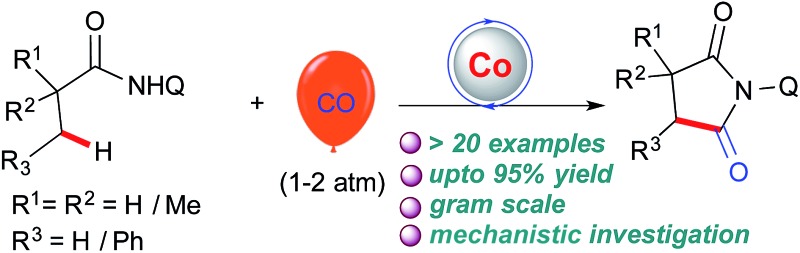

A general efficient regioselective cobalt catalyzed carbonylation of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds of aliphatic amides was demonstrated using atmospheric (1–2 atm) carbon monoxide as a C1 source.

A general efficient regioselective cobalt catalyzed carbonylation of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds of aliphatic amides was demonstrated using atmospheric (1–2 atm) carbon monoxide as a C1 source.

Abstract

A general efficient regioselective cobalt catalyzed carbonylation of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds of aliphatic amides was demonstrated using atmospheric (1–2 atm) carbon monoxide as a C1 source. This straightforward approach provides access to α-spiral succinimide regioselectively in a good yield. Cobalt catalyzed sp3 C–H bond carbonylation is reported for the first time including the functionalization of (β)-C–H bonds of α-1°, 2°, 3° carbons and even internal (β)-C–H bonds. Our initial mechanistic investigation reveals that the C–H activation step is irreversible and will possibly be the rate determining step.

Introduction

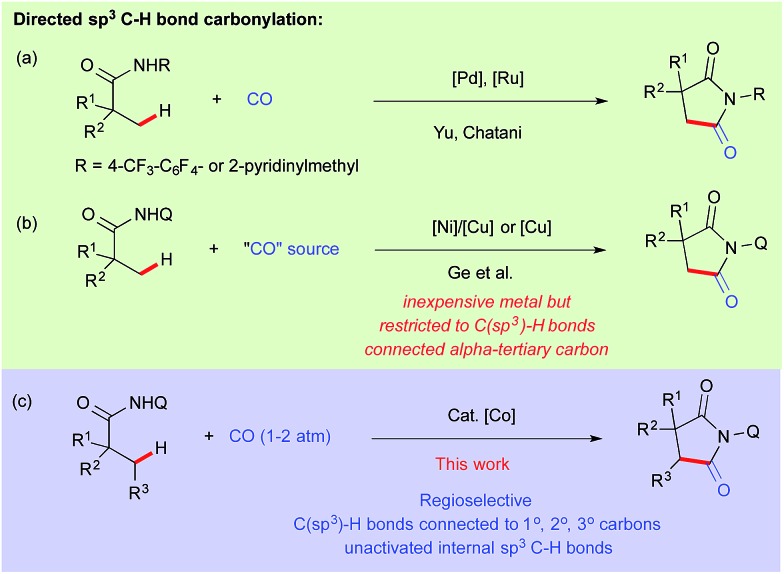

Catalytic carbonylation is one of the most straightforward processes for the production of carbonyl compounds both in academia and industry.1 Insertion of CO into carbon–hydrogen bonds has become even more interesting provided that the catalyst has the ability to activate both inert C–H bonds and to bind π-acidic carbon monoxide.2 In this regard, Shunsuke Murahashi reported the first effective catalytic C–H carbonylation of benzaldimine in 1955 using a low valent cobalt(0) complex.3 Since then, several reports have been documented for catalytic C(sp2)–H bond carbonylation.4 However the corresponding extension to carbonylation of C(sp3)–H bonds is rare and only a handful of examples have been reported in the literature.5 After the pioneering work of Tanaka et al. for photocatalytic carbonylation of alkanes,6 Chatani reported the directing group assisted C–H carbonylation of α-C(sp3)–H bonds adjacent to nitrogen.7 In 2010–11, Yu and Chatani independently reported the site-selective C(sp3)–H carbonylation of aliphatic amide using Pd and Ru based catalysts, while the former used oxidative conditions, the latter proceeded through a metal-hydride pathway (Scheme 1a).8–10 We assumed that it would be more rational to choose a metal abundantly present in nature compared to precious metals in terms of cost effectiveness and the unexploited inherent properties exhibited by them.11 Utilization of 8-aminoquinoline as a bidentate auxiliary for C–H bond functionalization was first reported by Daugulis,12 and later developed by Chatani13 and others14 for several profitable applications using first row late transition metal precursors.

