Abstract

Most of the complement proteins in circulation are, by and large, synthesized in the liver. However data accumulated over the past several decades provide incontrovertible evidence that some if not most of the individual complement proteins are also synthesized extrahepatically by activated as well as non-activated cells. The question that is finally being addressed by various investigators is: are the locally synthesized proteins solely responsible for the myriad of biological functions in situ without the contribution of systemic complement? The answer is probably “yes”. Among the proteins that are synthesized locally, C1q takes center stage for several reasons. First, it is synthesized predominantly by potent antigen presenting cells such as monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs), which by itself is a clue that it plays an important role in antigen presentation and/or DC maturation. Second, it is transiently anchored on the cell surface via a transmembrane domain located in its A chain before it is cleaved off and released into the pericellular milieu. The membrane-associated C1q in turn, is able to sense danger patterns via its versatile antigen-capturing globular head domains. More importantly, locally synthesized C1q has been shown to induce a plethora of biological functions through the induction of immunomodulatory molecules by an autocrine- or paracrine-mediated signaling in a manner that mimics those of TNFα. These include recognition of pathogen- and danger-associated molecular patterns, phagocytosis, angiogenesis, apoptosis and induction of cytokines or chemokines that are important in modulating the inflammatory response. The functional convergence between C1q and TNFα in turn is attributed to their shared genetic ancestry. In this paper, we will infer to the aforementioned “local-synthesis-for-local function” paradigm using as an example, the role played by locally synthesized C1q in autoimmunity in general and in systemic lupus erythematosus in particular.

Keywords: C1q, dendritic cells, immune tolerance, SLE

1. Structure and biology of C1q and the collectin/ficolin family of proteins

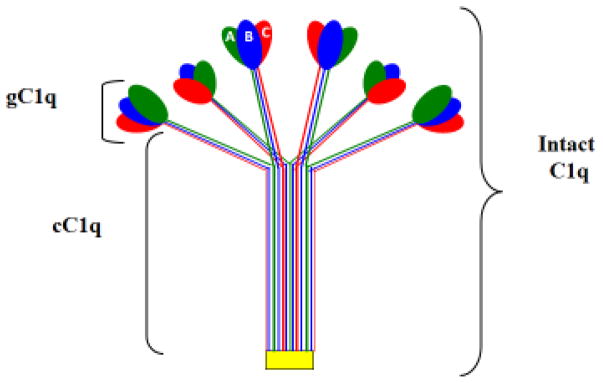

Human C1q (460 kDa) is the recognition unit of the classical pathway of complement (Calcott and Müller-Eberhard, 1972), which circulates in plasma in association with the Ca2+-dependent C1r2-C1s2 tetramer (360 kDa) to form pentameric C1—the first component of complement (Calcott and Müller-Eberhard, 1972; Reid and Thompson, 1983; Reid, 1985; Svehag et al., 1972). It is made up of 3 distinct polypeptide chains, A, B, and C, arranged to form 6 triple helical strands with three peptide chains–A, B, and C–forming a single strand (Knobel et al., 1975; Brodsky et al., 1976; Shelton et al., 1972). The three chains (Table 1 and 2) are the product of three distinct genes, which are highly clustered and aligned 5′⇒ 3′, in the same orientation, in the order A-C-B on a 24 kb stretch of DNA on the short arm of chromosome 1p (1p34.1-1p36.3) (Sellar et al., 1991). The fact that C1q is assembled in a 1:1:1 from its three chains therefore requires precisely synchronized transcription of the three C1q genes (Sellar et al., 1991). Each of the six trimeric globular ‘heads” or domains’, is made up of the globular domains from one A, one B, and one C chain (Fig. 1), each of which in turn has its own ligand specificity capable of recognizing different molecular patters (Kishore et al., 2004, Gaboriaud et al., 2007). The globular “heads” are linked via six collagen-like ‘stalks’ to a fibril-like central region resulting in two unique structural and functional domains: the collagen-like region (cC1q) and the globular ‘heads’ or domains (gC1q) (Knobel et al., 1975; Brodsky et al., 1976; Shelton et al., 1972). The two C1q domains can independently interact with a multiplicity of biological structures including pathogen-associated and cell associated molecules. However, it is the gC1q domain itself that defines the versatility of the C1q molecule, with each of the individual globular head domain (ghA, ghB, ghC) capable of independently interacting with danger ligands (Kishore et al., 2002, Gaboriaud et al, 2007).

Table 1.

Components of the C1 complex

| Proteins | Mr(kDa) | Chain structure | Mr(kDa)each chain | Plasma concentration(μ/ml) | Chromosomal location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1q | 460 | 18(6A,6B,6C) | A=28 B=26 C=24 |

80–100 | 1p34.1-1p36.3 1p34.1-1p36.3 1p34.1-1p36.3 |

| C1r2 | 86–90 | 2 | 86–90 | 50 | 12p13.31 |

| C1s2 | 80–83 | 2 | 80–83 | 50 | 12p13.31 |

C1r and C1s circulate in plasma either as a pentamolecular complex with C1q (C1q.C1r2.C1s2), or as a tetramolecular complex–C1r2C1s2–in the absence of C1q. Each of the C1r and C1s chains is activated through cleavage at a single site–between Arg and Ile for C1r and Arg-Ile or Lys-Ile for C1s–to generate an enzymatically active two-chain molecule of ~60 kDa and a ~30 kDa, with the smaller fragment containing the catalytic site in each molecule.

Table 2.

Genetic C1 deficiency and disease association

| Protein | Inherited deficiency | Frequently found mutation | Disease Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1q | Autosomal recessive | G2687C to T→stop codon | SLE, RA, recurrent bacterial infections, pneumonia, sepsis and cancer |

| C1r | Autosomal recessive | Not Known | SLE, bacterial infections, rhinobrinchitis, impaired immune adherence |

| C1s | Autosomal recessive | Not Known | SLE, bacterial infection, impaired immune adherence |

The diseases associated with deficiency in any of the C1 molecules is more extensive than the very few examples listed here. The hierarchy of significance in SLE is the deficiency in: C1q, C1r, C1s, C4 and C2; with C1q deficiency almost invariably being associated with SLE and RA

Fig. 1.

The structure of C1q. The major domains of C1q are shown together with the individual ghA, ghB and ghC domains.

