Abstract

Peripancreatic fluid collections are a well-known complication of pancreatitis and can vary from fluid-filled collections to entirely necrotic collections. Although most of the fluid-filled pseudocysts tend to resolve spontaneously with conservative management, intervention is necessary in symptomatic patients. Open surgery has been the traditional treatment modality of choice though endoscopic, laparoscopic and transcutaneous techniques offer alternative drainage approaches. During the last decade, improvement in endoscopic ultrasound technology has enabled real-time access and drainage of fluid collections that were previously not amenable to blind transmural drainage. This has initiated a trend towards use of this modality for treatment of pseudocysts. In this review, we have summarised the existing evidence for endoscopic drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections from published studies.

Keywords: ENDOSCOPIC ULTRASONOGRAPHY, PANCREATIC PSEUDOCYST

Introduction

Peripancreatic fluid collections (PFCs) represent a diverse group of enzyme-rich fluid collections formed as a result of pancreatic ductal disruption causing pancreatic secretions tracking into the retroperitoneum or peripancreatic tissue planes. Due to the wide discrepancy in the definition of these fluid collections, the 1992 Atlanta Classification provided a structure and uniformity of nomenclature,1 which has been revised recently to reflect the enhanced understanding of these lesions.2 Traditionally, surgical treatment was considered the standard of care, but resulted in poor outcomes along with considerable morbidity and mortality.3 Recent progress in the field of conventional endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has resulted in minimally invasive techniques with substantial improvement in clinical outcomes. Through this review, we will critically evaluate existing evidence on endoscopic management of pancreatic fluid collections along with commenting on the challenges that lie ahead in the future.

Definitions

Acute peripancreatic fluid collection

Peripancreatic fluid associated with interstitial oedematous pancreatitis within the first 4 weeks with no associated peripancreatic necrosis.

Pancreatic pseudocyst

An encapsulated collection of fluid with a well-defined inflammatory wall usually outside the pancreas with minimal or no necrosis usually occurring more than 4 weeks after the onset of interstitial oedematous pancreatitis.

Acute necrotic collection

A collection containing variable amounts of both fluid and necrosis of the pancreatic and/or peripancreatic tissues associated with necrotising pancreatitis.

Walled-off pancreatic necrosis

A mature, encapsulated collection of pancreatic and/or peripancreatic necrosis that has developed a well-defined inflammatory wall usually occurring more than 4 weeks after the onset of necrotising pancreatitis.2

Management of pseudocyst

Most pancreatic pseudocysts are asymptomatic and undergo spontaneous resolution. An early observational study had recommended that pseudocysts larger than 6 cm in size that persist for more than 6 weeks are likely to cause symptoms and should be treated.4 However, recent evidence suggests that these parameters are arbitrary and pseudocysts can remain asymptomatic regardless of size or duration.5 6 However, increasing size can result in mass effect and erosive complications that tend to be treated. Although surgical intervention has been the traditional gold standard of treatment, recent data suggest that this trend is changing. Varadarajulu et al7 reported a significant increase in the proportion of patients with pancreatic pseudocysts being treated endoscopically from 2008 to 2010 as compared with 2004 to 2007 (100% vs 84%, p=0.001). Much of this change is credited to the ability of EUS to access collections not causing luminal compression, which would have required conventional surgical intervention.

Conventional transpapillary endoscopic drainage

Peripancreatic fluid collections can be drained through conventional transmural or transpapillary endoscopy. The transpapillary approach is employed in patients with pseudocysts that directly communicate with the pancreatic duct. It is an attractive choice if the pseudocyst communicates with the pancreatic duct, if there is stricture or disruption in the pancreatic duct, if transmural drainage is not feasible due to distance (>1 cm from the enteric lumen) or is contraindicated (eg, significant coagulopathy). Pancreatic duct sphincterotomy followed by judicious dilation of downstream pancreatic duct strictures allows cannulation, and a guidewire is directed through the duct into the pseudocyst cavity, followed by placement of 5Fr or 7Fr plastic stents over the guidewire preferably into the pseudocyst cavity or across ductal disruption.8 9 Transpapillary stents are left in situ until the pseudocyst resolves or undergoes significant reduction in size as seen by CT scan, usually after a period of 6–8 weeks.

