INTRODUCTION

Erosion of trust in the medical profession is an important issue which cannot be ignored.[1] While experts have, for long, exhorted doctors to self-reflect on the state of their profession, its priorities, and its future directions, this has been done in a generic manner. In this editorial, we use chronic disease management philosophy as a framework to discuss action which can be taken to rebuild lost trust.

We suggest three actionable items which can recreate this trust and resolve the issue. The 3I strategy, as we term it, proposes interaction, information, and involvement as the three pillars of action. Interaction or communication between physician and patient can be strengthened by practicing “therapy by the ear.” “Information” implies that equipoise should be achieved between physician and patient's information levels, to minimize distrust. Involvement of all stakeholders as proposed in Atreya's quadruple (physician, patient, drugs, and attendants) helps facilitate this process.

CHRONIC DISEASE

The Indian medical profession has a humungous task at its hands. Underresourced and understaffed, it struggles to handle the preexisting burden of acute, mostly communicable disease. At the same time, the profession's capacity is being overstretched by the rapidly increasing noncommunicable diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, respiratory illness, and cancer. Some of these conditions, such as diabetes, seem to have become endemic to the country and show no signs of abating.[2]

The patient with chronic disease has a long, almost indefinite interaction with the health-care system and with the health-care professionals. Such a long-term relationship can be fruitful only if there is a bond of trust between both patient and physician and between patient and the health-care system. Kane and Calnan's call for building trust,[1] therefore, assumes greater significance in a country with a high burden of metabolic disease.

CHRONIC DISEASE MANAGEMENT

Chronic disease management, especially diabetes care, is marked by a shared responsibility.[3] Unlike in acute illness, the person living with diabetes shoulders the major part of responsibility in managing diabetes. This responsibility is fulfilled by a process of informed and shared decision-making. Patient and provider share the responsibility of taking management decisions. This is done after the provider has ensured information equipoise between herself and the patient by providing all relevant knowledge to him.[4]

INTERACTION: THERAPY BY THE EAR

The transfer of knowledge and information is a two-way process, which includes empathic history taking, so as to understand the biomedical as well as psychosocial aspects of the patient's health. In the context of diabetes, this has been termed “diabetes therapy by the ear.”[5] The concept of “therapy by the ear” has been popularized by the doctor author Abraham Verghese, in his book “Cutting for Stone.”[6]

We suggest therapy by the ear as a means of rebuilding the eroded trust that the medical profession experiences today. This implies a bidirectional relationship, in which the patient and physician listen actively to each other, thus ensuring effective communication. Physicians should make a proactive effort to spend more time on history taking and active listening (and perhaps less energy on ordering irrelevant investigations). At the same time, social marketing campaigns should encourage patients to communicate effectively with their doctors.

It must be clarified that such communication skills are bidirectional and involve not only rights but also responsibilities as well. While the patient has the right to ask questions, obtain information, and seek clarification, he/she also shoulders the responsibility of understanding the natural history, course, and prognosis of disease, as well as adhering to prescribed interventions, both diagnostic and therapeutic.

Therapy by the ear places the onus of rebuilding trust on both the medical profession and patients (or community), i.e., on both provider and customer. This approach will lead to a shared, and balanced, distribution of responsibility and facilitate better understanding of each other's viewpoint.

INFORMATION: EQUIPOISE

We have proposed the concept, of therapy by the ear, to help understand the causes of, and solutions to, the current lack of trust in the medical profession. The underlying etiology of mistrust, however, is lack of information. The solution to this is information equipoise.[7]

Physician and patient both possess differing sets of information. This information is influenced by their educational background and socioeconomic environment. Both parties formulate opinions and make decisions based on their preexisting knowledge. Mistrust and conflict arise when these opinions and decisions are discordant with each other. To ensure concordance of opinion, the first step is to create equality in information.

The perceived information gap between physician and patient is two-sided. If the physician feels that the patient is unaware of biomedical reality, the patient too complains that the physician does not take psychosocial or financial reality into consideration while planning therapy. Information equipoise allows the physician to take effective patient-centered decisions, in a manner, which is acceptable to the patient. Sharing of information between all stakeholders, in a transparent manner, ensures better understanding and leads to close teamwork. The onus for this lies with the physician rather than the patient. This in turn allows achievement of desired therapeutic outcomes.