Although C1q is not a lectin in the truest sense of the definition–i.e. macromolecules containing high specificity carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) for sugar moieties (Weis et al., 1991 and 1992) on danger-associated or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs or PAMPs)–it is nonetheless considered to be a member of this class of molecules by virtue of having not only structural but also functional similarity to both mammalian lectins and ficolins (Holmskov et al, 2003). Members of this group of proteins are similar in structure in that they are oligomeric proteins comprised of a C-type lectin carbohydrate-recognition domain (lectins), or fibrinogen-like carbohydrate-recognition domain (ficolins) attached to a collagenous region respectively (Kölble and Reid, 1993; Holmskov et al., 2003). The collectins include serum proteins: conglutinin, mannose-binding lectin (MBL), collectin-43 (CL-43), and the lung surfactant proteins A and D (SP-A and SP-D) (Kölble and Reid, 1993), whereas the members of the ficolins include L-, M-, and H-ficolins (Matsushita, 2010). Although the ficolins and MBL can trigger complement activation via the lectin pathway, the SP-A and SP-D do not activate complement but instead opsonize pathogens through direct recognition and interaction (Holmskov et al, 2003). Like C1q, collectins can bind to cognate cell surface receptors on phagocytic cells leading to clearance of microorganisms (Kuhlman, 1989; Ferguson et al., 1999). Furthermore, each of this group of proteins is also able to serve as pattern recognition receptor (PRR) by binding to pathogen-associated or danger-associated oligosaccharide structures or lipids (Wu et al., 2003). Currently available data together with newly emerging information also suggests that membrane anchored C1q, like its collectin/ficolin counterparts can also serve as pathogen recognition receptor (PRR) by virtue of its ability to recognize and bind to pathogen-associated or danger-associated molecular patterns via its globular head domains (Kishore et al., 2002, Gaboriaud et al, 2007). Therefore together, the collectins and the C1q family of proteins are able to modulate not only the inflammatory and adaptive responses but also to enhance clearance of apoptotic cells by macrophages.

2. C1q and TNFα: Functional convergence from shared genetic ancestry

Biology has always intimated that each gene product is generated to fulfill a specific biologic function. Implicit in this postulate is the notion that proteins that do not share sequence homology with each other could not possibly perform a similar function. Available empirical data however clearly show that even proteins that do not share sequence homology but instead have adopted similar structural features as the result of shared primordial genetic ancestry, can have functions that mirror each other. Examples of this group of proteins are C1q and TNFα, which, as orthologs–i.e. evolutionary counterparts derived from the same ancestral gene–share numerous structural, biological and functional characteristics (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Comparison of biochemical properties of C1q and TNFα

| Proteins | Mr(kDa) | Chain structure | Mr(kDa) | Plasma concentration (μ/ml) | Chromosomal location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1q* | 460 | 18(6A,6B,6C) | A=28 B=26 C=24 |

80–100 | 1p34.1-1p36.3 1p34.1-1p36.3 1p34.1-1p36.3 |

| sTNFα** | 51 | 3 | 17 | >5pg*** | 6p21.3 |

C1q is initially synthesized as type II membrane anchored protein which is then cleaved and released as a mature protein that is found in plasma and tissues.

TNFα is also produced as type II transmembrane protein and the soluble form (sTNFα) is released via proteolytic cleavage by the metalloprotease TNF alpha converting enzyme (TACE)

Elevated concentrations are observed in various disease states including obesity and dementia

Table 4.

A partial list showing the shared biological properties of C1q and TNFα

| Antigen | Site of Synthesis | Biological and disease processes | Induced Cytokines/Adhe sion molecules |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1q | Monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, glial cells kupffer cell, trophoblasts, fibroblasts and glial cells | Phagocytosis, chemotaxis, chemokinesis, apoptosis, regulation of dendritic cells, cancer, dementia, angiogenesis, wound repair, preeclampsia | -IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 MCP-1-E-selectin, ICAM-1, Vcam-1 |

| TNFα | Monocytes, macrophages, CD4+cells, NK cells, eosinophils, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, adipose tissue | Phagocytosis, cjemotaxis, apoptosis, cachexia, stimulates acute phase response, induces insulin resistance | -IL-1, IL-6.IL-8, IL-18, MCP-1-E_selectin, ICA M-1, Vcam-1 |

The genetic relationship of C1q and TNFα was revealed when the 3D structure of ACRP30 was solved almost 20 years ago (Shapiro et al., 1998). ACRP30 or adiponectin, is a 247-amino acid-long protein exclusively secreted from fat cells and contains an N-terminal collagen-like domain and a C-terminal globular domain, that shares significant homology not only with the globular domains of C1q, but also with those of type VIII and X collagens (Scherer et al., 1995; Berg et al., 2001; Wong et al., 2004). Information derived from the crystal structure of adiponectin also established an evolutionary link between the TNFα and the C1q family of proteins supporting the notion that the two molecules arose by divergence from an ancestral recognition molecule of the innate immune system (Shapiro et al., 1998). It is not therefore surprising to note that in addition to sharing several overlapping biological functions, the two molecules are also synthesized in a similar manner by a broad range of cell types including monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts (Skok et al., 1981) (Table 4). TNFα is synthesized as an approximately 27-kDa trimeric type-II transmembrane precursor protein, which is then cleaved by the metalloprotease TNFα-converting enzyme (TACE) to generate the 17 kDa soluble trimeric form, which in turn signals by autocrine or paracrine induced mechanism to fulfill its various biological functions (Old, 1985; Beutler et al., 1985; Black et al., 1997). These include regulation of immune cells, inhibition of viral replication, and inhibition of cancer through induction of apoptosis (Black et al., 1997). Similarly, although a wide range of cell types are able to synthesize C1q, the major sources of C1q also appear to be the cells of the myeloid lineage such as monocytes, monocytes (Bensa et al. 1983; Randazzo et al. 1985; Tenner and Volkin, 1986; Drouet and Reboul, 1989; Gulati et al 1993; Hosszu et al., 2012) macrophages (Kaul and Loos, 1993a, 1993b), dendritic cells (Vegh et al., 2003; Castellano et al., 2004). Moreover, C1q is also synthesized as a type-II transmembrane protein, which remains membrane-anchored via a transmembrane sequence located in its A-chain until it is enzymatically cleaved off from its anchor domain to generate the soluble form that is found in plasma or tissues (Kaul and Loos 1993b). The pleiotropic functions of TNFα are mediated by two ubiquitously distributed cell surface receptors, called TNFR1 and TNFR2 (Tartaglia et al. 1991), through which it mediates a myriad of biological functions in various organs of the body, which is often in response to microbial products such as LPS (Sedger and McDermot, 2014). These functions in turn are mediated through activation of the major cellular pathways including the NF-KB, MAPK, and the death-signaling pathway (Tartaglia et al. 1991). The major source of preformed TNFα in the skin are mast cells, and is readily released by microbial stimulus and together with IL-1 and IL-6 can induce acute phase responses in the liver leading to the increase of C-reactive protein and other mediators. Similarly, the functions of C1q are also mediated by several cell surface proteins including two ubiquitously distributed multi-functional and multi-compartmental cellular proteins, cC1qR and gC1qR, which possess preferential binding to either the cC1q or gC1q domains (Ghebrehiwet and Peerschke, 2014). However, because both of these molecules lack a consensus sequence for a transmembrane segment, they are postulated to signal by proxy through a growing list of co-receptors including DC-SIGN (Hosszu et al. 2012, CD91 (Ogden, et al., 2001; Duus et al. 2010), CD-44, and β1-integrins (Feng et al., 2002) . In addition to sharing many biological functions that include phagocytosis, chemotaxis and apoptosis (Table 3), C1q and TNFα also induce a remarkably similar profile of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and/or chemokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and MCP-1 (Treede et al., 2009). Moreover, C1q is able to induce adhesion and spreading of endothelial cells (Peerschke et al., 1996) through stimulation and expression of the adhesion molecules E-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 (Lozada et al., 1995); and production of IL-6, IL-8, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (van den Berg et al., 1998), which explains in part why C1q is often present in high quantities at sites of atherosclerosis and inflammatory and vascular lesions. More importantly however, recent experiments especially in the area of cancer pathology, are also revealing that the role of membrane-anchored C1q and soluble C1q my have diametrically opposing roles. While membrane-bound or released into the pericellular milieu is pro-proliferative (Bulla et al., 2016; Ghebrehiwet et al. 2016), soluble C1q is antiproliferative since addition of C1q to proliferating cells inhibits cell growth, and the receptors for C1q, gC1qR and cC1qR as well as adaptive or signal transducing molecules such as ADAM 28 are shown to be involved (Ghebrehiwet et al., 1990; Miayamae et al., 2016).

