Abstract

IL-10 limits the magnitude of inflammatory gene expression following microbial stimuli and is essential to prevent inflammatory disease, however, the molecular basis for IL-10 mediated inhibition remains elusive. Using a genome-wide approach we demonstrate that inhibition of transcription is the primary mechanism for IL-10-mediated suppression in LPS-stimulated macrophages, and that inhibited genes can be divided into two clusters. Genes in the first cluster are inhibited only if IL-10 is included early in the course of LPS stimulation and is strongly enriched for interferon-inducible genes. Genes in the second cluster can be rapidly suppressed by IL-10 even after transcription is initiated, and this is associated with suppression of LPS-induced enhancer activation. Interestingly, the ability of IL-10 to rapidly suppress active transcription exhibits a delay following LPS stimulation. Thus, a key pathway for IL-10 mediated suppression involves rapid inhibition of enhancer function during the secondary phase of the response to LPS.

INTRODUCTION

The response of macrophages even to a single inflammatory stimulus is remarkably complex. Stimulation of macrophages with LPS rapidly induces the activation of canonical transcription factors such as NF-κB and IRF3 in a protein synthesis independent manner, and this is quickly followed by rapid induction of mRNA for a number of primary response genes (1–3). Following this initial wave, there are subsequent waves of mRNA induction that are sensitive to inhibition of protein synthesis, indicating the secondary nature of the response (4). It has been documented that a significant proportion of secondary response genes are in fact responding to the primary induction of IFN-β, but several other factors are involved in driving secondary response genes including the atypical nuclear IκB-like molecule, IκBζ (5–7). While mRNA induction following LPS-stimulation of macrophages is likely regulated at multiple levels, detailed studies evaluating changes in newly synthesized mRNA strongly suggest that induction of new gene transcription is the driving force behind the observed global alterations in gene expression (1, 2).

Recently, it has been demonstrated that LPS-induced transcription in macrophages is associated with enhancer activation (8). Recruitment of stimulus-dependent transcription factors such as NF-κB to genomic sites termed poised enhancers is marked by binding of the pioneer transcription factor PU.1 and mono-methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me1). Activation of these enhancers is associated with increases in acetylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27Ac) and increased transcription of cis located genes (8–10). While there is increased appreciation for the role of enhancer activation in initiating LPS-induced transcription, there is much less known regarding the processes that terminate LPS-induced transcription, and we do not yet know how factors that limit LPS-induced transcription influence the activation state of LPS-induced enhancers.

One key factor that limits LPS-induced inflammatory gene expression in macrophages is the stimulus-induced production of IL-10, a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine (11). The receptor for IL-10 activates STAT3 through a JAK1 dependent pathway (12). Global profiling experiments comparing mRNA levels in IL-10-deficient macrophages treated with LPS alone or both LPS and IL-10 have identified a wide range of both primary and secondary response genes that are inhibited by IL-10, and studies in STAT3-deficient macrophages indicate that STAT3 is required for IL-10-mediated inhibition (11). Understanding the mechanism of STAT3-mediated inhibition in response to IL-10 has proven enigmatic. In most systems STAT3 is a transcriptional activator and there is little evidence that STAT3 has direct inhibitory function or binds to regulatory regions of IL-10-inhibited genes (13). This has led to the hypothesis that following IL-10R engagement, STAT3 induces genes that secondarily inhibit inflammatory gene expression. A number of STAT3 induced transcriptional inhibitors have been identified including Bcl3 and Nfil3, however studies in genetically-deficient macrophages have failed to demonstrate that these factors are required for IL-10-mediated inhibition (14, 15). A firm understanding of the kinetics of IL-10 mediated inhibition could contribute significantly to delineating potential inhibitory mechanisms, however current knowledge is lacking in this area.

Inhibitory functions for IL-10 in macrophages have been proposed at the level of transcription, mRNA stability, and translation of individual genes (16–19). With regards to transcription, Aste-Amezaga et al. used nuclear run-on assays to demonstrate that addition of IL-10 one hour prior to LPS stimulation inhibited transcription of IL12B in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (20). Murray used RT-PCR of primary transcripts to demonstrate that IL-10 added concomitantly with LPS inhibited transcription of Il1a, Cxcl1, Il6, and Tnf in IL-10-deficient bone marrow-derived macrophages (16). Further, studies of the Il12b promoter demonstrated that IL-10 inhibited histone H4 acetylation and prevented PolII association, consistent with inhibition of transcription (21). However, we do not yet understand the kinetics of IL-10-induced transcriptional inhibition nor the scope of IL-10-mediated inhibition of the LPS-induced transcriptional program. Further, we do not understand how IL-10 influences the activation status of LPS-induced enhancers (22), and whether suppression of active enhancers by IL-10 occurs in a time frame compatible with suppression of active transcription. Answering these questions would increase our understanding of mechanisms responsible for IL-10 mediated inhibition, and potentially lead to novel insights regarding mechanisms that terminate activation of inducible enhancers.

Delineating the kinetics of transcriptional inhibition using assays that measure mRNA is problematic because varying stability of mRNA makes it difficult to discern rapid changes in underlying transcriptional rates. Therefore, we used pre-mRNA as a surrogate of transcriptional rate, to provide a detailed analysis of the kinetics of IL-10 mediated transcriptional suppression. Further, using an RNA sequencing protocol that allowed us to separately analyze mRNA and pre-mRNA at the global level we have identified 2 clusters of IL-10 inhibited genes that exhibit different kinetics of suppression and provide a mechanism for these differences. Finally, using chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by DNA sequencing (ChIP-seq), we find that IL-10 induces highly dynamic alterations in enhancer activation that are associated with alterations in transcription of IL-10 targets. These studies significantly increase our understanding of mechanisms that regulate LPS-induced inflammatory gene expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals

All mouse strains were maintained on the 129S6/SvEvTac background. Generation of Rag2−/− (WT) and Il10−/−Rag2−/−(Il10−/−, IL-10-deficient) has been previously described (23). All animal procedures were approved by the Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on Animals.

BMDM Preparation and Stimulation

Bone marrow-derived macrophages were grown as previously described (24) and split into 24 well plates on the day prior to stimulation. BMDM were cultured in 500 μL of 10% FBS DMEM supplemented with pen/strep, HEPES, and Glutamax at a density of 2.5 x 105 cells/well for RNA extraction, or at 1 x 106 cells/well for western blotting. For stimulation, medium was removed and replaced with either fresh medium for unstimulated samples or medium containing 1 ng/mL LPS from E. coli serotype 0127:B8 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). IL-10 (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), which was used at a final concentration of 1 ng/mL. Actinomycin D (Sigma) was added 2 h after LPS stimulation to a final concentration of 5 μg/mL.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR

Cell culture medium was aspirated and cells were lysed in 500 μL TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). RNA was isolated per the manufacturer’s instructions with the addition of Glycoblue co-precipitant (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1–bromo–3–chloropropane (BCP) (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) in lieu of chloroform. cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of DNase treated RNA using random hexamers with the Taqman reverse transcription reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RT-PCR was performed using the StepOnePlus System with either TaqMan probes from Thermo Fisher Scientific, or with Sybr Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and custom primers. Primer sequences are available on request. Expression was normalized to GAPDH and differences between samples calculated using the ΔΔ cycle threshold method. Fold-change is reported relative to levels observed in untreated macrophages. In graphs of RT-PCR data each line represents BMDM from an individual mouse and each point on the line represents an individual well. Within the figure legends the term “n=” indicates the size of the experimental groups in the displayed experiment, and a statement regarding the number of times the experiment was performed is provided.

Western Blot

Cells were lysed in 100 μL RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 6.5 μL of lysate loaded onto Novex 4–12% Bis-Tris Gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Gels were transferred to PVDF membranes and blotted with anti-STAT3 (Cell Signaling, 4904), anti-pSTAT3 (Y705) (Cell Signaling, 9145), anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling, 5174).

ELISA

IL-12 p40 was measured in culture supernatants using capture antibody C15.6 (2 μg/ml) (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) and detection antibody C17-8 (0.5 μg/ml) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). IL-10 was measured using capture antibody JES5-16E3 (4 μg/mL) (ebioscience, San Diego, CA) and detected using antibody JES5-2A5 (0.5 μg/mL) (ebioscience). IFN-β was measured with the VeriKine Mouse IFN Beta ELISA kit per the manufacturer’s instructions (PBL Assay Science, Piscataway, NJ). Each data point represents the results from BMDM isolated from an individual mouse.

