Abstract

Background

endothelial cells play a key role in vessels formation both under physiological and pathological conditions. Their behavior is influenced by blood components including gasotransmitters (H2S, NO and CO). Tumor cells are subjected to a cyclic shift between pro-oxidative and hypoxic state and, in this scenario, H2S can be both cytoprotective and detrimental depending on its concentration. H2S effects on tumors onset and development is scarcely studied, particularly concerning tumor angiogenesis. We previously demonstrated that H2S is proangiogenic for tumoral but not for normal endothelium and this may represent a target for antiangiogenic therapeutical strategies.

Methods

in this work, we investigate cell viability, migration and tubulogenesis on human EC derived from two different tumors, breast and renal carcinoma (BTEC and RTEC), compared to normal microvascular endothelium (HMEC) under oxidative stress, hypoxia and treatment with exogenous H2S.

Results

all EC types are similarly sensitive to oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide; chemical hypoxia differentially affects endothelial viability, that results unaltered by real hypoxia. H2S neither affects cell viability nor prevents hypoxia and H2O2-induced damage. Endothelial migration is enhanced by hypoxia, while tubulogenesis is inhibited for all EC types. H2S acts differentially on EC migration and tubulogenesis.

Conclusions

these data provide evidence for a great variability of normal and altered endothelium in response to the environmental conditions.

Keywords: Hydrogen sulfide, Human microvascular endothelial cells, Human breast carcinoma-derived EC, Human renal carcinoma-derived EC, Tumor angiogenesis

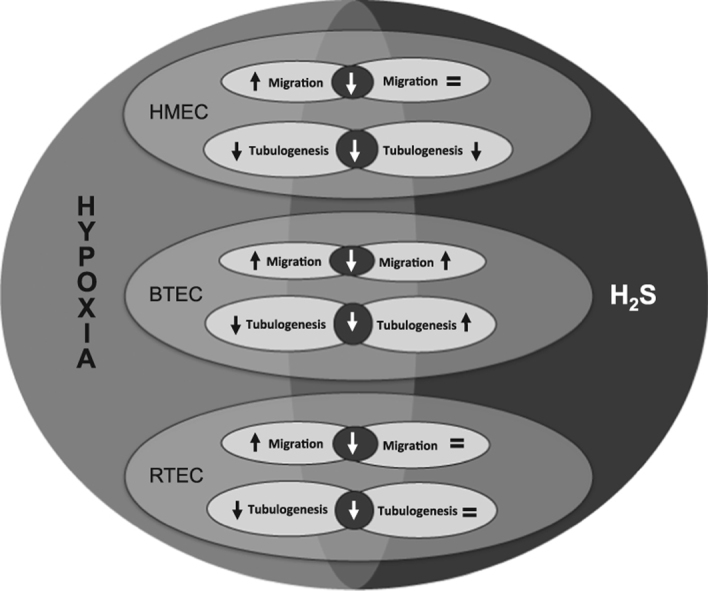

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

During physiological tissue development, vasculature organization and sprouting varies to meet blood demand. In solid tumors, however, the abnormal cell proliferation and vascular disorganization cause an insufficient blood supply, leading to glucose deprivation and hypoxia [1]. The hypoxic environment of tumors is heterogeneous, both spatially and temporally, and can change in response to cytotoxic therapy. Carcinomas usually support their growth by stimulating blood vessel development (angiogenesis) [2], [3]. Blood flow within these new vessels is often chaotic, causing alternating periods of hypoxia followed by re-oxygenation. Reperfusion is well established to cause generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) exacerbating the ischemic injury especially after myocardial or cerebral ischemia [4], [5]. Oxygen radicals production during reperfusion may, therefore, represent a source of ROS also within breast carcinomas and other solid tumors. In addition, in breast tumor, glucose deprivation rapidly induces cellular oxidative stress, as demonstrated in MCF-7 breast carcinoma cell line, although it does not cause oxidative stress in non-transformed cell lines [6]. This may be due to glucose deprivation, which depletes intracellular pyruvate within the breast carcinoma cell, preventing the decomposition of endogenous oxygen radicals.

In recent years increasing evidences emerged on the role of the bioactive gaseous molecule H2S in normal and tumor vascularization [7], [8]. In vascular endothelium H2S may act as vasorelaxant and anti-inflammatory agent as well as a powerful stimulator of angiogenesis. Indeed, H2S promotes mitosis, migration and tubulogenesis in human umbilical vein EC (HUVEC) and in the retinal endothelial cell (EC) line RF/6A [9], [10].

Oxidative stress promotes cell death in response to a variety of pathophysiological conditions and an excessive amount of ROS, including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), leads to lethal vascular endothelial cell injury [11]. Hydrogen sulfide has been shown to be protective against H2O2-induced oxidative stress: for example, 25–100 µM NaHS enhances cell survival upon H2O2 treatment in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts [12].

