Abstract

Background

The fate of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) has been inferred indirectly from the activity of ER-localized thiol oxidases and peroxiredoxins, in vitro, and the consequences of their genetic manipulation, in vivo. Over the years hints have suggested that glutathione, puzzlingly abundant in the ER lumen, might have a role in reducing the heavy burden of H2O2 produced by the luminal enzymatic machinery for disulfide bond formation. However, limitations in existing organelle-targeted H2O2 probes have rendered them inert in the thiol-oxidizing ER, precluding experimental follow-up of glutathione’s role in ER H2O2 metabolism.

Results

Here we report on the development of TriPer, a vital optical probe sensitive to changes in the concentration of H2O2 in the thiol-oxidizing environment of the ER. Consistent with the hypothesized contribution of oxidative protein folding to H2O2 production, ER-localized TriPer detected an increase in the luminal H2O2 signal upon induction of pro-insulin (a disulfide-bonded protein of pancreatic β-cells), which was attenuated by the ectopic expression of catalase in the ER lumen. Interfering with glutathione production in the cytosol by buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) or enhancing its localized destruction by expression of the glutathione-degrading enzyme ChaC1 in the lumen of the ER further enhanced the luminal H2O2 signal and eroded β-cell viability.

Conclusions

A tri-cysteine system with a single peroxidatic thiol enables H2O2 detection in oxidizing milieux such as that of the ER. Tracking ER H2O2 in live pancreatic β-cells points to a role for glutathione in H2O2 turnover.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12915-017-0367-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Endoplasmic reticulum, Redox, H2O2 probe, Hydrogen peroxide, Glutathione, Fluorescent protein sensor, Fluorescence lifetime imaging, Live cell imaging, Pancreatic β-cells

Background

The thiol redox environment of cells is compartmentalized, with disulfide bond formation confined to the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondrial inter-membrane space in eukaryotes and the periplasmic space in bacteria and largely excluded from the reducing cytosol [1]. Together, the tripeptide glutathione and its proteinaceous counterpart, thioredoxin, contribute to a chemical environment that maintains most cytosolic thiols in their reduced state. The enzymatic machinery for glutathione synthesis, turnover, and reduction is localized to the cytosol, as is the thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase couple [2]. However, unlike the thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase system that is largely isolated from the ER, several lines of evidence suggest equilibration of glutathione pools between the cytosol and ER.

Isolated microsomes contain millimolar concentrations of glutathione [3], an estimate buttressed by kinetic measurements [4]. Yeast genetics reveals that the kinetic defect in ER disulfide bond formation wrought by lack of an important luminal thiol oxidase, ERO1, can be ameliorated by attenuated glutathione synthesis in the cytosol [5], whereas deregulated import of glutathione across the plasma membrane into the cytosol compromises oxidative protein folding in the yeast ER [6]. Import of reduced glutathione into the isolated rat liver microsomal fraction has been observed [7], and in a functional counterpart to these experiments, excessive reduced glutathione on the cytosolic side of the plant cell ER membrane compromised disulfide formation [8]. In mammalian cells, experimental mislocalization of the reduced glutathione-degrading enzyme ChaC1 to the ER depleted total cellular pools of glutathione [9], arguing for transport of glutathione from its site of synthesis in the cytosol to the ER. Despite firm evidence for the existence of a pool of reduced glutathione in the ER, its functional role has remained obscure, as depleting ER glutathione in cultured fibroblasts affected neither disulfide bond formation nor their reductive reshuffling [9].

The ER is an important source of hydrogen peroxide production. This is partially explained by the activity of ERO1, which shuttles electrons from reduced thiols to molecular oxygen, converting the latter to hydrogen peroxide [10]. Alternative ERO1-independent mechanisms for luminal hydrogen peroxide production also exist [11], yet the fate of this locally generated hydrogen peroxide is not entirely clear. Some is utilized for disulfide bond formation, a process that relies on the ER-localized peroxiredoxin 4 (PRDX4) [12, 13] and possibly other enzymes that function as peroxiredoxins [14, 15]. However, under conditions of hydrogen peroxide hyperproduction (experimentally induced by a deregulated mutation in ERO1), the peroxiredoxins that exploit the pool of reduced protein thiols in the ER lumen as electron donors are unable to cope with the excess of hydrogen peroxide, and cells expressing the hyperactive ERO1 are rendered hypersensitive to concomitant depletion of reduced glutathione [16]. Besides, ERO1 overexpression leads to an increase in cell glutathione content [17]. These findings suggest a role for reduced glutathione in buffering excessive ER hydrogen peroxide production. Unfortunately, limitations in methods for measuring changes in the content of ER luminal hydrogen peroxide have frustrated efforts to pursue this hypothesis.

Here we describe the development of an optical method to track changes in hydrogen peroxide levels in the ER lumen. Its application to the study of cells in which the levels of hydrogen peroxide and glutathione were selectively manipulated in the ER and cytosol revealed an important role for glutathione in buffering the consequences of excessive ER hydrogen peroxide production. This process appears especially important to insulin-producing β-cells that are encumbered by a heavy burden of ER hydrogen peroxide production and a deficiency of the peroxide-degrading calatase.

Results

Glutathione depletion exposes the hypersensitivity of pancreatic β-cells to hydrogen peroxide

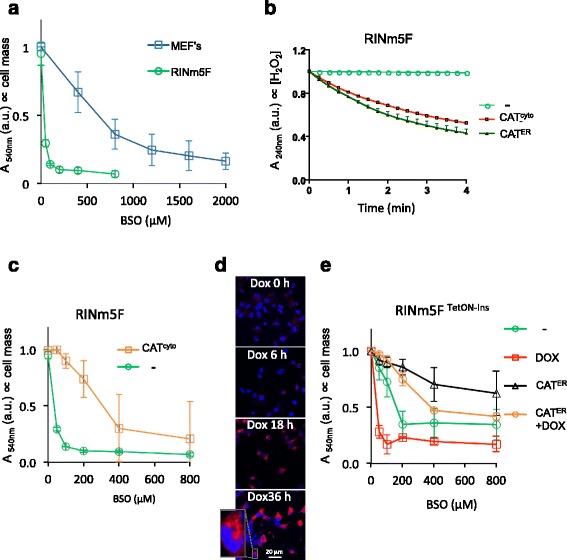

Insulin-producing pancreatic β-cells are relatively deficient in the hydrogen peroxide-degrading enzymes catalase and GPx1 [18, 19] and are thus deemed a sensitized experimental system to pursue the hypothesized role of glutathione in ER hydrogen peroxide metabolism. Compared with fibroblasts, insulin-producing RINm5F cells (a model for pancreatic β-cells) were noted to be hypersensitive to inhibition of glutathione biosynthesis by buthionine sulfoximine (BSO, Fig. 1a and Additional file 1: Figure S1). Cytosolic catalase expression reversed this hypersensitivity to BSO (Fig. 1b, c).

Fig. 1.

Glutathione depletion sensitizes pancreatic β-cells to endogenous H2O2. a Absorbance at 540 nm (an indicator of cell mass) by cultures of a β-cell line (RINm5F) or mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs, a reference) that had been exposed to the indicated concentration of buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) before fixation and staining with crystal violet. b Plot of in vitro catalase activity, reflected in time-dependent decline in absorbance (A 240 nm) of H2O2 solution, exposed to lysates of untransfected RINm5F cells (-) or cells stably transfected with plasmids encoding cytoplasmic (CAT cyto) or ER-localized catalase (CAT ER). c As in (a), comparing untransfected RINm5F cells (-) or cells stably expressing cytosolic catalase (CAT cyto). d Fluorescent photomicrographs of RINm5F cells stably expressing a tetracycline inducible human pro-insulin gene (RINm5FTetON-Ins) fixed at the indicated time points post doxycycline (20 ng/ml) exposure and immunostained for total insulin (red channel); Hoechst 33258 was used to visualize cell nuclei (blue channel). e As in (a), comparing cell mass of uninduced and doxycycline-induced RINm5FTetON-Ins cells that had or had not been transfected with an expression plasmid encoding ER catalase (CAT ER). Shown are mean +/– standard error of the mean (SEM), n ≥ 3

Induction of pro-insulin biosynthesis via a tetracycline inducible promoter (Fig. 1d), which burdens the ER with disulfide bond formation and promotes the associated production of hydrogen peroxide, contributed to the injurious effects of BSO. But these were partially reversed by the presence of ER-localized catalase (Fig. 1e). The protective effect of ER-localized catalase is likely to reflect the enzymatic degradation of locally produced hydrogen peroxide, as hydrogen peroxide is slow to equilibrate between the cytosol and ER [11]. Together these findings hint at a role for glutathione in buffering the consequences of excessive production of hydrogen peroxide in the ER of pancreatic β-cells.