Total RNA-seq

BMDM were cultured in 6-well plates at 1 x 106 cells/well. Cells were rinsed once with PBS, and RNA isolated following addition of Trizol directly to the plate. RNA was further purified using the RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Ribosomal RNA was depleted using the NEBNext rRNA depletion kit, and libraries were made with the NEBNextUltra Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). Samples were sequenced using either the Illumina Hiseq or NextSeq Platforms. Data was analyzed as in Gaidatzis, et al.(25). Briefly, reads were aligned to mm10 using Rbowtie. Counts were generated using the QuasR package using qCount with only non-overlapping genes, and differential analysis was carried out using DESeq. To focus on genes that were strongly induced by LPS we used an FDR of 0.1 and only evaluated genes whose intronic signal increased by at least 100-fold. Further, we only evaluated genes that had at least 50 reads upon LPS stimulation. For genome level display, one replicate was normalized with deeptools (26) using the size factor generated by DESeq and displayed in the Integrative Genomics Viewer. Heatmap was generated in R.

ChIP-seq

Macrophages were plated at 2 x 107 cells per condition on 15cm plates and after stimulation fixed for 10 minutes in 1% formaldehyde. Chromatin was isolated and sheared by sonication (10 cycles, 20 s on, 30 s rest). After aliquoting an input fraction, 4 x 106 cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with Protein A Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) pre-coupled with 5 μg of anti-H3K27ac Ab (Abcam, ab4729) or 300 ng of anti-STAT3 Ab (Cell Signaling, 12640). After incubation, the beads were washed sequentially with a low salt buffer, high salt buffer, lithium chloride buffer, and TE buffer. DNA-protein complexes were eluted from the beads with 1% SDS TE buffer at 65°C for 15 min. Input and IP crosslinks were reversed by overnight incubation at 65°C. DNA was treated with proteinase K and RNase A (Thermo Fisher Scientific) before purification with the QIAquick PCR Purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

IP and input libraries were prepared using NEBNext ChIP-Seq Library Prep Master Mix Set for Illumina (New England Biolabs). Samples were sequenced using the Illumina NextSeq platform. Samples were aligned to mm10 using bowtie2 (27) with default parameters and peaks were called using MACS2 with the --broad flag on for H3K27Ac and H3K4me1. Differential peak calling for H3K27Ac was done with 3 biological replicates using the diffbind (28) package and the DESeq algorithm specifying an FDR < 0.1. For genome level display, one representative replicate’s libraries were normalized down to the depth of the least sequenced library and displayed as reads per base pair. STAT3 ChIP-seq data was analyzed in MACS using default parameters. Data was normalized to reads per million for display. For data from Ostuni et al., the untreated H3K4me1 sample was normalized to reads per million (8). Mean acetylation plots were made using deeptools (26). Plots and statistical analysis in Fig. 6 were done in R.

Statistical Analyses

Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate significant overrepresentation of Ifnar1 dependent genes (Fig. 3D). ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to identify significant differences in IFN-β secretion (Fig. 5B). The Mann-Whitney U test was used to identify significant differences in H3K27 enhancer acetylation ratios (Fig. 6A). 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used to identify significant differences in Cxcl2 pre-mRNA (Fig. 8A). For all analyses P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Endogenous IL-10 limits duration of IL-12 transcription

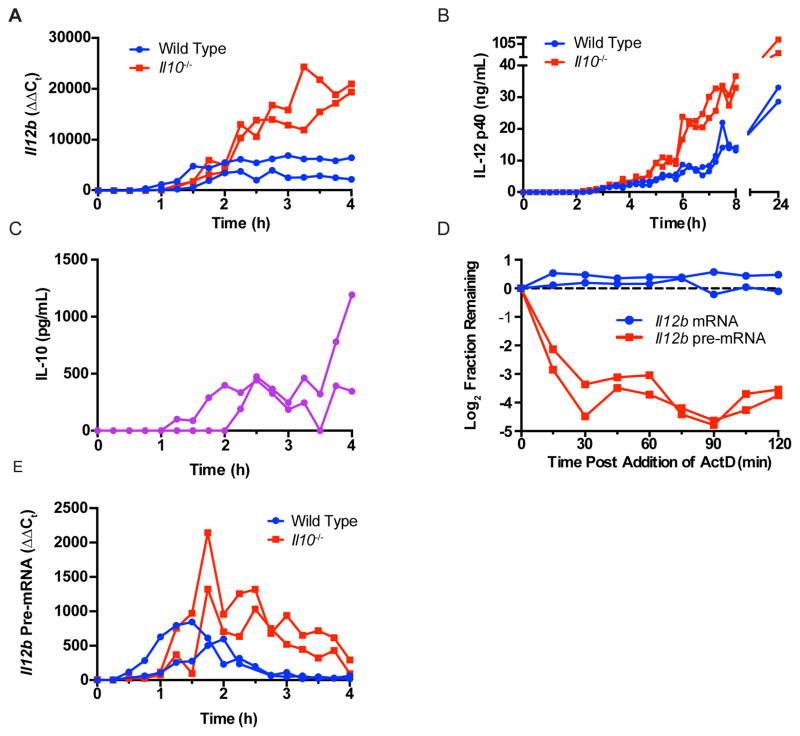

Il12b is an LPS-induced secondary response gene that is strongly inhibited by IL-10. Addition of exogenous IL-10 inhibits IL12B transcription in human PBMCs stimulated with LPS, and inhibits Il12b transcription in murine peritoneal macrophages stimulated with LPS and IFN-γ (11, 29). However, the kinetic relationship between expression of endogenous IL-10 and transcription of Il12b has not been fully explored. To evaluate this issue, we stimulated WT and IL-10 deficient BMDMs with LPS and evaluated expression of Il12b mRNA every 15 minutes from 0 to 4 hours. In WT BMDM, Il12b mRNA was first detected 60 minutes after stimulation and increased until reaching a plateau at 120 minutes that lasted for the duration of the experiment (Fig. 1A). In IL-10-deficient BMDM, Il12b expression appeared to begin at the same time as in WT cells, but rather than reaching a plateau at 2 hours continued to rise over the course of the next several hours. The difference in Il12b mRNA levels between WT and IL-10-deficient BMDM was reflected in increased IL-12 p40 secretion by IL-10 deficient macrophages (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that endogenously produced IL-10 limits Il12b mRNA production and that this phenomenon begins 2 hours after LPS stimulation. To determine whether this is consistent with the kinetics of endogenous IL-10 production, we performed an ELISA to measure IL-10 levels within the supernatants of LPS stimulated WT BMDM and found that IL-10 was first detected between 1 and 2 hours after LPS stimulation, indeed coinciding with the plateau phase of Il12b production observed in WT BMDM (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. IL-10 rapidly inhibits Il12b transcription.

(A) WT and Il10−/− BMDM were stimulated with LPS (1 ng/mL). RNA was harvested every 15 min for 4 h. Il12b mRNA was measured by RT-PCR and expression levels displayed relative to unstimulated levels using the ΔΔCt method (n=2). (B) WT and Il10−/− BMDM were stimulated with LPS and supernatants collected every 15 min up to 8 h as well as at 24 h. IL-12 p40 levels were measured by ELISA (n=2). (C) IL-10 levels in supernatants of WT BMDM were measured by ELISA (n = 2). (D) Actinomycin D (5 μg/mL) was added to WT BMDM 2 h after LPS stimulation, and RNA was harvested every 15 min for the ensuing 2 h. Il12b mRNA and pre-mRNA were measured by RT-PCR and displayed as the log2 fraction remaining compared to the time of actinomycin D addition (n=2). (E) Il12b pre-mRNA was measured by RT-PCR in RNA harvested from WT and Il10−/− BMDM, and displayed relative to the unstimulated levels (n=2). All experiments displayed in this figure were performed twice.

