Abstract

Background

Opioid analgesic and benzodiazepine use in individuals with opioid use disorders (OUDs) can increase the risk for medical consequences and relapse. Little is known about rates of use of these medications or prescribing patterns among communities of prescribers.

Aims

To examine rates of prescribing to Medicaid-enrollees in the calendar year after an OUD diagnosis, and to examine individual, county, and provider community factors associated with such prescribing.

Methods

We used 2008 Medicaid claims data from 12 states to identify enrollees diagnosed with OUDs, and 2009 claims data to identify rates of prescribing of each drug. We used social network analysis to identify provider communities and multivariate regression analyses to identify patient, county, and provider community level factors associated with prescribing these drugs. We also examined variation in rates of prescribing across provider communities.

Results

Among Medicaid-enrollees identified with an OUD, 45% filled a prescription for an opioid analgesic, 37% for a benzodiazepine, and 21% for both in the year following their diagnosis. Females, older individuals, individuals with pain syndromes, and individuals residing in counties with higher rates of poverty were more likely to fill prescriptions. Prescribing rates varied substantially across provider communities, with rates in the highest quartile of prescribing communities over 2.5 times the rates in the lowest prescribing communities.

Discussion

Prescribing opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines to individuals diagnosed with OUDs may increase risk of relapse and overdose. Interventions should be considered that target provider communities with the highest rates of prescribing and individuals at highest risk.

Keywords: Opioid use disorders, benzodiazepines, opioids, social network analysis, prescribing behavior, Medicaid

Opioid use disorders1 pose a significant public health problem, affecting an estimated two million people in the United States.2 In just one decade, there was a 48% increase in the number of opioid analgesics prescribed, a 368% increase in the amount of opioid analgesics received among individuals filling a prescription, and a quadrupling in the number of fatal overdoses due to opioid analgesics.3,4 Opioid-related emergency department visits more than doubled, rising from 22 per 100,000 in 2004 to 55 per 100,000 in 2011. In 2011, there were more than 1.24 million emergency department visits involving non-medical use of pharmaceuticals and pain relievers.5 Opioid-related mortality now represents the leading cause of injury deaths in the United States, exceeding deaths from suicide, gunshot wounds, and motor vehicle accidents.6 The annual societal costs of opioid abuse, including overdose deaths, lost productivity, criminal justice costs, and individual health care costs, is an estimated $55.7 billion.7,8

Opioid use disorders are considered chronic medical illnesses,9 and individuals with such disorders are prone to relapse due to a host of environmental, patient, and provider factors.10–12 For example, exposing an individual with an opioid use disorder to an opioid may increase the risk of relapse; furthermore, exposure to both opioids and benzodiazipines may complicate treatment and increase overdose risk among patients with opioid use disorder.10,13 Experts therefore recommend caution in prescribing opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines to individuals with a history of opioid use disorder.14

There is a paucity of data, however, regarding the frequency with which individuals previously diagnosed with opioid use disorders are prescribed opioid analgesics or benzodiazepines. Nor is there information about whether such prescribing, if it occurs, might be concentrated among certain physician groups, who may develop norms about prescribing practices15 and medication choices16,17 that differ from the norms of physicians outside those groups.

Influences on prescribing practices and medication choices are not limited to physicians in the same practice;18,19 such influences are often observed among physicians who share and refer patients.20 But the prescribing patterns of such physician groups, hereafter referred to as a provider community, may be particularly germane for individuals with opioid use disorders. These populations have higher rates of physical and mental health comorbidities than many other populations;21–24 as a result, multiple prescribers need to know an individual’s history in order to coordinate treatment. Awareness and coordination among prescribers may be particularly challenging in the face of regulations restricting the sharing of substance abuse treatment records.25

To better understand these issues, we examined a multistate cohort of Medicaid-enrollees with opioid use disorders to assess their receipt of opioid analgesics, benzodiazepines, and both together.

Methods

Population

To examine use of opioid analgesic and benzodiazepines among individuals previously diagnosed with an opioid use disorder and to understand how rates of use varied across provider communities, we used Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) claims from 12 states (CT, FL, GA, IL, LA, MA, MD, PA, RI, TX, VT, and WI.) The data was obtained prior to federal redaction of substance use disorder treatment related claims under 42 CFR. The states were selected to represent diversity in regions, populations, and state Medicaid policies regarding the use of buprenorphine and methadone to treat Medicaid-enrollees with opioid use disorders. We used ICD-9 diagnoses on claims submitted in 2008 to identify individuals aged 18–64 with an opioid use disorder and examined their prescriptions for opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines in 2009. The RAND IRB approved the study.

