Abstract

Goals

To characterize patients who suffer perforation in the context of EoE and to identify predictors of perforation

Background

Esophageal perforation is a serious complication of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE).

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of the UNC EoE clinicopathologic database from 2001–2014. Subjects were included if they had an incident diagnosis of EoE and met consensus guidelines, including non-response to a PPI trial. Patients with EoE who had suffered perforation at any point during their course were identified, and compared to EoE cases without perforation. Multiple logistic regression was performed to determine predictors of perforation.

Results

Out of 511 subjects with EoE, 10 (2.0%) had experienced an esophageal perforation. While those who perforated tended to have a longer duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis (11.4 vs. 7.0 years, p=0.13), a history of food impaction (OR 14.9; 95% CI 1.7–129.2) and the presence of a focal stricture (OR 4.6; 1.1–19.7) were the only factors independently associated with perforation. Most perforations (80%) occurred after a prolonged food bolus impaction, and only half of individuals (5/10) carried a diagnosis of EoE at the time of perforation; none occurred after dilation. Six patients (60%) were treated with non-operative management, and four (40%) required surgical repair.

Conclusion

Esophageal perforation is a rare but serious complication of eosinophilic esophagitis, occurring in approximately 2% of cases. Most episodes are due to food bolus impaction or strictures, suggesting that patients with fibrostenotic disease due to longer duration of symptoms are at increased risk.

Keywords: perforation, eosinophilic esophagitis, food impaction, endoscopy, complication

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a recently recognized disorder characterized by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and eosinophilic infiltration of the esophagus that persists despite acid blockade.1–3 The hallmark symptoms in adolescents and adults with EoE are dysphagia and food impaction, which are often secondary to fibrostenotic changes in the esophagus due to chronic eosinophilic inflammation.2, 3 Despite being a recently-defined condition, the prevalence of EoE continues to increase, and gastroenterologists and allergists now commonly encounter patients with eosinophilic esophagitis.4–6

Esophageal perforation is a potentially life-threatening complication of EoE, and can occur in the setting of prolonged retching as spontaneous Boerhaave’s syndrome,7–9 as a complication of esophageal food bolus impaction or retching during endoscopy, or after mechanical dilation of esophageal strictures in EoE.9–11 Inflammatory changes and fragility of the esophageal mucosa, as well as esophageal remodeling, are thought to increase the risk for spontaneous or iatrogenic esophageal perforation. Despite once being considered a relatively common complication following endoscopic dilation in EoE,9–11 rates of iatrogenic perforation in EoE have been shown to be similar to rates after dilation of other stenotic esophageal conditions.12–17 Esophageal food bolus impaction (EFBI), however, continues to pose significant risk to EoE patients, as unrecognized EoE can dramatically increase the risk of spontaneous perforation following emesis and retching.7 However, little is known about the context in which esophageal perforation occurs or predictors of perforation.

The aim of this study was to identify and characterize patients with EoE whose course was complicated by esophageal perforation, and to determine risk factors for predictors of perforation.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of the University of North Carolina EoE clinicopathologic database from 2001–2014. This database contains information on patients of all ages who had an incident diagnosis of EoE; details of this database have been published previously.18–22 Subjects were included if they met consensus guidelines for EoE1, 3 including symptoms of esophageal dysfunction (such as dysphagia, food impaction, heartburn, or feeding intolerance), an esophageal biopsy with at least 15 eosinophils in at least one high-power field (eos/hpf) after a high-dose trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), and other causes of esophageal eosinophilia excluded. Of note, with the database including dates prior to the 2007 EoE diagnostic guidelines, we required confirmation that patients had been on a PPI for at least 8 weeks for inclusion in this study, and if we could not find documentation of this, they were excluded.