We recently described the effects of H2S on microvascular EC obtained from human breast carcinoma (BTEC). Ca2+ imaging and patch-clamp experiments revealed that acute perfusion with NaHS (a saline H2S donor) induces [Cai] increases, as well as [K+i] and non-selective cationic currents [13]. Stimulation with NaHS, at the same concentration range (1 nM–200 μM), evoked Cai signals also in normal human microvascular EC (HMVEC), although the amplitude was significantly lower. Conversely, doses lower than 10 μM of NaHS did not evoke any detectable elevation in Cai in the excised endothelium of rat aorta. Moreover, NaHS failed to promote either migration or proliferation on HMVEC, while BTEC migration was enhanced at low-micromolar NaHS concentrations (1–10 μM) [13]. Remarkably, pretreatment with an inhibitor of endogenous H2S production (PAG), drastically reduced migration and Cai signals induced by Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) in BTEC. These data suggest that H2S plays a role in proangiogenic signaling of tumor-derived but not normal human EC pointing to a potential differential sensitivity of normal EC compared to TEC that could be an interesting tool for tumor angiogenesis treatment. Furthermore, its ability to interfere with BTEC responsiveness to VEGF suggests that it could be an interesting target for antiangiogenic strategies in tumor treatment.

Here we unveil a great variability in the functional responses to hypoxia and oxidative stress and their regulation by exogenous H2S in endothelial cells derived from two different human carcinomas as well as normal microvascular endothelium.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell cultures

Breast tumor-derived endothelial cells (BTEC) and renal tumor-derived endothelial cells (RTEC) from human breast lobular-infiltrating carcinoma biopsy and renal carcinoma respectively, were isolated and periodically characterized in the laboratory of Professor Benedetta Bussolati (Department of Internal Medicine, Molecular Biotechnology Center and Research in Experimental Medicine Center, University of Torino, Italy). BTEC and RTEC were grown in EndoGRO-MV-VEGF Complete Media Kit, composed of EndoGRO Basal Medium and EndoGRO-MV-VEGF Supplement Kit (Merck Millipore). EndoGRO Basal Medium is a low-serum culture media for human microvascular endothelial cells, supplemented with a kit containing rhVEGF (5 ng/ml), rhEGF (5 ng/ml), rhFGF (5 ng/ml), rhIGF-1 (15 ng/ml), l-glutamine (10 mM), hydrocortisone hemisuccinate (1.0 μg/ml), heparin sulfate (0.75 U/ml), ascorbic acid (50 μg/ml), fetal bovine serum FCS 5%. Human microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC) are dermal-derived cells purchased from Lonza. HMEC, as well as BTEC, were grown in EndoGRO-MV-VEGF Complete Media Kit.

All cell cultures were maintained in normoxic (37 °C, 21% O2 and 5% CO2) and, when needed, hypoxic (37 °C, 5% O2 and 5% CO2) incubator (InVIVO2 200 equipped with a Ruskinn Gas Mixer Q) using Falcon™ plates as supports (about 5000 cells/cm2) and were used at passages 3–15. BTEC were cultured on 1% gelatin coating.

Chemical hypoxia was achieved by adding 100 µM CoCl2 to the medium for the indicated times (see Section 2.3, 3).

All experiments were performed using DMEM, Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (Sigma-Aldrich Corporate, MO, USA), with 4500 mg/L glucose, 15 mM HEPES and sodium bicarbonate. DMEM was supplemented with 2% l-glutamine, 0.5% gentamicin, and 1% fetal calf serum (FCS).

2.2. Chemicals

H2S donor NaHS was prepared fresh in stock solutions of 5 mM by dissolving the salt in deionized water. All experimental final concentrations were obtained by dilution in the culturing medium. Due to the well-known H2S volatility, dilution was made just before each experiment. NaHS releases H2S in a ratio of approximately 3:1.

CoCl2 and Hydrogen peroxide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA).

2.3. Viability and proliferation assays

Cells were plated on 96-well culture plates (104 or 0.5 ∙ 104 cells/well for viability and proliferation assays, respectively, on the basis of their duplication time (~30 h) in DMEM 1% FCS with/without treatments (4 wells/condition), considering. After 24 h (viability assay) or 72 h (proliferation assay) of treatment, cells were colored using the CellTiter 96® AQueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H tetrazolium, inner salt (MTS). MTS conversion into the aqueous soluble formazan product is accomplished by dehydrogenase enzymes found in metabolically active cells. Formazan product was measured as absorbance in a Bio-Rad microplate reader Model 550 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 490 nm; the values reported are directly proportional to the viable cell number at 24 and 72 h.

2.4. Cell migration assay

Scratch Wound Healing Assay. Cells were plated (2.5 ∙ 104 cells/cm2) using EndoGRO 5% FCS on 24-well culture plates pre-coated with 1% gelatin. Cells were maintained in incubator until confluence was reached. All cell types monolayers were starved for 6 h in DMEM 0% FCS. Motility assay was performed by generating a wound in the confluent cellular monolayers with a P10-pipette tip. Floating cells were removed by wash in PBS solution, and monolayers underwent to different experimental conditions (in duplicate). Incubation with DMEM 1% FCS served as control.

Experiments were performed under a Nikon Eclipse Ti (Nikon Corporation, Tokio, Japan) inverted microscope equipped with a A.S.I. MS-2000 stage and a OkoLab incubator (to keep cells at 37 °C and 5% CO2). Images were acquired at 2 h intervals using a Nikon Plan 4×/0.10 objective and a CCD camera. MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) was used to acquire images for 5 consecutive time points.

