Abstract

Introduction

Neurotoxicity induced by early developmental exposure to volatile anesthetics is a characteristic of organisms across a wide range of species, extending from the nematode C. elegans to mammals. Prevention of anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity (AIN) will rely upon an understanding of its underlying mechanisms. However, no forward genetic screens have been undertaken to identify the critical pathways affected in AIN. By characterizing such pathways, we may identify mechanisms to eliminate isoflurane induced AIN in mammals.

Methods

Chemotaxis in adult C. elegans after larval exposure to isoflurane was used to measure AIN. We initially compared changes in chemotaxis indices between classical mutants known to affect nervous system development adding mutants in response to data. Activation of specific genes was visualized using fluorescent markers. Animals were then treated with rapamycin or preconditioned with isoflurane to test effects on AIN.

Results

Forty-four mutations, as well as pharmacologic manipulations, identified two pathways, highly conserved from invertebrates to humans, that regulate AIN in C. elegans. Activation of one stress-protective pathway (DAF-2 dependent) eliminates AIN, while activation of a second stress-responsive pathway (endoplasmic reticulum (ER) associated stress) causes AIN. Pharmacologic inhibition of the mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) blocks ER-stress and AIN. Preconditioning with isoflurane prior to larval exposure also inhibited AIN.

Discussion

Our data are best explained by a model in which isoflurane acutely inhibits mitochondrial function causing activation of responses that ultimately lead to ER-stress. The neurotoxic effect of isoflurane can be completely prevented by manipulations at multiple points in the pathways that control this response. Endogenous signaling pathways can be recruited to protect organisms from the neurotoxic effects of isoflurane.

Introduction

Jevtovic-Todorovic et al. and and Young et al. demonstrated that commonly used anesthetics caused widespread apoptosis and neuronal degeneration in developing rat brains [1, 2]. These pathological changes were accompanied by a learning defect that persisted into adulthood in the rat. It is now established that, from nematodes [3] to rodents [1, 4, 5] and to primates [6, 7], volatile anesthetics in isolation are capable of inducing neurodegeneration in the developing nervous system [8–11]. It remains unclear how great a risk anesthetic exposure poses to the newborn human at clinical doses and lengths of time [9, 12, 13]. However, more than a million children undergo general anesthesia each year in the U.S. [14]; even rare developmental defects from their use during a critical window of vulnerability have potentially large implications for our current care of children. Since it is impossible to eliminate exposure of neonates to general anesthesia, it is critical that we develop a mechanistic understanding of the process in order to prevent anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity (AIN).

A potential productive approach to understand the mechanism of AIN is a genetic screen to detect the underlying molecular pathways that control its occurrence. In this manner, novel and otherwise unrecognized causes of AIN can be discovered and approaches to prevent AIN may be identified. Using changes in chemotaxis, we previously showed that early exposure to the volatile anesthetic isoflurane is neurotoxic to C. elegans [3]. Utilizing a genetic approach, we have identified two pathways, highly conserved from invertebrates to humans, that regulate AIN in the nematode, C. elegans. Identification of these novel interacting pathways allowed us to completely prevent AIN by genetic and pharmacologic interventions.

Materials and Methods

Strains

N2 Bristol, VC3201 atfs-1(gk3094) V, MT1522 ced-3(n717), MT2547 ced-4(n1162), MT5013 ced-10(n3246), MT1082 egl-1(n487), CB 845 unc-30(e191)IV, CB1338 mec-3(e1338)IV, CB1370 daf-2(e1370)III, CB3256 mab-5(e1751)III, CF1038 daf-16(mu86)I, CW532 gas-1(fc21)X, CX4 odr-7(ky4)X, CW859 daf-16(mu86);daf-2(e1370), CW860 daf-16(mu86);glr-1(n2461), GA187 sod-1(tm776)II, GA416 sod-4(gk101)III, GA503 sod-5(tm1146)II, GE24 pha-1(e2123)III, GS2477 arIs37 I;cup-5(ar465) III; dpy-20(e1282) IV, IK105 pkc-1(nj1)V, KG532 kin-2(ce179)X, KP4 glr-1(n2461)III, KU25 pmk-1(km25)IV, MC364 ire-1(ok799)II, MQ130 clk-1(qm30)III, MQ1333 nuo-6(qm200)I, MQ989 isp-1(qm150)IV, MR507 aak-2(rr48)X, MT1522 ced-3(n717)IV, MT1976 unc-86(n946)III, MT2246 egl-43(n1079)II, PY1589 cmk-1(oy21)IV, RB967 gcn-2(ok871)II (provided to the CGC by the C. elegans Gene Knockout Project at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation), SJ17 xbp-1(zc12)III;zcIs4 V, SJ4005 zcIs4[hsp-4::GFP]V, SJ4058 zcIs9[hsp-60::GFP]V, SJ4100 zcIs13[hsp-6::GFP]V, TJ356 zIs356[daf-16p::daf-16a/b::GFP + rol-6] IV, TK22 mev-1(kn1)III, TU282 lin-32(u282)X, VC1099 hsp-4(gk514)II, VC1722 skn-1(ok2315)IV/nT1 [qIs51](IV;V) (provided to the CGC by the C. elegans Gene Knockout Project at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation), VC433 sod-3(gk235)X, VC498 sod-2(gk257)I, CW645 sod-2(gk257);sod-3(gk235), VM487 nmr-1(ak4)II, and ZG31 hif-1(ia4)V were all obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, Minneapolis MN. gas-1(fc21) was isolated in our laboratory [15]. CW859 (daf-16;gir-1) and CW860 (daf-16;daf-2) were constructed by crossing daf-16(mu86) with CB164 dpy-17(e164) to make daf-16;dpy-17 before crossing into glr-1(n2461) or daf-2(1370) respectively. The resulting strains were allowed to self-fertilize to remove dpy-17. All mutations were confirmed by sequencing. All strains were grown as previously described on agar plates containing nematode growth media (NGM) with the E. coli strain OP50 as food [16].

Synchronization

For each assay, cohorts of worms were synchronized on 35mm NGM plates by limiting egg laying to 2–4 hours at 20°C and then grown for 20 hours at 15°C or 20°C as necessary to obtain newly hatched L1 animals. The plates of newly hatched L1 animals were either exposed to isoflurane as described below or held at 15°C to slow development to match the isoflurane exposed cohorts.

Isoflurane exposure

C. elegans L1 larvae were exposed to isoflurane at their clinical EC95 (~6.5% isoflurane) for four hours at 20°C beginning at 20 hours after being laid as eggs. Generally, these animals were at hours 4–8 of L1 development. Some mutants developed slowly, such that the time of isoflurane exposure was adjusted to approximate hours 4–8 of normal L1 development. Isoflurane concentration was checked by gas chromatography as previously described [17]. Control animals were kept in room air at 15°C during that hour to slow development to match isoflurane exposure. After exposure, experimental and control animals were cultured at 20°C and tested for chemotaxis 3–5 days later, depending on the mutant strain, on day one of adulthood.

Chemotaxis

Young adult worms were washed three times in chemotaxis buffer (5 mM potassium phosphate, 1 mM calcium chloride, and 1 mM magnesium sulfate) before being transferred in a minimal volume in the center of a 9cm NGM assay plate. The plates were divided into 3 regions in a modification of the technique described by Bargmann [3, 18]. One region contained an attractant (a 20ul spot of OP50) while the opposite region contained no attractant. The middle region served as the starting point for the animals. 2–3 plates of both control (unexposed) and exposed animals were assayed in parallel on a given day. Worms in each region were counted 1 hour after transfer. Scoring was done by an observer blinded to the exposure state of the strain but not to the strain being studied. A chemotaxis index (CI) was calculated using the formula: CI = 100×(worms at food side – worms at control side)/total. All results reported are new for this study (earlier results for N2, ced-3 and gas-1 were not included in this study).

