Abstract

Clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 enables us to generate targeted sequence changes in the genomes of cells and organisms. However, off-target effects have been a persistent problem hampering the development of therapeutics based on CRISPR/Cas9 and potentially confounding research results. Efforts to improve Cas9 specificity, like the development of RNA-guided FokI-nucleases (RFNs), usually come at the cost of editing efficiency and/or genome targetability. To overcome these limitations, we engineered improved chimeras of RFNs that enable higher cleavage efficiency and provide broader genome targetability, while retaining high fidelity for genome editing in human cells. Furthermore, we developed a new RFN ortholog derived from Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 and characterize its utility for efficient genome engineering. Finally, we demonstrate the feasibility of RFN orthologs to functionally hetero-dimerize to modify endogenous genes, unveiling a new dimension of RFN target design opportunities.

Keywords: CRISPR/Cas9, gene editing, FokI, RNA-guided FokI nuclease

Havlicek et al. test the influence of different peptide linkers on the performance of RNA-guided FokI-nucleases (RFNs) to identify novel chimeras with improved genome targetability, DNA cleavage efficiencies, and high fidelity. They also characterize RFNs developed from Staphylococcus aureus and highlight the potential for hetero-dimerization of RFN orthologs.

Introduction

Programmable nucleases like zinc finger nucleases, transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), and clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 can be harnessed to induce DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) at specific sites in genomes of interest.1 Through cellular repair pathways, like nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair, insertions and deletions (indels) or specific sequence changes can be introduced at the DSBs, respectively. To induce DSBs, Cas9 complexes with a target-specific guide RNA (gRNA) that is required for DNA binding and nuclease activation.2, 3 In addition, a Cas9-specific protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) juxtaposed to the target sequence is required for nuclease activation.2, 4 Target length, gRNA sequence, Cas9 protein, and their respective PAM requirements differ among various type II CRISPR/Cas systems.5, 6, 7 For the most commonly used Cas9 derived from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), a 17- to 20-base pair (bp) target length and an NGG PAM motif define target specificity.2, 3

Several groups have reported high-frequency off-target effects when using SpCas9. This has driven efforts to improve cleavage specificity, including the use of truncated gRNAs, the generation of a partially inactivated Cas9 known as nickase, or the recent development of SpCas9 variants (termed SpCas9-high fidelity 1 [HF1] and eSpCas9) containing targeted amino acid (aa) substitutions, rendering them more sensitive to gRNA-target DNA mismatches.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Particularly promising are the genome-wide fidelity assessments of SpCas9-HF1 and eSpCas9, through which the authors were able to show considerable improvements in SpCas9 specificity for most target sites tested, while often retaining at least 70% of wild-type (WT) SpCas9 efficiency. However, off-target modifications were still detectable in a subset of tested gRNAs, which was evident from targeted amplicon deep sequencing and/or unbiased genome-wide DNA double-strand break capturing assays like genome-wide, unbiased identification of DNA double strand breaks enabled by sequencing (GUIDE-seq).12, 16 Furthermore, for a subset of targets, the on-target modification efficiency rate dropped to less than 40% of WT SpCas9, sometimes even to undetectable levels, suggesting the need for further improvements.

An alternative approach for genome editing with high specificity is by the use of RNA-guided FokI-nucleases (RFNs). The RFN system is derived from an enzymatically dead Cas9 (dCas9) from S. pyogenes fused to the dimerization-dependent FokI nuclease domain.17, 18 Like zinc finger nucleases and TALENs, this system is active only as a dimer, requiring the simultaneous binding of two FokI-dCas9 monomers at adjacent target sites in a “PAM-out” orientation (that is, N termini of dCas9 facing each other), which enables the homo-dimerization of FokI. The two FokI-dCas9 monomers are guided to the target site by separate, independent gRNAs. Thus, although one monomer might still bind an off-target site, it is unable to introduce a DSB.17, 18, 19 However, the improvements in specificity using RFNs have come at a cost of cleavage efficiency and genome targetability (i.e., the number of target sites in the genome). One of the major factors restricting the genome targetability is the limited spatial distance tolerated between paired RFNs for functional dimerization (referred to as the “spacer distance”).17, 18 The spacer distance is defined as the number of base pairs separating the two binding sites of the respective gRNAs. It has been demonstrated that RFNs are most effective with spacer distances of 14–17 bp and that they have a vastly improved specificity profile, outperforming WT SpCas9 and Cas9 nickase.17, 18 Despite the much improved specificity of RFNs, the limiting spacer distance between a pair of RFNs generates restrictions in the genome targetability. A target site must fit the motif of CCNN20 (i.e., left target site, non-target strand), followed by a 14- to 17-bp random sequence (i.e., spacer), followed by N20NGG (i.e., right target site) (Figure 1A). Given these specifications, much fewer genomic loci are amenable to modification as compared with WT SpCas9. Another drawback of the RFN system is the large size of this fusion chimera, hampering its adaption to adeno-associated virus (AAV) expression systems, the preferred method for the in vivo delivery of gene-editing nucleases.

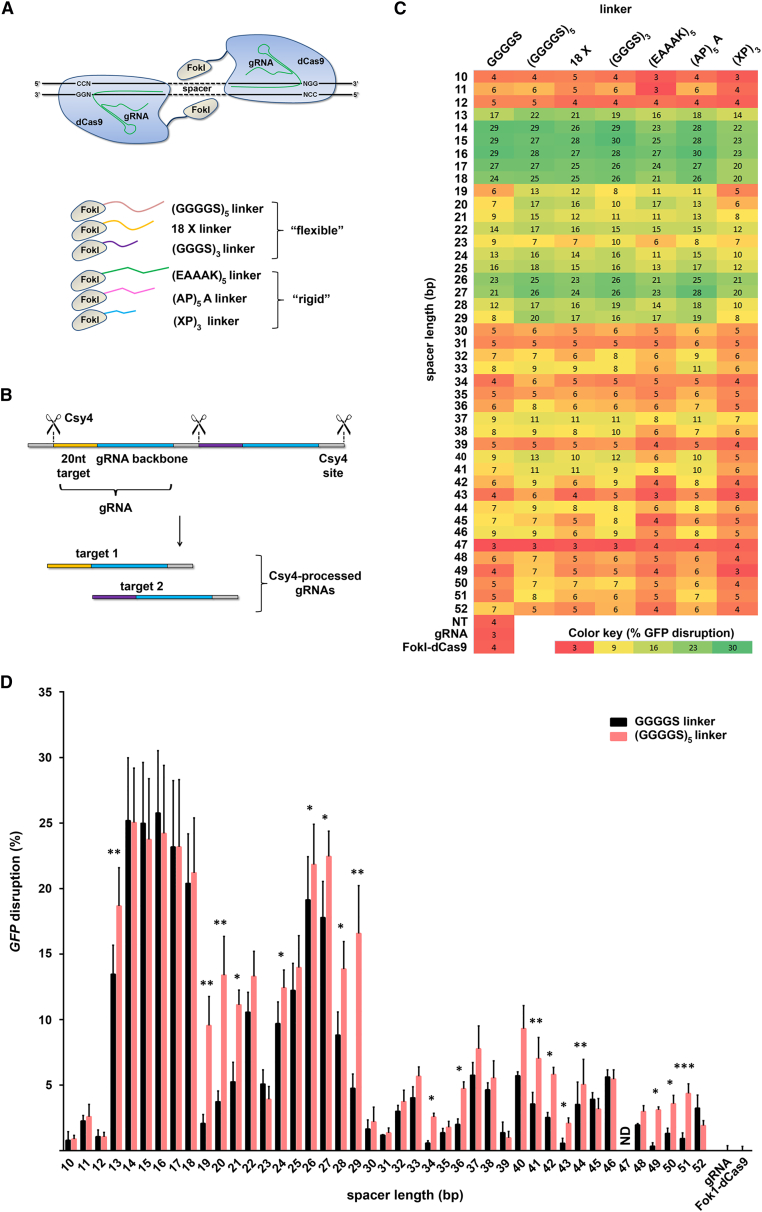

Figure 1.