3. Locally synthesized C1q induces in situ functions through an autocrine/paracrine signal

An attempt to establish the ontogeny of each of the human complement proteins has been the subject of several laboratories even as far back as the mid 60’s despite the fact that it was still believed that the liver was the primary site of synthesis of complement proteins (Alper et al. 1966). Local synthesis of complement in turn, would suggest an important biological function in situ. The in vitro synthesis of a fully functional complement protein–or C1 to be precise–was first demonstrated in vitro in the columnar epithelial cells of the small intestine of the guinea pig (Colten et al., 1966). Others followed these studies and demonstrated synthesis of functional C1 by human colon as well as the ileum (Colten et al., 1968a, 1968b, Colten, 1971). Since these early reports, the collective work of many investigators over the years has firmly established that, fully assembled (C1) or individual components (C1r, C1s,) together with C1-INH are synthesized not only by the cells of the myeloid lineage described above, but also by a wide range of cell types that include: epithelial cells (Colten, 1976), fibroblasts (Reid and Solomon, 1977), mesenchymal cells (Morris et al., 1978), glial cells (Shäffer et al., 2000; Lynch et al., 2004; Farber et al., 2009), trophoblasts (Bulla et al, 2008; Agostonis et al., 2010), osteoclasts (Teo et al., 2012), Kupffer cells (Rubenstein et al., 2015), and more recently by mast cells (van Schaarebburg et al., 2016), The presently accepted postulate is therefore, that locally secreted C1q is an immunomodulatory molecule, which controls cellular responses by an autocrine and/or paracrine induced signaling mechanism (Castellano et al., 2004), and this paradigm is likely to be true for all the individual complement proteins secreted in situ.

In addition to C1q/C1, circulating blood monocytes, macrophages as well as dendritic cells also express the C1q receptors: cC1qR and gC1qR as well as their co-receptors CD91 and DC-SIGN. The cell surface C1 complex, which is regulated by surface associated C1-INH (Randazzo et al., 1985), is presumably formed by a Ca2+-dependent association of the C1r2.C1s2 tetramer to the membrane anchored C1q (Kaul and Loos 193a). In this manner, the globular heads of C1q are strategically displayed outwardly for “sensing” and binding to potential “danger” ligands (Fig 1). Monocytes, which circulate in the blood for 1–3 days before they move into tissues throughout the body, not only serve as precursors of potent antigen presenting macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs), but also fulfill three important functions in the immune system: phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and cytokine production. The expression of membrane attached macromolecular C1/C1q therefore makes monocytes as potent sentinels of danger in the circulation capable of capturing, processing foreign antigens. There is a rapidly expanding list of pathophysiological processes in which C1q has been reported to be a major player (Bulla et al., 2008; Hong et al., 2009; Agostonis et al., 2010; Singh et al., 2011). These pathophysiological processes, which are largely due to the ability of C1q to recognize a wide array of danger ligands are extensive and diverse and include signals that trigger or dampen autoimmunity such as apoptotic cell clearance (Païdassi et al.2008; Clarke et al., 2015) microglial clearance of apoptotic neurons (Fraser et al., 2010) synapse elimination and neuronal pruning (Stevens et al. 2013). The unique structure of C1q, which allows it to interact with its receptors via either its cC1q or gC1q domains may also control the transition from the monocyte state toward the professional antigen presenting cell state. The observation that C1q functions as a molecular switch during the narrow window of monocyte to DC transition (Ghebrehiwet et al. 2004), not only explains why C1q is predominantly synthesized by potent antigen presenting cells (APCs), but also why its absence can impair antigen uptake and tolerance and thus trigger the onset of autoimmune diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

4. Role of C1/C1q in autoimmune diseases: A C1-centric hypothesis

SLE is characterized by chronic or episodic inflammation in several organ systems (Lahita, 1999). Clinical evidence shows that homozygous deficiency in any of the classical pathway proteins—C1q, C1r, C1s, C4 and C2—can lead to the development of SLE and other autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (Pickering et al., 2000; Walport et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2004; Martens et al., 2009, Trouw et al., 2013). Among these proteins, C1q is the most significant because homozygous deficiency or hereditary deficiency due to mutation in the C1q gene (predominantly the A-chain) is a strong susceptibility factor for the development of SLE. To date approximately 12 disease-causing C1q mutations have been identified. Four of these mutations: C1qB, Gly42Asp; C1qB, Arg177X; C1qC, Arg69X; and C1qC, Gln71fsX137 were found in one family, while the C1qC, Gly34Arg mutation was found in families from Germany, India and Saudi Arabia (Schejbel, 2011). Further sequencing of C1q coding genes especially in populations that are prone to develop SLE or RA probably will generate novel mutations. The vast majority (≥95%) of the known individuals with C1q deficiency are known to have developed clinical syndromes closely related to SLE (Nishino, et al., 1981; Komatsu et al., 1982, Walport et al., 2004). Although individuals with congenital complement deficiency constitute only a small cohort of all human SLE, this strong association nonetheless implicates an important role for complement in the regulation of SLE (Paul and Carroll, 2002). However, despite SLE being a highly severe disease, there is no effective cure for it to date and the development of effective therapeutic modalities, which has progressed disappointingly slowly, represents an immense unmet challenge largely in part due to lack of a single hypothesis that could fully justify the mechanistic underpinning of SLE. However, with the ever-improving sophistication in molecular biology and genetic engineering, the time is ripe for methods to reconstitute or to correct C1q deficiency, in order to prevent associated diseases such as SLE and Rheumatoid arthritis. The recent report (Sun et al., 2009; Alexander et al., 2009) of reversal of multiorgan dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus after mesenchymal stem cell transplantation is indeed a step in the right trajectory.

