Abstract

Background

Bodyweight-based dosing of tacrolimus (Tac) is considered standard care, even though the available evidence is thin. An increasing proportion of transplant recipients is overweight, prompting the question if the starting dose should always be based on bodyweight.

Methods

For this analysis, data were used from a randomized-controlled trial in which patients received either a standard Tac starting dose or a dose that was based on CYP3A5 genotype. The hypothesis was that overweight patients would have Tac overexposure following standard bodyweight-based dosing.

Results

Data were available for 203 kidney transplant recipients, with a median body mass index (BMI) of 25.6 (range, 17.2-42.2). More than 50% of the overweight or obese patients had a Tac predose concentration above the target range. The CYP3A5 nonexpressers tended to be above target when they weighed more than 67.5 kg or had a BMI of 24.5 or higher. Dosing guidelines were proposed with a decrease up to 40% in Tac starting doses for different BMI groups. The dosing guideline for patients with an unknown genotype was validated using the fixed-dose versus concentration controlled data set.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that dosing Tac solely on bodyweight results in overexposure in more than half of overweight or obese patients.

The oral starting dose of tacrolimus (Tac) in the first trial in humans was 0.15 mg/kg. This starting dose was based on animal studies.1,2 A few years later, in most transplant centers, oral Tac therapy was initiated with doses ranging from 0.10 to 0.20 mg/kg per day administered in 2 equally divided doses.3 This recommended starting dose has not changed since.4

Tac has a narrow therapeutic window and displays large pharmacokinetic variability.5 Even with therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), it can take up to 14 days to reach target concentrations.6 In theory, the sooner target Tac concentrations are attained post transplantation, the more effective it is likely to be in preventing acute rejection.1 Previous studies have suggested that underexposure of Tac could be related to low bodyweight and overexposure to higher bodyweight in kidney transplant recipients.7-10 Available data suggests that being overweight or obese at time of kidney transplantation has a negative effect on both patient and allograft outcomes.11 Overweight kidney transplant recipients have an increased mortality, more delayed graft functions, more acute rejection episodes, more wound infections, and a longer hospital stay compared with patients with a body mass index (BMI) of less than 30.12 The kidney disease improving global outcomes Transplant Workgroup states that dosing of Tac is important and that it is relatively underinvestigated.1 Although the Tac starting dose is based on bodyweight in many centers, dosing algorithms have demonstrated that bodyweight does not have a statistically significant influence on Tac clearance.13,14 The evidence that Tac elimination is linearly related to total bodyweight remains thin.

In 2003, the majority (60%) of kidney transplant recipients were overweight (BMI, 25-30) or obese (BMI ≥ 30) at the time of transplantation.11 With global obesity on the rise, this number is likely to increase even further and prompts the question if it is justified to continue to base the Tac starting dose on bodyweight. In this study, we investigated whether Tac dosing based on bodyweight leads to the achievement of Tac target whole-blood exposure in overweight patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Aims

The aim of this study was to investigate whether a Tac starting dose based on bodyweight leads to the achievement of Tac target whole-blood predose concentrations (C0) in overweight patients on day 3 after transplantation. This was defined as the first steady state concentration attained after 5 unaltered Tac doses. The subsequent dose was determined using TDM. The prespecified Tac C0 target range was 10 to 15 ng/mL. The hypothesis was that overweight patients are overdosed if the starting dose is strictly based on bodyweight alone. Furthermore, the influence of CYP3A5 genotype on the relationship between bodyweight (or BMI) and Tac exposure was investigated.

Patients

The patients in this study were kidney transplant recipients who participated in a randomized-controlled trial investigating whether adaptation of the Tac starting dose according to CYP3A5 genotype increases the proportion of kidney transplant recipients reaching the target Tac predose concentration range (10-15 ng/mL) at first steady-state. After day 3, the physicians were allowed to adapt the Tac dose based on whole-blood concentration measurements. The primary outcomes of this trial were presented in a separate publication.15

In this trial, patients were randomized to receive Tac in either the standard, bodyweight-based dose of 0.20 mg/kg per day according to the package insert,4 or to receive a dose based on their CYP3A5 genotype. CYP3A5 expressers (ie, carriers of 1 or 2 CYP3A5*1 alleles) received 0.30 mg/kg per day, whereas the nonexpressers (CYP3A5*3 homozygotes) received 0.15 mg/kg per day. The additional immunosuppressive therapy was identical for all patients and consisted of basiliximab, mycophenolic acid, and prednisolone.15 The only inclusion criteria for the post hoc analysis presented here was that there had to be a Tac C0 available on day 3 after transplantation.

