Abstract

Context (Background):

Imiquimod (IMQ) 5% cream is an immunomodulatory and antitumorigenic agent, which was used as a topical treatment regimen, who had periocular basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

Aim:

This study aims to present three cases with large BCC at the medial canthal area treated with IMQ 5% cream.

Materials and Methods:

IMQ 5% cream was used in three patients with ages 45, 49, and 73 who preferred medical treatment over surgery. Following incisional biopsy IMQ cream was used once a day, 5 times a week and the patients were followed up weekly during 12 week treatment period and monthly after the clearance of the lesion.

Results:

Erythema and erosion on the surface of the lesion, injection of conjunctiva, burning and itching sensation, epiphora and punctate keratitis were seen in all patients during the treatment period. The ophthalmic side effects could be managed by topical lubricating eye drops and the inflammatory reactions resolved within 1 month after cessation of therapy. The patients were followed up for at least 3 years without tumor recurrence and the biopsies taken from the suspected area were found to be tumor free.

Conclusion:

Surgical excision of carcinoma of the eyelid at medial canthal area can be difficult without causing damage to the lacrimal system and reconstruction of the defect may need grafts or flaps. IMQ may provide an alternative therapy to surgery in certain cases.

Keywords: Imiquimod, medical treatment of basal cell carcinoma of eyelid, periocular basal cell carcinoma

Basal cell carcinomas (BCC) is the most common skin malignancy; constituting 90% of all eyelid malignancies.[1,2,3,4] Surgical excision is the main treatment for periocular BCC. Other treatment modalities including curettage, cryosurgery, laser treatment, surgical excision with predetermined margins of clinically normal tissue, excision under frozen section control, Moh's micrographic surgery, radiotherapy, topical treatment, intralesional treatment, photodynamic therapy, immunomodulators, and chemotherapy have been reported.[5]

Imiquimod (IMQ) 5% cream (Aldara, Meda Pharmaceuticals, Solna, Sweden) is an immunomodulatory and antitumorigenic agent. It acts by stimulating both innate and cell-mediated immunity pathways that activate antigen-presenting cells through toll-like receptor 7 and stimulate cytotoxic T-cells, Langerhans cells, and natural killer cells to produce interferon-gamma and other cytokines, which cause apoptosis.[6] Food and Drug Administration approved IMQ for anogenital warts in 1997 and superficial BCC and actinic keratosis in 2004.[1,3]

In this study, we presented three cases with nodular BCC in the medial canthal region. IMQ was the treatment of choice in these patients because they refused to undergo surgery, which would result in damage to the lacrimal system and reconstructions would need flaps or grafts.

Materials and Methods

IMQ 5% cream was used in three patients who preferred medical treatment of histologically proven nodular BCC at the medial canthal area with topical cream therapy over surgical excision and reconstruction. The ages of the patients were 49, 45 and 73 years, respectively. All lesions were located at the medial canthal area, and the dimensions were 11.5 mm × 9.7 mm, 12.5 mm × 9.8 mm, 9 mm × 10 mm (horizontal x vertical length in mm), respectively. After an incisional biopsy, reports proved histopathology for nodular BCC. Orbital magnetic resonance imaging of the lesions of cases revealed lesions limited to dermis. Risk and complications of surgery of the medial canthal area and the drug complications were thoroughly explained to the patients. Informed consents including off-label usage and potential side effects of IMQ therapy were obtained from the patients in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. All clinical photographs that permit identification of the patient were taken with approval by a signed consent by the patient.

Patients were instructed to apply IMQ 5% cream treatment once a day, 5 times a week. After preparing conjunctival sac with lubricant gel and swabbing the IMQ cream onto the lesion with a safety margin of 5 mm beyond the lesion at bedtime, the patients were instructed to rinse the lesion with soap and water in the morning. The lesions were in contact with the drug for sleeping time and were not to be covered unless needed because of weeping or bleeding. Lubricating eye drops and ointments were instilled for 4 times a day to overcome corneal problems. In case of contact with the eye, the patients were recommended to rinse with 0.9% saline solution. 5-day-treatment regimens were followed by 2 days of the drug-free period.

