Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is leading cardiac arrhythmia with important clinical implications. Its diagnosis is usually made on the basis on 12-lead ECG or 24-hour Holter monitoring. More and more clinical evidence supports diagnostic use of cardiac event recorders and cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIED). Treatment options in patients with atrial fibrillation are extensive and are based on chosen rhythm and/or rate control strategy. The use and selected contraindications to AF related pharmacotherapy, including anticoagulants are shown. Nonpharmacological treatments, comorbidities and risk factors control remain mainstay in the treatment of patients with AF. Electrical cardioversion consists important choice in rhythm control strategy. Much progress has been made in the field of catheter ablation and cardiac surgery methods. Left atrial appendage occlusion/closure may be beneficial in patients with AF. CIED are used with clinical benefits in both, rhythm and rate control. Pacemakers, implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization therapy devices with different pacing modes have guaranteed place in the treatment of patients with AF. On the other hand, the concepts of permanent leadless cardiac pacing, atrial dyssynchrony syndrome treatment and His-bundle or para-Hisian pacing have been proposed. This review summarizes and discusses current and novel treatment options in patients with atrial fibrillation.

Keywords: Atrial Fibrillation, Treatment, Ablation, Pacemaker, ICD, CRT

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most prevalent cardiac arrhythmia with important clinical implications.[1] In 2010, AF affected 33.5 million of individuals globally and was described as ‘growing epidemic’.[1] AF decreases health related quality of life[2] and substantially contributes to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality especially in women.[3] Variety of possible causative risk factors and diseases, comorbidities, as well as possible complications resulting from AF require comprehensive assessment and management of patients with atrial fibrillation (Fig 1). It refers also to screening of general population and especially subjects at risk of atrial fibrillation.[4,5] Screening of patients ranges from simple pulse assessment, through various forms of electrocardiography monitoring (including symptom event monitors and looping memory monitors), to active search of atrial high rate episodes (AHRE) in patients with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIED).[6] Especially after cryptogenic stroke insertable cardiac monitors represent reasonable AF diagnostic approach.[7] CIED as well as AF ablation techniques are more and more accessible in current clinical practice and possess great potential in the treatment of patients with AF. Their application will be the focus of current review.

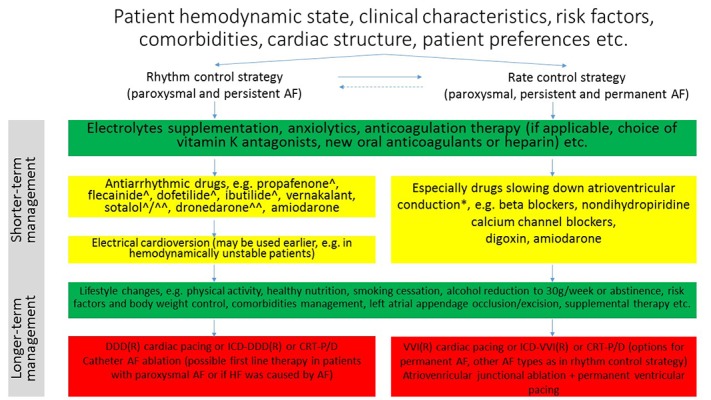

Figure 1. Overview of clinical management of patients with atrial fibrillation.

AF, atrial fibrillation; HF, heart failure; DDD, dual chamber pacemaker; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; CRT-P/D, cardiac resynchronization therapy-pacemaker/defibrillator. ^ not recommended in left ventricular hypertrophy >15mm or ≥14mm (ibutilide) ^^ not for cardioversion. * some of these drugs should not be used in decompensated heart failure and/or in patients with pre-excitation

Overview of Clinical Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation

In non-emergency clinical situations before choice of clinical strategy patient clinical characteristics, risk factors, comorbidities, cardiac structure and patient preferences should be assessed and each patient should be managed individually (Fig. 1). It should be accompanied with knowledge of specific contraindications, proarrhythmic effects and noncardiovascular toxicities of antiarrhythmic drugs.[8] Especially reversible AF causes should be targeted. In the assessment of the risk of AF progression HATCH (Hypertension, Age ≥75 years, previous Transient ischemic attack/stroke [2 points], Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and Heart failure [2 points]) scale may be utilized.[9,10]

Adequate rhythm and ventricular rate control prevent hemodynamic disturbances. Based on AF symptoms frequency „pill-in-the-pocket” (propafenone or flecainide added to beta blocker or nondihydropyridine calcium channel antagonist) may be the choice of treatment especially in the early phase of AF, in patients without advanced structural heart disease, once revealed to be safe in a monitored setting.[11,12] Patients with severe heart failure should be treated with amiodarone. Using amiodarone the pharmacological cardioversion to sinus rhythm is achieved later than in the case of class Ic drugs.[13] Electrical cardioversion, when compared to pharmacological cardioversion is more effective, particularly in persistent AF.[13] On the other hand AF symptoms duration ≥ 48 hours (or of unknown duration), patients requiring anticoagulation therapy, remain contraindications (not in hemodynamically unstable patients) to both pharmacological and electrical cardioversion if anticoagulation was not introduced at least 3 weeks earlier or left atrial thrombus was not excluded.[12,14] In patients assessment echocardiography has an important role which it not only helps to guide management strategy, but also the choice of drugs.

The rate control strategy focuses on slowing down atrioventricular conduction. The drugs used in this strategy include beta-blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, digoxin and especially in resistant to treatment subjects amiodarone. The resting heart rate target of <80 beats per minute (bpm) or <110 bpm during moderate exercise (or resting if lenient rate-control strategy is applicable) should be achieved.[12,15] However, we should take into account that ventricular rates <70 bpm may be associated with a worse outcome and current European Society of Cardiology guidelines for patients with heart failure (HF) and AF recommend resting heart rate of 60-100 bpm as optimal target value.[16]

