Abstract

Ethnopharmacological Relevance. Dendrobii Officinalis Caulis, the stems of Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo, as a tonic herb in Chinese materia medica and health food in folk, has been utilized for the treatment of yin-deficiency diseases for decades. Methods. Information for analysis of Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo was obtained from libraries and Internet scientific databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, Wiley InterScience, Ingenta, Embase, CNKI, and PubChem. Results. Over the past decades, about 190 compounds have been isolated from Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo. Its wide modern pharmacological actions in hepatoprotective effect, anticancer effect, hypoglycemic effect, antifatigue effect, gastric ulcer protective effect, and so on were reported. This may mainly attribute to the major and bioactive components: polysaccharides. However, other small molecule components require further study. Conclusions. Due to the lack of systematic data of Dendrobium officinale, it is important to explore its ingredient-function relationships with modern pharmacology. Recently, studies on the chemical constituents of Dendrobium officinale concentrated in crude polysaccharides and its structure-activity relationships remain scant. Further research is required to determine the Dendrobium officinale toxicological action and pharmacological mechanisms of other pure ingredients and crude extracts. In addition, investigation is needed for better quality control and novel drug or product development.

1. Introduction

Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo spreads in several countries over the world, such as Japan, United States, and Australia, and it distributes more widely in China [1] (Table 1). Modern pharmacology research has confirmed that Dendrobium officinale and its polysaccharide fraction possess anticancer, hepatoprotective, hypolipidemic, antifatigue, antioxidant, anticonstipation, hypoglycemic, gastric ulcer protective, and antihypertensive effects, immunoenhancement, and so on [2–4].

Table 1.

The taxonomic classification, names, and distribution of Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo.

| Synonyms | Dendrobium catenatum Lindl., Gen. Sp. Orchid. Pl.: 84 (1830). | Dendrobium stricklandianum Rchb.f., Gard. Chron., n.s., 7: 749 (1877). | Callista stricklandiana (Rchb.f.) Kuntze, Revis. Gen. Pl. 2: 655 (1891). | Dendrobium tosaense Makino, J. Bot. 29: 383 (1891). | Dendrobium pere-fauriei Hayata, Icon. Pl. Formosan. 6: 70 (1916). | Dendrobium tosaense var. pere-fauriei (Hayata) Masam., J. Soc. Trop. Agric. 4: 196 (1933). | Dendrobium officinale Kimura & Migo, J. Shanghai Sci. Inst. 3: 122 (1936). |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic classification | Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life: Plantae > Tracheophyta > Liliopsida > Asparagales > Orchidaceae > Dendrobium > Dendrobium catenatum Lindl. | IUCN Red List: Plantae > Tracheophyta > Liliopsida > Orchidales > Orchidaceae > Dendrobium > Dendrobium officinale | NCBI Taxonomy: Eukaryota > Viridiplantae > Streptophyta > Streptophytina > Embryophyta > Tracheophyta > Euphyllophyta > Spermatophyta > Magnoliophyta > Mesangiospermae > Liliopsida > Petrosaviidae > Asparagales > Orchidaceae > Epidendroideae > Epidendroideae incertae sedis > Dendrobiinae > Dendrobium > Dendrobium catenatum | Taxonomic Hierarchy of COL-China 2012: Plantae > Angiospermae > Monocotyledoneae > Microspermae > Orchidaceae > Dendrobium > Dendrobium tosaense | Tropicos resource: Equisetopsida C. Agardh > Asparagales Link > Orchidaceae Juss. > Callista Lour. > Callista stricklandiana Kuntze | Tropicos resource: Equisetopsida C. Agardh > Asparagales Link > Orchidaceae Juss. > Dendrobium Sw. > Dendrobium officinale Kimura & Migo |

|

| Distribution | Japan > Kyushu | United States > Missouri > Saint Louis City | Australia > New South Wales | China > Taiwan, Anhui, Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangxi, Sichuan, Yunnan, Xizang, etc. | |||

| Common name | 鐵皮石斛 (tiepishihu) | 黃石斛 (huangshihu) | |||||

| Reference |

http://www.kew.org/ http://www.theplantlist.org/ |

http://www.catalogueoflife.org/ http://www.tropicos.org/ |

http://www.gbif.org/ http://www.eol.org/ |

http://frps.eflora.cn/ | [50] [51] |

[10] | |

Since 1994, polysaccharides of Dendrobium officinale have been extracted and analyzed [5], and polysaccharides gradually became research focus of Dendrobium officinale. Recently, the chemical compositions and pharmacological effects of Dendrobium officinale have attracted more and more attention. In this review, from substantial data about Dendrobium officinale, approximately 190 monomer compositions and plenty of pharmacological researches studied in vivo and/or in vitro were summarized. In addition, the development of artificial cultivation of Dendrobium officinale accelerates the promotion of its industrialization in China. Patents and health care products were also improved by the combination of production and research mode.

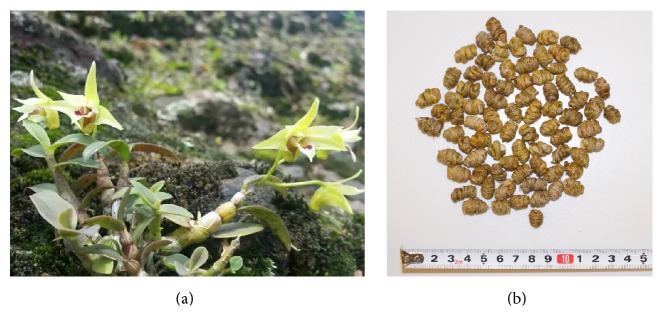

2. Pharmaceutical Botany

Dendrobium, pertaining to the second largest family, Orchidaceae, includes approximately l,400 species worldwide distributed from tropical Asia to Oceania [6]. There are 74 species and 2 variants of genus Dendrobium Sw. in China [7]. Some of them can be processed as Dendrobii Caulis (Chinese: 石斛, shihu) of Chinese materia medica [8]. In 2005 Chinese Pharmacopoeia (ChP), tiepishihu (Chinese: 鐵皮石斛) was one species of medicinal shihu called Dendrobium candidum Wall. ex Lindl. [9]; however this Latin name was later disputed and considered the synonym of Dendrobium moniliforme (L.) Sw. [10, 11]. In 2010 ChP, tiepishihu was renamed as Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo (aka Dendrobium officinale, Figure 1(a)). This Latin name was firstly denominated by two Japanese scholars in 1936 when they found the new species of Dendrobium in China [12]. Facilitating the preservation, the fibrous stems of Dendrobium officinale can be twisted into a spiral and dried as tiepifengdou (Figure 1(b)) or directly cut into sections and dried as well. What is more, in 2010 ChP, tiepishihu was initially isolated as one single medicine; its processed stem was called Dendrobii Officinalis Caulis (valid botanical name: Dendrobium catenatum Lindl., taxonomic classification and synonyms in Table 1); in the meanwhile, Dendrobium nobile Lindl., Dendrobium chrysotoxum Lindl., Dendrobium fimbriatum Hook., and their similar species were collectively referred to as shihu [13].

Figure 1.

(a) Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo; (b) tiepifengdou.

3. Ethnopharmacological Use

The stems of Dendrobium officinale are mainly used as health food in folk. There are a variety of methods to enjoy its fresh stems, for example, chewing, juicing, decocting, and making dishes [14]. In addition, combining with other tonic Chinese herbs is viable, such as “Panacis Quinquefolii Radix” (xiyangshen, American Ginseng), “Lycii Fructus” (gouqizi, Barbary Wolfberry Fruit), and “Dioscoreae Rhizoma” (shanyao, Rhizome of Common Yam) [15]. As reported, the combination of Dendrobium officinale and American Ginseng could strengthen cell-mediated immunity, humoral immunity, and monocyte-macrophages functions of mice [16].

The functions and indications of tiepishihu and shihu are quite similar in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) [17, 18]. However, TCM physicians use shihu more frequently than tiepishihu. As precious medicinal materials, maybe the high price limits the application of tiepishihu. Because of the output promotion, Dendrobium officinale gradually got more applications, especially in recent decades. Research showed that low-grade fever after gastric cancer operations, atrophic gastritis, mouth ulcers, and diabetes were treated by the fresh Dendrobium officinale in TCM [19]. Combined with modern medicine, Dendrobium officinale can be used to treat many diseases including Sjögren's syndrome, gastric ulcer, alcoholic liver injury, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, obesity, rheumatoid arthritis, hypertensive stroke, cataract, weak constitution, or subhealth [2, 20–22]. However, these functions were from an earlier investigation and need further research to probe.

4. Phytochemistry

From Dendrobium officinale, at least 190 compounds by far were isolated, mainly including polysaccharides, phenanthrenes, bibenzyls, saccharides and glycosides, essential oils, alkaloids, and other compounds (Table 2).

Table 2.