Variables

We used NDC codes in 2009 Medicaid claims to identify prescription opioid users, defined as individuals who filled an opioid analgesic prescription (e.g., oxycodone, hydrocodone) other than buprenorphine during 2009. Benzodiazepine users were defined as individuals who filled a benzodiazepine prescription (e.g., alprazolam, clonazepam) during 2009. Drawing upon an existing algorithm,26 we used ICD codes in services claims (ICD poisoning codes 965.00, 965.01, 965.02, 965.09, E850.0, E850.1, E850.2; and adverse events, defined as both an ICD or HCPCS adverse effect code a) E935.0, E935.1, E935.2, Y45.0 and a relevant symptom code b) 276.4, 292.2, 292.8, 486, 496, 518.81, 518.82, 728.88, 780.0, 780.97, 786.03, 786.05, 786.09, 786.52, 799.0, E950-E959, E962.0, J2310) to identify opioid overdose and poisoning events, and CPT and HCPCS codes to identify opioid-related emergency department use and hospitalization for substance use disorders. We obtained patient age, gender, and race/ethnicity information from Medicaid eligibility data. Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (RUCC)27 were used to categorize county urbanicity. We considered counties or non–metro/non-rural counties adjacent to a metro county as urban; all other counties were considered rural. We controlled for additional contextual factors, such as poverty and violent crime rates, which might influence demand for illicit drugs.28,29