Thromboembolic and bleeding complications prevention is one of the most important goals in treatment of patients with AF. Scales important in their risk assessment include CHA2DS2-VASc (Congestive heart failure/ left ventricular dysfunction, Hypertension, Age ≥75 years [2 points], Diabetes mellitus, Stroke/ transient ischemic attack/thromboembolism [2 points], Vascular disease (prior myocardial infarction, aortic plaque or peripheral artery disease), Age 65-74 years, Sex category [female gender])[17] and HAS-BLED (uncontrolled Hypertension, Abnormal renal/liver function [1 or 2 points], Stroke previous history, Bleeding history or predisposition [anemia], Labile international normalized ratio [INR], Elderly [> 65 years], Drugs/alcohol use [1 or 2 points])[18] scores. These scales calculate risk of stroke/peripheral embolism/pulmonary embolism or risk of major bleeding, respectively. Moreover, inclusion of persistent form of AF and renal impairment, beside CHA2DS2-VASc score, may be considered and may lead to achievement of greatest area under the curve.[19,20] Based on risk stratification of thromboembolic complications anticoagulation therapy use must be considered. One should take into account, that new, promising players appear and become more and more common on the stage of anticoagulation therapy and currently in eligible patients non-vitamin-K oral anticoagulants are recommended as the first-line anticoagulants.[21,22,80] Bleeding risk management should especially focus on modifiable bleeding risk factors correction and if high bleeding risk is present it should generally not be a contraindication to anticoagulation.[80] On the other hand in AF patients with clear contraindications for long-term oral anticoagulation therapy left atrial appendage (LAA) occlusion may be considered for stroke prevention.[14,80] LAA occlusion may be performed using endocardial percutaneous intracardiac occluder (WATCHMANTM, Amplatzer Cardiac Plug) and epicardial left atrial appendage ligation via pericardiac sack (LARIAT, AtriClip®).[23,24] According to recently published data, LAA occlusion may eliminate significantly the risk of thromboembolic complications.[24,25] LAA surgical occlusion or exclusion may be considered in AF patients undergoing cardiac surgery as well as thoracoscopic AF surgery.[14,24,80] Extracardiac LAA ligation may be performed via thoracoscopy or percutaneously.

In both AF treatment strategies upstream therapies should be considered. Intensive risk factors management, including hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, diabetes, smoking and obstructive sleep apnoea may increase clinical success rates.[26] Moreover exercise and alcohol abstinence (or reduction to 30g per week) should also be taken into consideration.[26] As mean body mass index (BMI) among patients with AF is elevated,[27,28] importance of weight management needs to be emphasized. In a study by abed and colleagues, in patients with obesity and symptomatic AF, with a median follow up of 15 months duration it was found that weight management with intensive management of cardiometabolic risk factors (intervention group) was superior to intensive management of cardiometabolic risk factors and general lifestyle advice in achieving weight reduction and reduction of AF symptom burden and severity scores, number of episodes and cumulative duration.[29] Interestingly in both studied groups reduction of interventricular septal thickness and left atrial area were observed and were more pronounced in the intervention group.[29] Long-Term Effect of Goal directed weight management on Atrial Fibrillation Cohort: A 5 Year follow-up (LEGACY) study revealed that in patients with AF and BMI ≥27kg/m2 sustained (particularly with evasion of weight fluctuation), long-term weight loss associates (in a dose dependent manner) with AF burden reduction and maintenance of sinus rhythm.[30] Furthermore, these changes associate with beneficial alterations in risk factors and cardiac remodeling.[30]

Ablation in The Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation

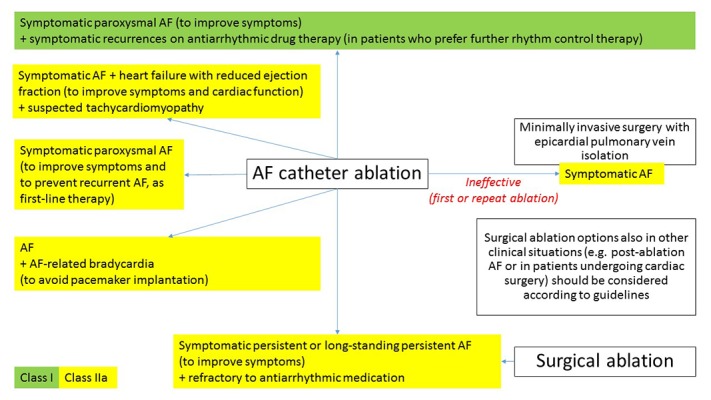

Atrial fibrillation ablation eliminates the arrhythmogenic triggers, substrate and/or improper impulses propagation. Promising effects of new ablation devices influence increase in number of candidates for AF ablation and lead to decrease in complications rate. Taking into account patients preferences as well as outcomes associated with catheter AF ablation, it should be considered in selected patients with symptomatic paroxysmal AF (as first-line therapy) and in cases of ineffective pharmacological treatment of persistent AF (Fig. 2).[14,80] It is generally indicated in symptomatic recurrences of paroxysmal AF during antiarrhythmic drug therapy. Moreover in management of AF patients AF Heart Teams have been proposed.[12,80] Tachycardiomyopathy is another clinical situation in which AF ablation may be performed before use of antiarrhythmic pharmacotherapy.[14] This recommendation seems to be in line with results of recent clinical trial, which has shown, that catheter ablation of persistent AF in patients with HF was found to be superior to amiodarone in achieving no AF recurrence at long-term follow-up and reduction in unplanned hospitalizations and mortality.[31] Catheter or surgical ablation of AF should be considered in symptomatic patients with persistent AF or long-standing, persistent AF refractory to antiarrhythmic medication (Fig. 2).[80] Healthier, younger individuals may benefit more from ablation than elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. However, benefits of AF ablation in patients ≥ 75 years old were shown to be effective in reducing mortality and stroke risk.[32] AF arrhythmogenic substrate location is often poorly defined so its targeting has probalilistic nature. The most common AF origins are, atrial muscle sleeves extending to pulmonary veins (ca. 80%), left atrial posterior wall, superior caval vein, oblique vein/ligament of Marshal, terminal crest, coronary sinus and interatrial septum.[33] AF ablation may be performed from the endocardial side using catheters introduced via femoral vein and transseptal puncture. Alternatively, epicardial ablation by open heart surgery (often performed in conjunction with other cardiac surgery) or via a thoracoscopic or mediastinal approach. Moreover the hybrid procedures are also performed. The most common techniques in AF ablation is pulmonary veins isolation (PVI) without or with lines and/or complex fractionated atrial electrogram (CFAE) ablation.[34] Regarding to freedom from total tachyarrhythmia during long-term follow-up, it was shown, that wide antral circumferential ablation (WACA) approach (ablation ≥1.5 cm away from PV ostium) in PVI is more effective than ostial PVI.[35] Some of the most frequent lines in catheter AF ablation are the “roof line”, the “mitral isthmus line” and anterior linear lesion.[36,37] In patients with history of cavotricuspid isthmus dependent atrial flutter or if it was induced during EP testing additional linear lesion at the cavotricuspid isthmus is also placed.[37]

Figure 2. Overview of atrial fibrillation ablation indications.