A probe adapted to detect H2O2 in thiol-oxidizing environments

To further explore the role of glutathione in the metabolism of ER hydrogen peroxide, we sought to measure the effects of manipulating glutathione availability on the changing levels of ER hydrogen peroxide. Exemplified by HyPer [20], genetically encoded optical probes responsive to changing levels of hydrogen peroxide have been developed and, via targeted localization, applied to the cytosol, peroxisome, and mitochondrial matrix [20–23]. Unfortunately, in the thiol-oxidizing environment of the ER, the optically sensitive disulfide in HyPer (that reports on the balance between hydrogen peroxide and contravening cellular reductive processes) instead forms via oxidized members of the protein disulfide isomerase family (PDIs), depleting the pool of reduced HyPer that can sense hydrogen peroxide [11, 24].

To circumvent this limitation, we sought to develop a probe that would retain responsiveness to hydrogen peroxide in the presence of a high concentration of oxidized PDI. HyPer consists of a circularly permuted yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) grafted with the hydrogen peroxide-sensing portion of the bacterial transcription factor OxyR [20, 25]. It possesses two reactive cysteines: a peroxidatic cysteine (OxyR C199) that reacts with H2O2 to form a sulfenic acid and a resolving cysteine (OxyR C208) that attacks the sulfenic acid to form the optically distinct disulfide. We speculated that introduction of a third cysteine, vicinal to the resolving C208, might permit a rearrangement of the disulfide bonding pattern that could preserve a fraction of the peroxidatic cysteine in its reduced form and thereby preserve a measure of H2O2 responsiveness, even in the thiol-oxidizing environment of the ER.

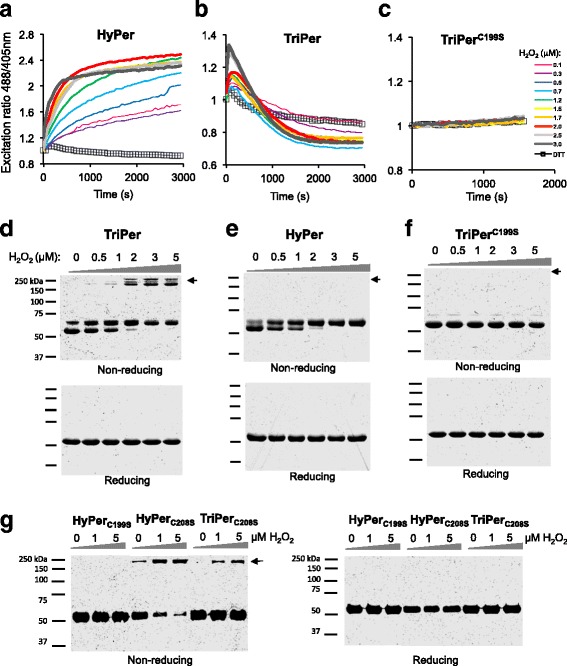

Replacement of OxyR alanine 187 (located ~6 Å from the resolving cysteine 208 in PDB1I69) with cysteine gave rise to a tri-cysteine probe, TriPer, that retained responsiveness to H2O2 in vitro but with an optical readout that was profoundly different from that of HyPer: While reduced HyPer exhibits a monotonic H2O2 and time-dependent increase in its excitability at 488 nm compared to 405 nm (R488/405, Fig. 2a), in response to H2O2, the R488/405 of reduced TriPer increased transiently before settling into a new steady state (Fig. 2b). TriPer’s optical response to H2O2 was dependent on the peroxidatic cysteine (C199), as its replacement by serine eliminated all responsiveness (Fig. 2c). R266 supports the peroxidatic properties of OxyR’s C199, likely by de-protonation of the reactive thiol [25]. The R266A mutation similarly abolished H2O2 responsiveness of HyPer and TriPer, indicating a shared catalytic mechanism for OxyR and the two derivative probes (Additional file 2: Figure S2A).

Fig. 2.

TriPer’s responsiveness to H2O2 in vitro. a–c Traces of time-dependent changes to the redox-sensitive excitation ratio of HyPer (a), TriPer (b), or the TriPer mutant lacking its peroxidatic cysteine (TriPer C199S) (c) in response to increasing concentrations of H2O2 or the reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT). d–g Non-reducing and reducing SDS-PAGE of recombinant TriPer (d), HyPer (e), a TriPer mutant lacking its peroxidatic cysteine (TriPer C199S) (f), and HyPerC199S along HyPer/TriPer lacking their resolving cysteine (HyPer C208S/TriPer C208S) (g) performed following the incubation in vitro with increasing concentrations of H2O2 for 15 min, black arrow denotes the high molecular weight species, exclusive to TriPer and to HyPer/TriPer lacking their resolving cysteine (HyPerC208S/TriPerC208S), emerging as a result of H2O2 induced dithiol(s) formation in trans. Shown are representatives of n ≥ 3

The optical response to H2O2 of TriPer correlated in a dose- and time-dependent manner with formation of high molecular weight disulfide-bonded species, detectable on non-reducing SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2d and Additional file 3: Figure S3A). These species were not observed in H2O2-exposed HyPer, and their presence in TriPer depended on both the peroxidatic C199 and on R266 (Fig. 2e, f and Additional file 2: Figure S2B). Furthermore, H2O2 promoted such mixed disulfides in probe variants missing the resolving C208 or both C208 and the TriPer-specific C187 (Fig. 2g). The high molecular weight TriPer species induced by H2O2 migrate anomalously on standard SDS-PAGE. However, on neutral pH gradient SDS-PAGE their size is consistent with that of a dimer (Additional file 2: Figure S2C), while their formation was not accompanied by changes in R488/405 in mutants lacking the ability to form C208-C199 disulfide (Additional file 2: Figure S2D).

The observations above indicate that, in the absence of C208, H2O2 induced C199 sulfenic intermediates are resolved in trans and suggest that formation of the divergent C208-C187 pair, unique to TriPer, favors this alternative route. To test this prediction we traced the R488/405 of TriPer under conditions mimicking the oxidizing environment of the ER. TriPer’s time-dependent biphasic optical response (R488/405) to H2O2 contrasted with the hyperbolic profile of its response to diamide- or PDI-mediated oxidation (Fig. 3a). The latter is by far the most abundant ER thiol-oxidizing enzyme. PDI-catalyzed HyPer oxidation likewise had a hyperbolic profile but with a noticeably higher R488/405 plateau (Fig. 3a). However, whereas TriPer retained responsiveness to H2O2, even from its PDI-oxidized plateau, PDI-oxidized HyPer lost all sensitivity to H2O2 (Fig. 3b). Unlike H2O2, PDI did not promote formation of the disulfide-bonded high molecular weight TriPer species (Additional file 3: Figure S3A, B).

Fig. 3.

