Abstract

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been recently used in clinical treatment of inflammatory diseases. Practical strategies improving the immunosuppressive property of MSCs are urgently needed for MSC immunotherapy. In this study, we aimed to develop a microRNA-based strategy to improve MSC immunotherapy. Bioinformatic analysis revealed that let-7a targeted the 3′ UTR of mRNA of Fas and FasL, both of which are essential for MSCs to induce T cell apoptosis. Knockdown of let-7a by specific inhibitor doubled Fas and Fas ligand (FasL) protein levels in MSCs. Because Fas attracts T cell migration and FasL induces T cell apoptosis, knockdown of let-7a significantly promoted MSC-induced T cell migration and apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Importantly, MSCs knocked down of let-7a were more efficient to reduce the mortality, prevent the weight loss, suppress the inflammation reaction, and alleviate the tissue lesion of experimental colitis and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) mouse models. In conclusion, knockdown of let-7a significantly improved the therapeutic effect of MSC cytotherapy on inflammatory bowel diseases and GVHD. With high safety and convenience, knockdown of let-7a is a potential strategy to improve MSC therapy for inflammatory diseases in clinic.

Keywords: apoptosis, cellular therapy, immunosuppression, mesenchymal stem cells, miRNA, T cells

Knockdown of let-7a, a conservative miRNA targeting the 3′ UTR of both Fas and FasL mRNA, elevated Fas/FasL protein levels. The increased Fas induced T cell migration, while the increased FasL triggered T cell apoptosis, providing a potential strategy to improve MSC immunotherapy for inflammatory diseases in clinic.

Introduction

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a group of heterogeneous stem cells residing in bone marrow. With potent self-renew and multi-potent differentiation capacity, MSCs play important physiological roles in bone development and hematopoiesis homeostasis.1 MSC cytotherapy has been applied into a wide range of regenerative medicine.2, 3, 4 One of the most exciting findings is that MSCs possess immunomodulatory property. Numbers of animal experiments and preclinical trials revealed that MSCs potently inhibit T cell proliferation, survival, and function.5, 6, 7 Recently, MSCs have been successfully applied in the treatment of immune and inflammatory diseases, including graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), lupus, etc., and achieved encouraging outcomes.8, 9, 10, 11 Until now, hundreds of clinical trials of MSC therapy for inflammatory diseases have been performed in many countries.11 MSC immunotherapy is becoming one of the most attractive and productive fields of MSC research and application.

However, a number of phase III trials of MSC immunotherapy are unable to meet the primary clinical endpoints because of the low efficacy of engrafted cells.8 How to improve the immunosuppressive property of MSC emerges as one of the crucial issues of MSC therapy. Recently, Shi and colleagues12 found that Fas ligand (FasL)/Fas system expressed on MSCs is crucial for MSC therapy of inflammatory diseases. Fas enhances the migration of T cells, whereas FasL activates the apoptosis pathway in T cells.13 MSCs knocked out of Fas or FasL largely lost their capacity to treat inflammatory colitis and systemic sclerosis,12 suggesting that elevating Fas and FasL expression in MSCs would improve MSC therapy. However, as FasL/Fas might induce MSC apoptosis,14 it is essential to maintain their levels at proper scale. Since traditional gene overexpression strategies could not control the levels of gene expression accurately, it remains difficult to improve the therapeutic effect of MSCs by modulating FasL/Fas.

Recent attempts targeting microRNAs (miRNAs) to treat diseases provide us a promise.15, 16, 17, 18 miRNAs, a family of endogenous 22- to 24-bp non-coding RNAs, are important modulators of cell function.19 miRNAs silence gene expression post-transcriptionally by binding to the 3′ UTR of mRNA.19 Because of their specific action mode, miRNAs usually decrease target gene expression by ∼50%.20 Therefore, knockdown of miRNAs could enhance their target gene expression mildly. A number of miRNA-knockout animal models confirm that knockout of one miRNA usually results in no violent phenotype.21 Moreover, with developed strategies to knock down miRNAs,22, 23 miRNAs are becoming potential therapeutic targets of diseases such as hepatitis C and ischemic heart disease.16, 18 Recently, our group also reported a miRNA-based method to promote bone regeneration of MSCs.24 The efficacy and safety of miRNA-based strategies encouraged us to explore its applications in MSC immunotherapy.

Here, by identifying miRNAs targeting the mRNA of Fas and FasL, we aimed to develop a miRNA-based strategy to improve MSC therapy for inflammatory diseases.

Results

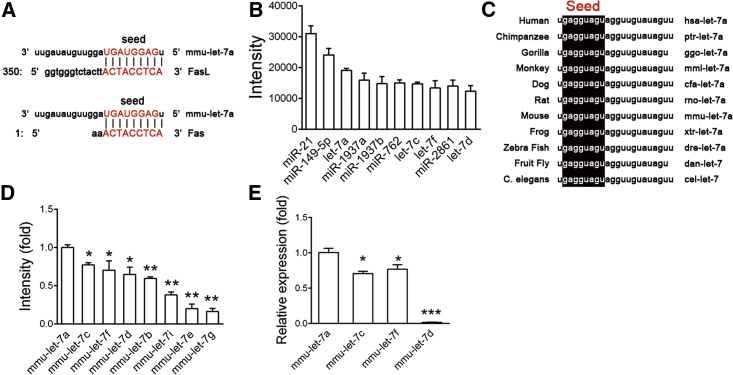

Knockdown of let-7a Enhances Fas and FasL Protein Levels in MSCs

MicroRNAs inhibit target gene expression by complementarily binding to the 3′ UTR of mRNAs.20 We took an in silico approach to find miRNAs that could regulate Fas and FasL.25 Based on three databases (TargetScan,26 miRNA,27 and Microcosm Target [http://www.ebi.ac.uk/enright-srv/microcosm/htdocs/targets/v5/]), we found a number of miRNAs that could target Fas and FasL mRNA of mouse and human (Table 1). Notably, let-7 family members were the only conservative miRNAs predicted by all databases (Figure 1A; Table 1). According to our previous miRNA microarray data,28 let-7 family was one of the most highly expressed miRNA families in MSCs (Figure 1B). Among all members of let-7 family, let-7a was the most conservative one across different species (Figure 1C). The expression levels of let-7a were the highest among all let-7 family members in MSCs (Figures 1D and 1E). Moreover, let-7a has been identified to target Fas mRNA in cancer cells and immune cells.29, 30 So we chose let-7a as the candidate.

Table 1.

Predicted miRNAs targeting 3′ UTR of Fas and Fasl mRNA

| Mouse |

Human |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TargetScan | MicroRNA | Microcosm | TargetScan | MicroRNA | Microcosm |

