Abstract

Background

This study examined the association of extent of lung resection, pathologic nodal evaluation, and survival for patients with clinical stage I (cT1-2N0M0) adenocarcinoma with lepidic histology in the National Cancer Database (NCDB).

Methods

The association between extent of surgical resection and long-term survival for patients in the NCDB with clinical stage I lepidic adenocarcinoma who underwent lobectomy or sublobar resection was evaluated using Kaplan-Meier and Cox proportional hazards regression analyses.

Results

Of the 1,991 patients with cT1-2N0M0 lepidic adenocarcinoma who met study criteria, 1,544 patients underwent lobectomy and 447 underwent sublobar resections. Patients treated with sublobar resection were older, more likely to be female, had higher Charlson/Deyo comorbidity scores, but had smaller tumors and lower T-status. Of patients treated with lobectomy, 6% (n=92) were upstaged due to positive nodal disease, with a median of 7 lymph nodes sampled (IQR: 4,10). In an analysis of the entire cohort, lobectomy was associated with a significant survival advantage over sublobar resection in univariate analysis (median survival 9.2 vs. 7.5 years, p=0.022; 5-year survival 70.5% vs. 67.8%) and following multivariable adjustment (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.81 [95% [CI]: 0.68–0.95], p=0.011), (Figure 1). However, lobectomy was no longer independently associated with improved survival when compared to sublobar resection (HR: 0.99 [95% CI: 0.77–1.27], p= 0.905) in a multivariable analysis of a subset of patients that compared only those patients who underwent sublobar resection that included lymph node sampling to patients treated with lobectomy.

Conclusions

Surgeons treating patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma with lepidic features should cautiously utilize sublobar resection rather than lobectomy and must always perform adequate pathologic lymph node evaluation.

INTRODUCTION

Classification of lung adenocarcinoma has been revised based on the increasingly recognized importance of the extent of pathologic tumor invasion on prognosis. Lepidic adenocarcinoma of the lung has well-differentiated histology with tumor growth defined as in-situ non-invasive growth along intact alveolar septa, and historically had previously been referred to as bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC).1–3 Adenocarcinoma with pure lepidic growth and predominant lepidic growth with less than 5mm invasion are now classified as adenocarcinoma in situ and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma.3 Rates of lepidic adenocarcinoma have been increasing over the past several decades but remains uncommon, with an estimated incidence of less than 4% of all non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) according to data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registry.4

Lung adenocarcinomas with lepidic histology typically have the appearance of ground glass opacity (GGO) on imaging, often occur in non-smokers, and are increasingly accepted as presenting at earlier stages and behaving less aggressively than other adenocarcinoma subtypes.5–13 Accordingly, the diagnosis of lepidic disease typically carries a more favorable prognosis than other adenocarcinoma subtypes, with disease-specific survival approaching almost 100% for patients with very small tumors and no evidence of invasion.4–17 Although margin-negative anatomic surgical resection with systematic lymph node evaluation is generally considered the standard of care for early-stage NSCLC in qualified patients, studies as to whether a sublobar resection is oncologically equivalent to a lobectomy for pure GGO lesions and minimally invasive adenocarcinomas are being conducted.18–21 However, most of the data related to outcomes and treatment for lepidic adenocarcinoma has come from either single-institution studies or studies with very homogenous patient populations. The purpose of this study was to examine outcomes after surgical treatment of lepidic adenocarcinoma across a wider spectrum of patients using a large, nationwide clinical cancer database. The specific goal was to test the primary hypothesis that a lobectomy is associated with better survival than sublobar resection clinical stage I (cT1-2N0M0) lepidic lung adenocarcinoma. A secondary goal was to examine the practice and impact on outcomes of surgical lymph node sampling when a sublobar resection is utilized.

METHODS

The Duke University Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective analysis of the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB). The NCDB is a jointly administered effort by the American Cancer Society and the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (CoC), collecting data from more than 1,500 cancer facilities around the United States. The database currently contains more than 30 million patient records and is estimated to capture approximately 70% of all new cancer diagnoses annually.

Patients who were treated with either lobectomy or sublobar resection for clinical stage I (cT1-2N0M0) lepidic disease from 2003–2006, earliest date for which all variables were present and latest survival data, were identified for inclusion based on International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd Edition (ICD-O-3) histology codes for bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (8250-4), as well as Facility Oncology Registry Data Standards (FORDS) procedure codes for lobectomy and sublobar resection. Clinical and pathological stage data were directly extracted based on American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 6th edition staging criteria. This older system was used rather than the more recent 7th edition because this was the staging system in place at the time of diagnosis and treatment for the patients in the study. Patients were excluded from analysis if they received induction chemotherapy or radiation therapy, as were patients treated with local excision or pneumonectomy.