TriPer’s responsiveness to H2O2 in a thiol-oxidizing environment. a Traces of time-dependent changes to the excitation ratio of HyPer (orange squares), TriPer (blue spheres), and TriPer mutant lacking its peroxidatic cysteine (TriPer C199S, black diamonds) following the introduction of oxidized PDI (8 μM, empty squares, spheres, and diamonds) or diamide (general oxidant, 2 mM, filled squares and spheres). b Ratiometric traces (as in a) of HyPer and TriPer sequentially exposed to oxidized PDI (8 μM) and H2O2 (2 μM). c Ratiometric traces (as in a) of HyPer or TriPer exposed to H2O2 (4 μM) followed by DTT (2.6 mM). The excitation spectra of the reaction phases (1–4) are analyzed in Additional file 3: Figure S3C. d Schema of TriPer oxidation pathway. Oxidants drive the formation of the optically distinct (high R488/405) CP199-CR208 (CPeroxidatic, CResolving) disulfide, which re-equilibrates with an optically inert (low R488/405) CD187-CR208 (CDivergent, CResolving) disulfide in a redox relay [44–46] imposed by the three-cysteine system. The pool of TriPer with a reduced peroxidatic CP199 thus generated is available to react with H2O2, forming a sulfenic intermediate. Resolution of this intermediate in trans shifts TriPer to a new, optically indistinct low R488/405 state, depleting the original optically distinct (high R488/405) intermolecular disulfide CP199-CR208. This accounts for the biphasic response of TriPer to H2O2 (Fig. 2b) and for its residual responsiveness to H2O2 after oxidation by PDI (b of this figure)

H2O2-driven formation of the optically active C199-C208 disulfide in HyPer enjoys a considerable kinetic advantage over its reduction by dithiothreitol (DTT) [11]. This was reflected here in the high R488/405 of the residual plateau of HyPer co-exposed to H2O2 and DTT (Fig. 3c). Thus, HyPer and TriPer traces converge at a high ratio point in the presence of H2O2 and DTT (Fig. 3c and Additional file 3: Figure S3C), a convergence that requires both C199 and C208 (Additional file 2: Figure S2D). In these conditions DTT releases TriPer’s C208 from the divergent disulfide, allowing it to resolve C199-sulfenic in cis, thus confirming C199-C208 as the only optically distinct (high R488/405) disulfide. It is worth noting that the convergence of TriPer and HyPer traces in these conditions confirms that in both probes C199-C208 corresponds to the sole high ratio state, consistent with the lack of optical response in all monomeric/dimeric configurations (Additional file 2: Figure S2). Thus, TriPer’s biphasic response to H2O2, which is preserved in the face of PDI-driven oxidation (a mimic of conditions in the ER), emerges from the competing H2O2-driven formation of a trans-disulfide, imparting a low R488/405 (Fig. 3d).

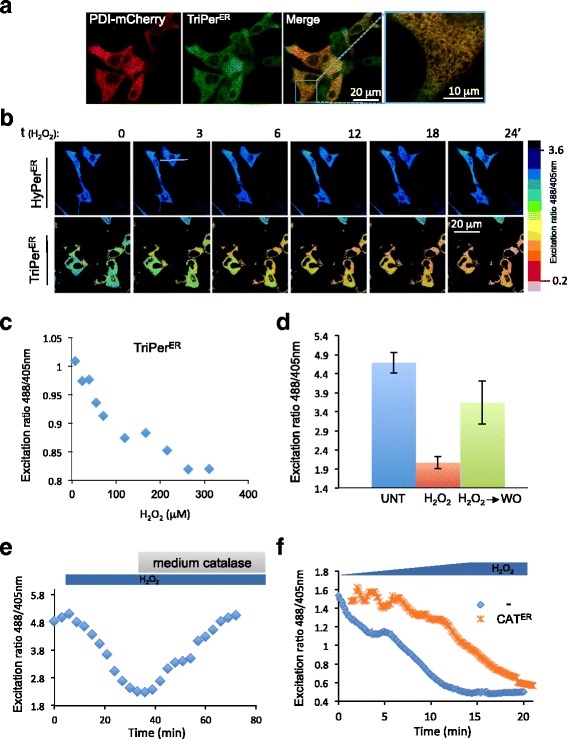

TriPer detects H2O2 in the oxidizing ER environment

To test if the promising features of TriPer observed in vitro enable H2O2 sensing in the ER, we tagged TriPer with a signal peptide and confirmed its ER localization in transfected cells (Fig. 4a). Unlike ER-localized HyPer, whose optical properties remained unchanged in cells exposed to H2O2, ER-localized TriPer responded with a H2O2 concentration-dependent decline in the R488/405 (Fig. 4b, c).

Fig. 4.

ER-localized TriPer responds optically to exogenous H2O2. a Fluorescent photomicrographs of live COS7 cells, co-expressing TriPerER and PDI-mCherry as an ER marker. b Time course of in vivo fluorescence excitation (488/405 nm) ratiometric images (R488/405) of HyPerER or TriPerER from cells exposed to H2O2 (0.2 mM) for the indicated time. The excitation ratio in the images was color coded according to the map shown. c Plot showing the dependence of in vivo fluorescence excitation (488/405 nm) ratio of TriPerER on H2O2 concentration in the culture medium. d Bar diagram of excitation ratio of TriPerER from untreated (UNT) cells, cells exposed to H2O2 (0.2 mM, 15 min), or cells 15 min after washout (H 2 O 2 ➔WO) (mean ± SEM, n = 12). e A ratiometric trace of TriPerER expressed in RINm5F cells exposed to H2O2 (0.2 mM) followed by bovine catalase for the indicated duration. f A ratiometric trace of TriPerER expressed alone or alongside ER catalase (CAT ER) in RINm5F cells exposed to increasing concentrations of H2O2 (0–0.2 mM). Shown are representatives of n ≥ 3

The H2O2-mediated changes in the optical properties of ER-localized TriPer were readily reversed by washout or by introducing catalase into the culture media, which rapidly eliminated the H2O2 (Fig. 4d, e). Both the slow rate of diffusion of H2O2 into the ER (Konno et al., 2015 [11]) and the inherent delay imposed by the two-step process entailed in TriPer’s responsiveness to H2O2 (Fig. 3) contribute to the sluggish temporal profile of the changes observed in TriPer’s optical properties in cells exposed to H2O2. Further evidence that TriPer was indeed responding to changing H2O2 content of the ER was provided by the attenuated and delayed response to exogenous H2O2 observed in cells expressing an ER-localized catalase (Fig. 4f).

The response of TriPer to H2O2 could be tracked not only by following the changes in its excitation properties (as revealed in the R488/405) but also by monitoring the fluorophore’s fluorescence lifetime using fluorescent lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) (as previously observed for other disulfide-based optical probes [26, 27]).

Exposure of cells expressing ER TriPer to H2O2 resulted in highly reproducible increases in the fluorophore’s fluorescence lifetime (with a dynamic range >8 X SD, Fig. 5a). HyPer’s fluorescence lifetime was also responsive to H2O2, but only in the reducing environment of the cytoplasm (Fig. 5b); the lifetime of ER-localized HyPer remained unchanged in cells exposed to H2O2 (Fig. 5c). These findings are consistent with nearly complete oxidation of the C199-C208 disulfide under basal conditions in ER-localized HyPer and highlight the residual H2O2 responsiveness of ER-localized TriPer (Fig. 5d) [11, 24].

Fig. 5.

Fluorescence lifetime reports on the redox status of HyPer and TriPer. a–c Fluorescence intensity-based (in grayscale) and lifetime images (color-coded to the scale of the histogram on the right) of RINm5F cells expressing TriPerER (a), HyPercyto (b), or HyPerER before and after exposure to H2O2 (0.2 mM, 15 min) (c). A histogram of the distribution of lifetimes in the population of cells is provided (right). d Bar diagram of the fluorescence lifetime peak values from (a–c, mean ± SD, ***p < 0.005, n ≥ 10)

Both ratiometry and FLIM trace alterations in the fluorophore resulting from C199-C208 formation. However, FLIM has important advantages over ratiometric measurements of changes in probe excitation, especially when applied to cell imaging: It is a photophysical property of the probe that is relatively independent of the ascertainment platform and indifferent to photobleaching. Therefore, although ratiometric imaging is practical for short-term tracking of single cells, FLIM is preferable when populations of cells exposed to divergent conditions are compared. Under basal conditions, ER-localized TriPer’s lifetime indicated that it is found in a redox state where the C199-C208 pair is nearly half-oxidized (Fig. 5d), resembling that of PDI-exposed TriPer in vitro (Fig. 3a) and validating the use of FLIM to trace TriPer’s response to H2O2 in vivo.

