Abstract

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are ubiquitous environmental toxicants known to adversely impact human health. Ortho-substituted PCBs affect the nervous system, including the brain dopaminergic system. The reinforcing effects of psychostimulants are typically modulated via the dopaminergic system, so this study used a preclinical (i.e., rodent) model to evaluate whether developmental contaminant exposure altered intravenous self-administration (i.v. SA) for the psychostimulant cocaine. Long Evans rats were perinatally exposed to 6 or 3 mg/kg/day of PCBs throughout gestation and lactation and compared to non-exposed controls. Rats were trained to lever press for a food reinforcer in an operant chamber under a fixed-ratio 5 (FR5) schedule and later underwent jugular catheterization. Food reinforcers were switched for infusions of 250 μg of cocaine, but the response requirement to earn the reinforcer remained. Active lever presses and infusions were higher in males during response acquisition and maintenance. The same sex effect was observed during later sessions which evaluated responding for cocaine doses ranging from 31.25 – 500 μg. PCB-exposed males (not females) exhibited an increase in cocaine infusions (with a similar trend in active lever presses) during acquisition, but no PCB-related differences were observed during maintenance, examination of the cocaine dose-response relationship, or progressive ratio sessions. Overall, these results indicated perinatal PCB exposure enhanced early cocaine drug-seeking in this preclinical model of developmental contaminant exposure (particularly the males), but no differences were seen during later cocaine SA sessions. As such, additional questions regarding substance abuse proclivity may be warranted in epidemiological studies evaluating environmental contaminant exposures.

Keywords: behavioral neurotoxicology, psychostimulant abuse, fetal basis of adult disease

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are ubiquitous environmental toxicants that adversely impact human health. There are thousands of chemicals suspected to be neurotoxicants but only a small fraction (including PCBs) have been studied well enough to be confirmed neurotoxic to human development (Grandjean & Landrigan, 2006). This is alarming given the emerging and converging evidence suggesting environmental contaminants may be playing a role in the increasing number of developmental and neurological disorders observed in the United States population over the last 30 years (CDC, 2005; Schieve et al., 2010; Winneke, 2011). These studies have often focused on the parallels between the behavioral outcomes of developmental contaminant exposure to those observed in neuropsychiatric disorders including anxiety disorders (Inadera, 2015), depression (London, Flisher, Wesseling, Mergler, & Kromhout, 2005), ADHD (Eubig, Aguiar, & Schantz, 2010; Vrijheid, Casas, Gascon, Valvi, & Nieuwenhuijsen, 2016), and autism (Rossignol, Genuis, & Frye, 2014).

While previous research has been able to show that developmental contaminant exposure impacts executive functions associated with addictive behavior including inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, and working memory (Boucher et al., 2014; Newland, Hoffman, Heath, & Donlin, 2013; Reed, Banna, Donlin, & Newland, 2008; Sable & Schantz, 2006), few studies have directly examined the impact that developmental chemical exposure has on the propensity for substance abuse later in life. Developmental PCB exposure in rats has been shown to produce alterations in the dopamine system that persist into adulthood. The reinforcing effects of psychostimulants are typically modulated (at least in part) via the dopaminergic system, so this study used a preclinical (i.e., animal) model to evaluate whether early developmental contaminant exposure altered intravenous self-administration (i.v. SA) for the psychostimulant cocaine later in life.

We have previously demonstrated that rats perinatally exposed to PCBs exhibit alterations in behavior following experimenter-administered cocaine and amphetamine. Adult rats perinatally exposed to PCBs were more sensitive to the interoceptive cues of cocaine, but less sensitive to the interoceptive effects of amphetamine as measured in a drug discrimination paradigm (Sable, Monaikul, Poon, Eubig, & Schantz, 2011). Compared to non-exposed controls, rats perinatally exposed to PCBs exhibited greater locomotor activation an initial injection of amphetamine (0.5 mg/kg IP), but overall amphetamine behavioral sensitization following repeated injections was attenuated compared to the non-exposed controls (Poon et al., 2013). With cocaine (10.0 mg/kg IP), rats exposed to PCBs again exhibited greater locomotor activation to the initial injection. However, unlike the attenuation seen for amphetamine, behavioral sensitization for cocaine occurred earlier in PCB-exposed animals, but the overall degree of locomotor sensitization looked similar across exposure groups (unpublished results). The difference in behavioral sensitization for PCB-exposed rats following repeated psychostimulant injections appear to be tied to differences in dopamine neurotransmission. Compared to non-exposed controls, rats perinatally exposed to PCBs exhibited enhanced stimulated peak dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens core following a single injection of 20 mg/kg IP cocaine. While control animals exhibited a significant increase in stimulated dopamine release following repeated injections of the same dose of cocaine (an effect tied to dopamine sensitization), stimulated peak dopamine release in the PCB-exposed rats was attenuated following repeated cocaine administration.

Overall, these studies indicate perinatal PCB exposure modifies dopamine synaptic transmission in a manner that may alter the reinforcing effects of psychostimulants. However, these studies demonstrate differences in the interoceptive and locomotor-activating effects of experimenter-administered psychostimulants in perinatally PCB-exposed animals, but did not measure psychostimulant reinforcement per se. Thus, this project looked at the effects of perinatal PCB exposure on adult cocaine i.v. SA in order to determine if PCB-related dopamine dysfunction led to a greater propensity to self-administer cocaine. It was hypothesized that PCB-exposed rats would a) reach the pre-set criterion marking the acquisition of cocaine SA in fewer sessions, b) self-administer more cocaine and press the lever more during maintenance SA sessions, c) show a greater sensitivity to cocaine (i.e., respond more at lower cocaine doses), and d) work harder to self-administer cocaine in comparison to non-exposed control rats (i.e., show a higher progressive ratio breakpoint).

Method

Subjects

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Memphis and were in accordance with the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH, 2002) and the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research (National Research Council, 2003). Thirty-eight nulliparous female Long-Evans rats (Harlan Barrier 202A, Indianapolis, IN; 11–14 dams/PCB-exposure group) were used. All rats were maintained in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room (22° C, 40–55% humidity) on a 12-hr light/dark cycle (lights on 0800) and were housed in a standard rat shoebox cage containing Harlan Teklad Laboratory Grade Sani-Chip bedding. All rats were given water ad libitum and fed a diet of Harlan Teklad 2020X. This standard feed is a high-protein, low phytoestrogen diet which helped maintain overall rodent health and ensured that pregnant females were able to support their litters.