Encouraging data on transpapillary endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocyst have been reported. Catalano et al10 achieved successful transpapillary stenting in all patients (n=21) with 33 endoprosthesis for the treatment of symptomatic pseudocysts communicating directly with the main pancreatic duct. In another series, pancreatic stents were successfully placed into the cysts in 12 patients, and as close as possible to the cyst in the remaining 18 patients.11 Endoscopic transpapillary nasopancreatic drainage has also been successfully employed in patients with large and multiple pancreatic pseudocysts with a reported success rate of 91% in one study.12 However, the enthusiasm of the initial results of these small series has not been replicated in large multicentre trials. Moreover, the small calibre pancreatic duct and the stents deployed results in slow inconsistent drainage.

Conventional endoscopic transluminal drainage

The transluminal approach is the attractive alternative option in patients where pseudocysts are directly adjacent to the gastroduodenal wall and produce a visible bulge in the gastric or duodenal wall. Endoscopic needle localisation confirms the most appropriate location for cystenterostomy, which can be achieved by diathermic puncture13 or the Seldinger technique.14 Diathermic puncture involves inserting a needle knife or a Cystostome (Cook Endoscopy, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA) into the gut wall at a 90° angle at the site of maximum gastric or duodenal bulge. A needle knife is advanced through the bulge with application of cautery, a gush of cystic fluid is encountered following which contrast injection confirms position and a guidewire is inserted into the cystic cavity. The Cremer Cystostome employs a single catheter for needle knife cyst entry followed by cyst-enterostomy creation with an electrocautery ring and subsequent stent deployment.15 The Seldinger method has been shown to have comparable efficacy to the diathermic puncture technique.14 This method involves cyst puncture by an 18 G needle followed by guidewire passage into the pseudocyst, balloon tract dilation and stent placement. After cystenterostomy is achieved, one or two 10Fr transmural double pigtail stents are deployed into the pseudocyst.

The efficacy of endoscopic drainage has been confirmed on large retrospective studies. While initial technical success rates of transpapillary and transmural endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts were between 92 and 100%, final success rates have been reported to be in the range of 65–80%.9–11 16 Factors like unclear transluminal bulge, failed insertion of the drain, bleeding and gallbladder puncture have been found to be increase predisposition to treatment failure. In a retrospective study of endoscopic drainage of pseudocysts in 37 patients with chronic pancreatitis,16 while technical success was achieved in 34 patients (92%), complete resolution of pseudocyst could be achieved in only 24 patients (65%).

Hookey et al17 presented their experience in 116 patients who underwent endoscopic drainage of PFCs by transpapillary route in 15 patients, transmural in 60 and both in 41 patients. No difference in outcomes was seen between the two drainage techniques. Weckman and colleagues reported an 86% success rate in 165 patients with only a 5% recurrence rate at a mean follow-up period of 25 months.18 In another study, Cahen et al19 reported a technical success rate of 97% in 92 patients undergoing endoscopic drainage. Other authors have also reported high rates of success with transpapillary and transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts.20–22 However, an Italian study on 49 patients with pseudocysts reported a recurrence rate of 21% after initial endoscopic drainage.23 Cyst location in the head of the pancreas, multiple stent insertion and stent insertion for more than 6 weeks were found to be independent predictors of successful outcomes while presence of residual necrosis or moderate abscess debris predicted failure.19 24 25 Major complications of endoscopic pseudocyst drainage include infections (8%), bleeding (9%) and retroperitoneal perforation in 5%.26 Outcomes from studies described above and other studies27–32 are described in table 1.

Table 1.

Outcomes of transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts

| Study | Study design and year | No. of patients | Technical success | Clinical success | Recurrence | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional endoscopy | ||||||

| Binmoller et al9 | Retrospective (1995) | 53 | 50 (94%) | 47 (89%) | 11 (23%) | 6 (11%) |

| Catalano et al10 | Retrospective (1995) | 21 | 21 (100%) | 17 (81%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (6%) |

| Barthet et al11 | Retrospective (1995) | 30 | 30 (100%) | 26 (87%) | 3 (12%) | 4 (13%) |

| Bhasin et al12 | Retrospective (2006) | 11 | 10 (91%) | 7 (64%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9%) |

| Smits et al16 | Retrospective (1995) | 37 | 34 (92%) | 24 (65%) | 3 (12.5%) | 6 (16%) |

| Hookey et al17 | Retrospective (2006) | 116 | – | 108 (93%) | 19 (16%) | 13 (11%) |

| Weckman et al18 | Retrospective (2006) | 165 | – | 146 (86%) | 8 (5%) | 16 (10%) |

| Cahen et al19 | Retrospective (2005) | 97 | 89 (92%) | 79 (86%) | 4 (5%) | 31 (35%) |