Scheme 1. Carbonylation of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds.

Using this approach, Ge et al. reported recently the carbonylation of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds with Ni–Cu/Cu as a catalyst using DMF and nitromethane as a carbonyl sources.15 But the presented nickel–copper/copper catalyzed carbonylation was limited to β-C(sp3)–H bonds connected to α-tertiary carbon (Scheme 1b). On the other hand, cobalt seems to be a very promising alternative metal catalyst for various C(sp2)–H bond functionalizations.11a,b,16 Very recently Ge and Zhang independently reported cobalt catalyzed intramolecular cyclization through activation of directed C(sp3)–H bonds.17 Daugulis reported lately, cobalt catalyzed o-C(sp2)–H bond carbonylation of benzamides at room temperature.16n We have previously demonstrated the activation of C(sp3)–H bonds using Cp*Co(iii) for C–H alkenation with alkynes and C–H amidation with oxazolone.18 Inspired by these results and based on our continuous efforts on the development of cobalt catalyzed C–H bond functionalization,19 we report herein the first regio- and site-selective cobalt catalyzed carbonylation of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds including terminal and internal C–H bond connected α-1°, 2° and 3° carbons (Scheme 1c).

Results and discussion

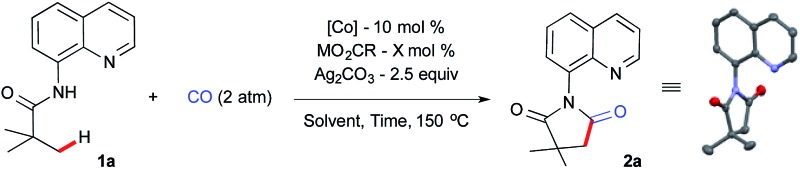

We began our investigation using aliphatic amide 1a, 2 atm CO gas as a C1 source with a catalytic amount of simple Co(OAc)2, metal carboxylate and silver carbonate as an oxidant at 150 °C for 36 h in chlorobenzene (0.5 mL). The optimization results are summarized in Table 1. Initial screening of different metal carboxylates revealed that a good yield of 2a was obtained with sodium benzoate (50 mol%) as an additive, which is also an optimal reaction parameter for intramolecular β-sp3 C–H bond amidation17a (Table 1, entry 1–4). Lowering the reaction concentration did not provide any further improvement (entry 5). A small amount of sodium benzoate turned out to be crucial for high product formation with cobalt(ii) (entry 6 and 7).

Table 1. Optimization studies and control experiments a .

