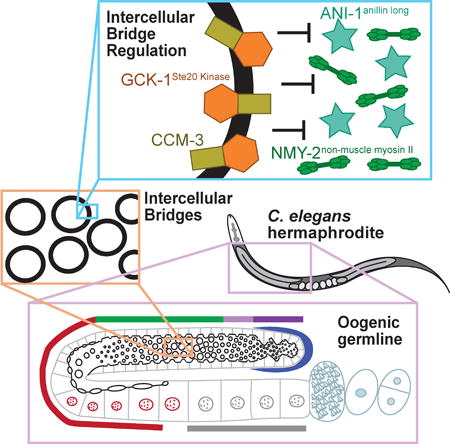

Graphical abstract

eTOC Blurb

Intercellular bridges are proposed to arise from stabilization of a mitotic cytokinetic ring. Rehain-Bell et al. demonstrate that inhibition of non-muscle myosin II is a conserved mechanism of bridge stabilization and find that, in the C. elegans oogenic germline, this is mediated by GCK-1Ste-20 Kinase, its co-factor CCM-3, and anillin proteins.

Summary

Germ cells in most animals are connected by intercellular bridges, actin-based rings that form stable cytoplasmic connections between cells promoting communication and coordination [1]. Moreover, these connections are required for fertility [1,2]. Intercellular bridges are proposed to arise from stabilization of the cytokinetic ring during incomplete cytokinesis [1]. Paradoxically, proteins that promote closure of cytokinetic rings are enriched on stably open intercellular bridges [1,3,4]. Given this inconsistency, the mechanism of intercellular bridge stabilization is unclear. Here, we used the C. elegans germline as a model for identifying molecular mechanisms regulating intercellular bridges. We report that bridges are actually highly dynamic, changing size at precise times during germ cell development. We focused on the regulation of bridge stability by anillins, key regulators of cytokinetic rings and cytoplasmic bridges [1,4–7]. We identified GCK-1, a conserved serine/threonine kinase [8], as a putative novel anillin interactor. GCK-1 works together with CCM-3, a known binding partner [9], to promote intercellular bridge stability and limit localization of both canonical anillin and non-muscle myosin II (NMM II) to intercellular bridges. Additionally, we found that a shorter anillin, known to stabilize bridges [4,7], also regulates NMM II levels at bridges. Consistent with these results, negative regulators of NMM II stabilize intercellular bridges in the Drosophila egg chamber [10,11]. Together with our findings, this suggests that tuning of myosin levels is a conserved mechanism for the stabilization of intercellular bridges that can occur by diverse molecular mechanisms.

Results and Discussion

Intercellular bridges are dynamic throughout meiosis

Each C. elegans oogenic gonad is an elongated U-shaped tube, in which developing germ cells advance spatially from the distal to proximal arm, and simultaneously progress from mitosis, through meiotic prophase I (Figure 1A; Movie S1) [12]. Partially compartmentalized germ cell nuclei line the walls of the gonad and are connected by intercellular bridges (rachis bridges) to the rachis, a central pool of cytoplasm (Figure 1A, B; Movie S1) [12]. Due to these connections, germ cell nuclei are not fully compartmentalized, but we refer to them as cells for simplicity. Unlike organisms such as Drosophila where each intercellular bridge arises from a unique cytokinesis failure [1], the syncytial organization of the C. elegans germline is thought to be achieved by the repeated inheritance of an intercellular bridge generated by one failed cytokinesis early in germline development. This first intercellular bridge is propagated to subsequent germ cells via oriented divisions, analogous to the inheritance of the apical domain during epithelial divisions [13].

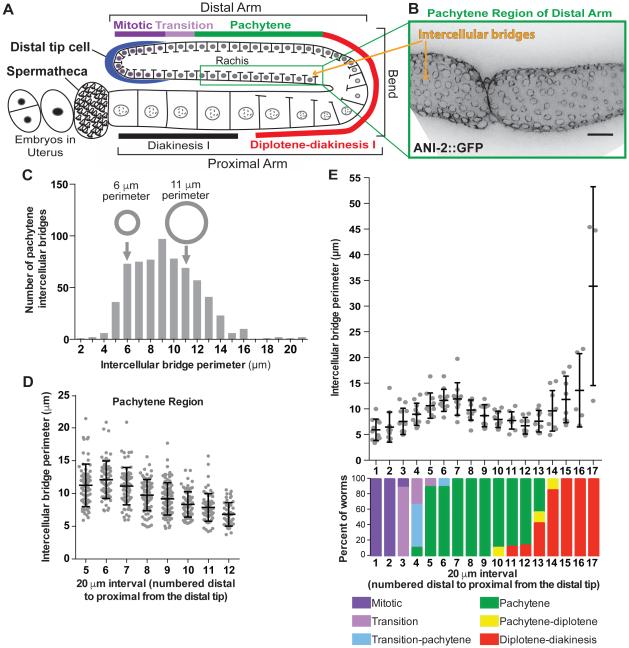

Figure 1. Intercellular bridges in the C. elegans germline are dynamic and regulated across meiotic stages.

(A) Schematic of the C. elegans germline highlighting the linear progression of germ cells from mitosis through the stages of meiotic prophase I as cells move from the distal tip to the proximal gonad arm. Intercellular bridges, depicted as gaps in the cell membranes, connect all nuclei, except the most proximal oocytes, to the shared cytoplasm (rachis).

(B) Representative image (max intensity projection) of intercellular bridges of the distal pachytene region labeled with ANI-2::GFP. Bridges are visualized en face as described in the supplemental methods. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

(C) Histogram of intercellular bridge perimeters from pachytene germ cells (n=657 bridges). Small and large grey circles illustrate the size difference between bridges with 6 and 11 μm perimeters, respectively.