Tac Concentration Measurement

As described previously,15 the Tac C0 was measured in the laboratory of the Erasmus MC using 2 different immunoassays: antibody-conjugated magnetic immunoassay (ACMIA) and enzyme multiplied immunoassay technique (EMIT). The measurements obtained with EMIT were systematically approximately 15% higher than those obtained with ACMIA. The weight of patients measured with the 2 different assays was not significantly different. The mean weight of the patients measured with ACMIA was 79.6 kg (95% confidence interval, 77-82.2 kg) and for EMIT 78.4 kg (95% confidence interval, 74-82.9 kg). The lower limits of detection were 1.5 ng/mL (ACMIA) and 2.0 ng/mL (EMIT). In this study, the lowest Tac concentration was 2.6 ng/mL. The upper limit of detection was 30.0 ng/mL. For calculation purposes, Tac C0 above the detection limit was set at 30.0 ng/mL. For further details on the Tac concentration measurement, the reader is referred to our previous publication.15

Dosing Guidelines

Dosing guidelines were developed and validated retrospectively in an independent cohort of patients that participated in the fixed-dose versus concentration controlled (FDCC) study.16 All Tac concentrations were scaled to the theoretical starting dose of 0.2 mg/kg. The percentage of patients on target and the median Tac concentration on day 3 after transplantation were compared before and after utilization of the dosing guideline.

Statistical Analysis

For the analysis, the data were divided into 3 groups: the standard-dose group (SDG), the genotype-based group (GBG), and all patients (SDG plus GBG) scaled to the standard bodyweight dose. The latter group was created to be able to compare the C0 of all patients, irrespective of whether the starting dose was adjusted according to genotype. The scaled C0 was calculated by dividing the C0 by the actual dose per kg bodyweight and multiplying this by 0.2. Categorical variables are reported using frequency tables and percentages, and continuous variables are expressed as medians with ranges. Tac overexposure was defined as a Tac concentration above 15 ng/mL, and underexposure as below 10 ng/mL. The correlation between Tac C0 and bodyweight (or BMI) was investigated by calculating the goodness of fit. Dosing guidelines were calculated using linear regression lines. Descriptive statistics were generated, and all tests were 2-tailed, and statistical significance was defined as a P value less than 0.05. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

For this post hoc analysis, data were available for 203 kidney transplant recipients. A total of 34 patients were not included in this analysis because no data on C0 was available on day 3 after transplantation due to logistic issues (usually missed sample collection on Sunday).15 The patient characteristics are described in Table 1. The median bodyweight was 78.9 kg with a range of 37.6 to 123.1 kg, whereas the median BMI was 25.6 kg/m2 with a range of 17.2 to 42.2 kg/m2. Of all patients, 102 (50.2%) were overweight (BMI > 25), 40 (19.7%) were obese (BMI > 30), and 1 patient was morbidly obese (BMI > 40).