Exposure and breeding

Upon arrival, each female was weighed and given an undosed vanilla wafer cookie to acclimate it to eating this novel food item. The female rats were then divided into one of the three PCB dose groups which were counterbalanced for body weight. Dosing procedures were identical to those used by Sable et al. (2006, 2009, 2011). The stock solution of the Fox River PCB mixture (see Kostyniak et al., 2005) was diluted with corn oil to make two dosing solutions and a control: 0 μl/ml PCBs (corn oil only), 7.5 μl/ml PCBs, and 15.0 μl/ml PCBs. The concentration of PCBs in each dosing solution was verified via capillary column gas chromatography with electron capture detection (GC/ECD) prior to dosing. The dosing solutions were pipetted onto a vanilla wafer cookie at a volume of 0.4 mL/kg (based on daily body weight of the dam) to yield final doses of 0, 3, and 6 mg/kg/day, thereby establishing the three dosing groups. The females were exposed to PCB laced cookies starting 28 days prior to breeding and continuing throughout gestation and lactation until postnatal day 21 when weaning of offspring occurred. offspring exposed to the doses used in our study weighed less than control pups at birth and at weaning (Kostyniak et al., 2005) and showed deficits in inhibitory control (Sable et al., 2009). Subtle reductions in birth weight and postnatal growth as well as deficits in inhibitory control have also been reported in children born to PCB-exposed mothers (Fein et al., 1984; Jacobson and Jacobson, 2003; Jacobson et al., 1990; Stewart et al., 2006). For breeding, the females were paired with an unexposed Long-Evans male rat (Harlan barrier 202A). Breeding pairs remained together for eight days, with the female being removed for PCB dosing daily as previously described. After breeding, the females continued to be dosed throughout gestation (roughly twenty-one days) and lactation (twenty-one days). Thus, the offspring of each dam were exposed to PCBs during both gestation and lactation.

Weaning

At weaning, the dam and a male/female pair from each litter were sacrificed to determine physiological and histological measures of toxicity. These outcomes were similar to those previously reported that used the same PCB mixture (Kostyniak et al., 2005; Sable, Eubig, Powers, Wang, & Schantz, 2009). In each litter, one female and one male were tested for cocaine i.v. SA as described below such that the number of males and females tested within each PCB exposure group was equal. As attrition is often inherent in i.v. SA studies, a second male/female pair was retained at weaning but only underwent catheterization surgery when such cases of attrition occurred (<1 animal/exposure group/sex). The weaned pups were moved to another room (also temperature- and humidity-controlled: 22° C, 40–55% humidity) and paired or triple-housed according to cohort, exposure group, and gender until PND 90. The offspring were kept on a 14-hr light and 10-hr dark cycle (on at 0800, off at 2200).

Apparatus

Behavioral testing was conducted in 10 automated operant testing chambers (Med Associates; St. Albans, VT). These chambers were both sound attenuated and well ventilated with a fan. On one wall of the chamber, there was a food magazine tray positioned in the middle with two retractable response levers symmetrically aligned on each side of the tray. Each response lever had a cue light above it and was 7 cm from the floor and 5.7 cm from the midline of the wall. A house light was situated on the wall opposite of the levers. A drug-infusion pump (SAI Infusion Technologies, CA) was used for cocaine drug-delivery. All operant programs were controlled via a PC equipped with Med–PC IV software (Med Associates).

Surgery

Upon completion of fixed-ratio training, rats underwent catheterization surgery at approximately PND 120–180. Intravenous silicone catheters with adjustable suture beads (ReCath, Allison Park, PA) were implanted into the right jugular vein of subjects while under isoflourane (2%) anesthesia. The rats had a jacket with a port (SAI Infusion Technologies, CA) where the catheter exited dorsally between the shoulder blades, allowing access to the vein for drug infusions. After catheter implantation, heparin, at a dose of 100 mg/mL, was administered to each subject through the port to maintain catheter patency. Likewise, Baytril, at a dose of 50 mg/mL, was administered through the port to prevent infection. Lastly, rats were given an additional subcutaneous injection of Rimadyl (2.5 mg/kg) to prevent inflammation. Each animal was given approximately three days for recovery and then returned to behavioral testing. Furthermore, a daily regimen of the same doses of Baytril and heparin, indicated above, were administered through the catheter port to prevent infection and maintain catheter patency, respectively.

Drugs

Cocaine hydrochloride (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in 0.9% pharmaceutical-grade saline. A concentration of 250 μg per infusion of cocaine was used for response acquisition, maintenance, and the progressive ratio SA sessions. The SA testing examining the dose-effect relationship used concentrations of cocaine that were 31.25 μg, 62.5 μg, 125 μg, 250 μg, 375 μg, and a 500 μg. Each infusion delivered 50 μl of solution over a 2.5 sec duration and was followed by a 17.5 sec time-out period.

Procedure

An experimental timeline is presented in Fig. 1. When the rats reached 90 days old, they were single housed and placed on an IACUC-approved food restriction schedule at 85–90% of their free-feeding weight. The food restriction was used to ensure the motivation to work for a food reinforcer. This food restriction also helped maintain a relatively consistent body weight of each animal and ensured a comfortable fit of the rat SA jacket throughout the duration of the study. All offspring were weighed and fed at approximately the same time each day, during the lights-on phase of the cycle. At around 100 days old, the rats began testing in the operant chambers. Operant testing occurred seven days a week, one session per day in the order described below.

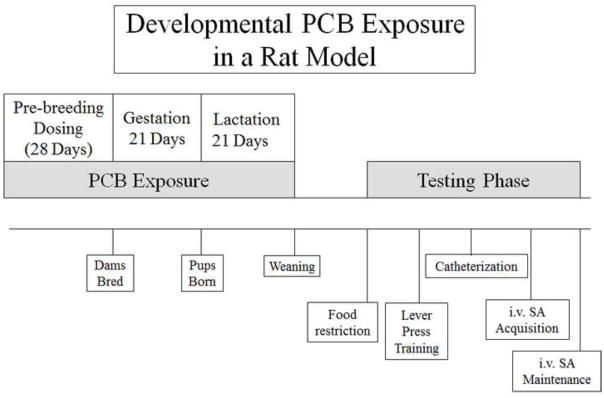

Figure 1.

The stock solution of the Fox River PCB mix was dissolved in corn oil to yield 0, 7.5, and 15.0 mg/ml concentrations. Based on the body weight of the dam, one concentration was pipetted onto half a vanilla wafer to yield a daily PCB dose of either 0 (corn oil only; n = 11 litters), 3 (n=13 litters), or 6 mg/kg body weight (n=14 litters). Each dosed cookie was orally consumed by the dam. At weaning, one male and female from each litter were retained and at approximately 75 days of age, these offspring were food restricted (85% of free-feeding weight) and trained to lever press for a food reinforcer using an autoshaping program and fixed ratio schedule beginning around PND 90. At approximately 120 days of age, jugular catheterization surgery occurred and around PND 180, i.v. self-administration sessions began during at which point the food reinforcer was replaced with an intravenous infusion of 250 μg of cocaine. GD = gestational day, PND = postnatal day, i.v. SA = intravenous self-administration

Autoshaping and Fixed-ratio training

To train the rats to press the lever, autoshaping was followed immediately by fixed ratio training procedures that have been described in detail elsewhere (Sable et al. 2006; 2009; 2011; Meyer et al., 2005). Rats remained on autoshaping until 100 lever presses occurred within the 60 min session and no free 45 mg reward pellets (Bio-Serve; Frenchtown, New Jersey) were dispensed. Daily fixed-ratio (FR) sessions included FR1 (~3 sessions), FR3 (~5 sessions), and FR5 (~x sessions until surgery). Each FR session ended after the rat had earned 100 food reinforcers.