| Vitale et al20 | Retrospective (1999) | 36 | 31 (86%) | 31 (86%) | 5 (14%) | 1 (3%) |

| Sharma et al21 | Retrospective (2002) | 38 | 38 (100%) | 38 (100%) | 7 (16%) | 5 (13%) |

| Libera et al22 | Retrospective (2000) | 25 | 21 (84%) | 20 (80%) | 1 (4%) | 6 (28%) |

| De Palma et al23 | Retrospective (2002) | 49 | 43 (88%) | – | 9 (21%) | 12 (25%) |

| Baron27 | Retrospective (2002) | 64 | 59 (92%) | 52 (81%) | 7 (12%) | 11 (17%) |

| Cremer28 | Retrospective (1989) | 33 | 30 (91%) | 28 (85%) | 30 (91%) | 3 (9%) |

| Sahel29 | Retrospective (1991) | 37 | 36 (97%) | 31 (86%) | 2 (5%) | 5 (14%) |

| Kozarek30 | Retrospective (1991) | 14 | – | 11 (79%) | 2 (14%) | 3 (21%) |

| Bejanin31 | Retrospective (1993) | 26 | – | 19 (73%) | 4 (15%) | 4 (15%) |

| EUS-guided endoscopic drainage | ||||||

| Antillon36 | Retrospective (2006) | 33 | 31 (94%) | 24 (82%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) |

| Lopes37 | Retrospective (2007) | 51 | 48 (94%) | 48 (94%) | 18% | 21% |

| Puri38 | Retrospective (2012) | 40 | 40 (100%) | 39 (98%) | 1 (3%) | 4 (10%) |

| Norton39 | Retrospective (2001) | 17 | 13 (77%) | 14 (82%) | 1 (7%) | 3 (18%) |

| Kruger40 | Retrospective (2006) | 35 | 30 (88%) | 33 (94%) | 4 (12%) | 0 |

| Varadarajulu et al55 | Retrospective (2011) | 95 | 89 (94%) | – | – | 5 (5%) |

EUS-guided drainage

EUS plays a central role in the evaluation and treatment of peripancreatic fluid collections. Studies have shown that EUS helps to identify alternative diagnoses due to poor sensitivity of cross-sectional imaging.33 EUS also allows real-time intervention and drainage of pancreatic fluid collections. It provides assessment of the size, location, wall thickness and contents of these lesions, especially those that do not compress the luminal wall. It also allows identification of any intervening vessels before puncture to avoid major haemorrhagic complications. Through these data, the most optimal site for pseudocyst puncture can be determined, thereby improving outcomes and reducing morbidity. Two techniques of EUS guided drainage of PFCs has been described: the EUS-endoscopy technique and the EUS single-step technique.34 The EUS-endoscopy technique employs a radial echoendoscope to evaluate and characterise the lesion including a Doppler assessment. The echo endoscope is exchanged for a duodenoscope and transmural drainage performed as described in the previous section. In the single-step technique, a linear array echoendoscope is advanced into duodenum and the best site of puncture is finalised. A 19 G needle is then introduced through the working channel of the endoscope following which the pseudocyst is punctured. A guidewire is subsequently introduced through the needle into the pseudocyst and its position is confirmed using ultrasonography and fluoroscopy. The needle is then removed and graded dilation of the tract is performed with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) cannula or needle knife cautery followed by balloon dilatation to create the fistula. Transmural stents are then placed over the guidewire as outlined previously. Figure 1 shows the steps involved in EUS-guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage.

Figure 1.

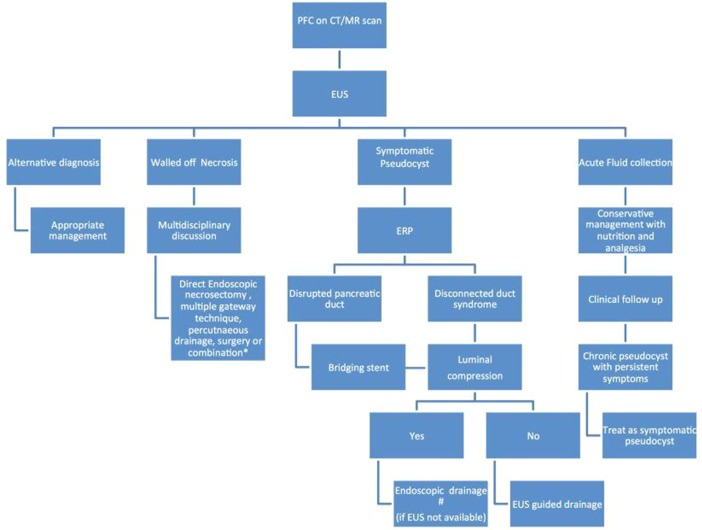

Suggested clinical algorithm for the management of peripancreatic fluid collections ERP, endoscopic retrograde pancreatography; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; PFC, peripancreatic fluid collection. *Choose the option based on availability and local expertise. #Consider referral to a tertiary centre with therapeutic EUS expertise.

