Abstract

Peroxisomes carry out many key functions related to lipid and reactive oxygen species (ROS) metabolism. The fundamental importance of peroxisomes for health in humans is underscored by the existence of devastating genetic disorders caused by impaired peroxisomal function or lack of peroxisomes. Emerging studies suggest that peroxisomal function may also be altered with aging and contribute to the pathogenesis of a variety of diseases, including diabetes and its related complications, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancer. With increasing evidence connecting peroxisomal dysfunction to the pathogenesis of these acquired diseases, the possibility of targeting peroxisomal function in disease prevention or treatment becomes intriguing. Here, we review recent developments in understanding the pathophysiological implications of peroxisomal dysfunctions outside the context of inherited peroxisomal disorders.

Keywords: aging, neurodegeneration, peroxisome, pexophagy, reactive oxygen species

Peroxisome: the Little Organelle that Could

Peroxisomes are ubiquitous and highly versatile cellular organelles. Although they were originally named based on their role in hydrogen peroxide production and catabolism, the functions of peroxisomes extend far beyond ROS (see Glossary) metabolism. Compartmentalized in these small organelles are >50 different enzymes, constituting several distinct pathways that regulate various aspects of cellular metabolism, including fatty acid (FA) oxidation and lipid synthesis. The size and appearance of peroxisomes often varies among different types of tissues, ranging from 0.1 to 1 μm in diameter. As highly dynamic organelles, peroxisomes can modify their size, morphology, abundance, and function, depending on external stimuli or developmental stage [1,2].

As an organelle, peroxisomes are often neglected, perhaps due to the misconception that they play only ancillary or redundant roles. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that peroxisomes are essential organelles whose functions cannot be replaced by other organelles. Much of our understanding of the critical importance of peroxisomes for health in humans is based on the existence of devastating genetic disorders caused by impaired function or biogenesis of this organelle. Most of these disorders cause severe neurological dysfunctions, a host of other abnormalities, and death in early childhood [3,4]. What is underappreciated is the notion that peroxisomal function may also be altered with aging, contributing to disease. Recent studies support a peroxisomal role in the pathogenesis of aging-related diseases, including diabetes, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancer [5], although it is still uncertain whether these pathologies may be a cause or consequence of peroxisomal dysfunction.

Here, we briefly discuss major metabolic functions of peroxisomes and then highlight recent studies suggesting that peroxisomal function is altered with aging, emphasizing the processes involved in peroxisomal dysfunction, and the contribution to disease development.

Major Metabolic Functions of Peroxisomes

In addition to regulating ROS metabolism, peroxisomes are responsible for a variety of lipid metabolic functions, including beta oxidation of very long chain fatty acids (VLCFAs), alpha oxidation of branched-chain FAs, and synthesis of ether lipids and bile acids [2], as illustrated in Figure 1. Although peroxisomal functions can be broadly classified into two major categories, lipid metabolism and ROS metabolism; both are interconnected. These metabolic functions require cooperation of peroxisomes with other organelles including mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), lipid droplets, and lysosomes.

Figure 1. Metabolic Functions of Peroxisomes.

Peroxisomes perform a variety of lipid metabolic functions. Catabolic functions include beta oxidation of VLCFAs and alpha oxidation of 3-methyl branched FAs, whereas anabolic functions include ether lipid synthesis and bile acid synthesis. Peroxisomes are also involved in the metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Abbreviations: DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; FA, fatty acid; G3P, glycerol 3-phosphate; ROS, reactive oxygen species; VLCFA, very long chain fatty acid.

Lipid Metabolism

Peroxisomes in all eukaryotic organisms have the ability to oxidize FAs. Oxidation of FAs requires activation of FAs to a fatty acyl-CoA. Fatty acyl-CoA transport across the peroxisomal membrane occurs through peroxisomal ATP binding cassette (ABC) subfamily D half transporters, that form heterodimers [6]. Beta oxidation of the fatty acyl-CoA molecule results in the removal of two carbons from its carboxyl terminus. Peroxisomal beta oxidation differs from mitochondrial beta oxidation in several key aspects, as described in Table 1. While the mechanisms of peroxisomal and mitochondrial beta oxidation are similar, the enzymes involved are unique to each organelle. The first step of mitochondrial beta oxidation produces FADH2, which is used to generate ATP via the electron transport chain. The first step of beta oxidation in peroxisomes, by contrast, is not coupled to energy production, but instead to the reduction of O2 to the ROS (H2O2 [7]. The FA specificities of each organelle differ as well. Mitochondria preferentially oxidize short-chain (<C6) and medium-chain (C6–C12) FAs, while both mitochondria and peroxisomes oxidize long-chain (C12–C20) FAs. Mitochondria are thought to have a quantitatively greater contribution to oxidation of long chain FAs, but the relative contribution of peroxisomes to this process can vary depending on physiological context [8]. Beta oxidation of VLCFAs (>C20) and dicarboxylic acids occurs exclusively in peroxisomes [9,10]. Peroxisomal beta oxidation is a chain-shortening process and is not carried to completion. Peroxisomes exhibit carnitine acyltransferase activity, reflecting the need to shuttle the breakdown products into mitochondria for further oxidation [11].

Table 1.

Comparison between Mitochondrial and Peroxisomal FA oxidation

| Parameter | Mitochondrial pathway | Peroxisomal pathway | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate specificity | Short (<C6), medium (C6–C12), and long (C12–C20) chain fatty acids | Long and very long (C>20) chain fatty acids, dicarboxylic acids | [9,10] |

| Transport mechanism | Diffusion (short and medium chain), carnitine shuttle (long chain) | ABCD subfamily half-transporters | [6] |

| Enzymes |

|

|

[7] |

| Side products | ATP | H2O2, heat | [7] |

| Products | Acetyl-CoA | Shortened chain fatty acyl-CoAs, acetyl-CoA | [7] |

Mitochondrial trifunctional protein that catalyzes Steps 2–4 of long chain FA oxidation. Mitochondria also possess separate individual enzymes that catalyze these steps for chain-shortened FAs.

