Abstract

Toxic amyloid beta oligomers (AβOs) are known to accumulate in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and in animal models of AD. Their structure is heterogeneous, and they are found in both intracellular and extracellular milieu. When given to CNS cultures or injected ICV into non-human primates and other non-transgenic animals, AβOs have been found to cause impaired synaptic plasticity, loss of memory function, tau hyperphosphorylation and tangle formation, synapse elimination, oxidative and ER stress, inflammatory microglial activation, and selective nerve cell death. Memory loss and pathology in transgenic models are prevented by AβO antibodies, while Aducanumab, an antibody that targets AβOs as well as fibrillar Aβ, has provided cognitive benefit to humans in early clinical trials. AβOs have now been investigated in more than 3000 studies and are widely thought to be the major toxic form of Aβ. Although much has been learned about the downstream mechanisms of AβO action, a major gap concerns the earliest steps: How do AβOs initially interact with surface membranes to generate neuron-damaging transmembrane events? Findings from Ohnishi et al (PNAS 2005) combined with new results presented here are consistent with the hypothesis that AβOs act as neurotoxins because they attach to particular membrane protein docks containing Na/K ATPase-α3, where they inhibit ATPase activity and pathologically restructure dock composition and topology in a manner leading to excessive Ca++ build-up. Better understanding of the mechanism that makes attachment of AβOs to vulnerable neurons a neurotoxic phenomenon should open the door to therapeutics and diagnostics targeting the first step of a complex pathway that leads to neural damage and dementia.

Keywords: Abeta oligomers, Alzheimer’s, sodium-potassium ATPase, NaK ATPase, toxicity, synapse, spine loss, receptor

The AβO Hypothesis -- A Mechanism with Prime Targets for AD Therapeutics

The amyloid beta oligomer (AβO) hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), introduced in 1998 [1], says that dementia is the consequence of neural damage instigated by soluble, toxic AβOs. Earlier investigations had found AβOs in AD brain extracts [2], but their toxicity was not apparent. Discovery of methods to make soluble AβOs without contaminating fibrils [3] opened the door to brain slice experiments that revealed AβOs are potent CNS neurotoxins, capable of rapidly inhibiting hippocampal LTP at low doses and, with longer exposures, causing cell death in vulnerable neuron populations [1]. Cell-selective impact was evident, as only subpopulations of neurons were lost. Death, moreover, was signaling-dependent, as knockout of the protein tyrosine kinase Fyn was neuroprotective. AβOs did not act as “molecular shrapnel.” These were toxins that were cell-selective and required signal transduction. The mechanism was hypothesized to depend on the interaction of AβOs with toxin receptors, a hypothesis still of current interest and one that will be discussed later in this article.

Toxic AβOs are now known to be salient features of AD neuropathology. They accumulate early in the disease process, in humans and in transgenic (Tg) animal AD models [4,5]. In many Tg models, including hAPP [6], 3xTg-AD [7], APP-Tg E693Δ [8], Tg McGill-Thy-1-APP [9], APP-Tg E693Q “Dutch” [10], and 5xFAD (unpublished data from WL Klein and R Vassar labs), AβOs accumulate before the emergence of plaques. Detection is possible using oligomer-specific antibodies for histology and sensitive dot immunoblots and sandwich ELISAs for solution assays [11]. Table 1 shows the affinities of commonly used research antibodies, several of which are oligomer-specific. In some cases, as in the Osaka mutation [12], toxic AβOs accumulate without amyloid plaques, which are absent despite an otherwise full complement of AD pathology. The plaque-free build-up of AβOs and other AD pathology is recapitulated in a mouse model of the Osaka mutation [8]. This suggests that the old definition of AD as dementia with plaques and tangles may be misdirected. Amyloid plaques are not required for dementia; toxic AβOs are.

Table 1. NU-series antibodies that selectively bind AβOs. AβO-antibodies commonly used by our lab comprise NU 1, 2, and 4 [11]. They have low affinity for Aβ monomers and fibrils. Their affinities for our AβO preparations were determined here using an indirect ELISA with 20 pmols of AβOs per well (total Aβ monomer equivalents). For comparison, affinities were determined for other commonly used antibodies that have varying degrees of selectivity for monomers, fibrils, and different forms of AβOs.

| Ab | EC50 (ug/mL Ab) |

| NU2 | 0.15 |

| NU1 | 0.29 |

| NU4 | 0.40 |

| 6E10 | 0.67 |

| 4G8 | 1.85 |

| OC | 4.66 |

| A11 | No signal |

| MOAB-1 | No signal |

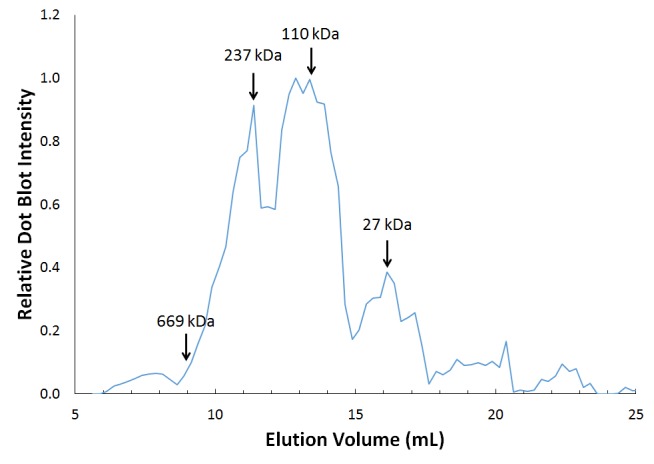

The subunits of synthetic AβOs in most instances are not covalently bonded, and assembly states of AβOs are heterogeneous. While dynamic, the major assembly states are stable enough to be detected. Figure 1, e.g., shows an FPLC-SEC profile of synthetic AβOs with a peak near 110 kDa and another at about twice this mass. AβOs are larger in aqueous buffers than in buffers with detergents. In Western blots, synthetic AβOs typically break down to monomers and very low MW AβOs. Breakdown is reduced by crosslinking procedures, particularly for smaller species [13]. Larger species are stabilized by extended incubation [14]. It is likely that the brain environment modifies the oligomeric state, as the inflammatory molecule levuglandin stabilizes larger species [15], and pyroglutamylated Aβ, for example, is common in brain-derived AβOs. 2D gel analysis shows structural homology between AβOs in aqueous extracts of AD-affected brain and toxic AβOs made in vitro. Prominent dodecamers (54 kDa) are present in AD and synthetic preparations but not control brain [16]. A dodecamer found in Western blots, referred to as Aβ*56, accumulates in Tg2576 mouse brain roughly at the onset of memory dysfunction [17]. 24mers also have been found in SDS extracts of AD affected human and animal brain tissue [16,18].

Figure 1.

Prominent peaks in FPLC-SEC of synthetic AβOs (110 kDa and 237 kDa). Preparations of AβOs were made by incubating 200 nM Aβ monomer in F12 and centrifuging to remove traces of fibrils according to published protocols [22]. Chromatography was as described [72]. Fractions were collected off the column and immunoreactivity to NU2 determined via dot immunoblotting. Mass of 110 kDa corresponds approximately to a 24mer of Aβ42.

The Aβ42 peptide is now widely used for experimentation because it is more closely associated with AD pathology than is Aβ40 [19]. The original fibril-free preparation of toxic AβOs was made using clusterin as a chaperone and also by using very low Aβ42 concentrations sans clusterin [1]. Because of the expense of clusterin, most preparations currently are made in simple buffers. Oligomerization is highly influenced by concentration, temperature, buffer, and presence of non-monomeric seeds; even vortexing affects the outcome. It also has become clear that there are naturally-occurring alternative pathways of self-assembly. These alternative pathways produce relatively stable toxic oligomers greater than 50 kDa (on Western blots) and oligomers that assemble further into fibrillar Aβ [14]. The products have been referred to as Type 1 and Type 2 oligomers, respectively [20]. A variety of preparations have been developed and used for experimentation, including use of pyroglutamylated N-terminal to generate highly toxic AβOs [21]. A summary of preparations and structures can be found in our recent review [22]. Protocols for preparation and use of AβOs typically used in our laboratory can be accessed at our home page (www.kleinlab.org).

Synthetic and brain-derived AβO preparations cause a spectrum of AD-like, cell-specific neural damage. In CNS cultures, e.g., neurons with bound AβOs manifest AD-type phospho-tau, whereas neurons without bound AβOs show much less of this phospho-tau [23]. Overall evidence strongly supports the role of AβOs in instigating tau pathology [24], which mediates some of the AβO toxic impact [24]. Because APP transgenes accelerate propagation of tau pathology in Tg mice [25,26], we hypothesize it is likely that AβOs may likewise play a role in this aspect of tau pathology. ICV injections of AβOs into wildtype animals likewise evoke AD neuropathology, including non-human primates [27]. Tg animals producing AβOs manifest equivalent neural damage [8,9,28]. Table 2 provides a short list of the wide-spread AD-like damage evoked by toxic AβO preparations. Even though structure-function details vary between laboratories, and some effects may have been found at pharmacological rather than pathogenic doses, the take-home lesson is that certain species of AβOs, found in vitro and in brain, are potent CNS neurotoxins. AβOs, which have been investigated in more than 3000 studies, are now considered the major toxic form of Aβ.