Chemical components in Dendrobium officinale.

| Number | Compounds | PubChem CID | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenanthrenes | |||

| 1 | 2,3,4,7-Tetramethoxyphenanthrene | [52] | |

| 2 | 2,5-Dihydroxy-3,4-dimethoxyphenanthrene | [52] | |

| 3 | 1,5-Dicarboxy-1,2,3,4-tetramethoxyphenanthrene | [52] | |

| 4 | 2,4,7-Trihydroxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene | 21678577 | [41] |

| 5 | Denbinobin | 10423984 | [41] |

| 6 | Erianin | 356759 | [53] |

| 7 | 1,5,7-Trimethoxyphenanthrene-2,6-diol | 11779542 | [52] |

| 8 | 3,4-Dimethoxyphenanthrene-2,7-diol | 158975 | [52] |

| 9 | 2,4-Dimethoxyphenanthrene-3,5-diol | 44445443 | [52] |

| Bibenzyls | |||

| 10 | 3,4-Dihydroxy-5,4′-dimethoxybibenzyl | [54] | |

| 11 | Chrysotobibenzyl | 3086528 | [53] |

| 12 | 4′,5-Hydroxy-3,3′-dimethoxybenzyl | [55] | |

| 13 | 3,4′-Dihydroxy-5-methoxybibenzyl | [41] | |

| 14 | Dendrocandin A | 102476850 | [56] |

| 15 | Dendrocandin B | 91017475 | [56] |

| 16 | Dendrocandin C | 25208514 | [56] |

| 17 | Dendrocandin D | 25208516 | [56] |

| 18 | Dendrocandin E | 25208515 | [56] |

| 19 | Dendrocandin F | [56] | |

| 20 | Dendrocandin G | [56] | |

| 21 | Dendrocandin H | [56] | |

| 22 | Dendrocandin I | 101481782 | [56] |

| 23 | Dendrocandin J | [56] | |

| 24 | Dendrocandin K | [56] | |

| 25 | Dendrocandin L | [56] | |

| 26 | Dendrocandin M | [56] | |

| 27 | Dendrocandin N | [56] | |

| 28 | Dendrocandin O | [56] | |

| 29 | Dendrocandin P | [56] | |

| 30 | Dendrocandin Q | [56] | |

| 31 | 4,4′-Dihydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybibenzyl | 442701 | [56] |

| 32 | 4,4′-Dihydroxy-3,3′,5-trimethoxybibenzyl | 176096 | [56] |

| 33 | 3,4,4′-Trihydroxy-5-methoxybibenzyl | [57] | |

| 34 | Dendromoniliside E | [41] | |

| 35 | Gigantol | 3085362 | [54] |

| Phenols | |||

| 36 | 4-(3,5-Dimethoxyphenethyl) phenol | [57] | |

| 37 | 3-(4-Hydroxyphenethyl)-5-methoxyphenol | [57] | |

| 38 | 5-(3-Hydroxyphenethyl)-2-methoxyphenol | [57] | |

| 39 | 4-(4-Hydroxyphenethyl)-2,6-dimethoxyphenol | [57] | |

| 40 | 4-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxyphenethyl)-2,6-dimethoxyphenol | [57] | |

| Acids | |||

| 41 | p-Hydroxy-coumaric acid | 637542 | [55] |

| 42 | p-Hydroxybenzene propanoic acid | [55] | |

| 43 | Hexadecanoic acid | 985 | [41] |

| 44 | Heptadecanoic acid | 10465 | [41] |

| 45 | Syringic acid | 10742 | [58] |

| 46 | Vanillic acid | 8468 | [58] |

| 47 | p-Hydroxy-phenylpropionic acid | 10394 | [58] |

| 48 | Ferulic acid | 445858 | [58] |

| 49 | 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 135 | [58] |

| Esters | |||

| 50 | p-Hydroxyl-trans-cinnamic acid myricyl ester | [41] | |

| 51 | Trans-ferulic acid octacosyl ester | [41] | |

| 52 | p-Hydroxyl-cis-cinnamic acid myricyl ester | [41] | |

| 53 | Dihydroconiferyl dihydro-p-cumarate | [58] | |

| 54 | Cis-3-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxy-phenyl)-acrylic acid octacosyl ester | [57] | |

| 55 | Trans-3-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxy-phenyl)-acrylic acid octacosyl ester | [57] | |

| 56 | 4-[2-(4-Methoxy-phenyl)-ethyl-6]-oxo-6H-pyran-2-carboxylic acid methyl ester | [57] | |

| Amides | |||

| 57 | N-Trans-feruloyltyramine | 5280537 | [55] |

| 58 | cis-Feruloyl p-hydroxyphenethylamine | [55] | |

| 59 | Trans cinnamyl p-hydroxyphenethylamine | [55] | |

| 60 | N-p-Coumaroyltyramine | 5372945 | [58] |

| 61 | Dihydroferuloyltyramine | 90823368 | [58] |

| 62 | 4-Hydroxy-N-[2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethyl]benzenepropanamide | [58] | |

| Saccharides and glycosides | |||

| 63 | 4-Allyl-2,6-dimethoxy phenyl glycosidase | [55] | |

| 64 | Adenosine | 60961 | [41] |

| 65 | Uridine | 6029 | [41] |

| 66 | Vernine | 46780355 | [41] |

| 67 | Apigenin-7-O-β-D-glucoside | 5280704 | [59] |

| 68 | Icariol-A2-4-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | 6439218 | [59] |

| 69 | (+)-Syringaresinol-O-β-D-pyranglucose | [59] | |

| 70 | Dihydrosyringin | 71720642 | [58] |

| 71 | Vicenin 3 | 44257698 | [55] |

| 72 | Isoschaftoside | 3084995 | [55] |

| 73 | Schaftoside | 442658 | [55] |

| 74 | Vicenin 2 | 442664 | [55] |

| 75 | Apigenin 6-C-α-L-arabinopyranosyl-8-C-β-D-xylopyranoside | [55] | |

| 76 | Apigenin 6-C-β-D-xylopyranosyl-8-C-α-L-arabinopyranoside | [55] | |

| 77 | Vincenin 1 | 44257662 | [55] |

| 78 | 2-Methoxyphenol-O-β-D-apiofuromosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside | [60] | |

| 79 | 3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl-1-O-β-D-apiose-(1→2)-β-D-glucoside | [60] | |

| 80 | Dictamnoside A | 44560015 | [61] |

| 81 | Leonuriside A | 14237626 | [60] |

| 82 | (1′R)-1′-(4-Hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxylphenyl) propan-1′-ol 4-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | [60] | |

| 83 | Syringaresinol-4,4′-O-bis-β-D-glucoside | [60] | |

| 84 | (+)-Syringaresinol-4-β-D-monoglucoside | [60] | |

| 85 | (+)-Lyoniresinol-3a-O-β-glucopyranoside | [60] | |

| 86 | 3,5-Dimethoxy-4-hydroxylphenyl-1-O-β-D-pyranglucose | [59] | |

| 87 | 7-Methoxycoumarin-6-O-β-D-pyranglucose | [59] | |

| 88 | Sucrose | 5988 | [41] |

| Essential oils | |||

| 89 | Methyl acetate | 6584 | [44] |

| 90 | Carbon disulfide | 6348 | [44] |

| 91 | Hexane | 8058 | [44] |

| 92 | Ethyl acetate | 8857 | [44] |

| 93 | 2-Methyl-propanol | 6560 | [44] |

| 94 | 3-Methyl-butanal | 11552 | [44] |

| 95 | 2-Methyl-butanal | 7284 | [44] |

| 96 | 2-Pentanone | 7895 | [44] |

| 97 | Pentanal | 8063 | [44] |

| 98 | 3-Pentanone | 7288 | [44] |

| 99 | 3-Methyl-1-butanol | 31260 | [44] |

| 100 | 2-Methyl-1-butanol | 8723 | [44] |

| 101 | 2-Methyl-3-pentanone | 11265 | [44] |

| 102 | 1-Pentanol | 6276 | [44] |

| 103 | (Z)-3-Hexanone | [44] | |

| 104 | 2-Hexanone | 11583 | [44] |

| 105 | Hexanal | 6184 | [44] |

| 106 | (E)-2-Hexenal | 5281168 | [44] |

| 107 | (E)-3-Hexanol | [44] | |

| 108 | (Z)-3-Hexenol | [44] | |

| 109 | 1-Hexanol | 8103 | [44] |

| 110 | Styrene | 7501 | [44] |

| 111 | (E)-2-Heptenal | 5283316 | [44] |

| 112 | Benzaldehyde | 240 | [44] |

| 113 | 1-Heptanol | 8129 | [44] |

| 114 | 1-Octen-3-one | 61346 | [44] |

| 115 | 1-Octen-3-ol | 18827 | [44] |

| 116 | 6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-one | 9862 | [44] |