(D) Perimeters of individual intercellular bridges binned into 20 μm sections of gonad length from the distal to proximal end of the pachytene zone. (section 5 n=71 bridges; section 6 n=65; section 7 n=70; section 8 n=78; section 9 n=93; section 10 n=77; section 11 n=68; section 12 n=47).

(E) Average intercellular bridge perimeter found within 20 μm sections starting from the distal tip through the gonad bend (scatter plot; n=11 worms, at least 8 bridges measured per data point). Meiotic stage of cells in 20 μm sections of gonad length from the distal tip through the gonad bend (bar graph: n=11 worms; color coded according to key in figure).

See also Movie S1.

Over half of the germ cells produced in the C. elegans gonad undergo apoptosis before reaching the proximal arm, and act as nurse cells for developing oocytes [14]. Cytoplasm flows out of intercellular bridges of distal nurse cells, and into oocytes in the proximal arm, enlarging them [15]. When oocytes are fully enlarged, bridges close, resulting in cellularization [12,15]. Premature loss of intercellular connections disrupts oogenesis; however, little is known about the molecular mechanisms governing intercellular bridge dynamics (changes in bridge size), and stability (the ability to remain open) [4,7,15,16].

Before addressing the molecular mechanisms regulating bridge dynamics, we defined bridge dynamics. We imaged the large collection of cells simultaneously progressing through oogenesis in intact germlines extruded from adult C. elegans expressing fluorescently-tagged bridge components. We generated maximum intensity projections through half of the gonad to generate en face views of bridges and measured bridge perimeter (supplemental methods; Figure 1B-C). We first quantified bridge size within the pachytene region of the distal arm where cells with open bridges serve as nurse cells. Unexpectedly, bridge size within this region was highly variable (Figure 1B-C). Perimeters ranged from 2-21 μm, with roughly equivalent numbers of bridges with a 6 μm perimeter as bridges almost twice that size (11 μm perimeter; Figure 1C). Since the temporal development of germ cells is arranged spatially along the length of the gonad, we hypothesized that position explains the variability of bridge size. We plotted the perimeter of intercellular bridges in 20 μm sections from the distal to proximal ends of pachytene, and found that bridge size steadily decreased as cells moved through the region (Figure 1B, D). This indicated that not all pachytene intercellular bridges are equivalent, and that while bridges are open throughout pachytene, they are dynamic.

To determine if intercellular bridge size is dynamic throughout oocyte development, we quantified bridge size along the entire gonad length, and normalized the position of bridges to meiotic stage, according to DNA morphology (supplemental methods; Figure 1E) [17]. We plotted the average perimeter of intercellular bridges in 20 μm sections from the distal to proximal end of the gonad (Figure 1E). Bridges were smallest in the mitotic tip and expanded as cells moved through the transition phase into early pachytene, possibly to allow increased cytoplasmic flows out of nurse cells (Figure 1E). Bridges became smaller as cells progressed through pachytene and approached the gonadal bend, where many cells detach from the shared cytoplasm as they undergo apoptosis (Figure 1E). As previously described, bridge size rapidly increased as cells entered diplotene-diakinesis, likely either to facilitate, or as a result of, cytoplasmic flows into these maturing oocytes (Figure 1E) [7]. The observed relationship between changes in bridge size dynamics and meiotic progression indicates that intercellular bridges are differentially regulated with meiotic progression (Figure 1E). To control for differences in regulation between meiotic stages, we focused the remainder of our analysis on the regulation of intercellular bridges during pachytene.

ANI-1 regulates intercellular bridges by limiting ANI-2 localization

To define molecular mechanisms of intercellular bridge dynamics and stability, we studied key regulators from the anillin family of scaffold proteins, which regulate both contractile cytokinetic rings [18] and intercellular bridges [4,7]. We first quantified bridge enrichment of the structurally and functionally distinct C. elegans anillin homologues ANI-1 and ANI-2. ANI-1, like human and Drosophila anillin, bundles F-actin and is predicted by sequence similarity to bind myosin II, septins and membrane lipids [7,19–21]. ANI-2 is an endogenous truncation predicted not to bind actin and myosin II. Interestingly, while both localize to intercellular bridges, they have opposite roles in regulating bridge size and are proposed to be mutually antagonistic [4,7,22]. To test whether changes in bridge size are due to changes in anillin levels, we visualized pachytene bridges en face and measured the density of fluorescently tagged ANI-2 and ANI-1 (average abundance per micron of bridge perimeter; supplemental methods). We then compared the density of anillin to bridge size (Figure 2A-B). Both Spearman’s and Pearson’s correlation analysis revealed a positive relationship between ANI-2 levels and bridge size (Figure 2A), consistent with the observation that ANI-2 depletion causes smaller bridges (Figure S1A) [4,7]. However, we also observed a positive correlation between ANI-1 levels and bridge size (Figure 2B), which was unexpected since ANI-1 depletion increases bridge size (Figure S1B) [4]. Further, the relationships of both ANI-2 and ANI-1 with bridge size were stronger with the Spearman’s correlation analysis compared to Pearson’s, indicating that these relationships are monotonic but not necessarily linear (Figure 2A-B).

