Abstract

Objective

Among older persons, disability and functional decline are associated with increased mortality, institutionalization, and costs. To determine whether illnesses and injuries leading to an emergency department (ED) visit but not hospitalization are associated with functional decline among community-living older persons.

Methods

From a cohort of 754 community-living older persons who have been followed with monthly interviews for up to 14 years, we matched 813 ED visits without hospitalization (ED-only) to 813 observations without an ED visit or hospitalization (control). We compared the course of disability over the following 6 months between the 2 matched groups. To establish a frame of reference, we also compared the ED-only group with an unmatched group who were hospitalized after an ED visit (ED-hospitalized). Disability scores (range: 0 [lowest] to 13 [highest]) were compared using generalized linear models adjusted for relevant covariates. Admission to a nursing home and mortality were evaluated as secondary outcomes.

Results

The ED-only and control groups were well matched. For both groups, the mean age was 83.6 years, and 69% were female. The baseline disability scores were 3.4 and 3.6 in the ED-only and control group, respectively. Over the 6-month follow-up period, the ED-only group had significantly higher disability scores than the control group, with an adjusted risk ratio (RR) of 1.14 (95%CI, 1.09–1.19). Compared with participants in the ED-only group, those who were hospitalized after an ED visit had disability scores that were significantly higher (RR 1.17, 95%CI, 1.12–1.22). Both nursing home admissions (HR 3.11, 95%CI, 2.05–4.72) and mortality (HR 1.93, 95%CI 1.07–3.49) were also higher in the ED-only group versus control group over the 6-month follow-up period.

Conclusions

Although not as debilitating as an acute hospitalization, illnesses and injuries leading to an ED visit without hospitalization were associated with a clinically meaningful decline in functional status over the following 6 months, suggesting that the period after an ED visit represents a vulnerable time for community-living older persons.

INTRODUCTION

Background and Importance

Patients aged 65 years or older account for more than 15% of all emergency department (ED) visits each year in the United States,1 and most of these patients are discharged home.2 Among older persons, disability and functional decline are associated with increased mortality, institutionalization, and costs.3,4,5 The estimated additional cost of medical and long-term care for newly disabled older persons in the United States is $26 billion per year.6

Previous work has shown that illnesses and injuries leading to hospitalization are associated with functional decline.4,7–9 Prior studies have also suggested that older patients discharged from the ED may experience some functional decline, but these studies were limited by the absence of suitable comparison groups and by retrospective reports of pre-illness function.10–16

Goals of this Investigation

The objective of this study was to evaluate the burden of disability over a 6-month period in older persons who were discharged from the ED (ED-only) by comparing them with a matched control group (control) and with a group that was admitted to the ED and hospitalized (ED-hospitalized). We hypothesized that older persons who visited the ED and were discharged would experience a greater burden of disability over the following 6 months as compared with those who did not visit the ED, but a lower burden of disability as compared with those who were hospitalized. Admission to a nursing home and mortality were evaluated as secondary outcomes.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This study is part of the Yale Precipitating Events Project, an ongoing prospective, longitudinal study of 754 initially non-disabled, community-living persons aged 70 years or older. The study was designed to elucidate the epidemiology of disability, with the goal of informing the development of effective interventions to maintain and restore independent function. Methods of this longitudinal study have been described in detail elsewhere.8,17,18 Briefly, the cohort was assembled between March 1998 and October 1999 from a computerized list of 3157 age-eligible members of a large health plan in greater New Haven. Eligibility was determined during a screening telephone interview and was confirmed during an in-home assessment. 75.2% of the eligible members agreed to participate in the project, and persons who declined to participate did not significantly differ in age or sex from those who were enrolled. The Yale Human Investigation Committee approved the study protocol, and all participants provided informed consent.

Data Collection and Processing

From 1998 to 2012, participants completed comprehensive, home-based assessments at 18-month intervals and were interviewed monthly by telephone to reassess their functional status, ascertain intervening illnesses and injuries leading to ED visits and hospitalizations, and identify nursing home admissions and deaths. For participants with significant cognitive impairment, a proxy informant was interviewed using a rigorous protocol with demonstrated reliability and validity, as described elsewhere.19 During the comprehensive assessments, data were collected on demographic characteristics, chronic conditions, body mass index, cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, and physical frailty.