2.5. In vitro angiogenesis assay

In vitro formation of ‘capillary-like’ structures was studied on growth factor-reduced Matrigel (BD Bioscience, NJ, USA). Cells were seeded (3.5 ∙ 104 cells/well) onto Matrigel-coated 24-well plates in growth medium containing treatments (in duplicate). DMEM 1% FCS was used as control. Cell organization into Matrigel was periodically observed with the same set-up described above for wound healing assay and one-side migration assays using a Nikon Plan 10×/0.10 objective. Images were acquired at 2 h time intervals (9 time points) using MetaMorph software.

2.6. Radical oxygen species (ROS) detection assay

Cells were plated as described above for cytotoxicity assay. After 24 h of treatment, 2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescin diacetate (Sigma Aldrich) was added (10 µM) to cell culturing medium for 30 min. For hypoxia-reperfusion protocol, cells were maintained in hypoxia for 24 h and then in normoxia for 30 min. Fluorescence intensity, directly proportional to intracellular ROS concentration, was detected with a Bio-Rad microplate reader Model 550 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 530 nm.

2.7. Data analysis and statistics

In viability assays, absorbance values were analyzed with Excel software (Office, Microsoft) and normalized to the control.

Wound healing experiments were analyzed using Metamorph software. Cell migration was assessed by measuring the distance between the two sides of the wound at each time point. Data were further analyzed using Excel in order to calculate the percentage of migration for each wound (differential distance between cell fronts at two subsequent time points over distance at time 0) and the percentage mean value for each condition was then calculated. At least six fields for each condition were analyzed for every independent experiment. Where indicated, data were normalized to the control (100%) and relative migration was calculated, evaluating the propagation of errors for the S.E.M. of each treatment.

In in vitro angiogenesis assay, tubule length was evaluated with ImageJ and normalized to the control. Total tubule length for each condition was used to express the degree of organization in ‘capillary-like’ structures in terms of arbitrary units (AU). At least ten fields for each condition were analyzed in each independent experiment.

Statistical analysis of data was performed using the non-parametric Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test with Kaleidagraph software (Synergy Software). Data considered significant showed a p-value (p) <0.05. All experiments were carried out with a minimum of two biological replicates for each experimental condition. All experiments were repeated at least three independent times.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effect of H2O2 and hypoxia on endothelial cell viability

We first evaluated the viability of normal and tumor-derived human microvascular endothelial cell exposed to H2O2-induced oxidative stress and either chemically-induced or real hypoxia.

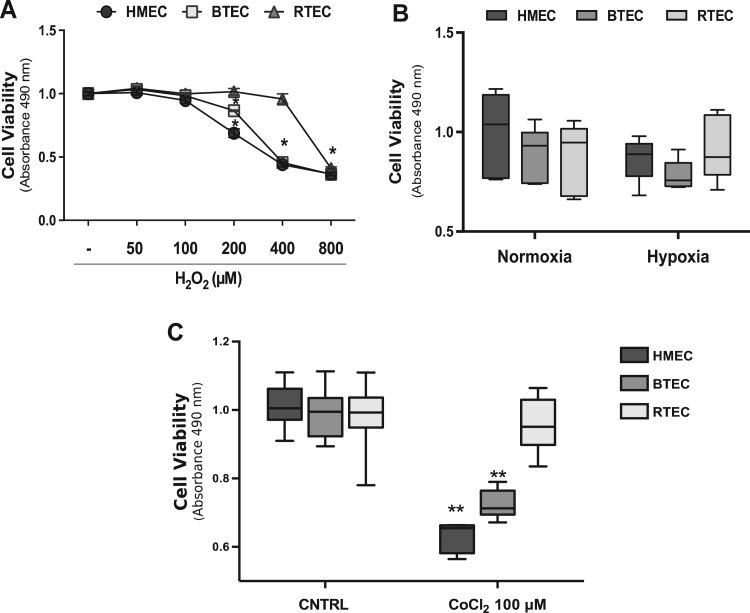

Incubation with H2O2 (from 50 to 800 µM) decreased cell viability upon 24 h of treatment both in normal (HMEC) and tumor-derived endothelium (breast and renal carcinoma-derived, BTEC and RTEC respectively), starting from 200 µM of H2O2 (Fig 1A): this observation is in line with the literature [11], [14]. On the other hand, hypoxia (37 °C, 5% O2 and 5% CO2; 8 h) did not affect the viability of all the three EC types measured at 24 h (Fig. 1B). Chemical hypoxia induced by high CoCl2 concentration (100 µM) differentially affected EC viability. Indeed, HMEC and BTEC survival was drastically reduced by CoCl2, leaving RTEC unaffected (Fig. 1C). This result suggests that EC from different tumors display a variable sensitivity to such a particular stress [15], [16], [17], [18].

Fig. 1.

High H2O2 and chemical hypoxia are toxic for EC. A) Representative dose-response curve of cytotoxicity assay on HMEC, BTEC and RTEC upon treatment with H2O2 (50–800 µM; 24 h). Data are expressed as the mean±S.E.M Wilcoxon test: *p<0.0001 vs CNTRL. B) Cytotoxicity experiment (24 h) performed on EC under normoxic or hypoxic conditions (see Section 2), in DMEM 1% FCS medium. Data from a representative experiment are expressed as the mean±S.E.M. Wilcoxon test. C) Viability assay on EC treated with CoCl2 (100 µM; 24 h). Data from a representative experiment are expressed as the mean±S.E.M. Wilcoxon test: **p<0.001 vs CNTRL. CNTRL: DMEM 1% FCS medium.