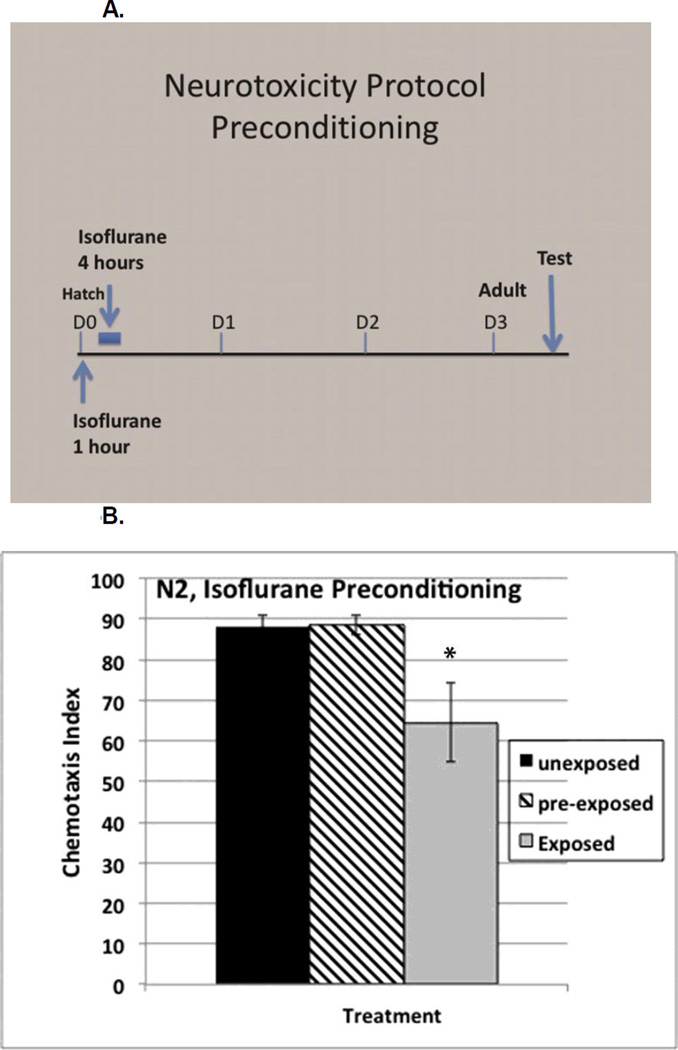

Isoflurane Preconditioning

Within one hour after hatching, synchronous L1s were exposed to 6.5% isoflurane for 1 hour, then allowed to recover for 3 hours, before being exposed to isoflurane as per the usual protocol. Control animals were kept in room air at 15°C during that hour (to slow development to match isoflurane exposure). They were tested as adults as described above in the chemotaxis experiments. All preconditioning assays were performed in duplicate for control and exposed animals.

Rapamycin

Rapamycin (LC laboratories) was dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 50 mg/ml and added to plate agar to 100uM with final DMSO concentration of 0.2% as described by Robida-Stubbs et al. [19]. Control plates contained 0.2% DMSO. Egg laying hermaphrodites were placed on rapamycin or DMSO plates, both with OP50, for 2 hours for synchonization, and then removed, as described above in Synchonization. Eggs were kept on rapamycin or DMSO plates until hatching and then exposed to isoflurane as L1s as described above. L1 animals were transferred to OP50 plates without rapamycin or DMSO the morning following isoflurane exposure, approximately 24 hours after hatching and 16 hours after isoflurane exposure.

Statistical Analysis

Chemotaxis indices (CIs) are the mean of 6–9 experiments (except for N2 where n=15) each containing >50 animals (total animals for each strain, 300–450, except N2, total >800). Errors for CI are reported as the standard errors of the mean (SEM). Changes in CI (ΔCI) between exposed and unexposed animals of a given genotype are calculated as the mean difference between the CI of the unexposed and the exposed animals. Error bars for ΔCI were calculated by combining the standard deviations (SD) of the CIs and then calculating the SEM from the SD. Values for ΔCI were compared by one-way ANOVA. If a significant difference was identified by ANOVA, then each mutant strain was compared to N2. Significance was defined as p<0.01.

Results

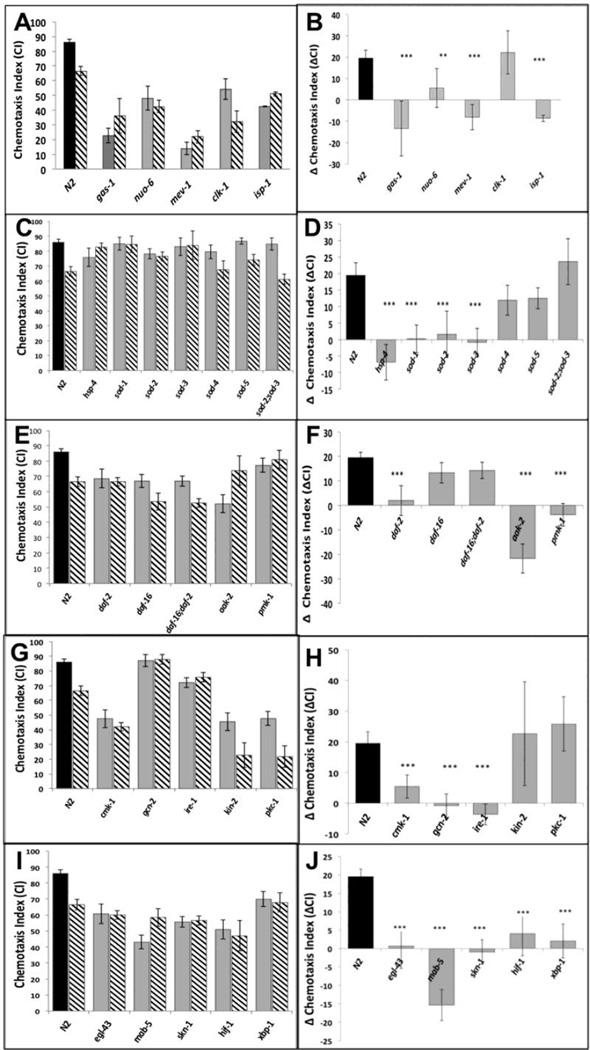

We compared the responses to isoflurane treatment of wildtype (N2) and 44 mutants that define different developmental pathways in C. elegans. The mutants were selected initially as those known to affect the nervous system and stress responses; ongoing results defined additional choices and refinements. For example, once the daf-2/daf-16 pathway was identified as a possible underlying mechanism (see below), daf-2 pathways that are independent of daf-16 were also studied. Animals that moved extremely poorly without anesthetic exposure were unable to be tested. The genes were then broadly grouped according to their function (Supplementary Figure S1). The chemotaxis indices (CIs) of the unexposed and isoflurane-exposed mutants that significantly contributed to evaluation of the pathways we discuss are shown in Figures 1A,C,E,G,I. The effect of each genotype is expressed as the change in the CI (ΔCI) between unexposed and exposed animals in Figures 1B,D,F,H,J.

Figure 1.

A,C,E,G,I. Chemotaxis indices (CIs) in adults after exposure to isoflurane as L1 larvae. Unexposed animals (solid fill), exposed animals (angled hatching). For all graphs, error bars denote SEM values, N>300 animals for each value. B,D,F,H,J Differences in CIs (ΔCI) between exposed and unexposed animals. Difference between ΔCI of N2 (19.5 +/− 3.7) and each mutant was compared to determine if the mutant affected AIN. ** = ΔCI different from N2, p<0.01, ***= ΔCI different from N2, p<0.005. A,B. Mitochondrial mutants. Chemotaxis in unexposed mitochondrial mutants (gas-1, nuo-6, mev-1, isp-1) was not worsened by isoflurane exposure. The exception was clk-1 which had a ΔCI similar to that of N2. C,D. ROS scavengers/ ER Stress. The effects of defects in ROS scavenging on AIN in C. elegans. CIs of five superoxide disumutatse mutants and hsp-4 (loss of the ER-specific heat shock protein HSP-4). E,F. DAF-2 dependent pathway. The effects of the daf-2 stress pathway on AIN. Loss of DAF-2 removed the AIN effect. The daf-16 mutation removed the effect of daf-2 on AIN. G,H. Kinases. Effects of 5 kinases on neurotoxicity. Loss of cmk-1 and gcn-2, both involved in innate immunity and ER-related stress, eliminated AIN. Loss of ire-1 also eliminated AIN and is discussed later. I,J. Transcription factors. The transcription factors skn-1, hif-1 and xpb-1 all eliminated AIN.