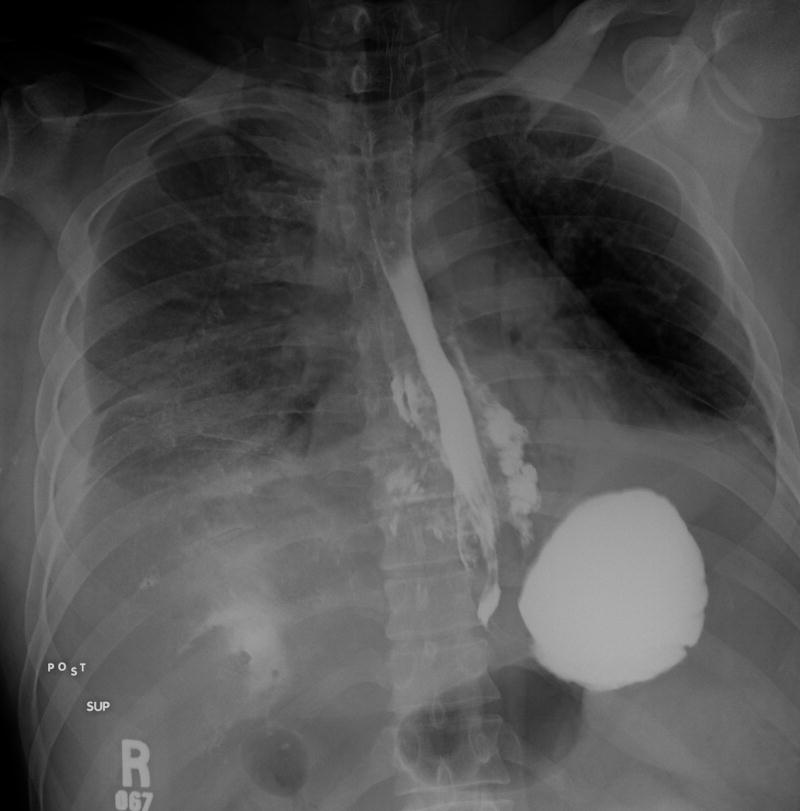

Electronic medical records were reviewed to identify all EoE patients with a history of perforation. An esophageal perforation was defined as objective evidence on an imaging test of esophageal discontinuity. These findings included intrathoracic air, paraesophageal abscess, contrast extravasation, and frank transmural rupture. Based on these findings, we classified the perforation as transmural (evidence of a full thickness disruption of the esophageal wall with contrast extravasation into the mediastinum and intrathoracic air present) or contained (evidence of esophageal disruption with intrathoracic air, but without contrast extravasation into the mediastinum). For subjects experiencing perforation, the suspected cause, treatments, and outcomes were noted. Additional data extracted included demographics, presenting symptoms, endoscopic features (such as rings, strictures, narrowing, white plaques/exudates, linear furrows, and edema), and histologic findings.

Statistical analysis was performed with Stata version 13 (Statacorp, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data, and bivariate analyses were performed using Student’s t-test, chi-square test, and Fisher’s exact test where appropriate to compare features of EoE cases with and without perforation. Multivariable analysis was performed with logistic regression to assess for independent predictors of perforation. This study was approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board.

Results

Clinical characteristics of EoE cases with and without perforation

Out of 511 subjects with EoE, 10 (2.0%) were identified who experienced an esophageal perforation. Patients with perforation were more likely to have a history of dysphagia (100% vs. 68%, p=0.04) and food impaction (80% vs. 33%, p=0.003) (Table 1). Those who perforated tended to be older at diagnosis (36 vs. 26 years, p=0.10) and have a longer duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis (11.4 vs. 7.0 years, p=0.13) compared to those who did not, although these differences did not reach statistical significance. Rates of atopic disease and food allergies were similar in both groups. Patients suffering perforation tended to have more typical EoE findings on upper endoscopy, including a diffuse narrowing (30% vs. 14%, p=0.15) and focal stricturing (60% vs. 18%, p=0.004). Maximum esophageal eosinophils did not differ between the two groups (Table 1). In a multivariate regression model including length of symptoms prior to diagnosis, age at EoE diagnosis, history of food impaction, and presence of a focal stricture on EGD, a history of food impaction was the strongest predictor of experiencing esophageal perforation (OR 14.9; 95% CI 1.7–129.2). The only other factor independently associated with experiencing perforation was the presence of a focal stricture (OR 4.6; 1.1–19.7).

Table 1.

Characteristics of EoE patients with and without esophageal perforation

| Perforation (n = 10) | No perforation (n = 501) | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, mean yrs ± SD | 36.3 ± 9.4 | 26.3 ± 18.9 | 0.10 |

| Symptom length prior to diagnosis, mean yrs ± SD | 11.4 ± 7.2 | 7.0 ± 8.7 | 0.13 |

| Male, n (%) | 7 (70) | 358 (72) | 1 |

| White, n (%) | 9 (90) | 405 (82) | 1 |

| Symptoms, n (%)ŧ | |||

| Dysphagia | 10 (100) | 335 (68) | 0.04 |

| Food impaction | 8 (80) | 156 (33) | 0.003 |

| Heartburn | 2 (20) | 187 (39) | 0.19 |

| Chest pain | 2 (20) | 49 (10) | 0.28 |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (10) | 107 (22) | 0.70 |

