Abstract

Objective

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the sixth most common cancer worldwide and third most common cause of cancer related death, is closely associated with the presence of cirrhosis. Survival is determined by the stage of the cancer, with asymptomatic small tumours being more amenable to treatment. Early diagnosis is dependent on regular surveillance and the primary objective of this survey was to gain a better understanding of the baseline attitudes towards and provision of ultrasound surveillance (USS) HCC surveillance in the UK. In addition, information was obtained on the stages of cancer of the patients being referred to and discussed at regional multidisciplinary team meetings.

Design

UK hepatologists, gastroenterologists and nurse specialists were sent a questionnaire survey regarding the provision of USS for detection of HCC in their respective hospitals.

Results

Provision of surveillance was poor overall, with many hospitals lacking the necessary mechanisms to make abnormal results, if detected, known to referring clinicians. There was also a lack of standard data collection and in many hospitals basic information on the number of patients with cirrhosis and how many were developing HCC was not known. For the majority of new HCC cases was currently being made only at an incurable late stage (60%).

Conclusions

In the UK, the current provision of USS based HCC surveillance is poor and needs to be upgraded urgently.

Keywords: HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA, CHRONIC LIVER DISEASE, IMAGING, CIRRHOSIS

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common cancer worldwide and the third most common cause of cancer related death.1 2 Its development is closely associated with the presence of cirrhosis. Although HCC is seen in patients without cirrhosis (in particular those with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection), in the UK, cirrhosis is observed in cases with chronic hepatitis C (CHC) infection and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) forming an increasing proportion of patients with HCC.3 4 Long-term survival is predicated by tumour stage at disease presentation. Patients who have their cancer detected at an early stage have a wider range of therapeutic choices and are more likely to live longer, when compared with those who present late.5–7 Thus, liver ultrasound scanning (US) is used in the belief that regular scanning will increase the likelihood of HCC being diagnosed at an earlier stage. Yet, the role of surveillance is controversial. Some studies have doubted its efficacy and cost-effectiveness, while others suggest disease may be detected at an earlier stage, but, this does not manifest as improved survival. There is also the possibility that surveillance can do harm. Screening tests are not diagnostic tests and further investigations may be required leading to patient anxiety and potential injury, for example, bleeding from liver biopsy. Indeed, where diagnostic doubt persists treatments may be offered that may be unnecessary or that could provoke liver decompensation.8 9

In many countries worldwide, 6-monthly ultrasound surveillance (USS), with or without concurrent measurement of serum α fetoprotein (AFP), has become an accepted part of the management of patients with cirrhosis to identify cases of HCC at an early stage, although to date there has only been one randomised controlled trial exploring the value of ultrasound only screening for patients deemed to be at high risk of HCC. In that study surgical resection was the only curative treatment option.10 The results showed that patients in HCC surveillance did have HCC detected at an earlier stage and had a lower mortality rate than those not screened (mortality 83.2/100 000 vs 131.5/100 000, mortality rate ratio 0.63 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.98)). Since then, ablative techniques and liver transplantation have joined the armamentarium of potentially curative treatments. Several other studies support the observation that USS does result in detection of HCC, but have questioned its ability to identify it at an earlier stage.11–14 Despite the scarcity of well designed randomised controlled trials, international liver societies including the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD),15 the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL),1 the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver16 as well as the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG),17 have recommended 6-monthly interval liver US for groups at high risk of HCC. Moreover, the results of a recent large meta-analysis showed that surveillance is a beneficial strategy for patients at risk.18

Nevertheless, to our knowledge, routine USS programmes for patients with cirrhosis are not in place in many district general hospitals in the UK. The information technology necessary to ensure that liver US is performed, on an outpatient basis, at the designated time is often not available and is also likely to be performed at intervals longer than the recommended 6 months. The present study to determine the current practice and provision of USS for the early identification of HCC was carried out by a group of UK hepatologists, surgeons, radiologists, histopathologists, oncologists, gastroenterologists and nurses with a special interest in HCC and dedicated to improving the care of patients with HCC. There were two parts to the study: one was to survey the current practice and attitudes to USS HCC surveillance, and the second was to determine at what stage patients with newly diagnosed HCC were at the time of presentation to specialist hepatobiliary multidisciplinary team meetings.