| ||||

| Entry | [Co] | MCO2R (mol%) | Oxidant | Yield b |

| 1 | Co(OAc)2 | NaOPiv (50) | Ag2CO3 | 27 |

| 2 | Co(OAc)2 | Mn(OAc)3 (50) | Ag2CO3 | n.r. |

| 3 | Co(OAc)2 | NaO2CPh (50) | Ag2CO3 | 67 |

| 4 | Co(OAc)2 | NaO2CMes (50) | Ag2CO3 | 49 |

| 5 | Co(OAc)2 | NaO2CPh (50) | Ag2CO3 | 53 c |

| 6 | Co(OAc)2 | NaO2CPh (100) | Ag2CO3 | 43 |

| 7 | Co(OAc)2 | NaO2CPh (20) | Ag2CO3 | 76 |

| 8 | Co(OAc)2 | NaO2CPh (20) | Ag2CO3 | 70 d |

| 9 | Co(OAc)2 | NaO2CPh (20) | Ag2CO3 | 79 d , e |

| 10 | Co(OAc)2 | NaO2CPh (20) | Ag2CO3 | 87 d , f |

| 11 | Co(acac)2 | NaO2CPh (20) | Ag2CO3 | 86 d , f |

| 12 | Co(acac)3 | NaO2CPh (20) | Ag2CO3 | 87 d , f |

| 13 | Co2(CO)8 | NaO2CPh (20) | Ag2CO3 | 68 d , f |

| 14 | CoBr2 | NaO2CPh (20) | Ag2CO3 | 61 d |

| 15 | Co(acac)2 | NaO2CPh (20) | Ag2CO3 | 95 d , g |

| 16 | [Co(Piv)2]2 | — | Ag2CO3 | 55 d , g |

| 17 | Co(acac)3 | — | Ag2CO3 | 92 d , g |

aAll reactions reagents were added under argon atmosphere unless otherwise stated using 1a/[Co]/NaO2CR/Ag2CO3 in 0.2/0.02/0.02–0.05/0.5 mmol using chlorobenzene (0.5 mL) as a solvent at room temperature and then pressurized with CO (2 atm) at 150 °C for 36 h.

bIsolated yield.

c1 mL of PhCl was used.

dReaction performed for 24 h.

e20 mol% of [Co] was used.

f3 equiv. of Ag2CO3 was used.

gTFT (0.5 mL) was used as a solvent.

There was no significant change in yield when the reaction time was reduced to 24 h or by increasing the catalyst loading to 20 mol% (entries 8 and 9). To our delight, a small increment in the silver carbonate gave excellent product formation after 24 h (entry 10). Next, we examined various cobalt sources from different oxidations states. It was revealed that Co(ii) and Co(iii) gave excellent yields whereas Co(0) and Co(ii)Br2 gave moderate yields (entries 11–14). After a brief solvent screening,20 we found out that α,α,α-trifluorotoluene (TFT) was the best solvent, which provided 95% of the succinimide 2a under our optimized reaction parameters (entry 15). A well-defined, isolated cobalt-pivalate dimer21 was used as a catalyst without any additive and this resulted in a 55% yield (entry 16). We further confirmed that the direct use of the Co(iii) precursor in the absence of the sodium benzoate provides 2a in 92% yield and the structure of 2a was confirmed by X-ray crystallography (entry 17).22

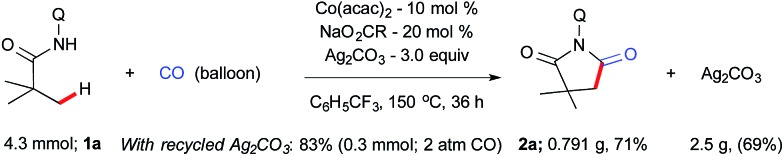

Prior to the scope of the reaction, we examined the scalability of the reaction. A gram scale reaction was performed with 1a using atmospheric CO gas and provides succinimide 2a in 71% yield after 36 h (Scheme 2) and silver carbonate was regenerated from the residue in 69% (2.5 g) yield using the known literature procedure.16e,23 The recycled silver carbonate was used for C–H carbonylation and resulted in 83% of 2a under standard conditions (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Gram scale synthesis of succinimide.