|

FasL | |||||

| miR-1961 | miR-194 | miR-466d-3p | miR-4458 | miR-149 | miR-136 |

| miR-98 | let-7g | miR-466a-3p | let-7d | miR-186 | miR-674 |

| let-7b | let-7i | miR-297a-3p | let-7e | miR-219-5p | miR-29b-2-3p |

| let-7a | let-7a | miR-466b-3-3p | let-7b | miR-708 | miR-98 |

| let-7e | let-7c | miR-98 | miR-4500 | miR-28-5p | miR-875-3p |

| let-7f | miR-98 | miR-21 | let-7a | miR-24 | miR-543 |

| let-7c | let-7f | miR-338-5p | let-7c | miR-21 | miR-491-3p |

| let-7g | let-7b | miR-467a-3p | miR-98 | miR-590-5p | miR-27b |

| let-7d | let-7d | let-7c | let-7g | miR-302c | miR-520d-3p |

| let-7i | miR-590-3p | let-7b | let-7i | miR-372 | let-7a |

| miR-216a | let-7a | let-7f | let-7b | let-7c | |

| miR-186 | miR-467e-3p | miR-98 | miR-194-3p | ||

| miR-149 | let-7i | miR-543 | miR-28-5p | ||

| miR-24 | miR-467b-3p | miR-203 | miR-520h | ||

| let-7e | miR-466 g | let-7a | let-7d | ||

| miR-494 | let-7d | let-7c | miR-27a | ||

| miR-543 | miR-880 | let-7e | let-7b | ||

| miR-21 | let-7g | let-7g | miR-520 g | ||

| miR-590-5p | let-7e | let-7i | miR-363 | ||

| miR-290-5p | let-7f | let-7f | let-7i | ||

| miR-292-5p | miR-466f-3p | let-7d | let-7e | ||

| miR-25 | miR-367 | miR-136 | miR-219-1-3p | ||

| miR-363 | miR-717 | miR-302a | miR-146b-3p | ||

| miR-92a | miR-363 | miR-302b | let-7g | ||

| miR-92b | miR-377 | miR-302d | miR-219-5p | ||

| miR-32 | miR-181c | miR-520a-3p | miR-520a-3p | ||

| miR-367 | miR-181a | miR-520b | miR-605 | ||

| miR-181c | miR-590-5p | miR-520c-3p | let-7f | ||

| miR-18b | miR-194 | miR-520d-3p | miR-627 | ||

| miR-181a | miR-25 | miR-92a | miR-22-3p | ||

|

Fas | |||||

| miR-23a | miR-23a | miR-484 | miR-98 | miR-374b | miR-708-3p |

| miR-23b | miR-23b | miR-665 | let-7b | miR-374a | miR-28-3p |

| miR-1903 | miR-411 | miR-23a | let-7c | miR-376a | miR-548c-3p |

| miR-692 | miR-141 | miR-218-2-3p | let-7a | miR-448 | miR-432 |

| miR-150 | miR-200a | miR-302b-3p | let-7i | miR-19a | miR-520 g |

| miR-5127 | miR-410 | miR-376a-3p | let-7f | miR-19b | miR-520h |

| miR-532-3p | miR-496 | miR-467e-3p | let-7e | miR-23a | miR-362-5p |

| miR-1894-5p | miR-376c | miR-467b-3p | miR-4500 | miR-23b | miR-16-1-3p |

| miR-207 | let-7a | miR-467a-3p | let-7g | miR-27a | miR-545 |

| miR-324-5p | let-7b | miR-876-3p | let-7d | miR-27b | miR-202-3p |

| miR-143 | let-7c | miR-582-5p | miR-4458 | miR-196a | miR-561 |

| miR-376c | let-7d | let-7i | miR-196b | miR-548d-3p | |

| miR-136 | let-7e | miR-98 | miR-181c | miR-15b-3p | |

| miR-3473c | let-7f | let-7f | miR-181d | miR-650 | |

| miR-335-3p | let-7g | miR-30b | miR-181a | miR-34b-3p | |

| miR-684 | let-7i | let-7g | miR-181b | miR-374a-3p | |

| miR-1969 | miR-98 | let-7c | miR-425 | miR-181b | |

| miR-27a | miR-362-3p | miR-186 | let-7e | miR-768-5p | |

| miR-27b | miR-329 | let-7a | let-7d | let-7i | |

| miR-673-5p | miR-196a | miR-196b | let-7a | miR-181c | |

| miR-29b | miR-196b | miR-493 | let-7b | miR-216b | |

| miR-29a | miR-25 | let-7b | let-7c | miR-569 | |

| miR-29c | miR-92a | miR-196a | let-7f | miR-136 | |

| miR-92b | miR-493 | miR-98 | miR-325 | ||

| miR-363 | miR-496 | let-7g | miR-448 | ||

| miR-367 | miR-133a-3p | let-7i | let-7d | ||

| miR-32 | miR-376c | miR-216b | miR-34a | ||

| miR-217 | miR-325 | miR-22 | miR-190b | ||

| miR-376b | miR-883a-3p | miR-361-5p | let-7c-3p | ||

| miR-182 | miR-217 | miR-30e | |||

Figure 1.

let-7a Is Predicted to Bind to the 3′ UTR of Fas and FasL mRNA

(A) Predicted binding sites between let-7a and the 3′ UTR of Fas mRNA or FasL mRNA. (B) The most highly expressed miRNAs in MSCs detected by miRNA microarray. (C) The sequence of let-7a of different species. (D) Relative expression levels of let-7 family members in MSCs were detected by miRNA microarray. (E) The expression of let-7 family members in MSCs was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR analysis. Data are presented as means ± SD, n = 3. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

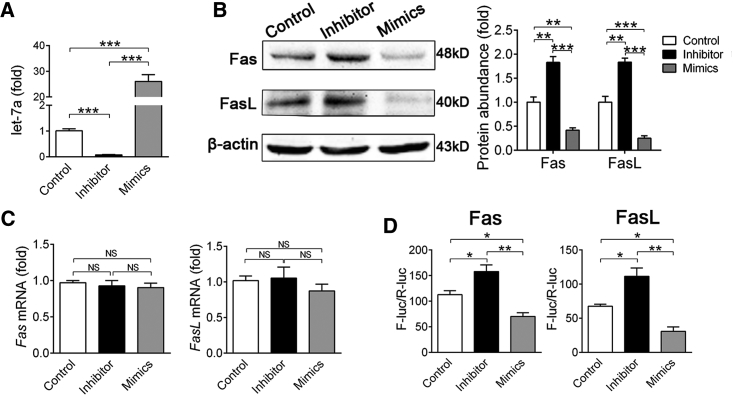

To confirm the in silico prediction, we performed gain- and loss-of-function assay using synthetic oligonucleotides that mimicked let-7a (mimics) or were complementary to let-7a (inhibitor).28 MSCs used in this study highly expressed mesenchymal stem cell markers (Sca-1, CD29, CD73, CD90, and CD105) and were negative for hematopoietic cell markers (CD34 and CD45) (see also Figure S1A), possessed self-renew ability (see also Figure S1B), and multi-potent differentiation property (see also Figures S1C and S1D). Twenty-four hours after transfection, real-time RT-PCR confirmed that let-7a mimics or inhibitor were highly efficient to overexpression or knockdown let-7a expression (Figure 2A). let-7a inhibitor did not affect the expression of other members of let-7 family (see also Figure S2A) and its effectiveness could last for 4 days (see also Figure S2B). Of note, western blotting showed that knockdown of let-7a elevated both Fas and FasL protein accumulation 2-fold, whereas overexpression of let-7a decreased Fas and FasL protein levels by ∼60% in MSCs (Figure 2B). Accordingly, we did not detect significant change of Fas and FasL mRNA levels after let-7a knockdown or overexpression (Figure 2C). To confirm let-7a binds directly to Fas and FasL mRNA, we constructed luciferase reporters containing 3′ UTR of Fas or FasL mRNA. Likewise, let-7a inhibitor significantly increased the luciferase activity, whereas let-7a mimics decreased the luciferase activity of both reporters (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

let-7a Inhibits Both Fas and FasL Protein Accumulation

(A–C) MSCs were transfected with let-7a mimics, let-7a inhibitor or negative control for 48 hr. (A) Real-time RT-PCR was performed to confirm the efficacy of let-7a mimics and inhibitor. (B) Western blotting was performed to detect Fas and FasL protein accumulation in MSCs. Relative protein abundance was measured using ImageJ software. The gray value of each blot was normalized to the value of β-actin. (C) Real-time RT-PCR was performed to measure mRNA levels of Fas and FasL. (D) Luciferase reporter plasmid and let-7a mimics, inhibitor or negative control were co-transfected into MSCs for 48hr, and the reporter luciferase activities were measured. Data are presented as means ± SD, n = 3/group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Because the binding of FasL and Fas could trigger extrinsic apoptosis pathway, we also explored whether knockdown of let-7a increases the apoptosis of MSCs. Flow cytometer (FCM) assay revealed that only 0.2∼0.3% MSCs underwent apoptosis even after let-7a inhibitor transfection, indicating that knockdown of let-7a did not induce auto-apoptosis of MSCs (see also Figure S3).