Characterization of RNA-Guided FokI Nucleases Containing Various Peptide Linkers

(A) Two monomers of SpRFNs are recruited to neighboring target sites by two different guide RNAs. Spatial proximity defined by the “spacer” allows dimerization of the FokI domains and DNA cleavage. New peptide linkers for the fusion of the FokI domain to dCas9 are shown and categorized into “flexible” and “rigid” groups. (B) Csy4-based multiplex gRNA expression system. Csy4 recognition motif flanked gRNAs are transcribed as a single primary transcript. Csy4 nuclease-dependent cleavage separates the individual gRNAs. (C) Heatmap representation of the GFP disruption activities of different SpRFNs (linker peptide as indicated) in HEK293T-GFP cells. Target sites were separated by spacer distances of variable lengths ranging from 10 to 52 bp. GFP disruption was quantified by flow cytometry, and efficiency is indicated by color and value. Non-transfected, gRNA-only, and SpFokI-dCas9-only transfected cells served as controls; n = 3–7 biological replicates performed on different days. (D) Comparison of the GFP disruption activities of RFNs with a GGGGS and a (GGGGS)5 peptide linker. Same data as presented in (C). Error bars reflect SEM from three to seven biological replicates performed on different days. Data shown are after subtracting the background value of non-transfected cells (=3.58%). p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant; *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, two-tailed, paired t test. ND, none detected.

Protein fusion chimeras have widespread applications in biological research and biopharmaceuticals. The choice of the oligopeptide linker fusing two protein domains has pivotal consequences for the functionality and stability of the recombinant protein.20, 21 Tsai et al.18 generated an RFN variant that utilizes a 5 aa linker (GGGGS) to fuse FokI to dSpCas9. Although they have tested a broad range of spacer distances (0–30 bp) to target GFP in a GFP stable cell line, actually only a few spacing distances showed activity (14–17 and 26 bp). In contrast, Guilinger et al.17 tested a set of variants with 12 different fusion linkers, but compared them only at a small set of gRNA spacing combinations (5, 10, 14, 20, 25, 32, and 43 bp), of which most did not reveal any functionality. It remained unclear why most variants performed poorly and/or lacked activity, and also what influence the fusion linkers might have over the full spectrum of gRNA spacing possibilities. Hence, current RFN variants remain incompletely characterized, and current work lacks guidance on how to improve RFN technology. To overcome this, we designed six new RFN variants that differed in length, amino acid composition, and flexibility of the linker that separates the two functional domains within an RFN. Each newly engineered chimera was extensively characterized for performance over a broad range of spacing distances (10–52 bp). We assayed spacing distance requirements and gene modification efficiency by a well-established GFP disruption assay. These data allowed us to identify what influence the peptide linker length has on the spacing requirements of RFNs and also suggests which linkers lead to overall increased DNA cleavage efficiency. In addition, endogenous gene editing was tested in human embryonic stem cells and HEK293T cells with assessments of off-target cleavage by targeted deep sequencing.

As a second and complementary approach toward expanding RFN technology, we created a new RFN chimera derived from Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 (SaCas9). We characterized the gene-editing efficiency and spacing distance requirements of this new RFN ortholog, which uses a unique gRNA and requires a distinct PAM motif (NNGRRT), and therefore is able to target genomic loci distinct to those targeted by FokI-dSpCas9. Furthermore, because of its comparably smaller size, FokI-dSaCas9 could potentially be adapted to AAV expression systems for in vivo genome-editing applications. Intriguingly, we also reveal the finding that RFN orthologs can hetero-dimerize to efficiently modify endogenous genes. This allows new target design opportunities, in which target sites can be accessed by mixing and matching of RFN orthologs with appropriate PAM specificities.

Results

Characterizing the Gene Modification Potential of Newly Designed RFN Variants

First, we focused on SpCas9 and sought to optimize the peptide linker that fuses FokI to dCas9 with the aim to influence DNA cleavage efficiency while also providing greater versatility in gRNA spacing distances. Six new RFN variants were generated that differed in the length, amino acid composition, and flexibility of the linker that separates the two domains (Figure 1A; Table S1). To test the redesigned nucleases, we adapted a well-established GFP disruption assay,17, 18, 22 in which frameshift mutations in GFP are induced by the NHEJ repair pathway, which can be easily monitored by loss of GFP signal in the cell population. The spacer requirements for each RFN variant were assessed by co-expressing the nucleases with different pairs of gRNAs targeting the GFP locus in HEK293T-GFP cells. We adapted the gRNA expression system developed by Tsai and colleagues18 in which a pair of gRNAs is expressed from a U6 promoter as a single, hybrid RNA transcript, which is subsequently processed by the co-expressed bacterial Csy4 RNase to release the individual gRNAs (Figure 1B). We used a published RFN variant with a 5 aa (GGGGS) linker for comparison.18 In our assays, the “GGGGS” linkage variant led to efficient (>10%) loss of GFP with spacer distances of 13–18, 22, and 24–27 bp (Figures 1C and 1D). We note that the performance of this variant was underestimated in a previous report.18 With the other gRNA pairs (spacers ranging from 10 to 52 bp), we observed only low efficiencies. Importantly, our results demonstrate that RFNs with substantially longer peptide linkers induced loss of GFP at significantly increased efficiencies, independent of the flexibility of the fusion linker (Figures 1C and 1D; Figure S1). The best-performing nuclease has a flexible 25 aa (GGGGS)5 linker, which efficiently induced indels (mean 17.8 ± 5.2%, after background correction) with spacer distances of 13–29 bp, except for the 23-bp spacer. To analyze whether the lack of effectiveness of the 23-bp spacer is a target-specific issue or a general characteristic of RFNs, we designed a new pair of gRNAs to target the endogenous gene EMX1. Although both RFN variants tested were able to generate indels, the new (GGGGS)5 variant (22% indels) convincingly outperformed the GGGGS variant (9% indels) (Figure S2A), demonstrating that RFNs can effectively dimerize even at 23-bp spacer distances. In conclusion, within the large spectrum of spacer distances of 13 to 29 bp, the (GGGGS)5 variant outperformed the reference RFN at 10 of 17 target sites (mean 16.4% ± 4.2% and 9.4% ± 5.3% indels, respectively; mean 2.2 ± 1.0-fold improvement for spacer distances of 13, 19–21, 23–24, and 26–29 bp, p = 0.0002, paired t test). We noted that additional spacer distances of 37, 40, and 41 bp were effective using the (GGGGS)5 variant, albeit less efficiently (7%–10%). Despite these improvements, there appeared to be a bimodality in optimal spacing distance requirements, illustrated by two peaks of activity at the 14- to 18-bp and the 26- to 29-bp distance. This suggests that the peak activity areas are approximately separated by one turn of the DNA helix, similar to what had been described previously.17 However, this bimodality was less pronounced when targeting endogenous genes (see later), and therefore might not be generalizable to all target loci, and the effects could have been driven by gRNA-sequence or target-site-specific influences.

Recently, dCas9 has been harnessed as a transcriptional repressor tool in which dCas9 binding to a target gene led to the reduction of mRNA expression.23, 24 To demonstrate that the loss of GFP signal in our assays was the result of indel mutations and was not due to transcriptional repression, we validated our results using the independent T7 Endonuclease I assay (Figure S2B). Thus, we conclude that the efficiency of GFP disruption, as well as the versatility of gRNA spacing distances, is improved using expanded peptide linkers.

We decided to focus further analyses on three selected linkage variants based on their performance: (1) the (GGGGS)5 variant was chosen because it showed the highest and broadest efficiency profile, (2) the rigid (EAAAK)5 variant because it selectively improved in the 13- to 29-bp spacer range, and (3) the rigid (AP)3A variant because it showed the most restrictive profile. We sought to evaluate whether our findings from the GFP disruption assays hold true for the modification of endogenous genes in human cells. We generated gRNA pairs targeting nine loci in three genes (CLTA, EMX1, and VEGFA) and measured indel formation in HEK293T cells by the T7 Endonuclease I assay. We used spacing distances of 15, 19, and 29 bp. As expected, indel formation at target sites with 15-bp spacers was very effective and showed little difference among RFN variants (Figure 2A). In contrast, the (GGGGS)5 variant consistently outperformed the reference RFN at all target sites spaced 19 and 29 bp apart, except for VEGFA target site 3, where no RFN showed efficient cleavage. In conclusion, these results confirm that RFN chimera with long, flexible fusion linkers efficiently modify human endogenous genes with broadened gRNA spacer ranges, whereas nucleases with short rigid linkers perform less efficiently. Finally, we compared our (GGGGS)5 variant with another published RFN variant containing an 18 aa “XTEN” linker.17 Guided by our previous data, we expected the 18 aa linker variant to have broad spacing distance flexibility. This was confirmed in our assays targeting GFP as well as endogenous gene loci. Nevertheless, our (GGGGS)5 variant still showed improved cleavage efficiency at a subset of target sites and gRNA spacing distances (Figure S3).

