Abstract

HIV-positive young Black MSM (YBMSM) experience poor antiretroviral (ART) medication adherence relative to their white counterparts. However, few studies have longitudinally examined factors that may correlate with various classifications of ART adherence among this population, which was the primary aim of this study. Project nGage was a randomized controlled trial conducted across five Chicago clinics from 2012–2015. Survey and medical records data were collected at baseline, 3-, and 12-month periods to assess psychological distress, HIV stigma, substance use, family acceptance, social support and self efficacy predicted ART medication adherence among 92 YBMSM ages 16 to 29 years old. Major results controlling for the potential effects of age, education level, employment, and intervention condition, indicated that participants with high versus low medication adherence were less likely to report daily/weekly alcohol or marijuana use, have higher family acceptance, and greater self efficacy. These findings identity important constructs that can be targeted in clinical and program interventions which correlate with improved ART medication adherence for YBMSM.

Keywords: medication adherence, men who have sex with men, African American, social support, psychological distress, family acceptance, HIV stigma, self efficacy

Young Black men who have sex with men (YBMSM) account for more than half of all new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections among youth ages 13 to 241 and have rates of HIV three and five times higher than their Latino and White counterparts, respectively.2 Such disparities necessitate effective interventions to improve prevention and treatment of HIV among YBMSM. HIV antiretroviral therapy (ART) is an essential component of HIV prevention3,4 and treatment5,6 and the single most important factor in achieving undetectable viral loads in people living with HIV.7 In addition to viral suppression, ART adherence is also correlated with reductions in hospitalizations8 and mortality,6,9,10 slowed HIV disease progression,5,11,12 and improved quality of life.13 There are also important public health implications. ART adherence and subsequent viral suppression decreases the likelihood HIV-infected will transmit the virus even when HIV-infected individuals engage in condomless anal intercourse14 and poor ART adherence has been linked to the emergence of drug-resistant strains of HIV.15

However, efficacy of ART necessitates optimal ART adherence, and previous research has revealed that many individuals with HIV do not achieve optimal adherence levels.16–18 Youth are particularly vulnerable to poor adherence; prior research indicates that adherence rates range from 30–70% among youth in the United States.19 Furthermore, there are significant racial disparities in adherence. Black Americans have lower rates of ART adherence than White Americans20–22 and are less likely to be retained in HIV medical care.23 Racial and ethnic minority youth are at particularly high risk of poor ART adherence and thus, having a detectable viral load.24,25 A comprehensive review on youth living with HIV found that between 42% and 80% of youth report suboptimal medication adherence.26

There are numerous social and contextual factors that have been linked to suboptimal ART adherence among HIV-infected youth including exposure to community violence,27 lack of social support,28 and low self-efficacy.18 There is also strong evidence that HIV-related stigma contributes to poor ART adherence29,30 by reducing self-efficacy for adherence and self-care and raising concerns about inadvertent disclosure of HIV status.29 For example, perceived-discrimination from sexual partners is associated with difficulty adhering to ART.31 Furthermore, discrimination based on HIV serostatus, race, and sexual orientation are associated with poor treatment adherence over a 6-month period among Black men living with HIV.29,32 Additionally, mental health, including depression and anxiety,19 and substance use have also been found to be consistently associated with poor ART adherence among youth.17,33

Study contributions

The above research documenting that to community violence, social support, and other psychosocial factors are associated with HIV mediation is informative; however, several gaps remain. There might be important classifications of medication adherence (i.e., low medium and high) that are based on various clusters of these important socio contextual factors. However, few studies have utilized a person-oriented approach to understating such classifications. As it relates to this study, latent class analyses (LCA) allows us to identify and examine lawful regularities and organized configurations of interactive factors that distinguish qualitatively different groups of individuals based on medication adherence.34,35 Therefore, the purpose of this study is to extend existing research by examining longitudinal predictors of ART adherence among HIV positive YBMSM. The findings from this study can help illuminate important factors that correlate with ART adherence overtime to inform the development of interventions tailored to improve adherence among HIV-infected YBMSM.