INVOLVEMENT: ATREYA'S QUADRUPLE

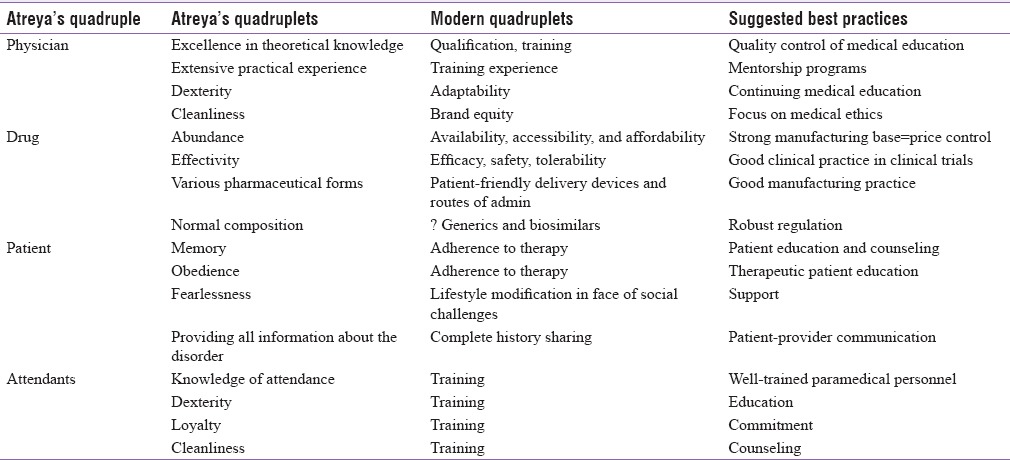

Apart from physician and patient, there are other players who contribute to health outcomes. This concept is nicely summarized in a centuries-old concept from traditional Indian medicine. Atreya, a founding father of Ayurveda, postulated four determinants of therapeutic outcomes and termed them the great quadruple. These are the physician, drug (therapeutic intervention), patient, and attendants (family members, nursing staff). For each of these, he listed four desirable properties using the terminology small quadruples (or Quadruplets).[8]

We propose revisiting Atreya's quadruple to understand the barriers to building trust between physician and patient. The physician-patient dyad does not exist in isolation. The community, health-care system, paramedical workers, and pharmaceutical industry also influence the quality of interaction between these two partners. The Atreyan rubric provides equal importance to these aspects of health care [Table 1].

Table 1.

The Atreyan rubric and modern medical practice

Recreating trust in the medical profession will not be possible if all stakeholders, both clinical and nonclinical, are not taken on board. Social marketing initiatives, as described earlier in this commentary, should be broadened to involve society at large. They should be able to explain the strengths, and limitations, of modern medical science, while emphasizing that doctors too are human and deserve a humane approach.

The health-care system, which includes policy makers, administrators, and insurers or payers, needs to contribute to this as well. Creation of a patient-friendly, patient-responsive, community-oriented, and community-based structure will mitigate many of the complaints voiced by patients today. The system should also be apprised of, and respectful of, the needs and requirement of health-care professionals, and work to fulfill their genuine requirements.

Senior teachers and physicians, who are part of the system in various capacities, have an important role to play in this regard. They should create a formal, ongoing, and sustained mechanism, by which to continually train younger colleagues in the values of good clinical sense and empathic communication. Paramedical and other health-care professionals, too, are an integral part of the health-care services. Using positive messaging, they can facilitate creation of trust between the community and patients, on the one hand, and the medical profession on the other hand. The basis of such trust is information.

Atreya's fourth angle is drugs. In modern parlance, we can take this to be the pharmaceutical industry in its entirety. Although it is true that a bad workman blames his tools, it is equally true the Indian medical fraternity works hard to provide good standard of care, in spite of being equipped with inadequate, inefficient, or inappropriate tools. The drug and device industry should work to provide quality products at affordable prices and ensure that they are available and accessible throughout the country.

Government policies on excise and taxation should be made industry- and consumer-friendly and budgetary provision for health should be increased. It is noteworthy that India is home to many complementary and alternative systems of medicine. Not all the drugs and formulations marketed by these systems are evidence based.[9] This is especially true for chronic diseases such as diabetes. Unfortunately, aggressive media marketing by some vested interests leads to confusion among health-care consumers and prevents proper utilization of modern medical care. Such miscommunication, too, needs to be curbed by the government so that trust can be rebuilt between doctors and patients they serve.

SUMMARY

The erosion of trust that has taken place with regard to the Indian medical profession is well known.[1] We encourage the medical fraternity, just as experts do,[1] to self-reflect on the current situation. We go a step further, by submitting three simple, yet pragmatic, tools which will help defuse the crisis and promote trust between all involved parties.

Practicing therapy by the ear and involving all stakeholders in Atreya's quadruple (promoting information equipoise with the population being served) is tools which should allay fears about the future of our profession. These tools can be brought together under a common umbrella, which we term the 3I strategy: interaction, information, and involvement. Integration of the 3I approach to daily practice will create mutual trust and respect with the people whom we serve.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kane S, Calnan M. Erosion of trust in the medical profession in India: Time for doctors to act. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;6:5–8. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalra S, Kumar A, Jarhyan P, Unnikrishnan AG. Endemic or epidemic? Measuring the endemicity index of diabetes. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:5–7. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.144633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalra S, Megallaa MH, Jawad F. Patient-centered care in diabetology: From eminence-based, to evidence-based, to end user-based medicine. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:871–2. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.102979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalra S, Megallaa MH, Jawad F. Perspectives on patient-centered care in diabetology. J Midlife Health. 2012;3:93–6. doi: 10.4103/0976-7800.104471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalra S, Baruah MP, Das AK. Diabetes therapy by the ear: A bi-directional process. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19(Suppl 1):S4–5. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.153416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verghese A. Cutting for Stone. Bronx, New York: Random House of Canada; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P, Grol R. Shared decision making and the concept of equipoise: The competences of involving patients in healthcare choices. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:892–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalra S, Kalra B, Agrawal N. Therapeutic patient education: Lessons from Ayurveda – The Quadruple of Atreya. Internet J Geriatr Gerontol. 2010;10:1. [Doi: 10.5580/25a] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kesavadev J, Saboo B, Sadikot S, Das AK, Joshi S, Chawla R, et al. Unproven Therapies for Diabetes and Their Implications. Adv Ther. 2017;34:60–77. doi: 10.1007/s12325-016-0439-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]