Peroxisomal multifunctional enzymes (Types 1 and 2) that possess the two indicated activities.

MFE,; MTP,.

While beta oxidation is the preferential mode of FA oxidation for a variety of substrates, long chain 2-hydroxy FAs and 3-methyl branched FAs, such as phytanic acid, cannot be oxidized through beta oxidation directly, and must first undergo alpha oxidation, which occurs exclusively in peroxisomes. In alpha oxidation, FAs are first converted to their CoA ester and then α-hydroxylase adds a hydroxyl group to the α-carbon. The product is decarboxylated to form an aldehyde, which is then oxidized by an aldehyde dehydrogenase. Further catabolism proceeds through beta oxidation [12].

Peroxisomes are not only involved in catabolic reactions but also in the synthesis of a specialized class of phospholipids called ether lipids [13]. In contrast to the more common diacyl phospholipids, which have fatty acyl side chains linked to the sn-1 and sn-2 positions of the glycerol backbone by ester bonds, ether lipids have the sn-1 substituent attached by an ether bond. Plasmalogens are a subtype of ether-linked phospholipids that have a cis double bond adjacent to the ether bond. Peroxisomes are involved in the initial steps of ether lipid synthesis and completion occurs in the ER, as explained in Box 1. The gene encoding the enzyme that catalyzes the terminal peroxisomal step was recently identified, and the protein was named peroxisomal reductase activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PexRAP), based on its proposed function in adipocytes [14]. Ether lipids account for up to 20% of the total phospholipid content in humans and are particularly abundant in the brain, heart, and neutrophils [15]. Plasmalogens are important components of cellular membranes and may be involved in the organization of cholesterol-rich membrane regions known as detergent-resistant microdomains, which have been implicated in cellular signaling [16]. Besides their structural roles, plasmalogens have been associated with a wide variety of other functions including antioxidant, signaling, spermatogenetic [17], neurological [18], and immunometabolic [19] functions.

Box 1. Ether Lipid Synthesis.

The ether lipid synthetic pathway uses DHAP, produced by dehydrogenation of glycerol 3-phophate (G3P), as a building block for the synthesis of phospholipids. Acyl CoA, derived from de novo lipogenesis is used by DHAPAT to acylate DHAP. Alkyl-DHAP synthase (also called AGPS) converts acyl-DHAP to alkyl-DHAP, which is then reduced to 1-O-alkyl glycerol-3-phosphate by the peroxisomal membrane protein acyl/alkyl DHAP reductase (also called PexRAP) [2,14]. Further steps to complete ether-linked phospholipid synthesis, including acylation of the sn-2 position of the glycerol backbone and addition of the head group, occur in the ER.

Peroxisomes are also involved in bile acid synthesis [20]. In addition, several enzymes involved in the early stages of cholesterol synthesis (pre-squalene segment of the pathway) have been reported to be present in peroxisomes [21], but the overall contribution of peroxisomes to cholesterol synthesis is unclear [22]. Cholesterol is an essential lipid accounting for 30–40% of total cellular lipid store and is involved in many cellular functions, including signal transduction, bile acid synthesis, steroid synthesis, and plasma membrane composition. Peroxisomes have also been reported to be involved in transport of free cholesterol. A recent study showed that cholesterol can be transported from the lysosomes to the peroxisomes through lysosomal–peroxisomal membrane contact (LPMC), and knockdown of peroxisomal proteins leads to impaired cholesterol transport [23].

ROS Metabolism

Peroxisomes account for up to 20% of total cellular oxygen consumption [24]. Unlike mitochondrial respiration, which is linked to ATP synthesis, peroxisomal respiration produces H2O2 as the end product through the action of multiple oxidases present in the organelle. Peroxisomes can account for up to 35% of total H2O2 generation in mammalian tissues [25]. To counterbalance the damaging effect of this ROS, peroxisomes in many, but not all cell types, contain abundant amounts of the antioxidant enzyme catalase, which reduces H2O2 to water. Peroxisomes are also involved in the production of other ROS, including superoxide radicals and nitric oxide radicals, and are equipped with their associated antioxidant enzymes as well [26,27]. Oxidative stress is a major contributor to cellular senescence and pathogenesis of various age-related disorders, suggesting that the ability of peroxisomes to maintain a balance between ROS production and catabolism may be compromised with aging.

Relationship between Peroxisomal Dysfunction and Aging

The role of peroxisomal dysfunction in aging has been largely neglected, in part due to the similarities in the functions of peroxisomes and mitochondria, with much of the attention on oxidative-stress-associated aging focusing on the role of mitochondrial dysfunction [28]. Although peroxisomes play a major role in H2O2 production, it is difficult to isolate the contribution of peroxisomes in this process from that of mitochondria, and delineate the site of ROS origination within cells [29]. Nevertheless, accumulating evidence suggests that peroxisomal function declines with aging, and links oxidative stress caused by dysregulated peroxisomal ROS metabolism to disease [5,29].

Peroxisome-mediated ROS production is thought to have a profound effect on mitochondrial integrity. Induction of intraperoxisomal ROS production using a peroxisome-localized photosensitizer results in increased mitochondrial fragmentation; a manifestation of aging at the cellular level [30]. Moreover, genetic inactivation of catalase, a predominantly peroxisomal protein, perturbs mitochondrial redox potential in mice [31]. Reflecting the intimate link between the two organelles, these studies suggest that peroxisomal dysfunction may be a precursor for mitochondrial dysfunction.