Knockdown of let-7a Promotes MSC-Induced T Cell Migration and Apoptosis In Vitro

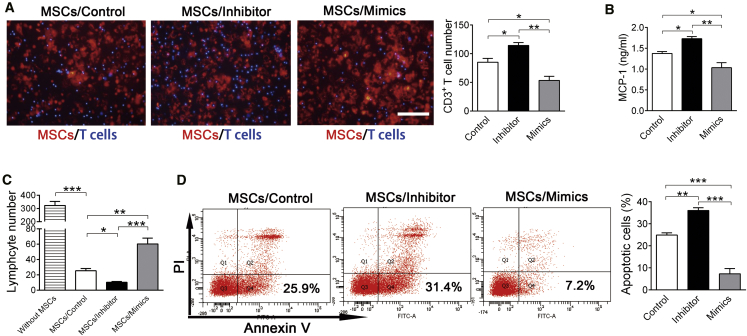

We examined whether knockdown of let-7a promotes MSC-induced T cell apoptosis. Because only the membrane-bound FasL is essential for Fas-induced T cell apoptosis,31 MSCs need to recruit T cells first. Using an in vitro Transwell System, we confirmed that knockdown of let-7a in MSCs indeed promoted T cell migration, whereas overexpression of let-7a inhibited MSC-induced T cell migration (Figure 3A). Fas protein on MSC membrane promotes T cell migration by increasing the release of chemokines such as monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1).12 As a potential explanation for the modulation in lymphocyte migration, we found that knockdown of let-7a significantly increased MCP-1 secretion, whereas overexpression of let-7a decreased MCP-1 secretion by MSCs (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Knockdown of let-7a Increases MSC-Induced T Cell Migration and Apoptosis

MSCs were transfected with let-7a mimics, let-7a inhibitor or negative control for 24 hr before the following experiments. (A) MSCs (PKH26 labeled) transfected with let-7a mimics, let-7a inhibitor or negative control were co-cultured with activated CD3+ T cells (hoechst labeled) in a Transwell system for 24 hr. Migrated T cell number was calculated under a fluorescence microscope. n = 3/group. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) MCP-1 levels in culture medium of transfected MSCs were detected by ELISA. n = 3/group. (C and D) MSCs transfected with let-7a mimics, let-7a inhibitor, or negative control were co-cultured with activated CD3+ T cells. Forty-eight hours after co-culture, FCM was performed to detect T cell number (C) (n = 3/group) and T cell apoptosis (D) (n = 4/group). Data are presented as means ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Next, we investigated whether knockdown of let-7a promotes MSC-induced T cell apoptosis using an in vitro direct co-culture model. As previously reported,12 FCM showed that T cell number was significantly decreased by ∼90% after co-culture with MSCs. Of note, knockdown of let-7a promoted MSCs to decrease T cell number, whereas overexpression of let-7a inhibited the effect of MSCs on T cells (Figure 3C). Apoptosis assay confirmed that knockdown of let-7a in MSCs elevated the apoptotic rate of T cells, whereas overexpression of let-7a in MSCs lowered the apoptotic rate of T cells after co-culture (Figure 3D). These findings indicated that knockdown of let-7a promoted MSCs to induce T cell migration and apoptosis.

Because let-7a is a highly expressed miRNA targeting a number of important mRNAs, we also explored whether let-7a regulates other characteristics of MSCs. Gain- and loss-of-function assay showed that let-7a inhibited the proliferation and colony forming of MSCs (see also Figures S4A and S4B), whereas promoted the differentiation of MSCs (see also Figures S4C and S4D). However, let-7a did not affect the migration of MSCs after injection (see also Figure S4E).

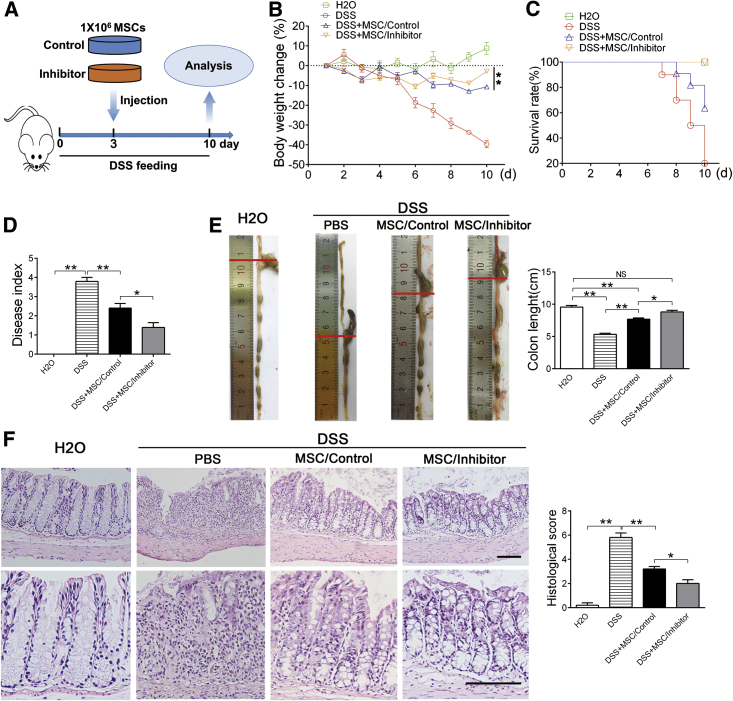

Knockdown of let-7a Improves MSC Therapy for Inflammatory Colitis

MSC therapy has been applied for a number of inflammatory diseases, such as GVHD, Crohn’s disease, lupus et al.5, 10, 32 Among the majority of these diseases, activated T cells play central roles in disease development and pathological damage. Because knockdown of let-7a promoted MSC-induced T cell apoptosis in vitro, we further explored whether knockdown of let-7a enhances the therapeutic effect of MSCs in vivo using an experimental colitis mouse model.33 Three days after oral administration of dextran sulfate sodium salt (DSS), the mice were injected with MSCs transfected with let-7a inhibitor or negative control via tail vein (Figure 4A). Ten days after oral administration of DSS, obvious body weight loss, diarrhea, fecal bleeding, and mortality were observed in PBS-injected mice (Figures 4A–4D). Confirmed with previous reports,12 injection of MSCs alleviated all symptoms of acute colitis (Figures 4A–4D). As anticipated, MSCs transfected with let-7a inhibitor (MSCs/inhibitor) were more potent to prevent the body-weight loss (Figure 4B), reduce the mortality (Figure 4C), and alleviate colitis symptom (Figure 4D), compared with MSCs transfected with negative control (MSCs/control).

Figure 4.

Knockdown of let-7a Improves the Effect of MSC Therapy on Experimental Colitis

(A) Experiment design. Mice were fed with drinking water containing DSS for 10 days. At the third day, 1 × 106 MSCs transfected with 150 nM let-7a inhibitor or negative control were injected into the mice via tail vein. (B) The body weight was recorded daily for 10 days. n = 5/group. (C) The mortality of mice was recorded for 10 days. n = 10/group. (D) Disease index was measured at day 10 of DSS feeding. n = 5/group. (E) The colons of each group were collected after 10 days and their lengths were measured. n = 5/group. (F) Histological structure of the colon was detected by H&E staining, and the histological score was measured. n = 5/group. The images at the bottom are higher magnifications of the images at the top. Scale bar, 200 μm. Data are presented as means ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

To further confirm that knockdown of let-7a improves MSC treatment for colitis, we harvested the colons for histological examination. Accordingly, injection of MSCs ameliorated the colon length reduction (Figure 4E), lymphocytes infiltration, and mucosa membrane destruction caused by DSS (Figure 4F). Consistent with the symptom, MSCs transfected with let-7a inhibitor were more effective than the control MSCs to ameliorate lymphocyte infiltration and tissue damage (Figures 4E and 4F). Taken together, these results indicated that knockdown of let-7a promotes MSC therapy of experimental colitis.

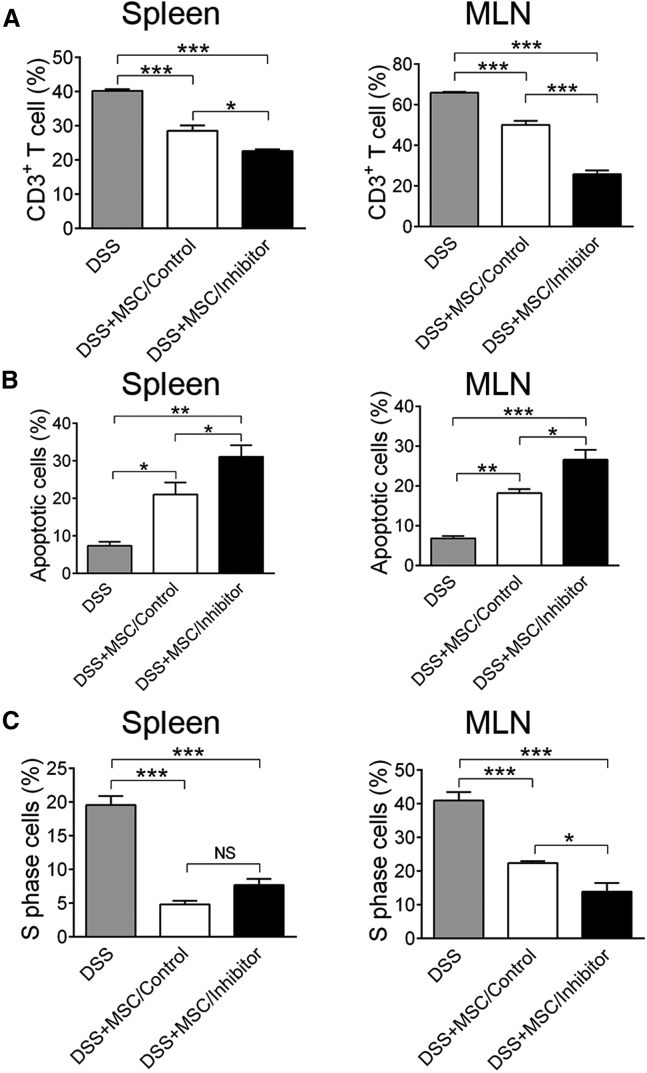

Knockdown of let-7a Increases MSC-Induced T Cell Apoptosis by Enhancing FasL/Fas Expression

