Abstract

Objectives

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the pulmonary arteries (CTPA) has become the mainstay to evaluate patients with suspected pulmonary embolism (PE), and is one of the most common contrast-enhanced CT imaging studies performed in the emergency department (ED). While contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) is a known complication, this risk is not well-defined in the ED or other ambulatory setting. The aim of this study was to define the risk of CIN following CTPA.

Methods

The authors enrolled and followed a prospective, consecutive cohort (June 2007 through January 2009) of patients who received intravenous contrast for CTPA in the ED of a large, academic tertiary care center. Study outcomes included 1) CIN defined an increase in serum creatinine ≥0.5 mg/dL or ≥25%, 2 to 7 days following contrast administration; and 2) severe renal failure defined as an increase in serum creatinine to ≥3.0 mg/dL, or the need for dialysis within 45 days and/or renal failure as a contributing cause of death at 45 days, determined by the consensus of three independent physicians.

Results

One hundred seventy-four patients underwent CTPA, which demonstrated acute PE in 12 (7%, 95% CI = 3% to 12%). Twenty-five patients developed CIN (14%, 95% CI = 10% to 20%) including one with acute PE. The development of CIN after CTPA significantly increased the risk of the composite outcome of severe renal failure or death from renal failure within 45 days (relative risk = 36, 95% CI = 3 to 384). No severe adverse outcomes were directly attributable to complications of venous thromboembolism (VTE) or its treatment.

Conclusions

In this population, CIN was at least as common as the diagnosis of PE after CTPA; the development of CIN was associated with an increased risk of severe renal failure and death within the subsequent 45 days. Clinicians should consider the risk of CIN associated with CTPA and discuss this risk with patients.

INTRODUCTION

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) imaging of the pulmonary arteries (CTPA) has become a standard modality for the emergent diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism (PE).1 Underlying the increasing rate of CTPA use is the challenge of diagnosing acute PE, a well-recognized difficult diagnostic evaluation for physicians. Recognizing that PE can cause sudden unexpected death, physicians are compelled to test for it at a low threshold.2,3 As a result, CTPA testing has become one of the most frequently ordered advanced imaging procedures in emergency departments (EDs), and over one-third of patients who receive one CTPA go on to have another CTPA within 5 years.4 Moreover, approximately 90% of these repeated CTPA scans are negative for PE. Recent literature has emphasized the potential for the ionizing radiation from CT scanning of the torso to increase the lifetime risk of malignancy.5 Einstein et al. have estimated that one of every 300 patients who undergo coronary CT scanning (which carries a similar radiation dose and distribution of exposure to key organs as CTPA) will develop malignancy as a direct result of the radiation from the CT scan.6 CTPA also requires intravenous contrast, which can cause acute kidney injury (AKI), and while contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) is well-described following coronary imaging, literature defining the risk of CIN following CECT imaging, of any type, is severely lacking.

To date, no study has performed a protocol-designed, prospective evaluation that specified the measurement of paired creatinine concentrations, and no study has followed patients undergoing CTPA for the endpoint of severe renal failure over 30 days. Two independent studies found that 8% of patients developed laboratory-defined contrast nephropathy within seven days after CTPA.7,8 However, these were retrospective studies or secondary analyses lacking an a priori plan to collect specific variables needed to identify the outcome of CIN in an ambulatory population, providing the primary motivation for this study.

Based on the previously published retrospective data, the first objective of this study was to measure the incidence of laboratory-defined contrast nephropathy after CTPA and the rate of subsequent severe renal failure in a prospective cohort of ED patients. The second objective was to compare the incidence of CIN and the frequencies of potential predictor variables for CIN for patients undergoing CTPA compared with patients undergoing other types of CECT. The third objective was to report the frequencies of potential predictor variables for CIN within the CTPA population and compare them between those who did and did not develop CIN.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a prospective study of consecutive outpatients undergoing CECT imaging from June 2007 through November 2008 in the ED. This report is a pre-planned analysis of the subset of patients who underwent CTPA to exclude PE. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Carolinas HealthCare System.