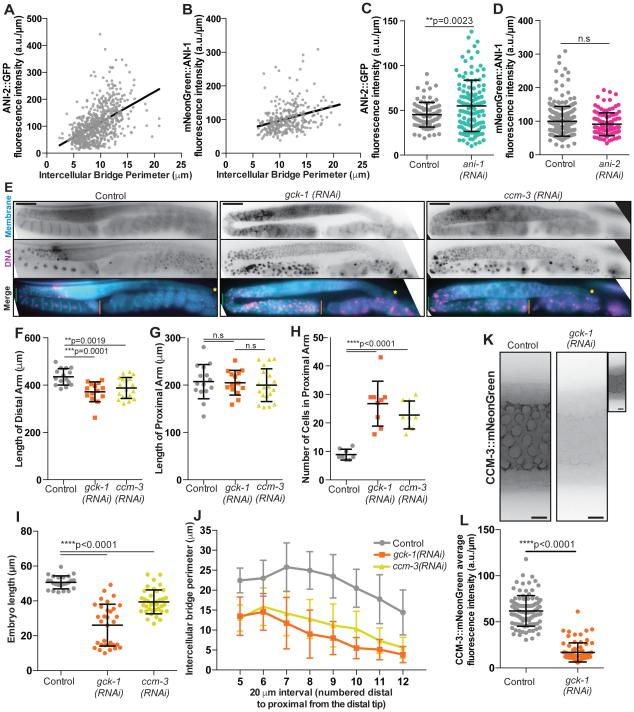

Figure 2. Intercellular bridge regulation by known (ANI-1 and ANI-2) and novel (GCK-1 and CCM-3) players.

(A) Fluorescence intensity per micron of ANI-2::GFP correlated with intercellular bridge perimeter. The relationship between ANI-2::GFP and intercellular bridge perimeter has a Spearman’s correlation co-efficient of 0.5526, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.4954 to 0.6050 and ****p<0.0001; and a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of 0.5054, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.4462 to 0.5603, an R squared of 0.2555 and ****p<0.0001 (n=657 bridges). The black line represents the linear trend of the data and has fits the equation y=(11.28+/−0.7525)x + 2.166+/−7.314 with an R squared value of 0.2555.

(B) Fluorescence intensity per micron of mNeonGreen::ANI-1 correlated with intercellular bridge perimeter. The relationship between mNeonGreen::ANI-1 and intercellular bridge perimeter has a Spearman’s correlation co-efficient of 0.3595, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.2537 to 0.4567 and ****p<0.0001; and a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of 0.3123, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.2066 to 0.4109, an R squared of 0.09755 and ****p<0.0001 (n=301 bridges). The black line represents the linear trend of the data and fits the eqution y=(4.273+/−0.7516)x + 54.26+/−8.841 with an R squared value of 0.09755.

(C) Average fluorescence intensity (a.u./μm) of ANI-2::GFP on intercellular bridges in control (n=89 bridges) and ANI-1 depleted (n=125) germlines. Average fluorescence intensity of ANI-2::GFP was significantly increased in the ani-1(RNAi) condition relative to controls (**p=0.0032).

(D) Average fluorescence intensity (a.u./μm) of mNeonGreen::ANI-1 on intercellular bridges in control (n=258 bridges) and ANI-2 depleted (n=104) germlines. The average fluorescence intensity of mNeonGreen::ANI-1 of bridges in the ani-2(RNAi) condition was not significantly different from controls (p=0.0688).

(E) Representative images (max intensity projections) of intact (in worm) C. elegans germlines in control (n=15 worms), gck-1(RNAi) (n=14), and ccm-3(RNAi) (n=18) treated MDX27 worms. The strain MDX27 expresses GFP::PLCδ-PH to label the plasma-membrane and mCherry::his-58 to mark DNA. In the merged images a green line marks the gonadal bend, while the distal versus proximal ends of the germline are marked by a yellow star and orange line respectively. Scale bars represent 50 μm.

(F) Length of the distal gonad arm (yellow star to green line in Figure 2E merge) in control (n=15 worms), gck-1(RNAi) (n=14), and ccm-3(RNAi) (n=18) treated worms. Distal gonad length was significantly reduced following gck-1(RNAi) (**p=0.0019) and ccm-3(RNAi) (***p=0.0001).

(G) Length of the proximal gonad arm (green line to orange line in Figure 2E merge) in control (n=15 worms), gck-1(RNAi) (n=14), and ccm-3(RNAi) (n=18) treated worms. Proximal gonad length was not significantly changed following gck-1(RNAi) (p=0.8464) or ccm-3(RNAi) (p=0.5403).

(H) The number of cells in the proximal gonad arm in control (n=15 worms), gck-1(RNAi) (n=14), and ccm-3(RNAi) (n=18) depleted worms. The number of cells was significantly increased in the proximal arms of gck-1(RNAi) (****p<0.0001) and ccm-3(RNAi) (****p<0.0001) worms.

(I) Length of embryos produced by control (n=24 worms), gck-1(RNAi) (n=32), and ccm-3(RNAi) (n=38) worms. Embryo length was significantly reduced following gck-1(RNAi) and ccm-3(RNAi) relative to controls (****p<0.0001).

(J) Average perimeter of intercellular bridges binned into 20 μm sections from the distal to proximal end of the pachytene zone in control (n=16 worms), gck-1(RNAi) (n=16), and ccm-3(RNAi) (n=13) worms. Eight or more rings were measured in each 20 μm section.

(K) Representative images of CCM-3::mNeonGreen localization to intercellular bridges in control and gck-1(RNAi) germlines. Scale bars represent 5 μm. Inset image of gck-1(RNAi) is an internally scaled image showing some CCM-3::mNeonGreen still localizes to intercellular bridges likely due to the partial nature of RNAi depletions.