Methods

Data was collected, across three waves, between October 2012 and November 2014 as part of the baseline assessment from Project nGage, a preliminary efficacy randomized control, examining the role of social support in improving HIV-care among YBMSM. HIV-infected YBMSM ages 16–29 who had successfully linked to care were randomized to the intervention or a control arm consisting of treatment as usual, including standard case management. The intervention included the engagement of a youth-identified support confidant to help endorse adherence to HIV primary care. Two face-to-face meetings with a social work interventionist, as well as 11 brief booster sessions delivered remotely via telephone and text messaging. Study design and intervention details are described in more depth elsewhere [Blinded]. Participants were recruited at two study sites; a university hospital and a federally qualified health center. Eligibility included being born biologically male, self-identifying as Black or African American, between the ages of 16 and 29, inclusive, having an HIV diagnosis for greater than three months, and having disclosed their status to at least one person in their close social network. Two transgender women were included in the sample but excluded from these analyses given their limited sample. Participants were screened, scheduled, consented, and enrolled by the study research staff (i.e., research assistants and associates). Baseline measures were collected using computer-assisted administration, (both interviewer and self-administration), survey questions were read aloud and responses were recorded in REDCap. Whenever possible, measures were selected that had been previously tested in studies of ART adherence, particularly among youth, to maximize comparability to other studies. Participants received $25 for completing the baseline and each follow-up survey. All study protocol and procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Demographic variables

Participants reported their age, highest level of education or schooling, current employment status and intervention condition.

Medication adherence

Adherence levels of 90–95% are crucial to the success of antiretroviral therapy. To assess medication adherence for each wave of the study period, participants were asked whether they were currently taking HIV medications. Response categories were “Not prescribed yet, meds prescribed but haven’t picked up yet; meds prescribed but don’t want to take them, meds prescribed, but haven’t been into the clinic; and other.” Those who reported being on HIV medications were asked: “What percent, from 0 to 100, did you take your medication as prescribed in the last 30 days? Zero percent time would mean ‘none of the time’, ‘50% time indicated ‘half of the time’, and ‘100%’ indicated all of the time.’ In this study, adherence was dichotomized as those taking their medication between 90–100% of the time and those taking their medication less than 90% of the time.

Psychological distress

Psychological distress at baseline was measured using the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18) scale, which assesses the Global Severity Index (GSI), a cumulative measure of psychological distress36. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “not at all” to 5 “extremely”. The raw GSI score was computed taking the mean of all item scores. Raw scores were converted to T-scores and a participant was considered to experience psychological distress if T > 62. The psychological distress variable was transformed into a dichotomous variable with a T-score of 62 as the cutoff point37.

HIV Stigma

Stigma at baseline was measured using the abbreviated HIV stigma scale, which has been validated among HIV infected youth38. In the current study, HIV stigma consists of two domains: personalized stigma measuring the consequences of other people knowing one’s status and negative self-image including feelings of shame, guilt, and not being as good as others39. The total stigma scale contained 6 items and each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” A composite score was calculated, with higher scores indicating high levels of stigma. The Cronbach’s alpha was .717.

Substance use

Alcohol and marijuana use history were assessed at baseline. Participants were asked whether they had used daily or weekly alcohol or marijuana in last three months. Response options were no/yes.

Family acceptance

Family acceptance was measured at baseline using 4 items including, “I feel part of my family” and “My family really cares about me.” Items were assessed on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 4 “strongly agree”. A composite score was calculated by summing the responses for the 4 items, with higher scores indicating high levels of family acceptance. The Cronbach’s alpha was .857.

Social support

Social support at baseline was assessed using 4 items that inquired about the degree to which their friends or family support them taking their HIV medication (e.g., “To what extent do your friends help you remember to take your HIV medication?”, “To what extent do your family help you remember to take your HIV medication?”). Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “not at all” to 5 “extremely”. High and low social support were based on the median score split of 10.0 (range 4–18). The Cronbach’s alpha was .546.

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy at baseline was assessed using a measure from Outlaw et al. (2010), which contains 3 items that inquired about the self-efficacy of one’s health (e.g., “How sure are you that you can take care of your health?”).14 Responses were recorded using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “very sure I cannot” to 5 “very sure I can”. The composite score was dichotomized based on the median split of 14.0 (range 7–15). The Cronbach’s alpha was .609.