Study Setting and Population

The study was conducted at Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, NC, an urban, academic center with an annual ED volume >110,000 patients per year, which is part of the Carolinas HealthCare System. Imaging studies were performed using two multi-detector Siemens Somatom Sensation 64-slice scanners (Siemens Medical Solutions Inc, Malvern, PA) available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and images were interpreted in real time by on-site board-certified radiologists. This institution uses Iopamidol-370 (Isovue-370, Bracco Diagnostics, Princeton, NJ) for all CT imaging, including CTPA studies. Data were collected from patients undergoing imaging studies of any region of the body. The overall incidence of CIN from CECT has been previously published.9

The methods of screening and enrollment have been previously described.9 Briefly, eligible patients were identified by trained research associates who reviewed the order-entry system (Centricity, GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, UK) in real time and approached patients while they were still in the ED, and written, informed consent was obtained as soon as was practical after the CTPA imaging order was placed. Data including the clinical indication for the study and type of imaging ordered were collected at the time of enrollment.

We excluded patients with any of the following: 1) age <18 years; 2) hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis within 45 days prior to enrollment, or documented prior physician-directed plans to start dialysis within 45 days after enrollment; 3) kidney transplant prior to or planned at the time of enrollment; 4) intravenous contrast for any reason within 14 days prior to enrollment; 5) pregnancy or post-partum <48 hours; 6) patients with immediately life-threatening injuries as classified by the institutional guidelines; 7) the inability to provide written, informed consent; or 8) patient-stated unavailability for the follow-up blood draw.

Study Protocol

At enrollment, standard phlebotomy techniques were used to collect venous blood and, within 30 minutes of collection, we measured a baseline serum creatinine (sCr) concentration (i-STAT, Abbott Point of Care, Inc; East Windsor, NJ). Clinical data were collected at the bedside, including literature-derived presumptive risk factors for CIN.10,11

Patients who were not admitted to the hospital either physically returned to our hospital for study-required phlebotomy, or had a study-sponsored home health nurse visit 2 to 7 days following enrollment for a follow-up blood draw for sCr measurement. A study phlebotomist obtained the study blood sample from admitted patients who were inpatients at the time of follow-up.9

The primary endpoint of this study was laboratory-defined CIN, requiring an increase in sCr of ≥0.5 mg/dL or ≥ 25% within 2 to 7 days of contrast administration.9,12,13 In the event of multiple creatinine measurements performed during this period, the highest creatinine was used to determine the presence or absence of CIN. We followed patients for 45 days, using a combination of telephone and medical record review. Briefly, we recorded the patients’ primary and any secondary telephone numbers. The centralized medical record system provides access to records from 25 hospitals and over 100 primary and specialty practice locations. Starting at 45 days after enrollment, we reviewed the electronic medical records for outcomes and made five separate attempts, on five different days at various times, to contact the patient for telephone interview. If this was unsuccessful, we also reviewed the electronic medical record for any additional contact numbers. The methods of follow-up have been previously published.9,14

The secondary endpoint was the composite of either severe renal failure or death with renal failure as a contributing cause within 45 days. Death from renal failure was determined to be present or absent for all decedents within 45 days of contrast administration by the adjudicated consensus of two of three blinded physician reviewers, which included an EP and a nephrologist in all cases. The explicit definition used by reviewers was obvious evidence of renal failure, defined by worsening azotemia with complications of renal failure including oliguria, pulmonary edema, hyperkalemia, pericardial effusion, or the need to initiate dialysis (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis) prior to death. Additionally, adjudicators were asked to determine from a comprehensive medical record review, if any of these events significantly contributed to the death event. Severe renal failure was defined as a rise in sCr to ≥3.0 mg/dL,15 or the need for dialysis within the follow-up period. Adverse outcomes from VTE and subsequent treatment included respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilatory support, circulatory shock requiring vasopressor treatment or rescue thrombolysis (mechanical or pharmacological), death attributed to PE, or hemorrhage requiring blood cell transfusion or an invasive procedure for hemostasis. Finally, we also report the 45-day incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) defined as confirmed PE or deep venous thrombosis (DVT) on any imaging study interpreted by a board-certified radiologist who had no access to data from this study, including CTPA, formal pulmonary arterial angiography, ventilation-perfusion imaging, or compression ultrasonography of the veins of an extremity. Diagnosis of VTE also required the concomitant clinical decision to initiate anticoagulation (in the absence of contraindications) for at least three months.