(L) Average fluorescence intensity (a.u./μm) of CCM-3::mNeonGreen on intercellular bridges in control (n=99 bridges) and gck-1(RNAi) (n=76) germlines. Average fluorescence intensity of CCM-3::mNeonGreen was significantly decreased on bridges from gck-1(RNAi) germlines relative to controls (****p<0.0001).

Given the proposed mutual antagonism of ANI-2 and ANI-1, we tested their interdependence. Depletion of ANI-1 significantly increased bridge size (Figure S1B), as reported previously [4], and significantly increased ANI-2 levels at intercellular bridges (Figure 2C). The positive relationship between ANI-2 levels and bridge size was maintained (Figure S1C). In contrast, ANI-2 depletion significantly reduced bridge size (Figure S1A), as expected [4,7], but did not significantly affect ANI-1 density (Figure 2D). Together with previous studies, our findings suggest that bridge size is regulated by modulating ANI-2 levels, and that ANI-1 regulates bridge size by modulating ANI-2. However, the effect of ANI-1 on bridges does not appear to depend on ANI-1 abundance.

Putative ANI-1 interacting protein GCK-1 and its binding partner CCM-3 promote intercellular bridge stability

To further define the molecular mechanism of intercellular bridge regulation via ANI-1, we immunoprecipitated (IPed) ANI-1 and analyzed the co-precipitates by mass-spectrometry to identify novel ANI-1 interacting proteins. We used an ANI-1 specific antibody to IP ANI-1 from three distinct lysates (mixed-stage embryos, mid-stage larvae, and adult worms; supplemental methods) and isolated a large collection (298) of putative ANI-1-associated proteins. Given the apparent role of ANI-1 in the germline, we predicted that some of its partners would be required for germline integrity. Indeed, when we compared our list of 298 putative ANI-1 interacting proteins with the collection of 554 germline regulators [16], we observed 26% (79 proteins) are implicated in the C. elegans germline (only 2.8% of the C. elegans genome encodes known germline regulators). Twenty-seven (out of 79) ANI-1 associated germline regulators were not found in our negative control IP using an antibody directed against glutathione S-transferase (GST) (Table S1). Interestingly, Germinal Center Kinase 1 (GCK-1), a conserved serine-threonine kinase related to budding yeast Ste20 (sterile 20) and the human GCK III sub-family was identified in all three IPs (Table S1) [8].

GCK-1 influences germline structure and function [8,16]. Depletion or mutation of GCK-1 shortened the distal germline arm, decreased the rachis diameter, and reduced the average brood size (Figure 2E-F; Figure 3A-B, D) [8,16]. While depletion of GCK-1 did not affect the length of the proximal gonad, it did result in the accumulation of many unusually small cells in the proximal arm (Figure 2E, G-H) [8,16], and what appeared to be tiny, unfertilized cells in the uterus (Figure S1D black arrow). Further, GCK-1 depletion reduced embryo size (Figure 2I). The effects on germ cell and embryo size suggested that GCK-1 promotes intercellular bridge stability (remaining open), since sustained connection to the rachis is required to achieve full oocyte, and in turn embryo, size [7,15]. To test this idea, we depleted GCK-1 and measured intercellular bridge perimeter and the number of intercellular bridges per 20 μm of pachytene length (supplemental methods). To specifically assess the role of GCK-1 in the maintenance of intercellular bridges, as opposed to bridge formation, we initiated protein depletions only after germlines and intercellular connections were established, in stage 4 larvae. GCK-1 depletion significantly reduced intercellular bridge size and bridge number (Figure 2J; Figure 3A, C, E). Thus, together with published findings [8,16], our results indicate that GCK-1 promotes intercellular bridge stability.

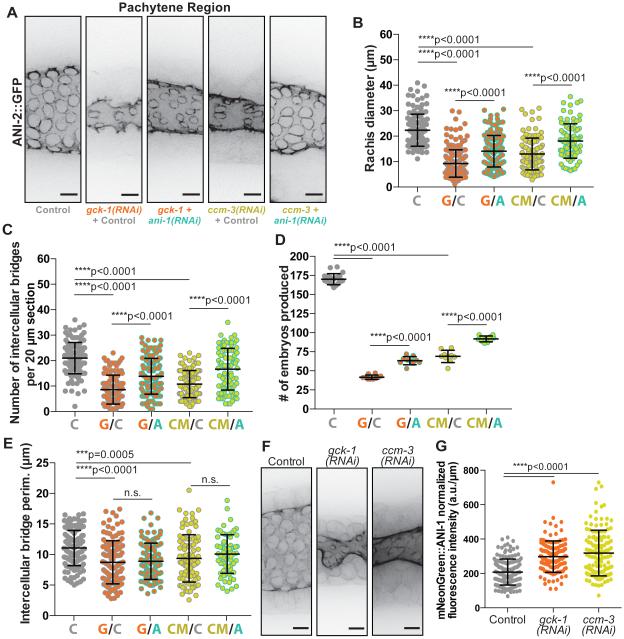

Figure 3. GCK-1 and CCM-3 depletion germline phenotypes are dependent on ANI-1.

(A) Representative images (max intensity projections) of intercellular bridges labeled with ANI-2::GFP in control, “single” depletion (gck-1(RNAi)+control; ccm-3(RNAi)+control), and double depletion (gck-1 + ani-1(RNAi); ccm-3 + ani-1(RNAi)) germlines. In this and the following experiments the control RNAi targets a mCherry tagged plasma membrane probe which is expressed, but non-essential. This control is included in “single” depletions as a standardizing variable to account for the increased number of targets in the +ani-1(RNAi) double depletions. Scale bars represent 5 μm.