Table 2. Alzheimer’s-like neural damage instigated by AβOs. A comprehensive discussion of AβO-instigated neural damage can be found in recent reviews [22,40].

| Neuronal damage induced by AβOs | References |

| AD-type aberrant tau hyperphosphorylation | De Felice et al, 2008 [23]; Ma et al, 2009 [77]; Tomiyama et al, 2010 [8]; Zempel et al, 2010 [78] |

| Plasticity dysfunction (LTP/LTD) | Lambert et al, 1998 [1]; Walsh et al, 2002 [79]; Wang et al, 2002 [80]; Townsend et al, 2006 [81] |

| Memory failure | Selkoe, 2008 [82]; Shankar et al, 2008 [83]; Freir et al, 2011 [84]; Lesne et al, 2008 [85]; Poling et al, 2008 [86]; Xiao et al, 2013 [29] |

| Synapse loss | Zhao et al, 2006 [87]; Lacor et al, 2007 [55]; Shankar et al, 2007 [88]; Townsend et al, 2010 [89] |

| Disrupted Ca++ homeostasis | Demuro et al, 2005 [90]; De Felice et al, 2007 [49]; Alberdi et al, 2010 [91] |

| Oxidative, ER stress | Longo et al, 2000 [92]; Sponne et al, 2003 [93]; Tabner et al, 2005 [94]; De Felice et al, 2007 [49]; Resende et al, 2008 [95]; Nishitsuji et al, 2009 [96] |

| Synaptic receptor trafficking abnormalities | Snyder et al, 2005 [97]; Roselli et al, 2005 [98]; Lacor et al, 2007 [55]; Zhao et al, 2008 [52] |

| Inhibition of ChAT | Heinitz et al, 2006 [99]; Nunes-Tavares et al, 2012 [100] |

| Insulin resistance | Zhao et al, 2008 [52]; Zhao et al, 2009 [101]; Ma et al, 2009 [77]; De Felice et al, 2009 [102] |

| Inhibition of axonal transport | Pigino et al, 2009 [103]; Poon et al, 2011 [104]; Decker et al, 2010 [105] |

| Aberrant astrocytes, microglia | Hu et al 1998 [106]; Jimenez et al, 2008 [107]; Tomiyama et al, 2010 [8] |

| Cell cycle re-entry | Varvel et al, 2008 [108]; Bhaskar et al, 2009 [109] |

| Selective nerve cell death | Lambert et al, 1998 [1]; Kim et al, 2003 [54]; Ryan et al, 2009 [110] |

The stages in AD progression have been summarized by Jack and colleagues (Figure 2, right). Brain damage is now understood to begin decades before dementia, with Aβ pathology giving rise to tau pathology. In this context of disease progression, it is likely that brain damage begins with AβOs, which appear before plaques and comprise the major toxic forms of Aβ. Sometimes, as in the case of the Osaka mutation, AβOs appear even without plaques. Current finding are consistent with the hypothesis that AβOs provide a unifying mechanism for initiation of the neural damage underlying dementia. Evidence strongly points to the build-up of toxic AβOs as a seminal event in AD progression.

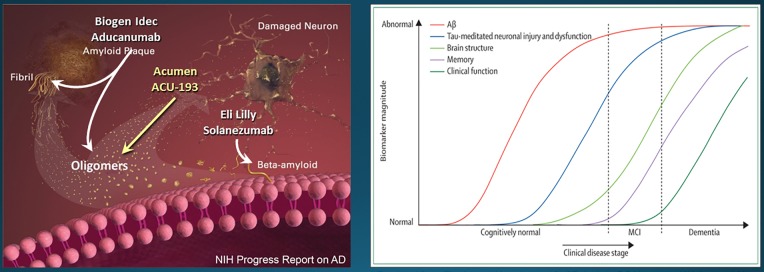

Figure 2.

Targeting AβOs for Alzheimer’s immunotherapy. Left: Potentially therapeutic antibodies from Biogen Idec, Acumen, and Lilly show specificity for different forms of Aβ and Aβ assemblies. The major pathogenic form of Aβ is thought to be oligomeric (Reprinted with Jannis Productions permissions from the “Progress Report on Alzheimer’s Disease 2004-2005” (ed. AB Rodgers), NIH Publication Number: 05-5724. Digital images produced by Stacy Jannis and Rebekah Fredenburg of Jannis Productions.) [73]. Right: Neural damage begins decades before the onset of clinical dementia. Pathology in Aβ and tau are regarded as instigating the neural damage. The timing and inter-relationship of the two pathologies remains under investigation (Reprinted from The Lancet Neurology, v. 9. CR Jack Jr, DS Knopman, WJ Jagust, LM Shaw, PS Aisen, MW Weiner, RC Petersen, and JQ Trojanowski. Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade, pp 119-128, (2010), with permission from Elsevier.) [74].

Testing the AβO Hypothesis with Clinical Trials

Continued interest in the AβO hypothesis will require successful clinical trials based on preventing AβOs from instigating neural damage. The most advanced approach is immunotherapy. AβO-specific antibodies, developed to verify the presence of toxic AβOs in AD pathology, can prevent pathology and memory loss in transgenic AD animals. An early success used the pan-oligomer specific A11 polyclonal to lower tau pathology in the 3xTg-AD mouse model [7]. Other AβO-targeting antibodies have rescued behavior as well as neural health in Tg AD models [29-32]. The critical question is whether these successes can be translated to humans. There have been multiple clinical trial failures of immunotherapy related to Aβ going back to 2000. The latest disappointment occurred with Lilly’s Solanezumab, which targets monomeric Aβ (Figure 2). These failures, along with unsuccessful trials using small molecule treatments designed to prevent Aβ pathogenesis, have cost an estimated $18 billion. The extreme cost of past failures has virtually poisoned the well for new therapeutic strategies targeting Aβ.

However, after 15 years of failures, a new trial has provided positive results, and these are in harmony with predictions of the AβO hypothesis. Aducanumab, a therapeutic monoclonal from Biogen Idec was found to slow cognitive deterioration in early stage clinical trials [33]. Aducanumab binds AβOs and fibrillar Aβ but not monomeric Aβ, although there appears to be a problem with dosage. The need for high levels can be explained by nonproductive association of Aducanumab with senile plaques. More specific antibodies could prove beneficial. ACU193, a humanized antibody developed by Acumen, engages AβOs without binding monomers or the fibrillar Aβ of amyloid plaques (Figure 2) [34,35]. If successful in clinical trials, ACU193 would provide definitive substantiation of the AβO hypothesis.

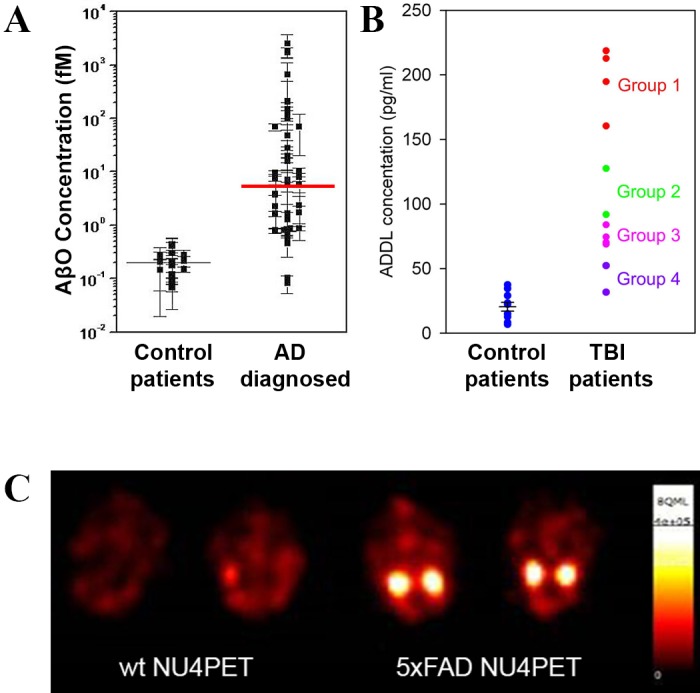

AβO antibodies also may provide companion diagnostics useful for tracking AβOs as biomarkers for efficacy of investigational new drugs (INDs). Measurements of AβOs in CSF showed strong AD-dependence, with greater accuracy than other CSF biomarkers in resolving AD from non-AD samples (Figure 3a). AβOs may be important, too, for certain types of neural damage in younger individuals, not due to AD. It has been found, e.g., that CSF AβOs are associated with acute traumatic brain injury [36], and a poor prognosis appears linked to elevated AβO levels (Figure 3b). CSF AβO levels, however, are extremely low and very difficult to assay [37]. Neuroimaging is emerging as a promising alternative. Molecular MRI detection of AβOs, e.g., can differentiate AD from control mice [38]. The MRI probe in this study was provided by AβO-specific antibodies covalently linked to magnetic nanostructures, which provide a strong contrast agent. New evidence suggest that AβO antibodies also can be modified to provide ultrasensitive PET probes useful for early AD diagnostics (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

AβOs in CSF of AD and TBI patients detected by Biobarcode and in AD mouse brain by PET imaging. A: An ultrasensitive nanotechnology-based immunoassay (Biobarcode) was used to determine cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) AβO levels in AD patients compared to controls (adapted and reprinted with permission from “Nanoparticle-based detection in cerebral spinal fluid of a soluble pathogenic biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease” by Georganopoulou DG, Chang L, Nam JM, Thaxton CS, Mufson EJ, Klein WL, and Mirkin CA. This was published in Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Feb 15;102(7):2273-6. Epub 2005 Feb 4. Copyright (2005) National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A.) [75]. Error bars are for individual samples, which required replicate assays for accuracy because of the low AβO levels. There is minimal overlap between AD and control patients, and the median difference is 30-fold. B: CSF from emergency room patients were assayed for relative AβO levels using the Biobarcode immunoassay. Higher AβO levels were associated with worsening prognosis. C: NU4 was covalently modified with the cation chelator DOTA and labeled with Cu64. Two 5XFAD mice and two wildtype littermates (age 8 to 9 months) received probe (NU4PET) through tail-vein injection. After 30 hours of periodic whole animal scans, animals were sacrificed and the brains removed for final imaging. Final scans show robust PET signal is still present in AD but not wildtype samples.

