Abstract

Serotonin receptors are targets of drug therapies for a variety of neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders. Cocaine inhibits the re-uptake of serotonin (5-HT), dopamine, and noradrenaline while caffeine blocks adenosine receptors and opens ryanodine receptors in the endoplasmic reticulum. We studied how 5-HT and adenosine affected spontaneous GABAergic transmission from thalamic reticular nucleus (TRN). We combined whole-cell patch clamp recordings of miniature inhibitory post-synaptic currents (mIPSCs) in ventrobasal (VB) thalamic neurons during local (puff) application of 5-HT in wild type (WT) or knockout mice lacking 5-HT2A receptors (5-HT2A −/−). Inhibition of mIPSCs frequency by low (10 μM) and high (100 μM) 5-HT concentrations was observed in VB neurons from 5-HT2A−/− mice. In WT mice, only 100 μM 5-HT significantly reduced mIPSCs frequency. In 5-HT2A−/− mice, NAN-190, a specific 5-HT1A antagonist, prevented the 100 μM 5-HT inhibition while blocking H-currents that prolonged inhibition during post-puff periods. The inhibitory effects of 100 μM 5-HT were enhanced in cocaine binge-treated 5-HT2A −/−. Caffeine binge treatment did not affect 5-HT-mediated inhibition. Our findings suggest that both 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors are present in presynaptic TRN terminals. Serotonergic-mediated inhibition of GABA release could underlie aberrant thalamocortical physiology described after repetitive consumption of cocaine.

Keywords: cocaine, caffeine, thalamic reticular nucleus, GABA, serotonin

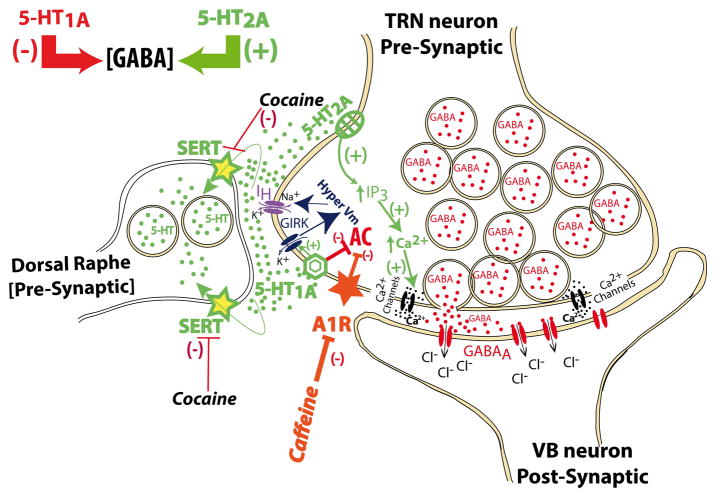

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Serotonin receptors and their associated intracellular pathways are conserved through evolution and have been described as targets of drug therapies for a variety of neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders (Nichols & Nichols, 2008), and alterations in 5-HT receptor levels have been demonstrated in human patients suffering from several psychiatric disorders (Lopez-Figueroa et al., 2004). Some of these neuropsychiatric disorders involve dysregulation (i.e., altered inhibitory processing) of cortical afferents from the ventrobasal thalamus (VB), which is normally regulated by inhibitory input from the thalamic reticular nucleus (TRN) (Llinas et al., 2002).

Hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated H-currents have been described to be activated in response to membrane hyperpolarization and contribute to the pacemaker depolarization that generates rhythmic activity of thalamcortical neurons (McCormick & Pape, 1990a). In VB neurons, 5-HT depolarized the membrane potential (Varela & Sherman, 2009) after changing the voltage-dependence of H-currents (Lee & McCormick, 1996) while increasing their amplitude (McCormick & Pape, 1990b). Serotonin can also depolarize (Sanchez-Vives et al., 1996; Monckton & McCormick, 2002) without affecting high-frequency (40Hz) action potential firing of GABAergic TRN neurons (Pinault & Deschenes, 1992). However, other authors showed that bath-applied 5-HT hyperpolarized VB neurons (Monckton & McCormick, 2002). TRN neurons express both 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors in their somas and dendrites (Cornea-Hébert et al., 1999; Rodriguez et al., 2011), but the role of serotonergic receptors at presynaptic GABAergic terminals of TRN are still unclear.

Caffeine (a well-known antagonist of IP3 receptors and an agonist of ryanodine receptors; McPherson et al., 1991) induces Ca2+ release from neuronal ryanodine intracellular stores (Garaschuk et al., 1997; Rankovic et al., 2010), and blocks adenosine receptors (Fredholm, 1995; Fredholm et al., 1999). Caffeine-induced Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum is known to trigger spontaneous GABA release in retinal amacrine cells (Warrier et al., 2005), as well as spontaneous Glutamate release in rat barrel cortex (Simkus & Stricker, 2002). Adenosine inhibits thalamocortical glutamate efferents reportedly activating presynaptic A1-type receptors (Fontanez & Porter, 2006), and has anti-oscillatory effects by blocking GABAergic transmission between TRN and VB neurons (Ulrich & Huguenard, 1995). The activation of presynaptic A1-receptors strongly suppressed 5-HT2A-mediated increases in spontaneous excitatory minis in cortical layer V pyramidal neurons (Stutzmann et al., 2001). However, little is known about the role of serotonergic 5-HT2A receptors on GABAergic transmission at a thalamic level.

In a previous study (Goitia et al., 2013), our group showed that cocaine binge administration led to considerable disinhibition of thalamic GABAergic transmission, while methylphenidate (MPH) did not induced such alterations. Given that MPH has no effect on serotonin transporters (Glowinski & Axelrod, 1966; Ross & Renyi, 1969; Ritz et al., 1987; Wise & Bozarth, 1987; Pan et al., 1994; Kuczenski & Segal, 1997; Segal & Kuczenski, 1999; Howes et al., 2000), we hypothesized that differences observed between these psychostimulants could be due to cocaine-dependent prolonged activation of serotonergic receptors expressed at the TRN nucleus level (Rodriguez et al., 2011).

Here we studied the presynaptic role of 5-HT on spontaneous GABAergic release from the TRN to the VB nucleus. We used focal (puff) application of 5-HT in slices from mice (WT or 5-HT2A −/−) treated with either cocaine or caffeine binge. Our results described for the first time a strong inhibition of miniature inhibitory post-synaptic current (mIPSC) frequency by 5-HT puff application onto VB neurons from WT or 5-HT2A −/− mice. Further characterization of local 5-HT effects suggests that cocaine-induced effects on thalamic GABAergic transmission are mediated by enhancing presynaptic 5-HT1A inhibitory action on the terminals of TRN neurons.