The observation that secretion of endogenous IL-10 results in a plateau in Il12b mRNA levels suggests that either the rates of transcription and degradation of Il12b are matched, or that transcription has ceased and the remaining Il12b message is highly stable. To assess the stability of Il12b mRNA we added the transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D 2 hours after LPS treatment of WT BMDM and measured levels of Il12b mRNA over the following 2 hours. We found very little change in levels of Il12b mRNA levels over the course of this experiment, indicating the mRNA was stable, and suggesting that transcription of Il12b had ceased following expression of IL-10 (Fig. 1D). It has been demonstrated that transcriptional activity can be evaluated through measurements of unspliced pre-mRNA, as pre-mRNAs typically have a very short lifespan (16, 30). Therefore, we designed RT-PCR primers that selectively recognized Il12b pre-mRNA but not mRNA. As predicted, levels of pre-mRNA fell very rapidly after administration of actinomycin D, indicating that measurement of pre-mRNA was an accurate surrogate for transcription (Fig. 1D). Following LPS stimulation of WT BMDM, levels of Il12b pre-mRNA rose somewhat earlier than what we had observed for levels of Il12b mRNA, but fell rapidly when Il12b mRNA reached the plateau phase (Fig. 1E), concomitant with accumulation of IL-10 within the supernatant of WT BMDM. In contrast, Il12b pre-mRNA levels continued to increase for several additional hours in IL-10-deficient BMDM (Fig. 1E). These results demonstrate that secretion of endogenous IL-10 rapidly inhibits transcription of Il12b.

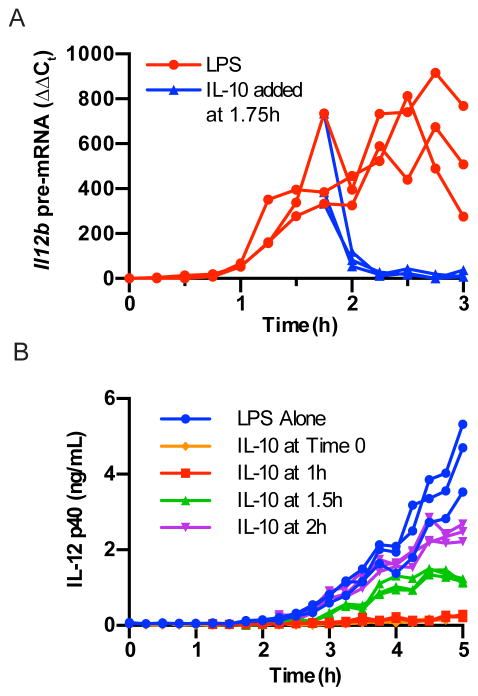

IL-10 rapidly inhibits active transcription of Il12b

The results above suggest that endogenous IL-10 rapidly suppresses transcription of Il12b in WT BMDM stimulated with LPS. To more accurately assess the kinetics of IL-10-mediated suppression, we added exogenous IL-10 to IL-10-deficient BMDM at a time of active Il12b transcription (1.75 hours after LPS stimulation). We observed significant suppression of Il12b transcription as early as 15 minutes after exposure, and nearly complete suppression by 30 minutes (Fig. 2A). Further, we found that addition of IL-10 led to a rapid plateau in levels of Il12b mRNA (data not shown). Consistent with these results, the timing of IL-10 addition strongly influenced the accumulation of IL-12 p40 within the culture medium (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that IL-10 rapidly inhibits transcription of Il12b in LPS-stimulated BMDM, and that this profoundly influences accumulation of secreted IL-12 p40.

Figure 2. Exogenous IL-10 rapidly inhibits Il12b transcription.

(a) Il10−/− BMDM were stimulated with LPS and then treated with IL-10 (1 ng/ml) at 1.75 hours or left untreated. RNA was collected every 15 min and Il12b pre-mRNA was measured by RT-PCR (n=3). This experiment was performed three times. (b) Il10−/− BMDM were stimulated with LPS with or without the addition of IL-10 at the indicated time points. IL-12 p40 levels in the supernatants were measured by ELISA every 15 min (n=3). This experiment was performed once.

Inhibition of transcription is a central mechanism of IL-10-mediated suppression

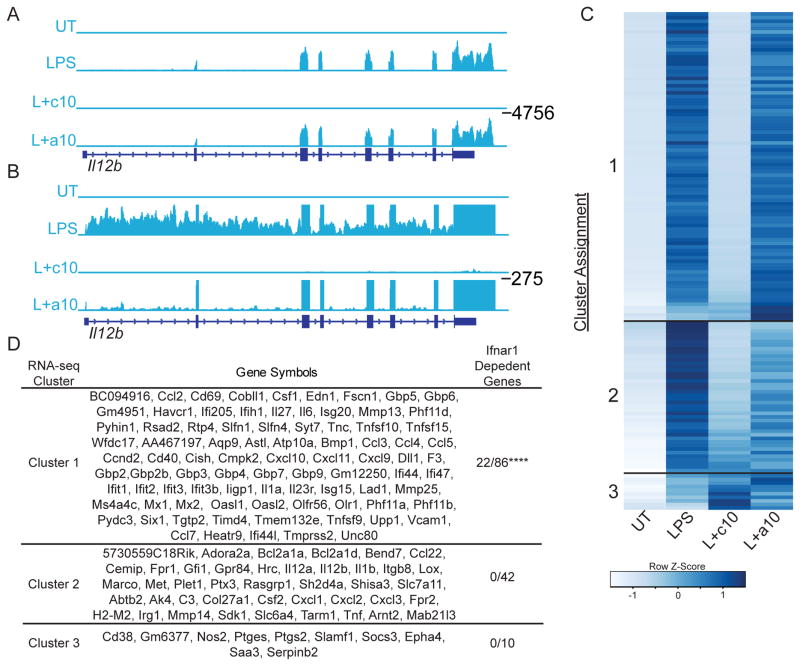

To further examine the transcriptional regulation of Il12b in response to IL-10 we sequenced ribosome-depleted total RNA from IL-10-deficient macrophages that were left untreated (UT), stimulated with LPS alone for 3.25 hours (LPS), stimulated with both LPS and IL-10 for 3.25 hours (continuous IL-10), or stimulated with LPS for 3.25 hours with IL-10 added for the last 30 minutes (acute IL-10). As expected, while we found no signal in untreated cells, we detected strong signals over the exons of Il12b following treatment with LPS (Fig. 3A) indicating the accumulation of spliced mRNA. In addition, we observed signal within the introns of Il12b (Fig. 3B) indicating the presence of pre-mRNA and therefore active transcription. In the samples treated with LPS and continuous IL-10 we saw no signal in either exonic or intronic regions indicating lack of mRNA accumulation and lack of active transcription. In contrast, in samples treated with LPS and acute IL-10 (final 30 minutes of time course) while the exonic signal exhibited little change in intensity compared to the samples treated with LPS alone, there was marked inhibition of the intronic signal. This suggests that, consistent with RT-PCR results, IL-10 rapidly inhibits transcription of Il12b.

Figure 3. Global modulation of LPS-induced gene expression by IL-10.

Il10−/− BMDM were left untreated (UT), stimulated with LPS for 3.25 h (LPS), stimulated with LPS and IL-10 together for 3.25 h (L+c10), or stimulated with LPS for 3.25 h with the addition of IL-10 for the last 30 min of the stimulation (L+a10). Total RNA was harvested and sequenced following ribosomal depletion. (A) Normalized distribution of RNA-seq reads is shown at the Il12b locus, and (B) with an expanded y-axis to better demonstrate pre-mRNA. (C) Heatmap showing k-means clustering of pre-mRNA signal for the 138 genes induced 100-fold by LPS in Il10−/− BMDM. (D) Individual genes that comprise each cluster, and the number of genes in each cluster deemed Ifnar1-dependent in Tong et al. (4). Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate significant differences. **** indicates p < 0.0001.

The recognition that RNA-seq of total RNA allowed us to observe rapid alterations of Il12b transcription by monitoring pre-mRNA suggested that we could use this technique to evaluate the transcriptional effects of IL-10 at the global level. To accomplish this, we calculated expression levels of mRNA and pre-mRNA for all protein coding genes across all 4 conditions (UT, LPS, Continuous IL-10, Acute IL-10) using Exon-Intron Split Analysis with minor alterations (25). Using this approach, we identified 138 genes whose transcription was increased at least 100-fold (FDR < 0.1) by LPS. We grouped these genes into 3 clusters using a k-means algorithm (Fig. 3C, Fig. 3D). Transcription of genes in Cluster 1 was strongly inhibited by continuous IL-10 but not by acute IL-10. Transcription of genes in Cluster 2 was strongly inhibited by both continuous and acute IL-10. Transcription of genes in Cluster 3 was induced by IL-10. Excluding genes in Cluster 3, these data indicate that continuous IL-10 inhibits the transcription of the vast majority of LPS induced genes, while acute IL-10 inhibits the transcription of a subset of these genes.

