Abstract

Tendoscopy is an apparently safe and reliable procedure to manage some foot and ankle disorders.

The most common foot and ankle tendoscopies are: Achilles; peroneal; and posterior tibial tendon.

Tendoscopy may be used as an adjacent procedure to other techniques.

Caution is recommended to avoid neurovascular injuries.

Predominantly level IV and V studies are found in the literature, with no level I studies still available.

There are many promising and evolving endoscopic techniques for tendinopathies around the foot and ankle, but studies of higher levels of evidence are needed to strongly recommend these procedures.

Cite this article: EFORT Open Rev 2016;1:440-447. DOI: 10.1302/2058-5241.160028

Keywords: tendoscopy, endoscopy, Achilles, peroneal tendons, posterior tibial tendon, tendinopathy

Introduction

Advances in arthroscopic techniques and equipment have allowed orthopaedic surgeons to develop endoscopic procedures to visualise and treat different pathological conditions of several tendons around the foot and ankle.

Arthroscopy is now a well established procedure for foot and ankle disorders, but the relatively novel tendoscopic technique was first published by Wertheimer in 1995.1 In 1997, van Dijk, Sholten and Kort published a paper on endoscopy of the peroneal, anterior tibial and Achilles tendon sheaths, and named the technique ‘tendoscopy’.2 Tendoscopy is usually followed by a functional post-operative treatment and has the advantages of less post-operative pain, fewer complications and being performed as day surgery.

Endoscopic approaches have been described for almost all tendons around the foot and ankle. However, we will review the most common tendoscopies in our practice namely Achilles, peroneal tendons and posterior tibial tendon (PTT). We will not cover flexor hallucis longus tendon endoscopy in the present review because of its access via posterior ankle arthroscopy.

In the current literature, there is poor evidence for most of the common indications of foot and ankle tendoscopies. However, being a relatively safe and effective procedure in isolation or combined with other surgical techniques, orthopaedic surgeons have incorporated tendoscopies into foot and ankle practice. We review the existing evidence on the topic and an overview of indications, surgical techniques, results, complications, and the present and future of foot and ankle tendoscopies.

Achilles tendoscopy

Non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy and peritendinopathy are the most frequent indications for Achilles tendoscopy. The origin of pain in non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy has not yet been clarified. Neovascularisation and neoinnervation from surrounding tissues are actually the more accepted theories about the aetiology of pain.3 Achilles tendoscopy seems to be an adequate technique to allow for adhesion release and the destruction of neovessels and neonerves while preserving skin integrity. A probe or a shaver may be used to obtain adhesiolysis in chronic Achilles tendinopathy. Most indications for open surgery of the Achilles tendon are now theoretically covered by tendoscopy with lower morbidity and, in particular, fewer wound problems.

Tendoscopy may also play a role in assisting the repair of acute Achilles tendon ruptures. Other indications for Achilles tendoscopy include retrocalcaneal bursitis (endoscopic calcaneoplasty), plantaris tendon augmentation and flexor hallucis augmentation in chronic neglected ruptures.

Surgical technique

The operative technique for Achilles tendoscopy was developed by van Dijk et al.2 The patient is placed prone with a tourniquet on the thigh, and the foot out of the operating table to allow the surgeon to dorsiflex and plantarflex the ankle joint. Portals are made using a size 11 scalpel. The distal portal is made on the lateral border of the tendon, around 3-4 cm distal to the thickening of the Achilles in insertional tendinopathy. The proximal portal is made on the medial border of the tendon, around 3-4 cm proximal to the thickening to allow for around 15 cm of length to visualise and work along the tendon (Fig. 1). The distal lateral portal is placed first. A blunt trocar is first used through the distal portal and a 2.7 mm or 4.0 mm scope is used to release adhesions in the paratenon space by repeatedly passing it around the Achilles. This manoeuvre, together with plantarflexion of the ankle joint, allows for the easier introduction of a 30° 2.7 mm or 4.0 mm scope through the lateral distal portal and the probe and shaver through the proximal portal. Once the scope is introduced through the distal portal, gravity inflow is used to insufflate the paratenon. Under direct visualisation, a spinal needle is placed to locate the second portal placement. A probe is introduced through the proximal medial portal to release any remaining fibrotic tissue binding the tendon (Fig. 2). A shaver system is introduced through the proximal portal to debride hypertrophic fibrosis (Fig. 3). If present, plantaris tendon is released from the Achilles. Small tendon nodules may be debrided if present. Portals are closed with absorbable sutures and a compression bandage is left for 24 hours and afterwards changed for an adhesive bandage.