To investigate whether knockdown of let-7a improves MSC immunotherapy by inducing T cell apoptosis, we detected CD3+ T cells in the spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) of the experimental colitis mice. FCM showed that administration of MSCs reduced the ratio of CD3+ T cell in mononuclear cells in the spleen and MLN (Figure 5A). Of note, knockdown of let-7a in MSCs further reduced CD3+ T cell ratio in cells of spleen and MLN, compared with the MSC/control group (Figure 5A). Moreover, apoptosis analysis showed that MSC injection significant elevated the apoptotic rate of T cells in both spleen and MLN (Figure 5B). MSCs/inhibitor injection further enhanced the apoptotic rate of T cells by 10% compared with the MSC/control group (Figure 5B). Because MSCs could also inhibit T cell proliferation, we examined the cell cycle of CD3+ T cells. As reported,34 administration of MSCs significantly reduced the ratio of S phase CD3+ T cells in both spleen and MLN (Figure 5C). However, the cell cycle of CD3+ T cells was similar between the MSCs/inhibitor and the MSCs/control groups (Figure 5C), ruling out that knockdown of let-7a promoted MSC to suppress T cell proliferation.

Figure 5.

Knockdown of let-7a Increases MSC-Induced T Cell Apoptosis In Vivo

Ten days after oral administration of DSS, lymphocytes were collected from the spleen and mesenteric lymph node (MLN) of mice injected with PBS, MSC/control, or MSC/inhibitor. (A) FCM was performed to detect the percentage of CD3+ T cells in lymphocytes of the spleen and MLN. (B) FCM was performed to measure the apoptotic rate of CD3+ T cells in the spleen and MLN. (C) Cell cycle of CD3+ T cells in the spleen and MLN was measured by FCM. Data are presented as means ± SD, n = 4/group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

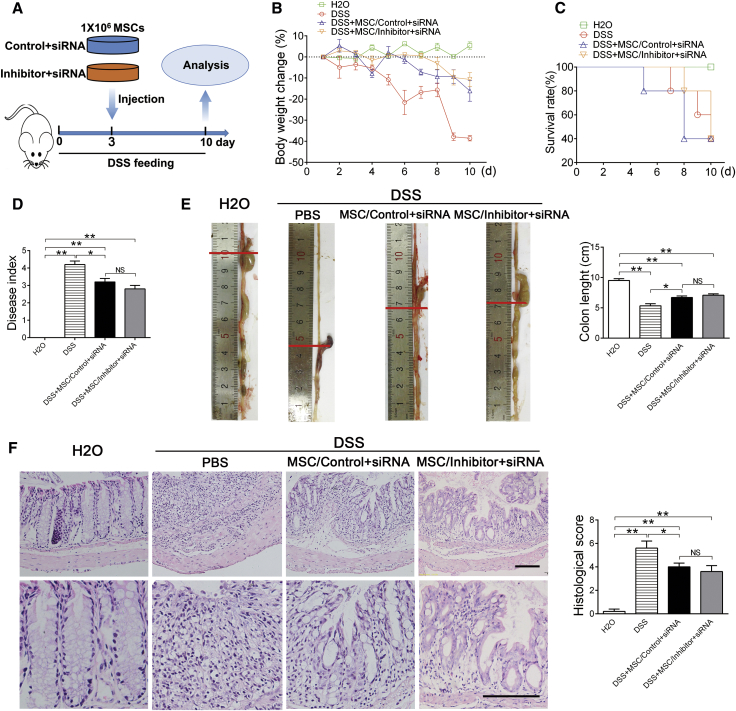

One miRNA could modulate the expression of hundreds of genes.35 Because in vitro analysis showed that let-7a also modulated the self-renew and differentiation of MSCs (see also Figures S4A–S4D), it is necessary to confirm that whether knockdown of let-7a functions by upregulating FasL/Fas protein levels in MSCs. To do this, we knocked down Fas and FasL in MSCs by transfecting two small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) specific to Fas and FasL. Real-time RT-PCR and western blotting confirmed that these siRNAs inhibited FasL and Fas expression efficiently (see also Figures S5A and S5B). We then co-transfected let-7a inhibitor with Fas and FasL siRNA into MSCs and tested the therapeutic effect of MSCs on experimental colitis (Figure 6A). After knockdown of FasL/Fas, let-7a inhibitor no longer improved the effect of MSCs on reducing the body weight loss, lethality, and disease index of the colitis mice (Figures 6B–6D). Histological assay of the colon also confirmed that knockdown of let-7a in MSCs lack of FasL/Fas did not improved MSC therapy for colitis (Figures 6E and 6F).

Figure 6.

Knockdown of let-7a Improves MSC Cytotherapy through FasL/Fas

(A) Experiment design. MSCs were co-transfected with Fas siRNA, FasL siRNA, and let-7a inhibitor or negative control for 48 hr. The transfected MSCs were injected into mice at day 3 of DSS feeding. (B) The body weight was recorded every day for 10 days after DSS feeding. (C) The mortality of mice was recorded for 10 days. (D) Disease index was measured at day 10. (E) The colons of each group were collected after 10 days and their lengths were measured. (F) Histological structure of the colon was detected by H&E staining, and the histological score was measured. The images at the bottom are higher magnifications of the images at the top. Scale bar, 200 μm. Data are presented as means ± SD, n = 5/group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

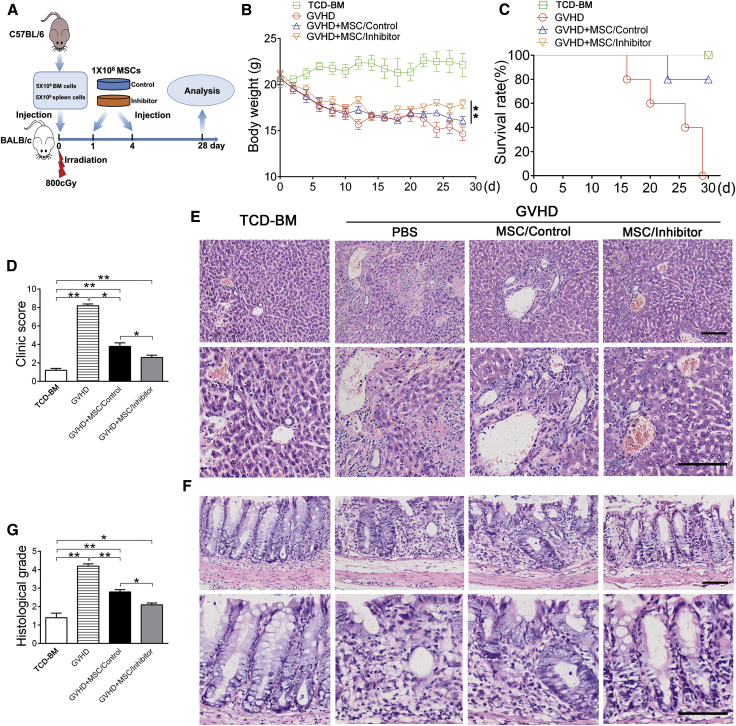

Knockdown of let-7a Improves MSC Therapy for GVHD

Next, we identified whether our approach generally works in the treatment of other inflammatory diseases. To do this, we adopted an experimental GVHD model induced by MHC-uncoupled heterogenic bone marrow transplantation (BMT). MSCs transfected with let-7a inhibitor or negative control were administered via tail vein at days 1 and 4 of BMT (Figure 7A). Four weeks after the BMT, the mice showed serious symptoms of GVHD, including body weight loss, death, activity retardation, and skin change (Figures 7B–7D). Consistent with a previous study,9 administration of MSCs improved all symptoms of GVHD (Figures 7B–7D). Importantly, MSCs transfected with let-7a inhibitor (MSCs/inhibitor) were more effective to improve the symptoms, compared with MSCs/control infusion (Figures 7B–7D).

Figure 7.

