Abstract

Background and aims

The emphasis for healthcare clinicians to provide adequate disease-related education is increasing. Yet little is known about the effect of providing disease-related education within inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Previous studies have demonstrated increased levels of knowledge and satisfaction, but failed to capture any positive effects on the psychosocial elements of living with IBD. The aim of this qualitative study was to evaluate the impact of providing a group patient education programme on the psychosocial elements of living with IBD.

Methods

The data were obtained through eight semistructured qualitative interviews. Participants were recruited at the education programme using purposive sampling. All the interviews were digital recorded and transcribed. Thematic analysis was used by two independent researchers to analyse the transcripts and agreed emerging themes.

Results

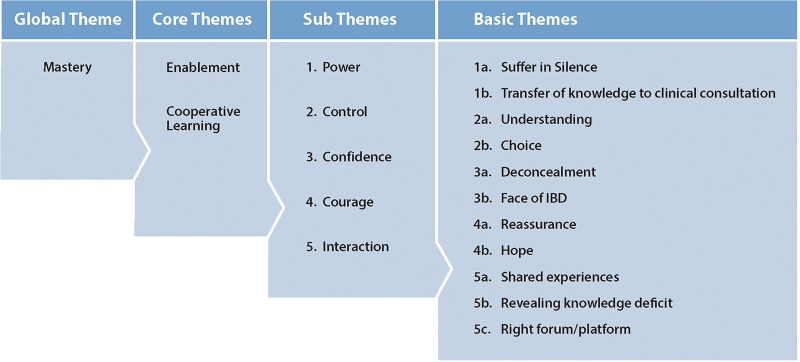

A global theme of ‘mastery’ was evident within the transcripts. This was underpinned with two core themes of enablement and cooperative learning. The education programme ‘enabled’ the participants in a variety of ways: increased confidence, control, courage and power over their disease. An unexpected core theme of cooperative learning was also identified, with participants describing the overwhelming benefit of interaction with other people who also had IBD.

Conclusions

This is the first qualitative study to report on the effects of providing a group patient education within IBD. The results identify new and interesting psychosocial elements that existing quantitative studies have failed to identify.

Keywords: IBD

Introduction

There is an abundance of literature, guidelines and standards advocating the importance of providing high-quality patient education within chronic diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).1–4 Traditionally, healthcare professionals have delivered patient education during routine IBD outpatient appointments. Although it is acknowledged that patients with IBD express a desire for more education, they report inadequateness of disease-related education during their routine outpatient appointments.5–8 These are the factors that acted as a catalyst to the development and implementation of a pilot group education programme within the northwest region of the UK. Yet, little is known about the effects of providing disease-related education within IBD.9 There is a paucity of data to support the clinical effectiveness and economic value of providing group patient education within IBD. Although previous studies have demonstrated both a greater level of disease knowledge and higher level of patient satisfaction with knowledge, the lack of positive effects on the psychosocial elements of having IBD remained unclear. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of the group education programme on the psychosocial elements of living with IBD.

Methods

The patient education programme was designed and implemented by a group of 10 IBD nurses from eight different hospital trusts in the northwest region of the UK. A preliminary questionnaire of 128 patients was performed to understand the educational needs and preferences of patients with IBD, which included topics, venues and timings of the sessions. The questionnaire identified 10 top topics that patients wanted to understand further (see box 1). The sessions took place on rotating basis on a Thursday evening, or Saturday or Sunday morning as highlighted by patient's preference. Five of the seven sessions took place in a regional hotel on good motorway connections because patients preferred free parking and the informal environment. The other two sessions took place in two different hospital postgraduate centres due to lack of availability at the hotel. The patient education programme ran once a month over a 9-month period with expectation of July and August. Each of the topics highlighted by the patient questionnaire was repeated twice over this period, with two topics on the evening programme (2 h in total) and three topics on the weekend morning (two and half hours in total). A 30 min general question-and-answer session concluded every session. Programme booklets were posted to patients where existing databases were available. The education programme was also advertised in clinic areas with roll out banners and Crohn's and Colitis UK (CCUK) website. A dedicated website was developed so patients could gain further information on the programme and register for the sessions of their choice (http://www.ibdpatiente ducationprogramme.co.uk). Patients could also register over the telephone; both of these were kindly coordinated by CCUK. A total of 70 patients attended some or all sessions, patients could pick to register for any of the sessions, it was not compulsory to attend the whole educational programme. The speakers were all consultant gastroenterologists or IBD nurse specialists who provided their time on volunteer basis, a dietician and psychologist. To evaluate this pilot, a qualitative study design was used. Qualitative research has become increasingly popular in health service research because it explains and explores context, patients’ behaviour, experiences, views and beliefs in order to better understand the healthcare system.10

