Abstract

HIV-1 entry and fusion with target cells is an important target for antiviral therapy. However, a few currently approved treatments are not effective as monotherapy due to the emergence of drug resistance. This consideration has fueled efforts to develop new bioavailable inhibitors targeting different steps of the HIV-1 entry process. Here, a high-throughput screen was performed of a large library of 100,000 small molecules for HIV-1 entry/fusion inhibitors, using a direct virus–cell fusion assay in a 384 half-well format. Positive hits were validated using a panel of functional assays, including HIV-1 specificity, cytotoxicity, and single-cycle infectivity assays. One compound—4-(2,5-dimethyl-pyrrol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-benzoic acid (DPHB)—that selectively inhibited HIV-1 fusion was further characterized. Functional experiments revealed that DPHB caused irreversible inactivation of HIV-1 Env on cell-free virions and that this effect was related to binding to the third variable loop (V3) of the gp120 subunit of HIV-1 Env. Moreover, DPHB selectively inhibited HIV-1 strains that use CXCR4 or both CXCR4 and CCR5 co-receptors for entry, but not strains exclusively using CCR5. This selectivity was mapped to the gp120 V3 loop using chimeric Env glycoproteins. However, it was found that pure DPHB was not active against HIV-1 and that its degradation products (most likely polyanions) were responsible for inhibition of viral fusion. These findings highlight the importance of post-screening validation of positive hits and are in line with previous reports of the broad antiviral activity of polyanions.

Keywords: : fusion inhibitor, HIV envelope glycoprotein, fusion intermediates, virus inactivation, V3 loop

Introduction

HIV-1 initiates infection by fusing its lipid envelope with the cell membrane—a process that is mediated by HIV-1 Env.1,2 The formation of ternary complexes between the gp120 subunit of Env, CD4, and co-receptors (CCR5 or CXCR4) triggers the refolding of the transmembrane subunit gp41 into the final six-helix bundle structure that promotes membrane merger.3,4 The HIV-1 Env is the major target of neutralizing antibodies and fusion inhibitors (e.g., Tilton and Doms5 and Julien et al.6). However, only small-molecule fusion inhibitors approved for use in patients are currently limited to a CCR5 antagonist maraviroc. While there are more fusion inhibitors in the pipeline, the ease with which HIV-1 develops resistance to these inhibitors highlights the need for novel compounds that inhibit HIV-1 fusion via distinct mechanisms. There is also a need for additional inhibitory compounds that could serve as probes to use for studies of HIV-1 entry and potentially to advance to clinical trials.

Many small-molecule inhibitors of HIV-1 entry that interfere with CD4-induced conformational changes in gp120,7,8 co-receptor binding,9–11 and the gp41 six-helix bundle formation12–23 have been identified by high-throughput screening (HTS). The use of cell culture–based fusion assays for screening for HIV-1 fusion inhibitors has the advantage of revealing functionally relevant hits. In fact, the recent large-scale screen of small-molecule libraries for inhibitors of HIV-1 Env-mediated cell–cell fusion identified a novel compound 18A with a distinct mechanism of action.24 This compound interferes with early conformational changes in Env glycoprotein induced upon CD4 binding that entail disruption of the trimeric apex structure.

A HTS campaign was carried out using the recently adapted direct HIV–cell fusion assay in order to identify new class of compounds that block HIV-1 entry/fusion.25 This direct virus–cell fusion assay has the potential to detect novel compounds that interfere with HIV-1 entry through an endocytic pathway, which appears to be the main entry route in HeLa-derived target cells.26–28 Also, a modification of this assay can reveal inhibitors that directly inactivate cell-free HIV-1 (virucidal compounds), which is difficult to detect using a cell–cell fusion assay due to the inherent ability of cells to express new Env and repair the plasma membrane defects. From screening of a diversity library of small molecules for HIV-1 fusion inhibitors, multiple promising hits were identified. Extensive counter-screening and validation showed that only one compound—4-(2,5-dimethyl-pyrrol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-benzoic acid (DPHB)—specifically inhibited CXCR4-tropic (X4-tropic) HIV-1 fusion without causing long-term cell toxicity. It was found that this compound promoted spontaneous inactivation of Env by interacting with the gp120 V3 loop. However, further evaluation of this compound unexpectedly revealed that pure compound was not active against HIV-1, and that its degradation products (most likely polyanions) were responsible for inhibition of viral fusion. These findings highlight the importance of careful post-screening validations of primary positive hits and support a broad-range antiviral activity of negatively charged polymers.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

DPHB was from ChemDiv (San Diego, CA) and from Millipore (Billerica, MA). AMD3100 and poly-L-lysine were from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). BMS-529 was from Aurum Pharmatech (Howell, NJ). The C52L recombinant peptide was a kind gift from Min Lu (University of New Jersey, NJ). The CCF4 acetoxymethyl ester (CCF4-AM) β-lactamase substrate (GeneBLAzer in vivo detection kit) was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Cell Lines

TZM-bl cells obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (ARRRP) and HEK 293T/17 cells from (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma–Aldrich) and 100 IU/mL of penicillin-streptomycin (Gemini Bio-Products, Sacramento, CA). Growth medium for HEK 293T/17 cells was supplemented with 0.5 mg/mL G418 (Cellgro; Mediatech, Manassas, VA). NP2 cells stably expressing CD4, CXCR4, and the C-terminal fragment of dual-split Renilla luciferase-green fluorescent protein (DSP2, referred to as N4X4-DSP2) and HEK 293T cells stably expressing the N-terminal fragment DSP1 (293T-DSP1 cells) were gifts from H. Hoshino, N. Hosoya, and A. Iwamoto (University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan). NP2 cells were grown in minimal essential medium (MEM; Cellgro) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 IU/mL of penicillin-streptomycin, and 4 μg/mL of blasticidin (Bioworld, Atlanta, GA).