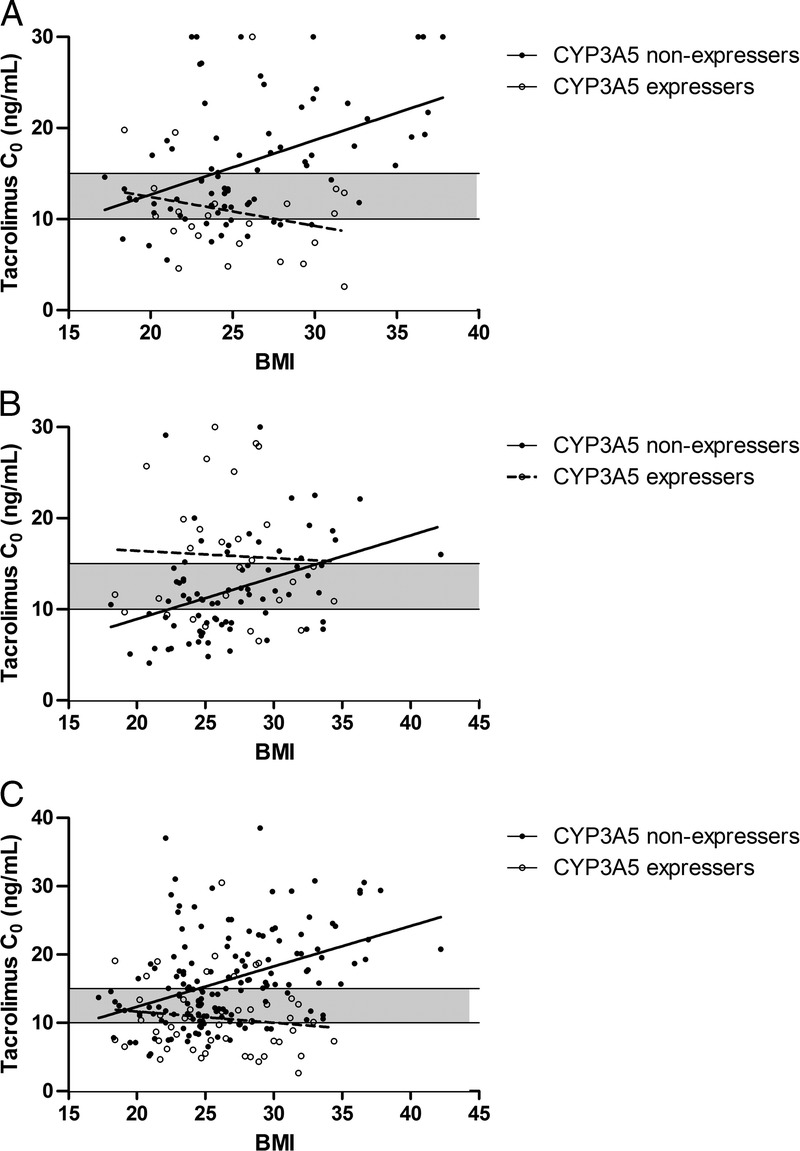

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics

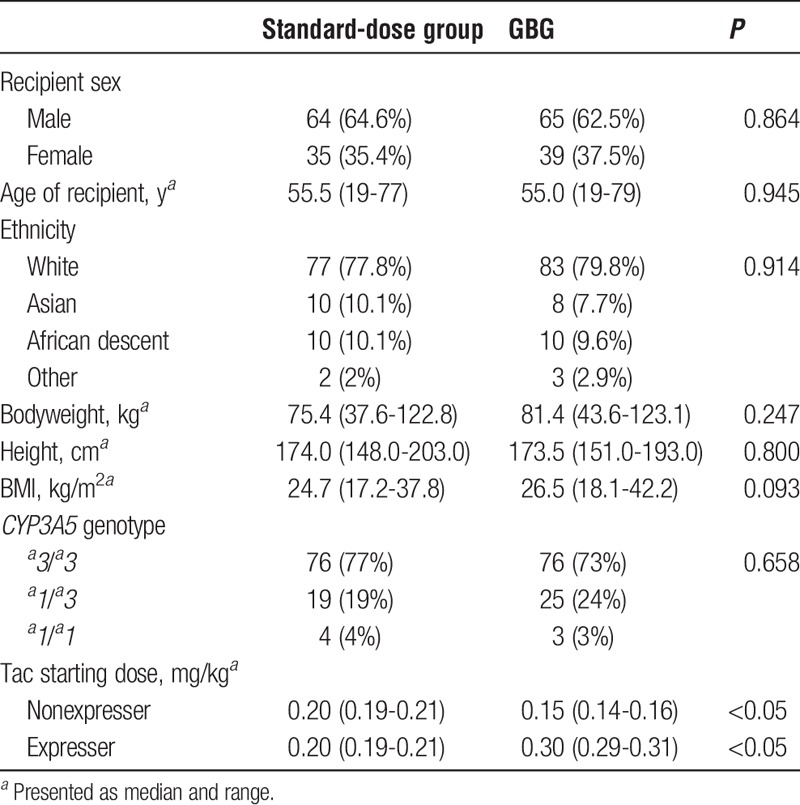

Bodyweight

In the SDG, the overweight or obese patients had significant higher median Tac C0 (15.9 ng/mL) after 5 unaltered Tac doses than patients with a BMI smaller than 25 (12.0 ng/mL), with a P value of 0.011. Of the overweight or obese patients, 57.8% were overexposed. The CYP3A5 expressers on average had lower Tac C0 than the CYP3A5 nonexpressers (10.7 ng/mL vs 16.2 ng/mL, P = 0.001). On day 3 after transplantation, a considerable proportion (47%) of nonexpressers was overexposed (Figure 1A). In CYP3A5 expressers, only 13% was overexposed (P = 0.003).

FIGURE 1.

The association between bodyweight, CYP3A5 genotype and Tac C0 on day 3 after transplantation, with the target concentration of 10 to 15 ng/mL shown (shaded area). A, Patients who received 0.20 mg/kg Tac. B, Patients who received Tac in a dose of 0.15 mg/kg (CYP3A5 nonexpressers) or 0.30 mg/kg (CYP3A5 expressers). C, All patients scaled to 0.2 mg/kg dose.

Figure 1B shows the relationship between bodyweight and Tac C0 in the GBG. In this group, all nonexpressers received 0.15 mg/kg and the expressers 0.30 mg/kg. Of all patients dosed according to genotype, 35.4% of all overweight or obese patients were overexposed. Of all patients in this group, 30% was overexposed, whereas 35% was underexposed.

Figure 1C depicts all patients in the study scaled to the theoretical dose of 0.2 mg/kg per day. Due to scaling of the dose, the maximum Tac concentration depicted in the figure increased to 38.5 ng/mL, rather than the 30 ng/mL cutoff. Of all overweight or obese patients, 53.6% were overexposed. In line with the SDG, a substantial proportion of nonexpressers was above the target range (36%) and over a quarter (27%) was underexposed. The correlation line crosses the upper limit of the target range at 67.5 kg (calculated with the regression line y = 0.12x + 6.9, r2 = 0.08). Of all patients weighing more than 67.5 kg, 40% of nonexpressers was above the target range and 25% was below the target range.

