Abstract

Bone regeneration has been extensively studied over the past several decades. The surgically-induced mouse model is the key animal model for studying bone regeneration, of the various research strategies used. These mouse models mimic the trauma and recovery processes in vivo and serve as carriers for tissue engineering and gene modification to test various therapies or associated genes in bone regeneration. The present review introduces a classification of surgically induced mouse models in bone regeneration, evaluates the application and value of these models and discusses the potential development of further innovations in this field in the future.

Keywords: bone regeneration, animal model, surgical model, mouse

1. Introduction

Bone regeneration has been extensively investigated during the past several decades, resulting in therapeutic progression in this field. However, critical bone defects, particularly in patients with an unfavorable healing microenvironment, remain a primary concern for surgeons (1–3). Various mouse models have been developed for the investigation of various injuries and pathological processes associated with bone regeneration, and numerous important molecular signaling pathways have been elucidated and therapies developed (1,4–6). Among all the different mouse models, surgically-induced models are prevalent in bone regeneration research (7). Regenerative medical therapies associated with bone healing employ an extensive range of various strategies that aim to repair, augment, substitute or regenerate lost tissue (4). To determine the effect of these various treatment therapies, mouse models that use surgical induction of a particular condition are frequently performed, due to their similarity to the trauma and the patient recovery process (8–10). These models are well established in combination with tissue engineering strategies, for analysis of the function of growth factors, scaffolds and stem cells (11,12). Furthermore, these mouse models may be performed in genetically modified mice, which is an important method using gene-targeting to investigate the genes involved in bone regeneration (13,14). This review briefly evaluates surgically-induced mouse models, with focus on the most important models currently used and the potential development of novel models in the future.

2. Classification and applicability

The surgically induced mouse models were divided into three different groups based on the severity of trauma and the mouse phenotypes: Simple fracture models, bone defect models and ectopic bone formation models.

Simple fracture models

Simple fracture models are used to determine the effect of various drugs and gene modifications in fracture healing. The fracture model may be further classified by anatomic location, with the fibula (15,16) and femur (17,18) among the most common sites. The fracture may be created by blunt trauma or using ophthalmic forceps (15,16). For the simple blunt fracture model, three-point bending equipment is used to create a fracture. The simple fracture model in the femur is more complex, as it requires a needle to be implanted into the intramedullary cavity via the intercondylar notch to ‘fix’ the fracture prior to creation. This is not required in the fibular fracture model (19–21). These models are technically simple compared with other models and are frequently used for identification of bone regeneration associated factors (22,23).

Bone defect models

Critical sized bone defects are a challenging clinical scenario for surgeons and frequently result in a delayed bone union or a nonunion in numerous cases (24). Therefore, surgically-induced bone defect mouse models have been extensively used for analysis of growth factors (25,26). It has previously been reported that deficiency of progranulin (PGRN), which is a downstream mediator of bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) involved in bone healing, delayed bone healing, whereas recombinant PGRN enhanced bone regeneration. Furthermore, PGRN was required for BMP-2 induction of osteoblastogenesis and ectopic bone formation (25). When the bone defect models have been used in biomaterial research (27,28), the results indicated that osteoinduction and appropriate degradation were important in accelerating and promoting bone augmentation. This strategy appears promising as 3D temporal scaffolds for potential orthopedic applications (28). In addition, this type of model may be used in stem cell research (29–31). The findings of the experiment indicated that human muscle-derived stem cells (hMDSCs; Stem Cell Research Center, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) are mesenchymal stem cells of muscle origin and that BMP2 is more efficient than BMP4 in promoting the bone regenerative capacity of the hMDSCs in vivo (31). Local or systemic delivery of drugs may be tested using these models. Altering the genotype of the mouse involved with these models may also enable researchers to understand the molecular signaling pathways involved in fracture healing and bone regeneration. According to the size and pattern of the bone defect, these models are further divided into drill-hole or critical-size bone defect models.

Drill-hole models

Drill hole models are typically established in either the femur (32,33) or the tibia (34). To create a drill-hole, a drill is inserted into the bone while applying constant irrigation (32,34). These holes are typically created in the mid-shaft of the diaphysis of the long bone, where only cortical bone is involved. This model may be either unicortical or bicortical, in which the hole is created in either a single side or on both sides of cortical bone, respectively (25,35–37). Due to the small size of the hole, these models are predominantly used for testing the systemic delivery of medicine or to determine the effect of a specific gene modification on bone healing. These small bone defects have also been used for tissue engineering studies, in which collagen sponges are fixed in the hole position, despite the unstable location of implantation (34).

