (red arrow) without definite encasement. Case 2 has a poorly defined 1.3 cm hypoenhancing pancreatic neck lesion (yellow arrow). C and D: (1) Axial CT image through L2–L3 intervertebral disc level. (2) Axial CT subtracted image at superior endplate of L3. Abdominal wall and paraspinal muscle area were segmented and thresholds set to voxels with Hounsfield units (HU) –29 to 150. Visceral fat, intra-abdominal organs, and vasculature were subtracted. Although skeletal muscle indices can be obtained in a complementary manner to visceral fat measurements, these were not directly analyzed in this study. (3) Total abdominal fat with HU thresholds applied to include fat density voxels with HU –249 to –49 (green). (4) Manual segmentation of visceral fat regions (green).

Discussion

This pilot project represents the first to study objectively quantitative radiologic measures of obesity as diagnostic markers of IPMN pathology. In addition to observing higher pre-operative BMI values in patients confirmed to have malignant IPMNs, VFA and V/S values were also observed in the malignant IPMN group compared to those with benign IPMNs. We also observed that males with IPMNs had higher VFA and V/S values than female cases, in line with the observation that visceral fat is more common in males28, and showed that women with benign IPMNs had a significantly lower V/S ratio (0.5 cm2) than those with malignant IPMNs (1.4 cm2), Women with benign IPMNs in our cohort appeared to have a higher SFA than other cohort members, consistent with data suggesting that subcutaneous fat may not be a marker of malignancy28. Previous authors have suggested that in an asymptomatic adult cohort, men have significantly higher V/S ratios52. However, no standardized gender-based V/S values are currently available which suggests further research is needed to define visceral obesity in each gender. Our small cohort, however, had relatively more females in the benign pathology group and more males in the malignant pathology group, so firm conclusions cannot be drawn based on these preliminary findings. Despite this, findings suggest that being overweight or obese, particularly in the intra-abdominal area, may be a prognostic marker for malignant potential of IPMNs. Given that abdominal/visceral adiposity has been shown to influence carcinogenesis and that BMI is an imprecise proxy for abdominal adiposity29-36, biologically-driven radiologic measures of visceral fat may have greater clinical utility than BMI in predicting IPMN pathology. Further research with a larger sample size is clearly needed to distinguish the relationship between radiologic measures of visceral fat, gender, and malignancy.

Few studies have reported on quantitative radiologic measures of obesity in patients with PDAC. In a study of 9 PDAC cases and matched controls53, no significant differences in SFA, VFA, TFA, or V/S were observed between the patients and controls. On the other hand, pre-operative visceral fat was shown to be a prognostic indicator in patients with PDAC, with increased visceral fat being associated with worse survival in patients with lymph node metastases37. Elevated visceral fat defined by the V/S has also been shown to predict recurrence among locally advanced rectal cancer patients50. Collectively, these37,50 and other studies31,35 provide plausibility for our observation that VFA and V/S may be associated with more advanced IPMN pathology.

Although limitations of this pilot study include its small size and retrospective design, characteristics of this cohort are representative of other IPMN cohorts, suggesting potential generalizability. External validation in a large, independent data set is warranted. Furthermore, with a larger sample size, multivariable modeling and receiver characteristic curve analyses will be helpful to determine the utility of gender-specific radiologic measures of abdominal obesity in discriminating malignant from benign IPMNs, independent of and in combination with novel molecular and radiologic markers19,20, standard clinical and radiologic features encompassed by consensus guidelines12, and BMI.

In summary, use of quantitative radiologic measures of abdominal obesity could provide a noninvasive, rapid, low cost, and repeatable way of investigating features that may potentially aid in personalizing care for patients with pancreatic cancer precursors. Given that a reduction in abdominal adiposity by lifestyle, diet, and/or pharmacologic intervention would be impactful and could translate into a decreased burden of PC, obesity, and other diseases, further studies in this area are warranted.

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of interest statement

No potential conflicts of interest are disclosed.

References

- 1.Yeo TP. Demographics, epidemiology, and inheritance of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:8–18. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marmot M, Atinmo T, Byers T, Chen J, Hirohata T, Jackson A, et al. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. American Institute for Cancer Research, 2007. (请核对作者及出版地)