Methods

The survey was generated through a series of questions that were reviewed and approved by the authors (table 1) and approved by the president of the British Association for the Study of the Liver and the chief executive of the BSG. The questions were then entered onto an online survey set up through survey monkey (Survey monkey, USA) and then posted for completion on the British Association for the Study of the Liver and BSG websites and the UK HCC email distribution list. The survey was accessible to all gastroenterologists through these websites and was targeted at consultant gastroenterologists and hepatologists involved in caring for patients with liver disease. It was requested that only one response be sent from each hospital/unit to prevent duplication of responses and to determine the policy from each hospital and not that of each clinician. The survey was carried out from 30 June 2014 to 31 December 2014.

Table 1.

List of questions posed in the national HCC UK survey of the current provision of USS for HCC detection

| Q1. | Are you aware of the guidance from AASLD and EASL with regards to HCC surveillance? |

| Q2. | Do you carry out liver USS for HCC in your hospital? |

| Q3. | What best describes the type of hospital you work in? |

| Q4. | How is HCC surveillance arranged in your hospital? |

| Q5. | Does your programme ensure that patients have an ultrasound on a 6-monthly basis? |

| Q6. | Do your patients get a written or verbal explanation as to why HCC surveillance is performed? |

| Q7. | Are ultrasound examinations on patients with cirrhosis reviewed by a dedicated radiographer/radiologist with expertise in HCC surveillance? |

| Q8. | What are the entry criteria for your HCC surveillance programme? (Select as many as you wish). |

| Q9. | Do you offer HCC surveillance for patients with autoimmune liver diseases, that is, autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis? |

| Q10. | On which criteria do you base a diagnosis of cirrhosis for the purpose of surveillance? (select as many as required) |

| Q11. | Do you believe that HCC surveillance is cost-effective? |

| Q12. | Do you believe that HCC surveillance improves patient outcomes? |

| Q13. | What barriers are there preventing the implementation of 6-monthly USS? |

| Q14. | What routinely happens to abnormal USS? |

| Q15. | Are there groups who should not have HCC surveillance? |

| Q16. | Does your hospital have a comprehensive liver database for all patients attending your hospital? |

| Q17. | Do you have a regular audit programme to assess detection rates for HCC from your surveillance programme? |

| Q18. | How many patients have been identified with HCC from your surveillance programme in the last 12 months? |

| Q19. | How many patients have been identified with HCC outside of a surveillance programme in your hospital in the last 12 months? |

| Q20. | Does your hospital have a dedicated hepatologist to see patients with cirrhosis? |

| Q21. | How would you describe yourself? |

| Q22. | In which part of Britain do you work? |

| Q23. | Do you have a lead consultant for hepatology in your hospital? |

| Q24. | How many consultants are involved in your hepatology service? |

AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; EASL, European Association for the Study of the Liver; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; USS, ultrasound surveillance.

The second part of the study was to evaluate the stage of HCC at first presentation to specialist multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings on hepatobiliary cancer. The data collected included gender, age, disease aetiology, size of largest tumour, number of tumour nodules (1, 2, 3, >3 or infiltrating tumour), Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage (BCLC stage), whether the patient was within or outside the Milan criteria, macrovascular invasion, extrahepatic disease and the AFP level at presentation. Tertiary liver cancer referral centres were identified from the HCC UK database and clinicians from these centres were approached to submit data. The participating centres were asked to provide either 2 months of information for the patients being presented at the MDT or the last 10–20 patients discussed (whichever was the larger). Individual patient data was not requested but a summary of the data from the respective institution was to be provided. The authors did not seek to assess the impact of surveillance or outcome determined by treatment modality offered in this study.