(B) Average rachis diameter for 20 μm sections of pachytene in control (n=127 sections), “single” depletion (gck-1(RNAi)+control, G/C, n=126; ccm-3(RNAi)+control, CM/C, n=104), and double depletion (gck-1 + ani-1(RNAi), G/A, n=117; ccm-3 + ani-1(RNAi), CM/A, n=86) germlines. Rachis diameter was significantly reduced in gck-1(RNAi)+control (****p<0.0001) and ccm-3(RNAi)+control (****p<0.0001) worms compared to control worms. Double depletion of either GCK-1 or CCM-3 with ANI-1 (G/A; CM/A) significantly increased rachis diameter relative to “single” depletions (G/C; CM/C respectively) with ****p<0.0001 in both instances.

(C) Number of intercellular bridges per 20 μm section of pachytene length in control (n=126 sections), “single” depletion (gck-1(RNAi)+control, G/C, n=123; ccm-3(RNAi)+control, CM/C, n=104), and double depletion (gck-1 + ani-1(RNAi), G/A, n=129; ccm-3 + ani-1(RNAi), CM/A, n=86) germlines. The number of intercellular bridges was significantly reduced in gck-1(RNAi)+control (****p<0.0001) and ccm-3(RNAi)+control (****p<0.0001) worms compared to control worms. Double depletion of either GCK-1 or CCM-3 with ANI-1 (G/A; CM/A) significantly increased intercellular bridge number relative to “single” depletions (G/C; CM/C respectively) with ****p<0.0001 in both instances.

(D) Number of embryos produced (brood size) per worm in 48 hrs by control (n=20 worms), “single” depletion (gck-1(RNAi)+control, G/C, n=10; ccm-3(RNAi)+control, CM/C, n=9), and double depletion (gck-1 + ani-1(RNAi), G/A, n=10; ccm-3 + ani-1(RNAi), CM/A, n=10) worms. Brood size was significantly reduced in gck-1(RNAi)+control (****p<0.0001) and ccm-3(RNAi)+control (****p<0.0001) worms compared to control worms. Double depletion of either GCK-1 or CCM-3 with ANI-1 (G/A; CM/A) significantly increased brood size relative to “single” depletions (G/C; CM/C respectively) with ****p<0.0001 in both instances.

(E) Average intercellular bridge perimeter for 20μm sections of pachytene in control (n=127 sections), “ single ” depletion (gck-1(RNAi)+control, G/C, n=122; ccm-3(RNAi)+control, CM/C, n=93), and double depletion (gck-1 + ani-1(RNAi), G/A, n=108; ccm-3 + ani-1(RNAi), CM/A, n=70). Bridge size was significantly reduced in gck-1(RNAi)+control (****p<0.0001) and ccm-3(RNAi)+control (***p=0.0005) worms compared to control worms. Double depletion of either GCK-1 or CCM-3 with ANI-1 (G/A; CM/A) had no significant effect on bridge size compared to “single” depletions (G/C; CM/C respectively) in both instances (p=0.6978 and p=0.2074 respectively).

(F) Representative images (max intensity projections) of mNeonGreen::ANI-1 localization to intercellular bridges in control, GCK-1 depleted, and CCM-3 depleted germlines. Scale bars represent 5 μm.

(G) Average fluorescence intensity (a.u./μm) of mNeonGreen::ANI-1 on intercellular bridges in control (n=156 bridges), GCK-1 depleted (n=127), and CCM-3 depleted (n=130) germlines. mNeonGreen::ANI-1 average fluorescence intensity is significantly increased following GCK-1 (****p<0.0001) or CCM-3 (****p<0.0001) depletion relative to controls.

See also Figure S2.

GCK-1 was previously studied in a large-scale high-content screen, which clustered GCK-1 with its well-known binding partner Cerebral Cavernous Malformations 3 (CCM-3; the cluster contained only one other protein, not discussed here) [16]. CCM-3 localizes to intercellular bridges in the C. elegans germline [9]. Like GCK-1, depletion of CCM-3 significantly reduced distal arm length, rachis diameter, and brood size (Figure 2E-F; Figure 3A-B, D). Depletion of CCM-3 also did not significantly affect proximal arm length, but resulted in the accumulation of many small cells in the proximal gonad (Figure 2E, G-H) [16]. Further, depletion of CCM-3 reduced embryo size, intercellular bridge size, and bridge number, indicating that CCM-3, like GCK-1, promotes intercellular bridge stability (Figure 2I-J Figure 3A, C, E). Importantly, neither GCK-1 nor CCM-3 depletion altered the shape of the gonad nor the trend of intercellular bridge size reduction during pachytene (Figure 2E, J). This indicates that neither GCK-1 nor CCM-3 depletion grossly disrupts the developmental timing of germ cells that remain attached to the syncytium.

Vertebrate homologues of GCK-1 form heterodimers with CCM-3 (Cerebral Cavernous Malformations 3) [9,21], and C. elegans GCK-1 and CCM-3 interact in vitro [9]. GCK-1 and CCM-3 localize to intercellular bridges in an interdependent manner and are required for syncytium establishment during development [23]. To determine if GCK-1 and CCM-3 work together to regulate intercellular bridge stability in the fully formed adult germline, we assessed the requirement of GCK-1 for CCM-3 localization to intercellular bridges by depleting GCK-1 only after the germline and intercellular bridges were established. We used CRISPR/Cas9 to add a fluorescent tag to CCM-3 at its carboxyl terminus at the endogenous locus and confirmed CCM-3 localization to intercellular bridges (Figure 2K) [9,24,25]. CCM-3 also localized to sperm, and cytokinetic rings and midbodies in embryos, suggesting a more general role in both intercellular bridges and cytokinetic rings (Figure S1E-G). Depletion of GCK-1 significantly decreased the levels of CCM-3 on bridges, indicating that these proteins act together to regulate bridges (Figure 2K-L).