Glutathione depletion leads to H2O2 elevation in the ER of pancreatic cells

Exploiting the responsiveness of ER-localized TriPer to H2O2, we set out to measure the effect of glutathione depletion on the ER H2O2 signal as reflected in differences in ER TriPer’s fluorescence lifetime. BSO treatment of RINm5F cells increased the fluorescence lifetime of ER TriPer from 1490 +/– 43 ps at steady state to 1673 +/– 64 ps (Fig. 6a). A corresponding trend was also observed by measuring the changes in ER TriPer’s excitation properties ratiometrically (Additional file 4: Figure S4A).

Fig. 6.

ER H2O2 increases in glutathione-depleted cells. a Bar diagram of fluorescence lifetime (FLT) of TriPerER expressed in the presence or absence of ER catalase (CAT ER) in RINm5F cells containing a tetracycline inducible pro-insulin gene. Where indicated pro-insulin expression was induced by doxycycline (DOX 20 ng/ml) and the cells were exposed to 0.3 mM BSO (18 h). b As in a, but TriPerER-expressing cells were exposed to 0.15 mM BSO (18 h). c A trace of time-dependent changes in HyPercyto or TriPerER FLT in RINm5F cells after exposure to 0.2 mM BSO. Each data point represents the mean ± SD of fluorescence lifetime measured in ≥20 cells. The ordinate of HyPercyto FLT was inverted to harmonize the trendlines of the two probes. d Bar diagram of FLT of ERroGFPiE, expressed in cells, untreated or exposed to 2 mM DTT, the oxidizing agent 2,2′-dipyridyl disulfide (DPS), or 0.3 mM BSO (18 h). e Bar diagram of FLT of an H2O2-unresponsive TriPer mutant (TriPerR266G) expressed in the ER of untreated or BSO-treated cells (0.3 mM; 18 h). f Bar diagram of FLT of TriPerER expressed in the presence or absence of ER catalase or an ER-localized glutathione-degrading enzyme (WT ChaC1 ER) or its enzymatically inactive E116Q mutant version (Mut ChaC1 ER). Shown are mean values ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, n ≥ 20)

Induction of pro-insulin biosynthesis accentuated TriPer’s response to BSO (Fig. 6a, compare samples 5 and 7), whereas expression of ER catalase counteracted the BSO-induced increase of TriPer’s fluorescence lifetime, both under baseline conditions and following stimulation of pro-insulin production in RINm5FTtetON-Ins cells (Fig. 6a, compare samples 5 and 6, and 7 and 8; Fig. 6b, compare samples 2 and 3). These observations correlate well with the cytoprotective effect of ER catalase in RINm5F cells exposed to BSO (Fig. 1). It is noteworthy that the increase in ER H2O2 signal in BSO-treated cells was observed well before the increase in the cytosolic H2O2 signal (Fig. 6c) and also preceded death of the glutathione-depleted cells (Additional file 4: Figure S4B).

The ability of ER catalase to attenuate the optical response of ER-localized TriPer to BSO or pro-insulin induction argues for an increase in ER H2O2 as the underlying event triggering the optical response. Two further findings support this conclusion: (1) The disulfide state of the ER-tuned redox reporter ERroGFPiE [26, 28, 29] remained unaffected by BSO. This argues against the possibility that the observed TriPer response is a consequence of a more reducing ER thiol redox poise induced by glutathione depletion (Fig. 6d). (2) TriPer’s responsiveness to BSO and pro-insulin induction was strictly dependent on R266, a residue that does not engage in thiol redox directly, but is required for the peroxidatic activity of TriPer C199 (Fig. 6e, Additional file 4: Figure S4C). In addition, the above H2O2 specificity controls of TriPer response exclude other possible artificial effects on the probe’s fluorophore, such as pH changes.

To further explore the links between glutathione depletion and accumulation of ER H2O2, we sought to measure the effects of selective depletion of the ER pool of glutathione on the ER H2O2 signal. ChaC1 is a mammalian enzyme that cleaves reduced glutathione into 5-oxoproline and cysteinyl-glycine [30]. We have adapted this normally cytosolic enzyme to function in the ER lumen and thereby deplete the ER pool of glutathione [9]. Enforced expression of ER-localized ChaC1 in RINm5F cells led to an increase in fluorescence lifetime of ER TriPer, which was attenuated by concomitant expression of ER-localized catalase (Fig. 6f). Cysteinyl-glycine, the product of ChaC1, has a free thiol, but its ability to balance ER H2O2 may be affected by other factors such as clearance or protonation status. Given the relative selectivity of ER-localized ChaC1 in depleting the luminal pool of glutathione (which equilibrates relatively slowly with the cytosolic pool [6, 9]), these observations further support a role for ER-localized glutathione in the elimination of luminal H2O2.

Analysis of the potential for uncatalyzed quenching of H2O2 by the ER pool of glutathione

Two molecules of reduced glutathione (GSH) can reduce a single molecule of H2O2, yielding a glutathione disulfide and two molecules of water, Eq. (1):

| 1 |

However there is no evidence that the ER is endowed with enzymes capable of catalyzing this thermodynamically favored reaction. For while the ER possesses two glutathione peroxidases, GPx7 and GPx8, both lack key structural determinates for interacting with reduced glutathione and function instead as peroxiredoxins, ferrying electrons from reduced PDI to H2O2 [15]. Therefore, we revisited the feasibility of a role for the uncatalyzed reaction in H2O2 homeostasis in the ER.

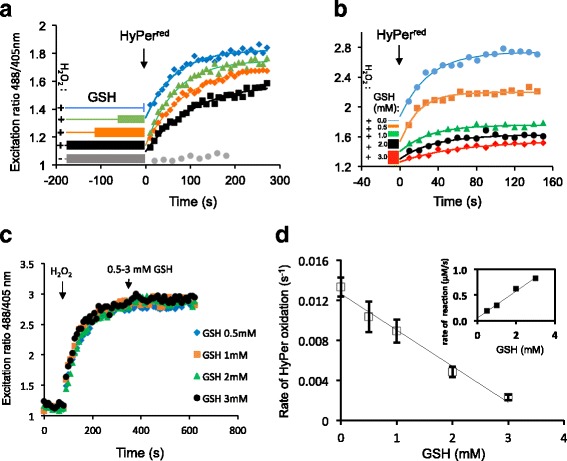

Previous estimates of H2O2’s reactivity with reduced glutathione (based on measurements conducted in the presence of high concentrations of both reagents) yielded a rate constant of 22 M–1s–1 for the bimolecular reaction [31]. Exploiting the in vitro sensitivity of HyPer to H2O2 (Fig. 2a), we revisited this issue at physiologically relevant conditions (pH 7.1, concentrations of reactants: [GSH] <3 mM, [H2O2] <10 μM), obtaining a similar value for the second-order rate constant (29 ± 4 M–1s–1, Fig. 7a–d).

Fig. 7.

Kinetics of uncatalyzed elimination of H2O2 by reduced glutathione.. a Traces of time-dependent changes to the excitation ratio (R488/405) of recombinant HyPer introduced into a solution of H2O2 (10 μM) that had been preincubated with GSH (3 mM) for increasing time periods, as indicated. Note the inverse relationship between HyPers oxidation rate and the length of the preceding H2O2-GSH preincubation. b As in a but following HyPer introduction into premixed solutions of H2O2 (10 μM) and reduced glutathione (GSH) at the indicated concentrations (0–3 mM). c As in a, but HyPer was exposed sequentially to H2O2 (2 μM) and various concentrations of GSH. d A plot of HyPer oxidation rate (reflecting the residual [H2O2]) as a function of GSH concentration. The slope (–0.0036 s–1 mM–1) and the y-intercept (0.01263 s–1) of the curve were used to extract the dependence of H2O2 consumption rate (–d[H2O2]/dt, at 10 μM H2O2) on each GSH concentration point (0–3 mM) according to Eqs. (2)–(4). The bimolecular rate constant was calculated by division of the slope of the resulting curve (shown in the inset) by the initial [H2O2] (10 μM)

Considering a scenario whereby oxidative folding of pro-insulin (precursor of the major secretory product of β-cells) proceeds by the enzymatic transfer of two electrons from di-thiols to O2 (as in ERO1/PDI catalysis, generating one molecule of H2O2 per disulfide formed [10]), and given three disulfides in pro-insulin, a maximal production rate of 6*10-4 fmol pro-insulin/min/cell [32], and an ER volume of 280 fl [33], the resultant maximal generation rate of H2O2 has the potential to elevate its concentration by 0.098 μM s–1. Given the rate constant of 29 M–1s–1 for the bimolecular reaction of H2O2 with reduced glutathione and an estimated ER concentration of 15 mM GSH [4], at this production rate the concentration of H2O2 would stabilize at 0.23 μM, based solely on uncatalyzed reduction by GSH. Parallel processes that consume H2O2 to generate disulfide bonds would tend to push this concentration even lower [12, 13, 15, 34]; nonetheless, this calculation indicates that GSH can play an important role in the uncatalyzed elimination of H2O2 from the ER.