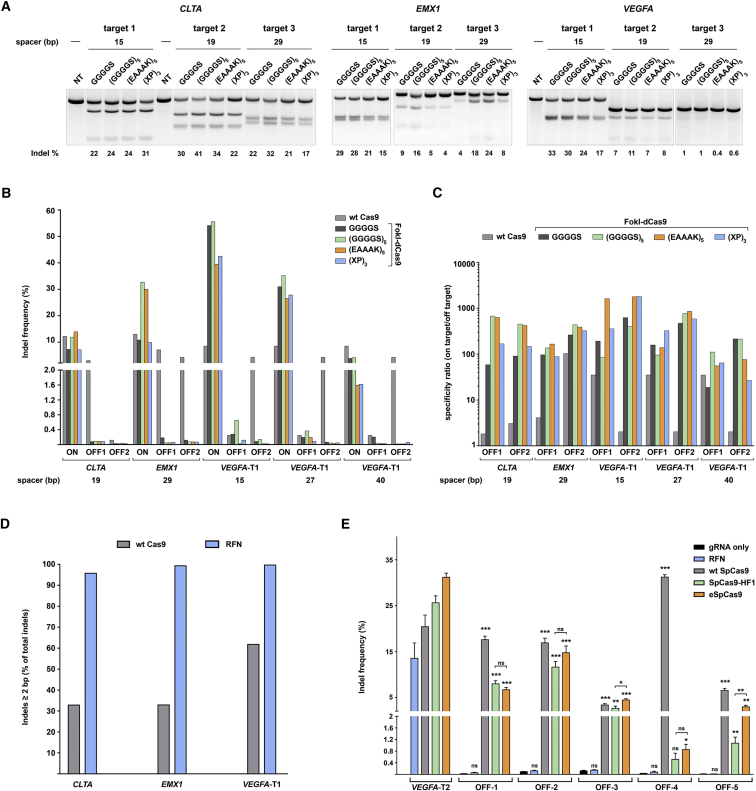

Figure 2.

Genome Modification Efficiencies and Off-Target Analyses of SpRFNs Targeting Endogenous Genes

(A) Indel modification efficiency of different RFNs targeting three sites each in CLTA, EMX1, and VEGFA in HEK293T cells. Each gene was targeted by a respective SpRFN variant co-expressed with a pair of gRNAs that were spaced 15, 19, or 29 bp apart. Gels of the T7EI assays are shown. Non-transfected cells were used as a negative control. n = 2 biological replicates; representative picture is shown. (B) Indel modification specificity of SpRFNs and WT SpCas9 determined by two deep-sequencing runs of the same library for on- and off-target sites for CLTA, EMX1, and VEGFA gRNAs. Reads with indels of ≥2 bp were considered RFN-induced mutations. The indel frequency is represented as the number of mutated sequences divided by the total number of sequences. Cells transfected with only SpRFN were used as a control (Table S3). (C) Data from (B) represented as specificity ratio, which is calculated by dividing on-target by off-target indel frequency. (D) Comparison of the amount of indels ≥2 bp between WT SpCas9 and the (GGGGS)5 RFN variant at indicated on-target sites. Reads with indels of ≥1 bp were analyzed. (E) Targeting specificity of the (GGGGS)5 RFN variant compared with WT SpCas9, SpCas9-HF1, and eSpCas9 at repetitive sequences as determined for the on-target site and five known off-target sites for VEGFA-T2 gRNA. Reads with indels of ≥2 bp were considered nuclease-induced mutations. The indel frequency is represented as the number of mutated sequences divided by the total number of sequences. Cells transfected with only the gRNA were used as a negative control. n = 3 biological replicates, error bars are SEM. Unpaired t tests were performed for the off-target sites between the negative control and the respective nucleases, unless otherwise indicated. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

Off-Target Analyses Reveal Unaltered High Fidelity of RFN Variants

Next, we evaluated whether changing the fusion linker had an adverse effect on RFN specificity. We measured RFN specificity by a commonly used approach that takes advantage of previously described gRNA target sites with identified, known off-target mutation sites.10, 14, 15 We expressed these gRNAs targeting CLTA, EMX1, and VEGFA in combination with WT SpCas9 or as paired gRNAs with different RFN variants in HEK293T cells. We measured by targeted deep sequencing the indel rates at the respective on-target sites and two corresponding known off-target sites for each gene target (Table S2). The gRNA pairs were spaced 19 (CLTA) or 29 bp (EMX1) apart, and we analyzed three different gRNA pairs targeting the same VEGFA site spaced 15, 27, or 40 bp apart. Importantly, we found that the off-target indel formation was low (indistinguishable from background) for all RFNs, while demonstrating on-target modification efficiencies of up to 55%. In contrast, WT SpCas9 induced measurable indels at most off-target sites tested (Figure 2B; Table S3). Again, the (GGGGS)5 variant outperformed all other RFNs for spacer distances of 19, 27, and 29 bp, confirming our previous findings based on the GFP disruption and T7 Endonuclease I assays. All RFNs performed strikingly better than WT SpCas9 in on-target/off-target specificity (Figure 2C). Taken together, our deep-sequencing experiments demonstrate that changing the peptide linker can significantly improve RFN performance without adversely affecting the high fidelity inherent to RFN technology. Interestingly, we also observed that monomeric SpCas9 generated substantial amounts of 1-bp indels, whereas RFN-induced indels were almost always greater than 1 bp (Figures 2D and S4). This suggests that the RFN system might be better suited than SpCas9 for assays where larger deletions are beneficial, such as for interrogating gene-regulatory elements (e.g., distal enhancers and promoters), which might not be greatly influenced by single base deletions.25, 26 Finally, we analyzed whether changing the linker peptide had any influence on the cleavage site. To address this, we plotted the raw reads containing indels for our various on-target sites (Figure S6). This revealed a strikingly similar mutation pattern among different RFN variants targeting the same gene, suggesting that the peptide linker has no influence on the DNA cleavage position (e.g., most commonly deleted nucleotide is the same among RFN variants). Instead, the mutation spectrum was mainly influenced by the gRNA spacing distance, as shown by broader mutation spectra with increasing gRNA spacing distances (Figure S5).

Recently, two groups reported on SpCas9 variants, termed SpCas9-HF1 and eSpCas9, with considerable improvements in targeting specificity for most target sites tested.12, 16 However, monomeric SpCas9 variants still perform poorly at target sites that contain repetitive or homopolymeric sequences, which have a high number of potential off-target sites in the genome.12 To compare the performance of RFNs against SpCas9-HF1 and eSpCas9 at repetitive target sites, we targeted the same locus in VEGFA as previously reported (referred to as VEGFA site 2 in Kleinstiver et al.12) and analyzed 5 of the top 10 off-target sites that were still detectable with SpCas9-HF1.12 Strikingly, there were no detectable off-target cleavage events above background at all five off-target sites when using RFNs, whereas both SpCas9-HF1 and eSpCas9 induced a substantial amount of off-target indels at all off-target sites (Figure 2E; Table S4). Nevertheless, a noticeable improvement compared with WT SpCas9 was evident, as expected. Interestingly, despite using different approaches to develop SpCas9-HF1 and eSpCas9, neither nuclease was able to avoid off-target cleavage, albeit showing subtle differences in efficiencies when compared with each other. In conclusion, we demonstrate that RFNs can target repetitive sequences without detectable off-target cleavage, and thereby establish this system as a useful alternative technology for target sites at which the improved monomeric SpCas9 variants perform poorly.

High Efficacy in Genome Editing of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells

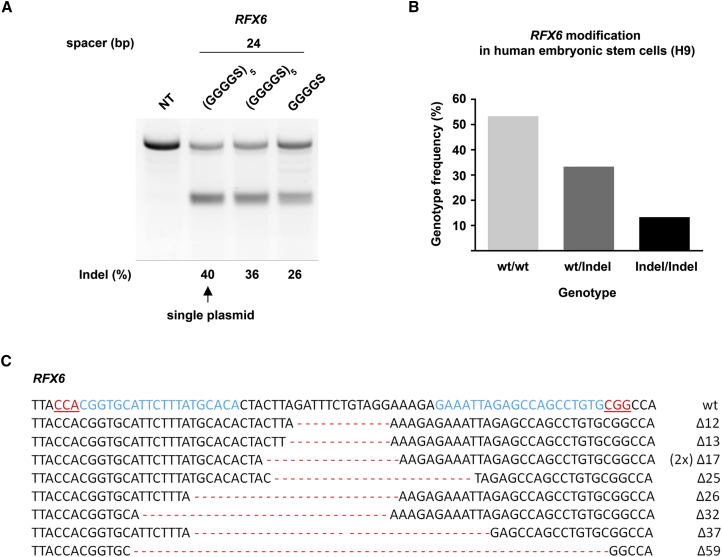

Genome editing has broad applications in disease modeling and holds potential for therapeutic interventions based on the correction of mutations in patient cells. In this respect, human pluripotent stem cells are a relevant cell type both for disease modeling and for therapeutics. To further evaluate the utility of the new (GGGGS)5 variant, we targeted RFX6 in human embryonic stem cells (H9). We chose this target because RFX6 is a transcription factor required for the differentiation of pancreatic islet cells, and mutations in RFX6 are associated with Mitchell-Riley syndrome,27, 28 making it an interesting candidate gene. Human pluripotent stem cells typically show inefficient uptake of plasmid DNA and high cytotoxicity related to electroporation. To establish more effective conditions suitable for the modification of human pluripotent stem cells, we first constructed a single plasmid that allowed us to co-express gRNAs, FokI-dCas9, and the reporter gene GFP. First, this would guarantee that successfully electroporated H9 cells received both the nuclease and the gRNAs, and second, this would allow us to use FACS to enrich for transfected cells based on GFP expression. We analyzed the modification efficiency of our new construct at the RFX6 target site (gRNA pair with 24-bp spacer) using the single-plasmid or the two-plasmid (i.e., gRNAs and RFN expressed from different plasmids) approach. This experiment revealed that even without prior GFP enrichment, our new system showed a 1.5-fold higher targeting efficiency compared with the GGGGS variant for this particular target site (40% versus 26% indels, respectively; Figure 3A). Moreover, when targeting RFX6 in H9 cells, we determined that nearly half (7/15) of single-cell-derived H9 clones carried indels in at least one allele (Figures 3B and 3C).