3.2. H2S is not protective against H2O2 and CoCl2-induced cytotoxicity and differentially affects EC proliferation

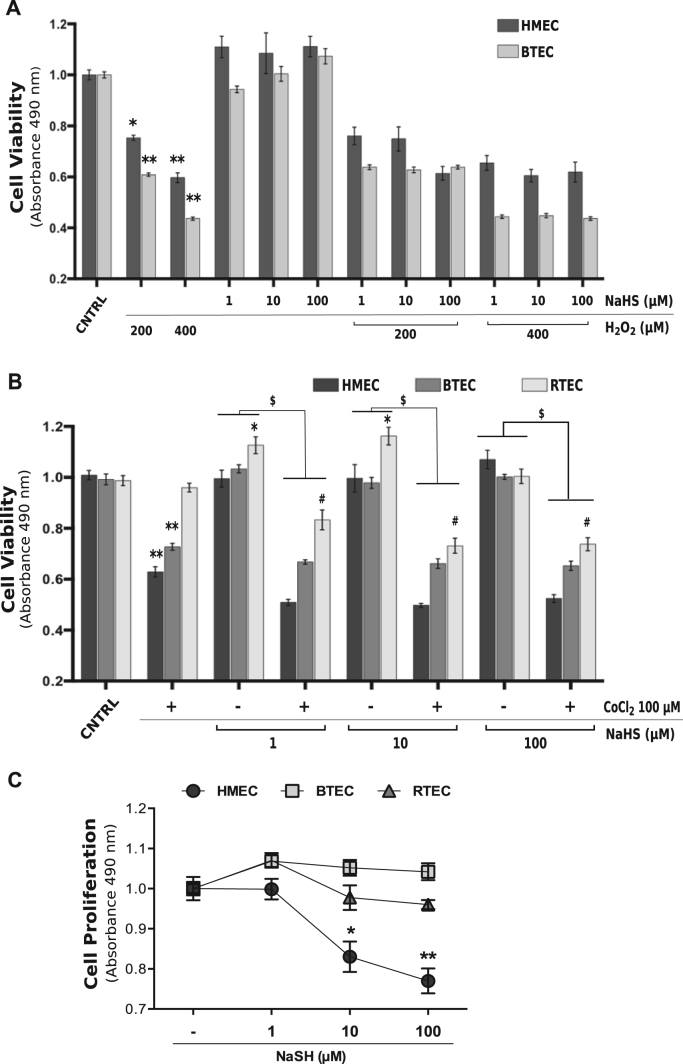

We previously demonstrated that exogenous H2S (released by a saline donor, NaHS) exerts proangiogenic effects in BTEC but not in HMEC. We therefore investigated whether the gasotransmitter could prevent the cytotoxicity provoked by H2O2 and CoCl2. NaHS alone was ineffective on EC viability at all the tested concentrations, although a slight (although not significant) effect was observed on HMEC. It failed to prevent cytotoxicity induced by high H2O2 (200 and 400 µM) in both normal HMEC and tumor-derived BTEC (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

H2S is not protective for EC against oxidative stress and chemical hypoxia toxicity. Cytotoxicity assay of HMEC, BTEC and RTEC treated for 24 h with NaHS (1–10–100 µM) and H2O2 (200 or 400 µM) (A) or CoCl2 100 µM (B) or the combination of the two, evaluated with MTS colorimetric kit (see Section 2). C) Proliferation assay of HMEC, BTEC and RTEC maintained for 72 h with NaHS (1–10–100 µM), evaluated with MTS colorimetric kit. Data from a representative experiment were normalized to the respective CNTRL and are expressed as the mean±S.E.M. Wilcoxon test: *p<0.01, **p<0.0001 vs CNTRL, #p<0.001 vs CoCl2 100 µM; $p<0.0001. CNTRL: DMEM 1% FCS medium.

When administered in the presence of CoCl2, NaHS did not rescue the toxic effects of chemical hypoxia, whereas the combination of the two treatments further reduced RTEC survival (Fig. 2B).

Moreover, high H2S concentrations (10–100 µM) inhibit HMEC, but not TEC, proliferation (Fig. 2C).

3.3. Hypoxia promotes endothelial migration but inhibits tubulogenesis

There is considerable evidence that hypoxia upregulates VEGF and angiopoietin 2, leading to the initiation and promulgation of angiogenesis [19], [20]. For this reason, we decided to evaluate the outcomes of hypoxia and exogenous H2S on EC migration and tubulogenesis.