AF, atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation ablation may be performed using radiofrequency energy, cryothermy, laser, ultrasound or microwave energy, some of them remain still at the initial stage.[38] Recent clinical trial (The FIRE AND ICE Trial) revealed that cryoballoon ablation was noninferior to radiofrequency ablation (the most common method, with the use of electroanatomical mapping system) in patients with drug-refractory paroxysmal atrial fibrillation.[39] The recommendations regarding atrial fibrillation ablation by PVI technique point that electrical PV isolation should be the goal and entrance block into PV should be demonstrated. Moreover reconduction assessment 20 minutes following initial procedure should be considered.[37]

Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Devices in Management of Atrial Fibrillation

Many clinically interesting cardiovascular implantable electronic devices functions were shown to have significant impact on the course of AF and clinical management of patients with AF. CIED play important role both in the diagnosis and treatment of atrial fibrillation. Incidence of pacemaker-detected AF may reach 50% and its burden is associated with increased stroke risk.[40,41] However, it was found that patients with subclinical pacemaker-detected AF are significantly less frequently treated by anticoagulants than patients with clinical AF.[40] On the other hand remote control of CIED enables early detection of AF and/or optimization of treatment.[42]

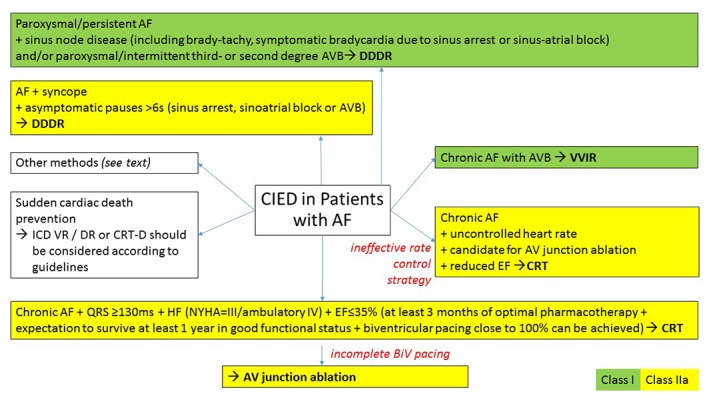

Cardiac implantable electronic devices in treatment of AF are generally reserved for clinical situations in which lifestyle changes and pharmacological and/or ablation treatments are ineffective. Choice of pacing mode in patients with AF is very important. In patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF and concomitant sinus node disease and/or atrioventricular (AV) conduction disturbances atrioventricular rate – responsive pacing (DDDR) is indicated (rhythm and rate control). Ventricular rate responsive cardiac pacing (VVIR) is used in patients with advanced AV conduction disturbances in the course of permanent AF (heart rate control), Fig. 3.[12,14] Importantly permanent leadless cardiac pacing may possess valuable treatment option especially in this group of patients.[43]

Figure 3. Overview of current options and/or guidelines recommendations for cardiovascular implantable electronic devices use in patients with AF. Based on,[57,58] other references are cited throughout the text.

AV, atrioventricular; AVB, atrioventricular block; CIED, cardiovascular implantable electronic devices; EF, ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; BiV, biventricular; other abbreviations as in Fig. 1

Atrial fibrillation is frequent in patients with heart failure (HF).[44,45] There are two groups of indications for CIED implantation in patients with AF and HF. The first group includes patients with AF and HF, who are often characterized by prolonged ventricular depolarization (especially QRS ≥ 130ms) and decreased left ventricular ejection fraction (EF≤35%)[81] and the second, in which left ventricular dysfunction results from long standing fast heart rate. Patients in both clinical categories may benefit from improved heart rhythm and/or heart rate control. MUltisite STimulation In Cardiomyopathies (MUSTIC) study evaluated the effects of biventricular pacing in HF patients in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III and intraventricular conduction delay. It revealed clinical benefits according to improved 6-min walked distance, quality of life and NYHA class, also in patients with AF.[46] In the Ablate and Pace in Atrial Fibrillation (APAF) trial ‘Ablate and Pace’ therapy for severely symptomatic chronic AF was tested.[47] In this study cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) was superior to apical right ventricular pacing in reducing clinical manifestations of HF in patients undergoing AV junction ablation.[47] On the other hand subgroup analysis of the Resynchronization–Defibrillation for Ambulatory Heart Failure Trial (RAFT) revealed, that in patients with permanent AF or atrial flutter, HF (NYHA class II-III), a LVEF ≤30% and an intrinsic QRS ≥120ms or a paced QRS ≥200ms, who received an CRT-D device did not differ from those who received implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) alone, when death or HF hospitalization were taken into account (composite primary outcome).[48] Therefore indications to implant CRT in patients with permanent AF and without significant bradyarrhythmias is discussed, especially because large registry data have shown, that atrial tachycardia/AF was the most prevalent reason for CRT pacing loss.[49]

However, systematic review revealed that patients with AF undergoing CRT for symptomatic heart failure and left ventricular dyssynchrony, after AV nodal ablation compared with medical therapy aimed at rate control, had significantly reduced all-cause and cardiovascular mortality as well as had improved NYHA class.[50] On the other hand, we have to keep in mind, that patients after AV nodal ablation are pacing device dependent.

Patients with AF and increased sudden cardiac death (SCD) risk may benefit from implantable cardioverter-defibrillators as SCD preventive therapy. However, after ICD implantation for primary or secondary prevention, during median follow-up of 3 years, about 21% of patients suffer from inappropriate ICD shocks and 60% of them result from AF.[51] Moreover multiple (≥2) ICD shocks due to AF are associated with worse prognosis, while single shock resulting from AF or shocks due to lead failure are not.[51] It is crucial in ICD programming to know discrimination algorithms, including interval stability and atrioventricular association discriminator in dual-chamber ICD differentiating AF from fast ventricular rhythms.[52]

Moreover, in selected patients with AF, especially with concomitant heart failure, requiring permanent cardiac pacing, His-bundle or para-Hisian pacing may possess a therapeutic option.[53-56] However, this mode of pacing limitations include intraventricular conduction disturbances.

Overview of current options and/or guidelines recommendations for CIED implantation in patients with AF are shown on Fig. 3.[57,58]

Permanent Cardiac Pacing and Reduction of AF

Influence of pacing mode on AF was tested in Canadian Trial Of Physiologic Pacing (CTOPP).[59] Results of CTOPP have shown, that patients who underwent physiologic (atrial based) pacing (AAI or DDD) were less likely to develop chronic AF, than patients who underwent ventricular-based pacing.[59] Similar results were also found in our study, in which we have found that DDD pacing mode was associated with lower rate of AF de novo than VVI pacing mode.[60] Surprisingly, subgroup analysis of CTOPP revealed, that in patients with myocardial infarction/coronary artery disease or abnormal left ventricular function, there was no benefit regarding chronic AF development resulting from physiologic pacing.[59] The current look, takes into account the detrimental effect of high right ventricular pacing percentage and enables us to assess the results of the CTOPP study differently.[61,62]

In patients after total AV junction ablation, without antiarrhythmic therapy, DDDR cardiac pacing, compared with VDD pacing (PA3 Trial) did not prevent paroxysmal AF.[63] This data also suggest, that ventricular pacing (also in synchronous mode) promotes AF.[64] Therefore, DDD(R) pacemakers with programmed algorithms promoting spontaneous AV conduction should be prefered in most pacemaker patients without permanent AF and significant AV conduction abnormalities.[65]

