Abstract

Background

5-Amino salicylate (5-ASA) medications may rarely be associated with a significant decline in renal function and interstitial nephritis. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines advise regular renal function monitoring for patients taking these drugs.

Aim

To assess whether gastroenterologists in Kent were following best practice guidelines regarding the monitoring of their patients on 5-ASA therapy.

Methods

Using longitudinal community and regional pathology databases for the Kent population, our renal unit regularly screens a total population of 300 000 for evidence of renal disease. The data extracted are analysed using an automated computerised system to identify patients requiring intervention for kidney disease. All patients taking 5-ASA medication were identified from a population of 300 000. The pathology database was studied to identify the patients on 5-ASA treatment and whether they had had renal function tests.

Results

800 adult patients were identified taking 5-ASA therapy. 612 patients received 5-ASAs for 3 months or more, and these were included in the final analysis. 293 patients had no renal function checks while on treatment. 79 patients had renal function tests less than once every 4 years and 36 patients once every 2–4 years. 204 patients had renal function measurements in 50% or more of years of treatment, of whom 116 were checked every year. Some patients were started on treatment with abnormal results at baseline and some with identified kidney disease continued on their 5-ASAs.

Conclusions

The majority of patients receiving 5-ASA compounds do not have regular renal function monitoring. Clinicians are failing to follow best practice guidelines.

Keywords: 5-Aminosalicylic Acid (5-ASA), Drug Toxicity, IBD Clinical

Introduction

Since Azad-Khan discovered the 5-amino-salicylate (5-ASA) moiety of sulphasalazine was providing the beneficial treatment effect in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD),1 5-ASA therapy has become a cornerstone treatment in their management. The medications are used in both the acute phase of IBD and in maintaining remission.

The safety profile of 5-ASAs is generally regarded as favourable. Rarely, these drugs have been associated with nephrotoxicity with resultant chronic kidney disease and it is important that clinicians identify this rare complication early.2–12 Muller et al in 2005 suggested an incidence of nephrotoxicity in patients with IBD taking 5-ASAs to be about one per 4000 patients/year.2 A systematic review of the available case reports and large studies conducted in 2007 suggested that the incidence of nephrotoxicity in patients with IBD taking 5-ASA should be less than 0.5%.3 If nephrotoxicity were to develop in these patients, the morbidity can be severe. A review of the literature analysing 23 cases of biopsy-proven 5-ASA-related nephrotoxicity demonstrated that 61% would have residual renal insufficiency and 13% progressed to end-stage renal failure.4

The timing of the discovery of 5-ASA nephrotoxicity and subsequent drug discontinuation can determine the likelihood of renal function returning to normal or contributing to long-term renal impairment. World et al5 found that in cases with renal impairment diagnosed within 10 months of starting treatment, drug cessation led to regression in 85% of cases, but where the diagnosis was made after 18 months of 5-ASA treatment, recovery of renal function was only seen in 33% of cases.

The predominant type of renal injury caused by 5-ASAs is a chronic interstitial nephritis,5 although other types of renal injury such as minimal change nephropathy 9 24 25 have occasionally been reported. Interstitial nephritis due to 5-ASAs can be a slow, severe, chronic disease with no specific symptoms,3 which makes it difficult to detect unless monitoring is undertaken or renal impairment is sufficiently advanced to cause symptoms. This further underscores the importance of monitoring these patients regularly.

Several studies have suggested that the relationship of 5-ASA nephrotoxicity and renal impairment is an idiosyncratic one as opposed to a dose-dependent one.3 6 7 However, a recent Canadian study of 171 patients with IBD demonstrated a dose-dependent and duration-dependent decline in renal function for patients using 5-ASAs.8 An older study of 223 patients with IBD also suggested there may be a dose-dependent relationship.9 Therefore, it would seem prudent to ensure that those patients taking higher doses of 5-ASA medications, that is, over 3 g/d8, should be monitored with extra vigilance.

The onset of renal impairment in IBD patients on 5-ASAs can vary widely, with reports highlighting its onset within 29 days and beyond 5 years.2 10 11 Several studies have confirmed that 50% of cases present within 1 year of treatment initiation.3 12 Patients with pre-existing renal dysfunction may be more likely to suffer 5-ASA nephrotoxicity8 than those with normal renal function.

These findings highlight the rationale for close renal function monitoring of patients with IBD on 5-ASA therapy5 13 14 as potential for nephrotoxicity exists with all 5-ASA preparations.15–21 The Medicines Healthcare Regulatory Authority (MHRA) recommended a monitoring regimen in 2011 consisting of serum creatinine levels measured prior to treatment, every 3 months for the first year, then 6 monthly for the next 4 years and annually thereafter.13 The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) also in 2011 advised ‘regular’ renal function monitoring for patients taking these drugs. In this context, regular is likely to mean annual.14

The aim of our study was to assess whether clinicians in Kent were monitoring their patients taking 5-ASA therapies, how frequently and whether previously published guidelines were being followed.