Box 1. Ten top topics identified by patient.

Topics—not in rank order

What is inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)?

Drug treatments in IBD

Future new treatments in IBD

Pregnancy and fertility in IBD

How to cope with IBD?

The role of diet in IBD

Investigations in IBD

How to self-manage IBD

The risk of cancer in IBD

Alternative treatments

Sampling and data collection

The sample was recruited using purposive sampling to ensure good range of gender, age, social background, disease type and duration. The participants in this study are homogeneous of the population under consideration, and the researchers identified the participants who had attended the most educational sessions to provide richness to the data. Eight patients were recruited from the 70 patients, who attended the education programme. The following inclusion criteria were applied: patients with existing diagnosis of ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn's disease (CD), 18 years or older with the ability to give written consent and must have attended the education programme. The participants’ demographics and characteristics are shown in table 1. The interviews were semistructured using a topic guide seen in box 2. All the interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. The mean duration of the interviews was 42 min (range, 30–60 min).

Table 1.

Participant demographics and characteristics

| Participant no. | Diagnosis | Age | Disease duration (years) | Gender | Sessions attended (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | UC | 30 | 2 | F | 4 |

| 2 | UC | 35 | 1 | F | 3 |

| 3 | CD | 55 | 9 | F | 2 |

| 4 | UC | 40 | 7 | M | 3 |

| 5 | CD | 48 | 17 | F | 3 |

| 6 | UC | 63 | 4 | M | 1 |

| 7 | UC | 39 | 5 | M | 3 |

| 8 | CD | 29 | 6 | M | 3 |

Box 2. Topic guide.

Questions

Background and personal circumstances

Can you tell me a little about yourself and how your condition affects you and your life?

Feelings and perceptions prior to attending the education programme

Can you tell me how you found out about the education programme and why you decided to attend the education programme?

Feelings and perceptions while at the patient education programme

Can you tell me about your experience on the day of attending the patient education programme?

Feelings and perceptions since the patient education programme

Can you tell me the difference the patient educational programme has made to living with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)?

Probing Questions

What does this mean to you?

How were you feeling at the time?

Tell me more about that?

Data analysis

The transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis. Transcripts were read and re-read in order to gain a sense of understanding and feeling of the participants.11 The data was then reduced into ‘chuck themes’, which also involved searching for connections across emergent themes.12 Potent and consistent themes through the transcriptions were then identified and agreed while ensuring a strong interpretive focus.11 Thematic analysis was achieved by colour coding manually, no computer assisted qualitative data analysis software packages, such as NVivo, were used.

Rigour

Rigour is best described as the means by which integrity and competence are demonstrated within a study.12 The following steps were taken. Transcripts were analysed separately by two researchers and met to compare and agree the identified themes. The results of the study are discussed in the context of the current published literature. Reflexivity was also considered throughout this study using field notes.13

Ethics

This study received a favourable opinion from the Proportionate Review Ethics Subcommittee on the 17 July 2013 (reference 13/YH/0248).

Results

An overall theme of ‘mastery’ was identified from two core themes of ‘enablement’ and ‘cooperative learning’. Within these two core themes, a number of sub themes and basic themes emerged from the transcripts, see figure 1. Although the results are presented under individual themes, they all interlink with each other.

Figure 1.

Qualitative themes. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Enablement—power

Participants described a significant amount of ‘suffering in silence’ while living with their IBD. They identified a high level of symptoms during a flare-up and uncertainty of when and how to access specialist advice. Lack of general practitioners’ (GPs) knowledge of IBD was identified as exacerbating this issue. The patient education programme enabled the participants to access specialist services more, resulting in an increased usage as opposed to reducing use of healthcare resources.