| 117 | 2-Pentyl-furan | 19602 | [44] |

| 118 | Decane | 15600 | [44] |

| 119 | Octanal | 454 | [44] |

| 120 | (Z)-3-Hexenyl acetate | 5363388 | [44] |

| 121 | Hexyl acetate | 8908 | [44] |

| 122 | p-Cymene | 7463 | [44] |

| 123 | Limonene | 22311 | [44] |

| 124 | 3-Octen-2-one | 15475 | [44] |

| 125 | (E)-β-Ocimene | 5281553 | [44] |

| 126 | (E)-2-Octenal | 5283324 | [44] |

| 127 | Ethyl benzyl ether | 10873 | [44] |

| 128 | 1-Phenyl-ethanone | 7410 | [44] |

| 129 | (E)-2-Nonen-1-ol | 5364941 | [44] |

| 130 | 1-Octanol | 957 | [44] |

| 131 | Nonanal | 31289 | [44] |

| 132 | 2-Heptenyl acetate | 85649 | [44] |

| 133 | (E)-2-Nonenal | 5283335 | [44] |

| 134 | Nonenol | 85445514 | [44] |

| 135 | 2-Terpineol | [44] | |

| 136 | Dodecane | 8182 | [44] |

| 137 | 2-Octenyl acetate | [44] | |

| 138 | Decyl aldehyde | 8175 | [44] |

| 139 | Benzylacetone | 17355 | [44] |

| 140 | (E)-2-Decenal | 5283345 | [44] |

| 141 | 1-Dodecanol | 8193 | [44] |

| 142 | Tridecane | 12388 | [44] |

| 143 | α-Cubebene | 86609 | [44] |

| 144 | β-Bourbonene | 62566 | [44] |

| 145 | Tetradecane | 12389 | [44] |

| 146 | α-Cedrene | 442348 | [44] |

| 147 | Zingiberene | 92776 | [44] |

| 148 | Geranyl acetone | 19633 | [44] |

| 149 | 2-Methyl tridecane | [44] | |

| 150 | AR-Curcumene | 92139 | [44] |

| 151 | Pentadecane | 12391 | [44] |

| 152 | β-Bisabolene | 403919 | [44] |

| 153 | (+)-D-Cadinene | 441005 | [44] |

| 154 | 5-Phenyl-decane | [44] | |

| 155 | 4-Phenyl-decane | [44] | |

| 156 | Hexadecane | 11006 | [44] |

| 157 | α-Cedrol | 65575 | [44] |

| 158 | 5-phenyl-undecane | [44] | |

| 159 | 4-phenyl-undecane | [44] | |

| 160 | Heptadecane | 12398 | [44] |

| 161 | Pristane | 15979 | [44] |

| 162 | 6-Phenyl-dodecane | 17629 | [44] |

| 163 | 5-Phenyl-dodecane | 17630 | [44] |

| 164 | 4-Phenyl-dodecane | 17631 | [44] |

| 165 | 6,10,14-Trimethyl-2-pentadecanone | 10408 | [44] |

| 166 | Butyl phthalate | 3026 | [44] |

| 167 | Isobutyl phthalate | 6782 | [44] |

| 168 | Sandaracopimaradiene | 440909 | [44] |

| 169 | Hentriacontanol | 68345 | [62] |

| 170 | Citronellol | 8842 | [55] |

| 171 | Citrusin C | 3084296 | [59] |

| 172 | Coniferyl alcohol | 1549095 | [55] |

| Others | |||

| 173 | 2,6-Dimethoxycyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione | [63] | |

| 174 | (24R)-6-β-Hydroxy-24-ethlcholest-4-en-3-one | [63] | |

| 175 | Dendroflorin | 44418788 | [63] |

| 176 | Friedelin | 91472 | [63] |

| 177 | 3-Ethoxy-5-hydroxy-7-methoxy-1,4-phenanthra-quinone | [63] | |

| 178 | β-sitosterol | 222284 | [62] |

| 179 | 5-Hydroxymethyl furfural | 237332 | [41] |

| 180 | Syringaldehyde | 8655 | [58] |

| 181 | 3-O-Methylgigantol | 10108163 | [54] |

| 182 | Syringaresinol | 332426 | [55] |

| 183 | 5α,8α-Epidioxy-24(R)-methylcholesta-6,22-dien-3β-ol | [63] | |

| 184 | (−)-Secoisolariciresinol | 65373 | [60] |

| 185 | Aduncin | 101316879 | [41] |

| 186 | β-Daucosterol | 5742590 | [62] |

| 187 | (−)-Loliolide | 12311356 | [41] |

| 188 | Naringenin | 932 | [61] |

| 189 | 3′,5,5′,7-Tetrahydroxyflavanone | [61] | |

| 190 | Dihydrogen resveratrol | [41] |

4.1. Polysaccharides

Polysaccharides are the main component in dried Dendrobium officinale. Extraction and quantitative and qualitative analysis are described as follows, and the pharmacological effects of polysaccharides are in Table 3.

Table 3.

The pharmacological effects of Dendrobium officinale.

| Effect | Tested material | In vivo/in vitro | Adm. | Conc. | Observations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatoprotective effect | Arabinose : mannose : glucose : galactose = 1.26 : 4.05 : 32.05 : 3.67 | In vivo | Gavage | 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg | Increased the weight in mice | [64] |

| In vivo | Gavage | 200 mg/kg | Increased liver coefficient in mice | |||

| In vivo | Gavage | 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg | Decreased mice serum ALT, AST, ALP activity, and TBIL levels; increased serum HDL-C; decreased LDL-C levels; accelerated metabolism of serum TG and TC; increased liver ADH, ALDH activities; inhibited mRNA expression of P4502E1, TNF-α, and IL-1β | |||

| Arabinose : mannose : glucose : galactose = 1.26 : 4.05 : 32.05 : 3.67 | In vivo | Gavage | 100 and 200 mg/kg | Increased GR activity and GSH-Px activity in mice | [64] | |

| Original extract solution | In vivo | Gavage | 3 g/kg | Reduced chronic alcoholic liver injured mice's serum ALT, AST, and TC levels | [65] | |

| Original extract solution | In vivo | Gavage | 6 g/kg | Reduced serum TC level in mice | ||

| Tiepifengdou original extract solution | In vivo | Gavage | 0.45, 0.9, and 1.35 g/kg | Reduced serum AST levels in mice | ||

| Original extract solution | In vivo | Gavage | 3 g/kg | Increased acute alcoholic hepatic injured mice's SOD of serum and liver and DSG-Px of liver | [66] | |

| Tiepifengdou original extract solution | In vivo | Gavage | 0.45, 0.90, and 1.35 g/kg | Increased acute alcoholic hepatic injured mice's SOD of serum and liver and DSG-Px of liver | ||

| Original extract solution | In vivo | Gavage | 3 and 6 g/kg | Reduced MDA of serum and liver in mice | ||

| Tiepifengdou original extract solution | In vivo | Gavage | 0.45 and 0.90 g/kg | Reduced MDA of serum and liver in mice | ||

| Original extract solution | In vivo | Gavage | 9 g/kg | Reduced serum MDA in mice | ||

|

| ||||||

| Anticancer effect | Water extraction by alcohol sedimentation, extraction rate (in dry herb): 19.2% | In vivo | Gavage | 10 and 20 g/kg | Increased the level of carbon clearance indexes and NK cells activity of LLC mice (P < 0.05) | [67] |

| In vivo | Gavage | 20 g/kg | Improved the LLC mice's spleen lymphocyte transformation and hemolysin levels (P < 0.05) | |||

| Water extraction by alcohol sedimentation | In vitro | — | 100, 200, and 400 μg/mL | Inhibited the growth of human hepatoma cells (HepG2), human lung cancer cells (A549), and human teratoma stem cells (NCCIT) | [68] | |

| In vitro | — | 200 and 400 μg/mL | Inhibited murine teratoma stem cells (F9) and promoted their apoptosis | |||

| In vitro | — | 100 μg/mL | Promoted the proliferation of mouse spleen cells | |||

| Water extraction and alcohol precipitation | In vivo | Gavage | — | Inhibited the growth transplantation tumor (CNE1 and CNE2) of NPC nude mice | [69] | |

| In vitro | — | 128 and 256 mg/L | Inhibited the proliferation and induced the apoptosis of CNE1 and CNE2 cells; activated caspase-3; declined Bcl-xL, Mcl-1 protein levels | |||

|

| ||||||

| Hypoglycemic effect | DOP: 2-O-acetylglucomannan consisted of Man, Glc, and Ara in the molar ratio of 40.2 : 8.4 : 1.0 | In vivo | Gavage | 200, 100, and 50 mg/kg | Decreased levels of fasting blood glucose (FBG) and glycosylated serum protein (GSP); increased level of serum insulin in alloxan induced diabetic mice; attenuated the occurrence of oxidative stress in the liver and kidney of alloxan-induced diabetic mice (decreased MDA levels; increased GSH concentrations and antioxidative enzyme activities) | [70] |

| Extract, crude drug 1.8 g/g | In vivo | Gavage | 0.125 and 0.25 g/kg | Reduced STZ-DM rats' blood glucose and glucagon levels; enhanced the number of islet β cells; declined the number of islet α cells | [71] | |

| In vivo | Gavage | 0.5 and 1.0 g/kg | Decreased blood glucose and increased liver glycogen content in adrenaline induced hyperglycemia rats | |||

| Total polysaccharide: 43.1%, total flavonoids: 19.6%, crude drug 1 g/mL | In vivo | Gavage | TP (total polysaccharides, 100 mg/kg), TF (total flavonoids, 35 mg/kg), and TE (water extract, 6 g/kg) | Significantly downregulated the phosphorylation of JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) and upregulated the phosphorylation of AKT ser473 in rat | [72] | |

|

| ||||||

| Antifatigue effect | Hot water reflux and cellulase lixiviating extraction | In vivo | Gavage | 1.5 and 4.5 g/kg | Increased mice's glycogen store after exercise fatigue | [73] |

| Hot water reflux and cellulase lixiviating extraction | In vivo | Gavage | 0.75, 1.5, and 4.5 g/kg | Decreased the level of serum urea and lactic acid accumulation; upregulated the expression of CNTF mRNA in mice | ||

| Hot water extraction then filtration | In vivo | Gavage | 0.75 mg/kg | Increased carbon clearance indexes from 0.025 to 0.034 in mice | [74] | |