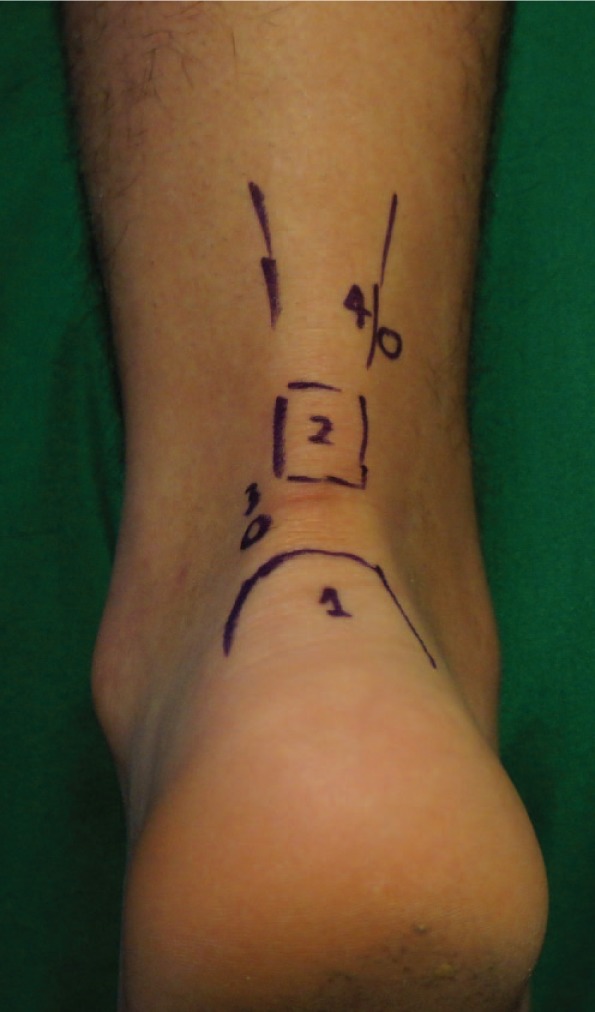

Fig. 1.

Portal placement for Achilles tendoscopy: 1) calcaneal tuberosity; 2) Achilles thickening; 3) distal lateral portal; 4) proximal medial portal.

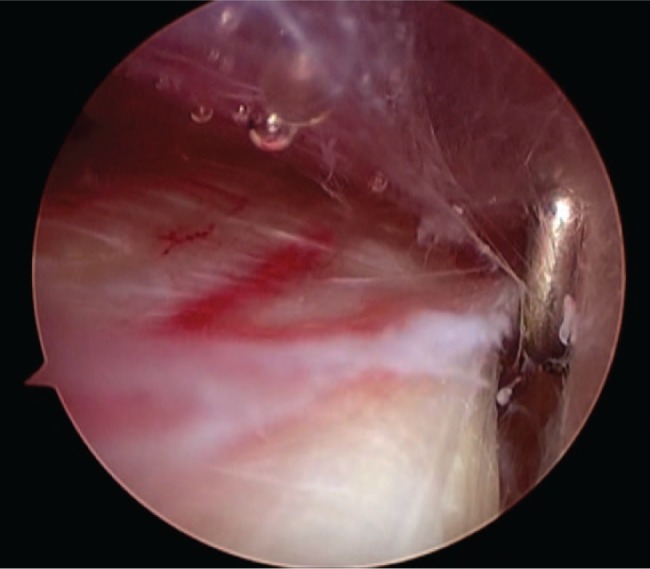

Fig. 2.

Achilles tendoscopy for non-insertional tendinopathy. A probe is used to release adhesions around the tendon.