I felt like next time don't be so stupid, just go straight back and tell them you are not feeling too great …. my GP doesn't really know anything about it. I actually can turn to someone straight away with my problems … (P01)

The patient education programme also enabled participants to seek out more information and transfer the information from the education programme into their traditional routine outpatient appointments.

I google stuff now which I wasn't a big googler before. I have to say that has continued in the individual consultations.. (PO3)

Enablement—control

The findings demonstrated that the participants attended the patient education programme because they were at certain time point within their disease. They wanted to have more ‘control’ by ‘understanding’ their disease in more detail. They believed knowledge would be the key to this and reported an increased perception of knowledge following the patient education programme.

I didn't understand what was going on …. I just needed to find out more … knowing why it had come back… (PO3)

In addition to ‘understanding’ the disease, participants wanted to know what ‘choices’ of treatment that were available to them. This was highlighted as not always being fully explored in a routine outpatient appointment.

I didn't realise or know what other paths were available to me … making you more aware of paths that are available to you which helps you with the condition and the consequences of those paths… (PO8).

Enablement—confidence

There was variability within the transcripts of embarrassment of living with IBD. Some participants were able to be open about their diagnosis to family and friends from the outset, while for some participants, the education programme was the turning point that led to a basic theme of ‘deconcealment’.

it almost felt actually why have I found it so difficult to deal with this. (PO5)

I found it embarrassing at first. I didn't want to open up and talk about it. That has changed now. (PO7)

The outcome of ‘deconcealment’ following the education programme was an unintended consequence. In contrast to this, two participants discussed the desire to know what other patients with IBD looked like and how this gave them ‘confidence’. This emerged as an unexpected basic theme of ‘the face of IBD’.

That is why I wanted to go to the meeting, because I'm interested to know what other people look like who have got colitis. It was very interesting to see what kind of people had it. (PO2)

Enablement—courage

The participants in this study all report a sense of ‘reassurance’ and ‘hope’ after attending the education programme. There was strong evidence that the participants had less concerns and anxieties compared with the outset of the programme. Issues of pregnancy and fertility were also especially relevant to some of the young female participants.

level of reassurance… (PO5)

it can take some of the heaviness away… (PO6)

but my outlook is better now …. even my mum and partner want to know how it will affect my future and having another baby (PO1)

Co-operative learning—interaction

A further sub theme of ‘cooperative learning’ also emerged from the data. The participants in this study all described the value of ‘interaction’, ‘shared experiences’ and the ‘the right forum/platform’. Participants identified the usefulness of listening to other patient's questions as they may have not necessarily thought or considered them previously. This brought about a basic theme of ‘revealing knowledge deficit’.

I liked listening to other people's question because sometimes they will say something that you haven't thought about. I think it was very important information (PO2)

The participants identified IBD as a socially isolating disease. Interactions with other people with a similar condition proved to be a positive experience, something that most participants had not experienced before.

It is just sharing your story with others (PO5)

The education programme also offered participants a unique learning concept of ‘the right forum/platform’, a very different concept to the traditional routine outpatient appointment.

it's a step past the actually appointment and a bonus really (PO6)

my brain freezes up under the pressure of being in a consultation, I go in with a million and one things to say but the route of your discussion takes you into different path, but being in an environment of talking freely… I think sometimes things can sink in a little bit better (PO7)

Discussion

The data from the eight semistructured interviews demonstrate how the group education programme enabled participants to live with their IBD more freely and effectively from a psychosocial perspective. This is the first qualitative study to report the effects of providing group education within IBD. Correspondingly, also the first study to delineate a positive effect that group education has on the psychosocial elements of living with IBD. This is not surprising given the established differences between quantitative and qualitative studies, with the latter being able to capture the participant's insight and essence of living with IBD.14 15 Previous studies have failed to capture any positive psychosocial effects of providing a patient education programme with quality of life scores.8 7 Demonstrating that quality of life is difficult to measure, and quality of life scores may be ineffective in capturing the psychosocial effects of providing group education within IBD.