GCK-1 and CCM-3 promote intercellular bridge stability by regulating ANI-1

Since we identified GCK-1 as a putative ANI-1 interactor, we asked whether the role of GCK-1/CCM-3 in the germline is dependent on ANI-1. Specifically, we co-depleted ANI-1 with either GCK-1 or CCM-3 to test if this rescued the GCK-1/CCM-3 depletion phenotypes. To control for the dilution of the RNAi machinery by the second RNAi target in double depletions, we performed GCK-1 and CCM-3 “single” depletions with a dilution control of dsRNA targeting mCherry, tagging a non-essential membrane probe. We measured ANI-2::GFP labeled bridges and assessed germline structure (rachis diameter, bridge number, and bridge size) and function (brood size) (Figure S2F, Figure 3A-E; Figure S2A-E; supplemental methods). Co-depletion of ANI-1 with GCK-1 or CCM-3 partially rescued the structural and functional germline defects caused by GCK-1/CCM-3 depletion (Figure 3A-D; Figure S2A-D). Both rachis diameter and the number of intercellular bridges increased following ANI-1 co-depletion (G/A, CM/A) relative to “single” depletion of GCK-1 (G/C) or CCM-3 (CM/C) (Figure 3A-C; Figure S2A-C). Moreover, co-depletion of ANI-1 significantly rescued brood size, indicating that the germline phenotypes caused by loss of GCK-1 or CCM-3 are at least partially due to mis-regulation of ANI-1 (Figure 3D; Figure S2D). Indeed, depletion of GCK-1 or CCM-3 caused a significant increase in ANI-1 density on bridges (Figure 3F-G). We hypothesize that the increased density of ANI-1 on intercellular bridges following GCK-1/CCM-3 depletion is partially responsible for the reduced bridge size, as loss of ANI-1 has the opposite effect (Figure S1A; Figure S2E) [4].

Interestingly, ANI-1 co-depletion failed to rescue intercellular bridge size (Figure 3E). We speculate that GCK-1 and CCM-3 depletions cause rapid bridge collapse, such that bridges of intermediate sizes exist very transiently and are not often measured. Thus, our measurement of bridge size following GCK-1/CCM-3 depletion is likely an underestimation. This hypothesis also relates to the two distinct embryo size populations observed following GCK-1 depletion (Figure 2I; Figure S2G): if bridges closed slowly, we would likely observe embryos of intermediate sizes between the two populations. Alternatively, GCK-1 and CCM-1 may regulate bridge size in other ways in addition to limiting ANI-1 at bridges.

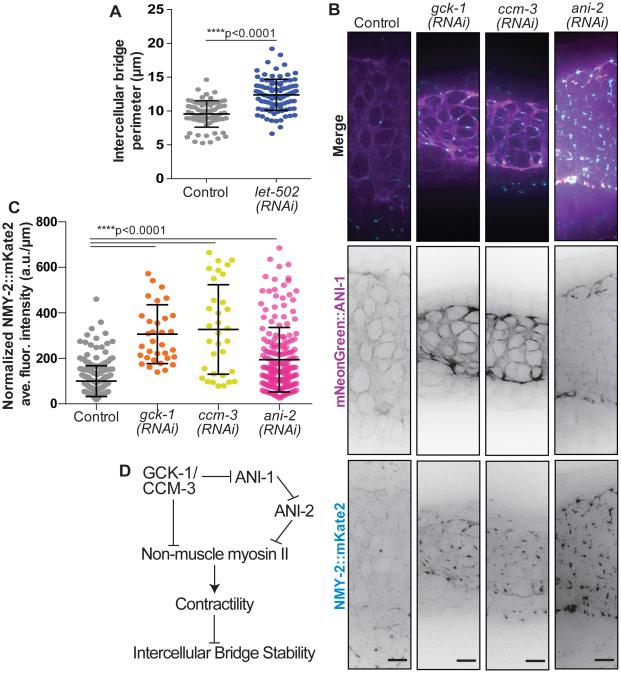

Inhibition of non-muscle myosin II is a conserved mechanism for stabilizing intercellular bridges

Intercellular bridges are thought to arise via the stabilization of cytokinetic rings, in part because while non-muscle myosin II (NMMII) activation is implicated in driving cytokinetic ring constriction [26,27], NMMII negative regulators promote the stabilization of intercellular bridges in Drosophila egg chambers [10,11]. Mutation of DMYPT and protein phosphatase 1β blocks deactivation of NMMII [28] and causes hyper-constriction of intercellular bridges [10,11]. To test whether a similar mechanism functions in the C. elegans germline, we reduced NMMII activity by depleting the NMMII activator, Rho-associated-kinase (ROCK, LET-502 in C. elegans). LET-502 depletion increased intercellular bridge size (Figure 4A). Two NMM II heavy chain isoforms in C. elegans, NMY-1 and NMY-2, differentially regulate intercellular bridge size (Coffman et al., Biophys J, 2016). Specifically, intercellular bridges are larger following NMY-2 depletion (Coffman et al., Biophys J, 2016). Since ANI-1, but not ANI-2, is predicted to bind active NMMII [7,26], we hypothesized that after GCK-1/CCM-3 depletion, excess ANI-1 on intercellular bridges recruits or stabilizes excess NMY-2, promoting contractility and premature bridge closure. To test this possibility, we measured NMY-2 levels at intercellular bridges following depletion of GCK-1 and CCM-3. NMY-2 levels at bridges ~tripled after GCK-1 or CCM-3 depletion (Figure 4B-C). This result was consistent with the idea that increased NMY-2-based contractility reduces bridge size (Figure 4B-C) [10,11]. Like GCK-1 and CCM-3, ANI-2 promotes bridge stability [7]. Depletion of ANI-2 increased NMY-2 localization to intercellular bridges (Figure 4B-C), suggesting that ANI-2 also stabilizes bridges by limiting local NMY-2 enrichment. Interestingly, ANI-1 depletion slightly increased NMY-2 levels indicating that ANI-1 is not required for NMY-2 localization to bridges (Figure S3A). Taken together, these results indicate that several intercellular bridge stability regulators act by limiting actomyosin contractility.

