Abstract

The cellular mechanisms that result in the initiation and progression of emphysema are clearly complex. A growing body of human data combined with discoveries from mouse models utilizing cigarette smoke exposure or protease administration have improved our understanding of emphysema development by implicating specific cell types that may be important for the pathophysiology of COPD. The most important aspects of emphysematous damage appear to be oxidative or protease stress and sustained macrophage activation and infiltration of other immune cells leading to epithelial damage and cell death. Despite the identification of these associated processes and cell types in many experimental studies, the reasons why cigarette smoke and other pollutants result in unremitting damage instead of injury resolution are still uncertain. We propose an important role for macrophages in the sequence of events that lead and maintain this chronic tissue pathologic process in emphysema. This model involves chronic activation of macrophage subtypes that precludes proper healing of the lung. Further elucidation of the cross-talk between epithelial cells that release damage-associated signals and the cellular immune effectors that respond to these cues is a critical step in the development of novel therapeutics that can restore proper lung structure and function to those afflicted with emphysema.

Keywords: COPD, IL-33, macrophage, cigarette smoke, elastase

A. Introduction

In 1984, the National Institutes of Health in the U.S. funded a workshop which led to what is still the official definition of emphysema, i.e., “a condition of the lung characterized by abnormal, permanent enlargement of airspaces distal to the terminal bronchiole, accompanied by the destruction of their walls, and without obvious fibrosis” (Snider, et al., 1985). While there is little question that alveolar walls are lost in emphysema, the mechanism by which this loss occurs remains poorly understood. The lung has a complex three-dimensional structure in which there needs to be continuous structural continuity from the trachea down to the most peripheral alveoli at the visceral pleural surface. Indeed, it has long been known that there are elastic fibers that run the entire length of the airway tree from the trachea down to the respiratory bronchioles (Macklin, 1922–23). These elastic fibers are located in the mucosa just outside the basement membrane, and they are responsible for the corrugated cross sectional appearance seen in the airway lumen. This axial structural linkage between the largest and smallest airways is essential for proper lung function, since it allows the airways to lengthen with lung inflation thereby providing room for adjacent alveoli to expand. It seems axiomatic that any damage to this mechanical linkage would lead to an inability for alveoli to expand properly, and inflammation in either the alveoli or in the airways that supply the alveoli could have direct impact on this mechanical coupling.

In particular, a few years ago McDonough and colleagues (McDonough, et al., 2011) published work showing that there appeared to be a major obliteration of terminal bronchioles in COPD patients with emphysema. Such obliteration likely resulted from a chronic inflammation of these small airways that eventually led to disruption of the structural elements that supported the subtended alveoli. COPD is a condition consisting of a mix of varying degrees of chronic bronchitis and emphysema. In humans, emphysema rarely appears without some level of associated airway inflammation, and this is true even in patients whose primary cause is simply defective inhibition of neutrophil elastase (Cosio, et al., 2016). Inflammation is also present in animal models of emphysema, although as will be discussed later in detail, the cell profile may be different from what is seen in humans. In this review, though we are focused primarily on emphysema, it is impossible to ignore the structural connection of alveoli to the airways, since anything that impairs this link will lead to loss of alveoli. This concept is illustrated in Figure 1, and the question still remains as to which comes first, the inflammation in the smallest airways with subsequent loss of the structural fibers supporting the acini, or inflammation in the alveoli with subsequent loss of alveoli and the most peripheral connections of the supporting elastic matrix. Indeed there is evidence that inflammation in the small airways leads to structural damage in the wall (Hogg, et al., 1968, Leopold and Gough, 1957), which would be consistent with the loss of the distal acini being a secondary event as in Figure 1-panel B. However, in humans all of the data on the most peripheral airways is of necessity cross-sectional and often in a limited number of subjects, so assessing the initiating events is not possible. Nevertheless, what is clear is that inflammatory cells are playing critical roles in this progressive destruction of lung tissue. It is an objective of this review is to provide a better understanding of their role in the pathologic etiology of both COPD and emphysema, especially in animal models where progressive changes can be studied.

Figure 1.

Two Models of Parenchymal Airspace Enlargement in Emphysema

Panel A - Alveolar inflammation leads to the destruction of alveolar walls and disruption of the elastic fibers that link the acinus to the terminal airways. In addition to causing airspace enlargement, this allows the terminal bronchioles to recoil and obstruct.

Panel B - Inflammation in the terminal bronchioles causes wall thickening, obstruction, and ultimate severing or stretching of the elastic connective tissue fibers. In addition to allowing the bronchioles to recoil and obstruct, this loss of support for the distal acinus leads to folding and ultimate destruction of unsupported alveolar walls and enlargement of the duct.

From [Mitzner, W. Emphysema--a disease of small airways or lung parenchyma? NEJM 365:1637–1639, 2011. Copyright © 2011Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission.]

B. Mouse models of emphysema

i) Assessment of functional and structural changes in emphysema

Quantification of the extent of the lung tissue destruction in emphysema is not always a simple task. For, one, in humans the manifestation of emphysema is often quite heterogeneous, so one needs to be able to define a boundary where one will make the measurement. In humans, this is often done with CT imaging, where lung density below some defined threshold is used as a marker for emphysema (Wang, et al., 2013)). When lung tissue is destroyed, CT density decreases and the extent of emphysema can be quantified across the whole lung. Although people with larger lungs have bigger alveoli as assessed by CT density (Brown, et al., 2015), the magnitude of density changes in emphysema are far greater than the differences that would be seen between healthy large and small lungs. While decreased CT density has been shown in animal models of emphysema, this is not widely utilized. The method normally used in preclinical models is to quantify changes in the postmortem histology, an approach clearly not appropriate for humans. The common metric is based on the mean distances between septal walls, but like alveolar size assessed by CT density (Brown, Wise, Kirk, Drummond and Mitzner, 2015), this metric also increases with lung volume (Hsia, et al., 2010). Thus in both human and animal models, it is essential to measure the lung volume changes with emphysema. These structural changes are impacted by inflammation in both the small airways and parenchyma, and this will be considered in the subsequent sections.

With regard to functional assessment of the emphysematous pathology, although there are many mouse studies where ventilation mechanics are measured, these measurements are generally unrelated to the standard assessments of pulmonary function during forced expiration normally done in humans. This is unfortunate, since the ability to perform equivalent measurements in mice and human subjects may facilitate the translation of results in mouse models to human disease. To circumvent this lack of functional correspondence, the lung diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) (Miller, et al., 2013, Ogilvie, et al., 1957), can be measured. This is a common and easily made measurements in human subjects, but this measurement has only rarely been done in mouse models. We have reported a simple approach that circumvents the problems with measurement of diffusing capacity in mice (Fallica, et al., 2011, Limjunyawong, et al., 2015c). This procedure results in a very reproducible measurement, that is sensitive to a host of pathologic changes in the lung phenotype, including being able to follow the emphysematous changes over time(Limjunyawong, et al., 2015a).

ii) Smoke-induced models of emphysema

Chronic exposure to cigarette smoke in rodents can mimic several features of COPD, including accumulation of inflammatory cells and mediators, elevation of oxidative stress, mucus hypersecretion, decline in lung function, mild degrees of emphysema, airway remodeling, pulmonary hypertension, as well as increase pulmonary inflammation associated with exacerbation (Vlahos and Bozinovski, 2014, Wright and Churg, 2010). The cigarette smoke induced centrilobular emphysema lesion resembles what is seen in smokers whose pathology begins from the respiratory bronchioles and spreads peripherally (Antunes and Rocco, 2011). Thus, this experimental model has been used to gain mechanistic insight into the pathogenesis of emphysema, particularly related to inflammation and oxidative stress.

Since Huber et al. first described morphologic and physiologic alterations following smoke-induced emphysema in rats in the 1980s (Huber, et al., 1981), a wide variety of cigarette smoke-induced animal models of emphysema have been use in different laboratories. There is no standard protocol in terms of duration, frequency, source or route of cigarette smoke exposure. Smoke exposure intervals range from 1 to 3 sessions per day with different number of cigarettes smoked in each session (from 2 up to 40 cigarettes a day), 5 to 7 days weekly for 2 to 36 weeks in total (Cendon, et al., 1997, Gao, et al., 2010, Hautamaki, et al., 1997, Rinaldi, et al., 2012, Shapiro, et al., 2003, Wright and Churg, 1990, Xu, et al., 2004, Zheng, et al., 2009, Zhou, et al., 2012). Different routes of exposure have also been used. Although most studies burn and then passively expose the smoke to the whole animal, some studies have used nose-only smoke exposure systems to target smoke directly to the respiratory system, thereby avoiding confounding effects of the animals’ fur cleaning (Nemmar, et al., 2012, Nemmar, et al., 2013, Rinaldi, Maes, De Vleeschauwer, Thomas, Verbeken, Decramer, Janssens and Gayan-Ramirez, 2012). Moreover, while most systems use side stream smoke (similar to passive smoking in humans), mainstream smoke exposure has also been employed to simulate active smoking (Atkinson, et al., 2011, Obot, et al., 2004, Stinn, et al., 2013, Suzuki, et al., 2009). Despite these widely differing smoke exposures in animal models, generally all of the exposed animals will develop some degree of emphysema, and this is an important difference from human cigarette smoke exposures where less than 20% of smokers get clinical emphysema (Fletcher and Peto, 1977).