As reported previously [3], adult N2 exposed to isoflurane as L1 larvae did not move toward food as well as unexposed worms (ΔCI = 19.5 +/− 3.7; p=.00000008); no other defects in locomotion were noted in exposed animals. Since C. elegans is immobilized at higher doses of isoflurane than are mammals, we also tested a lower dose in the range of mammalian effective doses (2–2.5%). At these doses, the effect of isoflurane exposure on anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity (AIN) for N2 was similar to that at 6.5% (Supplemental Figure S2). To ensure that any mutation that eliminated AIN did so at the EC50 for N2, thereby insuring a robust effect, all subsequent studies were formed at 6.5% isoflurane. ΔCI was compared between mutants and N2. If a mutant had a ΔCI not significantly different from the N2 value, we interpreted the result as the same AIN response as N2. An animal resistant to the effect of isoflurane would have a ΔCI significantly less than that of N2, an indication of AIN inhibition.

Genes affecting Apoptosis

We confirmed our earlier report that loss of the apoptotic caspase, ced-3, eliminated the neurotoxic effects of isoflurane in C. elegans [3]; after exposure to isoflurane as larvae, adult ced-3 animals moved toward food as well as the unexposed animals (ΔCI (ced-3) = 6 +/− 9.7). As a further test of the role of apoptosis in AIN, we tested three other genes involved in the apoptotic pathway in C. elegans (Supplemental Figure S3). Loss of ced-4 (a cofactor of ced-3) or egl-1 (an activator of ced-4) also eliminated AIN (ΔCI (ced-4) = −2.4 +/− 10.9, p<0.01; ΔCI (egl-1) = 6.1 +/− 12, p<0.01)). However, loss of ced-10 (required for engulfing apoptotic cells rather than effecting apoptosis) did not suppress AIN, as its ΔCI was not different than that of N2 (ΔCI (ced-10) = 32.8 +/− 9.1). These results show that, in C. elegans, is a critical component of AIN.

Genes affecting Mitochondrial Function

Others have suggested that mitochondrial damage underlies at least part of AIN in rodents [20, 21], and that mitochondrial generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) initiates AIN [6, 22]. We tested whether mitochondrial mutants had any effect on AIN in C. elegans (Figure 1A,B). In general, mitochondrial mutations caused defects in chemotaxis in unexposed animals; however, the CI was either not worsened (ΔCI = app. 0) or improved by anesthetic exposure (a negative ΔCI). The one exception was clk-1, a long-lived mutant with defective Coenzyme Q synthesis [23] and endogenous protection from chronic ROS damage [24]. While unexposed clk-1 had a low CI, it responded to L1 isoflurane exposure similarly to N2. The ΔCIs for all mitochondrial mutants are shown in Figure 1B; clk-1 is the only mutant of this group with a ΔCI similar to that of N2.

Genes affecting ROS scavenging

To examine whether ROS scavenging plays a role in AIN, we tested mutations in superoxide dismutases (SODs) for their response to early anesthetic exposure (Figure 1C,D). Mutations in the rarely expressed extra-mitochondrial SODs, sod-4 or sod-5, did not change the ΔCI compared to wildtype, but loss of the primary cytoplasmic SOD, sod-1, lowered the ΔCI compared to N2. Knockout mutations in either mitochondrial SOD, sod-2 or sod-3, also suppressed the detrimental effect of isoflurane on chemotaxis. Surprisingly, the double mutant sod-2;sod-3 had a ΔCI similar to N2.

Genes in the DAF-2 (insulin growth factor receptor) pathway

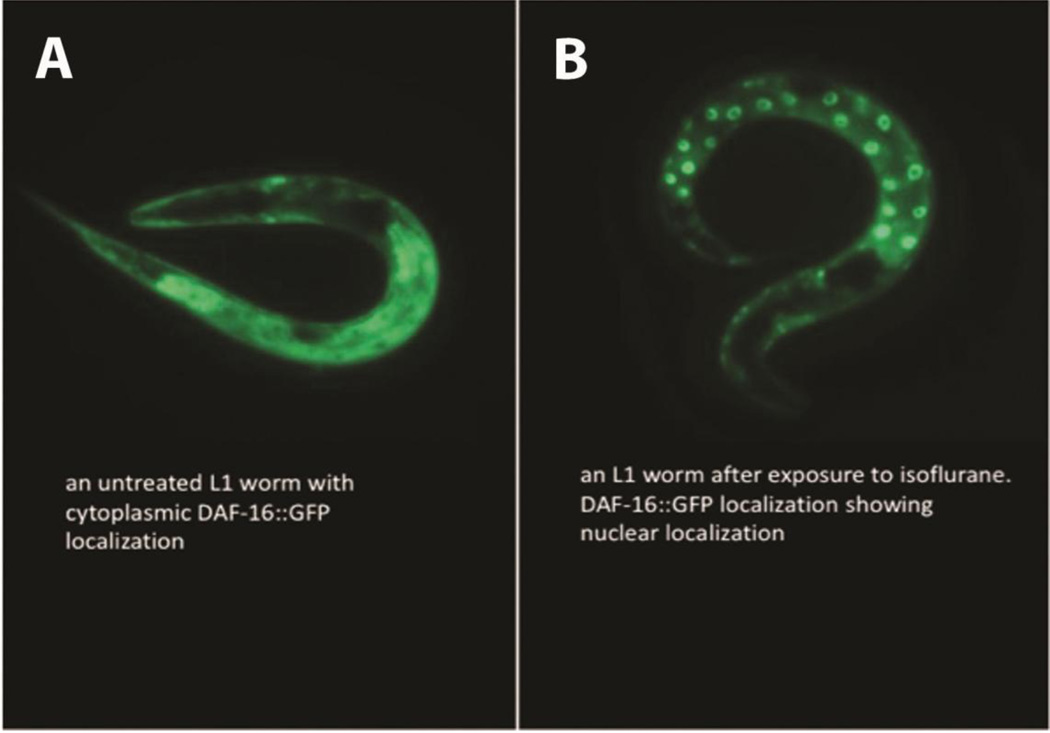

daf-2 encodes a kinase that is the C. elegans insulin growth factor receptor (IGFR) orthologue [25]. The functional DAF-2 protein inhibits initiation of a stress-response protective pathway that is mediated by the FOXO transcription factor, DAF-16. Loss of function of the insulin-like receptor, DAF-2, completely eliminated the ΔCI following isoflurane exposure (Figure 1E,F). In the absence of DAF-2, DAF-16 becomes localized to the nucleus and regulates longevity, fat metabolism, stress and innate immunity [26, 27]. Similarly, exposure to isoflurane causes nuclear localization of DAF-16 (Figure 2) within one hour after anesthetic exposure. If the loss of DAF-2 eliminates anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity by nuclear localization of DAF-16, then loss of DAF-16 should block the effect of DAF-2. daf-2;daf-16 had the same ΔCI as N2 and daf-16 alone (Figure 1F). Thus, the daf-2 effect on AIN is dependent on the presence of the DAF-16 protein.

Figure 2. Expression of an DAF-16::GFP fusion protein following exposure to isoflurane.

A. A GFP fusion protein with DAF-16 is distributed throughout the cytoplasm when not exposed to isoflurane. B. One hour after exposure to isoflurane, the DAF-16::GFP fusion protein is translocated to the nucleus. These results show that isoflurane exposure leads to nuclear localization of DAF-16 similar to mutations in either DAF-2 or GAS-1 [28, 29].