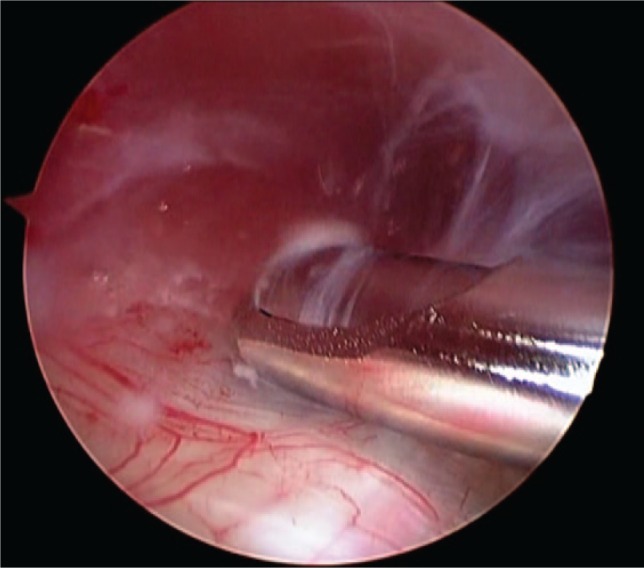

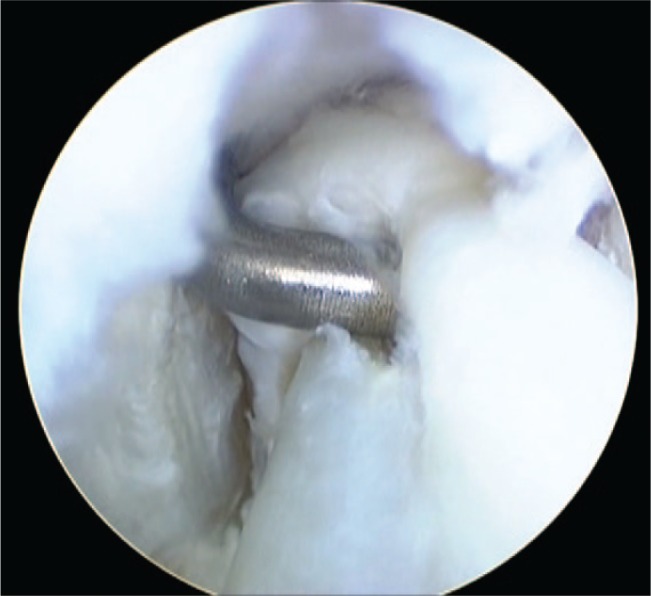

Fig. 3.

Achilles tendoscopy showing adhesiolysis with a shaver. Neovascularisation around the tendon may be observed.

The patient is allowed to bear weight, as tolerated, with the use of crutches and active range-of-motion exercises are encouraged from the first post-operative week. Eccentric exercises are introduced at around the third post-operative week. Return to non-impact sports is encouraged at three weeks and return-to-play for impact sports is resumed at six to eight weeks after surgery.

For Achilles tendon ruptures, tendoscopy has been advocated by some authors to provide a better assessment of tendon end approximation.4 In the scenario of the six stab incisions for a mini-invasive repair, the scope may be introduced through the central medial portal (over the tendon gap) to corroborate tendon end apposition.

Results

Maquirriain presented the long-term results of Achilles tendoscopy for chronic non-insertional tendinopathy.5 Mean follow-up was 7.7 years (5 to 14). In total, 24 patients (27 procedures) underwent paratenon debridement and longitudinal tenotomies resulting in 96% of patients free of symptoms.

Pearce et al evaluated the results of Achilles tendoscopy for non-insertional tendinopathy with division of the plantaris tendon.6 Almost 73% of their 11 patients were satisfied with the final outcome.

Some other level IV studies (retrospective case series) reported good to excellent results when dealing with endoscopy of the Achilles tendon for non-insertional tendinopathy and acute and chronic ruptures.7-10 Lui described the treatment of chronic non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy with endoscopic Achilles debridement and flexor hallucis longus transfer.11 Gossage et al reported the endoscopic assistance for the augmentation of a chronic Achilles tendon rupture with flexor hallucis longus tendon.12

Halasi et al prospectively studied the results of percutaneous acute Achilles rupture repair with and without tendoscopic assistance.4 In this level II study (the only level II study in foot and ankle tendoscopy to date), endoscopy was intended to control apposition of the tendon ends. Although not statistically significant, the authors noted that they were able to get a more precise repair with the aid of tendoscopy.

Peroneal tendoscopy

Indications for peroneal tendoscopy include retrofibular pain, tenosynovitis, subluxation or dislocation, intrasheath subluxation, partial tears, impingement of peroneus longus at the peroneal tubercule, post-operative adhesions and scarring, and resection of a peroneus quartus tendon or a bifid peroneus brevis or a low-lying peroneal muscle belly. Some indications for open surgery of the peroneal tendons are now covered by tendoscopy, except for the repair of extensive longitudinal tears.