Qualitative studies of living with IBD have all reported that maintaining a degree of ‘control’ is important to patients with IBD. This may not necessarily be disease severity or symptoms, but ‘personal control’.16 17 The educational programme enabled patients to seek specialist advice when needed, whereas previously this was seen as a frustration both in access to specialist care and lack of GP knowledge; the areas highlighted by the IMPACT survey18 and other studies.19 The participants also reported an increased sense of ‘control’ following the education programme, confirming the suggestion that a greater confidence in one's disease knowledge may have some positive effect on the psychological well being of patients with IBD.17

Patients with IBD also report increased concerns about cancer, fertility, treatments and the need for surgery. The evidence is inconclusive if providing disease-related knowledge increases anxiety.20 21 It was evident from this study that participants had less anxieties and concerns following the group education programme.

An increased sense of ‘confidence’ through the recognition of the ‘face of IBD’ and ‘deconcealment’ of disease was also reported by the participants. The participants that concealed their disease within this study described how the education programme gave them the ‘confidence’ to allow ‘deconcealment’. In turn, they were able to discuss their illness more openly. A recent meta-synthesis on the health and social care needs of people living with IBD discovered how individuals living with IBD made peace with their illness while neither submitting defeat to it either.21 The desire to recognise other patient with IBD has already been published within previous research.22 This is where a number of physical, medical and psychosocial comparisons are made by patients in order to continually reassess and monitor their current well-being and progression of their illness.22 This is the first study to demonstrate that providing disease-related group may increase patients’ confidence and allow them to openly accept their disease.

IBD is described by patients as a ‘lonely disease’ and ‘socially isolating’ due to invisibility.23 24 The findings in this study concur with previous evidence. The participants valued the shared empathy from other patients and exchanged information with each other on everyday practicalities of living with IBD. This is similar to the findings of previous research focus groups.22 The question and answer session was also well received by the participants. They valued the degree and depth of the questions asked by other patients. This developed new participant knowledge in addition to the information given to them by the speakers. Some participants reported that they used this new knowledge within their individual consultations, and this is the first study demonstrate this.

Limitations and recommendations

The sample size within this study is small and not generalisable. However, the strength of qualitative results is its transferability to other populations. Patients did not attend the full programme but the programme was not designed to ensure this. Patients self-selected which sessions they felt most appropriate to them, for example, more women than men attended the fertility and pregnancy session. This evaluation is in patients who attended the same sessions but not all. This study only interviewed patients who attended the programme, these patients may have had more of a desire for knowledge and therefore benefitted. A recommendation would be to interview the patients who made the decision not to attend the educational programme.

Conclusion

This is the first qualitative study to report on the effects of providing disease-related education within IBD. Correspondingly also the first study to demonstrate a positive impact of providing this type of group education on the psychosocial aspects of living with IBD. It identifies new themes previously unreported and demonstrates that providing group education addresses the gap in knowledge provision, which is unable to be achieved through the traditional outpatient consultation. The implementation of a group education programme offers patients not just knowledge but interaction with others and a supportive learning environment, which has the potential to positively impact on IBD care.

Key messages.

What is already known on this topic?

Previous quantitative studies within this area have demonstrated a positive effect on the level of patient knowledge but unable to explain why there has been no impact on quality of life scores.

What this study adds?

this is the first qualitative study within this area and demonstrates that providing disease related education has positive impact on the psychosocial effects of living with IBD.

How it might impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

Providing disease related education doesn't only provide knowledge but the opportunity to interact with others, having a positive impact on IBD patient care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the speakers who have provided their time to the education programme. We would also like to acknowledge the steering committee of the original education programme, Veronica Hall, Suzanne Tattersall, Tina Law, Lynn Gray, Belle Gregg, Andrew Kneebone, Catherine Stansfield and Anne Hurst. We also like to acknowledge Crohn's and Colitis UK for their support and efforts during planning and implementation of the education programme.

Footnotes

Contributors: This study forms part of the MSc in Advanced Clinical Practice. MS and VR designed the qualitative study and developed the topic guide for the interviews. MS conducted the semistructured interviews. Analysis of the data was conducted by MS and KK. The manuscript was drafted by MS, KK and VR and contributed significantly to the draft of the manuscript and revised for intellectual content. All three authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The patient education programme was funded by Shire UK, but no funding was used towards this research study.