Genes affecting kinases independent of daf-16 function

Defects in DAF-2 also induce a stress protective response via a DAF-16 independent pathway. Loss of DAF-2 activates the kinase AAK-2 (AAK-2 is orthologous to AMPK in humans) that in turn activates the kinase, PMK-1 (orthologous to the human p38 MAPK). Activation of PMK-1 ultimately upregulates pathways of innate immunity and apoptosis [30, 31]. Somewhat surprisingly (since loss of DAF-2 should activate AAK-2 and PMK-1), mutations in either aak-2 or pmk-1 also eliminated the ΔCI (Figure 1E,F). However, both kinases (AAK-2 and PMK-1) are also known to mediate an ER-stress response by DAF-2 dependent and DAF-2 independent mechanisms [32, 33].

We tested 5 other kinases also known to affect stress responses in C. elegans (Figure 1G,H). Mutations in two kinases, CMK-1 (CaMK in humans) and GCN-2 (eIF2α kinase in humans) eliminated the neurotoxic effects of isoflurane exposure. GCN-2 primarily decreases protein translation by phosphorylation of eIF2α [34]; however, both GCN-2 and CMK-1 modulate the ER-stress response and apoptosis [35–37].

Genes affecting transcription Factors

We tested the effect of transcription factors known to affect stress responses or neuronal development in C. elegans [38–41]. Mutations in four transcription factors (skn-1, egl-43, mab-5, hif-1) eliminated the ΔCI of isoflurane exposure while maintaining the chemotactic response of the unexposed animals to at least 50% of that seen in N2 (Figure 1I.J). EGL-43 and MAB-5 are known to affect development of the sensory nervous system, here resulting in defective chemotaxis in the absence of isoflurane exposure [42, 43]. SKN-1 (Nrf2 in humans) and HIF-1 (hypoxia inducible factor) have well-defined interactions with other genes that affect neurotoxicity downstream of the effects of DAF-2 and DAF-16 (AAK-2 and PMK-1) [19, 44–46]. The SKN-1 pathway interacts with HIF-1 to mediate a stress response in the endoplasmic reticulum that is activated by mitochondrial ROS production [38, 39, 47, 48].

Genes affecting the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRMT)

The DAF-16-dependent effects of DAF-2 regulate multiple pathways, including those that operate in either mitochondria or endoplasmic reticulum [49, 50]. The unfolded protein response of mitochondria (UPRMT) is activated by two overlapping pathways, one requiring the transcription factor ATFS-1 and the second pathway requiring the protein kinase, GCN-2 [51]. Both ATFS-1 and GCN-2 ultimately induce production of the mitochondrial-specific heat shock proteins HSP-6 and HSP-60. Loss of HSP-6 and HSP-60 did not affect anesthetic induced neurotoxicity in C. elegans. In addition, neither Phsp-6::gfp nor Phsp-6::gfp were upregulated following isoflurane exposure (Data not shown). Loss of ATFS-1 did not change ΔCI (Supplemental Figure S1) but loss of the kinase GCN-2 eliminated ΔCI (Figure 1G,H).

Genes affecting the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response (UPRER)

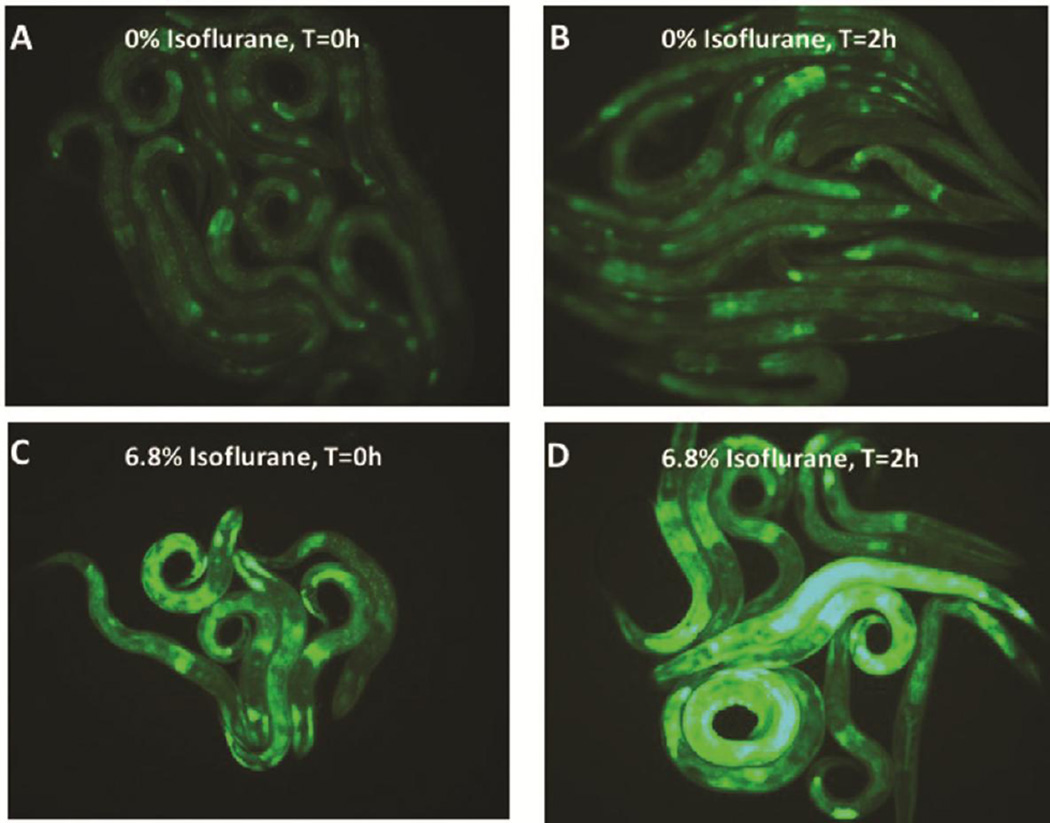

In response to stress DAF-2/DAF-16 and GCN-2 also regulate the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response [37, 50, 52], resulting in an upregulation of the ER-specific heat shock protein, HSP-4, one of two C. elegans heat shock proteins homologous to hsp70 proteins in mammals. To delineate the role of the ER stress response in AIN, we tested the mutants ire-1, xbp-1 and hsp-4. IRE-1 is a kinase and endoribonuclease that induces the ER stress response by splicing the mRNA of its downstream target, the transcription factor XBP-1 [53] which in turn upregulates expression of their downstream effector, HSP-4. The HSP-4 reporter (Phsp-4::gfp) was upregulated by larval isoflurane exposure at either the EC50 for immobility (6.5%) (Figure 3, quantification Supplemental Figure S4) or the lower dose also affecting chemotaxis (2.5%) (Supplemental Figure S5). Similar to loss of GCN-2, loss of IRE-1, XBP-1 or HSP-4 each eliminated AIN (Figures 1D,H,J). When Phsp-4::gfp was placed in xbp-1 or ire-1 mutants, induction of the reporter by isoflurane was completely inhibited (Supplemental Figure S6). In addition, the Phsp-4::gfp reporter was also inhibited by the mutation daf-2 (not shown) and by the mutant gcn-2 (Supplemental Figure S7). The inhibition by gcn-2 was restricted to isoflurane exposure during the L1 stage and was not true of heat shock which did induce hsp-4 in agreement with Baker et al. [51]

Figure 3. Expression of an HSP-4 reporter following exposure to isoflurane.

The ER specific heat shock protein HSP-4 reporter is upregulated by isoflurane exposure. A. HSP-4::GFP expression at t=0 hours (after removal from anesthetic chamber) without isoflurane exposure. B. HSP-4::GFP expression at t=2 hours (after removal from anesthetic chamber) without isoflurane exposure. C. HSP-4::GFP expression at t=0 (after removal from anesthetic chamber) after isoflurane exposure. D. HSP-4::GFP expression at t=2 hours (after removal from anesthetic chamber) with isoflurane exposure. Expression peaked at 2–3 hours and then slowly decayed (not shown). The reporters for mitochondrial UPR heat shock proteins (HSP-6 and HSP-60) were not upregulated by isoflurane exposure.