Surgical technique

The operative technique for Achilles tendoscopy was first described by van Dijk.13 The patient may be placed in a lateral, anterior or prone position depending on the potential concomitant procedures planned beforehand. When peroneal tendoscopy is performed as an isolated procedure, the lateral position is preferred. A thigh tourniquet is applied and gravity inflow is used to insufflate the paratenon. Portals are made using a size 11 scalpel.

The distal portal is made first, around 2 cm distal to the malleolar tip. The proximal portal is placed around 3 cm proximal to the lateral malleolus tip, along the course of the peroneal tendons. Portals may be changed depending on the location of the disorder (Fig. 4). The working space is limited by the fibrous tendon sheath, and rotation of the scope is needed to reach the whole span of the tendon sheath. The distal portal is placed first. A 1 cm skin incision is made over the peroneals, following the longitudinal axis of the tendons. Subcutaneous dissection is made to expose tendon sheath. The sheath is opened with a 1 cm incision perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the tendon. This crossed disposition between the skin and the tendon sheath incisions is useful to prevent unintentionally enlarging the entry to the tendon when moving the scope during surgery. A blunt trocar is first used to release adhesions and create space for the scope. A 30° 2.7 mm or 4.0 mm scope is first gently introduced through the distal portal. Under direct visualisation, a spinal needle is placed to locate the proximal portal placement. Special care should be taken to orientate the needle and the scalpel obliquely so as not to penetrate and damage the tendons. A probe is introduced through the proximal portal to release any remaining fibrotic tissue around the tendons. Inspection includes ruling out a peroneus quartus tendon, intrasheath subluxation and longitudinal tears. A shaver system is introduced through the proximal portal to debride hypertrophic synovium and fibrosis. The limited working space for peroneal tendoscopy and the limited degree of side-to-side motion makes continuous rotation of instruments necessary to access peroneal tendons (Fig. 5). Small tendon nodules may be debrided if present. A burr may be used through the proximal portal for the deepening of the malleolar groove in cases of peroneal dislocation. Some peripheral tears may be debrided via a tendoscopic approach. Portals are closed with absorbable sutures and a compression bandage is left for 24 hours and then changed for an adhesive bandage.

Fig. 4.

Portal placement for peroneal tendoscopy: 1) fifth metatarsal; 2) lateral malleolus; 3) distal portal; 4) proximal portal.

Fig. 5.

Peroneal tendoscopy with visualisation of peroneus brevis tendon, peroneus longus tendon and vinculum.

As an isolated procedure for synovitis, the patient is allowed to bear weight as tolerated with the use of crutches. Active range-of-motion exercises are recommended from the first post-operative week. Return to non-impact sports is encouraged at three weeks and return-to-play for impact sports is resumed at six to eight weeks from surgery. In the case of a longitudinal tear repair, post-operative recommendations are dependent on the extent of the repair.

Results

Tendoscopy of the peroneal tendons was first introduced by van Dijk and Kort in 1998.13 As a diagnostic procedure, peroneal tendoscopy was revised by Panchbhavi and Trevino.14 Findings included a tendinous structure between the peroneus longus and brevis, a low-lying muscle belly of the peroneus brevis and a peroneus quartus tendon. None of the findings were apparent on pre-operative magnetic resonance imaging, and excision of these tendon variants was efficient in solving pain in all patients. Several authors have revised techniques and indications of therapeutic peroneal tendoscopy.15,16

Patients with peroneal adhesions and tenosynovitis seem to benefit most from tendoscopy.17,18 Vega et al reported complete relief of pain in 62.5% in 24 patients with partial ruptures of the peroneals.19 However, three of these patients with tears did not experience changes in symptoms after tendoscopic debridement. The authors also reported excellent results in seven patients treated with tendoscopic deepening of the peroneal groove for tendon subluxation, and in six patients with intrasheath subluxation of the peroneal tendons. Scholten et al had described the technique for deepening the fibular groove for the treatment of peroneal dislocation.20

Marmotti et al reported subjective improvement of lateral ankle pain in five patients who underwent peroneal tendoscopy for post-operative adhesion and scarring.21 Guillo and Calder had excellent results in seven patients with dislocation of peroneal tendons after tendoscopic reconstruction.22 Michels et al reported on the endoscopic treatment of intrasheath peroneal subluxation with excellent results in three patients.23

Overall, level IV and V studies on peroneal tendoscopy reported good to excellent results in most patients, with few complications.24

Posterior tibial tendoscopy

Indications for tendoscopy of the PTT include tenosynovitis, degenerative tears, dislocation, enthesopathies and chronic tendinopathy with dysfunction and flatfoot deformity. Most indications for open surgery of the PTT are now covered by PTT tendoscopy with lower morbidity.