Figure 4. GCK-1, CCM-3, and ANI-2 regulate NMY-2 localization at intercellular bridges.

(A) Intercellular bridge size in control (n=70 bridges) and let-502(RNAi) (n=95) germlines. Intercellular bridge size was significantly increased following LET-502 depletion (****p<0.0001).

(B) Representative images (max intensity projections) of NMY-2::mKate2 and mNeonGreen::ANI-1 localization on intercellular bridges in control, GCK-1 depleted, CCM-3 depleted, and ANI-2 depleted germlines. Scale bars represent 5 μm.

(C) Average fluorescence intensity (a.u./μm) of NMY-2::mKate2 on intercellular bridges in control (n=244 bridges), GCK-1 depleted (n=34), CCM-3 depleted (n=33), and ANI-2 depleted (n=195) germlines. NMY-2::mKate2 fluorescence intensity was significantly increased following depletion of GCK-1 (****p<0.0001), CCM-3 (****p<0.0001), and ANI-2 (****p<0.0001).

(D) Schematic summary of our findings on control of actomyosin contractility and intercellular bridge stability by CCM-3/GCK-1 and anillin family proteins.

See also Figure S3.

In sum, we propose that GCK-1, CCM-3 and ANI-2 regulate bridge stability by regulating NMY-2 at intercellular bridges (Figure 4D). We speculate that increased NMY-2 destabilizes bridges because contractility promotes bridge closure (Figure 4D). ANI-2 may limit NMY-2 due its predicted lack of a NMY-2 binding site. Indeed, it has been suggested that ANI-2 negatively regulates actomyosin contractility in the C. elegans zygote [22]. Unlike ANI-2 depletion, depletion of GCK-1 and CCM-3 increased ANI-1 localization (Figure 3F-G). Since ANI-1 contains an NMY-2 binding site, excess ANI-1 at intercellular bridges may recruit or stabilize NMY-2. Alternatively, vertebrate homologues of GCK-1 and CCM-3 inhibit RhoA [29–31]. Thus, GCK-1 and CCM-3 may limit NMY-2 and ANI-1 via inhibiting RhoA and in turn the NMY-2 activator ROCK [31] (Figure 4A) [32,33]. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that depletion of ROCK significantly increased bridge size, indicating that activation of NMY-2 (i.e. actomyosin contractility) drives bridges closed (Figure 4A, D).

Our results have identified new connections between established and novel intercellular bridge regulators, as well as connections between these regulators and the contractile cytoskeleton. Future work will aim to uncover the precise molecular mechanisms governing intercellular bridge stability and actomyosin contractility.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

C. elegans germline intercellular bridges are dynamic throughout meiotic prophase

GCK-1Ste-20 Kinase and its cofactor CCM-3 promote intercellular bridge stability

GCK-1 and CCM-3 limit ANI-1anillin long localization to intercellular bridges

GCK-1, CCM-3 and ANI-2anillin short limit myosin II localization to bridges

Acknowledgements

We thank Iain Cheeseman for assistance with IPs, Dan Dickinson for assistance with CRISPR/Cas9, and the Goldstein and Labbe labs for strains. We thank Jean-Claude Labbe, Mark Peifer, and Bob Goldstein for thoughtful comments on this manuscript. We thank all members of the Maddox labs, especially Paul Maddox, for helpful discussion and shared reagents and instrumentation. This work was supported by GM102390 from the NIH and 1616661 from the NSF to ASM.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

ASM supervised the project, performed the ANI-1 IPs and was one of the primary writers. KR-B led the project, performed most of the experiments, and was one of the primary writers. AL performed some of the measurements and data analysis. MEW generated CRISPR strains, helped prepare the manuscript, and generated Movie S1. IM and JRYIII performed the mass spec analysis.

