Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the incidence of fragility fractures associated with high-dose glucocorticoid therapy in patients with systemic rheumatic disease.

Methods: A retrospective study of patients who were treated with high-dose prednisolone (> 0.8 mg/kg) for systemic rheumatic disease at Kobe University Hospital from April 1988 to March 2012. The primary outcome was a major osteoporotic fracture (defined as a clinical vertebral, hip, forearm, or proximal humerus fracture) after high-dose glucocorticoid therapy. For postmenopausal women and men over 40 of age, the patient's fracture risk at the beginning of high-dose glucocorticoid therapy was assessed by the World Health Organization's Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX®).

Results

Of 229 patients (median age: 49 years), 57 suffered a fragility fracture during the observation period (median observation period: 1558 days). Of 84 premenopausal patients, 5 suffered a fracture. In contrast, of 86 postmenopausal female, 36 suffered a fracture. Fragility fractures were far more frequent than predicted by the FRAX® score. Patients with FRAX® scores over 8.3% had a particularly high risk of fracture.

Conclusions

Fragility fractures associated with high-dose glucocorticoid therapy are common among postmenopausal women. Extreme care should be taken especially for postmenopausal women when high-dose glucocorticoid therapy is required.

Keywords: Glucocorticoid induced osteoporosis, Fragility fracture, FRAX, High-dose glucocorticoid therapy, And systemic rheumatic disease

Highlights

-

•

We evaluated the incidence of the fragility fractures associated with high-dose glucocorticoid therapy.

-

•

Of 86 postmenopausal female, 36 suffered a fracture during the observation period.

-

•

Patients with FRAX scores over 8.3% had a particularly high risk of fracture.

1. Introduction

Glucocorticoid (GC) therapy is the primary treatment option for patients with systemic rheumatic disease. Osteoporosis, which is a common complication of high-dose GC therapy, is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Although awareness of GC-induced osteoporosis (GIO) has increased in recent years, GIO remains underdiagnosed and undertreated. GIO's distinctive characteristics include rapid bone loss and an increase in fracture risk shortly after beginning GC therapy; therefore, the primary prevention of fractures in high-risk individuals is critical (Compston, 2010).

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) published Recommendations for the Prevention and Treatment of Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis in 1996 (American College of Rheumatology Task Force, 1996), and various guidelines have since been published for other countries (American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee, 2001) (Bone and Tooth Society of Great Britain, National Osteoporosis Society, Royal College of Physicians, Glucocorticoid-induced-osteoporosis guidelines for prevention and treatment, 2002) (Devogelaer et al., 2006) (Watts et al., 2008) (Grossman et al., 2010) (Suzuki et al., 2014). Some of these guidelines use the World Health Organization's Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX®), which uses a computer-based algorithm (http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX) to calculate the 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture (defined as a clinical vertebral, hip, forearm, or proximal humerus fracture) and the 10-year probability of a hip fracture (Watts et al., 2008) (Grossman et al., 2010). FRAX® integrates seven clinical risk factors—a prior fragility fracture, a parental history of hip fracture, smoking, use of systemic corticosteroids, rheumatoid arthritis, secondary osteoporosis, and excessive alcohol intake—which, in addition to age and sex, contribute to fracture risk independently of bone mineral density (BMD) (Kanis et al., 2008).

Although FRAX® is a valuable tool, it can underestimate risks because it does not include dose-response effects from contributing factors. For instance, there is strong evidence that the risks associated with excessive alcohol consumption (Berg et al., 2008), smoking (Hollenbach et al., 1993), and GC use (van Staa et al., 2000) are dose-responsive, and that the risk of fracture increases progressively with the number of prior fractures (Lindsay et al., 2001). However, FRAX® scores do not reflect these graded risks. Kanis et al. proposed adjusting FRAX® scores according to GC dosage, using these simple rules: for low-dose exposure, defined as < 2.5 mg/day prednisolone or the equivalent, the probability of a major fracture is about 20% less than predicted by the FRAX® score (although this result also depends on the patient's age). For a dosage of 2.5–7.5 mg/day prednisolone, the unadjusted FRAX® score can be used. For a dosage > 7.5 mg/day prednisolone, the probability is revised upward by about 15% (Kanis et al., 2011). However, these guidelines do not adequately assess the risks associated with high-dose GC therapy (prednisolone 0.8 mg/kg/day or more, equal to 40 mg prednisolone/day for a 50-kg patient), which is often used for patients who are severely affected by a rheumatic disease. The adjusted relative fracture rate increases drastically for daily GC doses above 20 mg prednisolone (van Staa et al., 2000). Despite this dramatic increase in the risk of fractures, the incidence rate of fragility fractures after high-dose GC therapy has not been reported.