Provider communities

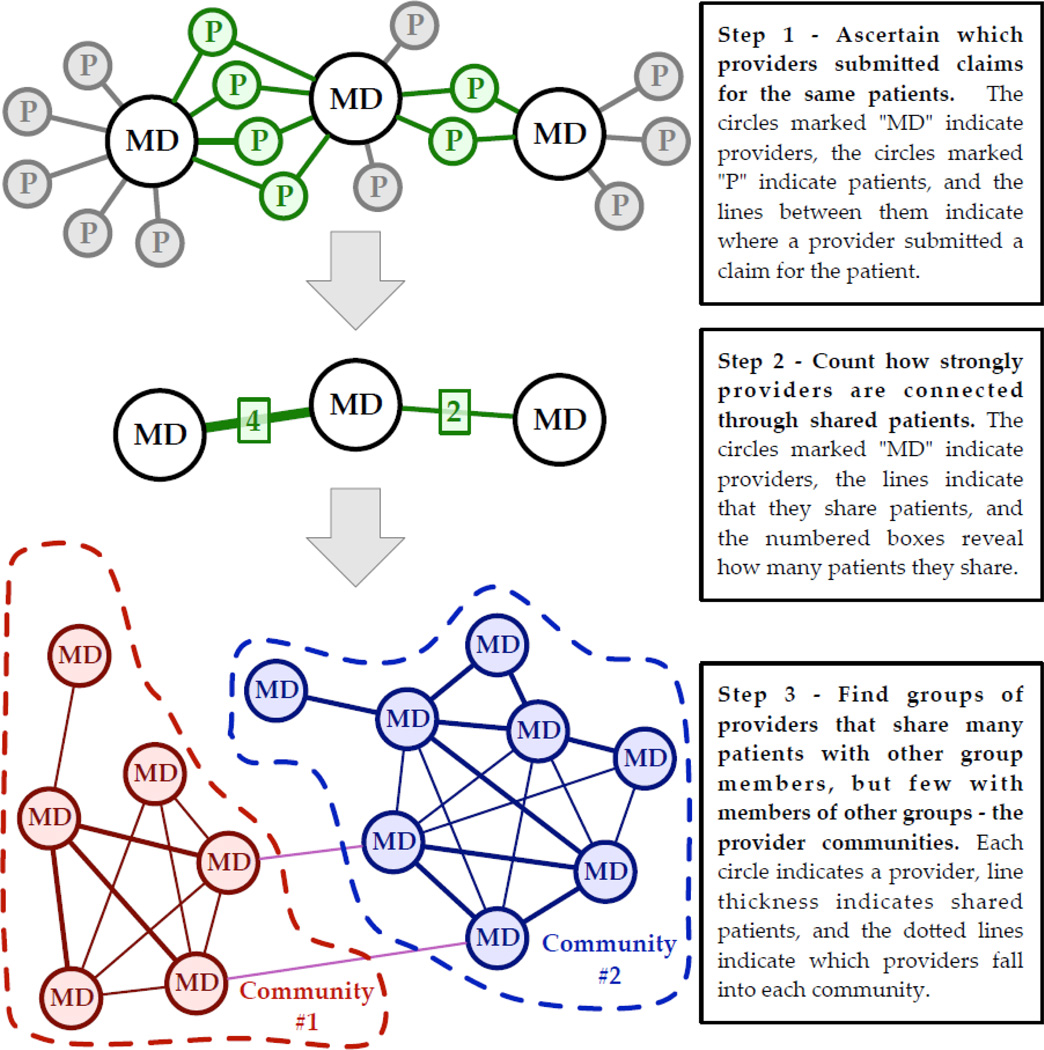

We identified provider communities empirically, based on the frequency with which different providers were treating the same patients, all of whom had been diagnosed with opioid use disorders. To identify provider communities, we conducted formal network analysis community detection methods on Medicaid claims data (Figure 1), which provided information on provider-patient dyads. We defined communities using modularity maximization community detection30,31 in the igraph software package for the R statistical computing language.32 (See technical appendix for further details.) Essentially, this method allowed us to use patient visits to providers to identify groups of providers who were statistically more likely to share the same group of patients.

Figure 1.

Illustration of how provider communities were identified using Medicaid claims

Some sharing of patients between providers occurs naturally because of geographic proximity, while the rest occurs because of other mechanisms such as belonging to the same insurance network. To identify groups of providers that form a community, therefore, we applied a hierarchical approach – identifying clustering due to proximity and then identifying communities within those larger clusters, described in detail in the Appendix. This allowed us to identify provider communities within or across geographic areas.

Analysis

We calculated the percentage of individuals previously identified with opioid use disorders who received opioid analgesics, benzodiazepines, or received both an opioid analgesic and a benzodiazepine during the year (hereafter, combined use). We then estimated a logistic regression model of prescription opioid use as a function of patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, service utilization, number of provider communities involved in treatment, and characteristics of the county in which the patient resides. We estimated similar regressions to examine characteristics associated with receiving benzodiazepines and combined use. All regressions controlled for county characteristics, the total number of providers in the provider communities seen by the patient, the total number of patients in the provider communities seen by the provider, and state fixed effects.

We next determined the percentage of individuals with opioid use disorders in each provider community who were opioid analgesic users, benzodiazepine users, and combined users. To better understand how provider communities differed in the prescribing of these medications, we split the provider communities into quartiles based on the percentage of patients with opioid use disorders receiving each medication. For example, we identified the 25% of provider communities with the highest percentage of individuals with opioid use disorders receiving opioid analgesics, and then the 25% of provider communities with the next higher percentages, etc. We repeated this process for benzodiazepines and for combined prescribing. For each quartile and medication, we calculated the percentage of patients in the provider communities receiving the respective medication(s).

Results

We identified 29,611 Medicaid-enrollees diagnosed with opioid use disorders in 2008 who received Medicaid-reimbursed services in 2009. Individuals were most commonly non-Hispanic white (57%) and non-Hispanic African-American (27%), male (62%), and living in urban counties (90%). Eleven percent had a comorbid mental health disorder, 32% had a substance use disorder other than opioid use disorder, and 62% had a pain disorder diagnosis. Seven percent had opioid overdose or poisoning related emergency department use, and 3% had a substance use disorder related hospitalization.

In 2009, 45% of these individuals filled a prescription for an opioid analgesic, 37% filled a benzodiazepine prescription, and 21% were combined users. Forty percent did not fill a prescription for either medication.

These individuals received treatment from 1081 distinct provider communities in 2009, with each community sharing patients with opioid use disorders at a rate significantly and statistically higher than would occur by chance. By definition, no providers were in more than one provider community. The median number of communities in which a patient saw a provider was 4 (mean 5, SD=4). The median number of providers in a community was 10; the median number of providers in the quartile with the most providers in a community was 14 and was 7 in the quartile with the fewest providers in a community. The median number of patients in a community was 55. The median was 62 in the quartile with the most patients in a community and 44 in the quartile with the fewest patients in a community.

In the multivariate regression (Table 1), opioid analgesic users, benzodiazepine users, and combined users were all more likely to be female and more likely to be diagnosed with a pain syndrome; individuals receiving benzodiazepine and combination users were also more likely to have mental health and non-opioid substance use disorder comorbidities. Opioid analgesic use, benzodiazepine use, and combined use was positively associated with age and the percentage of individuals in a county living below the poverty line and negatively associated with a county’s violent crime rate. Opioid analgesic use was associated with residing in an urban county; this relationship did not exist for the other outcomes we examined. There was substantial state variation in opioid analgesic, benzodiazepine, and combined use. Opioid analgesic use, benzodiazepine use, and combined use were all positively associated with the number of provider communities treating the individual.