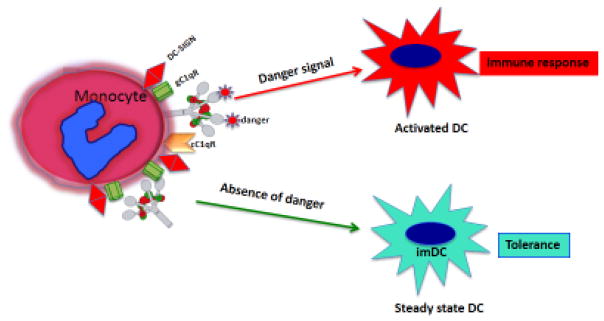

As described above, C1q is unique in that it is synthesized extra-hepatically predominantly by antigen presenting cells. This in turn suggests that C1q (and components of C1) expressed on or secreted by monocyte/DCs could potentially serve as a molecular sensor that discriminates danger from non-danger signals (Ghebrehiwet, 2014). In the steady state (Fig. 2) C1q can regulate early processes that maintain cells in the monocyte or monocyte-like phenotype, (innate immunity), whereas recognition of “danger” together with activation of the classical pathway in situ imparts a signal that drives monocytes toward the DC lineage (adaptive immunity). Deficiency of C1q is therefore postulated to disrupt this equilibrium. In support of this hypothesis is the finding that C1q senses and binds danger-associated molecular patterns including well-recognized “eat me” signals such as self DNA and phosphatidylserine (Paîdassi et al. 2008, Nauta et al., 2004, Ogden et al., 2001), which are the first structures exposed on the apoptotic cell surface [Casciola, et al., 1994; Korb and Ahearn, 1997). Interestingly, the majority of the circulating antibodies (Abs) in SLE are also against intracellular antigens (nuclear or cytoplasmic), with antibody to dsDNA being the hallmark of SLE (Paul and Carrol, 2002). Therefore C1q–predominantly through its receptors–is believed to serve as a molecular bridge between the phagocytic cell and the apoptotic debris to be cleared. However, although its role in the clearance of self-waste may justify the premise that deficiency of C1q could potentially lead to an overload of immunogenic self-antigens resulting in SLE, a growing body of evidence, including our own, suggests that locally secreted C1q is a powerful molecular “switch’ that, in the absence of ‘danger signal”, keeps dendritic cells (DC) in a steady state [Hosszu et al 2014, The et al., 2011). Since DCs drive pathogenic events in autoimmune diseases locally synthesized C1q/C1 by monocytes/DC, could play a critical role in modulating DC differentiation and function and that lack of C1q therefore results in defective regulation of B-cell tolerance and/or distorted cytokine production.

Fig 2.

C1q as a molecular orchestrator of dendritic cell function. The schematic diagram shows the hypothesized role for C1q in the presence and absence of danger signal. In the presence of danger, C1q expressed on monocytes or immature dendritic cells (imDCs) cells recognizes and binds antigen via its globular head domains, setting in motion the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, which in turn induce the transition of steady state or tolerogenic dendritic cells (tolDCs) to activated DCs, which launch an immune response. In the absence of danger however C1q keeps imDCs in steady state probably with the help of secreted C1q and gC1qR.

The major question is therefore: Is C1q uniquely sanctioned to modulate and regulate self-antigens and if so, what is the mechanism? First, C1q has two functional domains: the cC1q and gC1q domains each of which “preferentially” binds to cC1qR and gC1qR respectively. Second, we have two types of C1q: membrane-anchored and locally secreted soluble C1q, each of which in turn may have different even opposing functions. Third, in experiments that were performed more than 20 years ago (Chen et al, 1994), it was shown that “antigen-free C1q” binds to T cells in a manner that was rapid and saturable with mitogen induced cells binding 40–50% more than their unstimulated counterparts indicating C1qRs are upregulated by mitogens. More importantly, when the mitogen-induced T-cells were cultured in the presence of C1q, there was a significant inhibition of cell proliferation, which suggested that soluble C1q was an anti-proliferative molecule. What was interesting however, is that 50% of the bound C1q was rapidly internalized and remained tightly bound with detergent insoluble material, from which it could not be extracted (Chen et al., 1994). Since, both gC1qR and cC1qR are multicompartmental molecules located both inside and outside the cell, one of our working hypopthesis is that monocytes/DCs, which synthesize, secrete as well as express membrane-anchored C1q may capture antigens via the globular heads, and this “antigen-loaded C1q” is internalized relaying the antigen to either intracellular gC1qR or cC1qR. The receptor bound antigen in turn could get relocated to the cell surface, where T or B cells recognize it. This mechanism would be similar to the recycling of the DC-SIGN/HIV or DC-SIGN/hepatitis C virus complex to the cell surface after initial entry of the virus by binding to DC-SIGN (van den Berg and Geijtenbeek, 2013). Interestingly, on monocytes/DCs, C1q, gC1qR and DC-SIGN form a trimolecular complex (Hosszu et al, 2012) and both the HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus also bind to gC1qR (Pednekar et al., 2016) in addition to DC-SIGN.

Therefore on the basis of the available data and our own findings [Hosszu et al., 2009], we believe that membrane anchored C1q (Fig. 2) induces inflammatory responses by binding through its gC1q to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and to modified self-antigens (DAMPs), activates the classical pathway with deposition of C4d. This in turn results in either stimulation of phagocytic cells through interactions via its cC1q domain with cC1qR after it is released from the cell membrane with its “antigen cargo”, or is internalized and then recycled as described above. A normal response to “danger” would therefore involve upregulation of cC1qR on immature DC (imDC) to ensure uptake of danger patterns with the globular heads of C1q (Vandiver et al. 2002; Botto, 1998). Others and we have shown the upregulation of cC1qR and gC1qR as well as C1q in imDCs and this expression is reduced upon DC maturation (Vegh et al, 2003; Castellano et al, 2004). In the context of inflammatory stimuli, DC maturation would ensue allowing adaptive immune responses against the initiating agent. On the other hand, C1q that is free of antigenic cargo–(i.e. in the absence of danger ligand)–does not support full commitment to the DC lineage, as represented during steady state. During normal physiology, return to steady state levels of C1q/C1qR on monocytes and/or DC precursors would resume once pathogen/danger has been cleared. In contrast to soluble C1q released from imDCs, monocyte-expressed C1q would function to retrieve Ag in the extracellular space, giving the first signal for the monocyte to migrate to lymphoid organs and differentiate into mature DC. Therefore C1q on monocyte-DC precursors reflects a novel regulatory mechanism to sustain innate immune functions. We believe that the role of unoccupied C1q could be to provide active protection from autoimmunity by “silencing’” or regulating autoreactive immune cells, its absence or defective expression could lead to a loss of peripheral tolerance as a cumulative result of cytokine-induced negative signaling combined with impaired or diminished apoptotic cell clearance.