Figure 3.

Genome-Editing Efficiency of RFX6 in Human Embryonic Stem Cells Using the SpRFN Variant with Flexible 25 Amino Acid Linker

(A) Comparison of indel frequencies at the RFX6 target site when SpRFN variants and a pair of gRNAs are co-expressed from one plasmid or expressed from two separate plasmids in HEK293T cells. Non-transfected cells are used as a negative control. Gel of the T7EI assay is shown. Cells were not enriched for GFP prior to DNA isolation. n = 2 biological replicates performed on different days; representative image is shown. (B) RFX6 was modified in H9 cells by RFNs with the (GGGGS)5 linker using the single plasmid system. Single cells were FACS sorted for GFP expression and re-seeded at clonal density. Fifteen clones were analyzed by Sanger sequencing to determine the genotype (WT/WT = 8, WT/indel = 5, indel/indel = 2). (C) Mutated sequences detected in RFX6 of H9 clones are shown. The WT sequence is shown in the top lane with the target sites highlighted in blue text and the PAM motif underlined and in red text. Deletions are marked with red dashes, and the number of deleted bases is shown next to each sequence. The same 17-bp deletion was found in two independent clones and is indicated as “(2×).”

These results using a previously untested gene target demonstrate the high efficacy of our improved system in human pluripotent stem cells.

Development of an RFN Ortholog Derived from Staphylococcus aureus Cas9

We sought to use a second and complementary approach to further expand the genome targetability of RFNs. We reasoned that developing RFN chimera derived from Cas9 orthologs should enable us to target additional genomic loci. We engineered an RFN chimera from the recently characterized Staphylococcus aureus Cas9.4, 29, 30 We chose SaCas9 because it utilizes a unique gRNA and has distinct PAM requirements (NNGRRT > NNGRRN), and therefore targets different genomic locations than SpCas9.4 In addition, the inactivating mutations that generate a catalytically dead version of SaCas9 have been described previously. Moreover, because of its comparably compact size, it should be possible to package SaRFN into adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors, which is of high clinical relevance for the in vivo delivery of gene-editing nucleases because AAVs show low immunogenic potential, have reduced oncogenic risk of host-genome integrations compared with lentiviruses, and have a broad range of serotype specificity.31

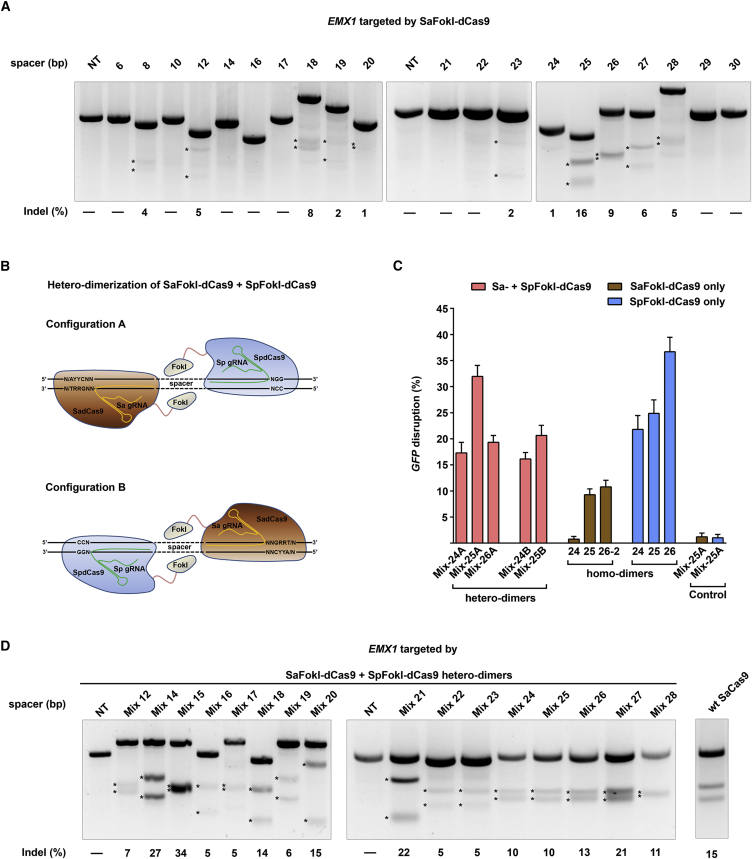

We introduced the inactivating amino acid substitutions into WT SaCas9 and then fused the FokI domain using our (GGGGS)5 linker to the N-terminal end of dSaCas9. For SpRFN, spacer distances are measured as the number of bp between the paired gRNAs (e.g., after the 20 nt target complementarity); however, SaCas9 can use gRNAs with 21 or 22 nt target complementarity.4, 29 Nevertheless, the PAM and hence the protein position do not alter with the change in gRNA length. For this reason, we define the spacer distance between a pair of SaRFNs as the number of bp between the 21st bp of the gRNA target sequences. This allows easier and more consistent comparisons among different gRNA pairs independent of gRNA target length. We assessed the GFP disruption potential and the spacer requirements of our newly developed SaRFNs in an analogous way as we did for SpRFN. Based on our data from SpRFN, we expected peak cleavage efficiencies to fall within a spectrum of 4- to 5-bp “windows” (e.g., SpFokI-dCas9 peaks are at spacer distances of 13–18 and 26–29 bp; see Figure 1D). Hence, we performed a primary spacer screen ranging from 4 to 42 bp in intervals of 2- to 4-bp steps (Figure S6). After identifying a hit, we more closely analyzed all possible spacer distances surrounding the hit by a secondary screen. This revealed that, although SaRFN was less efficient than SpRFN and more restricted in spacer distances, we observed efficient GFP disruption at spacer distances of 25 and 26 bp (Figure S6). However, WT SaCas9 has been described to cleave target sites with NNGRRN PAMs less efficiently than those with NNGRRT PAMs.4 Therefore, we note that GFP has only a few paired target sites with dual NNGRRT PAMs (Table S5), which might have attenuated the performance of SaRFN in our GFP disruption assay. Hence, we targeted EMX1 using SaRFN and tested a broad range of spacer distances ranging from 6 to 30 bp. Because EMX1 encompasses a relatively large genomic sequence, we were able to select only target sites with NNGRRT PAMs. We found that SaRFN was able to induce indels with spacer distances of 12, 18, and 25–28 bp and lower modification rates with 8-, 19-, 20-, and 23-bp spacer distances (Figure 4A). In an effort to improve SaRFN performance, we tested substituting the (GGGGS)5 linker for a smaller [= (GGGS)3 linker, 12 aa] or longer (= GSAT linker, 36 aa) fusion peptide. Whereas the smaller (GGGS)3 linker greatly reduced cutting efficiency (data not shown), the longer GSAT linker marginally improved indel formation frequency (Figure S7). Previous reports on SpRFNs suggested that only N-terminal fusions of FokI to dSpCas9 are functional.17, 18 Nevertheless, because the crystal structure of SaCas9 revealed that its C-terminal end is at the opposite side compared with its N terminus, we generated a dSaCas9-FokI C-terminal chimera (utilizing the GSAT linker). We tested this construct by targeting EMX1 using gRNAs that place the protein chimeras in the “PAM-in” orientation (C-terminal ends of dSaCas9 facing each other). However, only gRNAs that were spaced 14 bp apart led to detectable DNA cleavage (∼12% indels; Figure S8), suggesting that C-terminal fusions to dSaCas9 are not very effective, similar to with dSpCas9.

Figure 4.