Bisphosphonates, a family of anti-osteoporosis drugs that strongly inhibit osteoclasts, are reported to treat GIO effectively (Saag et al., 1998) (Cohen et al., 1999) (Reid et al., 2000) (Wallach et al., 2000) (Adachi et al., 2001) (de Nijs et al., 2006) (Reid et al., 2009) (Stoch et al., 2009) (Fahrleitner-Pammer et al., 2009) and are listed as a first-line pharmacologic intervention in several GIO-treatment guidelines (Bone and Tooth Society of Great Britain, National Osteoporosis Society, Royal College of Physicians, Glucocorticoid-induced-osteoporosis guidelines for prevention and treatment, 2002) (Devogelaer et al., 2006) (Watts et al., 2008) (Grossman et al., 2010) (Suzuki et al., 2014). Thus, many patients undergoing high-dose GC therapy also take bisphosphonates. However, bisphosphonate therapy for GIO has been studied only in patients receiving 20 mg/day prednisolone or less, and its efficacy for preventing fragility fractures associated with high-dose GC therapy has not been studied. Although newer, more effective GIO-prevention drugs have become available recently or are in development, it is not clear which patients on high-dose GC therapy should be given the newer drugs.

This retrospective study was conducted to research the incidence rate of fragility fractures in patients treated with high-dose GC therapy in a real-world clinical setting, and to investigate the discrepancy between the FRAX 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture and the actual fracture rate.

2. Methods

This study was reviewed and approved by the ethics board of Kobe University Hospital prior to enrolling the subjects.

We retrospectively reviewed medical records for all patients treated for systemic rheumatic disease at Kobe University Hospital from April 1998 to March 2012. In total, 2094 medical records were reviewed. The patients treated with prednisolone at a dose > 0.8 mg/kg/day were eligible for the study if they were followed continuously for at least 1 year after beginning treatment, and were not treated with teriparatide or denosumab. Based on these inclusion and exclusion criteria, 1865 records were discarded. We included 229 patients in the analysis.

The primary outcome for this study was a major osteoporotic fracture (defined as a clinical symptomatic vertebral, hip, forearm, or proximal humerus fracture) after high-dose GC therapy. We identified major osteoporotic fracture by retrospective medical record review. The diagnosis of osteoporotic fracture had been made mainly by rheumatologists or local orthopedist.

For postmenopausal women and men over 40 years of age, we calculated the 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture by using Japanese version of FRAX®, with or without femoral BMD, at the start of high-dose GC therapy. For patients who sustained a fragility fracture during the observation period for any given course of GC therapy, we used the data from the most recent admission and treatment period prior to the fracture.

We collected clinical information of each patient. For postmenopausal women and men over 40 years of age, we calculated the FRAX® 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture, with or without femoral BMD, at the start of high-dose GC therapy. Patients were considered to have received bisphosphonate and/or active vitamin D treatment if they are prescribed those medicines for at least 80% of the observation period. Patients who are prescribed bisphosphonate and/or active vitamin D treatment for < 80% of the observation period were used as comparison subjects; most of these patients are prescribed bisphosphonates or Vitamin D for < 20% of the observation period.

To assess calibration (i.e., the degree of similarity between predicted and observed risks), we stratified the postmenopausal women and men over 40 years of age into 4 groups according to their FRAX® score and compared the 10-year probability of a major fragility fracture with the observed incidence of fractures in our real-world clinical setting.

The fracture incidence was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. We used the Cox proportional hazard model for multivariable analysis of the incidence of fragility fractures after high-dose GC therapy; the variables analysed included the FRAX® 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture at baseline, one or more previous cycles of high-dose GC therapy, and the use of bisphosphonate, active vitamin D, or methylprednisolone pulse therapies. We used estimated receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves to estimate the optimal cut-off value for the FRAX® 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture, and the sensitivity and specificity at the estimated optimal cut-off value. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and P < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical tests were two-tailed.

3. Results

This study included 229 patients. There were 76 patients with systemic lupus erythematous (SLE), 58 with vasculitis syndrome, 51 with polymyositis/dermatomyositis (PM/DM), 12 with adult-onset Still's disease (AOSD), 7 with mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) and 25 with other diseases. There were 84 premenopausal women, 86 postmenopausal women and 59 men. The median observation period was 1558 days. Fragility fractures occurred in 57 patients during the observation period. Clinical spinal fractures occurred in 52 patients, hip fractures in 3 patients, wrist in 1 patient and proximal humerus fracture in 1 patient. (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline subject characteristics.