First described in 1998 by Vilmann et al,35 the EUS-single step technique employs an all in one stent introduction system, thus avoiding the need for any wire exchanges. Antillon and colleagues had demonstrated encouraging results with an 82% success rate using the single-step EUS guided transmural endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts.36 A retrospective series on 51 symptomatic patients reported an initial treatment success in 48 patients (94%) though recurrence was seen in 18%.37 In a modified technique, EUS-guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage using a combination of endoprosthesis and nasocystic catheter placement, successful resolution was achieved in 39 out of 40 patients.38 Outcomes from these and other studies39 40 have been summarised in table 1.

The relative efficacy of endoscopic transmural drainage and EUS-guided drainage has been explored in prospective studies including randomised controlled trials. Table 2 summarises the findings from these studies. In one such prospective study, the two groups were similar regarding short-term (94% vs 93%) and long-term success (91% vs 84%).24 In another study, 50 patients with pseudocyst underwent either conventional endoscopic transmural/transpapillary drainage or EUS-guided transmural drainage.41 The group reported technical success in 49 of 50 patients (98%), clinical success in 90% and resolution of pseudocysts in 96% of cases without significant differences between the three groups.

Table 2.

Studies comparing conventional endoscopy with endoscopic ultrasound guided drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts

| Study design and year | No. of patients | Technical success | Clinical success | Complications | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kahaleh et al24 | TMD vs EUD (2006) | 46 vs 53 | 93% vs 94% | 84% vs 91% | 19% vs 18% | No differences |

| Barthet41 | EUD vs TMD vs TPD (2008) | 28 vs 13 vs 8 | 100% | 89% vs 925 vs 100% | 25% vs 15% vs 0% | No differences in outcomes. Overall success in 90% |

| Varadarajulu42 | EUD vs Endoscopic (2008) | 15 vs 15 | 100% vs 33%* | 100% vs 87% | 0% vs 13% | Technical success rate higher with EUD |

| Park43 | EUD vs TMD (2009) | 31 vs 29 | 94% vs 72%* | 89% vs 86% | 7% vs 10% | Technical success rate higher with EUD |

*Represents statistically significant difference.

EUD, endoscopic ultrasound guided drainage; TMD, transmural drainage; TPD, transpapillary drainage.

In a landmark prospective randomised trial, Varadarajulu et al42 compared the efficacy of EUS and conventional endoscopy for transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts at a tertiary referral centre. While technically successful drainage was achieved in all patients within the EUS cohort (100%), endoscopy was successful in only 5 of 15 (33%) of patients. Even after adjustment for luminal compression and gender, technical success was found to be better for EUS than endoscopy. On further analyses, there was no difference in the rates of treatment success in the two groups, either on intention-to-treat analysis (100% vs 84%, p=0.48) or as-treated analysis (95.8% vs 80%, p=0.32). Another randomised prospective trial compared the technical success and clinical outcomes of EUS-guided drainage and conventional endoscopic transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts.43 On analysis, it was found that the rate of technical success was higher in the EUS group (94% vs 72%, p=0.039). Comparing pseudocyst resolution rates between EUS and conventional endoscopy, both short-term (97% vs 91%, p=0.565) and long-term (89% vs 86%, p=0.696) analyses did not reveal statistically significant differences in the clinical outcomes.