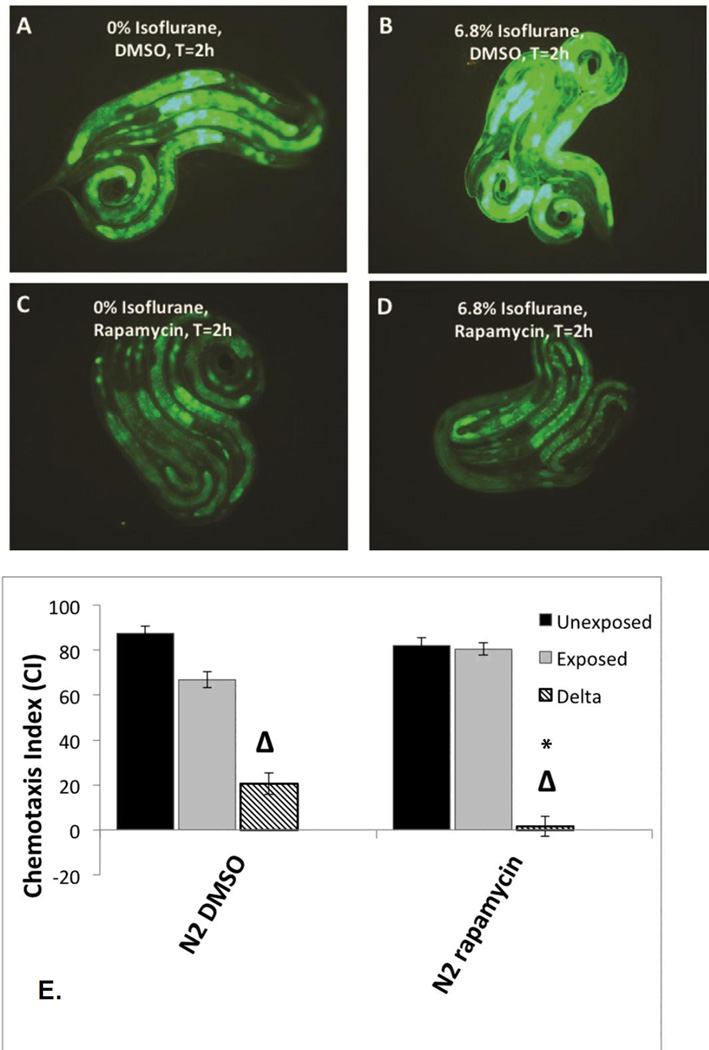

Effects of rapamycin

Both the daf-2 and ER-stress pathways interact with the nutrient sensing complex, the mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) [54, 55]. Prior studies have also indicated that isoflurane activates mTOR [56]. We therefore tested whether rapamycin, which inhibits mTOR, would have an effect on AIN. When nematodes containing Phsp-4::gfp were placed on rapamycin plates during the first day of life, induction of the reporter by isoflurane was inhibited (Figure 4A–D; quantification Supplemental Figure S8). Note that all plates had 0.2% DMSO on plates to facilitate uptake of rapamycin by the animals which moderately increased Phsp-4::gfp expression in the absence of isoflurane (compare Figure 4A with 3B). Treatment of nematodes during the first day of life (included the exposure to isoflurane) completely eliminated AIN as measured by chemotaxis (Figure 4E).

Figure 4. Phsp-4::gfp expression in L1 larvae with or without concurrent treatment with rapamycin and isoflurane.

A. Phsp-4::gfp expression at t=0 hours (after removal from anesthetic chamber) without isoflurane exposure. B. Phsp-4::gfp expression at t=2 hours (after removal from anesthetic chamber) with isoflurane exposure. C. Phsp-4::gfp expression at t=0 hours (after removal from anesthetic chamber) without isoflurane exposure with rapamycin treatment. D. Phsp-4::gfp expression at t=2 hours (after removal from anesthetic chamber) after 6.5% isoflurane exposure with rapamycin exposure. All plates had 0.2% DMSO on plates to facilitate uptake of rapamycin by the animals. The presence of DMSO mildly increased Phsp-4::gfp expression in the absence of isoflurane. E. Chemotaxis indices (CIs) in adults after exposure to isoflurane as L1 larvae during concurrent treatment with rapamycin. Unexposed animals (dark fill), exposed animals (light fill) and delta values (Δ) for control (left) and rapamycin (right) groups are shown. For all graphs, error bars denote SEM values, N>800 animals for each value. These results show that concurrent treatment with rapamycin completely inhibits AIN in C. elegans.

Preconditioning with isoflurane

The involvement of the daf-2 stress response and of gcn-2 in the neurotoxic effects of isoflurane caused us to question whether these changes were sensitive to preconditioning similar to the effects seen in hypoxic preconditioning for both genes [57, 58]. Exposure of wildtype L1 larvae to isoflurane for one hour, followed by recovery for 3 hours before re-exposure, (Figure 5A), completely reversed the neurotoxic effects of isoflurane, i.e. the ΔCI was eliminated (Figure 5B). We expected that the nuclear localization of DAF-16 seen with isoflurane (Figure 2) exposure would be necessary for the preconditioning effect. However, daf-16 mutants responded like N2 to preconditioning. This indicates that although isoflurane exposure does cause nuclear localization of DAF-16, successful preconditioning is not DAF-16 dependent. We also tested whether preconditioning inhibited the upregulation of hsp-4 by isoflurane and found that it did so (Supplemental Figure S8).

Figure 5.

A. Protocol timeline used to test for neurotoxicity and preconditioning in C. elegans. First stage larva (L1) are first exposed to isoflurane at their EC95 at age zero hours (arrow) and then again at four to eight hours (blue bar). They are then allowed to grow to adulthood (3 days for wildtype, D3). Chemotaxis is then tested as described in the methods and in Figure 1. B. Chemotaxis Index showing the neurotoxic effect in wildtype (N2) C. elegans following isoflurane exposure (black and gray bars). Preconditioning eliminated the neurotoxic effect caused by isoflurane (cross hatched bar). p value compares the difference between preconditioned animals and non-preconditioned animals exposed to isoflurane (cross hatched and gray bars). Error bars are SEM.