Knockdown of let-7a Promotes the Effect of MSC Therapy on GVHD

(A) Experiment design. BALB/c mice were suffered 800 cGy irradiation and injected with bone marrow and spleen cells isolated from C57BL/6 mice. BALB/c mice injected with T cell-depleted BM cells (TCD-BM) of C57BL/6 mice were used as normal control. A total of 1 × 106 MSCs (BALB/c) transfected with let-7a inhibitor (MSC/inhibitor) or negative control (MSC/control) were administered via tail vein at the first and the fourth day. (B) The body weight was recorded daily for 28 days after bone marrow transplantation (BMT). (C) The mortality of mice was recorded for 28 days after BMT. (D) The clinic score of GVHD was measured at day 25 after BMT. (E) Histopathological changes of the liver collected 25 days after BMT were detected by H&E staining. (F) Histopathological changes of the colon were detected by H&E staining. The images at the bottom are higher magnifications of the black-boxed regions at the top. Scale bar, 200 μm. (G) The histological score of GVHD was measured 25 days after BMT. Data are presented as means ± SD, n = 5/group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

To further confirm the effect of let-7a knockdown, we performed histological analysis of the liver and colon, two major organs attacked by T cells in GVHD. In accordance with the symptoms, H&E staining showed excessive lymphocytes infiltration and tissue damage in the bile ducts and portal triads of liver and the mucosa of colon, which were obviously reduced by administration of MSCs (Figures 7E and 7F). Moreover, MSCs/inhibitor infusion resulted in better improvement of T cell infiltration and tissue damage compared with the control MSCs (Figures 7E–7G). These results indicated that knockdown of let-7a improves MSC treatment for GVHD.

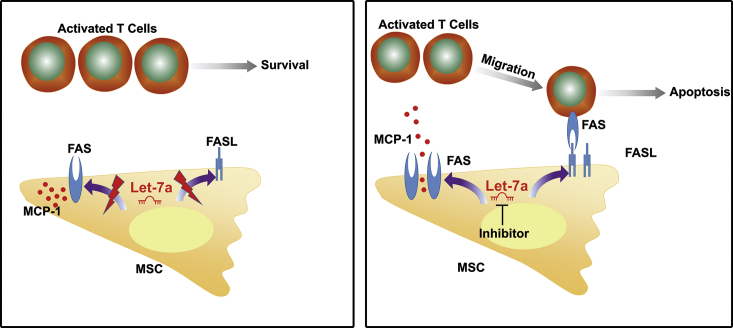

Finally, we identified a miRNA-based strategy to improve MSC therapy for inflammatory colitis and experimental GVHD (Figure 8). Knockdown of let-7a, a conservative miRNA targeting the 3′ UTR of both Fas and FasL mRNA, elevated Fas and FasL protein levels in MSCs by nearly 2-fold. The increased Fas activated MCP-1 secretion to induce T cell migration, whereas the increased FasL triggered extrinsic apoptosis pathway in T cells. Therefore, knockdown of let-7a significantly improved the therapeutic effect of MSCs on colitis and other inflammatory diseases. Considering the safety and convenience of knockdown of miRNAs, our findings provided a potential strategy to improve MSC immunotherapy for inflammatory diseases in clinic.

Figure 8.

Model for Knockdown of let-7a to Improve MSC Therapy

let-7a in MSCs works as a suppressor of Fas and FasL protein accumulation. Knockdown of let-7a by miRNA inhibitor enhances the levels of both Fas and FasL protein. The increased Fas activates the secretion of MCP-1 to induce T cell migration, whereas the increased FasL induces T cell apoptosis. Therefore, knockdown of let-7a improves MSC therapy for inflammatory diseases.

Discussion

How to improve the therapeutic effect of MSCs is becoming an urgent issue for clinical application of MSC therapy. FasL/Fas are recently disclosed to be essential for MSCs to induce Th cell apoptosis and suppress immune reaction.12, 13 Here, we developed an applicable method to improve MSC immunotherapy by enhancing FasL/Fas expression. We identified let-7a as a negative modulator of FasL/Fas expression by targeting the 3′ UTR of both Fas and FasL mRNA. Knockdown of let-7a by inhibitor enhanced FasL/Fas protein levels nearly 2-fold, which avoided auto-apoptosis of MSCs induced by excessive FasL/Fas. Accordingly, knockdown of let-7a significantly promoted Fas-induced T cell migration and FasL-induced T cell apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, knockdown of let-7a in MSCs significantly improved their therapeutic effect on IBD and GVHD by enhancing FasL/Fas expression. Taken together, our findings indicated that moderately enhancement of FasL/Fas expression by regulating miRNAs is a promising strategy to improve MSC cytotherapy.

Growing evidences implicate that miRNAs exert their effects in numerous physiological and pathological processes.19, 21 miRNAs are becoming intriguing targets for disease treatment. Lanford and colleagues found that therapeutic silencing of miR-121 led to long-lasting suppression of hepatitis C virus viremia.18 Hu and colleagues used miR-210 to improve angiogenesis and cardiac function in murine model of myocardial infarction.16 miRNA-based treatment has also been applied to a number of tumors.17, 36, 37 Recently, Hu and co-workers applied a miRNAs cocktail to improve cardiac progenitor cells engraftment and functions in transplantation.38 Our group also developed a miRNA-based strategy to enhance bone formation of MSCs.24 However, no attempt is carried out to improve MSC immunotherapy through miRNAs. In this study, we identified that knockdown of let-7a by miRNA inhibitor significantly enhanced the function of MSCs to kill T cells and ameliorate inflammatory diseases, indicating that miRNA-based strategies could also be applied in MSC immunotherapy.

It is interesting that knockdown of let-7a enhanced Fas and FasL expression but induced no significant auto-apoptosis of MSCs. The observation is supported by previous reports that MSCs induce apoptosis of osteoclasts and T cells by FasL without inducing themselves apoptosis.12, 39 This might be due to the high resistance of stem cells to apoptosis, which is essential for their long-term maintenance in vivo. Comparatively, T cells, the half-life of which is only 2 weeks, are highly dynamic in vivo. Furthermore, T cells are much more sensitive to FasL/Fas signaling and more prone to apoptosis.31 We observed that the spontaneous apoptotic rate of T cells was much higher than that of MSCs. These evidences partly explained the phenomenon that knockdown of let-7a did not induce auto-apoptosis of MSCs.

let-7a is one of the most confluent miRNAs in mammalian cells. Numbers of studies have revealed the functions of let-7a in development, tumorigenesis, stem cell, and aging.40, 41, 42 A number of certified targets of let-7 are crucial modulators of stem cell functions. let-7 suppresses the expression of Cdc34, RAS, and E2F5, the key regulators of cell proliferation, to inhibit the expansion of stem cells.42, 43, 44 let-7 targets LIN28, HMGA2, and MYC, which are important for maintenance of pluripotency, to promote stem cell differentiation.40, 45, 46, 47, 48 Recently, Wei and colleagues showed that let-7 enhances osteogenesis and bone formation of human MSCs by regulating HMGA2, suggesting that let-7a suppresses these genes to regulate the functions of MSCs. In this study, we observed that let-7a inhibited the proliferation and self-renew of MSCs, whereas promoted the differentiation of MSCs. There raises a question that whether let-7a affects MSC immunotherapy by targeting other genes besides Fas/FasL. At present, no conclusive studies showed that injected exogenous MSC could proliferate in the hosts. Because we used equal number of MSCs in the in vivo and in vitro assay, the influence of let-7a on MSC proliferation might be trivial in MSC therapy. Accordingly, knockdown of Fas and FasL largely blocked the effect of let-7a in MSC therapy. However, because LIN28, MYC, and RAS could activate various downstream events, it is possible that these genes affect the immunoregulatory property of MSCs indirectly. Furthermore, let-7 could suppress components of the amino acid sensing pathway (Map4k3, RagC, and RagD) to induce autophagy,49 which are crucial for therapeutic potential of MSC in autoimmune diseases.50 Therefore, we could not exclude the possibility that let-7a functions through other targets. Further investigation is needed to identify the molecular network of let-7a in MSC-induced immunosuppression.

Hyperfunction of Th cells causes numbers of inflammatory diseases including inflammatory colitis, GVHD, lupus, and systemic sclerosis. At present, no ideal therapy is available for a certain percentage of these diseases. Recently, MSCs have been used to treat lupus and systemic sclerosis in pre-clinic trials.10 In this study, we investigated the effect of let-7a knockdown in MSC therapy for GVHD and inflammatory colitis. We found that knockdown of let-7a significantly improved MSC treatment for both inflammatory colitis and GVHD, suggesting it is an effective approach for treatment of Th cell-mediated inflammatory diseases. Therefore, it is important to identify whether let-7a knockdown can improve MSC therapy for other inflammatory diseases in further studies.

