ABSTRACT

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) represents a reemerging global threat to human health. Recent outbreaks across Asia, Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean have prompted renewed scientific interest in this mosquito-borne alphavirus. There are currently no vaccines against CHIKV, and treatment has been limited to nonspecific antiviral agents, with suboptimal outcomes. Herein, we have identified β-d-N4-hydroxycytidine (NHC) as a novel inhibitor of CHIKV. NHC behaves as a pyrimidine ribonucleoside and selectively inhibits CHIKV replication in cell culture.

KEYWORDS: Chikungunya virus, replicon, antiviral agents, nucleoside analogs

TEXT

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), a mosquito-borne alphavirus, is considered a reemerging threat to global human health. Recent outbreaks in La Reunion, the Caribbean, and Southeast Asia have raised concerns over the control of CHIKV. Changes in mosquito vector spread, global travel, human population growth, and climate change are some of the factors considered to have played a role in the increased incidence and prevalence of CHIKV infection (1, 2). CHIKV infection is associated with an acute febrile phase, followed by a chronic arthralgic phase that can last from weeks to years. In infants, acute chikungunya infection can lead to neuroencephalopathy and lifelong consequences. CHIKV tropism is largely assigned to macrophages and hepatocytes, although infection of other cell types and organs has not been ruled out (3, 4). There are currently no licensed vaccines or antiviral agents with specific mechanisms available for the treatment or prevention of chikungunya virus infection. To date, individuals infected with this virus are treated with broadly acting agents with suboptimal outcomes (5–7). CHIKV has a roughly 11.8-kb RNA genome that codes for four nonstructural and six structural proteins. Nonstructural protein 4 (NSP4), the viral-RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, is essential for synthesis of negative-sense and positive-sense viral RNAs and thus represents an important antiviral drug target (8).

The development of infectious clones and replicon cell lines for CHIKV has facilitated the discovery of small molecules that target specific steps of the viral replication cycle. To date, several studies have identified small-molecule inhibitors that inhibit CHIKV replication in cell culture (9–14). Some nucleoside analogs, such as ribavirin, have also been shown to interfere with CHIKV replication. Ribavirin is a broadly acting agent used for the treatment of other viral infections, such as hepatitis C (15). More recently, favipiravir, an effective antiviral agent against several RNA viruses, was reported to inhibit CHIKV replication in vitro (12). Interestingly, it was shown that favipiravir selected for resistance-associated mutations in NSP4. Although this suggests that NSP4 is the target of this antiviral agent, the precise mechanism of inhibition remains unknown (12).

In this study, we identify and characterize a nucleoside analog, β-d-N4-hydroxycytidine (NHC), which has been reported previously by our group to affect hepatitis C virus (16). Herein, we examine the impact of NHC on CHIKV replication in terms of antiviral activity, toxicity, intracellular metabolism, and mechanism of action.