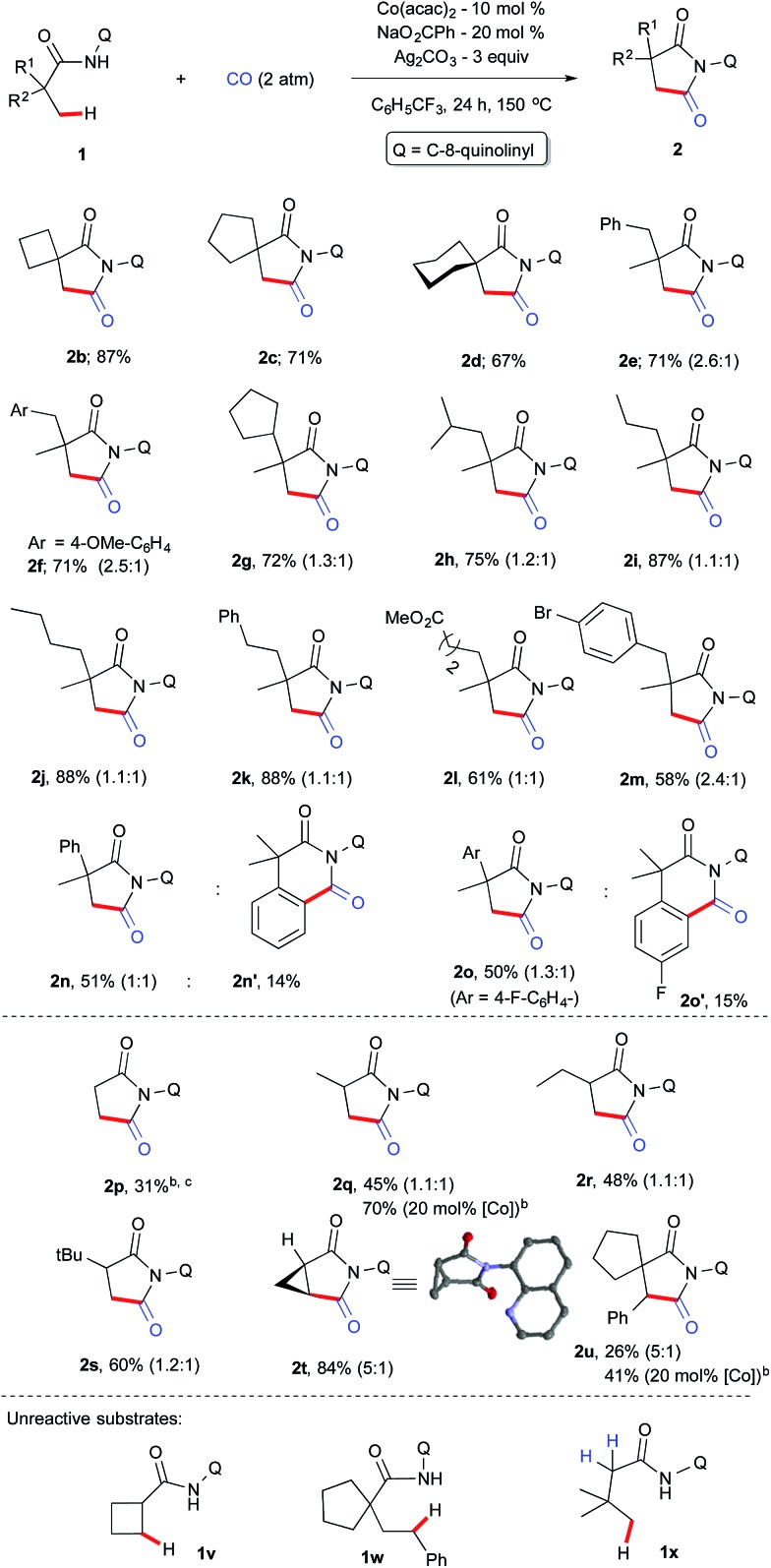

With the optimized conditions in hand, we next investigated the scope of the aliphatic amides and the results are depicted in Scheme 3. Architecturally interesting spiral succinimides possessing a 4-, 5-, 6-membered ring on the backbone were achieved in good yields (2b–d). Replacing one of the methyl groups from 1a with a benzyl, 4-OMe-benzyl, cyclopentyl, isopropyl or alkyl chain at the α-tertiary center gave the desired succinimides in high yields (2e–j). Phenyl, ester, and –Br substituents on the backbone were tolerated (2k–m). Next, the reactivity difference between C(sp2)–H and C(sp3)–H bonds was investigated for cyclocarbonylation. It was found out that carbonylation of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds was favoured over C(sp2)–H bonds (2n–o) and only 2o′ was obtained in 15% yield in addition to 2o (50%). This may be due to the fact that the former proceeds via facile 5-membered cyclocobaltation while the latter proceeds through a 6-membered metallocycle. Furthermore, we explore the possibility of activating β-C(sp3)–H bonds next to an α-secondary and primary carbon center, which is much more challenging (this has not been explored before for carbonylation using first row transition metals) than a C–H bond next to an α-tertiary carbon. Gratifyingly, propanamide (1p) and α-methylpropanamide (1q) underwent cyclocarbonylation albeit in a moderate yield (2p, 2q) but the mass of the product can be improved if we prolong the reaction to 36 h with a 20 mol% cobalt catalyst.

Scheme 3. Scope and limitation. aThe number in parenthesis is the ratio of diastereomer. b36 h instead of 24 h. cPhCl as a solvent.

Systematic increase of bulkiness by incorporating a –Et and –tBu group did not significantly alter the isomeric ratio (2r–s). Furthermore, to our delight, an internal C(sp3)–H bond was carbonylated in the case of 1t and 1u, and it resulted in the formation of substituted and structurally strained succinimides (2t & 2u) and X-ray crystallography further confirmed the structure of 2t.22 The reactivity of 1u was documented for the first time via internal β-C(sp3)–H carbonylation. To understand the reaction mechanism, several experiments were carried out as displayed in Scheme 4.