Our results suggest that inhibition of GABA release by 5-HT1A receptors is counteracted by the activation of 5-HT2A receptors. 5-HT1A receptors, through the activation of Gi/o protein, would inhibit adenylate cyclase while increasing the probability of the opening of G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRK), which would hyperpolarize the membrane potential, facilitating the opening of H-channels (Millan et al., 2008; Luscher et al., 1997). However, 5-HT2A-mediated activation of PLC and IP3, increasing intracellular [Ca2+], would facilitate GABA release (Millan et al., 2008). In addition, caffeine treatment would exert a blocking effect on A1 receptors (Fredholm, 1995; Fredholm et al., 1999), and remove the down-regulation of adenylate cyclase, partially compensating for the inhibitory effects of 5-HT1A receptors on GABA release.

Results presented here could help understand the role of serotonin receptors in multiple neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders.

Materials and Methods

Animals

We used male 129Sv/Ev mice (18–23 days old), either WT (from the Central Animal Facility at University of Buenos Aires) or knockout for the 5-HT2A receptor (Weisstaub et al., 2006). Principles of animal care were in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines and CONICET (2003), and approved by its authorities using OLAW/ARENA directives (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Psychostimulant administration

Cocaine (15 mg/kg) or caffeine (5 mg/kg) were administered using ‘binge-like’ protocols (3 i.p. injections, 1 h apart; Spangler et al., 1993; Urbano et al., 2009; Bisagno et al., 2010; Goitia et al., 2013), and control animals received saline injections equally timed. The binge-like administration pattern has been designed to mimic compulsive human cocaine abuse (Spangler et al., 1993).

Thalamocortical slices

Slices were obtained as previously described (Urbano et al., 2009; Bisagno et al., 2010; Goitia et al., 2013), 1 hr after the administration of the binge protocol. Mice were deeply anesthetized with tribromoethanol (250 mg/Kg; i.p.) followed by transcardial perfusion with ice-cold low sodium/antioxidants solution (composition in mM: 200 sucrose, 2.5 KCl, 3 MgSO4, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 20 D-glucose, 0.4 ascorbic acid, 2 pyruvic acid, 1 kynurenic acid, 1 CaCl2, and aerated with 95% O2/5% CO2, pH 7.4), and then decapitated. Thalamocortical brain slices (300 μm) were obtained gluing both hemispheres onto a vibrotome aluminum stage (Integraslicer 7550 PSDS, Campden Instruments, UK), submerged in a chamber containing chilled low-sodium/high-sucrose solution (composition in mM: 250 sucrose, 2.5 KCl, 3 MgSO4, 0.1 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 0.4 ascorbic acid, 3 myo-inositol, 2 pyruvic acid, 25 D-glucose, and 25 NaHCO3). Slices were cut sequentially and transferred to an incubation chamber at 37°C for 30 min containing a stimulant-free, low Ca2+/high Mg2+ normal ACSF (composition in mM: 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 3 MgSO4, 0.1 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 0.4 ascorbic acid, 3 myo-inositol, 2 pyruvic acid, 25 d-glucose, and 25 NaHCO3 and aerated with 95% O2/5% CO2, pH 7.4; Urbano et al., 2009, Bisagno et al., 2010).

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were made at room temperature (20–24°C) in normal ACSF with MgCl2 (1 mM) and CaCl2 (2 mM). Patch electrodes were made from borosilicate glass (2–3 MΩ) filled with a voltage-clamp high Cl-, high Cs+/QX314 solution (composition in mM: 110 CsCl, 40 HEPES, 10 TEA-Cl, 12 Na2phosphocreatine, 0.5 EGTA, 2 Mg-ATP, 0.5 Li-GTP, and 1 MgCl2. pH was adjusted to 7.3 with CsOH). To block Na+ currents and avoid postsynaptic action potentials, 10 mM N-(2,6-diethylphenylcarbamoylmethyl) triethylammonium chloride (QX-314) was added to the pipette solution (Urbano et al., 2009, Bisagno et al., 2010). Signals were recorded using a MultiClamp 700 amplifier commanded by pCLAMP 10.0 software (Molecular Devices, CA, USA). Data were filtered at 5 kHz, digitized and stored for off-line analysis. Capacitance and leak-currents were electronically subtracted using a standard pCLAMP P/N subtraction protocol. Spontaneous (non-electrically evoked) mIPSCs were recorded from VB neurons in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX, 3 μM), DL-2-Amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid sodium salt (DL-AP5, 50 μM) and 6-Cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione disodium (CNQX, 20 μM), and analyzed using Mini Analysis (Synaptosoft, Fort Lee, NJ, USA). Cumulative probability amplitude and inter-event interval curves were fitted to a single exponential equation: y = y0+ a*exp(-b*time); and mIPSC median amplitude and intervals (i.e., frequency−1) were compared across groups.

We used focal, puff application of 5-HT to minimize internalization of its receptors, which has been previously described by other authors using both agonists and antagonists (Gray & Roth, 2001). During puff experiments, 5-HT (10 or 100 μM) was focally applied, either alone or together with 1-(2-Methoxyphenyl)-4-(4-phthalimidobutyl) piperazine hydrobromide (NAN-190, 5-HT1A antagonist) or 4-Ethylphenylamino-1,2-dimethyl-6-methylaminopyrimidinium chloride (ZD-7288, a H-current, Ih inhibitor) through a patch pipette filled up with the same ACSF recording solution and connected to a Picospritzer II (General Valve Corporation, Fairfield, NJ) at ~50μm from the cell being patched. In each recording (2min. 30s long), mIPSC frequency was calculated in 15s time bins. The puff was applied at 1:00 to 1:30 min of recording, allowing us to determine pre-puff (0–1:00), puff (1:00–1:30), and post-puff (1:30–2:30) frequencies. Puff and post-puff frequencies are shown as normalized to the pre-puff frequency from each recorded VB neuron.

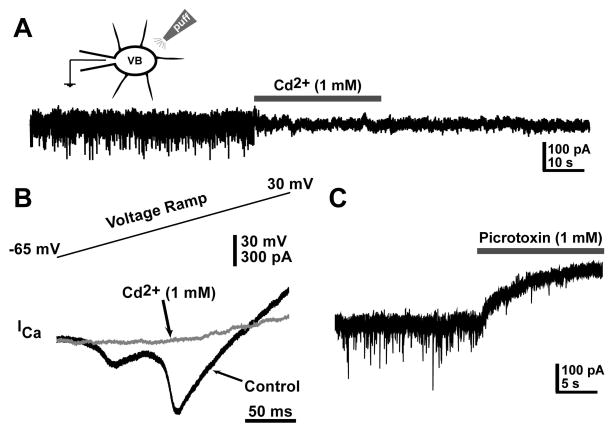

To test the effectiveness of puff applications on GABAergic synapses, we applied a VB holding potential between −70 and −90 mV (to enhance mIPSC amplitude by over 2 fold peak-to-peak noise amplitude during quantification), and applied ACSF containing CdCl2 (1mM), a Ca2+ channel blocker. This blocked mIPSCs and calcium currents recorded from postsynaptic VB neurons (Fig. 1A, B, respectively). We also confirmed that the mIPSCs being recorded were GABAergic through the puff application of picrotoxin, a GABA-A receptor inhibitor (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. Focal puff application of drugs can affect both ore- and postsynaptic components of GABA release from thalamic reticular nucleus.