Patients were stratified by surgical approach, and baseline comparisons of characteristics between the cohort of patients treated with lobectomy and those treated with sublobar resection were compared using Wilcoxon Rank Sum test for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables. Patients treated with sublobar resection were then further grouped according to whether or not they underwent lymph node sampling as part of their procedure, and similar univariate comparisons were conducted. The primary outcome of interest was long-term survival between groups, which was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. To estimate the independent effect of extent of resection on long-term survival, a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model was developed, which included patient age, sex, race, Charlson/Deyo comorbidity score, and tumor size. Similar survival analyses were then conducted to estimate the effect of lymph node sampling among patients treated with sublobar resection, and to compare survival between patients treated with lobectomy and those treated with sublobar resection that included lymph node sampling.

For all analyses a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We made an affirmative decision to control for type I error at the level of all comparisons. Missing data were handled with complete-case analysis in light of the substantial completeness of the NCDB data for the study population. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

A total of 1,991 patients with cT1-2N0M0 lepidic adenocarcinoma were identified in the database and met study criteria, of which 1,544 (77.5%) underwent lobectomy and 447 (22.5%) were treated with sublobar resection. Of those patients treated with sublobar resection, 374 (83.7%) were wedge resections and 73 (16.2%) were segmentectomies. The segmentectomy cohort was too small to undergo subgroup analysis. Patients treated with sublobar resection were slightly older (median 70 vs. 69 years), more likely to be female (68.9 vs. 63%), and more likely to have Charlson/Deyo comorbidity scores greater than 0 (47.4 vs. 36.4%), but had smaller tumors (median 1.6 vs. 2.4 cm) and higher proportions of T1 disease (80.5 vs 67.6%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with cT1-2N0M0 lepidic lung adenocarcinoma, stratified by extent of surgical resection

| Lobectomy (N=1544) |

Sublobar (N=447) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Age (year) | 0.006 | ||

| Median | 69 | 70 | |

| Q1, Q3 | 61.0, 75.0 | 62.0, 77.0 | |

| Sex | 0.021 | ||

| Male | 572 (37.0%) | 139 (31.1%) | |

| Female | 972 (63.0%) | 308 (68.9%) | |

| Race | 0.074 | ||

| White | 1391 (90.1%) | 412 (92.2%) | |

| Black | 81 (5.2%) | 25 (5.6%) | |

| Other | 72 (4.7%) | 10 (2.2%) | |

| Charlson/Deyo Score | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 982 (63.6%) | 235 (52.6%) | |

| 1 | 424 (27.5%) | 147 (32.9%) | |

| 2 | 138 (8.9%) | 65 (14.5%) | |

| Clinical T staging | <0.001 | ||

| T1 | 1043 (67.6%) | 360 (80.5%) | |

| T2 | 501 (32.4%) | 87 (19.5%) | |

| Size of Tumor (cm) | <0.001 | ||

| Median | 2.4 | 1.6 | |

| Q1, Q3 | 1.7, 3.4 | 1.1, 2.4 | |

| Pathological N staging | 0.002 | ||

| 0 | 1367 (88.5%) | 252 (56.4%) | |

| 1 | 55 (3.6%) | 6 (1.3%) | |

| 2 | 37 (2.4%) | 4 (0.9%) | |

| X | 85 (5.5%) | 185 (41.4%) | |

| Pathological T staging | <0.001 | ||

| 1 | 920 (59.6%) | 284 (63.5%) | |

| 2 | 526 (34.1%) | 79 (17.7%) | |

| 3 | 2 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 4 | 37 (2.4%) | 5 (1.1%) | |

| X | 59 (3.8%) | 79 (17.7%) |

Of the 1,544 patients treated with lobectomy, 1460 (94.6%) also had pathologic lymph node evaluation, and 92 (6%) were subsequently upstaged due to positive nodal disease with a median of 7 lymph nodes sampled (IQR: 4, 10; range 1–57). Of those upstaged, 55 (3.6%) patients were upstaged to N1 while 37 (2.4%) patients were upstaged to N2. In contrast, lymph node sampling was performed as part of the procedure in only 199 (45%) of patients treated with sublobar resection with a median of 4 lymph nodes sampled (IQR: 2, 7; range 1–40). In the sublobar cohort, nodal upstaging occured in 10 (2.2%) patients with 6 (1.3%) upstaged to N1 and 4 (0.9%) upstaged to N2 (Table 1). In the sublobar resection cohort, there were no statistically significant differences in patient or tumor characteristics between patients treated with versus without nodal sampling.