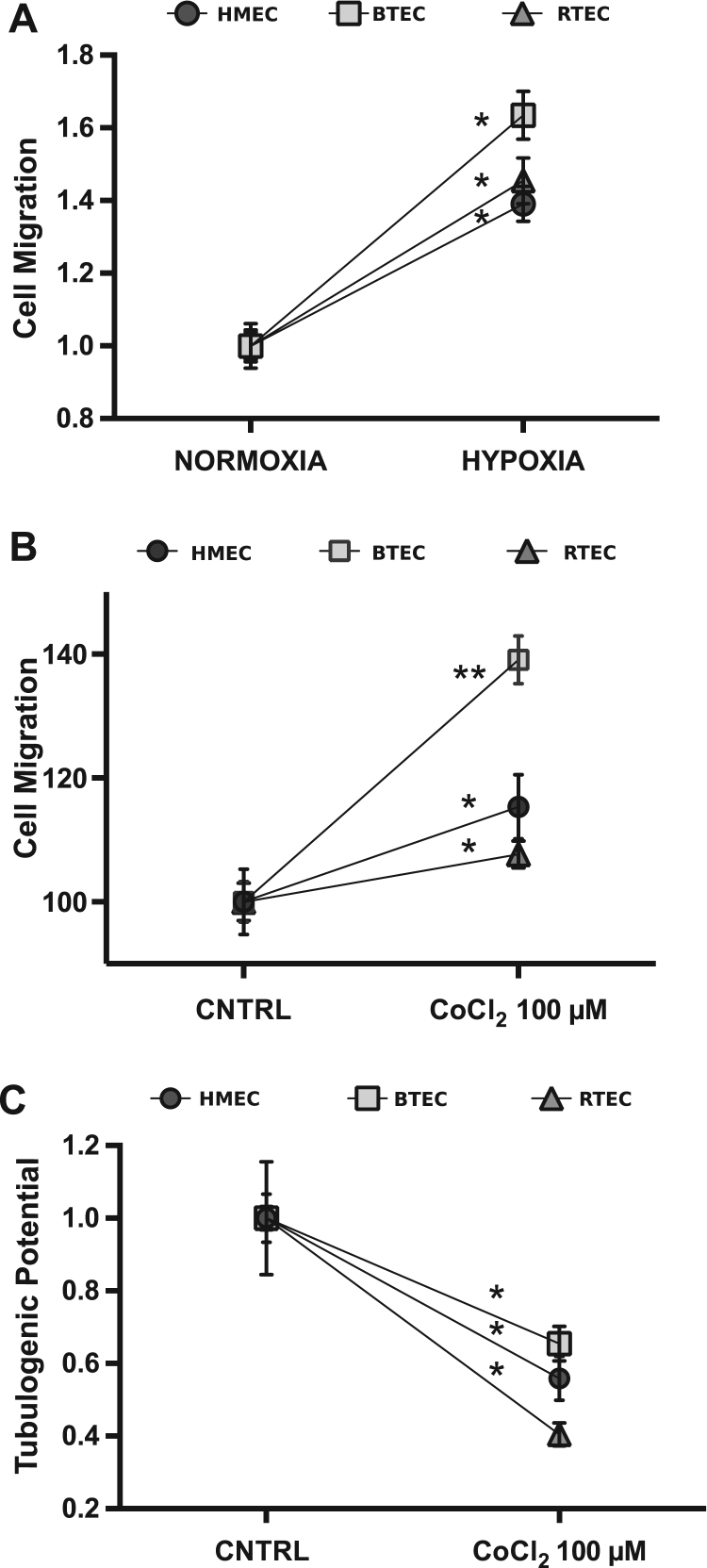

Here we show that hypoxia (8 h, 5% O2) enhances migration in all EC types grown in DMEM with 1% FCS (Fig. 3A). The same behavior was observed in the three EC types treated with CoCl2, with a migratory activity greater than in normoxic condition. Interestingly, the effect was particularly enhanced in BTEC (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Effects of hypoxia and CoCl2 on EC migration and tubulogenesis. A) Representative wound healing experiment in normoxic and hypoxic condition (see Section 2) on HMEC, BTEC and RTEC. Percentage of migration at 12 h in DMEM 1% FCS medium. Data are expressed as mean±S.E.M: *p<0.0001 vs. normoxia. Percentage of migration at 12 h (B) and tubulogenic potential (C) of HMEC, BTEC and RTEC upon chemical hypoxic condition (CoCl2 100 µM) treatment. Data were normalized to respective control and are expressed as mean±S.E.M: *p<0.01, **p<0.0001 vs CNTRL. CNTRL: DMEM 1% FCS medium.

Exposure to CoCl2 significantly decreased tubulogenic potential of all cell types tested (Fig. 3C), unlike previously reported for HUAEC and HUVEC [21], [22].