Definition of Variables

Age was measured in years at the time of the index ED visit. Nine self-reported, physician-diagnosed chronic conditions were assessed: hypertension, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, diabetes, fractures, arthritis, chronic lung disease, and cancer (excluding minor skin cancers). Cognitive impairment was defined as a score less than 24 on the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination.20 Depressive symptoms were defined as a score greater than or equal to 20 on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale.21 Body mass index (BMI) was assessed as self-reported weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.22 Physical frailty was defined on the basis of slow gait speed, as previously described.23

Assessment of Disability

Complete details regarding the assessment of disability are provided elsewhere.17–19,24 Briefly, during the monthly interviews, participants were asked, “At the present time, do you need help from another person to (complete the task)?” for each of the 4 basic activities (bathing, dressing, walking across a room, and transferring from a chair), 5 instrumental activities (shopping, housework, meal preparation, taking medications, and managing finances), and 3 mobility activities (walk 1/4 mile, climb flight of stairs, and lift/carry 10 pounds). For each of these 12 activities, disability was defined as the need for personal assistance or being unable to perform the activity. Participants were also asked about a fourth mobility activity, “Have you driven a car during the past month?” Participants who responded “No” were deemed to have stopped driving. To maintain consistency with the other activities, these participants were classified as being “disabled” in driving that month.35 The number of disabilities overall and for each functional domain (basic, instrumental, mobility) were summed.

Assessment of ED visits, Hospitalizations, Nursing Home Admissions, and Deaths

The primary source of information on ED visits and hospitalizations was linked Medicare claims data, which were available for nearly all hospitalizations and for ED visits among fee-for-service participants.25 Of the ED-only observations and ED-hospitalized observations, 605 (74.4%) and 619 (98.1%) were identified from the Medicare claims, respectively. For participants in managed Medicare, information on ED visits and some hospitalizations (i.e. those without a Medicare claim) was obtained during the monthly interviews. Participants were asked whether they had visited an ED or stayed at least overnight in a hospital since the last interview. Among a subgroup of 191 participants, we found that the accuracy of self-reported ED visits, compared with Medicare claims data, was high (κ=0.80, 95%CI, 0.78–0.82). The raw agreement was 98.4%. The accuracy of self-reported hospitalization, based on an independent review of hospital records, was also high (κ=0.92, 95%CI, 0.90–0.95). The raw agreement was 98.8%.26

Participants who reported visiting the ED were asked the primary reason for their visit. These self-reports were complemented by Medicare claims data when needed. The list of the visit reasons was independently reviewed by two physicians (JMN and WF), and the reasons were grouped into distinct diagnostic categories using a revised version of a previously published protocol,27 as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Reasons for Emergency Department Visitsa

| Diagnostic Categories | ED-only No. (%) |

ED-hospitalized No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Musculoskeletal | 253 (31.4) | 80 (12.7) |

| Cardiac | 86 (10.7) | 115 (18.3) |

| Gastrointestinal | 75 (9.3) | 74 (11.7) |

| Infectious | 73 (9.1) | 78 (12.4) |

| Difficulty ambulating | 48 (6.0) | 42 (6.7) |

| Pulmonary | 31 (3.9) | 56 (8.9) |

| Neurologic | 30 (3.7) | 49 (7.8) |

| Head & Neck | 28 (3.5) | 3 (0.4) |

| Renal/Genitourinary | 20 (2.5) | 14 (2.0) |

| Dermatologic | 18 (2.2) | 3 (0.5) |

| Toxic/Environmental | 6 (0.7) | 0 (0) |

| Psychiatric | 6 (0.7) | 6 (1.0) |

| Other medicalb | 131 (16.3) | 109 (17.3) |

The diagnostic categories are listed by decreasing frequency for the ED-only group. The ED-only group included 805 reasons for visits since 8 visits did not have a reason. The ED-hospitalized group included 630 reasons since 1 observation did not have a reason. Abbreviations: ED, emergency department

Other medical problems included unclassifiable complaints such as feeling “weak,” “tired,” or generally unwell, with no other specifying features.