Discussion

The sensitivity of β-cells to glutathione depletion, the accentuation of this toxic effect by pro-insulin synthesis, and the ability of ER catalase to counteract these challenges all hinted at a role for glutathione in coping with the burden of H2O2 produced in the ER. However, without means to track H2O2 in the ER of living cells, this would have remained an untested idea. TriPer has revealed that ER hydrogen peroxide levels increase with increased production of disulfide bonds in secreted proteins, providing direct evidence that the oxidative machinery of the ER does indeed produce H2O2 as a (bi)product. Less anticipated has been the increased H2O2 in the ER of glutathione-depleted cells. The contribution of glutathione to a reducing milieu in the nucleus and cytoplasm is well established, but it has not been easy to rationalize its presence in the oxidizing ER, especially as glutathione appears dispensable for the reductive step of disulfide isomerization in oxidative protein folding [9]. Consistently, the ER thiol redox poise resisted glutathione depletion. TriPer has thus pointed to a role for glutathione in buffering ER H2O2 production, providing a plausible benefit from the presence of a glutathione pool in the ER lumen.

TriPer’s ability to sense H2O2 in a thiol-oxidizing environment relies on the presence of an additional cysteine residue (A187C) near the resolving C208 in the OxyR segment. The presence of this additional cysteine attenuates the optical responsiveness of the probe to oxidation by PDI by creating a diversionary disulfide involving C208. Importantly, this diversionary disulfide, which forms at the expense of the (optically active) C199-C208 disulfide, preserves a fraction of the peroxidatic C199 in its reduced form. Thus, even in the thiol-oxidizing environment of the ER, a fraction of C199 thiolate is free to form a reversible H2O2-driven sulfenic intermediate that is resolved by disulfide formation in trans. Furthermore, by preserving a fraction of C199 in its reduced form, the diversionary C187-C208 disulfide also maintains a pool of C199 to resolve the C199 sulfenic to form a trans-disulfide bond. Thus, the H2O2-induced formation of the trans disulfide is a feature unique to TriPer, and it too is a consequence of the diversionary disulfide, which eliminates the strongly competing reaction of the resolving C208 in cis with the sulfenic acid at C199.

The ability of ER-expressed TriPer to alter its optical properties in response to H2O2 is enabled through its semioxidized steady state, dictated by kinetically/quantitatively dominant PDI. In vitro this stage can be reached by oxidants such as diamide or PDI, while the second oxidation phase, with lowering R488/405, is exclusive to H2O2. The net result of the presence of a diversionary thiol at TriPer residue 187 (A187C) is to render the probe optically sensitive to H2O2 even in the presence of high concentrations of oxidized PDI, conditions in which the precursor probe, HyPer, loses all optical responsiveness.

The aforementioned theoretical arguments for TriPer’s direct responsiveness to H2O2 are further supported by empirical observations: the peroxidatic potential (unusual for cysteine thiols) of the probe’s C199 is enabled through a finely balance charge distribution in its vicinity, of which R266 is a crucial determinant [25]. Eliminating this charge yielded a probe variant with its intact cysteine system, but it was unresponsive to H2O2. Further, the ability of ER catalase to reverse the changes in TriPer’s disposition argues that these are initiated by changes in H2O2 concentration.

Both HyPer and TriPer react with elements of the prevailing ER thiol redox buffering system (exemplified by their equilibration, in vitro, with PDI). In the case of HyPer, this reactivity is ruinous, but even in the case of ER TriPer, which retains a modicum of sensitivity to H2O2, the elements of the complex kinetic regime that drive its redox state are not understood in quantitative terms. Thus, it is impossible to fully deconvolute the potential impact on TriPer of changes in the ER thiol redox milieu from changes in H2O2 concentration wrought by a given physiological perturbation — TriPer is sensitive to both. However, it is noteworthy that oxidation of TriPer by H2O2, leading to a mixed disulfide state, shifts the optical readout towards lower R488/405 and shorter fluorescent lifetimes. Although such shifts are also consistent with a surge in thiol reductive activity, it seems unlikely that exposure of cells to H2O2 results in a more thiol-reducing ER. Similar considerations apply to the state of the ER in cells depleted of glutathione, as it is hard to imagine how this would lead to a more thiol-reducing ER. Indeed the H2O2-insensitive redox probe roGFPiE, which is known to equilibrate with ER-localized PDI, was unaffected by glutathione depletion. Thus, while we cannot formally exclude that glutathione depletion also affects TriPer’s redox status independently of changes in H2O2 concentration, the bulk of the evidence favors a role for TriPer in tracking the latter and in reporting on an increase in ER H2O2 in glutathione-depleted cells.

TriPer has been instrumental in flagging glutathione’s role in buffering ER luminal H2O2. This raises the question as to whether the thermodynamically favored reduction of H2O2 by GSH is accelerated by ER-localized enzymes or proceeds by uncatalyzed mass action. The cytoplasm and mitochondria possess peroxide-consuming enzymes that are fueled by reduced glutathione [35]. However, the ER lacks known counterparts. Such enzymes may be discovered in the future, as well as possible pathways of GSH-mediated PDRX4 modulation. But meanwhile it is notable that the kinetic properties of the uncatalyzed reduction of H2O2 by GSH are also consistent with a contribution to keeping H2O2 concentration at bay.

An ER that eschews catalyzed reduction of H2O2 by GSH and relies instead on the slower uncatalyzed reaction may acquire certain advantages. At low concentrations of H2O2, an ER organized along these lines would be flexible to deploy a kinetically favored PRDX4-mediated peroxidation reaction to exploit H2O2 generated by ERO1 for further disulfide bond formation [13, 36]. At higher concentrations of H2O2, PRDX4 inactivation [37] limits the utility of a PRDX4-based coping strategy [12, 37]. However, the concentration-dependent reduction of H2O2 by GSH is poised to counteract a build-up of ER H2O2. Although uncertainty regarding the rate of H2O2 transported across the ER membrane exists [38], we favor a model whereby such transport is comparatively slow [11], which is consistent with the observed delay between the increase in ER and cytosolic H2O2 when glutathione synthesis was inhibited. Sequestration of H2O2 in the lumen of the ER protects the genome from this potentially harmful metabolite and enables the higher concentrations needed for the uncatalyzed reaction to progress at a reasonable pace.

The implementation of a probe that detects H2O2 in thiol-oxidizing environments has revealed a remarkably simple mechanism to defend the cytosol and nucleus from a (bi)product of oxidative protein folding in the ER. This mechanism is especially important in secretory pancreatic β-cells that are poorly equipped with catalase/peroxidase.

Conclusions

Here we report on the development and mechanistic characterization of an optical probe, TriPer, that circumvents the limitations of previous sensors by retaining specific responsiveness to H2O2 in thiol-oxidizing environments. Application of this tool to the ER of an insulin-producing pancreatic β-cells model system revealed that ER glutathione antagonizes locally produced and potentially cytotoxic H2O2, resulting from the oxidative folding of pro-insulin.

The redox biochemistry concept developed here sets a precedent for exploiting a tri-cysteine relay system to discriminate between various oxidative reactants in complex redox milieux.

Methods

Plasmid construction

Additional file 5: Table S1 lists the plasmids used, their lab names, description, published reference, and a notation of their appearance in the figures.