Plasmids

The dual-tropic envelope R3A expression vector pHPG-R3A-Env was a gift from J. Hoxie (University of Pennsylvania), the pCAGGS-HXB2-Env and pCAGGS-JRFL-Env vectors were provided by J. Binley (Torrey Pines Institute, CA), the pBaL26-Env vector was a gift from P. Clapham (University of Massachusetts), pHXB2V3Bal was a gift from Dr. Robert Doms (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA) and the pMDG-VSVG plasmid expressing VSV-G was a gift from J. Young (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA). The HIV-1 proviral clone pR8ΔEnv lacking the env gene was obtained from D. Trono (University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland), and pcRev and PMM310-BlaM-Vpr expressing Rev and β-lactamase (BlaM)-Vpr, respectively, were obtained from the ARRRP.

Virus Production

Pseudoviruses containing BlaM-Vpr were produced, as described previously.27,29 Briefly, a 10 cm dish of HEK 293T/17 cells was transfected with JetPrime reagent (Polyplus Transfection, Illkirch-Graffenstaden, France) using the following plasmids: the viral envelope glycoprotein vector (3 μg), pR8ΔEnv (2 μg), pMM130-BlaM-Vpr (2 μg), and pcRev (1 μg). Twelve hours after transfection, the medium was replaced with phenol red-free DMEM growth medium, and pseudoviruses were harvested 48 h after transfection. The supernatant was centrifuged for 5 min at 350 g, filtered through a 0.45 μm filter, and, when indicated, concentrated using the LentiX reagent (Clontech Laboratories, Madison, WI), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Pseudoviruses were aliquoted and stored at −80°C. Infectious titers were determined by a β-galactosidase assay in TZM-bl cells, as described by Miyauchi et al.27

Virus–Cell Fusion

The virus–cell fusion assay, hereafter referred to as beta-lactamase (BlaM) assay, takes advantage of the ability to incorporate the beta-lactamase enzyme into HIV-1 pseudoviruses using the BlaM-Vpr chimera.30 The BlaM activity in the cytoplasm that results from the virus–cell fusion is detected by loading the cells with the BlaM substrate, as described below. This method has been developed in different plate formats in the authors' laboratory, including the miniaturized assay in 384-half-well plates used for the primary screen of small molecules.25 A conventional 96-well plate format was also employed for characterization of the hit compounds. Specific parameters to each format are listed in Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/adt). TZM-bl cells were seeded in Costar 384-half-well black-wall clear bottom plates (Cat. #3542). After incubating overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator, the plates were briefly chilled on ice. BlaM-Vpr containing pseudoparticles were added (at a multiplicity of infection [MOI] of ∼1) to cells and centrifuged at 1,550 g for 30 min at 4°C. Library compounds were then added to the cells, and plates were incubated for 90 min at 37°C, 5% CO2. To create a temperature-arrested stage (TAS) of HIV-1 fusion, cells were incubated with pseudoviruses for 3 h at 20.5°C, and a compound was added before shifting to 37°C to induce viral fusion. The fusion reaction was stopped by briefly chilling the plates on ice, and cells were loaded with the CCF4-AM substrate, as described previously.26,27 Cells were incubated overnight at 12°C, and the fusion activity was determined by a FRET-based assay and measured, using Envision Multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) with excitation at 400 nm and emission at 460 nm and 520 nm. The viral fusion signal was calculated and expressed as a ratio using the following equation: VF = F460/F520 × 100.

Cell viability was measured after addition of the CellTiter-Blue reagent (Promega, Madison, WI) and reading the fluorescence at Ex.560/Em.590 nm, as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Screening Data Analysis

Screening data were analyzed using Cambridge BioAssay software. Z′ and signal-to-background (S/B) ratio were calculated for each plate to monitor the performance of the screening:

Z′ = 1 – (3 × SDvehicle control + 3 × SDbackground)/(VFvehicle control – VFbackground)

S/B = VFvehicle control/VFbackground.

The effect of compound on fusion activity was expressed as % of control and calculated according to the following equation:

% of control = (VFcompound – VFbackground)/(VFvehicle control – VFcompound) × 100.

Vehicle controls are wells containing virus and vehicle (DMSO), and background are wells without virus.

The toxicity compounds in the primary screening were evaluated by calculating the fold over control (FOC) of 520 nm signal for the BlaM activity (VF) measurement. Primary hits were defined by the compounds with % of control <50 without significantly affecting the 520 nm signal (FOC >0.5)

Virucidal Assay

BlaM-Vpr pseudoparticles were immobilized on 96-well black-wall clear-bottom plates coated with poly-L-lysine (0.01%) by centrifugation at 1,550 g at 4°C for 30 min. Plates were washed with complete phenol red-free DMEM and incubated in the presence of indicated concentrations of inhibitors/compounds for 90 min at 37°C, 5% CO2. Plates were washed once more to remove compounds and overlaid with TZM-bl cells (2 × 105 cells/well) harvested from the culture dishes using a non-enzymatic CellStripper solution (Cellgro). To promote attachment, cells were centrifuged onto immobilized viruses at 1,550 g for 30 min at 4°C. Medium was replaced by complete DMEM containing indicated inhibitors or DMSO (vehicle control) and the plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. Virus fusion was measured by the resulting BlaM activity, as described above.