Participants, or their proxies, were also asked whether they had been admitted to a nursing home during the past month. The accuracy of these reports was high when compared with Medicare claims data, with a sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 100%.8 Deaths were ascertained by review of the local obituaries and/or from a proxy during a subsequent telephone interview, with a completion rate of 100%.

Assembly of Analytic Sample

To test our hypotheses, we used a matched cohort design. This design reduces bias with little loss of precision and permits the use of generalized estimating equations (GEE), which accounts for the correlation of observations within each cluster of matched observations.28–30 We compared the course of disability over 6 months among 3 groups: those who had an ED visit but were not hospitalized (ED-only), a matched group who did not visit an ED (control), and an unmatched group who were hospitalized after an ED visit (ED-hospitalized). The pool of potential observations was not sufficiently large to permit concurrent matching for the ED-hospitalized group in addition to the control group.

Participants were included only if they had been living in the community immediately prior to their ED visit (or corresponding time point for the control group). To make full use of our longitudinal data, participants were allowed to contribute more than one qualifying ED-only or ED-hospitalized event, but only the first event was included from a specific 18-month interval, which was the time period between the comprehensive assessments. This combination of a participant and their event within an 18-month interval defined an “observation” and was our unit of analysis. Similarly, only one control observation per participant was permitted within a specific 18-month interval.

To assemble the control group, we used a SAS macro31 to sequentially match each ED-only observation with an unexposed, or control, observation on the following four features: (1) sex; (2) participant age (± 4 years) at the time of ED visit; (3) number of disabilities (± 1) out of the 13 possible in the month prior to the ED visit; and (4) number of months since the previous comprehensive assessment. The analytic sample included 813 observations (from 430 participants) in the ED-only group, 813 observations (from 442 participants) in the control group, and 631 observations (from 390 participants) in the ED-hospitalized group. One hundred twenty-one participants had observations in both the ED-only and Control groups, 97 in both the ED-only and ED-hospitalized groups, and 139 in all the 3 groups.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the number of disabilities in the 13 basic, instrumental, and mobility activities during 6 months following the ED visit, hospitalization, or corresponding time point for the control group. Hereafter, we refer to this time-point as the index month. To determine whether our findings were consistent across these three functional domains, we also evaluated the number of disabilities in the 4 basic, 5 instrumental, and 4 mobility activities, respectively. While there is some debate about whether these activities should be considered on an ordinal or interval scale,32 we have chosen to analyze them on an interval scale as in prior studies.8 We chose the 6-month time period as it has previously been used when evaluating disability following hospitalization.33 As secondary outcomes, we evaluated nursing home admissions and deaths over the 6-month period following the index month.

Statistical analysis

The reasons for the ED visits were tabulated. Demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized by means with standard deviations and frequencies with proportions for the ED-only group, the matched control group, and the unmatched ED-hospitalized group.

Because each outcome represents a count, we fit Poisson GEE models to evaluate associations between the two primary comparison groups (ED-only and control) and disability scores over the 6 months of follow-up. The GEE Poisson models were adjusted for the 4 matching criteria, non-white race, education< 12 years, living situation (alone versus with others), number of chronic conditions, body mass index, cognitive impairment (MMSE<24), depressive symptoms (CES-D≥20), physical frailty, and calendar year. Based on prior recommendations,34 the model adjusts for matching variables to address residual confounding and censoring. A compound symmetry covariance structure accounted for correlations among multiple intervals from the same participant and matching between the ED-only and control groups. These models yielded adjusted relative risks (RR), which denote the increase in disability burden over the 6-month follow-up period for the ED-only group relative to the control group. These analyses were repeated for comparisons between the ED-only and unmatched ED-hospitalized groups. All models were checked for fit using the Quasi-information Criterion (QIC).