An Alternative to Therapeutic Antibodies: Searching for Small Molecules that Block AβOs from Instigating Neural Damage

Although an important goal, the discovery of therapeutic small organic molecules (SOMs) that block the impact of AβOs is limited by the gaps in our understanding of the AβO mechanism. The better understood steps occur downstream in the toxic pathway. These intracellular abnormalities include excessive Ca++ mobilization by hyperactive mGluR5 receptors; stimulation of Fyn protein tyrosine kinase; hyper-activation of NMDA-Rs, which exacerbates Ca++ build-up and causes ROS accumulation; pathological phosphorylation of tau; and, ultimately, bifurcating pathways leading to multiple pathological outcomes (for reviews, see [22,39-41]).

As mentioned, pathogenic tau species are induced by AβOs, and extensive efforts are underway to find treatments that protect against tau-induced neural damage. This downstream target is appealing given discoveries that tau mediates aspects of damage instigated by AβOs [24]. In essence, AβOs act as the match, and tau is a fuse they light. It is likely that other fuses exist, including the AβO-induced build-up of excessive Ca++ levels. Anti-tau strategies include development of antibodies against pathological tau as well as SOMs designed to prevent pathological tau build-up [42,43].

AβO-activation of the protein tyrosine kinase Fyn also is being targeted for therapeutics. As the case for AD-type tau phosphorylation [44], initial discoveries that Fyn is germane to the impact of toxic Aβ were made using mixed Aβ preps containing abundant fibrils [45]. Subsequent knockout data showed Fyn has a central role in the mechanism of AβO toxicity, with Fyn implicated in deteriorating synapse plasticity as well as neuron death [1]. Most recently, the role of Fyn has been substantiated by experiments showing Fyn is an effector of the binding of toxic AβO species to the cellular prion protein [46]. The mGluR5 receptor appears to act between AβO-affected prion protein and Fyn [47]. A re-targeted Fyn inhibitor developed for cancer is now under investigation in an Alzheimer’s clinical trial [48].

Targeting the Earliest Steps in the Toxic Pathway--Not Enough is Known

Although a great deal is known about the cellular consequences of AβO exposure, ideally, a therapeutic inhibitor would act before AβOs induce intracellular pathology. The current AD drug Namenda is an open channel inhibitor of NMDA-Rs, and it reduces the ability of AβOs to upregulate Ca++ and ROS levels [49], but its efficacy in patients diminishes with time. The mechanism for NMDA-R hyperactivity likely involves Fyn, and Fyn appears stimulated by Ca++, which is elevated by mGluR5 hyperactivity [46,47,50]. Ca++ appears to be central to the mechanism [51,52]. While Ca++ is elevated by AβO-induced hyperactivity of NMDA-R and mGluR5 receptors, there also is evidence suggesting elevation is due to a pore-like action of AβOs, inserted directly into lipid bilayers [53]. Action as a pore may be the mechanism for certain structural forms of AβOs. However, a non-selective action as Ca++ pores is difficult to reconcile with AβO species that show cell-specific responses. An example considered above was the dependence of AD-type tau phosphorylation on cell surface AβO clusters of synthetic or brain-derived AβOs [23]. In cell and brain slice cultures, moreover, many neurons are resistant to AβO-toxicity [1,54].

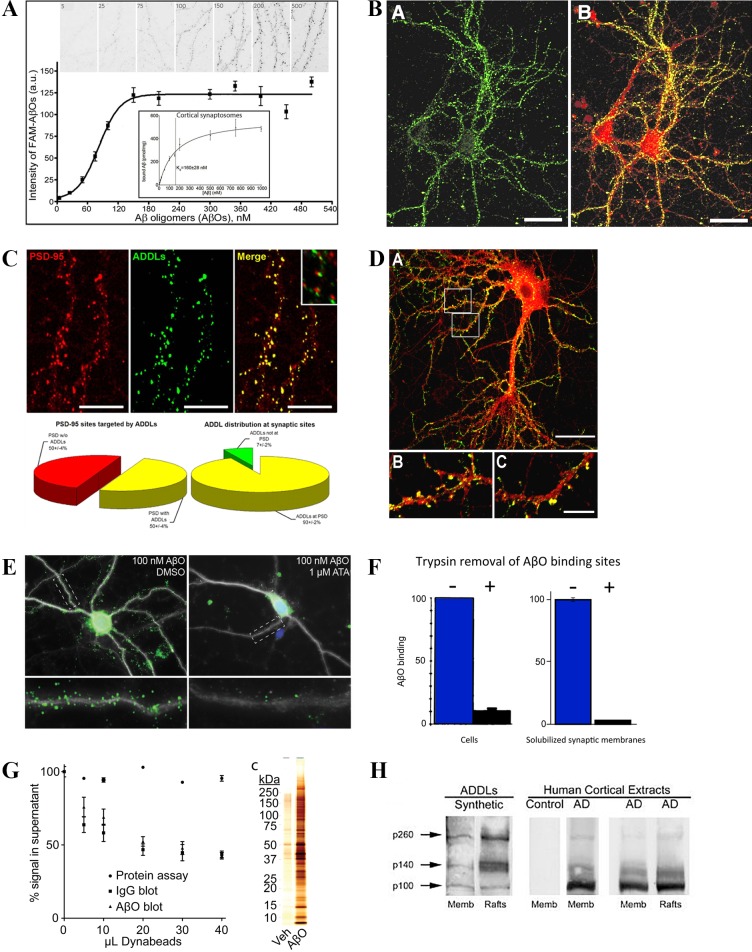

A mechanism that fits well for the cell-based evidence obtained with most AβO preparations is the receptor hypothesis. The idea that AβOs act by binding to specific proteins that act as toxin receptors was introduced to explain the sensitivity of AβO binding and toxicity to low amounts of trypsin [1]. Figure 4 illustrates aspects of the evidence supporting the toxin receptor hypothesis. Experiments investigating AβO binding have established (A) saturation and high-affinity binding to cultured neurons and synaptosome preparations; (B) specificity for particular neurons and particular brain regions; (C) targeting of synapses; (D) accumulation at dendritic spines; (E) sensitivity to low doses of antagonist; (F) binding to trypsin-sensitive proteins; (G) association with small patches of isolatable membranes; (H) specificity in Far Western blots for a small number of proteins [4,16,38,55,56]. These findings generally apply to brain-derived as well as synthetic AβOs. The conclusion from these studies is that binding of AβOs is ligand-like and mediated adventitiously by proteins acting as toxin receptors. Such specific binding offers strategic routes to drug discovery, as most common drugs interact with cell surfaces. It would be ideal if analogous targets could be found for AD therapeutics.

Figure 4.

Evidence in harmony with the AβO toxin receptor hypothesis. Panels A-D: Mature hippocampal neuron cultures (21 to 24 days in vitro) were incubated with AβOs and imaged for distribution using AβO specific immunofluorescence and relevant markers. The first four panels illustrate, respectively - A: saturable, high-affinity binding (Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature Nanotechnology. Viola KL, Sbarboro J, Sureka R, De M, Bicca MA, Wang J, Vasavada S, Satpathy S, Wu S, Joshi H, Velasco PT, MacRenaris K, Waters EA, Lu C, Phan J, Lacor P, Prasad P, Dravid VP, Klein WL. Towards non-invasive diagnostic imaging of early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Nanotechnol. 10(1):91-8., 2015.) [38]; B: specificity for particular neurons (double-labeled for CaM kinase II in red and AβOs in green) (B-D Reprinted with permission from “Synaptic Targeting by Alzheimer’s Related Amyloid β Oligomers” by Pascale N. Lacor, Maria C. Buniel, Lei Chang, Sara J. Fernandez, Yuesong Gong, Kirsten L. Viola, Mary P. Lambert, Pauline T. Velasco, Eileen H. Bigio, Caleb E. Finch, Grant A. Krafft and William L. Klein, published in J Neurosci 2004 24(45):10191-200.) [4]; C: specificity for synapses (double-labeled for PSD95 in red and AβOs in green) [4]; and D: accumulation at dendritic spines (double-labeled for CaM kinase II in red and AβOs in green) [4]. Panels E-H: The second 4 panels illustrate, respectively - E: binding of AβOs to spines of hippocampal neuron cultures is blocked by low doses of aurintricarboxylic acid (ATA) (Reprinted with permission under the Creative Commons Attribution License from Wilcox KC, Marunde MR, Das A, Velasco PT, Kuhns BD, Marty MT, et al. (2015) Nanoscale Synaptic Membrane Mimetic Allows Unbiased High Throughput Screen That Targets Binding Sites for Alzheimer’s-Associated Aβ Oligomers. PLoS ONE 10 (4): e0125263.) [76]; F: binding to cells or membrane fractions is to trypsin-sensitive proteins (Reprinted with permission from “Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ1–42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins” by M. P. Lambert, A. K. Barlow, B. A. Chromy, C. Edwards, R. Freed, M. Liosatos, T. E. Morgan, I. Rozovsky, B. Trommer, K. L. Viola, P. Wals, C. Zhang, C. E. Finch, G. A. Krafft, and W. L. Klein. This was published in Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 May 26;95(11):6448-53. Copyright (1998) National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A.) [1]; G: AβO-dependent immune-pulldown of partially solubilized synaptosomes yields a highly selective protein complex (Reprinted with permission under the Creative Commons Attribution License from Wilcox KC, Marunde MR, Das A, Velasco PT, Kuhns BD, Marty MT, et al. (2015) Nanoscale Synaptic Membrane Mimetic Allows Unbiased High Throughput Screen That Targets Binding Sites for Alzheimer’s-Associated Aβ Oligomers. PLoS ONE 10 (4): e0125263.) [76]; and H: Far Western blots using synthetic AβOs and human AD brain extracts show selective, ligand-like binding (Reprinted with permission from “Alzheimer’s disease-affected brain: presence of oligomeric A beta ligands (ADDLs) suggests a molecular basis for reversible memory loss” by Gong Y, Chang L, Viola KL, Lacor PN, Lambert MP, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL. This was published in Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Sep 2;100(18):10417-22. Epub 2003 Aug 18. Copyright (2003) National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A.) [16].