Statistical analysis

All values were expressed as median values with ranges. Results are shown with numbers and percentages. Given the absence of individual patient data, a range of data variables was provided. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test (with Yates’ method) and ORs were calculated with 95% CIs and p values, where a p value <0.05 (two-tailed) was deemed to be statistically significant. Analyses were conducted with SPSS V.18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

There are 209 clinical commissioning groups in the UK and 156 acute hospital trusts. There were 138 responses including 7 duplicate responses from transplant centres. Excluding the known duplicate responses there were 131 replies from 156 units (response rate 84%). Eighty (58.4%) respondents worked in district general hospitals, n=42 (31%) in tertiary units (performing all aspects of specialist liver care but excluding liver transplantation) and n=15 (11%) in liver transplant units (figure 1). There was representation from all parts of the UK. Of the 138 respondents to the survey, 51 (38.4%) described themselves as hepatologists and 55 (41.4%) as gastroenterologists with an interest in hepatology. Four (3.01%) were luminal gastroenterologists and 23 (17.3%) considered themselves to be general gastroenterologists. Nine (6.8%) were clinical nurse specialists. Replies came back from: Scotland 12 (9.16%), Northern Ireland 2 (1.5%), Wales 7 (5.3%), England North-East 19 (14.5%), England North-West 13 (9.9%), England West Midlands 17 (13%), England East Midlands 10 (8%), England South-East 12 (9.2%), London 15 (11.5%), England South 11 (8.4%) and England South-West 13 (9.92%). The number of consultants recorded as working within a hepatology service with no other consultant was 3 (2.3%) and with 1 consultant involved 23 (17.3%), 2–4 consultants 68 (51.1%), 5–9 consultants 36 (27.1%) and > 10 consultants 3 (2.26%).

Figure 1.

Workplace representation of study participants.

One hundred and thirty-two (96%) of respondents replied to the effect that they were aware of the guidance on HCC surveillance from AASLD and EASL and 134 (97.1%) stated that a USS programme was in place in their hospital. This was arranged on an ad hoc basis in 104 (76%) centres, by a specialist nurse in 29 (21%), and on an automated basis in 3 (2.2%) of cases. One respondent to this question stated no surveillance was done in their hospital (0.76%), although in answers to subsequent questions the number of centres stating surveillance was not performed at their institution did change. Eighty-four (62%) stated that the surveillance programme in place ensured repeat scans on a 6-monthly basis and 98 (71.5%) replied that patients were given a verbal or written explanation to outline why the 6-monthly US were being performed. The US were not often performed by radiographers or radiologists with expertise in HCC surveillance, that is, only 31 (22.6%), were performed by ultrasonographers with specialist knowledge of liver disease. Criteria for entry into a HCC surveillance programme as reported by the respondents were as follows: age >40 years (21, 15.3%), gender (6, 4.4%) and disease aetiology, that is, alcoholic liver disease, genetic haemochromatosis, CHB infection, CHC infection, NAFLD (24, 17.5%), all patients with cirrhosis (119, 86.9%), non-cirrhotic high-risk groups, for example, non-cirrhotic CHB with a family history of HCC, viral co-infection with chronic hepatitis delta or HIV and CHB or CHC (86, 62.8%) and patients fit for curative treatment (45, 32.9%). Three respondents to this question (2.19%) replied that their hospital had no surveillance programme, contradicting an earlier response to the number of centres not offering surveillance. Patients with cirrhosis caused by autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis would have been offered surveillance by 117 (86%) of those questioned.

Those questioned accepted the following methods as sufficient for a diagnosis of cirrhosis to lead to entry into a surveillance programme: histology (119, 88.2%), imaging (120, 89%), elastography including: Fibroscan, acoustic radiation frequency intensification (n=93, 69%), liver fibrosis, blood test algorithms, for example, enhanced liver fibrosis, FibroTest, AST-to-platelet ratio index, aspartate aminotransferease (AST)/alanine aminotransferase (ALT), King’s score (26, 19.3%), routine blood tests and clinical signs (91, 67.4%). Fifty (36.8%) felt that surveillance was cost-effective, while 72 (52.9%) felt that this was better determined by the clinical circumstances. This question was followed up with views on the impact of surveillance on patient outcomes. Eighty-two (60.1%), believed that outcomes were improved, whereas 49 (36%) thought that the benefits of surveillance were better determined by the clinical circumstances of the patient.