Data Analysis

We reported overall outcome incidence, population characteristics, and presumptive risk factors as proportions with associated 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method (STATSDirect V3.3 software, Chesire, UK). The associated risk of secondary outcomes was assessed using the lower limit of the 95% CI for the risk of CIN and the combined outcome of severe renal failure and/or death from renal failure. Prior to assigning the adjudicated outcome of severe renal failure or death from renal failure, the inter-rater agreement was assessed and reported as Cohen’s kappa with the associated 95% CI.

RESULTS

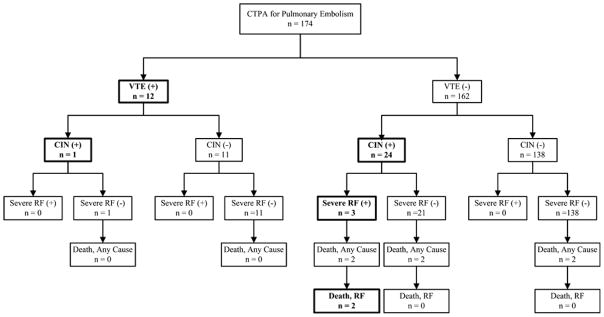

We enrolled and followed 633 patients who underwent CT imaging of any body part, including 174 patients who underwent CTPA to exclude PE, representing the primary group for this report. A diagram summarizing the enrollment and follow-up of eligible patients for this study is shown in Figure 1. The incidence of laboratory defined CIN after CTPA was 25 out of 174, or 14% (95% CI = 10% to 20%). In comparison, the overall frequency of laboratory-defined CIN following non-CTPA studies was 10% (95% CI 7 to 13%). Table 1 compares the clinical characteristics of patients who underwent CTPA and non-CTPA studies.16,17 A higher proportion of patients with prior VTE, active malignancy, congestive heart failure, and vascular disease (coronary, renal, peripheral, or cerebrovascular disease) underwent CTPA than other CT imaging studies. Table 2 compares the clinical characteristics of CIN(+) and CIN(−) patients following CTPA. None of the proportion differences in characteristics reported in Table 2 reach statistical significance.

Figure 1.

Enrollment and follow-up of eligible patients. CIN = contrast-induced nephropathy; CTPA = contrast-enhanced computed tomography imaging of the pulmonary arteries. *Patients were excluded if contrast-enhanced CT imaging was cancelled or converted to a non-contrast study.

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical characteristics, including literature-derived risk factors for contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN), for patients who underwent contrast-enhanced computed tomography imaging of the pulmonary arteries (CTPA) and non-CTPA studies.

| Characteristic | CTPA n = 174 |

Non-CTPA n = 459 |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age yr, mean (±SD) | 50 (±16) | 46 (±15) |

| Female sex | 35 (28–43) | 47 (41–51) |

| White race | 37 (29–44) | 41 (36–45) |

| African American race | 58 (50–65) | 50 (45–55) |

| Other race | 6 (3–10) | 9 (7–12) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Prior VTE | 9 (5–14)^ | 2 (1–3)^ |

| Active malignancy | 16 (11–22)^ | 5 (3–7)^ |

| Estrogen use | 1 (0–4) | 1 (0–3) |

| Immobilization | 2 (0–6) | 1 (0–3) |

| History of COPD | 6 (3–10) | 2 (1–4) |

| Trauma or surgery within previous 4 weeks | 6 (3–10) | 4 (2–6) |

| Presumptive risk factors for CIN* | ||

| Age > 70 yr | 9 (5–14) | 6 (4–9) |

| Anemia | 11 (7–17) | 13 (10–16) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 19 (14–26) | 17 (13–20) |

| History of hypertension | 54 (46–62) | 39 (35–44) |

| Vascular disease† | 15 (10–21)^ | 8 (6–11)^ |

| Congestive heart failure | 12 (7–18)^ | 5 (4–8)^ |

| Baseline renal insufficiency‡ | 10 (6–15) | 10 (8–13) |

VTE = venous thromboembolism (deep venous thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism); COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Literature-derived factors that are commonly identified as risk factors for CIN. These are primarily derived from patient populations undergoing coronary angiography.11,24

Defined as a patient-reported history of cerebral, coronary, renal, or peripheral vascular disease

Defined as a baseline glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73m2 using the Modification in Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) method.25

Comparisons reach significance, based on a 95% CI of the difference in proportion >1%.