Although smoke exposure has relevance to humans, there are some serious limitations and disadvantages of its use in a model system, notably the need for long exposure periods and the associated high housing costs, the relatively mild emphysema that is observed, and the relatively stable lung structure after smoking is stopped (Churg, et al., 2011, Motz, et al., 2008, Wright and Churg, 2010). Smoke from biomass sources other than tobacco has been shown to have similar effects in animal models. Hu and colleagues compared smoke generated either from 25 gram grain crust (typical biomass fuel used for cooking), or from cigarettes and found that biomass smoke could induce the same degree of pulmonary inflammatory BAL cells, systemic oxidative stress, and emphysema as induced by cigarette smoke (Hu, et al., 2013). Similarly, emphysematous changes could be induced by dried dung smoke exposure in rabbits (Fidan, et al., 2006), or by exposing rats to 1 month of daily cow dung smoke (Lal, et al., 2011).

iii) Protease-induced models of emphysema

The first reported experimental emphysema model was done in rats by intratracheal instillation of papain (a plant protease) into rats (Gross, et al., 1965). This animal model of emphysema was established shortly after the discovery of an association between α1-AT deficiency and emphysema in humans (Eriksson, 1964). These clinical and experimental observations led to the hypothesis that the development of emphysema was due to an imbalance between proteases and anti-proteases in the lung. Since the protease activity of papain depends on its purity and source, other more accessible proteases have been adapted for these emphysema models in a variety of animal species, including porcine pancreatic elastase (Hayes, et al., 1975, Kaplan, et al., 1973), human neutrophil elastase (Kuraki, et al., 2002, Lafuma, et al., 1991), collagenase (Snider, et al., 1977), and several others.

It is very important to emphasize that the degree of emphysema progressively worsens (at least for 26 weeks) after this single insult of pancreatic elastase (Kuhn and Tavassoli, 1976, Snider and Sherter, 1977), even though the activity of exogenous enzymes is destroyed by endogenous protease inhibitors within 24 hours following administration (Stone, et al., 1988). The administration of elastase inhibitors has a protective effect only when given immediately before or immediately after elastase challenge–they are not effective even if given 4 hours after the insult (Gudapaty, et al., 1985, Kleinerman, et al., 1980, Stone, et al., 1981). The persistent emphysematous change in this animal model thus may have similarities with observations in humans with emphysema, where the emphysema continues to progress even after stopping smoking (Mohamed Hoesein, et al., 2013, Rutgers, et al., 2000). The mechanism of these chronic progressive changes is not clear, but it suggests that host endogenous responses triggered by an acute injury to the lung epithelium/endothelium may be sufficient to trigger a chronic non-resolving, self-perpetuating cycle of inflammation and lung damage. Indeed, it has been suggested that only 20% of parenchymal tissue loss after elastase administration is caused directly by the enzyme, while the remaining 80% results from the host inflammatory response (Lucey, et al., 2002). This progressive feature of the elastase insult makes it a tractable model to study mechanisms underlying the progressive loss of alveolar tissue, repair/remodeling of tissue in response to injury, and the relationship between altered structure and pulmonary functions/mechanics in emphysema (Hamakawa, et al., 2011, Hou, et al., 2013, Ito, et al., 2005, Kurimoto, et al., 2013, Lanzetti, et al., 2012, Takahashi, et al., 2014). And this model has been used to explore potential drug and intervention therapy to slow the emphysema progression (Massaro and Massaro, 1997, Moreno, et al., 2014, Rubio, et al., 2004).

Although the instillation of proteases can induce emphysema, these models have several drawbacks. First is the obvious distinction that elastase instillation is not a physiologically relevant initiation event in human emphysema. The elastase model, however, is generally not used to study the chronic, low-level environmental events associated with the initiation of emphysema. Rather the aim is to investigate the molecular, cellular and genetic processes that prevent the lung from properly healing and lead to progressive emphysema. It is important to note that none of these animal models faithfully mimic the phenotypes seen in human COPD, since they generally lack the chronic airway inflammation and mucus hypersecretion that are major symptoms in this pathology.

iv) Infection and Emphysema – viral and bacterial exacerbation models

Emphysema in murine models can be caused by Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infection. N. brasiliensis is a natural nematode parasite of rats that has been used as a human hookworm infection model to study host T helper 2 (Th2) protective immunity (Camberis, et al., 2003, Finkelman, et al., 2004). In rodents, free-living third-stage (L3) larvae of N. brasiliensis that have penetrated the skin, migrate via the circulation to the lung where they penetrate into the alveolar spaces via enzyme-assisted mechanical destruction of the respiratory epithelium. The larval worms reside in the lungs for ~2 days during which they molt, become motile, and ascend the airway tree to the oral cavity where they are swallowed. The final stages of development takes place in the small intestine where the adult forms of the parasites mate and the females produce embryonated eggs which are passed with the feces (Camberis, Le Gros and Urban, 2003). N. brasiliensis infection in mice is self-limiting and the adult parasites are expelled from the gastrointestinal tract between 9–13 days post-infection (Camberis, Le Gros and Urban, 2003, Ogilvie, 1971).

Although this nematode resides in the lung only for less than 2 days, it induces strong long-lasting Type 2 immune responses characterized by increasing levels of Th2 cells, IL-4, IL-13, IgE, eosinophils, basophils, mast cells and Type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), as well as alternatively-activated (M2) macrophages, which are thought to promote tissue repair of the damage caused by the worms (Allen and Maizels, 2011, Marsland, et al., 2008b, Min, et al., 2004, Nair, et al., 2005, Reece, et al., 2006, Voehringer, et al., 2004). Infection with N. brasiliensis results in a chronic inflammatory response in the lung leading to progressive destruction of alveolar walls accompanied by an enlargement of airspace size resembling emphysema in humans (Heitmann, et al., 2012, Marsland, et al., 2008a, Turner, et al., 2013). This prolonged helminth-induced lung damage is associated with the hemosiderin positive macrophages with an alternatively activated (M2) phenotype marked by the induction of Arginase (arg), Retnla (fizz1) and Chi3l3 (ym1) expression. These M2 macrophages exhibited substantially up-regulated MMP-12 for up to 6 months, suggesting a persistent role of Th2 cells and M2 macrophages in the chronic progression of emphysema (Marsland, Kurrer, Reissmann, Harris and Kopf, 2008a).

C. Innate and Adaptive Immunity in the Pathogenesis of Emphysema

i) Overview of Innate and adaptive immunity in the lung

The lung has by far the most extensive direct interaction with the external environment of any barrier surface. In order to carry out its prime function of gas exchange the lung needs to maintain an adaptive and dynamic interface that is capable of responding to ever changing chemical, particulate and microbial exposures. A vast majority of these exposures cause no substantive harm, and through the coordinated action of the evolved biophysical barriers and passive molecular defenses the mammalian lung is able to maintain the efficiency of the conducting airways and gas exchange surfaces. A subset of these environmental exposures presents sufficient levels of danger to warrant activation of inducible innate and adaptive immune responses. By virtue of its abilities to rapidly resolve inflammation, repair cellular damage and physiologically adapt to limited losses in functional capacity, the lung is adept at handling most acute challenges. However, chronic exposure to certain harmful substances or microbes challenges the normal scheme of regulated inflammation such that cell and tissue damage is not properly resolved and repaired, which can lead to a enduring loss of lung function due to fibrotic disease or progressive destruction of alveoli. The lung has evolved a number of unique molecular and cellular strategies that balances the requirement to efficiently neutralize the myriad minor environmental challenges encountered daily in a manner that avoids chronic inflammation. While acute inflammation is required to rapidly and robustly deal with toxic and infectious agents that could quickly overwhelm host defenses and cause unsustainable lung damage, it needs to be regulated such that it avoids compromising the delicate gas exchange surfaces of the lung. Disruption of this balanced regulation that governs the appropriate nature, intensity and duration of inflammation is the underlying cause of many persistent lung diseases.