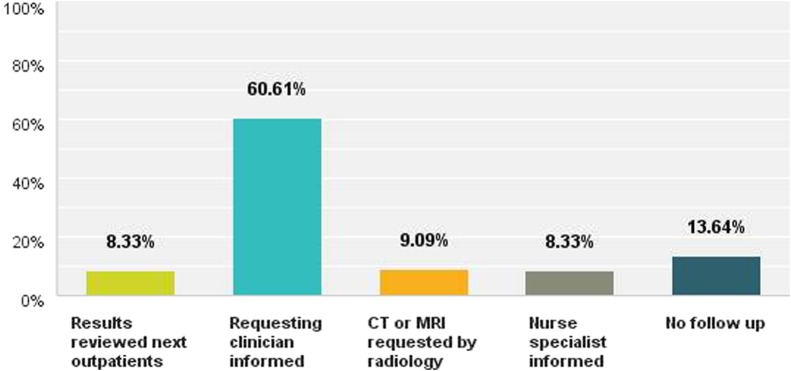

Barriers to the implementation of 6-monthly USS were cited as follows: difficulty accessing radiology services (45, 41.3%), cost (27, 24.8%), doubts over effectiveness (39, 35.8%), not considered a priority in their hospital (14, 12.8%). Other reasons cited included: logistical problems, lack of an accurate liver database, time to organise the system, ultrasound capacity, poor patient adherence, pressure from other sources, for example, new follow-up targets in outpatients, staff shortages and lack of radiology ‘buy in’. On the discovery of an abnormal US, this was dealt with in one of the following ways: results to be reviewed at next outpatient's appointment (11, 8.3%), clinician informed of abnormal result by telephone call, fax or email (80, 60.6%), radiologist organised follow-up CT or MRI scan (12, 9.1%), clinical nurse specialist informed of the result (11, 8.3%). Eighteen (13.6%) of respondents stated that their institution had no mechanism to inform the requesting clinician of an abnormal result (figure 2).

Figure 2.

How are clinicians informed of an abnormal ultrasound scan result?

In answer to the question ‘are there any groups of patients who should not be offered HCC surveillance?’ Twenty-three (22.3%) respondents thought patients with decompensated liver disease should be excluded, 25 (24.3%) thought patients >75 years should be excluded, 1 (0.97%) thought patients with cirrhosis <40 years should be excluded, 22 (21.36%) believed patients with alcoholic liver disease who continued to drink should be excluded and 64 (62.1%) believed that patients who were not candidates for curative treatment should not undergo HCC surveillance. Twenty-four (23.3%) cited other reasons to exclude patients from surveillance including: biological age, patient choice, performance status ≥2, persistent none-attenders, and where benefits of surveillance may be low, for example, women with autoimmune liver diseases.

One hundred and sixteen (86.6%) of the 134 responses indicated that the respective units did not have a comprehensive liver database for patients attending their department. One hundred and sixteen (86.6%) of the departments did not perform audit to assess the performance of their USS HCC surveillance programme and seven (5.3%) did not know if they did. In answer to the question of how many cases of HCC had been detected by centres within and out of the surveillance programme, the figures were 65 (48.5%) centres had detected <10 cases, n=25 (18.6%) 10–20 cases and n=9 (6.72%) >20 cases. Thirty-one (23.1%) of respondents were unaware of the number of cases picked up through surveillance. For cases detected outside surveillance, comparable figures in the centres were: (55, 41%) <10 cases; (24, 17.9%) 10–20 cases; (12, 8.9%) >20 cases; and (43, 32.1%) did not know the number of cases identified. In 66% of hospitals (n=87) a consultant hepatologist saw the patients with cirrhosis. Forty-five (34.1%) of responding hospitals did not have a dedicated hepatologist, with 97 (73%) of hospitals having a clinical lead for hepatology.