Transfections, cell culture, and cell survival analysis

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), HEK293t (RRID:CVCL_0063), and COS7 (RRID:CVCL_0224) cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium (DMEM); RINm5F (RRID:CVCL_0501) cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI, Sigma, Gillingham, Dorset, UK), both supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum; and periodically confirmed to be mycoplasma free.

RINm5F cells containing a tetracycline/doxycycline inducible human pro-insulin gene (RINm5FTetON-Ins) were generated using the Lenti-XTM Tet-On® 3G system (Clontech, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France), according to the manufacturer’s manual. RINm5F cells stably expressing cytoplasmic or ER-adapted [39] human catalase were described in [11, 40].

Transfections were performed using the Neon Transfection System (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) applying 3 μg of ERTriPer or ERHyPer DNA/1 × 106 cells.

For the survival assays, 3 × 104 cells per 35-mm well were plated and exposed to various concentrations of BSO starting 4 h after the seeding for 48 h (RINm5F cells) or 96 h (MEFs, HEK293t, COS7 cells). At the end of this period, BSO was washed out and the cells were allowed to recover up to the point where the untreated sample reached 90% confluence. Then the cells were fixed in 5% formaldehyde (Sigma, Gillingham, Dorset, UK) and stained with Gram’s crystal violet (Fluka-Sigma, Gillingham, Dorset, UK). For quantification of the stain incorporated into each sample (proportional to the cell mass), the sample was solubilized in methanol and subjected to absorbance measurements at 540 nm using a VersaMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The readouts of each set were normalized to the maximum value (untreated sample).

Quantification of catalase enzymatic activity

Catalase enzyme activity was quantified as described earlier [41]. Briefly, whole-cell extracts were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) through sonication on ice with a Braun-Sonic 125 sonifier (Braun, Melsungen, Germany). Subsequently the homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g and 4 °C for 10 min. The protein content of the supernatant was assessed with a BCA Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). For quantification of the catalase enzyme activity, 5 μg of the total protein lysate was added to 50 mmol/L potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) containing 20 mmol/L H2O2. The specific catalase activity was measured by ultraviolet spectroscopy, monitoring the decomposition of H2O2 at 240 nm and calculated as described in [41].

Immunofluorescence staining

Prior to immunofluorescence staining, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100/PBS, and blocked with 10% goat serum/PBS. Total mouse monoclonal anti-insulin IgG (I2018, clone K36AC10, Sigma, Gillingham, Dorset, UK, RRID:AB_260137) was used as the primary antibody and goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to DyLight 543 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA) as the secondary antibody.

Confocal microscopy, fluorescence lifetime imaging, and image analysis

Cells transfected with the H2O2 reporters (HyPer or TriPer) were analyzed using a laser scanning confocal microscopy system (LSM 780; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with a Plan-Apo-chromat 60x oil immersion lens (NA 1.4), coupled to a microscope incubator, maintaining standard tissue culture conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2), in complete medium. Fluorescence ratiometric intensity images (512 × 512 points, 16 bit) of live cells were acquired. A diode 405 nm and argon 488 nm lasers (6% and 4% output respectively) were used for excitation of the ratiometric probes in the multitrack mode with an HFT 488/405 beam splitter, the signal was detected with 506–568 nm band pass filters, the detector gain was arbitrarily adjusted to yield an intensity ratio of the two channels to allow a stable baseline and detection of its redox-related alterations.

The FLIM experiments were performed on a modified version of a previously described laser scanning multiparametric imaging system [42], coupled to a microscope incubator, maintaining standard tissue culture conditions (Okolab, Pozzuoli, Italy), using a pulsed (sub-10 ps, 20–40 MHz) supercontinuum (430–2000 nm) light source (SC 450, Fianium Ltd., Southampton, UK). The desired excitation wavelength (typically 470 nm) was tuned using an acousto-optic tunable filter (AA Opto-electronic AOTFnC-VIS). The desired emission was collected using 510/42 and detected by a fast photomultiplier tube (PMC-100, Becker & Hickl GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Lifetimes for each pixel were recorded using time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) circuitry (SPC-830, Becker & Hickl GmbH), keeping count rates below 1% of the laser repetition rate to prevent pulse pile-up. Images were acquired over 20–60 s, with a typical flow rate of 5 × 104 photons s-1 , avoiding the pile-up effect. The data were processed using SPCImage (Becker & Hickl GmbH), fitting the time-correlated photon count data obtained for each pixel of the image to a monoexponential decay function, yielding a value for lifetime on the picosecond scale.

After filtering out autofluorescence (by excluding pixels with a fluorescence lifetime that was out of range of the probes), the mean fluorescence lifetime of single cells was established. Each data point is constituted by the average and SD of measurements from at least 20 cells. Calculations of p values were performed using the two-tailed t test function in Microsoft Excel 2011 software.

Protein purification and kinetic assays in vitro

For in vitro assays, human PDI (PDIA1 18–508), HyPer, and TriPer were expressed in the Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) strain, purified with Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) affinity chromatography and analyzed by fluorescence excitation ratiometry as previously described [43]. Briefly, HyPer, TriPer, and their mutants were assayed in vitro in Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl after being reduced with 50 mM DTT for 1 h followed by gel filtration to remove DTT.

To establish the reactivity of H2O2 with GSH, different amounts of GSH (0–3 mM, pH adjusted to 7.1; Sigma, Gillingham, Dorset, UK) were mixed with 10 μM of H2O2 for a fixed time period and then exposed to recombinant HyPer (2 μM, reduced by 40 mM DTT and gel filtered to remove DTT). The relationship between the rate of HyPer oxidation and [GSH], described by Eq. (2), was used to extract the remaining [H2O2] after its exposure to various [GSH] for a given period, using Eq. (3).

| 2 |

where the rates of HyPer oxidation (s–1) in a given [H2O2] are denoted by R g (GSH-affected) and R i (in the absence of GSH), and S 1 is the experimental coefficient (s–1 mM–1). The latter two are the y-intercept and the slope of the curve in Fig. 7d, accordingly.

| 3 |

where [H2O2]R and [H2O2]I are the residual and initial H2O2 concentrations accordingly. The resulting [H2O2] concentrations for each experimental [GSH] point were used to calculate the corresponding reaction rate according to Eq. (4), developed based on Eq. (3) for the special case of H2O2 – GSH reaction time (t) and [H2O2] (resulting curve shown in Fig. 7d inset, S 2 is the slope). The bimolecular rate constant (k) is given by Eq. (5).

| 4 |

| 5 |

The concentration of H2O2 at the equilibrium where the rate of its supply equals the rate of its reaction with GSH was calculated according to Eq. (6):

| 6 |

where V [H2O2] is the assumed rate of H2O2 generation and k is the bimolecular rate constant for the GSH/H2O2 reactivity.

Additional files

Variable sensitivity of cultured cells to glutathione depletion. As in Fig. 1a, absorbance at 540 nm (an indicator of cell mass) by cultures of parental RINm5F, RINm5F stably overexpressing catalase in their cytosol (CATcyto), HEK293, or COS7 cells that had been exposed to the indicated concentration of BSO before fixation and staining with crystal violet. (PDF 91 kb)

The role of R266 in HyPer and TriPer’s reactivity with H2O2. (A) Traces of time-dependent changes to the excitation ratio of recombinant HyPer or TriPer variants with the inactivating R266A mutation. (B) Non-reducing and reducing SDS-PAGE of recombinant TriPerR199A following incubation with increasing concentrations of H2O2 for 15 min. (C) Non-reducing gradient SDS-PAGE (pH 7.3, 4–12%) of samples as in Fig. 2g. (D) Traces of time-dependent changes to the excitation ratio of HyPer and TryPer mutant variants treated as in (B). Note that the variants lacking the ability to form C199-C208 disulfide do not change their excitation ratio upon oxidation. (PDF 93 kb)