| In vivo | Gavage | 3 and 6 mg/kg | Extended burden swimming time of mice; reduced serum lactic acids of mice | [74] | ||

|

| ||||||

| Gastric ulcer protective effect | Lyophilization then hot-water extraction, evaporation | In vivo | Gavage | 200 mg/kg | Decreased SD rats' gastric secretion, IL-6, and TNF-α cytokine levels; had 76.6% inhibition of gastric injury rate | [75] |

| Squeezing then filtration | In vivo | Gavage | 0.5 and 2 g/kg | Declined irritable and chemical gastric ulcer model's ulcer indexes in mice | [76] | |

|

| ||||||

| Others | Dry powder | In vivo | Gavage | 1.5 and 3 g/kg | Reduced ApoE−/− mice's TG, TCHOL, LDL-C levels, and expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in serum; reduced areas of atheromatous plaque in aortic valve and arch in ApoE−/− mice; then decreased expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in aortic arch | [77] |

| Aqueous extract | In vivo | Gavage | 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 crude drug g/kg | Extended Stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive (SHR-sp) rats' blood pressure, living days, and survival rate | [78] | |

| Water extraction by alcohol sedimentation; mannose : glucose : galactose : arabinose : xylose : glucuronic acid = 10 : 0.25 : 1.2 : 4.7 : 1.3 : 1.4 | In vivo | — | 20 mg/mL | Inhibited Bax/Bal-2 ratio and caspase-3 expression; decreased expression of cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) and activity of MMP-9 in mice | [79] | |

| Water extraction by alcohol sedimentation; mannose : glucose : galactose : arabinose : xylose : glucuronic acid = 10 : 0.25 : 1.2 : 4.7 : 1.3 : 1.4 | In vitro | — | 0.1, 1.0, and 10 μg/mL | Ameliorated the abnormalities of aquaporin-5 (AQP-5) on A-253 cell | [79] | |

| Water extract and alcohol precipitate, extraction rate: 29.87% | In vivo | Smear | 5.0 g/L | Increased average score and average quality of hair growth of C57BL/6J mice | [80] | |

| in vitro | — | 0.1, 1.0, and 5.0 mg/L | Increased HaCaT cells survival rate and the VEGF mRNA expression level | |||

| Dry power decoction then concentration: traditional decoction or dry power steep in hot water: ultra-fine powder decoction | In vivo | Gavage | — | Increased Shannon index and Brillouin index in mice with constipation and improved their molecular diversity of intestinal Lactobacillus | [81] | |

4.1.1. Extraction

Generally, there are three methods that can isolate crude Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides (DOP): a solvent method (water extraction by alcohol sedimentation), a biological method (enzyme extraction), and a physical method (ultrasonic extraction and microwave extraction). Among the three, the solvent method is most popular. The physical method could be combined with the biological and solvent methods to accelerate the extraction process and promote the efficiency [23].

Since there are lipids, proteins, pigments, and other impurities after the process of separation of polysaccharides, other separation methods, such as ion-exchange chromatography, gel filtration chromatography, and HPLC, are needed to purify the crude polysaccharides [24]. However, polysaccharides are acknowledged as complex biological macromolecules; the ways and sequences of connections of the monosaccharides determine the difficulty of polysaccharides' analyses [25].

4.1.2. Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis

The average content of neutral sugar in desiccated Dendrobium officinale is up to 58.3% [26]. Actually, different production origins, processing methods, growing years, and cultivated or wild and different parts of Dendrobium officinale are all related to polysaccharide content. Research showed that there were various polysaccharide contents of the same species cultivated in Guangdong with different origins from Yunnan, Zhejiang, and other provinces [27]. After drying each with different methods, DOP content was arranged as follows: hot air drying > vacuum drying > vacuum freeze drying > natural drying [28]. In addition, amounts of polysaccharide were greater in biennial Dendrobium officinale than annual or triennial ones [29], while the wild type contained more content compared to the cultivated type [30]. Research showed that polysaccharides distributing in different parts of Dendrobium officinale varied: middle stem > upper stem > lower stem > roots [31]. Therefore, accurate determination of polysaccharide content is of great significance.

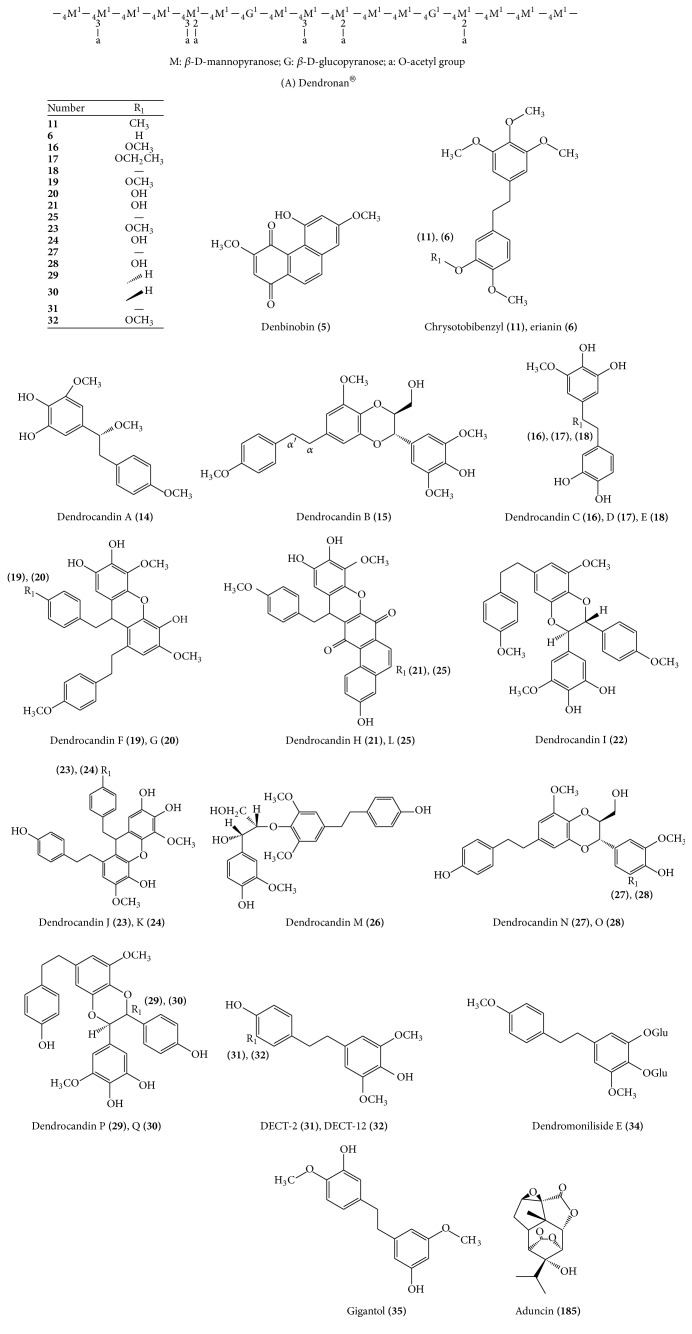

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer (FT-IR), Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS), and 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopies have been used to analyze the types of monosaccharide residues and the linkage sites of glycosidic bonds [32]. However, the research of polysaccharide's ratio of mannose to glucose, the existence of branches, and the substitution position of o-acetyl groups was inconsistent [33]. What is more, polysaccharides' pharmacological activities are strongly linked to the composition and content of their monosaccharides [26]. Therefore, further methods to explore the advanced structures and structure-activity relationships of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides need to be established. Research showed that O-acetyl-glucomannan, Dendronan® (Figure 2, A), from Dendrobium officinale [34] has been isolated and was affirmed immunomodulatory activity in vitro [35] and in vivo [36], as well as improvement in colonic health of mice [37].

Figure 2.

Some chemical structure of compounds isolated form Dendrobium officinale which have good potentials.

4.2. Phenanthrenes

From Dendrobium officinale, nine phenanthrenes (1–9) were isolated. Dendrobium officinale contains a kind of bibenzyl and a kind of phenanthrene identified in D. chrysotoxum before: chrysotobibenzyl (11) and erianin (6). Both chrysotobibenzyl and erianin have antitumor effects. Erianin significantly inhibited the proliferation of HepG2 and Huh7 (human hepatoma cell lines) in vitro [38] and also prevented angiogenesis in human hepatoma Be17402 and human melanoma A375 in vivo [39]. IC50 of P388 murine leukemia cell treated by erianin in MTT assay was 0.11 μM [40].

4.3. Bibenzyls

Bibenzyls 10–35 were isolated from the stems of Dendrobium officinale. Among these compounds, 17 bibenzyls named Dendrocandins A–Q (14–30) (Figure 2) were extracted by Li et al. from 2008 to 2014. Next, DCET-2 (31) could inhibit the proliferation of A2780 (human ovarian cancer cell line) cells, and DCET-12 (32) inhibited BGC-823 (human gastric cancer cell lines) and A2780 cells [41]. DCET-18 (35) also inhibited the migratory behavior and induced the apoptosis of non-small-cell lung cancer cells (human NCI-H460 cells) [42].

4.4. Saccharides and Glycosides

In the last few decades, at least 26 saccharides and glycosides have been found from Dendrobium officinale, (compounds 63–88). Among them, Dictamnoside A (80) showed immunomodulatory activity in mouse splenocyte assessed as stimulation of proliferation at 10 umole/L after 44 hours by MTT assay in the presence of Concanavalin A (ConA) [43].