Similar to the suppressive effect of C1q on T cells acting through gC1qR/C1q interactions (Chen et al., 1994; Kittleson et al., 2000; Yao et al., 2004), we hypothesize that the regulatory effects of C1q on monocyte/DC precursors may occur via engagement of gC1q. Due to the swift nature of the monocyte to DC transition, regulatory effects of a C1q/C1qR system would occur within a narrow time frame and would be influenced by the microenvironment (steady state, infection or inflammation). The dichotomy of the two apparently opposing roles of C1q, in turn are due to the binding orientation of C1q (“heads” versus “tails”), the specific receptors engaged (gC1qR versus cC1qR) on the cell surface, and the affinity of molecular patterns for gC1q. Therefore preferential engagement of distinct regions of C1q (gC1q vs. cC1q) takes place during different stages of DC growth. Such duality of function would be very similar to the role of surfactant proteins (Sp)-A and Sp-D in the lung, which help maintain the steady state environment via binding to the ITIM-containing SIRPα through their globular head domains or initiate ingestion and pro-inflammatory responses through the collagenous tails and cC1qR/CD91 [Gardai et al., 2003]. Because of its pleiotropic functions, including its ability to bind various receptors, stimulate the generation of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in a an autocrine and paracrine manner, C1q has the ability to control the activation thresholds of both T cells and DCs.

5. Concluding remarks

Although the list of pathological conditions C1q is postulated to trigger and/or exacerbate is increasing with particularly strong association emerging in cancer (Hong et al. 2009; Peerschke and Ghebrehiwet, 2012; Bulla et al, 2016), we focus here on the role of C1q in SLE as a prototype for autoimmune diseases. The involvement of C1q in the development of SLE has been known for many years. However, its role is still not clearly understood and research to unravel its function has singularly focused on the premise that C1q deficiency results in a defective or inefficient removal of self-waste providing therefore persistent high loads of potentially immunogenic self antigens that break tolerance and induce autoimmunity (Lieu et al., 2004). Implicit in this hypothesis is the notion that C1q–primarily through C1q receptors (C1qRs)–is the principal mediator of apoptotic cell uptake, which certainly is not. While there is evidence which shows that C1q undoubtedly plays an important role (Païdassi et al., 2008; Ogden et al., 2001; Clarke et al., 2015), a biological process such as removal of apoptotic debris is too critical for host survival and therefore multiple ligand-receptor combinations do fortunately exist to ensure that proper disposal of self-waste is accomplished even in the absence of C1q. An alternate hypothesis is that C1q secreted by and/or membrane anchored on monocyte/DCs not only keeps DCs in an immature phenotype, but also determines the activation thresholds of B and T cells and that C1q deficiency causes incomplete maintenance of peripheral tolerance (Ghebrehiwet and Peerschke, 2004). While the two hypotheses may in the end be concatenated, the latter hypothesis does provide a novel approach to address this biological conundrum, and may also explain why the classical pathway components–C1q, C1r, C1s, C4 and C2–are implicated in SLE. Thus, while C1q–especially one expressed on circulating monocytes or DCs–could provide active protection from autoimmunity by either silencing signals that would ensure that DCs are kept in a steady state in the absence of danger signal, or by regulating autoreactive immune cells, its absence could lead to a loss of peripheral tolerance as a cumulative result of impaired apoptotic cell clearance in conjunction with negative signaling. The finding, that C1q arrests DCs in an immature phenotype (imDCs) in the absence of danger signal also seems to corroborate this hypothesis [Hosszu et al, 2009]. To date there is no effective therapy for SLE and the available treatment options are primarily systemic immunosuppressive agents with deleterious side effects. However, as new pathogenetic pathways are unraveled, more specific and targeted therapeutic approaches could be developed to block critical upstream or downstream steps of the disease rather than the systemic approach available to date. Another approach would be to reconstitute the specific deficiency through stem cells that are engineered to carry the defective gene.

Highlights.

Monocyte/dendritic cell (DC) expressed C1q is a molecular sensor of danger

Antigen---free C1q keeps DCs in a tolerogenic phenotype.

Danger---loaded C1q initiates DC transition from steady state to immune response

Acknowledgments

This work included in this article was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01 AI 060866 and R01 AI-084178).

Abbreviations

- gC1qR

receptor for the globular “heads” of C1q

- cC1qR

receptor for the collagen tail of C1q

- DC

dendritic cells

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no financial or personal interests to disclose.