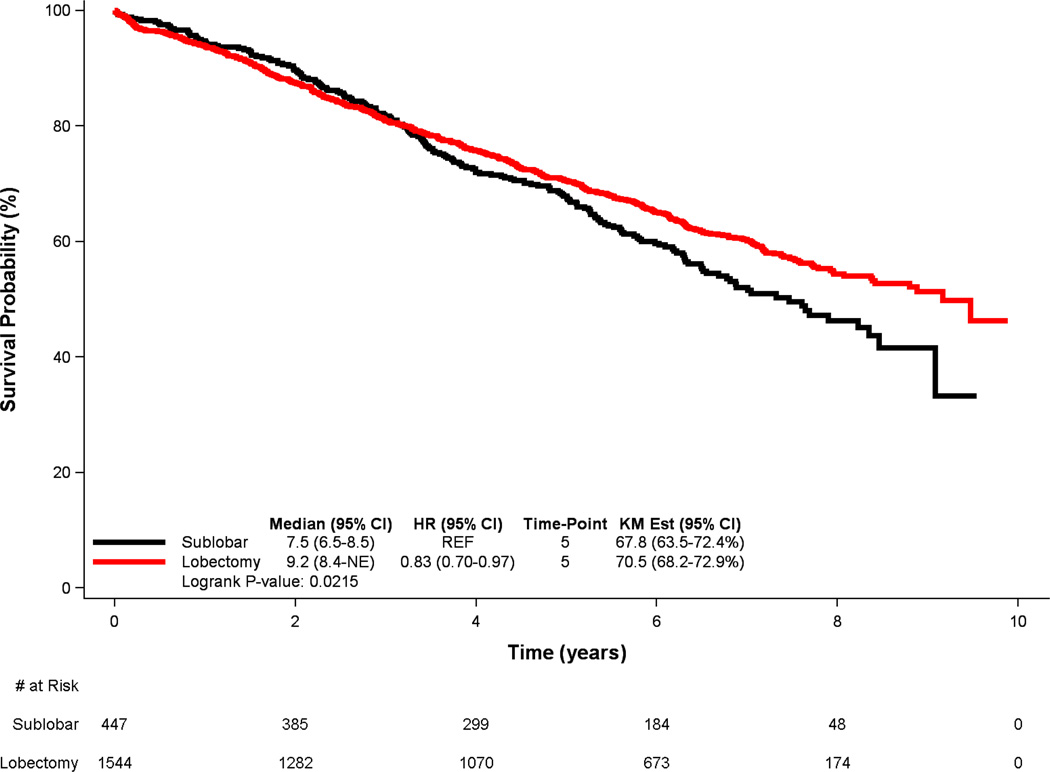

In unadjusted survival analysis of the entire study population (Figure 1), lobectomy was associated with a significant survival advantage over sublobar resection (median survival 9.2 vs. 7.5 years, p=0.022; 5-year survival 70.5% vs. 67.8%). Following multivariable adjustment, lobectomy maintained a significantly lower risk of long-term death (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.81 [95% CI: 0.68–0.95], p=0.011) (Table 2). Similarly, younger age, female sex, White race, lower Charlson/Deyo comorbidity scores, and smaller tumors were all also associated with superior long-term survival.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with early-stage lepidic lung adenocarcinoma, stratified by extent of resection

Table 2.

Adjusted risk of death among patients with cT1-2N0M0 lepidic lung adenocarcinoma

| Effect | HR | 95% Confidence Intervals |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lobectomy vs Sublobar | 0.81 | 0.68, 0.95 | 0.011 |