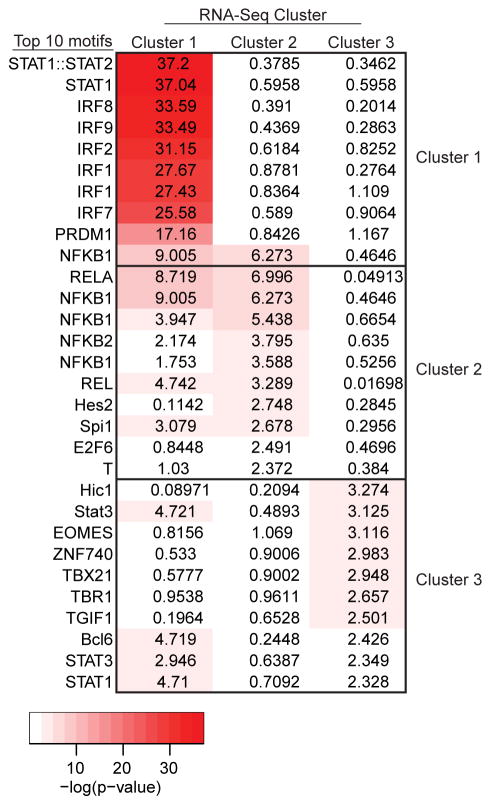

Cluster 1 is enriched for interferon-responsive secondary response genes

We have demonstrated markedly different kinetics for the transcriptional response to IL-10 in genes assigned to Cluster 1 and Cluster 2. We hypothesized that differential response could indicate alternative modes of transcriptional regulation. To examine this hypothesis, we scanned the promoters (500 bp upstream of the transcription start site) of all 138 LPS induced genes for the presence of known transcription factor binding motifs. Cluster 1 genes were significantly enriched for IRF/ISRE consensus elements, and scanning of genes in Cluster 2 identified strong enrichment for NF-κB binding without the enrichment for interferon-responsive elements observed in Cluster 1 (Fig. 4)

Figure 4. Transcription factor binding motifs in LPS-induced promoters.

PSCAN analysis of promoters for LPS induced genes clustered as in Fig. 3C. The top 10 motifs for each cluster are shown on the left. Columns represent enrichment p-values for each motif organized by cluster (top). The color intensity is proportional to the negative log of the p value.

The observation that promoters for Cluster 1 genes were significantly enriched for IRF/ISRE consensus elements suggested that this cluster could represent IFN-β induced secondary response genes. To examine this possibility further, we compared the proportion of genes in each cluster whose response to LPS required the presence of Ifnar1, based on data presented in Tong et al. (4). We found that cluster 1 was significantly enriched for genes that required the presence of Ifnar1 compared to cluster 2 (class 1 genes (22/86), cluster 2 genes (0/42), p < 10−4, see Fig. 3D).

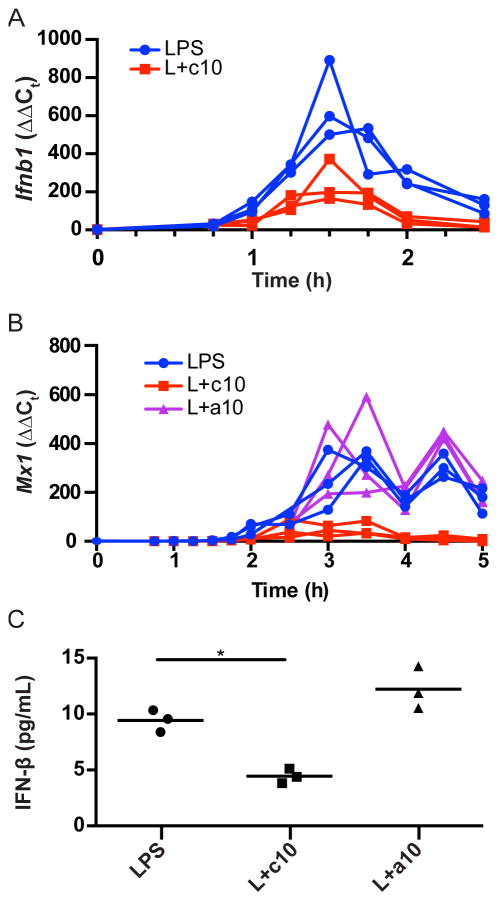

Previous results demonstrate that expression of Ifnb1 is induced early in the response to LPS, while Ifnb1 responsive genes exhibit delayed kinetics (5). Therefore, a potential explanation for the failure of acute but not continuous IL-10 to inhibit genes in cluster 1, is that rather than directly inhibiting cluster 1 genes, IL-10 is required earlier in the time course to inhibit expression of Ifnb1 itself. To examine this possibility, we evaluated expression of Ifnb1 and the IFN-induced secondary response gene Mx1 in LPS-stimulated IL-10-deficient BMDM. Ifnb1 mRNA expression peaked 90 minutes after stimulation before rapidly declining (Fig. 5A). This peak of Ifnb1 mRNA expression was followed temporally by induction of Mx1 pre-mRNA (Fig. 5B). Addition of IL-10 at the time of LPS stimulation significantly inhibited expression of Ifnb1 mRNA and Mx1 pre-mRNA (Fig. 5A, Fig. 5B), as well as secretion of IFN-β into the culture medium (Fig. 5C). In contrast, addition of IL-10 2 hours after LPS stimulation (and after the peak of Ifnb1 mRNA expression) had little effect on transcription of Mx1 or on the amount of secreted IFN-β (Fig. 5B, Fig. 5C). These results strongly suggest that Ifnb1 itself, rather than Ifnb1 responsive genes, is the primary target for IL-10. As addition of IL-10 following the peak of Ifnb1 mRNA expression does not reduce the amount of IFN-β secreted into the culture media, these results explain why addition of IL-10 2 hours and 45 minutes after LPS stimulation (acute IL-10) fails to inhibit transcription of many of the genes in Cluster 1. This is consistent with previous results demonstrating that IL-10 inhibits LPS-induced anti-viral activity, presumably IFN-β, but is unable to inhibit gene expression induced in direct response to stimulation with IFN-β (31).

Figure 5. IL-10 inhibits IFN-β production.

(A) Il10−/− BMDM were stimulated with LPS (LPS) or with LPS and IL-10 (L+c10). RNA was harvested at the indicated time points and Ifnb1 mRNA measured by RT-PCR (n=3). This experiment was performed three times. (B) Il10−/− BMDM were stimulated with LPS (LPS), stimulated with LPS and IL-10 (L+c10), or stimulated with LPS with the addition of IL-10 2 h after LPS stimulation (L+a10). RNA was harvested at the time points indicated and Mx1 mRNA was measured by RT-PCR (n=3). This experiment was performed three times. (C) Il10−/− BMDM were stimulated with LPS for 4 h (LPS), simulated with LPS and IL-10 for 4 h (L+c10), or stimulated with LPS for 4 h with with addition of IL-10 for the last 2 h (L+a10). Culture supernatants were harvested and analyzed for IFN-β protein secretion by ELISA. Significance was tested by ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (n=3). * indicates p <0.05. This experiment was performed once.