Infectivity Assay

TZM-bl cells seeded the day before the experiment in complete DMEM (5 × 104 cells/well) were exposed to HIV-1 pseudoparticles (MOI ∼0.2) on ice and centrifuged for 30 min at 1,550 g, 4°C. Cells were washed, and a medium containing inhibitors was added as indicated. After 90 min of incubation at 37°C, 5% CO2, cells were briefly chilled on ice, and C52L peptide was added at 2 μM. Cells were then incubated for 46 h at 37°C, 5% CO2, and the resulting luciferase signal was read using a TopCount NXT plate reader, after adding the BrightGlo™ luciferase substrate (Promega).

Cell–Cell Fusion

HEK 293T cells stably expressing DSP1 were transfected with 3 μg of pCAGGS-HXB2-Env and 1 μg of pcRev using the JetPrime reagent 24 h before the experiment. In parallel, cells expressing DSP2 were seeded onto a black-wall clear-bottom 96-well plate pre-coated with collagen (0.1 mg/mL; Sigma–Aldrich). The next day, 293T-DSP1 cells were loaded with 40 μM Enduren (Promega) in Hanks balanced salt solution for 2 h at 37°C, detached using a non-enzymatic CellStripper solution, and overlaid onto cells expressing DSP2 in the absence or in the presence of inhibitors. Cell fusion was initiated by raising the temperature to 37°C for 2 h, and luciferase activity was measured using a TopCount NXT plate reader (PerkinElmer).

Cell Viability Assays

The CellTiter-Blue assay used in the primary HTS is based on the ability of living cells to convert a redox dye (resazurin) into a fluorescent end product (resorufin). Nonviable cells rapidly lose metabolic capacity and thus do not generate a fluorescent signal. In the follow-up experiments, long-term cytotoxicity of compounds was measured using a colorimetric CellTiter 96 AQueous assay (Promega), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Briefly, TZM-bl cells were seeded in 96-well plate in complete DMEM at 5 × 104 cells per well the day before the experiment, and incubated in the presence of indicated inhibitor. Cell viability was measured in parallel after 24 and 48 h of incubation by using a colorimetric CellTiter 96 AQueous assay (Promega), according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

UV–Visible Spectra

Compound solutions were diluted in distilled water to a final concentration of 5 μM, and the UV–visible absorbance spectrum was measured using a NanoDrop 8000 spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA).

Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry was performed by the Integrated Core Facilities at the Emory University using a LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer.

Results

Screen for HIV-1 Fusion Inhibitors and Identification of Positive Hits

Previously, an enzymatic live cell-based virus fusion assay (BlaM assay) was adapted to a 384 half-well plate format.25 The working volume for a 384 half-well plate, which has half the bottom area of a regular 384-well plate, is 5–40 μL compared with 20–80 μL for a regular 384-well plate. Using a 348 half-well plate enables considerable cost saving for the expensive BlaM substrate. This assay yields the Z′ factor ≥0.5 and S/B ≥3, demonstrating compatibility with HTS. This assay was used to screen a diversity library of 100,000 compounds from ChemDiv for HIV-1 entry/fusion inhibitors in the indicator TZM-bl cells expressing CD4, CXCR4, and CCR5. The cell's ability to de-esterify and retain the BlaM substrate (measured as the signal at 520 nm) was used as a proxy for cell viability in the primary screen format. The average Z′ across 313 screening plates was 0.68 ± 0.08, and S/B was 4.8 ± 1.38, indicating robust assay performance for HTS. Figure 1A shows the representative results for more than one third of the screened compounds. The primary screen identified 666 positive compounds that reduced HIV-cell fusion by >50% after excluding possible toxic compounds with FOC of the F520 nm signal <0.5. These selection criteria allowed selecting non-toxic hits with the expected IC50 value <25 μM (the concentration of compounds used in the primary screen). The hit rate was thus 0.67%.

Fig. 1.

High-throughput screening (HTS) for HIV-1 fusion inhibitors in a miniaturized 384 half-well format and hit validation. (A) Scatter plot of screening data for a subset of 36,481 compounds. Points falling below the dashed line are among 666 positive hits with % of control <50 have been identified from 100,000 compounds screening. (B) A flow chart for hit validation using functional assays.

Next, all 666 hits representing 73 structure clusters from the 10 mM stock library compounds were cherry-picked and dose–response experiments were carried out (Fig. 1B). Using the primary screening assay described above, each compound was tested at six doses in triplicate samples, and the IC50 values were obtained by non-linear curve fitting. From 666 dose–response curves, a total of 107 compounds exhibited IC50 <20 μM. Of those 107 confirmed hits, 84 were commercially available and were reordered in a powder form from different sources to confirm their inhibitory activity against HIV-1. The reordered compounds were tested at eight doses in triplicate using the primary BlaM fusion assay and CellTiter Blue cell viability assay.