Discussion

AIN Pathways

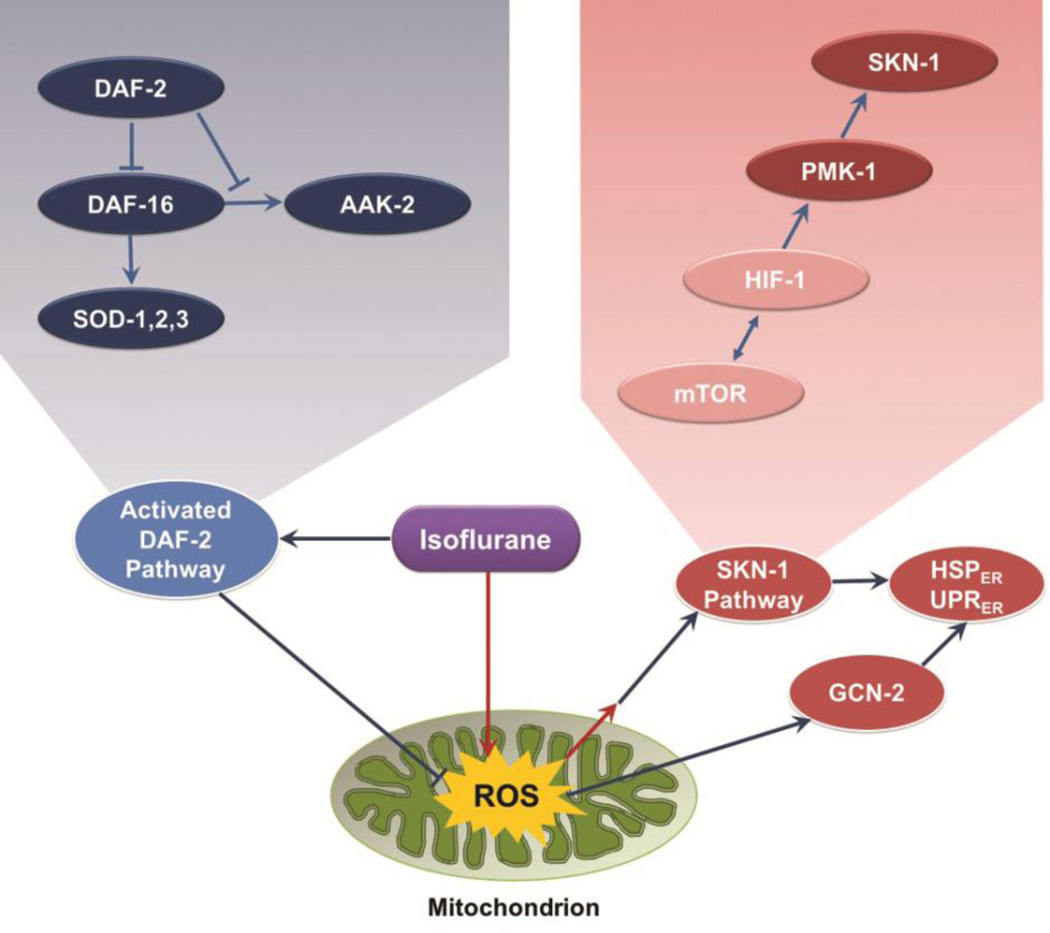

In C. elegans, exposure of L1 animals to isoflurane vastly upregulates expression of the HSP-4 reporter, a marker of ER stress. In addition, it causes translocation of DAF-16 to the nucleus, setting off a chain of events in a classic stress protective pathway. This apparent paradoxical set of responses is clarified by the genetic loss of key molecules in these two pathways. Loss of wild type products of multiple activators of ER stress, as well as loss of daf-2+, which induces movement of DAF-16 to the nucleus, completely blocks AIN. We interpret the data to show that these two pathways have opposing roles in AIN. If set in motion prior to the environmental stress of a VA, the daf-2 pathway is protective, and can compensate for the simultaneous activation of a neurotoxic response that is ultimately mediated by ER stress. We propose a model which explains all our data in Figure 6. Isoflurane induces the two highly conserved signaling pathways by inhibition of mitochondrial function, similar to their known responses to a variety of other environmental stresses like heat shock, caloric restriction, and hypoxia [52–54]. Others have shown that mitochondrial ROS plays an important role in AIN [22]. We propose that isoflurane inhibits mitochondrial dysfunction, which acutely increases ROS production. This in turn, activates the protective DAF-2 pathway depicted on the left of the figure in blue ovals. It also initiates a neurotoxic ER-stress pathway that is shown on the right in red ovals. The isoflurane target of mitochondria/ROS production is at the bottom in green.

Figure 6.

Two intersecting pathways that affect AIN in C. elegans. The grouping on the left of the figure (blue ellipses) represents the DAF-2 pathway which, when induced, is capable of inhibiting AIN. The genes on the right (red ellipses) are activated by ROS, leading to ER-stress, apoptosis and causing AIN. The mitochondrial/ROS isoflurane target is at the bottom in green. The pathways are expanded in the upper inserts.

AIN Induction- role of mitochondria

Boscolo et al. suggested that acute ROS generation causes AIN [20–22]. Isoflurane has been shown to inhibit mitochondrial function in nematodes and mammals [59–61], and been shown by others to increase mitochondrial ROS production [62, 63]. The unexposed mitochondrial mutants, other than clk-1, were significantly defective in chemotaxis, but did not worsen after isoflurane exposure as L1s. We interpret this finding to indicate that isoflurane and mitochondrial mutations are affecting behavior via the same pathway, inhibition of electron transport and increased ROS damage. A chronic increase in ROS damage, as seen in some mitochondrial mutants, can lead to ROS damage that results in a defect in chemotaxis. However, the mitochondrial mutants initiate a cascade of defense mechanisms in response to this chronic stress [64]. A similar rationale has been applied to the SOD mutants for their paradoxical effect of lengthening lifespan, interpreted as a low level of increased ROS signaling which induces a chronic protective response that improves health [65, 66]. This may position both mitochondrial and SOD mutants to be relatively immune to further damage from the brief increase in ROS generated by an acute exposure to isoflurane.

In contrast, clk-1, which has a severe defect in electron transport, responds to isoflurane exposure like N2. clk-1 is a unique mutant that accumulates less ROS damage to mitochondrial protein than N2 despite producing increased ROS [24, 67]. Increased scavenging by an intermediate in CoQ synthesis is proposed to be responsible for this remarkable lack of chronic ROS damage [24, 68]. Taken together, the simplest explanation of our data is that anesthetics inhibit mitochondria at a critical point in development, generating an acute increase in ROS signaling that ultimately transduces neurotoxicity in the adult C. elegans. clk-1 does not accumulate chronic ROS damage and, like N2, is unable to sufficiently scavenge acute isoflurane induced ROS production to avoid AIN. We conclude that acute mitochondrial inhibition by isoflurane induces AIN by increased ROS production in agreement with Jevtovic-Todorovic and colleagues [20–22].

ER-Stress

Isoflurane exposure induces a striking upregulation of HSP-4, with no effects on HSP-6 or HSP-60 expression. AIN is eliminated when hsp-4 is lost, but there is no effect of loss of hsp-6 or hsp-60. Coupled with the results of others [62, 63], we conclude that the acute increase in ROS signaling by isoflurane must exert its AIN effects outside the mitochondrion. This sets in motion multiple responses that contribute to AIN, including activation of aak-2, pmk-1, skn-1, hif-1, and gcn-2, discussed below. These genes have multiple, sometimes opposing effects on ER-stress [69]. The end result of their activation is a clear increase in expression of UPRER and ER-stress. Since activation of IRE-1, XBP-1 and HSP-4 are components of the final pathway activating ER-stress, downstream from HIF-1 and SKN-1, and their losses each eliminate AIN, the UPRER apparently causes AIN. Prior studies in mammals have also indicated that ER-stress plays a role in AIN in both young and old [70–73]; these studies clarify the mechanisms by which isoflurane induces that response. Inhibition of ROS-induced components of ER-stress eliminates AIN.

Linking an acute increase in ROS signaling to a neurologic defect following isoflurane exposure is unquestionably complicated. Transient mitochondrial ROS production activates PMK-1, SKN-1 [48] and HIF-1 [74] and the loss of PMK-1, SKN-1, HIF-1 and GCN-2 all eliminated AIN. PMK-1 can induce apoptosis directly [75] or by phosphorylation of SKN-1, resulting in its translocation to the nucleus [76]. While SKN-1 is usually considered to improve response to stress, its activation has also been shown to result in defects in neuromuscular function [77, 78] by altering expression of the synaptic cell adhesion molecule, neuroligin. Given these activities, loss of either PMK-1 or SKN-1 could play a role in protecting animals from the neurotoxic effects of isoflurane. Activation of HIF-1 by isoflurane has been shown to play a role in AIN and anesthetic-induced preconditioning [79–81] and to be activated by inhibition of mitochondrial respiration and ROS production [82]. We conclude that developmental stage-specific isoflurane exposure inappropriately activates HIF-1, resulting in activation of ER-stress. Loss of GCN-2 also eliminated the neurotoxic effects of isoflurane. Activated GCN-2 phosphorylates the cytosolic translation initiation factor, eIF2α, decreasing protein translation to restore homeostasis during times of cellular stress [34]. GCN-2 is activated by ROS formation and contributes to activation of both the UPRMT and the UPRER [51, 58]. Since we detected no increase in UPRMT, it appears that under these conditions GCN-2 primarily activates the UPRER.