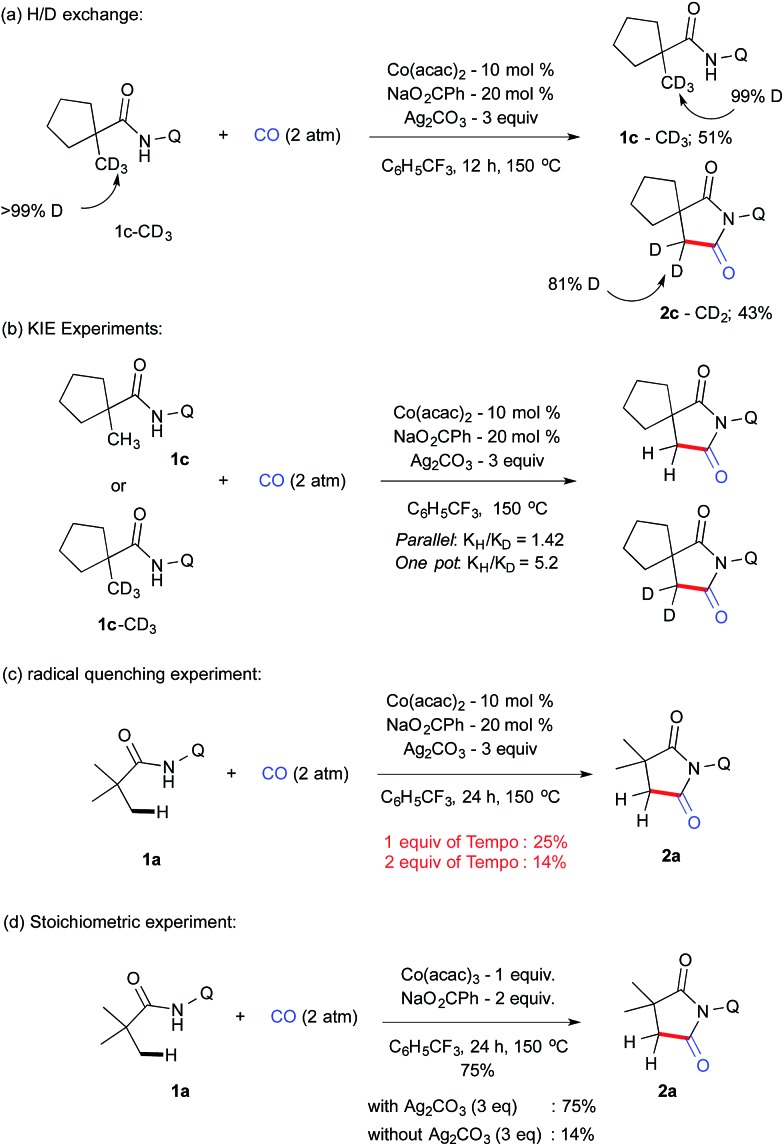

Scheme 4. H/D exchange, KIE and control experiments.

1c–CD3 employed under our reaction conditions gave the corresponding carbonylation product 2c–CD2 (43%) along with the recovered starting material 1c–CD3 (51%) after 12 h (Scheme 4a). Analysis of the isolated compound revealed that 1c–CD3 did not have any H/D exchange, which indicates that the C–H activation step is irreversible. KIE values of 1.42 and 5.2 were determined from parallel and one-pot experiments using 1c–CH3 and 1c–CD3 (Scheme 4b). This value possibly suggests that the cleavage of C–H bonds is the rate-determining step. Next, we performed a series of control experiments e.g. addition of a stoichiometric amount of a radical scavenger such as TEMPO (1 eq.), which drastically reduces the yield of 2a, which further reduced to 14% when 2 equiv. of TEMPO was employed (Scheme 4c). Although there is no adduct possible to isolate from the mixture, the present result suggests that the possibility of the SET pathway may also to be considered. In addition, we have also carried out the reaction with a stoichiometric amount of Co(iii) to gain insight into the possibility of Co(iii) or Co(iv) intermediates involved in the catalytic cycle with and without Ag2CO3. In line with radical experiments, 1 eq. of CoIII(acac)3 without silver carbonate gave 14% of 2a compared to a 75% mass of 2a which was isolated with silver carbonate. These results indicate that Co(iv) was involved in reductive elimination instead of Co(iii) (scheme 4d).