IL-10 rapidly inhibits LPS induced enhancer activation of genes in Cluster 2

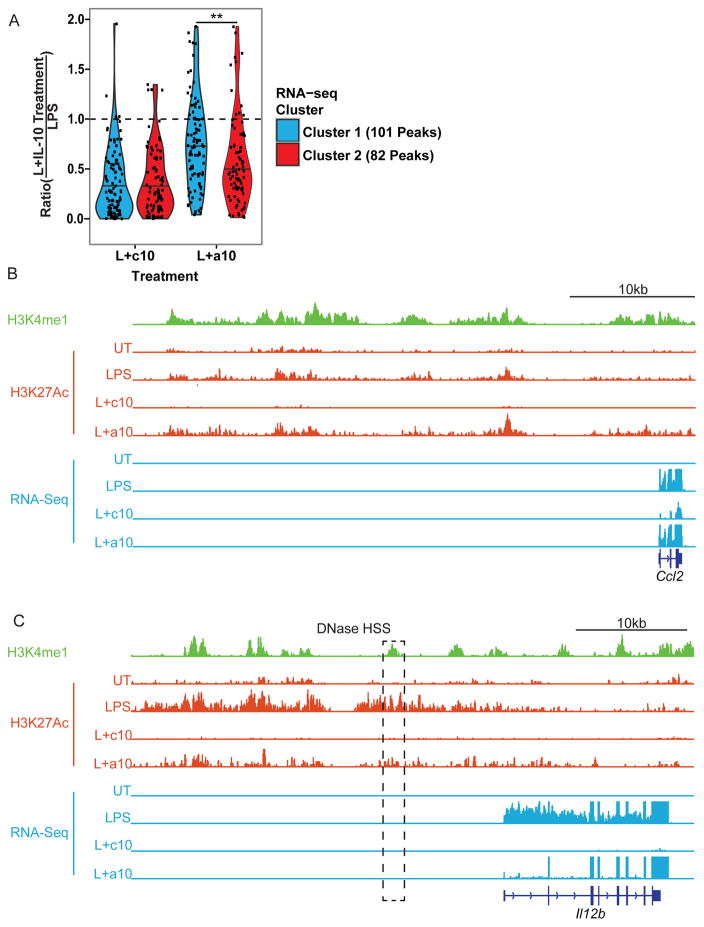

It has previously been shown that LPS induces H3K27Ac acetylation of a group of poised enhancers marked by H3K4me1 following stimulation of BMDM, but whether IL-10 inhibits LPS-induced transcription by interfering with LPS-induced enhancer acetylation is not yet known (8). Further, as we have shown above that IL-10 rapidly suppresses LPS-induced transcription of genes in Cluster 2, we were interested to determine whether rapid inhibition of transcription was associated with rapid suppression of enhancer acetylation. To study the effect of IL-10 on LPS-induced enhancer acetylation, we performed ChIP-seq for H3K27Ac in IL-10 deficient macrophages. We found that treatment with LPS for 3.25 hours significantly induced 8,417 acetylation peaks (FDR < 0.1). To identify acetylation peeks in proximity to LPS-induced genes, we filtered on LPS-induced H3K27Ac peaks that were located within 50 kb upstream of the transcriptional start site, as well as within 50 kb downstream of the transcription termination site of Cluster 1 and 2 genes. We found that many of these peaks overlapped with sites of H3K4me1 defined in Ostuni et al., indicating that these peaks likely represented bona fide enhancers (data not shown) (8). We found that 49/86 genes in Cluster 1 were associated with at least one LPS-induced acetylation peak, and 34/42 genes in Cluster 2 were associated with at least one LPS-induced peak. Next, we compared the magnitude of these H3K27ac peaks in BMDM stimulated with LPS alone to those stimulated with both LPS and continuous IL-10, or LPS and acute IL-10. Treatment with continuous IL-10 markedly reduced H3K27Ac at peaks associated with genes from both Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 (Fig. 6A). However, following treatment with acute IL-10, H3K27ac was significantly lower at peaks associated with genes from Cluster 2 than at peaks associated with genes from Cluster 1 (p-value <0.01 by Mann-Whitney test, Fig. 6A). Examples of Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 enhancers are shown in Fig. 6B and Fig. 6C, respectively. Interestingly this analysis identified a peak inhibited by acute IL-10 that encompasses a DNAse hypersensitivity site 10 kb upstream of Il12b that has previously been demonstrated in a reporter assay to exhibit enhancer activity (Fig. 6C) (22). These data indicate that IL-10 can rapidly suppress enhancers associated with genes in Cluster 2, suggesting that the ability of IL-10 to rapidly suppress transcription of genes in Cluster 2 may be based on suppression of enhancer function.

Figure 6. IL-10 causes rapid changes in enhancer H3K27Ac status.

Il10−/− BMDM were left untreated (UT), stimulated with LPS for 3.25 h (LPS), stimulated with LPS and IL-10 together for 3.25 h (L+c10), or stimulated with LPS for 3.25 h with the addition of IL-10 for the last 30 min of the stimulation (L+a10). Chromatin was harvested and ChIP-seq was performed with an antibody specific for H3K27Ac. (A) The H3K27Ac signal intensity was determined for each LPS induced acetylation peak within 50 kb upstream or downstream of Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 genes, and a ratio between the signal with LPS alone and with continuous or acute IL-10 treatment was calculated for each peak. These ratios are represented on a violin plot where each dot represents an individual enhancer and the width of the contours represent a smoothened density of these values. The horizontal line within each violin plot indicates the median value. Significance tested for by the Mann-Whitney test. ** indicates p < 0.01. (B–C) Representative locus shown for Cluster 1 gene ccl2 (B) and Cluster 2 gene Il12b (C). H3K4me1 ChIP-seq data from Ostuni et al. normalized to reads per million (green) (8). H3K27Ac ChIP-seq data from macrophages treated as in Fig. 6A normalized to the depth of the least sequenced library (red). Normalized RNA-seq data from macrophages treated as in Fig. 3C (blue). The boxed region in (C) represents the Il12b -10 kb enhancer previously described in Zhou et al. (22).

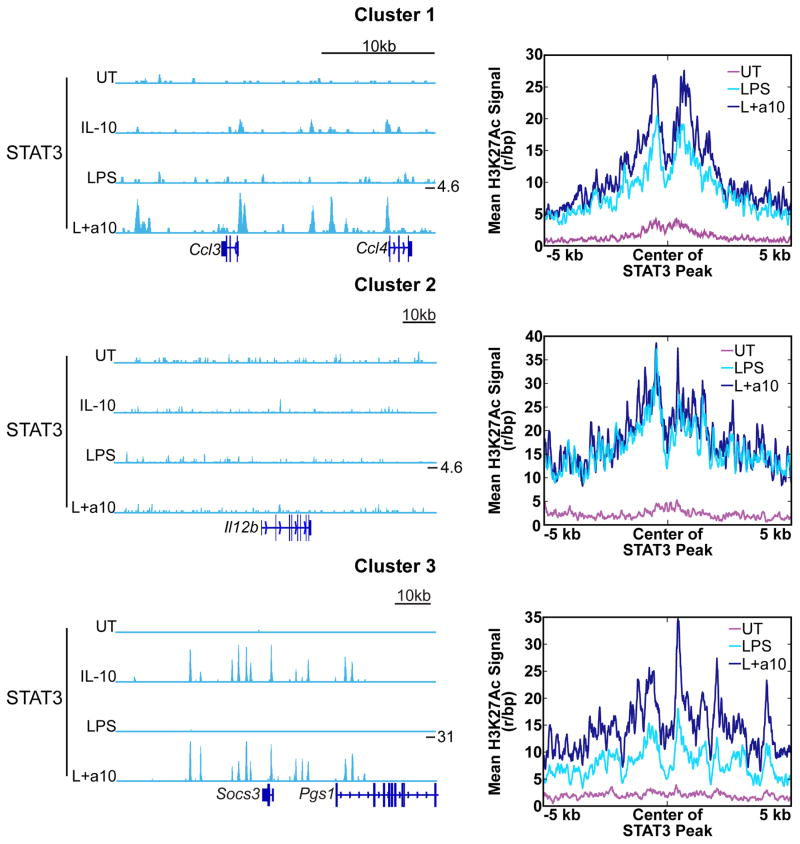

IL-10 mediated inhibition of Cluster 2 genes is not associated with direct STAT3 binding