Table 1.

Multivariate regression results estimating factors associated with use of opioid analgesics, benzodiazepines, and both combined.

| Characteristic | Opioid OR |

95% CI | p-value | Benzo OR |

95% CI | P-value | Benzo

and Opioid Estimate OR |

95% CI | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics |

||||||||||||

| Age | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.01 | <0.001 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | <0.001 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.02 | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Female | 1.13 | 1.07 | 1.20 | <0.001 | 1.28 | 1.20 | 1.36 | <0.001 | 1.29 | 1.19 | 1.39 | <0.001 |

| Male | ref | |||||||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

| African-American | 0.93 | 0.85 | 1.01 | ns | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.41 | <0.001 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.58 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.91 | 0.82 | 1.02 | ns | 0.54 | 0.48 | 0.61 | <0.001 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.68 | <0.001 |

| Other | 0.95 | 0.85 | 1.06 | ns | 0.74 | 0.66 | 0.82 | <0.001 | 0.77 | 0.67 | 0.89 | <0.001 |

| Substance Use

Disorder Hospitalization |

||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.63 | 1.38 | 1.94 | <0.001 | 2.22 | 1.86 | 2.66 | <0.001 | 2.39 | 2.02 | 2.83 | <0.001 |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

| ED Opioid Utilization | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.24 | 1.10 | 1.40 | <0.001 | 1.24 | 1.10 | 1.39 | <0.001 | 1.36 | 1.20 | 1.55 | <0.001 |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

| Non-opioid substance use disorder comorbidity |

||||||||||||

| Yes | 0.98 | 0.91 | 1.04 | ns | 1.12 | 1.05 | 1.20 | <0.001 | 1.12 | 1.03 | 1.21 | <0.01 |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

| Mental Health comorbidity |

||||||||||||

| Yes | 0.93 | 0.85 | 1.02 | ns | 1.87 | 1.71 | 2.06 | <0.001 | 1.38 | 1.25 | 1.53 | <0.001 |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

| Pain comorbidities | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 3.37 | 3.16 | 3.58 | <0.001 | 1.71 | 1.60 | 1.83 | <0.001 | 3.63 | 3.30 | 3.98 | <0.001 |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

| Number of Provider Communities Seen by Individual |

1.11 | 1.09 | 1.12 | <0.001 | 1.16 | 1.15 | 1.18 | <0.001 | 1.15 | 1.14 | 1.17 | <0.001 |

| County and State Characteristics |

||||||||||||

| Percent of County Living Below Poverty Line |

1.04 | 1.02 | 1.05 | <0.001 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.03 | <0.001 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.05 | <0.001 |

| Violent Crime Rate | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.91 | <0.001 | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.89 | <0.001 | 0.81 | 0.75 | 0.87 | <0.001 |

| Urban/Rural | ||||||||||||

| Urban | 1.13 | 1.01 | 1.28 | <0.05 | 1.09 | 0.96 | 1.23 | ns | 0.10 | 0.94 | 1.28 | ns |

| Rural | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

| State | ||||||||||||

| CT | 1.90 | 1.68 | 2.14 | <0.001 | 1.05 | 0.93 | 1.19 | ns | 1.51 | 1.30 | 1.77 | <0.001 |

| FL | 1.09 | 0.94 | 1.28 | ns | 1.39 | 1.19 | 1.62 | <0.001 | 1.51 | 1.26 | 1.81 | <0.001 |

| GA | 1.34 | 1.01 | 1.77 | <0.05 | 1.68 | 1.26 | 2.24 | <0.001 | 1.59 | 1.17 | 2.15 | <0.01 |

| IL | 1.20 | 1.07 | 1.35 | <0.01 | 2.19 | 1.94 | 2.47 | <0.001 | 2.14 | 1.86 | 2.47 | <0.001 |

| LA | 1.62 | 1.19 | 2.21 | <0.01 | 2.35 | 1.72 | 3.21 | <0.001 | 2.05 | 1.44 | 2.91 | <0.001 |

| MA | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

| MD | 3.14 | 2.71 | 3.64 | <0.001 | 2.32 | 2.00 | 2.69 | <0.001 | 3.16 | 2.64 | 3.77 | <0.001 |

| PA | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.94 | <0.01 | 1.31 | 1.07 | 1.60 | <0.001 | 1.22 | 0.94 | 1.57 | ns |