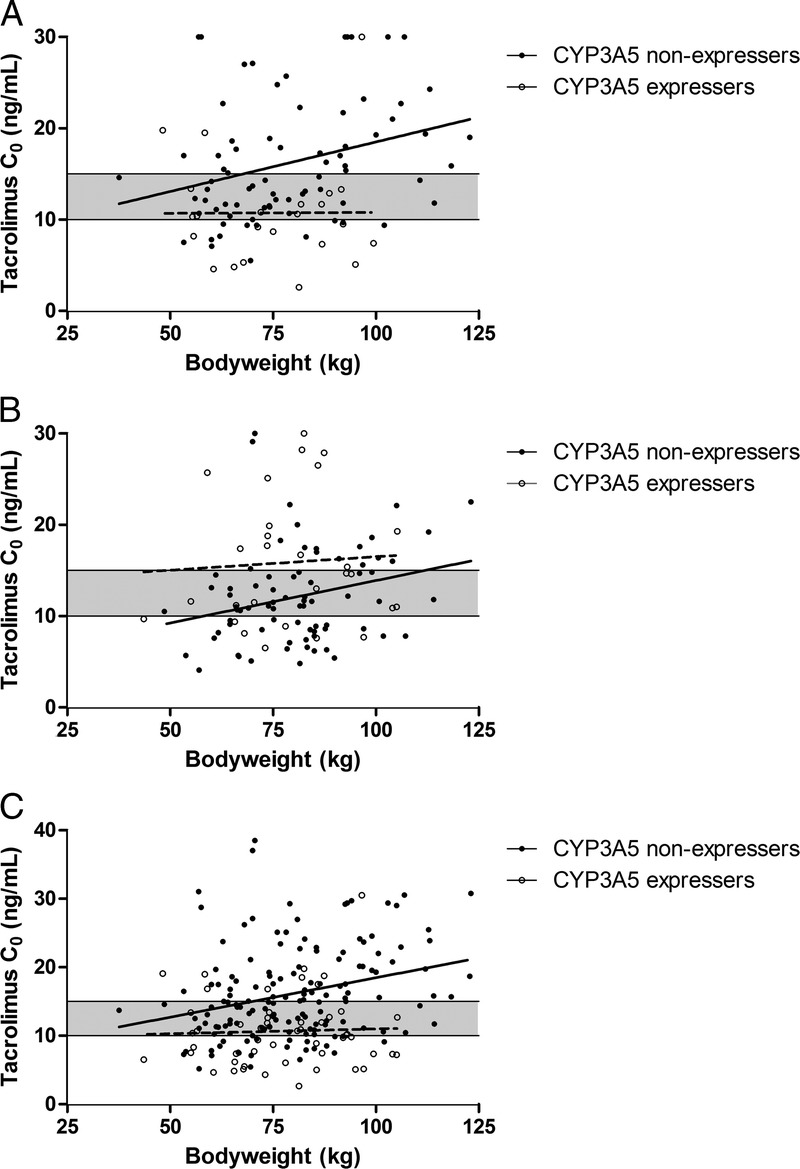

BMI

In the SDG, the nonexpressers were overexposed if the BMI increased, whereas, paradoxically, the expressers had fairly stable exposure regardless of BMI (see Figure 2A). In the GBG, a considerable amount of expressers was overexposed (Figure 2B), whereas the nonexpressers were below target if the BMI was lower than 22.3 kg/m2 and above target if it was higher than 33.2 kg/m2 (y = 0.46 x − 0.26, r2 = 0.15).

FIGURE 2.

The association between BMI, CYP3A5 genotype and Tac C0 on day 3 after transplantation, with the target level of 10 to 15 ng/mL shown (shaded area). A, Patients who received 0.20 mg/kg Tac. B, Patients who received Tac in a dose of 0.15 mg/kg (CYP3A5 nonexpressers) or 0.30 mg/kg (CYP3A5 expressers). C, All patients scaled to 0.2 mg/kg dose.

When scaled to the theoretical standard dose, a considerable amount (36%) of nonexpressers was overexposed (Figure 2C). The correlation line crosses the upper limit of the target range at 24.5 kg/m2 (calculated with the regression line y = 0.59x + 0.53, r2 = 0.17). Of all patients with a BMI greater than 24.5 kg/m2, 44% of nonexpressers were above the target range and 24% were below target.

Overweight patients with a BMI greater than 25 kg/m2 took a median of 6 days to reach the target concentration, compared with 4.5 days in patients with a normal bodyweight (P = 0.083).

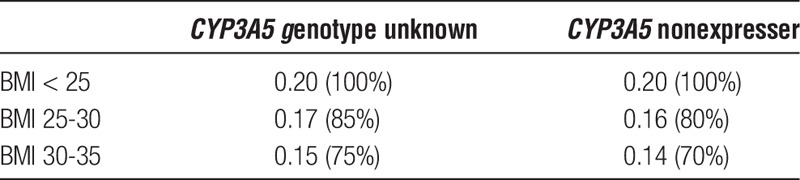

Dosing Guidelines

Dosing guidelines for overweight patients based on BMI are shown in Table 2. The recommendations were calculated with a target C0 of 10 to 15 ng/mL on day 3. A distinction is made between patients in whom the CYP3A5 genotype status is known and in whom it is unknown. In accordance with the CPIC guideline,17 it is not common practice in most centers to genotype patients before transplantation, therefore the guideline for unknown genotype was developed. Unfortunately, there was not a sufficient number of CYP3A5 expressers in our population to be able to calculate specific dosing guidelines based on BMI for this group. No guidelines for patients with a BMI greater than 35 could be developed due to a lack of patients in this category. For a typical patient with a BMI of 28 kg/m2 and an unknown CYP3A5 genotype, the dose should be 0.17 mg/kg (85%) if the standard starting dose is 0.20 mg/kg based on the developed dosing guideline (Table 2). If this same patient is a known CYP3A5 nonexpresser, the dose should be 0.16 mg/kg (80%).