| Age (unit=10) | 1.46 | 1.35, 1.59 | <.0011 |

| Female vs male) | 0.78 | 0.67, 0.90 | 0.001 |

| Black vs White | 1.45 | 1.07, 1.96 | 0.016 |

| Others vs White | 0.90 | 0.60, 1.35 | 0.600 |

| Charlson Score 1 vs 0 | 1.31 | 1.12, 1.54 | 0.001 |

| Charlson Score 2 vs 0 | 1.87 | 1.52, 2.31 | <.0011 |

| Tumor size (unit=1cm) | 1.13 | 1.10, 1.16 | <.0011 |

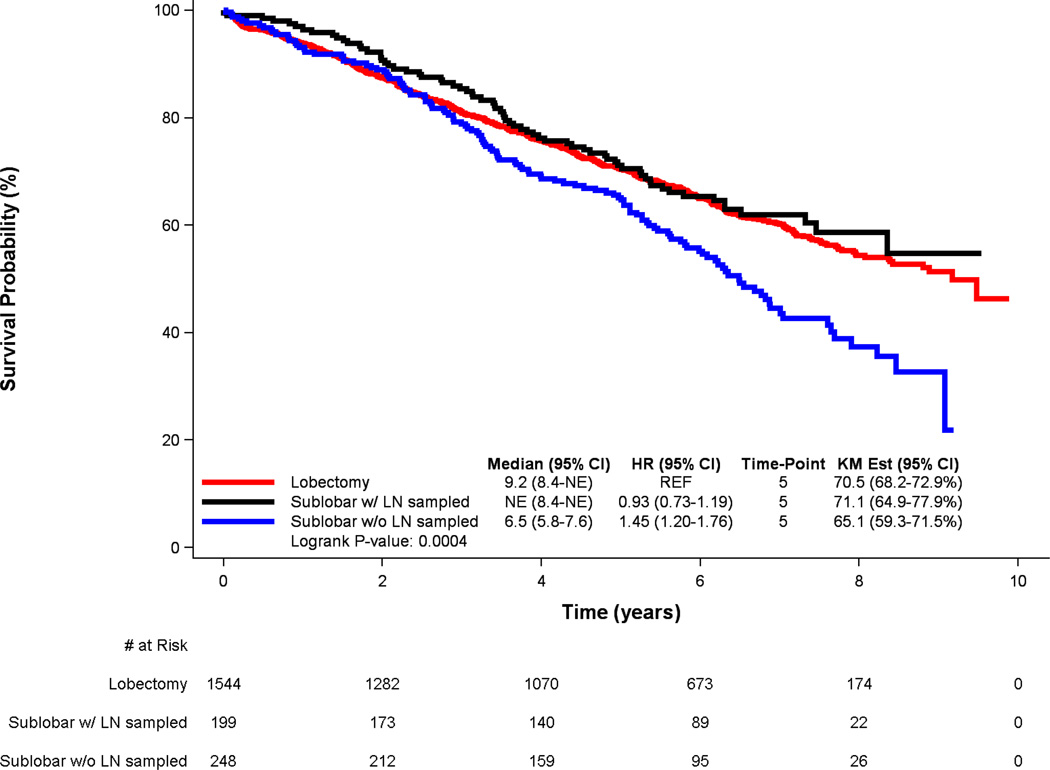

Among patients treated with sublobar resection, lymph node sampling was associated with substantially improved 5-year survival compared to lack of lymph node sampling (71.1% vs. 65.1%). For those patients in whom lymph nodes were not sampled, median survival was 6.5 years, compared to a median survival that was not reached during the study period for patient who underwent lymph node sampling (p=0.003). Following multivariable Cox proportional hazards adjustment, lymph node sampling was associated with a substantially lower hazard of long-term death (HR: 0.68 [95% CI: 0.51–0.92], p=0.013) in the cohort of patients who had a sublobar resection.

To examine how the addition of lymph node sampling to sublobar resection affected survival compared to lobectomy, survival among the three treatment groups was compared (Figure 2), revealing no statistically significant differences in survival between patients treated with sublobar resection that included nodal sampling and lobectomy (HR: 0.93 [95% CI: 0.73–1.19], p= 0.56), but markedly worse survival for patients treated with sublobar resection that did not include nodal sampling compared to patients treated with lobectomy (HR: 1.45 [95% CI: 1.20–1.76], p< 0.001). Furthermore, in a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model including only those patients treated with lobectomy or sublobar resection that included lymph node sampling, extent of resection (lobectomy versus sublobar resection) was no longer independently associated with survival (HR: 0.99 [95% CI: 0.77–1.27], p=0.905) (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with early-stage lepidic lung adenocarcinoma, stratified by extent of resection and presence of lymph node sampling

Table 3.

Adjusted risk of death among patients treated with lobectomy and sublobar resection that included lymph node sampling

| Effect | HR | 95% Confidence Limits |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sublobar vs lobectomy | 0.99 | 0.77, 1.27 | 0.905 |