Cardiac resynchronization therapy may influence atrial fibrillation and possess antiarrhythmic effects.[66-68] Gasparini and colleagues, found that end-diastolic diameter ≤65 mm, left atrium ≤50 mm, post-CRT QRS ≤150 ms and atrioventricular junction ablation appear to be predictive of spontaneous sinus rhythm resumption in heart failure patients with permanent AF after CRT introduction.[68] However, in the CArdiac REsynchronisation in Heart Failure (CARE-HF) trial, CRT did not reduce the incidence of AF.[69] It should be emphasized that in the Management of Atrial fibrillation Suppression in AF-HF COmorbidity Therapy (MASCOT) trial it was revealed that the atrial overdrive pacing did not lower the 1-year incidence of AF in a group of CRT recipients.[70]

Interestingly, the interaction between electrical impulses in the right and left atrium may be important to sustain AF.[71] Electrical activation between atria occurs by preferential conduction pathways, such as Bachmann’s bundle, fossa ovalis rim and coronary sinus.[71] Atrial conduction disturbances due to primary disease, AF recurrences and/or AF ablation may lead to atrial dyssynchrony and be a risk factor for atrial fibrillation.[72,73] It may therefore be targeted by atrial resynchronization through multisite atrial pacing (including Bachmann’s bundle area and coronary sinus ostium pacing), atrial septal pacing, coronary sinus or biatrial pacing.[72,74-79] However, concept of atrial dyssynchrony syndrome treatment needs more research evidence before it could be widely used in clinical practice.[72]

Conclusions

Treatment options in atrial fibrillation are extensive and are based on chosen rhythm and/or rate control strategy. Indications for anticoagulation therapy must be considered in all AF patients. Nonpharmacological treatments, comorbidities and risk factors control remain mainstay in the treatment of patients with AF. Electrical cardioversion consists important choice in rhythm control strategy. Much progress has been made in the field of catheter ablation and cardiac surgery methods. Left atrial appendage occlusion/closure may be beneficial in patients with AF. CIED are used with clinical benefits in both, rhythm and rate control. Pacemakers, implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization therapy devices with different pacing modes have guaranteed place in the treatment of patients with AF.