It has become abundantly clear that the epithelial cells that line the conducting and respiratory airways are not simply passive barriers to limit access to chemical and biological exposures, but vital local sensors that communicate the level of danger (Weitnauer, et al., 2016). The major cell types that form the peudostratified cell layer of the conducting airways include ciliated epithelial cells, mucus-producing goblet cells, non-ciliated secretory club cells (formally termed Clara cells) and multipotent basal cells. The thin single-cell layer that forms the alveoli consists of type I and type II alveolar epithelial cells. The specialized subsets of lung epithelial cells secrete a number of antimicrobial and enzymatic effectors that, along with secretory IgA and mucus, serve as a physical and molecular barrier to limit contact with the epithelium and to entrap and direct particulate matter and microbes for mucociliary clearance and their ultimate degradation in the gastrointestinal tract (Hasenberg, et al., 2013). Of the antigens that reach alveolar tissues, most are eliminated by lung-resident macrophages and dendritic cells or are transported via lymphatic vessels to lung-draining lymph nodes.

Under steady-state conditions, epithelial cells are polarized and maintain tight junctions that prevent paracellular transport of microbes and harmful substances to underlying lung tissues. In addition, the tight junctions block the access of molecules that activate Toll-like receptors (TLR) that are deployed on the basolateral surface of lung epithelial cells. TLR agonists that are able to breach this barrier are key danger signals for activating the strategically arrayed cellular components of the innate immune defenses.

Lung epithelial cells achieve their sentinel function through the synthesis of a number of contact-dependent and contact-independent factors that activate and regulate professional immune cells. Deployment of CD200, PD-L1, αvβ6 integrin and E-cadherin on their baso-lateral membrane modulates the activation of mononuclear cells and lymphocytes (Weitnauer, Mijosek and Dalpke, 2016). Cytokines, such as IL-33, IL-25 and TSLP, and stimulatory molecules such as arachidonic acid metabolites are released locally from epithelial cells and can have an effect on the nature, intensity and duration of immune activation (Hasenberg, Stegemann-Koniszewski and Gunzer, 2013, Pouwels, et al., 2014, Tolle and Standiford, 2013, Weitnauer, Mijosek and Dalpke, 2016).

Lung-resident macrophages are another important regulator of pulmonary innate immunity, determining whether to initiate certain inflammatory cascades or remain quiescent in response to pathogenic or cellular damage (Day, et al., 2009). These cells are notoriously poor stimulators of T cell proliferation, and have been described under a variety of conditions to be regulatory in nature (Lambrecht, 2006). Maintaining a high threshold of activation likely ensures that the healthy lung does not endure inflammation unless a specific stimulus poses a serious threat to the host. With a challenge that exceeds the threshold of activation, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPS) released from cells undergoing regulated cell death (Pouwels, Heijink, ten Hacken, Vandenabeele, Krysko, Nawijn and van Oosterhout, 2014) bind to receptors on resident innate cells initiating canonical inflammatory signaling cascades, transcription factor-mediated gene expression, and ultimately cytokine and chemokine production and the recruitment of additional innate effector cells such as neutrophils, monocytes, eosinophils, NK cells and innate lymphoid cells (ILC). Extracellular challenges are dealt with most efficiently by neutrophils, monocytes, and eosinophils through the release the cytokines, proteases, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and reactive oxygen species that are important for pathogen clearance and the initiation of tissue repair. NK cells play a key role in the innate control and elimination of intracellular pathogens. Although our understanding of the functions of ILCs in the lungs is still evolving, it is clear that type 2 ILCs (ILC2) along with lung mast cells are critically important in the induction and maintenance of the type 2 immune responses associated with allergic inflammation and tissue repair.

Agents that are difficult to clear and warrant intensive, longer-term attention result in activation of adaptive immune mechanisms. Cell-free antigens as well as antigens that have been taken up by resident dendritic cells (DC) are trafficked to the lung-draining secondary lymphoid tissues where they are processed and presented to antigen-specific CD4+ helper T cells, cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, and antibody-producing B cells of the nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) or bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) (Hasenberg, Stegemann-Koniszewski and Gunzer, 2013). Antigen-specific antibody production increases opsonization, phagocytosis, and degradation of toxic substances and microbial pathogens. Antigen-specific effector CD4 and CD8 T cells traffic back to the lung to sites of injury and infection where they enhance the local production of cytokines and effector molecules that regulate inflammation and cell death until the agent is cleared. A network of antigen-specific resident memory, effector memory and central memory T cells is established that can be mobilized rapidly upon subsequent exposure to the same agent.

While the above inflammatory responses are critical for pathogen clearance, they also play a significant role in responding to damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) following regulated necroptotic cell death of lung cells (Tolle and Standiford, 2013). As such, inflammatory cells mediate epithelial repair through the release of additional extracellular matrix components and epithelial growth factors (Crosby and Waters, 2010). These include members of the epidermal and fibroblast growth factor families that are secreted by activated resident macrophages and infiltrating leukocytes to jump-start the repair process, inducing the spread of neighboring epithelium and fibroblasts to denuded surfaces. Furthermore, these epithelial repair factors recruit progenitor cells, such as club cells in the bronchioles and Type II pneumocytes in the alveolar parenchyma, that are also necessary for the generation of new healthy tissue. Importantly, transforming growth factor-beta (TGFβ) signaling is required to differentiate spreading epithelium and mesenchymal stem cells into myofibroblasts, which further contribute to extracellular matrix deposition and cytoskeletal remodeling.

Under properly controlled homeostatic conditions, the lungs are returned to their quiescent state once the offending antigen wanes and/or the physical damage is repaired. Major contributing factors to immune regulation in the lungs include re-establishment of the balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, oxidants and antioxidants, proteases and anti-proteases (Crosby and Waters, 2010). Chronic inflammatory lung diseases can develop when these regulatory mechanisms fail to effectively stem the responses initiated by repeated physical trauma, persistent exposure to toxins, or chronic infection in genetically susceptible individuals.

ii) Inflammation following CS exposure

In developed countries, the dominant environmental risk factor for a patient to present with COPD/emphysema is cigarette smoke (CS). It is important to note that other environmental exposures are also important, especially in developing countries where up to 45% of COPD patients have never smoked tobacco. In these settings exposure to indoor air pollution from burning biomass fuels is a major determinant of COPD (Salvi and Barnes, 2009). It is also important to consider that although a majority of COPD/emphysema cases are associated with CS, only about 20% of smokers develop COPD (Pauwels and Rabe, 2004).

While CS has been the most studied risk factor for COPD/emphysema over the past two decades, progress has been limited in defining the main mechanisms through which CS works to increase risk in certain individuals. What has been shown is that chronic exposure to the complex mix of chemical compounds and particulates found in CS interacts with host genetics in a complex way to first induce inflammation and then amplify the inflammatory response by perpetuating imbalances in the interconnected oxidant-antioxidant, protease-antiprotease and cell death-clearance mechanisms in the lungs (Grabiec and Hussell, 2016, Henson, et al., 2006).

CS and epithelial cells

CS has both direct and indirect effects on bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells. In addition to influencing the expression and function of pattern recognition receptors (PRR) and cytokines that alters the epithelial cells’ sensitivity to local environmental changes, acute exposure to the toxic agents in CS results in epithelial cell damage causing the release of DAMPs. One of the direct effects of cigarette smoke on human bronchial epithelial cells both in vitro (Heijink, et al., 2012, Kulkarni, et al., 2010, Mathis, et al., 2013, Schamberger, et al., 2015) and in vivo (Beane, et al., 2007, Harvey, et al., 2007, Shaykhiev, et al., 2011) is to alter gene expression. Even short exposures to CS or CS extracts results in a reduction in the number of ciliated cells, impaired barrier function and reduced expression of genes associated with innate immunity including cytokines (CX3CL1, IL-6, IL8), TLR5, IL4R and the receptor for prostaglandin E2. CS also increased the number of club cells and goblet cells and elevated the levels of MUC5A.

In addition to perturbing their physiological status, components in CS directly and indirectly induce apoptotic and necroptotic death in lung epithelial and endothelial cells resulting in elevated levels of a spectrum of DAMPs and alarmins such as high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), S-100, calthelicidins, uric acid, N-formylated peptides, extracellular ATP, and IL-33 (Cicko, et al., 2010, Fallica, et al., 2016, Ferhani, et al., 2010, Kearley, et al., 2015, Lommatzsch, et al., 2010, Pauwels, et al., 2010, Pauwels and Rabe, 2004). The persistently elevated levels of DAMPs and alarmins found in the BAL fluid from COPD patients suggest a role for these factors in the maintenance of the distinctive inflammation associated with the destruction of respiratory epithelium.