Characterization of SaRFN and the Hetero-dimerization Potential with SpRFN for Genome Editing

(A) Targeting EMX1 in HEK293T cells using a variety of spacer distances ranging from 6 to 30 bp determined by T7EI assay. Only target sites with NNGRRT PAMs were chosen. Non-transfected cells served as negative controls. n = 2 biological replicates performed on different days; representative picture is shown. (B) Schematic representation of SaRFN/SpRFN hetero-dimerization. Monomers of SaRFN and SpRFN are recruited to neighboring target sites by their respective gRNA, allowing the dimerization of the FokI domains and subsequent DNA cleavage. In configuration A, SaRFN is recruited to the “left” target site and SpRFN to the “right” target site. In configuration B, the target sites are exchanged. (C) GFP disruption efficiencies of SaRFN/SpRFN hetero-dimers targeted in configuration A or B with 24-, 25-, or 26-bp spacer distances. Note that there is no matching target site in GFP for configuration B using a 26-bp spacer. HEK293T-GFP cells were co-transfected with three plasmids encoding: (1) SaRFN, (2) SpRFN, and (3) a pair of multiplexed gRNAs to assess GFP disruption efficiency. Only target sites with NNGRRT PAMs were used for SaFokI-dCas9 target sites. Cells targeted with the respective homo-dimers of SaRFN or SpRFN and their cognate gRNA pairs or the “mixed” gRNAs are shown. Data shown are after background correction of non-transfected cells (=3.59%). n = 3–5 biological replicates. (D) EMX1 indel frequency determined by T7EI assay in cells targeted by SaRFN/SpRFN hetero-dimers using a variety of spacer distances. Only target sites with NNGRRT PAM were used for SaRFN target sites. EMX1 indel frequency induced by WT SaCas9 with a single cognate gRNA is shown as a reference. Non-transfected cells were used as a negative control. n = 2 biological replicates, representative picture shown. Asterisks indicate the expected cleaved DNA fragments.

RFN Orthologs Can Functionally Hetero-dimerize

Intriguingly, our data show that both SaRFNs and SpRFNs functionally dimerize and efficiently modify genes when their target sites are spaced 25 to 28 bp apart. This led us to hypothesize that these two RFN orthologs could hetero-dimerize to execute gene editing (Figure 4B). This would be an advantage because paired target sites requiring one Sa PAM (e.g., left target site) and one Sp PAM (e.g., right target site) are statistically more prevalent in the genome than target sites requiring dual “Sa-PAMs.” To evaluate the hetero-dimer potential of RFN orthologs, we adapted our expression system to enable the co-expression of one Sa gRNA and one Sp gRNA, then tested the ability of Sa/Sp-RFN hetero-dimers to disrupt GFP with spacer distances of 24–26 bp. The hetero-dimer approach allows two possible configurations, for example, guiding FokI-dSaCas9 to the left target site, whereas FokI-dSpCas9 targets the right site, or vice versa (Figure 4B). Hence, we analyzed both possible configurations in our GFP assay. Interestingly, all tested target sites showed efficient GFP disruption (20.8 ± 5.9%, after background correction), and this effect was dependent on the co-expression of both nuclease orthologs (Figure 4C). Interestingly, the hetero-dimers were even more efficient at disrupting GFP than the SaRFN homo-dimers with equivalent spacer distances, although this effect was dependent on SaRFN target sites having NNGRRT PAMs (Figure S9).

Finally, we sought to determine whether Sa/Sp-RFN hetero-dimers can efficiently modify human endogenous genes. We targeted EMX1 using the hetero-dimer approach and a broad spectrum of spacer distances ranging from 12 to 28 bp. We observed that Sa/Sp-RFN hetero-dimers were able to modify EMX1 at all tested spacer distances (Figure 4D). Particularly, spacing distances of 14, 15, 18, 20, 21, 26, and 27 bp worked most efficiently.

Taken together, by introducing SaRFNs for genome editing, we have further enhanced the genome targetability of RFNs compared with the system solely based on SpRFNs, and provide greater design flexibility in gene targeting. Moreover, the smaller SaRFN (∼3,900 bp) could be adapted to AAV expression vectors for the in vivo delivery of RFNs. Although at this point the Csy4-processed multiplexed gRNAs would need to be expressed from a separate AAV vector, future studies exploring alternative gRNA expression systems such as using ribozymes or tRNAs to express the dual gRNAs might help to overcome this limitation.32, 33 We have compiled an overview of the various RFN systems in respect to computational predicted target sites in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of Binding Motifs and Potential Target Sites in the Human Genome of Various RFN Systems and WT SpCas9

| Nuclease | Binding Motif (Including PAM, gRNA Target, and Spacer Sequence) | Binding Sites in the Human Genome | Average Distance between Cleavage Sites (bp)a | Coverage of Protein Coding Exons (of 237,140 Total) (%) | Coverage of lincRNA Exons (of 22,949 Total) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpRFN (GGGGS linker) | CCN55–60GGb | 30,778,083 | mean: 91.2 (SD: ±128.2) median: 46 | 88.6 | 87.7 |

| SpRFN [(GGGGS)5 linker] | CCN55–71GG | 62,436,462 | mean: 46.4 (SD: ±72.0) median: 21 | 96.3 | 96.5 |

| SaRFN | AYYCN64GRRT + AYYCN71–74GRRT | 2,738,812 | mean: 398.6 (SD: ±288.3) median: 356 | 28.1 | 30.1 |

| SaRFN/SpRFN heterodimers | AYYCN56–72GG or CCN56–72GRRT | 45,725,064 | mean: 63.9 (SD: ±85.2) median: 33 | 94.2 | 94.5 |

| WT SpCas9 | N21GG | 240,886,617c | mean: 12.4 (SD: ±14.1) median: 8 | 99.9 | 99.9 |

bp, base pairs; lincRNA, long intergenic non-coding RNA; RFN, RNA-guided FokI-nuclease; Sa, Staphylococcus aureus; Sp, Streptococcus pyogenes.

Two binding motifs that lead to the same predicted cleavage location were counted as one motif. Cleavage sites with maximum distance of 1,000 bp between neighboring sites were included.

Spacing distance as recommended in Tsai et al.18

Target sites on both DNA strands were evaluated.

Discussion

The importance of the CRISPR/Cas9 system is emphasized by its ease of use and widespread potential applications ranging from healthcare, agriculture, and the development of gene drives to its use as a basic research tool.1, 34, 35 Whatever the application, the specificity of targeting and cutting only the intended locus is a fundamental challenge, and recent reports of high-frequency off-target effects of SpCas9 have raised concerns.8, 10, 13 Several strategies to improve SpCas9 specificity have been approached, including altering the design of gRNAs,3, 36 generating partially inactivated SpCas9 nickases,15, 37 using split Cas9 approaches,38, 39 or simply shortening the exposure time of the genome to active Cas9/gRNA complexes.40, 41 An elegant alternative approach termed RNA-guided FokI nucleases (RFN) is based on the design of the well-studied zinc finger nucleases and TALENs. RFNs take advantage of a catalytically dead Cas9 fused to the dimerization-dependent FokI domain.17, 18 Because this strategy requires the simultaneous binding of two FokI-Cas9 monomers in the right orientation (PAM-out orientation) and in a defined spatial distance (e.g., 13–29 bp apart) to activate the nuclease function, it has an appealingly high fidelity profile.17, 18, 19 Nevertheless, all approaches to increase the specificity of genome cleavage typically come at the cost of gene-editing efficiency and/or the number of targetable loci.

We show here that redesigning the peptide linker fusing the FokI domain and dCas9 can improve the gene-editing efficiency in human cells, as well as the spacing distance flexibility for functional dimerization of two RFN monomers. This increases the genome targetability of the RFN technology. We have shown the efficacy of our new variants by targeting the transgene GFP, as well as the endogenous genes CLTA, EMX1, VEGFA, and RFX6. Importantly, our improved (GGGGS)5 variant efficiently edits genes in a human cell line (HEK293T) as well as in human pluripotent stem cells (H9), providing proof for the robustness of the system.

