Abstract

Background & Aims

Foodborne illness affects 15% of the United States population each year and is a risk factor for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). We evaluated risk of, risk factors for, and outcomes of IBS after infectious enteritis

Methods

We performed a systematic review of electronic databases from 1994 through August 31, 2015 to identify cohort studies of the prevalence of IBS 3 months or more after infectious enteritis. We used random effects meta-analysis to calculate the summary point prevalence of IBS after infectious enteritis, as well as relative risk (compared to individuals without infectious enteritis) and host- and enteritis-related risk factors.

Results

We identified 45 studies, comprising 21,421 individuals with enteritis, followed for 3 months–10 years for development of IBS. The pooled prevalence of IBS at 12 months after infectious enteritis was 10.1% (95% CI, 7.2–14.1) and at more than 12 months after infectious enteritis was 14.5% (95% CI, 7.7–25.5). Risk of IBS was 4.2-fold higher in patients who had infectious enteritis in the past 12 months than in individuals in those who had not (95% CI, 3.1–5.7); risk of IBS was 2.3-fold higher in individuals who had infectious enteritis longer than 12 months ago than in individuals who had not (95% CI, 1.8–3.0). Of patients with enteritis caused by protozoa or parasites, 41.9% developed IBS; of patients with enteritis caused bacterial infection, 13.8% developed IBS. Risk of IBS was significantly increased in women (odds ratio [OR], 2.2; 95% CI, 1.6–3.1) and with antibiotic exposure (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.2–2.4), anxiety (OR, 2; 95% CI, 1.3–2.9), depression (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2–1.9), somatization (OR, 4.1; 95% CI, 2.7–6.0), neuroticism (OR, 3.3; 95% CI, 1.6–6.5), and clinical indicators of enteritis severity. There was a considerable level of heterogeneity among studies.

Conclusion

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, we found more than 10% of patients with infectious enteritis to later develop IBS; risk of IBS was 4-fold higher than in individuals who did not have infectious enteritis, although there was heterogeneity among studies analyzed. Women—particularly those with severe enteritis—are at increased risk for developing IBS, as are individuals with psychological distress and users of antibiotics during the enteritis.

Keywords: Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome, gastrointestinal infections, functional gastrointestinal disorders, microbes

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) affects 7–18% of the population worldwide.1 Infectious enteritis (IE) is a commonly identified risk factor for development of IBS2; this subset is referred to as post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS). Since one of the original descriptions by Chaudhary and Truelove in 1960,3 our understanding of PI-IBS was limited until the late 1990s, when the prevalence and risk factors for PI-IBS were investigated.4, 5 Bacterial (Campylobacter jejuni, Salmonella enterica, Shigella sonnei, Escherichia coli O157:H7),6 viral (Norovirus)7–10 and protozoal (Giardia lamblia)11–13 enteritis have all been associated with the development of PI-IBS. A wide range from 4–36% is reported to develop PI-IBS and long-term follow up studies have shown that the IBS symptoms can persist for ≥10 years following the IE episode.14, 15 The PI-IBS risk associated with IE has been shown to be independent of other potential risk factors.16, 17 Foodborne IE affects 1 in 6 individuals in the U.S. (48 million people) annually placing a significant population at-risk for development of PI-IBS.18 Additionally, travelers’ diarrhea can also add significantly to the burden of PI-IBS.19

The reported PI-IBS prevalence depends upon the pathogen(s) involved, geographic location, clinically suspected or laboratory proven enteritis, time of assessment following the IE, and the criteria used to define IBS.2 The IE outbreak in Walkerton, Ontario affected >2000 residents and resulted in 36% of that population developing PI-IBS at 2 years post-infection.20, 21 Younger age, female gender, bloody stools, abdominal cramps, weight loss, and prolonged diarrhea during IE were independent risk factors for PI-IBS.20, 22 However, other studies have reported a much lower prevalence of PI-IBS and have not confirmed the same risk factors to be associated with the development of PI-IBS.23 Previous meta-analyses (most recent published in 2007) concluded that IE increases the risk of PI-IBS. However, it included few studies, with limited assessment of time-dependent point prevalence and relative risk of PI-IBS (compared to non-exposed controls), and could not comprehensively study host- and enteritis-related risk factors associated with PI-IBS development.6 Additionally, pathogen-specific risk and natural history of PI-IBS were not reported. With increased recognition of PI-IBS, there have been several epidemiological studies since the previous meta-analysis.

Hence, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies evaluating the association between IE and PI-IBS, evaluating the time- and pathogen-specific point prevalence, relative risk, host- (sex, psychological distress, and smoking) and enteritis- (abdominal pain, antibiotic use, bloody stool, diarrhea duration >7 days, fever and weight loss) related risk factors and outcomes of PI-IBS.

METHODS

This systematic review was conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The process followed a priori established protocol (PROSPERO # CRD42016035317).

Selection Criteria

We included cohort studies with documented IE, reporting the prevalence of PI-IBS on at least one-time point ≥3 months following the IE. The IE episode was either laboratory proven or clinically suspected with presence of at least 2 of the following 3 symptoms: pain, fever and diarrhea or self-reported by the patient as “acute onset” of symptoms convincing of IE. The diagnosis of IBS was based on established criteria (Rome I, II or III) or ICD codes. We excluded (a) case-control studies (those examining IBS cases and controls and determining past IE exposure), (b) cross-sectional studies, case series and case reports, and (c) studies with insufficient data to estimate prevalence.

Data Sources and Search Strategy

We identified studies from a well-conducted prior meta-analysis on the prevalence of PI-IBS published in 20076 (AMSTAR rating24, 10/11), that used criteria similar to the current study. In addition, we searched multiple electronic databases for cohort studies of PI-IBS, from 2006-August 31, 2015, with the help of a medical librarian. The databases included Ovid Medline, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (detailed search strategy available in Appendix Protocol). Briefly, search items used included “Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome”; “PI-IBS”; “Irritable bowel syndrome” OR “IBS” OR “Functional GI disorder” AND “Gastroenteritis” OR “Viral Gastroenteritis” OR “Giardia Gastroenteritis” OR “Giardiasis” OR “Norovirus” OR “Campylobacter jejuni” OR “Salmonella” OR “Salmonellosis” OR “Shigella” OR “Shigellosis”. Two investigators (FK and AW) independently reviewed the title and abstracts of all studies to exclude studies that did not address the research question of interest, based on pre-specified criteria. Subsequently, they independently reviewed the full texts of the remaining articles to determine whether they met inclusion criteria and contained relevant information. Conflicts in study selection at this stage were resolved by consensus, referring back to the original article in consultation with the senior investigator (MG). Reference lists from included original articles and recent reviews on PI-IBS were hand searched to identify any additional studies. Proceedings of major gastroenterology conferences from 2012–15 were reviewed for relevant abstracts. In case of missing data, corresponding authors of included studies were contacted electronically on two occasions with request for missing data.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data extraction was performed independently by two investigators (FK and AW) using a standardized data extraction form. The variables abstracted included: author, year, geographic location, number of subjects in IE exposed group and control group (when available), accrual characteristics (inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, study methods, case and control cohort identification), pathogen involved, time-point (s) studied following IE and the definition used for PI-IBS assessment. Additionally, we extracted host- and enteritis-related risk factors associated with development of PI-IBS. Host-related risk factors included: age, sex, smoking status, and psychological distress at time of IE; and IE-related factors included: abdominal pain, fever, duration of diarrhea, bloody stools, weight loss, and antibiotic use.

Quality assessment of the selected studies was assessed by two authors independently (FK and AW) using the modified Newcastle-Ottawa scale25 (rated on a 0–6 scale for studies without a comparator group and 0–9 for studies with a comparator group) for cohort studies; within this, studies with scores 5 or 6 (out of 6, for point prevalence studies) and 8 or 9 (out of 9, for comparative studies on risk in exposed vs. non-exposed cohorts) were considered high quality, studies with scores 4/6 or 6 or 7 out of 9, were considered medium quality, and all other studies were considered low quality. The inter rater agreement between the two reviewers (FK and AW) for the questions on the Newcastle-Ottawa scale was 80%. The discrepant items were resolved by senior investigator (MG) independently reviewing the original study for that specific variable on the scale.

Outcomes Assessed

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of interest was the point prevalence of PI-IBS. This was estimated within 12m (overall, and at 3m, 6m and 12m) and >12m (overall, and at 13–59m, ≥60m) after IE, by type of pathogen (bacterial, viral and protozoal/parasitic). When studies reported prevalence of PI-IBS at multiple time points, then a hierarchal assessment of prevalence at 12m, 13–59m, ≥60m, 6m and 3m was used to estimate “overall” point prevalence. Since gastrointestinal symptoms, and consequently the diagnosis of IBS based on symptom criteria can vary over time, we chose point prevalence of PI-IBS at different time points as more accurate representation, as compared to incidence or cumulative incidence of PI-IBS after IE.

Secondary outcomes

Relative risk of PI-IBS: To estimate the relative impact of IE on risk of IBS, we compared rates of new-onset IBS after IE with non-exposed individuals, overall, and within 12m and >12m after exposure (to compare time-specific risk). This was assessed separately by type of pathogen (bacterial, viral and protozoal/parasitic);

Risk factors for PI-IBS: We performed meta-analysis of demographic (age, sex, smoking), psychosocial (anxiety, depression at time of IE, measured using Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS], somatization, and neuroticism) and enteritis-related risk factors (duration of IE, bloody stools, abdominal pain, fever, weight loss, antibiotic exposure) comparing individuals who developed PI-IBS after IE with those who did not;

Natural history and PI-IBS phenotype: Using studies which reported prevalence and outcome of PI-IBS at multiple time-points after IE, we assessed the natural history and prognosis of PI-IBS. Additionally, we reviewed the IBS subtype [constipation predominant IBS (IBS-C), diarrhea predominant IBS (IBS-D) and mixed IBS (IBS-M)] when it was reported.

To assess robustness of association between IE and PI-IBS, and to identify potential sources of heterogeneity, we conducted a priori subgroup analyses based on: geographic location (North America vs. Europe vs. Asia), method of assessing IE (laboratory confirmed vs. clinically suspected), definition of IBS (Rome I vs. II vs. III), patient population (adults vs. children), attrition rate (survey response rates: ≥80%, 60–79%, 40–59% and <40%) and study quality (high vs. medium vs. low). Sensitivity analysis based on type of publication (full-text vs. abstract) was also performed.