The inflammation in gastrointestinal tract is controlled by the balance between effector T cells and regulatory T cells (Tregs). Previous studies indicate that apoptotic T cells trigger transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) production by macrophages and upregulate Tregs.51 Accordingly, systemic infusion of MSCs elevates Treg levels in peripheral blood.12 Because let-7a inhibitor promoted MSC-induced T cell apoptosis, knockdown of let-7a in MSCs might also enhance Treg levels after cell therapy, resulting in rebalance of immune system. Further analysis is necessary to confirm the subsequent effect after infusion of MSCs knocked down of let-7a.

A number of genetic methods have been applied to improve MSC cytotherapy. For example, MSCs transduced with TGF-β using adenoviral expression vectors were more efficient to ameliorate experimental autoimmune arthritis.52 MSCs transfected with ANGPT1 plasmid could reduce lipopolysaccharide-induced acute pulmonary inflammation.53 MSCs overexpressing Bcl-2 improve the functional recovery after acute myocardial infarction.54 In this study, we provided a novel attempt to improve the therapeutic activity of MSCs through post-transcriptional regulation. Transient transfection of let-7a inhibitor reduced let-7a expression efficiently over 4 days. According to previous studies and our studies, most of the injected MSCs were eliminated by the host within a few days. Therefore, the time duration of transient transfection to knock down let-7a was sufficient to improve MSCs therapy. Furthermore, because stable transfection using virus vectors has potential risks in clinical application, transient transfection would be more practical and safer to regulate miRNA expression. Based on the development of miRNA research, miRNA-based strategy might be promising to improve MSC cytotherapy in clinic.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Female C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks) were purchased from the Animal Center of Fourth Military Medical University. Female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks) were purchased from the Animal Center of Xi’an Jiaotong University. C57BL/6 mice were used in the most of the experiments, whereas BALB/c mice were only used to construct the experimental GVHD models. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Use and Care Committee of the Fourth Military Medical University and performed under the Guidelines of Intramural Animal Use and Care Committee of the Fourth Military Medical University. All mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions (22°C, 12-hr light/12-hr dark cycles, and 50%–55% humidity) with free access to food pellets and tap water.

Cell Culture

For MSC culture, bone marrow cells were flushed from C57BL/6 mouse femurs and tibias using α-MEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Shijiqing), 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). The cell suspension was plated in 10-cm culture dishes and incubated at 37°C in a humidity incubator with 5% CO2. The medium was changed every 3 days to clear non-adherent cells. When the cells reached 80%–90% confluence, MSCs were detached with 0.25% trypsin/1 nM EDTA (Invitrogen) and passaged. After passage, MSCs received routine characterization. MSCs used in the study highly expressed mesenchymal stem cell markers (Sca-1, CD29, CD73, CD90, and CD105) and were negative for hematopoietic cell markers (CD45 and CD34), possessed self-renew ability and multi-potent differentiation property.28 MSCs at two to three passages were used in this study.

For lymphocyte culture, cell suspension was collected by crashing the spleen or mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) of C57BL/6 mice. Red blood cell lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to wipe off red blood cells. The lymphocyte suspension was plated in culture dishes with RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1% penicillin and streptomycin.

MSCs and T cells derived from C57BL/6 mice were used in all cellular experiments and experimental colitis treatment assay unless otherwise stated.

Characterization of MSCs

For characterization of MSCs, proliferation assay and fibroblastic colony-forming assay were performed to detect the self-renew of MSCs as we reported previously.55 Osteogenesis assay and adipogenesis assay were performed to detect the multi-potent differentiation of MSCs as we reported previously.28

miRNA Microarray and Data Processing

miRNA microarray of MSCs was performed using the LC Sciences microarray platform (LC Sciences) as described previously.28 Detectable signals with average intensity three times higher than background SD and coefficient of variation (SD/average intensity) less than 0.5 were included in further analysis. For the Cy3 and Cy5 images, the signal intensity increased from 1 to 65,535. The miRNA with signal intensity > 32 was considered as detectable and with signal intensity > 500 was considered as highly expressed by the system. The data of three independent experiments were used for t test.

let-7a Mimics and Inhibitor Transfection

let-7a mimics, inhibitor, negative mimic control and negative inhibitor control were purchased from RiboBio. MSCs were cultured in culture dish to 70%–80% confluence. let-7a mimics, inhibitor, or negative control was transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) at final concentration of 150 nM, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In cellular experiments, negative mimic control and negative inhibitor control were mixed and transfected into the control group. In animal experiments, only negative inhibitor control was used as the control of let-7a inhibitor. Transfected MSCs were used for the following experiments or analysis 48 hr after transfection.

Luciferase Reporter Assay of miRNA Target

Luciferase reporter assay was performed as reported previously.28 In brief, FasL oligonucleotide sequences were amplified using the primers (forward: 5′-ATTGGCACCATCTTTACTTACC-3′, reverse: 5′-CTCCTTAGAATCTGCTCTCATA-3′) with SpeIand HindIII sites at their ends to insert into pMIR-Report vector (Firefly-luc) (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Fas oligonucleotide sequences were amplified using the primers (forward: 5′-TTCCCATCCTCCTGACCAC-3′; reverse: 5′-CTCGTAAACCGCTTCCCTC-3′). MSCs were seeded in 96-well plates to 70%–80% confluence. The pMIR-control, pMIR-Fas, and pMIR-FasL plasmids were used as reporter constructs, and a Renilla luciferase reporter without miRNA binding sites was used as the loading control. All plasmids were co-transfected into MSCs with let-7a mimics, inhibitor, or negative control, respectively. After 48 hr, Firefly-luc (F-luc) and Renilla luciferase (R-luc) activities in cell lysates were determined using a dual-luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega) following the manufacturers’ recommended protocols. The relative reporter activity of F-luc was normalized by R-luc activity.

ELISA

Supernatants of MSCs culture were collected 48 hr after let-7a mimics and inhibitor transfection. MCP-1 levels in the supernatants were measured using an ELISA kit (Beyotime), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

T Cell Migration Assay

A Transwell system (Corning) was used to detect T cell migration. The pore diameter of the upper chamber was 8 μm. MSCs (2 × 105) were stained with PKH (5 μM) (Sigma-Aldrich) and seeded on the lower chamber of a 12-well culture plate for 24 hr. Spleen cells were pre-stimulated with anti-CD3 (3 μg/mL) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-CD28 (1 μg/mL) (eBioscience) antibodies for 48 hr. CD3+ T cells were sorted by flow cytometry (BD) and stained with Hoechst-33342 (5 μg/mL) for 30 min. A total of 1 × 105 labeled T cells were seeded on the upper chamber of the Transwell system. Forty-eight hours after co-culture, T cells passing through the upper chamber were observed and counted under a fluorescent microscope (Olympus Optical).

Co-Culture of T Cells with MSCs

MSCs (2 × 105) were seeded on 6-well culture plates and incubated for 24 hr. Allogeneic T cells derived from spleen or MLN were activated by pre-stimulating with anti-CD3 (3 μg/mL) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-CD28 (1 μg/mL) (eBioscience) for 48 hr. Activated T cells (2 × 106) were then added into MSCs culture plate and co-cultured for 48 hr.

Apoptosis Analysis

To detect T cell apoptosis in the colitis model, the cell suspension collected by crashing the spleen or MLN was stained with CD3 antibody (1:1000) (BD Pharmingen) for 30 min, and then stained with Annexin V/PI following standard instruction of the Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Pharmingen). FCM was performed to analysis the apoptosis of CD3+ T cell. Apoptotic T cells were marked as CD3+/Annexin+/PI−.

To detect T cell apoptosis after co-culture with MSCs, the suspended cells in culture dishes were harvested by centrifugation. The cells were stained with CD3 antibody and Annexin V/PI following standard protocol. The apoptosis of CD3+ T cells were analyzed by FCM.

Cell Cycle Assay of T Cells

To detect the cell cycle of T cells in the experimental colitis model, lymphocytes isolated from mice spleen and MLN were stained with CD3 antibody (1:1000) (BD Pharmingen) for 30 min, and stained with a Cell Cycle Kit (BD Pharmingen) following the instruction. The cell cycle of CD3+ T cells was detected by FCM following the standard protocol.