Submission declaration: This article has not been published previously elsewhere although some background information included in the paper is widely available elsewhere. The authors included in this paper have contributed significantly to the overall knowledge and information included in this article.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agostinis C, Bulla R, Tripodo C, Gismondi A, Stabile H, Bossi F, Guarnotta C, Garlanda C, De Seta F, Spessotto P, Santoni A, Ghebrehiwet B, Girardi G, Tedesco F. An alternative role of C1q in cell migration and tissue remodelling: contribution to trophoblast invasion and placental development. J Immunol. 2010;185:4420–4429. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander T, Thiel A, Rosen O, Massenkeil G, Sattler A, Kohler S, Mei H, Radtke H, Gromnica-Ihle E, Burmeister GR, Arnold R, Radbruch A, Hiepe F. Depletion of autoreactive immunologic memory followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with refractory SLE induces long-term remission through de novo generation of a juvenile and tolerant immune system. Blood. 2009;113:214–223. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-168286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alper CA, Johnson AM, Bertch AG, Moore FD. Human C’3: evidence for the liver as the primary site of synthesis. Science. 1969;163:286–288. doi: 10.1126/science.163.3864.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensa JC, Reboul A, Colomb MG. Biosynthesis in vitro of complement subcomponents C1q, C1s and C1 inhibitor by resting and stimulated human monocytes. Biochem J. 1983;216:385–392. doi: 10.1042/bj2160385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg AH, Combs TP, Du X, Brownlee M, Scherer P. The adipocyte-secreted protein Acrp30 enhances hepatic insulin action. Nat Med. 2001;7:947–953. doi: 10.1038/90992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler B, Greenwald D, Hulmes JD, Chang M, Pan YC, Mathison J, Ulevitch R, Cerami A. Identity of tumour necrosis factor and the macrophage-secreted factor cachectin. Nature. 1985;316:552–554. doi: 10.1038/316552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RA, Rauch CT, Kozlosky CJ, Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Wolfson MF, Castner BJ, Stocking KL, Reddy P, Srinivasan S, Nelson N, Boiani N, Schooley KA, Gerhart M, Davis R, Fitzner JN, Johnson RS, Paxton RJ, March CJ, Cerretti DP. A metalloproteinase disintegrin that releases tumour-necrosis factor-alpha from cells. Nature. 1997;385:729–733. doi: 10.1038/385729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky-Doyle B, Leonhard KR, Reid KBM. Circular-dichroism and electron microscopy studies of human subcomponent C1q before and after limited proteolysis by pepsin. Biochem J. 1976;159:279–286. doi: 10.1042/bj1590279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulla R, Agostinis C, Bossi F, Rizzi L, Debeus A, Tripodo C, Radillo O, DeSeta F, Ghebrehiwet B, Tedesco F. Decidual endothelial cells express surface bound C1q as a molecular bridge between endovascular trophoblast and decidual endothelium. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:2629–2640. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulla R, Tripodo C, Rami D, Ling GS, Agostinis C, Guarnatta C, Zorzet S, Durigutto P, Botto M, Tedesco F. C1q acts in tumour microenvironment as a cancer-promoting factor independently of complement activation. Nat Comm. 2016 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botto M, Dell’Angola C, Bygrave AE, Thompson EM, Cook HT, Petry F, Loos M, Pandolfi PP, Walport MJ. Homozygous C1q deficiency causes glomerulonephritis associated with multiple apoptotic bodies. Nat Genet. 1998;19:56–59. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcott MA, Muller-Eberhard HJ. C1q protein of human complement. Biochemistry. 1972;11:3443–3450. doi: 10.1021/bi00768a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casciola-Rosen LA, Anhalt G, Rosen A. Autoantigens targeted in systemic lupus erythematosus are clustered in two populations of surface structures on apoptotic keratinocytes. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1317–1330. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano G, Woltman AM, Schena FP, Roos A, Daha MR, van Kooten C. Dendritic cells and complement: at the crossroad of innate and adaptive immunity. Molec Immunol. 2004a;41:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano G, Woltman AM, Nauta AJ, Roos A, Trouw LA, Seelen M, Schena FB, Daha MR, van Kooten C. Maturation of dendritic cells abrogates C1q production in vivo and in vitro. Blood. 2004b;103:3813–3820. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Gaddipati S, Volkman DJ, Peerschke EIB, Ghebrehiwet B. Human T cells possess specific receptors for C1q: Role in activation & proliferation. J Immunol. 1994;153:1430–1440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke EV, Weist BM, Walsh CM, Tenner AJ. Complement protein C1q bound to apoptotic cells suppresses human macrophage and dendritic cell-mediated TH17 and TH1 cell subset proliferation. JLeuk Biol. 2015;97:147–160. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3A0614-278R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colten H. Ontogeny of the human complement system: In vitro biosynthesis of individual complement components by fetal tissues. J Clin Invest. 1971;51:725–370. doi: 10.1172/JCI106866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colten HR, Borsos T, Rapp HJ. In vitro synthesis of the first component of complement by guinea pig small intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1966;56:1158–1163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.56.4.1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colten HR, Gordon JM, Borsos T, Rapp HJ. Synthesis of the first component of human complement in vitro. J Exp Med. 1968a;128:595–604. doi: 10.1084/jem.128.4.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colten HR, Gordon JM, Rapp HJ, Borsos T. Synthesis of the first component of guinea pig complement by columnar epithelial cells of the small intestine. J Immunol. 1968b;100:788–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colten HR. Biosynthesis of complement. Adv Immunol. 1976;22:67–118. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60548-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouet C, Reboul A. Biosynthesis of C1r and C1s subcomponents. Behring Inst Mitt. 1989;84:80–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duus K, Hansen EW, Tacvnet P, Fratchet P, Arlaud GJ, Thielens NM, Houen G. Direct interaction between Cd91 and C1q. FEBS J. 2010;277:3526–3537. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber K, Cheung G, Mitchell D, Wallis R, Weihe E, Schwaeble W, Kettenmann H. C1q, the recognition subcomponent of the classical pathway of complement, drives microglial activation. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:644–652. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Tonnesen MG, Peerschke EIB, Ghebrehiwet B. Cooperation of C1q receptors and integrins in C1q-mediated endothelial cell adhesion and spreading. J Immunol. 2002;169:2441–2448. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson JS, Voelker DR, McCormack FX, Schlesinger LS. Surfactant protein D binds to Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli and lipoarabinomannan via carbohydrate-lectin interactions resulting in reducedphagocytosis of the bacteria by macrophages. Journal of immunology. 1999;163:312–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser DA, Pisalyaput K, Tenner AJ. C1q enhances microglial clearance of apoptotic neurons and neuronal blebs, and modulates subsequent inflammatory cytokine production. J Neurochem. 2010;112:733–743. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06494.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaboriaud C, Païdassi H, Frachet P, Tacnet-Delorme P, Thielens NM, Arlaud GJ. C1q: A versatile pattern recognition molecule and sensor of altered self. Collagen-related lectins in innate immunity. In: Kilpatrick D, editor. Research Signpost. Vol. 81. 2007. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gardai SJ, Xiao YQ, Dickinson M, Nick JA, Voelker DR, Greene KE, Henson PM. By binding SIRPalpha or calreticulin/CD91, lung collectins act as dual function surveillance molecules to suppress or enhance inflammation. Cell. 2003;115:13–23. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00758-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebrehiwet B, Habicht GS, Beck G. Interaction of C1q with its receptor on cultured cell lines induces an anti-proliferative response. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;54:148–160. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(90)90014-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebrehiwet B, Peerschke EIB. Role of C1q and C1q receptors in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. In Complement in Autoimmunity. In: Tsokos GC, editor. Current Dir Autoimmun. Vol. 7. Basel; Karger: 2004. pp. 87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebrehiwet B, Hosszu KK, Valentino A, Peerschke EIB. The C1q family of proteins: insights into the emerging non-traditional functions. Frontiers Inn Immun. 