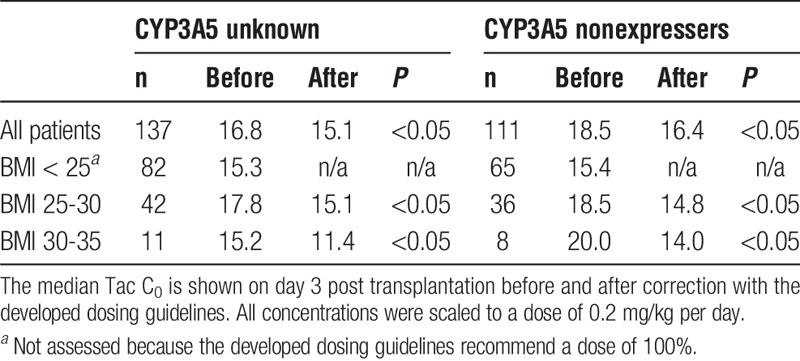

TABLE 2.

Dosing guidelines (mg/kg) based on a patient’s BMI and CYP3A5 genotype

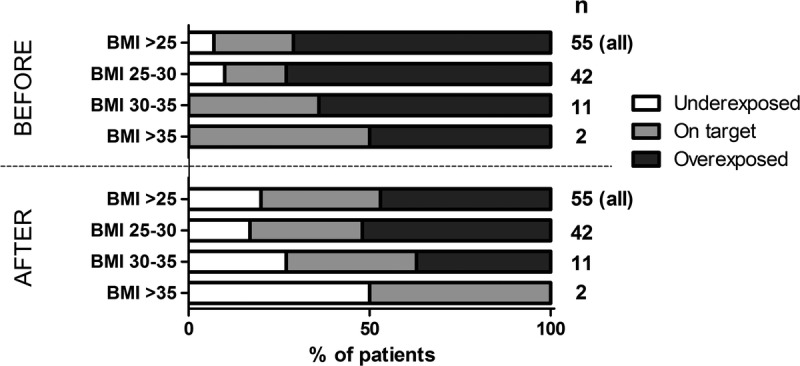

The recommended dosing guidelines were validated retrospectively in an independent cohort of patients that participated in the FDCC study16 by comparing the percentage on target before and after utilization of the guideline, and the median Tac concentration on day 3 after transplantation. The results are shown in Table 3. If CYP3A5 genotype is unknown, 21.8% of overweight patients were on target before utilization of the guideline, and 32.7% afterward. The percentage of patients overexposed dropped from 70.9% to 47.2%. Especially overweight patients (BMI, 25-30) benefit of the dosing guideline with 16.7% of patients on target before, and 31% after applying the dosing guideline. The percentage of patients on target before and after utilization of the dosing guideline is shown in Figure 3. When underweight patients (BMI smaller than 20 kg/m2) were excluded from the analysis, the proportion of patients overexposed and on target remained the same (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Validation of the dosing guidelines: median Tac C0 (ng/mL)

FIGURE 3.

The percentage of patients underexposed, on target and overexposed before and after utilization of the developed dosing guideline in a validation cohort of patients with an unknown genotype.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that dosing Tac solely on bodyweight results in overexposure in a considerable proportion of patients. This is especially the case for overweight and obese patients. Based on the goodness of fit, the association between BMI and Tac exposure seems stronger than the one between bodyweight and Tac. To our knowledge, only 2 studies have investigated the relationship between bodyweight or BMI and Tac exposure at first steady state. Rodrigo et al9 concluded that overweight renal transplant recipients are more prone to develop initial high exposure (ie, a C0 > 15 ng/mL) compared with nonoverweight recipients. Rodrigo et al9 demonstrated that the first Tac C0 tended to be higher than 15 ng/mL in overweight, older kidney transplant recipients. Sawamoto et al18 demonstrated that the average Tac maintenance dose in patients with a BMI greater than 25 kg/m2 is significantly lower compared with that in patients with a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or less. Our study substantiates these findings.

Dosing guidelines for overweight and obese patients were developed and validated for patients with an unknown genotype and CYP3A5 nonexpressers. As a validation cohort we used patients who participated in the FDCC trial. In this multicenter study, Tac was dosed according to local clinical practice, and as a consequence, this is a very heterogeneous group. Despite this, we managed to validate our guidelines.