A total of 47 compounds were confirmed with IC50 <20 μM, and no significant short-term cytotoxicity when present during virus–cell co-culture. These compounds were selected for further characterization. To test whether these compounds specifically target HIV-1 fusion, their effect on fusion of HIV-1 particles pseudotyped with the unrelated VSV G glycoprotein was assessed, which mediates virus entry through acidic endosomes. Out of 47 compounds, 44 were equipotent in reducing the BlaM signal resulting from HIV-1 and VSV pseudovirus fusion (exemplified in Fig. 2A), while three were active only against HIV-1 (e.g., Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Specificity of selected HIV-1 fusion inhibitors. (A) Non-selective inhibition of HIV-1 R3A strain and VSV-G pseudovirus fusion by #2A compound. (B) Selective inhibition of HIV-1 fusion by 4-(2,5-dimethyl-pyrrol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-benzoic acid (DPHB). Cell viability and viral fusion was measured after an overnight incubation at 12°C required for the BlaM substrate cleavage. Viral fusion and cell viability dose–response curves are means ± standard deviations (SD) from triplicate wells in a representative experiment. (○) R3A fusion/viability, (▵) VSV-G fusion/viability. Chemical formulas of #2A and DPHB are shown on the right.

Possible false-positive hits were eliminated by testing whether any of the above 47 compounds interfered with the β-lactamase assay (enzyme activity or substrate retention by cells). Virus–cell fusion experiments were performed, as described above, except that the compounds were added after 90 min of virus–cell incubation at 37°C for 30 min (Supplementary Fig. S1A). It was reasoned that since viral fusion is largely completed at this point,27,31 fusion inhibitors should not significantly diminish the BlaM signal. In contrast to the C52L peptide that blocks gp41 refolding required for fusion, some compounds still robustly inhibited HIV-1 fusion when added at 90 min post infection (Supplementary Fig. S1B). This activity is suggestive of compound interference with the BlaM assay. Another approach to identify false-positive hits was through testing the ability of compounds to inhibit infection using an independent luciferase-based assay (e.g., Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S2D). Finally, long-term TZM-bl cell viability in the presence of 30 μM of inhibitors was measured using an MTS assay and normalized to the DMSO control (as exemplified in Supplementary Fig. S2C). Only non-toxic compounds that blocked both viral fusion and infectivity measured by independent assays were subjected to a more detailed analysis.

All compounds that appeared to inhibit HIV-1 and VSV pseudovirus fusion equally well were eliminated by the above validation procedure. Out of the three compounds that specifically inhibited HIV-1 fusion, one exhibited significant long-term cytotoxicity and another was active only against the dual-tropic R3A HIV-1 Env, which was used in the primary screen (data not shown). Thus, one HIV-specific non-toxic compound remained: 4-(2,5-dimethyl-pyrrol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-benzoic acid (Fig. 2B). This compound, referred to as DPHB, was selected for further functional testing.

DPHB Selectively Inhibits Fusion of X4-Tropic and Dual-Tropic HIV-1

Next, DPHB activity against different HIV-1 strains was tested. The compound inhibited fusion of HXB2 (X4-tropic) and R3A (dual-tropic) pseudoviruses in a dose-dependent manner, but only marginally affected fusion mediated by the CCR5-tropic (R5-tropic) JRFL and BaL26 Env (Fig. 3A). A selective effect on X4- and dual-tropic Env was confirmed using a luciferase-based infectivity assay (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Breadth of inhibition of HIV-1 fusion and infection by DPHB. The dose–response effect of DPHB on fusion (A) and infection (B) of different HIV-1 strains using TZM-bl cells. (C) Inhibition of HIV-1 HXB2 Env-mediated cell–cell fusion by DPHB and the peptide inhibitor C52L (10 μM). HXB2 Env expressing 293-DSP1 and CD4/CXCR4 expressing N4X4-DSP2 cells were used. Results are means ± SD of a representative experiment performed in duplicate (B) or in triplicate (A and C). (○) HXB2 fusion/infection, (▿) BaL26 fusion/infection, (□) JRFL fusion/infection, (⋄) R3A fusion/infection. *P < 0.01 **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.001.

DPHB's ability to inhibit HIV-1 fusion in the absence of other viral components was verified in a cell–cell fusion model. Cell fusion was measured using the dual-split luciferase assay, as described previously.32 Robust luciferase signal resulting from fusion between HXB2 Env-expressing 293T cells and NP2-derived target cells was abrogated in the presence of C52L (Fig. 3C). DPHB inhibited cell–cell fusion mediated by HXB2 Env in a dose-dependent manner, albeit not as efficiently as it inhibited HXB2 pseudovirus fusion with cells (compare Fig. 3A and Fig. 3C). The inhibition of Env-mediated cell–cell fusion shows that DPHB targets Env or cellular receptors, but not the possible upstream steps of virus entry, such as virus endocytosis.

DPHB Promotes Inactivation of HIV-1 Env

First, it was asked if DPHB can irreversibly inhibit cellular processes that are required for HIV-1 entry/fusion. TZM-bl cells were pretreated with the compound, washed, and inoculated with the virus in the absence of inhibitor. This protocol did not lead to significant reduction in HIV-1 fusion activity (data not shown), suggesting that DPHB inhibits HIV-1 fusion by targeting the virus.

Next, it was determined whether DPHB can inactivate cell-free HIV-1 pseudoviruses, using a virucidal assay. Briefly, viruses were adhered to the bottom of poly-L-lysine coated multi-well plates and treated with indicated concentrations of DPHB for 90 min at 37°C (Fig. 4A). Plates were washed, overlaid with TZM-bl cells harvested from a culture dish using a non-enzymatic buffer, and incubated for an additional 90 min at 37°C to allow viral fusion. Control experiments were carried out in the presence of HIV-1 fusion inhibitor C52L during virus/cell co-culture. Whereas mock-treated viruses effectively entered and fused with the overlaid cells, pretreatment with DPHB inactivated the laboratory-adapted X4-tropic HXB2 and the dual-tropic R3A Env in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B). By contrast, particles pseudotyped with the R5-tropic JRFL and BaL26 Envs were more resistant to the compound, as evidenced by the partial inhibition of viral fusion upon pretreatment with a high concentration of DPHB.