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical characteristics, including literature-derived risk factors for contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN), for CIN(+) and CIN(−) patients.

| Characteristic | CIN (+) N = 25 |

CIN (−) N = 149 |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age yr, mean (±SD) | 58 (±14) | 49 (±16) |

| Female sex | 42 (23–63) | 34 (27–42) |

| White race | 46 (26–67) | 35 (27–43) |

| African American race | 46 (26–67) | 60 (52–68) |

| Other race | 8 (1–25) | 5 (2–9) |

| Clinical Characteristics | ||

| Prior VTE | 8 (1–25) | 10 (6–16) |

| Active malignancy | 23 (9–44) | 15 (9–21) |

| Estrogen use | 4 (0–22) | 1 (0–4) |

| Immobilization | 8 (1–25) | 1 (0–5) |

| History of COPD | 12 (2–30) | 4 (1–9) |

| Trauma or surgery within previous 4 weeks | 4 (0–20) | 6 (3–11) |

| Presumptive Risk Factors for CIN* | ||

| Age > 70 yr | 19 (7–39) | 9 (5–14) |

| Anemia | 15 (4–35) | 11 (6–17) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 27 (12–48) | 18 (12–25) |

| History of hypertension | 62 (41–80) | 53 (44–61) |

| Vascular disease† | 23 (4–35) | 13 (8–20) |

| Congestive heart failure | 23 (9–44) | 10 (6–16) |

| Baseline renal insufficiency‡ | 4 (0–20) | 11 (7–18) |

CIN = Contrast-induced nephropathy; VTE = venous thromboembolism (deep venous thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism); COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Literature derived factors that are commonly identified as risk factors for CIN. These are primarily derived from patient populations undergoing coronary angiography.11,16

Defined as a patient-reported history of cerebral, coronary, renal or peripheral vascular disease

Defined as a baseline glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73m2 using the Modification in Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) method.17

Outcome and follow-up data for the entire cohort are previously published.9 We completed the follow-up blood draw (for the determination of the primary outcome, CIN) in 119 of the CTPA patients (68%, 95% CI = 61% to 75%). However, telephone interview and medical record follow-up successfully defined the 45-day outcomes (including VTE, severe renal failure, and death) for 41 of the 55 patients who missed the follow-up blood draw. Thus, 92% (160 ou6t of 174, 95% CI = 87% to 96%) of patients who underwent CTPA in this study completed either the initial or 45-day follow-up. The clinical characteristics of the remaining 8% of patients who were lost to follow-up do not differ from those of patients who completed follow-up.9

A total of 12 patients (7%, 95% CI = 4% to 12%) had acute PE identified, and were treated for PE on the enrollment CTPA, and five of these 12 also had DVT identified by compression ultrasonography performed within 12 hours of enrollment. No occurrences of DVT or PE were identified in patients who did not undergo CTPA at enrollment, and no additional occurrences of VTE were identified within the 45-day follow-up period. All patients with VTE were treated acutely with heparin anticoagulation, followed by anticoagulation with orally administered warfarin sodium. No patient with VTE developed a predefined adverse outcome from PE (respiratory failure, circulatory shock, death attributed to PE, or hemorrhage). Patients with and without VTE developed CIN at similar rates: 8% (1 of 12, 95% CI = 0 to 38%) and 15% (24 of 162, 95% CI = 10% to 21%), respectively.

Figure 2 summarizes the severe outcomes, including severe renal failure, all-cause death, and death from renal failure. Seven patients (4%, 95% CI = 2% to 8%) developed at least one of these severe outcomes. The all-cause 45-day mortality rate among patients who underwent CTPA was 6/174 (3%, 95% CI = 1% to 7%) compared with 9/459 (2%, 95% CI = 1% to 4%) for non-CTPA scans. For all six deaths, adjudicators independently assigned the outcome of death from renal failure with 100% agreement (Cohen’s kappa 1.0, 95% CI = 0.2 to 1.8). Four of the six deaths after CTPA were in patients who had CIN; adjudicators identified renal failure as a significant contribution to death in two of these four patients. The two other CTPA patients died from advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma, but without evidence of CIN. No patient with VTE had severe renal failure or died within the 45-day follow-up period. One additional CTPA patient (without VTE), developed CIN followed by severe renal failure, but did not die within the 45-day follow-up period. Renal failure was not identified as a contributing factor to the deaths of any patient who did not develop CIN prior to death after CTPA.