Finally, removing the ER chaperone protein HSP-4 eliminates AIN, indicating that HSP-4 levels are detrimentally upregulated by isoflurane beyond what is necessary for cellular homeostasis. Since loss of GCN-2 should increase protein translation, such an increase may be necessary to alleviate the effects of an increase in the UPRER. Further studies to determine if HSP-4 levels are dependent on gcn-2 following isoflurane exposure will help indicate the precise step at which isoflurane is exerting its effect on the UPRER.

DAF-2

If the far-reaching DAF-2 stress response is in place prior to the acute increase in ROS signaling caused by isoflurane exposure, the effects of mitochondrial inhibition by isoflurane are eliminated. This protective pathway is DAF-16-dependent. In contrast to molecules whose activation contributes to AIN, this protective pathway is induced by DAF-16-dependent loss of DAF-2 [29, 83]. Nuclear translocation of DAF-16 protects mitochondria and the cell from ROS damage by induction of superoxide dismutases and catalases, as well as other protective mechanisms [83, 84]. We expected that the preconditioning we observed with a brief exposure to isoflurane prior to the neurotoxic dose would activate stress protective pathways in a manner similar to genetic loss of daf-2. However, since preconditioning was seen in the daf-16 mutant, e.g. is daf-16 independent, other, yet unidentified mechanisms, also are at play.

Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR)

Interestingly, both DAF-2 and ER-stress pathways interact with the nutrient sensing complex, mTOR, which has been shown to be activated by isoflurane [56] and ROS. mTOR broadly controls the metabolic state of cells [69]. Since rapamycin completely eliminates AIN and blunts expression of hsp-4, our data indicate that mTOR plays a central role in transducing AIN. This is consistent with a model in which an increase in ROS production, caused by isoflurane, activates mTOR directly, thus modulating the metabolic state of the cell, and upregulating ER-stress. mTOR may also connect the two pathways in Figure 6, representing a direction for future studies and a mechanism amenable to treatment. Our immediate plans are to characterize other markers of mTOR activation and ROS production along with determining functional changes in the nervous system of C. elegans following isoflurane exposure.

Summary

We have identified highly conserved pathways that regulate AIN in C. elegans. Our data are best explained by a model in which isoflurane acutely increases ROS signaling by inhibiting mitochondrial function and activates mTOR. This results in activation of responses that ultimately lead to ER-stress. Defense mechanisms can be put in place by a preconditioning dose of isoflurane, mTOR inhibition, activation of a stress protective pathway or inhibition of the ER-stress pathway. We have shown that it is possible to recruit endogenous stress pathways to protect the organism from the neurotoxic effects of isoflurane.

Supplementary Material

Summary Statement.

Two highly conserved pathways regulate isoflurane induced neurotoxicity in C. elegans. The data are best explained by a model in which isoflurane acutely activates the mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) resulting in activation of responses that lead to endoplasmic reticulum related stress and cell death.

Highlights.

DAF-2 pathway inhibits anesthetic induced neurotoxicity (AIN)

ER-stress controls AIN

Inhibition of mTOR with rapamycin blocks AIN

Preconditioning with isoflurane blocks AIN

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: This work was supported in part by NIH grant R21 DK089356.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest. None