For the secondary outcomes, we plotted the percentage of observations with a nursing home stay and the percentage of reported deaths in the 6 months following the index month. We then used multivariable Cox regression models to assess the independent associations between exposure to ED-only (versus matched control) or ED-hospitalized (versus ED-only) and time to nursing home admissions and death, respectively, while adjusting for the previously described set of covariates. The correlation among multiple intervals from the same participant for the nursing home outcome was accounted for as a cluster, while matching between the ED-only and control group was accounted for using a conditional model.

All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4), and P < 0.05 (2-tailed) was used to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Table 1 provides the reason for ED visits for the ED-only and the ED-hospitalized groups. The most common reasons for an ED visit in both groups were musculoskeletal complaints, cardiac complaints, and “other” medical problems, such as feeling weak, tired, or unwell.

Table 2 provides the characteristics of the three groups. As expected, the ED-only and control groups were well matched on age, sex, number of disabilities, and number of months since the prior comprehensive assessment. The mean age in both groups was 83.6 years, and 68.9% were female. The baseline disability scores were 3.4 and 3.6 in the ED-only and control groups, respectively.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Analytic Samplea

| Characteristics | Control N=813 |

ED-only N=813 |

ED-hospitalized N=631 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean, (SD) | 83.6 (5.6) | 83.6 (5.7) | 84.4 (5.6) |

| Female sex, no., (%) | 560 (68.9) | 560 (68.9) | 399 (63.2) |

| Non-white, no., (%) | 97 (11.9) | 85 (10.5) | 76 (12.0) |

| Did not complete high school, no., (%) | 278 (34.2) | 249 (30.6) | 229 (36.3) |

| Lives alone, no., (%) | 326 (40.1) | 372 (45.8) | 292 (46.3) |

| Months since prior comprehensive assessment, mean, (SD) | 7.7 (5.3) | 7.7 (5.3) | 7.4 (5.1) |

| No. of disabilities, mean, (SD) | 3.6 (3.4) | 3.4 (3.3) | 4.3 (3.5) |

| No. of chronic conditionsb, mean, (SD) | 2.3 (1.3) | 2.1 (1.2) | 2.4 (1.3) |

| Cognitive impairmentc, no., (%) | 132 (16.2) | 159 (19.6) | 152 (24.1) |

| Depressive symptomsd, no., (%) | 164 (20.2) | 149 (18.3) | 128 (20.3) |

| Body mass indexe, mean, (SD) | 26.5 (5.1) | 26.3 (5.7) | 26.2 (5.1) |

| Frailtyf, no., (%) | 429 (52.8) | 415 (51.1) | 404 (64.0) |

The analytic sample included 813 observations (from 442 participants) in the control group, 813 observations (from 430 participants) in the ED-only group, and 631 observations (from 390 participants) in the ED-hospitalized group.

Includes hypertension, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, diabetes, fractures, arthritis, chronic lung disease, and cancer (excluding minor skin cancers).

Defined as score <24 on the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination.

Defined as score ≥20 on the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale.

Body mass index: weight (kg)/height (m)2

Defined on the basis of slow gait speed, as described in Methods.