Studies in cultured cells suggest that catalase is increasingly excluded from the peroxisomes as cells age with serial passaging, resulting in increased oxidative stress and cellular senescence. Surprisingly, the number of peroxisomes is increased in older cells, suggesting accumulation of the defective organelles with aging [24]. Recently, a quantitative mass-spectrometry-based study in Caenorhadbditis elegans identified ~30 peroxisomal proteins whose abundance decreased with aging [32]. One such protein identified was Pex5, an import receptor for peroxisomal matrix proteins containing a conserved C-terminal tripeptide called peroxisomal targeting sequence 1 [33,34]. Pex5 is involved in peroxisomal import of catalase [35] and has been shown to be redox sensitive [36,37]. Thus, oxidative stress could directly interfere with Pex5 import activity. Decreased abundance and/or impaired function of Pex5 could potentially explain the mechanism for aging-related mislocalization of the antioxidant enzyme. However, the C. elegans study indicated that proteins involved in peroxisomal FA oxidation, ether lipid synthesis, and other peroxisomal processes were also decreased [32], suggesting that aging-related peroxisomal dysfunction extends beyond dysregulated ROS metabolism.

Together, these studies suggest that peroxisomal function is compromised with aging. To avoid pathologies associated with the accumulation of defective peroxisomes, the ability to maintain peroxisomal homeostasis may be critical.

Clearance of Dysfunctional Peroxisomes through Autophagy

Peroxisomal homeostasis is maintained through coordinated regulation of biogenesis and degradation of the organelle in response to changing environmental conditions. Under basal conditions, peroxisomes have a half-life of ~2 days [38]. Old or dysfunctional peroxisomes are removed primarily by autophagy; a catabolic process that involves lysosomal degradation of intracellular components through formation of a double membrane autophagosome around the cargo, which then fuses with lysosomes [39,40].

In addition to the canonical autophagy pathway, which is a nonselective (bulk) degradation of cytoplasmic contents, selective autophagy exists. Selective autophagy involves adaptor proteins, such as p62 and NBR1, which recognize ubiquitinated autophagic cargo and tether it to the site of autophagosomal engulfment [41]. Selective autophagic degradation of peroxisomes is called pexophagy. The pexophagy pathway in yeast has been well characterized [42], but the molecular mechanism of the process in mammals is just now beginning to be understood. The identity of the receptor in mammals that undergoes ubiquitination and marks peroxisomes for autophagic degradation has long been a matter of debate. Recently, two groups independently demonstrated that pexophagy requires ubiquitination of Pex5 [43,44]. Activation of pexophagy involves Pex5-dependent translocation of the kinase ataxia–telangiectasia mutated (ATM) to peroxisomes. In response to exogenously applied H2O2 or clofibrate treatment, which increases peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation and leads to ROS production, ATM is activated and promotes autophagy by inhibiting signaling from the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC)1. ROS-activated ATM also phosphorylates Pex5. This in turn primes Pex5 for an E3 ligase-mediated ubiquitination and p62-mediated autophagy (Figure 2) [44,45]. Together, these studies suggest that excessive ROS production may be a signal of peroxisomal dysfunction to trigger pexophagy. Hypoxia also activates pexophagy through a process dependent on hypoxia-inducible factor 2α [46]. Recently, Pex2 was shown to be the E3 ligase that mediates Pex5 ubiquitination during starvation-induced pexophagy [47]. Whether Pex2 is a general regulator of pexophagy, including the degradation induced by ROS and hypoxia, remains unclear.

Figure 2. Removal of Dysfunctional Peroxisomes by Pexophagy.

ROS-activated ATM kinase both signals to mTORC1 to inhibit its suppression of autophagy and phosphorylates Pex5 to promote its ubiquitination and its subsequent binding of p62, thus targeting the peroxisome for degradation. Abbreviations: ATM, ataxia–telangiectasia mutated; LC3, microtubule-associated protein light chain 3; mTORC1, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1; Pex5, peroxisomal biogenesis factor 5; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; Ub, ubiquitinated; ULK1, Unc-51-like autophagy activating kinase 1.

Peroxisomal Dysfunction in Disease Development

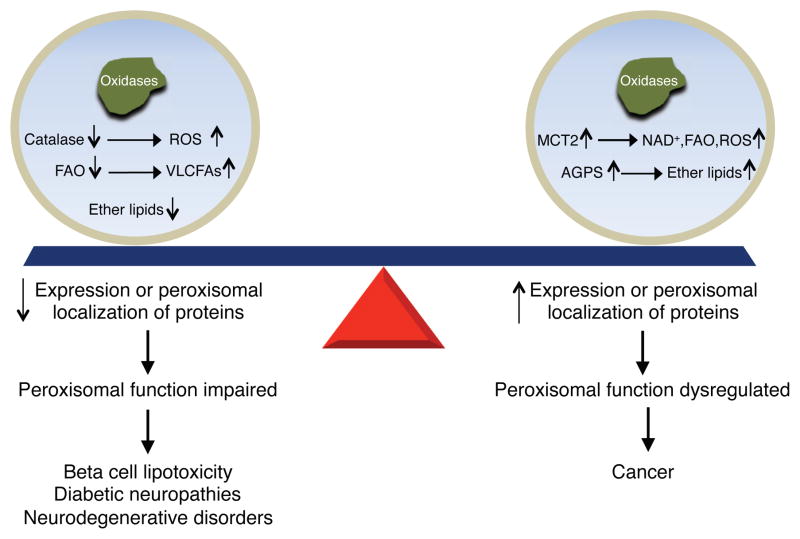

Normal physiology requires not only a balance between peroxisomal biogenesis and degradation, but also proper maintenance of peroxisomal function. Impaired or dysregulated peroxisomal function has been described as a component of a variety of age-related diseases, including diabetes, neurological disorders, and cancer, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Peroxisomal Dysfunction in Age-Related Diseases.