Reference List

- 1.Jevtovic-Todorovic V, et al. Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. J Neurosci. 2003;23(3):876–882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00876.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young C, et al. Potential of ketamine and midazolam, individually or in combination, to induce apoptotic neurodegeneration in the infant mouse brain. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146(2):189–197. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gentry KR, et al. Early developmental exposure to volatile anesthetics causes behavioral defects in Caenorhabditis elegans. Anesth Analg. 2013;116(1):185–189. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31826d37c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu LX, et al. General anesthesia activates BDNF-dependent neuroapoptosis in the developing rat brain. Apoptosis. 2006;11(9):1603–1615. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-8762-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yon JH, et al. Anesthesia induces neuronal cell death in the developing rat brain via the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways. Neuroscience. 2005;135(3):815–827. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Creeley C, et al. Propofol-induced apoptosis of neurones and oligodendrocytes in fetal and neonatal rhesus macaque brain. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110(Suppl 1):i29–i38. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsen EA, Brambrink AM. Anesthetic neurotoxicity in the newborn and infant. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2013;26(5):535–542. doi: 10.1097/01.aco.0000433061.59939.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jevtovic-Todorovic V. General anesthetics and the developing brain: friends or foes? J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2005;17(4):204–206. doi: 10.1097/01.ana.0000178111.26972.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rappaport BA, et al. Anesthetic neurotoxicity--clinical implications of animal models. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):796–797. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1414786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin LD, et al. Effects of anesthesia with isoflurane, ketamine, or propofol on physiologic parameters in neonatal rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2014;53(3):290–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creeley CE, et al. Isoflurane-induced apoptosis of neurons and oligodendrocytes in the fetal rhesus macaque brain. Anesthesiology. 2014;120(3):626–638. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiMaggio C, et al. A retrospective cohort study of the association of anesthesia and hernia repair surgery with behavioral and developmental disorders in young children. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2009;21(4):286–291. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e3181a71f11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen TG. Anesthesia-related neurotoxicity and the developing animal brain is not a significant problem in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2015;25(1):65–72. doi: 10.1111/pan.12548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabbitts JA, et al. Epidemiology of ambulatory anesthesia for children in the United States: 2006 and 1996. Anesth Analg. 2010;111(4):1011–1015. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181ee8479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kayser EB, et al. Mitochondrial expression and function of GAS-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(23):20551–20558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77(1):71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgan PG, Sedensky M, Meneely PM. Multiple sites of action of volatile anesthetics in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(8):2965–2969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.8.2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bargmann CI, Horvitz HR. Chemosensory neurons with overlapping functions direct chemotaxis to multiple chemicals in C. elegans. Neuron. 1991;7(5):729–742. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90276-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robida-Stubbs S, et al. TOR signaling and rapamycin influence longevity by regulating SKN-1/Nrf and DAF-16/FoxO. Cell Metab. 2012;15(5):713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boscolo A, et al. Early exposure to general anesthesia disturbs mitochondrial fission and fusion in the developing rat brain. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(5):1086–1097. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318289bc9b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boscolo A, et al. Mitochondrial protectant pramipexole prevents sex-specific long-term cognitive impairment from early anaesthesia exposure in rats. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110(Suppl 1):i47–i52. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boscolo A, et al. The abolishment of anesthesia-induced cognitive impairment by timely protection of mitochondria in the developing rat brain: the importance of free oxygen radicals and mitochondrial integrity. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;45(3):1031–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ewbank JJ, et al. Structural and functional conservation of the Caenorhabditis elegans timing gene clk-1. Science. 1997;275(5302):980–983. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang YY, et al. The effect of different ubiquinones on lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2009;130(6):370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimura KD, et al. daf-2, an insulin receptor-like gene that regulates longevity and diapause in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1997;277(5328):942–946. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinha A, Rae R. A functional genomic screen for evolutionarily conserved genes required for lifespan and immunity in germline-deficient C. elegans. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e101970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin K, et al. Regulation of the Caenorhabditis elegans longevity protein DAF-16 by insulin/IGF-1 and germline signaling. Nat Genet. 2001;28(2):139–145. doi: 10.1038/88850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kondo M, et al. Effect of oxidative stress on translocation of DAF-16 in oxygen-sensitive mutants, mev-1 and gas-1 of Caenorhabditis elegans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126(6–7):637–641. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henderson ST, Johnson TE. daf-16 integrates developmental and environmental inputs to mediate aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2001;11(24):1975–1980. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shivers RP, et al. Phosphorylation of the conserved transcription factor ATF-7 by PMK-1 p38 MAPK regulates innate immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(4):e1000892. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richardson CE, Kooistra T, Kim DH. An essential role for XBP-1 in host protection against immune activation in C. elegans. Nature. 2010;463(7284):1092–1095. doi: 10.1038/nature08762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan Y, et al. Dysregulated LRRK2 signaling in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress leads to dopaminergic neuron degeneration in C. elegans. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e22354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zarse K, et al. Impaired insulin/IGF1 signaling extends life span by promoting mitochondrial L-proline catabolism to induce a transient ROS signal. Cell Metab. 2012;15(4):451–465. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castilho BA, et al. Keeping the eIF2 alpha kinase Gcn2 in check. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843(9):1948–1968. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gentz SH, et al. Implication of eIF2alpha kinase GCN2 in induction of apoptosis and endoplasmic reticulum stress-responsive genes by sodium salicylate. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2013;65(3):430–440. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Volmer R, van der Ploeg K, Ron D. Membrane lipid saturation activates endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response transducers through their transmembrane domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(12):4628–4633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217611110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donnelly N, et al. The eIF2alpha kinases: their structures and functions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(19):3493–3511. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1252-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leiser SF, et al. Life-span extension from hypoxia in Caenorhabditis elegans requires both HIF-1 and DAF-16 and is antagonized by SKN-1. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(10):1135–1144. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller DL, Budde MW, Roth MB. HIF-1 and SKN-1 coordinate the transcriptional response to hydrogen sulfide in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e25476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garriga G, Guenther C, Horvitz HR. Migrations of the Caenorhabditis elegans HSNs are regulated by egl-43, a gene encoding two zinc finger proteins. Genes Dev. 1993;7(11):2097–2109. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.11.2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Josephson MP, et al. EGL-20/Wnt and MAB-5/Hox Act Sequentially to Inhibit Anterior Migration of Neuroblasts in C. elegans. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris J, et al. Neuronal cell migration in C. elegans: regulation of Hox gene expression and cell position. Development. 1996;122(10):3117–3131. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baum PD, et al. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene ham-2 links Hox patterning to migration of the HSN motor neuron. Genes Dev. 1999;13(4):472–483. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.4.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paek J, et al. Mitochondrial SKN-1/Nrf mediates a conserved starvation response. Cell Metab. 2012;16(4):526–537. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoeven R, et al. Ce-Duox1/BLI-3 generated reactive oxygen species trigger protective SKN-1 activity via p38 MAPK signaling during infection in C. elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(12):e1002453. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kell A, et al. Activation of SKN-1 by novel kinases in Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43(11):1560–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhuang Z, et al. Adverse effects from clenbuterol and ractopamine on nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and the underlying mechanism. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85482. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmeisser S, et al. Neuronal ROS signaling rather than AMPK/sirtuin-mediated energy sensing links dietary restriction to lifespan extension. Mol Metab. 2013;2(2):92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brys K, et al. Disruption of insulin signalling preserves bioenergetic competence of mitochondria in ageing Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Biol. 2010;8:91. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Henis-Korenblit S, et al. Insulin/IGF-1 signaling mutants reprogram ER stress response regulators to promote longevity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(21):9730–9735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002575107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baker BM, et al. Protective coupling of mitochondrial function and protein synthesis via the eIF2alpha kinase GCN-2. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(6):e1002760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Safra M, et al. The FOXO transcription factor DAF-16 bypasses ire-1 requirement to promote endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2014;20(5):870–881. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shen X, et al. Complementary signaling pathways regulate the unfolded protein response and are required for C. elegans development. Cell. 2001;107(7):893–903. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00612-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wolpin BM, et al. Oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in patients with gemcitabine-refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(2):193–198. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.9514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Endo H, et al. Activation of insulin-like growth factor signaling induces apoptotic cell death under prolonged hypoxia by enhancing endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Cancer Res. 2007;67(17):8095–8103. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun Y, et al. Isoflurane preconditioning increases survival of rat skin random-pattern flaps by induction of HIF-1alpha expression. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2013;31(4–5):579–591. doi: 10.1159/000350078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.LaRue BL, Padilla PA. Environmental and genetic preconditioning for long-term anoxia responses requires AMPK in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e16790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mao XR, Crowder CM. Protein misfolding induces hypoxic preconditioning via a subset of the unfolded protein response machinery. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(21):5033–5042. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00922-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kayser EB, et al. Isoflurane selectively inhibits distal mitochondrial complex I in Caenorhabditis elegans. Anesth Analg. 2011;112(6):1321–1329. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182121d37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Harris RA, et al. Action of halothane upon mitochondrial respiration. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1971;142(2):435–444. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(71)90507-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cohen PJ. Effect of anesthetics on mitochondrial function. Anesthesiology. 1973;39(2):153–164. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197308000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun Y, et al. Time-Dependent Effects of Anesthetic Isoflurane on Reactive Oxygen Species Levels in HEK-293 Cells. Brain Sci. 2014;4(2):311–320. doi: 10.3390/brainsci4020311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hirata N, et al. Isoflurane differentially modulates mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production via forward versus reverse electron transport flow: implications for preconditioning. Anesthesiology. 2011;115(3):531–540. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31822a2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suthammarak W, et al. Novel interactions between mitochondrial superoxide dismutases and the electron transport chain. Aging Cell. 2013;12(6):1132–1140. doi: 10.1111/acel.12144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van Raamsdonk JM, Hekimi S. Deletion of the mitochondrial superoxide dismutase sod-2 extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(2):e1000361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hekimi S, Lapointe J, Wen Y. Taking a "good" look at free radicals in the aging process. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21(10):569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kayser EB, Sedensky MM, Morgan PG. The effects of complex I function and oxidative damage on lifespan and anesthetic sensitivity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125(6):455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang YY, et al. The role of DMQ(9) in the long-lived mutant clk-1. Mech Ageing Dev. 2011;132(6–7):331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Johnson SC, Rabinovitch PS, Kaeberlein M. mTOR is a key modulator of ageing and age-related disease. Nature. 2013;493(7432):338–345. doi: 10.1038/nature11861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ge HW, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway mediates isoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis and cognitive impairments in aged rats. Physiol Behav. 2015;151:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Komita M, Jin H, Aoe T. The effect of endoplasmic reticulum stress on neurotoxicity caused by inhaled anesthetics. Anesth Analg. 2013;117(5):1197–1204. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182a74773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang H, et al. Isoflurane induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and caspase activation through ryanodine receptors. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113(4):695–707. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen G, et al. Sevoflurane induces endoplasmic reticulum stress mediated apoptosis in hippocampal neurons of aging rats. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e57870. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nanduri J, et al. HIF-1alpha activation by intermittent hypoxia requires NADPH oxidase stimulation by xanthine oxidase. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aballay A, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans innate immune response triggered by Salmonella enterica requires intact LPS and is mediated by a MAPK signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2003;13(1):47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01396-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Inoue H, et al. The C. elegans p38 MAPK pathway regulates nuclear localization of the transcription factor SKN-1 in oxidative stress response. Genes Dev. 2005;19(19):2278–2283. doi: 10.1101/gad.1324805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Staab TA, et al. The conserved SKN-1/Nrf2 stress response pathway regulates synaptic function in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(3):e1003354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Staab TA, et al. Regulation of synaptic nlg-1/neuroligin abundance by the skn-1/Nrf stress response pathway protects against oxidative stress. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(1):e1004100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Appenzeller-Herzog C, Hall MN. Bidirectional crosstalk between endoplasmic reticulum stress and mTOR signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22(5):274–282. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Raphael J, et al. Isoflurane preconditioning decreases myocardial infarction in rabbits via up-regulation of hypoxia inducible factor 1 that is mediated by mammalian target of rapamycin. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(3):415–425. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318164cab1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jiang H, et al. Hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha is involved in the neurodegeneration induced by isoflurane in the brain of neonatal rats. J Neurochem. 2012;120(3):453–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee SJ, Hwang AB, Kenyon C. Inhibition of respiration extends C. elegans life span via reactive oxygen species that increase HIF-1 activity. Curr Biol. 2010;20(23):2131–2136. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kenyon C. My adventures with genes from the fountain of youth. Harvey Lect. 2004;100:29–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gems D, Partridge L. Genetics of longevity in model organisms: debates and paradigm shifts. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:621–644. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.