Interaction between AβOs and NaK ATPase α3 (NKAα3) may be the First Cell Surface Step with Pathogenic Consequences

A number of AβO binding proteins have been identified, and many have properties that make them promising candidates as toxin receptors (reviewed in [22,40]). An intriguing new candidate recently was described in a comprehensive study by Ohnishi et al. [57]. They reported that the α3 subunit of the NaK ATPase is a toxin receptor for synthetic and AD brain-derived AβOs. In their study they speculated that the p100 band our laboratory observed in Far Western blots (Figure 4H) was likely NKAα3; this is consistent with results presented later. Ohnishi et al identify the NKAα3 as a “death target” for AβOs, which inhibit sodium pump activity. As we describe below, AβOs have a second impact that could be central to their pathogenic mechanism.

In the Ohnishi study, NKAα3 was shown to have high affinity for AβOs derived from AD brain tissue as well as for what appears to be a widely used synthetic AβO preparation. The authors reported their synthetic AβOs show close homology with brain-derived AβOs they refer to as amylospheroids. They found NKAα3 showed little interaction with various synthetic preparations but bound tightly to AβOs made in F12 medium using 50 µM Aβ. What adds interest to the ATPase discovery is that their method for preparing synthetic ligand is virtually the same as used by our lab and many others [58]. These preparations have been shown to instigate AD-like in a large number of cell and animal experiments. Findings from Ohnishi and colleagues thus open the door to connecting NKAα3 to the mechanism underlying a spectrum of AβO-induced neural damage.

NKAα3 acts, in the authors’ terms, as a death protein for AβOs. They found that binding leads to a slow, time-dependent inhibition of ATPase activity, Ca++ build-up via N-VSCC and mitochondrial channels, and apoptosis. Various glutamate receptor antagonists were not neuroprotective. AβO binding and toxicity were found to be linked to the abundance of NKAα3, both regionally and developmentally. The EC50 for ATPase inhibition and neurodegeneration correlated with the high affinity of AβO binding in vitro. The EC50 for binding was ~ 5nM based on a MW of 118 kDa. This EC50 is equal to 1.4 µM based on the commonly used monomer equivalents, used because of the difficulty in determining precise AβO structure. For toxicity experiments, the authors used 100 to 140 nM doses of the amylospheroids; these doses are 3 to 4 µM in total Aβ equivalents. The distribution of the NKAα3 toxin receptor was inferred to be presynaptic, and they cited their prior work as supporting this inference [59].

Our new findings strongly support involvement of NKAα3 in AβO toxicity, but with several differences in detail from the Ohnishi study, and they provide new insight into the molecular mechanism. As presented below, our data demonstrate that NKAα3 has high affinity for synthetic preparations of AβOs used by our group and others. Moreover, content-rich cell biology experiments provide support for our previous hypothesis that the toxicity of AβOs derives at least in part from a pathological redistribution of membrane proteins [50]. This hypothesis is in harmony with an intriguing “docking” function of NKAα3, discussed below.

To obtain AβO binding proteins in an unbiased way using classic affinity isolation, we used nanoscale artificial membranes to reconstitute the solubilized synaptic membrane proteome. The nanoscale membranes are referred to as Nanodiscs [60,61]. Nanodiscs are self-assembling discoid monolayers that have diameters of approximately 15 nm, and each nanoscale membrane disc is expected to have one or zero incorporated proteins. In other words, they are virtually soluble membranes. We recently described use of Nanodiscs with the reconstituted synaptic membrane proteome for investigating AβO binding [56]. In this preparation, AβOs bind saturably to trypsin-sensitive proteins, and, assuming the ligands we prepare are 24mers (Figure 2, above), the EC50 for binding is ~ 4 nM. This is similar to that observed for amylospheroid binding to NKAα3. Our ligand also binds with approximately the same EC50 to synaptosomes, and the Bmax for synaptosomes is 24 pmols/mg protein, roughly equivalent to the numbers obtain by Ohnishi and colleagues.

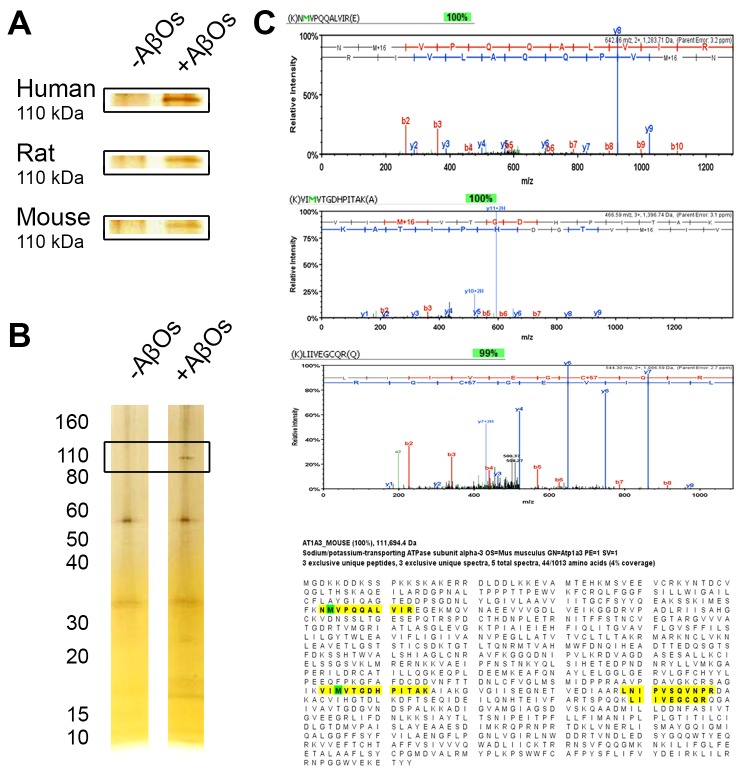

In a new set of experiments, crude synaptosomes from human, rat, and mouse brains were solubilized in a nonionic detergent and the solubilized proteins reconstituted in Nanodiscs as described [56]. Reconstituted synaptosome proteomes were incubated with AβOs, washed to remove unbound AβOs, and incubated with the AβO-specific monoclonal antibody (NU2). Washes were done to remove unbound antibody and the NU2-positive Nanodiscs were collected according to our published protocol [56]. Silver stain of the AβO-dependent proteins in the isolated Nanodiscs showed a band at ~110 kDa, essentially the size of the NKAα3 subunit (Figure 5A). Another mouse brain preparation showed this prominent 110 kDa species and some faint bands where AβO trimers to pentamers would be present in SDS gels (Figure 5B). Peptide spectra from LC-MS/MS analysis confirmed that the isolated 110 kDa AβO binding protein was NKAα3 (Figure 5C). MS analysis of the human AβO binding protein was not done, but two separate analyses of mouse isolates and one of a rat isolate confirmed the presence of NKAα3. A 260 kDa band (not shown) was identified as an intracellular protein which will be considered in another publication. The p100 band observed in Far Western blots (Figure 4H) also was found to be NKAα3, as surmised by Ohnishi et al.

Figure 5.

110 kDa AβO binding protein from Nanodisc-solubilized synaptosomes is NaK ATPase α3. A. Crude synaptosomes prepared from human, rat, and mouse brain were solubilized and membrane proteins reconstituted in soluble Nanodiscs as described for rat [56]. Nanodiscs were incubated +/- 500 nM AβOs, washed, incubated with the NU2 AβO-specific antibody, washed, and antibody positive Nanodiscs isolated using magnetic beads as described [85]. Comparison of isolates analyzed by SDS PAGE and silver stain showed an AβO-dependent band at ~110 kDa for all species. B. Crude synaptosomes from adult wildtype mice were solubilized, membrane proteins reconstituted in soluble Nanodiscs, and treated as in (A) to identify AβO-dependent binding proteins. Silver stained SDS gels, in addition to the prominent 110 kDa band, show faint bands where SDS-sensitive AβO peptides are expected. C. LC-MS/MS spectra of three peptides of solubilized AβO-dependent isolates from mouse synaptosomes show identity with sequences unique to NKAα3. A fourth peptide (not shown) showed 90 percent identity. These amino acid sequences distribute across the coding region (bottom panel, yellow highlight) and provide a 100 percent confidence level that the isolated AβO binding protein is NKAα3. In three separate preparations, this level of confidence was observed twice for mouse and once for rat.