Statistical Analysis

We used the random-effects model described by DerSimonian and Laird to calculate summary point prevalence and 95% confidence interval (CI).26 Rates of PI-IBS in patients exposed to IE were compared with non-exposed individuals to estimate summary relative risk (RR) and 95% CI. To identify risk factors associated with PI-IBS, we pooled maximally adjusted odds ratio (OR; to account for confounding variables), where reported, using random-effects model. To estimate what proportion of total variation across studies was due to heterogeneity rather than chance, I2 statistic was calculated. In this, a value of <30%, 30%–59%, 60%–75% and >75% were suggestive of low, moderate, substantial and considerable heterogeneity, respectively.27 Once heterogeneity was noted, between-study sources of heterogeneity were investigated using a priori defined subgroup analyses by stratifying original estimates according to study characteristics (as described above). In this analysis, a p-value for differences between subgroups (Pinteraction) of <0.10 was considered statistically significant, i.e., significant differences in summary estimates (either point prevalence of PI-IBS or relative risk of PI-IBS) were observed in different subgroup categories. Publication bias for PI-IBS prevalence and RR was assessed qualitatively using funnel plot, and quantitatively, using Egger’s test.28

All p values were two tailed. For all tests (except for heterogeneity), a probability level <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All calculations and graphs were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) version 2 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ).

RESULTS

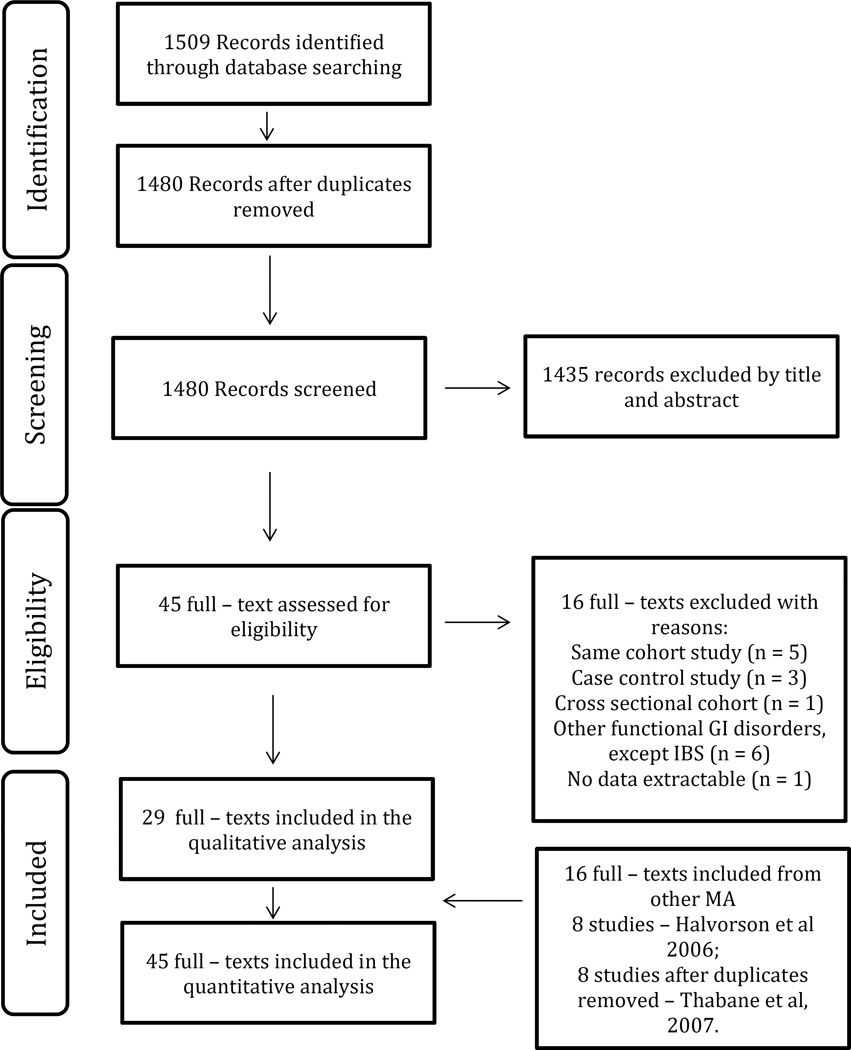

From the previous systematic review, 16 studies were identified reporting prevalence of PI-IBS. With our updated systematic literature review, we identified an additional 29 unique articles meeting inclusion criteria. Therefore, we included 45 studies (n=21,421 participants with IE exposure) that reported the prevalence of PI-IBS.4, 5, 7–13, 15–17, 20, 23, 29– 59 The flow diagram summarizing study identification and selection is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study selection flow-diagram

Characteristics and Quality of Included Studies

Appendix Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the studies, and of the participants in the individual studies. Thirty five and 15 studies provided sufficient data for estimation of prevalence of PI-IBS within 12m and >12m of IE, respectively. The number of subjects examined in the individual studies in the IE exposed group ranged from 23–5894, and 1.2–80.5% of those developed PI-IBS. Four studies were in pediatric (<18y) population. The follow-up time period for assessment of PI-IBS ranged from 3m to 10y. Thirty seven studies used Rome criteria for diagnosing PI-IBS (12 Rome III, 17 Rome II, and 8 Rome I). Ten studies were conducted in North America, 26 in Europe, 6 in Asia, 1 in New Zealand 1 study was conducted in both Europe and North America and 1 in Israel. The mean age of participants in IE exposed group ranged from 5.3–65.4 years with 0.5–67.2% females. Bacterial enteritis was the most common IE type studied. IE was laboratory confirmed in 24 studies and clinically suspected in 21 studies. Appendix Table 2 outlines cohort characteristics (inclusion and exclusion criteria), methodology for PI-IBS assessment (presence of IBS prior to IE, survey response rates, and data completeness) and selection of controls. Out of the 45 studies, 41 studies used online or mailed survey questionnaires or in person or telephone interviews and 4 studies were conducted using electronic databases. Of the ones using databases, two used ICD codes alone,7, 33 one used ICD codes plus clinician documentation17 and one used ICD codes plus IBS confirmation by a physician.16 The survey response rate was variable (36–96%). Exclusion of pre enteritis IBS was specified in 35 of 45 studies and IBD in 26 of the 45 studies. Additionally, one study excluded IE episodes within 12 m before the current IE episode33 and one excluded patients with another IE episode anytime in the past.16

The median quality score for prevalence studies included was 5 (range 3–6) on a 0–6 scale and 7 (range 4–9) for RR studies on a 0–9 scale (Appendix Table 3). There was variability in the survey response rate among the studies (<40% to ≥80% response); 16/45 studies had ≥80% response rate.

Prevalence of PI-IBS

Overall, pooled prevalence of PI-IBS was 11.5% (2217/21421, 95% CI=8.2–15.8), with no significant difference in the reported PI-IBS prevalence among studies estimating prevalence at 3, 6, 12, 13–59 or ≥60 months following IE (Pinteraction=0.63) (Appendix Table 4). At 12m and beyond 12m, the point prevalence of PI-IBS was 10.1% (911/15800, 95% CI=7.2–14.1) and 14.5% (1466/12007, 95% CI=7.7–25.5), respectively. Summary estimate shows significant heterogeneity (I2 ≥90%) among studies.

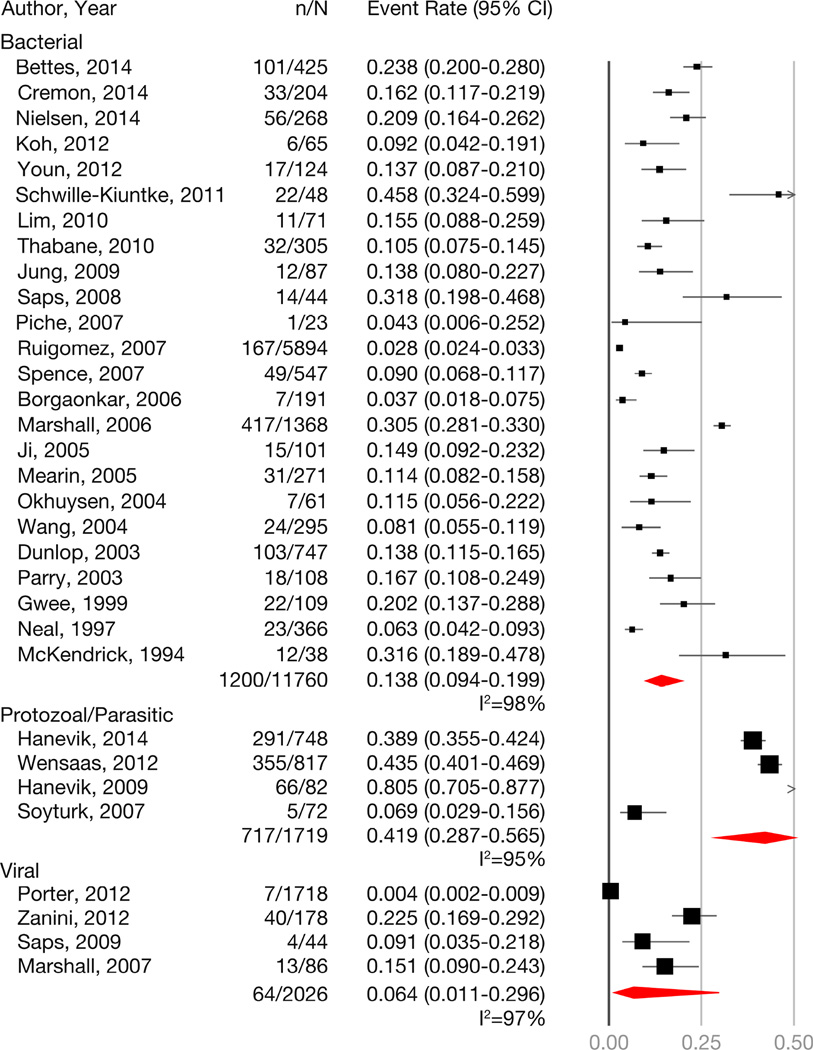

Overall, the rates of PI-IBS were highest after protozoal/parasitic IE,11–13, 46 followed by bacterial IE,4, 5, 17, 20,15, 31, 34, 35, 38–44, 47, 50–55, 57, 58 and lowest rates were seen with viral IE7–10 (Figure 2). Summary estimate shows significant heterogeneity (I2 ≥95%) among studies. However, when examining rates within and beyond 12m, viral IE was associated with high rates PI-IBS within 12m of IE (prevalence=19.4; 95% CI, 13.2–27.7), but this declined beyond 12m of exposure (prevalence=4.4; 95% CI, 0.3–39.9) (Appendix Table 5). Four studies evaluating pediatric age patients found a PI-IBS prevalence of 14.7% (95% CI=7.3–27.2; I2=79) compared to 11.1% (95% CI=7.8–15.6; I2=98) in 41 adult studies (Pinteraction=0.48). Given the significant heterogeneity, summary estimates should be used with caution.