Methods

Data were extracted from the System for Early Identification of Kidney Disease (SEIK) database, which uses MIQUEST, a standardised extraction syntax developed by Connecting for Health. This was created by the Renal Department at Kent and Canterbury hospital to allow monitoring of the renal function of patients added to the database. The population of East Kent is approximately 742 460,22 of which 300 000 are screened regularly for evidence of renal disease, the data for which are available on the SEIK.

General practices are recruited onto the database, and thereafter, the SEIK can gain data from the general practice software systems. Comprehensive information on 52 different variables can be collected. This includes data regarding age, sex, comorbidities and prescription history. Data are extracted using NHS number, gender and date of birth as the only identifiers. Data are subsequently anonymised prior to use in research.

The SEIK monitors patients for progressive kidney disease, extracting data from primary care IT systems approximately monthly. Any individual who has had a serum creatinine estimation since the last extraction is included in the database. Once included, all historical data are extracted, providing a comprehensive dataset. For this study, laboratory data from secondary care were linked using NHS number so that all results from primary and secondary care were included.

Only patients who were both on 5-ASA therapy and who had had a serum creatinine estimation at least once by primary care since 2006 were included (93.1% of cases). The remainder were of historical cases from 2003. Based on the last prescription data of 5-ASAs, 69% were from 2013.

The database allowed us to identify patients on 5-ASA therapy, their age, sex and whether renal function monitoring was performed with respect to initiation of 5-ASA therapy. We used the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) to determine renal function and this in turn was calculated using the four-variable modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD) formula.26

Results

Of the 300 000 patients on the SEIK system, 800 adult patients were identified as taking 5-ASA therapy (M 341, F 459). The median duration of therapy was 1.5 years with a range of 1–24 years. The mean (± SD) age of patients on 5-ASA therapy was 52.7±16.2 years (range 18.2–94.4 years).

The mean estimated eGFR on commencing 5-ASA therapy was 82 mL/min (range 28 to >90). Patients with an eGFR <60 were regarded as having chronic kidney disease (stage 3–5).

In total, 612 patients received 5-ASAs for 3 months or more (median 3.2 years, range 0.25–24) and these were included in the final analysis.

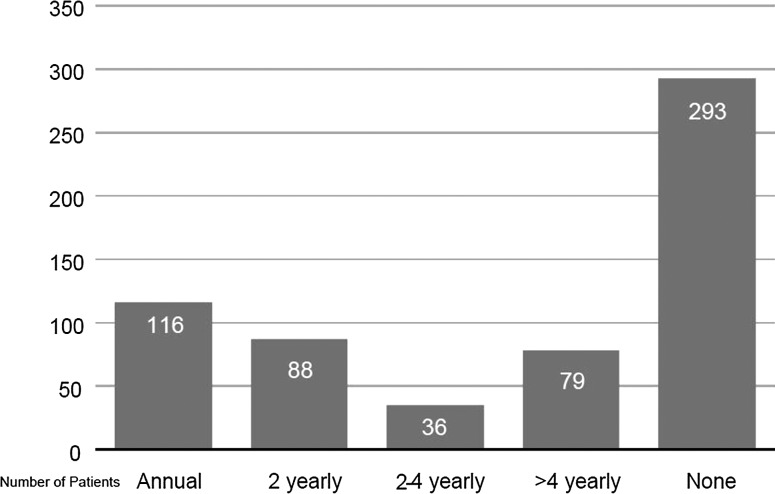

Also, 293 (48%) patients had no renal function checks while on treatment (age and eGFR profile prior to treatment was the same as those having checks). Sevent-nine (12%) patients had renal function tests less than once every 4 years and 36 patients once every 2–4 years. A total of 204 patients had renal function measurements in 50% or more of years of treatment, of whom 116 were checked every year (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Frequency of renal function monitoring for patients.

Seventy-two patients with a baseline eGFR <60 mL/min/year were treated with 5-ASA for 3 months or more. Eight patients did not have their renal function rechecked. The eGFR fell in 24 patients and in 8 by greater than 2 mL/min/year.

Discussion

Our database of over 300 000 patients identified 800 taking 5-ASA medications. It recorded all blood test results initiated in both primary and secondary care. It confirmed that 48% (293) did not have their renal function measured while on treatment and that the majority of the remainder were tested less frequently than every year. This failure of monitoring is hard to justify given the BSG14 and MHRA13 guidelines. Importantly, the lack of monitoring may increase the risk of missing or delaying the diagnosis of renal impairment (and other side effects), although one that is rare but with considerable morbidity.