In a recent publication, the authors compared endoscopic and surgical cystogastrostomy for pseudocysts on an open-label, single-centre randomised controlled trial.44 The authors reported no differences between the two groups in terms of treatment successes, complications or reinterventions. The length of hospital stay was shorter in the endoscopy group (2 days vs 6 days, p<0.001). Complications during endoscopic drainage can occur either directly related to the procedure or as an indirect consequence of placement of stents and drains.9 16 In a study of 148 patients, the authors reported that complications were rare with EUS-guided drainage of PFCs.45

Management of walled-off pancreatic necrosis

Walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WON) are heterogeneous collections of pancreatic fluid with necrotic debris surrounded by an encapsulating wall that comprise less than 5% of peripancreatic fluid collections.46 It is generally recommended to defer treatment until these lesions have an encapsulated wall around them as premature intervention can be associated with poor outcomes.47 Ever since the first report of a direct transgastric endoscopic debridement of WON by Seifert et al,48 minimally invasive endoscopic techniques have continued to evolve. Table 3 outlines the outcomes from studies on endoscopic management of WON. Direct endoscopic necrosectomy involves passage of an endoscope into the necrotic cavity and removal of necrotic debris with baskets, prongs or other mechanical aids with the aim to remove necrotic debris, facilitate drainage and healing. Other technique that has been described is the multiple transluminal gateway technique (MTGT) for drainage of necrosis that involves creating multiple transluminal fistulae with stent placement.49

Table 3.

Outcomes of endoscopic drainage of walled-off pancreatic necrosis

| Study | Study design and year | No. of patients | Clinical success | Complications | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papachristou et al50 | Retrospective (2007) | 53 | 43 (81%) | 12 (23%) | Diabetes, size of WON and extension into paracolic gutter predict operative therapy |

| Gardner et al51 | Retrospective (2011) | 104 | 95 (91%) | 15 (14%) | – |

| Seifert et al52 | Retrospective (2009) | 93 | 74 (80%) | 24 (26%) | Mortality rate of 7.5% at 30 days |

| Bakker et al53 | Endoscopic vs surgical necrosectomy (2012) | 10 vs 12 | – | 20% vs 80%* | Endoscopy drainage associated with reduced IL-6 levels post-procedure, reduced incidence of multiple-organ failure and pancreatic fistula |

*Represents statistically significant difference.

IL, interleukin; WON, walled-off pancreatic necrosis.

Outcomes with minimally invasive procedures

In a retrospective review of 53 patients who underwent endoscopic transmural drainage/debridement of WON, the authors reported a final success rate of 81% (43 of 53 patients) while 10 patients (19%) had persistence of WON at a median follow-up of 6 months.50 On further analysis, preexisting diabetes mellitus, size of WON and extension of WON into the paracolic gutter were found to be predictors for need for subsequent open operative treatment. In one of the largest multicentre studies on the role of direct endoscopic necrosectomy in patients with WON, successful resolution was achieved in 95 patients (91%) with a mean time to resolution of 4.1 months from the initial procedure. On univariate analysis, a body mass index >32 was found to be associated with a failed endoscopic procedure.51

Investigators of the GEPARD study reported a similar success rate of 80% in 93 patients undergoing a mean of six interventions for WON after an attack of severe acute pancreatitis.52 Long-term follow-up revealed sustained clinical improvement in 84% of patients. The Dutch Acute Pancreatitis Study group recently published their findings from the PENGUIN trial that randomised 22 patients with necrotising pancreatitis to undergo either open surgical necrosectomy or transgastric endoscopic necrosectomy.53 The investigators found that endoscopic necrosectomy reduced pro-inflammatory response, composite clinical end points and the number of pancreatic fistulas compared with surgical necrosectomy. The PANTER trial compared a step-up approach with open surgical necrosectomy.54 The step-up arm involved percutaneous drainage followed, if necessary, by minimally invasive retroperitoneal necrosectomy. This study found that patients in the step-up arm had fewer immediate and late complications, although the mortality was not different. Significantly, 35% of the patients received percutaneous drainage alone. Although this trial did not involve endoscopic necrosectomy, it highlights the other treatment options that are presently available for the patient.

Experience from comparative studies

Evidence from comparative studies suggests that endoscopic drainage outcomes vary based on the type of pancreatic fluid collection with worse outcomes in patients with necrosis. In one such study, the comparative outcomes of pseudocysts (acute and chronic) and pancreatic necrosis after transmural and/or transpapillary endoscopic drainage in 138 patients were discussed.27 Patients with chronic pseudocysts were more likely to achieve complete resolution (59/64, 92%) than acute pseudocysts (23/31, 74%, p=0.02) or necrosis (31/43, 72%, p=0.006). Varadarajulu et al55 published their collective experience with endoscopic transmural drainage (conventional and ultrasound guided) in 211 patients over a 7-year period. In patients with pancreatic duct leakage, an ERCP stent was placed prior to endoscopic drainage. The overall treatment success was 85.3% though when analysed separately it was found to be much higher for pseudocyst and abscess as compared with necrosis (93.5% vs 63.2%, p<0.0001). The group found that successful treatment was more likely for patients with pseudocyst or abscess than necrosis (adjusted OR=7.6, 95% CI 2.9 to 20.1, p<0.0001). Furthermore, patients with peripancreatic fluid collections who underwent pancreatic duct stenting did considerably better than those who did not (97.5% vs 80%, p=0.01).56