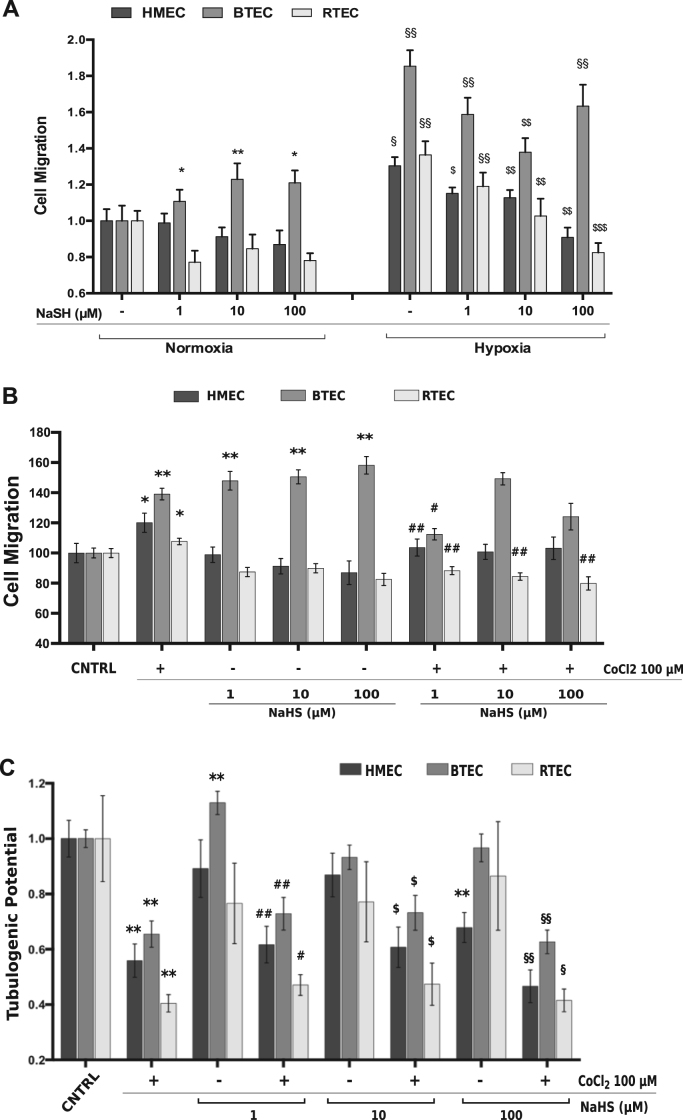

3.4. H2S differentially affects endothelial migration and is unable to revert the antitubulogenic effect of CoCl2

H2S displays variable effects on EC migration (Fig. 4A). Indeed, HMEC as well as RTEC migration were unaffected by all NaHS concentrations, while BTEC migration was strongly enhanced by the same NaHS treatments (Fig. 4A-B). Hypoxic conditions, as mentioned above, enhance migration in all EC when compared to normoxia. When H2S was administered during hypoxia, it partially rescued the hypoxia-induced effect in all three EC types, with a greater efficacy in RTEC.

Fig. 4.

Differential effects of H2S on EC migration and tubulogenesis. A-B) Representative Cell migration experiment on EC stimulated with NaSH (1–10–100 µM) and/or CoCl2 in hypoxia (A) or normoxia (B) conditions. Data were normalized to the respective CNTRL and are expressed as the mean±S.E.M. Wilcoxon test: *p<0.01, **p<0.0001 vs CNTRL normoxia; $p<0.05, $$p<0.001, $$$p<0.0001 vs CNTRL hypoxia; §p<0.01, §§p<0.0001 vs normossia; #p<0.001, ##p<0.0001 vs CoCl2 100 µM. C) In vitro tubulogenesis assay upon CoCl2 100 µM and NaHS treatment and the combination of the two of HMEC, BTEC and RTEC at 18 h. Tubulogenic potential express the total vessels length normalized to respective control. Total vessel length was measured for each field. Data are expressed as mean±S.E.M Wilcoxon test: **p<0.001 vs CNTRL; #p<0.01, ##p<0.0001 vs NaHS 1 µM; $p<0.01 vs NaHS 10 µM; §p<0.01, §§p<0.001 vs NaHS 100 µM. CNTRL: DMEM 1% FCS medium.

We therefore tested the effect of NaHS on the CoCl2-dependent migration. In HMEC, co-treatment with CoCl2 and NaHS showed that the CoCl2 promigratory effect was reverted by the lowest concentration of NaHS. In RTEC, in which NaHS alone was not effective, co-incubation of NaHS and CoCl2 prevented the pro-migratory activity of CoCl2 alone.

Interestingly, the combined treatment with CoCl2 and 1 µM NaHS limited BTEC migration, when compared to the two separate treatments (Fig. 4A). As previously shown in viability assays, TEC and HMEC display differential responsiveness to H2S and/or CoCl2 exposure.

H2S promoted differential effects on CoCl2-induced EC tubulogenesis. The lowest concentration of NaHS tested (1 µM) enhanced tubulogenesis only in BTEC, while the higher concentration (100 µM) was anti-tubulogenic for HMEC. RTEC tubulogenic potential was not affected by all concentrations of NaHS (Fig. 4B). The combination of CoCl2 and NaHS did not rescue the inhibition of tubulogenesis induced by CoCl2 alone in all cell types.

Taken together, our data reveal an overall great variability of different EC types, either normal and tumor-derived, in the response to chemically-induced or real hypoxia, as well as to H2S treatment. In addition, H2S activity strongly depends on its concentration, as already reported by previous reports on endothelial and other cell types [23], [24].

Moreover, evidence provided in this work indicates that H2S is not protective against hypoxia and oxidative stress for normal and altered vascular endothelium, differently from its well-known role on the heart [25], [26].