We previously found it also was possible to pull down AβOs associated with partially solubilized synaptic membranes (Figure 4G). Although the isolates contained an immeasurably small fraction of the starting material, they nonetheless contained a large array of associated proteins, as seen in the figure, including a prominent band at ~110 kDa. Detergent extraction using conditions that maintain AβO binding thus also maintain lateral interactions between membrane proteins. LC-MS/MS analysis of the isolates included NKAα3 as one of 43 proteins identified with 100 percent confidence. The extent to which the isolated membrane fragments contained what has been referred to as an NKAα3 docking station [62] is unknown.

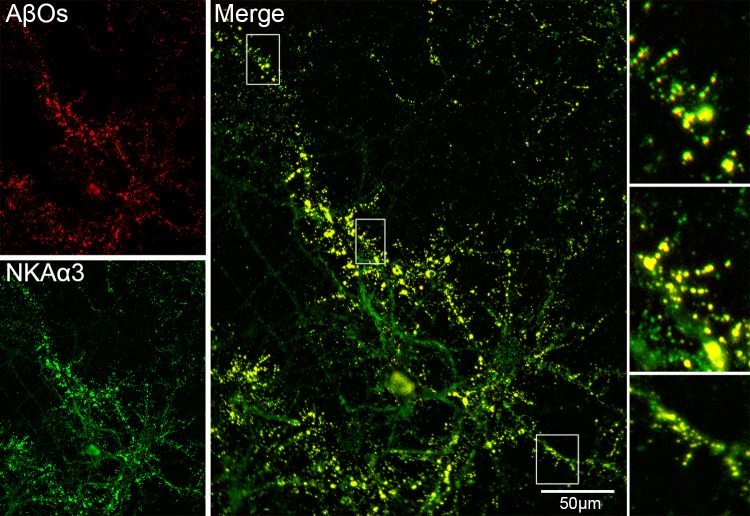

Cell biology experiments with hippocampal neurons showed AβOs co-distribute with NKAα3 (Figure 6). Mature hippocampal neuron cultures incubated with AβOs were fixed and double-labeled with the NU4 AβO-specific antibody and with an NKAα3 specific antibody. These data are consistent with the hypothetical role of NKAα3 as a toxin receptor for AβOs. High magnification shows that co-localization is evident in dendritic spines, consistent with previous experiments concerning AβO distribution (Figure 4c,d) [4].

Figure 6.

AβO binding sites co-localize with NKAα3 in hippocampal neuron cultures. Primary rat hippocampal neurons were obtained from E18 embryos and cultured for 18 days before use in immunofluorescence studies. Mature cultures were incubated with 200 nM AβOs (in total Aβ monomer equivalents, which equals 8 nM of 24mers). Neurons were fixed and double-labeled for AβOs (red) and NKAα3 (green). Overlays show prominent co-localization (gold), consistent with NKAα3 being a major AβO binding protein. Controls with labeled f-actin established that superposition of signals is not caused by bleed-through (not shown). Inset shows co-localization at dendritic spines.

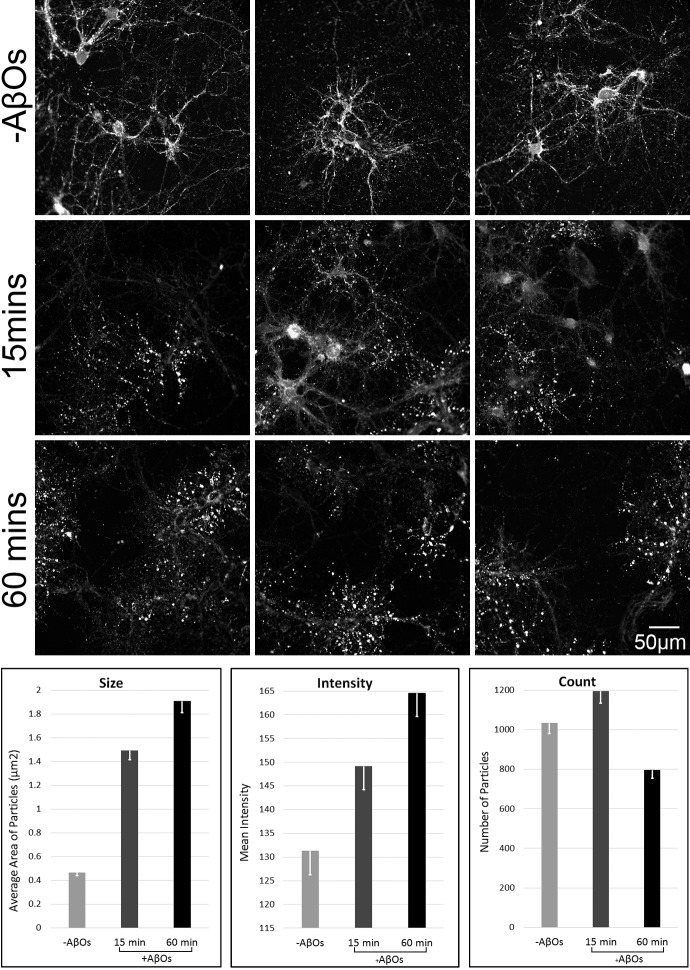

Significantly, exposure of neurons to AβOs results in a profound alteration in NKAα3 distribution (Figure 7). This is a time-dependent phenomenon. As seen in the panels of Figure 7, the size of ATPase puncta, which co-distribute with surface bound AβOs, increases markedly by 15 to 60 minutes. Quantitation shows a 4-fold increase by 60 minutes. The intensity of the punctate signal, which reflects abundance of NKAα3, also increased with time, indicating the NKAα3 molecules did not just spread out but in fact were still present in high density. Total puncta number was unchanged at 15 minutes, but showed a possible decrease by 60 minutes. The puncta are most likely at dendritic spines, which have previously been shown to show time-dependent changes in morphology and abundance due to AβO exposure. The data support the conclusion that normal NKAα3 membrane organization is greatly disrupted by AβOs.

Figure 7.

AβO-induced disruption of NKAα3 topology. Mature hippocampal neuron cultures were incubated +/- 200 nM AβOs (8 nM of 24mer) for 15 or 60 minutes. Cells were fixed and labeled for NKAα3. Results show that by 15 minutes, AβOs had caused a redistribution of NKAα3 into enlarged clusters along dendrites. These clusters co-localize with AβOs (Figure 6), which accumulate at dendritic spines (Figures 4 and 6). For quantitation, raw images were normalized to an 8-bit range and inverted before thresholding with the Intermodes method in Image J. The Analyze Particles function was used to calculate the total number of particles within a 786x888 pixel region of interest (ROI). Size, mean intensity, and total count of particles within ROIs from each image were averaged for Vehicle control (-AβO), 15 min AβO, and 60 minute AβO exposures (n=3 for each condition). Induction of enlarged clusters of NKAα3 resembles the AβO-induced clustering of mGluR5 [50].

This phenomenon of co-clustering and recruitment into expanding clusters was found previously in our studies of AβOs and mGluR5, a Ca++ mobilizing receptor whose activity is required for AβO toxicity. Based on this prior work, the co-clusters of AβOs and ATPase seen here can be inferred to also include mGluR5. This redistribution of NKAα3 and, putatively, of its docking station proteins is an important new facet of the mechanism of AβO toxicity.

An Integrated Mechanism for AβO Toxicity with Dual Paths to Pathogenicity

Our new results substantiate and extend the discovery of Ohnishi and colleagues that NKAα3 is a binding protein for AβOs [57]. We have confirmed that AβOs bind to NKAα3 in vitro and co-localize with NKAα3 in mature hippocampal cultures. In a finding we consider mechanistically significant, our data show striking changes induced in the topology of the NKAα3 docking station. Within minutes of exposure to AβOs, NKAα3 became accumulated in dense clusters along dendrites, a pathological redistribution of NKAα3 molecules in the membranes of vulnerable hippocampal neurons. This is a newly found impact of AβOs that extend findings regarding inhibition of sodium transport function. Besides cation transport, NKAα3 plays a role as a docking station for multiple membrane proteins [62], including neurotransmitter receptors linked to AβO-induced neuronal damage [63]. The function of ATPase docking stations normally is in signaling [64,65], somewhat analogous to the protein-organizing role of focal adhesions in integrin signaling. Altered topology of these signaling clusters would be expected to contribute to neuronal dysfunction and damage. In addition, these images implicate ATPase docking stations in the mechanism by which AβOs become clustered at cell surfaces. As we previously showed, this clustering is particularly prominent at dendritic spines ([4]; Figure 4). The pathological significance of AβO clusters is indicated by experiments in which tau pathology induced by AβOs is restricted to neurons that manifest these clusters [23].

The clustering of NKAα3 is in harmony with our earlier observation that AβOs induce the clustering of mGluR5 [50]. mGluR5 is a Ca++ mobilizing receptor, and it is regarded as a key mediator of AβO-elevated Ca++ build-up and the damage that ensues [47]. Importantly, clustering of mGluR5 molecules can also be induced by receptor antibodies [50]. This antibody-mediated mGluR5 clustering mimics the toxic impact of AβOs. Clustering itself thus appears to be a seminal step for the mechanism.