| Disease | Number | Female | Median Age [25%–75%] | Median Observation Period [25%–75%] | Median FRAXa [25%–75%] | Bisphosphonates prescription (%) | Prior high-dose GC (%) | Fragility Fracture (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLE | 76 | 66 (86.8) | 30.5 [24–37] | 2226 [1124–3085] | 5.3 [3.7–10.9] | 28 (36.8) | 30 (39.5) | 6 (7.8) |

| Vasculitisb | 58 | 45 (75.9) | 66 [47.8–70.8] | 1166 [618.3–2087] | 14 [6.8–24] | 38(65.5) | 9 (15.5) | 18 (31) |

| PM/DM | 51 | 34 (66.7) | 58 [47–69] | 1655 [676–2587] | 9 [5.9–14] | 34 (66.7) | 5 (9.8) | 18 (35.3) |

| AOSD | 12 | 7 (58.3) | 37.5 [26–56] | 1613 [1215–2335] | 7.2 [3.2–9.8] | 7 (58.3) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (16.7) |

| MCTD | 7 | 6 (75) | 42 [35–54] | 1975 [1768–2540] | 5.7 [2.8–10] | 6 (85.7) | 2 (29) | 1 (14.2) |

| Othersc | 25 | 12 (48) | 63 [57.5–70] | 833 [283–2650] | 6.7 [4.9–13] | 9 (36) | 4 (16) | 12 (48) |

| Total | 229 | 170 (74.2) | 49 [31–66] | 1558 [803–2596] | 9 [5.2–15] | 122 (53.2) | 51 (22.2) | 57c (24.9) |

AOSD = adult-onset Still's disease.

FRAX is calculated for postmenopausal women and men over 40 of age.

Vasculitis syndromes: Takayasu arteritis (11); giant-cell arteritis (11); microscopic polyangiitis (10); granulomatosis with polyangiitis (7); eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (6); Behcet's disease (5); rheumatoid vasculitis (4); unclassified vasculitis (4). bOther diseases: IgG4-related disease (4); Castleman's disease (3); overlap syndrome (3); sarcoidosis (2); diffuse fasciitis (3); systemic sclerosis (2); relapsing polychondritis (2); idiopathic thrombocytopenia (1); autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (1); autoimmune hepatitis (1); eosinophilic pneumonia (1); and pachymeningitis (1).

52 clinical spinal, 3 hip, 1 humerus and 1 wrist fracture.

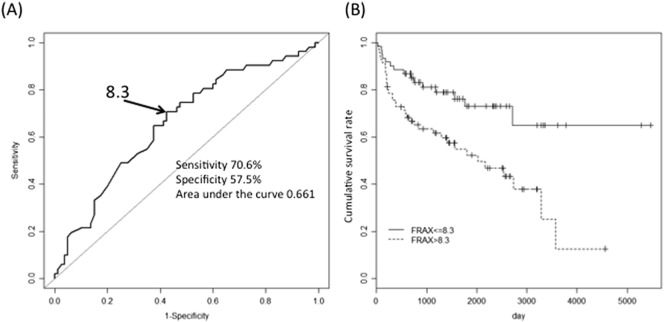

When comparing patients with or without fractures during the observation period, we found no significant difference in the percentage of patients who received methylprednisolone pulse therapy or were prescribed bisphosphonate or active Vitamin D for at least 80% of the observation period (Table 2). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed postmenopausal women are at greatly increased risk of fragility fractures after high-dose GC therapy (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with and without fragility fractures.

| Women (n = 170) |

Men (n = 59) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| premenoposal (n = 84) |

postmenoposal (n = 86) |

|||||

| Fracture (n = 5) | Fracture-free (n = 79) | Fracture (n = 36) | Fracture-free (n = 50) | Fracture (n = 16) | Fracture-free (n = 43) | |

| Bisphosphonate prescription | 1 (25%) | 27 (34.2%) | 24 (66.7%) | 36 (72%) | 8 (50%) | 26 (60.5%) |

| Active Vitamin D prescription | 3 (60%) | 53 (67.1%) | 17 (47.2%) | 32 (64%) | 9 (56.3%) | 15 (34.9%) |

| Methylprednisolone pulse therapy | 5 (100%) | 43 (54.4%) | 17 (47.2%) | 16 (32%) | 3 (18.8%) | 21 (48.8%) |

| Prior high-dose GC treatment | 4 (80%) | 26 (32.9%) | 5 (13.9%) | 4 (8%) | 6 (37.5%) | 5 (11.6%) |

| FRAX (major fractures) | − | − | 14.5 | 10 [4.9–16.8] | 8.5 [5.0–12.0]1 | 6.1 [4.2–8.5]1 |

FRAX 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture is calculated for male over 40 years of age.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis after high-dose glucocorticoid therapy.