(A) Whole-cell patch clamp recording of inhibitory post-synaptic miniatures currents (mIPSCs) in a VB neuron on which ACSF containing Cd2+ (1mM) was puffed, showing that blockade of presynaptic calcium channels (and therefore blockade of GABA release from TRN terminals) results in the lack of mIPSCs in the VB neuron. (B) Recording of a VB neuron before (black record) and during (gray record) a Cd2+ puff (1mM). Before the puff was applied, the voltage ramp triggered Ca2+ currents, both low-voltage and high-voltage activated, but these currents were not triggered when Cd2+ was applied, since it blocks Ca2+ channels in the postsynaptic neuron (VB neuron being patched). (C) Recording of a VB neuron on which ACSF containing picrotoxin (1mM) was puffed, showing that the mIPSCs recorded were GABAergic.

Statistical analysis

InfoStat software (Univ. Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina) was used for statistical comparisons. Statistics were performed using Student’s t-test or ANOVA and Tukey-Kramer or LSD Fisher multiple comparisons post hoc tests when applicable. Differences were considered significant if p < 0.05. Whenever the data did not comply with assumptions of the parametric tests, non-parametric Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed followed by paired comparisons. Data is presented as mean ± standard error of the mean.

Materials

Cocaine-HCl, Caffeine, DL-AP5, CNQX, 5-HT, picrotoxin, and NAN-190 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Argentina), TTX from Alomone labs. (Israel) and ZD 2788 from Tocris (USA).

Results

Local application of 5-HT inhibits GABA release from presynaptic reticular thalamic terminals from WT and 5-HT2A −/− mice

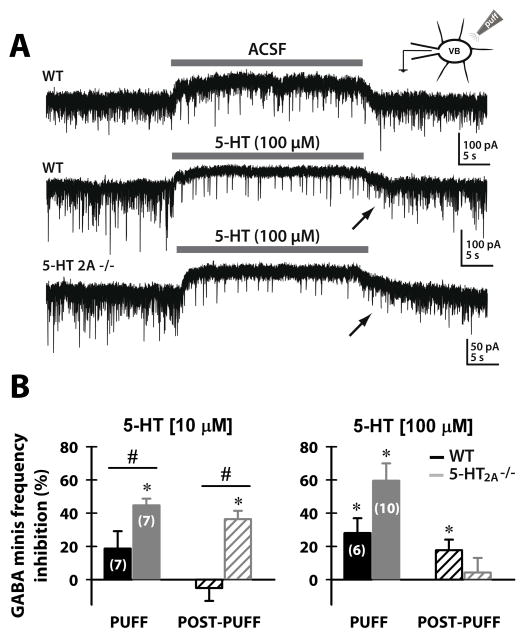

We studied the role of 5-HT on the frequency and amplitude of spontaneous GABAergic release from the TRN onto VB neurons. We used focal (puff) application of 5-HT in thalamocortical slices from mice (WT or 5-HT2A −/−) in the presence of DL-AP5 (NMDA receptor antagonist), CNQX (AMPA receptor antagonist), and TTX (voltage-gated sodium channel blocker). The puff pipette was located near the soma of VB neurons that were recorded in voltage-clamp whole-cell configuration, allowing us to study presynaptic terminals (Fig. 1). GABA mIPSC frequency was reduced during puff application of 5-HT compared to the pre-puff period, recovering during post-puff period (Fig. 2A; ACSF vs. 5-HT 100 μM). Although an apparent reduction in GABA mIPSC amplitude was observed during puff application of 5-HT, no significance was observed comparing median amplitudes before and during the puff (6.5%±0.8 reduction in median amplitudes puff vs. pre-puff; n=12 VB neurons; Student’s t-test, p>0.05).

Figure 2. GABA release from the TRN is reduced by focal 5-HT puff application in a dose-dependent manner.

(A) Representative whole-cell recordings showing mIPSCs from VB neurons from WT and 5-HT2A −/− mice. The uppermost record shows that an ACSF puff does not modify the frequency of mIPSCs in a VB neuron from a WT mouse, while in the middle and lower records ACSF with 5-HT 100μM reduced the appearance of mIPSCs in VB neurons from WT or 5-HT2A −/− mice. This effect was reversible, and soon after the puff ended, the frequency began to recover towards initial values (arrows). (B) Percent inhibition (relative to the pre-puff mIPSC frequency for each neuron) of mIPSCs during a 5-HT 10μM (left graph) or 100μM (right graph) 30 sec puff and during 1 min post-puff in VB neurons from WT (black bars) and 5-HT2A −/− mice (grey bars). During the puff (filled bars), the percent inhibition was higher for 5-HT2A −/− neurons at both 5-HT concentrations used (two-way ANOVA, p=0.0048). The percent inhibition was significant during the 5-HT 100μM puff both in cells from 5-HT2A −/− (Student’s t-test; p=0.0003) and WT (Student’s t-test; p=0.024) mice, but during the 5-HT 10μM puff, only in 5-HT2A −/− mice was the percent inhibition significantly different (Student’s t-test; p<0.0001). Post-puff (dashed bars): there were differences between WT and 5-HT2A −/− only for the lower 5-HT concentration tested (two-way ANOVA, simple effects; p=0.0006), that is, the percent inhibition was significant only for the 5-HT2A −/− mice (Student’s t-test; p=0.0006). After the 5-HT 100μM puff, the percent inhibition was significant only for the WT group (Student’s t-test; p=0.0379). *p < 0.05 compared to pre-puff frequency. # p < 0.05, WT vs. 5-HT2A −/−.

Low (10μM) and high (100μM) 5-HT concentration reduced GABA mIPSC frequency during puff (Fig. 2B, filled bars) in a larger percent in VB neurons from 5-HT2A −/− mice compared to WT (two-way ANOVA, p=0.0048). During the 5-HT 10μM puff, percent inhibition was significant only in VB neurons from 5-HT2A −/− mice (Student’s t-test; p<0.0001). During post-puff (Fig. 2B; dashed bars), there were also differences between WT and 5-HT2A −/− (two-way ANOVA, simple effects; p=0.0006). For 5-HT at 10μM, the percent inhibition during post-puff periods was significantly higher for the 5-HT2A −/− group (Student’s t-test; p=0.0006), while for 5-HT 100μM post-puff percent inhibition was significant only for the WT group (Student’s t-test; p=0.0379).