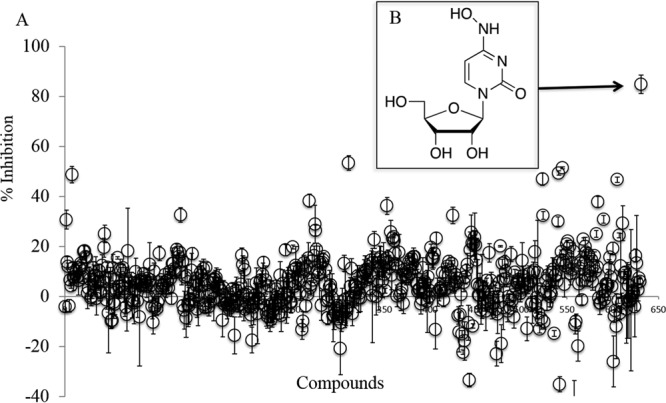

In our search for a nucleoside analog that could inhibit the CHIKV replicon, we evaluated over 600 compounds from our in-house small-molecule library. Compound evaluation was performed in a CHIKV replicon cell culture system essentially as previously described (17). The focused library was prescreened for toxicity, and compounds were evaluated at nontoxic concentrations. Briefly, Huh-7 cells stably transfected with the CHIKV replicon, which harbors a Renilla luciferase readout, were seeded at a density of 5,000 cells/well and preincubated at 37°C for 2 h before the addition of a 10 μM concentration of the compound in triplicate. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added as a negative control. The effect of each compound was evaluated after 48 h using a Renilla luciferase assay kit (Promega, USA). For dose-response studies, 3-fold dilutions of each compound were added, with the highest concentration being 30 μM. Ribavirin and favipiravir were used as positive controls. The scatter plot depicted in Fig. 1A shows the results of evaluation of the initial compound at 10 μM. We identified the nucleoside analog NHC (Fig. 1B) as a novel anti-CHIKV agent. Further evaluation confirmed that NHC inhibited CHIKV replicon activity and that the 50% effective concentration (EC50) was 0.8 μM in the Huh-7–CHIKV replicon cell line. Similar results were obtained with the replicon in BHK-21 cells (Table 1). This inhibition appeared to be more potent than that of the control nucleoside analogs favipiravir and ribavirin, previously described to have anti-CHIKV activity (12, 17). A continuous-treatment assay was conducted to evaluate the antiviral activity of the compound against infectious CHIKV replication in Vero cells (18). Briefly, monolayers of Vero cells were treated with different concentrations of the compound, starting from the maximum nontoxic dose. Concurrently, cells were infected with CHIKV belonging to the East/Central/South African (ECSA) or Asian genotype at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. After 2 h of incubation, the supernatant was replaced with medium containing the corresponding concentration of inhibitor. The plate was then kept at 37°C and examined daily for the presentation of cytopathic effect. After 48 h, the supernatants were collected and the CHIKV yields were evaluated using quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (q-RT-PCR) as described previously (19). We observed that both CHIKV genotypes were inhibited at similar potencies, with an EC50 of 0.2 μM (Table 1). No cytotoxicity was observed for NHC in the Huh-7 cell culture system when we tested NHC at up to 100 μM using standard 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays. The 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) values for NHC were determined to be 30.6 μM, 7.7 μM, and 2.5 μM in peripheral blood mononuclear (PBM), Vero, and CEM cells, respectively.

FIG 1.

Evaluation of small molecules for anti-CHIKV activity. (A) Small molecules were evaluated in Huh-7–CHIKV replicon cell culture. A 10 μM concentration of each compound was incubated with 5,000 cells/well in triplicate 96-well plates for 48 h at 37°C. The percent inhibition of the Renilla luciferase signal (± the standard deviation [SD]) was calculated as normalized to that in no-compound control lanes. The scatter plot represents percent inhibition data for 631 compounds. Only one compound, namely, β-d-N4-hydroxycytidine (NHC; indicated with a black arrow), was found to inhibit the replicon by over 80%. (B) Chemical structure of the NHC compound.

TABLE 1.

Anti-CHIKV effect of nucleoside analogs

| Compound | EC50 (μM)c |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huh-7–CHIKV replicon | BHK-21–CHIKV replicon | CHIKV infectious model (Asiana) | CHIKV infectious model (ECSAb) | |

| NHC | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| Favipiravir | 12.7 ± 1.6 | 22.5 ± 4.7 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Ribavirin | 16.8 ± 2.2 | 7.8 ± 2.2 | ND | ND |

Asian strain CNR20235.

ECSA strain LR 2006 OPY1.

Cell-based EC50s are the averages from two to four replicates ± standard deviations. ND, not determined.