| RI | 0.40 | 0.33 | 0.50 | <0.001 | 1.03 | 0.85 | 1.25 | ns | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.90 | <0.05 |

| TX | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.32 | <0.001 | 0.53 | 0.42 | 0.68 | <.001 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.30 | <0.001 |

| VT | 0.86 | 0.72 | 1.03 | ns | 0.94 | 0.79 | 1.22 | ns | 0.81 | 0.64 | 1.03 | ns |

| WI | 2.27 | 1.98 | 2.61 | <0.001 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.23 | <0.001 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.32 | <0.001 |

#-regressions controlled for the number of providers in the provider communities seen by the patient and the number of patients treated by the provider communities treating the patient.

Provider communities

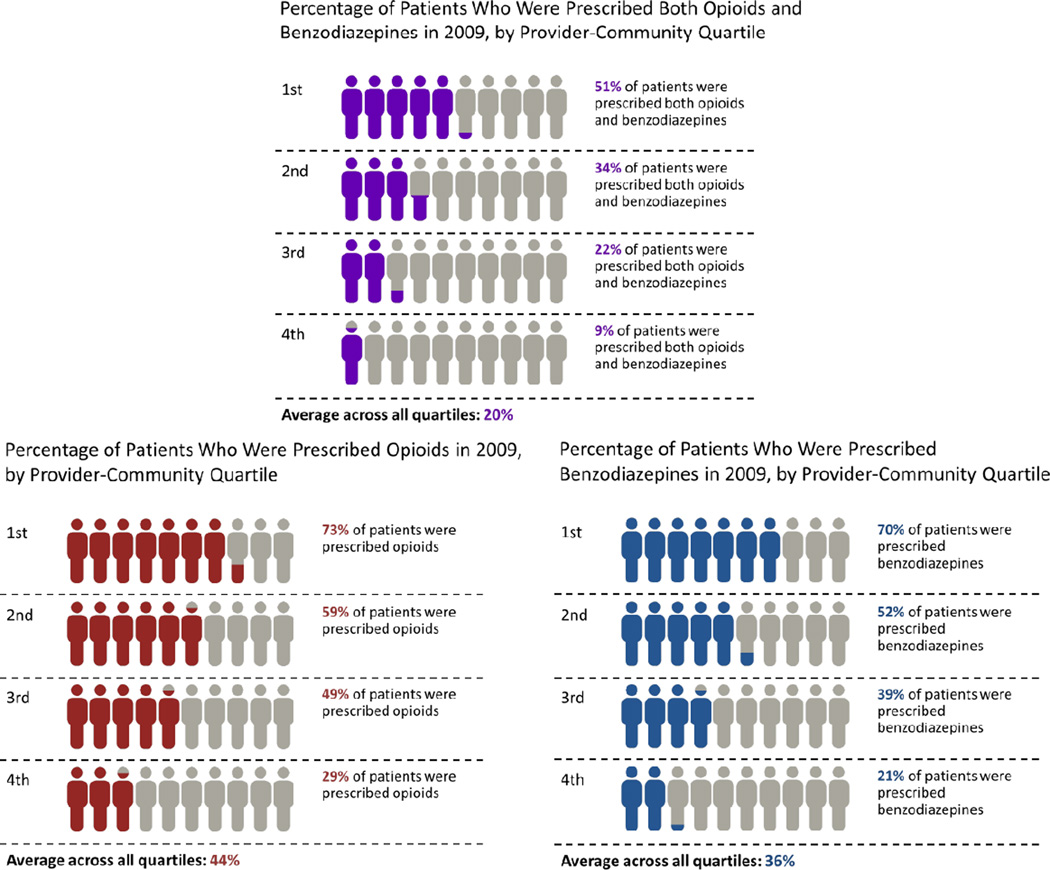

There was substantial variation among provider communities with respect to the percentage of patients receiving opioid analgesics, benzodiazepines, and both drugs (Figure 2). In the provider communities in the highest quartile of opioid analgesic use, 73% of patients received an opioid analgesic in 2009, over 2.5 times the rate of patients seen in the provider communities with the lowest rate of opioid prescribing (29%). In the provider communities in the highest quartile of benzodiazepine use, 70% of patients were prescribed a benzodiazepine in 2009, over 3.3 times the rate of prescribing seen in the provider communities with the lowest rate of benzodiazepine use (21%). And in the provider communities in the highest quartile of combined use, 51% of patients had combined prescribing in 2009, over 5 times the rate of prescribing seen in the provider communities with the lowest rate of combined prescribing (9%). Furthermore, 32% of provider communities (345 of 1081) had more than 50% of the patients with combined use in 2009.