Figure 2.

Enrollment and follow-up of eligible patients. CIN = contrast-induced nephropathy; CTPA = contrast-enhanced computed tomography imaging of the pulmonary arteries. *Patients were excluded if contrast-enhanced CT imaging was cancelled or converted to a non-contrast study.

The overall net rate of CIN complicated by severe renal failure or death from renal failure after CTPA was 3 of 174, whereas the rate of adverse outcomes directly attributable to VTE or its treatment was zero. The development of CIN after CTPA was associated with an increased risk of the composite outcome of severe renal failure or death from renal failure within 45 days (relative risk = 36, 95% CI = 3 to 384). Development of CIN was associated with an increased risk of death from any cause (relative risk = 12, 95% CI = 3 to 53). Diagnosis of VTE did not increase the risk of adverse outcomes.

DISCUSSION

This study presents data from the first prospective study designed to measure the incidence of CIN after CTPA. The primary finding was that the frequency of CIN following CTPA is significant, occurring in at least 10% of patients, and is associated with increased risk of severe outcomes including severe renal failure and death, observed in 16% of patients who developed CIN after CTPA. The population characteristics of patients undergoing CTPA were typical of patients evaluated for PE in the ED setting,18 which included patients with a higher rate of previous VTE, and those with active malignancies, when compared to the population of ED patients receiving other CECT studies. The outcome of CIN was observed at least as often as was the diagnosis of PE after CTPA, and the 7% frequency of PE in our cohort was comparable to that of other ED populations.16 Additionally, the prevalence of vascular disease and congestive heart failure was higher among patients undergoing CTPA compared to the general CECT population, which more closely approximates the cardiac catheterization population. Thus, selection bias was unlikely to contribute to the incidence of CIN and subsequent severe renal failure and death observed in this population.

Deaths following CTPA were more closely associated with development of CIN as opposed to the diagnosis of PE. No patient had a PE-related adverse outcome, whereas three patients (2%) had severe AKI after CTPA, and none of these three had PE. These results provide a basis to assert that the risk-to-benefit ratio for CTPA may be higher than previous literature had suggested. For example, the PIOPED II study reported only one instance of dialysis-dependent renal failure after CTPA in 824 patients.19 In contrast to the present work, PIOPED II was not designed to explicitly follow patients for evidence of AKI. Somewhat unexpectedly, we found that only 4% of patients with CIN after CTPA had a low baseline glomerular filtration rate, whereas 11% of patients who did not develop CIN after CTPA had a low baseline glomerular filtration rate. This observation suggests that baseline renal insufficiency may be an insensitive predictor of CIN after CTPA.

There are three controversies addressed by this subanalysis that distinguish it from our previously published study,9 which aimed at determining the incidence of CIN in the general ED population undergoing CECT for a variety of indications: 1) the comparability of the general ED population to patients undergoing cardiac catheterization; 2) the lack of readily available, well-characterized imaging alternatives for the majority of CT imaging indications, with the notable exception of CTPA; and 3) the comparatively narrow diagnostic indications for CTPA compared to other CT imaging studies. These represent our motivations for performing this pre-planned subanalysis.

Based on the published data in “low-risk” patients undergoing cardiac catheterization, the predicted rate of CIN in the heterogeneous ED population undergoing a range of CECT imaging studies is around 4%.20 For this estimate, “low-risk” was defined by the rate of CIN observed in younger cardiac catheterization populations with a low prevalence of traditional risk factors such as renal insufficiency and diabetes mellitus. We observed an overall rate of CIN of 11% in ED patients undergoing CECT imaging studies for all indications. Conversely, the prevalence of traditional risk factors for CIN observed in the ED population remained very low, and was lower than thresholds used to define low-risk cardiac catheterization populations. Anticipating that any observed difference may be attributable to specific population differences, or simply a result of the heterogeneity intrinsic to an ED population, we selected the CTPA population because it is the closest comparison to the cardiac catheterization population. In fact, approximately 20% of ED patients who are evaluated for acute chest pain receive simultaneous testing for both VTE and acute coronary syndromes.21 Here, we found that the incidence of CIN (14%) remains much higher than would be anticipated from that observed among patients undergoing cardiac catheterization for acute chest pain, and remains comparable to the rate observed in retrospective studies.7,8