In vitro, H2O2-driven formation of disulfide-bonded high molecular weight TriPer species with divergent optical properties. (A) Coomassie-stained non-reducing and reducing SDS-PAGE of wild-type TriPer or its mutant variant lacking the peroxidatic cysteine (TriPer C199S) following exposure to 1.5 μM of H2O2 for the indicated time period. Black arrow denotes disulfide-bonded high molecular weight TriPer species. (B) As in (A), but following a 15-min exposure to increasing concentrations of oxidized PDI (0–8 mM). Note the lack of the high molecular weight species in this sample and their prominence in the H2O2-treated sample, (A) above. (C) Excitation spectra (measured at emission 535 nm) of HyPer (orange trace) and TriPer (blue trace) for the different states of the probes, corresponding to phases 1–4 in Fig. 3c. (PDF 205 kb)

Glutathione depletion induced apoptotic cell death and leads to concordant changes in TriPerER optical properties. (A) Photomicrographs and fluorescence excitation ratiometric images of untreated (UNT) RINm5F cells transiently expressing TriPerER or cells treated with BSO (0.3 mM, 28 h) or H2O2 (0.2 mM, 15 min). The images were color coded for 488/405 nm excitation ratio (R488/405) according to the color map shown. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of RINm5F cells at the indicated time points after exposure to BSO (0.3 mM). Populations of dead and live cells were resolved by plotting forward vs. side scattering amplitudes (FCS-A and SSC-A accordingly). Apoptotic cell populations were assessed by detecting surface phosphatidylserine using phycoerythrin (PE) conjugated Annexin V. Note that a significant population of dead cells only emerges after 36 h, whereas an increase in the ER H2O2 signal is observed by 12 h (Fig. 6c). (C) A ratiometric trace of TriPerER WT or TriPerER containing an R266Q mutation expressed in RINm5F cells, exposed to H2O2 (0.2 mM) or DTT (2 mM) for the indicated duration. (PDF 636 kb)

List of plasmids. (PDF 56 kb)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Joseph E. Chambers for critical comments on the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust (Wellcome 200848/Z/16/Z, WT: UNS18966), Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal (PTDC/QUI/BIQ/119677/2010 and UID/BIM/04773/2013-CBMR), European Commission (EU FP7 Beta-Bat No: 277713), EPSRC (1503478), MRC (MR/K015850/1), and a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award for core facilities to the Cambridge Institute for Medical Research (Wellcome 100140). DR is a Wellcome Trust Principal Research Fellow.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional files or are available upon request, as are the non-standard materials.

Authors’ contributions

EPM designed, executed, and interpreted the in vitro redox and cell viability measurements. CL contributed to the in vitro experiments. PG executed in vivo ratiometric imaging. S. Lortz engineered and characterized the insulin inducible RINm5F system. S. Lenzen and IM contributed ideas and cell lines engineered to express organelle-targeted catalase and performed in vitro catalase activity analyses. CFK contributed to acquisition and analysis of the fluorescence lifetime imaging data. DR oversaw the project, contributed to the design and interpretation of the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. EA conceived and led the project, executed and interpreted in vivo measurements, contributed to execution of in vitro experimentation, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

David Ron, Phone: 01223 768 940, Email: dr360@medschl.cam.ac.uk.