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients receiving opioid analgesics, benzodiazepines, and both opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines by provider community quartile

Discussion

We found that a substantial number of Medicaid-enrollees diagnosed with an opioid use disorder were receiving opioid analgesics or benzodiazepines in the year following diagnosis; 21% were receiving both opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines, a particularly concerning combination associated with higher rates of unintentional overdoses.13 The chronicity of opioid use disorders and the increased risk of relapse for individuals receiving such medications call into question the appropriateness of prescribing these medications to those with an opioid use disorder. This concern is particularly acute in populations where such prescribing appears to be more common and in groups at higher or increasing risk of overdose,33–35 including females, older individuals, patients living in counties with higher poverty rates, and patients diagnosed with pain disorders. It is particularly important to understand appropriate and effective medication for patients diagnosed with pain disorders, given the need to manage pain effectively while also ensuring appropriate monitoring and consideration of non-addictive alternatives.

Prior studies have found convergence in prescribing practices15 and medication choices16,17 among physicians within provider communities defined using methods similar to ours. We found such convergence in the prescribing of opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines to individuals with opioid use disorders; however, prescribing rates varied across provider communities. The percentage of patients who received both medications in those provider communities most likely to prescribe both medications was over 5 times greater than similar patients in provider communities at the lowest quartile of prescribing. We are unable to determine why rates vary across provider communities but posit that it may stem from differences in: (1) patients’ clinical characteristics across provider communities, (2) characteristics of the community, such as having more patients per provider or inadequate access to integrated health records; or (3) practice norms regarding appropriate treatment.36

However, the substantial number of provider communities in which more than half of patients were receiving both opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines was unexpected and concerning. Those provider communities with the highest rates of both opioid analgesic and benzodiazepine prescribing may offer opportunities for targeted interventions. Educational and quality improvement efforts to enhance prescriber knowledge and influence community norms regarding prescribing may be particularly beneficial and impactful, given that information and new practices commonly diffuse more rapidly through provider communities. Future research should also examine to what extent integrated health records, which could make clinicians more aware of prior diagnoses, may influence such prescribing.

Receiving treatment from prescribers in multiple provider communities was positively associated with receiving both drugs. It may be that jointly managing care becomes more difficult as prescribers from more communities are involved in a patient’s care; prescribers in the same community may be more likely to have a history of collaboration or shared integrated electronic medical records.37–39 Alternatively, it may be that prescription-seeking individuals are more successful when seeking prescriptions from multiple provider communities. Doctor shopping is a well-known occurrence among patients desiring opioids and benzodiazepines,13,40,41 and claims data can serve a useful role in identifying patients doing so.42

Patients’ use of opioid analgesics, benzodiazepines, and combined use varied substantially across states. An empirical examination of state policies associated with this variation is beyond the scope of this paper. We note, however, that there is substantial variation in state policies related to prescription drug monitoring programs, lock-in programs, and other regulations likely to affect prescribing of these medications, as well as substantial variation in available treatment options.43 The variation in outcomes across states documented here reinforce the need for further research.

The findings must be considered within the context of the study’s limitations. We examined Medicaid-reimbursed prescriptions among adults in 12 states in 2009, and we do not know to what extent our findings would generalize to Medicaid-enrollees in other states or to non-Medicaid enrollees. We have no information regarding opioid analgesics or benzodiazepines that individuals obtain through cash-pay or other sources, and we do not know how long individuals received opioid analgesics or benzodiazepines nor if they took the medications concurrently, which increases the risk of overdose.44 We do not know why clinicians chose to prescribe these drugs and cannot assess the quality of care or appropriateness of prescribing. We note that there are a number of clinically appropriate reasons why individuals with opioid use disorders might be prescribed such medications, such as the treatment of chronic pain disorders, short term pain relief for trauma or procedures, or time-limited treatment of an anxiety disorder. We also have no information about prescribers that might help to clarify the observed prescribing patterns. Finally, heightened awareness of opioid analgesic misuse45 and state efforts to address it, such as the growth of prescription drug monitoring programs,46 may also limit the generalizability of these findings.