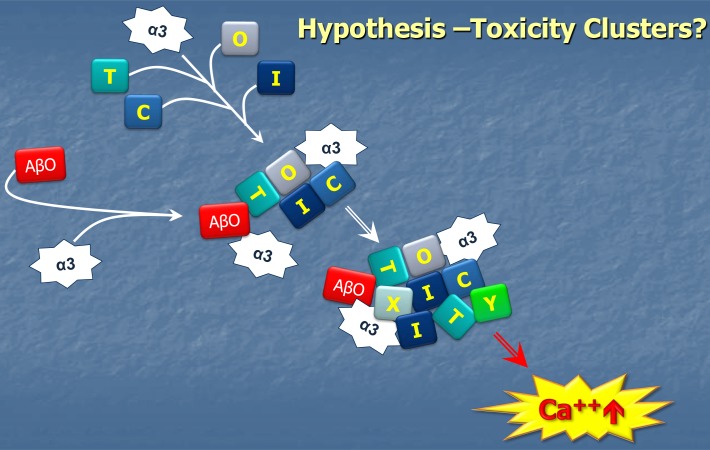

The current data are consistent with a central role for NKAα3 in the ectopic clustering associated with the mechanism of AβO toxicity. Because mGluR5 and NKAα3 each co-localize with cell-surface bound AβOs, we infer they are part of the same ectopic clusters. With respect to generation of these clusters, the role of the NKAα3 docking station relative to roles played by mGluR5, or other membrane domain-organizing proteins such as PrP [66], is not yet clear. Hypothetically, it would seem, however, that the direct binding of AβOs to NKAα3 and its impact on the topology of the NKAα3 docking station would cause major disruption in the distribution of many other membrane proteins, with one important consequence being build-up of Ca++ to pathogenic levels (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Hypothetical pathology of the NKAα3 docking station as an early event in AβO-induced neuronal damage. AβOs are hypothesized to act as neurotoxins when they attach to neuron surfaces because they cause restructuring of NKAα3 docking stations, with pathogenic clustering of various membrane proteins such as mGluR5 contributing to toxic Ca++ build-up. As described by Ohnishi et al (2015) [57], the impact of AβOs also includes inhibition of NKAα3 transport function.

The need for a docking station in the mechanism of AβO toxicity, whether provided as hypothesized in Figure 8 by NKAα3 or some other protein, was first evident in single particle tracking experiments. These experiments followed diffusion of individual AβOs and mGluR5 molecules on the surfaces of live neurons using quantum dots [50]. Both AβOs and mGluR5 at first diffuse like untethered membrane proteins. Within minutes of adding AβOs to the cells, however, both the AβOs and mGluR5 became immobilized, frequently at synapses. This immobilization is consistent with confocal imaging showing AβO clusters at dendritic spines in fixed cells. Recently, single particle tracking experiments have shown that NKAα3 becomes immobilized during exposure of hippocampal neurons to toxic assemblies of synuclein [67]. Results suggest a possible central role for ATPase as an immobilizing docking station for toxic oligomers found in multiple proteinopathies. It may be that AβOs can be brought to docking stations by different protein shuttles, and that at docking stations, there may be a need for co-receptors to mediate docking, or for additional scaffolding proteins to stabilize the pathogenic docking station itself. For AβOs, the immobilized state appears to act as a seed to which certain proteins are rerouted, where they form expanding clusters containing AβOs, mGluR5 receptors, NKAα3, and in all likelihood, numerous other membrane proteins.

Results obtained with the AβO ligands prepared for the current study show both differences and similarities with respect to the findings of Ohnishi and colleagues. First of all, the co-localization of our AβOs and NKAα3 is clearly evident at dendritic spines (Figure 6). This distribution is consistent with dendritic spine localization of NKAα3 reported in experiments with super-resolution fluorescence microscopy [68,69]. Ohnishi and colleagues, however, in their study reported that binding of AβOs to NKAα3 occurred at presynaptic terminals. Another difference concerns the sensitivity of AβO toxicity to glutamate receptor antagonists. Our AβO preparations elicit an array of AD-like pathology, and these responses are significantly lowered or fully blocked by antagonists of NMDA and mGluR5 receptors [49,50]. Most AD-like pathology is evident in cultures containing almost exclusively neurons, but cell death is minimal; neuron death likely requires the presence of factors released by glia [70]. We speculate that the impact of AβOs on NKAα3 may render them more vulnerable to inflammatory cytokines. Ohnishi and colleagues found their AβOs evoked cell death, and this was resistant to glutamatergic antagonists. Although this might be attributable to unique structural features of their preparations, this seems unlikely, as their size and shape in AFM, aspects of their immunoreactivity, and the MW obtained by biochemical assays are very much like those of the AβOs used in the current study. This is consistent with the fact that the synthetic amylospheroids are prepared in much the same manner as our preparations, using 50 µM Aβ monomer in F12 solutions. A possible salient difference in experimental conditions may be in concentrations of AβOs used. The concentrations employed for amylospheroid experiments are at least 10 times greater than in our experiments.

Overall, the current data are consistent with the hypothesis that AβO attachment to cell surfaces is transduced into a neurotoxic phenomenon by an altered membrane protein topography seeded by AβO binding to NKAα3. The seminal interactions between AβOs and NKAα3 molecules at the cell surface may prove to be suitable targets for new drug discovery strategies. Detailed structural analysis of the binding site by Ohnishi and colleagues has yielded neuroprotective peptides based on the amino acid sequence of an external loop of the NKAα3 [57]. This antagonist, which binds to the AβO ligand, is now being exploited for rational drug design. A successful result would provide, in essence, a small molecule equivalent of a therapeutic antibody. In another approach, proof of concept has been obtained that small molecules can bind to the toxin receptor at the cell surface and prevent AβO binding (Figure 4e). Attachment of AβOs to NKAα3 is amenable to high throughput screening for antagonists using Nanodiscs [56]. Results from a preliminary screen showed that AβO binding to spines can be blocked by low doses of a small organic molecule, albeit one with promiscuous binding precluding its use for therapeutics. Nonetheless, McGeer and colleagues have shown that behavior in a transgenic AD model could be safely rescued using this same compound [71]. Future investigations of the docking station hypothesis are expected to open the door to therapeutics targeting the first step of a complex pathway that leads to neural damage and dementia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an anonymous donation and NIH grants to WLK and a MIRA grant from NIH (GM118145) to SGS. Proteomics services were performed by the Northwestern Proteomics Core Facility, generously supported by NCI CCSG P30 CA060553 awarded to the Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center and the National Resource for Translational and Developmental Proteomics supported by P41 GM108569.

Glossary

- AβOs

Amyloid beta oligomers

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- CNS

central nervous system

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- INDs

investigational new drugs

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- mGluR5

metabotropic glutamate receptor 5

- MW

molecular weight

- NMDA-R

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor

- NaKAα3

Sodium potassium ATPase alpha3

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Tg

transgenic

- SOM

small organic molecule

Author Contributions

Thomas DiChiara, – designed, executed, and analyzed experiments & data; Nadia DiNunno – designed, executed, and analyzed experiments & data; Jeffrey Clark – designed, executed, and analyzed experiments & data; Riana Lo Bu – designed, executed, and analyzed experiments & data; Erika N. Cline – designed, executed, and analyzed experiments & data; Madeline G. Rollins – designed, executed, and analyzed experiments and data; Yuesong Gong – designed, executed, and analyzed experiments & data; David L. Brody – provided key materials and expertise for experimental design & analysis; Stephen G. Sligar - provided key materials and expertise for experimental design & analysis; Pauline T. Velasco – designed, executed, and analyzed experiments & data; Kirsten L. Viola – designed, executed, and analyzed experiments & data; William L. Klein – wrote manuscript, supervised and assisted with the design, execution, and analysis of experiments & data.