Only 19% (116) of patients had annual tests of renal function. The published literature confirms that 50% of patients who develop 5-ASA nephrotoxicity do so in the first year3 12 and that early identification may reduce/lessen the burden of chronic kidney disease if noticed early and the drug is withdrawn.5 Our results suggest that greater awareness of drug side effects and the role of monitoring is required from clinicians.

Some patients were commenced on 5-ASA treatment when baseline renal function identified chronic kidney disease; 72 had an eGFR of <60 mL/min at the start of therapy, a cohort requiring extra vigilance given their renal function was already compromised.8 We found no evidence they were monitored more carefully. Eight of this group did not have renal function rechecked at all after initiating 5-ASA medications. Of the remainder, the eGFR fell in 24 (33%) patients, a finding that would support the findings of Patel et al8 that those with pre-existing renal disease are more likely to develop 5-ASA nephrotoxicity.

Patients taking 5-ASA medications were determined using GP practice repeat prescriptions. We have assumed that these patients were taking their medications regularly, although this may not necessarily be the case. They may have been called for blood tests and not attended, hence a monitoring failure due to patient compliance and not medical oversight. Our data could not discriminate the reasons for the testing of renal function. Blood checks may have been performed for entirely different reasons than monitoring for complications of 5-ASA therapy.

Our results are very different from those of a French questionnaire-based study where 90% of the gastroenterologists surveyed stated they regularly checked renal function in their patients with IBD on 5-ASA therapy.27 This discrepancy is likely to be explained by the fact that although described as a nationwide study there were only 249 respondents, a small percentage of the total number of French gastroenterologists. The practice of non-responders may have been very different. The current study looked specifically at whether blood test monitoring was performed and therefore was not subject to perception bias.

One possible explanation for patients not being monitored regularly is that primary and secondary care clinicians may be unaware of the risk and potential severity of 5-ASA nephrotoxicity. The BSG IBD guidelines14 only mention ‘regular’ monitoring of renal function without specifying a regimen and fail to highlight the fact that many 5-ASA nephrotoxicity cases occur in the first year of therapy. The MRHA guidelines are more specific.13 We therefore recommend to clinicians

That the gastroenterology team should provide clear instructions to both the patient and their GPs about the need for regular monitoring of renal function while on treatment (as discussed in the latest IBD standards guidelines),28 including those with quiescent disease discharged from secondary care. Alerting mechanisms on primary care computer systems for all patients on 5-ASAs (and indeed for any therapy known to require regular laboratory monitoring) would be a significant advantage.

Clinicians should confirm that patients attending clinic have had an up-to-date blood profile performed.

Use an IBD database to confirm that all patients on treatment undergo regular monitoring.

That the BSG guidelines14 should be more objective, for example, test renal function at least yearly for those patients taking 5-ASA treatment.

Despite the risk of 5-ASA nephrotoxicity, no studies have confirmed or refuted whether monitoring of renal function actually improves clinical outcome3. This in part is related to the infrequent occurrence of this complication. In the absence of clinical trial evidence, the above recommendations are based on expert consensus and the outcomes of case reports and not on a clinical trial that has demonstrated a reduction in harm following a standardised monitoring regimen. It is important to note that the data recommending monitoring are extensive and have been accrued over decades and from centres around the world. It is for this reason that the BSG14 and MHRA13 recommend monitoring but differ somewhat in the precise timing of renal function monitoring. This confusion may have led to differing practice among secondary and primary care clinicians and may explain some of the variations in monitoring found in our review.

Currently, an international study is being undertaken to see whether the development of interstitial nephritis can be predicted by genome-wide association studies29 based on the observation that patients developing jaundice with flucloxacillin were significantly more likely to develop it with the HLA-B*5701 genotype.23

Performing a blood test is a simple and inexpensive intervention, which in many cases may form part of testing for other conditions. It may identify renal impairment at an early and potentially reversible stage. We have found that most patients taking 5-ASAs were not undergoing testing at the recommended intervals while on treatment and that these drugs had in some been started when there was already evidence of baseline abnormalities of renal function. Clinicians need to be more aware of these potential complications.

What is already known.

5-aminosalicylates are recognised as a cause of renal impairment from interstitial nephritis.

The risk is increased in patients known to have chronic kidney disease.

Earlier diagnosis (by regular monitoring of renal function) may reduce the burden of chronic kidney disease.

What this paper adds.

Clinicians are failing to follow best practice guidelines for monitoring.