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Chugh Sumeet S, Havmoeller Rasmus, Narayanan Kumar, Singh David, Rienstra Michiel, Benjamin Emelia J, Gillum Richard F, Kim Young-Hoon, McAnulty John H, Zheng Zhi-Jie, Forouzanfar Mohammad H, Naghavi Mohsen, Mensah George A, Ezzati Majid, Murray Christopher J L. Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: a Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Circulation. 2014 Feb 25;129 (8):837–47. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kristensen Marie S, Zwisler Ann-Dorthe, Berg Selina K, Zangger Graziella, Grønset Charlotte N, Risom Signe S, Pedersen Susanne S, Oldridge Neil, Thygesen Lau C. Validating the HeartQoL questionnaire in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016 Sep;23 (14):1496–503. doi: 10.1177/2047487316638485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emdin Connor A, Wong Christopher X, Hsiao Allan J, Altman Douglas G, Peters Sanne Ae, Woodward Mark, Odutayo Ayodele A. Atrial fibrillation as risk factor for cardiovascular disease and death in women compared with men: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2016 Jan 19;532 () doi: 10.1136/bmj.h7013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dewland Thomas A, Vittinghoff Eric, Mandyam Mala C, Heckbert Susan R, Siscovick David S, Stein Phyllis K, Psaty Bruce M, Sotoodehnia Nona, Gottdiener John S, Marcus Gregory M. Atrial ectopy as a predictor of incident atrial fibrillation: a cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013 Dec 03;159 (11):721–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-11-201312030-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein Phyllis K. Increased randomness of heart rate could explain increased heart rate variability preceding onset of atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004 Aug 04;44 (3):668–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benezet-Mazuecos Juan, Rubio José Manuel, Farré Jerónimo. Atrial high rate episodes in patients with dual-chamber cardiac implantable electronic devices: unmasking silent atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2014 Aug;37 (8):1080–6. doi: 10.1111/pace.12428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanna Tommaso, Diener Hans-Christoph, Passman Rod S, Di Lazzaro Vincenzo, Bernstein Richard A, Morillo Carlos A, Rymer Marilyn Mollman, Thijs Vincent, Rogers Tyson, Beckers Frank, Lindborg Kate, Brachmann Johannes. Cryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014 Jun 26;370 (26):2478–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimetbaum Peter. Antiarrhythmic drug therapy for atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2012 Jan 17;125 (2):381–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.019927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Vos Cees B, Pisters Ron, Nieuwlaat Robby, Prins Martin H, Tieleman Robert G, Coelen Robert-Jan S, van den Heijkant Antonius C, Allessie Maurits A, Crijns Harry J G M. Progression from paroxysmal to persistent atrial fibrillation clinical correlates and prognosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010 Feb 23;55 (8):725–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett Tyler W, Self Wesley H, Wasserman Brian S, McNaughton Candace D, Darbar Dawood. Evaluating the HATCH score for predicting progression to sustained atrial fibrillation in ED patients with new atrial fibrillation. Am J Emerg Med. 2013 May;31 (5):792–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alboni Paolo, Botto Giovanni L, Baldi Nicola, Luzi Mario, Russo Vitantonio, Gianfranchi Lorella, Marchi Paola, Calzolari Massimo, Solano Alberto, Baroffio Raffaele, Gaggioli Germano. Outpatient treatment of recent-onset atrial fibrillation with the "pill-in-the-pocket" approach. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004 Dec 02;351 (23):2384–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.January Craig T, Wann L Samuel, Alpert Joseph S, Calkins Hugh, Cigarroa Joaquin E, Cleveland Joseph C, Conti Jamie B, Ellinor Patrick T, Ezekowitz Michael D, Field Michael E, Murray Katherine T, Sacco Ralph L, Stevenson William G, Tchou Patrick J, Tracy Cynthia M, Yancy Clyde W. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014 Dec 02;130 (23):e199–267. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crijns Harry J G M, Weijs Bob, Fairley Anna-Meagan, Lewalter Thorsten, Maggioni Aldo P, Martín Alfonso, Ponikowski Piotr, Rosenqvist Mårten, Sanders Prashanthan, Scanavacca Mauricio, Bash Lori D, Chazelle François, Bernhardt Alexandra, Gitt Anselm K, Lip Gregory Y H, Le Heuzey Jean-Yves. Contemporary real life cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: Results from the multinational RHYTHM-AF study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014 Apr 01;172 (3):588–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.01.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camm A John, Lip Gregory Y H, De Caterina Raffaele, Savelieva Irene, Atar Dan, Hohnloser Stefan H, Hindricks Gerhard, Kirchhof Paulus. 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur. Heart J. 2012 Nov;33 (21):2719–47. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Camm A John, Kirchhof Paulus, Lip Gregory Y H, Schotten Ulrich, Savelieva Irene, Ernst Sabine, Van Gelder Isabelle C, Al-Attar Nawwar, Hindricks Gerhard, Prendergast Bernard, Heidbuchel Hein, Alfieri Ottavio, Angelini Annalisa, Atar Dan, Colonna Paolo, De Caterina Raffaele, De Sutter Johan, Goette Andreas, Gorenek Bulent, Heldal Magnus, Hohloser Stefan H, Kolh Philippe, Le Heuzey Jean-Yves, Ponikowski Piotr, Rutten Frans H. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2010 Oct;31 (19):2369–429. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ponikowski Piotr, Voors Adriaan A, Anker Stefan D, Bueno Héctor, Cleland John G F, Coats Andrew J S, Falk Volkmar, González-Juanatey José Ramón, Harjola Veli-Pekka, Jankowska Ewa A, Jessup Mariell, Linde Cecilia, Nihoyannopoulos Petros, Parissis John T, Pieske Burkert, Riley Jillian P, Rosano Giuseppe M C, Ruilope Luis M, Ruschitzka Frank, Rutten Frans H, van der Meer Peter. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2016 Jul 14;37 (27):2129–200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lip Gregory Y H, Nieuwlaat Robby, Pisters Ron, Lane Deirdre A, Crijns Harry J G M. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010 Feb;137 (2):263–72. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pisters Ron, Lane Deirdre A, Nieuwlaat Robby, de Vos Cees B, Crijns Harry J G M, Lip Gregory Y H. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest. 2010 Nov;138 (5):1093–100. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kosior Dariusz A. Risk stratification schemes for stroke in atrial fibrillation: the predictive factors still undefined. Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn. 2015;125 (12):889–90. doi: 10.20452/pamw.3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinberg Benjamin A, Hellkamp Anne S, Lokhnygina Yuliya, Patel Manesh R, Breithardt Günter, Hankey Graeme J, Becker Richard C, Singer Daniel E, Halperin Jonathan L, Hacke Werner, Nessel Christopher C, Berkowitz Scott D, Mahaffey Kenneth W, Fox Keith A A, Califf Robert M, Piccini Jonathan P. Higher risk of death and stroke in patients with persistent vs. paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: results from the ROCKET-AF Trial. Eur. Heart J. 2015 Feb 01;36 (5):288–96. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Undas Anetta, Pasierski Tomasz, Windyga Jerzy, Crowther Mark. Practical aspects of new oral anticoagulant use in atrial fibrillation. Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn. 2014;124 (3):124–35. doi: 10.20452/pamw.2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Caterina Raffaele, Husted Steen, Wallentin Lars, Andreotti Felicita, Arnesen Harald, Bachmann Fedor, Baigent Colin, Huber Kurt, Jespersen Jørgen, Kristensen Steen Dalby, Lip Gregory Y H, Morais João, Rasmussen Lars Hvilsted, Siegbahn Agneta, Verheugt Freek W A, Weitz Jeffrey I. New oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation and acute coronary syndromes: ESC Working Group on Thrombosis-Task Force on Anticoagulants in Heart Disease position paper. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012 Apr 17;59 (16):1413–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartus Krzysztof, Han Frederick T, Bednarek Jacek, Myc Jacek, Kapelak Boguslaw, Sadowski Jerzy, Lelakowski Jacek, Bartus Stanislaw, Yakubov Steven J, Lee Randall J. Percutaneous left atrial appendage suture ligation using the LARIAT device in patients with atrial fibrillation: initial clinical experience. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013 Jul 09;62 (2):108–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramlawi Basel, Abu Saleh Walid K, Edgerton James. The Left Atrial Appendage: Target for Stroke Reduction in Atrial Fibrillation. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2015 Aug 26;11 (2):100–3. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-11-2-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holmes David R, Reddy Vivek Y, Turi Zoltan G, Doshi Shephal K, Sievert Horst, Buchbinder Maurice, Mullin Christopher M, Sick Peter. Percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage versus warfarin therapy for prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2009 Aug 15;374 (9689):534–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61343-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lau Dennis H, Schotten Ulrich, Mahajan Rajiv, Antic Nicholas A, Hatem Stéphane N, Pathak Rajeev K, Hendriks Jeroen M L, Kalman Jonathan M, Sanders Prashanthan. Novel mechanisms in the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation: practical applications. Eur. Heart J. 2016 May 21;37 (20):1573–81. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiliszek Marek, Opolski Grzegorz, Włodarczyk Piotr, Ponikowski Piotr. Cardioversion differences among first detected episode, paroxysmal, and persistent atrial fibrillation patients in the RHYTHM AF registry in Poland. Cardiol J. 2015;22 (4):453–8. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2015.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szymański Filip M, Płatek Anna E, Karpiński Grzegorz, Koźluk Edward, Puchalski Bartosz, Filipiak Krzysztof J. Obstructive sleep apnoea in patients with atrial fibrillation: prevalence, determinants and clinical characteristics of patients in Polish population. Kardiol Pol. 2014;72 (8):716–24. doi: 10.5603/KP.a2014.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abed Hany S, Wittert Gary A, Leong Darryl P, Shirazi Masoumeh G, Bahrami Bobak, Middeldorp Melissa E, Lorimer Michelle F, Lau Dennis H, Antic Nicholas A, Brooks Anthony G, Abhayaratna Walter P, Kalman Jonathan M, Sanders Prashanthan. Effect of weight reduction and cardiometabolic risk factor management on symptom burden and severity in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013 Nov 20;310 (19):2050–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pathak Rajeev K, Middeldorp Melissa E, Meredith Megan, Mehta Abhinav B, Mahajan Rajiv, Wong Christopher X, Twomey Darragh, Elliott Adrian D, Kalman Jonathan M, Abhayaratna Walter P, Lau Dennis H, Sanders Prashanthan. Long-Term Effect of Goal-Directed Weight Management in an Atrial Fibrillation Cohort: A Long-Term Follow-Up Study (LEGACY). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015 May 26;65 (20):2159–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Biase Luigi, Mohanty Prasant, Mohanty Sanghamitra, Santangeli Pasquale, Trivedi Chintan, Lakkireddy Dhanunjaya, Reddy Madhu, Jais Pierre, Themistoclakis Sakis, Dello Russo Antonio, Casella Michela, Pelargonio Gemma, Narducci Maria Lucia, Schweikert Robert, Neuzil Petr, Sanchez Javier, Horton Rodney, Beheiry Salwa, Hongo Richard, Hao Steven, Rossillo Antonio, Forleo Giovanni, Tondo Claudio, Burkhardt J David, Haissaguerre Michel, Natale Andrea. Ablation Versus Amiodarone for Treatment of Persistent Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With Congestive Heart Failure and an Implanted Device: Results From the AATAC Multicenter Randomized Trial. Circulation. 2016 Apr 26;133 (17):1637–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nademanee Koonlawee, Amnueypol Montawatt, Lee Frances, Drew Carla M, Suwannasri Wanwimol, Schwab Mark C, Veerakul Gumpanart. Benefits and risks of catheter ablation in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jan;12 (1):44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sánchez-Quintana Damián, López-Mínguez José Ramón, Pizarro Gonzalo, Murillo Margarita, Cabrera José Angel. Triggers and anatomical substrates in the genesis and perpetuation of atrial fibrillation. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2012 Nov;8 (4):310–26. doi: 10.2174/157340312803760721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewalter Thorsten, Dobreanu Dan, Proclemer Alessandro, Marinskis Germanas, Pison Laurent, Blomström-Lundqvist Carina. Atrial fibrillation ablation techniques. Europace. 2012 Oct;14 (10):1515–7. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Proietti Riccardo, Santangeli Pasquale, Di Biase Luigi, Joza Jacqueline, Bernier Martin Louis, Wang Yang, Sagone Antonio, Viecca Maurizio, Essebag Vidal, Natale Andrea. Comparative effectiveness of wide antral versus ostial pulmonary vein isolation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014 Feb;7 (1):39–45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kottkamp Hans, Bender Roderich, Berg Jan. Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: how to modify the substrate? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015 Jan 20;65 (2):196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calkins Hugh, Kuck Karl Heinz, Cappato Riccardo, Brugada Josep, Camm A John, Chen Shih-Ann, Crijns Harry J G, Damiano Ralph J, Davies D Wyn, DiMarco John, Edgerton James, Ellenbogen Kenneth, Ezekowitz Michael D, Haines David E, Haissaguerre Michel, Hindricks Gerhard, Iesaka Yoshito, Jackman Warren, Jalife Jose, Jais Pierre, Kalman Jonathan, Keane David, Kim Young-Hoon, Kirchhof Paulus, Klein George, Kottkamp Hans, Kumagai Koichiro, Lindsay Bruce D, Mansour Moussa, Marchlinski Francis E, McCarthy Patrick M, Mont J Lluis, Morady Fred, Nademanee Koonlawee, Nakagawa Hiroshi, Natale Andrea, Nattel Stanley, Packer Douglas L, Pappone Carlo, Prystowsky Eric, Raviele Antonio, Reddy Vivek, Ruskin Jeremy N, Shemin Richard J, Tsao Hsuan-Ming, Wilber David. 2012 HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: recommendations for patient selection, procedural techniques, patient management and follow-up, definitions, endpoints, and research trial design. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2012 Mar;33 (2):171–257. doi: 10.1007/s10840-012-9672-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arora PK, Hansen JC, Price AD, Koblish J, Avitall B. An Update on the Energy Sources and Catheter Technology for the Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. J Atr Fibrillation. 2010;0:12–31. doi: 10.4022/jafib.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuck Karl-Heinz, Brugada Josep, Fürnkranz Alexander, Metzner Andreas, Ouyang Feifan, Chun K R Julian, Elvan Arif, Arentz Thomas, Bestehorn Kurt, Pocock Stuart J, Albenque Jean-Paul, Tondo Claudio. Cryoballoon or Radiofrequency Ablation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016 Jun 09;374 (23):2235–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen-Scarabelli Carol, Scarabelli Tiziano M, Ellenbogen Kenneth A, Halperin Jonathan L. Device-detected atrial fibrillation: what to do with asymptomatic patients? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015 Jan 27;65 (3):281–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boriani Giuseppe, Glotzer Taya V, Santini Massimo, West Teena M, De Melis Mirko, Sepsi Milan, Gasparini Maurizio, Lewalter Thorsten, Camm John A, Singer Daniel E. Device-detected atrial fibrillation and risk for stroke: an analysis of >10,000 patients from the SOS AF project (Stroke preventiOn Strategies based on Atrial Fibrillation information from implanted devices). Eur. Heart J. 2014 Feb;35 (8):508–16. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ricci Renato Pietro, Morichelli Loredana, Santini Massimo. Remote control of implanted devices through Home Monitoring technology improves detection and clinical management of atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2009 Jan;11 (1):54–61. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reddy Vivek Y, Exner Derek V, Cantillon Daniel J, Doshi Rahul, Bunch T Jared, Tomassoni Gery F, Friedman Paul A, Estes N A Mark, Ip John, Niazi Imran, Plunkitt Kenneth, Banker Rajesh, Porterfield James, Ip James E, Dukkipati Srinivas R. Percutaneous Implantation of an Entirely Intracardiac Leadless Pacemaker. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015 Sep 17;373 (12):1125–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matusik Paweł, Dubiel Marzena, Wizner Barbara, Fedyk-Łukasik Małgorzata, Zdrojewski Tomasz, Opolski Grzegorz, Dubiel Jacek, Grodzicki Tomasz. Age-related gap in the management of heart failure patients. The National Project of Prevention and Treatment of Cardiovascular Diseases--POLKARD. Cardiol J. 2012;19 (2):146–52. doi: 10.5603/cj.2012.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rywik Tomasz M, Janas Jadwiga, Klisiewicz Anna, Leszek Przemysław, Sobieszczańska-Małek Małgorzata, Kurjata Paweł, Rozentryt Piotr, Korewicki Jerzy, Jerzak-Wodzyńska Grażyna, Zieliński Tomasz. Prognostic value of novel biomarkers compared with detailed biochemical evaluation in patients with heart failure. Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn. 2015;125 (6):434–42. doi: 10.20452/pamw.2884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Linde Cecilia, Leclercq Christophe, Rex Steve, Garrigue Stephane, Lavergne Thomas, Cazeau Serge, McKenna William, Fitzgerald Melissa, Deharo Jean-Claude, Alonso Christine, Walker Stuart, Braunschweig Frieder, Bailleul Christophe, Daubert Jean-Claude. Long-term benefits of biventricular pacing in congestive heart failure: results from the MUltisite STimulation in cardiomyopathy (MUSTIC) study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002 Jul 03;40 (1):111–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01932-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brignole Michele, Botto Gianluca, Mont Lluis, Iacopino Saverio, De Marchi Giuseppe, Oddone Daniele, Luzi Mario, Tolosana Jose M, Navazio Alessandro, Menozzi Carlo. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients undergoing atrioventricular junction ablation for permanent atrial fibrillation: a randomized trial. Eur. Heart J. 2011 Oct;32 (19):2420–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang Anthony S L, Wells George A, Talajic Mario, Arnold Malcolm O, Sheldon Robert, Connolly Stuart, Hohnloser Stefan H, Nichol Graham, Birnie David H, Sapp John L, Yee Raymond, Healey Jeffrey S, Rouleau Jean L. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for mild-to-moderate heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010 Dec 16;363 (25):2385–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng Alan, Landman Sean R, Stadler Robert W. Reasons for loss of cardiac resynchronization therapy pacing: insights from 32 844 patients. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012 Oct;5 (5):884–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.112.973776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ganesan Anand N, Brooks Anthony G, Roberts-Thomson Kurt C, Lau Dennis H, Kalman Jonathan M, Sanders Prashanthan. Role of AV nodal ablation in cardiac resynchronization in patients with coexistent atrial fibrillation and heart failure a systematic review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012 Feb 21;59 (8):719–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kleemann Thomas, Hochadel Matthias, Strauss Margit, Skarlos Alexandros, Seidl Karlheinz, Zahn Ralf. Comparison between atrial fibrillation-triggered implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shocks and inappropriate shocks caused by lead failure: different impact on prognosis in clinical practice. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2012 Jul;23 (7):735–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2011.02279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilkoff Bruce L, Fauchier Laurent, Stiles Martin K, Morillo Carlos A, Al-Khatib Sana M, Almendral Jesús, Aguinaga Luis, Berger Ronald D, Cuesta Alejandro, Daubert James P, Dubner Sergio, Ellenbogen Kenneth A, Estes N A Mark, Fenelon Guilherme, Garcia Fermin C, Gasparini Maurizio, Haines David E, Healey Jeff S, Hurtwitz Jodie L, Keegan Roberto, Kolb Christof, Kuck Karl-Heinz, Marinskis Germanas, Martinelli Martino, Mcguire Mark, Molina Luis G, Okumura Ken, Proclemer Alessandro, Russo Andrea M, Singh Jagmeet P, Swerdlow Charles D, Teo Wee Siong, Uribe William, Viskin Sami, Wang Chun-Chieh, Zhang Shu. 2015 HRS/EHRA/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on optimal implantable cardioverter-defibrillator programming and testing. Europace. 2016 Feb;18 (2):159–83. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deshmukh P, Casavant D A, Romanyshyn M, Anderson K. Permanent, direct His-bundle pacing: a novel approach to cardiac pacing in patients with normal His-Purkinje activation. Circulation. 2000 Feb 29;101 (8):869–77. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.8.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Occhetta Eraldo, Bortnik Miriam, Magnani Andrea, Francalacci Gabriella, Piccinino Cristina, Plebani Laura, Marino Paolo. Prevention of ventricular desynchronization by permanent para-Hisian pacing after atrioventricular node ablation in chronic atrial fibrillation: a crossover, blinded, randomized study versus apical right ventricular pacing. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006 May 16;47 (10):1938–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sławuta Agnieszka, Biały Dariusz, Moszczyńska-Stulin Joanna, Berkowski Piotr, Dąbrowski Paweł, Gajek Jacek. Dual chamber cardioverter-defibrillator used for His bundle pacing in patient with chronic atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015 Mar 01;182 ():395–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.12.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sławuta Agnieszka, Mazur Grzegorz, Małecka Barbara, Gajek Jacek. Permanent His bundle pacing - An optimal treatment method in heart failure patients with AF and narrow QRS. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016 Jul 01;214 ():451–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Priori Silvia G, Blomström-Lundqvist Carina, Mazzanti Andrea, Blom Nico, Borggrefe Martin, Camm John, Elliott Perry Mark, Fitzsimons Donna, Hatala Robert, Hindricks Gerhard, Kirchhof Paulus, Kjeldsen Keld, Kuck Karl-Heinz, Hernandez-Madrid Antonio, Nikolaou Nikolaos, Norekvål Tone M, Spaulding Christian, Van Veldhuisen Dirk J. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: The Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Eur. Heart J. 2015 Nov 01;36 (41):2793–867. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brignole Michele, Auricchio Angelo, Baron-Esquivias Gonzalo, Bordachar Pierre, Boriani Giuseppe, Breithardt Ole-A, Cleland John, Deharo Jean-Claude, Delgado Victoria, Elliott Perry M, Gorenek Bulent, Israel Carsten W, Leclercq Christophe, Linde Cecilia, Mont Lluís, Padeletti Luigi, Sutton Richard, Vardas Panos E, Zamorano Jose Luis, Achenbach Stephan, Baumgartner Helmut, Bax Jeroen J, Bueno Héctor, Dean Veronica, Deaton Christi, Erol Cetin, Fagard Robert, Ferrari Roberto, Hasdai David, Hoes Arno W, Kirchhof Paulus, Knuuti Juhani, Kolh Philippe, Lancellotti Patrizio, Linhart Ales, Nihoyannopoulos Petros, Piepoli Massimo F, Ponikowski Piotr, Sirnes Per Anton, Tamargo Juan Luis, Tendera Michal, Torbicki Adam, Wijns William, Windecker Stephan, Kirchhof Paulus, Blomstrom-Lundqvist Carina, Badano Luigi P, Aliyev Farid, Bänsch Dietmar, Baumgartner Helmut, Bsata Walid, Buser Peter, Charron Philippe, Daubert Jean-Claude, Dobreanu Dan, Faerestrand Svein, Hasdai David, Hoes Arno W, Le Heuzey Jean-Yves, Mavrakis Hercules, McDonagh Theresa, Merino Jose Luis, Nawar Mostapha M, Nielsen Jens Cosedis, Pieske Burkert, Poposka Lidija, Ruschitzka Frank, Tendera Michal, Van Gelder Isabelle C, Wilson Carol M. 2013 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: the Task Force on cardiac pacing and resynchronization therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). Eur. Heart J. 2013 Aug;34 (29):2281–329. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skanes A C, Krahn A D, Yee R, Klein G J, Connolly S J, Kerr C R, Gent M, Thorpe K E, Roberts R S. Progression to chronic atrial fibrillation after pacing: the Canadian Trial of Physiologic Pacing. CTOPP Investigators. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001 Jul;38 (1):167–72. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matusik Paweł, Woznica Natalia, Lelakowsk Jacek. [Atrial fibrillation before and after pacemaker implantation (WI and DDD) in patients with complete atrioventricular block]. Pol. Merkur. Lekarski. 