Analyses

Univariate analyses were conducted to describe the overall sample. Next, LCA was employed to determine the number and nature of subtypes of medicine adherence based on three waves. The class structure was confirmed through adding models iteratively until the model fit the data well from both a statistical and an interpretive perspective. For the Statistical criteria, the Lo-Mendell-Ronbin (LMR) adjusted likelihood ratio test was used to evaluate the extent to which the specified model fit better than a model with one less class.40 Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and Sample-Size Adjusted Bayesian Information (SSABIC) values were examined to determine goodness-of-fit (lower values indicating improved fit). Entropy values were used as measures of classification accuracy (higher values for each group indicating better classification and stronger separation). We also considered conceptual interpretation of the resultant classes when determining the best model.41 Finally, individual logistic regression analyses were conducted on the classes to ascertain differences between classes. All regressions controlled for age, education level, employment, and intervention condition. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are reported. Missing data was handled in Mplus Version 6.1 using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation.41 FIML can be more precise than traditional methods such as listwise deletion, pairwise deletion, and mean imputation. Its parameter estimates have less bias than these other three methods.42

Results

Descriptive characteristic of the sample

The sample included 92 YBMSM. As indicated in Table I, participants ranged in age from 18 to 29 with an average age of 23.8 (SD=2.85). Nearly 80% of participants had a high school diploma or greater and just over half were working either full- or part-time. Regarding the intervention condition, 44 (47.8%) participants were involved with the intervention group and 48(52.2%) were the control group. Psychological distress (Cronbach’s Alpha=.893) was evident among 12 (10.8%) participants and the mean score on the HIV stigma scale was 11.35 (SD=3.60). Approximately, 67% of participants used alcohol daily or weekly in the last 3 months and 61% of participants used marijuana daily or weekly in the last 3 months. The mean for family acceptance was 13.5 (range 6–16, SD = 2.82), social support was 10.3 (range 4–18, SD = 3.06) and self-efficacy was 13.3 (range 7–15, SD = 1.91). Among the 82 participants taking antiretorivirals, 55 (67.1 %) reported taking their medication at least 90% of the time in the past 30 days for the baseline, 54(61.4%) for the second wave and 53(66.3%) for the third wave.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the overall sample (N=92)

| Variable | N (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (range 18–29) | 23.9(2.90) | |