Determining the off-target cleavage sites and mutation rates of gene-editing nucleases has been one of the most challenging problems in the field. Recent advances in the “unbiased” genome-wide identification of these events have provided important insights into the nature and frequency of off-target cleavage by some nucleases.9, 11, 16, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 However, the limitations of these methods include the detection limit of cleavage events below 1% frequency using integration-deficient lentivirus (IDLV) capture,45 the non-physiological assessment of in vitro activity of Cas9-sgRNA complexes by Digenome-seq coupled with extensive whole genome sequencing,11 the non-compatibility of GUIDE-seq with efficiently capturing DSBs containing nucleotide overhangs (such as produced by FokI-based systems),43 the high cell number needed for the rare detection of translocation events via HTGTS,9 or the lack of evidence for the compatibility of BLESS or Digenome-seq with FokI-based systems.42 Moreover, a recent report highlighted the long binding lifetime of Cas9-DNA and dCas9-DNA complexes,47 suggesting RFN-DNA complexes have different dynamics from TALEN-DNA interactions, and hence genome-wide off-target assessment strategies that are compatible with TALENs might not necessarily work efficiently with RFNs. An alternative, commonly used approach to determine nuclease specificity takes advantage of previously described gRNA target sites with identified, known off-target mutation sites.10, 14, 15, 18 We assessed the indel frequency at six known off-target sites of three genes (CLTA, EMX1, VEGFA) using either WT SpCas9 or different variants of RFNs. Strikingly, in the 20 conditions using RFNs, indel frequency was mostly indistinguishable from background. This shows that our approach to improve RFN performance does not affect RFN fidelity. More generally, our data suggest that other systems that harness dCas9 protein fusions to effector domains might also be improved by altering their respective peptide linker.23, 48, 49, 50, 51

Type II CRISPR/Cas systems are characterized by their single, large effector protein Cas9.5, 6 Cas9 orthologs from different bacteria have been identified, characterized, and harnessed for gene editing in bacteria and mammalian cells, including Cas9 from Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, and Neisseria.2, 4, 7 However, to date, only Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes has been adapted to RFN technology. We reasoned that RFNs derived from Cas9 orthologs would be an important step forward in expanding the genome targetability of this system. We developed and characterized SaRFN derived from the recently described Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. SaCas9 utilizes a unique gRNA and requires a distinct PAM, which enables the targeting of different loci. SaRFNs worked most efficiently when using gRNAs with 21 nt target complementarity and at target sites containing NNGRRT PAMs, similarly to what has been described for WT SaCas9.4 Although the efficiency of indel formation and the spacing distance is more restrictive compared with SpRFNs, we show that human endogenous genes can be efficiently modified using SaRFNs when gRNA pairs are spaced 18 bp or 25–28 bp apart. Intriguingly, we reveal that hetero-dimers of RFN orthologs efficiently edit the genome. The advantage of this approach is that the heterodimer editing efficiency is substantially higher than that of SaRFN homodimers. In addition, paired target sites for SpRFN/SaRFN heterodimers are more prevalent in the human genome than for SaRFN homodimers. Together, these findings substantially improve existing RFN technology, and we envision that the development of additional FokI-dCas9 orthologs or RFNs from Cas9 proteins with relaxed PAM specificities will further enhance this system.7, 12, 29, 52 Importantly, our newly developed RFN from S. aureus could be adapted to AAV expression systems, paving the road for the development and characterization of in vivo therapeutics based on RFN technology, for which a first step should be to test the immunogenic risk that RFN expression constitutes in vivo. Although at this point the Csy4-processed multiplexed gRNAs would need to be expressed from a separate AAV vector, future studies exploring alternative gRNA expression systems such as using ribozymes or tRNAs to express the dual gRNAs might help to overcome this limitation.32, 33

Recently, two groups reported on SpCas9 variants that harbored a combination of targeted amino acid substitutions at residues that either participate in interactions with the non-target DNA strand or participate in target DNA strand interactions, termed SpCas9-HF1 and eSpCas9, respectively.12, 16 In both studies, the authors were able to show considerable improvements in SpCas9 specificity for most target sites tested, while often retaining 70% of WT SpCas9 efficiency. These variants have the advantage of functioning in the monomeric form, which requires the design and expression of only one gRNA, compared with the dual-gRNA approach of the RFN system. However, off-target modifications were still detectable in a subset of tested gRNAs, which was evident from targeted amplicon deep sequencing and/or unbiased genome-wide DNA double-strand break capturing assays like GUIDE-seq.12, 16 Furthermore, monomeric SpCas9 variants still perform poorly for targets that contain repetitive or homopolymeric sequences, which have a high number of potential off-target sites in the genome.12 Finally, for a subset of targets, the on-target modification efficiency dropped below 40% of WT SpCas9, sometimes even to undetectable levels.12, 16 Taken together, this highlights the need for further improvements of monomeric Cas9 variants and/or the development of complementary systems that can substitute for SpCas9 at poor-performing target sites. We believe that the dimerization-dependent RFN system described here offers an attractive alternative, particularly at repetitive or homopolymeric target sites, because we did not detect any off-target mutations at five loci tested, whereas SpCas9-HF1 and eSpCas9 readily induced indels. We tested only one on-target site and five off-target sites, and therefore this should not be considered a comprehensive off-target analysis. Nonetheless, this is a novel and important comparison of SpCas9-HF1 and eSpCas9. In our hands, eSpCas9 showed slightly higher on-target activity at VEGFA-T2, but also higher off-target modification rates at two of five loci. Nevertheless, the overall performance between these two nucleases was strikingly similar, suggesting that the positions of the amino acid substitutions each variant carries did not influence the off-target discrimination at the tested loci. It will be important to test whether a novel SpCas9 variant carrying the combined amino acid alterations (or a combination thereof) of both SpCas-HF1 and eSpCas9 will help to further improve fidelity or whether the effects are not cumulative. It will also be interesting to see whether the amino acid substitutions described for the improved SpCas9 variants might also help to further improve specificity of the RFN system (if needed). Alternatively, recent progress on the development of altered FokI variants such as the Sharkey mutants could further improve RFN technology.12 Ultimately, there is an urgent need to develop or adapt an unbiased genome-wide off-target detection method that shows robust, reliable performance with a high sensitivity for all different nuclease systems, which will allow the direct comparison of eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1, RFNs, Cpf1, and TALENs at a multitude of different target loci, but also to characterize their performance in various cell types. Specifically concerning the RFN system, this would allow us to unbiasedly investigate whether DNA cleavage absolutely necessitates the simultaneous binding of two FokI-dCas9 monomers, or whether a single bound monomer is able to recruit its partner from solution, thereby potentially inducing unintended off-target mutations. Future studies will investigate these issues.

Overall, we have shown that a long, flexible linker fusing the FokI domain to dCas9 improves RFN performance without adversely affecting DNA cleavage specificity at known off-target sites. Furthermore, we developed and characterized SaRFNs as a complementary tool for RFN-based genome editing. Intriguingly, we also reveal that RFN orthologs can functionally hetero-dimerize to perform efficient genome editing, which further increases genome targetability and adds more flexibility to the system.

Materials and Methods

Cas9, FokI-dCas9, and gRNA Expression Plasmids

Csy4 and human codon-optimized SpCas9, SaCas9 SpRFN, or SaRFN variants were co-expressed from a CAG promoter separated by a self-cleaving T2A peptide. SpCas9 and SaCas9 were PCR amplified from pCas9-GFP (Addgene 44719) and pX601 (Addgene 61591), respectively, with target plasmid overlapping overhangs and cloned into HapI + NotI double-digested pSQT1601 (Addgene 53369) using Gibson cloning (New England Biolabs). dSaCas9 was generated by in vitro mutagenesis (Stratagene) of human codon-optimized SaCas9 in pX601 to introduce the inactivating D10A and N580A substitutions. Then dSaCas9 was cloned via Gibson cloning into pSQT1601 as described earlier. The dual-expression plasmid was generated via Gibson cloning by replacing the CAG promoter with a sequence encoding the U6 promoter driving expression of multiplexed gRNAs (amplified from pSQT1313; Addgene 53370) and a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter to drive the Csy4 and RFN expression. GFP was included via P2A self-cleaving peptide sequence at the C-terminal end of FokI-dCas9. All sequences can be found in Figure S10. Multiplexed gRNAs were expressed from the pSQT1313 vector and cloned as described elsewhere using a one-step T4 DNA ligation of annealed oligoduplexes.18 Spacer distances were measured as the number of base pairs between the gRNA complementarity regions (e.g., after the 20th nt of gRNA sequence for Sp gRNAs or after the 21st nt for all Sa gRNAs, starting with counting at the PAM-proximal position). The SpRNF with the (GGGGS)5 linker and the SaRFN plasmids will be made available via Addgene.

Cell Culture

The HEK293T-GFP cell line was generated by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homology-directed integration of a CAG-GFP/puromycin cassette into the AAVS1 locus using a previously validated and published gRNA and donor plasmid.53, 54 In brief, HEK293T cells (ATCC) were co-transfected with 1 μg each of AAV1-gRNA-T2 (Addgene 41818), AAV-CAGGS-EGFP (Addgene 22212), and pCas9_GFP (Addgene 44719) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). The next day, cells were treated with puromycin (2 μg/mL) for 1 week. Cells were then re-seeded into 96-well plates at clonal density, and single-cell-derived clonal lines were selected (1 μg/mL puromycin) and PCR genotyped (data not shown). A clone with a single heterozygous integration of the CAG-GFP cassette into the AAVS1 locus was identified and used for all GFP disruption assays.