2010 May;28 (167):345–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilkoff Bruce L, Cook James R, Epstein Andrew E, Greene H Leon, Hallstrom Alfred P, Hsia Henry, Kutalek Steven P, Sharma Arjun. Dual-chamber pacing or ventricular backup pacing in patients with an implantable defibrillator: the Dual Chamber and VVI Implantable Defibrillator (DAVID) Trial. JAMA. 2002 Dec 25;288 (24):3115–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.24.3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sharma Arjun D, Rizo-Patron Carlos, Hallstrom Alfred P, O'Neill Gearoid P, Rothbart Stephen, Martins James B, Roelke Marc, Steinberg Jonathan S, Greene H Leon. Percent right ventricular pacing predicts outcomes in the DAVID trial. Heart Rhythm. 2005 Aug;2 (8):830–4. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gillis A M, Connolly S J, Lacombe P, Philippon F, Dubuc M, Kerr C R, Yee R, Rose M S, Newman D, Kavanagh K M, Gardner M J, Kus T, Wyse D G. Randomized crossover comparison of DDDR versus VDD pacing after atrioventricular junction ablation for prevention of atrial fibrillation. The atrial pacing peri-ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (PA (3)) study investigators. Circulation. 2000 Aug 15;102 (7):736–41. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.7.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gillis Anne M. Selection of pacing mode after interruption of atrioventricular conduction for atrial fibrillation: observations from the PA3 clinical trial. Card Electrophysiol Rev. 2003 Dec;7 (4):312–4. doi: 10.1023/B:CEPR.0000023130.12304.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Israel Carsten W. The role of pacing mode in the development of atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2006 Feb;8 (2):89–95. doi: 10.1093/europace/euj038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fung Jeffrey Wing-Hong, Yu Cheuk-Man, Chan Joseph Yat-Sun, Chan Hamish Chi-Kin, Yip Gabriel Wai-Kwok, Zhang Qing, Sanderson John E. Effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy on incidence of atrial fibrillation in patients with poor left ventricular systolic function. Am. J. Cardiol. 2005 Sep 01;96 (5):728–31. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Malinowski Klaus. Spontaneous conversion of permanent atrial fibrillation into stable sinus rhythm after 17 months of biventricular pacing. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2003 Jul;26 (7 Pt 1):1554–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.t01-1-00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gasparini Maurizio, Steinberg Jonathan S, Arshad Aysha, Regoli François, Galimberti Paola, Rosier Arnaud, Daubert Jean Claude, Klersy Catherine, Kamath Ganesh, Leclercq Christophe. Resumption of sinus rhythm in patients with heart failure and permanent atrial fibrillation undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy: a longitudinal observational study. Eur. Heart J. 2010 Apr;31 (8):976–83. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hoppe Uta C, Casares Jaime M, Eiskjaer Hans, Hagemann Arne, Cleland John G F, Freemantle Nick, Erdmann Erland. Effect of cardiac resynchronization on the incidence of atrial fibrillation in patients with severe heart failure. Circulation. 2006 Jul 04;114 (1):18–25. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.614560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Padeletti Luigi, Muto Carmine, Maounis Themistoclis, Schuchert Andreas, Bongiorni Maria-Grazia, Frank Robert, Vesterlund Thomas, Brachmann Johannes, Vicentini Alfredo, Jauvert Gaël, Tadeo Giorgio, Gras Daniel, Lisi Francesco, Dello Russo Antonio, Rey Jean-Luc, Boulogne Eric, Ricciardi Giuseppe. Atrial fibrillation in recipients of cardiac resynchronization therapy device: 1-year results of the randomized MASCOT trial. Am. Heart J. 2008 Sep;156 (3):520–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roithinger F X, Cheng J, SippensGroenewegen A, Lee R J, Saxon L A, Scheinman M M, Lesh M D. Use of electroanatomic mapping to delineate transseptal atrial conduction in humans. Circulation. 1999 Oct 26;100 (17):1791–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.17.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maass Alexander H, Van Gelder Isabelle C. Atrial resynchronization therapy: a new concept for treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and prevention of atrial fibrillation? Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2012 Mar;14 (3):227–9. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sadiq Ali Fariha, Enriquez Andres, Conde Diego, Redfearn Damian, Michael Kevin, Simpson Christopher, Abdollah Hoshiar, Bayés de Luna Antoni, Hopman Wilma, Baranchuk Adrian. Advanced Interatrial Block Predicts New Onset Atrial Fibrillation in Patients with Severe Heart Failure and Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2015 Nov;20 (6):586–91. doi: 10.1111/anec.12258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ogawa M, Suyama K, Kurita T, Shimizu W, Matsuo K, Taguchi A, Aihara N, Kamakura S, Shimomura K. Acute effects of different atrial pacing sites in patients with atrial fibrillation: comparison of single site and biatrial pacing. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2001 Oct;24 (10):1470–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.01470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lewicka-Nowak Ewa, Kutarski Andrzej, Dabrowska-Kugacka Alicja, Rucinski Piotr, Zagozdzon Pawel, Raczak Grzegorz. A novel method of multisite atrial pacing, incorporating Bachmann's bundle area and coronary sinus ostium, for electrical atrial resynchronization in patients with recurrent atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2007 Sep;9 (9):805–11. doi: 10.1093/europace/eum152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Birnie David, Connors Sean P, Veinot John P, Green Martin, Stinson William A, Tang Anthony S L. Left atrial vein pacing: a technique of biatrial pacing for the prevention of atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2004 Feb;27 (2):240–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fragakis Nikolaos, Shakespeare Carl F, Lloyd Guy, Simon Ron, Bostock Julian, Holt Phyllis, Gill Jaswinder S. Reversion and maintenance of sinus rhythm in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation by internal cardioversion followed by biatrial pacing. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002 Mar;25 (3):278–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mirza Intisar, James Simon, Holt Phyllis. Biatrial pacing for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a randomized prospective study into the suppression of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation using biatrial pacing. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002 Aug 07;40 (3):457–63. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01978-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bidar Elham, Maesen Bart, Nieman Fred, Verheule Sander, Schotten Ulrich, Maessen Jos G. A prospective randomized controlled trial on the incidence and predictors of late-phase postoperative atrial fibrillation up to 30 days and the preventive value of biatrial pacing. Heart Rhythm. 2014 Jul;11 (7):1156–62. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kirchhof Paulus, Benussi Stefano, Kotecha Dipak, Ahlsson Anders, Atar Dan, Casadei Barbara, Castella Manuel, Diener Hans-Christoph, Heidbuchel Hein, Hendriks Jeroen, Hindricks Gerhard, Manolis Antonis S, Oldgren Jonas, Popescu Bogdan Alexandru, Schotten Ulrich, Van Putte Bart, Vardas Panagiotis, Agewall Stefan, Camm John, Baron Esquivias Gonzalo, Budts Werner, Carerj Scipione, Casselman Filip, Coca Antonio, De Caterina Raffaele, Deftereos Spiridon, Dobrev Dobromir, Ferro José M, Filippatos Gerasimos, Fitzsimons Donna, Gorenek Bulent, Guenoun Maxine, Hohnloser Stefan H, Kolh Philippe, Lip Gregory Y H, Manolis Athanasios, McMurray John, Ponikowski Piotr, Rosenhek Raphael, Ruschitzka Frank, Savelieva Irina, Sharma Sanjay, Suwalski Piotr, Tamargo Juan Luis, Taylor Clare J, Van Gelder Isabelle C, Voors Adriaan A, Windecker Stephan, Zamorano Jose Luis, Zeppenfeld Katja. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur. Heart J. 2016 Oct 07;37 (38):2893–2962. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ponikowski Piotr, Voors Adriaan A, Anker Stefan D, Bueno Héctor, Cleland John G F, Coats Andrew J S, Falk Volkmar, González-Juanatey José Ramón, Harjola Veli-Pekka, Jankowska Ewa A, Jessup Mariell, Linde Cecilia, Nihoyannopoulos Petros, Parissis John T, Pieske Burkert, Riley Jillian P, Rosano Giuseppe M C, Ruilope Luis M, Ruschitzka Frank, Rutten Frans H, van der Meer Peter. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2016 Jul 14;37 (27):2129–200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]