| Education | ||

| HS diploma or GED | 30(32.6%) | |

| Greater than HS | 53(57.6%) | |

| Less than HS | 9(9.8%) | |

| Employment | ||

| Full-time | 30(32.6%) | |

| Part-time | 22(23.9%) | |

| Unemployed | 40(43.5%) | |

| Psychological distress | 12(13.0%) | |

| Alcohol use | 62(67.4%) | |

| Marihuana use | 56(60.9%) | |

| Family acceptance (range 6–16) | 13.51(2.82) | |

| Social support (range 4–18) | 10.29(3.06) | |

| Self-efficacy (range 7–15) | 13.47(1.91) | |

| Personalized Stigma (range 3–12) | 5.67(2.31) |

Identification of the latent classes

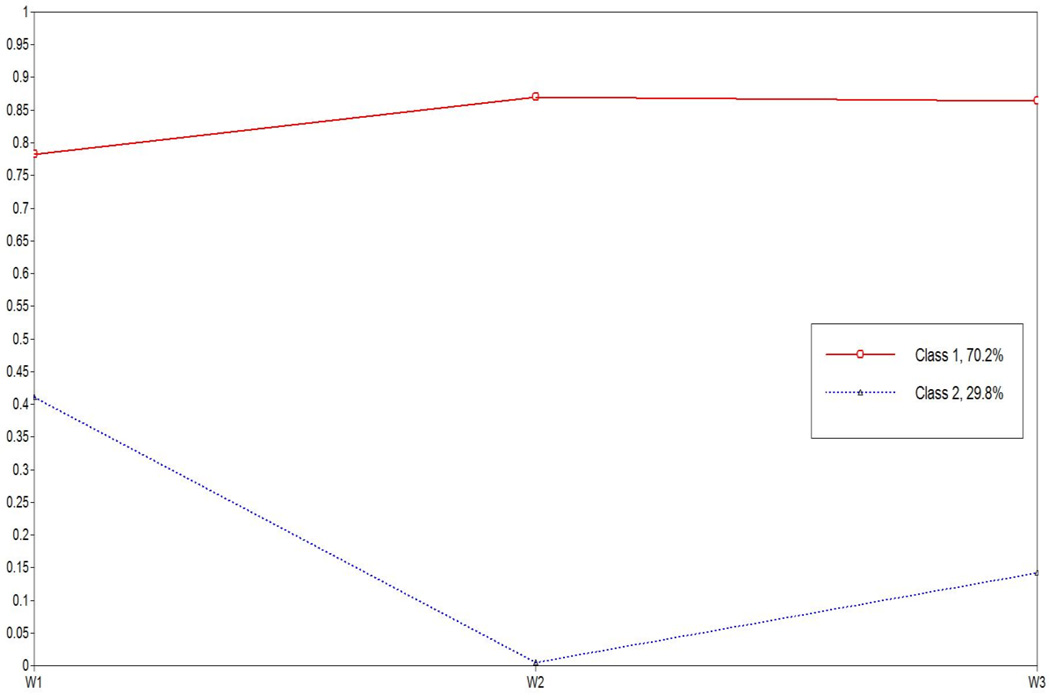

Based on the model fit indexes, the two-class solution was considered the best model due to the lowest AIC, BIC and SSABIC values, higher Entropy value, and significant LMRT value (see Table 2). The conceptual fit of the models was also examined through visual inspection, which involved plotting the estimated mean values for each wave of medicine adherence by each class. In the two-class model, classes were clearly distinguishable, ranging from low to high (see Figure 1). Consequently, the two-class model was retained due to class assignments and appeared to be highly reliable. As presented in Figure 1, Class 1 (70.2%, N = 62) was characterized as having high levels of medication adherence for all three waves and Class 2 (29.8%, N = 30) was characterized by having low levels of medication adherence for all three waves.

Table 2.

Summary of Information for Selecting Number of Latent Classes

| Num ber of latent class |

Likelih ood Ratio χ2 |

d.f | AIC | BIC | Adjust ed BIC |

LNR_L RT (p - Value) |

Entr opy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | − 161.81 3 |

3 | 329.6 27 |

337.1 92 |

327.7 22 |

<.0001 | |

| 2 | −145.43 2 |

7 |

304.8 64 |

322.5 16 |

300.4 20 |

.000 | .779 |

| 3 | −145.43 2 |

11 | 312.8 64 |

340.6 03 |

305.8 81 |

0.50 | .694 |

| 4 | −145.43 2 |

15 | 320.8 64 |

358.6 91 |

311.3 42 |

.393 | .547 |

Figure1.

Response probabilities for the three waves in a two class model of the medication adherence

Comparison of the classes

To better understand the two subtypes of medication adherence across time, separate logistic regression analyses were conducted to explore associations with specified correlates. Table 3 displays the significance of the correlates on the high medication adherence classes compared to the low medication adherence.

Table 3.

Predictors of high medication adherence during three waves

| Variables | Class1(n=62) High medication adherence |

|

|---|---|---|

| B(SE) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

| Daily/ weekly use alcohol | −1.895(.711) | .150(.037–.606)** |

| Daily/ weekly use Marihuana | −1.450(.646) | .235(.066–.832)* |

| Family acceptance | .172(.085) | 1.188(1.006–1.403)* |

| Social support | .020(.077) | 1.020(.878–1.186) |

| Physiological distress | −.040(.686) | .961(.251–3.685) |

| Self-efficacy | 1.285(.498) | 3.614(1.363–9.583)* |

| Personalized Stigma | −.276(.496) | .759(.287–2.006) |

p < .10;

p< .05;

p < .01;

p< .001

Reference group is Class2 (n=30) (low medication adherence)

Controlled for age, education level, study group, and employment

Controlling for the effects of age, education level, employment, and intervention condition, we found that compared to participants with low medication adherence across three waves, participants with high medication adherence across three waves were less likely to have daily/weekly alcohol use (OR: .150, 95%CI: .037–.606) and marijuana use (OR: .235, 95%CI: .066–.832) in the past three months. In addition, participants with high medication adherence across three waves were almost 1.2 times higher in family-acceptance (OR: 1.19, 95%CI: 1.006–1.403) and 3.6 times higher in self-efficacy (OR: 3.614, 95%CI: 1.363–9.583) compared to the participants with low medication adherence across three waves. HIV stigma, social support, and psychological distress were not significantly related with subtypes of medication adherence across three waves in the current study.