HCC stage at first presentation to a specialist hepatobiliary cancer MDT meeting

Thirteen centres submitted data on new cases of HCC presented at MDT meetings. Six of the centres were liver transplant units, six were tertiary referral centres and one was an oncology centre. In total, 352 cases were presented and discussed. The gender was known in 336 patients (265 men (79%)) and the median age of the cohort was 66 years (age range 43–83 years). The underlying liver disease leading to HCC was as follows: alcoholic liver disease 54 (22%), NAFLD 49 (20%), CHC infection 48 (19%), CHB infection 19 (8%), haemochromatosis 14 (6%), autoimmune hepatitis 3 (1%), primary biliary cirrhosis 4 (2%), mixed aetiology 18 (7%) and unknown 41 (16%). The median tumour diameter was 40 mm (range 9–200 mm) and the number of malignant nodules shown on US examination was known in 289 patients: 1 in 144 of patients (50%), 2 in 42 (15%), 3 in 30 (10%) and >3 in 49 (17%); infiltrating tumour was recorded in 24 (8%). The median AFP was 22 (range 2–27 905); as individual data was not available it was not possible to determine what proportion of patients had AFP levels <100, >100, >500 µg/l. The presence or absence of macrovascular invasion was known in 228 patients (absent 176 (77%), present 52 (23%)). Extrahepatic metastases were present in 14% of cases. The numbers of patients assessed as having disease potentially curable by radiological ablative technique, as defined by BCLC staging and Milan criteria, were: BCLC 0–A (curative) 128 (40%); BCLC B–D (non-curative) 195 (60%). The results are summarised in table 2. The number of patients within the Milan criteria for liver transplantation was 136 (47%), and those outside the criteria 53%. The authors compared stage of disease at MDT discussion between transplant and non-transplant centres. Transplant centres were less likely to have patients discussed when disease was at a radiologically curative stage, that is, BCLC 0–A, 72/201 (36%) as compared with 55/120 (46%) for non-transplant centres, although this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.08, χ2 3.16, OR 1.52 (0.96 to 2.4)).

Table 2.

Results of Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging at the time of diagnosis as reported in the survey responses

| BCLC stage n=323 | n (%) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 14 (4%) |

| A | 114 (35%) |

| B | 76 (24%) |

| C | 75 (23%) |

| D | 44 (14%) |

| Median tumour size | 40 mm |

| Malignant nodules n, 289 | |

| 1 | 144 (50) |

| 2 | 42 (15) |

| 3 | 30 (10) |

| >3 | 49 (17) |

| Infiltrating tumour | 24 (8) |

| Macrovascular invasion n, 228 | 52 (23%) |

| Extrahepatic metastases n, 230 | 32 (14%) |

Discussion

The responses obtained in the study represented different levels of hospitals involved in the care of liver patients, ranging from district general hospitals, to tertiary referral units and liver transplant centres. To our knowledge, this is the first time this data has been recorded across all of Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and England. There were seven duplicate responses from transplant centres. Excluding the known duplicate responses there were 131 replies from 156 units suggesting a response from 84% of hospitals. It was not possible to determine if there were multiple responses from other centres. Although the survey suggested that the majority of respondents were aware of the expert bodies’ guidance on USS for HCC and 97% carried out USS, only 62% of hospitals ensured that this was carried out on a regular 6-monthly basis. This is likely to be an overestimate. In the absence of good databases and regular audit the true interval time between scans is unknown. Although the majority of hospitals practice HCC surveillance, the programmes are poorly organised. Audited data from the Royal Liverpool Hospital, where an automated recall system is employed, suggested that the mean time between scans was 7 months (Dr Catriona Farrell, personal communication). Furthermore, clinicians were unaware of how their surveillance programme was performing. This is unsurprising given the absence of clinical data sets for cirrhosis and chronic liver disease and the absence of audit data to benchmark identified deficiencies in the service. For the purpose of this survey it was not possible to determine the proportion of cases detected from within a surveillance programme. Data collection systems are poor and differ between centres. At MDT meetings it is not routine practice to record if the case was recorded from within a surveillance programme or not. This would be useful to know and should form the basis of a future multicentre study or as a catalyst for more standardised, and ideally, centralised data collection. Despite patients receiving verbal or written information explaining the rationale behind surveillance, studies suggest a significant dropout rate from surveillance. This hints at the need for re-enforcement as to why it is so important to attend US.10 13 19 The survey showed that the majority of scans were not reviewed by a dedicated radiologist or ultrasonographer with expertise or training in this area. What constitutes an expert in liver ultrasound and surveillance? Are there a minimal number of scans that must be performed and how is that level of skill maintained and recognised? Given the user-dependent nature of US, this could impact adversely on patients. In a system where there is already a shortage of trained ultrasonographers, transfer of images for interpretation to a regional or large district centre could overcome these deficiencies, although interpretation of static images may be suboptimal.