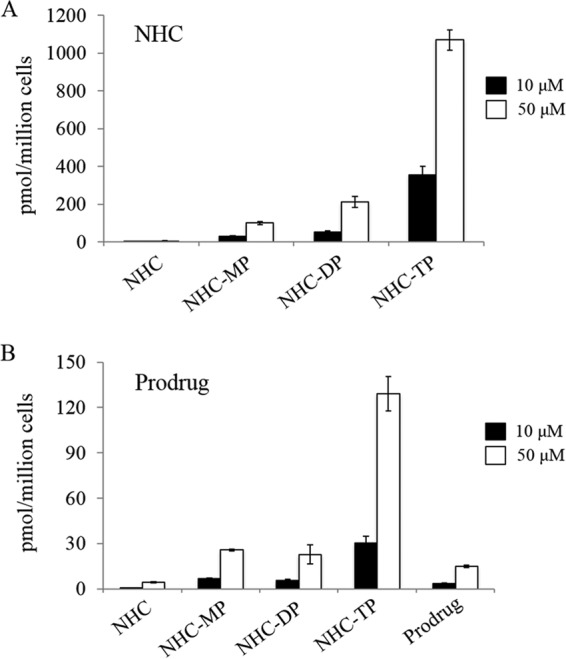

We next evaluated the intracellular metabolism of NHC. We incubated a 10 μM or 50 μM concentration of the NHC parent nucleoside in Huh-7 cells essentially as described previously (20). Briefly, Huh-7 cells were seeded at 1 × 106 cells per well in 12-well plates and incubated with NHC for 4 h. Cells were subsequently washed and analyzed using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectroscopy (LC-MS/MS). Levels of the parent NHC, along with each of the 5′-mono-, di-, and triphosphorylated metabolites, were measured. Under these conditions, small amounts of NHC-monophosphate (MP) and NHC-diphosphate (DP) were observed, while NHC-triphosphate (TP) remained the most abundant metabolite (Fig. 2A). It is worth noting that at 10 μM, the synthesized McGuigan phosphoramidate prodrug of NHC showed only low levels of inhibition (<30%) in CHIKV replicon cell experiments. LC-MS/MS assays revealed that compared to the parent NHC, the prodrug NHC produced far lower levels of all detected metabolites (Fig. 2B). Specifically, incubation of 10 μM parent NHC generated 355 pmol/million cells of NHC-TP, while incubation of 10 μM prodrug NHC generated 30 pmol/million cells (an ∼12-fold difference). Incubation of 50 μM parent NHC generated 1,100 pmol/million cells of NHC-TP, while incubation of 50 μM prodrug NHC generated 130 pmol/million cells (an ∼8-fold difference) (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Intracellular metabolism of the parent NHC and the prodrug. Huh-7 cells were incubated with 10 μM (black bars) or 50 μM (white bars) NHC (A) or a McGuigan phosphoramidate prodrug of NHC (B) for 4 h at 37°C. Intracellular levels of the parental compounds and phosphorylated metabolites were measured using LC-MS/MS. Each measurement was repeated in triplicate, and results are means ± SD. MP, monophosphate; DP, diphosphate; TP, triphosphate.