| Age (unit=10) | 1.04 | 1.03, 1.05 | <.001 |

| Female vs male) | 0.76 | 0.65, 0.89 | 0.001 |

| Black vs White | 1.54 | 1.11, 2.14 | 0.010 |

| Others vs White | 0.90 | 0.59, 1.37 | 0.632 |

| Charlson Score 1 vs 0 | 1.31 | 1.10, 1.55 | 0.003 |

| Charlson Score 2 vs 0 | 1.80 | 1.41, 2.29 | <.0001 |

| Tumor size (unit=1cm) | 1.13 | 1.10, 1.16 | <.0001 |

| # LN sampled (unit=1) | 1.00 | 0.98, 1.01 | 0.466 |

DISCUSSION

In this study utilizing the NCDB to assemble a large cohort of patients who underwent resection of clinical stage I lung adenocarcinoma with lepidic histology, we found that lobectomy was used in the majority of patients and was associated with significantly better long-term survival compared to sublobar resection in both univariate and multivariate analysis. In this cohort of patients with what is generally considered a favorable prognosis in terms of oncologic outcomes, we observed a rate of pathologic nodal upstaging of 6% in patients who underwent lobectomy. Although sublobar resection was used in a minority of patients in the overall cohort, our results suggest that appropriate oncologic principles were often not followed when sublobar resection was utilized as less than half of these patients had pathologic lymph node analysis. The rate of nodal upstaging for sublobar resection patients who did have nodal evaluation was low but still 2.2%. Interestingly, survival when sublobar resection included lymph node sampling was not significantly different than survival after lobectomy suggesting that pathologic nodal sampling is an essential aspect of appropriate surgical oncologic management when sublobar resection is considered or utilized.

The management of predominantly GGO lung lesions, which generally correlate with lepidic predominant lesions histologically, has been reasonably well-studied both in terms of when to treat and extent of resection.12,22 For early stage disease, surgical resection remains the preferred treatment.18 A sublobar resection has been suggested to be oncologically equivalent to a lobectomy for pure GGO lesions and minimally invasive adenocarcinomas (corresponding to a solid component under 5 mm diameter).19–21 A number of single-center studies have examined the extent of surgical resection in this patient population and how it effects survival. While all of these studies were conspicuously small with relevant sample sizes ranging from 17 to 80 patients, there was no difference in long-term survival for sublobar resection compared to lobectomy among early-stage patients.1,23–25 Notably, these small studies typically have had relatively homogeneous patient populations such their results may not be truly generalizable to other types of patients. Our main finding of significantly improved survival after lobectomy when compared to sublobar resection suggests that choosing to perform a sublobar resection rather than lobectomy should only be done very carefully.

Our study does have some very interesting findings related to nodal staging. First, the rate of nodal upstaging in the setting of clinically node-negative patients is low but not zero in this cohort of patients where nodal disease is generally felt to be unlikely. This finding may have implications for when non-surgical therapy with stereotactic ablative radiation therapy is considered.26 Patients should be counselled that there is a small but real chance that that local therapy alone will be inadequate treatment. Second, the finding that performing nodal evaluation at the time of sublobar resection improves survival is also very interesting. Conceptually explaining why nodal sampling would improve outcomes is difficult, even if nodal removal itself is actually therapeutic or if identifying a positive node leads to adjuvant theapy that improves prognosis given the small rate of nodal upstaging overall in the cohort. However, this phenomenon has been observed before. In a study of NSCLC not limited to lepidic disease, Wolf and colleagues demonstrated that overall and recurrence-free survival following sublobar resection were similar to that after lobectomy as long as lymph nodes were sampled at the time of sublobar resection.27 While our results demonstrate that only 5.1% of stage I patients are subsequently upstaged due to nodal disease, the addition of lymph node sampling to sublobar resection is associated with a clear survival benefit. The addition of lymph node sampling may be a marker that a more appropriate oncologic procedure was performed not only in regards to lymph node evaluation but also in achieving appropriate margins to ensure adequate resection. However, it is also possible that there was selection bias for patients in whom lymph node evaluation was not performed in that surgeons preferentially did not sample or dissect lymph nodes because they felt the patient’s overall prognosis was very poor irrespective of lymph node status or they felt that patient’s clinical status was impaired such that adjuvant chemotherapy was not a possibility regardless of lymph node involvement. In any case, our findings mandate that lymph node evaluation be conducted when lepidic adenocarcinoma is surgically resected.

Our findings indicate that sublobar resection with nodal sampling may be an acceptable alternative to lobectomy in select cases. This is particularly relevant in the context of our aging patient population. The median patient age in our national study cohort was 69 years, with 39% of patients bearing substantial medical comorbidities (Charlson/Deyo score ≥ 1). Given the advanced age and comorbidity burden, sublobar resection offers numerous potential advantages. Potential advantages include preservation of pulmonary function and lower incidence of perioperative morbidity.28 However, as mentioned above, the decision to choose intentional sublobar resection even for lepidic adenocarcinoma should be made very carefully, especially until data from randomized trials comparing lobectomy and sublobar resection become available for analysis.21 It should be noted that there is a crossing of sublobar and lobectomy survival curves after about three years, where the survival for sublobar patients is slightly better in the earlier time period, but then it becomes significantly worse than lobectomy. Clinically, the slight early advantage observed for sublobar resections could be due to slightly higher procedural morbidity for lobectomy patients. The poorer survival after three years could be due to the other comorbid conditions for the sublobar patients, though it was in this later time period where the benefit of lobectomy over sublobar resection for early-stage lung cancer was noted to become apparent in the landmark randomized lung cancer study group trial that established lobectomy as the gold standard surgical therapy for clinical stage IA NSCLC.29