Intravenous Self-Administration Response Acquisition

After three days of recovery from surgery, the animal resumed the previously described FR5 schedule for 3–4 days to ensure full recuperation had taken place and that the animal was adequately lever pressing. Once responding on FR5 had been re-established, the food reinforcer was removed and the rat began i.v. SA response acquisition for an infusion of cocaine as the reinforcer. Only the right lever was considered the “active lever” for cocaine SA, but both levers were presented and responses on both levers were recorded. Any “inactive lever” pressing had no consequence. The response requirement to earn a cocaine infusion was on the FR5 schedule on the active lever. Thus, rats that pressed the right active lever five times received a 50 μl infusion containing 250 μg of cocaine in a 2.5 s time interval. Previous research has demonstrated that other rat strains acquire and maintain cocaine i.v. SA at this dose (Kosten et al., 1997; Nation et. al., 2003; Nation et al., 2004). A 17.5 s timeout occurred after each infusion during which the levers were retracted and the house lights were extinguished. Sessions lasted two hr or until a maximum of 100 infusions were delivered. Rats met the criterion for acquisition when their SA behavior stabilized to reflect less than 25% variability in the number of infusions delivered across three consecutive days of testing.

Intravenous Self-Administration Maintenance Responding

When the criterion for acquisition was met, each rodent then moved to maintenance responding which was evaluated over another two weeks of testing. The parameters for maintenance were exactly the same as those used in response acquisition discussed above.

Intravenous Self-Administration Dose-Effect Relationship

Following maintenance, a different dose of cocaine (31.25 μg, 62.5 μg, 125 μg, 250 μg, 375 μg, or 500 μg of cocaine) was randomly assigned across the next six-days. Regardless of the concentration, each infusion delivered 50 μl of cocaine for 2.5 s. Other than the changes in cocaine dose, the SA testing parameters examining the dose-effect relationship were identical to those used during acquisition and maintenance.

Intravenous Self-Administration Progressive Ratio (PR)

After the dose-response paradigm, progressive ratio testing began and lasted for 4 sessions (one session per day). During each PR session, deliver of the cocaine reinforcer was the same as during acquisition and maintenance. During each PR session, an increasing number of lever presses were required for each successive drug infusion. Specifically, the number of responses needed to earn a drug infusion was: 1, 2, 4, 9, 12, 15, 20, 25, 32, 40, 50, 62, 77, 95, 118, 145, 178, 219, 268, 328, 402, 492, 603, 737, 901, 1102, 1347, 1647, and 2012 for each successive drug infusion such that the response requirement to earn an infusion increased at an exponential rate minus five. This schedule has been reported to be appropriate for studies examining cocaine i.v. SA in rats (Richardson & Roberts, 1996). Each PR session ended after 20 min elapsed between active lever presses.

Verification of catheter patency

All catheterized rats were checked for patency daily and again at necropsy. After euthanasia an immediate incision was made to expose the catheter implantation site and methylene blue dye was pushed through the port into the catheter line to visually confirm vascular patency.

Design

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS for MS Windows (version 22.0, SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL) with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. For acquisition, sessions to criterion was the total number of sessions conducted until the criterion for acquisition was met. On the other hand, active and inactive lever presses and the number of infusions for acquisition were averaged only across the three consecutive sessions that demonstrated the acquisition criterion had been met. This set of dependent variables was analyzed using a 3 (exposure group) × 2 (sex) × session mixed MANOVA with PCB exposure group as the between-subjects factor, and sex (nested within litter) as a repeated measures factor. Similar analyses with the additional independent variable session (for maintenance and progressive ratio) or dose (for dose-response) was also included as a repeated-measures factor where appropriate. If significant PCB exposure-related effects were observed in the overall MANOVA for each SA phase, additional ANOVAs for each dependent variable were obtained with corresponding Dunnett post hoc t-tests to determine the nature of the significance of these effects. To reveal the true nature of potential sex differences, if the main effect of sex and/or the PCB exposure × sex interaction was significant in the omnibus MANOVA, follow-up analyses were conducted separately for each sex.

Results

In the case of any missing data, mean substitution was employed. To ensure that this did not dramatically alter the experimental results, any dependent variable that required mean substitution was analyzed both with the substituted mean and also by dropping the entire litter (both male and female) from the analysis. No changes in the pattern of results were observed, so instances of mean substitution were retained for the analyses reported below.

Acquisition

A MANOVA was run on the dependent variables (sessions to criterion, active lever presses, inactive lever presses, and infusions) measured during acquisition. The main effect of PCB dose [F(8,66) = 3.209, p = .004] and the main effect of sex [F(4,32) = 13.526, p < .001] were significant by Pillai’s criterion, but the PCB dose × sex interaction was not significant. Given the observed sex difference, additional one-way ANOVAs for each dependent variable were done to determine if the significant effect of PCB dose was present when separated by sex. These results are presented below.

Sessions to criterion

There was not a significant difference among the PCB exposure groups in the number of sessions required to reach the criterion for completion of acquisition for either the males [F(2,35) = .340, p = .714] or for the females [F(2,35) = .087, p = .917].

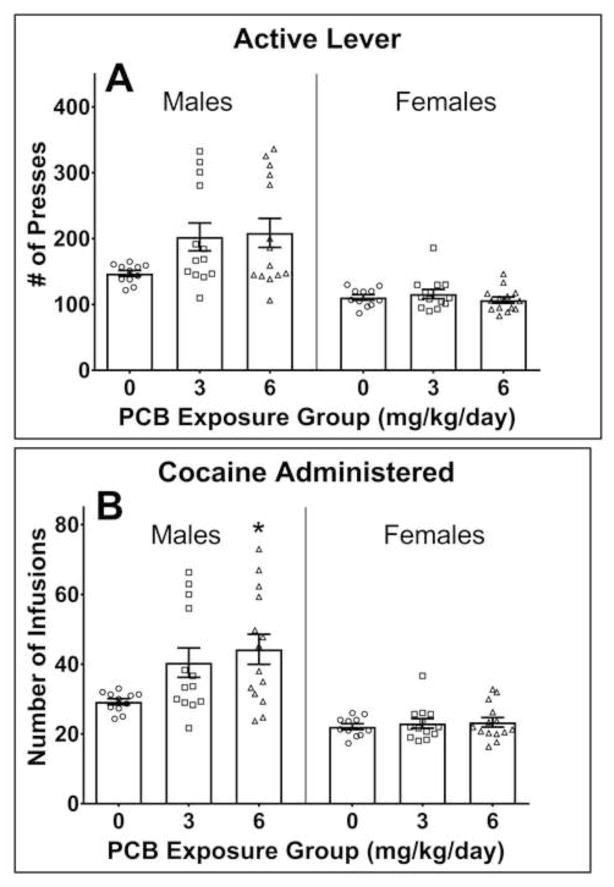

Number of active lever presses

As can be seen in Figure 2A, the number of active lever presses was higher in males (but not females) that were exposed to PCBs. However, the main effect of PCB exposure on the number of active lever presses in the males only approached significance [F(2,35) = 2.969, p = .064]. For both of these measures, there appeared to be more variability in the PCB-exposed males, with a distinct increase in the upper end of the distribution. There was no effect of PCB dose on the number of active lever presses in the females [F(2,35) = .748, p = .481]. The males in the 3 mg/kg and 6 mg/kg PCB groups pressed the active lever more than the non-exposed control males. However, Dunnett t-tests revealed that the differences between the 0 mg/kg PCB control group and the 3 mg/kg PCB group and 6 mg/kg PCB group were approaching statistical significance (p = .093 and p = .054, respectively).