STAT3 is required for IL-10-mediated inhibition of LPS-induced inflammatory gene expression (11). However, the function of STAT3 in the inhibitory process in not clear. STAT3 is a transcriptional activator and binding sites for STAT3 in the proximity of genes inhibited by IL-10 have not previously been identified (13). This has led to the hypothesis that STAT3-dependent induction of inhibitory factors mediates the inhibitory function of IL-10. However, the rapidity with which IL-10 is able to inhibit genes in Cluster 2 argues that dependence on new protein synthesis is unlikely, although certainly not impossible. Therefore, we sought to consider alternative mechanisms that might explain rapid STAT3-mediated inhibition. One possibility is that STAT3 binding directly suppresses activation of enhancers associated with genes in Cluster 2. To address this possibility, we performed ChIP-seq with an anti-STAT3 antibody to identify STAT3 binding sites. After treatment of IL10-deficient BMDM with IL-10 alone for 30 minutes we identified 31 STAT3 binding peaks within 50 kb upstream of the top 138 LPS induced genes, but strikingly we found an additional 54 peaks within these regions when BMDM were stimulated with LPS prior to addition of IL-10. This indicates that prior LPS treatment reveals IL-10-induced STAT3 binding sites that were not present in unstimulated cells. Interestingly, virtually all identified STAT3 binding sites were located within H3K4me1 peaks, suggesting that STAT3 binds to enhancers. As anticipated, we found strong STAT3 binding near Cluster 3 genes induced by IL-10, such as Socs3 (Fig. 7, bottom left), and IL-10 induced an increase in average mean acetylation at STAT3 binding sites associated with genes in Cluster 3, consistent with enhancer activation (Fig. 7, bottom right). Interestingly, prior LPS treatment revealed STAT3 binding sites near Cluster 1 genes that were not present with IL-10 treatment alone, and these sites also demonstrated an increase in mean acetylation in response to IL-10, although these peaks had a much weaker STAT3 signal relative to Cluster 3 gene peaks (Fig. 7). Lastly, IL-10 had little effect on mean acetylation at STAT3 binding peaks located within the 50 kb upstream of genes in Cluster 2, and STAT3 binding sites were not identified in the 50 kb upstream of Il12b (Fig. 7). Thus, there is little evidence that STAT3 binding directly suppresses activation of LPS-induced enhancers. These results raise the possibility that IL-10-induced STAT3 may have an inhibitory function that does not depend on direct DNA binding.

Figure 7. STAT3 binding is associated with gene induction.

Left, Il10−/− BMDM were left untreated (UT), stimulated with IL-10 for 30 min (IL-10), stimulated with LPS for 3.25 h (LPS), or stimulated with LPS for 3.25 h with the addition of IL-10 for the last 30 min of the stimulation (LPS+a10). Chromatin was harvested and ChIP-seq performed for STAT3. STAT3 ChIP-seq signal in reads per million shown for representative locus for Cluster 1 genes Ccl3 and Ccl4 (top), Cluster 2 gene Il12b (middle), and a Cluster 3 gene Socs3 (bottom). Y-axis maximum for each locus marked in L+a10 track. Right, mean H3K27Ac Chip-Seq signal intensities from Il10−/− BMDM treated as in Fig. 6 for STAT3 peak centers identified within 50 kb upstream of genes in each cluster. Signal is normalized by library size to reads per base pair.

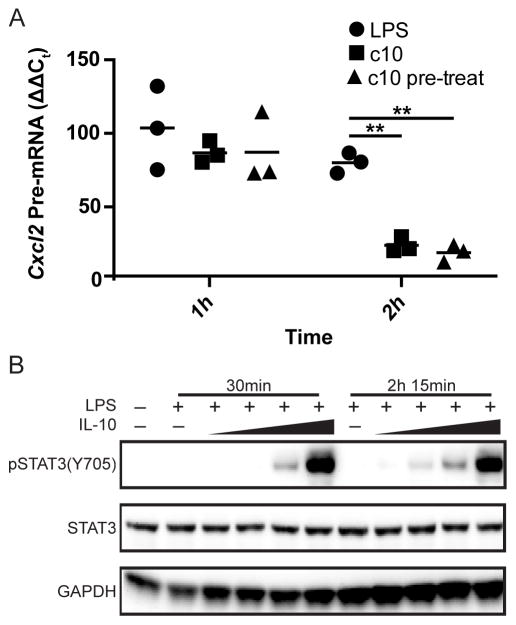

Cluster 2 gene Cxcl2 is inhibited during the secondary response phase to LPS

Inspection of genes in Cluster 2 revealed many, including Il12b, that have been previously characterized as secondary response genes in LPS stimulated BMDM. However there were also many genes that have been characterized as primary response genes (Cxcl1, Cxcl2) (Fig. 3D) (4). As we had only examined the transcriptional effects of IL-10 at relatively late time points (105 and 165 minutes following LPS stimulation), we wondered whether the ability of IL-10 to rapidly inhibit transcription was operational at an early time point following LPS stimulation. To evaluate this issue, we compared induction of Cxcl2 transcription in IL-10-deficient macrophages stimulated with LPS alone, both LPS and IL-10, or stimulated with IL-10 for 1 hour prior to stimulation with LPS. As predicted, LPS rapidly induced Cxcl2 pre-mRNA within 1h hour of stimulation. Surprisingly, addition of IL-10 at the time of LPS stimulation or addition 1 hour prior to LPS stimulation had little influence on Cxcl2 pre-mRNA at 1h post LPS stimulation, although significant suppression was observed at 2h post LPS stimulation (Fig. 8A). This difference was not caused by an inability of macrophages to respond to IL-10 prior to LPS stimulation as similar induction of STAT3 Y705 phosphorylation was observed when cells were treated with IL-10 in parallel with LPS or at later time points (Fig. 8B). These results strongly suggest that IL-10 interferes with a process that is unique to the secondary phase of the response to LPS.

Figure 8. The ability of IL-10 to inhibit Cxcl2 transcription exhibits a delay following LPS stimulation.

(A) Il10−/− BMDM were stimulated with LPS alone, treated with IL-10 concurrently with LPS stimulation, or pre-treated with IL-10 for 1 h prior to LPS stimulation. RNA was harvested at 1h and 2h after LPS stimulation. Cxcl2 pre-mRNA levels were measured by RT-PCR and displayed relative to levels in unstimulated cells. Significance was tested by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (n=3). ** indicates p <0.01. This experiment was performed three times. (B) Il10−/− BMDM were stimulated with LPS for 30 min and 2.25 h with or without the addition of IL-10 in increasing doses of 0.0625 ng/mL, 0.25 ng/mL, 1 ng/mL, and 4 ng/mL for the last 30 min of the time course. Cell extracts were prepared and assayed for pSTAT3 (Y705) or total STAT3 by western blot. This experiment was performed twice.

DISCUSSION

Here we have investigated the kinetics of IL-10 mediated inhibition of LPS-induced gene expression. We have found that IL-10 rapidly inhibits LPS-induced transcription of Il12b in WT cells and that addition of IL-10 to IL-10-deficient macrophages leads to the rapid termination of transcription. Using a novel approach to evaluate global changes in transcription of LPS-induced genes we have found that while administration of IL-10 at the time of LPS-stimulation of IL-10-deficient BMDM had broad inhibitory effects, only a subset of these genes (Cluster 2) were rapidly inhibited when IL-10 was given 2.75 hours after LPS stimulation. Rapid inhibition of transcription of genes in cluster 2 was accompanied by rapid inactivation of putative cis-acting enhancer-like elements, suggesting that IL-10 was acutely influencing enhancer function. Taken together, these results indicate that rapid inhibition of enhancer function may be a key mechanism of IL-10 mediated inhibition.

It has previously been demonstrated that there is a delay in Il12b expression following LPS stimulation of WT BMDM (21), but we were quite surprised to find that the period of active Il12b transcription was extremely short due to rapid inhibition by endogenously produced IL-10. Despite the short period of active transcription, Il12b mRNA remained present for hours after transcription had terminated, and small differences in the timing of addition of exogenous IL-10 led to large differences in the amount of IL-12 p40 protein measured in the supernatant 24 hours after stimulation. As we expect that similar kinetics will be observed in human cells, these results emphasize that relative small variances in the timing of induction of Il12b transcription or production of IL-10 between individuals could lead to quite large differences in overall levels of Il-12 p40 secretion and biological function. Whether this is an important factor controlling differences in immune and inflammatory responses between individuals remains to be determined.