| Failure to thrive | 0 (0) | 57 (12) | 0.38 |

| Food allergies | 3 (30) | 103 (24) | 0.71 |

| Any atopic disease | 3 (30) | 173 (37) | 0.75 |

| Baseline endoscopic findings, n (%) | |||

| Normal endoscopy | 0 (0) | 75 (15) | 0.37 |

| Rings | 7 (70) | 219 (44) | 0.12 |

| Narrowing | 3 (30) | 68 (14) | 0.15 |

| Stricture | 6 (60) | 88 (18) | 0.004 |

| Linear furrows | 6 (60) | 237 (48) | 0.53 |

| White plaques | 3 (30) | 136 (27) | 1 |

| Decreased vascularity | 2 (20) | 113 (23) | 1 |

| Max eosinophil counts, mean eos/hpf ± SD | 76.3 (84.9) | 79.8 (75.3) | 0.89 |

SD, standard deviation; eos, eosinophils; HPF, high-power field

P values calculated using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and chi-squared test for categorical variables.

Information on symptoms collected at time of diagnostic endoscopy. Information available for eleven out of twelve individuals who suffered perforation

Perforation details, treatments, and outcomes

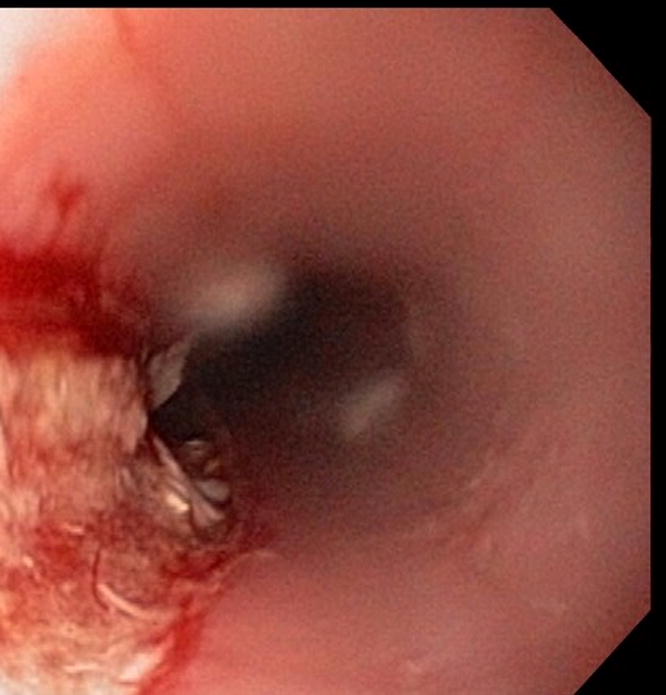

Details for all 10 patients who experienced a perforation are presented in Tables 2 and 3, and representative images are shown in Figure 1. At the time of esophageal perforation, patients had a mean age of 33.5 years. 80% (8/10) of perforations occurred in the setting of a food impaction, either spontaneously or after attempted endoscopic removal of a food bolus. Four individuals had perforations during or post-endoscopy; patients carried a diagnosis of EoE in 1/4 of these cases. Overall, only half of individuals who experienced perforation (5/10) carried a diagnosis of EoE at the time of perforation, and none of these individuals were on topical steroids when the perforation occurred (note: topical steroids are not approved by the FDA for treatment of EoE). Perforation occurred in a community practice setting for 60% of the cases (6/10) and in an academic/tertiary care center for the other four cases (40%). Six patients (60%) were treated with non-operative management, usually consisting of bowel rest and IV antibiotics. The remaining four (40%) required surgical repair of the esophageal perforation; posterior thoracotomy was performed in three and left thoracotomy was performed in one. No minimally-invasive surgical approaches or endoscopic stenting/closure techniques were used. The esophagus could be closed primarily in 3 cases, but due to tissue disruption and inflammation, a T-tube was used to repair the esophagus in the fourth case. Four of the six patients with a transmural esophageal perforation were preferentially managed with surgical intervention. No individuals with a contained perforation underwent surgery. Patients stayed a mean of 7.3 days in the hospital (range 3–12) after their perforation, with those having surgery requiring more time (9.5 vs. 5.8 days on average).

Table 2.

Clinical details and EoE history among those with perforation

| Overall (n = 10) | Perforation before 10/2007** (n=4) | Perforation after 10/2007** (n=6) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EoE diagnosed at time of perf, n (%) | 5 (50) | 1 (25) | 4 (80) |

| On treatment at time of perf* | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Occurred in community | 6 (60) | 2 (40) | 4 (67) |

| Associated with food impaction | 8 (80) | 3 (75) | 4 (67) |

| Required surgery | 4 (40) | 2 (50) | 2 (33) |

| Prior esophageal dilationŧ | 2 (20) | 1 (25) | 1 (17) |

SD, standard deviation

Among those carrying a diagnosis of EoE

Before or after release of consensus recommendations on diagnosis and treatment of EoE.