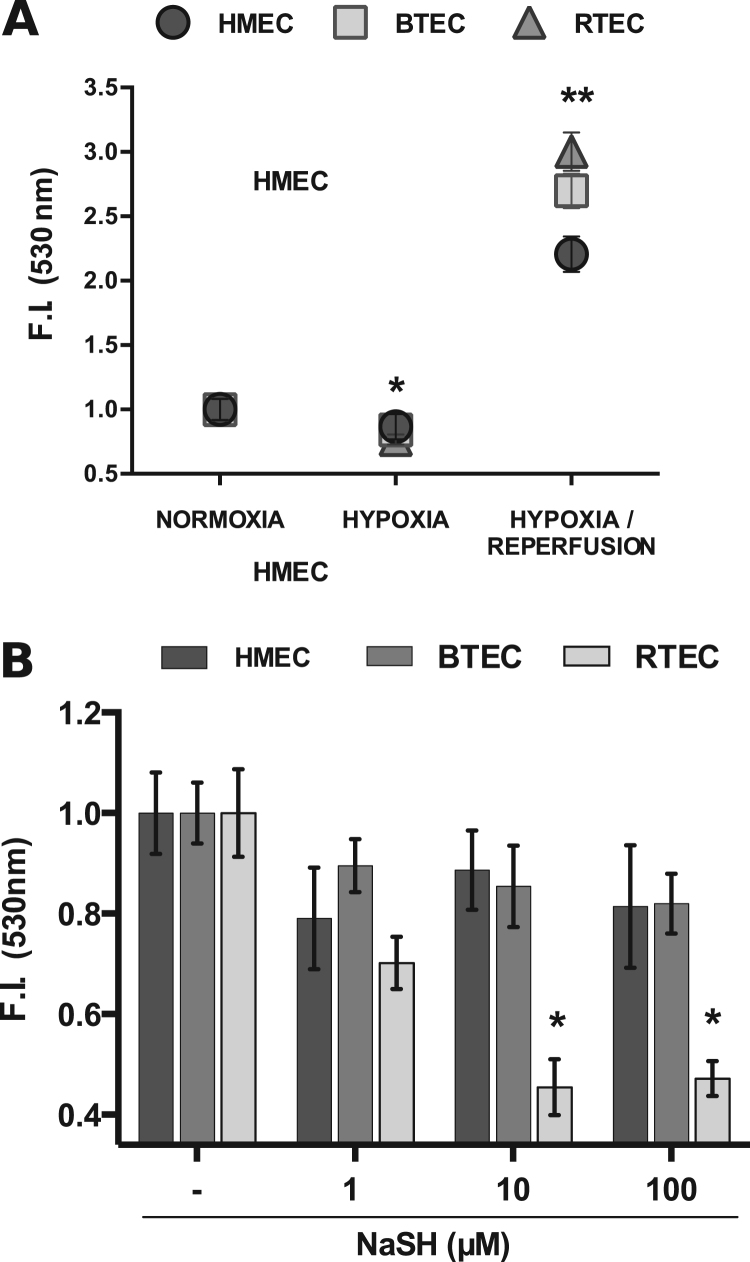

3.5. High doses of H2S affect ROS production only in RTEC

The tumor vasculature, due to its continuous mutation, causes alternation of hypoxia and re-oxygenation periods, which is well known to bring to a reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in diverse situation as in myocardial ischemia [4]. This condition leads to an oxidative stress state that alters cell metabolism and behavior.

Under hypoxic conditions, ROS level in all the EC types was lower than in normoxia, while during reperfusion is strongly increased (Fig. 5A). In normoxic environment, NaHS administration differentially affected ROS production. Indeed, only RTEC were affected by high doses of H2S with significant ROS reduction, while BTEC and HMEC were insensitive (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Endothelial ROS concentration. Endothelial ROS level evaluation in normoxic, hypoxic and re-oxygenation (see Section 2) conditions (A) or upon NaHS stimulation (1–10–100 µM) in normoxia (B). Data were normalized to the respective CNTRL and are expressed as the mean±S.E.M. Wilcoxon test: *p<0.01, **p<0.0001 vs CNTRL. CNTRL: DMEM 1% FCS.

These data confirm the diverse sensitivity of EC to H2S, but also suggest that ROS unlikely play a relevant role in the differential functional behaviors previously observed.

4. Conclusions

Oxidative stress and hypoxia have been shown to play a role in cell death and angiogenesis [11], [20]: moreover, H2S exerts a protective role against ROS in rat cardiomyoblasts [12], is promigratory and proangiogenic for HUVEC and retinal EC, but not for HMEC [9], [13], [25].

Here we report that human endothelial cells derived from two different tumors and from normal microvasculature are differentially sensitive to hypoxia and oxidative stress, as well as to their regulation by H2S. This variability should be carefully considered for a correct interpretation of the vascular effects observed upon antiangiogenic treatments in normal and altered tissues.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by MIUR (ex 60%).

Contributor Information

Serena Bianco, Email: serena.bianco@unito.it.

Daniele Mancardi, Email: daniele.mancardi@unito.it.

Benedetta Bussolati, Email: benedetta.bussolati@unito.it.

Luca Munaron, Email: luca.munaron@unito.it.