Role of ERCP

Acute necrotising pancreatitis can often result in pancreatic ductal disruption.57 In such patients with partial pancreatic ductal injury or disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome, there is a high rate of recurrence of PFCs on follow-up. Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERCP) can evaluate for pancreatic ductal injury/leak. In patients with a disrupted pancreatic duct, placement of a bridging stent improves outcomes while in patients with disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome the transmural stents are left in situ indefinitely. This facilitates drainage of the proximal portion of viable pancreatic tissue and reduces the risk of recurrence. Table 4 outlines the outcomes from studies on ERCP and stent placement in patients with pancreatic duct injury.30 58–61 In one study, the authors routinely performed ERCP in all patients after endoscopic cystogastrostomy for pancreatic pseudocysts to assess and treat pancreatic ductal leak.44

Table 4.

Outcomes of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and stent placement in patients with pancreatic duct injury

| Study | Study design and year | No. of patients | Clinical success | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kozarek30 | Retrospective (1991) | 18 | 16 (89%) | 4 (22%) |

| Kim et al58 | Retrospective (2001) | 3 | 3 (100%) | 2 (66%) |

| Telford et al59 | Retrospective (2002) | 43 | 25 (58%) | 4 (9%) |

| Varadarajulu et al60 | Retrospective (2005) | 97 | 52 (55%) | 6 (6%) |

| Bhasin et al61 | Retrospective (2012) | 6 | 6 (100%) |

Challenges

Notwithstanding the vast array of technical and clinical advancements in this field, certain questions still remain unanswered. Although for pure pseudocysts transmural drainage appears to provide excellent outcomes, well-designed large multicentre trials are required to define the optimal management of WON. The role of transmural metal stent placement needs robust study with clearly defined endpoints and cost-effectiveness for the management of WON. Furthermore, the role of direct endoscopic necrosectomy, video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement, minimal access laparoscopic necrosectomy or a combination of these techniques need to be evaluated further. It is still unclear when endoscopic procedures suffice and when a surgical intervention is required. However, surgical or percutaneous techniques are recommended when the pseudocyst wall is 1.5–2 cm away from the gastrointestinal lumen.

Summary

Peripancreatic fluid collections are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. EUS plays a central role in the evaluation and drainage of pseudocysts, while conventional endoscopy maybe appropriate for patients with PFCs within easy endoscopic reach and when EUS is not available. Although EUS appears to play a central role (figure 2) in the diagnosis and treatment of simple pseudocysts, its role in the management of WON is evolving. Not only does EUS reduce complication rate by localising the safest site for puncture and drainage, it also maximises the number of patients amenable to endoscopic drainage by treating collections that would have been hard to treat by the blind approach. Effective use of endoscopic techniques to manage peripancreatic fluid collections will eventually depend on optimising timing and localisation of transmural access, duration of stent placement along with perfecting the tools to assist in safe drainage/debridement of these collections.

Figure 2.

Approach to endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided pseudocyst drainage. (A) Fluoroscopy image of guidewire coiled in the pseudocyst cavity; (B) fluoroscopy image of balloon dilation of cyst gastrostomy tract demonstrating the waist; (C) fluoroscopy image showing obliteration of balloon waist representing fistula creation; (D) fluoroscopy image of transmural stents being deployed over the guidewire.