Unfortunately, no dosing guideline could be developed for CYP3A5 expressers because there were too few CYP3A5 expressers in our population. Also, insufficient obese patients with a BMI greater than 35 were available to validate the dosing guideline in that group. Establishing separate dosing guidelines for overweight patients is not unusual. Other drugs, such as aminoglycosides, are dosed using ideal body weight in overweight patients.19 However, aminoglycosides are hydrophilic drugs, whereas Tac is lipophilic. Overweight patients have a larger fat compartment, and therefore, adjusting the dose of hydrophilic drugs based on total bodyweight would lead to overexposure. However, for lipophilic drugs, a larger volume of distribution would be expected in overweight patients, and therefore, choosing the dose based on total bodyweight seems logical. Miyamoto et al20 demonstrated that the Tac concentration in fat tissue was lower than what one would expect based on the lipophilicity of the drug. This substantiates the present finding that the Tac dose should not be entirely based on bodyweight in obese patients. An explanation for this counterintuitive finding could be that Tac is extensively distributed into erythrocytes which have a high content of FK-binding proteins to the receptor of Tac.4 Although with an increasing bodyweight, the blood plasma volume also increases, this occurs to a lesser extent. Theoretically, the Tac initial dose should be based on this increase in blood plasma volume rather than the increase in bodyweight.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to give dosing guidelines for overweight and obese transplant recipients. A subject for future research could be the influence of other genetic polymorphisms in, for example, CYP3A4 which has also been associated with altered Tac clearance. Especially, CYP3A4*22 is interesting because it is associated with a lower Tac dosage after renal transplantation.21

The biggest limitation of this study is that it is a post hoc analysis. It was unplanned and therefore the apparent differences and associations could be coincidental. The second limitation is that more than three quarters of the studied population was white, and only 10% was from African descent. Research has shown that African-American kidney transplant recipients require a higher Tac dose regardless of their CYP3A5 genotype.22,23 The third limitation is that Tac concentrations were measured with immunoassays, instead of using mass spectrometry which is nowadays considered the criterion standard. In our center, immunoassays were used for the routine determination of Tac at the start of the trial. Many transplant centers worldwide still rely on immunoassays for TDM of Tac. The final limitation is that the target range of 10 to 15 ng/mL we aimed for may now be regarded as rather high although the precise therapeutic range for Tac is still unclear.24-27

In conclusion, basing the Tac starting dose solely on bodyweight leads to overexposure in more than one third of patients, and over half of overweight or obese patients. Basing the Tac starting dose on BMI in overweight patients, whether or not in combination with CYP3A5 genotype, could reduce overexposure of Tac early after transplantation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the research nurses Mrs. M.J. Boer -Verschragen, Ms. M. Cadogan, and Mrs. N.J. de Leeuw -van Weenen for their valuable contribution to this clinical study. The authors are appreciative of the work conducted by the co-authors of the original study, for without them this post hoc analysis would not have been possible. The original study was an investigator-initiated study. All authors had full access to all the data and have full responsibility for the contents of this publication and the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Published online 19 January, 2017.

T. van Gelder has received lecture fees from Chiesi Pharmaceuticals and Astellas Pharma B.V., and consulting fees from Astellas Pharma B.V., Novartis Pharma B.V., Roche Pharma, Teva Pharma and Sandoz Pharma. D.A. Hesselink has received lecture and consulting fees, as well as grant support from Astellas Pharma B.V., Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chiesi Pharmaceuticals, MSD Pharmaceuticals, Novartis Pharma B.V., and Roche Pharma. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Mrs. Bouamar received a grant (grant number 017006041) from The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) (grant number 017006041). Ms. Shuker received a grant (grant number IP11.44) from the Dutch Kidney Foundation (Nierstichting Nederland).