While global induction of LPS-induced genes has been widely evaluated (2, 4, 11), the analysis presented here using exon intron split analysis of total RNA-seq data has provided a unique perspective on the kinetics of transcription termination, that cannot be fully appreciated from evaluation of mRNA levels alone. This simple method to estimate transcription rates relies on sequencing of ribosome-depleted total RNA, and does not require purification of chromatin as is required for nascent transcript RNA-seq, or immunoprecipitation of chromatin that is required for PolII ChIP-seq. Further this method simultaneously provides quantification of mRNA and relative rates of active transcription. Application of this technique to other systems where strict temporal regulation of gene expression is critical, could reveal dynamic regulation that has not been observed previously.

Use of the the exon-intron split analysis allowed us to determine that while transcription of virtually all LPS-induced genes is inhibited when IL-10 is added at the time of LPS stimulation, transcription of only a subset is rapidly inhibited when IL-10 is administered to IL-10-deficient macrophages 2 hours and 45 minutes following LPS stimulation (Cluster 2). Although we do not yet understand the biochemical basis for IL-10-mediated inhibition, we have demonstrated the rapid loss of H3K27 acetylation at LPS-induced enhancer elements associated with Cluster 2 genes following IL-10 treatment. This suggests that the mechanism of IL-10-mediated inhibition involves rapid modulation of LPS-induced enhancer function. It has previously been shown that IL-10 can reduce total H4 acetylation at the Il12b promoter and potentially enhance the function of HDACs, but the exact nature of IL-10 mediated alterations in chromatin acetylation have not been previously described at the genome-wide level (21). Interestingly, our observation that IL-10 reverses LPS-induced H3K27 acetylation at many putative enhancer elements, raises the possibility that previous genome-wide evaluation of LPS-induced enhancer elements may have significantly underestimated their number, as these studies were performed on WT macrophages at time points where one would predict the presence of significant amounts of IL-10 in the culture supernatant (8). While, we believe that rapid modulation of enhancer function by IL-10 is a key pathway mediating suppression of genes in Cluster 2, an important limitation to these conclusions is the variability noted in the response of genes in this cluster to IL-10. This variability may indicate the presence of alternative mechanisms of suppression for selected genes in this cluster.

While evidence from the exon split analysis suggests rapid inhibitory function for IL-10, we were quite surprised that addition of IL-10 at the time of LPS stimulation did not inhibit the initial transcriptional of an early response gene, Cxcl2, despite clear evidence for suppression at later time points. While we initially considered the possibility that this was evidence for a delayed effect of IL-10, we do not believe that this is the case, as administration of IL-10 1 hour prior to LPS stimulation did not reduce the time to the point where inhibition was first observed. This delay was not based on a requirement for LPS to induce components of the IL10R apparatus, as exogenous IL-10 activated STAT3 even in the absence of prior LPS stimulation. Thus, we prefer the possibility that IL-10 is unable to inhibit the first wave of LPS-induced gene expression, but rather functions at least in part by inhibiting an LPS-induced positive regulator that is required for the induction of a subset of delayed response genes and the sustained expression of immediate response genes. One potential candidate for this positive regulator is IκBζ, which is induced in response to LPS and is required for LPS-induced expression of Il12b (7). Interestingly is has been reported that IκBζ interacts with activated STAT3 (32), but whether this interaction is necessary for IL-10 mediated suppression remains to be determined.

It is tempting to speculate that genes inhibited by continuous but not acute IL-10 (Cluster 1) are inhibited more slowly than genes in Cluster 2, however, we believe that our data supports a model in which a substantial proportion of genes in Cluster 1 are in fact responding to secreted IFN-β, as Cluster 1 is strongly enriched for LPS-induced genes that require the presence of the type-1 interferon receptor (4). While we have confirmed that IFN-β is inhibited by IL-10, peak expression of IFN-β occurs at 90 minutes, thus explaining why IL-10 administration at the time of stimulation, but not after 2 hours and 45 minutes inhibits Cluster 1 genes. Interestingly, previous work has suggested that LPS-induced IFN-β expression may have a role in the regulation of IL-10 itself (33). However, it is important to note that IFN-β priming of IL-10 expression can’t explain results obtained in these experiments as BMDM used in these experiments lack endogenous IL-10. An important caveat to our conclusions is that select secondary response genes within Cluster 1 are independent of IFNAR, and therefore inhibition of Ifnb1 expression is unlikely responsible for IL-10 mediated inhibition of all genes within Cluster 1. However, as several of these INFAR-independent secondary responses genes identified in Cluster 1 including IL-6 and IL-27 are TRIF-dependent, it may be that a common IL-10-mediated pathway that inhibits TRIF function plays an important role in inhibiting genes in this cluster (4). Identifying the IL-10 responsive mediators of these effects could have important implications for understanding the overall regulation of the response to LPS.

It is somewhat paradoxical that genes in Cluster 1 only exhibit responsiveness to IL-10 suppression at times points prior to robust secretion of endogenous IL-10 by LPS-stimulated macrophages. However, there are multiple sources of IL-10 in vivo, including regulatory T cells, and it has been demonstrated that non-macrophage sources of IL-10 are essential to prevent inflammatory diseases such as IBD (34). While it is difficult to completely define when a macrophage is first exposed to IL-10 in vivo, we believe that it is plausible that macrophages at sites of pathogen interface such as the intestine are exposed to IL-10 at varying times relative to the receipt of an inflammatory stimuli. The critical window of IL-10 responsiveness for genes in Cluster 1, revealed by our study, could have a central role in defining how macrophages respond based on temporal variability in receipt of the IL-10 signal.

What then have we learned regarding the mechanism of IL-10 mediated inhibition? Results from this study suggest that inhibition is based on the rapid suppression of active transcription and deacetylation of LPS-induced enhancer-like elements. This mechanism extends to most LPS-induced genes but is not operational without prior LPS stimulation. The rapid nature of IL-10-mediated suppression would seem to indicate that STAT3-driven induction of a secondary transcriptional inhibitor is unlikely (although certainly not impossible), given that inhibition of active transcription can be observed within 15 minutes of IL-10 treatment. While experiments employing the protein synthesis inhibitor cyclohexamide have suggested that IL-10-mediated inhibition requires new protein synthesis, in our hands cyclohexamide treatment rapidly inhibits ongoing transcription of Il12b (data not shown), making it quite difficult to discern any additional inhibitory effects of IL-10. Thus, we believe that the question of whether IL-10-mediated inhibition requires new protein synthesis remains open. Alternative possibilities to explain IL-10-mediated inhibition that could potentially function on the more rapid time scale observed in this study include the induction of an inhibitory RNA species, or a direct inhibitory function for STAT3. However, STAT3 ChIP-seq failed to uncover IL-10-induced STAT3 binding sites associated with suppression of LPS-induced enhancer activation. Thus, further directed experiments geared towards understanding IL-10-mediated signaling pathways that rapidly inhibit transcription will be required. Delineating these mechanisms could have important implications for understanding the basis for inflammatory disease, as well as the development of novel therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Funding sources: NIH R01-AI100114 (BHH); DCDO was supported by grant #2015/02610-6, Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPSEP). CMM is supported by NIH 5T32HD040128. SBS is supported by NIH DK034854 and the Wolpow Family Chair in IBD Treatment and Research. SBS and BHH are supported the Helmsley Charitable Trust.

Author Contributions:

E.A.C. designed and performed experiments, collected and analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; D.C.D.O., and C.M.M designed and performed experiments, and collected and analyzed data; S.B.S. provided critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content; B.H.H designed experiments, supervised experimentation and data collection, and wrote the manuscript.

Data Availability:

All data are accessible through the gene expression omnibus accession number GSE86170 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank.