The patients were followed up weekly with visual acuity and biomicroscopical examination during 12 weeks treatment period and monthly after the clearance of the lesion. Photographs were taken at each visit.

Healing of skin and absence of any suspicious lesion with inspection and palpation were the termination criteria of the treatment process.

Results

At least 16 treatment regimens were required in three patients for complete removal of the lesion. Erythema and erosion on the surface of the lesion with significant inflammatory reaction started 1 week after initiation of local treatment and progressed in the following weeks [Fig. 1]. Conjunctivas of patients were also injected with significant itching, burning sensation, and epiphora. Punctate keratitis was observed especially in the medial and inferior cornea where the drug exposed in all patients. In the follow-up period, ulceration and crusting with a decrease in diameter of the lesions were seen. Despite the proximity of the tumors to the punctum and lacrimal system, cicatricial changes during treatment period did not result in ectropion or a change in eyelid apposition, punctual eversion and/or obstruction of canaliculi in any of the patients. Local reactions were well tolerated by the patients, and no systemic side effects were seen. The ophthalmic side effects could be managed by topical lubricating eye drops and the patients could continue the treatment. The inflammatory reactions resolved within 1 month after cessation of therapy.

Figure 1.

Photographs of patients 1–3 before, during and after treatment. Pretreatment photos of the patients with periocular basal cell carcinomas (1a, 2a, 3a), posttreatment 4th week photo of the treatment in patient 1 (1b), posttreatment 9th week of the treatment in patient 2 (2b), posttreatment 12th week of the treatment in patient 3 (3b), posttreatment photos for each patient (1c, 2c, 3c)

In this first patient, the lesion resolved after the treatment leaving a suspicious lesion of 2 mm × 2 mm in diameter. Excisional biopsy from the suspected area was performed after cessation of treatment and histology revealed BCC with tumor-free margins. The lesion did not recur in the 2½ years follow-up period. Complete removal of the lesions was histologically proven in the other patients by taking biopsy of suspicious sites, and histology revealed inflammatory fibrosis with mononuclear cell infiltration. These two patients were followed up for 2 years without any recurrence.

Discussion

Several studies have shown the effect of IMQ cream on BCC away from eyelid. The SINS trial, which is a randomized controlled trial of excisional surgery versus IMQ 5% cream for nodular and superficial BCC management, revealed that better cosmetic results were obtained with IMQ with 90% success rate in superficial BCC and 70% in nodular BCC.[7] They suggested that “treat with the cream first and see what's left policy” might become a viable and cost-effective future treatment.

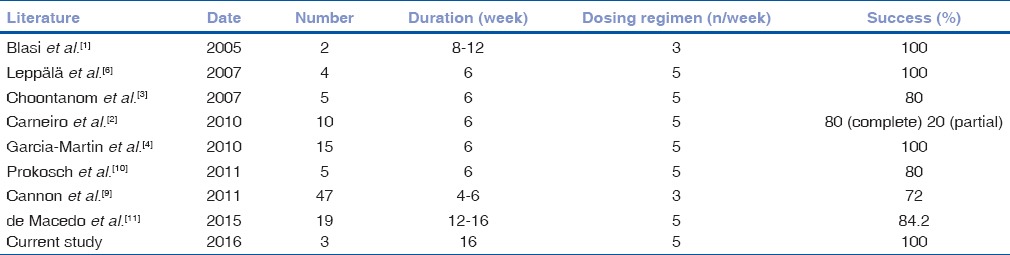

The manufacturer does not recommend the use of IMQ in the periocular area thus the cream base includes stearyl and benzyl alcohol.[1,8,9] However, studies in the previous years reported the benefit of IMQ for periocular lesions [Table 1].

Table 1.