HEK293T and HEK293T-GFP cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1× GlutaMAX (all Life Technologies), and 1 μg/mL puromycin (for HEK293T-GFP cells) at 37°C with 5% CO2 and passaged using Accutase (Millipore). HEK293T cells were chosen for their ease of handling, low maintenance costs, and because they have been frequently used in CRISPR/Cas9-related studies.8, 15, 17

H9 human embryonic stem cells were cultured on growth-factor-reduced Matrigel (Corning) in mTeSR1 (STEMCELL Technologies) at 37°C with 5% CO2 as previously described55, 56 and passaged using ReLeSR (STEMCELL Technologies). For the RFX6 disruption assay, Y-27632 (10 μM; Tocris) pre-treated H9 cells were dispersed with Accutase to generate single-cell suspensions. Nine hundred thousand cells were nucleofected with approximately 9 μg dual-expression plasmid using the Amaxa Human Stem Cell Kit 2 (Lonza) in the Amaxa nucleofector 2b system (Lonza). Two days post-nucleofection, H9 cells were FACS sorted for GFP using a BD Influx system and re-seeded at clonal density on Matrigel in mTeSR1 supplemented with Y-27632. Ten to 14 days later, single colonies were picked and expanded prior to gDNA isolation and Sanger sequencing as described elsewhere.57 The RFX6 sequence of clones that contained indels were PCR amplified and cloned into TOPO cloning vector (Life Technologies), and 10 plasmids per clone were sequenced to identify the genotype.

All cells used in this study were routinely checked for mycoplasma contamination using the PCR-based detection methods (Venor GeM Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit [Minerva Biolabs] or PCR Mycoplasma Test Kit I/C [Promokine]).

GFP Disruption Assay

HEK293T-GFP cells were seeded at a density of 97,000 cells per well in 24-well plates. The next day, 800 ng RFN plasmid and 200 ng multiplexed gRNA plasmid were co-transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 (1.2 μL P3000 + 1.7 μL; Life Technologies). Seventy-two hours post-transfection, cells were washed in PBS, detached using Accutase, and washed and resuspended in PBS on ice, before determining the amount of GFP-positive cells on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) system. GFP disruption assays were repeated three to seven times on different days (= biological replicates). Different RFN or Cas9 variants were assayed in parallel when co-expressed with a particular gRNA to allow direct comparison and paired t tests.

Quantification of RFN- or Cas9-Induced Mutation Rates by T7EI Assay

Genomic DNA was isolated 72 hr post-transfection using the Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCRs to amplify genomic loci were performed using Phusion High Fidelity PCR Master Mix with GC Buffer (Fermentas) or Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity Master Mix (New England Biolabs), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All oligos were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, and sequences can be found in Table S6. A total of 180–250 ng purified PCR amplicons was denatured, hybridized, and treated with T7 Endonuclease I according to manufacturer’s instructions (New England Biolabs). Mutation frequency was quantified using a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad) and ImageJ. Indel frequency was determined by applying the following formula:

Deep Sequencing and Indel Analysis

Short 207- to 296-bp PCR products were amplified from 600 ng genomic DNA using Phusion High Fidelity PCR Master Mix with GC Buffer or Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity Master Mix, according to the manufacturer’s instructions with 25 or 28 PCR cycles. PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR purification system (QIAGEN) and quantified with the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Life Technologies). Dual-indexed TruSeq Illumina deep-sequencing libraries were prepared from 25 ng of five pooled amplicons (5 ng each amplicon) using NEBNext Ultra DNA library prep kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs). A 150-bp paired-end sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq at the Next Generation Sequencing platform of the Genome Institute of Singapore. MiSeq paired-end reads were derived from two independent runs and mapped to the human genome reference GRCh37 using BWA MEM (version 0.7.10). Using fastq_filter algorithm in USEARCH package, reads were first trimmed from the 3′ end so that: (1) all remaining quality scores were greater than 10, (2) expected errors per base were less than 0.05 for each read, and (3) minimum read length was 80 nt. The parameters for fastq_filter are “-fastq_minlen 80 −fastq_maxee_rate 0.05 −fastq_trancqual 10.” The trimmed paired reads were then merged using fastq_mergepairs in USEARCH if read pairs were overlapped at 3′ end. The read quality of merged read was also corrected by “fastq_mergepairs.” Merged and unmerged reads were analyzed for insertion or deletion mutations that overlapped the intended target or candidate off-target site. Mutation analysis was conducted using Samtools and in-house perl script. Indels of ≥2 bp were considered RFN- or Cas9-induced mutations.

Statistics

The statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism using two-tailed, paired t test or unpaired t tests when appropriate. The p values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant (*p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001).

Author Contributions

L.W.S. and S.H. conceptualized the study, analyzed results, and wrote the manuscript. S.H. also designed plasmids and performed experiments. M.B.B., N.B.M.Z., and Z.Y.P. assisted in cloning plasmids. Y.A. and N.R.D. generated RFX6 knockout stem cell lines. Y.S. and Z.F. performed bioinformatics analyses.

Conflicts of Interest

Some aspects of this work are part of a patent application (no. 10201600814X).