Figure 2.

The number of active lever presses (top panel) and infusions of 250 μg of cocaine (bottom panel) during the acquisition phase in male and female rats perinatally exposed to either 0 (corn oil only; n = 11 litters), 3 (n=13 litters), or 6 mg/kg body weight (n=14 litters). One male and one female offspring from each litter were tested during adulthood. (A) Although males exposed to PCBs appeared to exhibit an increase in the number of active lever presses during acquisition compared to males in the 0 mg/kg/day PCB group, the effect of PCB exposure in the males was not statistically significant (p=.064). No difference was found on the number of active lever presses that occurred during acquisition in the female offspring. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. (B) A significant effect of PCB dose on the number of cocaine infusions earned occurred in the males but not in the females. PCB exposure appeared to increase variation in the males, be extending the upper end of the distribution. Statistical analysis revealed that only the males perinatally exposed to 6 mg/kg/day PCBs received a greater number of infusions than non-exposed (i.e., 0 mg/kg/day PCBs) males. *p=.015; Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Number of inactive lever presses

There was not a significant difference observed on the number of inactive lever presses among PCB exposure groups in the males [F(2,35) = 2.246, p = .121] or females [F(2,35) = .709, p = .499].

Number of infusions

There was a main effect of PCB exposure on the number of infusions delivered during acquisition in the males [F(2,35) = 4.095, p = .025] but not the females [F(2,35) = .251, p = .799]. Post hoc Dunnett t-tests revealed that the 3 mg/kg PCB males did not differ from the 0 mg/kg PCB group (p = .085). However, males in the 6 mg/kg PCB group had a significantly higher number of infusions than males in the 0 mg/kg PCB group (p = .015). See Figure 2B.

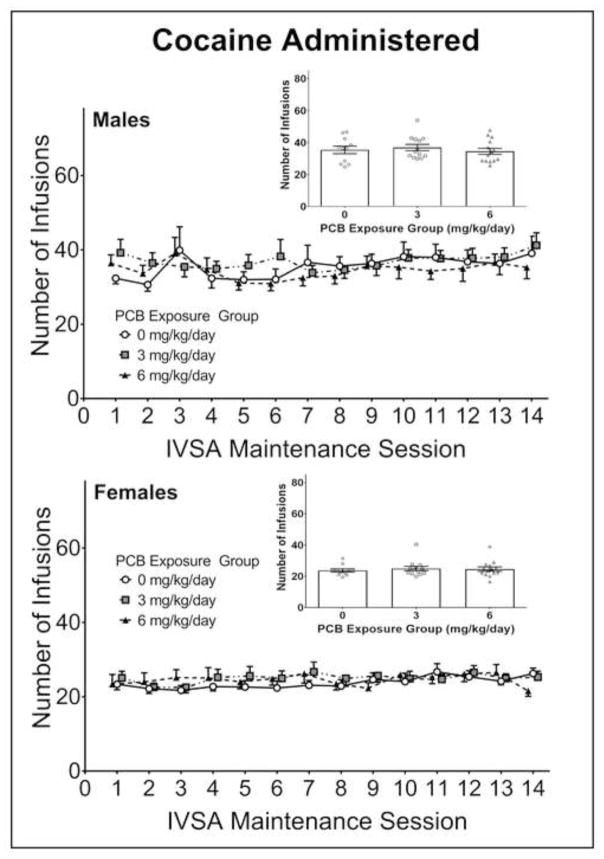

Maintenance

A MANOVA was run on the dependent variables (active lever presses, inactive lever presses, infusions, active lever response duration, inactive lever response duration, and overall response rate) measured during the 14 days of maintenance responding. While there was a main effect of sex [F(5,31) = 16.011, p < .001], the main effect of PCB dose [F(10,64) = .612, p = .798] and the PCB dose × sex interaction [F(10,64) = .444, p = .919] were not significant by Pillai’s criterion. As such, no obvious PCB-related differences were observed across the maintenance sessions in the males or females. The number of active lever presses and infusions (see Figure 3) were higher in males than in females. However, within each sex, these measures were similar among the three PCB exposure groups across all days of testing. Given the lack of significant PCB effects in the omnibus MANOVA, no additional follow-up analyses were conducted.

Figure 3.

The number of infusions received across the 14 days of maintenance responding in male (top panel) and female (bottom panel) rats perinatally exposed to either 0 (corn oil only; n = 11 litters), 3 (n=13 litters), or 6 mg/kg body weight (n=14 litters). One male and one female offspring from each litter were tested during adulthood. Males received more cocaine infusions (i.e., reinforcers) than females across all 14 maintenance sessions. However, there were no obvious PCB-related differences in either the males or females (see insets). Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

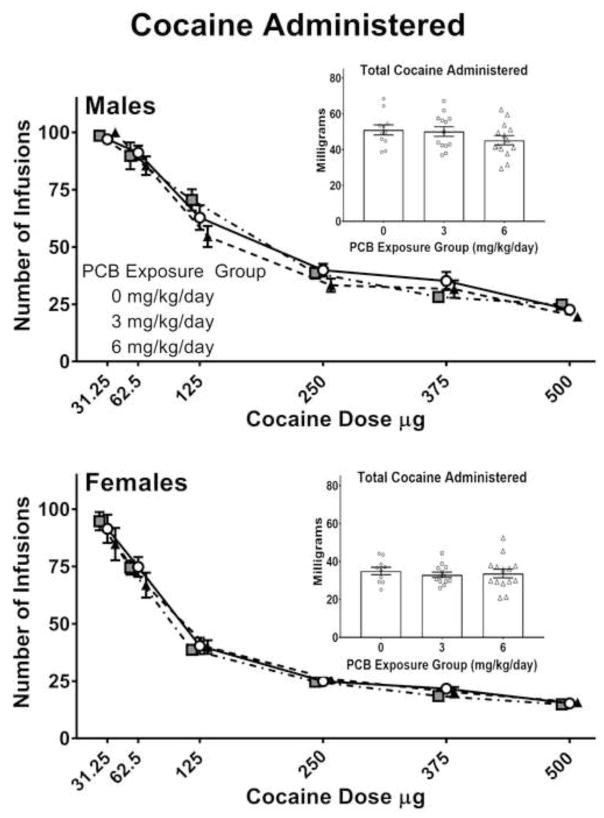

Dose-Effect Relationship

A MANOVA was run on the dependent variables (active lever presses, inactive lever presses, infusions, active lever response duration, inactive lever response duration, and session duration) measured across the six different cocaine doses examined. While there was a main effect of sex [F(6,30) = 15.115, p < .001] and cocaine dose [F(28,8) = 692.074, p < .001], the main effect of PCB dose [F(12,62) = .812, p = .637] as well as the PCB dose × sex [F(12,62) = 1.420, p = .216], PCB dose × cocaine [F(56,18) = 1.162, p = .375], and PCB dose × sex × cocaine [F(56,18) = .716, p = .830] interactions were all not significant by Pillai’s criterion. As such, no obvious PCB-related differences in the males or females were observed among the dependent variables analyzed across the sessions evaluating the dose-effect relationship. The number of infusions (including the total amount of cocaine administered) are presented in Figure 4. Active lever presses and infusions were higher in males than in females. These measures decreased in both sexes with increasing cocaine dose. Within each sex, these measures were similar among the three PCB exposure groups across all cocaine doses. Analysis of the total amount of cocaine self-administered across all cocaine doses also revealed a main effect of sex [F(1,35) = 90.055, p < .001], but not PCB-related differences (see Figure 4 insets).