Decreased expression or peroxisomal localization of proteins involved in ROS and lipid metabolism is observed in metabolic and neurodegenerative disorders. Increased expression or peroxisomal compartmentalization of different metabolic enzymes is observed in cancer. Abbreviations: AGPS, alkylglycerone phosphate synthase; FAO, fatty acid oxidation; MCT2, monocarboxylate transporter 2; ROS, reactive oxygen species; VLCFA, very long chain fatty acid.

Peroxisomal Dysfunction in Diabetes and Related Complications

Diabetes is characterized by abnormally high levels of glucose in the blood, which if left untreated, results in numerous complications, including end-stage renal disease, blindness, cardiovascular disease, and nontraumatic limb amputation. Diabetes is classified into two major types. Type 1 diabetes results from the autoimmune destruction of the insulin-producing beta cells of the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas and accounts for 5–10% of all cases of the disease. These patients absolutely require exogenous insulin for survival. Type 2 diabetes, which is significantly more common, is associated with obesity and insulin resistance. Beta cells compensate for insulin resistance by hypersecretion of insulin. Ultimately, beta cell failure ensues and frank diabetes develops [48].

Nonesterified fatty acids (NEFAs) have long been known to exert lipotoxicity in insulin-producing cells. Oxidative stress is a major mediator of lipotoxicity [49]. Conventional wisdom holds that increased mitochondrial respiration leads to H2O2 formation through the electron transport chain, resulting in cellular stress [50]. Using an H2O2-sensitive fluorescent protein, this notion was challenged by the observation that the subcellular site of ROS production in palmitate-treated beta cells is primarily peroxisomes and not mitochondria. Moreover, overexpression of catalase in peroxisomes, but not mitochondria, reduces oxidative stress and protects beta cells from palmitate-induced lipotoxicity. This suggests that H2O2 production in peroxisomes rather than mitochondria is primarily responsible for NEFA-induced lipotoxicity in beta cells [51].

Peroxisomal H2O2 formation is not just problematic in islets, but also in the development of diabetic neuropathies and osteoarthritis [31,52,53]. Treating cultured human retinal cells or diabetic mice with peroxisome-localized catalase protein reduces oxidative stress and improves intraretinal calcium channel activity [54]. Conversely, knockout of catalase in diabetic mice increases oxidative stress and features of nephropathy as compared to wild-type diabetic mice, despite similar levels of hyperglycemia in the two groups. Furthermore, catalase inactivation results in impaired peroxisomal biogenesis and increased renal lipid accumulation. This suggests that increased oxidative stress results in peroxisomal dysfunction that exacerbates diabetic renal injury [31]. Peroxisomal dysfunction has also been implicated in the early incidence and development of osteoarthritis in diabetic patients. Peroxisomal gene expression and catalase activity were shown to be downregulated in chondrocytes isolated from diabetes-associated osteoarthritis patients [52].

Dysregulation of Peroxisomal Lipid Metabolism in Neurodegenerative Disorders

Inherited peroxisomal disorders are associated with severe neurological dysfunctions, including hypotonia, seizures, cerebellar ataxia, sensory impairments, and developmental deficits [4]. Recent studies suggest that peroxisomal function also declines with age and may be linked to age-related neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). AD is characterized by β-amyloid accumulation and formation of tau tangles, resulting in inflammation and neuronal cell death. FA composition in the brains of AD patients is altered. Notably, levels of VLCFAs in cortical regions of the brain are increased in these patients, suggesting a possible defect in peroxisomal beta oxidation [55]. Consistent with this possibility, treatment of rats with a high fat diet or streptozotocin to induce diabetes impairs beta oxidation in the cerebral cortex, resulting in accumulation of β-amyloid peptide in the brain [56]. Accumulation of β amyloid is also associated with induction of ROS, and treatment of primary rat neuronal cells with peroxisomally targeted catalase protects from a soluble form of amyloid β peptide called amyloid-β-derived diffusible ligands [57].

Peroxisomal lipid synthesis is impaired in AD patients in addition to peroxisomal FA oxidation, suggesting a general defect in peroxisomal function. In the gyrus frontalis of human postmortem AD brains, reduced plasmalogen levels are observed in addition to increased amounts of VLCFAs. These phenotypes are exacerbated in brains exhibiting neurofibrillary tangles in addition to neuritic plaques, as compared to neuritic plaques alone [55]. One of the early features of AD is synaptic vesicle loss, which is likely coincident with cognitive impairment. The synaptic vesicle is enriched in ether lipids [58], and neurotransmitter release from these vesicles into the presynaptic cleft is impaired in synaptosomes isolated from the brains of mice with knockout of the ether lipid synthetic enzyme dihydroxacetone phosphate acyl transferase (DHAPAT) [59]. Examination of 29 independent neurolipidomic datasets consistently revealed increased hydrolysis of ethanolamine-containing membrane plasmalogens and decreased levels of other ether-linked structural phospholipids in AD, potentially contributing to the vesicular depletion [60]. Taken together, these data indicate a role for peroxisomal dysfunction in both the pathogenesis and progressive worsening of AD.