Surgical technique

The operative technique for PTT tendoscopy was first described by Wertheimer1 and later developed in detail by van Dijk et al.25 The procedure may be performed under general, regional or local anaesthesia. With the patient supine, references are marked on the skin to identify the navicular, the PTT, the medial malleolus and the two main portals (Fig. 6). Active inversion and eversion of the foot before anaesthesia may facilitate the identification of anatomical landmarks. It is recommended to use a 2.7 mm scope with an inclination angle of 30° to facilitate access to the tendon, but a 4.0 mm arthroscope may also be used for most PTT tendoscopies. A thigh tourniquet is applied and gravity inflow is used to insufflate the paratenon. Portals are made using a size 11 scalpel. Two portals are usually recommended, between 2 cm and 2.5 cm proximal and distal to the tip of the posteromedial edge of the medial malleolus.

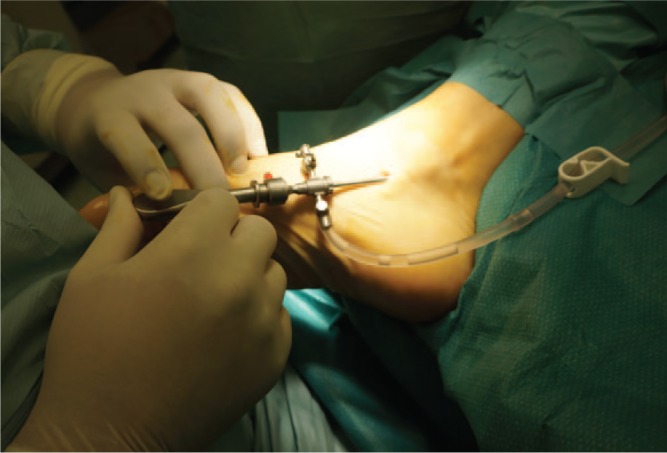

Fig. 6.

Portal placement for posterior tibial tendoscopy: 1) navicular; 2) medial malleolus; 3) distal portal; 4) proximal portal.

The distal portal is created first. A 1 cm skin incision is made over the PTT, halfway between the medial malleolus and the navicular, following the longitudinal axis of the tendon. Subcutaneous dissection is made to expose the PTT sheath. The sheath is opened with a 1 cm incision perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the tendon. This crossed disposition between the skin and the tendon sheath incisions is useful to prevent unintentionally enlarging the entry to the tendon when moving the scope during surgery. The arthroscope with blunt trocar is introduced and the tendon sheath is inspected without saline to gain information on synovitis. Following ‘dry inspection’, the sheath is filled with saline. While inverting the foot, the arthroscope is advanced carefully to inspect the complete PTT up to the vinculum, at around 4 cm proximal to the tip of the medial malleolus (Fig. 7). Under direct visualisation, the insertion of a spinal needle helps to place the skin incision for the proximal portal around 3 cm proximal to the tip of the medial malleolus. Special care should be taken to orientate the needle and the scalpel obliquely so as not to penetrate and damage the tendon. With the arthroscope in the distal portal, a blunt probe and a shaver system may be introduced through the proximal portal (Fig. 8). The complete tendon sheath may be inspected by rotating the scope around the tendon. Synovitis or partial tears may be debrided with a shaver.

Fig. 7.

Posterior tibial tendoscopy. Introduction of blunt trocar through the distal portal.

Fig. 8.

Posterior tibial tendoscopy revealing a partial tear in a rheumatoid patient.

At the end of the procedure, portals are closed with absorbable sutures. A compression bandage is recommended for the first 24 hours and then an adhesive bandage is used to cover the skin incisions. Weight-bearing is allowed as tolerated immediately after surgery (provided associated procedures do not require the patient to be non-weight-bearing, i.e. calcaneal osteotomy), and active inversion and eversion movements are encouraged.

Results

Following the initial description by Wertheimer et al,1 the first series of patients that underwent PTT tendoscopy was presented by van Dijk et al.25 Van Dijk et al reported very elegantly on the surgical technique and on the outcome of 16 patients with posteromedial pain on palpation over the PTT. Although with heterogeneous indications (diagnostic procedures in five patients), most patients were free of pain and showed no complications. Special attention was focused on the pathological thickening of the free edge of the vinculum. The vinculum was usually located some 4 cm proximal to the posterior edge of the medial malleolus and connected the tendon to the tendon sheath. Patients presenting with pain located around the vinculum region seemed to benefit from tendoscopic resection.