References

- 1.Amit I, Garber M, Chevrier N, Leite AP, Donner Y, Eisenhaure T, Guttman M, Grenier JK, Li W, Zuk O, Schubert LA, Birditt B, Shay T, Goren A, Zhang X, Smith Z, Deering R, McDonald RC, Cabili M, Bernstein BE, Rinn JL, Meissner A, Root DE, Hacohen N, Regev A. Unbiased Reconstruction of a Mammalian Transcriptional Network Mediating Pathogen Responses. Science. 2009;326:257–263. doi: 10.1126/science.1179050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatt DM, Pandya-Jones A, Tong AJ, Barozzi I, Lissner MM, Natoli G, Black DL, Smale ST. Transcript dynamics of proinflammatory genes revealed by sequence analysis of subcellular RNA fractions. Cell. 2012;150:279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hargreaves DC, Horng T, Medzhitov R. Control of Inducible Gene Expression by Signal-Dependent Transcriptional Elongation. Cell. 2009;138:129–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tong AJ, Liu X, Thomas BJ, Lissner MM, Baker MR, Senagolage MD, Allred AL, Barish GD, Smale ST. A Stringent Systems Approach Uncovers Gene-Specific Mechanisms Regulating Inflammation. Cell. 2016;165:165–179. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doyle SE, Vaidya SA, O’Connell R, Dadgostar H, Dempsey PW, Wu TT, Rao G, Sun R, Haberland ME, Modlin RL, Cheng G. IRF3 Mediates a TLR3/TLR4-Specific Antiviral Gene Program. Immunity. 2002;17:251–263. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00390-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hildebrand DG, Alexander E, Horber S, Lehle S, Obermayer K, Munck NA, Rothfuss O, Frick JS, Morimatsu M, Schmitz I, Roth J, Ehrchen JM, Essmann F, Schulze-Osthoff K. IkappaBzeta is a transcriptional key regulator of CCL2/MCP-1. J Immunol. 2013;190:4812–4820. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto M, Yamazaki S, Uematsu S, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Kuwata H, Takeuchi O, Takeshige K, Saitoh T, Yamaoka S, Yamamoto N, Yamamoto S, Muta T, Takeda K, Akira S. Regulation of Toll/IL-1-receptor-mediated gene expression by the inducible nuclear protein IkappaBzeta. Nature. 2004;430:218–222. doi: 10.1038/nature02738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ostuni R, Piccolo V, Barozzi I, Polletti S, Termanini A, Bonifacio S, Curina A, Prosperini E, Ghisletti S, Natoli G. Latent enhancers activated by stimulation in differentiated cells. Cell. 2013;152:157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghisletti S, Barozzi I, Mietton F, Polletti S, De Santa F, Venturini E, Gregory L, Lonie L, Chew A, Wei CL, Ragoussis J, Natoli G. Identification and characterization of enhancers controlling the inflammatory gene expression program in macrophages. Immunity. 2010;32:317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heintzman ND, Stuart RK, Hon G, Fu Y, Ching CW, Hawkins RD, Barrera LO, Van Calcar S, Qu C, Ching KA, Wang W, Weng Z, Green RD, Crawford GE, Ren B. Distinct and predictive chromatin signatures of transcriptional promoters and enhancers in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:311–318. doi: 10.1038/ng1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang R, Patel D, Morris JJ, Rutschman RL, Murray PJ. Shaping gene expression in activated and resting primary macrophages by IL-10. J Immunol. 2002;169:2253–2263. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber-Nordt RM, Riley JK, Greenlund AC, Moore KW, Darnell JE, Schreiber RD. Stat3 recruitment by two distinct ligand-induced, tyrosine-phosphorylated docking sites in the interleukin-10 receptor intracellular domain. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1996;271:27954–27961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hutchins AP, Poulain S, Miranda-Saavedra D. Genome-wide analysis of STAT3 binding in vivo predicts effectors of the anti-inflammatory response in macrophages. Blood. 2012;119:e110–119. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-381483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuwata H, Watanabe Y, Miyoshi H, Yamamoto M, Kaisho T, Takeda K, Akira S. IL-10-inducible Bcl-3 negatively regulates LPS-induced TNF-α production in macrophages. Blood. 2003;102:4123–4129. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi T, Steinbach EC, Russo SM, Matsuoka K, Nochi T, Maharshak N, Borst LB, Hostager B, Garcia-Martinez JV, Rothman PB, Kashiwada M, Sheikh SZ, Murray PJ, Plevy SE. NFIL3-deficient mice develop microbiota-dependent, IL-12/23-driven spontaneous colitis. J Immunol. 2014;192:1918–1927. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray PJ. The primary mechanism of the IL-10-regulated antiinflammatory response is to selectively inhibit transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8686–8691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500419102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajasingh J, Bord E, Luedemann C, Asai J, Hamada H, Thorne T, Qin G, Goukassian D, Zhu Y, Losordo DW, Kishore R. IL-10-induced TNF-alpha mRNA destabilization is mediated via IL-10 suppression of p38 MAP kinase activation and inhibition of HuR expression. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2006;20:2112–2114. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6084fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biswas R, Datta S, Gupta JD, Novotny M, Tebo J, Hamilton TA. Regulation of chemokine mRNA stability by lipopolysaccharide and IL-10. J Immunol. 2003;170:6202–6208. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kontoyiannis D, Kotlyarov A, Carballo E, Alexopoulou L, Blackshear PJ, Gaestel M, Davis R, Flavell R, Kollias G. Interleukin-10 targets p38 MAPK to modulate ARE-dependent TNF mRNA translation and limit intestinal pathology. Embo j. 2001;20:3760–3770. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.14.3760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aste-Amezaga M, Ma X, Sartori A, Trinchieri G. Molecular mechanisms of the induction of IL-12 and its inhibition by IL-10. J Immunol. 1998;160:5936–5944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobayashi T, Matsuoka K, Sheikh SZ, Russo SM, Mishima Y, Collins C, deZoeten EF, Karp CL, Ting JP, Sartor RB, Plevy SE. IL-10 regulates Il12b expression via histone deacetylation: implications for intestinal macrophage homeostasis. J Immunol. 2012;189:1792–1799. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou L, Nazarian AA, Xu J, Tantin D, Corcoran LM, Smale ST. An inducible enhancer required for Il12b promoter activity in an insulated chromatin environment. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:2698–2712. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00788-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erdman SE, V, Rao P, Poutahidis T, Ihrig MM, Ge Z, Feng Y, Tomczak M, Rogers AB, Horwitz BH, Fox JG. CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory lymphocytes require interleukin 10 to interrupt colon carcinogenesis in mice. Cancer research. 2003;63:6042–6050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomczak MF, Gadjeva M, Wang YY, Brown K, Maroulakou I, Tsichlis PN, Erdman SE, Fox JG, Horwitz BH. Defective activation of ERK in macrophages lacking the p50/p105 subunit of NF-kappaB is responsible for elevated expression of IL-12 p40 observed after challenge with Helicobacter hepaticus. J Immunol. 2006;176:1244–1251. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaidatzis D, Burger L, Florescu M, Stadler MB. Analysis of intronic and exonic reads in RNA-seq data characterizes transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation. Nature biotechnology. 2015;33:722–729. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramirez F, Ryan DP, Gruning B, Bhardwaj V, Kilpert F, Richter AS, Heyne S, Dundar F, Manke T. deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic acids research. 2016;44:W160–165. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Meth. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross-Innes CS, Stark R, Teschendorff AE, Holmes KA, Ali HR, Dunning MJ, Brown GD, Gojis O, Ellis IO, Green AR, Ali S, Chin SF, Palmieri C, Caldas C, Carroll JS. Differential oestrogen receptor binding is associated with clinical outcome in breast cancer. Nature. 2012;481:389–393. doi: 10.1038/nature10730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang P, Wu P, Siegel MI, Egan RW, Billah MM. IL-10 inhibits transcription of cytokine genes in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Immunol. 1994;153:811–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipson KE, Baserga R. Transcriptional activity of the human thymidine kinase gene determined by a method using the polymerase chain reaction and an intron-specific probe. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:9774–9777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.9774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varano B, Fantuzzi L, Puddu P, Borghi P, Belardelli F, Gessani S. Inhibition of the constitutive and induced IFN-beta production by IL-4 and IL-10 in murine peritoneal macrophages. Virology. 2000;277:270–277. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu Z, Zhang X, Yang J, Wu G, Zhang Y, Yuan Y, Jin C, Chang Z, Wang J, Yang X, He F. Nuclear protein IkappaB-zeta inhibits the activity of STAT3. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2009;387:348–352. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang EY, Guo B, Doyle SE, Cheng G. Cutting edge: involvement of the type I IFN production and signaling pathway in lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-10 production. J Immunol. 2007;178:6705–6709. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubtsov YP, Rasmussen JP, Chi EY, Fontenot J, Castelli L, Ye X, Treuting P, Siewe L, Roers A, Henderson WR, Jr, Muller W, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cell-derived interleukin-10 limits inflammation at environmental interfaces. Immunity. 2008;28:546–558. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]