To detect the cell cycle of T cells co-cultured with MSCs, the suspended cells harvested by centrifugation were stained with CD3 antibody (1:1000) for 30 min and with propidium iodide (BD Pharmingen). The cell cycle of CD3+ T cells was detected by FCM.

MSC Migration Assay

MSCs were labeled with 5 μg/mL of Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 hr before being injected into mice via tail vein. The mice were sacrificed 24 hr after MSC injection, and the internal organs were isolated immediately for analysis. In brief, the organs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hr, dehydrated with 10% sucrose solution for 24 hr, embedded in optimum cutting temperature compound (Sakura), and cut into 10-μm sections using a freezing microtome (Leica). The sections were examined under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus Optical) to detect Hoechst-labeled MSCs. The number of labeled cells on four consecutive microscopic fields was measured.

Fas and FasL siRNA Transfection

Fas siRNA, FasL siRNA, and control siRNA were purchased from Ruibo Company. siRNA transfection was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, MSCs were cultured in dishes to 70% confluence. Fas siRNA, FasL siRNA, or control siRNA were mixed with Lipofectamine 2000 and transfected into MSCs at the final concentration of 100 nM. The cells were harvested for further experiments after 48 hr.

To co-transfect Fas/FasL siRNA with let-7a mimic or inhibitor, 100 nM Fas/FasL siRNA and let-7a mimic, inhibitor, or negative control were mixed together and co-transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 into MSCs. MSCs were harvested for colitis therapy 48 hr after transfection.

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously.28 Primary antibodies of Fas (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), FasL (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and β-actin (Abcam) were used in the study. Blots on the membranes were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (BD Biosciences) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Gray value of the blots was measured using the IMAGEJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) following the instructions. The gray value of each target protein was normalized to that of β-actin before comparison.

MSC Treatment of Experimental Colitis

Inflammatory colitis was induced in mice (C57BL/6) by feeding with 3% DSS (MP Biomedicals) in water for 10 days.33 At day 3, MSCs (1 × 106) were injected into the colitis mice via tail vein. Mice infused with equal volume of PBS were used as the positive control of colitis.

Evaluation of Colitis

Mice were monitored daily for the occurrence of body weight change, diarrhea, fecal bleeding, and survival. Ten days later, the colon of each mouse was harvested and the length was recorded. For histopathological analysis, the colon segments were embedded, sectioned and stained with H&E for histological examination. Disease index and histologic score were assessed according to previously published criteria.56

MSC Treatment of Experimental GVHD

GVHD mouse model was induced according to previous report.57 In brief, recipient mice (BALB/c) were irradiated with 800 cGy and injected with 5 × 106 bone marrow cells and 5 × 106 spleen cells from donor mice (C57BL/6) via tail vein. Irradiated mice received only 5 × 106 T cell-depleted BM cells (TCD-BM) of C57BL/6 mice, which would not induce GVHD, were used as the negative control.

For MSC treatment, GVHD mice were injected with 1 × 106 MSCs (BALB/c) at the first and the fourth day after BMT. Mice injected with an equal volume of PBS were used as the GVHD positive control group.

GVHD Pathological Evaluation

To evaluate the development of GVHD, body weight and survival of mice after BMT were monitored daily. The degree of clinical GVHD was assessed using a scoring system that summed the changes in five clinical parameters: weight loss, posture, activity, fur texture, and skin integrity. For histopathological analysis of GVHD, the mice were sacrificed 25 days after bone marrow transplantation to collect the liver and colon. The tissue samples were fixed with 10% buffered formalin and stained with H&E. Histological changes were detected under a microscope and the histological scores were calculated. A scoring system was used according to a previous report.57

Statistical Analyses

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Comparisons were made using a one-way ANOVA. Body weight changes were compared by Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank test. Survival was analyzed by Kaplan-Meier log-rank test. A minimum of three replicates were analyzed for each experiment presented. The number of samples per group (n) was marked in figure legends. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Author Contributions

Y.Y. handled conception and design, collection and assembly of data, data analysis, and interpretation, and manuscript writing. L.L. handled conception and design, collection and assembly of data, data analysis, and interpretation, and manuscript writing. B.S. handled collection and assembly of data and data analysis and interpretation. X.S. handled collection and assembly of data, data analysis, and interpretation. Y.S. handled collection and assembly of data. H.W. handled collection and assembly of data. F.S. handled data analysis and interpretation. Z.Z. handled data analysis and interpretation. D.Y. handled conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, and administrative support. Y.J. handled conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, financial support, and financial approval of manuscript. Y.Y. and L.L. contributed equally to this article.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Nature Science Foundation of China Grants 31030033, 81470710, and 31601113 and National Major Scientific Research Program of China Grant 2011CB964700.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes five figures and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2016.11.015.

Contributor Information

Deqin Yang, Email: yangdeqin@gmail.com.