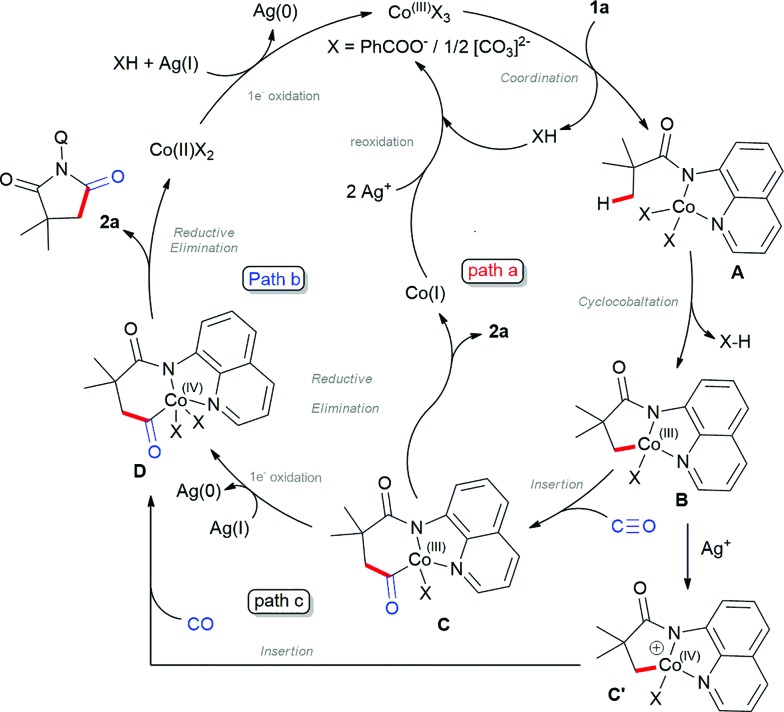

Based on the control experiments and previous reports on β-C(sp3)–H bond activation,17 we propose the plausible mechanism as shown in Scheme 5. Initial oxidation of Co(ii) to Co(iii) instigated by Ag+ (confirmed by UV-Vis spectra),20 which subsequently coordinated with 1a via N,N-coordination (initial deprotonation possibly by silver carbonate) led to intermediate A. Then, carboxylate/carbonate assisted deprotonation provides cobaltacycle B. Co(iii) intermediate B coordinates with CO followed by insertion into the C–Co(iii), which gave the intermediate C, which may either undergo reductive elimination to Co(i) and reoxidized by silver to active Co(iii) species as depicted in path a.16a–g Alternatively, intermediate C will undergo one electron oxidation to Co(iv), which will undergo reductive elimination to 2a and regenerate Co(ii) (path b). At the same time, one may also consider that intermediate B will undergo one electron oxidation to C′ which then subsequently insert CO between Co–C and lead to D (path c), which further undergoes reductive elimination. Although the final solution cannot be given for the mechanism at this stage, control experiments suggest that path b or c may be favoured over path a.

Scheme 5. Proposed mechanism.

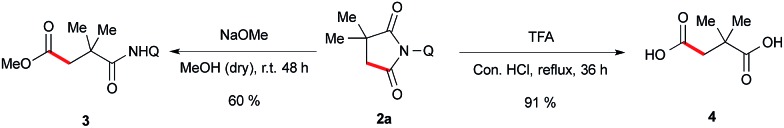

To validate the synthetic utility of this method, we have performed a two ring opening reaction with 1a to obtain 1,4-dicarbonyl compound 3 and 1,4-dicarboxylicacid 4 in good yields under the standard reaction conditions (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6. Synthetic applications.

Conclusions

We have developed a new protocol for cobalt catalyzed site-selective carbonylation of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds under atmospheric CO pressure to access various succinimide derivatives that are active against seizures (anticonvulsant ethosuximide). Our initial mechanistic investigation reveals that the involvement of a one electron process operated in the catalytic cycle and the reaction may proceed through Co(iv) to Co(ii) (Scheme 5, path b or c). Studies to further extend this new reactivity to develop new medicinal compounds and materials are currently underway. Further understanding of the mechanism including the SET process, isolation of stoichiometric intermediates is presently on going in our laboratory.