Figure 2.

Summary point prevalence of PI-IBS with bacterial, protozoal/parasitic and viral infectious enteritis. Considerable heterogeneity (I2>95%) was observed for all analyses.

Considerable heterogeneity is observed in the reported prevalence of PI-IBS. To understand the variability in prevalence, several pre-specified subgroup analyses were performed (Table 1). We observed significantly higher prevalence of PI-IBS (18.6%; 95% CI, 13.7–24.8) in studies with low response rates (particularly, <40% response), suggesting a responder bias; in studies in which response rates was ≥80%, overall prevalence of PI-IBS was 7.9% (95% CI, 4.1–14.6). We did not observe significant difference in reported prevalence of PI-IBS in patients with laboratory confirmed IE (prevalence, 12.9%; 95% CI, 8.6–19.1) as compared to clinically suspected IE or self-reported (prevalence, 9.9; 95% CI, 6.0–16.1), based on criteria to define IBS (Rome I, II or III) or geographical location of study. On sensitivity analysis, observed prevalence was lower in studies published as full-text as compared to those published in abstract form.

Table 1.

Subgroup analysis of PI-IBS prevalence (regardless of the time since infection) to assess stability of association and explore sources of heterogeneity. Pinteraction <0.10 implies statistically significant differences in the point prevalence of PI-IBS between different subgroups.

| Subgroups | Events/Total exposed (No. of studies) |

Prevalence of PI-IBS (%) |

95% CI | Pinteraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 2217/21421 (45) | 11.5 | 8.2–15.8 | - |

| By survey response rate | ||||

| • ≥80% | 429/12074 (16) | 7.9 | 4.1–14.6 | 0.049 |

| • 60–79% | 765/3490 (9) | 11.7 | 5.7–22.5 | |

| • 40–59% | 189/1952 (9) | 11.3 | 7.2–17.4 | |

| • <40% | 832/3905 (11) | 18.6 | 13.7–24.8 | |

| Rome Criteriona | ||||

| • Rome I | 608/3039 (9) | 12.9 | 7.7–20.9 | 0.93 |

| • Rome II | 515/8798 (18) | 12.0 | 7.4–18.8 | |

| • Rome III | 966/6332 (12) | 13.9 | 7.4–24.4 | |

| Locationb | ||||

| • North America | 613/4704 (10) | 7.5 | 3.8–14.1 | 0.34 |

| • Europe | 1497/15812 (27) | 13.0 | 8.1–20.3 | |

| • Asia | 101/861 (7) | 12.2 | 9.9–14.8 | |

| Publication type | ||||

| • Full text | 2038/20490 (41) | 10.9 | 7.6–15.5 | 0.054 |

| • Abstract | 177/931 (4) | 17.4 | 12.7–23.4 | |

| Method of IE Diagnosis | ||||

| • Laboratory confirmed | 1169/7281 (24) | 12.9 | 8.6–19.1 | 0.42 |

| • Clinically suspected or self-reported |

1046/14140 (21) | 9.9 | 6.0–16.1 | |

| Study Quality | ||||

| • High quality | 1223/13927 (25) | 13.0 | 8.3–19.9 | 0.48 |

| • Medium quality | 838/4143 (13) | 11.2 | 6.3–19.2 | |

| • Low quality | 154/3351 (7) | 7.3 | 3.0–16.5 | |

excluded 6 studies in which criterion was not reported

combined 1 study from New Zealand with Europe, and excluded one study performed in both Europe and North America

Relative risk of PI-IBS

Thirty studies included both IE exposed and non-exposed individuals (IE exposed n=18023 and non-exposed n=649496). Controls were age- and sex-matched (18 studies) and derived from the same geographic population and using the same search strategy as the IE cases (28 studies). Overall, patients exposed to IE had 3.8 times higher risk of developing IBS as compared to non-exposed individuals. The magnitude of increased risk was higher within 12m after IE (RR, 4.23; 95% CI, 3.15–5.69; I2=61%; 23 studies), and decreased (though remained significantly higher compared to non-exposed group) beyond 12m (RR, 2.33; 95% CI, 1.82–2.99; I2=76; 12 studies) [p-value for difference in RR within and beyond 12m=0.002] (Table 2; Appendix Table 6). Except for studies examining relative risk at 6 months (I2=20%), summary estimate shows substantial heterogeneity (I2=71–79%) among studies pooling estimates at different time-points. Four studies evaluating pediatric population observed a 4.1 times increased risk of PI-IBS (95% CI= 2.05–8.15; I2=0) compared to the 3.8 fold increased risk in 26 adult studies (95% CI= 2.89–5.09; I2=81), as compared to the non-exposed individuals (Pinteraction=0.87).

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis for PI-IBS relative risk in exposed as compared to the participants not exposed to gastrointestinal infection. Pinteraction <0.10 implies statistically significant differences in the relative risk of PI-IBS between different subgroups.

| Subgroups (No. of studies) |

Events/Total exposed |

Events/Total unexposed |

Relative risk |

95% CI | Pinteraction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within 12m of exposure | ||||||

| Overall (23) | 500/12831 | 2397/639635 | 4.23 | 3.15–5.69 | ||

| Rome Criterion | ||||||

| • Rome I (2) | 15/134 | 3/87 | 2.10 | 0.62–7.12 | 0.37 | |

| • Rome II (12) | 257/8214 | 268/49482 | 4.17 | 2.93–5.92 | ||

| • Rome III (7) | 197/4159 | 98/5553 | 3.13 | 2.18–4.47 | ||

| Organism | ||||||

| • Bacterial (10) | 254/7189 | 261/48340 | 4.22 | 2.84–6.25 | 1.00 | |

| • Viral (2) | 53/264 | 5/147 | 4.48 | 1.01–19.95 | ||

| • Protozoal (1) | 5/72 | 0/27 | 4.22 | 0.24–73.83 | ||

| Location | ||||||

| • North America (5) | 49/697 | 31/1108 | 2.02 | 1.24–3.30 | 0.01 | |

| • Europe (13) | 367/11527 | 2349/637701 | 4.69 | 3.20–6.86 | ||

| • Asia (5) | 84/725 | 17/826 | 5.50 | 2.96–10.21 | ||

| Method of diagnosis | ||||||

| • Laboratory confirmed (8) |

141/1421 | 2064/585513 | 5.01 | 2.67–9.40 | 0.36 | |

| • Clinically suspected (15) |

359/11528 | 333/54122 | 3.62 | 2.72–4.85 | ||

| Study Quality | ||||||

| • High (9) | 213/9187 | 2281/643240 | 4.94 | 2.83–8.63 | 0.67 | |

| • Medium (9) | 153/2274 | 53/2871 | 3.99 | 2.45–6.50 | ||

| • Low (5) | 134/1488 | 63/2524 | 3.49 | 2.08–5.86 | ||

| >12m after exposure | ||||||

| Overall (12) | 1363/11439 | 1060/57240 | 2.33 | 1.82–2.99 | ||

| Rome Criterion | ||||||

| • Rome I (2) | 432/1445 | 73/725 | 2.99 | 2.37–3.77 | 0.07 | |

| • Rome II (4) | 216/6330 | 650/47291 | 2.14 | 1.82–2.52 | ||

| • Rome III (3) | 679/1769 | 284/2195 | 2.42 | 1.56–3.78 | ||

| Organism | ||||||

| • Bacterial (7) | 691/8035 | 758/48291 | 2.24 | 1.63–3.10 | 0.011 | |

| • Viral (3) | 26/1839 | 46/6943 | 1.19 | 0.50–2.84 | ||

| • Protozoal (2) | 646/1565 | 256/2006 | 3.25 | 2.86–3.69 | ||

| Location | ||||||

| • North America (4) | 417/3468 | 119/7762 | 2.10 | 0.93–4.75 | 0.94 | |

| • Europe (4) | 846/7663 | 924/49191 | 2.34 | 1.65–3.32 | ||

| • Asia (3) | 42/264 | 15/243 | 2.50 | 1.42–4.39 | ||

| Method of diagnosis | ||||||

| • Laboratory confirmed (5) |

690/3531 | 328/9114 | 1.92 | 1.20–3.08 | 0.31 | |

| • Clinically suspected (7) |

673/7908 | 732/48126 | 2.52 | 2.01–3.15 | ||

| Study Quality | ||||||

| • High (5) | 634/7597 | 745/48019 | 2.10 | 1.45–3.04 | 0.005 | |

| • Medium (4) | 696/1994 | 265/2273 | 3.26 | 2.87–3.70 | ||

| • Low (3) | 33/1848 | 50/6948 | 1.23 | 0.58–2.62 | ||

Due to considerable difference in RR of PI-IBS within and beyond 12m, further analysis was stratified by time since exposure. Within 12m of IE, the observed RR of PI-IBS was higher in European and Asian countries as compared to studies conducted in North America (Table 2). There was no difference in observed RR based on criteria for IBS diagnosis, method of confirming IE, or by the type of the organism. Beyond 12m of IE, we observed a significant difference in RR of PI-IBS based on organism of exposure, with higher rates observed with protozoal/parasitic and bacterial IE as compared to viral IE, and based on study quality (high rates observed in medium and high quality studies, as compared to low quality studies).

On comparing the magnitude of increased risk of IBS by time since exposure to IE, we observed that RR of PI-IBS due to protozoal/parasitic remained stable over time, whereas the RR of IBS decreased in magnitude with bacterial (RR for within 12m of IE vs. >12m after IE: 4.2 vs. 2.2, p=0.01); there was a non-significant decrease in magnitude of risk with viral IE with increasing time (RR for within 12m of IE vs. >12m after IE: 4.5 vs. 1.2, p=0.13).