To investigate the correlation between FRAX® and observed fracture rate, we preformed subgroup analysis for the postmenopausal women and men over 40 years of age. The incidence of fragility fractures during the observation period after high-dose GC therapy was considerably higher than the incidence predicted by the FRAX® 10-year probability scores assessed prior to the GC therapy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Discrepancy between the FRAX 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture and observed fractures.

| FRAX | Mean FRAX (%) | Number of patients | Fractures | Fracture rate (%) | Median observation period (year) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 131) | 0%- < 5.3% | 3.6 | 33 | 6 | 18.2 | 1.4 |

| 5.3%- < 9% | 7 | 32 | 12 | 37.5 | 2 | |

| 9%- < 15% | 11.7 | 30 | 13 | 43.3 | 2.1 | |

| ≥ 15% | 26.7 | 36 | 20 | 55.6 | 0.8 | |

| Postmenopausal women (n = 86) | 0%- < 6.3% | 4.1 | 22 | 5 | 22.7 | 3.2 |

| 6.3%- < 12% | 8.7 | 19 | 8 | 42.1 | 3.9 | |

| 12%- < 22% | 15.2 | 23 | 12 | 52.2 | 0.7 | |

| ≥ 22% | 32.9 | 22 | 11 | 50 | 0.7 | |

| Men over 40 years of age (n = 45) | 0%- < 4.5% | 3.2 | 12 | 2 | 16.7 | 1.4 |

| 4.5%- < 6.6% | 5.5 | 10 | 3 | 30 | 0.3 | |

| 6.6%- < 9.2% | 7.7 | 11 | 4 | 36.4 | 1.5 | |

| ≥ 9.2% | 12.3 | 12 | 6 | 50 | 1.6 |

In multivariable analysis, bisphosphonate treatment, active vitamin D treatment, and methylprednisolone pulse therapy were found not to be related to fragility fractures. As expected, the FRAX® score was associated with the incidence of fragility fractures. In addition, a history of previous cycles of high-dose GC therapy was associated with a significant increase in the risk of fragility fractures (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate survival analysis.

| Total (n = 131) |

Postmenopausal Women (n = 86) |

Men over 40 years of age (n = 45) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted hazard ratio | 95% CI | Adjusted hazard ratio | 95% CI | Adjusted hazard ratio | 95% CI | |

| FRAX (continuous, log-transformed) | 2.26 | 1.52–3.38 | 2.41 | 1.45–3.99 | 3.21 | 1.03–9.98 |

| Bisphosphonate comparison subjects | 1 | (reference) | 1 | (reference) | 1 | (reference) |

| Bisphosphonate prescription group | 0.84 | 0.45–1.54 | 0.67 | 0.31–1.44 | 1.21 | 0.41–3.54 |

| Active Vitamin D comparison subjects | 1 | (reference) | 1 | (reference) | 1 | (reference) |

| Active Vitamin D prescription group | 0.82 | 0.47–1.43 | 0.72 | 0.36–1.44 | 1.27 | 0.40–3.87 |

| No methylprednisolone pulse treatment | 1 | (reference) | 1 | (reference) | 1 | (reference) |

| Methylprednisolone pulse treatment group | 1.14 | 0.61–2.13 | 1.68 | 0.79–3.61 | 0.4604 | 0.13–1.69 |

| No prior high-dose GC treatment | 1 | (reference) | 1 | (reference) | 1 | (reference) |

| Prior high-dose GC treatment | 2.49 | 1.18–5.28 | 1.24 | 0.43–3.60 | 3.46 | 1.12–10.73 |

Adjusted by bisphosphonate, vitamin D, or mPSL pulse therapy, a history of high-dose GC, and FRAX score.

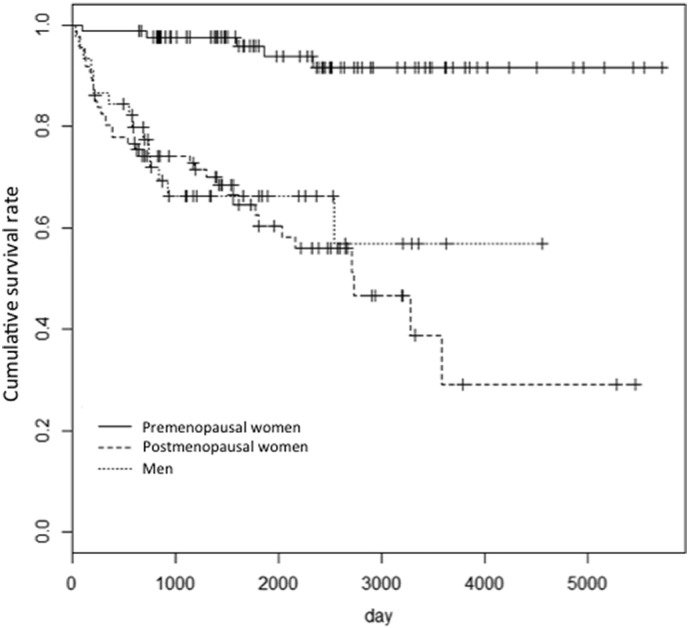

An ROC-curve analysis found that the optimal FRAX® 10-year probability cut-off for suffering major osteoporotic fractures after high-dose GC therapy was 8.3% (sensitivity 70.6%, specificity 57.5%, AUC 0.661). Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed a significant difference in fracture frequency between patients with FRAX® scores > 8.3% and those with a score of 8.3% or less (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

ROC curve analysis.