References

- Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA. et al. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Abeta1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(11):6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frackowiak J, Zoltowska A, Wisniewski HM. Non-fibrillar beta-amyloid protein is associated with smooth muscle cells of vessel walls in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1994;53(6):637–645. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199411000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda T, Pasinetti GM, Osterburg HH. et al. Purification and characterization of brain clusterin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;204(3):1131–1136. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Chang L. et al. Synaptic targeting by Alzheimer's-related amyloid beta oligomers. v. 2004;24(45):10191–10200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3432-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi RH, Almeida CG, Kearney PF. et al. Oligomerization of Alzheimer's beta-amyloid within processes and synapses of cultured neurons and brain. J Neurosci. 2004;24(14):3592–3599. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5167-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucke L, Masliah E, Yu GQ. et al. v. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20(11):4050–4058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04050.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, Caccamo A, Tran L. et al. Temporal profile of amyloid-beta (Abeta) oligomerization in an in vivo model of Alzheimer disease. A link between Abeta and tau pathology. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(3):1599–1604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomiyama T, Matsuyama S, Iso H. et al. A mouse model of amyloid beta oligomers: their contribution to synaptic alteration, abnormal tau phosphorylation, glial activation, and neuronal loss in vivo. J Neurosci. 2010;30(14):4845–4856. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5825-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti MT, Bruno MA, Ducatenzeiler A. et al. Intracellular Abeta-oligomers and early inflammation in a model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(7):1329–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price KA, Varghese M, Sowa A. et al. Altered synaptic structure in the hippocampus in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease with soluble amyloid-beta oligomers and no plaque pathology. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:41. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MP, Velasco PT, Chang L. et al. Monoclonal antibodies that target pathological assemblies of Abeta. J Neurochem. 2007;100(1):23–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomiyama T, Nagata T, Shimada H. et al. A new amyloid beta variant favoring oligomerization in Alzheimer's-type dementia. Ann Neurol. 2008;63(3):377–387. doi: 10.1002/ana.21321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosensweig C, Ono K, Murakami K. et al. Preparation of stable amyloid beta-protein oligomers of defined assembly order. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;849:23–31. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-551-0_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco PT, Heffern MC, Sebollela A. et al. Synapse-binding subpopulations of Abeta oligomers sensitive to peptide assembly blockers and scFv antibodies. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2012;3(11):972–981. doi: 10.1021/cn300122k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutaud O, Montine TJ, Chang L. et al. PGH2-derived levuglandin adducts increase the neurotoxicity of amyloid beta1-42. J Neurochem. 2006;96(4):917–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Chang L, Viola KL. et al. Alzheimer's disease-affected brain: presence of oligomeric A beta ligands (ADDLs) suggests a molecular basis for reversible memory loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(18):10417–10422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834302100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesne S, Koh MT, Kotilinek L. et al. A specific amyloid-beta protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440(7082):352–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S, Garzon DJ, Marchese M. et al. Decreased brain-derived neurotrophic factor depends on amyloid aggregation state in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2009;29(29):9321–9329. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4736-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, Cheung TT, Cai XD. et al. An increased percentage of long amyloid beta protein secreted by familial amyloid beta protein precursor (beta APP717) mutants. Science. 1994;264(5163):1336–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.8191290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Reed MN, Kotilinek LA. et al. Quaternary Structure Defines a Large Class of Amyloid-beta Oligomers Neutralized by Sequestration. Cell Rep. 2015;11(11):1760–1771. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn AP, Wong BX, Johanssen T. et al. Amyloid-beta Peptide Abeta3pE-42 Induces Lipid Peroxidation, Membrane Permeabilization, and Calcium Influx in Neurons. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(12):6134–6145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.655183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viola KL, Klein WL. Amyloid beta oligomers in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis, treatment, and diagnosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129(12):183–206. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1386-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Felice FG, Wu D, Lambert MP. et al. Alzheimer's disease-type neuronal tau hyperphosphorylation induced by A beta oligomers. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29(9):1334–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zempel H, Luedtke J, Kumar Y. et al. Amyloid-beta oligomers induce synaptic damage via Tau-dependent microtubule severing by TTLL6 and spastin. Embo J. 2013;32(22):2920–2937. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR Jr., Barrio JR, Kepe V. Cerebral amyloid PET imaging in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(5):643–657. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1185-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pooler AM, Polydoro M, Maury EA. et al. Amyloid accelerates tau propagation and toxicity in a model of early Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2015;3:14. doi: 10.1186/s40478-015-0199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forny-Germano L, Lyra ESNM, Batista AF. et al. Alzheimer's Disease-Like Pathology Induced by Amyloid-beta Oligomers in Nonhuman Primates. J Neurosci. 2014;34(41):13629–13643. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1353-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti MT, Partridge V, Leon WC. et al. Transgenic mice as a model of pre-clinical Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2011;8(1):4–23. doi: 10.2174/156720511794604561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C, Davis FJ, Chauhan BC. et al. Brain transit and ameliorative effects of intranasally delivered anti-amyloid-beta oligomer antibody in 5XFAD mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;35(4):777–788. doi: 10.3233/JAD-122419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight EM, Kim SH, Kottwitz JC. et al. Effective anti-Alzheimer Abeta therapy involves depletion of specific Abeta oligomer subtypes. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2016;3(3):e237. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasool S, Martinez-Coria H, Wu JW. et al. Systemic vaccination with anti-oligomeric monoclonal antibodies improves cognitive function by reducing Abeta deposition and tau pathology in 3xTg-AD mice. J Neurochem. 2013;126(4):473–482. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorostkar MM, Burgold S, Filser S. et al. Immunotherapy alleviates amyloid-associated synaptic pathology in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 12):3319–3326. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevigny J, Chiao P, Bussiere T. et al. The antibody aducanumab reduces Abeta plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2016;537(7618):50–56. doi: 10.1038/nature19323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krafft G, Hefti F, Goure W. et al. ACU-193: A candidate therapeutic antibody that selectively targets soluble beta-amyloid oligomers. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2013;9(4 Supplement):P326. [Google Scholar]