Adaptive immune response

While it is clear that CS-induced bronchitis/emphysema is accompanied by a local accumulation of CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, and B cells in the airways and the alveolar compartment, the exact roles that these adaptive immune cells play in the initiation and progression of disease remain to be defined. Increases in the number of CD8+ T cells and CD4+ Th1 and Th17 cells have been associated with the development of emphysema, and may be important for the maintenance of tissue-damaging innate cells in the lungs (Barnes, 2009, Chang, et al., 2011, Di Stefano, et al., 2009, Hogg, Macklem and Thurlbeck, 1968, Zhang, et al., 2013). Increased CD8+ T cells and CD4+ Th1 cells during emphysema are associated with elevated IFNγ, TNF, IL-6, and IL-1β levels in the lungs (Barnes, 2008). Moreover, these pro-inflammatory cytokines have all been shown to be important for the development of airway inflammation and emphysema in certain contexts. Specifically mouse strains deficient in the receptors for TNF and IL-1β as well as those deficient in IL-6 are protected from emphysema, while strains that over-express TNF and IFNγ in the lungs promote the development of emphysema (Fujita, et al., 2001, Lundblad, et al., 2005, Pauwels, Bracke, Maes, Pilette, Joos and Brusselle, 2010, Ruwanpura, et al., 2011, Tasaka, et al., 2010, Thomson, et al., 2012, Wang, et al., 2000). However, these results have not been consistent across multiple studies, with reports that anti-TNF treatment did little to improve COPD, and that expression levels of IFNγ and its receptor are reduced in cigarette smokers (Shaykhiev, et al., 2009). In this same regard, CD8+ T cell depletion abrogated the development of cigarette smoke-induced emphysema, while SCID mice that lack all T and B cells were not protected (Maeno, et al., 2007, Podolin, et al., 2013). Similarly conflicting results have been obtained for IL-17-producing T cells, which are known to be critical for a number of anti-bacterial host responses including neutrophil chemotaxis and activation (Iwakura, et al., 2011). This is intriguing because COPD exacerbation is often associated with elevated bacterial loads and neutrophils, and IL-17A-expressing cells have been shown to be elevated in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid collected from COPD patients (Chang, Nadigel, Boulais, Bourbeau, Maltais, Eidelman and Hamid, 2011, Di Stefano, Caramori, Gnemmi, Contoli, Vicari, Capelli, Magno, D’Anna, Zanini, Brun, Casolari, Chung, Barnes, Papi, Adcock and Balbi, 2009, Eustace, et al., 2011, Zhang, Chu, Zhong, Lao, He and Liang, 2013). Furthermore, IL-17A over-expression in the lungs recapitulates some features of COPD, and IL-1β, IL-6, and TGFβ, which contribute to the differentiation of CD4+ Th17 cells, have all been shown to be associated with the development of experimental emphysema (Churg, et al., 2009, Couillin, et al., 2009, Morris, et al., 2003, Park, et al., 2005, Pauwels, Bracke, Maes, Pilette, Joos and Brusselle, 2010, Ruwanpura, McLeod, Miller, Jones, Bozinovski, Vlahos, Ernst, Armes, Bardin, Anderson and Jenkins, 2011, Tasaka, Inoue, Miyamoto, Nakano, Kamata, Shinoda, Hasegawa, Miyasho, Satoh, Takano and Ishizaka, 2010). Recently, it was also demonstrated that IL-17A- and IL-17RA-deficiency attenuated the severity of cigarette smoke-induced emphysema (Chen, et al., 2011, Shan, et al., 2012). However, other studies have failed to find a correlation between IL-17 and its receptor levels and COPD patients, and IL-17A was not essential for ozone-induced emphysema (Pinart, et al., 2013, Pridgeon, et al., 2011). Thus, despite the suggestive associations for a role for IL-17A, the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which IL-17A could impact human and experimental emphysema remain unknown.

iii) The inflammatory response to exogenous protease instillation

A single intratracheal instillation of elastase, the most widely used enzyme for this model of emphysema (Shapiro, 2000, Snider, 1992, Snider, et al., 1986), results in inflammation, edema, and hemorrhage that typically resolves in about a week (Kuhn and Tavassoli, 1976, Shim, et al., 2010). The cellular response is characterized by a rapid, but transient, influx of neutrophils followed in succession by slower more sustained increases in eosinophils and lymphocytes (Figure 2). Immediately after administration of elastase, the population of lung-resident macrophages decreases, but they quickly recover. Macrophages, eosinophils, and lymphocytes (both CD4 and CD8 T cells) remain elevated for weeks in the post-elastase lung and the elevation of these cells is associated with rapid and worsening lung damage that can be visualized histologically (Limjunyawong, Craig, Lagasse, Scott and Mitzner, 2015a) and measured by decrements in lung function (Figure 2 and Figure 3). At later times, there are increased numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with significant enlargement of airspaces within 21 days (Kurimoto, Miyahara, Kanehiro, Waseda, Taniguchi, Ikeda, Koga, Nishimori, Tanimoto, Kataoka, Iwakura, Gelfand and Tanimoto, 2013) (Figure 2). Increased ROS production, elevated protease levels and apoptotic markers also appear in the lung during the progressive stage of enzyme-induced emphysema (Ishii, et al., 2005, Lucey, Keane, Kuang, Snider and Goldstein, 2002, Trocme, et al., 2015).

Figure 2.

Cellular Dynamics and Lung Damage in the Elastase Model of Emphysema. Relative changes in the numbers of neutrophils, macrophages, eosinophils, and lymphocytes in the lungs of mice after intratracheal administration of an emphysema-inducing dose of elastase. The histological panels present representative images of the lung at zero, one and three weeks after elastase administration. Bars represent 100 μm.

Figure 3.

Changes in Two Key Lung Function Parameters in Response to Challenge with Elastase. Total lung capacity (TLC) and diffusion factor for carbon monoxide (DFCO) were measured at various times after intratracheal elastase administration in BALB/cJ mice. TLC and DFCO were measured as described in (Limjunyawong, et al., 2015b).

iv) Infection-Induced Inflammation and Emphysema

Cigarette smoke-induced emphysema models have been used to investigate the potential of bacterial or viral infection to exacerbate the COPD phenotype. Several studies have reported that exacerbation with bacteria (H. influenzae), virus (rhinovirus), or a surrogate for virus-induced innate immunity (poly(I:C)) accelerates the progression of cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice (Foronjy, et al., 2014, Ganesan, et al., 2014, Kang, et al., 2008, Tanabe, et al., 2013). In addition, mice exposed to cigarette smoke and then infected with influenza virus H1N1 or H3N1 had increased in the number of immune cells in the BAL fluid and a 10-fold increase in lung virus titers (Bauer, et al., 2010, Gualano, et al., 2008). Of note, the activated virus-specific CD8+ T cells in the lung of smoked mice produce a significantly different cytokine profile compared to CD8+ T cells from non-smoked mice.