Denotes patient who received esophageal dilation at any point during course of disease prior to developing perforation

Table 3.

Clinical vignettes of individuals with esophageal perforation

| Case # | Patient age (years) | Sex | Prior symptoms | Presentation/Course | Had surgery? | Final dx | EoE Dx known? | Assoc with food impaction? | Ever dilated prior? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | Male | History of chronic dysphagia, heartburn | 4 days of severe abdominal pain. CT showed paraesophageal abscess, no visible air. Barium swallow showed no contrast extravasation. Treated conservatively with IV antibiotics and bowel rest. Discharged after 8-day hospitalization. | No | Contained perforation | Yes | No | Yes |

| 2 | 36 | Female | Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis, dysphagia for 8–10 years | Presented with inability to swallow secretions after eating cereal. Had urgent endoscopy at outside center, during which food was dislodged and balloon dilation was performed. Returned 5 hours post-procedure with severe abdominal pain and chest pain. Negative barium swallow. CT Chest performed, showed pneumomediastinum. Treated with IV antibiotics and bowel rest. Discharged after 7-day hospitalization. | No | Transmural perforation | No | Yes | No |

| 3 | 32 | Male | Asthma, dysphagia, hx of food impactions. | Presented to ER with chest pain and hematemesis 3 hours after eating lettuce. Then vomited food and blood. Barium swallow showed intramural esophageal tear. Chest CT showed gas dissecting into wall of esophagus and bilateral pleural effusions. Treated with IV antibiotics and bowel rest. Discharged after 5-day hospitalization. | No | Transmural perforation | Yes | Yes | No |

| 4 | 47 | Male | History of asthma, esophageal perforation in past | Presented to ER with sore throat ×1 week, fever to 101° F for 1 day. CT demonstrated circumferential thickening of the distal esophagus with a loculated paraesophageal fluid collection. Treated with IV antibiotics, fluids, and bowel rest. Discharged home after 3-day hospitalization. | No | Contained perforation | Yes | No | Yes |

| 5 | 43 | Male | None | Presented to ER with 6 hours of abdominal pain, chest pain, after eating nachos. Barium swallow showed extravasation of contrast and moderate R pleural effusion. Taken to OR, underwent R thoracotomy with evacuation of empyema and primary closure of esophagus. Discharged after 11-day hospitalization. | Yes | Transmural perforation + empyema | No | Yes | No |

| 6 | 19 | Male | Childhood allergies to cats, dogs | Presented to ER with inability to swallow secretions 4 hrs after eating steak. Had EGD with disimpaction of food, but returned to ER with severe chest pain. Barium swallow negative for contrast extravasation. CT showed para-esophageal gas and pneumomediastinum. Treated with IV antibiotics and bowel rest. Discharged home after 7-day hospitalization. | No | Contained perforation | Yes | Yes | No |

| 7 | 42 | Male | Asthma, GERD | Presented to ER with chest pain and feeling that food was stuck, 8 hrs after eating chicken. EGD performed, food bolus removed piecemeal. Immediately post-procedure, had severe chest pain, crepitus. CXR showed pneumomediastinum with air tracking into neck. The pt. underwent left thoracotomy with primary closure of the esophagus. He was discharged home after 6-day hospitalization. | Yes | Transmural perforation | No | Yes | No |

| 8 | 29 | Female | None | Presented to ER with inability to swallow secretions after eating meat, passed after glucagon administration. Several days later, had routine outpatient EGD, scope unable to be passed. Perforation observed during procedure. Patient given IV antibiotics, bowel rest, and observed. Discharged after 5-day hospitalization. | No | Transmural perforation | No | Yes | No |

| 9 | 33 | Female | Seasonal allergies, GERD | Presented to ER with severe abdominal pain 15 hours after eating chicken, after several episodes of emesis. Barium swallow showed contrast extravasation and pneumomediastinum. Pt was taken to the OR for thoracotomy; had primary closure of the esophagus. Discharged after 12-day hospitalization. | Yes | Transmural perforation | No | Yes | No |

| 10 | 28 | Male | None | Presented to outside ER with severe chest and epigastric pain ×3–4 hours after eating a piece of pot roast. CXR showed pneumomediastinum. Patient emergently transferred for surgical evaluation. Underwent a left thoracotomy with T-tube repair of esophagus. Discharged after 9-day hospitalization. | Yes | Transmural perforation | Yes | Yes | No |

Figure 1.