Fig. 4.

DPHB selectively inactivates X4- and dual-tropic HIV-1 Env. (A) Illustration of the virucidal assay. (B) Indicated X4-, R5-, and dual-tropic pseudoviruses or VSV-G pseudoviruses were adhered to the bottom of multi-well plates and treated with indicated concentration of DPHB for 90 min at 37°C, after which time viruses were washed, overlaid with TZM-bl cells, and incubated for an additional 90 min at 37°C. Control experiments included C52L or NH4Cl during virus–cell co-incubation to block HIV-1 and VSV-G fusion, respectively. Results are means ± SD from triplicate wells in a representative experiment. *P < 0.01; **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.001.

The inactivating effect of DPHB on HXB2 Env is likely responsible for the greater potency of this compound in the virus–cell fusion compared with cell–cell fusion assay (Fig. 3B and C). Whereas cells continuously express new viral glycoproteins that replace the damaged glycoproteins, viruses that have a fixed number of glycoproteins are readily and irreversibly inactivated upon exposure to the inhibitor.

DPHB Selectively Targets the gp120 V3 Loop of X4/Dual-Tropic Env

To delineate the mechanism by which DPHB inhibits HIV-1 fusion, this compound was applied after reversibly arresting fusion at an intermediate stage at which Env-CD4-co-receptor complexes are allowed to form (TAS26,33,34). TAS is achieved through prolonged incubation of viruses with target cells at a temperature that is just below the effective threshold for HIV-1 fusion (typically 18–23°C; Fig. 5A) but permissive to receptor and co-receptor engagement, as evidenced by resistance of fusion to CD4 and co-receptor binding inhibitors. Elevation of temperature after establishing TAS leads to fast and efficient fusion.26,33,34 The addition of BMS-529 and AMD3100, which inhibit the receptor and CXCR4 binding steps, respectively, at TAS prior to raising the temperature resulted in a partial inhibition of fusion (Fig. 5B), confirming the formation of ternary Env-CD4-co-receptor complexes. The fact that fusion from TAS was partially resistant to DPHB (Fig. 5B) suggests that this compound targets a fusion step upstream of co-receptor binding. The similar extents of fusion inhibition by the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 and DPHB added at TAS indicates that the compound may target the co-receptor binding step of fusion, likely by interacting with the gp120 V3 loop.

Fig. 5.

DPHB targets the gp120 V3 loop of CXCR4-tropic Env. (A) Illustration of the protocol to create a temperature-arrested stage (TAS). CoR, co-receptor. (B) Sensitivity of HXB2 pseudovirus fusion to DPHB and HIV-1 fusion inhibitors added at TAS or present throughout virus–cell pre-incubation/37°C incubation. Results are means ± SD from triplicate wells in a representative experiment. *P < 0.01; **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.001. (C) Fusion of a HXB2-V3BaL chimera is resistant to DPHB. Results are means ± SD from triplicate wells in a representative experiment. (•) HXB2 fusion and (○) HXB2-V3BaL fusion. Results are means ± SD from triplicate wells in a representative experiment. (D) Sequence alignment for the gp120 V3 loop of selected HIV-1 isolates. The net charge of V3 loop is shown on the right. Boxed are the conserved positively and negatively charged residues in X4/dual tropic and in R5-tropic gp120, respectively.

The notion that DPHB can target the V3 loop was examined by comparing its potency against pseudoviruses bearing HXB2 Env and a chimeric Env, in which the HXB2 V3 loop was replaced with that of BaL26 (designated HXB2-V3BaL35). This chimeric Env utilizes CCR5 as co-receptor.35 Whereas DPHB inhibited HXB2 fusion with TZM-bl cells in a dose-dependent manner, it failed to inhibit HXB2-V3BaL fusion (Fig. 5C). Collectively, the above findings imply that DPHB sensitivity maps to the V3 loop of X4-tropic and dual-tropic Env. A salient feature of the V3 loops of X4-tropic Env glycoproteins is the higher net positive charge compared to the V3 loops of CCR5-using Envs36,37 (Fig. 5D). It is thus likely that the carboxylic acid of DPHB preferentially interacts with the highly positive V3 loop of X4- and dual-tropic Env. This interaction appears to induce conformational changes in Env glycoproteins, promoting their inactivation (Fig. 4).