Critical-size bone defect models

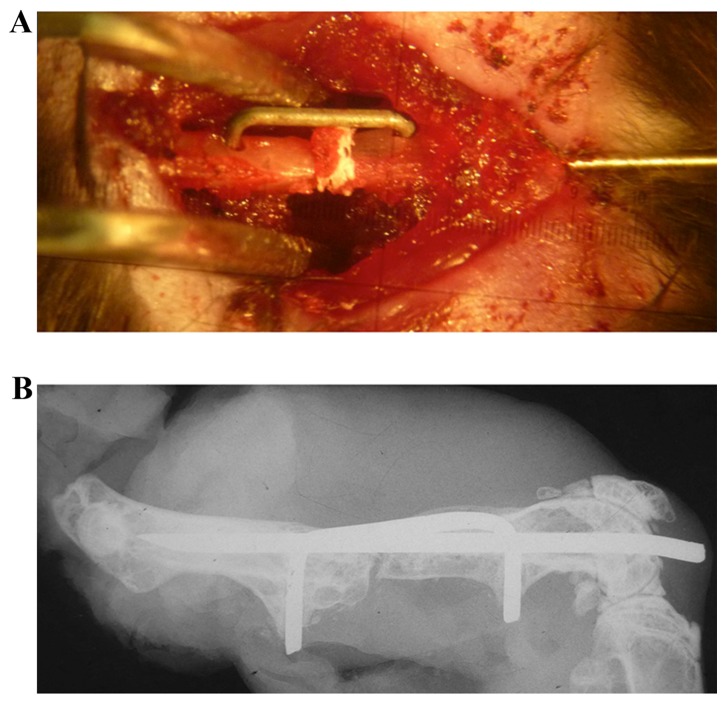

The critical bone defect model is used to simulate a greater degree of bone loss than the drill-hole model and is frequently used to study non-unions. A review of the literature revealed that two of the most frequently used methods to establish a critical bone defect include the use of either the cranial bone of the skull (38,39) or long bones of the extremities, including the femur (25,40,41) and radius. There are various differences in the methods used to establish these models. To create the cranial defect, the pericranium is removed and a trephine is used to create a circular bone defect in the skull, with meticulous care taken to avoid damaging the underlying dura mater (38,39). A drill bit is used to create the defect in the long bone defect models (25,41); however, a drill bit cannot be used to create cranial defects as the dura mater is in close proximity to the inferior aspect of the skull. In the mouse, a critical-size cranial defect is defined as a bone deficit ≥5 mm (42,43). This model has been used for the investigation of molecular signaling pathways associated with bone healing, by using knockout and overexpressing mice, and determining the effects of treatments aimed at the promotion of bone regeneration (44–46). For instance, critical-size bone defect models reveal accelerated bone formation and bone remodeling in the absence of the Toll-like receptor 4 signaling pathway. This phenotype is associated with alterations of local inflammatory cytokines and expression of osteoclastogenic factors (44). The femoral bone defect model was originally established to investigate the pathways involved in non-unions (40,47,48), and has since been used to study various treatments to promote bone healing (49). In our previous study, a 0.5 mm femoral bone defect was used to investigate bone healing. It was demonstrated that wild-type mice of the control group were able to fully heal the 0.5 mm bone defect, however PGRN knockout mice exhibited impaired bone healing (25). The mouse model was relatively complicated to create, as an intramedullary needle and a custom-made clip were implanted into the femur to fix the bone defect (Fig. 1). The use of metal devices may interfere with the bone signal when using micro computed tomography (CT; data not shown), and should be removed to minimize any of these artifacts (50). However, the removal process may result in damage to the original structure of the bone defect position.

Figure 1.

Establishing a femoral bone defect model. (A) Intramedullary needle and custom-made clip were implanted into the femur to fix the bone defect. (B) Post-operative X-ray analysis.

The radial bone defect model has been extensively used for determining the effects of tissue engineering in bone repair (51–53). This is a non-union model and the bone defect will not recover spontaneously without additional treatment, which enables the use of gain-of-function studies (54). The bone defect of the radius is stable, supported by an intact ulna and scaffold carrying growth factors, to aid the implantation of cells. Furthermore, this model has previously been established in genetically modified mice to study molecular signaling pathways of fracture healing. The present study established this model in tumor necrosis factor-α receptor (TNFR)-deficient mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) to investigate the role of TNFR in the effect of recombinant PGRN protein in the promotion of bone repair (25).