Figure 4.

Male (top panel) and female (bottom panel) rats perinatally exposed to either 0 (corn oil only; n = 11 litters), 3 (n=13 litters), or 6 mg/kg body weight (n=14 litters) were tested across a range of cocaine doses. One male and one female offspring from each litter were tested during adulthood. Males had a higher number of infusions (i.e., reinforcers) than females and the overall number of infusions decreased with increasing cocaine dose. However, there were no PCB-related differences in either the males or females across any of the cocaine doses examined or on the total amount of cocaine self-administered during the dose-effect phase (see insets). Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Progressive ratio

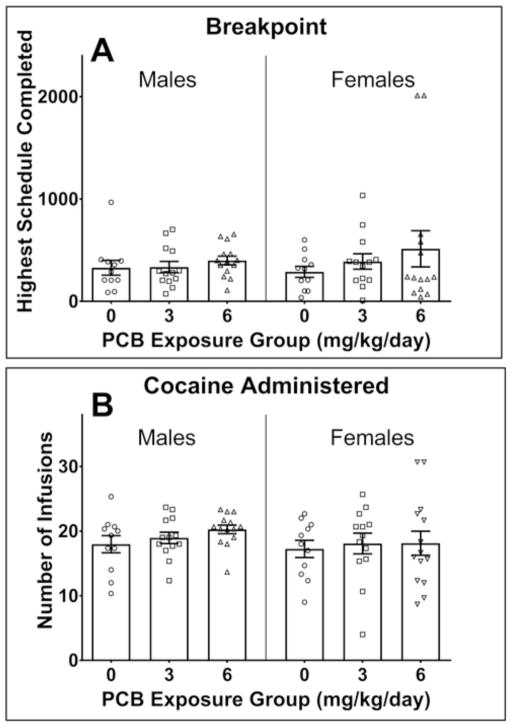

A MANOVA was run on the dependent variables (breakpoint, active lever presses, inactive lever presses, infusions, active lever response duration, inactive lever response duration, and session duration) measured across the three days of progressive ratio testing. While there was a main effect of sex [F(7,29) = 2.965, p = .018] and day of testing [F(14,22) = 3.783, p = .003], the main effect of PCB dose [F(14,60) = .645, p = .816] as well as the PCB dose × sex [F(14,60) = 1.058, p = .198], PCB dose × day [F(28,46) = 1.023, p = .463], and PCB dose × sex × day [F(28,46) = .667, p = .872] interactions were not significant by Pillai’s criterion. As such, no obvious PCB-related differences were observed across the three progressive ratio sessions in the males or females among the dependent variables analyzed. The breakpoint and infusions are presented in Figure 5A and 5B, respectively. The breakpoint and active lever presses were higher in females than in males, while the reverse was true for infusions. These measures changed across testing day with the three measures being slightly higher on day 2 compared to the other two days. Within each sex, the breakpoint and number of infusions delivered were similar among the three PCB exposure groups across all three sessions. The number of active lever presses appears to be slightly higher in the 6 mg/kg/day PCB-exposed females, but the PCB dose × sex interaction from the omnibus MANOVA was not significant so this effect as well as the remaining PCB-related effects were not evaluated further.

Figure 5.

The breakpoint (top panel) and number of infusions (bottom panel) during the progressive ratio phase in male and female rats perinatally exposed to either 0 (corn oil only; n = 11 litters), 3 (n=13 litters), or 6 mg/kg body weight (n=14 litters). One male and one female offspring from each litter were tested during adulthood. (A) Females had a higher breakpoint than males, but there were no PCB-related differences in either the males or females. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. (B) Males earned a higher number of reinforcers than females, but there were no PCB-related differences in either the males or females. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Discussion

PCB-exposed male, but not female, offspring had a significantly higher number of cocaine infusions (with a similar trend on active lever presses) during the acquisition phase. This effect was driven primarily by an increase in variability in the PCB-exposed males, particularly at the upper end of the distribution. When looking at the active lever presses and infusions from individual animals in each of the exposure groups, perinatal PCB exposure appeared to generate a higher ratio of male “responders” to “non-responders” than what was observed in the rats that were not exposed to PCBs. There was no difference in the number of sessions required to meet the criterion for acquisition. Recall that sessions to criterion for acquisition was a measure of behavioral (in)stability across groups, while number of infusions was a measure of intake across groups. The PCB group differences seen in the males during acquisition did not carry over into the maintenance phase. Rather, with more chronic cocaine exposure, the PCB-exposed and non-exposed rats of both sexes demonstrated similar behaviors during the maintenance phase. Likewise, no PCB-related effects were observed during examination of the dose-effect relationship or during progressive ratio testing which occurred later. Taken together these results seem to suggest that developmental PCB exposure has relatively little effect on cocaine SA. However, we are cautious about making such an assertion as one possible explanation for the lack of effect during later i.v. SA testing phases (i.e., maintenance, dose-effect relationship, and progressive ratio) could be due to a “ceiling effect”. Chronic exposure to cocaine has been demonstrated to reduce dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens of rats with no history of PCB exposure (Weiss, Paulus, Lorang, & Koob, 1992). In addition, we have shown adult rats perinatally exposed to PCBs exhibit an attenuation in stimulated peak dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens core following repeated cocaine administration, an effect likely tied to the depletion of presynaptic dopamine stores (Fielding et al., 2013). Therefore, the impact of PCB exposure could be difficult to evaluate with prolonged cocaine exposure since a reduction in dopamine neurotransmission might be exhibited after many cocaine SA sessions, making it difficult to tease out PCB-associated effects. In this study, rats were continuously tested for cocaine SA seven days per week from the beginning of acquisition throughout maintenance and examination of the dose-effect relationship, and concluding only after three days of progressive ratio testing.

Going forward, one approach that might be more effective would be to include periods of forced abstinence within the testing paradigm. Notably, this study did not evaluate the impact of PCB exposure on relapse responding. Evaluating the impact of PCB exposure on i.v. SA after several periods of forced deprivation (i.e., cocaine deprivation effect), on resistance to extinction, on Pavlovian spontaneous recovery, and on cue-induced responding will provide important additional information about the propensity for drug-seeking associated with developmental PCB exposure. It is interesting to note that we have previously demonstrated rats perinatally exposed to PCBs were more resistant to extinction on an inhibitory control task for a food reinforcer (Sable et al., 2006).