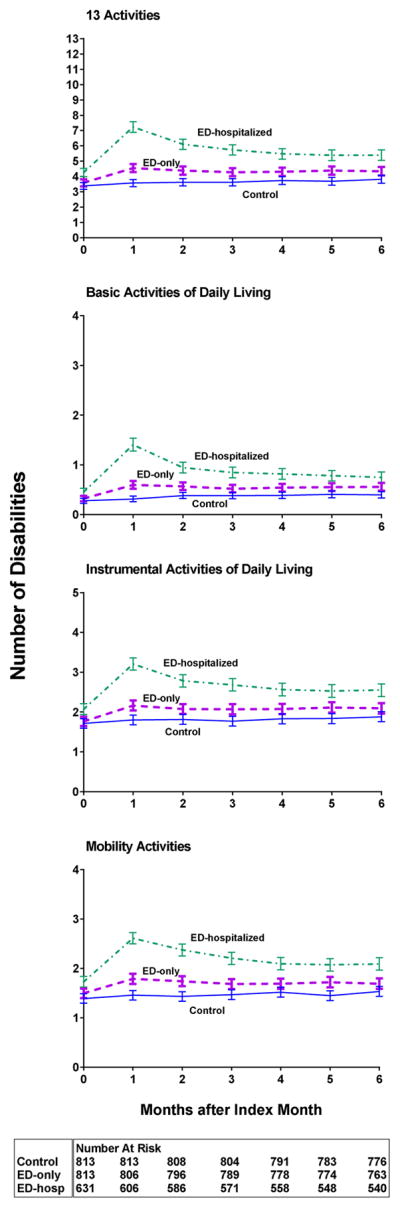

Figure 1A shows the disability scores in all 13 activities over the 6-month follow-up period. Throughout the follow-up period, the ED-only group had disability scores that were higher than the control group but lower than the ED-hospitalized group. In the longitudinal model, the ED-only group had significantly higher overall disability scores than the control group, with an adjusted risk ratio (RR) of 1.14 (95%CI, 1.09–1.19). Compared with participants in the ED-only group, those who were hospitalized after an ED visit had disability scores that were significantly higher, with an adjusted RR of 1.17 (95%CI, 1.12–1.22). Comparable results were observed for each of the 3 functional domains (basic, instrumental and mobility activities), as shown in Figure 1B–1D and Table 3.

Figure 1.

Course of Disability by Study Group. Month 0 represents the interview immediately preceding the ED visit and corresponding time for the matched control (as described in the methods). The bars denote 95% confidence intervals.

Table 3.

Adjusted Risk Ratio of Disability Burden Over 6-month Follow-up Period for Pairwise Comparisonsa

| Disability Burden | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| ED-only vs. Control | ED-hospitalized vs. ED-only | |||

|

| ||||

| RR | 95%CI | RR | 95%CI | |

| Composite 13-items | 1.14 | 1.09 – 1.19 | 1.17 | 1.12 – 1.22 |

| 4 ADLb | 1.37 | 1.22 – 1.55 | 1.37 | 1.25 – 1.50 |

| 5 IADc | 1.11 | 1.05 – 1.17 | 1.14 | 1.09 – 1.20 |

| 4 Mobilityd | 1.10 | 1.05 – 1.16 | 1.12 | 1.08 – 1.17 |

Values denote the relative increase in disability burden over the 6-month follow-up period for the two comparison groups. For each of these 13 activities, disability was defined as the need for personal assistance or unable to do. The number of disabilities overall and for each group of activities (basic, instrumental, mobility) were summed. Abbreviations: RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval.

ADLs (activities of daily living) included bathing, dressing, walking across a room, and transferring from a chair.

IADLs (instrumental activities of daily living) included shopping, housework, meal preparation, taking medications, and managing finances.

Mobility activities included walking 0.40 km, climbing one flight of stairs, lifting and carrying 4.5 kg, and driving a car in the past month.