4.5. Essential Oils

Compounds 89–172, isolated from Dendrobium officinale, comprise essential oils. The content of limonene (123) in the stem is 9.15% for the second; limonene is most abundant in the leaves, accounting for 38% [44]. Limonene contains anticancer properties with effects on multiple cellular targets in preclinical models [45]. Dendrobium officinale containing a high content of (E)-2-hexenal (106) shows bactericidal activity against Pseudococcus viburni, Pseudococcus affinis, Bemisia sp., and Frankliniella occidentalis [46].

4.6. Alkaloids

Alkaloids are the earliest chemical compounds isolated from Dendrobium genus. Dendrobine, a kind of Dendrobium alkaloid accounting for 0.52%, was isolated initially in 1932 [47]. It was later proved to be the special content of D. nobile [48]. As reported, the alkaloid in Dendrobium officinale belongs to the terpenoid indole alkaloid (TIA) class, with its total content measured at approximately 0.02% [49]. However, the isolation and identification of one single kind of alkaloid have been rarely reported.

4.7. Others

Excepting ingredients above, phenols (36–40), acids (41–49), esters (50–56), amides (57–62), and other chemical constituents (173–190) were detected in Dendrobium officinale (Table 2), while their pharmacological effects remain to be excavated in the future.

5. Pharmacological Effects of Dendrobium officinale

Recently, more and more pharmacological actions of Dendrobium officinale were reported, such as hepatoprotective effect, anticancer effect, hypoglycemic effect, antifatigue effect, and gastric ulcer protective effect (Table 3).

5.1. Hepatoprotective Effect

The hepatoprotective capacity of Dendrobium officinale is always related to its antioxidant ability, especially in acute or chronic alcoholic liver injury. Research showed that Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides (DOP) accelerated the metabolism of serum TG and TC, while increased liver ADH and ALDH activities, which recovered disorders of lipid metabolism and accelerated excretion of alcohol and its metabolites [64]. In addition, ALT, AST, and TC of Dendrobium officinale treated mice models with chronic alcoholic liver injury were elevated compared to the normal groups [65]. Besides, compared to the model group of mice with acute alcoholic hepatic injury, fresh Dendrobium officinale and tiepifengdou groups could increase the SOD and reduce MDA of serum and liver tissue [66].

5.2. Anticancer Effect

The anticancer activity of Dendrobium officinale extract has been studied and proved, such as anti-HelaS3, anti-HepG2, and anti-HCT-116 in vitro, as well as anti-CNEl and CNE2 in vivo and in vitro [69]. Besides, DOP has manifested anticancer effects in mice with Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC). Its tumor inhibition rate was 8.5%–18.3% (P > 0.05); meanwhile, LLC mice spleen lymphocyte transformation and hemolysin levels (P < 0.05) were improved [67]. In cellular experiments, Liu's morphological analysis showed that DOP can inhibit the growth of human hepatoma cells (HepG2), human lung cancer cells (A549), human teratoma stem cells (NCCIT), and murine teratoma stem cells (F9) and promoted the proliferation of mouse spleen cells in vitro [68]. Research showed that two DOP fractions, DOP-1 and DOP-2, promoted splenocyte proliferation, enhanced NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity, and increased the phagocytosis and nitric oxide production of macrophages significantly (P < 0.05) [82]. Therefore, the anticancer effect of Dendrobium officinale may be accompanied by the activity of improving immune system.

5.3. Hypoglycemic Effect

Hypoglycemic activity, another important property of Dendrobium officinale, has been studied a lot. Oral administration of DOP decreased levels of fasting blood glucose (FBG) and glycosylated serum protein (GSP) and increased level of serum insulin in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. In addition, DOP attenuated the occurrence of oxidative stress in the liver and kidney of alloxan-induced diabetic mice by decreasing MDA levels, increasing GSH concentrations and antioxidative enzyme activities [70]. Therefore, DOP may regulate blood sugar levels through blood-lipid balance effects and antioxidative damage effects of liver and kidney.

Dendrobium officinale exhibited a significant hypoglycemic effect in adrenaline hyperglycemia mice and streptozotocin-diabetic (STZ-DM) rats [71]. In addition, TP (total polysaccharides, 100 mg/kg), TF (total flavonoids, 35 mg/kg), and TE (water extract, 6 g/kg) groups of Dendrobium officinale significantly downregulated the phosphorylation of JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) and upregulated the phosphorylation of AKT ser473 compared with the normal control group, which indicates that effective extracts of Dendrobium officinale have the effects of inhibiting JNK phosphorylation and promoting AKT ser473 phosphorylation [72].

5.4. Antifatigue Effect

The antifatigue effect of Dendrobium officinale was illustrated in vivo, when compared with the control groups; Dendrobium officinale could increase the glycogen stored in mice after exercise and decrease the level of serum urea and lactic acid accumulation (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01). In addition, it could upregulate the expression of ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) mRNA (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01) [73]. In addition, compared to the control groups, Dendrobium officinale significantly increased carbon clearance indexes and burden swimming time and reduced the serum lactic acids [74]. In general, antifatigue effect of Dendrobium officinal was linked to the TCM use about enriching consumptive diseases, but its mechanism needs to be further clarified.

5.5. Gastric Ulcer Protective Effect

Research showed that Dendrobium officinale had a preventive effect of gastric injury caused by 60% ethanol-hydrochloric acid solution (ethanol was dissolved in 150 mM hydrochloric acid). Intragastric administration of SD rats with 200 mg/kg of Dendrobium officinale for two weeks decreased gastric secretion, IL-6 and TNF-α cytokine levels compared with the lower dose groups and the control groups. This concentration (200 mg/kg) had the strongest inhibitory effect of gastric injury (76.6% inhibition of gastric injury rate) [75]. After the successful establishment of the irritable gastric ulcer model (induced by cold water immersion) and chemical gastric ulcer model (indometacin-induced, 40 mg/kg, gavage) the ulcer index was calculated by Guth standard scoring method. Freshly squeezed Dendrobium officinale juice (containing crude drugs 0.5, 2 g/kg) showed significant declining irritable and chemical gastric ulcer model ulcer indexes (P < 0.01) [76]. However, gastric ulcer is a chronic disease, the security of long-term administration of Dendrobium officinale still uncertain.

5.6. Others

It is found that Dendrobium officinale had hypolipidemic and hypotensive effects. The fine powder solution of Dendrobium officinale (1.5, 3 g/kg) can reduce the levels of TG, TCHOL, and LDL-C in serum significantly and reduce the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in ApoE−/− mice. In addition, it could reduce areas of atheromatous plaque in aortic valve and arch in ApoE−/− mice and then decrease the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in aortic arch [77]. Research showed that stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive (SHR-sp) rats' living days and survival rates were extended by DOP, and hypotensive effect of DOP was significantly better than the nonpolysaccharide ingredients of Dendrobium officinale [78].

Moreover, Dendrobium officinale was used to treat Sjögren's syndrome (SS) with dry eyes and mouth due to impaired lacrimal and salivary glands [80]. Research showed that DOP could suppress the progressive lymphocytes infiltration and apoptosis and balance the disorders of proinflammatory cytokines in the submandibular gland (SG) in vivo. Further, DOP ameliorated the abnormalities of aquaporin-5 (AQP-5) that was supported by in vitro study on A-253 cell line and maintained its function of saliva secretion [79].

Meanwhile, research showed that the DOP group demonstrated higher average scores and an improved average quality of hair growth of C57BL/6J mice (5.0 g/L, the solution was ultra-pure water, each 0.2 mL, smeared for 21 d), compared with the control group. Besides, DOP significantly increased HaCaT cells survival rate and the VEGF mRNA expression levels compared with the control group [80].

Besides, the Dendrobium officinale had an obvious effect on the molecular diversity of intestinal Lactobacillus in mice model (irregular diet for 8 d after gavage of folium senna water decoction for 7 d) with constipation resulting from spleen deficiency (TCM syndrome type) [81]. Dendrobium officinale also can regulate the digestive function in carbon-induced constipated mice models [83].

6. The Toxicology of Dendrobium officinale

After acute toxicity test, genetic toxicity test (Ames test, micronucleus test of bone marrow, and sperm shape abnormality test in mice) and 90-day feeding test in rats, the results showed that protocorms of Dendrobium officinale were without toxicity, genetic toxicity and mutagenicity within the scope of the test dose [84]. Furthermore, the 15% decoction of Dendrobium officinale was used for mice sperm malformation test, Ames test, and micronucleus test of bone marrow in mice, and all test results were negative. In addition, the acute oral toxicity test showed that the highest dose was 10 g/kg b.w. which belonged to the actual nontoxic category [85]. However, in the pesticide safety aspect, the Dendrobium officinale still need more stringent quality control [86].

7. The Industrialization of Dendrobium officinale

Due to the special trophic mode, seed germination of Dendrobium officinale needs the root symbiotic bacteria [87, 88]; the reproduction of wild Dendrobium officinale is limited with low natural reproductive rates. The past three decades witnessed excess herb-gathering of Dendrobium officinale destroying much of the wild habitat resource in China [89]. In 1987, Dendrobium officinale was on the list of national third-level rare and endangered plants [90]. However, artificial cultivation based on tissue culture technology significantly prompted the yield of Dendrobium officinale.