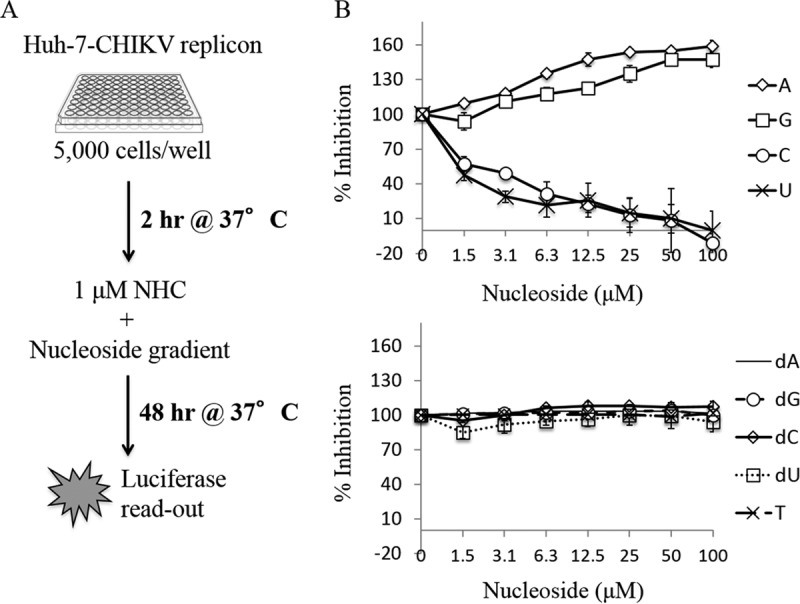

In order to shed light on the mechanism of action of NHC, we next evaluated whether NHC-mediated inhibition of the CHIKV replicon could be abrogated by the addition of exogenous nucleosides. Huh-7–CHIKV replicon cells were treated with 1 μM NHC together with 0 to 100 μM adenosine (A), cytidine (C), guanosine (G), uracil (U), 2′-deoxyadenosine (dA), 2′-deoxycytidine (dC), 2′-deoxyguanosine (dG), 2′-deoxyuridine (dU), or thymidine (T) (Fig. 3A). Percent inhibition in the presence of exogenous nucleosides was normalized to that of the sample containing 1 μM NHC alone (representing 100% inhibition) and to the no-NHC and no-nucleoside negative controls (representing 0% inhibition). We observed that the addition of dA, dC, dG, dU, or T had no impact on the replicon (Fig. 3B, lower panel), while the addition of pyrimidines C and U abrogated inhibition (Fig. 3B, top panel). These data suggest that NHC behaves as a pyrimidine analog, considering that its inhibition could be either directly or indirectly abrogated only with the addition of natural pyrimidine ribonucleosides. Finally, we noted that A and G contributed to replicon inhibition both in the presence and in the absence of NHC (Fig. 3B and data not shown), presumably by affecting cell viability. This observation was consistent with those of previous reports in other cell settings with regard to the impact of exogenous G or A on the induction of apoptosis (21, 22).

FIG 3.

Effect of exogenous nucleosides on NHC-mediated inhibition of the CHIKV replicon. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental layout. Huh-7–CHIKV replicon cells were incubated for 48 h with 1 μM NHC and increasing concentrations of exogenous ribonucleosides (B, top panel) or 2′-deoxyribonucleosides or thymidine (B, bottom panel). Percent inhibition was normalized to 100% in the presence of 1 μM NHC alone. The x axis represents the nucleoside concentration gradient. The y axis represents percent inhibition of the CHIKV replicon as measured via Renilla luciferase activity. Each experiment was repeated in triplicate, and results are means ± SD.

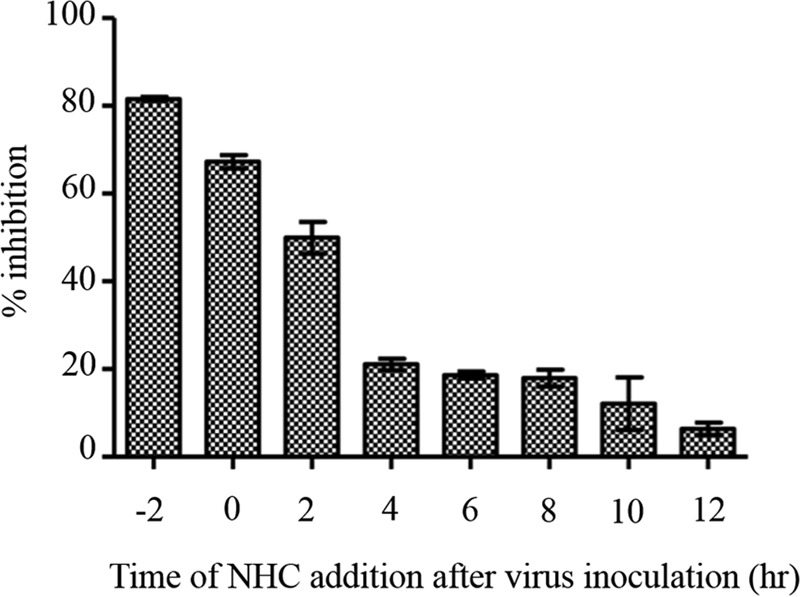

Finally, a time-of-addition experiment using infectious CHIKV (Asian genotype) was performed essentially as previously described (23, 24). Briefly, 0.3 μM NHC was added to Vero cell monolayers before, at the same time, or at various time points after virus infection at an MOI of 1; the compound was present until samples were harvested at 48 h postinfection. Virus yield was measured as described above. We observed that the highest level of inhibition occurred when NHC was added before virus infection; however, high levels of inhibition were sustained up to an additional 2 h postinoculation (Fig. 4). In contrast, when NHC was added at 4 h postinfection or later, only ∼20% inhibition was observed. Combined, our data suggest that NHC has little or no effect on CHIKV entry; instead, it acts as an early-stage inhibitor of CHIKV replication.