The optimal cut-off of the FRAX® 10-year probability score associated with fragility fracture was 8.3%. Thus, the risk of fragility fractures was significantly higher for patients with FRAX® scores of 8.3 or higher.

4. Discussion

The pathogenesis of GIO is thought to result from the direct effect of excess GC on bone cells (osteoclasts, osteocytes, and osteoblasts) and from indirect effects mediated by a negative calcium balance, the reduced production of gonadal hormones, and detrimental effects on the muscle (Canalis et al., 2007) (Hofbauer & Rauner, 2009). GC's direct effect is characterized by an early, transient phase of increased bone resorption, along with reduced bone formation throughout the duration of GC therapy. This early increase in bone resorption is thought to be a major contributor to the bone loss and the increase in fracture risk that develops within the first few months of GC therapy (Compston, 2010).

In the ACR guidelines for GIO prevention, the FRAX 10-year risk of a major osteoporotic fracture is defined as low if < 10%, medium if 10–20%, and high if over 20%. However, the use of FRAX® to estimate GIO-associated fracture risks has been criticized, since FRAX® does not take GC dose-response effects into account and can thus underestimate fracture risk (Suzuki et al., 2014) (Weinstein, 2011). FRAX® is deemed to be appropriated for patients on a prednisolone treatment regimen of 2.5–7.5 mg daily (Kanis et al., 2011). To our knowledge, FRAX® scores have not been validated for patients on high-dose GC treatment regimens. There are several likely reasons for this lapse. Relatively few patients require high-dose GC. The total GC dosage is not uniform among patients or even for one patient over time, since the initial high GC dosage is gradually tapered off as the disease responds. High-dose GC therapy is used to treat serious illnesses, and GIO generally receives less attention than the original disease. Our data shows that fragility fractures are occurred much higher frequently than FRAX® would predict. Most importantly, the median observation period is much shorter than 10 years that is the anticipated observation period for FRAX® (Table 3).

Recently, patients with severe rheumatic disease show improved outcomes when treated with GCs and immunosuppressants. Since GIO can cause fragility fractures even in young patients with rheumatic disease, attention should be given to preventing GIO.

Our data shows that the patients with SLE are lower risk of fragility fractures than other rheumatic disease. This is attributed to the fact that most of SLE patients are younger and greater population of premenopausal women than other disease. In fact, it is reported that SLE itself is associated with low BMD or osteoporosis (Pineau et al., 2004) (Tang et al., 2013) (Sun et al., 2015). There are some reasons such as inflammation, vitamin D deficiency, and premature ovarian failure for risk of low BMD (Lin & Grossman, 2016). Those mechanisms are occurred in other rheumatic diseases than SLE and may also contribute to very high frequency of fragility fracture in this study.

In this retrospective study, there is no significant difference in fracture incidence between bisphosphonates prescription group and comparison group. Currently, bisphosphonate is the most preferred drug and has been proven the efficacy for GIOP in many studies (Saag et al., 1998) (Cohen et al., 1999) (Reid et al., 2000) (de Nijs et al., 2006) (Reid et al., 2009) (Stoch et al., 2009) (Fahrleitner-Pammer et al., 2009). However, the primary end point of these studies are BMD, not fracture incidence. In a post hoc analysis of the combined two studies and a follow up study, bisphosphonate reduced the vertebral fracture rates compared to the placebo group (Wallach et al., 2000) (Adachi et al., 2001). Although a meta-analysis found that bisphosphonate reduced the odds of spinal fracture by 24% in GIO patients [OR 0.76 (95% CI 0.37, 1.53)], this result was not significant (Homik et al., 2000).

There are all sorts of other reasons why bisphosphonate could not reduce the fragility fracture risk in our data. First, since the osteoporotic effect of GC is dose-dependent, it would not be surprising for the osteoporotic effect of high-dose GC therapy to overwhelm and effectively cancel out the effect of bisphosphonates. Second, the timing of the initial bisphosphonate treatment varied among the patients. Some started bisphosphonate treatment simultaneously with high-dose GC therapy, while others began taking bisphosphonates one month after high-dose GC treatment. The initial phase of GC therapy is a critical period for preventing GIO. Third, we conjecture the other reason, the adherence and persistence of bisphosphonates are usually poor. In observational studies, one year persistence rate of bisphosphonate is 27.9 to74.8% (Weycker et al., 2006) (Ideguchi et al., 2007) (Gallagher et al., 2008) (Cotte et al., 2010) (Hadji et al., 2012). Recent study reported that 80% of patients discontinued the bisphosphonates before completing 5 year treatment (LaFleur et al., 2015). The adherence to bisphosphonates in our study is unclear and able to be examined accurately. High-dose GC therapy is so high risk of the fragility fracture that the potentially non-adherence medicine may be insufficient. Another possible explanation for ineffectiveness of bisphosphonates on high-dose GC induced osteoporosis is based on reverse causality. We adjusted osteoporotic risk factor by using FRAX® as moderator variables. Nevertheless, we cannot eliminate the bias or the reverse causality derived from study design. Further work would be needed to assess the effects of bisphosphonate for preventing fragility fracture in patients undergoing high-dose GC therapy.