Bulstra et al published their experience with a series of 33 patients who underwent tendoscopy with good results for pathologic vincula and rheumatoid arthritis, but poor results for adhesiolysis, all with a low complication rate.26

Chow et al reported on a series of six patients with synovectomy due to stage I PTT dysfunction with no complications and no progression to stage II PTT dysfunction.27 Khazen and Khazen performed PTT tendoscopies in nine patients with stage I PTT dysfunction, with pain improvement in eight patients.28 Lui reported on the use of endoscopic-assisted PTT reconstruction for stage II dysfunction.29 Hua et al published a retrospective review of a series of 15 patients with PTT disorders with a posterior arthroscopic approach with no neurovascular complications and just one patient with a poor outcome.30

Overall, the best outcome was registered for the resection of pathological vincula, with more discrete results for adhesiolysis.31

Other tendons

Extensor digitorum longus, extensor hallucis longus and flexor digitorum longus tendoscopies have been performed for the treatment of tenosynovitis, tendinopathy, ganglion, Z-lengthening and fibrous adhesions, but only level V studies are available. Maquirriain presented a case report of endoscopic debridement of tibialis anterior tendon chronic tenosynovitis.32 Tendoscopy was performed by Lui to drain an extensor hallucis longus ganglion and to assist in the repair of a neglected tendon rupture by identifying the proximal stump and performing tenolysis.33 Lui also used tendoscopy to debride synovitis from an extensor digitorum longus tendon.33 Endoscopic synovectomies for flexor digitorum longus tenosynovitis have been reported with resolution of symptoms.34 Tendoscopy around the foot and ankle has also been used for tendon grafting assistance. Tendoscopic harvesting of the anterior tibial and flexor digitorum longus tendons has been used to reinforce posterior tibialis tendon in adult symptomatic flatfoot deformity.35

Complications

General complications common to all tendoscopic procedures around the foot and ankle include deep venous thrombosis, haematoma, keloid scars, nerve pain around the portals, skin burns, adhesions, seromas with chronic fistula, infections and complex regional pain syndrome.

Specific complications for Achilles tendoscopy include sural nerve injury, tendon rupture in cases of aggressive debridement in the insertional region, and residual equinus in cases of excessive tendon fibrosis post-operatively. Pereoneal tendoscopy may be complicated by sural nerve damage. Excessive blurring of the fibula in cases of peroneal instability may result in fibular stress fracture post-operatively. Complications for PTT tendoscopy include posterior tibial nerve injury. Bowstring phenomenon during dorsiflexion is a potential complication related to anterior tibial tendoscopy.

Evidence-based recommendations

Foot and ankle tendoscopy is a relatively new technique, so it is no surprise not to find a solid body of evidence in the current scientific literature to support the use of this procedure in our daily surgical practice. In a recent systematic review of the literature, most studies are levels IV and V, with just one level II study.24 There is still no sufficient evidence to make a recommendation (grade I) for or against tendoscopy of the foot and ankle. Although apparently a safe and effective procedure, tendoscopy still awaits papers of higher levels of evidence before a strong recommendation can be assigned. However, this must not be confused as a recommendation against foot and ankle tendoscopy.

Author’s experience

We incorporated foot and ankle tendoscopies into our practice some eight years ago. We have no experience with extensor digitorum longus, extensor hallucis longus and flexor digitorum longus tendoscopies, but we occasionally scope Achilles, peroneals and PTT. Our patient outcomes are comparable with those presented in this review.

Achilles tendosocopy is our procedure of choice when surgically treating non-insertional tendinopathy. We perform a proximal medial gastrocnemius release in association with Achilles tendoscopy to optimise results. We routinely perform peroneal tendoscopy when operating on a flexible cavovarus foot in association with hindfoot and forefoot osteotomies. Peroneal tendoscopy is also our method of choice when treating intrasheath subluxation, partial tears, post-operative adhesions and scarring, and for the resection of a peroneus quartus tendon. We routinely perform PTT tendoscopy in stage II flatfoot deformity in association with medial sliding calcaneal osteotomy instead of the conventional medial soft-tissue repair (study currently underway). In rheumatic patients, we also perform tendoscopic debridement of PTT in stage I and II PTT dysfunction.