DPHB Degradation Products Are Active Against HIV-1

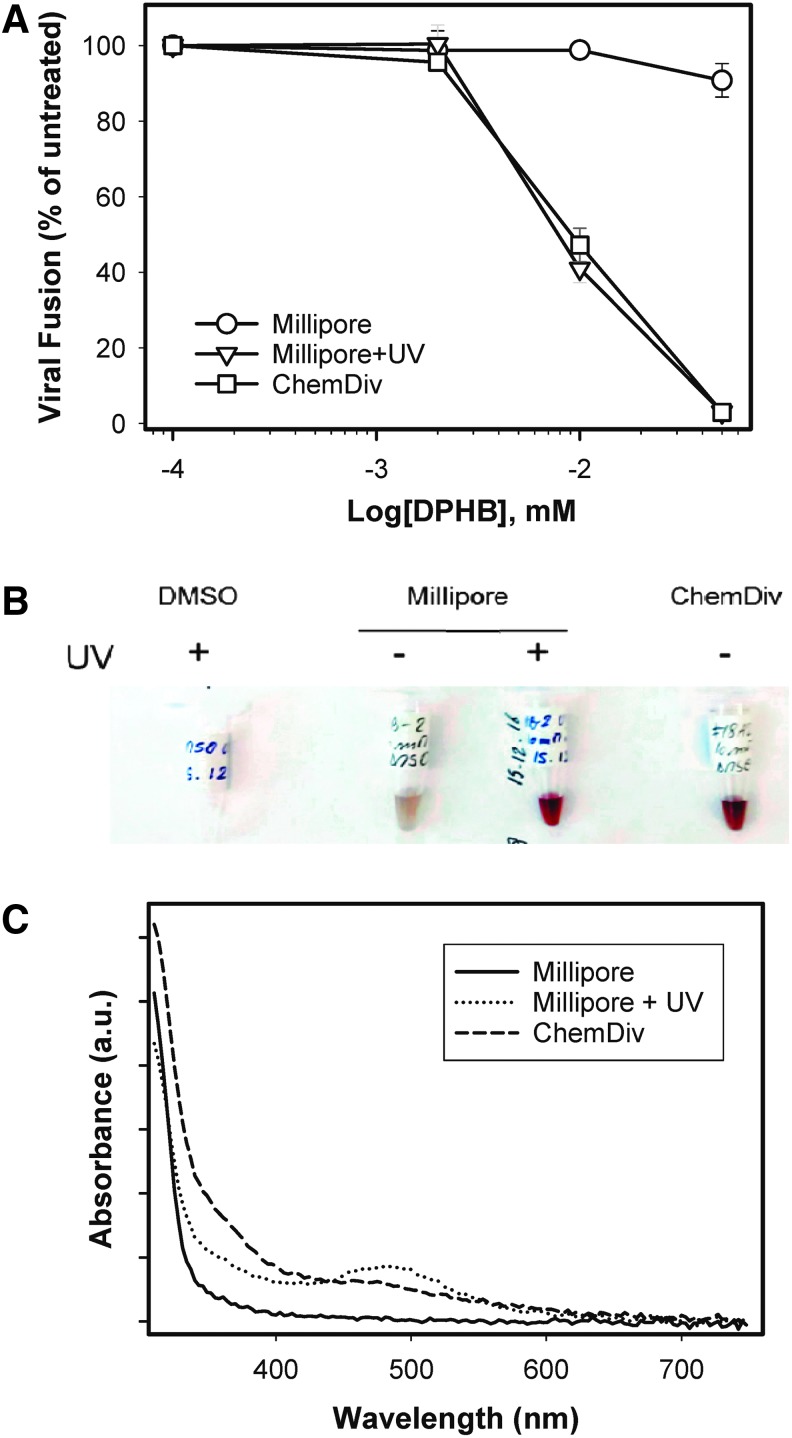

Although reordered DPHB reproducibly inhibited HIV-1 fusion, mass-spectrometry analysis of this compound revealed the presence of major impurities/degradation products (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Deterioration of DPHB was also consistent with the dense brownish color of the compound obtained from ChemDiv (Fig. 6B). A PubChem search revealed that this compound was active in 35/58 screens, suggesting potential promiscuity. The published activities included the inhibition of the HIV-1 gp41 six-helix-bundle formation.15,38 Moreover, a report was found of possible polymerization of a DPHB analog, which appears to form carboxylic acid-containing polymers (Supplementary Fig. S2B) with a broad spectrum of biological activities, such as inhibition of Ephrin receptor.38–40 Since DPHB was reordered from the vendor (ChemDiv) that supplied the 100,000 compound library, this product was purchased from an alternative source. DPHB obtained from Millipore (designated NB-2) was >95% pure, judging by the manufacturer's specification, was only slightly colored, and showed no significant activity against HIV-1 fusion (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

DPHB impurities are responsible for anti-HIV activity. (A) HIV-1 inhibitory activity of DPHB and of a chemically identical compound obtained from Millipore (before and after UV irradiation). Results are means ± SD from triplicate wells in a representative experiment. DPHB from: (○) Millipore, (▿) Millipore + UV irradiation, (□) ChemDiv. *P < 0.01; **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.001. (B) Picture of DMSO and compounds from ChemDiv and Millipore (before and after UV irradiation) dissolved in DMSO. (C) Absorption spectra of the above compounds.

To verify that the DPHB degradation products might be responsible for inhibition of HIV-1 fusion in the assays, the Millipore compound was deliberately exposed to UV light. This treatment greatly intensified the brownish color and altered the absorption spectrum of DPHB to resemble closely the one for the untreated ChemDiv compound (Fig. 6C). Importantly, UV-treated DPHB from Millipore became as active against HIV-1 fusion as the ChemDiv compound (Fig. 6A). Together, these results imply that the anti-HIV-1 activity of DPHB from ChemDiv was due to polymeric complexes present in the sample.

Discussion

The large-scale HTS campaign for HIV-1 fusion inhibitors confirmed the compatibility of the cell-based BlaM assay with HTS. However, care should be exercised to eliminate false-positive hits that interfere with this fluorescence assay. These false-positive hits, which constituted a significant fraction of selected compounds, were eliminated by counter-screening for the ability to inhibit infectivity of pseudoviruses, as measured by a luciferase assay. Additional hit-validation strategies included the measurements of specificity (HIV vs. VSV pseudoviruses) and long-term cytotoxicity. These additional tests yielded only one non-toxic compound that selectively inhibited HIV-1 fusion and infection: DPHB (more correctly, its degradation products).