Peroxisomal dysfunction has also been linked to other neurodegenerative disorders, including Parkinson’s disease (PD). PD is characterized by accumulation of the protein α-synuclein (αS) and underproduction of the neurotransmitter dopamine. Plasmalogen levels are significantly reduced in postmortem human frontal cortex lipid rafts with PD [61]. Supplementation of plasmalogens in a mouse model of PD, using the orally bioavailable ethanolamine plasmalogen precursor PPI-1011, reverses striatal dopamine loss [62]. The mechanism through which this occurs is unknown. In this study, PPI-1011 significantly increased plasmalogen levels in serum but not in brain tissue, which the authors conjectured could have been due to challenges in assaying small quantities of brain tissue for plasmalogen species. Another possibility is that neuroprotection was provided through increases in docosahexaenoic acid or lipoic acid levels, which are also increased by PPI-1011 [62]. Peroxisomal dysfunction may contribute to the accumulation of αS in the brain. The normal function of αS is thought to be binding to presynaptic vesicles and promoting fusion with neurotransmitter vesicles. Recent studies in peroxisome-deficient (Pex3 mutant) yeast models of PD found that αS could not bind to lipid droplets in lipid-loaded peroxisome-deficient yeast cells, as it did in wild type cells [63]. More work is necessary to establish whether peroxisomal dysfunction can affect αS function in mammalian brains.

Altered Peroxisomal Metabolism in Cancer

Lipid metabolism is known to be dysregulated in cancer cells. Cancer cells typically exhibit increased lipogenesis in order to support membrane synthesis and generation of oncogenic lipid signaling molecules [64]. Ether lipids specifically are upregulated in a wide variety of neoplastic tissues [65,66]. Although their precise role in cancer pathogenicity is unclear, ether lipids are important for the organization of detergent-resistant membrane microdomains [2]. Ether lipids may also be required for the assembly and release of exosomes, 40–100-nm vesicles secreted by cells, which may be involved in cell–cell communication and promoting cancer metastasis [67].

Recent studies suggest a link between ether lipid synthesis and cancer progression. Overexpression of the tumor suppressor H-rev107 has been shown to result in mislocalization of various peroxisomal proteins and a marked decrease in ether lipid levels in cultured cells [68]. H-rev107 interacts with and inhibits the function of Pex19 [69], a cytosolic chaperone involved in the import of peroxisomal membrane proteins [70], including the peroxisomal lipid synthetic enzyme PexRAP [14]. H-rev107 itself is an inhibitor of the oncogene H-ras, and transformation of H-ras into moderately aggressive cell lines results in increased expression of the ether lipid synthetic enzyme alkylglycerone phosphate synthase (AGPS). AGPS expression is elevated in a variety of aggressive cancer cells. Its knockdown results in impaired metrics of cancer pathogenicity and reduced levels of oncogenic lipid signals, while its overexpression increases cancer cell aggressiveness [71,72]. A small-molecule screen to find inhibitors of AGPS identified several candidate compounds. One such compound appears to be particularly promising in lowering ether lipid levels and impairing survival and migration of cancer cells [73].

Ether lipid synthesis is not the only peroxisomal metabolic process that is upregulated in cancer. The enzyme α-methylacyl-CoA racemase (AMACR), which localizes to both mitochondria and peroxisomes and catalyzes a key chiral inversion reaction in branched-chain lipid metabolism and bile acid synthesis, is upregulated particularly in prostate cancer and in some other cancers [74,75]. Knockdown of AMACR in myxofibrosarcoma cell lines reduces expression of markers of cell proliferation and suppresses cell growth [76]. The mechanism through which AMACR expression or activity is associated with cancer is unknown, although gene amplification at 5p13.3 drives AMACR overexpression in 20% of myxofibrosarcomas [76]. It is unclear what drives overexpression of AMACR in the remainder of cases. One hypothesized role for AMACR overexpression is that it may facilitate a switch from glucose metabolism to FA metabolism during cancer [77]. Regardless of its precise role in cancer progression, AMACR has become an important diagnostic parameter for prostate cancer and a potential target for cancer treatment [75,76].

In addition to changes in the expression levels of peroxisomal proteins, altered peroxisomal compartmentalization of metabolic enzymes might also affect the metabolism of cancer cells. Cancer cells exhibit a high rate of glycolysis, followed by lactic acid fermentation, even if sufficient oxygen is present, to support mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. This observation is known as the Warburg effect [78]. Because glycolysis is an inefficient way to generate ATP as opposed to the complete oxidation of glucose, the precise role of the high rate of aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells is unclear. Several possible explanations have been proposed, including generation of metabolic intermediates and reducing equivalents to support biomass production, acidification of the tumor microenvironment to promote invasiveness, and production of cellular signaling molecules through ROS metabolism [79]. Emerging studies suggest that isoforms of various glucose metabolism enzymes, including GAPDH, 3-phosphoglycerate kinase, and lactate dehydrogenase are partially localized in peroxisomes through a C-terminal peroxisomal targeting sequence generated by ribosomal read-through of a stop codon [80–82]. Whether the peroxisomal localization of these metabolic enzymes is a cancer-associated dysregulation related to the Warburg effect remains to be determined. However, monocarboxylate transporter (MCT)2, another peroxisome-localized metabolic enzyme that regulates pyruvate for lactate exchange (converting NADH to NAD+ in the process to fuel peroxisomal beta oxidation and promote ROS production) [83], is indeed involved in cancer [84]. Increased peroxisomal localization of MCT2 is associated with malignant transformation of prostate cancer cells and its knockdown attenuates growth of prostate cancer cells [85,86].

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Increasing evidence suggests that peroxisomal function is affected with aging, due to altered expression or localization of peroxisomal matrix proteins. Impaired peroxisomal function has been implicated in neurodegenerative disorders, beta cell failure, and diabetes-related complications, while dysregulated peroxisomal function is associated with cancer. The molecular mechanisms underlying the role of peroxisomal dysfunction in these diseases are not well understood (see Outstanding Questions). Moreover, it is unclear whether peroxisomal dysfunction is the cause or a response to disease. The severe phenotypes, including neurologic degeneration, associated with inherited peroxisomal disorders [3,4] suggest a causative role of peroxisomal dysfunction in disease.