Examples of esophageal perforations in EoE patients. (A) Endoscopic view of a deep mucosal rent concerning for an esophageal perforation. (B) Noncontrasted chest CT scan in a different patient demonstrating diffuse esophageal wall thickening with associated paraesophageal stranding. A small amount of free mediastinal air can be seen (arrow), as well as paraesophageal fluid suggestive of phlegmon vs. abscess, suggesting a transmural perforation. (C) Barium swallow in a different patient with free extravasation of contrast into the mediastinum consistent with a transmural perforation.

Discussion

Esophageal perforation is a serious and feared complication of EoE, but it has not been extensively investigated. In this study, we analyzed a large cohort of more than 500 adults and children with EoE, and found that only 10 had previously suffered esophageal perforation. 40% of these cases required surgical repair, and there were no deaths related to either surgery or perforation. Notably, more than three-quarters of the perforations were complications of esophageal food impaction, three were likely iatrogenic from endoscopic manipulation, and none of the patients who perforated were on anti-inflammatory EoE-specific treatment at the time of perforation.

This report greatly augments the literature regarding perforation in the setting of EoE. In the existing literature, spontaneous esophageal perforation has been described in 22 cases published over 16 articles (Table 4), and 13 cases were associated with food impaction.7, 8, 23–35 When the 10 cases presented here are added to those previously reported in the literature,7, 8, 23–35 21 out of a total of 32 reported perforations in EoE have been associated with food bolus impaction. This association may be explained by several factors. First, EoE patients can have mucosal fragility, commonly manifest by shearing or tearing of the esophageal wall with passage of the endoscope.36, 37 Second, EoE can lead to fibrostenotic changes in the esophagus, including deposition of collagen in the laminal propria, focal stricturing, diffuse narrowing, decreased compliance, and altered motility.18, 38–40 These mechanical changes cause dysphagia and predispose to food impaction. In certain individuals, this process can deteriorate into a severe phenotype in which the esophagus is narrowed along its entire length.41,7, 9, 30, 42–45 Third, patients with EoE often have a long duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis15, 17, 30, 46–48 and modify their eating behaviors to minimize symptoms. Because they may be used to transient impactions, they may not seek care rapidly, which might lead to esophageal injury from the impacted food. Finally, when food is acutely impacted and endoscopy is performed, it is a higher risk procedure. For example, in the Swiss EoE database, of 87 patients experiencing 137 food impactions, there were three perforations, two during rigid esophagoscopy to remove the food bolus and one Boerhaave’s syndrome due to retching during the procedure.7

Table 4.

Literature Review – Prior Studies That Describe Spontaneous Esophageal Perforation in EoE.

| Author | Year | # Perfs | # Associated with food impaction | # Treated Surgically | Method of Diagnosis (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fischer | 2015 | 1 | 0 | 0 | EGD |

| Jacobs | 2015 | 2 | 2 | 0 | CT Chest |

| Vernon | 2015 | 2 | 1 | 0 | CT Chest, EGD |

| Van Rhijn | 2014 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Chest X-ray |

| Jackson | 2013 | 4 | 0 | 2 | CT Chest |

| Predina | 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Chest X-ray |

| Fontillon | 2012 | 1 | 1 | 1 | EGD |

| Lucendo | 2011 | 2 | 2 | 2 | CT Chest, Chest X-ray |

| Quiroga | 2009 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Barium swallow |

| Liguori | 2008 | 1 | 1 | 1 | CT Chest |

| GÓmez | 2008 | 1 | 1 | 0 | CT Chest |

| Straumann | 2008 | 1 | 0 | 1 | EGD |

| Cohen | 2007 | 1 | 0 | 1 | CT Chest |

| Prasad | 2005 | 1 | 1 | 0 | CT Chest |

| Mecklenberg | 2005 | 1 | 1 | 0 | EGD |

| Riou | 1996 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Barium swallow |

|

| |||||

| TOTALS, n (%) | 22 | 13 (59) | 9 (41) | CT Chest: 12 (55) EGD: 5 (23) Chest X-ray: 3 (14) Barium swallow: 2 (9) |

|

In the literature overall, esophageal perforation is reported to have a high morbidity and mortality, and among those with spontaneous perforation the mortality is reported at approximately 33%.49, 50 While the mortality from perforation is not known in EoE, we did not identify any deaths in our cohort or in the published EoE literature. This would suggest that mortality from esophageal perforation may be lower than that associated with perforation in the general population. One factor that could impact this is the severity of the perforation, whether it is contained or transmural with mediastinal or pleural contamination. Of our cases with transmural perforation, 4 required surgery and had longer hospitalizations and recoveries. In the EoE literature, there are 12 cases with documented full-thickness perforations identified by contrast leak or frank pneumomediastinum out of a total of 22 reported perforations.7, 8, 23–35 In addition, EoE patients who suffer perforation do so at a relatively young age (mean 32.5 yrs in this cohort), and this likely improves their morbidity after surgery.