Functional characterization of DPHB showed that this compound selectively inactivated X4- and dual-tropic Env glycoproteins on contact, in the absence of target cells, whereas R5-tropic Env were much less responsive to this treatment. Swapping the gp120 V3-loops of sensitive and resistant HIV-1 strains allowed mapping the HIV-1 DPHB sensitivity to the V3-loop. Together, these results show that DPHB, most likely by binding to the gp120 V3-loop, induces irreversible conformational changes in sensitive Env glycoproteins leading to their functional inactivation. The data also suggest that the binding site(s) of DPHB overlap, at least partially, with the co-receptor binding sites, since HIV-1 fusion was not sensitive to inhibition once the ternary Env-CD4-co-receptor complexes were formed (Fig. 5B).

The finding that the DPHB degradation products, presumably carboxylic acid-containing polymers,39 are active against HIV-1 fusion is in line with previous reports that this compound also targets HIV-1 gp41.15,38 Polyanions, including dextran sulfates and negatively charged albumin derivatives, exhibit broad antiviral activity against HIV-1 and unrelated viruses (reviewed in Luscher-Mattli41). The structurally related phenyl carboxylic acid polymers also inhibit HIV-1 infection in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.42 Importantly, the anti-HIV activity of polyanions have been linked to their electrostatic interactions with the gp120 V3-loop43 and even with the N-terminal gp41 sequence, referred to as the fusion peptide.44 Due to the lack of HIV-1 inhibitory activity of the pure compound, this lead was not pursued further.

The inability to identify multiple HIV-specific hits from the 100K ChemDiv diversity library in the current screening campaign could be related to a number of reasons, including the lack of chemical space for the desired activities. The nature and complexity of cell-based assay that proceeds through multiple steps could be challenging for the identification of target-specific compounds. With the established HTS protocol and counter-screening assays, screening of additional collections of small-molecule libraries with expanded chemical space will likely produce desired hits that specifically inhibit HIV-1 fusion. These compounds can be developed into valuable probes to study HIV-1 entry and potentially for the use as therapeutic agents.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- BlaM

beta-lactamase

- DPHB

4-(2,5-dimethyl-pyrrol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-benzoic acid