There was some difference of opinion among the respondents as to who should be entered into a HCC surveillance programme. Eighty-seven per cent felt all patients with cirrhosis should be included, and 63% would include non-cirrhotic high-risk groups such as chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV)/non-cirrhotic disease. Inclusion of all patients with cirrhosis would allow patients with Childs-Pugh B and C disease. If within transplant criteria, such patients might be considered for liver transplantation. Current EASL guidelines only recommend screening in such patients if they are already on a liver transplant waiting list.1 Interestingly, only 1% of respondents felt that patients under 40 years should not have screening whereas 24.35% felt that patients over 75 years should be excluded. The guidance from AASLD suggests that hepatitis B carriers should start surveillance aged over 40 years in men and over 50 years in women.15 The mean age of presentation of HCC in a recent UK study was 67 years4 and it is well documented that older patients are more likely to develop HCC, and hence could benefit more from surveillance than their younger counterparts, especially in a population with a low prevalence of CHB infection. Ongoing alcohol consumption would preclude liver transplantation, but if non-transplant treatments that prolong life are applicable, should patients who continue to drink, be denied the chance of such treatments? Guidance on HCC surveillance focuses on patients at risk of HCC,15 but not necessarily on those who would not benefit from early detection of HCC. Clinicians might benefit from more didactic guidance to advise on ‘at risk’ patients who are unlikely to benefit from intervention including, for example, frailty, comorbidities, reduced life-expectancy, coexistent incurable malignancy, psychological issues and patient choice. A frank discussion with the patient before embarking on surveillance might prevent these problems. Approximately a third of patients thought that the process was cost-effective. A UK economic analysis demonstrated that screening was most effective in patients with CHB infection.20 But, if programmes are poorly organised and unregulated without regular audit, and patient groups most at risk of HCC remain unidentified (ie, the clinically silent patients with cirrhosis/high-risk HBV), is it a surprise that such a programme is not cost-effective? Better methods of surveillance and improved patient selection are needed.

Of concern, a third of hospitals did not have a dedicated hepatologist to see patients with cirrhosis. It is likely that in these hospitals, patients could be disadvantaged by not being referred for liver transplantation, locoregional treatments and clinical trials. Although there was a broad range of respondents in the survey, 80% of them described themselves as either hepatologists or gastroenterologists with an interest in hepatology. Moreover, in spite of the plea for only 1 response to be provided per institution, it is likely that there were some duplicate responses to our survey, because there are only seven transplant centres in the UK and there were 15 responses from such units. It is unlikely that this had a significant impact on the survey findings. The survey sought to gain responses for each institution and not opinion from individual clinicians. In such a survey multiple responses are difficult to prevent and the study provides useful UK data. The data from specialist MDTs demonstrated that only 40% of cases had radiologically curable disease. By the time comorbidities and frailty had been taken into account, the number of patients offered curative treatment may be lower than this (this may explain why some studies have shown earlier disease stage detection but no overall survival benefit). Over 350 cases were included and at such numbers, the data provided is likely to be representative of the picture nationally. There was no statistical difference between curable cases seen between transplant and non-transplant centres.

In summary, our survey has highlighted that the recommended guidance for HCC surveillance is known and practised by most hospitals but its implementation is poor. There is an absence of local and clinical databases that can identify patients with cirrhosis and see who is and is not involved in surveillance for patients with cirrhosis. This lack of infrastructure and information technology support means clinicians have no idea how their systems are performing. Nationally, outcomes for patients with HCC are poor and the majority of patients have radiologically non-curative disease at presentation. The aim of the UK Government has been to improve cancer survival by earlier diagnosis and HCC screening should be included in this strategy, that is, a readily available test, in a defined population with proven treatments.21 Given the rising burden of liver disease a nationally agreed strategy for HCC surveillance, implementation, as well as audit of findings is urgently required.