Acknowledgments

Financial support provided by SERB (EMR2016/000136) to support this research work is gratefully acknowledged. NB thanks to CSIR for his fellowship.

Footnotes

References

- Beller M., Catalytic carbonylation reactions, topic in organometallic Chemistry, Springer, 2006, pp. 1–283. [Google Scholar]

- Gadge S. T., Gautam P., Bhanage B. M., Chem. Rec., 2016, 16 , 835 –856 , and references therein . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murahashi S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955;77:6403–6404. [Google Scholar]

- Selected recent reviews see: ; (a) Zhu R.-Y., Farmer M. E., Chen Y.-Q., Yu J. Q. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:10578–10599. doi: 10.1002/anie.201600791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gao K., Yoshikai N. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:1208. doi: 10.1021/ar400270x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wu X.-F., Neumann H., Beller M. ChemSusChem. 2013;6:229–241. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201200683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wu X.-F., Neumann H., Beller M. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:1–35. doi: 10.1021/cr300100s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Colby D. A., Bergmann R. G., Ellman J. A. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:624–655. doi: 10.1021/cr900005n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Brennuführer A., Neumann H., Beller M. ChemCatChem. 2009;1:28–41. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Li H., Li B.-J., Shi Z.-J. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2011;1:191–206. [Google Scholar]; (b) Crabtree R. H. J. Organomet. Chem. 2004;689:4083–4091. [Google Scholar]

- Sakakura T., Sodeyama T., Sasaki K., Wada K., Tanaka M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:7221–7229. [Google Scholar]

- Chatani N., Asaumi T., Ikeda T., Yorimitsu S., Ishii Y., Kakiuchi F., Murai S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:12882–12883. doi: 10.1021/ja011540e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo E. J., Wasa M., Yu J.-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:17378–17380. doi: 10.1021/ja108754f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Hasegawa N., Charra V., Inoue S., Fukumoto Y., Chatani N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:8070–8073. doi: 10.1021/ja2001709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hasegawa N., Shibata K., Charra V., Inoue S., Fukumoto Y., Chatani N. Tetrahedron. 2013;69:4466–4472. [Google Scholar]

- Selected other recent reports on Pd Catalyzed sp3 C–H bond carbonylation, see: ; (a) Wang P.-L., Li Y., Wu Y., Li C., Lan Q., Wang X.-S. Org. Lett. 2015;17:3698–3701. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang C., Zhang L., Chen C., Han J., Yao Y., Zhao Y. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:4610–4614. doi: 10.1039/c5sc00519a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) McNally A., Haffemayer B., Collings B. S. L., Gaunt M. J. Nature. 2014;510:129–133. doi: 10.1038/nature13389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Xie P., Xie Y., Qian B., Zhou H., Xia C., Huang H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:9902–9905. doi: 10.1021/ja3036459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Stahl S. S., Labinger J. A., Bercaw J. E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998;37:2180–2192. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980904)37:16<2180::AID-ANIE2180>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Asadullah M., Kitamura T., Fujiwara Y. Chem. Lett. 1999;28:449–450. [Google Scholar]

- Selected recent reviews on first row transition metal catalysed C–H bond functionalization see: ; (a) Wei D., Zhu X., Niu J.-L., Song M.-P. ChemCatChem. 2016;8:1242–1263. [Google Scholar]; (b) Moselage N., Li J., Ackermann L. ACS Catal. 2016;6:498–525. [Google Scholar]; (c) Yoshikai N. ChemCatChem. 2015;7:732–734. [Google Scholar]; (d) Hyster T. Catal. Lett. 2015;145:458–467. [Google Scholar]; (e) Bauer I., Knölker H. J. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:3170–3387. doi: 10.1021/cr500425u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Tasker S. Z., Standley E. A., Jamison T. F. Nature. 2014;509:299–309. doi: 10.1038/nature13274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Kulkarni A. A., Daugulis O. Synthesis. 2009:4087–4109. [Google Scholar]

- Zaitsev V. G., Shabashov D., Daugulis O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13154–13155. doi: 10.1021/ja054549f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Aihara Y., Chatani N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:898–901. doi: 10.1021/ja411715v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Aihara Y., Tobisu M., Fukumoto Y., Chatani N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:15509–15512. doi: 10.1021/ja5095342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kubo T., Aihara Y., Chatani N. Chem. Lett. 2015;44:1365–1367. [Google Scholar]