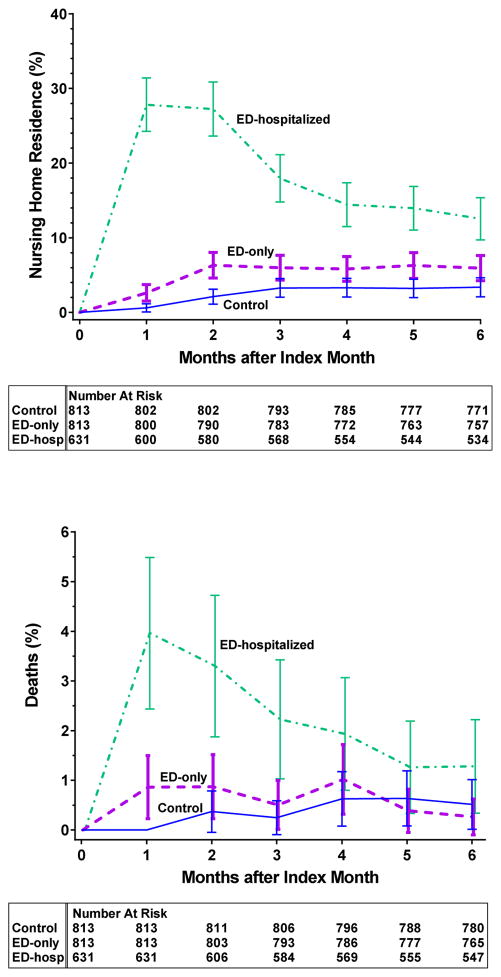

Figure 2A provides descriptive results on the percentage of participants living in a nursing home during the 6-month follow-up period according to study group. Nursing home utilization was highest in the ED-hospital group, intermediate in the ED-only group, and lowest in the control group. In the multivariable analysis, nursing home stays were more likely in the ED-only group than the control group (hazard ratio [HR] 3.11, 95%CI 2.05–4.72) and in the ED-hospitalized group than the ED-only group (HR 3.57, 95%CI 2.83–4.50). Figure 2B provides descriptive results on the percentage of participants dying during the 6-month follow-up period according to study group. On average, mortality was highest in the ED-hospitalized group, intermediate in the ED-only group, and lowest in the control group. In the multivariable analysis, the likelihood of dying was greater in the ED-only group compared to the control group (HR 1.93, 95%CI 1.07–3.49) and in the ED-hospitalized group compared to the ED-only group (HR 3.11, 95%CI 2.05–4.72).

Figure 2.

Secondary Outcomes by Study Group. Point estimates represent unadjusted values, while the bars denote 95% confidence intervals. The number at risk refers to observations, not participants, as described in the text.

LIMITATIONS

Our study has important limitations. First, because the study was observational, the associations identified cannot be interpreted as causal. However, the frequency of our assessments increases the likelihood that the intervening illnesses and injuries leading to an ED visit were temporally related to the worsening course of disability, an important criterion for causality. Second, to make full use of our longitudinal data, we analyzed observations, rather than participants. Rigorous methods were used to match the ED-only and control group intervals and to reduce bias and collinearity among observations. The multiple entries for a single participant could be construed as posing a violation of the independence assumption, but rigorous statistical methods were used to account for within-participant correlations. Lastly, our cohort was limited to members of a single health plan in a small urban area, and may not be generalizable to other areas. The demographics of our cohort, however, were similar to those of the U.S. as a whole, with the exception of race, and the generalizability of our results is enhanced by the high participation rate, which was over 75%.

DISCUSSION

In this matched cohort study of community-living older persons, we found that participants who presented to the ED and were discharged had a worse functional course and higher nursing home utilization and mortality over a 6-month period than participants who did not present to the ED, but they had better outcomes than those who presented to the ED and were hospitalized. These results were observed for all three functional domains and persisted despite adjustment for multiple potential confounders. Collectively, our findings provide strong evidence that illnesses and injuries leading to an ED visit without hospitalization have serious adverse consequences among community-living older persons.

Much of the previous work on functional outcomes after an acute illness or injury has focused on the course of disability after hospitalization, but less is known about the functional consequences of an illness or injury leading to an ED visit without hospitalization. Our findings are consistent with those of prior studies showing that older persons who present to an ED with traumatic injuries experience a short-term decline in function of 7% to 42%.10–12,14 Instead of focusing on a single presenting problem, our study included ED visits for a large number of reasons, the most common being musculoskeletal, which represented almost one third of the ED-only visits. Although beyond the scope of the current study, determining whether the course of disability after an ED visit differs according to the presenting problem should be the focus of future research.

Our findings are also consistent with studies in the U.S. and Canada, which found that 20% to 25% of older ED patients experience some functional decline in the 6 months after an ED visit.13,15 These studies, however, were limited by the absence of suitable comparison groups and by retrospective reports of pre-illness function. In contrast, our study included a matched comparison group of older persons with no ED visit and included prospective reports of pre-illness function. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to evaluate the course of disability following an ED visit in a general cohort of community-living older persons in the U.S.

In contrast to prior studies, the current study included nursing home utilization and mortality as additional outcomes. The higher rates of nursing home stays and mortality among participants with an ED visit but not hospitalization strengthen our primary finding of increased disability in the ED-only group, and support the clinical significance of the observed functional decline.