- 3.Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB. Risk factors for pancreatic cancer: a summary review of meta-analytical studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:186–98. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuan C, Bao Y, Wu C, Kraft P, Ogino S, Ng K, et al. Prediagnostic body mass index and pancreatic cancer survival. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4229–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.7532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coughlin SS, Calle EE, Patel AV, Thun MJ. Predictors of pancreatic cancer mortality among a large cohort of United States adults. Cancer Causes Control. 2000;11:915–23. doi: 10.1023/a:1026580131793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bracci PM. Obesity and pancreatic cancer: overview of epidemiologic evidence and biologic mechanisms. Mol Carcinog. 2012;51:53–63. doi: 10.1002/mc.20778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315:2284–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koh JC, Loo WM, Goh KL, Sugano K, Chan WK, Chiu WYP, et al. Asian consensus on the relationship between obesity and gastrointestinal and liver diseases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:1405–13. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Megibow AJ, Baker ME, Gore RM, Taylor A. The incidental pancreatic cyst. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011;49:349–59. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farrell JJ. Prevalence, diagnosis and management of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: current status and future directions. Gut Liver. 2015;9:571–89. doi: 10.5009/gnl15063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hines OJ, Reber HA. Pancreatic surgery. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:603–11. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32830b112e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka M, Fernández-del Castillo C, Adsay V, Chari S, Falconi M, Jang JY, et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12:183–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panarelli NC, Sela R, Schreiner AM, Crapanzano JP, Klimstra DS, Schnoll-Sussman F, et al. Commercial molecular panels are of limited utility in the classification of pancreatic cystic lesions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1434–43. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31825d534a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim KW, Park SH, Pyo J, Yoon SH, Byun JH, Lee MG, et al. Imaging features to distinguish malignant and benign branch-duct type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2014;259:72–81. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31829385f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roch AM, Ceppa EP, DeWitt JM, Al-Haddad MA, House MG, Nakeeb A, et al. International Consensus Guidelines parameters for the prediction of malignancy in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm are not properly weighted and are not cumulative. HPB. 2014;16:929–35. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahora K, Mino-Kenudson M, Brugge W, Thayer SP, Ferrone CR, Sahani D, et al. Branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: does cyst size change the tip of the scale? A critical analysis of the revised international consensus guidelines in a large single-institutional series. Ann Surg. 2013;258:466–75. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a18f48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fritz S, Klauss M, Bergmann F, Strobel O, Schneider L, Werner J, et al. Pancreatic main-duct involvement in branch-duct IPMNs: an underestimated risk. Ann Surg. 2014;260:848–55. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goh BKP, Tan DMY, Ho MMF, Lim TKH, Chung AYF, Ooi LLPJ. Utility of the sendai consensus guidelines for branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:1350–7. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2510-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Permuth-Wey J, Chen DT, Fulp WJ, Yoder SJ, Zhang YH, Georgeades C, et al. Plasma microRNAs as novel biomarkers for patients with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2015;8:826–34. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-15-0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Permuth JB, Choi J, Balarunathan Y, Kim J, Chen DT, Chen L, et al. Combining radiomic features with a miRNA classifier may improve prediction of malignant pathology for pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Oncotarget. 2016;7:85785–97. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SM, Kim TS, Lee JW, Kim SK, Park SJ, Han SS. Improved prognostic value of standardized uptake value corrected for blood glucose level in pancreatic cancer using F-18 FDG PET. Clin Nucl Med. 2011;36:331–6. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31820a9eea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Regel I, Kong B, Raulefs S, Erkan M, Michalski CW, Hartel M, et al. Energy metabolism and proliferation in pancreatic carcinogenesis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2012;397:507–12. doi: 10.1007/s00423-012-0933-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basturk O, Singh R, Kaygusuz E, Balci S, Dursun N, Culhaci N, et al. GLUT-1 expression in pancreatic neoplasia: implications in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and prognosis. Pancreas. 2011;40:187–92. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318201c935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sturm EC, Roch AM, Shaffer KM, Schmidt CM II, Lee SJ, Zyromski NJ, et al. Obesity increases malignant risk in patients with branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Surgery. 2013;154:803–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Correa-Gallego C, Ferrone CR, Thayer SP, Wargo JA, Warshaw AL, Fernández-Del Castillo C. Incidental pancreatic cysts: do we really know what we are watching? Pancreatology. 2010;10:144–50. doi: 10.1159/000243733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salvia R, Malleo G, Marchegiani G, Pennacchio S, Paiella S, Paini M, et al. Pancreatic resections for cystic neoplasms: from the surgeon's presumption to the pathologist's reality. Surgery. 2012;152:S135–42. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.LaFemina J, Katabi N, Klimstra D, Correa-Gallego C, Gaujoux S, Kingham TP, et al. Malignant progression in IPMN: a cohort analysis of patients initially selected for resection or observation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:440–7. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2702-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibrahim MM. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: structural and functional differences. Obes Rev. 2010;11:11–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Batista ML Jr, Olivan M, Alcantara PSM, Sandoval R, Peres SB, Neves RX, et al. Adipose tissue-derived factors as potential biomarkers in cachectic cancer patients. Cytokine. 2013;61:532–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malietzis G, Aziz O, Bagnall NM, Johns N, Fearon KC, Jenkins JT. The role of body composition evaluation by computerized tomography in determining colorectal cancer treatment outcomes: a systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:186–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vongsuvanh R, George J, Qiao L, van der Poorten D. Visceral adiposity in gastrointestinal and hepatic carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2013;330:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathur A, Marine M, Lu DB, Swartz-Basile DA, Saxena R, Zyromski NJ, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty pancreas disease. HPB. 2007;9:312–8. doi: 10.1080/13651820701504157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smits MM, van Geenen EJM. The clinical significance of pancreatic steatosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:169–77. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Flanagan CH, Bowers LW, Hursting SD. A weighty problem: metabolic perturbations and the obesity-cancer link. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2015;23:47–57. doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2015-0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feakins RM. Obesity and metabolic syndrome: pathological effects on the gastrointestinal tract. Histopathology. 2016;68:630–40. doi: 10.1111/his.12907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polvani S, Tarocchi M, Tempesti S, Bencini L, Galli A. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptors at the crossroad of obesity, diabetes, and pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:2441–59. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i8.2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathur A, Hernandez J, Shaheen F, Shroff M, Dahal S, Morton C, et al. Preoperative computed tomography measurements of pancreatic steatosis and visceral fat: prognostic markers for dissemination and lethality of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. HPB. 2011;13:404–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rebours V, Gaujoux S, d'Assignies G, Sauvanet A, Ruszniewski P, Lévy P, et al. Obesity and Fatty Pancreatic Infiltration Are Risk Factors for Pancreatic Precancerous Lesions (PanIN) Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:3522–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eastwood SV, Tillin T, Wright A, Heasman J, Willis J, Godsland IF, et al. Estimation of CT-derived abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue depots from anthropometry in Europeans, South Asians and African Caribbeans. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andreoli A, Garaci F, Cafarelli FP, Guglielmi G. Body composition in clinical practice. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85:1461–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fenstermacher DA, Wenham RM, Rollison DE, Dalton WS. Implementing personalized medicine in a cancer center. Cancer J. 2011;17:528–36. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e318238216e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adsay NV FT, Hruban RH, Klimstra DS, Kloppel G, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th edition. Lyon: WHO Press; 2010. p.304–313. (请核对子文献信息)