Discussion

Advances in arthroscopic and endoscopic techniques have continued to expand indications for foot and ankle tendoscopy. However, there is little quality evidence-based data in the current literature to support routine use of tendoscopies. Several retrospective reviews have reported on the outcomes of endoscopic treatment for a variety of indications. The diagnostic utility of this technique has become more widely recognised, although for selected indications.

Tendoscopy seems to be particularly useful in the treatment of Achilles non-insertional tendinopathy, but the role of plantaris tendon release is still not clear. Achilles tendoscopy allows for the destruction of neonerves and neovessels surrounding the tendon which may be responsible for pain improvement. Destruction of abnormal neoinnervation has also been the goal of other treatment options for non-insertional tendinopathy such as high-volume image-guided injections. However, there is conflicting evidence to support the use of high-volume injections for Achilles non-insertional tendinopathy.36,37 With respect to acute Achilles ruptures, the only level II study covering assisted repair of the tendon allows for a more precise repair but it is not statistically significant to the final outcome.4 We should then possibly not consider the use of tendoscopy for acute ruptures as it may be associated with higher morbidity and potential complications with no significant improvement over conventional mini-invasive repair.

Peroneal tendoscopy seems to be useful for the occasional resection of symptomatic peroneus quartus (10% to 26% of the population), for the management of intrasheath peroneal subluxation, and for fibular deepening in cases of instability and dislocation. However, the most common indication for peroneal surgery—longitudinal tears—still needs an open approach for the repair.

PTT synovectomy in stage I and II flatfoot deformities may benefit from tendoscopy, although conventional medial soft-tissue repair usually needs an open approach. No specific function is apparently associated with the PTT vinculum. There is no clear explanation for pain resolution following tendoscopic vinculum resection. Further studies are needed to know the real significance of the PTT vinculum.

There are still some limitations for tendoscopy. Extensive longitudinal tendon tears are difficult to repair endoscopically but new suture equipment will make it possible in the future. Foot and ankle tendoscopy offers advantages over open procedures; fewer wound infections; less blood loss; smaller wounds; lower morbidity; quicker recovery; early mobilisation and function, mild post-operative pain and the possibility of being performed under local anaesthesia on an outpatient basis. Nonetheless, sufficient endoscopic skills are needed to avoid neurovascular and skin complications.

Although not yet widely adopted, foot and ankle tendoscopy is gaining popularity among foot and ankle surgeons. Further research is needed in this area to have a more evidence-based approach. Tendoscopy will possibly allow for a future classification of different findings in and around foot and ankle tendons in the same way arthroscopy did. It will be important to establish which findings are physiological or pathological. Visualisation of the tendon is only rivalled by open surgery, but with greater morbidity. To expand the use of this technique, new instruments dedicated to tendoscopy and proper surgical training in a safe environment are required. The development of new suture endoscopic materials will allow for the treatment of longitudinal tears and new gadgets will possibly allow for the harvesting of tendons whenever needed. Meanwhile, tendoscopy is becoming an important diagnostic and therapeutic tool when dealing with selected indications in foot and ankle pathology, but it will still have to wait for papers of higher levels of evidence to become the gold standard treatment for tendon pathology around the foot and ankle.