References

- 1.Fukumura D., Jain R.K. Tumor microenvironment abnormalities: causes, consequences, and strategies to normalize. J. Cell. Biochem. 2007;101(4):937–949. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longatto Filho A., Lopes J.M., Schmitt F.C. Angiogenesis and breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;2010:1782–1790. doi: 10.1155/2010/576384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon M.S., Mendelson D.S., Kato G. Tumor angiogenesis and novel antiangiogenic strategies. Int. J. Cancer. 2010;126(8):1777–1787. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Misra M.K., Sarwat M., Bhakuni P., Tuteja R., Tuteja N. Oxidative stress and ischemic myocardial syndromes. Med. Sci. Monit. 2009;15(10):RA209–RA219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szocs K. Endothelial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species production in ischemia/reperfusion and nitrate tolerance. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2004;23(3):265–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown N.S., Bicknell R. Hypoxia and oxidative stress in breast cancer. Oxidative stress: its effects on the growth, metastatic potential and response to therapy of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2001;3(5):323–327. doi: 10.1186/bcr315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mancardi D., Pla A.F., Moccia F., Tanzi F., Munaron L. Old and new gasotransmitters in the cardiovascular system: focus on the role of nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide in endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2011;12(9):1406–1415. doi: 10.2174/138920111798281090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee Z.-W., Deng L.-W. Role of H2S donors in cancer biology. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2015;230:243–265. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18144-8_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papapetropoulos A., Pyriochou A., Altaany Z., Yang G., Marazioti A., Zhou Z., Jeschke M.G., Branski L.K., Herndon D.N., Wang R., Szabó C. Hydrogen sulfide is an endogenous stimulator of angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106(51):21972–21977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908047106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai W.-J., Wang M.-J., Moore P.K., Jin H.-M., Yao T., Zhu Y.-C. The novel proangiogenic effect of hydrogen sulfide is dependent on Akt phosphorylation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2007;76(1):29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimizu S., Nomoto M., Yamamoto T., Momose K. Reduction by NG-nitro-L-arginine of H2O2-induced endothelial cell injury. Br. J. Pharm. 1994;113(2):564–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu D., Hu Q., Liu X., Pan L., Xiong Q., Zhu Y.Z. Hydrogen sulfide protects against apoptosis under oxidative stress through SIRT1 pathway in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Nitric Oxide. 2015;46:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pupo E., Fiorio Pla A., Avanzato D., Moccia F., Avelino Cruz J.E., Tanzi F., Merlino A., Mancardi D., Munaron L. Hydrogen sulfide promotes calcium signals and migration in tumor-derived endothelial cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011;51:1765–1773. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boonstra J., Post J.A. Molecular events associated with reactive oxygen species and cell cycle progression in mammalian cells. Gene. 2004;337:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piret J.-P., Mottet D., Raes M., Michiels C. CoCl2, a chemical inducer of hypoxia-inducible factor-1, and hypoxia reduce apoptotic cell death in hepatoma cell line HepG2. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002;973:443–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee M., Kang H., Jang S.-W. CoCl2 induces PC12 cells apoptosis through p53 stability and regulating UNC5B. Brain Res. Bull. 2013;96:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dai Z.-J., Gao J., Ma X.-B., Yan K., Liu X.-X., Kang H.-F., Ji Z.-Z., Guan H.-T., Wang X.-J. Up-regulation of hypoxia inducible factor-1α by cobalt chloride correlates with proliferation and apoptosis in PC-2 cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;31:28. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-31-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bussolati B., Grange C., Camussi G. Tumor exploits alternative strategies to achieve vascularization. FASEB J. 2011;25(9):2874–2882. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-180323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dewhirst M.W., Cao Y., Moeller B. Cycling hypoxia and free radicals regulate angiogenesis and radiotherapy response. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8(6):425–437. doi: 10.1038/nrc2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laderoute K.R., Alarcon R.M., Brody M.D., Calaoagan J.M., Chen E.Y., Knapp a.M., Yun Z., Denko N.C., Giaccia A.J. Opposing effects of hypoxia on expression of the angiogenic inhibitor thrombospondin 1 and the angiogenic inducer vascular endothelial growth factor. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000;6:2941–2950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan J.T.M., Prosser H.C.G., Vanags L.Z., Monger S.A., Ng M.K.C., Bursill C.A. High-density lipoproteins augment hypoxia-induced angiogenesis via regulation of post-translational modulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α. FASEB J. 2014;28(1):206–217. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-233874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abaci H.E., Truitt R., Tan S., Gerecht S. Unforeseen decreases in dissolved oxygen levels affect tube formation kinetics in collagen gels. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2011;301(2):C431–C440. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00074.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Y.C., Wang X.J., Yu L., Chan F.K.L., Cheng A.S.L., Yu J., Sung J.J.Y., Wu W.K.K., Cho C.H. Hydrogen sulfide lowers proliferation and induces protective autophagy in colon epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai W., Wang M., Ju L., Wang C., Zhu Y. Hydrogen sulfide induces human colon cancer cell proliferation: role of Akt, ERK and p21. Cell Biol. Int. 2010;34(6):565–572. doi: 10.1042/CBI20090368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang B., Hong J., Xiao J., Zhu X., Ni X., Zhang Y., He B., Wang Z. Involvement of miR-1 in the protective effect of hydrogen sulfide against cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by ischemia/reperfusion. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014;41(10):6845–6853. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3570-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen Y., Guo W., Wang Z., Zhang Y., Zhong L., Zhu Y. Protective effects of hydrogen sulfide in hypoxic human umbilical vein endothelial cells: a possible mitochondria-dependent pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14(7):13093–13108. doi: 10.3390/ijms140713093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]