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

L.A., B.W., T.G. and D.H. contributed to the design of the work and wrote the manuscript. R.B. and N.S. collected data. B.K and R.S enabled data collection. L.A. performed the analyses. J.T., R.B., N.S., R.S., B.K., wrote the manuscript. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Transplant Work G. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:S1–S155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starzl TE, Todo S, Fung J, et al. FK 506 for liver, kidney, and pancreas transplantation. Lancet. 1989;2:1000–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jusko WJ, Thomson AW, Fung J, et al. Consensus document: therapeutic monitoring of tacrolimus (FK-506). Ther Drug Monit. 1995;17:606–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Astellas Pharma U, Inc. PROGRAF Tacrolimus capsules, tacrolimus injection (for intravenous infusion only). 2009. <https://www.astellas.us/docs/prograf.pdf>.

- 5.Staatz CE, Tett SE. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tacrolimus in solid organ transplantation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43:623–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thervet E, Loriot MA, Barbier S, et al. Optimization of initial tacrolimus dose using pharmacogenetic testing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87:721–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Press RR, Ploeger BA, den Hartigh J, et al. Explaining variability in tacrolimus pharmacokinetics to optimize early exposure in adult kidney transplant recipients. Ther Drug Monit. 2009;31:187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kausman JY, Patel B, Marks SD. Standard dosing of tacrolimus leads to overexposure in pediatric renal transplantation recipients. Pediatr Transplant. 2008;12:329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodrigo E, de Cos MA, Sánchez B, et al. High initial blood levels of tacrolimus in overweight renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1453–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Størset E, Holford N, Hennig S, et al. Improved prediction of tacrolimus concentrations early after kidney transplantation using theory-based pharmacokinetic modelling. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78:509–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman AN, Miskulin DC, Rosenberg IH, et al. Demographics and trends in overweight and obesity in patients at time of kidney transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:480–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lafranca JA, IJermans JN, Betjes MG, et al. Body mass index and outcome in renal transplant recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2015;13:111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Passey C, Birnbaum AK, Brundage RC, et al. Dosing equation for tacrolimus using genetic variants and clinical factors. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72:948–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrews LM, Riva N, de Winter BC, et al. Dosing algorithms for initiation of immunosuppressive drugs in solid organ transplant recipients. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2015;11:921–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shuker N, Bouamar R, van Schaik RH, et al. A Randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of CYP3A5 genotype-based with body-weight-based tacrolimus dosing after living donor kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:2085–2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Gelder T, Silva HT, de Fijter JW, et al. Comparing mycophenolate mofetil regimens for de novo renal transplant recipients: the fixed-dose concentration-controlled trial. Transplantation. 2008;86:1043–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birdwell KA, Decker B, Barbarino JM, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guidelines for CYP3A5 Genotype and Tacrolimus Dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;98:19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sawamoto K, Huong TT, Sugimoto N, et al. Mechanisms of lower maintenance dose of tacrolimus in obese patients. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2014;29:341–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polso AK, Lassiter JL, Nagel JL. Impact of hospital guideline for weight-based antimicrobial dosing in morbidly obese adults and comprehensive literature review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2014;39:584–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyamoto Y, Uno T, Yamamoto H, et al. Pharmacokinetic and immunosuppressive effects of tacrolimus-loaded biodegradable microspheres. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:392–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang JT, Andrews LM, van Gelder T, et al. Pharmacogenetic aspects of the use of tacrolimus in renal transplantation: recent developments and ethnic considerations. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2016;12:555–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanghavi K, Brundage RC, Miller MB, et al. Genotype-guided tacrolimus dosing in African-American kidney transplant recipients. Pharmacogenomics J. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oetting WS, Schladt DP, Guan W, et al. Genomewide Association Study of Tacrolimus Concentrations in African American Kidney transplant recipients identifies multiple CYP3A5 alleles. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:574–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ekberg H, Tedesco-Silva H, Demirbas A, et al. Reduced exposure to calcineurin inhibitors in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2562–2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bouamar R, Shuker N, Hesselink DA, et al. Tacrolimus predose concentrations do not predict the risk of acute rejection after renal transplantation: a pooled analysis from three randomized-controlled clinical trials(†). Am J Transplant. 2013;13:1253–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Opelz G, Döhler B. Effect on kidney graft survival of reducing or discontinuing maintenance immunosuppression after the first year posttransplant. Transplantation. 2008;86:371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CTS Collaborative Transplant Study Newsletter 1:2014. http://www.ctstransplantorg/public/newsletters/2014/pdf/2014-1pdf.