A second approach would be to evaluate cocaine i.v. SA starting at adolescence (not during adulthood as was done in this study) in animals that have undergone the same environmental contaminant exposure model. It has been well established that drug use is frequently initiated during adolescence (Johnston et al., 2016) and that maturational changes (including to the mesolimbic and mesocortical dopaminergic pathways) occurring during the adolescent window may contribute to the initiation of use (Doremus-Fitzwater and Spear, 2016; Spear, 2016). Furthermore, adolescent male rats have been shown to more readily self-administer cocaine (even at lower doses) and escalate their cocaine intake compared to adults (Wong et al., 2013). Thus, it would be interesting to evaluate whether the dopamine dysfunction associated with environmental contaminant exposure would have a more profound impact on cocaine SA during this more sensitive developmental window.

Of course it is also entirely possible that the detrimental effects of perinatal PCB exposure are limited to only i.v. SA cocaine response acquisition (and not SA sessions that occur later) and are sex-specific. There is a number of papers that propose that the frontal cortex is involved in initial learning or response acquisition while the striatum has been argued to be involved in maintaining well-established (i.e., habitual) behavior (Ashby et al. 2010; Hollerman et al., 2000; Schultz et al., 1998). As such, the result of this study could be speaking to regional specificity regarding the effects of developmental PCB exposure in the brain, with the frontal cortex (but not the striatum) being affected. Indeed, we have demonstrated that the same PCB exposure paradigm as the one used in this study impaired performance on executive function tasks requiring frontal cortex modulation for their successful execution (Sable et al., 2006; Sable et al., 2009).

The effects of ortho-substituted PCBs on the dopaminergic system (Faroon, Jones, & de Rosa, 2000) have been reported to be sex-specific (Lilienthal, Heikkinen, Andersson, van der Ven, & Viluksela, 2013). Recall that there was a significant effect of PCB exposure on the number of cocaine infusions during the acquisition phase only in the males, suggesting dopamine dysfunction is more profound in the PCB-exposed males. This sex effect was also observed by Poon et al. (2013) who observed a difference in amphetamine behavioral sensitization only in PCB-exposed males and by Sable et al. (2009) who observed inhibitory control deficits only in the males developmentally exposed to PCBs. Interestingly, cocaine behavioral sensitization (unpublished results) and stimulated dopamine release (Fielding et al., 2013) following acute and repeated cocaine administration were affected in both PCB-exposed males and females. PCBs are an endocrine-disrupting compound, which means they can alter normal endocrine functions including the normal function of thyroid and steroid hormones. Thyroid and steroid hormones are involved in the developmental organization of the nervous system and sexual differentiation in mammals (McCarthy, Wright, & Schwarz, 2009); therefore, endocrine disruption can have long-term consequences for the developing nervous system, especially during critical windows of development. Male offspring seem to be particularly sensitive to perinatal ortho-substituted PCB exposure (Cocchi et al., 2009; Kostyniak et al., 2005). The exact mechanism is not clear, but PCBs have been shown to lower aromatase activity (Hany et al., 1999; Kaya et al., 2002). Aromatase is the estrogen-synthesizing hormone that is more prevalent in the male brain where it converts testosterone to estradiol and plays a very important role in sexual differentiation of the male brain (Dickerson & Gore, 2007; Lauber, Sarasin, & Lichtensteiger, 1997a, 1997b; Roselli, 2007). Thus, aromatase/testosterone may provide a mechanism for the induction of the PCB-exposed sex differences that were observed in the current study. This theory is intriguing because an alteration in aromatase activity during early development has been shown to affect dopamine concentrations in the prefrontal cortex (Lauber et al., 1997a, 1997b; Stewart & Rajabi, 1994), an area of the brain critically involved in inhibitory control (Belin, Mar, Dalley, Robbins, & Everitt, 2008; Dalley, Mar, Economidou, & Robbins, 2008), psychostimulant behavioral sensitization (Steketee, 2005), and drug self-administration (Belin et al., 2008; de Wit, 2009).

As previously mentioned, differences in cocaine (unpublished results) and amphetamine (Poon et al., 2013) behavioral sensitization and drug discrimination (Sable et al., 2011) have been found in adult rats perinatally exposed to PCBs in comparison to controls. Likewise, other studies using animal models have reported that developmental exposure to lead (Clifford et al., 2011; D. K. Miller, Nation, & Bratton, 2000, 2001; Nation, Miller, & Bratton, 2000), cadmium (Nation & Miller, 1999), manganese (Guilarte et al., 2008; McDougall et al., 2008; Reichel et al., 2006), and methylmercury (Eccles & Annau, 1982; Newland, Reed, & Rasmussen, 2015; Rasmussen & Newland, 2001; Reed et al., 2008; Wagner, Reuhl, Ming, & Halladay, 2007) alter dopamine neurotransmission and alter the response to experimenter-administered psychostimulants during adulthood, often in a sex-specific manner. This is the first study to demonstrate that rats perinatally exposed to PCBs exhibit differences in the propensity to acquire self-administration of cocaine and is one of a handful of other studies demonstrating monoamine-disrupting environmental contaminants such as lead (Nation, Cardon, Heard, Valles, & Bratton, 2003; Nation, Smith, & Bratton, 2004; Rocha, Valles, Bratton, & Nation, 2008; Rocha, Valles, Cardon, Bratton, & Nation, 2005; Rocha, Valles, Hart, Bratton, & Nation, 2008; Valles, Rocha, Cardon, Bratton, & Nation, 2005) and cadmium (Cardon, Rocha, Valles, Bratton, & Nation, 2004) can also alter psychostimulant self-administration in adulthood after perinatal exposure. Thus, there is converging research to demonstrate that exposure to monoamine-disrupting chemicals during early development can promote drug-seeking later in life.

Evaluation of the impact of perinatal environmental contaminant exposure on substance use and abuse later in life is extremely difficult to examine in prospective longitudinal birth cohorts due to challenges associated with the cost of such studies, participant retention, interpretation of results (because participants have often been exposed to multiple contaminants), and the validity of self-reported or historical drug use data. As such, preclinical models like the one used here are needed to accurately evaluate the impact of early developmental contaminant exposure on drug-seeking (as well as any other negative behavioral consequences). Unfortunately, because contaminant exposures are often discovered “after-the-fact” when prevention is not possible, preclinical models of environmental contaminant exposure are also needed to evaluate the potential of therapeutic interventions (e.g., dietary supplementation and/or pharmacotherapies) to correct or reverse both the neurotoxicological effects (e.g., dopaminergic dysfunction) and any associated behavioral dysfunction that has occurred due to contaminant exposure.

In summary, the results of this project using an animal model supported a link between developmental contaminant exposure in PCB-exposed males and enhanced acquisition of cocaine i.v. SA. Such results suggest that individuals perinatally exposed to PCBs may exhibit a greater propensity for drug abuse than individuals without a history of contaminant exposure. Future research using this preclinical environmental exposure model while looking at different SA parameters and in different age groups will be necessary to explore this issue further. Likewise, it will be important to consider this issue and attempt to accurately assess similar outcomes in ongoing and future epidemiological studies of individuals developmentally exposed to monoamine-disrupting environmental contaminants.