Our study found two risk factors for fragility fractures induced by high-dose GCs: a high FRAX® 10-year probability for a major osteoporotic fracture, and two or more cycles of high-dose GC therapy. Our ROC analysis found an optimal FRAX® cut-off of 8.3 for predicting fragility fractures, even though the AUC of the ROC was fairly low. Although the ACR's GIO guidelines define a FRAX® score of 10% or less as low-risk, we found that postmenopausal patients treated by high-dose GC therapy often suffered from fractures even if their FRAX® score was below 10% and they were treated with bisphosphonate. Therefore, postmenopausal patients, especially with a FRAX® score of 8.3% or more should be considered high-risk even if they are taking bisphosphonate. Although the use of FRAX® to assess GIO risk has been criticized (Compston, 2010) (Weinstein, 2011), our study shows the importance of FRAX® as a relative, not absolute, risk-assessment tool for GIO, and supports the use of FRAX® as a simple, comprehensive, and globally validated method to assess fracture risk.

Our study has some limitations. First, because the study was retrospective, our results might be explained by reverse causation as mentioned above. Second, our study has low power due to a small sample size.

Our study is the first to report the incidence of fractures with high-dose GC therapy in a real-world clinical setting. We found a very high incidence of fragility fractures in postmenopausal patients treated with high-dose GC.

Because of some bias, our data did not show the fracture prevention effect with bisphosphonate nor vitamin D in the patients underwent high-dose GC therapy. New anti-osteoporotic drugs other than bisphosphonate are available or will soon launched. Teriparatide showed better anti-osteoporotic effect than risedronate in GIO (Gluer et al., 2013) (Amiche et al., 2016). The clinical trial with denosumab in GIO is in progress, and the results are urgently needed. However, the studies with newer drugs are not also conducted with high-dose GC therapy. High-dose GC therapy is very high-risk for fragility fractures again. It is important to prioritize clinical trials of the anti-osteoporotic drugs, so that effective treatments can be used as soon as possible in the patients who need high-dose GC therapy.

Disclosure of interest

Goichi Kageyama, Takaichi Okano, Yuzuru Yamamoto, Keisuke Nishimura, Daisuke Sugiyama, Jun Saegusa, Goh Tsuji, Shunichi Kumagai, and Akio Morinobu declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author's contribution.

GK conceived of the study and involved in the overall study design and data acquisition and analysis and drafted the manuscript. TO, YY and KN contributed data acquisition. DS contributed data analysis. GT, JS and SK provided critical input on data interpretation. AM participated in its design, and helped draft the manuscript. All authors helped to critically revise the intellectual content of the manuscript and approved the final submission.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI grants 25461475 and Japan Osteoporosis Foundation grants.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI grants 25461475 and Japan Osteoporosis Foundation grants.

Reference

- Adachi J.D., Saag K.G., Delmas P.D., Liberman U.A., Emkey R.D., Seeman E., Lane N.E., Kaufman J.M., Poubelle P.E., Hawkins F., Correa-Rotter R., Menkes C.J., Rodriguez-Portales J.A., Schnitzer T.J., Block J.A., Wing J., McIlwain H.H., Westhovens R., Brown J., Melo-Gomes J.A., Gruber B.L., Yanover M.J., Leite M.O., Siminoski K.G., Nevitt M.C., Sharp J.T., Malice M.P., Dumortier T., Czachur M., Carofano W., Daifotis A. Two-year effects of alendronate on bone mineral density and vertebral fracture in patients receiving glucocorticoids: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled extension trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(1):202–211. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200101)44:1<202::AID-ANR27>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee, editor. Recommendations for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: 2001 updateon Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis, Arthritis and rheumatism. 2001;44(7):1496–1503. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200107)44:7<1496::AID-ART271>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. American College of Rheumatology Task Force on Osteoporosis Guidelines, Arthritis and Rheumatism 39(11) (1996) 1791–801. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Amiche M.A., Albaum J.M., Tadrous M., Pechlivanoglou P., Levesque L.E., Adachi J.D., Cadarette S.M. Efficacy of osteoporosis pharmacotherapies in preventing fracture among oral glucocorticoid users: a network meta-analysis Osteoporosis international. a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2016;27(6):1989–1998. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3476-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg K.M., Kunins H.V., Jackson J.L., Nahvi S., Chaudhry A., Harris K.A., Jr., Malik R., Arnsten J.H. Association between alcohol consumption and both osteoporotic fracture and bone density. Am. J. Med. 2008;121(5):406–418. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2002. Bone and Tooth Society of Great Britain, National Osteoporosis Society, Royal College of Physicians, Glucocorticoid-induced-osteoporosis guidelines for prevention and treatment. [Google Scholar]