Edward Avezov, Phone: 01223 768 940, Email: ea347@cam.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Sevier CS, Kaiser CA. Ero1 and redox homeostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783(4):549–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toledano MB, Delaunay-Moisan A, Outten CE, Igbaria A. Functions and cellular compartmentation of the thioredoxin and glutathione pathways in yeast. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18(13):1699–711. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bass R, Ruddock LW, Klappa P, Freedman RB. A major fraction of endoplasmic reticulum-located glutathione is present as mixed disulfides with protein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(7):5257–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montero D, Tachibana C, Rahr Winther J, Appenzeller-Herzog C. Intracellular glutathione pools are heterogeneously concentrated. Redox Biol. 2013;1(1):508–13. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuozzo JW, Kaiser CA. Competition between glutathione and protein thiols for disulphide-bond formation. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1(3):130–5. doi: 10.1038/11047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar C, Igbaria A, D’Autreaux B, Planson AG, Junot C, Godat E, Bachhawat AK, Delaunay-Moisan A, Toledano MB. Glutathione revisited: a vital function in iron metabolism and ancillary role in thiol-redox control. EMBO J. 2011;30(10):2044–56. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banhegyi G, Lusini L, Puskas F, Rossi R, Fulceri R, Braun L, Mile V, di Simplicio P, Mandl J, Benedetti A. Preferential transport of glutathione versus glutathione disulfide in rat liver microsomal vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(18):12213–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lombardi A, Marshall RS, Castellazzi CL, Ceriotti A. Redox regulation of glutenin subunit assembly in the plant endoplasmic reticulum. Plant J. 2012;72(6):1015–26. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsunoda S, Avezov E, Zyryanova A, Konno T, Mendes-Silva L, Pinho Melo E, Harding HP, Ron D. Intact protein folding in the glutathione-depleted endoplasmic reticulum implicates alternative protein thiol reductants. Elife. 2014;3:e03421. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gross E, Sevier CS, Heldman N, Vitu E, Bentzur M, Kaiser CA, Thorpe C, Fass D. Generating disulfides enzymatically: reaction products and electron acceptors of the endoplasmic reticulum thiol oxidase Ero1p. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(2):299–304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506448103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konno T, Pinho Melo E, Lopes C, Mehmeti I, Lenzen S, Ron D, Avezov E. ERO1-independent production of H2O2 within the endoplasmic reticulum fuels Prdx4-mediated oxidative protein folding. J Cell Biol. 2015;211(2):253–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201506123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tavender TJ, Bulleid NJ. Peroxiredoxin IV protects cells from oxidative stress by removing H2O2 produced during disulphide formation. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:2672–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.067843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zito E, Melo EP, Yang Y, Wahlander A, Neubert TA, Ron D. Oxidative protein folding by an endoplasmic reticulum-localized peroxiredoxin. Mol Cell. 2010;40(5):787–97. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramming T, Appenzeller-Herzog C. Destroy and exploit: catalyzed removal of hydroperoxides from the endoplasmic reticulum. Int J Cell Biol. 2013;2013:180906. doi: 10.1155/2013/180906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen VD, Saaranen MJ, Karala AR, Lappi AK, Wang L, Raykhel IB, Alanen HI, Salo KE, Wang CC, Ruddock LW. Two endoplasmic reticulum PDI peroxidases increase the efficiency of the use of peroxide during disulfide bond formation. J Mol Biol. 2011;406(3):503–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen HG, Schmidt JD, Soltoft CL, Ramming T, Geertz-Hansen HM, Christensen B, Sorensen ES, Juncker AS, Appenzeller-Herzog C, Ellgaard L. Hyperactivity of the Ero1alpha oxidase elicits endoplasmic reticulum stress but no broad antioxidant response. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(47):39513–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.405050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molteni SN, Fassio A, Ciriolo MR, Filomeni G, Pasqualetto E, Fagioli C, Sitia R. Glutathione limits Ero1-dependent oxidation in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(31):32667–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404992200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lenzen S, Drinkgern J, Tiedge M. Low antioxidant enzyme gene expression in pancreatic islets compared with various other mouse tissues. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20(3):463–6. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)02051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tiedge M, Lortz S, Drinkgern J, Lenzen S. Relation between antioxidant enzyme gene expression and antioxidative defense status of insulin-producing cells. Diabetes. 1997;46(11):1733–42. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.11.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belousov VV, Fradkov AF, Lukyanov KA, Staroverov DB, Shakhbazov KS, Terskikh AV, Lukyanov S. Genetically encoded fluorescent indicator for intracellular hydrogen peroxide. Nat Methods. 2006;3(4):281–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gehrmann W, Elsner M. A specific fluorescence probe for hydrogen peroxide detection in peroxisomes. Free Radic Res. 2011;45(5):501–6. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2011.560148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutscher M, Sobotta MC, Wabnitz GH, Ballikaya S, Meyer AJ, Samstag Y, Dick TP. Proximity-based protein thiol oxidation by H2O2-scavenging peroxidases. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(46):31532–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.059246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malinouski M, Zhou Y, Belousov VV, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. Hydrogen peroxide probes directed to different cellular compartments. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e14564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehmeti I, Lortz S, Lenzen S. The H2O2-sensitive HyPer protein targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum as a mirror of the oxidizing thiol-disulfide milieu. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53(7):1451–8. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi H, Kim S, Mukhopadhyay P, Cho S, Woo J, Storz G, Ryu SE. Structural basis of the redox switch in the OxyR transcription factor. Cell. 2001;105(1):103–13. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00300-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Avezov E, Cross BC, Kaminski Schierle GS, Winters M, Harding HP, Melo EP, Kaminski CF, Ron D. Lifetime imaging of a fluorescent protein sensor reveals surprising stability of ER thiol redox. J Cell Biol. 2013;201(2):337–49. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bilan DS, Pase L, Joosen L, Gorokhovatsky AY, Ermakova YG, Gadella TW, Grabher C, Schultz C, Lukyanov S, Belousov VV. HyPer-3: a genetically encoded H2O2 probe with improved performance for ratiometric and fluorescence lifetime imaging. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8(3):535–42. doi: 10.1021/cb300625g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Lith M, Tiwari S, Pediani J, Milligan G, Bulleid NJ. Real-time monitoring of redox changes in the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt 14):2349–56. doi: 10.1242/jcs.085530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birk J, Ramming T, Odermatt A, Appenzeller-Herzog C. Green fluorescent protein-based monitoring of endoplasmic reticulum redox poise. Front Genet. 2013;4:108. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar A, Tikoo S, Maity S, Sengupta S, Sengupta S, Kaur A, Bachhawat AK. Mammalian proapoptotic factor ChaC1 and its homologues function as gamma-glutamyl cyclotransferases acting specifically on glutathione. EMBO Rep. 2012;13(12):1095–101. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winterbourn CC, Metodiewa D. Reactivity of biologically important thiol compounds with superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27(3-4):322–8. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(99)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuit FC, Kiekens R, Pipeleers DG. Measuring the balance between insulin synthesis and insulin release. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;178(3):1182–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(91)91017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dean PM. Ultrastructural morphometry of the pancreatic β-cell. Diabetologia. 1973;9(2):115–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01230690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramming T, Hansen HG, Nagata K, Ellgaard L, Appenzeller-Herzog C. GPx8 peroxidase prevents leakage of H2O2 from the endoplasmic reticulum. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;70:106–16. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lillig CH, Berndt C, Holmgren A. Glutaredoxin systems. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780(11):1304–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tavender TJ, Springate JJ, Bulleid NJ. Recycling of peroxiredoxin IV provides a novel pathway for disulphide formation in the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 2010;29(24):4185–97. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X, Wang L, Wang X, Sun F, Wang CC. Structural insights into the peroxidase activity and inactivation of human peroxiredoxin 4. Biochem J. 2012;441(1):113–8. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Appenzeller-Herzog C, Banhegyi G, Bogeski I, Davies KJ, Delaunay-Moisan A, Forman HJ, Gorlach A, Kietzmann T, Laurindo F, Margittai E, et al. Transit of H2O2 across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane is not sluggish. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;94:157–60. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lortz S, Lenzen S, Mehmeti I. N-glycosylation-negative catalase: a useful tool for exploring the role of hydrogen peroxide in the endoplasmic reticulum. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;80:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lortz S, Lenzen S, Mehmeti I. Impact of scavenging hydrogen peroxide in the endoplasmic reticulum for beta cell function. J Mol Endocrinol. 2015;55(1):21–9. doi: 10.1530/JME-15-0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tiedge M, Lortz S, Munday R, Lenzen S. Complementary action of antioxidant enzymes in the protection of bioengineered insulin-producing RINm5F cells against the toxicity of reactive oxygen species. Diabetes. 1998;47(10):1578–85. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.10.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frank JH, Elder AD, Swartling J, Venkitaraman AR, Jeyasekharan AD, Kaminski CF. A white light confocal microscope for spectrally resolved multidimensional imaging. J Microsc. 2007;227(Pt 3):203–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2007.01803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Avezov E, Konno T, Zyryanova A, Chen W, Laine R, Crespillo-Casado A, Melo EP, Ushioda R, Nagata K, Kaminski CF, et al. Retarded PDI diffusion and a reductive shift in poise of the calcium depleted endoplasmic reticulum. BMC Biol. 2015;13(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s12915-014-0112-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gutscher M, Pauleau AL, Marty L, Brach T, Wabnitz GH, Samstag Y, Meyer AJ, Dick TP. Real-time imaging of the intracellular glutathione redox potential. Nat Methods. 2008;5(6):553–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morgan B, Van Laer K, Owusu TN, Ezerina D, Pastor-Flores D, Amponsah PS, Tursch A, Dick TP. Real-time monitoring of basal H2O2 levels with peroxiredoxin-based probes. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12(6):437–43. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sobotta MC, Liou W, Stocker S, Talwar D, Oehler M, Ruppert T, Scharf AN, Dick TP. Peroxiredoxin-2 and STAT3 form a redox relay for H2O2 signaling. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(1):64–70. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Variable sensitivity of cultured cells to glutathione depletion. As in Fig. 1a, absorbance at 540 nm (an indicator of cell mass) by cultures of parental RINm5F, RINm5F stably overexpressing catalase in their cytosol (CATcyto), HEK293, or COS7 cells that had been exposed to the indicated concentration of BSO before fixation and staining with crystal violet. (PDF 91 kb)

The role of R266 in HyPer and TriPer’s reactivity with H2O2. (A) Traces of time-dependent changes to the excitation ratio of recombinant HyPer or TriPer variants with the inactivating R266A mutation. (B) Non-reducing and reducing SDS-PAGE of recombinant TriPerR199A following incubation with increasing concentrations of H2O2 for 15 min. (C) Non-reducing gradient SDS-PAGE (pH 7.3, 4–12%) of samples as in Fig. 2g. (D) Traces of time-dependent changes to the excitation ratio of HyPer and TryPer mutant variants treated as in (B). Note that the variants lacking the ability to form C199-C208 disulfide do not change their excitation ratio upon oxidation. (PDF 93 kb)

In vitro, H2O2-driven formation of disulfide-bonded high molecular weight TriPer species with divergent optical properties. (A) Coomassie-stained non-reducing and reducing SDS-PAGE of wild-type TriPer or its mutant variant lacking the peroxidatic cysteine (TriPer C199S) following exposure to 1.5 μM of H2O2 for the indicated time period. Black arrow denotes disulfide-bonded high molecular weight TriPer species. (B) As in (A), but following a 15-min exposure to increasing concentrations of oxidized PDI (0–8 mM). Note the lack of the high molecular weight species in this sample and their prominence in the H2O2-treated sample, (A) above. (C) Excitation spectra (measured at emission 535 nm) of HyPer (orange trace) and TriPer (blue trace) for the different states of the probes, corresponding to phases 1–4 in Fig. 3c. (PDF 205 kb)

Glutathione depletion induced apoptotic cell death and leads to concordant changes in TriPerER optical properties. (A) Photomicrographs and fluorescence excitation ratiometric images of untreated (UNT) RINm5F cells transiently expressing TriPerER or cells treated with BSO (0.3 mM, 28 h) or H2O2 (0.2 mM, 15 min). The images were color coded for 488/405 nm excitation ratio (R488/405) according to the color map shown. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of RINm5F cells at the indicated time points after exposure to BSO (0.3 mM). Populations of dead and live cells were resolved by plotting forward vs. side scattering amplitudes (FCS-A and SSC-A accordingly). Apoptotic cell populations were assessed by detecting surface phosphatidylserine using phycoerythrin (PE) conjugated Annexin V. Note that a significant population of dead cells only emerges after 36 h, whereas an increase in the ER H2O2 signal is observed by 12 h (Fig. 6c). (C) A ratiometric trace of TriPerER WT or TriPerER containing an R266Q mutation expressed in RINm5F cells, exposed to H2O2 (0.2 mM) or DTT (2 mM) for the indicated duration. (PDF 636 kb)

List of plasmids. (PDF 56 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional files or are available upon request, as are the non-standard materials.