Despite these limitations, our results highlight substantial prescribing of opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines to patients who have been diagnosed with opioid use disorders. One in five individuals have received both medications, with such treatment representing the majority of patients in a substantial number of provider communities. Going forward, efforts to implement lock-in programs in Medicaid and proactive prescription drug monitoring programs, many of which allow physicians to obtain information about prescriptions being filled by their patients, may help to prevent many types of inappropriate prescribing and doctor shopping. However, such efforts may have relatively little impact on prescribing opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines to patients with a history of opioid use disorders because physicians, hampered by restrictive substance abuse treatment privacy regulations or lack of access to a patient’s medical records, may have difficulty identifying these patients. Revisiting such regulations and increasing education among physicians in provider communities with outlier prescribing practices may complement current efforts to address this significant public health issue.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Mary Vaiana, PhD, for comments on a prior version of this manuscript, and Hilary Peterson, BA, of the RAND Corporation for research assistance and assistance with manuscript preparation.

Funding Source: The National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) provided support (award 1R01DA032881-01A1, PI: Stein) for this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: Dr. Stein was previously an employee of Community Care Behavioral Health Organization, a non-profit managed behavioral health organization that managed behavioral health services of Medicaid-enrollees in Pennsylvania. Dr. Stein has also served on an Advisory Board for Otsuka Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Gordon receives royalties from Cambridge University Press and UptoDate for work unrelated to this topic. None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Accessed March 8, 2016];The N-SSATS Report: Trends in the Use of Methadone and Buprenorphine at Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities: 2003 to 2011. 2013 http://archive.samhsa.gov/data/2k13/NSSATS107/sr107-NSSATS-BuprenorphineTrends.htm. [PubMed]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control. Prescription Painkiller Overdoses in the US. Vitalsigns. 2011 Nov; 2011:Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/pdf/2011-2011-vitalsigns.pdf.

- 4.Manchikanti L, Fellows B, Ailinani H, Pampati V. Therapeutic use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioids: a ten-year perspective. Pain Physician. 2010 Sep-Oct;13(5):401–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13–4760, DAWN Series D-39. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy S, Ku J, Kochaneck K. Deaths: Final Data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;61(4):1–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paulozzi LJ. Prescription drug overdoses: a review. J Safety Res. 2012 Sep;43(4):283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birnbaum HG, White AG, Schiller M, Waldman T, Cleveland JM, Roland CL. Societal costs of prescription opioid abuse, dependence, and misuse in the United States. Pain Med. 2011 Apr;12(4):657–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284(13):1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferri M, Finlayson AJ, Wang L, Martin PR. Predictive factors for relapse in patients on buprenorphine maintenance. Am J Addict. 2014 Jan-Feb;23(1):62–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattoo SK, Chakrabarti S, Anjaiah M. Psychosocial factors associated with relapse in men with alcohol or opioid dependence. Indian J Med Res. 2009 Dec;130(6):702–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gossop M, Stewart D, Browne N, Marsden J. Factors associated with abstinence, lapse or relapse to heroin use after residential treatment: protective effect of coping responses. Addiction. 2002 Oct;97(10):1259–1267. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jann M, Kennedy WK, Lopez G. Benzodiazepines: a major component in unintentional prescription drug overdoses with opioid analgesics. J Pharm Pract. 2014 Feb;27(1):5–16. doi: 10.1177/0897190013515001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savage SR, Kirsh KL, Passik SD. Challenges in using opioids to treat pain in persons with substance use disorders. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2008 Jun;4(2):4–25. doi: 10.1151/ascp08424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman J, Katz E, Menzel H. The diffusion of an innovation among physicians. Sociometry. 1957:253–270. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iyengar R, Van den Bulte C, Valente TW. Opinion leadership and social contagion in new product diffusion. Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. Contagion in Prescribing Behavior Among Networks of Doctors. Market Sci. 2011 Mar-Apr;30(2):213–216. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fattore G, Frosini F, Salvatore D, Tozzi V. Social network analysis in primary care: the impact of interactions on prescribing behaviour. Health Policy. 2009 Oct;92(2–3):141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nair HS, Manchanda P, Bhatia T. Asymmetric social interactions in physician prescription behavior: The role of opinion leaders. J Mark Res. 2010;47(5):883–895. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnett ML, Landon BE, O’Malley AJ, Keating NL, Christakis NA. Mapping physician networks with self-reported and administrative data. Health Serv Res. 2011 Oct;46(5):1592–1609. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Callaly T, Trauer T, Munro L, Whelan G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorder in a methadone maintenance population. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001 Oct;35(5):601–605. doi: 10.1080/0004867010060507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brooner RK, King VL, Kidorf M, Schmidt CW, Jr, Bigelow GE. Psychiatric and substance use comorbidity among treatment-seeking opioid abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997 Jan;54(1):71–80. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130077015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmadi J, Majdi B, Mahdavi S, Mohagheghzadeh M. Mood disorders in opioid-dependent patients. J Affect Disord. 2004 Oct 1;82(1):139–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Vol. 43. Rockville, MD: Subtance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005. Chapter 10. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction in opioid treatment programs. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Applying the Substance Abuse Confidentiality Regulations (FAQ) [Accessed November 10, 2015];Substance Abuse Confidentiality Regulations. 2015 http://www.samhsa.gov/about-us/who-we-are/laws/confidentiality-regulations-faqs.