FIG 4.

Time-of-addition assay for the NHC compound. Vero cells were treated with 0.3 μM NHC either before, at the same time (time zero), or after CHIKV infection at an MOI of 1. A virus yield reduction assay was subsequently performed to determine percent inhibition of virus production. Each time point measurement was repeated in triplicate, and results are means ± SD.

Herein, we have characterized NHC as a novel inhibitor of CHIKV through replicon- and infectious-virus-based assays. Although the precise mechanism of action of this pyrimidine analog remains to be determined, our data allow us to speculate on several possible inhibitory pathways. Considering its high intracellular levels, the NHC-TP metabolite may directly target the viral polymerase and behave as a nonobligate chain terminator. Alternatively, NHC-TP incorporation into viral RNA may result in an increased rate of mutagenesis (25, 26). Inhibitory activity in the replicon cell line indicates that NHC is not an entry inhibitor, while time-of-addition experiments suggest that NHC inhibits the early phase of CHIKV replication. Together, these data suggest that NHC-TP may play a prominent role in inhibiting early negative-strand RNA synthesis, either through chain termination or mutagenesis, which may in turn interfere with correct replicase complex formation. In conclusion, here we have described the inhibition of CHIKV replication by NHC, a novel nucleoside analog not previously implicated in alphavirus inhibition. This study sheds light on and guides the future development of antivirals against CHIKV. Moreover, NHC can be used as a positive control for drug discovery of more-potent and -selective anti-CHIKV agents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by NIH grants 5P30-AI-50409 (to R.F.S.) (Center for AIDS Research) and 1R21-AI-129607.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lo Presti A, Cella E, Angeletti S, Ciccozzi M. 2016. Molecular epidemiology, evolution and phylogeny of Chikungunya virus: an updating review. Infect Genet Evol 41:270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madariaga M, Ticona E, Resurrecion C. 2016. Chikungunya: bending over the Americas and the rest of the world. Braz J Infect Dis 20:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Duijl-Richter MK, Hoornweg TE, Rodenhuis-Zybert IA, Smit JM. 2015. Early events in Chikungunya virus infection—from virus cell binding to membrane fusion. Viruses 7:3647–3674. doi: 10.3390/v7072792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Couderc T, Lecuit M. 2015. Chikungunya virus pathogenesis: from bedside to bench. Antiviral Res 121:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdelnabi R, Neyts J, Delang L. 2015. Towards antivirals against chikungunya virus. Antiviral Res 121:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salazar-Gonzalez JA, Angulo C, Rosales-Mendoza S. 2015. Chikungunya virus vaccines: current strategies and prospects for developing plant-made vaccines. Vaccine 33:3650–3658. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McSweegan E, Weaver SC, Lecuit M, Frieman M, Morrison TE, Hrynkow S. 2015. The Global Virus Network: challenging chikungunya. Antiviral Res 120:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thiboutot MM, Kannan S, Kawalekar OU, Shedlock DJ, Khan AS, Sarangan G, Srikanth P, Weiner DB, Muthumani K. 2010. Chikungunya: a potentially emerging epidemic? PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4:e623. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henss L, Beck S, Weidner T, Biedenkopf N, Sliva K, Weber C, Becker S, Schnierle BS. 2016. Suramin is a potent inhibitor of Chikungunya and Ebola virus cell entry. Virol J 13:149. doi: 10.1186/s12985-016-0607-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karlas A, Berre S, Couderc T, Varjak M, Braun P, Meyer M, Gangneux N, Karo-Astover L, Weege F, Raftery M, Schonrich G, Klemm U, Wurzlbauer A, Bracher F, Merits A, Meyer TF, Lecuit M. 2016. A human genome-wide loss-of-function screen identifies effective chikungunya antiviral drugs. Nat Commun 7:11320. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albulescu IC, van Hoolwerff M, Wolters LA, Bottaro E, Nastruzzi C, Yang SC, Tsay SC, Hwu JR, Snijder EJ, van Hemert MJ. 2015. Suramin inhibits chikungunya virus replication through multiple mechanisms. Antiviral Res 121:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delang L, Segura Guerrero N, Tas A, Querat G, Pastorino B, Froeyen M, Dallmeier K, Jochmans D, Herdewijn P, Bello F, Snijder EJ, de Lamballerie X, Martina B, Neyts J, van Hemert MJ, Leyssen P. 2014. Mutations in the chikungunya virus non-structural proteins cause resistance to favipiravir (T-705), a broad-spectrum antiviral. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:2770–2784. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bourjot M, Leyssen P, Neyts J, Dumontet V, Litaudon M. 2014. Trigocherrierin A, a potent inhibitor of chikungunya virus replication. Molecules 19:3617–3627. doi: 10.3390/molecules19033617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das PK PL, Varghese FS, Utt A, Ahola T, Kananovich DG, Lopp M, Merits A, Karelson M. 2016. Design and validation of novel chikungunya virus protease inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:7382–7395. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01421-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ravichandran R, Manian M. 2008. Ribavirin therapy for Chikungunya arthritis. J Infect Dev Ctries 2:140–142. doi: 10.3855/T2.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernandez-Santiago BI, Beltran T, Stuyver L, Chu CK, Schinazi RF. 2004. Metabolism of the anti-hepatitis C virus nucleoside beta-d-N4-hydroxycytidine in different liver cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:4636–4642. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.12.4636-4642.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pohjala L, Utt A, Varjak M, Lulla A, Merits A, Ahola T, Tammela P. 2011. Inhibitors of alphavirus entry and replication identified with a stable Chikungunya replicon cell line and virus-based assays. PLoS One 6:e28923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lani R, Hassandarvish P, Chiam CW, Moghaddam E, Chu JJ, Rausalu K, Merits A, Higgs S, Vanlandingham D, Abu Bakar S, Zandi K. 2015. Antiviral activity of silymarin against chikungunya virus. Sci Rep 5:11421. doi: 10.1038/srep11421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiam CW, Chan YF, Loong SK, Yong SS, Hooi PS, Sam IC. 2013. Real-time polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis and quantitation of negative strand of chikungunya virus. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 77:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ehteshami M, Tao S, Ozturk T, Zhou L, Cho JH, Zhang H, Amiralaei S, Shelton JR, Lu X, Khalil A, Domaoal RA, Stanton RA, Suesserman JE, Lin B, Lee SS, Amblard F, Whitaker T, Coats SJ, Schinazi RF. 2016. Biochemical characterization of the active anti-hepatitis C virus metabolites of 2,6-diaminopurine ribonucleoside prodrug compared to sofosbuvir and BMS-986094. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:4659–4669. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00318-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han Z, Wyche JH. 1994. Guanosine induces necrosis of cultured aortic endothelial cells. Am J Pathol 145:423–427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu LF, Li GP, Feng JL, Pu ZJ. 2006. Molecular mechanisms of adenosine-induced apoptosis in human HepG2 cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin 27:477–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varghese FS, Rausalu K, Hakanen M, Saul S, Kummerer BM, Susi P, Merits A, Ahola T. 19 December 2016. Obatoclax inhibits alphavirus membrane fusion by neutralizing the acidic environment of endocytic compartments. Antimicrob Agents Chemother doi: 10.1128/AAC.02227-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmadi A, Hassandarvish P, Lani R, Yadollahi P, Jokar A, Bakar SA, Zandi K. 2016. Inhibition of chikungunya virus replication by hesperetin and naringenin. RSC Adv 6:69421–69430. doi: 10.1039/C6RA16640G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sledziewska-Gojska E, Janion C. 1983. Do DNA repair systems affect N4-hydroxycytidine-induced mutagenesis? Acta Biochim Pol 30:149–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stuyver LJ, Whitaker T, McBrayer TR, Hernandez-Santiago BI, Lostia S, Tharnish PM, Ramesh M, Chu CK, Jordan R, Shi J, Rachakonda S, Watanabe KA, Otto MJ, Schinazi RF. 2003. Ribonucleoside analogue that blocks replication of bovine viral diarrhea and hepatitis C viruses in culture. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:244–254. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.244-254.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]