2012;3:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebrehiwet B, Hosszu KK, Valentino A, Peerschke EIB. Monocyte expressed macromolecular C1 and C1q receptors as molecular sensors of danger: implication in SLE. Frontiers in Immunol. 2014;5:278. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00278. eCollection 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebrehiwet B, Kaplan AP, Joseph K, Peerschke EIB. The complement and contact activation systems: partnership in pathogenesis beyond angioedema. Immunol Rev. 2016;274:281–289. doi: 10.1111/imr.12469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulati P, Lemercier C, Guc D, Lappin D, Whaley K. Regulation of the synthesis of C1 subcomponents and C1-inhibitor. Behring Inst Mitt. 1993;93:196–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmskov U, Thiel S, Jensenius JC. Collections and ficolins: humoral lectins of the innate immune defense. Annual Review of Immunology. 2003;21:547–578. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.140954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Q, Sze CI, Lin SR, Lee MH, He RY, Schultz L, Chang JY, Chen SJ, Boackle RJ, Hsu LJ, Chang NS. Complement C1q activates tumor suppressor WWOX to induce apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(6):e5755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosszu KK, Santiago-Schwarz F, Peerschke EI, Ghebrehiwet B. Evidence that a C1q/C1qR system regulates monocyte-derived dendritic cell differentiation at the interface of innate and acquired immunity. Innate Immun. 2009;16:115–127. doi: 10.1177/1753425909339815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosszu KK, Santiago-Schwarz F, Peerschke EIB, Ghebrehiwet B. Evidence that a C1q/C1qR system regulates monocyte-derived dendritic cell differentiation at the interface of innate and acquired immunity. Inn Immun. 2010;16:115–127. doi: 10.1177/1753425909339815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosszu KK, Valentino A, Ji Y, Matkovic M, Pednekar L, Rehage N, Tumma N, Peerschke EI, Ghebrehiwet B. Cell surface expression and function of the macromolecular C1 complex on the surface of human monocytes. Front Immunol. 2012;3:38. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosszu KK, Valentino A, Vinayagasundaram U, Vinayagasundaram R, Joyce MG, Ji Y, Peerschke EI, Ghebrehiwet B. DC-SIGN, C1q and gC1qR form a trimolecular complex on the surface of monocyte-derived immature dendritic cells. Blood. 2012;120:1228–1236. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-369728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul M, Loos M. C1q, the collagen-like subcomponent of the first component of complement C1, is a membrane protein of guinea pig macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 1993a;23:2166–2174. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul M, Loos M. The Fc-recognizing collagen-like C1q molecule is a putative type II membrane protein on macrophages. Behring Inst Mitt. 1993b;93:171–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishore U, Kojouharova MS, Reid KBM. Recent progress in the understanding of the structure-function relationships of the globular head region of C1q. Immunobiol. 2002;205:355–364. doi: 10.1078/0171-2985-00138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishore U, Ghai R, Greenhough TJ, Shrive AK, Bonifati DM, Gadjeva MG, Walters P, Kojouharova MSm, Chakraborty T, Agrawal A. Structural and functional anatomy of the globular domain of complement protein C1q. Immunol Lett. 2004;95:113–128. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittlesen DJ, Chianese-Bullock KA, Yao ZQ, Braciale TJ, Hahn YS. Interaction between complement receptor gC1qR and hepatitis C virus core protein inhibits T-lymphocyte proliferation. J Clin Immunol. 2000;106:1239–1249. doi: 10.1172/JCI10323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobel HR, Villiger W, Isliker H. Chemical analysis and electron microscopy studies of human C1q prepared by different methods. Eur J Immunol. 1975;5:78–82. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830050119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kölble K, Reid KBM. The genomics of soluble proteins with collagenous domains: C1q, MBL, SP-A, SP-D, Conglutinin and CL-43. Behring Inst Mitt. 1993;93:81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu A, Komazawa M, Murakami M, Nagaki Y. A case of selective C1q-deficiency with SLE-like symptoms. J Jap Pediatr Soc. 1982;86:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Korb LC, Ahearn JM. C1q binds directly and specifically to surface blebs of apoptotic human keratinocytes: complement deficiency and systemic lupus erythematosus revisted. J Immunol. 1997;158:4527–4529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman M, Joiner K, Ezekowitz RA. The human mannose-binding protein functions as an opsonin. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1733–1745. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.5.1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahita RG. Systemic lupus erythematosus. 3. Academic Press; San Diego, CA; New York, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Liu C-C, Navratil JS, Sabine JM, Ahearn JM. Apoptosis, complement and systemic lupus erythematosus: a mechanistic view. Complement in Autoimmunity. In: Tsokos GC, editor. Current Dir Autoimmun. Vol. 7. Basel; Karger: 2004. pp. 49–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozada C, Levin RI, Huie M, Hirschhorn R, Naime D, Whitlow M, Recht PA, Golden B, Cronstein B. Identification of C1q as the heat-labile serum cofactor required for immune complexes to stimulate endothelial expression of the adhesion molecules E-selectin and intracellular and vascular cell adhesion molecules 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8378–8382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch NJ, Willis CL, Nolan CC, Roscher S, Fowler MJ, Weihe E, Ray DE, Schwaeble WJ. Microglial activation and increased synthesis of complement component C1q precedes blood-brain barrier dysfunction in rats. Mol Immunol. 2004;40:709–716. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens HA, Zuurman MW, de Lange AHM, Nolte IM, van der Steege G, Navis GJ, Kallenberg CGM, Seelen MA, Biji M. Analysis of C1q polymorphisms suggests association with systemic lupus erythematosus serum C1q and CH50 levels and disease severity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:715–720. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.085688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita M. Ficollins: Complement activating lectins involved in innate immunity. Journal of Innate Immunity. 2010;2:24–32. doi: 10.1159/000228160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamae Y, Mochizuki S, Shimoda M, Ohara K, Abe H, Yamashita S, Kazuno S, Ohtsuka T, Ochiai H, Kitagawa Y, Okada Y. ADAM28 is expressed by epithelial cells in human normal tissues and protects from C1q-induced cell death. The FEBS J. 2016;283:1574–1594. doi: 10.1111/febs.13693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauta AJ, Castellano G, Xu G, Woltman AM, Borrias MC, Daha MR, van Kooten C, Roos A. Opsonization with C1q and mannose binding lectin targets apoptotic cells to dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;41:3044–3050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino H, Shibuya K, Nishida Y, Mushimoto M. Lupus erythematosus-like syndrome with selective C1q complete deficiency of C1q. Ann Intern Med. 1981;95:322–324. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-95-3-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CA, de Cathelineau A, Hoffmann PR, Braton D, Ghebrehiwet B, Fadok VA, Henson PM. C1q and mannose binding lectin (MBL) engagement of cell surface calreticulin and CD91 initiates macropinocytosis and uptake of apoptotic cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:781–795. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Old LJ. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) Science. 1985;230:630–632. doi: 10.1126/science.2413547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peerschke EIB, Smyth SS, Teng E, Dalzell M, Ghebrehiwet B. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells possess binding sites for the globular domains of C1q. J Immunol. 1996;157:4154–4158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peerschke EI, Ghebrehiwet B. cC1qR/CR and gC1qR/p33: Observations in cancer. Mol Immunol. 2014;2014–61:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Païdassi H, Tacnet P, Garlatti V, Darnault C, Ghebrehiwet B, Gaboriaud C, Arlaud GJ, Frachet P. C1q binds phosphatidylserine and likely acts as a multiligand bridging molecule in apoptotic cell recognition. J Immunol. 2008;18:2329–2338. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul E, Carroll MC. In: Complement and Complement receptors in autoimmunity: The Molecular Path of Autoimmune Diseases. 2. Theofilopoulos AN, Bona CA, editors. Taylor & Francis; NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pednekar L, Valentino A, Ji Y, Tumma N, Valentino C, Kadoor A, Hosszu KK, Ramadass M, Kew RR, Kishore U, Peerschke EI, Ghebrehiwet B. Identification of the gC1qR sites for HIV-1 viral envelope protein gp41 and the HCV core protein: implication in viral-specific pathogenesis and therapy. Mol Immunol. 