Among the indications for CECT, there are very few equivalent or near-equivalent diagnostic imaging alternatives that avoid iodinated contrast exposure, particularly in the ED setting. Ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) imaging is both commonly available and is an alternative to CTPA in the ED setting. The most common indication for V/Q imaging instead of CTPA is concern for CIN, usually in the presence of renal insufficiency.22 Incidentally, contrast allergy is also a consideration for V/Q imaging. However, severe reactions to contrast in the ED setting are extremely rare.23 Here we found that an elevated creatinine measurement was not associated with an increased risk of CIN following CTPA.

In comparison to other CECT imaging studies commonly performed in the ED setting, CTPA studies are performed for a relatively narrow clinical consideration, to exclude PE, a disease for which the risks and benefits of emergent identification and initiation of treatment are well-defined, and favor a low test threshold.2,3 Other types of CECT studies are either performed much less frequently or for a much more broad set of clinical considerations, complicating the estimation of risk directly attributable to the imaging study. We found that the incidence of CIN following CTPA (10%) remained comparable to that observed in patients undergoing CECT for other indications (11%).

The present data have at least two immediate implications. First, the frequency of CIN and severe renal failure must be incorporated in cost-effectiveness analyses. Recently, Lessler et al. used a cost-effectiveness analysis to estimate the test threshold for PE at 1.4%.3 Lessler et al. assumed a zero risk of subsequent death or acute renal failure.3 Our data suggest that this is a significant underestimation of the risk associated with CTPA, and the inclusion of our data would have significantly raised the test threshold. Second, from a patient-oriented standpoint, the present data suggest that clinicians should explain to every patient undergoing CTPA that kidney injury is a possible side effect, even if the patient has a normal serum creatinine prior to performing CTPA. However, because of the uncertainty of effect size in the CTPA population, we do not believe the present data support a more liberal use of renoprophylaxis.

Contrast-induced nephropathy is characterized by the development of minimal AKI, which is usually asymptomatic for two to seven days following the administration of intravenous, iodinated contrast media. Accordingly, detection of CIN requires specific renal function testing within a limited time frame after contrast administration (at least 48 to up to 170 hours). The present sample showed that one-half of patients with CIN went on to develop a major endpoint from AKI. This observation adds to previous work indicating that CIN is associated with a greatly increased risk of acute severe renal failure, as well as increased risk of coronary and cerebrovascular morbidity and death in the following months.9,12,15 If the present findings are reproduced, this could cause a major re-evaluation of the management strategies for patients with suspected PE.

LIMITATIONS

We believe this study is the first prospective, non-interventional study to document the incidence of CIN after CTPA, and as a result, we have no predicate data to allow us to compare and contrast our findings with other populations.12,24 While this report is the result of a secondary analysis, the analysis was planned, a priori, with collection of the data necessary to measure the outcome in this population. The inference that a low baseline glomerular filtration rate may not predict CIN after CTPA requires further validation. To estimate the possible importance of our main finding, we compare the frequency of clinically significant acute kidney injury after CTPA with the frequency of clinically significant complications from VTE or anticoagulation for VTE. However, we strongly emphasize that this comparison is intended as a context-specific illustration of the potential significance of contrast-related problems after CTPA, and not intended to suggest a net harm from CTPA scanning. The protocol excluded critically ill or severely injured patients, which account for approximately 20% of all contrast-enhanced CT imaging studies performed in our ED.25 Nine percent of patients were lost to follow-up. It is also possible that the post-CTPA serum creatinine concentration peaked before two days or after seven days in some patients. Each of these limitations represents a source of sampling bias that could affect the internal validity of our observed frequency of CIN. We believe these limitations most likely imparted a net bias that led to an underestimation of the true proportion of CIN following CTPA.