Methods to reduce the risk of perforation have not been elucidated. Data from pediatric EoE cohorts suggest reversal of lamina propria fibrosis with topical steroid or dietary elimination therapy,51, 52 but similar results have not been seen in adults where fibrosis at both the microscopic and macroscopic/endoscopic level tends to persist after anti-inflammatory treatment.53–55 Additionally, adults with EoE are likely to have longer periods of untreated inflammation, increasing the risk of fibrotic complications such as food impaction,38 as well as endoscopic findings such as diffusely narrow esophagus or strictures.18, 38, 56 However, even in adulthood, there may be opportunities to reduce the risk of perforation. In a retrospective study, Kuchen et al found that treatment with topical corticosteroids significantly reduced the risk of food impaction (OR 0.41).57 In addition, dilation of strictures or narrowing may decrease the risk of food impactions, but this has not been studied in detail.13, 14, 16, 58

There may be practical ways to reduce perforation risk as well, especially in the peri-procedural period. In our series, 4 out of 8 patients who presented for acute EFBI had an upper endoscopy shortly after presentation. In 3 cases (patients 2, 7, and 8) the perforation was identified either in the endoscopy suite or over the next few hours; in 1, dilation was performed during the urgent endoscopy after the food was removed (done at an outside center). Based on this, we feel the following suggestions should be considered. First, we recommend that endoscopists do not blindly push the bolus forward, as this could cause injury or perforation at a more distal stricture or narrowing site. Second, the endoscopist should always visualize the tip of the instrument they are using (e.g., roth net, grasper device, etc) and avoid passing these instruments blindly. Third, dilation in the setting of an EFBI is likely high-risk due to underlying mucosal injury from the food bolus, and we typically do not dilate patients at the time of an acute food bolus impaction. However, we do agree with the recommendation to obtain routine esophageal biopsies at the time of the food impaction, because the pretest probability of EoE in this setting is high.2, 59, 60 If a recognized or suspected esophageal perforation occurs, urgent surgical consultation is recommended to assist in management.

This study has several limitations. As a retrospective study, there is potential loss to follow-up, so individuals who had a perforation but sought care at another institution would not be captured in these data. This would lead to an underestimation of the risk of perforation in our cohort. There was no standardized protocol for how a perforation should be diagnosed/confirmed and our patients presented with a variety of clinical manifestations of perforation. We also could not fully characterize the details of the food bolus impaction, including the length of time the bolus had been present. Additionally, we present data from a single tertiary center, so the results may not be generalizable to other settings. However, strengths of the study include a large cohort of EoE cases, with detailed demographic and clinical characteristics reported using standardized criteria, that allowed for an analysis of predictors of perforation. We also report the largest series of esophageal perforations yet described in EoE, increasing the number of perforations reported in the literature by more than 50%.