Ectopic bone formation model

Ectopic bone is bone that forms in locations where bone formation does not typically occur. Several molecules have been identified to be involved in the process of ectopic bone formation. It has previously been demonstrated that ectopic bone formation may occur in PGRN knockout mice (New York University Medical Center, New York, NY, USA) (78). BMPs are extensively used to induce ectopic bone formation (55,56). Molecules and signaling pathways associated with these growth factors are investigated using models of ectopic bone formation (35,57). These models are typically either subcutaneous or intramuscular in location (25,56,58). For subcutaneous ectopic bone formation models, implants carrying genetically modified stem cells and/or growth factors are surgically implanted into a pocket beneath the skin, and bone formation is detected at indicated time points (59). Intramuscular ectopic bone formation can be established in paravertebral (51,60,61), thigh (62) or calf muscles (63). These models may be used to determine the effect of various therapies on BMP-induced bone formation, and may aid the identification of novel therapeutic strategies (25,59,64). The data from this type of model demonstrates that a focused approach to develop targeted differentiation protocols in adult progenitor cells may be achieved via the identification and subsequent stimulation of genes, proteins and signaling pathways associated with calcium phosphate mediated osteoinduction (64).

3. Advantages and limitations

Mouse models have numerous advantages compared with larger animal models, and are used for a broad range of applications (Table I) (65). Mice are docile, tolerate the surgical procedures and are able to ambulate with the implanted limb within a short time following surgery (66). Additionally, genetic alterations are easily created in mice and therefore certain genes can be targeted for knockout or overexpression. This allows the investigation of the effect of drug therapies on bone regeneration and the identification of the underlying molecular mechanisms involved. Furthermore, various mouse models have been well established in the literature, and researchers may select an appropriate model based on the aim of the experiment.

Table I.

Comparative list of various models and associated information.

| First author, year | Model | Main classification | Implement | Application | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheng, 2010; Kayal, 2010; Holstein, 2010; Holstein, 2009; O'Neill, 2012; Einhorn, 1995; Kellum, 2009; Wigner, 2012 Gerstenfield, 2003 | Simple fracture models | Fibular fracture models, femoral fracture models | Blunt trauma, ophthalmic forceps | Identify the bone regeneration associated factors | (15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23) |

| Haddock, 2013; Zhao, 2013; Ben-David, 2013; Annibali, 2013; Yang, 2013; Zhang, 2013; Fricain, 2013; Gao, 2013; Tanaka, 2010; Katae, 2009; Behr, 2010; Tang, 2009; He, 2011; Jawad, 2013; Meszaros, 2012; Behr, 2012; Liu, 2013; Manassero, 2013; Krebsbach, 1998; Lee, 2001; Wang, 2012; Levi, 2012; Lo, 2012; Garcia, 208; Zwingenburger, 2013; Lin, 2012; Holstein, 2011; Kimelman-Bleich, 2009; Moutsatsos, 2001; Kimelmen-Bleich, 2011; Tai, 2008 | Bone defect models | Drill-hole models, critical-size bone defect models | Drill, trephine | Analyze the growth factors, biomaterials and stem cells | (24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41 42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54) |

| Zhao, 2013; Tang, 2009; Bergeron, 2012; Kamiya, 2012; Chen, 2010; Wagner-Ecker, 2013; Frescaline, 2013; Sheyn, 2008; Medica, 2010; Shimaro, 2011; Eckmans, 2013; Zhao, 2015 | Ectopic bone, formation models | Subcutaneous bone formation models, intramuscular bone formation models | BMPs molecules | Identify molecules and signaling pathways associated with growth factors | (25,35,55,56,57,58,59,61,62,63,64,78) |

However, surgically-induced mouse models have limitations. In numerous cases, genetic modification results in a defect during development, which may involve bone growth (67,68). This may subsequently interfere with bone healing, and therefore artificially alter the results of the experiment. In these cases, inducible genetically modified mice may be used to eliminate any effect on bone development (69).