Footnotes

Contributors: JG: literature search, manuscript preparation. JR: concept, manuscript preparation and review.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bradley EL., III A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, Ga, September 11 through 13, 1992. Arch Surg 1993;128:586–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis–2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut 2013;62:102–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin RF, Hein AR. Operative management of acute pancreatitis. Surg Clin North Am 2013;93:595–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley EL, Clements JL, Jr., Gonzalez AC. The natural history of pancreatic pseudocysts: a unified concept of management. Am J Surg 1979;137:135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maringhini A, Uomo G, Patti R, et al. Pseudocysts in acute nonalcoholic pancreatitis: incidence and natural history. Dig Dis Sci 1999;44:1669–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vitas GJ, Sarr MG. Selected management of pancreatic pseudocysts: operative versus expectant management. Surgery 1992;111:123–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM, Latif S, et al. Management of pancreatic fluid collections: a changing of the guard from surgery to endoscopy. Am Surg 2011;77:1650–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monkemuller KE, Kahl S, Malfertheiner P. Endoscopic therapy of chronic pancreatitis. Dig Dis 2004;22:280–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Binmoeller KF, Seifert H, Walter A, et al. Transpapillary and transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc 1995;42:219–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catalano MF, Geenen JE, Schmalz MJ, et al. Treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts with ductal communication by transpapillary pancreatic duct endoprosthesis. Gastrointest Endosc 1995;42:214–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barthet M, Sahel J, Bodiou-Bertei C, et al. Endoscopic transpapillary drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc 1995;42:208–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhasin DK, Rana SS, Udawat HP, et al. Management of multiple and large pancreatic pseudocysts by endoscopic transpapillary nasopancreatic drainage alone. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:1780–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howell DA, Holbrook RF, Bosco JJ, et al. Endoscopic needle localization of pancreatic pseudocysts before transmural drainage. Gastrointest Endosc 1993;39:693–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monkemuller KE, Baron TH, Morgan DE. Transmural drainage of pancreatic fluid collections without electrocautery using the Seldinger technique. Gastrointest Endosc 1998;48:195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seewald S, Ang TL, Soehendra N. Advanced techniques for drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;69:S182–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smits ME, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN, et al. The efficacy of endoscopic treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc 1995;42:202–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hookey LC, Debroux S, Delhaye M, et al. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic-fluid collections in 116 patients: a comparison of etiologies, drainage techniques, and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;63:635–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weckman L, Kylanpaa ML, Puolakkainen P, et al. Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts. Surg Endosc 2006;20:603–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cahen D, Rauws E, Fockens P, et al. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts: long-term outcome and procedural factors associated with safe and successful treatment. Endoscopy 2005;37:977–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vitale GC, Lawhon JC, Larson GM, et al. Endoscopic drainage of the pancreatic pseudocyst. Surgery 1999;126:616–21; discussion 621–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma SS, Bhargawa N, Govil A. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocyst: a long-term follow-up. Endoscopy 2002;34:203–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Libera ED, Siqueira ES, Morais M, et al. Pancreatic pseudocysts transpapillary and transmural drainage. HPB Surg 2000;11:333–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Palma GD, Galloro G, Puzziello A, et al. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts: a long-term follow-up study of 49 patients. Hepatogastroenterology 2002;49:1113–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kahaleh M, Shami VM, Conaway MR, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound drainage of pancreatic pseudocyst: a prospective comparison with conventional endoscopic drainage. Endoscopy 2006;38:355–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soliani P, Franzini C, Ziegler S, et al. Pancreatic pseudocysts following acute pancreatitis: risk factors influencing therapeutic outcomes. JOP 2004;5:338–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samuelson AL, Shah RJ. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2012;41:47–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baron TH, Harewood GC, Morgan DE, et al. Outcome differences after endoscopic drainage of pancreatic necrosis, acute pancreatic pseudocysts, and chronic pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;56:7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cremer M, Deviere J, Engelholm L. Endoscopic management of cysts and pseudocysts in chronic pancreatitis: long-term follow-up after 7 years of experience. Gastrointest Endosc 1989;35:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sahel J. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic cysts. Endoscopy 1991;23:181–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kozarek RA, Ball TJ, Patterson DJ, et al. Endoscopic transpapillary therapy for disrupted pancreatic duct and peripancreatic fluid collections. Gastroenterology 1991;100:1362–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bejanin H, Liguory C, Ink O, et al. Endoscopic drainage of pseudocysts of the pancreas. Study of 26 cases. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 1993;17:804–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Funnell IC, Bornman PC, Krige JE, et al. Endoscopic drainage of traumatic pancreatic pseudocyst. Br J Surg 1994;81:879–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polakow J, Ladny JR, Serwatka W, et al. Percutaneous fine-needle pancreatic pseudocyst puncture guided by three-dimensional sonography. Hepatogastroenterology 2001;48:1308–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vila JJ, Carral D, Fernandez-Urien I. Pancreatic pseudocyst drainage guided by endoscopic ultrasound. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2010;2:193–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vilmann P, Hancke S, Pless T, et al. One-step endosonography-guided drainage of a pancreatic pseudocyst: a new technique of stent delivery through the echo endoscope. Endoscopy 1998;30:730–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antillon MR, Shah RJ, Stiegmann G, et al. Single-step EUS-guided transmural drainage of simple and complicated pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;63:797–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopes CV, Pesenti C, Bories E, et al. Endoscopic-ultrasound-guided endoscopic transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts and abscesses. Scand J Gastroenterol 2007;42:524–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Puri R, Mishra SR, Thandassery RB, et al. Outcome and complications of endoscopic ultrasound guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage using combined endoprosthesis and naso-cystic drain. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;27:722–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Norton ID, Clain JE, Wiersema MJ, et al. Utility of endoscopic ultrasonography in endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts in selected patients. Mayo Clin Proc 2001;76:794–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kruger M, Schneider AS, Manns MP, et al. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts or abscesses after an EUS-guided 1-step procedure for initial access. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;63:409–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barthet M, Lamblin G, Gasmi M, et al. Clinical usefulness of a treatment algorithm for pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc 2008;67:245–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Varadarajulu S, Christein JD, Tamhane A, et al. Prospective randomized trial comparing EUS and EGD for transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2008;68:1102–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park DH, Lee SS, Moon SH, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided versus conventional transmural drainage for pancreatic pseudocysts: a prospective randomized trial. Endoscopy 2009;41:842–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Varadarajulu S, Bang JY, Sutton BS, et al. Equal Efficacy of Endoscopic and Surgical Cystogastrostomy for Pancreatic Pseudocyst Drainage in a Randomized Trial. Gastroenterology 2013;145:583–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Varadarajulu S, Christein JD, Wilcox CM. Frequency of complications during EUS-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections in 148 consecutive patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;26:1504–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brun A, Agarwal N, Pitchumoni CS. Fluid collections in and around the pancreas in acute pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011;45:614–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takahashi N, Papachristou GI, Schmit GD, et al. CT findings of walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN): differentiation from pseudocyst and prediction of outcome after endoscopic therapy. Eur Radiol 2008;18:2522–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seifert H, Wehrmann T, Schmitt T, et al. Retroperitoneal endoscopic debridement for infected peripancreatic necrosis. Lancet 2000;356:653–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Varadarajulu S, Phadnis MA, Christein JD, et al. Multiple transluminal gateway technique for EUS-guided drainage of symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;74:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Papachristou GI, Takahashi N, Chahal P, et al. Peroral endoscopic drainage/debridement of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Ann Surg 2007;245:943–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gardner TB, Coelho-Prabhu N, Gordon SR, et al. Direct endoscopic necrosectomy for the treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis: results from a multicenter US series. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;73:718–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seifert H, Biermer M, Schmitt W, et al. Transluminal endoscopic necrosectomy after acute pancreatitis: a multicentre study with long-term follow-up (the GEPARD Study). Gut 2009;58:1260–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bakker OJ, van Santvoort HC, van Brunschot S, et al. Endoscopic transgastric vs surgical necrosectomy for infected necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized trial. JAMA 2012;307:1053–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC, Nieuwenhuijs VB, et al. Minimally invasive ‘step-up approach’ versus maximal necrosectomy in patients with acute necrotising pancreatitis (PANTER trial): design and rationale of a randomised controlled multicenter trial [ISRCTN13975868]. BMC Surg 2006;6:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Varadarajulu S, Bang JY, Phadnis MA, et al. Endoscopic transmural drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections: outcomes and predictors of treatment success in 211 consecutive patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2011;15:2080–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trevino JM, Tamhane A, Varadarajulu S. Successful stenting in ductal disruption favorably impacts treatment outcomes in patients undergoing transmural drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;25:526–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neoptolemos JP, London NJ, Carr-Locke DL. Assessment of main pancreatic duct integrity by endoscopic retrograde pancreatography in patients with acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg 1993;80:94–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim HS, Lee DK, Kim IW, et al. The role of endoscopic retrograde pancreatography in the treatment of traumatic pancreatic duct injury. Gastrointest Endosc 2001;54:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Telford JJ, Farrell JJ, Saltzman JR, et al. Pancreatic stent placement for duct disruption. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;56:18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Varadarajulu S, Noone TC, Tutuian R, et al. Predictors of outcome in pancreatic duct disruption managed by endoscopic transpapillary stent placement. Gastrointest Endosc 2005;61:568–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bhasin DK, Rana SS, Rao C, et al. Endoscopic management of pancreatic injury due to abdominal trauma. JOP 2012;13: 187–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]