Outstanding Questions.

How do peroxisomes leverage their relationship with mitochondria to maintain lipid metabolism and oxidative homeostasis? What is the physiological basis for the organelle-specific differences in chain length specificity for FA oxidation?

Does disruption of peroxisomal lipid metabolism directly affect disease pathogenesis through changes in membrane structure or indirectly through oxidative imbalance?

Do cancer cells exploit peroxisomal compartmentalization of multiple metabolic pathways to more efficiently regulate their metabolism?

Do ether lipids play a structural or signaling role in promoting cancer progression?

Could peroxisomal metabolism be safely targeted to prevent or treat aging-related disorders?

Could dietary interventions be used to alter peroxisomal activities to impact the clinical course of neurologic diseases?

Based on the essential role of peroxisomes in lipid and ROS metabolism, peroxisomal dysfunction can potentially contribute to the pathogenesis of age-related diseases through impaired oxidative homeostasis, membrane lipid remodeling, and/or generation of lipid signaling molecules. For example, impaired peroxisomal function leads to abnormal ether lipid synthesis, which could interfere with insulin and/or synaptic vesicle structure and function. Future research is necessary to determine mechanistically how peroxisomal processes relate to important cellular functions like neurotransmission and insulin secretion, and whether these processes could be manipulated through dietary or pharmacological means for disease interventions. Furthermore, additional work is needed to determine whether an increased peroxisomal compartmentalization of metabolic pathways is a mechanism exploited by cancer cells to improve the efficiency of biomass production. Lending support to this notion, compartmentalization of heterologous metabolic pathways in yeast peroxisomes dramatically improves product titer, presumably due to isolation of pathways in a compact and suitable environment [87,88].

Our aim here was to bring the relationship between peroxisomal dysfunction and common age-related diseases to the forefront of the lipid metabolism field, and to encourage future investigation into this area of research still in its infancy. A better understanding of how peroxisome function is altered during aging might lead to new approaches to treat disease.

Trends Box.

Peroxisomes are multifunctional organelles involved in ROS metabolism, fatty acid oxidation, ether lipid synthesis, bile acid synthesis, and cholesterol transport.

Peroxisomal homeostasis is an important regulator of health and old or defective peroxisomes are removed through autophagy.

Disruption of peroxisomal function can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction, reflecting the intimate link between the two organelles.

Accumulating evidence suggests that peroxisomal function is altered with aging due to changes in the expression and/or localization of peroxisomal matrix proteins.

Impaired peroxisomal function has been implicated in neurodegenerative disorders and diabetes, while dysregulated peroxisomal function is associated with cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R00 DK094874 and T32 DK007120.

Glossary

- Alpha oxidation

process by which branched-chain FAs undergo oxidative decarboxylation to remove the terminal carboxyl group as CO2

- Autophagy

process for degradation of intracellular components through formation of a double membrane structure called autophagosome around the cargo, which then fuses with lysosomes

- Beta oxidation

process of FA catabolism by which two carbons are removed from the carboxyl terminus of a fatty acyl CoA molecule. The process is named as such because the beta carbon of the FA undergoes oxidation

- Ether lipid

phospholipid characterized by an ether linkage of a long-chain alkyl moiety at one or more carbons of the glycerol backbone, as opposed to the more typical ester linkage

- Lipogenesis

endogenous generation of fats using carbohydrates as precursors

- Lipotoxicity

accumulation of lipids in tissues other than adipose tissue, resulting in metabolic dysfunction

- Pexophagy

selective autophagy of peroxisomes

- Plasmalogen

ether lipid characterized by a vinyl ether linkage at the sn-1 position of the glycerol backbone

- Reactive oxygen species (ROS)

chemically reactive species containing a reduced form of oxygen

- Warburg effect

phenomenon characterized by a high rate of aerobic glycolysis observed in cancer cells