4. Discussion, conclusion and perspective

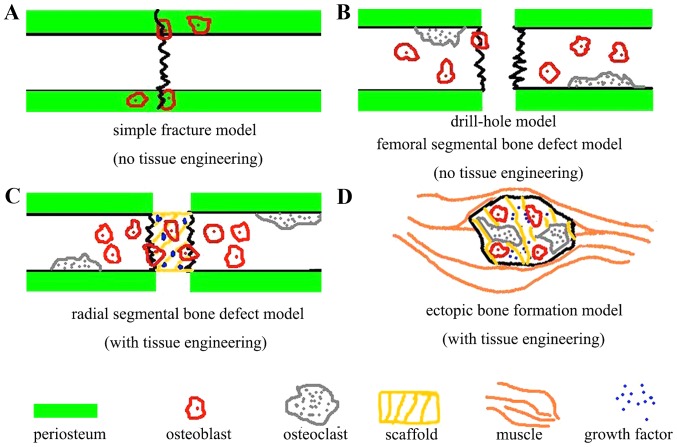

The mouse is currently the most commonly used animal model in basic research (Table I) (70). The ease of maintenance, relative low cost and abundance of pre-established mouse models provide advantages compared with other species (65). The ability to use mouse models in an effective manner in order to gather valuable scientific information is the responsibility of the researcher. Researchers should select appropriate models according to the aim of their project. Fig. 2 presents a proposed outline for the various regenerative modalities of fracture healing in surgically induced mouse models. Various cells, particularly osteoblasts (71,72) and osteoclasts (73), participate in the bone regeneration process, and induce bone formation and remodeling. In simple bone regeneration models, periosteum and intramembranous ossification is important in the regeneration process (74,75). In the bone defect model, the indicated cells accumulate towards the location of the bone defect. The use of scaffolds (76) and exogenous growth factors (77) may further promote the targeted accumulation and function of endogenous and implanted cells. The surgically-induced mouse model is the environment in which all of these interactions occur. Further studies are required to determine the potential long-term effects of such treatments on bone repair using various fracture models (73). Numerous discoveries using mouse model of bone regeneration have already been clinically tested and translated into clinical applications. For instance, BMP-2 and −7 were initially investigated using a surgically-induced mouse model of bone regeneration and are now available for clinical use to promote bone regeneration and healing (77).

Figure 2.

Proposed outline for the different regenerative modalities of fracture healing in various surgically-induced mouse models. (A) Simple fracture model. (B) Drill hole model. (C) Radial segmental bone defect model. (D) Ectopic bone formation model. Various cells, particularly osteoblasts and osteoclasts, participate in the bone regeneration process and induce bone formation and remodeling. In simple bone regeneration models, periosteum and intramembranous ossification are important in the regeneration process. In the bone defect model, the indicated cells accumulate towards the location of the bone defect. The use of scaffolds and exogenous growth factors may further promote the targeted accumulation and function of endogenous and implanted cells.

The use of surgically-induced mouse models of bone regeneration have the potential to be improved. Firstly, more efficient devices may be developed for fixation of these models. Fixation devices that are used near the surgical site should be free of degrading particles to result in a more purified microenvironment for bone regeneration. Novel devices are required for more convenient fixation and less damage to the surrounding soft tissue, so that the blood supply to the area of healing is protected. Imaging modalities used for these small areas of bone regeneration also require improvement, including micro CT and magnetic resonance imaging. Finally, inducible transgenic mice should be used more frequently in the establishment of these models, as this would eliminate any alterations in bone formation that occur during development.

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81401014), the Star of Jinan Youth Science and Technology Project (grant no. 20100114), the Young Scientists Awards Foundation of Shandong Province (grant no. BS2013YY049) and the International Cooperation Projects of Jinan City (grant no. 201305053).