Risk factors for development of IBS after infectious enteritis

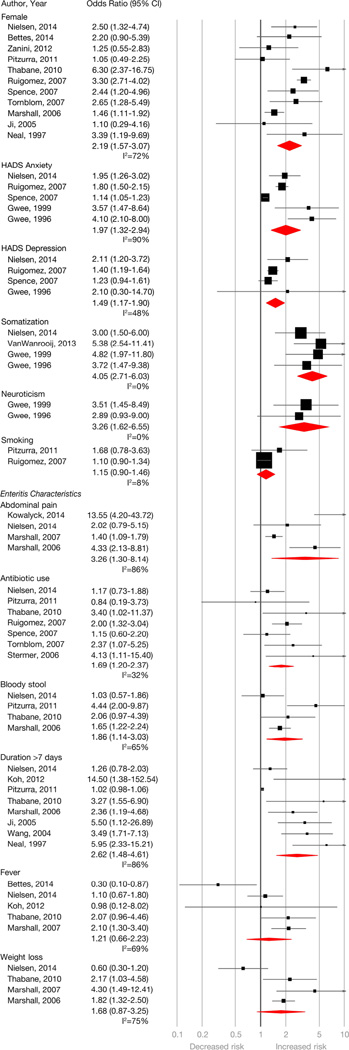

Of the 45 included studies, 33 assessed at least one risk factor for PI-IBS development (Figure 3). These are divided into demographic, enteritis-related and psychological factors below.

Figure 3.

Pooled odds ratio for host- and infectious enteritis-episode related risk factors for PI-IBS development. Moderate to considerable heterogeneity was observed for most estimates (I2 values for abdominal pain = 86%, antibiotic exposure = 32%, anxiety = 90%, bloody stool = 65%, depression = 48%, duration of initial enteritis >7 days = 86%, female sex = 72%, fever at time of enteritis = 69%, neuroticism – 0%, somatization = 0%, smoking = 8%, weight loss = 75%).

Demographic factors

Five studies assessed age as a risk factor.17, 32, 37, 50, 54 Variability in classification and lack of data precluded calculation of pooled OR. Twenty one studies appraised sex as a risk factor. Female sex was associated with a 2.2 times higher odds of developing PI-IBS (OR, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.57–3.07) based on 11 studies with extractable data.4, 8, 17, 20, 23, 31, 35, 40, 44, 45, 50 Summary estimate shows substantial heterogeneity (I2=72%). Three of the 9 studies without extractable data also showed a significant association for female sex.5, 13, 56 Based on two studies,17, 23 smoking was not associated with increased odds of PI-IBS (OR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.90–1.46); an additional study without extractable data also observed a non-significant association.42

Psychological factors

Prevalent anxiety (OR, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.32–2.94) and depression (OR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.17–1.90) measured using HADS, at time of IE was associated with PI-IBS development, based on 55, 17, 31, 44, 56 and 4 studies,17, 31, 44, 56 respectively. Summary estimate shows considerable heterogeneity for anxiety (I2=90%) and moderate for depression (I2=48%). Four additional studies were not included due to lack of sufficient data for meta-analysis; however, 3 of those 4 also showed a significant association.5, 15, 37 Somatization at the time of IE was assessed in four studies using the somatic symptom checklist and was associated with PI-IBS (OR, 4.05; 95% CI, 2.71–6.03).5, 31, 37, 56 Neuroticism at the time of IE was also associated with PI-IBS development (OR, 3.26; 95% CI, 1.62–6.55) based on two studies.5, 56 Adverse life events in preceding year,5 hypochondriasis,5 extroversion,56 negative illness beliefs,44 prior history of stress17 and sleep disturbance17 were also found to be associated with PI-IBS development in isolated studies.

Enteritis-related factors

Abdominal pain during IE was assessed in 15 studies as a risk factor for PI-IBS development, 9 of which found a significant association, 4 of which10, 20, 31, 33 had data for summarization (OR, 3.26; 95% CI, 1.30–8.14). Summary estimate shows considerable heterogeneity (I2=86%). Based on 8 studies,4, 20, 23, 31, 39, 40, 50, 54 diarrhea >7 days was associated with increased odds of PI-IBS (OR, 2.62; 95% CI, 1.48–4.61). Summary estimate shows considerable heterogeneity (I2=86%). Bloody stool was associated with PI-IBS development based on 4 studies20, 23, 31, 40 with an OR of 1.86 (95% CI, 1.14–3.03). Summary estimate shows substantial heterogeneity (I2=65%). Fever and weight loss with IE were not observed to be risk factors for PI-IBS. Based on 7 studies,17, 23, 31, 40, 44, 45, 59 antibiotic exposure at time of PI-IBS was associated with an increased odds of developing PI-IBS (OR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.20–2.37) (I2=32%).

Natural history of PI-IBS

Thirteen studies reported phenotype of new-onset IBS after IE. Three of these reported IBS-D or “non-constipation” predominant as the major IBS subtype. Of the other 10 studies, IBS-M was the most common phenotype reported (142/304, 46%, 95% CI, 31–62%) followed by IBS-D (120/304, 40%, 95% CI, 25–57%); IBS-C was the least common least common phenotype (42/304, 15%, 95% CI, 10–21%).

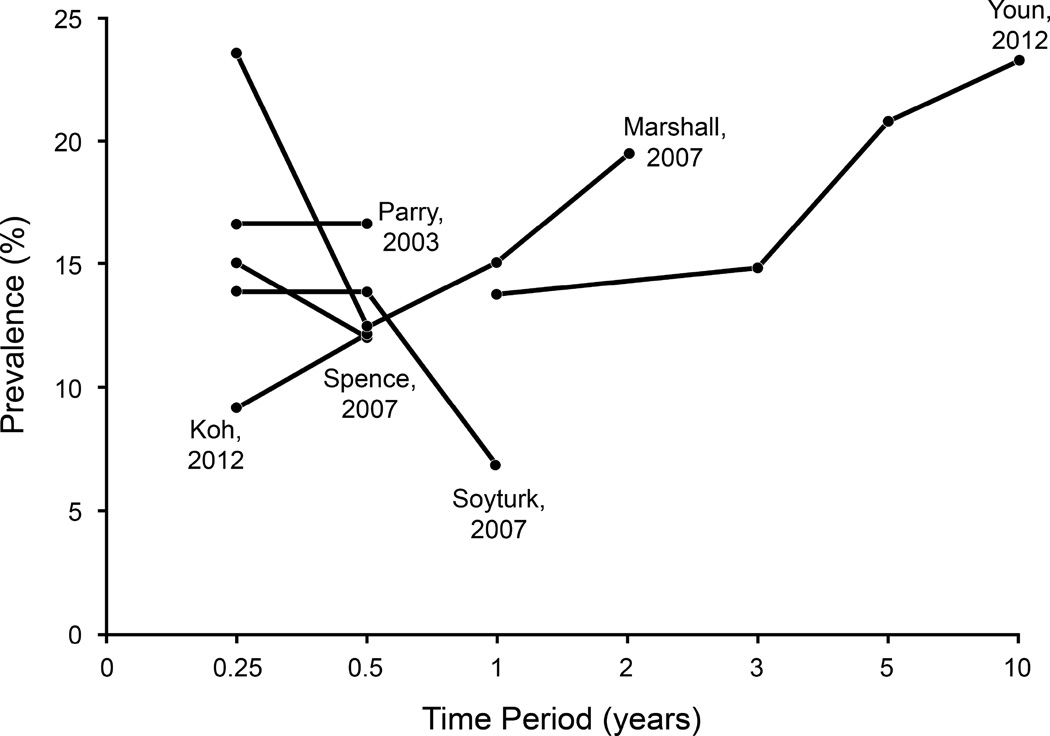

Overall, nine studies reported PI-IBS prevalence at multiple time points. Five of these had complete data, however, four studies had anywhere from 17–60% data missing at the longest time-point of assessment after IE. The at-risk population was the IE population at inception. Three studies observed decline in prevalence over time, whereas three observed an increase in prevalence over time since the IE episode; 2/8 reported stable prevalence over time (Appendix Figure 1).

Publication Bias

There was no evidence of publication bias based on qualitative assessment using the funnel plot or on quantitative analysis, based on Egger’s test for the primary outcome of prevalence of PI-IBS (p=0.15) or for RR of PI-IBS (p=0.13). However, given high heterogeneity observed in the overall analysis, these results should be interpreted with caution.

DISCUSSION

In this systematic analysis of 45 studies reporting on new-onset IBS in 21,421 subjects with IE, we made several key observations. First, we estimated a pooled point prevalence of PI-IBS of 11% (95% CI, 8.2–15.8), i.e., about 1 in 9 (95% CI, 7–13) individuals develop new-onset IBS following an episode of IE. The most common phenotypes are mixed and diarrhea predominant IBS. The overall risk of developing IBS is 4.2 times higher in individuals exposed to IE, as compared to non-exposed individuals, within the first year of exposure, and continues to remain high beyond the first year of exposure, albeit to a lower magnitude (RR, 2.3). This increased risk was stable across adults and children, across geographic regions, and in patients with clinically suspected or laboratory confirmed IE. Second, the risk of IBS is highest with protozoal enteritis, with ~40% of individuals developing IBS, followed by bacterial enteritis. Viral enteritis confers high risk of PI-IBS within the first year of exposure (RR similar to bacterial and protozoal enteritis), but this risk decreases to that of general non-exposed population beyond 1 year of exposure. In contrast, the risk of PI-IBS remains high even beyond 12m of exposure with bacterial and protozoal enteritis. Third, female sex, clinically severe IE (diarrhea duration >7d, bloody stools, abdominal pain), use of antibiotics to treat IE and psychological distress at the time of IE are associated with an increased risk of PI-IBS. Our findings on the chronic sequelae of gastrointestinal infections are significant from a public-health perspective. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 1 in 6 U.S. adults have a reported case of foodborne illness annually and there are additional unreported cases.18 In addition to the risk associated with foodborne illnesses in the community, over 60 million annual U.S travelers to international destinations are at an increased risk.60, 61 Finally, IE is common during deployment and recent studies have shown an increased incidence of IBS and other functional gastrointestinal disorders in the military personnel who are also under significant psychological stress during deployment.62 Even with a conservative estimate of 15% of the U.S. population being exposed to IE annually, based on our findings, an approximate 1.6% of the U.S. population (or 5.1 million people) likely develops new-onset IBS following IE annually. Modeling studies have estimated that PI-IBS probably contributes to the majority of IBS cases.63

Our 11% pooled prevalence of PI-IBS (6–12 months post IE) is comparable to the ~10% pooled prevalence reported in the previous meta-analyses.6, 64 However, the previous meta-analyses6, 64 observed a higher RR of PI-IBS (5.2–7.6) than our study. This is likely due to overestimation of RR with a small number of studies, with lower than expected prevalence of IBS in the unexposed cohorts in those studies.