Additional strengths of the current study include its prospective, longitudinal design, high participation rate, and minimal attrition for reasons other than death; the rigorous ascertainment of ED visits and hospital admissions through claims data supplemented by self-reported information with demonstrated validity; the monthly assessments of disability with 13 basic, instrumental and mobility activities for more than 14 years; and adjustment for a comprehensive set of potential confounders, which were updated every 18 months. Although residual confounding is always a possibility in an observational study, participants in the ED-only group and control group were well matched on the most important prognostic characteristics, including pre-ED function.

Previous work has shown that disability results from a combination of preexisting vulnerability (such as frailty and cognitive impairment) and subsequent precipitating events, including hospitalization.4,7 The results of the current study indicate that illnesses and injuries leading to an ED visit without hospitalization have serious adverse consequences, including worsening disability and increased nursing home utilization and death. These results provide strong evidence that an ED visit often acts as precipitating event of disability, and they suggest that the period after an ED visit represents a vulnerable time for community-living older persons. Our findings should spur ongoing efforts 35–38 to provide functional assessments and appropriate interventions for older patients who present to the ED, and they support the need for further research to evaluate new models of care for this population.

Acknowledgments

We thank Denise Shepard, BSN, MBA, Andrea Benjamin, BSN, Barbara Foster, and Amy Shelton, MPH for assistance with data collection; Wanda Carr, Geraldine Hawthorne, BS, and Evelyne Gahbauer, MD, MPH, for assistance with data entry and management; Peter Charpentier, MPH for design and development of the study database and participant tracking system; Joanne McGloin, MDiv, MBA for leadership and advice as the Project Director; the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale University School of Medicine, the John A. Hartford Foundation Centers of Excellence in Geriatric Medicine and Training, the National Institute on Aging for financial support, and our participants for sharing information about their health and function over the past 18 years.

Financial support: This study was supported in part by the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale School of Medicine (#P30AG021342) from the National Institute on Aging, by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (R37AG17560), and by a grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation Centers of Excellence in Geriatric Medicine and Training. Dr. Gill is the recipient of an Academic Leadership Award (K07AG043587) from the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Meetings: Abstract presented at SAEM Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA, May 2016

Conflicts of Interest: None

Author Contributions Statement: TG conceived and designed the study. TG supervised the conduct of the study. JMN, WF, LH, LLS, and HGA conducted data processing and analysis. JMN drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. JMN takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 Emergency Department Summary Tables. Table 2. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2010_ed_web_tables.pdf.