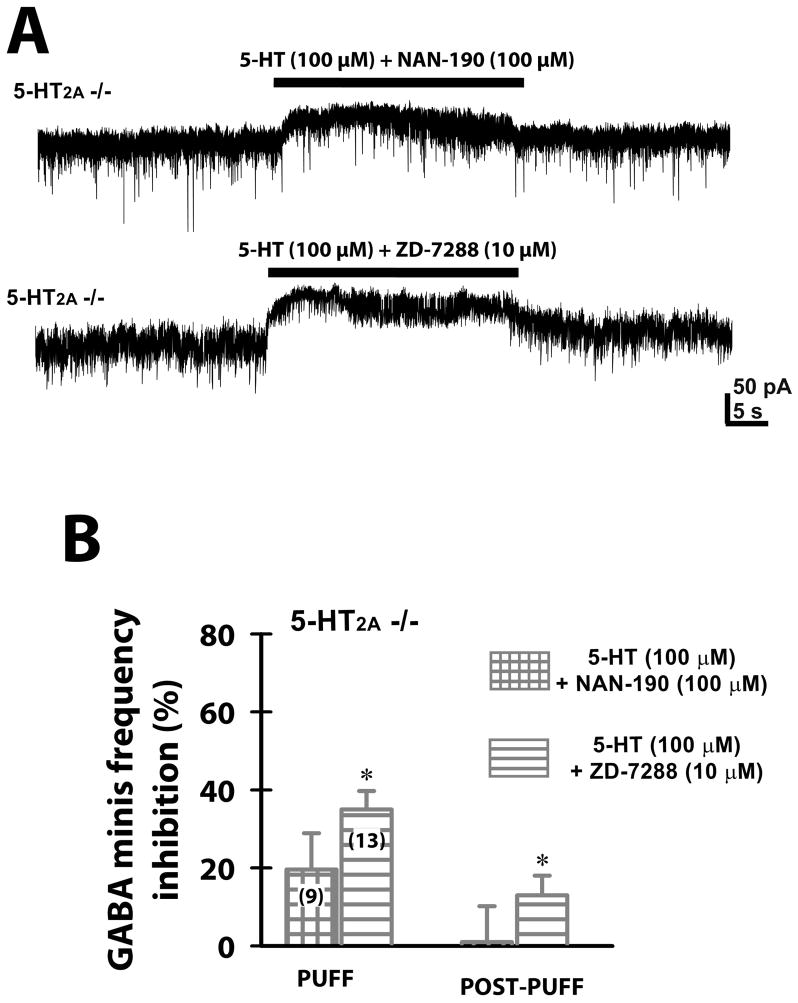

5-HT-dependent inhibition of GABA release in reticular thalamic terminals from 5-HT2A −/− mice was mediated by 5-HT1A receptors and H-currents

We then determined which 5-HT receptor mediated the 5-HT puff inhibitory effects on GABA release in slices from 5-HT2A −/− mice. We included the specific 5-HT1A antagonist NAN-190 (100 μM) in both the puff pipette and bath extracellular solutions, and observed no significant reduction in GABAergic mIPSC frequency during high concentration 5-HT (100 μM) puff application in 5-HT2A −/− mice (Fig. 3A, B). Applying the H-current blocker ZD-7288 (10 μM) significantly reduced the inhibitory effects of 5-HT 100 μM puff (Fig. 3A, B; One way-ANOVA; p=0.03 comparing 5-HT 100 μM vs. 5-HT 100 μM+ZD-7288 10 μM in VB neurons from 5-HT2A −/− mice). The post-puff effect of 5-HT 100 μM was not significantly affected by either NAN-190 or ZD-7288 application (One way-ANOVA; p>0.05).

Figure 3. Inhibitory effects of a local puff 5-HT on GABA release in TRN terminals from 5-HT2A −/− mice were mediated by 5-HT1A receptors and H-currents.

(A) Representative whole-cell recordings showing mIPSCs from VB neurons obtained from 5-HT2A −/− mice during 30 sec puff application of 5-HT 100μM+NAN-190 100μM, or 5-HT 100μM+ZD-7288 10 μM. (B) Percent inhibition (relative to the pre-puff mIPSC frequency for each neuron) of mIPSCs during a 5-HT 100μM (in presence or absence of NAN-190 100μM or ZD-7288 10μM) 30 sec puff and during 1min post-puff in VB neurons from 5-HT2A −/− mice. The percent inhibition was not significant during the 5-HT puff in the presence of NAN-190 (Student’s t-test; p>0.05). In the presence of ZD-7288, percent inhibition was significant during both puff (Student’s t-test; p=0.0105), and post-puff (Student’s t-test; p=0.0017 for 5-HT+ZD) periods. *p< 0.05 compared to pre-puff frequency.

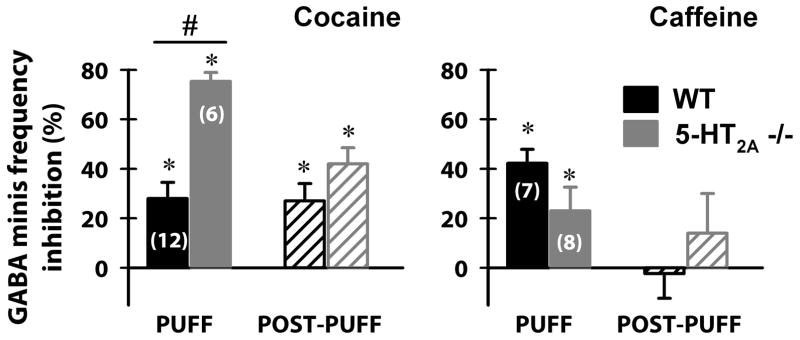

Cocaine and caffeine binge treatments altered the inhibitory effects of 5-HT 100 μM puff application on GABA release

We repeated the same experimental approach using slices from WT and 5-HT2A −/− mice treated with either a cocaine binge (3×15 mg/kg, 1 hour apart; i.p.), or a caffeine binge (3×5 mg/kg, 1 hour apart; i.p.) (Fig. 4). Although percent inhibition was significant during the puff for cells from both cocaine-treated WT and 5-HT2A −/− mice (Student’s t-test: p<0.05), cells from cocaine-binge treated 5-HT2A −/− mice manifested a significantly larger inhibition than WT (Fig. 4, left plot; Student’s t-test, p<0.001, cocaine binge treated WT vs. 5-HT2A −/−). Importantly, cocaine binge induced a greater post-puff inhibition only in 5-HT2A −/− mice (One-way ANOVA: p=0.015; comparing post-puff in 5-HT2A −/− vs. post-puff from cocaine binge treated 5-HT2A −/−).

Figure 4. Cocaine and caffeine binge treatments altered the inhibitory effects of 5-HT 100 μM puff application on GABA release from TRN terminals in cells from 5-HT2A −/− mice.