- Env

HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein

- TAS

temperature-arrested stage of fusion

- VSV

vesicular stomatitis virus

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program for cell lines and reagents, Drs. Ray Schinazi and Sébastien Boucle for help with the initial mass-spectrometric characterization of selected hits, and Dr. Arthur Gomtsyan for helpful discussions. The authors are grateful to Min Lu for the C52L peptide, and James Hoxie for the R3A Env expression vector. This work was supported by the NIH R01 grant GM108480 to G.B.M. and Y.D.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Melikyan GB: Membrane fusion mediated by human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein. Curr Top Membr 2011;68:81–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilen CB, Tilton JC, Doms RW: Molecular mechanisms of HIV entry. Adv Exp Med Biol 2012;726:223–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eckert DM, Kim PS: Mechanisms of viral membrane fusion and its inhibition. Annu Rev Biochem 2001;70:777–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markosyan RM, Cohen FS, Melikyan GB: HIV-1 envelope proteins complete their folding into six-helix bundles immediately after fusion pore formation. Mol Biol Cell 2003;14:926–938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tilton JC, Doms RW: Entry inhibitors in the treatment of HIV-1 infection. Antiviral Res 2010;85:91–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Julien JP, Lee PS, Wilson IA: Structural insights into key sites of vulnerability on HIV-1 Env and influenza HA. Immunol Rev 2012;250:180–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin PF, Blair W, Wang T, et al. : A small molecule HIV-1 inhibitor that targets the HIV-1 envelope and inhibits CD4 receptor binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:11013–11018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Si Z, Madani N, Cox JM, et al. : Small-molecule inhibitors of HIV-1 entry block receptor-induced conformational changes in the viral envelope glycoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:5036–5041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strizki JM, Xu S, Wagner NE, et al. : SCH-C (SCH 351125), an orally bioavailable, small molecule antagonist of the chemokine receptor CCR5, is a potent inhibitor of HIV-1 infection in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98:12718–12723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baba M, Nishimura O, Kanzaki N, et al. : A small-molecule, nonpeptide CCR5 antagonist with highly potent and selective anti-HIV-1 activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:5698–5703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorr P, Westby M, Dobbs S, et al. : Maraviroc (UK-427,857), a potent, orally bioavailable, and selective small-molecule inhibitor of chemokine receptor CCR5 with broad-spectrum anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005;49:4721–4732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrer M, Kapoor TM, Strassmaier T, et al. : Selection of gp41-mediated HIV-1 cell entry inhibitors from biased combinatorial libraries of non-natural binding elements. Nat Struct Biol 1999;6:953–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S, Boyer-Chatenet L, Lu H, Jiang S: Rapid and automated fluorescence-linked immunosorbent assay for high-throughput screening of HIV-1 fusion inhibitors targeting gp41. J Biomol Screen 2003;8:685–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu S, Jiang S, Wu Z, et al. : Identification of inhibitors of the HIV-1 gp41 six-helix bundle formation from extracts of Chinese medicinal herbs Prunella vulgaris and Rhizoma cibotte. Life Sci 2002;71:1779–1791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang S, Lu H, Liu S, Zhao Q, He Y, Debnath AK: N-substituted pyrrole derivatives as novel human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry inhibitors that interfere with the gp41 six-helix bundle formation and block virus fusion. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2004;48:4349–4359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai L, Gochin M: A novel fluorescence intensity screening assay identifies new low-molecular-weight inhibitors of the gp41 coiled-coil domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007;51:2388–2395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frey G, Rits-Volloch S, Zhang XQ, Schooley RT, Chen B, Harrison SC: Small molecules that bind the inner core of gp41 and inhibit HIV envelope-mediated fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:13938–13943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu Y, Hixon MS, Dawson PE, Janda KD: Development of a FRET assay for monitoring of HIV gp41 core disruption. J Org Chem 2007;72:6700–6707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katritzky AR, Tala SR, Lu H, et al. : Design, synthesis, and structure-activity relationship of a novel series of 2-aryl 5-(4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidinylidenemethyl)furans as HIV-1 entry inhibitors. J Med Chem 2009;52:7631–7639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang H, Qi Z, Guo A, et al. : ADS-J1 inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry by interacting with the gp41 pocket region and blocking fusion-active gp41 core formation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009;53:4987–4998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray EJ, Leaman DP, Pawa N, et al. : A low-molecular-weight entry inhibitor of both CCR5- and CXCR4-tropic strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 targets a novel site on gp41. J Virol 2010;84:7288–7299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewart KD, Huth JR, Ng TI, et al. : Non-peptide entry inhibitors of HIV-1 that target the gp41 coiled coil pocket. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2010;20:612–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pang W, Wang RR, Gao YD, et al. : A novel enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for screening HIV-1 fusion inhibitors targeting HIV-1 Gp41 core structure. J Biomol Screen 2011;16:221–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herschhorn A, Gu C, Espy N, Richard J, Finzi A, Sodroski JG: A broad HIV-1 inhibitor blocks envelope glycoprotein transitions critical for entry. Nat Chem Biol 2014;10:845–852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marin M, Du Y, Giroud C, et al. : High-throughput HIV-cell fusion assay for discovery of virus entry inhibitors. Assay Drug Dev Technol 2015;13:155–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de la Vega M, Marin M, Kondo N, et al. : Inhibition of HIV-1 endocytosis allows lipid mixing at the plasma membrane, but not complete fusion. Retrovirology 2011;8:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyauchi K, Kim Y, Latinovic O, Morozov V, Melikyan GB: HIV enters cells via endocytosis and dynamin-dependent fusion with endosomes. Cell 2009;137:433–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daecke J, Fackler OT, Dittmar MT, Krausslich HG: Involvement of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry. J Virol 2005;79:1581–1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Padilla-Parra S, Marin M, Gahlaut N, Suter R, Kondo N, Melikyan GB: Fusion of mature HIV-1 particles leads to complete release of a Gag-GFP-based content marker and raises the intraviral pH. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e71002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cavrois M, De Noronha C, Greene WC: A sensitive and specific enzyme-based assay detecting HIV-1 virion fusion in primary T lymphocytes. Nat Biotechnol 2002;20:1151–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyauchi K, Kozlov MM, Melikyan GB: Early steps of HIV-1 fusion define the sensitivity to inhibitory peptides that block 6-helix bundle formation. PLoS Pathog 2009;5:e1000585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kondo N, Marin M, Kim JH, Desai TM, Melikyan GB: Distinct requirements for HIV–cell fusion and HIV-mediated cell–cell fusion. J Biol Chem 2015;290:6558–6573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Demirkhanyan LH, Marin M, Padilla-Parra S, et al. : Multifaceted mechanisms of HIV-1 entry inhibition by human alpha-defensin. J Biol Chem 2012;287:28821–28838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melikyan GB, Markosyan RM, Hemmati H, Delmedico MK, Lambert DM, Cohen FS: Evidence that the transition of HIV-1 gp41 into a six-helix bundle, not the bundle configuration, induces membrane fusion. J Cell Biol 2000;151:413–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biscone MJ, Miamidian JL, Muchiri JM, et al. : Functional impact of HIV coreceptor-binding site mutations. Virology 2006;351:226–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hung CS, Vander Heyden N, Ratner L: Analysis of the critical domain in the V3 loop of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 involved in CCR5 utilization. J Virol 1999;73:8216–8226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopez de Victoria A, Kieslich CA, Rizos AK, Krambovitis E, Morikis D: Clustering of HIV-1 subtypes based on gp120 V3 loop electrostatic properties. BMC Biophys 2012;5:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu K, Lu H, Hou L, et al. : Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of N-carboxyphenylpyrrole derivatives as potent HIV fusion inhibitors targeting gp41. J Med Chem 2008;51:7843–7854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu W, Groh M, Haupenthal J, Hartmann RW: A detective story in drug discovery: elucidation of a screening artifact reveals polymeric carboxylic acids as potent inhibitors of RNA polymerase. Chemistry 2013;19:8397–8400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noberini R, De SK, Zhang Z, et al. : A disalicylic acid-furanyl derivative inhibits ephrin binding to a subset of Eph receptors. Chem Biol Drug Des 2011;78:667–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luscher-Mattli M: Polyanions—a lost chance in the fight against HIV and other virus diseases? Antivir Chem Chemother 2000;11:249–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rando RF, Obara S, Osterling MC, et al. : Critical design features of phenyl carboxylate-containing polymer microbicides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006;50:3081–3089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuipers ME, Huisman JG, Swart PJ, et al. : Mechanism of anti-HIV activity of negatively charged albumins: biomolecular interaction with the HIV-1 envelope protein gp120. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 1996;11:419–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gordon LM, Waring AJ, Curtain CC, et al. : Antivirals that target the amino-terminal domain of HIV type 1 glycoprotein 41. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 1995;11:677–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.