Summary of studies in the literature and our study where Imiquimod 5% cream is used for the medical treatment of periocular basal cell carcinoma

Surgery still remains the choice of treatment that permits histopathologic margin assessment and decision to use IMQ should be made on each case, individually. However, surgical excision of carcinoma of the eyelid can be difficult without causing damage to the lacrimal system, especially in patients who have carcinoma near medial canthal region, as in our case series, and reconstruction of the defect may need grafts or flaps in other periocular tissues. In the study by Tinelli et al. it was reported that patients are usually more concerned with their cosmetic outcomes and side effects that might experience over and above their chance of clearance and cost.[12]

Ideal mode of the treatment of periocular lesions with IMQ varies in the literature. Blasi et al. reported 100% success rate with three times per week for 8–12 weeks in two patients, however, Cannon et al. achieved 72% success rate with same dosing regimen for 4–6 weeks.[1,9] Generally accepted dosing regimen, which is five times a week for 6 weeks, reveals 80%–100% success rate.[2,3,4,6,10,11] We treated our patient with nodular BCC five times per week for 16 weeks. Carneiro et al. reported that 6 weeks was an adequate time for superficial BCC and recommended longer treatment in nodular BCC, which was 8–16 weeks.[2]

Ocular side effects

Erythema, itching, and scaling at the application site were the most common side effects seen in all patients. Mild to severe conjunctivitis, ocular stinging, diffuse punctate keratitis, preseptal cellulitis, microbial keratitis (Staphylococcus aureus keratitis which responded to topical antibiotics), cicatricial ectropion was reported by Cannon et al.[9] Erythema and crusting were seen in our patients that were tolerable and healed after cessation of therapy. Brannan et al. also reported cicatricial ectropion after the treatment of Bowen disease with IMQ and the patient underwent surgery for repair of ectropion.[13] We did not observe cicatricial ectropion requiring surgery in our patients.

For the management of ophthalmic side effects discontinuing treatment and allowing a resting period was recommended.[9] Brannan et al. suggested that reducing the dosing regimen might reduce the side effects.[13] The local inflammatory reactions noted in our patients were acceptable in the treatment of a malignant condition. We preferred to allow the patients to extend the rest periods, when the side effects were severe, instead of reducing the dosing regimen in order not to decrease the efficacy of the treatment. However, de Macedo et al. reported that the only patient with recurrence of BCC was the one who interrupted therapy for 2 weeks.[11] Concurrent artificial drops as suggested by Blasi et al. were prescribed to the patients, also.[1] Leppälä et al. recommended use of retinoic acid cream administered to the subfornicial space before IMQ treatment.[6] Because of prescription of lubricants during treatment, mild punctate keratitis was seen in our patients. Ocular side effects resolved in 1-week rest periods and the patients did not discontinue the therapy. The lesions of the patients were resolved after the 16-week period. However, none of the systemic side effects such as flu-like symptoms, nausea, headache, myalgia, fatigue, and fever were seen in our patients.

The reported success rate for periocular BCC was between 80% and 100%.[1,2,3,4,6,9,10,11] Choontanom et al. and Prokosh et al. reported 7-year follow-up without tumor recurrence.[3,10] Largest IMQ-treated periocular BCC with histological follow-up beyond 3 years was published by de Macedo et al.[11] The absence of tumor was confirmed by histopathological analysis by Leppälä et al. and Carneiro et al. also.[2,6] However, de Macedo et al. reported tumor recurrence in one patient after 2 years.[11] For cosmetic reasons, histological clearance of tumor after IMQ therapy was not confirmed by biopsy in other studies.[1,3,10] In the first case, we biopsied a suspicious lesion with 2 mm × 2 mm diameter in the center of treatment area 3 months after 16-week treatment regimen to confirm the area was tumor free and histology revealed BCC with tumor-free margins. The treated areas of other two patients were biopsied after 3 months also, which showed inflammatory fibrosis.

The investigators noted two negative prognostic factors as; tumors that were >1 cm., which require longer treatment with IMQ to promote resolution, and compromised immune function, which greatly reduced the efficacy of IMQ.[4] However, in the study of Carneiro et al. nodular BCC lesions more than 2 cm resolved with IMQ with 12 weeks treatment duration.[2] de Macedo et al. reported 19 patients, 11 of whom had nodular BCC more than 1 cm, with a treatment time between 12 and 16 weeks.[11] Similarly, in this study although the lesions were more than 1 cm and complete resolution was obtained after the 16-week treatment regimen.