Discussion

This study is among the first to examine longitudinal predictors of ART adherence among HIV-positive YBMSM. Across all three waves of the study, participants taking ART reported optimal adherence (>90%) approximately 65% of the time, consistent with previous research.16,43 This research uncovered several factors associated with adherence among YBMSM. Our findings indicate that higher levels of alcohol and marijuana use were predictive of suboptimal ART adherence: participants with higher levels of medication adherence were less likely to report daily or weekly alcohol use and marijuana use in the previous 3 months. These findings are not surprising, as drug us is commonly used as a copy strategy for dealing with an HIV diagnosis44 and can impede engagement in HIV care.45 In previous research with HIV-infected YBMSM, researchers demonstrated a relationship between anxiety and alcohol and marijuana use, which contributed to poor medication adherence.46 Substance use is a barrier to ART initiation and engagement in care, can reduce confidence in one’s medication management skills, and contribute to depression.45

In line with previous research,16 our study also revealed that self-efficacy can contribute to higher levels of ART adherence. Self-efficacy with regard to HIV treatment is operationalized as an individual’s perceived ability to adhere to ART and engage in HIV treatment given various social and environmental factors.47 Adherence is often dependent on youths’ confidence in their ability to take ART as prescribed. Youth with higher levels of medication adherence had significantly higher self-efficacy than evident among those with suboptimal ART adherence. These findings are significant, as self-efficacy to take ART medication as prescribed is one of the strongest predictors of ART adherence among racial and ethnic minorities.48

Research by MacDonell et al. (2016) suggests that youth with higher levels of social support are more likely to have higher self-efficacy and therefore greater motivational readiness to adhere to ART. Surprisingly, social support was not associated with optimal ART adherence. In this study, social support focused on the extent to which friends and family helped youth remember to take their medications and did not examine other types of support (e.g. instrumental vs. emotional), which may be an important factor. Additionally, the composition of one’s social support network (e.g. friends, sexual partners, family members, mentors), may influence how important social support is to medication adherence.49 Although social support was not associated with optimal ART adherence, family acceptance was positively associated with adherence. Although previous research has documented the rejection and homonegativity YBMSM can experience from their families,50 increasing acceptance and support of families may play an important role in ART adherence among YBMSM. Future research should continue to differentiate sources of support (e.g. family, peers) and types of support in order to understand the role of families in HIV outcomes for YBMSM.

Despite the important contributions of this study, there are limitations to note. This is a small convenience sample of HIV-infected YBMSM in a single urban city. As such, findings from this study may not be generalizable to other youth. Additionally, medication adherence levels were self-reported and participants may have over-or under-reported adherence levels. However, there is evidence of a link between self-reported ART adherence and clinical viral load, suggesting self-report measures may be a reliable tool to understand adolescent ART adherence.16

Overall, our findings shed light on several factors that may influence longitudinal medication adherence among HIV-infected YBMSM and offer several opportunities for intervention. First, culturally-tailored interventions that strengthen family acceptance and support may be a useful strategy to enhance ART adherence among YBMSM. Research should continue to explore which sources and types of support are most beneficial to youth and find opportunities to enhance that support. Strategies are also needed to increase self-efficacy among HIV-infected YBMSM. For example, motivational interviewing techniques have been successful at improving self-efficacy and ART adherence and have demonstrated effectiveness among racial and ethnic minority youth.51 Finally, our findings highlight the need to incorporate substance use treatment into programs for HIV-infected youth. Substance use is strongly associated with poor engagement along the HIV care continuum45 and it is clear that it negatively influences ART adherence for YBMSM. Research should continue to explore effective interventions to improve initiation and adherence with ART, especially among YBMSM.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health [R34MH097622, R01DA039934 and R01DA033875]. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01726712. This manuscript was also made possible with help from the Third Coast Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI 117943).