- 43.Pickhardt PJ, Jee Y, O'Connor SD, del Rio AM. Visceral adiposity and hepatic steatosis at abdominal CT: association with the metabolic syndrome. Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:1100–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryckman EM, Summers RM, Liu JM, del Rio AM, Pickhardt PJ. Visceral fat quantification in asymptomatic adults using abdominal CT: is it predictive of future cardiac events? Abdom Imag. 2015;40:222–6. doi: 10.1007/s00261-014-0192-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin L. Diagnostic criteria for cancer cachexia: data versus dogma. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2016;19:188–98. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yip C, Dinkel C, Mahajan A, Siddique M, Cook GJ, Goh V. Imaging body composition in cancer patients: visceral obesity, sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity may impact on clinical outcome. Insights Imaging. 2015;6:489–97. doi: 10.1007/s13244-015-0414-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen W, Punyanitya M, Wang ZM, Gallagher D, St-Onge MP, Albu J, et al. Total body skeletal muscle and adipose tissue volumes: estimation from a single abdominal cross-sectional image. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2004;97:2333–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00744.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nattenmueller J, Hoegenauer H, Boehm J, Scherer D, Paskow M, Gigic B, et al. CT-based compartmental quantification of adipose tissue versus body metrics in colorectal cancer patients. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:4131–40. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4231-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitaker KM, Choh AC, Lee M, Towne B, Czerwinski SA, Demerath EW. Sex differences in the rate of abdominal adipose accrual during adulthood: The Fels Longitudinal Study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2016;40:1278–85. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clark W, Siegel EM, Chen YA, Zhao XH, Parsons CM, Hernandez JM, et al. Quantitative measures of visceral adiposity and body mass index in predicting rectal cancer outcomes after neoadjuvant chemoradiation. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:1070–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matthaei H, Schulick RD, Hruban RH, Maitra A. Cystic precursors to invasive pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:141–50. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maurovich-Horvat P, Massaro J, Fox CS, Moselewski F, O'Donnell CJ, Hoffmann U. Comparison of anthropometric, area- and volume-based assessment of abdominal subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue volumes using multi-detector computed tomography. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:500–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kwee TC, Kwee RM. Abdominal adiposity and risk of pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2007;35:285–6. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318068fca6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]