Competing interests: We confirm that the article, related data, figures and tables have not been previously published and are not under consideration elsewhere. MS has acted as a speaker or advisor for Abbott/AbbVie UK, MSD, Dr Falk Pharma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Vifor Pharma and Warner Chilcott. KK has acted as a speaker or advisor for Abbott/AbbVie UK, Dr Falk Pharma, MSD, Shire Pharmaceuticals and Warner Chilcott.

Ethics approval: Proportionate Review Ethics Subcommittee on the 17th July 2013 (reference 13/YH/0248).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Eaden J, Abrams K, Mayberry J. The Crohn's and Colitis knowledge score: a test for measuring patient knowledge in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:3560–6. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01536.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health. Structured patient education in Diabetes. 2005. http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassests/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset//dh_4113197.pdf (accessed 14 Sep 2015).

- 3.IBD Standards Group. Quality Care; Service Standards for the healthcare of people who have Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). 2013. Update. http://www.ibdstandards.org.uk/ (accessed 14th Sep 2015).

- 4.National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE). Crohn's disease: management in adults, children and young people. 2012. http://www.guidance.nice.org.uk/CG152 (accessed 14 Sep 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butcher R, Law T, Prudham R, et al. Patient knowledge in inflammatory bowel disease: CCKNOW, how much do they know? Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17:E131–132. doi:10.1002/ibd.21810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernstein K, Promislow S, Carr R, et al. Information needs and preferences of recently diagnosed patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17:590–8. doi:10.1002/ibd.21363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waters B, Jensen L, Fedorak R. Effects of formal education for patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a randomized controlled trial. Can J Gastroenterol 2005;19:235–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borgaonkar M, Townson G, Donnelly M, et al. providing disease-related information worsens health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2002;8:264–9. doi:10.1097/00054725-200207000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moradkhani A, Kerwin L, Dudley-Brown S, et al. Disease specific knowledge, coping and adherence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 2011;56:2972–7. doi:10.1007/s10620-011-1714-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finlay L. ‘Outing the researcher’: the provenance, process and practice of reflexivity. Qual Health Res 2002;21:531–45. doi:10.1177/104973202129120052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith J, Flowers P, Larkin M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. London, UK: Sage, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tobin G, Begley C. Methodological rigour within a qualitative framework. J Adv Nurs 2004;48:388–96. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03207.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London, UK: Sage, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pope C, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 2000;320:50–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venderheyden L, Verhoef M, Hilsden R. Qualitative research in inflammatory bowel disease: dispelling the myths of an unknown entity. Dig Liver Dis 2006;38:60–3. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2005.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salmon P, Hall G. Patient empowerment and control: a psychological discourse in the service of medicine. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:1969–80. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00063-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper J, Collier J, James V, et al. Beliefs about personal control and self-management in 30–40 year olds living with inflammatory bowel disease: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 2010;47:1500–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghosh S, Mitchell R. Impact of inflammatory bowel disease on quality of life: results of the European Federation of Crohn's and Ulcerative Colitis Associations (EFCCA) patient survey. J Crohns Colitis 2007;1:10–20. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2007.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kemp K, Griffiths J, Campbell S, et al. An exploration of the follow-up up needs of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2012;7:386–95. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selinger C, Lal S, Eaden J, et al. Better disease specific patient knowledge is associated with greater anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:e214–18. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2012.09.014 (accessed 14 Sep 2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsson K, Sundberg Hjelm M, Karlbom U, et al. A group-based patient education programme for high-anxiety patients with Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 2003;38:763–9. doi:10.1080/00365520310003309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kemp K, Griffiths J, Lovell K. Understanding the health and social needs of people living with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:6240–9. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i43.6240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall N, Rubin GP, Dougall A, et al. The fight for ‘health-related normality’: a qualitative study of experiences of individuals living with established inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). J Health Psychol 2005;10:443–5. doi:10.1177/1359105305051433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dudley-Brown S. Living with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Nurs 1996;19:60–4. doi:10.1097/00001610-199603000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]