The high magnitude (~40%) of PI-IBS risk observed after protozoal enteritis merits attention. Three studies published by the same group showed PI-IBS prevalence ranging from 39–80% following protozoal (Giardia) enteritis.11–13 Two of these studies were large and had a control group.12, 13 However, the incidence was studied at single time points >12 months in all 3 of these studies. Only one of these studies confirmed Giardia eradication in the stool sample;11 hence, some of the PI-IBS could be misclassification of chronic Giardiasis. In contrast, viral enteritis was associated lowest prevalence of PI-IBS at 4% and an RR of 1.2 at >12 months (non-significant when compared to the non-exposed). The pathophysiological mechanisms for the short lasting nature of virus related PI-IBS are not completely understood. It is possible that viruses cause less mucosal invasion and hence less stimulation of the neuromuscular and immune apparatus and downstream plasticity which can then lead to PI-IBS. Additionally, it is possible that viral enteritis does not have a significant effect on the microbiota composition and function which has been hypothesized to play a role in pathophysiology of PI-IBS.65

Identification of high-risk patients and potentially modifiable risk factors for PI-IBS is of interest in preventing development of PI-IBS. We comprehensively extracted data on risk factors from all of the available studies in a time frame. Females have 2.4 times odds of developing PI-IBS, as compared to males. This likely reflects an overall increased predilection for development of IBS symptoms in females. Anxiety, depression, somatization and neuroticism at the time of IE are potentially modifiable risk factors for development of PI-IBS. Psychological distress and maladaptive coping with symptoms are commonly observed in patients with IBS.66, 67 It is possible that psychological distress increases vulnerability to IBS development through increasing pathogenic virulence68 or attenuating host mucosal barrier and immune responses.69 The clinical severity of IE episode is associated with PI-IBS development. This could be due to pathogen or host factors. Finally, antibiotic use is a risk factor for PI-IBS development. Plausible mechanisms include microbiota perturbations in response to pathogenic insult and impaired ability of a subset of hosts to reestablish their baseline commensal microbiome. This could also be a reflection of “clinically severe” IE subgroup that is also more likely to receive antibiotics during the IE episode.

The strengths of our meta-analysis include (a) systematic literature search of multiple databases to identify 45 cohort studies that included over 20,000 IE patients, (b) comprehensive assessment all aspects of PI-IBS (prevalence, relative risk, risk factors, prognosis/natural history), and (c) with detailed, clinically relevant, a priori subgroup and sensitivity analyses. Our meta-analysis builds upon initial observations in previous meta-analyses, providing more detailed insights into the risk of PI-IBS over time, by different pathogens, and provides a more comprehensive understanding of risk factors, by summarizing data from 45 studies. First, our meta-analysis provides risk estimates from a significantly larger number of studies and assesses long-term risk (>12 months after IE in 12 studies) which was not studied in the previously published meta-analysis6 allowing us to conclude that increased risk of PI-IBS persists for an extended period after IE, albeit at lower rates than observed within 1 year of IE. Second, we were able to evaluate and observed differences in the risk of PI-IBS based on pathogen type (bacterial, viral, protozoal/parasitic). Third, while the previous meta-analysis assessed only anxiety and depression as risk factors for PI-IBS (based upon 4 studies), we have comprehensively assessed risk associated with several host (sex, smoking, anxiety, depression, somatization and neuroticism) and enteritis-related factors (abdominal pain, antibiotic use, bloody stool, duration of enteritis, fever, and weight loss) based on a larger number of studies, which may help identify patients at highest risk of PI-IBS after IE, enabling risk stratification for development of early strategies to minimize risk of long-term morbid sequelae of IE. Fourth, in contrast to the previous meta-analysis, we have conducted multiple a priori subgroup analysis to evaluate for stability of association and identify sources of heterogeneity across a range of factors. Through these analyses, we identified significant differences in observed risk of PI-IBS based on pathogen causing IE, differences in survey response rate as well as geographical location. We also observed that the point prevalence of PI-IBS was stable at different time points, using different criteria for IBS diagnosis, and by different methods of diagnosing IE. Fifth, from the 10 studies with data available on PI-IBS phenotype, we were able to conclude that IBS-M is the most common PI-IBS phenotype (46%), followed by IBS-D (40%) and IBS-C rarest (15%). Finally, through studies that provided data on risk of PI-IBS at different time points, we were able to offer a more comprehensive insight into the natural history of PI-IBS after IE.

Our meta-analysis has several limitations. First, we observed high heterogeneity for several analyses (I2 >95% for pooled point prevalence summary estimates). Additionally, certain risk-factor estimates also had substantial heterogeneity (abdominal pain, anxiety, duration of diarrhea >7 days, female sex). Heterogeneity is not uncommon in prevalence meta-analysis, partly due to large sample size of individual studies with precise estimates resulting in statistical heterogeneity. Conceptually, we minimized heterogeneity with well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. We also performed pre-planned subgroup analyses to assess stability of association and explore sources of heterogeneity. In our analysis, heterogeneity could be partly explained by response rates; the observed prevalence of PI-IBS, was 7.9% in studies with the survey response rates >80% as compared to 18.2% observed in studies with response rate <40%. This is likely related to responder bias with symptomatic individuals more likely to respond to surveys. The reported rates of PI-IBS were also higher in studies published only in abstract form, as compared to studies published in full after thorough peer review; estimates derived from the latter are probably more reliable. Second, while quantifying risk factors associated with PI-IBS, we used available adjusted and unadjusted data from individual studies for pooling. Unfortunately, multivariate analysis was inconsistently reported with adjustment for different confounding variables across studies, and this somewhat limits the inference that can be drawn from these observations. We acknowledge that pooling unadjusted estimates is not able to account for confounding factors, and the implicated risk factors observed through this analysis, may not necessarily be due to the single studied factor, but rather a conglomeration of factors (e.g., clinically severe IE and antibiotic use during IE, etc.). Finally, at an individual study level, most of the included studies were periodic surveys to individuals with known exposure to IE, and hence, were able to estimate cross-sectional prevalence, as opposed to the true incidence, and incompletely assessed the natural history of IBS in this population. Similar to IBS in general,70, 71 the PI-IBS diagnosis made by symptom based criteria over multiple time points following IE can fluctuate in individual subjects (complete or partial symptom resolution) or shift between different categories of FGIDs. However, the summary estimates should be interpreted with caution considering observed heterogeneity.

In conclusion, based on a meta-analysis of 45 studies, we observed that about one of every 9 individuals (95% CI, 7–13) exposed to food borne illness and other forms of infectious enteritis may develop IBS, at a rate 4 times higher than the non-exposed individuals. Protozoal and bacterial enteritis confer the greatest overall risk, although the magnitude of increased risk diminishes with time since exposure; in contrast, risk of IBS following viral enteritis is lower, with highest burden seen within the 1st year of exposure, and risk becomes comparable to the general, non-exposed population following that. It is important to consider PI-IBS during care of patients with chronic gastrointestinal symptoms following an episode of IE, especially in patients at high-risk of developing the same: females, patients with prevalent anxiety and depression at time of IE, and patients with clinically severe IE, and those treated with antibiotics. Finally, antibiotic stewardship during IE may reduce the risk of PI-IBS development. Future research will benefit from registries for prospective follow up of patients with IE and from mechanistic studies to determine host- and pathogen-related pathophysiological mechanisms that will inform on PI-IBS and potentially IBS in general.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ms. Lori Anderson for administrative assistance and Mr. Mark Curry for help with illustrations. We also acknowledge Dr. Pensabene and Dr. Nielsen for providing us additional data on risk-factors for PI-IBS development.

Funding Sources: NIH K23 (DK103911), Pilot and Feasibility Award from Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology (NIH P30DK084567), and American Gastroenterological Association Rome Foundation Functional Gastroenterology and Motility Disorders Pilot Research Award to MG. NIH/NLM training grant (T15LM011271) to SS.

Abbreviations

- PI-IBS

post-infectious IBS

- IE

infectious enteritis

Appendix

Appendix Table 1.

Description of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Author | Year | Pathogen | Number of subjects | Geographic location |

Follow-up time period |

Rome Criteria |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed | Controls | ||||||

| Pensabene1 | 2015 | Rotavirus, Adenovirus, Norovirus, Salmonella, Giardia |

32 | 32 | Italy | 6 months | Rome III |

| Schwille2 | 2015 | Blastocystis hominis, Salmonella, Shigella, Giardia, Campylobacter |

135 | NA | Germany | 1–2 years | Rome III |

| Bettes3 | 2014 | Campylobacter, E.coli, Salmonella, Shigella |

425 | NA | U.S.A | 6 months | Rome III |

| Cremon4 | 2014 | Salmonella | 204 | 189 | Italy | <1 year, 1–5 years, >5 years |