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schrader M, et al. Peroxisome interactions and cross-talk with other subcellular compartments in animal cells. Subcell Biochem. 2013;69:1–22. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-6889-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lodhi IJ, Semenkovich CF. Peroxisomes: a nexus for lipid metabolism and cellular signaling. Cell Metab. 2014;19:380–392. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braverman NE, et al. Peroxisome biogenesis disorders in the Zellweger spectrum: an overview of current diagnosis, clinical manifestations, and treatment guidelines. Mol Genet Metab. 2016;117:313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waterham HR, Ebberink MS. Genetics and molecular basis of human peroxisome biogenesis disorders. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Mol Basis Dis. 2012;1822:1430–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fransen M, et al. Aging, age-related diseases and peroxisomes. In: del Rio LA, editor. Peroxisomes and their Key Role in Cellular Signaling and Metabolism. Springer; 2013. pp. 45–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lousa CDM, et al. Intrinsic acyl-CoA thioesterase activity of a peroxisomal ATP binding cassette transporter is required for transport and metabolism of fatty acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:1279–1284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218034110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schrader M, et al. Peroxisome-mitochondria interplay and disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2015;38:681–702. doi: 10.1007/s10545-015-9819-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noland RC, et al. Peroxisomal-mitochondrial oxidation in a rodent model of obesity-associated insulin resistance. Am J Physiol - Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E986–E1001. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00399.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh I, et al. Lignoceric acid is oxidized in the peroxisome: implications for the Zellweger cerebro-hepato-renal syndrome and adrenoleukodystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1984;81:4203–4207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.13.4203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddy JK, Hashimoto T. Peroxisomal β-oxidation and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α: an adaptive metabolic system. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001;21:193–230. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.21.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wanders RJA. Peroxisomes and their key role in cellular signaling and metabolism. Subcell Biochem. 2013;69:23–44. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-6889-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wanders RJA. Metabolic functions of peroxisomes in health and disease. Biochimie. 2014;98:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hajra AK, Das AK. Lipid Biosynthesis in Peroxisomes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;804:129–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb18613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lodhi IJ, et al. Inhibiting adipose tissue lipogenesis reprograms thermogenesis and PPARγ activation to decrease diet-induced obesity. Cell Metab. 2012;16:189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lodhi IJ, et al. Peroxisomal lipid synthesis regulates inflammation by sustaining neutrophil membrane phospholipid composition and viability. Cell Metab. 2015;21:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodemer C, et al. Inactivation of ether lipid biosynthesis causes male infertility, defects in eye development and optic nerve hypoplasia in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1881–1895. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amaral A, et al. Human sperm tail proteome suggests new endogenous metabolic pathways. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:330–342. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.020552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyazaki C, et al. Altered phospholipid molecular species and glycolipid composition in brain, liver and fibroblasts of Zellweger syndrome. Neurosci Lett. 2013;552:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Facciotti F, et al. Peroxisome-derived lipids are self antigens that stimulate invariant natural killer T cells in the thymus. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:474–480. doi: 10.1038/ni.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferdinandusse S, et al. Bile acids: the role of peroxisomes. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:2139–2147. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R900009-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovacs WJ, et al. Localization of the pre-squalene segment of the isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway in mammalian peroxisomes. Histochem Cell Biol. 2007;127:273–290. doi: 10.1007/s00418-006-0254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wanders RJ, Waterham HR. Biochemistry of mammalian peroxisomes revisited. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:295–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu BB, et al. Cholesterol transport through lysosome-peroxisome membrane contacts. Cell. 2015;161:291–306. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Legakis JE, et al. Peroxisome senescence in human fibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4243–4255. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-06-0322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boveris A, et al. The cellular production of hydrogen peroxide. Biochem J. 1972;128:617–630. doi: 10.1042/bj1280617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fransen M, et al. Role of peroxisomes in ROS/RNS-metabolism: implications for human disease. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Mol Basis Dis. 2012;1822:1363–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antonenkov VD, et al. Peroxisomes are oxidative organelles. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:525–537. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nunnari J, Suomalainen A. Mitochondria: in sickness and in health. Cell. 2012;148:1145–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terlecky SR, et al. Peroxisomes, oxidative stress, and inflammation. World J Biol Chem. 2012;3:93–97. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v3.i5.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ivashchenko O, et al. Intraperoxisomal redox balance in mammalian cells: oxidative stress and interorganellar cross-talk. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:1440–1451. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-11-0919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hwang I, et al. Catalase deficiency accelerates diabetic renal injury through peroxisomal dysfunction. Diabetes. 2012;61:728–738. doi: 10.2337/db11-0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Narayan V, et al. Deep proteome analysis identifies age-related processes in C. elegans. Cell Syst. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.06.011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Dodt G, Gould SJ. Multiple PEX genes are required for proper subcellular distribution and stability of Pex5p, the PTS1 receptor: evidence that PTS1 protein import is mediated by a cycling receptor. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1763–1774. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu X, et al. Recent advances in peroxisomal matrix protein import. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:484–489. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freitas MO, et al. PEX5 protein binds monomeric catalase blocking its tetramerization and releases it upon binding the n-terminal domain of PEX14. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:40509–40519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.287201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma C, et al. Redox-regulated cargo binding and release by the peroxisomal targeting signal receptor, Pex5. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:27220–27231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.492694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Apanasets O, et al. PEX5, the shuttling import receptor for peroxisomal matrix proteins, is a redox-sensitive protein: PTS1 protein import and oxidative stress. Traffic. 2014;15:94–103. doi: 10.1111/tra.12129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huybrechts SJ, et al. Peroxisome dynamics in cultured mammalian cells. Traffic. 2009;10:1722–1733. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manjithaya R, et al. Molecular mechanism and physiological role of pexophagy. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1367–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zientara-Rytter K, Subramani S. Autophagic degradation of peroxisomes in mammals. Biochem Soc Trans. 2016;44:431–440. doi: 10.1042/BST20150268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rogov V, et al. Interactions between autophagy receptors and ubiquitin-like proteins form the molecular basis for selective autophagy. Mol Cell. 2014;53:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oku M, Sakai Y. Pexophagy in yeasts. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Mol Cell Res. 2016;1863:992–998. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nordgren M, et al. Export-deficient monoubiquitinated PEX5 triggers peroxisome removal in SV40 large T antigen-transformed mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Autophagy. 2015;11:1326–1340. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1061846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang J, et al. ATM functions at the peroxisome to induce pexophagy in response to ROS. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:1259–1269. doi: 10.1038/ncb3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang J, et al. A tuberous sclerosis complex signalling node at the peroxisome regulates mTORC1 and autophagy in response to ROS. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:1186–1196. doi: 10.1038/ncb2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walter KM, et al. Hif-2α promotes degradation of mammalian peroxisomes by selective autophagy. Cell Metab. 2014;20:882–897. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sargent G, et al. PEX2 is the E3 ubiquitin ligase required for pexophagy during starvation. J Cell Biol. 2016;214:677–690. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201511034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ashcroft FM, Rorsman P. Diabetes mellitus and the β cell: the last ten years. Cell. 2012;148:1160–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hauck AK, Bernlohr DA. Oxidative stress and lipotoxicity. J Lipid Res. 2016 doi: 10.1194/jlr.R066597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Supale S, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in pancreatic β cells. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23:477–487. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elsner M, et al. Peroxisome-generated hydrogen peroxide as important mediator of lipotoxicity in insulin-producing cells. Diabetes. 2011;60:200–208. doi: 10.2337/db09-1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim D, et al. Peroxisomal dysfunction is associated with up-regulation of apoptotic cell death via miR-223 induction in knee osteoarthritis patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Bone. 2014;64:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vasko R, et al. Endothelial peroxisomal dysfunction and impaired pexophagy promotes oxidative damage in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute kidney injury. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:211–230. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giordano CR, et al. Catalase therapy corrects oxidative stress-induced pathophysiology in incipient diabetic retinopathy. Investig Opthalmology Vis Sci. 2015;56:3095. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-16194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kou J, et al. Peroxisomal alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2011;122:271–283. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0836-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shi Y, et al. Elevation of cortical C26:0 due to the decline of peroxisomal β-oxidation potentiates amyloid β generation and spatial memory deficits via oxidative stress in diabetic rats. Neuroscience. 2016;315:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Giordano CR, et al. Amyloid-beta neuroprotection mediated by a targeted antioxidant. Sci Rep. 2014;4 doi: 10.1038/srep04983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Puchkov D, Haucke V. Greasing the synaptic vesicle cycle by membrane lipids. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23:493–503. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brodde A, et al. Impaired neurotransmission in ether lipid-deficient nerve terminals. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:2713–2724. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bennett SAL, et al. Using neurolipidomics to identify phospholipid mediators of synaptic (dys)function in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Physiol. 2013;4 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fabelo N, et al. Severe alterations in lipid composition of frontal cortex lipid rafts from Parkinson’s disease and incidental Parkinson’s disease. Mol Med. 2011;17:1107. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miville-Godbout E, et al. Plasmalogen augmentation reverses striatal dopamine loss in MPTP mice. PLOS ONE. 2016;11:e0151020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang S, et al. A peroxisome biogenesis deficiency prevents the binding of alpha-synuclein to lipid droplets in lipid-loaded yeast. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;438:452–456. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.07.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Benjamin DI, et al. Global profiling strategies for mapping dysregulated metabolic pathways in cancer. Cell Metab. 2012;16:565–577. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Snyder F, Wood R. Alkyl and alk-1-enyl ethers of glycerol in lipids from normal and neoplastic human tissues. Cancer Res. 1969;29:251–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saito K, et al. Lipidomic signatures and associated transcriptomic profiles of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28932. doi: 10.1038/srep28932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Phuyal S, et al. The ether lipid precursor hexadecylglycerol stimulates the release and changes the composition of exosomes derived from PC-3 cells. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:4225–4237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.593962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Uyama T, et al. Regulation of peroxisomal lipid metabolism by catalytic activity of tumor suppressor H-rev107. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2706–2718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.267575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Uyama T, et al. Interaction of phospholipase A/acyltransferase-3 with Pex19p: a possible involvement in the down-regulation of peroxisomes. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:17520–17534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.635433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jones JM, et al. PEX19 is a predominantly cytosolic chaperone and import receptor for class 1 peroxisomal membrane proteins. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:57–67. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200304111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Benjamin DI, et al. Ether lipid generating enzyme AGPS alters the balance of structural and signaling lipids to fuel cancer pathogenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:14912–14917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310894110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhu Y, et al. Role and mechanism of the alkylglycerone phosphate synthase in suppressing the invasion potential of human glioma and hepatic carcinoma cells in vitro. Oncol Rep. 2014 doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Piano V, et al. Discovery of inhibitors for the ether lipid-generating enzyme AGPS as anti-cancer agents. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:2589–2597. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rubin MA, et al. α-methylacyl coenzyme A racemase as a tissue biomarker for prostate cancer. JAMA. 2002;287:1662–1670. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.13.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lloyd MD, et al. α-Methylacyl-CoA racemase (AMACR): metabolic enzyme, drug metabolizer and cancer marker P504S. Prog Lipid Res. 2013;52:220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li CF, et al. AMACR amplification in myxofibrosarcomas: a mechanism of overexpression that promotes cell proliferation with therapeutic relevance. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:6141–6152. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu Y. Fatty acid oxidation is a dominant bioenergetic pathway in prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2006;9:230–234. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vander Heiden MG, et al. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liberti MV, Locasale JW. The Warburg effect: how does it benefit cancer cells? Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Freitag J, et al. Cryptic peroxisomal targeting via alternative splicing and stop codon read-through in fungi. Nature. 2012;485:522–525. doi: 10.1038/nature11051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schueren F, et al. Peroxisomal lactate dehydrogenase is generated by translational readthrough in mammals. eLife. 2014;3:e03640. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stiebler AC, et al. Ribosomal readthrough at a short UGA stop codon context triggers dual localization of metabolic enzymes in fungi and animals. PLOS Genet. 2014;10:e1004685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McClelland GB, et al. Peroxisomal membrane monocarboxylate transporters: evidence for a redox shuttle system? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304:130–135. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00550-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Doherty JR, Cleveland JL. Targeting lactate metabolism for cancer therapeutics. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3685–3692. doi: 10.1172/JCI69741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Valença I, et al. Localization of MCT2 at peroxisomes is associated with malignant transformation in prostate cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2015;19:723–733. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pertega-Gomes N, et al. Epigenetic and oncogenic regulation of SLC16A7 (MCT2) results in protein over-expression, impacting on signalling and cellular phenotypes in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:21675–21684. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.DeLoache WC, et al. Towards repurposing the yeast peroxisome for compartmentalizing heterologous metabolic pathways. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11152. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhou YJ, et al. Harnessing yeast peroxisomes for biosynthesis of fatty-acid-derived biofuels and chemicals with relieved side-pathway competition. J Am Chem Soc. 2016 doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b07394. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jacs.6b07394. [DOI] [PubMed]