Drug therapy is started in some patients with pre existing renal impairment.

In some, the medication is continued despite a decline in renal function.

How might this impact on future clinical practice.

Clinicians must provide clear instructions on monitoring - particularly for patients discharged back to primary care.

An inflammatory bowel disease database may assist secondary care teams in their monitoring role.

No monitoring, no defence!

Footnotes

Contributors: CF and AFM conceived the idea for the paper. NS collected the information. All three authors have contributed equally to the writing of the paper.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All the information from this study is included in the paper.

References

- 1.Azad-Khan AK, Piris J, Truelove SC. An experiment to determine the active therapeutic moiety of sulphasalazine. Lancet 1977;2:892–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muller AF, Stevens PE, McIntyre AS, et al. Experience of 5-aminosalicylate nephrotoxicity in the United Kingdom. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;21:1217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gisbert JP, Gonzalez-Lama Y, Mate J. 5-Aminosalicylates and renal function in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007;13:629–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arend LJ, Springate JE. Interstitial nephritis from mesalazine: case report and literature review. Paediatric Nephrol 2004;19:550–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World MJ, Stevens PE, Ashton MA, et al. Mesalazine-associated interstitial nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1996;11:614–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Staa TP, Travis S, Leufkens HGM, et al. 5-Aminosalicylic acids and the risk of renal disease: a large British epidemiological study. Gastroenterology 2004;126:1733–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Jong DJ, Tie-in J, Habraken CM, et al. 5-Aminosalicylates and effects on renal function in patients with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2005;11:972–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel H, Barr A, Jeejeebhoy KN. Renal effects of long-term treatment with 5-aminosalicylic acid. Can J Gastroenterol 2009;23:170–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schreiber S, Hamling J, Zehnter E, et al. Renal tubular dysfunction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with aminosalicylate. Gut 1997;40:761–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Musil D, Tillich J. Early renal failure after mesalazine (case report). Acta Univ Palace Olumuc, Fac Med 2000;144:51–3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popoola J, Muller AF, Pollock L, et al. Late onset interstitial nephritis associated with mesalazine treatment. Br Med J 1998;317:795–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corrigan G, Stevens P. Review article: interstitial nephritis associated with the use of mesalazine in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000;14:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/par/documents/websiteresources/con132066.pdf 2011;12.

- 14.Mowat A, Cole A, Windsor A, et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2011;60:571–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruf-ballauf W, Hofstaedter F, Krentz K. Akute interstitielle Nephritis durch 5-Aminosalicylsaeure? Internist 1989;30: 262–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masson EA, Rhodes JM. Mesalazine associated nephrogenic diabetes insipidus presenting as weight loss. Gut 1992;33: 563–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehta RP. Acute interstitial nephritis due to 5-aminosalicylic acid. Can Med Assoc J 1990;143:1031–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Muehlendahl KE. Nephritis durch 5-Aminosalicylsaeure. Dtsche Med Wochenschr 1989;114:236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henning MV, Meinhold J, Eisenhauer T, et al. Chronische interstitielle Nephritis nach Behandlung mit 5-Aminosalicylsaeure. Dtsche Med Wochenschr 1989;114: 1090–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thuluvath PJ, Ninkovic M, Calam J, et al. Mesalazine induced interstitial nephritis. Gut 1994;35:1493–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smilde TJ, van Liebergen FJHM, Koolen MI, et al. Tubulo- interstitiele nefritis door mesalazine (S-ASA)-preparaten. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1994;138:2557–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mid-2010 Population Estimates for Primary Care Organisations in England. ONS 2011.

- 23.Daly AK, Donaldson PT, Bhatnagar P, et al. HLA-B*5701 genotype is a major determinant of drug-induced liver injury due to flucloxacillin . Nat Genet 2009;41:816–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Firwana BM, Hasan R, Chalhoub W, et al. Nephrotic syndrome after treatment of Crohn's disease with mesalamine: Case report and literature review. Avicenna J Med 2012;2:9–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novis BH, Korzets Z, Chen P, et al. Nephrotic syndrome after treatment with 5-aminosalicylic acid. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 1988;296:1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Breyer-Lewis J, et al. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:461–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zallot C, Billioud V, Frimat L, et al. 5-aminosalicylates and renal function monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease: a nationwide survey. J Crohn's Colitis 2013;7:551–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Standards for the healthcare of people who have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): IBD Standards 2013 Update (number 11). http://www.bsg.org.uk/docs/clinical/ibd_standards_13.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.So K, Bewshea C, Heap GA, et al. 5-aminosalicyate (5-ASA) Nephrotoxicity in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2013;62(Suppl 1):A22. [Google Scholar]