Recently, increased awareness of the tonic therapeutic effect of Dendrobium officinale has increased the demand and as a consequence the price [91]. However, the high-profit margin of Dendrobium officinale has already led to an increase in the market for counterfeits and adulterants [92] mainly by other confusable species of Dendrobium [91]. The appearance of Dendrobium officinale and other species of Dendrobium is very similar, especially after processing into “tiepifengdou”; it is difficult to distinguish them through morphological identification [93]. It is apparent that Dendrobium officinale germplasm resources' separation and purification determine its characters and quality [94]. In terms of microscopic identification, Dendrobium officinale could be identified by vascular bundle sheath observed under the fluorescence microscopy and the distribution of raphides under normal light microscopy [95]. In addition, the taxonomy, phylogeny, and breeding of Dendrobium species have made great progress as the advance of molecular markers in the past two decades [96].

Under such circumstances, pharmacognosy [97], DNA molecule marker technologies including Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (AFLP) [98], Inter Simple Sequence Repeat (ISSR) [99], Start codon targeted (SCoT) and target region amplification polymorphism (TRAP) [100], and sequence related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) analysis [101], and so on have been applied to identify Dendrobium officinale from other Dendrobium species. Further, Yunnan province has completed Dendrobium officinale fine gene map and found more than 48,200 protein-coding genes [102]. Therefore, the identification of Dendrobium officinale is more precise due to the gene technology, but genetic fingerprints are difficult to evaluate the quality, so the gene technology combining with the physical and chemical identification is necessary.

In recent years, the development of Dendrobium officinale health care products is promising [15]. Many related patented products are being registered or have been authorized, including Dendrobium officinale ingredients such as antiaging compounds [103], lactobacillus drink [104], antiasthenopia eye ointment [105], immunoenhancement compounds [106], hypotensive extractive [107], and hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic compounds [108]. Some of these patents have been put into production like “tiepifengdou,” one of the most famous processed products of Dendrobium officinale [101]. However, there are few medicines of Dendrobium officinale [109] besides tiepishihu of Chinese materia medica in TCM.

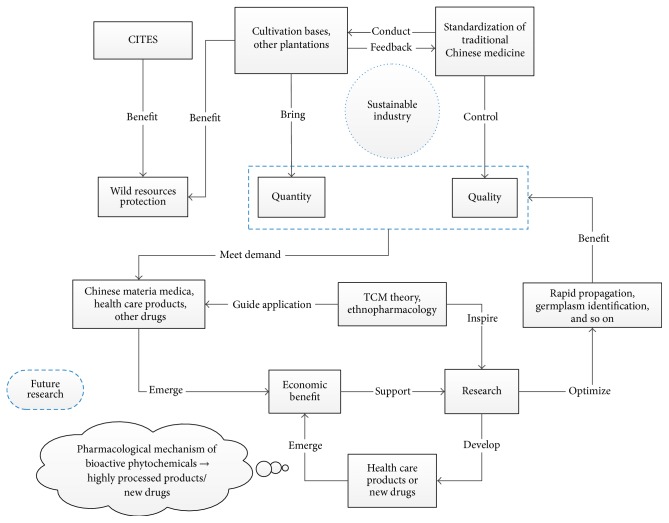

In summary, the TCM theory and ethnopharmacology could inspire modern researches committed to yield and quality control of Dendrobium officinale, while some standards or laws (such as ISO/TC 249 and CITES) regulated artificial cultivation and protected wildlife resources. Finally, industrialization will drive further researches and is conducive to develop deep-processing products, especially the insufficient new drugs, which will also promote the industrialization and form a virtuous circle simultaneously (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The industry and research status quo and future perspectives.

8. Conclusion

Dendrobium officinale, one of the most famous species of Dendrobium, has long been regarded as precious herbs and health foods applied in TCM and in folk. In this paper, the ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and industrialization of Dendrobium officinale were summarized. In recent years, the interest of exploring ethnopharmacology-based bioactive constituents of Dendrobium officinale has increased considerably. Rapid propagation technology has gradually matured, so yield is no longer the bottleneck of Dendrobium officinale development. In addition, the confusable identification and uneven quality still exist, and better quality control standards under modern researches are necessary.

Consequently, the following points deserve further investigation. (1) Polysaccharides are the main composition in Dendrobium officinale with numerous pharmacological researches, but investigation related to its structure-activity relationships remains scant. (2) The pharmacological effects of Dendrobium officinale crude extract and polysaccharide were similar, indicating whether other active ingredients were lost during extraction. (3) There is no enough systemic data about toxicology of Dendrobium officinale. (4) How does TCM theory play a role in Dendrobium officinale further in-depth development as theoretical guidance and inspiration source.

Over all, further studies at the molecular level are needed to promote the exploration of chemical compositions and pharmacological mechanisms. In addition, the industrialization of Dendrobium officinale not only protected the germplasm resources but also attracted a large quantity of researches in China, which makes the innovation of Dendrobium officinale novel drug and product a promising prospect.

Acknowledgments

This work was financed by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, no. 81573700), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (no. LY16H280004), Industrial Technology Innovation Strategic Alliance of Zhejiang, China (no. 2010LM304), and Science and Technology Program of Zhejiang, China (no. 2012R10044-03).

Abbreviations

- ADH:

Antidiuretic hormone

- ALDH:

Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase

- b.w.:

Body weight

- ChP:

Chinese Pharmacopoeia

- CITES:

Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

- ConA:

Concanavalin A

- D.:

Dendrobium

- DOP:

Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides

- GC:

Gas Chromatography

- GSH-PX:

Glutathione peroxidase

- HDL:

High-density lipoprotein

- HPLC:

High Performance Liquid Chromatography

- LLC:

Lewis lung carcinoma

- MDA:

Malondialdehyde

- MMP:

Matrix metalloproteinase

- MS:

Mass Spectrometer

- MTT:

3-(4,5-Dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2-H-tetrazolium bromide

- NMR:

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

- SOD:

Superoxide dismutase

- SS:

Sjögren's syndrome

- TC:

Total cholesterol

- TCM:

Traditional Chinese medicine

- TG:

Triglyceride

- VEGF:

Vascular endothelial growth factor.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Li X. X. The Phylogenetic of Chinese Dendrobium and Protection and Genetics Research on Dendrobium Officinale. Nanjing, China: Nanjing Normal University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lü G. Y., Yan M. Q., Chen S. H. Review of pharmacological activities of Dendrobium officinale based on traditional functions. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 2013;38(4):489–493. doi: 10.4268/cjcmm20130405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luo Q. L., Tang Z. H., Zhang X. F., et al. Chemical properties and antioxidant activity of a water-soluble polysaccharide from Dendrobium officinale. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2016;89:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.04.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He T. B., Huang Y. P., Yang L., et al. Structural characterization and immunomodulating activity of polysaccharide from Dendrobium officinale. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2016;83:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang M. Q., Huang B. H., Cai T. Y., Liu Q. L., Li D., Chen A. Z. Extraction, isolation and analysis of Dendrobium officinale's polysaccharides. Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs. 1994;3:128–129. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu H., Qu Y., Chen S. Efficacy of Golden Dendrobium tablets on clearing and smoothing laryngopharynx. Yunnan University Natural Sciences. 2005;27(5):p. 440. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu H., Wang Z., Ding X., Zhou K., Xu L. Differentiation of Dendrobium species used as “Huangcao Shihu” by rDNA ITS sequence analysis. Planta Medica. 2006;72(1):89–92. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-916228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam Y., Ng T. B., Yao R. M., et al. Evaluation of chemical constituents and important mechanism of pharmacological biology in Dendrobium plants. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2015;2015:25. doi: 10.1155/2015/841752.841752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu J., Zhao W. M., Qian Z. M., Guan J., Li S. P. Fast determination of five components of coumarin, alkaloids and bibenzyls in Dendrobium spp. using pressurized liquid extraction and ultra-performance liquid chromatography. Journal of Separation Science. 2010;33(11):1580–1586. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin X., Huang L. (2352) Proposal to conserve the name Dendrobium officinale against D. stricklandianum, D. tosaense, and D. pere-fauriei (Orchidaceae) Taxon. 2015;64(2):385–386. doi: 10.12705/642.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiang X. G., Schuiteman A., Li D. Z., et al. Molecular systematics of Dendrobium (Orchidaceae, Dendrobieae) from mainland Asia based on plastid and nuclear sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2013;69(3):950–960. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimura K., Migo H. New Species of Dendrobium from the Chinese Drug (Shi-hu) Shanghai, China: Shanghai Science Institute; 1936. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hao P., Guo L., Xu L., et al. Study on HPLC fingerprint in different species of Dendrobii Caulis. Pharmacy and Clinics of Chinese Materia Medica. 2013;4:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai G. X., Li J., Li S. X., Huang D., Zhao X. B. Applications of dendrobium officinale in ancient and modern times. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine University of Hunan. 2011;31(5):77–81. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen S. H., Yan M. Q., Lü G. Y., Liu X. Development of dendrobium officinale kimura et migo related health foods. Chinese Pharmaceutical Journal. 2013;48(19):1625–1628. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang M. J., Yu P., Lu L. D., Lü Z. M., Chen X. X. Effects of dendrobium candicum capsules on immune responses in mouse. Jiangsu Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;19(4):11–13. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chinese Pharmacopoeia Committee. Chinese Pharmacopoeia. Beijing, China: China Medical Science; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chinese Pharmacopoeia Committee. Chinese Pharmacopoeia. Beijing, China: China Medical Science Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J., Wang B. C. Fresh Dendrobium officinale clinic applications. Zhejiang Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2012;47(11):841–842. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang C., Wang D., Sun L., Wei L. Effects of exogenous salicylic acid on the physiological characteristics of dendrobium officinale under chilling stress. Plant Growth Regulation. 2016;79(2):199–208. doi: 10.1007/s10725-015-0125-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hou S. Z., Liang C. Y., Liu H. Z., et al. Dendrobium officinale prevents early complications in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2016;2016:10. doi: 10.1155/2016/6385850.6385850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song T. H., Chen X. X., Tang S. C. W., et al. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides ameliorated pulmonary function while inhibiting mucin-5AC and stimulating aquaporin-5 expression. Journal of Functional Foods. 2016;21:359–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2015.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye Y. Y. Ultrasonic extraction research on polysaccharides of Dendrobium officinale. Journal of Chinese Medicinal Materials. 2009;32(4):617–620. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bao S. H., Cha X. Q., Hao J., Luo J. P. Studies on antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from dendrobium candidum in vitro. Hefei University of Technology. 2009;30(21):123–127. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie M. Y., Nie S. P. Research progress of natural polysaccharides' structure and function. Journal of Chinese Institute of Food Science and Technology. 2010;10(2):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xing X., Cui S. W., Nie S., Phillips G. O., Goff H. D., Wang Q. Study on Dendrobium officinale O-acetyl-glucomannan (Dendronan®): part I. Extraction, purification, and partial structural characterization. Bioactive Carbohydrates and Dietary Fibre. 2014;4(1):74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bcdf.2014.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu Q. F., Wang P. P., Chen J. N., Huang S. Comparative Study on Polysaccharides Content in Stem and Leaf of Iron Stone Dendrobium Fresh Product from difierent producing place. Journal of Medical Research. 2013;42(9):55–58. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xin M., Zhang E. Z., Li N., et al. Effects of different drying methods on polysaccharides and dendrobine from Dendrobium candidum. Journal of Southern Agriculture. 2013;44(8):1347–1350. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu Y., Si J. P., Guo B. L., He B. W., Zhang A. L. The content variation regularity of cultivated Dendrobium candidum polysaccharides. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 2010;35(4):427–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shang X. Y. Distribution of polysaccharides from different sources and in different parts of Dendrobium officinale. Chinese Journal of Modern Drug Application. 2010;4(13):104–105. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheng J. R., Li Z. H., Yi Y. B., Li J. J. Advances in the study of polysaccharide from Dendrobium officinale. Journal of Guangxi Academy of Sciences. 2011;27(4):338–340. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Q., Xie Y., Su J., Ye Q., Jia Z. Isolation and structural characterization of a neutral polysaccharide from the stems of Dendrobium densiflorum. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2012;50(5):1207–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xing X., Cui S. W., Nie S., Phillips G. O., Douglas Goff H., Wang Q. A review of isolation process, structural characteristics, and bioactivities of water-soluble polysaccharides from Dendrobium plants. Bioactive Carbohydrates and Dietary Fibre. 2013;1(2):131–147. doi: 10.1016/j.bcdf.2013.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xing X., Cui S. W., Nie S., Phillips G. O., Goff H. D., Wang Q. Study on Dendrobium officinale O-acetyl-glucomannan (Dendronan®): part II. Fine structures of O-acetylated residues. Carbohydrate polymers. 2015;117:422–433. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.08.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai H. L., Huang X. J., Nie S. P., Xie M. Y., Phillips G. O., Cui S. W. Study on Dendrobium officinale O-acetyl-glucomannan (Dendronan®): Part III-Immunomodulatory activity in vitro. Bioactive Carbohydrates and Dietary Fibre. 2015;5(2):99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.bcdf.2014.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang X., Nie S., Cai H., et al. Study on Dendrobium officinale O-acetyl-glucomannan (Dendronan®): part VI. Protective effects against oxidative stress in immunosuppressed mice. Food Research International. 2015;72:168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2015.01.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang G. Y., Nie S. P., Huang X. J., et al. Study on Dendrobium officinale O-Acetyl-glucomannan (Dendronan). 7. Improving effects on colonic health of mice. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2015;64(12):2485–2491. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b03117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Su P. Research on the Molecular Mechanism of Erianin Anti-Hepatoma Effect. Beijing, China: University of Chinese Academy of Sciences; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gong Y. Q. Mechanisms of Erianin Anti-Tumor Angiogenesis. Nanjing, China: China Pharmaceutical University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barbosa E. G., Bega L. A. S., Beatriz A., et al. A diaryl sulfide, sulfoxide, and sulfone bearing structural similarities to combretastatin A-4. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;44(6):2685–2688. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y., Wang C. L., Wang F. F., et al. Chemical constituents of Dendrobium candidum. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 2010;35(13):1715–1719. doi: 10.4268/cjcmm20101314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Charoenrungruang S., Chanvorachote P., Sritularak B., Pongrakhananon V. Gigantol, a bibenzyl from Dendrobium draconis, inhibits the migratory behavior of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Journal of Natural Products. 2014;77(6):1359–1366. doi: 10.1021/np500015v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang J., Xuan L. J., Xu Y. M., Zhang J. S. Seven new sesquiterpene glycosides from the root bark of Dictamnus dasycarpus. Journal of Natural Products. 2001;64(7):935–938. doi: 10.1021/np000567t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shao J. M., Wang D. P., Zhang Y. P., Tang H. Y., Tan Y. T., Li W. Analysis on chemical constituents of volatile oil from stem and leaf of Dendrobium officinale by GC-MS. Guizhou Agricultural Sciences. 2014;42(4):190–193. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller J. A., Pappan K., Thompson P. A., et al. Plasma metabolomic profiles of breast cancer patients after short-term limonene intervention. Cancer Prevention Research. 2015;8(1):86–93. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hammond D. G., Rangel S., Kubo I. Volatile aldehydes are promising broad-spectrum postharvest insecticides. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2000;48(9):4410–4417. doi: 10.1021/jf000233+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suzuki S. K. Study on Chinese Flickingeria alkaloids (Dendrobium Alkaloids research. Pharmaceutical Journal. 1932;52(12):1049–1060. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li S., Wang C. L., Guo S. X. Determination of dendrobin in dendrobium nobile by HPLC analysis. Chinese Pharmaceutical Journal. 2009;44(4):252–254. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo X., Li Y., Li C., et al. Analysis of the Dendrobium officinale transcriptome reveals putative alkaloid biosynthetic genes and genetic markers. Gene. 2013;527(1):131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Asahina H., Shinozaki J. K., Masuda K., Morimitsu Y., Satake M. Identification of medicinal Dendrobium species by phylogenetic analyses using matK and rbcL sequences. Journal of Natural Medicines. 2010;64(2):133–138. doi: 10.1007/s11418-009-0379-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuan Z. Q., Zhang J. Y., Liu T. Phylogenetic relationship of China Dendrobium species based on the sequence of the internal transcribed spacer of ribosomal DNA. Biologia Plantarum. 2009;53(1):155–158. doi: 10.1007/s10535-009-0024-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li R. S., Yang X., He P., Gan N. Studies on phenanthrene constituents from stems of Dendrobium candidum. Journal of Chinese Medicinal Materials. 2009;32(2):220–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu Q., Chen S. H., Lü G. Y. Pharmacological research progress of the three constituents of different Dendrobium. Asia-Pacific Traditional Medicine. 2010;6(4):115–118. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li Y., Wang C. L., Guo S. X., Yang J. S., Xiao P. G. Two new compounds from Dendrobium candidum. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2008;56(10):1477–1479. doi: 10.1248/cpb.56.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guan H. J. Chemical Composition and Fingerprints of Dendrobium Officinale. Shenyang, China: Shenyang Pharmaceutical University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li Y. Study on the Chemical Constituents of Dendrobium officinale. Beijing, China: Chinese Peking Union Medical College; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang L. The Chemical Composition and Biological Activity of Dendrobium Officinale and Dendrobium Devonianum. Anhui, China: Anhui University of Chinese Medicine; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Y., Wang C. L., Wang F. F., et al. Phenolic components and flavanones from Dendrobium candidum. Chinese Pharmaceutical Journal. 2010;13:975–979. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wei Z. Y., Lu J. J., Jin C. S., Xia H. Chemical constituents from n-butanol extracts of Dendrobium officinale. Modern Chinese Medicine. 2013;15(12):1042–1045. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang F. F., Li Y., Dong H. L., Guo S. X., Wang C. L., Yang J. S. A new compound from Dendrobium candidum. Chinese Pharmaceutical Journal. 2010;45(12):898–902. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li J., Li S. X., Huang D., Zhao X. B., Cai G. X. Advances in the of resources, constituents and pharmacological effects of Dendrobium officinale. Science & Technology Review. 2011;29(18):74–79. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kuang J. W. Studies on the Chemical Constituents from Lycoris Radiata. and Dendrobium candidum. Central South University, Hunan; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang H. Studies on Chemical Components of Dendrobium Chrysotoxum and D. Candidum. Nanjing, China: China Pharmaceutical University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li S. L. Comparison of Intervention Effects of Polysaccharides from Six Dendrobium Species on Alcoholic Liver Injury. Anhui, China: Hefei University of Technology; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lü G. Y., Chen S. H., Zhang L. D., et al. Dendrobium officinale effect on two kinds of serum transaminases and cholesterol of mice model with chronic alcoholic liver injury. Chinese Journal of Experimental Traditional Medical Formulae. 2010;16(6):192–193. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tang X. H., Chen S. H., Lü G. Y., Su J., Huang M. C. Effects of Dendrobium Candidum on SOD, MDA and GSH-Px in mice model of acute alcoholic hepatic injury. Zhejiang Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2010;45(5):369–370. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ge Y. H., Wang J., Yang F., Dai G. H., Tong Y. L. Effects of fresh Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides on immune function in mice with Lewis lung cancer. Zhejiang Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2014;49(4):277–279. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu Y. J. Effect of Dendrobium officinale Polysaccharides on Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells and Study on its Anti-Tumor and Immune Activity. Zhejiang University of Technology Zhejiang; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Deng P. Studies on the Curing of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma (NPC) with Officinal Dendrobium Stem. Guangxi, China: Guangxi Medical University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pan L. H., Li X. F., Wang M. N., et al. Comparison of hypoglycemic and antioxidative effects of polysaccharides from four different dendrobium species. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2014;64:420–427. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu H. S., Xu J. H., Chen L. Z., Sun J. J. Studies on anti-hyperglycemic effect and its mechanism of Dendrobium candidum. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 2004;29(2):160–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chang H. L. Effect of Dendrobium officinale on JNK, AKT protein phosphorylation expression in islet tissue of type 2 diabetic rats. Chinese Pharmaceutical Affairs. 2015;29(1):54–57. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tang H. Q., Chen H., Wei Y., Lu L. Effects of Dendrobium officinale on energy metabolism and expression of CNTF mRNA in athletic fatigue mice. Chinese Journal of Experimental Traditional Medical Formulae. 2014;20(15):164–167. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Feng Y., Huang M. K., Ye J. B., Le N., Zhong W. G. The lowest doses of Dendrobium officinale for improving sports ability, anti-fatigue and immune ability of mice. Journal of Southern Agriculture. 2014;45(6):1089–1093. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Feng X., Zhao X. Prevention effect of Dendrobium officinale aqueous extract to SD rats with gastric injury. Jiangsu Agricultural Sciences. 2013;41(7):294–296. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liang C. Y., Li H. B., Hou S. Z., Zhang J., Huang S., Lai X. P. Dendrobium officinale hepatic protection and anti-ulcerative effects. World Science and Technology-Modernization of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Materia Medica. 2013;15(2):234–237. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li Y. M., Wu P., Xie X. J., Yao H. L., Song L. P., Liao D. F. Effects of Dendrobii officinalis caulis on serum lipid, TNF-α and IL-6 in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Chinese Journal of Experimental Traditional Medical Formulae. 2013;19(18):270–274. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wu R. Z., Yang B. X., Li Y. P., et al. Experimental study of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides on anti-hypertensive-stroke effects of SHR-sp mice. Chinese Journal of Traditional Medical Science and Technology. 2011;18(3):204–210. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lin X., Shaw P. C., Sze S. C. W., Tong Y., Zhang Y. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides ameliorate the abnormality of aquaporin 5, pro-inflammatory cytokines and inhibit apoptosis in the experimental Sjögren's syndrome mice. International Immunopharmacology. 2011;11(12):2025–2032. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen J., Qi H., Li J. B., et al. Experimental study on Dendrobium candidum polysaccharides on promotion of hair growth. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 2014;39(2):291–295. doi: 10.4268/cjcmm20140225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhao X. B., Xie X. J., Wu W. J., et al. Effect of ultra-micro powder Dendrobium officinale on the molecular diversity of intestinal Lactobacillus in mice with spleen-deficiency constipation. Microbiology. 2014;41(9):1764–1770. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xia L., Liu X., Guo H., Zhang H., Zhu J., Ren F. Partial characterization and immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharides from the stem of Dendrobium officinale (Tiepishihu) in vitro. Journal of Functional Foods. 2012;4(1):294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2011.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang R., Sun P., Zhou Y., Zhao X. Preventive effect of Dendrobium candidum Wall. ex Lindl. on activated carbon-induced constipation in mice. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2015;9(2):563–568. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Feng X., Zhao L., Chen H., Zhou Y., Tang J. J., Chu Z. Y. Research on toxicological security of Dendrobium candidum protocorms. Chinese Journal of Health Laboratory Technology. 2014;3:355–358. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fu J. Y., Xia Y., Xu C. J., et al. Toxicity and Safety Evaluation of Dendrobium officinale's extracting solution. Zhejiang Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;4:250–251. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zheng S., Wu H., Li Z., Wang J., Zhang H., Qian M. Ultrasound/microwave-assisted solid-liquid-solid dispersive extraction with high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry for the determination of neonicotinoid insecticides in Dendrobium officinale. Journal of Separation Science. 2015;38(1):121–127. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201400872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tan X. M., Wang C. L., Chen X. M., et al. In vitro seed germination and seedling growth of an endangered epiphytic orchid, Dendrobium officinale, endemic to China using mycorrhizal fungi (Tulasnella sp.) Scientia Horticulturae. 2014;165:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2013.10.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Xu X. B., Ma X. Y., Lei H. H., et al. Proteomic analysis reveals the mechanisms of Mycena dendrobii promoting transplantation survival and growth of tissue culture seedlings of Dendrobium officinale. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2015;118(6):1444–1455. doi: 10.1111/jam.12781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li X., Chen Y., Lai Y., Yang Q., Hu H., Wang Y. Sustainable utilization of traditional chinese medicine resources: systematic evaluation on different production modes. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2015;2015:10. doi: 10.1155/2015/218901.218901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bai Y., Bao Y. H., Jin J. X., Yan Y. N., Wang W. Q. Resources Investigation of Medicinal Dendrobium in China. Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs. 2006;37(9):I0005–I0007. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Luo J. M. Preliminary Inquiry of Dendrobium officinale's industry and market development. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 2013;38(4):472–474. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yao L. G., Hu Z. B., Zheng Z. R., et al. Preliminary study on the DNA barcoding in Dendrobium officinale germplasm resources. Acta Agriculturae Shanghai. 2012;28(1):49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen X. M., Wang C. L., Yang J. S., Guo S. X. Research progress on chemical composition and chemical analysis of Dendrobium officinale. Chinese Pharmaceutical Journal. 2013;48(19):1634–1640. doi: 10.11669/cpj.2013.19.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhang Z. C., Chen J. B., Ma Z. W., et al. Discrepancy and correlation analysis on main phenotypic traits of Dendrobium officinale. Guangdong Agricultural Sciences. 2010;37(8):78–80. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chu C., Yin H., Xia L., Cheng D., Yan J., Zhu L. Discrimination of Dendrobium officinale and its common adulterants by combination of normal light and fluorescence microscopy. Molecules. 2014;19(3):3718–3730. doi: 10.3390/molecules19033718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Teixeira da Silva J. A., Jin X., Dobránszki J., et al. Advances in Dendrobium molecular research: applications in genetic variation, identification and breeding. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2016;95:196–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Xiao Y. Y., Weng J. Y., Fan J. S. Pharmacognosy identification of Dendrobium officinale and Dendrobium devonianum. Strait Pharmaceutical Journal. 2011;23(4):52–53. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bao Y. H., Pan C. M., Bai Y. Comprehensive analysis of identification characters of three medicinal dendrobii. Journal of South China Normal University (Natural Science Edition) 2014;46(3):112–117. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shen J., Ding X., Liu D., et al. Intersimple sequence repeats (ISSR) molecular fingerprinting markers for authenticating populations of Dendrobium officinale Kimura et MIGO. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2006;29(3):420–422. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Feng S., He R., Yang S., et al. Start codon targeted (SCoT) and target region amplification polymorphism (TRAP) for evaluating the genetic relationship of Dendrobium species. Gene. 2015;567(2):182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.04.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Feng S. G., Lu J. J., Gao L., Liu J. J., Wang H. Z. Molecular phylogeny analysis and species identification of Dendrobium (Orchidaceae) in China. Biochemical Genetics. 2014;52(3-4):127–136. doi: 10.1007/s10528-013-9633-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rui T. T. Yunnan has completed Dendrobium officinale's fine gene map, which will push the province's Dendrobium industry. 2013.

- 103.Hou S. Z., Huang S., Liang Y. M., et al. The medicinal use of Dendrobium officinale. China Patent CN102552698A, 2012.

- 104.Liu B., Chen Q. Q., Liu Y., et al. Preparation method of Dendrobium candidum plant protein lactic acid drink. China Patent CN102940038A, 2013.

- 105.He Z. H., He X. P. One kind of anti-asthenopia Dendrobium candidum. China Patent CN103961556A, 2014.

- 106.He Z. H., He X. P. One kind of immuno-enhancement Dendrobium officinale health products. China Patent CN103816389A, 2014.

- 107.Chen L. Z., Lou Z. J., Wu R. Z., et al. The application of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides of the medicine preventing and treating hypertension and stroke. China Patent CN101849957B, 2012.

- 108.Cai C. G., Zhang W. D., Zhang M. R. One kind of hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic Dendrobium officinale compounds and its preparation method, China Patent CN104126746A, 2014.

- 109.China Food Drug Administration. http://www.sfda.gov.cn/WS01/CL0001/