Public Significance.

Data collected in this study using a preclinical model of developmental contaminant exposure indicated that perinatal exposure to the legacy contaminant polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) increased the acquisition of cocaine intravenous self-administration in male (but not female) offspring. These results suggest that developmental exposure to environmental contaminants may sex-specifically increase the propensity for drug-seeking.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Karyl Buddington for her outstanding veterinary support.

Footnotes

Disclosure

This work was financially supported (with no other role) by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences at the National Institutes of Health [grant number R00ES015428] and by a grant from The University of Memphis Faculty Research Grant Fund. The latter does not necessarily imply endorsement by the University of the research conclusions.

All authors contributed in a significant way to the manuscript and all authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

All authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Ashby FG, Turner BO, Horvitz JC. Cortical and basal ganglia contributions to habit learning and automaticity. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2010;14:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belin D, Mar AC, Dalley JW, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. High impulsivity predicts the switch to compulsive cocaine-taking. Science. 2008;320:1352–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1158136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobzean SA, DeNobrega AK, Perrotti LI. Sex differences in the neurobiology of drug addiction. Experimental Neurology. 2014;259:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher O, Muckle G, Jacobson JL, Carter RC, Kaplan-Estrin M, Ayotte P, … Jacobson SW. Domain-specific effects of prenatal exposure to PCBs, mercury, and lead on infant cognition: results from the Environmental Contaminants and Child Development Study in Nunavik. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2014;122:310–316. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1206323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardon AL, Rocha A, Valles R, Bratton GR, Nation JR. Exposure to cadmium during gestation and lactation decreases cocaine self-administration in rats. Neurotoxicology. 2004;25:869–875. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Third national report on human exposure to environmental chemicals. 2005 (Pub. No 05-0570 ). Retrieved from < https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/21809>.

- Clifford PS, Hart N, Rothman RB, Blough BE, Bratton GR, Wellman PJ. Perinatal lead exposure alters locomotion induced by amphetamine analogs in rats. Life Sciences. 2011;88:586–589. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocchi D, Tulipano G, Colciago A, Sibilia V, Pagani F, Vigano D, … Celotti F. Chronic treatment with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) during pregnancy and lactation in the rat: Part 1: Effects on somatic growth, growth hormone-axis activity and bone mass in the offspring. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2009;237:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Mar AC, Economidou D, Robbins TW. Neurobehavioral mechanisms of impulsivity: fronto-striatal systems and functional neurochemistry. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2008;90:250–260. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H. Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: a review of underlying processes. Addiction Biology. 2009;14:22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SM, Gore AC. Estrogenic environmental endocrine-disrupting chemical effects on reproductive neuroendocrine function and dysfunction across the life cycle. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 2007;8:143–159. doi: 10.1007/s11154-007-9048-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doremus-Fitzwater TL, Spear LP. Reward-centricity and attenuated aversions: an adolescent phenotype emerging from studies in laboratory animals. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2016;70:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles CU, Annau Z. Prenatal methyl mercury exposure: II. Alterations in learning and psychotropic drug sensitivity in adult offspring. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 1982;4:377–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eubig PA, Aguiar A, Schantz SL. Lead and PCBs as risk factors for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2010;118:1654–1667. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faroon O, Jones D, de Rosa C. Effects of polychlorinated biphenyls on the nervous system. Toxicology and Industrial Health. 2000;16:305–333. doi: 10.1177/074823370001600708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein GG, Jacobson JL, Jacobson SW, Schwartz PM, Dowler JK. Prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls: effects on birth size and gestational age. Journal of Pediatrics. 1984;105:315–320. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielding JR, Rogers TD, Meyer AE, Miller MM, Nelms JL, Mittleman G, … Sable HJ. Stimulation-evoked dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens following cocaine administration in rats perinatally exposed to polychlorinated biphenyls. Toxicological Sciences. 2013;136:144–153. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govarts E, Nieuwenhuijsen M, Schoeters G, Ballester F, Bloemen K, de Boer M, … Bonde JP. Birth weight and prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE): a meta-analysis within 12 European Birth Cohorts. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2012;120:162–170. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P, Landrigan PJ. Developmental neurotoxicity of industrial chemicals. Lancet. 2006;368:2167–2178. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(06)69665-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilarte TR, Burton NC, McGlothan JL, Verina T, Zhou Y, Alexander M, … Schneider JS. Impairment of nigrostriatal dopamine neurotransmission by manganese is mediated by pre-synaptic mechanism(s): implications to manganese-induced parkinsonism. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2008;107:1236–1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05695.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hany J, Lilienthal H, Sarasin A, Roth-Harer A, Fastabend A, Dunemann L, … Winneke G. Developmental exposure of rats to a reconstituted PCB mixture or aroclor 1254: effects on organ weights, aromatase activity, sex hormone levels, and sweet preference behavior. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1999;158:231–243. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollerman JR, Tremblay L, Schultz W. Involvement of basal ganglia and orbitofrontal cortex in goal-directed behavior. Progress in Brain Research. 2000;126:193–215. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)26015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inadera H. Neurological Effects of Bisphenol A and its Analogues. International Journal of Medical Sciences. 2015;12:926–936. doi: 10.7150/ijms.13267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson JL, Jacobson SW. Prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and attention at school age. Journal of Pediatrics. 2003;143:780–788. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00577-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson JL, Jacobson SW, Humphrey HE. Effects of in utero exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and related contaminants on cognitive functioning in young children. Journal of Pediatrics. 1990;116:38–45. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81642-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future: National Results on Adolescent Drug Use: Overview and Key Findings. 2016 Retrieved from < http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2015.pdf>.