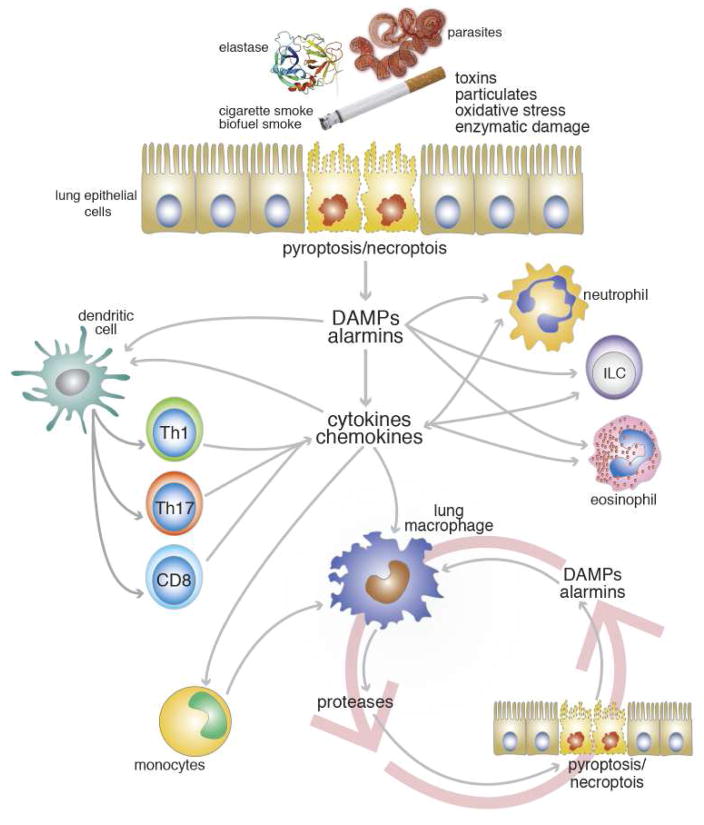

D. Proposed Model of Immunopathology in Emphysema

The cellular mechanisms that result in the initiation and progression of emphysema are clearly complex. A growing body of human data combined with discoveries from mouse models utilizing cigarette smoke exposure or protease administration have improved our understanding of emphysema development by implicating specific cell types that may be important for the pathophysiology of COPD (Campbell, 2000, Vestbo, et al., 2013). Resident and infiltrating monocytes/macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes appear responsible for the local release of various proteases in the lungs, including cathepsins, the gelatinase and collagenase matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) -1, -2, -8, -9, -13, and -14, and the neutrophil and macrophage (MMP-12) elastases during emphysema (Hogg and Senior, 2002). The increase in these lung proteases relative to their tissue inhibitors, such as TIMP-1 and α1-antitrypsin, is believed to drive degradation of the collagen and elastin fibers that comprise the alveolar septa contributing to the development of emphysematous lesions (Mitzner, 2011). In addition to these cell types, the inflammatory activity of CD4+ Th1 and Th17 cells have also been associated with the progression of emphysema in human COPD (Di Stefano, Caramori, Gnemmi, Contoli, Vicari, Capelli, Magno, D’Anna, Zanini, Brun, Casolari, Chung, Barnes, Papi, Adcock and Balbi, 2009, Grumelli, et al., 2004). Although clinical and experimental studies have provided a focused list of immune cells that are implicated in the pathogenesis of COPD/emphysema, we are still largely in the dark regarding the events that activate these cells over the course of the disease and, more importantly, the mechanisms by which accelerated lung damage progresses in many individuals - even following smoking cessation. An important step towards elucidating these unidentified pathogenic mechanisms in chronic emphysema will likely be the discovery of pathways that make a connection between damage to airway and alveolar epithelium and the recruitment and activation of the leukocytes that mediate the disruption of lung structure and function.

A critical aspect of the leukocyte-associated damage response in the lungs is initiated when alarmins such as IL-33 (Molofsky, et al., 2015) are released following acute or chronic damage to lung epithelial cells. IL-33 is released predominantly from type II alveolar epithelial cells in the lung (Fleming, et al., 2015, Pichery, et al., 2012) and can engage its receptor (ST2) on the surface of various leukocyte populations, including type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) that produce molecules such as amphiregulin and IL-13 (Molofsky, Savage and Locksley, 2015) to promote repair. In this regard, a recent report provides insight into the one of the possible roles of cigarette smoke as a risk factor by demonstrating that a key alteration induced by smoke in mice is an increase in the levels of epithelial-derived IL-33 (Kearley, Silver, Sanden, Liu, Berlin, White, Mori, Pham, Ward, Criner, Marchetti, Mustelin, Erjefalt, Kolbeck and Humbles, 2015). This conditioning of the alveolar epithelium by cigarette smoke results in an increase in the intracellular levels of IL-33 in type II epithelial cells that can be released upon subsequent epithelial cell death. In addition, cigarette smoke elevates cellular responsiveness to IL-33 by increasing ST2 expression on the surface of macrophages and NK cells.

With the identification that a number of potent IL-13-producing effector cells (ILC2s, eosinophils, basophils, mast cells, Th2 cells) can express the IL-33-specific receptor component ST2, it is becoming clear that IL-33-responsive cells are largely responsible for the initiation of many aspects of Type 2 immunity, including CD4+ Th2 cell maintenance, M2 macrophage activation, mast cell and eosinophil activation, and epithelial wound repair (Kurowska-Stolarska, et al., 2009, Yang, et al., 2013b). Interestingly, IL-33 levels were found to positively correlate with declining lung function in GOLD Stage III/IV COPD patients (Kearley, Silver, Sanden, Liu, Berlin, White, Mori, Pham, Ward, Criner, Marchetti, Mustelin, Erjefalt, Kolbeck and Humbles, 2015), and was shown to be required for the viral exacerbation of cigarette smoke-induced lung injury in mice, in part through the activation of inflammatory macrophages (Kurowska-Stolarska, Stolarski, Kewin, Murphy, Corrigan, Ying, Pitman, Mirchandani, Rana, van Rooijen, Shepherd, McSharry, McInnes, Xu and Liew, 2009, Yang, et al., 2013a). Furthermore, it has been shown that IL-33 amplifies M2 activation directly in peritoneal macrophages and, in consort with IL-4 and/or IL-13, in bone marrow-derived and alveolar macrophage activation (Kurowska-Stolarska, Stolarski, Kewin, Murphy, Corrigan, Ying, Pitman, Mirchandani, Rana, van Rooijen, Shepherd, McSharry, McInnes, Xu and Liew, 2009, Yang, Grinchuk, Urban, Bohl, Sun, Notari, Yan, Ramalingam, Keegan, Wynn, Shea-Donohue and Zhao, 2013a). While additional work is needed, there is mounting evidence that the IL-33-ST2-M2 macrophage axis plays a central role in the mechanism that results in emphysema.

IL-13 and other factors released from innate and adaptive cells result in M2 activation of lung-resident macrophages, which in turn are tasked with regulating this repair-associated Th2-like inflammation. For example, M2-derived factors including Fizz1/Relmα and Arginase-1 have been shown to limit IL-13-dependent fibrotic repair processes such as collagen deposition, eosinophil infiltration, CD4+ T cell activation, and granuloma formation (Wynn, 2015). During a properly regulated response, these M2 cells can also receive additional signals from the local environment that transition them towards a phenotype capable of remodeling newly deposited extracellular matrix components through the production of tissue proteases (Borthwick, et al., 2016, Novak and Koh, 2013). It is possible that a dysregulation of these macrophage-coordinated repair mechanisms establishes a detrimental cycle that is the basis for the destructive lung pathology observed in progressive emphysema as illustrated in Figure 4. Indeed, selective depletion of lung resident macrophages and recruited monocytes ameliorates elastase-induced emphysema in mice (Ueno, et al., 2015).

Figure 4.

Model for the Roles of Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses in the Induction and Persistence of Lung Damage in Emphysema. See text for detailed explanation.

This hypothesis is supported by the observation that monocytes/macrophages are persistently elevated in human COPD/emphysema and are a prominent feature in all the rodent models (Barnes, 2016, Byrne, et al., 2015, Grabiec and Hussell, 2016). Given what we know about the nature of the cellular damage that is associated with the initiation of COPD/emphysema and proposed role for macrophages in the chronic progression of disease, it is interesting to view emphysema progression as a dysregulation of the repair-remodeling mechanism in the lungs. This paradigm is illustrated by the model in Figure 4.

However, assigning key roles for epithelial-derived alarmins and macrophages in no way excludes other cytokines and immune cells from contributing to the pathogenesis of emphysema. Given their prominence in the lungs after cigarette smoke exposure and elastase administration, the neutrophil is a logical candidate as another key component in the progression of disease. However, neutrophil depletion during the early stages of the response had no impact on the rate or degree of emphysematous change in the elastase model (unpublished data). Beyond myeloid cells, a great deal of effort has also focused on defining the role of lymphocytes in COPD leading to emphysema. In particular, recent work has identified IL-17A-producing Th17, CD8+, and γδ T cells as being associated with emphysema in cigarette smoke models and in human cases of COPD (Chang, Nadigel, Boulais, Bourbeau, Maltais, Eidelman and Hamid, 2011, Di Stefano, Caramori, Gnemmi, Contoli, Vicari, Capelli, Magno, D’Anna, Zanini, Brun, Casolari, Chung, Barnes, Papi, Adcock and Balbi, 2009, Eustace, Smyth, Mitchell, Williamson, Plumb and Singh, 2011, Shan, Yuan, Song, Roberts, Zarinkamar, Seryshev, Zhang, Hilsenbeck, Chang, Dong, Corry and Kheradmand, 2012, Zhang, Chu, Zhong, Lao, He and Liang, 2013). There is also very recent evidence of a key role for IL-17A not only associated with acute exacerbations (Roos, et al., 2015b), but also in those patients with the most severe COPD (Roos, et al., 2015a). Furthermore, mice deficient in IL-17A or IL-17RA were shown to have attenuated severity of emphysema following cigarette smoke exposure (Chen, Pociask, McAleer, Chan, Alcorn, Kreindler, Keyser, Shapiro, Houghton, Kolls and Zheng, 2011, Shan, Yuan, Song, Roberts, Zarinkamar, Seryshev, Zhang, Hilsenbeck, Chang, Dong, Corry and Kheradmand, 2012). As the evidence grows to support an important role for IL-17 in the pathogenesis of emphysema in both humans and animal models, outstanding questions regarding the cellular sources and relevant targets of IL-17 remain. While T cell-derived IL-17 may be important under certain circumstances, models in which WT levels of emphysema can be achieved in T cell deficient animals (D’Hulst A, et al., 2005, Maeno, Houghton, Quintero, Grumelli, Owen and Shapiro, 2007, Podolin, Foley, Carpenter, Bolognese, Logan, Long, Harrison and Walsh, 2013) imply an innate cellular source of this cytokine is sufficient. Furthermore, while elevated CD4 and CD8 T cell levels are a prominent feature of lungs undergoing emphysematous changes in both humans and mice, the fact that lymphocyte-deficient and WT mice have nearly identical levels of emphysema after cigarette smoke (D’Hulst A, Maes, Bracke, Demedts, Tournoy, Joos and Brusselle, 2005, Maeno, Houghton, Quintero, Grumelli, Owen and Shapiro, 2007, Podolin, Foley, Carpenter, Bolognese, Logan, Long, Harrison and Walsh, 2013) and elastase exposure (unpublished data) suggests that the presence of adaptive immunity is not an absolute requirement for disease manifestation under certain conditions.