Costales-Álvarez et al. reported two cases one with Alzheimer Disease and the other with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome with encephalopathy and facial dystrophy which were not suitable for surgery and concluded that IMQ was an alternative to surgical treatment in those cases where surgery was not possible.[14] Although surgery is the first-line treatment in these lesions, in case of refusal of surgical treatment, radiotherapy or cryotherapy, when other therapies have failed or are not possible, such as elderly patients, patients requiring long-term care facilities, patients on anticoagulant treatment, patients with either multiple lesions, or superficial diffuse lesions and/or with lesions in regions where reconstruction is difficult, “Treat with the cream first see what's left” policy can be preferred.

In our cases, posttreatment follow-up times were minimum 3 years, which were relatively shorter than those, published. We will continue to follow-up the patients closely with frequent intervals for managing any recurrent lesion without delay. Larger study groups with longer follow-up terms are required to confirm the efficacy of IMQ administration in periocular BCC. In summary, IMQ may provide an alternative therapy to surgery in certain cases.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Blasi MA, Giammaria D, Balestrazzi E. Immunotherapy with imiquimod 5% cream for eyelid nodular basal cell carcinoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:1136–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carneiro RC, de Macedo EM, Matayoshi S. Imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of periocular basal cell carcinoma. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26:100–2. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181b8dd71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choontanom R, Thanos S, Busse H, Stupp T. Treatment of basal cell carcinoma of the eyelids with 5% topical imiquimod: A 3-year follow-up study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;245:1217–20. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0561-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Martin E, Idoipe M, Gil LM, Pueyo V, Alfaro J, Pablo LE, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of imiquimod 5% cream to treat periocular basal cell carcinomas. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2010;26:373–9. doi: 10.1089/jop.2010.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bath-Hextall F, Bong J, Perkins W, Williams H. Interventions for basal cell carcinoma of the skin: Systematic review. BMJ. 2004;329:705. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38219.515266.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leppälä J, Kaarniranta K, Uusitalo H, Kontkanen M. Imiquimod in the treatment of eyelid basal cell carcinoma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007;85:566–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozolins M, Williams HC, Armstrong SJ, Bath-Hextall FJ. The SINS trial: A randomised controlled trial of excisional surgery versus imiquimod 5% cream for nodular and superficial basal cell carcinoma. Trials. 2010;11:42. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsang HH, Huynh NT, Hollenbach E. Topical therapy with imiquimod for eyelid lesion. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;34:179–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cannon PS, O’Donnell B, Huilgol SC, Selva D. The ophthalmic side-effects of imiquimod therapy in the management of periocular skin lesions. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:1682–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.178202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prokosch V, Thanos S, Spaniol K, Stupp T. Long-term outcome after treatment with 5% topical imiquimod cream in patients with basal cell carcinoma of the eyelids. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249:121–5. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1526-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Macedo EM, Carneiro RC, de Lima PP, Silva BG, Matayoshi S. Imiquimod cream efficacy in the treatment of periocular nodular basal cell carcinoma: A non-randomized trial. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015;15:35. doi: 10.1186/s12886-015-0024-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tinelli M, Ozolins M, Bath-Hextall F, Williams HC. What determines patient preferences for treating low risk basal cell carcinoma when comparing surgery vs. imiquimod?. A discrete choice experiment survey from the SINS trial. BMC Dermatol. 2012;12:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-12-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brannan PA, Anderson HK, Kersten RC, Kulwin DR. Bowen disease of the eyelid successfully treated with imiquimod. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;21:321–2. doi: 10.1097/01.iop.0000170421.07098.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costales-Álvarez C, Álvarez-Coronado M, Rozas-Reyes P, González-Rodríguez CM, Fernández-Vega L. Topical imiquimod 5% as an alternative therapy in periocular basal cell carcinoma in two patients with surgical contraindication. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.oftal.2016.07.002. pii: S0365-669130123-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]