- 26.McCarty D, Janoff S, Coplan P, et al. [Accessed June 28, 2016];Detection of Opioid Overdoses and Poisonings in Electronic Medical Records as Compared to Medical Chart Reviews. 2014 http://www.fda.gof/downloads/Drugs/NewsEvents/UCM398787.pdf.

- 27.United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. [Accessed September 3, 2014];2013 rural-urban continuum codes. 2013 http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx-.VAcgRcVdXOE.

- 28.Blumstein A. Youth violence, guns, and the illicit-drug industry. J Crim Law Criminal. 1995:10–36. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corsaro N, Hunt ED, Hipple NK, McGarrell EF. The impact of drug market pulling levers policing on neighborhood violence. Criminal Public Policy. 2012;11(2):167–199. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clauset A, Newman MEJ, Moore C. Finding community structure in very large networks. Phys Rev E. 2004 Dec;70(6) doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.70.066111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Csardi G, Nepusz T. The igraph software package for complex network research. InterJournal, Complex Systems. 2006;1695(5):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 32.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Internet] Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. Available at: http://www.r-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paulozzi L. [Accessed April 18, 2016];Populations at risk for opioid overdose. 2012 http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/NewsEvents/UCM300859.pdf.

- 34.Coolen P, Best S, Lima A, Sabel JC, Paulozzi L. Overdose deaths involving rescription opioids among Medicaid enrollees - Washington, 2004–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(42):1171–1175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Unick GJ, Rosenblum D, Mars S, Ciccarone D. Intertwined epidemics: national demographic trends in hospitalizations for heroin- and opioid-related overdoses, 1993–2009. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e54496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Detsky AS. Regional variation in medical care. N Engl J Med. 1995 Aug 31;333(9):589–590. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508313330911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ghitza UE, Sparenborg S, Tai B. Improving drug abuse treatment delivery through adoption of harmonized electronic health record systems. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2011 Jul 1;2011(2):125–131. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S23030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tai B, Wu LT, Clark HW. Electronic health records: essential tools in integrating substance abuse treatment with primary care. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2012;3:1–8. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S22575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu LT, Gersing KR, Swartz MS, Burchett B, Li TK, Blazer DG. Using electronic health records data to assess comorbidities of substance use and psychiatric diagnoses and treatment settings among adults. J Psychiatr Res. 2013 Apr;47(4):555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pradel V, Frauger E, Thirion X, et al. Impact of a prescription monitoring program on doctor-shopping for high dosage buprenorphine. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009 Jan;18(1):36–43. doi: 10.1002/pds.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peirce GL, Smith MJ, Abate MA, Halverson J. Doctor and pharmacy shopping for controlled substances. Med Care. 2012 Jun;50(6):494–500. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824ebd81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Han H, Kass PH, Wilsey BL, Li CS. Increasing trends in Schedule II opioid use and doctor shopping during 1999–2007 in California. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014 Jan;23(1):26–35. doi: 10.1002/pds.3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stein BD, Sorbero M, Burns RM, et al. Addiction Health Services Research (AHSR) Conference 2015. Marina del Rey, CA: 2015. The Impact of State Policies on the Use of Buprenorphine Among Medicaid Enrollees Identified with Opioid Use Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park TW, Saitz R, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA, Bohnert AS. Benzodiazepine prescribing patterns and deaths from drug overdose among US veterans receiving opioid analgesics: case-cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h2698. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies-tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014 May 29;370(22):2063–2066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1402780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clark T, Eadie J, Kreiner P, Strickler G. Prescription Drug Montoring Programs: An assessment of the evidence for best practices. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.