E. Summary

In summary, it is clear that the pathogenesis of emphysema is complex and not fully understood. The most important aspects of emphysematous changes appear to be sustained oxidative stress and cell damage mediated directly or indirectly by macrophage and other cells of the innate and adaptive immune system leading to evermore-extensive epithelial cell death and increasing decrements in lung function. Despite advances in the identification of these associated processes and cell types, the mechanisms underlying why cigarette smoke and other environmental challenges result in progressive damage instead of injury resolution remain to be defined. Further elucidation of the cross-talk between epithelial cells that release damage-associated signals and the cellular immune effectors that respond to these cues is a critical step in the development of novel therapeutics that can restore proper lung structure and function to those afflicted with emphysema.

Acknowledgments

Funding Information:

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants P01-HL-10342 to W Mitzner and AL Scott and F32-HL-124823 to JM Craig.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Allen JE, Maizels RM. Diversity and dialogue in immunity to helminths. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:375–388. doi: 10.1038/nri2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes MA, Rocco PR. Elastase-induced pulmonary emphysema: insights from experimental models. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias. 2011;83:1385–1396. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652011005000039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson JJ, Lutey BA, Suzuki Y, Toennies HM, Kelley DG, Kobayashi DK, Ijem WG, Deslee G, Moore CH, Jacobs ME, Conradi SH, Gierada DS, Pierce RA, Betsuyaku T, Senior RM. The role of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in cigarette smoke-induced emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:876–884. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201005-0718OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ. The cytokine network in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3546–3556. doi: 10.1172/JCI36130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ. The cytokine network in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:631–638. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0220TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ. Inflammatory mechanisms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer CM, Zavitz CC, Botelho FM, Lambert KN, Brown EG, Mossman KL, Taylor JD, Stampfli MR. Treating viral exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: insights from a mouse model of cigarette smoke and H1N1 influenza infection. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beane J, Sebastiani P, Liu G, Brody JS, Lenburg ME, Spira A. Reversible and permanent effects of tobacco smoke exposure on airway epithelial gene expression. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R201. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borthwick LA, Barron L, Hart KM, Vannella KM, Thompson RW, Oland S, Cheever A, Sciurba J, Ramalingam TR, Fisher AJ, Wynn TA. Macrophages are critical to the maintenance of IL-13-dependent lung inflammation and fibrosis. Mucosal immunology. 2016;9:38–55. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RH, Wise RA, Kirk G, Drummond MB, Mitzner W. Lung density changes with growth and inflation. Chest. 2015;148:995–1002. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne AJ, Mathie SA, Gregory LG, Lloyd CM. Pulmonary macrophages: key players in the innate defence of the airways. Thorax. 2015;70:1189–1196. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camberis M, Le Gros G, Urban J., Jr . Animal model of Nippostrongylus brasiliensis and Heligmosomoides polygyrus. In: Coligan John E, et al., editors. Current protocols in immunology. Unit 19. Chapter 19. 2003. p. 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell EJ. Animal models of emphysema: the next generations. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1445–1446. doi: 10.1172/JCI11791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cendon SP, Battlehner C, Lorenzi Filho G, Dohlnikoff M, Pereira PM, Conceicao GM, Beppu OS, Saldiva PH. Pulmonary emphysema induced by passive smoking: an experimental study in rats. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1997;30:1241–1247. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x1997001000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Nadigel J, Boulais N, Bourbeau J, Maltais F, Eidelman DH, Hamid Q. CD8 positive T cells express IL-17 in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2011;12:43. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Pociask DA, McAleer JP, Chan YR, Alcorn JF, Kreindler JL, Keyser MR, Shapiro SD, Houghton AM, Kolls JK, Zheng M. IL-17RA is required for CCL2 expression, macrophage recruitment, and emphysema in response to cigarette smoke. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churg A, Sin DD, Wright JL. Everything prevents emphysema: are animal models of cigarette smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease any use? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45:1111–1115. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0087PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churg A, Zhou S, Wang X, Wang R, Wright JL. The role of interleukin-1beta in murine cigarette smoke-induced emphysema and small airway remodeling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:482–490. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0038OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicko S, Lucattelli M, Muller T, Lommatzsch M, De Cunto G, Cardini S, Sundas W, Grimm M, Zeiser R, Durk T, Zissel G, Boeynaems JM, Sorichter S, Ferrari D, Di Virgilio F, Virchow JC, Lungarella G, Idzko M. Purinergic receptor inhibition prevents the development of smoke-induced lung injury and emphysema. J Immunol. 2010;185:688–697. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosio MG, Bazzan E, Rigobello C, Tine M, Turato G, Baraldo S, Saetta M. Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency: Beyond the Protease/Antiprotease Paradigm. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2016;13(Suppl 4):S305–310. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201510-671KV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couillin I, Vasseur V, Charron S, Gasse P, Tavernier M, Guillet J, Lagente V, Fick L, Jacobs M, Coelho FR, Moser R, Ryffel B. IL-1R1/MyD88 signaling is critical for elastase-induced lung inflammation and emphysema. J Immunol. 2009;183:8195–8202. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby LM, Waters CM. Epithelial repair mechanisms in the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;298:L715–731. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00361.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Hulst AI, Maes T, Bracke KR, Demedts IK, Tournoy KG, Joos GF, Brusselle GG. Cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary emphysema in scid-mice. Is the acquired immune system required? Respir Res. 2005;6:147. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day J, Friedman A, Schlesinger LS. Modeling the immune rheostat of macrophages in the lung in response to infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11246–11251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904846106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano A, Caramori G, Gnemmi I, Contoli M, Vicari C, Capelli A, Magno F, D’Anna SE, Zanini A, Brun P, Casolari P, Chung KF, Barnes PJ, Papi A, Adcock I, Balbi B. T helper type 17-related cytokine expression is increased in the bronchial mucosa of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;157:316–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03965.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson S. Pulmonary Emphysema and Alpha1-Antitrypsin Deficiency. Acta medica Scandinavica. 1964;175:197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1964.tb00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eustace A, Smyth LJ, Mitchell L, Williamson K, Plumb J, Singh D. Identification of cells expressing IL-17A and IL-17F in the lungs of patients with COPD. Chest. 2011;139:1089–1100. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallica J, Das S, Horton M, Mitzner W. Application of carbon monoxide diffusing capacity in the mouse lung. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011;110:1455–1459. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01347.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallica J, Varela L, Johnston L, Kim B, Serebreni L, Wang L, Damarla M, Kolb TM, Hassoun PM, Damico R. Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor: A Novel Inhibitor of Apoptosis Signal-Regulating Kinase 1-p38-Xanthine Oxidoreductase-Dependent Cigarette Smoke-Induced Apoptosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;54:504–514. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0403OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferhani N, Letuve S, Kozhich A, Thibaudeau O, Grandsaigne M, Maret M, Dombret MC, Sims GP, Kolbeck R, Coyle AJ, Aubier M, Pretolani M. Expression of high-mobility group box 1 and of receptor for advanced glycation end products in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:917–927. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0340OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidan F, Unlu M, Sezer M, Sahin O, Tokyol C, Esme H. Acute effects of environmental tobacco smoke and dried dung smoke on lung histopathology in rabbits. Pathology. 2006;38:53–57. doi: 10.1080/00313020500459615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelman FD, Shea-Donohue T, Morris SC, Gildea L, Strait R, Madden KB, Schopf L, Urban JF., Jr Interleukin-4- and interleukin-13-mediated host protection against intestinal nematode parasites. Immunol Rev. 2004;201:139–155. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming BD, Chandrasekaran P, Dillon LA, Dalby E, Suresh R, Sarkar A, El-Sayed NM, Mosser DM. The generation of macrophages with anti-inflammatory activity in the absence of STAT6 signaling. J Leukoc Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1189/jlb.2A1114-560R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher C, Peto R. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. British medical journal. 1977;1:1645–1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6077.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foronjy RF, Dabo AJ, Taggart CC, Weldon S, Geraghty P. Respiratory syncytial virus infections enhance cigarette smoke induced COPD in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M, Shannon JM, Irvin CG, Fagan KA, Cool C, Augustin A, Mason RJ. Overexpression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha produces an increase in lung volumes and pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L39–49. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.1.L39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan S, Comstock AT, Kinker B, Mancuso P, Beck JM, Sajjan US. Combined exposure to cigarette smoke and nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae drives development of a COPD phenotype in mice. Respir Res. 2014;15:11. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao YD, Zou JJ, Zheng JW, Shang M, Chen X, Geng S, Yang J. Promoting effects of IL-13 on Ca2+ release and store-operated Ca2+ entry in airway smooth muscle cells. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2010;23:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabiec AM, Hussell T. The role of airway macrophages in apoptotic cell clearance following acute and chronic lung inflammation. Seminars in immunopathology. 2016;38:409–423. doi: 10.1007/s00281-016-0555-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross P, Pfitzer EA, Tolker E, Babyak MA, Kaschak M. Experimental Emphysema: Its Production with Papain in Normal and Silicotic Rats. Archives of environmental health. 1965;11:50–58. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1965.10664169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumelli S, Corry DB, Song LZ, Song L, Green L, Huh J, Hacken J, Espada R, Bag R, Lewis DE, Kheradmand F. An immune basis for lung parenchymal destruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema. PLoS Med. 2004;1:e8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualano RC, Hansen MJ, Vlahos R, Jones JE, Park-Jones RA, Deliyannis G, Turner SJ, Duca KA, Anderson GP. Cigarette smoke worsens lung inflammation and impairs resolution of influenza infection in mice. Respir Res. 2008;9:53. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-9-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudapaty SR, Liener IE, Hoidal JR, Padmanabhan RV, Niewoehner DE, Abel J. The prevention of elastase-induced emphysema in hamsters by the intratracheal administration of a synthetic elastase inhibitor bound to albumin microspheres. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;132:159–163. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.132.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamakawa H, Bartolak-Suki E, Parameswaran H, Majumdar A, Lutchen KR, Suki B. Structure-function relations in an elastase-induced mouse model of emphysema. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45:517–524. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0473OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey BG, Heguy A, Leopold PL, Carolan BJ, Ferris B, Crystal RG. Modification of gene expression of the small airway epithelium in response to cigarette smoking. Journal of molecular medicine. 2007;85:39–53. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0103-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenberg M, Stegemann-Koniszewski S, Gunzer M. Cellular immune reactions in the lung. Immunol Rev. 2013;251:189–214. doi: 10.1111/imr.12020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hautamaki RD, Kobayashi DK, Senior RM, Shapiro SD. Requirement for macrophage elastase for cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. Science. 1997;277:2002–2004. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JA, Korthy A, Snider GL. The pathology of elastase-induced panacinar emphysema in hamsters. The Journal of pathology. 1975;117:1–14. doi: 10.1002/path.1711170102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijink IH, Brandenburg SM, Postma DS, van Oosterhout AJ. Cigarette smoke impairs airway epithelial barrier function and cell-cell contact recovery. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:419–428. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00193810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitmann L, Rani R, Dawson L, Perkins C, Yang Y, Downey J, Holscher C, Herbert DR. TGF-beta-responsive myeloid cells suppress type 2 immunity and emphysematous pathology after hookworm infection. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:897–906. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson PM, Vandivier RW, Douglas IS. Cell death, remodeling, and repair in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2006;3:713–717. doi: 10.1513/pats.200605-104SF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg JC, Macklem PT, Thurlbeck WM. Site and nature of airway obstruction in chronic obstructive lung disease. N Engl J Med. 1968;278:1355–1360. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196806202782501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg JC, Senior RM. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease - part 2: pathology and biochemistry of emphysema. Thorax. 2002;57:830–834. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.9.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou HH, Cheng SL, Liu HT, Yang FZ, Wang HC, Yu CJ. Elastase induced lung epithelial cell apoptosis and emphysema through placenta growth factor. Cell death & disease. 2013;4:e793. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia CC, Hyde DM, Ochs M, Weibel ER. An official research policy statement of the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society: standards for quantitative assessment of lung structure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:394–418. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200809-1522ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G, Zhou Y, Hong W, Tian J, Hu J, Peng G, Cui J, Li B, Ran P. Development and systematic oxidative stress of a rat model of chronic bronchitis and emphysema induced by biomass smoke. Exp Lung Res. 2013;39:229–240. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2013.797521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber GL, Davies P, Zwilling GR, Pochay VE, Hinds WC, Nicholas HA, Mahajan VK, Hayashi M, First MW. A morphologic and physiologic bioassay for quantifying alterations in the lung following experimental chronic inhalation of tobacco smoke. Bulletin europeen de physiopathologie respiratoire. 1981;17:269–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii Y, Itoh K, Morishima Y, Kimura T, Kiwamoto T, Iizuka T, Hegab AE, Hosoya T, Nomura A, Sakamoto T, Yamamoto M, Sekizawa K. Transcription factor Nrf2 plays a pivotal role in protection against elastase-induced pulmonary inflammation and emphysema. J Immunol. 2005;175:6968–6975. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Ingenito EP, Brewer KK, Black LD, Parameswaran H, Lutchen KR, Suki B. Mechanics, nonlinearity, and failure strength of lung tissue in a mouse model of emphysema: possible role of collagen remodeling. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:503–511. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00590.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakura Y, Ishigame H, Saijo S, Nakae S. Functional specialization of interleukin-17 family members. Immunity. 2011;34:149–162. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang MJ, Lee CG, Lee JY, Dela Cruz CS, Chen ZJ, Enelow R, Elias JA. Cigarette smoke selectively enhances viral PAMP- and virus-induced pulmonary innate immune and remodeling responses in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2771–2784. doi: 10.1172/JCI32709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PD, Kuhn C, Pierce JA. The induction of emphysema with elastase. I. The evolution of the lesion and the influence of serum. The Journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 1973;82:349–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearley J, Silver JS, Sanden C, Liu Z, Berlin AA, White N, Mori M, Pham TH, Ward CK, Criner GJ, Marchetti N, Mustelin T, Erjefalt JS, Kolbeck R, Humbles AA. Cigarette smoke silences innate lymphoid cell function and facilitates an exacerbated type I interleukin-33-dependent response to infection. Immunity. 2015;42:566–579. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinerman J, Ranga V, Rynbrandt D, Sorensen J, Powers JC. The effect of the specific elastase inhibitor, alanyl alanyl prolyl alanine chloromethylketone, on elastase-induced emphysema. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;121:381–387. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.121.2.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn C, 3rd, Tavassoli F. The scanning electron microscopy of elastase-induced emphysema. A comparison with emphysema in man. Lab Invest. 1976;34:2–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni R, Rampersaud R, Aguilar JL, Randis TM, Kreindler JL, Ratner AJ. Cigarette smoke inhibits airway epithelial cell innate immune responses to bacteria. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2146–2152. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01410-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuraki T, Ishibashi M, Takayama M, Shiraishi M, Yoshida M. A novel oral neutrophil elastase inhibitor (ONO-6818) inhibits human neutrophil elastase-induced emphysema in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:496–500. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2103118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurimoto E, Miyahara N, Kanehiro A, Waseda K, Taniguchi A, Ikeda G, Koga H, Nishimori H, Tanimoto Y, Kataoka M, Iwakura Y, Gelfand EW, Tanimoto M. IL-17A is essential to the development of elastase-induced pulmonary inflammation and emphysema in mice. Respir Res. 2013;14:5. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurowska-Stolarska M, Stolarski B, Kewin P, Murphy G, Corrigan CJ, Ying S, Pitman N, Mirchandani A, Rana B, van Rooijen N, Shepherd M, McSharry C, McInnes IB, Xu D, Liew FY. IL-33 amplifies the polarization of alternatively activated macrophages that contribute to airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2009;183:6469–6477. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafuma C, Frisdal E, Harf A, Robert L, Hornebeck W. Prevention of leucocyte elastase-induced emphysema in mice by heparin fragments. Eur Respir J. 1991;4:1004–1009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal K, Mani U, Pandey R, Singh N, Singh AK, Patel DK, Singh MP, Murthy RC. Multiple approaches to evaluate the toxicity of the biomass fuel cow dung (kanda) smoke. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2011;74:2126–2132. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambrecht BN. Alveolar macrophage in the driver’s seat. Immunity. 2006;24:366–368. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzetti M, da Costa CA, Nesi RT, Barroso MV, Martins V, Victoni T, Lagente V, Pires KM, e Silva PM, Resende AC, Porto LC, Benjamim CF, Valenca SS. Oxidative stress and nitrosative stress are involved in different stages of proteolytic pulmonary emphysema. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:1993–2001. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold JG, Gough J. The centrilobular form of hypertrophic emphysema and its relation to chronic bronchitis. Thorax. 1957;12:219–235. doi: 10.1136/thx.12.3.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limjunyawong N, Craig JM, Lagasse HA, Scott AL, Mitzner W. Experimental progressive emphysema in BALB/cJ mice as a model for chronic alveolar destruction in humans. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015a;309:L662–676. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00214.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limjunyawong N, Craig JM, Lagasse HD, Scott AL, Mitzner W. Experimental Progressive Emphysema in BALB/cJ Mice as a Model for Chronic Alveolar Destruction In Humans. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015b;309:L6620–L6676. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00214.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limjunyawong N, Fallica J, Ramakrishnan A, Datta K, Gabrielson M, Horton M, Mitzner W. Phenotyping mouse pulmonary function in vivo with the lung diffusing capacity. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2015c:e52216. doi: 10.3791/52216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lommatzsch M, Cicko S, Muller T, Lucattelli M, Bratke K, Stoll P, Grimm M, Durk T, Zissel G, Ferrari D, Di Virgilio F, Sorichter S, Lungarella G, Virchow JC, Idzko M. Extracellular adenosine triphosphate and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:928–934. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200910-1506OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucey EC, Keane J, Kuang PP, Snider GL, Goldstein RH. Severity of elastase-induced emphysema is decreased in tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1beta receptor-deficient mice. Lab Invest. 2002;82:79–85. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad LK, Thompson-Figueroa J, Leclair T, Sullivan MJ, Poynter ME, Irvin CG, Bates JH. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha overexpression in lung disease: a single cause behind a complex phenotype. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:1363–1370. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200410-1349OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macklin CC. A note on the elastic membrane of the bronchial tree of mammals, with an interpretation of its functional significance. The Anatomical record. 1922–23;24:119–135. [Google Scholar]