References

- 1.Gomes PS, Fernandes MH. Rodent models in bone-related research: The relevance of calvarial defects in the assessment of bone regeneration strategies. Lab Anim. 2011;45:14–24. doi: 10.1258/la.2010.010085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hobby B, Lee MA. Managing atrophic nonunion in the geriatric population: Incidence, distribution and causes. Orthop Clin North Am. 2013;44:251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards BJ, Bunta AD, Lane J, Odvina C, Rao DS, Raisch DW, McKoy JM, Omar I, Belknap SM, Garg V, et al. Bisphosphonates and nonhealing femoral fractures: Analysis of the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) and international safety efforts: A systematic review from the research on adverse drug events and reports (RADAR) project. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:297–307. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleinschmidt K, Ploeger F, Nickel J, Glockenmeier J, Kunz P, Richter W. Enhanced reconstruction of long bone architecture by a growth factor mutant combining positive features of GDF-5 and BMP-2. Biomaterials. 2013;34:5926–5936. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang X, Zara J, Siu RK, Ting K, Soo C. The role of NELL-1, a growth factor associated with craniosynostosis, in promoting bone regeneration. J Dent Res. 2010;89:865–878. doi: 10.1177/0022034510376401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao YP, Tian QY, Liu CJ. Progranulin deficiency exaggerates, whereas progranulin-derived Atsttrin attenuates, severity of dermatitis in mice. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:1805–1810. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szpalski C, Barr J, Wetterau M, Saadeh PB, Warren SM. Cranial bone defects: Current and future strategies. Neurosurgical Focus. 2010;29:E8. doi: 10.3171/2010.9.FOCUS10201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wahl EC, Aronson J, Liu L, Skinner RA, Ronis MJ, Lumpkin CK., Jr Distraction osteogenesis in TNF receptor 1 deficient mice is protected from chronic ethanol exposure. Alcohol. 2012;46:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang X, Péault B, Chen W, Li W, Corselli M, James AW, Lee M, Siu RK, Shen P, Zheng Z, et al. The Nell-1 growth factor stimulates bone formation by purified human perivascular cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:2497–2509. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mashiba T, Iwata K, Komatsubara S, Manabe T. Animal models for bone and joint disease. Animal fracture model and fracture healing process. Clin calcium. 2011;21:235–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burg KJ, Porter S, Kellam JF. Biomaterial developments for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2000;21:2347–2359. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(00)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giannoudis PV, Pountos I. Tissue regeneration. The past, the present and the future. Injury. 2005;36:S2–S5. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2005.10.006. (Suppl 4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maes C, Carmeliet G, Schipani E. Hypoxia-driven pathways in bone development, regeneration and disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:358–366. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosen V. BMP2 signaling in bone development and repair. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng L, Ye F, Yang R, Lu X, Shi Y, Li L, Fan H, Bu H. Osteoinduction of hydroxyapatite/beta-tricalcium phosphate bioceramics in mice with a fractured fibula. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:1569–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kayal RA, Siqueira M, Alblowi J, McLean J, Krothapalli N, Faibish D, Einhorn TA, Gerstenfeld LC, Graves DT. TNF-alpha mediates diabetes-enhanced chondrocyte apoptosis during fracture healing and stimulates chondrocyte apoptosis through FOXO1. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:1604–1615. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holstein JH, Karabin-Kehl B, Scheuer C, Garcia P, Histing T, Meier C, Benninger E, Menger MD, Pohlemann T. Endostatin inhibits Callus remodeling during fracture healing in mice. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:1579–1584. doi: 10.1002/jor.22401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holstein JH, Matthys R, Histing T, Becker SC, Fiedler M, Garcia P, Meier C, Pohlemann T, Menger MD. Development of a stable closed femoral fracture model in mice. J Surg Res. 2009;153:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Neill KR, Stutz CM, Mignemi NA, Burns MC, Murry MR, Nyman JS, Schoenecker JG. Micro-computed tomography assessment of the progression of fracture healing in mice. Bone. 2012;50:1357–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Einhorn TA. Enhancement of fracture-healing. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:940–956. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199506000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kellum E, Starr H, Arounleut P, Immel D, Fulzele S, Wenger K, Hamrick MW. Myostatin (GDF-8) deficiency increases fracture callus size, Sox-5 expression, and callus bone volume. Bone. 2009;44:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.08.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wigner NA, Kulkarni N, Yakavonis M, Young M, Tinsley B, Meeks B, Einhorn TA, Gerstenfeld LC. Urine matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) as biomarkers for the progression of fracture healing. Injury. 