Rome III |

| Hanevik5 | 2014 | Giardia | 748 | 878 | Norway | 6 years | Rome III |

| Kowalcyk6 | 2014 | NA | 2428 | 2354 | Netherlands | 12 months | Rome III |

| Nair7 | 2014 | E. coli, Salmonella, Providencia, Cryptosporidium |

348 | 469 | U.S.A | 6 months | Rome II |

| Nielsen8 | 2014 | C. concisus, C. jejuni | C. concisus = 106 C. jejuni = 162 |

NA | Northern Denmark |

6 months | NA |

| Lalani9 | 2013 | NA | 154 | 516 | U.S.A | 3,6,9 months | Rome III |

| Van wanrooij10 | 2013 | Norovirus, Giardia, Campylobacter jejuni |

311 | 717 | Belgium | 12 months | Rome III |

| Koh11 | 2012 | Shigella, Salmonella, Vibrio cholera, E. coli |

65 | NA | South Korea | 3 months, 6 months | Rome II |

| Porter12 | 2012 | Norovirus | 1718 | 6875 | U.S.A | 1–4.7 years | NA |

| Wensaas13 | 2012 | Giardia | 817 | 1128 | Norway | 3 years | Rome III |

| Youn14 | 2012 | Shigella | 124 | 105 | South Korea | 12 months, 3,5,10 years |

NA |

| Zanini15 | 2012 | Norovirus | 178 | 121 | Italy | 12 months | Rome III |

| Pitzurra16 | 2011 | NA | 852 | 1624 | Switzerland | 6 months | Rome III |

| Schwille17 | 2011 | Salmonella, Campylobacter |

48 | NA | Germany | 6 months | Rome III |

| Lim18 | 2010 | Shigella | 71 | 65 | NA | 8 years | NA |

| Thabane19 | 2010 | E. coli O157:H7, Campylobacter |

305 | 162 | Canada | 8 years | Rome II |

| Hanevik20 | 2009 | Giardia | 82 | NA | Norway | 12–30 months | Rome II |

| Jung21 | 2009 | Shigella | 87 | 89 | South Korea | 1,3,5 years | Rome II |

| Saps22 | 2009 | Rotavirus | 44 | 44 | U.S.A & Italy |

>2 years | Rome II |

| Saps23 | 2008 | Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter |

44 | 44 | Italy | 6 months | Rome II |

| Marshall24 | 2007 | Norovirus | 89 | 29 | Canada | 3,6,12,24 months | Rome I |

| Piche25 | 2007 | Clostridium difficile | 23 | NA | France | 3 months | Rome II |

| Ruigomez26 | 2007 | Shigella, Campylobacter, Salmonella |

5894 | 46996 | United Kingdom |

1–12 months, 13–24 months, 24–36 months, >36 months |

Rome II |

| Soyturk27 | 2007 | Trichinella britovi | 72 | 27 | Turkey | 4,6,12 months | Rome II |

| Spence28 | 2007 | Campylobacter | 547 | NA | New Zealand | 6 months | Rome II |

| Tornblom29 | 2007 | Campylobacter, Shigella, C. difficile, E.coli, Salmonella, Rotavirus, Adenovirus, Calicivirus, Giardia |

333 | NA | Sweden | 5 years | Rome II |

| Borgaonkar30 | 2006 | Bacterial | 191 | NA | Canada | 3 months | Rome I |

| Marshall31 | 2006 | NA | 1368 | 701 | Canada | 24–36 months | Rome I |

| Stermer32 | 2006 | NA | 118 | 287 | Israel | 6 months | Rome II |

| Ji33 | 2005 | Shigella | 101 | 102 | Korea | 12 months | Rome II |

| Mearin34 | 2005 | Salmonella | 271 | 335 | Spain | 12 months | Rome II |

| Okhuysen35 | 2004 | NA | 61 | 36 | USA | 6 months | Rome II |

| Wang36 | 2004 | NA | 295 | 243 | China | 9 months | Rome II |

| Cumberland37 | 2003 | NA | 815 | 753 | England | 3 months | NA |

| Dunlop38 | 2003 | Campylobacter | 747 | NA | UK | 3 months | Rome I |

| Ilnyckyj39 | 2003 | NA | 48 | 61 | Canada | 3 months | Rome I |

| Parry40 | 2003 | Bacterial | 108 | 206 | England | 3,6 months | NA |

| Gwee41 | 1999 | Shigella, Campylobacter, Salmonella |

109 | NA | UK | 12 months | Rome I |

| Rodriguez42 | 1999 | Bacterial | 318 | 584308 | England | 12 months | NA |

| Neal43 | 1997 | Bacterial | 366 | NA | UK | 6 months | Rome I |

| Gwee44 | 1996 | NA | 86 | NA | UK | 6 months | NA |

| Mc Kendrick45 | 1994 | Salmonella | 38 | NA | UK | 12 months | Rome I |

Appendix Table 2 provides details on accrual characteristics for cases, controls and methods of studies included in the meta-analysis

References

. Pensabene L, Talarico V, Concolino D, et al. Postinfectious functional gastrointestinal disorders in children: a multicenter prospective study. J Pediatr 2015;166:903–7.

. Schwille-Kiuntke J, Enck P, Polster AV, et al. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome after travelers' diarrhea--a cohort study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015;27:1147–55.

. Bettes N, Griffith J, Camilleri M, et al. Risk and predictors of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome among community-acquired cases of bacterial enteritis. Gastroenterology 2014;146:S-538.

. Cremon C, Stanghellini V, Pallotti F, et al. Salmonella gastroenteritis during childhood is a risk factor for irritable bowel syndrome in adulthood. Gastroenterology 2014;147:69–77.

. Hanevik K, Wensaas KA, Rortveit G, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic fatigue 6 years after giardia infection: a controlled prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:1394–400.

. Kowalcyk BK, Smeets HM, Succop PA, et al. Relative risk of irritable bowel syndrome following acute gastroenteritis and associated risk factors. Epidemiol Infect 2014;142:1259–68.

. Nair P, Okhuysen PC, Jiang ZD, et al. Persistent abdominal symptoms in US adults after short-term stay in Mexico. J Travel Med 2014;21:153–8.

. Nielsen HL, Engberg J, Ejlertsen T, et al. Psychometric scores and persistence of irritable bowel after Campylobacter concisus infection. Scand J Gastroenterol 2014;49:545–51.

. Lalani T, Tribble D, Ganesan A, et al. Travelers' diarrhea risk factors and incidence of postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome (PI-IBS) in a large prospective cohort of Department of Defense beneficiaries (TRAVMIL). Am J Trop Hyg 2012;89:223.

. Van Wanrooij S, Wouters M, Mondelaers S, et al. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia following an outbreak of tap water contamination. Gastroenterology 2013;144:S536–7.

. Koh SJ, Lee DH, Lee SH, et al. Incidence and risk factors of irritable bowel syndrome in community subjects with culture-proven bacterial gastroenteritis. Korean J Gastroenterol 2012;60:13–8.

. Porter CK, Faix DJ, Shiau D, et al. Postinfectious gastrointestinal disorders following norovirus outbreaks. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55:915–22

. Wensaas KA, Langeland N, Hanevik K, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic fatigue 3 years after acute giardiasis: historic cohort study. Gut 2012;61:214–9.

. Youn Y, Park S, Park C, et al. The clinical course of postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) after shigellosis: A 10-year follow-up study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012;24:102.

. Zanini B, Ricci C, Bandera F, et al. Incidence of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome and functional intestinal disorders following a water-borne viral gastroenteritis outbreak. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:891–9.

. Pitzurra R, Fried M, Rogler G, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome among a cohort of European travelers to resource-limited destinations. J Travel Med 2011;18:250–6.

. Schwille-Kiuntke J, Enck P, Zendler C, et al. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome: follow-up of a patient cohort of confirmed cases of bacterial infection with Salmonella or Campylobacter. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011;23:e479–88.

. Lim H, Kim H, Youn Y, et al. The clinical course of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome: an eight-year follow-up study. Gastroenterology 2010;138:S623.

. Thabane M, Simunovic M, Akhtar-Danesh N, et al. An outbreak of acute bacterial gastroenteritis is associated with an increased incidence of irritable bowel syndrome in children. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:933–9.

. Hanevik K, Dizdar V, Langeland N, et al. Development of functional gastrointestinal disorders after Giardia lamblia infection. BMC Gastroenterol 2009;9:27.

. Jung IS, Kim HS, Park H, et al. The clinical course of postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome: a five-year follow-up study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009;43:534–40.

. Saps M, Pensabene L, Turco R, et al. Rotavirus gastroenteritis: precursor of functional gastrointestinal disorders? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;49:580–3.

. Saps M, Pensabene L, Di Martino L, et al. Post-infectious functional gastrointestinal disorders in children. J Pediatr 2008;152:812–6, 816 e1.

. Marshall JK, Thabane M, Borgaonkar MR, et al. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome after a food-borne outbreak of acute gastroenteritis attributed to a viral pathogen. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:457–60.

. Piche T, Vanbiervliet G, Pipau FG, et al. Low risk of irritable bowel syndrome after Clostridium difficile infection. Can J Gastroenterol 2007;21:727–31.

. Ruigomez A, Garcia Rodriguez LA, Panes J. Risk of irritable bowel syndrome after an episode of bacterial gastroenteritis in general practice: influence of comorbidities. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:465–9.

. Soyturk M, Akpinar H, Gurler O, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in persons who acquired trichinellosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1064–9.

. Spence MJ, Moss-Morris R. The cognitive behavioural model of irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective investigation of patients with gastroenteritis. Gut 2007;56:1066–71.

. Tornblom H, Holmvall P, Svenungsson B, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms after infectious diarrhea: a five-year follow-up in a Swedish cohort of adults. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:461–4.

. Borgaonkar MR, Ford DC, Marshall JK, et al. The incidence of irritable bowel syndrome among community subjects with previous acute enteric infection. Dig Dis Sci 2006;51:1026–32.

. Marshall JK, Thabane M, Garg AX, et al. Incidence and epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome after a large waterborne outbreak of bacterial dysentery. Gastroenterology 2006;131:445–50; quiz 660.

. Stermer E, Lubezky A, Potasman I, et al. Is traveler's diarrhea a significant risk factor for the development of irritable bowel syndrome? A prospective study. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:898–901.

. Ji S, Park H, Lee D, et al. Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome in patients with Shigella infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;20:381–6.

. Mearin F, Perez-Oliveras M, Perello A, et al. Dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome after a Salmonella gastroenteritis outbreak: oneyear follow-up cohort study. Gastroenterology 2005;129:98–104.

. Okhuysen PC, Jiang ZD, Carlin L, et al. Post-diarrhea chronic intestinal symptoms and irritable bowel syndrome in North American travelers to Mexico. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:1774–8.

. Wang LH, Fang XC, Pan GZ. Bacillary dysentery as a causative factor of irritable bowel syndrome and its pathogenesis. Gut 2004;53:1096–101.

. Cumberland P, Sethi D, Roderick PJ, et al. The infectious intestinal disease study of England: a prospective evaluation of symptoms and health care use after an acute episode. Epidemiol Infect 2003;130:453–60.

. Dunlop SP, Jenkins D, Neal KR, et al. Relative importance of enterochromaffin cell hyperplasia, anxiety, and depression in postinfectious IBS. Gastroenterology 2003;125:1651–9.

. Ilnyckyj A, Balachandra B, Elliott L, et al. Post-traveler's diarrhea irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:596–9.

. Parry SD, Stansfield R, Jelley D, et al. Does bacterial gastroenteritis predispose people to functional gastrointestinal disorders? A prospective, community-based, case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:1970–5.