- Selected recent reviews on the use of 8-aminoquinoline as a directing group, see: ; (a) Misal Castro L. C., Chatani N. Chem. Lett. 2015;44:410–421. [Google Scholar]; (b) Rouquet G., Chatani N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:11726–11743. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Corbet M., Decampo F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:9896–9898. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Matsubara T., Asako S., IIies E., Nakamura E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:646–649. doi: 10.1021/ja412521k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Wu X., Miao J., Li Y., Li G., Ge H. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:5260–5264. doi: 10.1039/c6sc01087c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wu X., Zhao Y., Ge H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:4924–4927. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b01671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selected references high valent in cobalt catalyzed C(sp2)–H bond functionalization see: ; (a) Prakash S., Muralirajan K., Cheng C.-H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:1844–1848. doi: 10.1002/anie.201509316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Du C., Li P.-X., Zhu X., Suo J.-F., Niu J.-L., Song M.-P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:13571–13575. doi: 10.1002/anie.201607719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Maity S., Kancherla R., Dhawa U., Hoque E., Pimparkar S., Maiti D. ACS Catal. 2016;6:5493–5499. [Google Scholar]; (d) Lerchen A., Vásquez-Céspedes S., Glorius F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:3208–3211. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Tan G., He S., Huang X., Liao X., Cheng Y., You J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:10414–10418. doi: 10.1002/anie.201604580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Manoharan R., Sivakumar G., Jeganmohan M. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:10533–10536. doi: 10.1039/c6cc04835h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Yamaguchi T., Kommagalla Y., Aihara Y., Chatani N. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:10129–10132. doi: 10.1039/c6cc05330k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Kong L., Yu S., Zhou X., Li X. Org. Lett. 2016;18:588–591. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Hummel J. R., Ellman J. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:490–498. doi: 10.1021/ja5116452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Patel P., Chang S. ACS Catal. 2015;5:853–858. [Google Scholar]; (k) Wang H., Koeller J., Liu W., Ackermann L. Chem.–Eur. J. 2015;21:15525–15528. doi: 10.1002/chem.201503624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Zhang Z.-Z., Bin L., Wang C.-Y., Shi B.-F. Org. Lett. 2015;17:4094–4097. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Grigorjeva L., Daugulis O. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:10209–10212. doi: 10.1002/anie.201404579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Grigorjeva L., Daugulis O. Org. Lett. 2014;16:4688–4690. doi: 10.1021/ol502007t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (o) Yoshino T., Ikemoto H., Matsunaga S., Kanai M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:2207–2211. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Wu X., Yang K., Zhao Y., Sun H., Li G., Ge H. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6462–6471. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang J., Chen H., Lin C., Liu Z., Wang C., Zhang Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:12990–12996. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b07424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Sen M., Emayavaramban B., Barsu N., Premkumar J. R., Sundararaju B. ACS Catal. 2016;6:2792–2796. [Google Scholar]; (b) Barsu N., Rahman Md. A., Sen M., Sundararaju B. Chem.–Eur. J. 2016;22:9135–9138. doi: 10.1002/chem.201601597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Kalsi D., Laskar R. A., Barsu N., Premkumar J. R., Sundararaju B. Org. Lett. 2016;18:4198–4201. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Barsu N., Sen M., Sundararaju B. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:1338–1341. doi: 10.1039/c5cc08736h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Barsu N., Kalsi D., Sundararaju B. Chem.–Eur. J. 2015;21:9364–9368. doi: 10.1002/chem.201500639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Sen M., Kalsi D., Sundararaju B. Chem.–Eur. J. 2015;21:15529–15533. doi: 10.1002/chem.201503643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kalsi D., Sundararaju B. Org. Lett. 2015;17:6118–6121. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See ESI.

- Aromi G., Batsonov A. S., Christian P., Helliwell M., Parkin A., Parsons S., Smith A. A., Timco G. A., Winpenny R. E. P. Chem.–Eur. J. 2003;9:5142–5161. doi: 10.1002/chem.200304993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See notes for more information.

- Catalytic carbonylation was performed using recycled silver carbonate, which resulted in 83% isolated yield of succinimide 2a under the standard reaction conditions

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.