- Kaya H, Hany J, Fastabend A, Roth-Harer A, Winneke G, Lilienthal H. Effects of maternal exposure to a reconstituted mixture of polychlorinated biphenyls on sex-dependent behaviors and steroid hormone concentrations in rats: dose-response relationship. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2002;178:71–81. doi: 10.1006/taap.2001.9318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Miserendino MJ, Haile CN, DeCaprio JL, Jatlow PI, Nestler EJ. Acquisition and maintenance of intravenous self-administration in Lewis and Fisher inbred rat strains. Brain Research. 1997;778:419–429. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01205-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostyniak PJ, Hansen LG, Widholm JJ, Fitzpatrick RD, Olson JR, Helferich JL, … Schantz SL. Formulation and characterization of an experimental PCB mixture designed to mimic human exposure from contaminated fish. Toxicological Sciences. 2005;88:400–411. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauber ME, Sarasin A, Lichtensteiger W. Sex differences and androgen-dependent regulation of aromatase (CYP19) mRNA expression in the developing and adult rat brain. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 1997a;61:359–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauber ME, Sarasin A, Lichtensteiger W. Transient sex differences of aromatase (CYP19) mRNA expression in the developing rat brain. Neuroendocrinology. 1997b;66:173–180. doi: 10.1159/000127235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienthal H, Heikkinen P, Andersson PL, van der Ven LT, Viluksela M. Dopamine-dependent Behavior in Adult Rats after Perinatal Exposure to Purity-controlled Polychlorinated Biphenyl Congeners (PCB52 and PCB180) Toxicology Letters. 2013;224:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London L, Flisher AJ, Wesseling C, Mergler D, Kromhout H. Suicide and exposure to organophosphate insecticides: cause or effect? American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2005;47:308–321. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM, Wright CL, Schwarz JM. New tricks by an old dogma: mechanisms of the Organizational/Activational Hypothesis of steroid-mediated sexual differentiation of brain and behavior. Hormones and Behavior. 2009;55:655–665. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall SA, Reichel CM, Farley CM, Flesher MM, Der-Ghazarian T, Cortez AM, … Crawford CA. Postnatal manganese exposure alters dopamine transporter function in adult rats: Potential impact on nonassociative and associative processes. Neuroscience. 2008;154:848–860. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DK, Nation JR, Bratton GR. Perinatal exposure to lead attenuates the conditioned reinforcing properties of cocaine in male rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2000;67:111–119. doi: 10.1016/S0091-3057(00)00303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DK, Nation JR, Bratton GR. The effects of perinatal exposure to lead on the discriminative stimulus properties of cocaine and related drugs in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2001;158:165–174. doi: 10.1007/s002130100877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nation JR, Cardon AL, Heard HM, Valles R, Bratton GR. Perinatal lead exposure and relapse to drug-seeking behavior in the rat: a cocaine reinstatement study. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:236–243. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nation JR, Miller DK. The effects of cadmium contamination on the discriminative stimulus properties of cocaine and related drugs. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1999;7:90–102. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.2.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nation JR, Miller DK, Bratton GR. Developmental lead exposure alters the stimulatory properties of cocaine at PND 30 and PND 90 in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:444–454. doi: 10.1016/s0893-133x(00)00118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nation JR, Smith KR, Bratton GR. Early developmental lead exposure increases sensitivity to cocaine in a self-administration paradigm. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2004;77:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Reseach Council, Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Newland MC, Hoffman DJ, Heath JC, Donlin WD. Response inhibition is impaired by developmental methylmercury exposure: acquisition of low-rate lever-pressing. Behavioural Brain Researchearch. 2013;253:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newland MC, Reed MN, Rasmussen E. A hypothesis about how early developmental methylmercury exposure disrupts behavior in adulthood. Behavioural Processes. 2015;114:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH. Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Rockville, MD: NIH/Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Poon E, Monaikul S, Kostyniak PJ, Chi LH, Schantz SL, Sable HJ. Developmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls reduces amphetamine behavioral sensitization in Long-Evans rats. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2013;38:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen EB, Newland MC. Developmental exposure to methylmercury alters behavioral sensitivity to D-amphetamine and pentobarbital in adult rats. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2001;23:45–55. doi: 10.1016/S0892-0362(00)00112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MN, Banna KM, Donlin WD, Newland MC. Effects of gestational exposure to methylmercury and dietary selenium on reinforcement efficacy in adulthood. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2008;30:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel CM, Wacan JJ, Farley CM, Stanley BJ, Crawford CA, McDougall SA. Postnatal manganese exposure attenuates cocaine-induced locomotor activity and reduces dopamine transporters in adult male rats. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2006;28:323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson NR, Roberts DC. Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1996;66:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha A, Valles R, Bratton GR, Nation JR. Developmental lead exposure alters methamphetamine self-administration in the male rat: acquisition and reinstatement. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;95:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha A, Valles R, Cardon AL, Bratton GR, Nation JR. Enhanced acquisition of cocaine self-administration in rats developmentally exposed to lead. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:2058–2064. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha A, Valles R, Hart N, Bratton GR, Nation JR. Developmental lead exposure attenuates methamphetamine dose-effect self-administration performance and progressive ratio responding in the male rat. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2008;89:508–514. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli CF. Brain aromatase: roles in reproduction and neuroprotection. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2007;106:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol DA, Genuis SJ, Frye RE. Environmental toxicants and autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Translational Psychiatry. 2014;4:e360. doi: 10.1038/tp.2014.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sable HJ, Eubig PA, Powers BE, Wang VC, Schantz SL. Developmental exposure to PCBs and/or MeHg: effects on a differential reinforcement of low rates (DRL) operant task before and after amphetamine drug challenge. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2009;31:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sable HJ, Monaikul S, Poon E, Eubig PA, Schantz SL. Discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine and amphetamine in rats following developmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2011;33:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sable HJ, Powers BE, Wang VC, Widholm JJ, Schantz SL. Alterations in DRH and DRL performance in rats developmentally exposed to an environmental PCB mixture. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2006;28:548–556. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sable HJK, Schantz SL. Frontiers in Neuroscience Executive Function following Developmental Exposure to Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs): What Animal Models Have Told Us. In: Levin ED, Buccafusco JJ, editors. Animal Models of Cognitive Impairment. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Taylor & Francis Group, LLC; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieve LA, Baio J, Rice CE, Durkin M, Kirby RS, Drews-Botsch C, … Cunniff CM. Risk for cognitive deficit in a population-based sample of U.S. children with autism spectrum disorders: variation by perinatal health factors. Disability and Health Journal. 2010;3:202–212. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W, Tremblay L, Hollerman JR. Reward prediction in primate basal ganglia and frontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;37:421–429. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. Consequences of adolescent use of alcohol and other drugs: studies using rodent models. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2016;70:228–243. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steketee JD. Cortical mechanisms of cocaine sensitization. Critical Reviews in Neurobiology. 2005;17:69–86. doi: 10.1615/CritRevNeurobiol.v17.i2.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J, Rajabi H. Estradiol derived from testosterone in prenatal life affects the development of catecholamine systems in the frontal cortex in the male rat. Brain Research. 1994;646:157–160. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart PW, Sargent DM, Reihman J, Gump BB, Lonky E, Darvill T, … Pagano J. Response inhibition during differential reinforcement of low rates (DRL) schedules may be sensitive to low-level polychlorinated biphenyl, methylmercury, and lead exposure in children. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2006;114:1923–1929. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valles R, Rocha A, Cardon A, Bratton GR, Nation JR. The effects of the GABAA antagonist bicuculline on cocaine self-administration in rats exposed to lead during gestation/lactation. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2005;80:611–619. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijheid M, Casas M, Gascon M, Valvi D, Nieuwenhuijsen M. Environmental pollutants and child health-A review of recent concerns. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 2016;219:331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GC, Reuhl KR, Ming X, Halladay AK. Behavioral and neurochemical sensitization to amphetamine following early postnatal administration of methylmercury (MeHg) Neurotoxicology. 2007;28:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F, Paulus MP, Lorang MT, Koob GF. Increases in extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens by cocaine are inversely related to basal levels: effects of acute and repeated administration. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:4372–4380. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04372.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winneke G. Developmental aspects of environmental neurotoxicology: lessons from lead and polychlorinated biphenyls. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2011;308:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong WC, Ford KA, Pagels NE, McCutcheon JE, Marinelli M. Adolescents are more vulnerable to cocaine addiction: behavioral and electrophysiological evidence. Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33:4913–4922. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1371-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]