- Canalis E., Mazziotti G., Giustina A., Bilezikian J.P. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: pathophysiology and therapy, Osteoporosis international. a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2007;18(10):1319–1328. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0394-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Levy R.M., Keller M., Boling E., Emkey R.D., Greenwald M., Zizic T.M., Wallach S., Sewell K.L., Lukert B.P., Axelrod D.W., Chines A.A. Risedronate therapy prevents corticosteroid-induced bone loss: a twelve-month, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(11):2309–2318. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199911)42:11<2309::AID-ANR8>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compston J. Management of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2010;6(2):82–88. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotte F.E., Fardellone P., Mercier F., Gaudin A.F., Roux C. Adherence to monthly and weekly oral bisphosphonates in women with osteoporosis, Osteoporosis international. a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2010;21(1):145–155. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0930-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Nijs R.N., Jacobs J.W., Lems W.F., Laan R.F., Algra A., Huisman A.M., Buskens E., de Laet C.E., Oostveen A.C., Geusens P.P., Bruyn G.A., Dijkmans B.A., Bijlsma J.W., Investigators S. Alendronate or alfacalcidol in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355(7):675–684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devogelaer J.P., Goemaere S., Boonen S., Body J.J., Kaufman J.M., Reginster J.Y., Rozenberg S., Boutsen Y. Evidence-based guidelines for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: a consensus document of the Belgian Bone Club, Osteoporosis international. A journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2006;17(1):8–19. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-2032-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrleitner-Pammer A., Piswanger-Soelkner J.C., Pieber T.R., Obermayer-Pietsch B.M., Pilz S., Dimai H.P., Prenner G., Tscheliessnigg K.H., Hauge E., Portugaller R.H., Dobnig H. Ibandronate prevents bone loss and reduces vertebral fracture risk in male cardiac transplant patients: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 2009;24(7):1335–1344. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher A.M., Rietbrock S., Olson M., van Staa T.P. Fracture outcomes related to persistence and compliance with oral bisphosphonates. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 2008;23(10):1569–1575. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- C.C. Gluer, F. Marin, J.D. Ringe, F. Hawkins, R. Moricke, N. Papaioannu, P. Farahmand, S. Minisola, G. Martinez, J.M. Nolla, C. Niedhart, N. Guanabens, R. Nuti, E. Martin-Mola, F. Thomasius, G. Kapetanos, J. Pena, C. Graeff, H. Petto, B. Sanz, A. Reisinger, P.K. Zysset, Comparative effects of teriparatide and risedronate in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in men: 18-month results of the EuroGIOPs trial, J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 28(6) (2013) 1355–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Grossman J.M., Gordon R., Ranganath V.K., Deal C., Caplan L., Chen W., Curtis J.R., Furst D.E., McMahon M., Patkar N.M., Volkmann E., Saag K.G. American College of Rheumatology 2010 recommendations for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Arthritis care & research. 2010;62(11):1515–1526. doi: 10.1002/acr.20295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadji P., Claus V., Ziller V., Intorcia M., Kostev K., Steinle T. GRAND: The German retrospective cohort analysis on compliance and persistence and the associated risk of fractures in osteoporotic women treated with oral bisphosphonates. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2012;23(1):223–231. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1535-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofbauer L.C., Rauner M. Minireview: live and let die: molecular effects of glucocorticoids on bone cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 2009;23(10):1525–1531. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbach K.A., Barrett-Connor E., Edelstein S.L., Holbrook T. Cigarette smoking and bone mineral density in older men and women. Am. J. Public Health. 1993;83(9):1265–1270. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.9.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homik J., Cranney A., Shea B., Tugwell P., Wells G., Adachi R., Suarez-Almazor M. Bisphosphonates for steroid induced osteoporosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2000;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ideguchi H., Ohno S., Hattori H., Ishigatsubo Y. Persistence with bisphosphonate therapy including treatment courses with multiple sequential bisphosphonates in the real world. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2007;18(10):1421–1427. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0406-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanis J.A., Johnell O., Oden A., Johansson H., McCloskey E. FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK, Osteoporosis international. a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2008;19(4):385–397. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0543-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanis J.A., Hans D., Cooper C., Baim S., Bilezikian J.P., Binkley N., Cauley J.A., Compston J.E., Dawson-Hughes B., El-Hajj Fuleihan G., Johansson H., Leslie W.D., Lewiecki E.M., Luckey M., Oden A., Papapoulos S.E., Poiana C., Rizzoli R., Wahl D.A., McCloskey E.V. F.I. Task Force of the, Interpretation and use of FRAX in clinical practice, Osteoporosis international. a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2011;22(9):2395–2411. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1713-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFleur J., DuVall S.L., Willson T., Ginter T., Patterson O., Cheng Y., Knippenberg K., Haroldsen C., Adler R.A., Curtis J.R., Agodoa I., Nelson R.E. Analysis of osteoporosis treatment patterns with bisphosphonates and outcomes among postmenopausal veterans. Bone. 2015;78:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T., Grossman J. Prevention and treatment of bone disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Current Treatment Options in Rheumatology. 2016;2(1):21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay R., Silverman S.L., Cooper C., Hanley D.A., Barton I., Broy S.B., Licata A., Benhamou L., Geusens P., Flowers K., Stracke H., Seeman E. Risk of new vertebral fracture in the year following a fracture. JAMA. 2001;285(3):320–323. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.3.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineau C.A., Urowitz M.B., Fortin P.J., Ibanez D., Gladman D.D. Osteoporosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: factors associated with referral for bone mineral density studies, prevalence of osteoporosis and factors associated with reduced bone density. Lupus. 2004;13(6):436–441. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu1036oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid D.M., Hughes R.A., Laan R.F., Sacco-Gibson N.A., Wenderoth D.H., Adami S., Eusebio R.A., Devogelaer J.P. Efficacy and safety of daily risedronate in the treatment of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis in men and women: a randomized trial. European Corticosteroid-Induced Osteoporosis Treatment Study. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 2000;15(6):1006–1013. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.6.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid D.M., Devogelaer J.P., Saag K., Roux C., Lau C.S., Reginster J.Y., Papanastasiou P., Ferreira A., Hartl F., Fashola T., Mesenbrink P., Sambrook P.N. H. investigators, Zoledronic acid and risedronate in the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (HORIZON): a multicentre, double-blind, double-dummy, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9671):1253–1263. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saag K.G., Emkey R., Schnitzer T.J., Brown J.P., Hawkins F., Goemaere S., Thamsborg G., Liberman U.A., Delmas P.D., Malice M.P., Czachur M., Daifotis A.G. Alendronate for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis Intervention Study Group, The New England journal of medicine. 1998;339(5):292–299. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807303390502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoch S.A., Saag K.G., Greenwald M., Sebba A.I., Cohen S., Verbruggen N., Giezek H., West J., Schnitzer T.J. Once-weekly oral alendronate 70 mg in patients with glucocorticoid-induced bone loss: A 12-month randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Rheumatol. 2009;36(8):1705–1714. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.081207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.N., Feng X.Y., He L., Zeng L.X., Hao Z.M., Lv X.H., Pu D. Prevalence and possible risk factors of low bone mineral density in untreated female patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015;2015:510514. doi: 10.1155/2015/510514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y., Nawata H., Soen S., Fujiwara S., Nakayama H., Tanaka I., Ozono K., Sagawa A., Takayanagi R., Tanaka H., Miki T., Masunari N., Tanaka Y. Guidelines on the management and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis of the Japanese Society for Bone and Mineral Research: 2014 update. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2014;32(4):337–350. doi: 10.1007/s00774-014-0586-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X.L., Griffith J.F., Qin L., Hung V.W., Kwok A.W., Zhu T.Y., Kun E.W., Leung P.C., Li E.K., Tam L.S. SLE disease per se contributes to deterioration in bone mineral density, microstructure and bone strength. Lupus. 2013;22(11):1162–1168. doi: 10.1177/0961203313498802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Staa T.P., Leufkens H.G., Abenhaim L., Zhang B., Cooper C. Oral corticosteroids and fracture risk: relationship to daily and cumulative doses. Rheumatology. 2000;39(12):1383–1389. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.12.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallach S., Cohen S., Reid D.M., Hughes R.A., Hosking D.J., Laan R.F., Doherty S.M., Maricic M., Rosen C., Brown J., Barton I., Chines A.A. Effects of risedronate treatment on bone density and vertebral fracture in patients on corticosteroid therapy. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2000;67(4):277–285. doi: 10.1007/s002230001146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts N.B., Lewiecki E.M., Miller P.D., Baim S. National Osteoporosis Foundation 2008 Clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis and the World Health Organization fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX): what they mean to the bone densitometrist and bone technologist. J. Clin. Densitom. 2008;11(4):473–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein R.S. Clinical practice. Glucocorticoid-induced bone disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365(1):62–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1012926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weycker D., Macarios D., Edelsberg J., Oster G. Compliance with drug therapy for postmenopausal osteoporosis, Osteoporosis international. a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2006;17(11):1645–1652. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]