Percent inhibition (relative to the pre-puff mIPSC frequency for each neuron) of mIPSCs during a 5-HT 100μM 30 sec puff and during 1min post-puff in VB neurons from WT (black bars) and 5-HT2A −/− (grey bars) mice treated with cocaine binge (3×15 mg/kg, 1 hour apart; i.p.) or caffeine binge (3×5 mg/kg, 1 hour apart; i.p.), and sacrificed 1 hr after receiving the last injection. The percent inhibition was significantly different during the puff for both cocaine-treated WT and 5-HT2A −/− mice (Student’s t-test: p<0.05), with significantly higher inhibition in cells recorded in VB neurons from cocaine binge treated 5-HT2A −/− mice (Student’s t-test, p<0.001, cocaine binge treated WT vs. 5-HT2A −/−). Post-puff inhibition levels were greater in VB neurons from cocaine-treated 5-HT2A −/− mice (One-way ANOVA: p=0.015; comparing post-puff in 5-HT2A −/− vs. post-puff from cocaine binge treated 5-HT2A −/−). Caffeine binge treated WT and 5-HT2A −/− showed significant inhibition in GABA mIPSC frequency only during the 5-HT 100 μM puff (Student’s t-test: p<0.05), but not during post-puff periods (Student’s t-test: p>0.05). Mean inhibition during 5-HT 100 μM puff was reduced in VB neurons from caffeine binge treated 5-HT2A−/− mice (One-way ANOVA: p<0.001; comparing puff in 5-HT2A −/− vs. puff from caffeine binge treated 5-HT2A −/−). *p<0.05 compared to pre-puff frequency. # p<0.001 comparing WT vs. 5-HT2A −/− groups.

On the other hand, caffeine binge treated WT and 5-HT2A −/− showed significant inhibition in GABA mIPSC frequency only during 5-HT 100μM puff (Student’s t-test: p<0.05), but not during post-puff periods (Student’s t-test: p>0.05) (Fig. 4, right plot). Caffeine reduced 5-HT-mediated inhibition of GABA mIPSC frequency in 5-HT2A−/− mice (Fig. 4, right plot; One-way ANOVA: p<0.001; comparing puff in 5-HT2A −/− vs. puff from caffeine binge treated 5-HT2A −/−).

Discussion

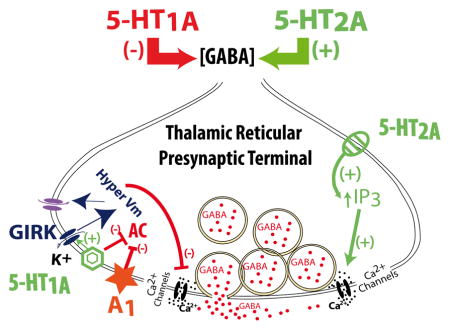

Results presented here demonstrate that both 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors are located in the presynaptic terminals of TRN neurons (Fig. 5). According to the canonical intracellular pathways of these receptors (Millan et al., 2008), the inhibitory role of 5-HT1A receptors on synaptic GABA release could be mediated by their inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and the activation of H-currents. Adenosine receptor type 1 was previously described in these neurons (Ulrich & Huguenard, 1995; Dixon et al., 1996), and would also use this intracellular pathway, occluding the activation of 5-HT1A receptors. On the other hand, 5-HT2A receptors would activate phospholipase C (PLC) pathways, increasing intracellular [Ca2+] and its concomitant augmentation of GABA release (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Representative cartoon of the probable intracellular pathways underlying the results found in this study.

Serotonin release from dorsal Raphe nucleus afferents (Rodríguez et al., 2011) are known to act on presynaptic 5-HT1A receptors activating a Gi/o protein that would inhibit adenylate cyclase while increasing the probability of the opening of G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRK) (Millan et al., 2008; Luscher et al., 1997). In addition, type 1 adenosine receptors (A1) that are highly expressed in thalamic neurons (Ulrich & Huguenard, 1995; Dixon et al., 1996) have been also described to activate GIRK channels (Luscher et al., 1997). The prolonged activation of GIRK currents would hyperpolarize the membrane potential, facilitating the opening of H-channels. The opening of additional H-channels would have a shunting effect, reducing Ca2+ spike summation (Berger et al., 2003), ultimately resulting in a reduction of GABA release. On the other hand, 5-HT2A-mediated activation of PLC and IP3, increasing intracellular [Ca2+], would facilitate GABA release (Millan et al., 2008). Caffeine treatment would exert a blocking effect on A1 receptors (Fredholm, 1995; Fredholm et al., 1999), and remove the down-regulation of adenylate cyclase, partially compensating for the inhibitory effects of 5-HT1A receptors on GABA release.

Here, we used focally applied 5-HT onto reticular afferents and VB neurons. This experimental approach minimized desensitization followed by internalization of 5-HT receptors during minutes to hour-long bath application of agonists/antagonists (Gray & Roth, 2001). Inhibitory effects of 5-HT on GABA mIPSC frequency suggested that 5-HT receptors were acting presynaptically. Combining pharmacological tools with mice lacking 5-HT2A receptors (5-HT2A−/−; Weisstaub et al., 2006), we described inhibitory 5-HT1A receptors at presynaptic terminals from 5-HT2A−/− mice. The lower inhibitory effects of 5-HT 100 μM puff in VB neurons from WT mice suggested that 5-HT2A receptors could counteract the inhibitory actions of 5-HT1A. Only 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors were involved in the modulation of GABA release from presynaptic terminals of TRNs (Fig. 5), since applying the 5-HT1A receptor specific antagonist NAN-190 in slices from 5-HT2A−/− mice yielded no effect of a 5-HT 100 μM puff.

These results are consistent with previous immunohistochemical reports describing the expression of both 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors and 5-HT transporter (SERT)-containing afferent fibers at the somas of TRNs (Rodriguez et al., 2011). At the somatic level of these neurons, it has been reported that bath applied 5-HT depolarized VB cells (Sanchez-Vives et al. 1996; Monckton & McCormick 2002) without affecting high frequency (40Hz) action potential firing (Pinault & Deschenes, 1992).

In other brain structures, 5-HT1A inhibitory and 5-HT2A excitatory effects on synaptic release have also been reported. In rat pyriform cortex, bath applied 5-HT (100 μM) and 4-Iodo-2,5-dimethoxy-α-methylbenzeneethanamine hydrochloride (DOI, a 5-HT2A specific agonist; 10 μM) increased GABAergic mIPSC frequency in pyramidal neurons trough activation of 5-HT2A receptors (Marek & Aghajanian, 1996). In prefrontal cortical slices from rats in the third postnatal week (age range similar to the one used in this study), bath-applied 5-HT initially elicited a depolarization (pharmacologically determined to be mediated by 5HT2A receptors) of layer V pyramidal neurons then gradually shifted to a long duration hyperpolarization period mediated by 5-HT1A receptors (Béïque et al., 2004). 5-HT2 receptor activation has been shown to facilitate GABA release, while 5-HT1 receptors were involved in preventing such activation (Fink & Göthert, 2007). Bath-applied 5-HT inhibited Ca2+ currents of caudal Raphe neurons through the activation of 5-HT1A receptors (Bayliss et al., 1997). Therefore, 5-HT would inhibit action potential afterhyperpolarization, inducing an increase in action potential frequency in these cells. The inhibitory effects of 5-HT1A are mediated by both neuronal hyperpolarization and inhibition of adenylate cyclase (De Vivo & Maayani, 1986).