Key messages.

Six-monthly liver ultrasound is recommended for patients at increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.

This study shows that the organisation of HCC surveillance is poor in the UK.

Reporting mechanisms for abnormal ultrasound scans were not in place in 22% of centres.

There is a lack of standardised data collection between centres, poor IT systems and a virtual absence of audit to monitor the effectiveness of surveillance.

Sixty per cent (60%) of patients presenting to specialist multi-disciplinary team meetings have radiologically incurable disease

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the questions and provided a critique and suggestions for the manuscript. In addition authors provided local information used to describe stage of disease at presentation to specialist regional multidisciplinary teams. The manuscript was written predominantly by TJSC and RW with comments and suggestions from the other authors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The survey has all the data available on a password protected document kept by the company survey monkey, for the stage of HCC disease at presentation. Contributors provided anonymised summary data for their patients. This is stored on a password protected hospital laptop which is kept securely.

References

- 1.European Association For The Study Of The Liver; European Organisation For Research and Treatment of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:908–43. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2012;142:1264–73.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Njei B, Rotman Y, Ditah I, et al. Emerging trends in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence and mortality. Hepatology 2015;61:191–9. doi:10.1002/hep.27388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dyson J, Jaques B, Chattopadyhay D, et al. Hepatocellular cancer: the impact of obesity, type 2 diabetes and a multidisciplinary team. J Hepatol 2014;60:110–17. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2013.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Llovet JM, Bustamante J, Castells A, et al. Natural history of untreated nonsurgical hepatocellular carcinoma: rationale for the design and evaluation of therapeutic trials. Hepatology 1999;29:62–7. doi:10.1002/hep.510290145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1118–27. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1001683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Padhya KT, Marrero JA, Singal AG. Recent advances in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2013;29:285–92. doi:10.1097/MOG.0b013e32835ff1cf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lederle FA, Pocha C. Screening for liver cancer: the rush to judgment. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:387–9. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-156-5-201203060-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kansagara D, Papak J, Pasha AS, et al. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic liver disease: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:261–9. doi:10.7326/M14-0558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang BH, Yang BH, Tang ZY. Randomized controlled trial of screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2004;130:417–22. doi:10.1007/s00432-004-0552-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sangiovanni A, Del Ninno E, Fasani P, et al. Increased survival of cirrhotic patients with a hepatocellular carcinoma detected during surveillance. Gastroenterology 2004;126:1005–14. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2003.12.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trevisani F, Santi V, Gramenzi A, et al. Surveillance for early diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: is it effective in intermediate/advanced cirrhosis? Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:2448–57; quiz 58 doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01395.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santi V, Trevisani F, Gramenzi A, et al. Semiannual surveillance is superior to annual surveillance for the detection of early hepatocellular carcinoma and patient survival. J Hepatol 2010;53:291–7. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2010.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singal A, Volk ML, Waljee A, et al. Meta-analysis: surveillance with ultrasound for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;30:37–47. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04014.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011;53:1020–2. doi:10.1002/hep.24199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Omata M, Lesmana LA, Tateishi R, et al. Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver consensus recommendations on hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int 2010;4:439–74. doi:10.1007/s12072-010-9165-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryder SD. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in adults. Gut 2003;52(Suppl 3):iii1–8. doi:10.1136/gut.52.suppl_3.iii1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singal AG, Pillai A, Tiro J. Early detection, curative treatment, and survival rates for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001624 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Serag HB, Kramer JR, Chen GJ, et al. Effectiveness of AFP and ultrasound tests on hepatocellular carcinoma mortality in HCV-infected patients in the USA. Gut 2011;60:992–7. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.230508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson Coon J, Rogers G, Hewson P, et al. Surveillance of cirrhosis for hepatocellular carcinoma: a cost-utility analysis. Br J Cancer 2008;98:1166–75. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cancer Reform Strategy. 2007. http://www.dh.gov.uk