2012;43:274–278. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerstenfeld LC, Cho TJ, Kon T, Aizawa T, Tsay A, Fitch J, Barnes GL, Graves DT, Einhorn TA. Impaired fracture healing in the absence of TNF-alpha signaling: The role of TNF-alpha in endochondral cartilage resorption. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1584–1592. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.9.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haddock NT, Wapner K, Levin LS. Vascular bone transfer options in the foot and ankle: A retrospective review and update on strategies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:685–693. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31829acedd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao YP, Tian QY, Frenkel S, Liu CJ. The promotion of bone healing by progranulin, a downstream molecule of BMP-2, through interacting with TNF/TNFR signaling. Biomaterials. 2013;34:6412–6421. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ben-David D, Srouji S, Shapira-Schweitzer K, Kossover O, Ivanir E, Kuhn G, Müller R, Seliktar D, Livne E. Low dose BMP-2 treatment for bone repair using a PEGylated fibrinogen hydrogel matrix. Biomaterials. 2013;34:2902–2910. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Annibali S, Cicconetti A, Cristalli MP, Giordano G, Trisi P, Pilloni A, Ottolenghi L. A comparative morphometric analysis of biodegradable scaffolds as carriers for dental pulp and periosteal stem cells in a model of bone regeneration. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:866–871. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31827ca530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang F, Wang J, Hou J, Guo H, Liu C. Bone regeneration using cell-mediated responsive degradable PEG-based scaffolds incorporating with rhBMP-2. Biomaterials. 2013;34:1514–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, Xing L. Ubiquitin e3 ligase itch negatively regulates osteoblast differentiation from mesenchymal progenitor cells. Stem cells. 2013;31:1574–1583. doi: 10.1002/stem.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fricain JC, Schlaubitz S, Le Visage C, Arnault I, Derkaoui SM, Siadous R, Catros S, Lalande C, Bareille R, Renard M, et al. A nano-hydroxyapatite-pullulan/dextran polysaccharide composite macroporous material for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2013;34:2947–2959. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao X, Usas A, Lu A, Tang Y, Wang B, Chen CW, Li H, Tebbets JC, Cummins JH, Huard J. BMP2 is superior to BMP4 for promoting human muscle-derived stem cell-mediated bone regeneration in a critical-sized calvarial defect model. Cell transplantat. 2013;22:2393–2408. doi: 10.3727/096368912X658854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka K, Tanaka S, Sakai A, Ninomiya T, Arai Y, Nakamura T. Deficiency of vitamin A delays bone healing process in association with reduced BMP2 expression after drill-hole injury in mice. Bone. 2010;47:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katae Y, Tanaka S, Sakai A, Nagashima M, Hirasawa H, Nakamura T. Elcatonin injections suppress systemic bone resorption without affecting cortical bone regeneration after drill-hole injuries in mice. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:1652–1658. doi: 10.1002/jor.20920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Behr B, Leucht P, Longaker MT, Quarto N. Fgf-9 is required for angiogenesis and osteogenesis in long bone repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11853–11858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003317107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang N, Song WX, Luo J, Luo X, Chen J, Sharff KA, Bi Y, He BC, Huang JY, Zhu GH, et al. BMP-9-induced osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal progenitors requires functional canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:2448–2464. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00569.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He YX, Zhang G, Pan XH, Liu Z, Zheng LZ, Chan CW, Lee KM, Cao YP, Li G, Wei L, et al. Impaired bone healing pattern in mice with ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis: A drill-hole defect model. Bone. 2011;48:1388–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.03.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jawad MU, Fritton KE, Ma T, Ren PG, Goodman SB, Ke HZ, Babij P, Genovese MC. Effects of sclerostin antibody on healing of a non-critical size femoral bone defect. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:155–163. doi: 10.1002/jor.22186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meszaros LB, Usas A, Cooper GM, Huard J. Effect of host sex and sex hormones on muscle-derived stem cell-mediated bone formation and defect healing. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:1751–1759. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Behr B, Sorkin M, Lehnhardt M, Renda A, Longaker MT, Quarto N. A comparative analysis of the osteogenic effects of BMP-2, FGF-2, and VEGFA in a calvarial defect model. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:1079–1086. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu K, Li D, Huang X, Lv K, Ongodia D, Zhu L, Zhou L, Li Z. A murine femoral segmental defect model for bone tissue engineering using a novel rigid internal fixation system. J Surg Res. 2013;183:493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manassero M, Viateau V, Matthys R, Deschepper M, Vallefuoco R, Bensidhoum M, Petite H. A novel murine femoral segmental critical-sized defect model stabilized by plate osteosynthesis for bone tissue engineering purposes. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2013;19:271–280. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2012.0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krebsbach PH, Mankani MH, Satomura K, Kuznetsov SA, Robey PG. Repair of craniotomy defects using bone marrow stromal cells. Transplantation. 1998;66:1272–1278. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199811270-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee JY, Musgrave D, Pelinkovic D, Fukushima K, Cummins J, Usas A, Robbins P, Fu FH, Huard J. Effect of bone morphogenetic protein-2-expressing muscle-derived cells on healing of critical-sized bone defects in mice. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A:1032–1039. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200107000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang D, Gilbert JR, Cray JJ, Jr, Kubala AA, Shaw MA, Billiar TR, Cooper GM. Accelerated calvarial healing in mice lacking Toll-like receptor 4. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levi B, Hyun JS, Montoro DT, Lo DD, Chan CK, Hu S, Sun N, Lee M, Grova M, Connolly AJ, et al. In vivo directed differentiation of pluripotent stem cells for skeletal regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:20379–20384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218052109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lo DD, Mackanos MA, Chung MT, Hyun JS, Montoro DT, Grova M, Liu C, Wang J, Palanker D, Connolly AJ, et al. Femtosecond plasma mediated laser ablation has advantages over mechanical osteotomy of cranial bone. Lasers Surg Med. 2012;44:805–814. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garcia P, Holstein JH, Maier S, Schaumlöffel H, Al-Marrawi F, Hannig M, Pohlemann T, Menger MD. Development of a reliable non-union model in mice. J Surg Res. 2008;147:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zwingenberger S, Niederlohmann E, Vater C, Rammelt S, Matthys R, Bernhardt R, Valladares RD, Goodman SB, Stiehler M. Establishment of a femoral critical-size bone defect model in immunodeficient mice. J Surg Res. 2013;181:e7–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin EA, Liu CJ, Monroy A, Khurana S, Egol KA. Prevention of atrophic nonunion by the systemic administration of parathyroid hormone (PTH 1–34) in an experimental animal model. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26:719–723. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31826f5b9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holstein JH, Orth M, Scheuer C, Tami A, Becker SC, Garcia P, Histing T, Mörsdorf P, Klein M, Pohlemann T, Menger MD. Erythropoietin stimulates bone formation, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis in a femoral segmental defect model in mice. Bone. 2011;49:1037–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kimelman-Bleich N, Pelled G, Sheyn D, Kallai I, Zilberman Y, Mizrahi O, Tal Y, Tawackoli W, Gazit Z, Gazit D. The use of a synthetic oxygen carrier-enriched hydrogel to enhance mesenchymal stem cell-based bone formation in vivo. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4639–4648. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moutsatsos IK, Turgeman G, Zhou S, Kurkalli BG, Pelled G, Tzur L, Kelley P, Stumm N, Mi S, Müller R, et al. Exogenously regulated stem cell-mediated gene therapy for bone regeneration. Mol Ther. 2001;3:449–461. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kimelman-Bleich N, Pelled G, Zilberman Y, Kallai I, Mizrahi O, Tawackoli W, Gazit Z, Gazit D. Targeted gene-and-host progenitor cell therapy for nonunion bone fracture repair. Mol Ther. 2011;19:53–59. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tai K, Pelled G, Sheyn D, Bershteyn A, Han L, Kallai I, Zilberman Y, Ortiz C, Gazit D. Nanobiomechanics of repair bone regenerated by genetically modified mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:1709–1720. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bergeron E, Leblanc E, Drevelle O, Giguère R, Beauvais S, Grenier G, Faucheux N. The evaluation of ectopic bone formation induced by delivery systems for bone morphogenetic protein-9 or its derived peptide. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:342–352. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kamiya N. The role of BMPs in bone anabolism and their potential targets SOST and DKK1. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2012;5:153–163. doi: 10.2174/1874467211205020153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen L, Jiang W, Huang J, He BC, Zuo GW, Zhang W, Luo Q, Shi Q, Zhang BQ, Wagner ER. Insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF-2) potentiates BMP-9-induced osteogenic differentiation and bone formation. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2447–2459. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wagner-Ecker M, Voltz P, Egermann M, Richter W. The collagen component of biological bone graft substitutes promotes ectopic bone formation by human mesenchymal stem cells. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:7298–7307. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frescaline G, Bouderlique T, Mansoor L, Carpentier G, Baroukh B, Sineriz F, Trouillas M, Saffar JL, Courty J, Lataillade JJ, et al. Glycosaminoglycan mimetic associated to human mesenchymal stem cell-based scaffolds inhibit ectopic bone formation, but induce angiogenesis in vivo. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19:1641–1653. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hasharoni A, Zilberman Y, Turgeman G, Helm GA, Liebergall M, Gazit D. Murine spinal fusion induced by engineered mesenchymal stem cells that conditionally express bone morphogenetic protein-2. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3:47–52. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.3.1.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sheyn D, Pelled G, Zilberman Y, Talasazan F, Frank JM, Gazit D, Gazit Z. Nonvirally engineered porcine adipose tissue-derived stem cells: Use in posterior spinal fusion. Stem cells. 2008;26:1056–1064. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Medici D, Shore EM, Lounev VY, Kaplan FS, Kalluri R, Olsen BR. Conversion of vascular endothelial cells into multipotent stem-like cells. Nat Med. 2010;16:1400–1406. doi: 10.1038/nm.2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shimono K, Tung WE, Macolino C, Chi AH, Didizian JH, Mundy C, Chandraratna RA, Mishina Y, Enomoto-Iwamoto M, Pacifici M, Iwamoto M. Potent inhibition of heterotopic ossification by nuclear retinoic acid receptor-γ agonists. Nat Med. 2011;17:454–460. doi: 10.1038/nm.2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eyckmans J, Roberts SJ, Bolander J, Schrooten J, Chen CS, Luyten FP. Mapping calcium phosphate activated gene networks as a strategy for targeted osteoinduction of human progenitors. Biomaterials. 2013;34:4612–4621. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aalami OO, Nacamuli RP, Lenton KA, Cowan CM, Fang TD, Fong KD, Shi YY, Song HM, Sahar DE, Longaker MT. Applications of a mouse model of calvarial healing: Differences in regenerative abilities of juveniles and adults. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:713–720. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000131016.12754.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang T, Yu H, Gong W, Zhang L, Jia T, Wooley PH, Yang SY. The effect of osteoprotegerin gene modification on wear debris-induced osteolysis in a murine model of knee prosthesis failure. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6102–6108. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baron R, Kneissel M. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: From human mutations to treatments. Nat Med. 2013;19:179–192. doi: 10.1038/nm.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Seto J, Busse B, Gupta HS, Schäfer C, Krauss S, Dunlop JW, Masic A, Kerschnitzki M, Zaslansky P, Boesecke P, et al. Accelerated growth plate mineralization and foreshortened proximal limb bones in fetuin-A knockout mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xie C, Xue M, Wang Q, Schwarz EM, O'Keefe RJ, Zhang X. Tamoxifen-inducible CreER-mediated gene targeting in periosteum via bone-graft transplantation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:S9–S13. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01212. (Suppl 1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bockamp E, Maringer M, Spangenberg C, Fees S, Fraser S, Eshkind L, Oesch F, Zabel B. Of mice and models: Improved animal models for biomedical research. Physiol Genomics. 2002;11:115–132. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00067.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Matsushita Y, Sakamoto K, Tamamura Y, Shibata Y, Minamizato T, Kihara T, Ito M, Katsube K, Hiraoka S, Koseki H, et al. CCN3 protein participates in bone regeneration as an inhibitory factor. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:19973–19985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.454652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gualeni B, de Vernejoul MC, Marty-Morieux C, De Leonardis F, Franchi M, Monti L, Forlino A, Houillier P, Rossi A, Geoffroy V. Alteration of proteoglycan sulfation affects bone growth and remodeling. Bone. 2013;54:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.do Soung Y, Gentile MA, le Duong T, Drissi H. Effects of pharmacological inhibition of cathepsin K on fracture repair in mice. Bone. 2013;55:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Colnot C, Zhang X, Tate Knothe ML. Current insights on the regenerative potential of the periosteum: Molecular, cellular, and endogenous engineering approaches. J Orthop Res. 2012;30:1869–1878. doi: 10.1002/jor.22181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yu YY, Bahney C, Hu D, Marcucio RS, Miclau T., III Creating rigidly stabilized fractures for assessing intramembranous ossification, distraction osteogenesis, or healing of critical sized defects. J Vis Exp pii. 2012:3552. doi: 10.3791/3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bose S, Roy M, Bandyopadhyay A. Recent advances in bone tissue engineering scaffolds. Trends Biotechnol. 2012;30:546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yun YR, Jang JH, Jeon E, Kang W, Lee S, Won JE, Kim HW, Wall I. Administration of growth factors for bone regeneration. Regen Med. 2012;7:369–385. doi: 10.2217/rme.12.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhao YP, Tian QY, Liu B, Cuellar J, Richbourgh B, Jia TH, Liu CJ. Progranulin knockout accelerates intervertebral disc degeneration in aging mice. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9102. doi: 10.1038/srep09102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]