. Gwee KA, Leong YL, Graham C, et al. The role of psychological and biological factors in postinfective gut dysfunction. Gut 1999;44:400–6.

. Rodriguez LA, Ruigomez A. Increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome after bacterial gastroenteritis: cohort study. BMJ 1999;318:565–6.

. Neal KR, Hebden J, Spiller R. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms six months after bacterial gastroenteritis and risk factors for development of the irritable bowel syndrome: postal survey of patients. BMJ 1997;314:779–82.

. Gwee KA, Graham JC, McKendrick MW, et al. Psychometric scores and persistence of irritable bowel after infectious diarrhoea. Lancet 1996;347:150–3.

. McKendrick MW, Read NW. Irritable bowel syndrome--post salmonella infection. J Infect 1994;29:1–3.

Appendix Table 2.

Accrual characteristics for cases and controls methods of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study | Patients inclusion criteria |

Patients exclusion criteria |

Methods | Cohort selection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post infectious functional gastrointestinal disorders in children: A multicenter Prospective study. Pensabene et. al., 2015 |

- Age 4 to 17 yr - Acute diarrhea (>3 liquid stools/24h for >3d to <2w) with positive stool culture, parasitic or viral tests - Recruitment <1m from IE - Completed questionnaire for pediatric FGIDs |

- Neurologic impairment, recent surgery, celiac disease, IBD, cystic fibrosis, food allergies, transplantation, immunosuppression, liver, renal, metabolic or rheumatologic disease. - Inability to communicate - No 6m F/u |

- IBS excluded at baseline: not specified - Questionnaire completed at outpatient visit or over the phone by the same health care provider - Data complete on IE and control cohorts at 3 time- points (1m, 3m, 6m) |

- 6 pediatric departments from 2007–2010 - Control group: similar age and sex presenting for a well-child visit or emergency department for minor trauma within 4w of IE case |

| Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome after travelers’ Diarrhea-a cohort study Schwille-Kiuntke J et al., 2015 |

- Age >18 yrs - Travelers’ diarrhea: while or up to 7 days during travel to a high risk country. 50% population had at least one pathogen confirmed on the day of assessment |

- Another GI diagnosis explaining symptoms, menstrual associated symptoms excluded. |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Mailing followed by online survey (twice): 39.4% response rate to initial invitation and 72.2% among those consented. Incomplete datasets excluded. |

- Travel clinic patients from 2009–10 travel - Control group: none |

| Risks and predictors of PI- IBS among community- acquired cases of bacterial enteritis. Bettes et. al., 2014 (abstract) |

- Age 18–65 yrs - Culture proven IE patients |

- Pre-existing diagnosis of IBS, IBD, microscopic colitis, abdominal surgeries |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Mailed questionnaire (twice) followed by phone calls: completed by 37% at f/up time-point |

- Reported IE cases to state health department - Control group: none |

|

Salmonella Gastroenteritis during childhood is a risk factor for irritable bowel syndrome in adulthood. Cremon et. al., 2014 |

- Age >18 yr at the time of the questionnaire; children and adults at time of IE - Positive stool culture for Salmonella |

- Pre-existing diagnosis of celiac disease, IBS, IBD, dyspepsia - Permanent resident of Bologna |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Mailed questionnaire (up to 3 times) followed by phone calls: completed by 54% cases and 50% controls at f/up time-point |

- Contaminated food in 36 Bologna schools on Oct 19, 1994 - Control group: from Bologna census. Age, sex & residence area matched |

| Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic fatigue 6 years after Giardia infection: a controlled prospective cohort study. Hanevik et. al., 2014 |

- Lab proven Giardia infection - Resident of the outbreak area |

- Excluded questionnaires with incomplete, ambiguous answers or not answered |

- IBS excluded at baseline: not specified - Mailed questionnaire: completed by 60% cases and 36% controls at f/up time-point |

- Samples from only laboratory in Bergen area 10/2004–12/2005 - Control group: 2:1. Age, sex matched. |

| RR of IBS following acute gastroenteritis and associated risk factors. Kowalcyk et. al., 2014 |

- Age 18–70 yr - IE patients (Coding based confirmed infection with diarrhea) with atleast 1 yr f/up data in electronic database |

- Pre-existing diagnosis of cancer, alcohol abuse, IBD, IBS, functional bowel disease, abdominal surgery, ≥5 prescriptions related to IBS, IBD - IE symptoms 12m before case identification |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - IBS identified by ICPC code during f/u time points |

- Primary care patients between 1998–2009 - Control group: outpatients with no IE diagnosis presenting within 1m of IE case. Age, sex matched. |

| Persistent abdominal symptoms in US adults after short- term stay in Mexico. Nair et. al., 2014 |

- Age >18 yr or >16 yr with consent - Traveled to Mexico (stay >5d) - Travelers’ diarrhea (≥3 soft/watery stools/24h) with positive stool cultures, parasitic/protozoal |

- History of unstable medical illness - Preexisting self- identified persisting GI symptoms, pregnancy, use of antibiotics in the past week of IE, lactose intolerance |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Mailed questionnaire at 6m (single F/u) - Excluded those on anti-diarrheal prophylaxis, non- responders - Data complete |

- Travelers between 6/2002– 1/2008 - Control group: no h/o of diarrhea during travel. No matching. |

| Psychometric scores & persistence of irritable bowel after C. concisus infection. Nielsen et. al., 2014 |

- Age >18 yr - C. concisus positive stools sample |

- Co-pathogens in stool sample - Not responding telephone calls, declined or inability to participate - Resided outside area of study - Terminal illness or IBD, IBS, microscopic or other non-infective colitis |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Mailed questionnaire: returned by 41% cases & 45% controls at 6m (single F/u) - Excluded new onset IBD, microscopic colitis, incomplete responses -Data complete |

- Stool samples submitted for diarrhea from 1/2009–12/2010 - Control group: C. jejuni/coli. Younger, greater proportion of males & less comorbidities. No non exposed controls. |

| Epidemiology and self-treatment of Travellers’ Diarrhea in a large, prospective cohort of department of defense beneficiaries. Lalani et. al., 2013 |

- Adult and pediatric travelers with IE: ≥3 unformed stools and ≥1 of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fever and blood in stool in 24hrs. - Completed illness diary. |

- Not completing any f/up surveys |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes. - Diary or survey: 85% responders. Missing data on 23% (3m, 6m), 38% (9m) and 41% (12m) of the cases eligible for IBS assessment |

- DoD beneficiaries traveling outside US for ≤6.5 m between 1/2010– 7/2013 - Control group: no travelers’ diarrhea |

| PI-IBS and functional dyspepsia following an outbreak of tap water contamination. Van wanrooij et. al., 2013 (abstract) |

- Age >18 yrs - IE: onset of self- reported acute gastrointestinal discomfort within 2w after tap water contamination |

- No further details | - IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Mailed questionnaires: completed at 1 yr by 7.5% of entire geographic population (30% of those had IE) |

- Drinking water contamination in 12/2010 - Control group: same geographic population without IE symptoms. |

| Incidence and Risk Factors of IBS in Community Subjects with Culture-proven Bacterial Gastroenteritis. Koh et. al., 2012 |

- Age >15–<75 yrs. - IE: Culture proven bacterial plus ≥2 of fever, vomiting and diarrhea |

- Pregnancy, severe psychiatric disease, cancer, IBD, hyperthyroidism and previous abdominal surgery |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Telephone interview; complete data available at 3 and 6 m f/up |

- Community cohort 1/2008– 2/2010 - Control group: none |

| Postinfectious Gastrointestinal Disorders Following Norovirus Outbreaks. Porter et. al., 2012 |

- IE ICD code during the outbreaks |

- <1y f/u in Defense Medical Surveillance system |

- IBS excluded at baseline: not specified - PI-IBS determined using new onset ICD codes after IE |

- Military health services database 2004–2011 - Control group: 4:1. Same clinical setting, branch and rank. Within & outside of IE time frame |

| Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic fatigue 3 years after acute giardiasis: historic cohort study. Wensaas et. al., 2012. |

- Lab proven Giardia infection - Resident of the outbreak area |

- Excluded questionnaires with incomplete, ambiguous answers or not answered. |

- IBS excluded at baseline: not specified - Mailed questionnaire (twice, over 1 m): completed by 65% cases and 31% controls (96% complete for IBS responses) |

- Samples from only laboratory in Bergen area 10/2004–12/2005 - Control group: 2:1. Age, sex matched. |

| The clinical course of PI-IBS after shigellosis: A 10- year follow-up study Youn et. al. 2012 (abstract) |

- Employees with diarrhea, abdominal pain and fever treated for shigellosis. |

- Pregnancy, IBS, IBD, medication that can affect bowel function and abdominal surgery |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Mailed questionnaire: 10 yr data completed by 69% cases and 72% controls. |

- Employees from hospital food outbreak in 12/2001 - Control group: Age, sex matched employees with no IE symptoms or exposure to contaminated food |

| Incidence of Post- infectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Functional Intestinal disorders following water-borne viral gastroenteritis outbreak. Zanini et. al., 2012 |

- Resident of the outbreak area - IE criteria: ≥2 of: fever, vomiting, diarrhea or positive Norovirus stool culture within the epidemic period. |

- Not returning questionnaire |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes. - Mailed and phone questionnaires responded by 96% IE cases and 72% controls at 12 month |

- Water-borne outbreak summer 2009 - Control group: same area, no IE symptoms during outbreak, identified 6 m after IE. |

| Irritable Bowel Syndrome among a cohort of European travellers to resource – limited destinations. Pitzurra et. al., 2011 |

- German speaking Swiss adults - Stayed in travel destination for 1–8 weeks - Travelers’ diarrhea: >3 unformed stools/24hrs |

- Pregnant women, planning to use antibiotic prophylaxis, HIV, immunosuppressive conditions, cancer, anemia. Previous GI symptoms or diseases, IBS or chronic diarrhea |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Mailed questionnaire followed by e- mails and phone calls: completed by 72% |

- Travel clinic patients 7/2006– 1/2008 - Control group: no Travelers’ diarrhea |

| Post - infectious irritable bowel syndrome: follow- up of a patient cohort of confirmed cases of bacterial infection with Salmonella or Campylobacter. Schwille et. al., 2011 |

- IE: Hospitalized with lab proven IE |

- No questionnaire answered, lost f/u, declined to participate, pre- existing IBS/IBD |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Postal questionnaire: responded to 57% IE cases and 54% controls |