- Savage MJ, Kalinina J, Wolfe A. et al. A sensitive abeta oligomer assay discriminates Alzheimer's and aged control cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurosci. 2014;34(8):2884–2897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1675-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatson JW, Warren V, Abdelfattah K. et al. Detection of beta-amyloid oligomers as a predictor of neurological outcome after brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2013;118(6):1336–1342. doi: 10.3171/2013.2.JNS121771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, O'Malley TT, Kanmert D. et al. A highly sensitive novel immunoassay specifically detects low levels of soluble Abeta oligomers in human cerebrospinal fluid. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0100-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viola KL, Sbarboro J, Sureka R. et al. Towards non-invasive diagnostic imaging of early-stage Alzheimer's disease. Nat Nanotechnol. 2015;10(1):91–98. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krafft GA, Klein WL. ADDLs and the signaling web that leads to Alzheimer's disease. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59(4-5):230–242. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira ST, Klein WL. The Abeta oligomer hypothesis for synapse failure and memory loss in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011;96(4):529–543. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarosz-Griffiths HH, Noble E, Rushworth JV. et al. Amyloid-beta Receptors: The Good, the Bad, and the Prion Protein. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(7):3174–3183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.702704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Carranza DL, Guerrero-Munoz MJ, Sengupta U. et al. Tau immunotherapy modulates both pathological tau and upstream amyloid pathology in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. J Neurosci. 2015;35(12):4857–4868. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4989-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna MR, Kovalevich J, Lee VM. et al. Therapeutic strategies for the treatment of tauopathies: Hopes and challenges. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(10):1051–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MP, Stevens G, Sabo S. et al. Beta/A4-evoked degeneration of differentiated SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. J Neurosci Res. 1994;39(4):377–385. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490390404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Qiu HE, Krafft GA. et al. A beta peptide enhances focal adhesion kinase/Fyn association in a rat CNS nerve cell line. Neurosci Lett. 1996;211(3):187–190. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12761-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Um JW, Strittmatter SM. Amyloid-beta induced signaling by cellular prion protein and Fyn kinase in Alzheimer disease. Prion. 2013;7(1):37–41. doi: 10.4161/pri.22212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Um JW, Kaufman AC, Kostylev M. et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 is a coreceptor for Alzheimer abeta oligomer bound to cellular prion protein. Neuron. 2013;79(5):887–902. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygaard HB, van Dyck CH, Strittmatter SM. Fyn kinase inhibition as a novel therapy for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6(1):8. doi: 10.1186/alzrt238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Felice FG, Velasco PT, Lambert MP. et al. Abeta oligomers induce neuronal oxidative stress through an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-dependent mechanism that is blocked by the Alzheimer drug memantine. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(15):11590–11601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner M, Lacor PN, Velasco PT. et al. Deleterious effects of amyloid beta oligomers acting as an extracellular scaffold for mGluR5. Neuron. 2010;66(5):739–754. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein WL, De Felice FG, Lacor PN, et al. Why Alzheimer's is a disease of memory: Synaptic targeting by pathogenic Abeta oligomers (ADDLs). In: Selkoe DJ, Triller A, Christen Y, et al., editors. Synaptic Plasticity and the Mechanism of Alzheimer's Disease. Springer-Verlag; 2008. pp. 103–132. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao WQ, De Felice FG, Fernandez S. et al. Amyloid beta oligomers induce impairment of neuronal insulin receptors. Faseb j. 2008;22(1):246–260. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7703com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arispe N. Architecture of the Alzheimer's A beta P ion channel pore. J Membr Biol. 2004;197(1):33–48. doi: 10.1007/s00232-003-0638-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Chae SC, Lee DK. et al. Selective neuronal degeneration induced by soluble oligomeric amyloid beta protein. Faseb j. 2003;17(1):118–120. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0987fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Furlow PW. et al. Abeta oligomer-induced aberrations in synapse composition, shape, and density provide a molecular basis for loss of connectivity in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2007;27(4):796–807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3501-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox KC, Marunde MM, Das A. et al. Nanoscale synaptic membrane mimetic allows unbiased high throughput screen that targets binding sites for Alzheimer’s-associated Aβ oligomers. PLoS One. 2014 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi T, Yanazawa M, Sasahara T. et al. K-ATPase alpha3 is a death target of Alzheimer patient amyloid-beta assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(32):E4465–E4474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421182112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein WL. Abeta toxicity in Alzheimer's disease: globular oligomers (ADDLs) as new vaccine and drug targets. Neurochem Int. 2002;41(5):345–352. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi A, Matsumura S, Dezawa M. et al. Isolation and characterization of patient-derived, toxic, high mass amyloid beta-protein (Abeta) assembly from Alzheimer disease brains. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(47):32895–32905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayburt TH, Sligar SG. Membrane protein assembly into Nanodiscs. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(9):1721–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler MA, Denisov IG, Sligar SG. Nanodiscs as a new tool to examine lipid-protein interactions. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;974:415–433. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-275-9_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard L, Tidow H, Clausen MJ. et al. Na(+),K (+)-ATPase as a docking station: protein-protein complexes of the Na(+),K (+)-ATPase. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(2):205–222. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1039-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkuratov EE, Lopacheva OM, Kruusmagi M. et al. Functional Interaction Between Na/K-ATPase and NMDA Receptor in Cerebellar Neurons. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;52(3):1726–1734. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8975-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Cai T. Na+-K+--ATPase-mediated signal transduction: from protein interaction to cellular function. Mol Interv. 2003;3(3):157–168. doi: 10.1124/mi.3.3.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J, Cai T, Yuan Z. et al. Binding of Src to Na+/K+-ATPase forms a functional signaling complex. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(1):317–326. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauren J, Gimbel DA, Nygaard HB. et al. Cellular prion protein mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity by amyloid-beta oligomers. Nature. 2009;457(7233):1128–1132. doi: 10.1038/nature07761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava AN, Redeker V, Fritz N. et al. alpha-synuclein assemblies sequester neuronal alpha3-Na+/K+-ATPase and impair Na+ gradient. EMBO J. 2015;34(19):2408–2423. doi: 10.15252/embj.201591397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom H, Ronnlund D, Scott L. et al. Spatial distribution of Na+-K+-ATPase in dendritic spines dissected by nanoscale superresolution STED microscopy. BMC Neurosci. 2011;12:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-12-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom H, Bernhem K, Brismar H. Sodium pump organization in dendritic spines. Neurophotonics. 2016;3(4):041803. doi: 10.1117/1.NPh.3.4.041803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourenco MV, Clarke JR, Frozza RL. et al. TNF-alpha mediates PKR-dependent memory impairment and brain IRS-1 inhibition induced by Alzheimer's beta-amyloid oligomers in mice and monkeys. Cell Metab. 2013;18(6):831–843. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Guo JP, Schwab C. et al. Selective inhibition of the membrane attack complex of complement by low molecular weight components of the aurin tricarboxylic acid synthetic complex. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(10):2237–2246. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chromy BA, Nowak RJ, Lambert MP. et al. Self-assembly of Abeta(1-42) into globular neurotoxins. Biochemistry. 2003;42(44):12749–12760. doi: 10.1021/bi030029q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers AB. Progress report on Alzheimer's disease 2004-2005. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; National Institutes on Aging; National Institutes of Health. 2005 Contract No.: NIH Publication Number: 05-5724. [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR Jr., Knopman DS, Jagust WJ. et al. Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer's pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(1):119–128. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70299-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georganopoulou DG, Chang L, Nam JM. et al. Nanoparticle-based detection in cerebral spinal fluid of a soluble pathogenic biomarker for Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(7):2273–2276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409336102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox KC, Marunde MR, Das A. et al. Nanoscale Synaptic Membrane Mimetic Allows Unbiased High Throughput Screen That Targets Binding Sites for Alzheimer's-Associated Abeta Oligomers. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0125263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma QL, Yang F, Rosario ER. et al. Beta-amyloid oligomers induce phosphorylation of tau and inactivation of insulin receptor substrate via c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling: suppression by omega-3 fatty acids and curcumin. J Neurosci. 2009;29(28):9078–9089. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1071-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zempel H, Thies E, Mandelkow E. et al. Abeta oligomers cause localized Ca(2+) elevation, missorting of endogenous Tau into dendrites, Tau phosphorylation, and destruction of microtubules and spines. J Neurosci. 2010;30(36):11938–11950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2357-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV. et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416(6880):535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HW, Pasternak JF, Kuo H. et al. Soluble oligomers of beta amyloid (1-42) inhibit long-term potentiation but not long-term depression in rat dentate gyrus. Brain Res. 2002;924(2):133–140. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend M, Shankar GM, Mehta T. et al. Effects of secreted oligomers of amyloid beta-protein on hippocampal synaptic plasticity: a potent role for trimers. J Physiol. 2006;572(Pt 2):477–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. Soluble oligomers of the amyloid beta-protein impair synaptic plasticity and behavior. Behav Brain Res. 2008;192(1):106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH. et al. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer's brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med. 2008;14(8):837–842. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freir DB, Fedriani R, Scully D. et al. Abeta oligomers inhibit synapse remodelling necessary for memory consolidation. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(12):2211–2218. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesne S, Kotilinek L, Ashe KH. Plaque-bearing mice with reduced levels of oligomeric amyloid-beta assemblies have intact memory function. Neuroscience. 2008;151(3):745–749. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poling A, Morgan-Paisley K, Panos JJ. et al. Oligomers of the amyloid-beta protein disrupt working memory: confirmation with two behavioral procedures. Behav Brain Res. 2008;193(2):230–234. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Ma QL, Calon F. et al. Role of p21-activated kinase pathway defects in the cognitive deficits of Alzheimer disease. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(2):234–242. doi: 10.1038/nn1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar GM, Bloodgood BL, Townsend M. et al. Natural oligomers of the Alzheimer amyloid-beta protein induce reversible synapse loss by modulating an NMDA-type glutamate receptor-dependent signaling pathway. J Neurosci. 2007;27(11):2866–2875. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4970-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend M, Qu Y, Gray A. et al. Oral treatment with a gamma-secretase inhibitor improves long-term potentiation in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;333(1):110–119. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.163691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demuro A, Mina E, Kayed R. et al. Calcium dysregulation and membrane disruption as a ubiquitous neurotoxic mechanism of soluble amyloid oligomers. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(17):17294–17300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberdi E, Sanchez-Gomez MV, Cavaliere F. et al. Amyloid beta oligomers induce Ca2+ dysregulation and neuronal death through activation of ionotropic glutamate receptors. Cell Calcium. 2010;47(3):264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo VD, Viola KL, Klein WL. et al. Reversible inactivation of superoxide-sensitive aconitase in Abeta1-42-treated neuronal cell lines. J Neurochem. 2000;75(5):1977–1985. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sponne I, Fifre A, Drouet B. et al. Apoptotic neuronal cell death induced by the non-fibrillar amyloid-beta peptide proceeds through an early reactive oxygen species-dependent cytoskeleton perturbation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(5):3437–3445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206745200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabner BJ, El-Agnaf OM, Turnbull S. et al. Hydrogen peroxide is generated during the very early stages of aggregation of the amyloid peptides implicated in Alzheimer disease and familial British dementia. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(43):35789–35792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500238200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resende R, Ferreiro E, Pereira C. et al. ER stress is involved in Abeta-induced GSK-3beta activation and tau phosphorylation. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86(9):2091–2099. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishitsuji K, Tomiyama T, Ishibashi K. et al. The E693Delta mutation in amyloid precursor protein increases intracellular accumulation of amyloid beta oligomers and causes endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis in cultured cells. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(3):957–969. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder EM, Nong Y, Almeida CG. et al. Regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking by amyloid-beta. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(8):1051–1058. doi: 10.1038/nn1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli F, Tirard M, Lu J. et al. Soluble beta-amyloid1-40 induces NMDA-dependent degradation of postsynaptic density-95 at glutamatergic synapses. J Neurosci. 2005;25(48):11061–11070. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3034-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinitz K, Beck M, Schliebs R. et al. Toxicity mediated by soluble oligomers of beta-amyloid(1-42) on cholinergic SN56.B5.G4 cells. J Neurochem. 2006;98(6):1930–1945. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes-Tavares N, Santos LE, Stutz B. et al. Inhibition of choline acetyltransferase as a mechanism for cholinergic dysfunction induced by amyloid-beta peptide oligomers. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(23):19377–19385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.321448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao WQ, Lacor PN, Chen H. et al. Insulin receptor dysfunction impairs cellular clearance of neurotoxic oligomeric a{beta}. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(28):18742–18753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.011015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Felice FG, Vieira MN, Bomfim TR. et al. Protection of synapses against Alzheimer's-linked toxins: insulin signaling prevents the pathogenic binding of Abeta oligomers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(6):1971–1976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809158106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigino G, Morfini G, Atagi Y. et al. Disruption of fast axonal transport is a pathogenic mechanism for intraneuronal amyloid beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(14):5907–5912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901229106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon WW, Blurton-Jones M, Tu CH. et al. beta-Amyloid impairs axonal BDNF retrograde trafficking. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(5):821–833. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker H, Jurgensen S, Adrover MF. et al. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors are required for synaptic targeting of Alzheimer's toxic amyloid-beta peptide oligomers. J Neurochem. 2010;115(6):1520–1529. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Akama KT, Krafft GA. et al. Amyloid-beta peptide activates cultured astrocytes: morphological alterations, cytokine induction and nitric oxide release. Brain Res. 1998;785(2):195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez S, Baglietto-Vargas D, Caballero C. et al. Inflammatory response in the hippocampus of PS1M146L/APP751SL mouse model of Alzheimer's disease: age-dependent switch in the microglial phenotype from alternative to classic. J Neurosci. 2008;28(45):11650–11661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3024-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varvel NH, Bhaskar K, Patil AR. et al. Abeta oligomers induce neuronal cell cycle events in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2008;28(43):10786–10793. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2441-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar K, Miller M, Chludzinski A. et al. The PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway regulates Abeta oligomer induced neuronal cell cycle events. Mol Neurodegener. 2009;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan SD, Whitehead SN, Swayne LA. et al. Amyloid-beta42 signals tau hyperphosphorylation and compromises neuronal viability by disrupting alkylacylglycerophosphocholine metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(49):20936–20941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905654106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]