We would like to thank the study participants for their participation and Alida Bouris, Milton “Mickey” Eder, Molly Pilloton, Natasha Flatt, Tiffany Washington, Keisha Hampton and Montre Washington for their valuable contributions to the project.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence in the united states, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012;17(4) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Millett G, Flores F, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: A meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS. 2007;21:2083–2091. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(151):151ra125. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Bumpus NN, et al. HIV protective efficacy and correlates of tenofovir blood concentrations in a clinical trial of PrEP for HIV prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(3):340–348. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benator DA, Elmi A, Rodriguez MD, et al. True durability: HIV virologic suppression in an urban clinic and implications for timing of intensive adherence efforts and viral load monitoring. AIDS and Behavior. 2015;19(4):594–600. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0917-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lima VD, Harrigan R, Bangsberg DR, et al. The combined effect of modern highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens and adherence on mortality over time. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50(5):529–536. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819675e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flynn PM, Rudy BJ, Douglas SD, et al. Virologic and immunologic outcomes after 24 weeks in HIV type 1-infected adolescents receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(2):271–279. doi: 10.1086/421521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(1):21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hogg RS, Heath K, Bangsberg D, et al. Intermittent use of triple-combination therapy is predictive of mortality at baseline and after 1 year of follow-up. AIDS. 2002;16(7):1051–1058. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200205030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wood E, Hogg RS, Yip B, Harrigan PR, O'Shaughnessy MV, Montaner JS. Effect of medication adherence on survival of HIV-infected adults who start highly active antiretroviral therapy when the CD4 cell count is 0.200 to 0.350× 109 cells/L. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(10):810–816. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bangsberg DR, Perry S, Charlebois ED, et al. Non-adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy predicts progression to AIDS. AIDS. 2001;15(9):1181–1183. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200106150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eaton EF, Saag MS, Mugavero M. Engagement in human immunodeficiency virus care: Linkage, retention, and antiretroviral therapy adherence. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2014;28(3):355–369. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burman WJ, Grund B, Roediger MP, et al. The impact of episodic CD4 cell count-guided antiretroviral therapy on quality of life. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(2):185–193. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815acaa4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Outlaw AY, Naar-King S, Parsons JT, Green-Jones M, Janisse H, Secord E. Using motivational interviewing in HIV field outreach with young african american men who have sex with men: A randomized clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S146–S151. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.166991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang JW, Pillay D. Transmission of HIV-1 drug resistance. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2004;30(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolmodin MacDonell K, J Jacques-Tiura A, Naar S, Isabella Fernandez M. ATN 086/106 Protocol Team. Predictors of self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medication in a multisite study of ethnic and racial minority HIV-positive youth. J Pediatr Psychol. 2016;41(4):419–428. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao D, Kekwaletswe TC, Hosek S, Martinez J, Rodriguez F. Stigma and social barriers to medication adherence with urban youth living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2007;19(1):28–33. doi: 10.1080/09540120600652303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naar-King S, Templin T, Wright K, Frey M, Parsons JT, Lam P. Psychosocial factors and medication adherence in HIV-positive youth. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2006;20(1):44–47. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Skeer M, Perkovich B, Johnson CV, Safren SA. A review of HIV antiretroviral adherence and intervention studies among HIV-infected youth. Top HIV Med. 2009;17(1):14–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lazo M, Gange SJ, Wilson TE, et al. Patterns and predictors of changes in adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: Longitudinal study of men and women. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(10):1377–1385. doi: 10.1086/522762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sullivan PS, Campsmith ML, Nakamura GV, Begley EB, Schulden J, Nakashima AK. Patient and regimen characteristics associated with self-reported nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy. PLoS One. 2007;2(6):e552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh DL, Sarafian F, Silvestre A, et al. Evaluation of adherence and factors affecting adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy among white, hispanic, and black men in the MACS cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(2):290–293. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ab6d48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giordano TP, Hartman C, Gifford AL, Backus LI, Morgan RO. Predictors of retention in HIV care among a national cohort of US veterans. HIV clinical trials. 2015 doi: 10.1310/hct1005-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacDonell K, Naar-King S, Huszti H, Belzer M. Barriers to medication adherence in behaviorally and perinatally infected youth living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(1):86–93. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0364-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simoni JM, Huh D, Wilson IB, et al. Racial/Ethnic disparities in ART adherence in the united states: Findings from the MACH14 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(5):466–472. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825db0bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simoni JM, Montgomery A, Martin E, New M, Demas PA, Rana S. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for pediatric HIV infection: A qualitative systematic review with recommendations for research and clinical management. Pediatrics. 2007;119(6):e1371–e1383. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quinn K, Voisin DR, Bouris A, Schneider J. Psychological distress, drug, use, sexual risks and medication adherence among young HIV-positive black men who have sex with men: Exposure to community violence matters. AIDS Care. 2016:1–7. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1153596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacDonell KE, Naar-King S, Murphy DA, Parsons JT, Huszti H. Situational temptation for HIV medication adherence in high-risk youth. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(1):47–52. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sweeney SM, Vanable PA. The association of HIV-related stigma to HIV medication adherence: A systematic review and synthesis of the literature. AIDS and Behavior. 2016;20(1):29–50. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quinn K, Voisin DR, Bouris A, et al. Multiple dimensions of stigma and health related factors among young black men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2016:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1439-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC, Littlewood RA. Impact of HIV-related stigma on health behaviors and psychological adjustment among HIV-positive men and women. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(5):473–482. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9099-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Galvan FH, Klein DJ. Longitudinal relationships between antiretroviral treatment adherence and discrimination due to HIV-serostatus, race, and sexual orientation among African–American men with HIV. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;40(2):184–190. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9200-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hosek SG, Harper GW, Domanico R. Predictors of medication adherence among HIV-infected youth. Psychol, Health Med. 2005;10(2):166–179. doi: 10.1080/1354350042000326584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergman LR, Magnusson D, El Khouri BM. Studying individual development in an interindividual context: A person-oriented approach. Psychology Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCutcheon AL. Latent class analysis. Sage: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Derogatis LR. Brief symptom inventory 18. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Voisin D, Walsh T, Flatt N, et al. HIV medication adherence, substance use, sexual risk behaviors and psychological distress among younger black men who have sex with men and transgender women: Preliminary findings. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice. 2014;4(12):p27. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright K, Naar-King S, Lam P, Templin T, Frey M. Stigma scale revised: Reliability and validity of a brief measure of stigma for HIV youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40(1):96–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(6):518–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lo Y, Mendell NR, Rubin DB. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88(3):767–778. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muthén B. Statistical and substantive checking in growth mixture modeling: Comment on bauer and curran (2003) 2003 doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Enders CK. The impact of nonnormality on full information maximum-likelihood estimation for structural equation models with missing data. Psychol Methods. 2001;6(4):352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rudy BJ, Murphy DA, Harris DR, Muenz L, Ellen J. Patient-related risks for nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected youth in the united states: A study of prevalence and interactions. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(3):185–194. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sprague C, Simon SE. Understanding HIV care delays in the US south and the role of the social-level in HIV care engagement/retention: A qualitative study. International journal for equity in health. 2014;13(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-13-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gwadz M, de Guzman R, Freeman R, et al. Exploring how substance use impedes engagement along the hiV care continuum: A qualitative study. Frontiers in public health. 2016;4 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuhns LM, Hotton AL, Garofalo R, et al. An index of multiple psychosocial, syndemic conditions is associated with antiretroviral medication adherence among HIV-positive youth. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30(4):185–192. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bandura A. The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of social and clinical psychology. 1986;4(3):359–373. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Houston E, Fominaya AW. Antiretroviral therapy adherence in a sample of men with low socioeconomic status: The role of task-specific treatment self-efficacy. Psychol, Health Med. 2015;20(8):896–905. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2014.986137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schneider J, Michaels S, Bouris A. Family network proportion and HIV risk among black men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(5):627–635. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318270d3cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quinn K, Dickson-Gomez J. Homonegativity, religiosity, and the intersecting identities of young black men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2016;22(1):51–64. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1200-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naar-King S, Outlaw AY, Sarr M, et al. Motivational enhancement system for adherence (MESA): Pilot randomized trial of a brief computer-delivered prevention intervention for youth initiating antiretroviral treatment. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38(6):638–648. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]