Yan Jin, Email: yanjin@fmmu.edu.cn.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Bianco P., Robey P.G., Simmons P.J. Mesenchymal stem cells: revisiting history, concepts, and assays. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gómez-Barrena E., Rosset P., Müller I., Giordano R., Bunu C., Layrolle P., Konttinen Y.T., Luyten F.P. Bone regeneration: stem cell therapies and clinical studies in orthopaedics and traumatology. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2011;15:1266–1286. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei C.C., Lin A.B., Hung S.C. Mesenchymal stem cells in regenerative medicine for musculoskeletal diseases: bench, bedside, and industry. Cell Transplant. 2014;23:505–512. doi: 10.3727/096368914X678328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaidi N., Nixon A.J. Stem cell therapy in bone repair and regeneration. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 2007;1117:62–72. doi: 10.1196/annals.1402.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolf D., Wolf A.M. Mesenchymal stem cells as cellular immunosuppressants. Lancet. 2008;371:1553–1554. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60666-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keating A. Mesenchymal stromal cells: new directions. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:709–716. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singer N.G., Caplan A.I. Mesenchymal stem cells: mechanisms of inflammation. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2011;6:457–478. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ankrum J., Karp J.M. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy: two steps forward, one step back. Trends Mol. Med. 2010;16:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Blanc K., Frassoni F., Ball L., Locatelli F., Roelofs H., Lewis I., Lanino E., Sundberg B., Bernardo M.E., Remberger M. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute graft-versus-host disease: a phase II study. Lancet. 2008;371:1579–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60690-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burt R.K., Loh Y., Pearce W., Beohar N., Barr W.G., Craig R., Wen Y., Rapp J.A., Kessler J. Clinical applications of blood-derived and marrow-derived stem cells for nonmalignant diseases. JAMA. 2008;299:925–936. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.8.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Syed B.A., Evans J.B. Stem cell therapy market. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013;12:185–186. doi: 10.1038/nrd3953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akiyama K., Chen C., Wang D., Xu X., Qu C., Yamaza T., Cai T., Chen W., Sun L., Shi S. Mesenchymal-stem-cell-induced immunoregulation involves FAS-ligand-/FAS-mediated T cell apoptosis. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:544–555. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy W.J., Nolta J.A. Autoimmune T cells lured to a FASL web of death by MSCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:485–487. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennea N.L., Stratou C., Naparus A., Fisk N.M., Mehmet H. Functional intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways in human fetal mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:1439–1441. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kota J., Chivukula R.R., O’Donnell K.A., Wentzel E.A., Montgomery C.L., Hwang H.W., Chang T.C., Vivekanandan P., Torbenson M., Clark K.R. Therapeutic microRNA delivery suppresses tumorigenesis in a murine liver cancer model. Cell. 2009;137:1005–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu S., Huang M., Li Z., Jia F., Ghosh Z., Lijkwan M.A., Fasanaro P., Sun N., Wang X., Martelli F. MicroRNA-210 as a novel therapy for treatment of ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 2010;122(11, Suppl):S124–S131. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.928424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu C., Kelnar K., Liu B., Chen X., Calhoun-Davis T., Li H., Patrawala L., Yan H., Jeter C., Honorio S. The microRNA miR-34a inhibits prostate cancer stem cells and metastasis by directly repressing CD44. Nat. Med. 2011;17:211–215. doi: 10.1038/nm.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lanford R.E., Hildebrandt-Eriksen E.S., Petri A., Persson R., Lindow M., Munk M.E. Therapeutic silencing of microRNA-122 in primates with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Science. 2010;327:198–201. doi: 10.1126/science.1178178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartel D.P. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartel D.P. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mendell J.T., Olson E.N. MicroRNAs in stress signaling and human disease. Cell. 2012;148:1172–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutvágner G., Simard M.J., Mello C.C., Zamore P.D. Sequence-specific inhibition of small RNA function. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E98. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elmén J., Lindow M., Schütz S., Lawrence M., Petri A., Obad S., Lindholm M., Hedtjärn M., Hansen H.F., Berger U. LNA-mediated microRNA silencing in non-human primates. Nature. 2008;452:896–899. doi: 10.1038/nature06783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y., Fan L., Liu S., Liu W., Zhang H., Zhou T., Wu D., Yang P., Shen L., Chen J., Jin Y. The promotion of bone regeneration through positive regulation of angiogenic-osteogenic coupling using microRNA-26a. Biomaterials. 2013;34:5048–5058. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajewsky N. microRNA target predictions in animals. Nat. Genet. 2006;38(Suppl):S8–S13. doi: 10.1038/ng1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedman R.C., Farh K.K., Burge C.B., Bartel D.P. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Betel D., Wilson M., Gabow A., Marks D.S., Sander C. The microRNA.org resource: targets and expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D149–D153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liao L., Yang X., Su X., Hu C., Zhu X., Yang N., Chen X., Shi S., Shi S., Jin Y. Redundant miR-3077-5p and miR-705 mediate the shift of mesenchymal stem cell lineage commitment to adipocyte in osteoporosis bone marrow. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e600. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geng L., Zhu B., Dai B.H., Sui C.J., Xu F., Kan T., Shen W.F., Yang J.M. A let-7/Fas double-negative feedback loop regulates human colon carcinoma cells sensitivity to Fas-related apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;408:494–499. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang S., Tang Y., Cui H., Zhao X., Luo X., Pan W., Huang X., Shen N. Let-7/miR-98 regulate Fas and Fas-mediated apoptosis. Genes Immun. 2011;12:149–154. doi: 10.1038/gene.2010.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’ Reilly L.A., Tai L., Lee L., Kruse E.A., Grabow S., Fairlie W.D., Haynes N.M., Tarlinton D.M., Zhang J.G., Belz G.T. Membrane-bound Fas ligand only is essential for Fas-induced apoptosis. Nature. 2009;461:659–663. doi: 10.1038/nature08402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi Y., Hu G., Su J., Li W., Chen Q., Shou P., Xu C., Chen X., Huang Y., Zhu Z. Mesenchymal stem cells: a new strategy for immunosuppression and tissue repair. Cell Res. 2010;20:510–518. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okayasu I., Hatakeyama S., Yamada M., Ohkusa T., Inagaki Y., Nakaya R. A novel method in the induction of reliable experimental acute and chronic ulcerative colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:694–702. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90290-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren G., Zhang L., Zhao X., Xu G., Zhang Y., Roberts A.I., Zhao R.C., Shi Y. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression occurs via concerted action of chemokines and nitric oxide. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hendrickson D.G., Hogan D.J., McCullough H.L., Myers J.W., Herschlag D., Ferrell J.E., Brown P.O. Concordant regulation of translation and mRNA abundance for hundreds of targets of a human microRNA. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garzon R., Marcucci G., Croce C.M. Targeting microRNAs in cancer: rationale, strategies and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:775–789. doi: 10.1038/nrd3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costello E., Greenhalf W., Neoptolemos J.P. New biomarkers and targets in pancreatic cancer and their application to treatment. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;9:435–444. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu S., Huang M., Nguyen P.K., Gong Y., Li Z., Jia F., Lan F., Liu J., Nag D., Robbins R.C., Wu J.C. Novel microRNA prosurvival cocktail for improving engraftment and function of cardiac progenitor cell transplantation. Circulation. 2011;124(11, Suppl):S27–S34. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.017954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kovacić N., Lukić I.K., Grcević D., Katavić V., Croucher P., Marusić A. The Fas/Fas ligand system inhibits differentiation of murine osteoblasts but has a limited role in osteoblast and osteoclast apoptosis. J. Immunol. 2007;178:3379–3389. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Büssing I., Slack F.J., Grosshans H. let-7 microRNAs in development, stem cells and cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 2008;14:400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Toledano H., D’Alterio C., Czech B., Levine E., Jones D.L. The let-7-Imp axis regulates ageing of the Drosophila testis stem-cell niche. Nature. 2012;485:605–610. doi: 10.1038/nature11061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roush S., Slack F.J. The let-7 family of microRNAs. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wan Z., Zhi N., Wong S., Keyvanfar K., Liu D., Raghavachari N., Munson P.J., Su S., Malide D., Kajigaya S., Young N.S. Human parvovirus B19 causes cell cycle arrest of human erythroid progenitors via deregulation of the E2F family of transcription factors. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:3530–3544. doi: 10.1172/JCI41805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cha S.T., Tan C.T., Chang C.C., Chu C.Y., Lee W.J., Lin B.Z., Lin M.T., Kuo M.L. G9a/RelB regulates self-renewal and function of colon-cancer-initiating cells by silencing Let-7b and activating the K-RAS/β-catenin pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18:993–1005. doi: 10.1038/ncb3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park S.B., Seo K.W., So A.Y., Seo M.S., Yu K.R., Kang S.K., Kang K.S. SOX2 has a crucial role in the lineage determination and proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells through Dickkopf-1 and c-MYC. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:534–545. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reinhart B.J., Slack F.J., Basson M., Pasquinelli A.E., Bettinger J.C., Rougvie A.E., Horvitz H.R., Ruvkun G. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2000;403:901–906. doi: 10.1038/35002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ikeda K., Mason P.J., Bessler M. 3’UTR-truncated Hmga2 cDNA causes MPN-like hematopoiesis by conferring a clonal growth advantage at the level of HSC in mice. Blood. 2011;117:5860–5869. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-334425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu F., Yao H., Zhu P., Zhang X., Pan Q., Gong C., Huang Y., Hu X., Su F., Lieberman J., Song E. let-7 regulates self renewal and tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells. Cell. 2007;131:1109–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dubinsky A.N., Dastidar S.G., Hsu C.L., Zahra R., Djakovic S.N., Duarte S., Esau C.C., Spencer B., Ashe T.D., Fischer K.M. Let-7 coordinately suppresses components of the amino acid sensing pathway to repress mTORC1 and induce autophagy. Cell Metab. 2014;20:626–638. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dang S., Xu H., Xu C., Cai W., Li Q., Cheng Y., Jin M., Wang R.X., Peng Y., Zhang Y. Autophagy regulates the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Autophagy. 2014;10:1301–1315. doi: 10.4161/auto.28771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perruche S., Zhang P., Liu Y., Saas P., Bluestone J.A., Chen W. CD3-specific antibody-induced immune tolerance involves transforming growth factor-beta from phagocytes digesting apoptotic T cells. Nat. Med. 2008;14:528–535. doi: 10.1038/nm1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park M.J., Park H.S., Cho M.L., Oh H.J., Cho Y.G., Min S.Y., Chung B.H., Lee J.W., Kim H.Y., Cho S.G. Transforming growth factor β-transduced mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate experimental autoimmune arthritis through reciprocal regulation of Treg/Th17 cells and osteoclastogenesis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:1668–1680. doi: 10.1002/art.30326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mei S.H., McCarter S.D., Deng Y., Parker C.H., Liles W.C., Stewart D.J. Prevention of LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice by mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing angiopoietin 1. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li W., Ma N., Ong L.L., Nesselmann C., Klopsch C., Ladilov Y., Furlani D., Piechaczek C., Moebius J.M., Lützow K. Bcl-2 engineered MSCs inhibited apoptosis and improved heart function. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2118–2127. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shuai Y., Liao L., Su X., Yu Y., Shao B., Jing H., Zhang X., Deng Z., Jin Y. Melatonin treatment improves mesenchymal stem cells therapy by preserving stemness during long-term in vitro expansion. Theranostics. 2016;6:1899–1917. doi: 10.7150/thno.15412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naito Y., Takagi T., Kuroda M., Katada K., Ichikawa H., Kokura S., Yoshida N., Okanoue T., Yoshikawa T. An orally active matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor, ONO-4817, reduces dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice. Inflamm. Res. 2004;53:462–468. doi: 10.1007/s00011-004-1281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lim J.Y., Park M.J., Im K.I., Kim N., Jeon E.J., Kim E.J., Cho M.L., Cho S.G. Combination cell therapy using mesenchymal stem cells and regulatory T-cells provides a synergistic immunomodulatory effect associated with reciprocal regulation of TH1/TH2 and th17/treg cells in a murine acute graft-versus-host disease model. Cell Transplant. 2014;23:703–714. doi: 10.3727/096368913X664577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.