Footnotes

ICMJE Conflict of Interest Statement: None

Funding

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

References

- 1. Wertheimer SJ, Weber CA, Loder BG, Calderone DR, Frascone ST. The role of endoscopy in treatment of stenosing posterior tibial tenosynovitis. J Foot Ankle Surg 1995;34:15-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van Dijk CN, Sholten PE, Kort N. Tendoscopy (tendon sheath endoscopy) for overuse tendon injuries. Oper Tech Sports Med 1997;5:170-178. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maffulli N, Kader D. Tendinopathy of tendo achillis. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2002;84-B:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Halasi T, Tállay A, Berkes I. Percutaneous Achilles tendon repair with and without endoscopic control. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2003;11:409-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maquirriain J. Surgical treatment of chronic achilles tendinopathy: long-term results of the endoscopic technique. J Foot Ankle Surg 2013;52:451-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pearce CJ, Carmichael J, Calder JD. Achilles tendinoscopy and plantaris tendon release and division in the treatment of non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy. Foot Ankle Surg 2012;18:124-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turgut A, Günal I, Maralcan G, Köse N, Göktürk E. Endoscopy, assisted percutaneous repair of the Achilles tendon ruptures: a cadaveric and clinical study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2002;10:130-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tang KL, Thermann H, Dai G, et al. Arthroscopically assisted percutaneous repair of fresh closed achilles tendon rupture by Kessler’s suture. Am J Sports Med 2007;35:589-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vega J, Cabestany JM, Golanó P, Pérez-Carro L. Endoscopic treatment for chronic Achilles tendinopathy. Foot Ankle Surg 2008;14:204-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thermann H, Benetos IS, Panelli C, Gavriilidis I, Feil S. Endoscopic treatment of chronic mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy: novel technique with short-term results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2009;17:1264-1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lui TH. Treatment of chronic noninsertional Achilles tendinopathy with endoscopic Achilles tendon debridement and flexor hallucis longus transfer. Foot Ankle Spec 2012;5:195-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gossage W, Kohls-Gatzoulis J, Solan M. Endoscopic assisted repair of chronic achilles tendon rupture with flexor hallucis longus augmentation. Foot Ankle Int 2010;31:343-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Dijk CN, Kort N. Tendoscopy of the peroneal tendons. Arthroscopy 1998;14:471-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Panchbhavi VK, Trevino SG. The technique of peroneal tendoscopy and its role in management of peroneal tendon anomalies. Tech Foot Ankle Surg 2003;2:192-198. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bare A, Ferkel RD. Peroneal tendon tears: associated arthroscopic findings and results after repair. Arthroscopy 2009;25:1288-1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sammarco VJ. Peroneal tendoscopy: indications and techniques. Sports Med Arthrosc 2009;17:94-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Scholten PE, van Dijk CN. Tendoscopy of the peroneal tendons. Foot Ankle Clin 2006;11:415-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jerosch J, Aldawoudy A. Tendoscopic management of peroneal tendon disorders. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2007;15:806-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vega J, Golano P, Batista JP, Malagelada F, Pellegrino A. Tendoscopic procedure associated with peroneal tendons. Tech Foot Ankle Surg 2013;12:39-48. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Scholten PE, Breugem SJ, van Dijk CN. Tendoscopic treatment of recurrent peroneal tendon dislocation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21:1304-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marmotti A, Cravino M, Germano M, et al. Peroneal tendoscopy. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2012;5:135-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guillo S, Calder JD. Treatment of recurring peroneal tendon subluxation in athletes: endoscopic repair of the retinaculum. Foot Ankle Clin 2013;18:293-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Michels F, Jambou S, Guillo S. Endoscopic treatment of intrasheath peroneal tendon subluxation. Case Rep Med 2013:274685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cychosz CC, Phisitkul P, Barg A, et al. Foot and ankle tendoscopy: evidence-based recommendations. Arthroscopy 2014;30:755-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van Dijk CN, Kort N, Scholten PE. Tendoscopy of the posterior tibial tendon. Arthroscopy 1997;13:692-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bulstra GH, Olsthoorn PG, Niek van Dijk C. Tendoscopy of the posterior tibial tendon. Foot Ankle Clin 2006;11:421-427, viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chow HT, Chan KB, Lui TH. Tendoscopic debridement for stage I posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2005;13:695-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Khazen G, Khazen C. Tendoscopy in stage I posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Foot Ankle Clin 2012;17:399-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lui TH. Endoscopic assisted posterior tibial tendon reconstruction for stage 2 posterior tibial tendon insufficiency. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2007;15:1228-1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hua Y, Chen S, Li Y, Wu Z. Arthroscopic treatment for posterior tibial tendon lesions with a posterior approach. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015;23:879-883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Monteagudo M, Maceira E. Posterior tibial tendoscopy. Foot Ankle Clin 2015;20:1-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Maquirriain J, Sammartino M, Ghisi JP, Mazzuco J. Tibialis anterior tenosynovitis: avoiding extensor retinaculum damage during endoscopic debridement. Arthroscopy 2003;19:E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lui TH. Extensor tendoscopy of the ankle. Foot Ankle Surg 2011;17:e1-e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lui TH, Chow FY. “Intersection syndrome” of the foot: treated by endoscopic release of master knot of Henry. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011;19:850-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lui TH. Arthroscopy and endoscopy of the foot and ankle: indications for new techniques. Arthroscopy 2007;23:889-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maffulli N, Spiezia F, Longo UG, Denaro V, Maffulli GD. High volume image guided injections for the management of chronic tendinopathy of the main body of the Achilles tendon. Phys Ther Sport 2013;14:163-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Boesen A, Boesen M, Hansen R, et al. 61 high volume injection, platelet rich plasma and placebo in chronic Achilles tendinopathy – a double blind prospective study. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:A39-A40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]