Acknowledgments

We thank Matias Autio and Akshay Bhinge for helpful discussions and the sharing of Cas9 expression plasmids. We thank the Next Generation Sequencing platform at the Genome Institute of Singapore for excellent sequencing service, and we are grateful for funding received from the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) Singapore.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes ten figures and six tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2016.11.007.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Hsu P.D., Lander E.S., Zhang F. Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell. 2014;157:1262–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jinek M., Chylinski K., Fonfara I., Hauer M., Doudna J.A., Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fu Y., Sander J.D., Reyon D., Cascio V.M., Joung J.K. Improving CRISPR-Cas nuclease specificity using truncated guide RNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:279–284. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ran F.A., Cong L., Yan W.X., Scott D.A., Gootenberg J.S., Kriz A.J., Zetsche B., Shalem O., Wu X., Makarova K.S. In vivo genome editing using Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Nature. 2015;520:186–191. doi: 10.1038/nature14299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chylinski K., Makarova K.S., Charpentier E., Koonin E.V. Classification and evolution of type II CRISPR-Cas systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:6091–6105. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shmakov S., Abudayyeh O.O., Makarova K.S., Wolf Y.I., Gootenberg J.S., Semenova E., Minakhin L., Joung J., Konermann S., Severinov K. Discovery and functional characterization of diverse class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems. Mol. Cell. 2015;60:385–397. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esvelt K.M., Mali P., Braff J.L., Moosburner M., Yaung S.J., Church G.M. Orthogonal Cas9 proteins for RNA-guided gene regulation and editing. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:1116–1121. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duan J., Lu G., Xie Z., Lou M., Luo J., Guo L., Zhang Y. Genome-wide identification of CRISPR/Cas9 off-targets in human genome. Cell Res. 2014;24:1009–1012. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frock R.L., Hu J., Meyers R.M., Ho Y.J., Kii E., Alt F.W. Genome-wide detection of DNA double-stranded breaks induced by engineered nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:179–186. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu Y., Foden J.A., Khayter C., Maeder M.L., Reyon D., Joung J.K., Sander J.D. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:822–826. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim D., Bae S., Park J., Kim E., Kim S., Yu H.R., Hwang J., Kim J.I., Kim J.S. Digenome-seq: genome-wide profiling of CRISPR-Cas9 off-target effects in human cells. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:237–243. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3284. 231 p following 243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleinstiver B.P., Pattanayak V., Prew M.S., Tsai S.Q., Nguyen N.T., Zheng Z., Joung J.K. High-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature. 2016;529:490–495. doi: 10.1038/nature16526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuscu C., Arslan S., Singh R., Thorpe J., Adli M. Genome-wide analysis reveals characteristics of off-target sites bound by the Cas9 endonuclease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:677–683. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pattanayak V., Lin S., Guilinger J.P., Ma E., Doudna J.A., Liu D.R. High-throughput profiling of off-target DNA cleavage reveals RNA-programmed Cas9 nuclease specificity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ran F.A., Hsu P.D., Lin C.Y., Gootenberg J.S., Konermann S., Trevino A.E., Scott D.A., Inoue A., Matoba S., Zhang Y., Zhang F. Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell. 2013;154:1380–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slaymaker I.M., Gao L., Zetsche B., Scott D.A., Yan W.X., Zhang F. Rationally engineered Cas9 nucleases with improved specificity. Science. 2016;351:84–88. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guilinger J.P., Thompson D.B., Liu D.R. Fusion of catalytically inactive Cas9 to FokI nuclease improves the specificity of genome modification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:577–582. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai S.Q., Wyvekens N., Khayter C., Foden J.A., Thapar V., Reyon D., Goodwin M.J., Aryee M.J., Joung J.K. Dimeric CRISPR RNA-guided FokI nucleases for highly specific genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:569–576. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wyvekens N., Topkar V.V., Khayter C., Joung J.K., Tsai S.Q. Dimeric CRISPR RNA-guided FokI-dCas9 nucleases directed by truncated gRNAs for highly specific genome editing. Hum. Gene Ther. 2015;26:425–431. doi: 10.1089/hum.2015.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen X., Zaro J.L., Shen W.C. Fusion protein linkers: property, design and functionality. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013;65:1357–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.George R.A., Heringa J. An analysis of protein domain linkers: their classification and role in protein folding. Protein Eng. 2002;15:871–879. doi: 10.1093/protein/15.11.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reyon D., Tsai S.Q., Khayter C., Foden J.A., Sander J.D., Joung J.K. FLASH assembly of TALENs for high-throughput genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:460–465. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilbert L.A., Horlbeck M.A., Adamson B., Villalta J.E., Chen Y., Whitehead E.H., Guimaraes C., Panning B., Ploegh H.L., Bassik M.C. Genome-scale CRISPR-mediated control of gene repression and activation. Cell. 2014;159:647–661. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilbert L.A., Larson M.H., Morsut L., Liu Z., Brar G.A., Torres S.E., Stern-Ginossar N., Brandman O., Whitehead E.H., Doudna J.A. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell. 2013;154:442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajagopal N., Srinivasan S., Kooshesh K., Guo Y., Edwards M.D., Banerjee B., Syed T., Emons B.J., Gifford D.K., Sherwood R.I. High-throughput mapping of regulatory DNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:167–174. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korkmaz G., Lopes R., Ugalde A.P., Nevedomskaya E., Han R., Myacheva K., Zwart W., Elkon R., Agami R. Functional genetic screens for enhancer elements in the human genome using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:192–198. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cruz L., Schnur R.E., Post E.M., Bodagala H., Ahmed R., Smith C., Lulis L.B., Stahl G.E., Kushnir A. Clinical and genetic complexity of Mitchell-Riley/Martinez-Frias syndrome. J. Perinatol. 2014;34:948–950. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bramswig N.C., Kaestner K.H. Transcriptional regulation of α-cell differentiation. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2011;13(Suppl 1):13–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kleinstiver B.P., Prew M.S., Tsai S.Q., Nguyen N.T., Topkar V.V., Zheng Z., Joung J.K. Broadening the targeting range of Staphylococcus aureus CRISPR-Cas9 by modifying PAM recognition. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:1293–1298. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishimasu H., Cong L., Yan W.X., Ran F.A., Zetsche B., Li Y., Kurabayashi A., Ishitani R., Zhang F., Nureki O. Crystal structure of Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Cell. 2015;162:1113–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lisowski L., Tay S.S., Alexander I.E. Adeno-associated virus serotypes for gene therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2015;24:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao Y., Zhao Y. Self-processing of ribozyme-flanked RNAs into guide RNAs in vitro and in vivo for CRISPR-mediated genome editing. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2014;56:343–349. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie K., Minkenberg B., Yang Y. Boosting CRISPR/Cas9 multiplex editing capability with the endogenous tRNA-processing system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:3570–3575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420294112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dominguez A.A., Lim W.A., Qi L.S. Beyond editing: repurposing CRISPR-Cas9 for precision genome regulation and interrogation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:5–15. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esvelt K.M., Smidler A.L., Catteruccia F., Church G.M. Concerning RNA-guided gene drives for the alteration of wild populations. eLife. 2014 doi: 10.7554/eLife.03401. Published online July 17, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doench J.G., Fusi N., Sullender M., Hegde M., Vaimberg E.W., Donovan K.F., Smith I., Tothova Z., Wilen C., Orchard R. Optimized sgRNA design to maximize activity and minimize off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:184–191. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cho S.W., Kim S., Kim Y., Kweon J., Kim H.S., Bae S., Kim J.S. Analysis of off-target effects of CRISPR/Cas-derived RNA-guided endonucleases and nickases. Genome Res. 2014;24:132–141. doi: 10.1101/gr.162339.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright A.V., Sternberg S.H., Taylor D.W., Staahl B.T., Bardales J.A., Kornfeld J.E., Doudna J.A. Rational design of a split-Cas9 enzyme complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:2984–2989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501698112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zetsche B., Volz S.E., Zhang F. A split-Cas9 architecture for inducible genome editing and transcription modulation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:139–142. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zuris J.A., Thompson D.B., Shu Y., Guilinger J.P., Bessen J.L., Hu J.H., Maeder M.L., Joung J.K., Chen Z.Y., Liu D.R. Cationic lipid-mediated delivery of proteins enables efficient protein-based genome editing in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:73–80. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramakrishna S., Kwaku Dad A.B., Beloor J., Gopalappa R., Lee S.K., Kim H. Gene disruption by cell-penetrating peptide-mediated delivery of Cas9 protein and guide RNA. Genome Res. 2014;24:1020–1027. doi: 10.1101/gr.171264.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crosetto N., Mitra A., Silva M.J., Bienko M., Dojer N., Wang Q., Karaca E., Chiarle R., Skrzypczak M., Ginalski K. Nucleotide-resolution DNA double-strand break mapping by next-generation sequencing. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:361–365. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsai S.Q., Zheng Z., Nguyen N.T., Liebers M., Topkar V.V., Thapar V., Wyvekens N., Khayter C., Iafrate A.J., Le L.P. GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:187–197. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gabriel R., Lombardo A., Arens A., Miller J.C., Genovese P., Kaeppel C., Nowrouzi A., Bartholomae C.C., Wang J., Friedman G. An unbiased genome-wide analysis of zinc-finger nuclease specificity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:816–823. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang X., Wang Y., Wu X., Wang J., Wang Y., Qiu Z., Chang T., Huang H., Lin R.J., Yee J.K. Unbiased detection of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas9 and TALENs using integrase-defective lentiviral vectors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:175–178. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stella S., Montoya G. The genome editing revolution: A CRISPR-Cas TALE off-target story. BioEssays. 2016;38(Suppl 1):S4–S13. doi: 10.1002/bies.201670903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richardson C.D., Ray G.J., DeWitt M.A., Curie G.L., Corn J.E. Enhancing homology-directed genome editing by catalytically active and inactive CRISPR-Cas9 using asymmetric donor DNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:339–344. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.González F., Zhu Z., Shi Z.D., Lelli K., Verma N., Li Q.V., Huangfu D. An iCRISPR platform for rapid, multiplexable, and inducible genome editing in human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kearns N.A., Pham H., Tabak B., Genga R.M., Silverstein N.J., Garber M., Maehr R. Functional annotation of native enhancers with a Cas9-histone demethylase fusion. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:401–403. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thakore P.I., D’Ippolito A.M., Song L., Safi A., Shivakumar N.K., Kabadi A.M., Reddy T.E., Crawford G.E., Gersbach C.A. Highly specific epigenome editing by CRISPR-Cas9 repressors for silencing of distal regulatory elements. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:1143–1149. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maeder M.L., Linder S.J., Cascio V.M., Fu Y., Ho Q.H., Joung J.K. CRISPR RNA-guided activation of endogenous human genes. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:977–979. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kleinstiver B.P., Prew M.S., Tsai S.Q., Topkar V.V., Nguyen N.T., Zheng Z., Gonzales A.P., Li Z., Peterson R.T., Yeh J.R. Engineered CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with altered PAM specificities. Nature. 2015;523:481–485. doi: 10.1038/nature14592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mali P., Yang L., Esvelt K.M., Aach J., Guell M., DiCarlo J.E., Norville J.E., Church G.M. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hockemeyer D., Soldner F., Beard C., Gao Q., Mitalipova M., DeKelver R.C., Katibah G.E., Amora R., Boydston E.A., Zeitler B. Efficient targeting of expressed and silent genes in human ESCs and iPSCs using zinc-finger nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27:851–857. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eberhardt E., Havlicek S., Schmidt D., Link A.S., Neacsu C., Kohl Z., Hampl M., Kist A.M., Klinger A., Nau C. Pattern of functional TTX-resistant sodium channels reveals a developmental stage of human iPSC- and ESC-derived nociceptors. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;5:305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Havlicek S., Kohl Z., Mishra H.K., Prots I., Eberhardt E., Denguir N., Wend H., Plötz S., Boyer L., Marchetto M.C. Gene dosage-dependent rescue of HSP neurite defects in SPG4 patients’ neurons. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:2527–2541. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peters D.T., Cowan C.A., Musunuru K. StemBook; 2008. Genome editing in human pluripotent stem cells. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.