While lepidic adenocarcinoma often presents as a multifocal disease, our study focuses on stage I disease, limiting our results to the management of solitary nodules, but also allowing for clinical equipoise between lobectomy and sublobar resection.30 It should be noted that our results are applicable to patients who have pathologically proven lepidic adenocarcinoma, which is not necessarily known prior to definitive surgical treatment. In a clinical setting, our results are most applicable in the treatment settings where the likelihood of a lepidic histology is considered high due to radiographic appearance, race, and smoking history.

This study does have inherent limitations associated with its retrospective nature. Although multivariable regression can adjust for measured covariates, residual unmeasured confounding cannot be excluded. The NCDB does not identify reasons for specific surgical approaches and extent of resection, and it is possible that treatment was planned as a sublobar resection based on tumor characteristics. Conversely, some of the patients treated with lobectomy were likely never candidates for sublobar resection due a more central tumor location, which may bias our results in favor of sublobar resection if the prognosis for central tumors is not equivalent to that of peripheral tumors. In addition, the multivariable analysis with adjustments for age, tumor size, and co-morbidities attempted to control for selection bias, but there is still a chance that there were unmeasured characteristics that could not controlled for and lobectomy may have been preferentially chosen for healthier patients or those who were clinically felt to have a good chance at longevity with a lung cancer cure. Therefore, we may be overestimating the benefit of lobectomy over sublobar treatment, and this could be supported by our late crossing survival curves (Figure 1). Similarly, segmentectomies and wedge resections were considered together as sublobar resections because the majority of sublobar resections in the cohort were wedge resections and the segmentectomy group was too small for subgroup analysis. However, some studies have suggested that segmentectomy may be oncologically superior for NSCLC and our results are most likely applicable to a comparison between lobectomy and wedge resection.31,32

The use of NCDB registry data inherently also precludes knowing the degree of lepidic histology including the amount of GGO involvement or degree of microscopic invasiveness. Several studies have shown that the solid diameter of a part-solid lesion is more predictive of biology than the total diameter of the lesion.7,8,33–36 It is possible that the distribution of lepidic histology in the tumors in each group was not balanced. Therefore, our results are only applicable to adenocarcinomas with lepidic histology and an invasive component based on histology and tumor behavior known at the time of treatment. We can’t comment on the impact of changes over time of lepidic tumor size for lesions that were watched for a period of time with serial imaging prior to surgical treatment

Lepidic adenocarcinoma also often present as a multifocal disease, and therefore the presence of other radiographic abnormalities may have influenced the choice of surgical treatment;.11,30,37,38 Given the lack of radiographic characteristics within the NCDB, our analysis is not able to adjust for this potential clinical feature. Likewise, the extent of lymph node analysis in terms of dissection versus sampling is unknown. The actual lymph node count has been previously questioned given the variability across pathological processing. However, we have included the absolute count allowing readers to make their own inference on the extent of lymph node assessment.

In addition, the NCDB contains limited data regarding patient comorbidities and no information regarding pulmonary function measurements and functional status. We also did not have access to data regarding the presence of an EGFR mutation or the ALK fusion oncogene. While both of these have been implicated as important in guiding postoperative management of lepidic lung cancer, this is likely less important given the early stage of disease in our population.39,40 Additionally, the NCDB lacks details regarding the staging modalities used to establish a clinical stage I diagnosis. Rates of clinical under staging may have differed between groups if availability of staging modalities was not balanced between patients treated with lobectomy and sublobar resection. Similarly, changes during the study period in use of staging modalities may have led to systematic variations in stage migration over time, particularly as endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) and positron emission tomography (PET) may have increased in use toward the latter years of the study. Lastly, the study may not necessarily be generalizable to all stage 1 patients. In this study, both T1 and T2 patients were included in the analysis because the objective of the study was to consider the impact of resection extent on outcomes for lepidic adenocarcinoma in situations where the clinical node status was negative, because both surgical procedures are often feasible for patients with radiographic suggestion of lepidic histology regardless of tumor size. Separate T1 and T2 subgroup analyses were not performed because the sample size for T2 of sublobar resection cohort was relatively small at N=87. However, The Cox survival model results regarding the effect of surgery on survival were found to be stable even when clinical T factor was added as a potential predictor (data not shown), suggesting that the results were not biased by one type of surgery being used preferentially for T1 or T2 lesions.