- 2.Aminzadeh F, Dalziel WB. Older adults in the emergency department: a systematic review of patterns of use, adverse outcomes, and effectiveness of interventions. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39(3):238–247. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.121523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried LP, Guralnik JM. Disability in older adults: evidence regarding significance, etiology, and risk. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(1):92–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill TM, Allore HG, Gahbauer EA, Murphy TE. CHange in disability after hospitalization or restricted activity in older persons. JAMA. 2010;304(17):1919–1928. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan L, Beaver S, Maclehose RF, Jha A, Maciejewski M, Doctor JN. Disability and health care costs in the Medicare population. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(9):1196–1201. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.34811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guralnik JM, Alecxih L, Branch LG, Wiener JM. Medical and Long-Term Care Costs When Older Persons Become More Dependent. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(8):1244–1245. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Han L, Allore HG. The role of intervening hospital admissions on trajectories of disability in the last year of life: prospective cohort study of older people. The BMJ. 2015;350:h2361. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill TM, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG. Association of Injurious Falls With Disability Outcomes and Nursing Home Admissions in Community-Living Older Persons. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(3):418–425. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, Guo Z. HOspitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA. 2004;292(17):2115–2124. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.17.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilber ST, Blanda M, Gerson LW, Allen KR. Short-term functional decline and service use in older emergency department patients with blunt injuries. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(7):679–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shapiro MJ, Partridge RA, Jenouri I, Micalone M, Gifford D. Functional decline in independent elders after minor traumatic injury. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(1):78–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb00560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Platts-Mills TF, Flannigan SA, Bortsov AV, et al. Persistent Pain Among Older Adults Discharged Home From the Emergency Department After Motor Vehicle Crash: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67(2):166–176. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hustey FM, Mion LC, Connor JT, Emerman CL, Campbell J, Palmer RM. A brief risk stratification tool to predict functional decline in older adults discharged from emergency departments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(8):1269–1274. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sirois M-J, Émond M, Ouellet M-C, et al. Cumulative incidence of functional decline after minor injuries in previously independent older Canadian individuals in the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(10):1661–1668. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Provencher V, Sirois M-J, Ouellet M-C, et al. Decline in Activities of Daily Living After a Visit to a Canadian Emergency Department for Minor Injuries in Independent Older Adults: Are Frail Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment at Greater Risk? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(5):860–868. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimmer K, Beaton K, Kumar S, et al. Estimating the risk of functional decline in the elderly after discharge from an Australian public tertiary hospital emergency department. Aust Health Rev. 2013;37(3):341–347. doi: 10.1071/AH12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gill TM, Desai MM, Gahbauer EA, Holford TR, Williams CS. Restricted activity among community-living older persons: incidence, precipitants, and health care utilization. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(5):313–321. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-5-200109040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardy SE, Gill TM. Recovery from disability among community-dwelling older persons. JAMA. 2004;291(13):1596–1602. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gill TM, Hardy SE, Williams CS. Underestimation of disability in community-living older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(9):1492–1497. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index. J Aging Health. 1993;5(2):179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardy SE, Gill TM. Factors associated with recovery of independence among newly disabled older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(1):106–112. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG, Han L. Transitions between frailty states among community-living older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(4):418–423. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Murphy TE, Han L, Allore HG. Risk Factors and Precipitants of Long-Term Disability in Community Mobility A Cohort Study of Older Persons. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(2):131–140. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-2-201201170-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gill TM, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG. The course of disability before and after a serious fall injury. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(19):1780–1786. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gill TM, Allore H, Holford TR, Guo Z. The development of insidious disability in activities of daily living among community-living older persons. Am J Med. 2004;117(7):484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Pahor M, Corti MC, Havlik RJ. Hospital diagnoses, Medicare charges, and nursing home admissions in the year when older persons become severely disabled. JAMA. 1997;277(9):728–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ming K, Rosenbaum PR. A Note on Optimal Matching With Variable Controls Using the Assignment Algorithm. J Comput Graph Stat. 2001;10:455–463. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ming K, Rosenbaum PR. Substantial gains in bias reduction from matching with a variable number of controls. Biometrics. 2000;56(1):118–124. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenland S. Modelling risk ratios from matched cohort data: an estimating equation approach. Appl Stat. 1994;43:223–232. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bergstralh EJ, Kosanke JL, Jacobsen SJ. Software for optimal matching in observational studies. Epidemiol Camb Mass. 1996;7(3):331–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lazaridis EN, Rudberg MA, Furner SE, Cassel CK. Do activities of daily living have a hierarchical structure? An analysis using the longitudinal study of aging. J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M47–M51. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barry LC, Murphy TE, Gill TM. Depression and Functional Recovery After a Disabling Hospitalization in Older Persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(7):1320–1325. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03453.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sjölander A, Greenland S. Ignoring the matching variables in cohort studies - when is it valid and why? Stat Med. 2013;32(27):4696–4708. doi: 10.1002/sim.5879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carpenter CR, Shelton E, Fowler S, et al. Risk factors and screening instruments to predict adverse outcomes for undifferentiated older emergency department patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(1):1–21. doi: 10.1111/acem.12569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hwang U, Morrison RS. The Geriatric Emergency Department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(11):1873–1876. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hwang U, Shah MN, Han JH, Carpenter CR, Siu AL, Adams JG. Transforming emergency care for older adults. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2013;32(12):2116–2121. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah MN, Caprio TV, Swanson P, et al. A novel emergency medical services-based program to identify and assist older adults in a rural community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(11):2205–2211. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]