Presynaptic actions of 5-HT2A receptors described in our study confirm previously accepted paradigms in which only 5-HT1A receptors were considered to be located at presynaptic sites, while 5-HT2A receptors are thought to be localized in postsynaptic structures (Nichols & Nichols, 2008). Nevertheless, understanding the role of 5-HT1A receptors modulating GABAergic transmission is relevant to their role in multiple psychiatric and neurological disorders. In postmortem schizophrenia patients an increase in 5-HT1A receptor density in prefrontal cortex has been reported (Bantick et al., 2001). Activation of 5-HT1A receptors produced antidepressant-like effects in animal models (Lucki, 1991), and in knockout mice lacking 5-HT1A receptors have been previously used as genetic models of anxiety disorder (Toth, 2003).

Our results also described a key role for H-currents on the presynaptic inhibitory effects mediated by a 5-HT puff. Using 5-HT2A−/− animals, we observed significantly lower inhibitory effects during 100 μM 5-HT puff application after blocking H-currents with ZD-7288. Basal activation of H-currents would normally inhibit GABA release, probably by shunting membrane resistance as described in distal-apical dendritic compartments of cortical pyramidal neurons (Berger et al., 2003). Morphological and functional experiments have confirmed the presence of H-channels negatively influencing GABA release from rodent globus pallidus neurons (Boyes et al., 2007). Furthermore, H-currents can be tonically activated in presynaptic terminals, reducing the spontaneous release of mIPSCs while inactivating Ca2+-gated channels (Huang et al., 2011). 5-HT2 receptors reduced H-currents and influenced the number of those channels (Liu et al., 2003).

The inhibitory 5-HT puff effects were altered after cocaine or caffeine binge treatments. We observed that a cocaine binge prolonged 5-HT-mediated inhibition during post-puff periods in 5-HT2A−/− mice, suggesting an enhancement of 5-HT1A-mediated inhibitory effects. Repetitive cocaine administration attenuated the ability of 5-HT to enhance spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents in the medial prefrontal cortex through impairment of 5-HT2A coupling to its intracellular pathways (Huang et al., 2009), which would potentiate a 5-HT1A-mediated inhibition like the one presented here. The fact that a cocaine binge did not affect 5-HT puff-mediated inhibition during GABA release from cells in WT mice may be due to internalization/downregulation processes of 5-HT1A receptors, previously described in rats (Perret et al., 1998). Cocaine-induced desensitization of 5-HT1A autoreceptors was observed in Raphe nucleus after chronic fluoxetine treatment (an antagonist of SERT) (Le Poul et al., 2000). 5-HT1A desensitization is known to occur after the prolonged activation of G protein intracellular pathways (Castro et al., 2003; Shi et al., 2007), which eventually can result in the internalization of those receptors (Gray & Roth, 2001).

Results presented here described a novel mechanism showing that GABA release can indeed be modulated by the interaction between 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors, which supports our previous hypothesis underlying differential effects of cocaine and methylphenidate on TRN synaptic terminals (Goitia et al., 2013). Furthermore, the prolonged inhibition of GABA release described here after cocaine binge treatment may desensitize 5-HT1A receptors, allowing 5-HT2A to play a greater role, resulting in higher GABAergic mIPSC frequencies as described by our group (Urbano et al., 2009; Bisagno et al., 2010; Goitia et al., 2013). Homeostatic compensatory mechanisms (Mee et al., 2004; Baines, 2005) of GABAergic transmission would also explain the previously observed prolonged activation of this inhibitory synapse after cocaine binge treatment (Urbano et al., 2009; Bisagno et al., 2010; Goitia et al., 2013). Serotonergic mediated inhibition in mice treated with cocaine may trigger compensation at the somatic TRN level, reducing the expression of inhibitory 5-HT1A receptors. Further experiments are needed to support this hypothesis.

Adenosine type 1 receptors are present in the somatosensory thalamocortical system (Fontanez & Porter, 2006), that exert robust antioscillatory effects by simultaneously decreasing excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission (Ulrich & Huguenard, 1995). The present study involved a binge treatment with a low caffeine dose (5 mg/kg). A previous study that measured brain concentration of caffeine after an intraperitoneal administration (20mg/kg) reported that caffeine brain levels reached up to 100μM (Hepper & Davies, 1999). Therefore it might be estimated that our protocol using 3× 5mg/kg of caffeine might have produced caffeine brain levels in the tens of micromolar range. Such caffeine concentration levels have been ascribed to adenosine receptor blockage (Fredholm, 1995; Fredholm et al., 1999), rather than acting through the inhibition of phosphodiesterases (Aoyama et al., 2011), or the opening of IP3 receptors expressed in TRN (Garaschuk et al., 1997; Rankovic et al., 2010). Furthermore, ryanodine receptors expressed in both TRN (Budde et al., 2000) and VB neurons (Coulon et al., 2009) might also be involved in caffeine modulation of GABA release shown in this study.

At the postsynaptic level, adenosine receptors have been described to inhibit H-currents in relay thalamic neurons (Pape, 1992). Also, adenosine and serotonin receptors enhanced leak potassium currents (Pape, 1992; Coulon et al., 2010). Further experiments are still needed to clarify 5-HT and caffeine role of the intrinsic properties of postsynaptic thalamocortical neurons.

In cortical pyramidal neurons, adenosine A1 receptors preferentially affect 5-HT2A-mediated enhancement of spontaneous postsynaptic excitatory synaptic events (Stutzmann et al., 2001), contrary to what we report here. In our hands, caffeine-mediated inhibition of adenosine receptors located in presynaptic TRN terminals prevented the inhibitory effects of 5-HT1A receptors during 100 μM puffs in slices from 5-HT2A−/− mice. Therefore, only in the absence of 5-HT2A receptors was caffeine able to affect 5-HT mediated control of GABA release. One likely mechanism for these results could be due to blockade of adenosine A1 receptors after caffeine treatment (Fredholm, 1995; Fredholm et al., 1999), releasing their down-regulation of adenylate cyclase. An increase in the abundance of available adenylate cyclase might partially compensate for the previously observed inhibitory effects of 5-HT1A receptors on GABA release at 5-HT2A −/− reticular synaptic terminals.

The present work highlights the role of 5-HT in modulating GABA release at VB thalamic nucleus during normal physiological activity. In addition, novel 5-HT-mediated mechanisms described here might help explain the long-lasting, detrimental effects of cocaine and caffeine dysregulation of thalamic GABAergic transmission. Such mechanisms could induce permanent changes in sensory thalamic processing.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank María Eugenia Martin, Daniela De Luca and Paula Felman for their excellent technical and administrative assistance. Dr. Bisagno has been authorized to study drug abuse substances in animal models by A.N.M.A.T. (National Board of Medicine Food and Medical Technology, Ministerio de Salud, Argentina). The experiments included in this study comply with the current laws of Argentina. Authors have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to review their data if requested. Authors report no financial conflict of interest, or otherwise, related directly or indirectly to this study. This work was supported by grants from FONCYT-Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica; BID 1728 OC.AR. PICT-2012-1769 and UBACYT 2014-2017 #20120130101305BA (to Dr. Urbano) and FONCYT-Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica; BID 1728 OC.AR. PICT 2012-0924 Argentina (to Dr. Bisagno). In addition, this work was supported NIH award R01 NS020246, and by core facilities of the Center for Translational Neuroscience supported by NIH award P20 GM103425 and P30 GM110702 (to Dr. Garcia-Rill).