CONCLUSIONS

The incidence of contrast-induced nephropathy complicated by severe renal failure and death after computed tomography of the pulmonary arteries may be higher than has been previously estimated. Traditional risk factors do not adequately identify patients at risk for contrast-induced nephropathy in this population. Additional research is needed to validate these findings and to develop alternatives to computed tomography of the pulmonary arteries in the evaluation of patients for pulmonary embolism in the acute care setting.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: Research Forum, American College of Emergency Physicians; September 2010; Las Vegas, NV

Disclosures: Dr. Mitchell was supported in part by the Emergency Medicine foundation, Dr. Jones has grants pending from the NIH and from Thermoscientific. He has provided expert testimony for multiple lawfirms. Dr. Tumlin has no disclosures or conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2276–315. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Courtney DM, Sasser H, Pincus B, et al. Pulseless electrical activity with witnessed arrest as a predictor of sudden death from massive pulmonary embolism in outpatients. Resuscitation. 2001;49:265–72. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(00)00374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lessler AL, Isserman JA, Agarwal R, et al. Testing low-risk patients for suspected pulmonary embolism: a decision analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:316–26. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kline JA, Courtney DM, Beam DM, et al. Incidence and predictors of repeated computed tomographic pulmonary angiography in emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography--an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2277–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Einstein AJ, Henzlova MJ, Rajagopalan S. Estimating risk of cancer associated with radiation exposure from 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography. JAMA. 2007;298:317–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kooiman J, Klok FA, Mos IC, et al. Incidence and predictors of contrast-induced nephropathy following CT-angiography for clinically suspected acute pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:409–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell AM, Kline JA. Contrast nephropathy following computed tomography angiography of the chest for pulmonary embolism in the emergency department. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:50–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell AM, Jones AE, Tumlin JA, et al. The incidence of contrast-induced nephropathy following contrast-enhanced computed tomography in the outpatient setting. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:4–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05200709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett BJ, Katzberg RW, Thomsen HS, et al. Contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing computed tomography: a double-blind comparison of iodixanol and iopamidol. Invest Radiol. 2006;41:815–21. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000242807.01818.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harjai KJ, Raizada A, Shenoy C, et al. A comparison of contemporary definitions of contrast nephropathy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention and a proposal for a novel nephropathy grading system. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:812–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solomon RJ, Mehran R, Natarajan MK, et al. Contrast-induced nephropathy and long-term adverse events: cause and effect? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1162–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00550109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gami AS, Garovic VD. Contrast nephropathy after coronary angiography. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:211–9. doi: 10.4065/79.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kline JA, Mitchell AM, Runyon MS, et al. Electronic medical record review as a surrogate to telephone follow-up to establish outcome for diagnostic research studies in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1127–33. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hou SH, Bushinsky DA, Wish JB, et al. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency: a prospective study. Am J Med. 1983;74:243–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90618-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrett BJ, Katzberg RW, Thomsen HS, et al. Contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing computed tomography: a double-blind comparison of iodixanol and iopamidol. Invest Radiol. 2006;41:815–21. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000242807.01818.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, et al. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–70. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kline JA, Courtney DM, Kabrhel C, et al. Prospective multicenter evaluation of the pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:772–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stein PD, Fowler SE, Goodman LR, et al. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2317–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katzberg RW, Barrett BJ. Risk of iodinated contrast material--induced nephropathy with intravenous administration. Radiology. 2007;243:622–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2433061411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogg JG, De Neve JW, Huang C, et al. The triple work-up for emergency department patients with acute chest pain: how often does it occur? J Emerg Med. 2011;40:128–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall PS, Matthews KS, Siegel MD. Diagnosis and management of life-threatening pulmonary embolism. J Intensive Care Med. 2011;26(5):275–94. doi: 10.1177/0885066610392658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell AM, Jones AE, Tumlin JA, et al. Immediate complications of intravenous contrast for computed tomography imaging in the outpatient setting are rare. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:1005–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta R, Gurm HS, Bhatt DL, et al. Renal failure after percutaneous coronary intervention is associated with high mortality. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;64:442–8. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell AM, Kline JA. Systematic bias introduced by the informed consent process in a diagnostic research study. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:225–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]