In conclusion, esophageal perforation is a rare but severe complication of eosinophilic esophagitis. Most perforations occurred either at the time of a food impaction in patients with unrecognized EoE, or in patients who were not actively being treated for EoE and had a food impaction. No perforations were seen after dilation. Despite greater recognition of EoE by gastroenterologists, patients have long delays in diagnosis, and it is difficult to predict who may develop severe complications of EoE such as esophageal perforation. Therefore, physicians should have a high suspicion for previously unrecognized or untreated EoE in patients presenting with food impaction, as well as for the possibility that esophageal perforation can complicate food impaction. Future study of mechanical and medical treatment of adults with EoE is needed to determine the optimal way to mitigate perforation risk in this population.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: This research was supported, in part, by NIH awards T32DK007634 (TMR), T35DK007386 (CMB), K24DK100548 (NJS), K23DK090073 (ESD), and R01DK101856 (ESD).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None of the authors report any potential conflicts of interest pertaining to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Children and Adults: A Systematic Review and Consensus Recommendations for Diagnosis and Treatment: Sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute and North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(4):1342–1363. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, et al. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;108(5):679–692. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2011;128(1):3–20.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dellon ES, Jensen ET, Martin CF, et al. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in the United States. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2014;12(4):589–596.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellon E, Erichsen R, Baron J, et al. The increasing incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis outpaces changes in endoscopic and biopsy practice: national population - based estimates from Denmark. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2015;41(7):662–670. doi: 10.1111/apt.13129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hruz P, Straumann A, Bussmann C, et al. Escalating incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis: a 20-year prospective, population-based study in Olten County, Switzerland. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2011;128(6):1349–1350.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Straumann A, Bussmann C, Zuber M, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: analysis of food impaction and perforation in 251 adolescent and adult patients. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology. 2008;6(5):598–600. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riou PJ, Nicholson AG, Pastorino U. Esophageal rupture in a patient with idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1996;62(6):1854–1856. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(96)00553-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen MS, Kaufman AB, Palazzo JP, et al. An audit of endoscopic complications in adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2007;5(10):1149–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan M, Mutlu EA, Jakate S, et al. Endoscopy in eosinophilic esophagitis:“feline” esophagus and perforation risk. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2003;1(6):433–437. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(03)00222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenbach C, Merle U, Schirmacher P, et al. Perforation of the esophagus after dilation treatment for dysphagia in a patient with eosinophilic esophagitis. Endoscopy. 2006;38:E43. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoepfer AM, Gonsalves N, Bussmann C, et al. Esophageal dilation in eosinophilic esophagitis: effectiveness, safety, and impact on the underlying inflammation. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;105(5):1062–1070. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung KW, Gundersen N, Kopacova J, et al. Occurrence of and risk factors for complications after endoscopic dilation in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2011;73(1):15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ally M, Dias J, Veerappan G, et al. Safety of dilation in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Diseases of the Esophagus. 2013;26(3):241–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2012.01363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Rubinas TC, et al. Esophageal dilation in eosinophilic esophagitis: safety and predictors of clinical response and complications. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2010;71(4):706–712. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipka S, Keshishian J, Boyce HW, et al. The natural history of steroid-naive eosinophilic esophagitis in adults treated with endoscopic dilation and proton pump inhibitor therapy over a mean duration of nearly 14 years. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2014;80(4):592–598. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Runge TM, Eluri S, Cotton CC, et al. Outcomes of Esophageal Dilation in Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Safety, Efficacy, and Persistence of the Fibrostenotic Phenotype. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2016 doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dellon ES, Kim HP, Sperry SL, et al. A phenotypic analysis shows that eosinophilic esophagitis is a progressive fibrostenotic disease. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2014;79(4):577–585.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Fritchie KJ, et al. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2009;7(12):1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dellon ES, Chen X, Miller CR, et al. Diagnostic utility of major basic protein, eotaxin-3, and leukotriene enzyme staining in eosinophilic esophagitis. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;107(10):1503–1511. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolf WA, Jerath MR, Sperry SL, et al. Dietary elimination therapy is an effective option for adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf WA, Cotton CC, Green DJ, et al. Predictors of response to steroid therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis and treatment of steroid-refractory patients. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2015;13(3):452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer A, Höppner J, Richter-Schrag HJ. First Successful Treatment of a Circumferential Intramural Esophageal Dissection with Perforation in a Patient with Eosinophilic Esophagitis Using a Partially Covered Self-Expandable Metal Stent. Journal of Laparoendoscopic & Advanced Surgical Techniques. 2015;25(2):147–150. doi: 10.1089/lap.2014.0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vernon N, Mohananey D, Ghetmiri E, et al. Esophageal Rupture as a Primary Manifestation in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Case reports in medicine. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/673189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs J, Fatima H, Cote G, et al. Stenting of Esophageal Perforation in the Setting of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2015;4(60):1098–1100. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3387-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Rhijn BD, Curvers WL, Bergman JJ, et al. Esophageal perforation during endoscopic removal of food impaction in eosinophilic esophagitis: stent well spent? Endoscopy. 2013;46:E193–4. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson WE, Mehendiratta V, Palazzo J, et al. Boerhaave’s syndrome as an initial presentation of eosinophilic esophagitis: a case series. Annals of gastroenterology: quarterly publication of the Hellenic Society of Gastroenterology. 