- Maeno T, Houghton AM, Quintero PA, Grumelli S, Owen CA, Shapiro SD. CD8+ T Cells are required for inflammation and destruction in cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. J Immunol. 2007;178:8090–8096. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.8090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsland BJ, Kurrer M, Reissmann R, Harris NL, Kopf M. Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infection leads to the development of emphysema associated with the induction of alternatively activated macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 2008a;38:479–488. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsland BJ, Kurrer M, Reissmann R, Harris NL, Kopf M. Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infection leads to the development of emphysema associated with the induction of alternatively activated macrophages. European journal of immunology. 2008b;38:479–488. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massaro GD, Massaro D. Retinoic acid treatment abrogates elastase-induced pulmonary emphysema in rats. Nat Med. 1997;3:675–677. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis C, Poussin C, Weisensee D, Gebel S, Hengstermann A, Sewer A, Belcastro V, Xiang Y, Ansari S, Wagner S, Hoeng J, Peitsch MC. Human bronchial epithelial cells exposed in vitro to cigarette smoke at the air-liquid interface resemble bronchial epithelium from human smokers. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;304:L489–503. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00181.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough JE, Yuan R, Suzuki M, Seyednejad N, Elliott WM, Sanchez PG, Wright AC, Gefter WB, Litzky L, Coxson HO, Pare PD, Sin DD, Pierce RA, Woods JC, McWilliams AM, Mayo JR, Lam SC, Cooper JD, Hogg JC. Small-airway obstruction and emphysema in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1567–1575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A, Warshaw R, Nezamis J. Diffusing capacity and forced vital capacity in 5,003 asbestos-exposed workers: Relationships to interstitial fibrosis (ILO profusion score) and pleural thickening. American journal of industrial medicine. 2013;56:1383–1393. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min B, Prout M, Hu-Li J, Zhu J, Jankovic D, Morgan ES, Urban JF, Jr, Dvorak AM, Finkelman FD, LeGros G, Paul WE. Basophils produce IL-4 and accumulate in tissues after infection with a Th2-inducing parasite. J Exp Med. 2004;200:507–517. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitzner W. Emphysema--a disease of small airways or lung parenchyma? N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1637–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1110635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed Hoesein FA, Zanen P, de Jong PA, van Ginneken B, Boezen HM, Groen HJ, Oudkerk M, de Koning HJ, Postma DS, Lammers JW. Rate of progression of CT-quantified emphysema in male current and ex-smokers: a follow-up study. Respir Res. 2013;14:55. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molofsky AB, Savage AK, Locksley RM. Interleukin-33 in Tissue Homeostasis, Injury, and Inflammation. Immunity. 2015;42:1005–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno JA, Ortega-Gomez A, Rubio-Navarro A, Louedec L, Ho-Tin-Noe B, Caligiuri G, Nicoletti A, Levoye A, Plantier L, Meilhac O. High-density lipoproteins potentiate alpha1-antitrypsin therapy in elastase-induced pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;51:536–549. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0103OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris DG, Huang X, Kaminski N, Wang Y, Shapiro SD, Dolganov G, Glick A, Sheppard D. Loss of integrin alpha(v)beta6-mediated TGF-beta activation causes Mmp12-dependent emphysema. Nature. 2003;422:169–173. doi: 10.1038/nature01413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motz GT, Eppert BL, Sun G, Wesselkamper SC, Linke MJ, Deka R, Borchers MT. Persistence of lung CD8 T cell oligoclonal expansions upon smoking cessation in a mouse model of cigarette smoke-induced emphysema. J Immunol. 2008;181:8036–8043. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.8036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair MG, Gallagher IJ, Taylor MD, Loke P, Coulson PS, Wilson RA, Maizels RM, Allen JE. Chitinase and Fizz family members are a generalized feature of nematode infection with selective upregulation of Ym1 and Fizz1 by antigen-presenting cells. Infect Immun. 2005;73:385–394. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.385-394.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemmar A, Raza H, Subramaniyan D, John A, Elwasila M, Ali BH, Adeghate E. Evaluation of the pulmonary effects of short-term nose-only cigarette smoke exposure in mice. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2012;237:1449–1456. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2012.012103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemmar A, Raza H, Subramaniyan D, Yasin J, John A, Ali BH, Kazzam EE. Short-term systemic effects of nose-only cigarette smoke exposure in mice: role of oxidative stress. Cellular physiology and biochemistry : international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology. 2013;31:15–24. doi: 10.1159/000343345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak ML, Koh TJ. Phenotypic transitions of macrophages orchestrate tissue repair. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:1352–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obot C, Lee K, Fuciarelli A, Renne R, McKinney W. Characterization of mainstream cigarette smoke-induced biomarker responses in ICR and C57Bl/6 mice. Inhal Toxicol. 2004;16:701–719. doi: 10.1080/08958370490476604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie BM. Nippostrongylus brasiliensis in mice: an explanation for the failure to induce worm expulsion from passively immunized animals. Int J Parasitol. 1971;1:161–167. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(71)90011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie CM, Forster RE, Blakemore WS, Morton JW. A standardized breath holding technique for the clinical measurement of the diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide. J Clin Invest. 1957;36:1–17. doi: 10.1172/JCI103402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H, Li Z, Yang XO, Chang SH, Nurieva R, Wang YH, Wang Y, Hood L, Zhu Z, Tian Q, Dong C. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1133–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels NS, Bracke KR, Maes T, Pilette C, Joos GF, Brusselle GG. The role of interleukin-6 in pulmonary and systemic manifestations in a murine model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Exp Lung Res. 2010;36:469–483. doi: 10.3109/01902141003739723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels RA, Rabe KF. Burden and clinical features of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Lancet. 2004;364:613–620. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16855-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]