- Hospitalized patients 2000–09 - Control group: None |

| The clinical course of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome: An eight-year follow- up study. Lim et. al., 2010 (abstract) |

- Hospital employees with diarrhea, abdominal pain or fever during outbreak. |

- Not specified | - IBS excluded at baseline: not specified - Standard questionnaire; completed by 53% IE cases, 62% controls at 8 yrs |

- Hospital outbreak - Control group: Age and sex matched. Same hospital employees with no IE symptoms. |

| An outbreak of acute bacterial gastroenteritis is associated with an increased incidence of irritable bowel syndrome in children. Thabane et. al., 2010 |

- Age <16 yrs at enrollment but >16 yrs at f/up - Permanent resident of Walkerton - Self reported or clinically suspected IE: acute bloody diarrhea or >3 loose stools/24hrs or lab proven |

- Previous h/o IBS, IBD or other GI symptoms |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Standardized interview & questionnaire completion: complete data available for cumulative incidence assessment. |

- Walkerton outbreak: 5/2000 - Control group: Resident in the same area with no IGE symptoms. |

| Development of functional gastrointestinal disorders after Giardia lamblia infection. Hanevik et. al., 2009 |

- Lab proven Giardia infection - Negative stool studies, EGD with biopsies, labs at time of assessment |

- Excluded incomplete or ambiguous answers |

- IBS excluded at baseline: not specified - Structured interviews: complete data available. |

- 2004 outbreak; data collected 2006–07 - Control group: Age, sex matched. 2:1. |

| The clinical course of postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome: a five- year follow-up study. Jung et. al., 2009 |

- Employees with diarrhea, abdominal pain and fever treated for shigellosis. |

- Pregnancy, IBS, chronic bowel diseases, medication that can affect bowel function and abdominal surgery |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Mailed questionnaire, direct interview or e-mail: complete data available at 5 years post IE. |

- Employees from hospital food outbreak in 12/2001 - Control group: Age, sex matched employees with no IE symptoms or exposure to contaminated food |

| Rotavirus Gastroenteritis: Precursor of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders? Saps et. al., 2009 |

- Age 4–18 yrs - Acute diarrhea with positive stool studies |

- Unable to communicate, immunosuppression therapy, IBD, IBS, celiac disease, transplant, food allergy, rheumatologic disease, stool positive for bacteria or other viruses |

- IBS excluded at baseline: not specified - Telephone questionnaire: complete data available |

- Stool studies from hospital 1/2002–12/2004 - Control group: Age and sex match from well child/emergency visit within 4 wk of IE case |

| Post-Infectious functional gastrointestinal disorders in children. Saps et. al., 2008 |

- Age 3–19 yrs - Acute diarrhea with positive bacterial stool culture |

- Unable to communicate, immunosuppression therapy, IBD, IBS, celiac disease, transplant, food allergy, rheumatologic disease. |

- IBS excluded at baseline: not specified - Telephone questionnaire: complete data available |

- Stool studies from hospital 1/2001–12/2005 - Control group: Age and sex match from well child /emergency visit within 4 wk of IE case |

| Postinfectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome After a Food-Borne Outbreak of Acute Gastroenteritis Attributed to a Viral Pathogen. Marshall et. al., 2007 |

- Clinical IE: self- reported fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea or vomiting during the outbreak (conference) or within 3 days of its end. |

- IBS, IBD, colorectal carcinoma, abdominal surgery, radiation enterocolitis, microscopic colitis, hereditary polyposis, intestinal ischemia or celiac disease. |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Mailed questionnaire: Response rate 97% (3m), 96% (6m), 92% (12m) and 83% (24m). |

- Outbreak in 2002 - Control group: exposed to outbreak area but no IGE symptoms. |

| Low risk of irritable bowel syndrome after Clostridium difficile infection. Piche et. al., 2007 |

- Age >18 yrs - Symptomatic and lab proven IE |

- Medication that alter bowel function, IBS, IBD, microscopic colitis, celiac disease, lactose intolerance and prior CDI. |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Standardized questionnaire: Complete data available. |

- Bacteriology lab 2001–02. - Control group: None |

| Risk of Irritable Bowel Syndrome after an Episode of Bacterial Gastroenteritis in General Practice: Influence of Comorbidities. Ruigomez et. al., 2007 |

- Age 20 – 74 yrs - Lab proven bacterial IE |

- Cancer, alcohol abuse, prior IE, IBD or any other colitis, IBS or any use of >5 GI associated medications |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - F/up based on ICD codes and corroborating symptoms in database. Complete databases. |

- UK general practice research database. 1992– 2001. - Control group: Age, sex matched, timing of IE and geographic location |

| Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Persons who acquired Trichinellosis. Soyturk et. al., 2007 |

- Hx of consumption of contaminated meat. - Lab proven |

- Pregnancy, IBD, IBS, celiac disease, colon cancer, abdominal surgery and another IE in last 6 months |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - In person or phone interview. Complete data at 12 m. |

- Hospitalized patients - Control group: trichinellosis negative and no clinical symptoms to suggest IE |

| The cognitive behavioral model of irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective investigation of patients with gastroenteritis. Spence et. al. 2007 |

- Age >16 yr with positive stool culture |

- Previous GI symptoms or illnesses. |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Mailed questionnaire: 52% response rate. Those with IBS at both 3 and 6 months post IE were classified as PI-IBS |

- Community clinic patients - Control group: none. |

| Gastrointestinal Symptoms after Infectious Diarrhea: A Five- Year Follow-Up in a Swedish Cohort of Adults. Tornblom et. al., 2007 |

- Age > 15 yrs - Patients with lab proven (53%) or strongly suspected infectious diarrhea |

- HIV | - IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Mailed questionnaire (twice) followed by phone interview in selected cases: 71% response rate |

- Hospitalized patients 1996–97 - Control group: Age, sex matched. 1.1. |

| The Incidence of Irritable Bowel Syndrome Among Community Subjects With Previous Acute Enteric Infection. Bargonkoar et. al., 2006 |

- Age >18 yr - Positive stool with new onset of abdominal pain and/or diarrhea |

- IBS, IBD, any bowel resection, hereditary polyp syndrome, use of laxatives, prokinetics (within 7 days), ongoing evaluation for unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms. |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Phone questionnaire: data available on 52% at 3 month (single F/up time point) |

- Specific health regions 1999– 2001 - Control group: none |

| Incidence and epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome after a large waterbone outbreak of bacterial dysentery. Marshall et. al., 2006 |

- Age >16 yr - Permanent resident of Walkerton - Self reported or clinically suspected IE: documented record or acute bloody diarrhea or >3 loose stools/24hrs or lab proven |

- Previous h/o IBS, IBD or other GI symptoms |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Standardized interview & questionnaire completion: complete data available for cumulative incidence assessment. |

- Walkerton outbreak: 5/2000 - Control group: Resident in the same area with no IGE symptoms. |

| Is Traveler’s Diarrhea a Significant Risk Factor for the Development of Irritable Bowel Syndrome? A Prospective Study. Stermer et. al., 2006 |

- Age 18–65 yr - Travelling for 15– 180 days - Travelers’ diarrhea: >3 loose stools/24 hrs, after 48 hrs of arrival |

- Previous IBS, IBD, liver transplant, declined participation |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Mailed questionnaire followed by phone call during f/u: complete data available at 6 m (single F/up time) |

- Potential travelers visiting travel clinic - Control group: travelers with no traveler diarrhea |

| Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome in patients with shigella infection. Ji et. al., 2005 |

- Employees with diarrhea, abdominal pain and fever treated for shigellosis. |

- Pregnancy, IBS, chronic bowel diseases, medication that can affect bowel function and abdominal surgery |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Mailed questionnaire: complete data available at 3,6 and 12 months |

- Employees from hospital food outbreak in 12/2001 - Control group: Age, sex matched employees with no IE symptoms or exposure to contaminated food |

| Dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome after a Salmonella gastroenteritis outbreak: one- year follow-up cohort study. Mearin et. al., 2005 |

- Age: adults - IE: living in the outbreak area with: diarrhea, fever and abdominal pain within outbreak dates. Some cases had culture confirmation. |

- Not specified | - IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Standard questionnaire: 71% IE & 46% controls responders. F/up at 3m (IE: 54%, control: 34%), 6m (IE: 50%, control: 34%), 12m (IE: 40%, control: 28%) |

- 2002 outbreak - Control group: 2:1. Age, sex and residence area matched. |

| Post-diarrhea chronic intestinal symptoms and irritable bowel syndrome in North American travelers to Mexico. Okhuysen et. al., 2004 |

- Age: adults - IE: ≥3 unformed stools/day and abdominal pain, excessive gas/flatulence, nausea, vomiting, fever, fecal urgency, blood and/or mucus and tenesmus |

- Prophylactic antibiotics, anti- diarrheal agents during travel. |

- IBS excluded at baseline: not specified - Standard e-mail questionnaire: complete data available at 6 months. |

- North US travelers to Mexico in 2002 - Control group: none |

| Bacillary dysentery as a causative factor of irritable bowel syndrome and its pathogenesis. Wang et. al., 2004 |

- Adults - Lab proven IE or abdominal pain, diarrhea and rectal burning with leucocytes in the stools and cured with antibiotics |

- Functional bowel disease |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Phone interview or mailing; complete data available at 1–2 yrs F/up (single assessment). |

- Dysentery clinic 1998 - Control group: siblings or spouses of IE patients |

| The infectious intestinal disease study of England: a prospective evaluation of symptoms and health care use after an acute episode. Cumberland et. al., 2003 |

- Age (0–4 yr, 5–15 yr, > 16 yrs) - IE: loose stools or vomiting < 2w in the absence of non-infectious cause. 3 wk preceding symptom free |

- Not specified | - IBS excluded at baseline: Not specified - Mailed questionnaire; responded by 78% IE cases and 66% controls. |

- UK general practice databases - Control groups: sex and age match |

| Relative Importance of Enterochromaffin Cell Hyperplasia, Anxiety, and Depression in Postinfectious IBS. Dunlop et. al., 2003 |

- Age: 18–75 yr - Lab proven IE |

- Celiac disease, IBD (screening labs) |

- IBS excluded at baseline: yes - Standard questionnaires: 42% response rate; 38% eligible for analysis with complete data |

- Nottingham health authority 1999–2002 - Control group: none (for epidemiological analysis) |

| Post-traveler's diarrhea irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study. Ilnycckyj et al., 2003 |