2016;74:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering MC, Botto M, Taylor PR, Lachmann PJ, Walport MJ. Systemic lupus erythematosus, complement deficiency, and apoptosis. Adv Immunol. 2000;76:227–234. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(01)76021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randazzo BP, Dattwyler RJ, Kaplan AP, Ghebrehiwet B. Synthesis of C1 inhibitor (C1-INA) by a human monocyte-like cell line, U937. J Immunol. 1985;135:1313–1319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid KBM, Solomon E. Biosynthesis of the first component of complement by human fibroblasts. Biochem J. 1977;167:647–660. doi: 10.1042/bj1670647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid KBM, Thompson RA. Characterization of non-functional form of C1q found in patients with genetically linked deficiency of C1q activity. Immunol. 1983;20:1117–1125. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(83)90121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid KBM. Molecular cloning and characterization of the complementary DNA and gene coding for the B chain subcomponent C1q of the human complement system. Biochem J. 1985;231:729–35. doi: 10.1042/bj2310729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein DA, Hom S, Ghebrehiwet B, Yin W. Tobacco and e-cigarette products initiate Kupffer cell inflammatory responses. Mol Immunol. 2015;67:652–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schejbel L, Melander Skattum L, Hagelberg S, Ahlin A, Schiller B, Berg S, Gennel F, Truedsson L, Garred P. Molecular basis of hereditary C1q deficiency-revisited: identification of several novel disease-causing mutations. Genes and Immunity. 2011;12:626–634. doi: 10.1038/gene.2011.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer PE, Williams S, Fogliano M, Baldini G, Lodish HF. A novel serum protein similar to C1q, produced exclusively in adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26746–26749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedger L, McDermot MF. TNF and TNF receptors: From mediators of cell death and inflammation to therapeutic giants-past, present and future. Cytokine and Growth Fator Rev. 2014;25:453–472. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellar GC, Blake DJ, Reid KBM. Characterization and organization of the genes encoding the A-, B, and C-chains of human complement subcomponent C1q. Biochem J. 1991;274:481–491. doi: 10.1042/bj2740481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer MK, Schwaeble WJ, Post C, Salvati P, Calabresi M, Sim RB, Petry F, Loos M, Weihe E. Complement C1q is dramatically up-regulated in brain microglia in response to transient global cerebral ischemia. J Immunol. 2000;164:5446–5452. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro L, Scherer PE. The crystal structure of a complement-1q family of protein suggests an evolutionary link to tumor necrosis factor. Curr Biol. 1998;8:335–338. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton E, Yonemasu K, Stroud RM. Ultrastructure of the human complement component C1q. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:65–68. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skok J, Solomon E, Reid KBM, Thompson RA. Distinct genes for fibroblast and serum C1q. Nature. 1981;292:549–551. doi: 10.1038/292549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J, Ahmed A, Girardi G. Role of complement component C1q in the onset of preeclampsia in mice. Hypertension. 2011;58:716–724. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.175919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegert M, Bock M, Ttrendelenburg M. Clinical presentation of human C1q deficiency: How much of lupus? Mol Immunol. 2015;67:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan AH, Barres BA, Stevens B. The complement system: an unexpected role in synaptic pruning during development and disease. Ann Rev Neuroscince. 2012;35:369–389. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens B, Allen NJ, Vazquez LE, Howell GR, Christopherson KS, et al. The classical complement cascade mediates CNS synapse elimination. Cell. 2007;131:1164–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Akiyama K, Zhang H, Yamaza T, Hou Y, Zhao S, Xu T, Le A, Shi S. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation reverses multiorgan dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1421–1432. doi: 10.1002/stem.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svehag SE, Manheim L, Bloth B. Ultrastructure of human C1q protein. Nature (London) New Biol. 1972;238:117. doi: 10.1038/newbio238117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartaglia LA, Weber RF, Figari IS, Reynolds C, Palladino MAJ, Goeddel DV. The two different receptors for tumor necrosis factor mediate distinct cellular responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:9292–9296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.9292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo BHD, Bobryshev YV, The BK, Wong SH, Lu J. Complement C1q production by osteoclasts and its regulation of osteoclast development. Biochem J. 2012;447:229–237. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The BK, Yeo JG, Chern LM, Lu J. C1q regulation of dendritic cell development from monocytes with distinct cytokine production and T cell stimulation. Mol Immunol. 2011;48:1128–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenner AJ, Volkin DB. Complement subcomponent C1q secreted by cultured human monocytes has a subunit structure identical with that of serum C1q. Biochem J. 1986;233:451–458. doi: 10.1042/bj2330451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treede I, Braun A, Jeliaskova P, Giese T, Füllekrug J, Griffiths G, Stremmel W, Ehehalt R. TNFa-induced up-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines is reduced by phosphatidylcholine in intestinal epithelial cells. BMC Gastroenterology. 2009;9:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trouw LA, Daha N, Kurreeman FAS, Goulielmos GN, Westra HJ, Zhernakova A, Franke L, Stahl EA, Levahrt EWN, Stoeken-Rijsbergen G, Verdujin W, Ross A, Li Y, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Huizinga TWJ, Toes REM. Genetic variants in the region of the C1q genes are associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical Exp Immunol. 2013;173:76–83. doi: 10.1111/cei.12097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg RH, Faber-Krol MC, Sim RB, Daha MR. The first subcomponent of complement C1q triggers the production of IL-6, IL-8, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 by human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Immunol Lett. 1998;161:6924–6930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg LM, Geijtenbeek TB. Antiviral immune responses by human langerhans cells and dendritic cells in HIV-1 infection. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2013;762:45–70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-4433-6_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandivier RW, Ogden CA, Fadok VA, Hoffmann PR, Brown KK, Botto M, Walport MJ, Fisher JH, Henson PM, Greene KE. Role of surfactant proteins A, D, and C1q in the clearance of apoptotic cells in vivo and in vitro: Calreticulin and CD91 as a common collectin receptor complex. J Immunol. 2002;169:3978–3986. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schaarenburg RA, Suurmond J, Habets KLL, Brouwer MC, Wouters D, Kurreeman FAS, Huizinga TWJ, Toes REM, Trouw LA. The production and secretion of complement component C1q by human mast cells. Mol Immunol. 2016;78:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vegh Z, Goyarts EC, Rozengarten K, Mazumder A, Ghebrehiwet B. Maturation-dependent expression of C1q binding proteins on the cell surface of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2003;3:345–357. doi: 10.1016/S1567-5769(02)00234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walport MJ, Davies KA, Botto M. C1q and systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunobiol. 1998;199:265–285. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(98)80032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis WI, Drickamer K, Hendrickson WA. Structure of a C-type mannose-binding protein complexed with an oligosaccharide. Nature. 1992;360:127–134. doi: 10.1038/360127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong GW, Wang J, Hug C, Tsao T-S, Lodish HF. A family of Acrp30/adiponectin structural and functional paralogs. Proced Natl Acad Sci (USA) 2004;101:10302–10307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403760101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Kuzmenko A, Wan S, Schaffer L, Weiss A, Fisher JH, Kim KS, McCormack FX. Surfactant proteins A and D inhibit the growth of Gram-negative bacteria by increasing membrane permeability. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1589–1602. doi: 10.1172/JCI16889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao ZQ, Eisen-Vandervelde A, Waggoner AN, Cale EM, Hahn YS. Direct binding of hepatitis C virus core protein to gC1qR on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells leads to impaired activation of LCK and Akt. J Viorol. 2004;78:6409–6419. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6409-6419.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]