2013;26(2):166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Predina JD, Anolik RB, Judy B, et al. Intramural esophageal dissection in a young man with eosinophilic esophagitis. Annals of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2012;18(1):31–35. doi: 10.5761/atcs.cr.10.01629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fontillón M, Lucendo AJ. Transmural eosinophilic infiltration and fibrosis in a patient with non-traumatic Boerhaave’s syndrome due to eosinophilic esophagitis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2012;107(11):1762–1762. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lucendo A, Friginal - Ruiz A, Rodriguez B. Boerhaave’s syndrome as the primary manifestation of adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Two case reports and a review of the literature. Diseases of the Esophagus. 2011;24(2):E11–E15. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2010.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quiroga J, Prim JMG, Moldes M, et al. Spontaneous circumferential esophageal dissection in a young man with eosinophilic esophagitis. Interactive cardiovascular and thoracic surgery. 2009;9(6):1040–1042. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2009.208975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liguori G, Cortale M, Cimino F, et al. Circumferential mucosal dissection and esophageal perforation in a patient with eosinophilic esophagitis. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2008;14(5):803. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gómez SS, Adán ML, Froilán TC, et al. Spontaneous esophageal rupture as onset of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterologia y hepatologia. 2008;31(1):50–51. doi: 10.1157/13114577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prasad G, Arora A. Spontaneous perforation in the ringed esophagus. Diseases of the Esophagus. 2005;18(6):406–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2005.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mecklenburg I, Weber C, Folwaczny C. Spontaneous recovery of dysphagia by rupture of an esophageal diverticulum in eosinophilic esophagitis. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2006;51(7):1241–1242. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-8042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA. Advances in Clinical Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(6):1238–1254. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Straumann A, Rossi L, Simon HU, et al. Fragility of the esophageal mucosa: a pathognomonic endoscopic sign of primary eosinophilic esophagitis? Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2003;57(3):407–412. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Straumann A, Aceves S, Blanchard C, et al. Pediatric and adult eosinophilic esophagitis: similarities and differences. Allergy. 2012;67(4):477–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kwiatek MA, Pandolfino JE, Hirano I, et al. Esophagogastric junction distensibility assessed with an endoscopic functional luminal imaging probe (EndoFLIP) Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2010;72(2):272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.01.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwiatek MA, Hirano I, Kahrilas PJ, et al. Mechanical properties of the esophagus in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(1):82–90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eluri S, Runge TM, Cotton CC, et al. The Extreme Narrow-Caliber Esophagus is a Treatment Resistant Sub-Phenotype of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2016;83(6):1142–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fox VL, Nurko S, Furuta GT. Eosinophilic esophagitis: it’s not just kid’s stuff. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2002;56(2):260–270. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Dohil R, et al. Esophageal remodeling in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2007;119(1):206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aceves SS. Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 2015;35:145–159. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rothenberg ME, Mishra A, Brandt EB, et al. Gastrointestinal eosinophils in health and disease. Advances in immunology. 2001;78:291–328. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(01)78007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Straumann A. The natural history and complications of eosinophilic esophagitis. Thoracic surgery clinics. 2011;21(4):575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Attwood SE, Smyrk TC, Demeester TR, et al. Esophageal eosinophilia with dysphagia. Digestive diseases and sciences. 1993;38(1):109–116. doi: 10.1007/BF01296781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Straumann A, Spichtin H, Bernoulli R, et al. Idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis: a frequently overlooked disease with typical clinical aspects and discrete endoscopic findings. Schweizerische medizinische Wochenschrift. 1994;124(33):1419–1429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mavroudis CD, Kucharczuk JC. Acute Management of Esophageal Perforation. Current Surgery Reports. 2014;2(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brinster CJ, Singhal S, Lee L, et al. Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2004;77(4):1475–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aceves S, Newbury R, Chen D, et al. Resolution of remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis correlates with epithelial response to topical corticosteroids. Allergy. 2010;65(1):109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chehade M, Sampson HA, Morotti RA, et al. Esophageal subepithelial fibrosis in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2007;45(3):319–328. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31806ab384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lucendo AJ, Arias Á, De Rezende LC, et al. Subepithelial collagen deposition, profibrogenic cytokine gene expression, and changes after prolonged fluticasone propionate treatment in adult eosinophilic esophagitis: a prospective study. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2011;128(5):1037–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, et al. Budesonide is effective in adolescent and adult patients with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(5):1526–1537.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dellon ES, Cotton CC, Gebhart JH, et al. Accuracy of the Eosinophilic Esophagitis Endoscopic Reference Score in Diagnosis and Determining Response to Treatment. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2016;14(1):31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(6):1230–1236.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuchen T, Straumann A, Safroneeva E, et al. Swallowed topical corticosteroids reduce the risk for long - lasting bolus impactions in eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy. 2014;69(9):1248–1254. doi: 10.1111/all.12455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saligram S, McGrath K. The safety of a strict wire-guided dilation protocol for eosinophilic esophagitis. European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2014;26(7):699–703. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sperry SL, Crockett SD, Miller CB, et al. Esophageal foreign body impactions: epidemiology, time trends, and the impact of the increasing prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2011;75(5):985–91. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hiremath GM, Hameed F, Pacheco A, et al. Esophageal food impaction and eosinophilic esophagitis: A retrospective study, systematic review, and meta-analysis. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2015;60(11):3181–93. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3723-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]