Despite these limitations, the NCDB has the considerable strength of being powered to investigate a relatively uncommon pathologic subtype of NSCLC within a specific cancer substage. In light of the uncommon nature of lepidic adenocarcinoma, even if a randomized prospective trial were to be conducted among early-stage patients, such a trial would enroll orders of magnitude less patients than the present study, thereby emphasizing the generalizability of our results. Based on these results, providers can utilize our data when evaluating patients who based on their experience and clinical assessment are felt to have a high probability of having lepidic histology. Surgeons should only very carefully utilize sublobar resection and must always include adequate lymph node evaluation when treating patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma with lepidic features.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest:

One of the authors (T.A.D.) serves as a consultant for Scanlan International, Inc.

Disclosure of Funding:

This work was supported by the NIH funded Cardiothoracic Surgery Trials Network (M.G.H.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Breathnach OS, Kwiatkowski DJ, Finkelstein DM, Godleski J, Sugarbaker DJ, Johnson BE, et al. Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma of the lung: recurrences and survival in patients with stage I disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;121(1):42–47. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.110190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakagiri T, Sawabata N, Morii E, Inoue M, Shintani Y, Funaki S, et al. Evaluation of the new IASLC/ATS/ERS proposed classification of adenocarcinoma based on lepidic pattern in patients with pathological stage IA pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;62(11):671–677. doi: 10.1007/s11748-014-0429-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, Nicholson AG, Geisinger KR, Yatabe Y, et al. International Association for the study of lung cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society: international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma: executive summary. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011;8(5):381–385. doi: 10.1513/pats.201107-042ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Read WL, Page NC, Tierney RM, Piccirillo JF, Govindan R. The epidemiology of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma over the past two decades: analysis of the SEER database. Lung Cancer. 2004;45(2):137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barsky SH, Cameron R, Osann KE, Tomita D, Holmes EC. Rising incidence of bronchioloalveolar lung carcinoma and its unique clinicopathologic features. Cancer. 1994;73(4):1163–1170. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940215)73:4<1163::aid-cncr2820730407>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trigaux JP, Gevenois PA, Goncette L, Gouat F, Schumaker A, Weynants P. Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: computed tomography findings. Eur Respir J. 1996;9(1):11–16. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09010011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burt BM, Leung AN, Yanagawa M, et al. Diameter of Solid Tumor Component Alone Should be Used to Establish T Stage in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(Suppl 3):1318–1323. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4780-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsutani Y, Miyata Y, Nakayama H, et al. Prognostic significance of using solid versus whole tumor size on high-resolution computed tomography for predicting pathologic malignant grade of tumors in clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma: a multicenter study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143(3):607–612. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsutani Y, Miyata Y, Yamanaka T, et al. Solid tumors versus mixed tumors with a ground-glass opacity component in patients with clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma: prognostic comparison using high-resolution computed tomography findings. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoue M, Minami M, Sawabata N, et al. Clinical outcome of resected solid-type small-sized c-stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37(6):1445–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gu B, Burt BM, Merritt RE, et al. A dominant adenocarcinoma with multifocal ground glass lesions does not behave as advanced disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(2):411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee HY, Choi YL, Lee KS, et al. Pure ground-glass opacity neoplastic lung nodules: histopathology, imaging, and management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202(3):W224–W233. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim HJ, Ahn S, Lee KS, et al. Persistent pure ground-glass opacity lung nodules >/= 10 mm in diameter at CT scan: histopathologic comparisons and prognostic implications. Chest. 2013;144(4):1291–1299. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakurai H, Dobashi Y, Mizutani E, Matsubara H, Suzuki S, Takano K, et al. Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma of the lung 3 centimeters or less in diameter: a prognostic assessment. Ann of Thorac Surg. 2004;78(5):1728–1733. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yim J, Zhu LC, Chiriboga L, Watson HN, Goldberg JD, Moreira AL. Histologic features are important prognostic indicators in early stages lung adenocarcinomas. Mod Path. 2007;20(2):233–241. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warth A, Muley T, Meister M, et al. The novel histologic International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society classification system of lung adenocarcinoma is a stage-independent predictor of survival. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(13):1438–1446. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshizawa A, Sumiyoshi S, Sonobe M, et al. Validation of the IASLC/ATS/ERS lung adenocarcinoma classification for prognosis and association with EGFR and KRAS gene mutations: analysis of 440 Japanese patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(1):52–61. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182769aa8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Akerley W, et al. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 6.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(5):515–524. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsutani Y, Miyata Y, Nakayama H, et al. Oncological outcomes of segmentectomy compared with lobectomy for clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma: propensity score-matched analysis in a multicenter study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146(2):358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsutani Y, Miyata Y, Nakayama H, et al. Appropriate sublobar resection choice ground glass opacity–dominant clinical stage IA adenocarcinoma. Wedge resection or segmentectomy. Chest. 2014;145(1):66–71. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakurai H, Asamura H. Sublobar resection for early-stage lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2014;3(3):164–172. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2014.06.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pederson JH, Saghir Z, Wille MM, Thomsen LH, Skov BG, Ashraf H. Ground-Glass Opacity Lung Nodules in the Era of Lung Cancer CT Screening: Radiology, Pathology, and Clinical Management. Oncology (Williston Park) 2016;30(3):266–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harpole DH, Bigelow C, Young WG, Jr, Wolfe WG, Sabiston DC. Alveolar cell carcinoma of the lung: a retrospective analysis of 205 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;46(5):502–507. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)64685-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watanabe S, Watanabe T, Arai K, Kasai T, Haratake J, Urayama H. Results of wedge resection for focal bronchioloalveolar carcinoma showing pure ground-glass attenuation on computed tomography. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73(4):1071–1075. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03623-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamato Y, Tsuchida M, Watanabe T, Aoki T, Koizumi N, Umezu H, et al. Early results of a prospective study of limited resection for bronchioloalveolar adenocarcinoma of the lung. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71(3):971–974. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02507-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan H, Rose BS, Simpson DR, Mell LK, Mundt AJ, Lawson JD. Clinical practice patterns of lung stereotactic body radiation therapy in the United States: a secondary analysis. Am J Clin Oncol, 2013;36(3):269–272. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3182467db3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolf AS, Richards WG, Jaklitsch MT, Gill R, Chirieac LR, Colson YL, et al. Lobectomy versus sublobar resection for small (2 cm or less) non-small cell lung cancers. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92(5):1819–1823. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.06.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keenan RJ, Landreneau RJ, Maley RH, Singh D, Macherey R, Bartley S, et al. Segmental resection spares pulmonary function in patients with stage I lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(1):228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ginsberg RJ, Rubinstein LV. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Study Group. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995 Sep;60(3):615–622. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00537-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson WH. Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma masquerading as pneumonia. Respir Care. 2004;49(11):1349–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kent M, Landreneau R, Mandrekar S, Hillman S, Nichols F, Jones D, et al. Segmentectomy versus wedge resection for non-small cell lung cancer in high-risk operable patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(5):1747–1754. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okada M, Nishio W, Sakamoto T, Uchino K, Yuki T, Nakagawa A, et al. Effect of tumor size on prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: the role of segmentectomy as a type of lesser resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129(1):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakamura S, Fukui T, Taniguchi T, et al. Prognostic impact of tumor size eliminating the ground glass opacity component: modified clinical T descriptors of the tumor, node, metastasis classification of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(12):1551–1557. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maeyashiki T, Suzuki K, Hattori A, Matsunaga T, Takamochi K, Oh S. The size of consolidation on thin-section computed tomography is a better predictor of survival than the maximum tumour dimension in resectable lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;43(5):915–918. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuguma H, Oki I, Nakahara R, et al. Comparison of three measurements on computed tomography for the prediction of less invasiveness in patients with clinical stage I non–small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95(6):1878–1884. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hwang EJ, Park CM, Ryu Y, et al. Pulmonary adenocarcinomas appearing as part-solid ground-glass nodules: is measuring solid component size a better prognostic indicator? Eur Radiol. 2015;25(2):558–567. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3441-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mun M, Kohno T. Efficacy of thoracoscopic resection for multifocal bronchioloalveolar carcinoma showing pure ground-glass opacities of 20 mm or less in diameter. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134:877–882. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim HK, Choi YS, Kim J, Shim YM, Lee KS, Kim K. Management of multiple pure ground-glass opacity lesions in patients with bronchioloalveolar carcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:206–210. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c422be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inamura K, Takeuchi K, Togashi Y, Nomura K, Ninomiya H, Okui M, et al. EML4-ALK fusion is linked to histological characteristics in a subset of lung cancers. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3(1):13–17. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31815e8b60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller VA, Riely GJ, Zakowski MF, Li AR, Patel JD, Heelan RT, et al. Molecular characteristics of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma subtype, predict response to erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(9):1472–1478. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]