Abbreviations

- AC

adenylyl cyclase

- ACSF

artificial; cerebrospinal fluid

- ADHD

attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- CNQX

6-Cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione disodium salt hydrate

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- DL-AP5

DL-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid

- GIRK

G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels

- 5-HT

serotonin

- mIPSC

spontaneous miniature inhibitory post-synaptic current

- MPH

methylphenidate-HCl

- NET

norepinephrine transporter

- PLC

phospholipase C

- SERT

serotonin transporter

- TRN

thalamic reticular nucleus

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- VB

ventrobasal nucleus

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: NONE

References

- Aoyama K, Matsumura N, Watabe M, Wang F, Kikuchi-Utsumi K, Nakaki T. Caffeine and uric acid mediate glutathione synthesis for neuroprotection. Neuroscience. 2011;181:206–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baines RA. Neuronal homeostasis through translational control. Mol Neurobiol. 2005;32(2):113–121. doi: 10.1385/MN:32:2:113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantick RA, Deakin JF, Grasby PM. The 5-HT1A receptor in schizophrenia: a promising target for novel atypical neuroleptics? J Psychopharmacol. 2001;15(1):37–46. doi: 10.1177/026988110101500108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss DA, Li YW, Talley EM. Effects of serotonin on caudal raphe neurons: inhibition of N- and P/Q-type calcium channels and the afterhyperpolarization. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77(3):1362–74. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béïque JC, Campbell B, Perring P, Hamblin MW, Walker P, Mladenovic L, Andrade R. Serotonergic regulation of membrane potential in developing rat prefrontal cortex: coordinated expression of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)1A, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT7 receptors. J Neurosci. 2004;24(20):4807–4817. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5113-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyes J, Bolam JP, Shigemoto R, Stanford IM. Functional presynaptic HCN channels in the rat globus pallidus. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25(7):2081–2092. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger T, Senn W, Lüscher HR. Hyperpolarization activated current Ih disconnects somatic and dendritic spike initiation zones in layer V pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:2428–2437. doi: 10.1152/jn.00377.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisagno V, Raineri M, Peskin V, Wikinski SI, Uchitel OD, Llinás RR, Urbano FJ. Effects of T-type calcium channel blockers on cocaine-induced hyperlocomotion and thalamocortical GABAergic abnormalities in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;212(2):205–214. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1947-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budde T, Sieg F, Braunewell KH, Gundelfinger ED, Pape HC. Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release supports the relay mode of activity in thalamocortical cells. Neuron. 2000;26(2):483–492. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornea-Hébert V, Riad M, Wu C, Singh SK, Descarries L. Cellular and subcellular distribution of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor in the central nervous system of adult rat. J Comp Neurol. 1999;409(2):187–209. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990628)409:2<187::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro M, Diaz A, del Olmo E, Pazos A. Chronic fluoxetine induces opposite changes in G protein coupling at pre and postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors in rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 2003;44(1):93–101. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00340-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulon P, Herr D, Kanyshkova T, Meuth P, Budde T, Pape HC. Burst discharges in neurons of the thalamic reticular nucleus are shaped by calcium-induced calcium release. Cell Calcium. 2009;46(5–6):333–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulon P, Kanyshkova T, Broicher T, Munsch T, Wettschureck N, Seidenbecher T, Meuth SG, Offermanns S, Pape HC, Budde T. Activity modes in thalamocortical relay neurons are modulated by G(q)/G(11) family G-proteins - serotonergic and glutamatergic signaling. Front Cell Neurosci. 2010;4:132. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2010.00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vivo M, Maayani S. Characterization of the 5-hydroxytryptamine1a receptor-mediated inhibition of forskolin-stimulated adenylate cyclase activity in guinea pig and rat hippocampal membranes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1986;238(1):248–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon AK, Gubitz AK, Sirinathsinghji DJ, Richardson PJ, Freeman TC. Tissue distribution of adenosine receptor mRNAs in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:1461–1468. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanez DE, Porter JT. Adenosine A1 receptors decrease thalamic excitation of inhibitory and excitatory neurons in the barrel cortex. Neuroscience. 2006;137(4):1177–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB. Astra Award Lecture. Adenosine, adenosine receptors and the actions of caffeine. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1995;76(2):93–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1995.tb00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, Bättig K, Holmén J, Nehlig A, Zvartau EE. Actions of caffeine in the brain with special reference to factors that contribute to its widespread use. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51(1):83–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink KB, Göthert M. 5-HT receptor regulation of neurotransmitter release. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59(4):360–417. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaschuk O, Yaari Y, Konnerth A. Release and sequestration of calcium by ryanodine-sensitive stores in rat hippocampal neurones. J Physiol (Lond) 1997;502(Pt 1):13–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.013bl.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, Roth BL. Paradoxical trafficking and regulation of 5-HT(2A) receptors by agonists and antagonists. Brain Res Bull. 2001;56(5):441–451. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00623-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glowinski J, Axelrod J. Effects of drugs on the disposition of H-3-norepinephrine in the rat brain. Pharmacol Rev. 1966;18(1):775–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goitia B, Raineri M, González LE, Rozas JL, Garcia-Rill E, Bisagno V, Urbano FJ. Differential effects of methylphenidate and cocaine on GABA transmission in sensory thalamic nuclei. J Neurochem. 2013;124(5):602–612. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppert KE, Davies ML. Simultaneous determination of caffeine from blood, brain and muscle using microdialysis in an awake rat and the effect of caffeine on rat activity. Cur Separations. 1999;18:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Huang CC, Liang YC, Lee CC, Wu MY, Hsu KS. Repeated cocaine administration decreases 5-HT(2A) receptor-mediated serotonergic enhancement of synaptic activity in rat medial prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(8):1979–1992. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Lujan R, Kadurin I, Uebele VN, Renger JJ, Dolphin AC, Shah MM. Presynaptic HCN1 channels regulate Cav3.2 activity and neurotransmission at select cortical synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(4):478–486. doi: 10.1038/nn.2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R, Segal DS. Effects of methylphenidate on extracellular dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine: comparison with amphetamine. J Neurochem. 1997;68(5):2032–2037. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68052032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmin A, Johansson B, Zvartau EE, Fredholm BB. Caffeine, acting on adenosine A(1) receptors, prevents the extinction of cocaine-seeking behavior in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290(2):535–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Poul E, Boni C, Hanoun N, Laporte AM, Laaris N, Chauveau J, Hamon M, Lanfumey L. Differential adaptation of brain 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors and 5-HT transporter in rats treated chronically with fluoxetine. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39(1):110–122. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MY, Yan QS, Coffey LL, Reith ME. Extracellular dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin in the nucleus accumbens of freely moving rats during intracerebral dialysis with cocaine and other monoamine uptake blockers. J Neurochem. 1996;66:559–568. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66020559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Bunney EB, Appel SB, Brodie MS. Serotonin reduces the hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) in ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons: involvement of 5-HT2 receptors and protein kinase C. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90(5):3201–3212. doi: 10.1152/jn.00281.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas RR, Leznik E, Urbano FJ. Temporal binding via cortical coincidence detection of specific and nonspecific thalamocortical inputs: a voltage-dependent dye-imaging study in mouse brain slices. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(1):449–454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012604899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Figueroa AL, Norton CS, López-Figueroa MO, Armellini-Dodel D, Burke S, Akil H, López JF, Watson SJ. Serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, and 5-HT2A receptor mRNA expression in subjects with major depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(3):225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucki I. Behavioral studies of serotonin receptor agonists as antidepressant drugs. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52(Suppl):24–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher C, Jan LY, Stoffel M, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. G protein coupled inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRKs) mediate postsynaptic but not presynaptic transmitter actions in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1997;19:687–695. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek GJ, Aghajanian GK. LSD and the phenethylamine hallucinogen DOI are potent partial agonists at 5-HT2A receptors on interneurons in rat piriform cortex. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278(3):1373–1382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson PS, Kim YK, Valdivia H, Knudson CM, Takekura H, Franzini-Armstrong C, Coronado R, Campbell KP. The brain ryanodine receptor: a caffeine-sensitive calcium release channel. Neuron. 1991;7(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90070-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Pape HC. Properties of a hyperpolarization-activated cation current and its role in rhythmic oscillation in thalamic relay neurones. J Physiol (Lond) 1990a;431:291–318. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Pape HC. Noradrenergic and serotonergic modulation of a hyperpolarization-activated cation current in thalamic relay neurones. J Physiol (Lond) 1990b;431:319–342. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mee CJ, Pym EC, Moffat KG, Baines RA. Regulation of neuronal excitability through pumilio-dependent control of a sodium channel gene. J Neurosci. 2004;24(40):8695–8703. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2282-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ, Marin P, Bockaert J, Mannoury la Cour C. Signaling at G-protein-coupled serotonin receptors: recent advances and future research directions. Trends in Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29(9):454–464. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monckton JE, McCormick DA. Neuromodulatory role of serotonin in the ferret thalamus. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87(4):2124–2136. doi: 10.1152/jn.00650.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols DE, Nichols CD. Serotonin receptors. Chem Rev. 2008;108(5):1614–1641. doi: 10.1021/cr078224o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan D, Gatley SJ, Dewey SL, Chen R, Alexoff DA, Ding YS, Fowler JS. Binding of bromine-substituted analogs of methylphenidate to monoamine transporters. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;264(2):177–182. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)00460-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape HC. Adenosine promotes burst activity in guinea-pig geniculocortical neurones through two different ionic mechanisms. J Physiol (Lond) 1992;447:729–753. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perret G, Schluger JH, Unterwald EM, Kreuter J, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Downregulation of 5-HT1A receptors in rat hypothalamus and dentate gyrus after “binge” pattern cocaine administration. Synapse. 1998;30(2):166–171. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199810)30:2<166::AID-SYN6>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinault D, Deschênes M. Control of 40-Hz firing of reticular thalamic cells by neurotransmitters. Neuroscience. 1992;51(2):259–268. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90313-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankovic V, Ehling P, Coulon P, Landgraf P, Kreutz MR, Munsch T, Budde T. Intracellular Ca2+ release-dependent inactivation of Ca2+ currents in thalamocortical relay neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31(3):439–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz MC, Lamb RJ, Goldberg SR, Kuhar MJ. Cocaine receptors on dopamine transporters are related to self-administration of cocaine. Science (New York, NY) 1987;237(4819):1219–1923. doi: 10.1126/science.2820058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez JJ, Noristani HN, Hoover WB, Linley SB, Vertes RP. Serotonergic projections and serotonin receptor expression in the reticular nucleus of the thalamus in the rat. Synapse. 2011;65(9):919–928. doi: 10.1002/syn.20920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross SB, Renyi AL. Inhibition of the uptake of tritiated 5-hydroxytryptamine in brain tissue. Eur J Pharmacol. 1969;7(3):270–277. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(69)90091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Vives MV, Bal T, Kim U, von Krosigk M, McCormick DA. Are the interlaminar zones of the ferret dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus actually part of the perigeniculate nucleus? J Neurosci. 1996;16(19):5923–5941. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-05923.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal DS, Kuczenski R. Escalating dose-binge treatment with methylphenidate: role of serotonin in the emergent behavioral profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291(1):19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Zemaitaitis B, Muma NA. Phosphorylation of Galpha11 protein contributes to agonist-induced desensitization of 5-HT2A receptor signaling. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71(1):303–313. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.028241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkus CR, Stricker C. The contribution of intracellular calcium stores to mEPSCs recorded in layer II neurones of rat barrel cortex. J Physiol (Lond) 2002;545(Pt 2):521–535. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.022103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler R, Unterwald EM, Kreek MJ. “Binge” cocaine administration induces a sustained increase of prodynorphin mRNA in rat caudate-putamen. Brain Res Molec Brain Res. 1993;19(4):323–327. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90133-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutzmann GE, Marek GJ, Aghajanian GK. Adenosine preferentially suppresses serotonin2A receptor-enhanced excitatory postsynaptic currents in layer V neurons of the rat medial prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience. 2001;105(1):55–69. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth M. 5-HT1A receptor knockout mouse as a genetic model of anxiety. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;463(1–3):177–184. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01280-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich D, Huguenard JR. Purinergic inhibition of GABA and glutamate release in the thalamus: implications for thalamic network activity. Neuron. 1995;15(4):909–918. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbano FJ, Bisagno V, Wikinski SI, Uchitel OD, Llinás RR. Cocaine acute “binge” administration results in altered thalamocortical interactions in mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(8):769–776. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela C, Sherman SM. Differences in response to serotonergic activation between first and higher order thalamic nuclei. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(8):1776–1786. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrier A, Borges S, Dalcino D, Walters C, Wilson M. Calcium from internal stores triggers GABA release from retinal amacrine cells. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94(6):4196–4208. doi: 10.1152/jn.00604.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisstaub NV, Zhou M, Lira A, Lambe E, González-Maeso J, Hornung JP, Sibille E, Underwood M, Itohara S, Dauer WT, Ansorge MS, Morelli E, Mann JJ, Toth M, Aghajanian G, Sealfon SC, Hen R, Gingrich JA. Cortical 5-HT2A receptor signaling modulates anxiety-like behaviors in mice. Science. 2006;313(5786):536–540. doi: 10.1126/science.1123432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA, Bozarth MA. A psychomotor stimulant theory of addiction. Psychol Rev. 1987;94(4):469–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]