References

- 1.Haglund K, Nezis IP, Stenmark H. Structure and functions of stable intercellular bridges formed by incomplete cytokinesis during development. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2011;4:1–9. doi: 10.4161/cib.4.1.13550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lei L, Spradling AC. Mouse oocytes differentiate through organelle enrichment from sister cyst germ cells. Science. 2016;352:87–95. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou K, Rolls MM, Hanna-Rose W. A postmitotic function and distinct localization mechanism for centralspindlin at a stable intercellular bridge. Dev. Biol. 2013;376:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amini R, Goupil E, Labella S, Zetka M, Maddox AS, Labbé JC, Chartier NT. C. elegans Anillin proteins regulate intercellular bridge stability and germline syncytial organization. J. Cell. Biol. 2014;206:129–43. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201310117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eikenes ÅH, Brech A, Stenmark H, Haglund K. Spatiotemporal control of Cindr at ring canals during incomplete cytokinesis in the Drosophila male germline. Dev. Biol. 2013;377:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haglund K, Nezis IP, Lemus D, Grabbe C, Wesche J, Liestøl K, Dikic I, Palmer R, Stenmark H. Cindr Interacts with Anillin to Control Cytokinesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:944–950. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maddox AS, Habermann B, Desai A, Oegema K. Distinct roles for two C. elegans anillins in the gonad and early embryo. Development. 2005;132:2837–48. doi: 10.1242/dev.01828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schouest KR, Kurasawa Y, Furuta T, Hisamoto N, Matsumoto K, Schumacher JM. The germinal center kinase GCK-1 is a negative regulator of MAP kinase activation and apoptosis in the C. elegans germline. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lant B, Yu B, Goudreault M, Holmyard D, Knight JDR, Xu P, Zhao L, Chin K, Wallace E, Zhen M, et al. CCM-3/STRIPAK promotes seamless tube extension through endocytic recycling. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6449. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ong S, Foote C, Tan C. Mutations of DMYPT cause over constriction of contractile rings and ring canals during Drosophila germline cyst formation. Dev. Biol. 2010;346:161–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamoto S, Bayat V, Bellen HJ, Tan C. Protein phosphatase 1ß limits ring canal constriction during Drosophila germline cyst formation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hubbard EJ, Greenstein D. The Caenorhabditis elegans gonad: a test tube for cell and developmental biology. Dev. Dyn. 2000;218:2–22. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200005)218:1<2::AID-DVDY2>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swiatek P, Kubrakiewicz J, Klag J. Formation of germ-line cysts with a central cytoplasmic core is accompanied by specific orientation of mitotic spindles and partitioning of existing intercellular bridges. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;337:137–48. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0788-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gumienny TL, Lambie E, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR, Hengartner MO. Genetic control of programmed cell death in the Caenorhabditis elegans hermaphrodite germline. Development. 1999;126:1011–22. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.5.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolke U, Jezuit EA, Priess JR. Actin-dependent cytoplasmic streaming in C. elegans oogenesis. Development. 2007;134:2227–36. doi: 10.1242/dev.004952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green RA, Kao HL, Audhya A, Arur S, Mayers JR, Fridolfsson HN, Schulman M, Schloissnig S, Niessen S, Laband K, et al. A high-resolution C. elegans essential gene network based on phenotypic profiling of a complex tissue. Cell. 2011;145:470–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hillers KJ, Jantsch V, Martinez-Perez E, Yanowitz JL. Meiosis. Wormbook. 2015:1–54. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.178.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piekny AJ, Maddox AS. The myriad roles of Anillin during cytokinesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010;21:881–91. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorn JF, Zhang L, Paradis V, Edoh-Bedi D, Jusu S, Maddox PS, Maddox AS. Actomyosin tube formation in polar body cytokinesis requires Anillin in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:2046–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun L, Guan R, Lee IJ, Liu Y, Chen M, Wang J, Wu JQ, Chen Z. Mechanistic Insights into the Anchorage of the Contractile Ring by Anillin and Mid1. Dev. Cell. 2015;33:413–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu J, Fairn GD, Ceccarelli DF, Sicheri F, Wilde A. Cleavage Furrow Organization Requires PIP2-Mediated Recruitment of Anillin. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:64–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chartier NT, Salazar Ospina DP, Benkemoun L, Mayer M, Grill SW, Maddox AS, Labbé JC. PAR-4/LKB1 mobilizes nonmuscle myosin through anillin to regulate C. elegans embryonic polarization and cytokinesis. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:259–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pal S, Lant B, Yu B, Tian R, Tong J, Krieger JR, Moran MF, Gingras A-C, Derry WB. CCM-3 promotes C. elegans germline development by regulating vesicle trafficking cytokinesis and polarity. Curr Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.02.028. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dickinson DJ, Ward JD, Reiner DJ, Goldstein B. Engineering the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using Cas9-triggered homologous recombination. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:1028–34. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dickinson DJ, Pani AM, Heppert JK, Higgins CD, Goldstein B. Streamlined Genome Engineering with a Self-Excising Drug Selection Cassette. Genetics. 2015;200:1035–49. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.178335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo S, Kemphues KJ. A non-muscle myosin required for embryonic polarity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1996;382:455–8. doi: 10.1038/382455a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green RA, Paluch E, Oegema K. Cytokinesis in animal cells. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012;28:29–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grassie ME, Moffat LD, Walsh MP, MacDonald JA. The myosin phosphatase targeting protein (MYPT) family: A regulated mechanism for achieving substrate specificity of the catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase type 1δ. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011;510:147–59. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coffman VC, Kachur TM, Pilgrim DB, Dawes AT. Antagonistic behaviors of NMY-1 and NMY-2 maintain ring channels in the C. elegans gonad. Biophys. J. 2016;111:2202–2213. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.10.011. [Pubmed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Louvi A, Nishimura S, Günel M. Ccm3, a gene associated with cerebral cavernous malformations, is required for neuronal migration. Development. 2014;141:1404–15. doi: 10.1242/dev.093526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jordan SN, Canman JC. Rho GTPases in animal cell cytokinesis: an occupation by the one percent. Cytoskeleton. 2012;69:919–30. doi: 10.1002/cm.21071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hickson GRX, O’Farrell PH. Rho-dependent control of anillin behavior during cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 2008;180:285–94. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piekny AJ, Glotzer M. Anillin is a scaffold protein that links RhoA, actin, and myosin during cytokinesis. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:30–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.